Abstract

Background

Fosmanogepix is a first-in-class antifungal targeting the fungal enzyme Gwt1, with broad-spectrum activity against yeasts and moulds, including multidrug-resistant fungi, formulated for intravenous (IV) and oral administration.

Methods

This global, multicenter, non-comparative study evaluated the safety and efficacy of fosmanogepix for first-line treatment of candidaemia in non-neutropenic adults. Participants with candidaemia, defined as a positive blood culture for Candida spp. within 96 h prior to study entry, with ≤2 days of prior systemic antifungals, were eligible. Participants received fosmanogepix for 14 days: 1000 mg IV twice daily on Day 1, followed by maintenance 600 mg IV once daily, and optional switch to 700 mg orally once daily from Day 4. Eligible participants who received at least one dose of fosmanogepix and had confirmed diagnosis of candidaemia (<96 h of treatment start) composed the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population. Primary efficacy endpoint was treatment success at the end of study treatment (EOST) as determined by the Data Review Committee. Success was defined as clearance of Candida from blood cultures with no additional antifungal treatment and survival at the EOST.

Results

Treatment success was 80% (16/20, mITT; EOST) and Day 30 survival was 85% (17/20; 3 deaths unrelated to fosmanogepix). Ten of 21 (48%) were switched to oral fosmanogepix. Fosmanogepix was well tolerated with no treatment-related serious adverse events/discontinuations. Fosmanogepix had potent in vitro activity against baseline isolates of Candida spp. (MICrange: CLSI, 0.002–0.03 mg/L).

Conclusions

Results from this single-arm Phase 2 trial suggest that fosmanogepix may be a safe, well-tolerated, and efficacious treatment for non-neutropenic patients with candidaemia, including those with renal impairment.

Introduction

Disseminated infections associated with Candida species (spp.) are common healthcare associated infections which remain a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. In the USA, there were an estimated 23 000 cases of candidaemia and 3400 deaths in 2017, with an incidence of 7 cases per 100 000 people.1 Despite standard of care (SOC) antifungal therapy, mortality rates remain high. Recent estimates of all-cause in-hospital mortality are approximately 25% overall, and 31% for patients aged ≥65 years.1 Approximately 50% of Candida isolates identified in healthcare-associated bloodstream infections are currently due to non-Candida albicans, including multidrug-resistant C. auris,2C. parapsilosis and C. glabrata (new nomenclature: Nakaseomyces glabrata).3,4 Treatment failure in patients with candidaemia is approximately 35%5 and existing antifungals can be problematic due to the route of delivery, significant drug–drug interactions, and/or lack of efficacy due to drug resistance.6 This unmet medical need also remains significant among high-risk patients, such as immunocompromised patients, transplant recipients, and ICU patients.6–8

Fosmanogepix (formerly PF-07842805; APX001; E1211) is the first member in the ‘gepix’ class of antifungals with a unique mechanism of action (MOA). The prodrug, fosmanogepix, is rapidly converted in vivo by systemic phosphatases to the microbiologically active moiety, manogepix. Manogepix inhibits the conserved fungal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored cell wall transfer protein 1 (Gwt1), which catalyzes inositol acylation of GPI.9,10 In yeasts, GPI mediates cross-linking of cell wall mannoproteins to β-1,6-glucan. Inhibition of Gwt1 results in pleiotropic effects on fungal cells (inhibition of fungal adherence to surfaces, biofilm formation, and germ tube formation), severe growth defects and death.10,11 Manogepix does not inhibit PIG-W (a mammalian ortholog but with low homology to Gwt1) which also catalyzes the inositol acylation of GPI.10–12 Pleiotropic MOA of manogepix results in broad spectrum activity against clinically significant yeasts and moulds, including resistant strains.6 However, manogepix has poor in vitro activity against Candida krusei (MIC range: 2 to >32 mg/L), which is most likely due to non-target-based resistance mechanisms such as differences in C. krusei cell permeability and efflux, rather than Gwt1 target protein-based expression.9,13

Fosmanogepix is broadly distributed in tissues with a half-life of ∼2.5 days.14,15 Two drug–drug interaction studies (NCT02957929; NCT04166669) for fosmanogepix have been completed (results not yet published). Animal model studies have shown that fosmanogepix is rapidly absorbed and extensively distributed to most parts of the body such as liver, lung, brain, eye, urine, abdominal fat, and kidney cortex.14 It is available in intravenous (IV) and oral formulations, and has high oral bioavailability, enabling oral ‘step-down’ treatment during transition of care.15,16 Data from animal models also indicated that fosmanogepix was primarily eliminated through faeces or biliary excretion.14 A Phase 1 fosmanogepix study (data not published; NCT04804059) conducted to provide human metabolite profiling after single oral or IV dose of fosmanogepix in healthy male participants showed extensive distribution and similar excretion between urinary and faecal pathways after both oral and IV infusion.

In this open-label Phase 2 study, we enrolled participants who had documented candidaemia, including those with possible or probable drug-resistant organisms, such as C. glabrata. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of fosmanogepix for the treatment of adult non-neutropenic patients with candidaemia.

Methods

Ethics

This study was conducted at nine sites in the USA, Israel, Spain, and Belgium in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonization guidelines on Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). Independent ethics committees at each site approved the study protocol (USA: UC Davis Clinical Committee Approval#1084643-2, Washington University School of Medicine Approval#20172684; Spain: Ethics committee of Hospital Universitario Mútua de Terrasa, Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, and Hospital General Universitario de Alicante Approval#182/18; Belgium: Cliniques universitaires de Bruxelles Approval#SRB_201807_156; Israel: Sheba Medical Center Approval#4695-17-SMC, Rambam Medical Center Approval#0584-17-RMB, and Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center Approval#0710-17-TLV).

Participants and study design

This multicenter, open-label, non-comparative, single-arm global study conducted between October 2018 and March 2020 evaluated the efficacy and safety of fosmanogepix as first-line treatment for candidaemia, in non-neutropenic adult participants (ClinicalTrials.gov:NCT03604705; EudraCT number:2017-003571-56). This study was conducted in accordance with ICH-GCP Directive 2001/20/EC, applicable regulatory requirements, and the Declaration of Helsinki.17

Eligible participants had a new diagnosis of candidaemia based on a blood sample drawn within 96 h of fosmanogepix treatment, which could include Candida spp. with suspected or documented resistance to at least one SOC systemic antifungal. If eligible participants had pre-existing intravascular catheters, they were removed and replaced as necessary. All participants or their legally authorized representatives provided written informed consent.

Key exclusion criteria included neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <500 cells/µL), diagnosis of deep-seated Candida infections, C. krusei infection, hepatosplenic candidiasis, and pregnancy or lactation. Participants were excluded if they received >48 h equivalent of prior systemic antifungal treatment for the current episode of candidaemia. All inclusion and exclusion criteria, including criteria (and dosing) for patients with renal impairment, are provided in Material S1(a and b), available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

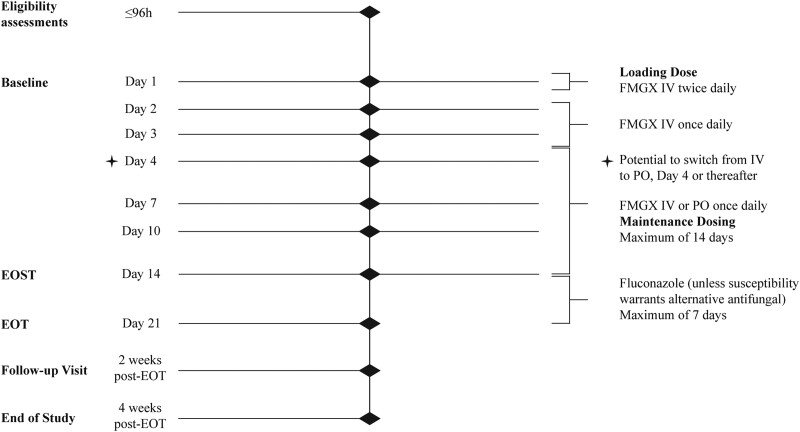

Participants were given fosmanogepix 1000 mg IV twice daily loading dose within the first 24 h, followed by a maintenance dose of 600 mg IV once daily. IV infusions were 3 h in duration. A switch to oral fosmanogepix 700 mg daily could be initiated from Day (D) 4 onwards, if blood cultures showed no further growth and participants were able to tolerate oral medications. Maximum duration of fosmanogepix treatment was 14 days. The end of study treatment (EOST) visit was conducted at fosmanogepix treatment completion (Figure 1). Participants requiring >14 days of antifungal therapy to adhere to Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)-recommended treatment of candidaemia guidelines18 were allowed to receive step-down therapy with fluconazole or an alternative species-appropriate antifungal. The end of treatment (EOT) visit was conducted upon completion of all antifungal treatments. Participants were followed for 4 weeks after the EOT/EOST. Blood cultures were performed daily during the treatment period until two consecutive cultures were negative, and subsequently at all following study visits (Figure 1). Adverse events (AEs) were captured from the date of informed consent through study completion and coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities V20.1. Microbiological susceptibility testing was performed according to CLSI M27A419 and EUCAST E.DEF 7.3.220 methods at NTS Ventures. Results are presented based on CLSI methodology.21

Figure 1.

Study schematic. Time period (<96 h) to complete eligibility assessments started at the time that the sample for the blood culture positive for Candida was collected. EOST may be the same as EOT for those participants who do not step-down to fluconazole or alternative antifungal therapy. EOST, end of study treatment; EOT, end of treatment; FMGX, fosmanogepix; IV, intravenous; PO, oral.

Outcomes assessed

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population/safety population included all participants who received at least one dose of fosmanogepix. The modified ITT (mITT) population included all participants who received at least one dose of fosmanogepix and had a confirmed diagnosis of candidaemia within 96 h of treatment start.

A Data Review Committee (DRC) of recognized fungal infectious disease experts provided independent oversight and standardized interpretation. The DRC confirmed eligibility for efficacy analysis, confirmed candidaemia diagnosis, and adjudicated the response to treatment. A Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) periodically reviewed safety data.

Treatment success at the EOST/EOT was defined as clearance of Candida from blood cultures with no additional use of systemic antifungal treatment and survival at the EOST/EOT. Any case that did not meet the above criteria was classified as a treatment failure. The primary efficacy endpoint was treatment success at the EOST in the mITT population as determined by the DRC. Treatment success at the EOT, and 2 and 4 weeks after the EOT as determined by the DRC, overall survival at study D30, the time to first negative blood culture, mycological outcomes, and treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were also evaluated. Any temporal association with study drug administration was assessed based on sequence and timing of occurrence. MICs for collected samples were assessed and additional analysis for susceptibility and resistance were evaluated.

Statistical considerations and methods of data analysis

For the primary endpoint, the number and percentage of participants with treatment success or failure at the EOST determined by the DRC was described for the mITT population, with 95% two-sided exact binomial confidence intervals (CIs). Secondary endpoints were summarized descriptively for the mITT population with 95% two-sided exact binomial CIs. Kaplan–Meier analysis for median time to first negative blood culture and median time to death was conducted.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 or higher.22

Results

Disposition, demographics and baseline characteristics

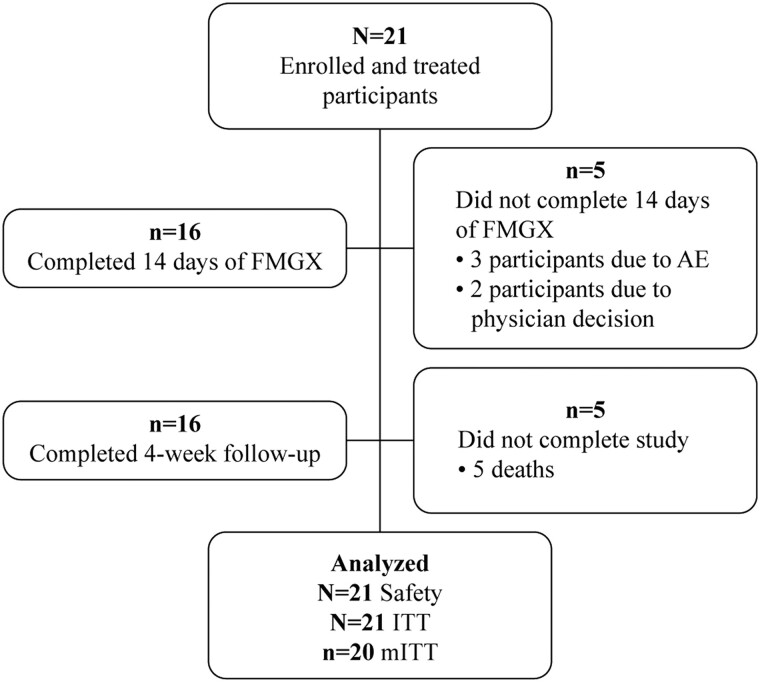

Twenty-one participants received fosmanogepix; one participant did not have a confirmed diagnosis of candidaemia within 96 h of the start of treatment and was excluded from the mITT population. The majority (16/21; 76.2%) of participants in the ITT population completed 14 days of fosmanogepix. Five participants did not receive 14 days of treatment with fosmanogepix: three cases discontinued were due to a non-drug related AE (two of whom received 13 days of treatment) (Figure 2) and two discontinued due to investigator/physician decision. Five (23.8%) participants died during the study: three participants died on or before D30 and two participants died after D30. All five deaths were deemed unrelated to the study treatment by the investigator.

Figure 2.

Participant disposition. AE, adverse event; FMGX, fosmanogepix; ITT, intent-to-treat; mITT, modified intent-to-treat.

The demographics and baseline characteristics for study participants in the ITT and mITT populations had no notable differences (Table 1). Two participants had infections with two species of Candida. Underlying disease leading to candidaemia included malignancies, surgeries/procedures including central venous catheter line placement, infections (including device-related infection, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, and sepsis), gastrointestinal disorders, burns and wounds, diabetes, and acute kidney injury. Ten participants (48%) transitioned from IV fosmanogepix to the oral formulation from D4 onwards.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Parameter | mITT N = 20 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) (range) | 62.9 (10.86) (43–78) |

| Median | 64.5 |

| Age category (years), n (%) | |

| <65 | 10 (50.0) |

| ≥65 | 10 (50.0) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 13 (65.0) |

| Female | 7 (35.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black or African American | 1 (5.0) |

| White | 19 (95.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| Mean (SD) | 25.29 (7.65) |

| Median | 23.49 |

| APACHE II score | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.1 (7.1) |

| Median | 12.5 |

| APACHE II score category, n (%) | |

| <10 | 7 (35.0) |

| 10–19 | 7 (35.0) |

| 20–30 | 6 (30.0) |

| ICU, n (%) | 9 (45.0) |

| Baseline pathogena | |

| C. glabrata | 10 (50.0) |

| C. albicans | 8 (40.0) |

| C. parapsilosis | 3 (15.0) |

| C. dubliniensis | 1 (5.0) |

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; SD, standard deviation; spp, species; yrs, years.

Percentages were calculated using the number of participants in the column heading as the denominator. Two participants had two baseline Candida spp.

Efficacy

Primary endpoint: treatment success at the EOST

Treatment success at the EOST, as assessed by the DRC, was 80% (16/20) in the mITT population Table 2. The four (20.0%) participants who were treatment failures at the EOST are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Efficacy endpoints: treatment success and survival

| mITT n/N (%) (95%CI) |

|

|---|---|

| Response at EOST | |

| Successa | 16/20 (80) (56.3–94.3) |

| Failure | 4/20 (20) (5.7–43.7) |

| Reasons for failure at EOST | |

| Persistent Candida spp. in blood culturesb | 3/20 |

| Deathc | 1/20 |

| Response at EOT | |

| Success | 15 (75.0) (50.9–91.3) |

| Failured | 5 (25.0) (8.7–49.1) |

| Response at 2 weeks after EOT | |

| Treatment success sustained | 12 (60.0) (36.1–80.9) |

| Clinical relapse | 2 (10.0) (1.2–31.7) |

| Death | 1 |

| Response at 4 weeks after EOT | |

| Treatment success sustained | 11 (55.0) (31.5–76.9) |

| Death | 1 |

| Survival at D30 | |

| Participant survival at D30 | 17/20 (85) |

| Median time to death (days) | 15 |

| Reasons for mortality through D30: | |

| Gram-negative (Acinetobacter) sepsis (D12) | 1/20 |

| Progression of underlying cancers (D15) | 1/20 |

| Worsening of interstitial pneumonia (D30) | 1/20 |

If there was no step-down anti-fungal treatment, EOT = EOST. Efficacy outcomes are up to the timepoint of failure. Percentages were calculated using the number of participants in the column heading as the denominator. 95% CIs were two-sided exact binomial CIs. CI, confidence interval; DRC, data review committee; EOST, end of study drug treatment; EOT, end of antifungal treatment; mITT, modified intent-to-treat; spp., species.

Success at EOST definition (composite): (i) eradication of Candida spp. from blood; and (ii) no use of other systemic antifungal through to EOST; and (iii) alive at EOST. Failure: any case not meeting definition of success.

C. glabrata (n = 1), C. albicans (n = 1), C. parapsilosis (n = 1).

Death on D12—investigator assessed cause as Gram-negative (Acinetobacter) bacteraemia/sepsis.

EOST + EOT; one additional failure from EOST.

Table 3.

Summary of participants who were treatment failures at EOST

| Age (years)/sex/APACHE score | Main underlying condition(s) | Infecting Candida spp. |

MGX MICa (mg/L) |

FMGX duration IV/oral |

Candidemia status at EOST | D30 survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43/male/2 | Sternal wound dehiscence with staphylococcal osteomyelitis, PVD | C. parapsilosis | 0.008 | 5 days IV only | Persistent C. parapsilosis in blood culture | Alive D30 |

| 53/male/6 | Community-acquired pneumonia | C. albicans | 0.004 | 7 days IV only | Persistent C. albicans in blood culture; probable infected thrombus | Alive D30 |

| 70/female/12 | Urothelial adenocarcinoma; multiple comorbidities, pneumonia | C. glabrata (and C. albicans only at baseline) | 0.016 | 14 days IV only | Persistent C. glabrata in blood culture | Alive D30, died D42 |

| 54/male/27 | GI tract cancer with retroperitoneal and lung metastases, pneumonia, ARF | C. glabrata | 0.016 | 11 days IV only | Blood cultures negative for C. glabrata; positive for A. baumannii | Died D12 |

ARF, acute renal failure; CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; CVC, central venous catheter; FMGX, fosmanogepix; GI, gastrointestinal; MGX, manogepix; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; spp., species; yrs, years.

MIC values are representative of baseline isolates.

Blood cultures remained persistently positive for the baseline Candida spp. in three of four participants who were treatment failures at the EOST, despite appropriate intravascular line management. Three participants received alternative antifungal therapy after stopping fosmanogepix (per investigator and outside of the scope of the protocol) and were alive at D30.

The fourth participant was a 54-year-old male with metastatic digestive tract cancer, a history of multiple abdominal surgical procedures, recent sepsis, ongoing mechanical ventilation and pneumonia, and an APACHE score of 27, with positive C. glabrata cultures until D3 and negative thereafter; fosmanogepix treatment was stopped on D11 due to leucopenia, not related to fosmanogepix, and anidulafungin was initiated. C. glabrata was cultured from the nephrostomy tube on D11. On Day 12, Acinetobacter baumannii was cultured from blood. The participant died on D12, with the cause of death ascribed to Acinetobacter sepsis, as per the investigator. The DRC assessed that candidaemia may have contributed to death.

In all four participants who experienced treatment failure at the EOST, the baseline Candida isolate manogepix MIC values were low, and remained low, indicating that treatment failure was unrelated to changes in manogepix MIC values.

Outcomes at the EOT and follow-up

Treatment success at the EOT in the mITT population was 75% (15/20). Three participants (15%) received protocol-allowed step-down antifungals with fluconazole or an alternative species-appropriate antifungal after 14 days of fosmanogepix treatment. All three had prior clearance of Candida spp. from blood and experienced treatment successes at the EOST. However, one participant developed a mixed C. albicans and C. glabrata pleuropulmonary empyema that required additional prolonged antifungal treatment, resulting in treatment failure at the EOT.

Of the 15 participants assessed as treatment successes at the EOT, 4 did not sustain this outcome through the 4 week follow-up period (Table 2).

One participant, with ascending cholangitis secondary to common bile duct obstruction attributed to underlying pancreatic cancer, experienced treatment success at the EOST but had recurrent candidaemia at 2 week follow-up after the EOT. The MIC of manogepix in the recurrent C. glabrata isolate increased by 5–6 dilutions from baseline to D28 (0.004 to 0.12 mg/L; 32-fold). Another participant developed C. albicans biliary infection, assessed as a clinical relapse (and died on D30 due to interstitial pneumonia). The biliary C. albicans isolate showed no increase in manogepix MIC compared with the baseline isolate (MIC: 0.008 mg/L).

Two additional participants died during the follow-up period (D15: cardiopulmonary arrest, and D39: voluntary euthanasia [legal and physician administered in Belgium]). Eleven (55.0%) of 20 participants had sustained treatment success at the end of the follow-up period.

Overall survival at D30

Overall survival at D30 in the mITT population was 85% (17/20). Of the three deaths up to and including D30, none were considered related to fosmanogepix. The DRC judged that candidaemia may have been contributory to two of the deaths: one death due to subsequent Acinetobacter sepsis (described above), and one due to worsening interstitial pneumonia in a participant with C. albicans cultured from the biliary tract and assessed as a relapse. The third death was due to cardiopulmonary arrest attributed to progression of underlying metastatic cancer. The median Kaplan–Meier estimate of time to death was not estimable.

Time to first negative blood culture

All 20 participants in the mITT population had a confirmed diagnosis of candidaemia at screening. Seven of these participants had positive cultures from blood samples taken immediately prior to fosmanogepix treatment: the mean time to first negative blood culture was 2.4 days (SD = 1.13). The median (95% CI) Kaplan–Meier estimate of time to first negative blood culture was 2.0 (1.0–4.0) days.

Mycological outcome

Eradication was defined as a negative blood culture for Candida spp. in the absence of concomitant antifungal therapy through the EOST/EOT. A total of 80% (16/20) and 75% (15/20) of participants had eradicated Candida spp. infection at EOST and EOT visits, respectively.

Susceptibility and resistance

For all baseline Candida species cultured from blood, low manogepix CLSI MIC values were observed (MICrange: 0.002–0.03 mg/L) (Table 4). The manogepix MICs of the isolated Candida species at the EOST for each of the four participants who experienced treatment failure were within the same range as manogepix MICs at baseline. The one isolate with a shift in MIC value from baseline was from a participant with C. glabrata candidaemia (described above) and ascending cholangitis secondary to common bile duct obstruction attributed to underlying pancreatic cancer. This participant experienced treatment success at the EOST but had recurrent candidaemia at 2 week follow-up after the EOT.

Table 4.

Summary of baseline Candida spp. and susceptibility—mITT population

| Participants | Species | MIC (mg/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manogepix | Anidulafungin | Fluconazole | Amphotericin B | ||

| 1 | C. parapsilosis | 0.008 | 4 | 0.25 | 4 |

| 2 | C. parapsilosis | 0.004 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 3 | C. glabrata | 0.03 | 0.03 | 4 | 1 |

| 4 | C. glabrata | 0.016 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 5 | C. parapsilosis | 0.016 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 6 | C. glabrata | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 7 | C. glabrata | 0.016 | 0.25 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | C. glabrata | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 9 | C. glabrata | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 10 | C. glabrata | 0.004 | 0.12 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | C. glabrata | 0.008 | 0.06 | 2 | 1 |

| 12a |

C. dubliniensis and

C. glabrata |

0.004 0.004 |

0.016 0.12 |

0.12 1 |

1 1 |

| 13 | C. albicans | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| 14b | C. albicans | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| 15 | C. albicans | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 4 |

| 16 | C. albicans | 0.008 | 0.03 | 2 | 2 |

| 17 | C. albicans | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 2 |

| 18 | C. albicans | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| 19 | C. albicans | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| 20 |

C. albicans and

C. glabrata |

0.004 0.016 |

0.03 0.25 |

0.12 0.5 |

2 2 |

CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; DRC, data review committee; EOT, end of treatment; ITT, intent-to-treat; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; spp., species.

Patient with recurrent candidaemia; recurrence (mycological) defined as a mycologically confirmed infection with the same baseline Candida spp. during the 4 weeks after the EOT.

Patient with clinical relapse; relapse (DRC assessment) defined as re-occurrence of Candida in blood culture, or from other infection sites, during the follow-up period, or diagnostic parameters indicative of recurrence or late spread of the Candida infection.

Safety

Overall, 20/21 (95.2%) participants experienced an AE (Table 5). AEs were consistent with the profile of participants with candidaemia and related underlying conditions. AEs that resulted in discontinuation of fosmanogepix (n = 3) included congestive cardiac failure, leucopenia and sepsis, but these were not considered related to fosmanogepix.

Table 5.

TEAEs (safety population)

| Category | Total (N = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Participants n (%) |

Events n |

|

| TEAEs | ||

| All TEAEs | 20 (95.2) | 126 |

| Study drug-related TEAEs | 1 (4.8) | 1 |

| TEAEs by maximum severitya | ||

| All TEAEs | ||

| Mild (CTCAE Grade 1) | 4 (19.0) | 4 |

| Moderate (CTCAE Grade 2) | 3 (14.3) | 8 |

| Severe (CTCAE Grade 3) | 5 (23.8) | 8 |

| Life-threatening (CTCAE Grade 4) | 3 (14.3) | 3 |

| Death (CTCAE Grade 5) | 5 (23.8) | 5 |

| Study drug-related TEAEs | ||

| Moderate (CTCAE Grade 2) | 1 (4.8) | 1 |

| SAEs | ||

| All SAEs | 9 (42.9) | 19 |

| Study drug-related SAEs | 0 (0.0) | 0 |

| TEAEs leading to discontinuation of drug | ||

| All TEAEs | 3 (14.3) | 3 |

| Study drug-related TEAEs | 0 | 0 |

| AEs leading to discontinuation of study | ||

| All AEs | 5 (23.8) | 5 |

| Study drug-related TEAEs | 0 | 0 |

Percentages were calculated using the number of participants in the column heading as the denominator. TEAEs were defined as AEs occurring on or after the first dose of study drug. AE, adverse event; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Both participants and events are listed by maximum severity.

The most common TEAEs were diarrhoea, vomiting, peripheral oedema and pleural effusion, observed in three participants each (14.3%). The highest proportions of TEAEs were Grade 3 or Grade 5 in severity. Vomiting (n = 3; Grade 1) was not temporally associated with oral administration and was not considered to be related to fosmanogepix. Only one AE, decreased platelet count of moderate severity (below normal from D3 to EOST, with the lowest value of 82 × 109/L on D11), was considered possibly related to fosmanogepix. The event resolved spontaneously, the dose of fosmanogepix was not changed, and no further action was taken. There were no treatment-related serious adverse events (SAEs).

There were five deaths during the study period, none of which were judged to be related to fosmanogepix by the Investigator. Of these, three deaths occurred up to D30 (described above), and two additional deaths occurred during the follow-up period, on D39 and D42. The death of both participants was due to underlying urological malignancies. Candidaemia was not assessed by the DRC as contributory to death in either case.

No clinically meaningful laboratory safety concerns were observed, apart from minor fluctuations in some liver enzymes (e.g. AST, total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase), which were not considered AEs.

Renal impairment

Two-thirds (14/21) of participants in the ITT population had renal impairment at study entry: 7 had mild impairment (glomerular filtration rate, GFR: 60–89 mL/min per 1.73 m2), 5 had moderate impairment (GFR: 30–59 mL/min per 1.73 m2) and 2 had severe impairment (GFR: 15–29 mL/min per 1.73 m2). None of these participants had worsening of renal impairment while receiving treatment with fosmanogepix.

The majority (12/14; 86%) completed treatment with fosmanogepix, and were considered to be treatment successes at the EOST, including 6 of 7 participants with moderate or severe renal impairment at study entry. The majority of renally impaired participants 11/14 (79%) were alive at D30.

None of the participants with moderate or severe renal impairment had elevated blood levels of manogepix. A population pharmacokinetics (PK; described in Material S2) analysis of a limited number of serum samples suggested that there was no difference in manogepix exposure between participants with normal or mild renal function and those with moderate to severe renal impairment (Table 6). There was no evidence of drug-related nephrotoxicity.

Table 6.

PK summary statistics stratified by renal function

| Parameter | Median (min–max) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal/mild | Moderate/severe | ||

| AUC on D1 | 129.0 (57.1–235.0) | 106.0 (69.1–193.0) | 0.576 |

| AUC on D2 | 150.0 (62.0–259.0) | 112.0 (70.6–218.0) | 0.149 |

| AUC on D3 | 132.0 (68.9–244.0) | 96.3 (79.4–198.0) | 0.172 |

| Average AUC on D1–2 | 136.0 (59.7–247.0) | 110.0 (70.0–205.0) | 0.287 |

| Average AUC on D1–3 | 140.0 (62.9–246.0) | 111.0 (73.1–203.0) | 0.287 |

| Average AUC on all days of therapy | 133 (73.7–235.0) | 100.0 (88.3–176.0) | 0.094 |

| CL (L/h) | 2.5 (1.8–3.9) | 3.5 (2.3–4.7) | 0.094 |

| t ½, α (h) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 1.5 (1.0–2.7) | 0.488 |

| t ½, β (h) | 62.4 (18.3–127.0) | 47.2 (24.3–117.0) | 0.585 |

| V ss (L) | 192.0 (82.2–550.0) | 263 (88.3–541.0) | 0.799 |

AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; CL, clearance; t1/2 α, half-life for distribution phase; t1/2 β, half-life for elimination phase; Vss, volume of distribution at steady state.

Discussion

This open-label, single-arm study evaluated the efficacy and safety of fosmanogepix in the treatment of candidaemia in non-neutropenic participants, including those with baseline renal impairment.

The enrolled participant population was similar to prior candidaemia studies and included participants with significant comorbidities (including cancer and surgical complications).23–26 The mean APACHE score was comparable to that reported in a quantitative review of invasive candidiasis studies.5 Patients treated with fosmanogepix demonstrated rapid clearance of Candida from the bloodstream. Because most studies evaluating bloodstream infections allow the use of ≤2 days of antimicrobial treatment before initiating investigational treatment, a proportion of enrolled participants did not have positive blood cultures immediately prior to starting fosmanogepix. In participants with a positive blood culture for Candida at baseline, the mean time to first negative blood culture was 2.4 days. This protocol limited study therapy with fosmanogepix to 14 days, but this did not influence the recommendation to complete 14 days of effective antifungal therapy following the first negative blood culture per IDSA guidelines.18

Treatment success at the EOST was 80.0% in the mITT population, and success was maintained at the EOT, and at 2 and 4 weeks after the EOT by 75.0%, 60.0% and 55.0% of participants, respectively. Those participants with persistent positive blood cultures at the EOST (15%) either had inadequate source control (femoral vein thrombosis and multiple changes of peripherally inserted central catheter lines, n = 2) or inadequate urothelium/blood barrier (urothelial adenocarcinoma, n = 1). Therefore, the cultures remained persistently positive at the EOST for reasons unrelated to study treatment.

The baseline Candida species in our study had low manogepix MIC values (MICrange: 0.002–0.03 mg/L) and remained within the same range at various timepoints (EOST, EOT and follow-up) except for a single case in which an increase in MIC of manogepix was observed for a C. glabrata isolate associated with a relapse of candidaemia. This finding of recurrent candidaemia at 2 week follow-up after the EOT (as described above) was probably due to the advanced Candida infection in this participant that may have required a longer duration of treatment. However, treatment failures were not associated with changes in fosmanogepix susceptibility. Previous studies have demonstrated that manogepix has in vitro and in vivo activity against several resistant fungal pathogens, including azole- and echinocandin-resistant Candida, azole-resistant Aspergillus, and intrinsically resistant rare moulds including Fusarium, Lomentospora, Scedosporium and some Mucorales spp.6,9,27–31

On D30, 15% of participants did not survive. In general, mortality among patients with candidaemia is estimated to be approximately 25%.1 The treatment response and mortality rates seen with fosmanogepix are in the range reported in previous studies evaluating azoles and echinocandins,23–26 and with good tolerance and rapid clearance.6

Patients with candidaemia often have underlying renal insufficiency or develop acute kidney injury during therapy, and clinical outcomes are generally poor.32,33 Similar to published candidaemia studies,34–36 the majority of study participants had some degree of underlying renal impairment at enrollment. Rates of treatment success at the EOST and survival at D30 in these participants were comparable to the overall study population, with no evidence of worsening of renal function during the treatment period. No impact of renal impairment was observed on the efficacy of fosmanogepix. Modelled PK parameters were similar between participants with normal to mild renal impairment and participants with moderate to severe renal impairment. Furthermore, there was no evidence of drug-related renal toxicity.

Fosmanogepix was well tolerated with no treatment-related SAEs or discontinuations. The three participants who died through D30 had serious underlying conditions, consistent with comorbidities associated with a representative candidaemia population. These deaths were considered unrelated to fosmanogepix. Approximately 50% of participants transitioned from IV to oral therapy, with no discernible change in the safety profile.

Limitations of the study include small sample size and the single-arm design. The findings of this study should not be generalized to candidaemia patients with neutropenia. Additionally, there were no patients enrolled with infections caused by C. auris. However, another Phase 2 study conducted in C. auris showed fosmanogepix to be safe, efficacious and well tolerated.37 In common with other studies of candidaemia, participants were able to receive ≤48 h of antifungal drug treatment prior to enrollment, and consequently some participants had negative blood cultures prior to initiating fosmanogepix.

Acknowledging these limitations, fosmanogepix was efficacious in participants with candidaemia, including in participants with poor prognostic risk factors (i.e. renal impairment and serious underlying disease). The response at the EOST and D30 survival was within the range of other antifungal drug classes.23–26 In addition, fosmanogepix was safe, well tolerated and showed no evidence of hepatic or renal toxicity. A Phase 1 study (NCT05582187) in adults with varying degrees of hepatic impairment is currently underway. Overall, the results of our study provide preliminary evidence of efficacy and support the further study of fosmanogepix, representing a first-in-class antifungal with a novel MOA, for the treatment of invasive fungal infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all the investigators and participants who contributed to this study, and Mahmoud Ghannoum (PhD) and staff at NTS Ventures for susceptibility testing. We are grateful to Mili Kapoor who assisted with the in vitro data collection and analysis. Further, we also acknowledge Michelle M. Merrigan (PhD) and Priyanka Nair (MDS; employee of Pfizer Inc.) for providing medical writing assistance under the guidance of the authors, and Kripa Gopal Madnani (PhD, CMPP™; employee of Pfizer Inc.) for editorial assistance.

Contributor Information

Peter G Pappas, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA.

Jose A Vazquez, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia/Augusta University, Augusta, GA, USA.

Ilana Oren, Infectious Disease Unit, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Galia Rahav, Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel; Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Mickael Aoun, Department of Internal Medicine, Institut Jules Bordet, Brussels, Belgium.

Pierre Bulpa, Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospital Mont-Godinne, CHU UCL Namur, Yvoir, Belgium.

Ronen Ben-Ami, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel; Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Ricard Ferrer, Vall d’Hebron Hospital Universitari, Shock, Organ Dysfunction, and Resuscitation (SODIR) Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca (VHIR), Vall d´Hebron Barcelona Hospital Campus, Passeig de la Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain.

Todd Mccarty, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA.

George R Thompson, III, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, and Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA, USA.

Haran Schlamm, Amplyx Pharmaceuticals Inc., San Diego, CA, USA.

Paul A Bien, Pfizer, Inc., Groton, CT, USA.

Sara H Barbat, Amplyx Pharmaceuticals Inc., San Diego, CA, USA.

Pamela Wedel, Amplyx Pharmaceuticals Inc., San Diego, CA, USA.

Iwona Oborska, Amplyx Pharmaceuticals Inc., San Diego, CA, USA.

Margaret Tawadrous, Pfizer, Inc., Groton, CT, USA.

Michael R Hodges, Amplyx Pharmaceuticals Inc., San Diego, CA, USA.

Funding

The study was funded by Amplyx, now a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc.

Transparency declarations

Peter G. Pappas received research funding from Amplyx, Astellas, Cidara, F2G, Mayne and Scynexis, and was a scientific advisor for Amplyx, Mayne and Scynexis. Jose A. Vazquez provided advisory and consultancy services to Amplyx, Cidara, F2G and Scynexis. Ilana Oren, Mickael Aoun and Pierre Bulpa have no financial or other conflicts of interest to declare. The late Dr Oren was a principal investigator at one of the major study sites and contributed to study design, methodology, and reviewing and editing of all manuscript drafts prior to the final draft. Galia Rahav received grant support from AbbVie, Gilead, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis and Shionogi, provided advisory and consultancy services to AbbVie, Gilead, MSD and Pfizer, and served on the speaker bureaus for AbbVie, Gilead, MSD and Pfizer. Ronen Ben-Ami received grant support from the Israeli Ministry of Science and Technology and the Israel Science Foundation, and provided advisory and consultancy services to Gilead, Merck, Pfizer and Teva. Ricard Ferrer received consulting and conference fees from Gilead, MSD, Pfizer, Shionogi and Thermo Fisher. Todd McCarty received grant support from Amplyx, Cidara, GenMark Dx, NIH, Pfizer and T2 Biosystems, provided advisory and consultancy services to T2 Biosystems, and served on the speaker bureau for GenMark Dx. George R. Thompson III received consulting and research support from Amplyx, Astellas, Cidara, F2G and Mayne. Haran Schlamm, Sara H. Barbat, Pamela Wedel, Iwona Oborska and Michael R. Hodges were previous employees or consultants of Amplyx (now a Pfizer Inc. subsidiary). Iwona Oborska was a consultant for Amplyx, previously a Pfizer employee, and Pfizer shareholder. Michael R. Hodges was a consultant for Pfizer, previously a Pfizer employee and holds Pfizer stock. Paul A. Bien and Margaret Tawadrous are employees of Pfizer and hold Pfizer stock.

Data availability

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Material S1a, S1b and S2 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Tsay SV, Mu Y, Williams Set al. . Burden of candidemia in the United States, 2017. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: e449–53. 10.1093/cid/ciaa193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spivak ES, Hanson KE. Candida auris: an emerging fungal pathogen. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56: e01588-17. 10.1128/JCM.01588-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumar K, Askari F, Sahu MSet al. . Candida glabrata: a lot more than meets the eye. Microorganisms 2019; 7: 39. 10.3390/microorganisms7020039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giacobbe DR, Maraolo AE, Simeon Vet al. . Changes in the relative prevalence of candidaemia due to non-albicans Candida species in adult in-patients: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Mycoses 2020; 63: 334–42. 10.1111/myc.13054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andes DR, Safdar N, Baddley JWet al. . Impact of treatment strategy on outcomes in patients with candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis: a patient-level quantitative review of randomized trials. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54: 1110–22. 10.1093/cid/cis021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shaw KJ, Ibrahim AS. Fosmanogepix: a review of the first-in-class broad spectrum agent for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel) 2020; 6: 239. 10.3390/jof6040239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruping MJ, Vehreschild JJ, Cornely OA. Antifungal treatment strategies in high risk patients. Mycoses 2008; 51Suppl 2: 46–51. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01572.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nami S, Aghebati-Maleki A, Morovati Het al. . Current antifungal drugs and immunotherapeutic approaches as promising strategies to treatment of fungal diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 110: 857–68. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miyazaki M, Horii T, Hata Ket al. . In vitro activity of E1210, a novel antifungal, against clinically important yeasts and molds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 4652–8. 10.1128/AAC.00291-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watanabe NA, Miyazaki M, Horii Tet al. . E1210, a new broad-spectrum antifungal, suppresses Candida albicans hyphal growth through inhibition of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 960–71. 10.1128/AAC.00731-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McLellan CA, Whitesell L, King ODet al. . Inhibiting GPI anchor biosynthesis in fungi stresses the endoplasmic reticulum and enhances immunogenicity. ACS Chem Biol 2012; 7: 1520–8. 10.1021/cb300235m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murakami Y, Siripanyapinyo U, Hong Yet al. . PIG-W is critical for inositol acylation but not for flipping of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor. Mol Biol Cell 2003; 14: 4285–95. 10.1091/mbc.e03-03-0193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kapoor M, Moloney M, Soltow QAet al. . Evaluation of resistance development to the Gwt1 inhibitor manogepix (APX001A) in Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 64: e01387-19. 10.1128/AAC.01387-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mansbach R, Shaw KJ, Hodges MRet al. . Absorption, distribution, and excretion of 14C-APX001 after single-dose administration to rats and monkeys. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4: S472. 10.1093/ofid/ofx163.1209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hodges MR, Ople E, Shaw KJet al. . Phase 1 study to assess safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of single and multiple oral doses of APX001 and to investigate the effect of food on APX001 bioavailability. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4: S534. 10.1093/ofid/ofx163.1390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mueller SW, Kedzior SK, Miller MAet al. . An overview of current and emerging antifungal pharmacotherapy for invasive fungal infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2021; 22: 1355–71. 10.1080/14656566.2021.1892075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310: 2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DRet al. . Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: 409–17. 10.1093/cid/civ1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. CLSI . Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts—Fourth Edition: M27. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arendrup MC, Meletiadis J, Mouton JWet al. . EUCAST Definitive Document E.DEF 7.3.2. Method for the Determination of Broth Dilution Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antifungal Agents for Yeasts. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Files/EUCAST_E_Def_7.3.2_Yeast_testing_definitive_revised_2020.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. CLSI . Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts—Second Edition: M60. 2020.

- 22. SAS Institute Inc . Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.3. Procedure Guide. https://support.sas.com/documentation/onlinedoc/base/procstat93m1.pdf.

- 23. Reboli AC, Rotstein C, Pappas PGet al. . Anidulafungin versus fluconazole for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2472–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa066906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pappas PG, Rotstein CM, Betts RFet al. . Micafungin versus caspofungin for treatment of candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45: 883–93. 10.1086/520980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kullberg BJ, Viscoli C, Pappas PGet al. . Isavuconazole versus caspofungin in the treatment of candidemia and other invasive candida infections: the ACTIVE trial. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68: 1981–9. 10.1093/cid/ciy827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thompson GR, Soriano A, Skoutelis Aet al. . Rezafungin versus caspofungin in a phase 2, randomized, double-blind study for the treatment of candidemia and invasive candidiasis: the STRIVE trial. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e3647–e55. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhu Y, Kilburn S, Kapoor Met al. . In vitro activity of manogepix against multidrug-resistant and panresistant Candida auris from the New York outbreak. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64: e01124-20. 10.1128/AAC.01124-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wiederhold NP, Najvar LK, Fothergill AWet al. . The investigational agent E1210 is effective in treatment of experimental invasive candidiasis caused by resistant Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 690–2. 10.1128/AAC.03944-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pfaller MA, Huband MD, Flamm RKet al. . In vitro activity of APX001A (manogepix) and comparator agents against 1,706 fungal isolates collected during an international surveillance program in 2017. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e00840-19. 10.1128/AAC.00840-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rivero-Menendez O, Cuenca-Estrella M, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. In vitro activity of APX001A against rare moulds using EUCAST and CLSI methodologies. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 1295–9. 10.1093/jac/dkz022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gebremariam T, Alkhazraji S, Alqarihi Aet al. . Fosmanogepix (APX001) is effective in the treatment of pulmonary murine mucormycosis due to Rhizopus arrhizus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64: e00178-20. 10.1128/AAC.00178-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barchiesi F, Orsetti E, Gesuita Ret al. . Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcome of candidemia in a tertiary referral center in Italy from 2010 to 2014. Infection 2016; 44: 205–13. 10.1007/s15010-015-0845-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chakrabarti A, Sood P, Rudramurthy SMet al. . Incidence, characteristics and outcome of ICU-acquired candidemia in India. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41: 285–95. 10.1007/s00134-014-3603-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zheng Y-J, Xie T, Wu Let al. . Epidemiology, species distribution, and outcome of nosocomial Candida spp. bloodstream infection in Shanghai: an 11-year retrospective analysis in a tertiary care hospital. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2021; 20: 34. 10.1186/s12941-021-00441-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Agnelli C, Valerio M, Bouza Eet al. . Prognostic factors of Candida spp. bloodstream infection in adults: a nine-year retrospective cohort study across tertiary hospitals in Brazil and Spain. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022; 6: 100117. 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gold JAW, Seagle EE, Nadle Jet al. . Treatment practices for adults with candidemia at 9 active surveillance sites—United States, 2017–2018. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: 1609–16. 10.1093/cid/ciab512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vazquez JA, Pappas PG, Boffard Ket al. . Clinical efficacy and safety of a novel antifungal, fosmanogepix, in patients with candidemia caused by Candida auris: results from a Phase 2 trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023; 67: e0141922. 10.1128/aac.01419-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.