Summary

Spatially resolved transcriptomics is revolutionizing our understanding of complex tissues, but scaling these approaches to multiple tissue sections and three-dimensional tissue reconstruction remains challenging and cost prohibitive. In this work, we present a low-cost strategy for manufacturing molecularly double-barcoded DNA arrays, enabling large-scale spatially resolved transcriptomics studies. We applied this technique to spatially resolve gene expression in several human brain organoids, including the reconstruction of a three-dimensional view from multiple consecutive sections, revealing gene expression heterogeneity throughout the tissue.

Keywords: spatial transcriptomics, cerebral organoids, gene regulatory programs, DNA arrays

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We report a DNA array engineering method for spatially resolved transcriptomics (SrT)

-

•

DNA arrays enable mapping local gene expression signatures in human brain organoids

-

•

SrT profiling sections of human brain organoids allows a 3D molecular cartography

Motivation

Spatially resolved transcriptomics has the potential to enable major progress in the understanding of complex tissue organization; however, the cost of current methods can be a prohibitive barrier to their use. We therefore developed a cost-effective strategy for manufacturing molecularly double-barcoded DNA arrays that allows large-scale spatially resolved transcriptomics studies. We verified this potential by analyzing consecutive sections of human cerebral organoids, producing a three-dimensional molecular tissue reconstruction.

Lozachmeur et al. describe a cost-effective strategy for manufacturing molecularly double-barcoded DNA arrays, enabling large-scale, spatially resolved transcriptomics studies. Array-based profiling of local gene expression signatures over multiple human brain organoids allows a three-dimensional molecular cartography and demonstrates the inherent heterogeneity of this complex tissues.

Introduction

Understanding tissue complexity by the characterization of gene programs associated with the various cells/cell types that are composing them represents a major challenge in systems biology. Recent developments in spatially resolved transcriptomics (SrT) are revolutionizing the way to scrutinize tissue complexity without losing its spatial architecture. Among the various available strategies, those based on the use of a “barcoded” physical support (for capturing the molecular information) combined with the use of next-generation DNA sequencing and bioinformatics demultiplexing processing (for tracing back the local positioning of the assessed transcriptomes) are providing means to landscape large tissue sections and interrogate gene expression in an unbiased manner.1

Barcoded DNA microarrays, initially described by Stähl et al. for SrT applications,2 allow us to capture messenger RNA thanks to DNA probes presenting a poly(T) sequence and provide local transcriptome positional information thanks to a unique molecular barcode associated with each of the DNA probes. While powerful, this approach is rather expensive, notably due to the high number of unique DNA probes required for their manufacturing.

Here, we present an improved strategy for manufacturing molecularly barcoded DNA arrays for SrT. This method significantly reduces the manufacturing costs by combining two probes harboring molecular barcodes for the x and y coordinates instead of using a single molecular barcode per region. This strategy has been used for establishing a molecular cartography of several cerebral organoids including a three-dimensional analysis thanks to the mapping of 15 consecutive sections.

Results

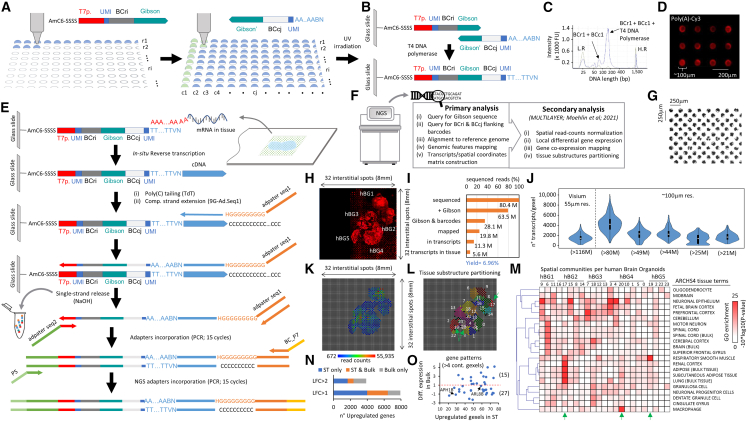

Instead of printing long DNA oligonucleotides (>100 nt) presenting a unique 18-mer barcode sequence and a 20-nt-length poly(T) capture region as described by Stäh et al.,2 we have engineered a strategy based on the use of two DNA oligonucleotides harboring two distinct sets of molecular barcodes (barcodes for rows [BCrs] and barcodes for columns [BCcs]; Figure 1A). In addition, BCr probes host an amino C6 linker modification at the 5′ end for UV crosslinking, a T7 promoter sequence, and a 30-nt-length adapter at the 3′ end, previously used for Gibson assembly reactions.3 A complementary Gibson sequence is retrieved at the 3′ end of the second printed DNA oligonucleotide (BCc), as well as a 20-nt-length poly(A) extremity at its 5′ end. During the manufacturing process, BCr probes are printed as rows, such that each row presents oligonucleotides with a different barcode sequence (BCr1, BCr2,…BCri; Figure 1A). Then, the second type of oligonucleotides (BCc) are printed as columns, on top of the previously printed oligonucleotides, such that each column contains oligonucleotides with a different barcode sequence (BCc1, BCc2,…BCcj).

Figure 1.

Double-barcoded DNA arrays manufactured for spatially resolved transcriptomics (SrT)

(A) Strategy for printing DNA arrays based on the deposition of two types of oligonucleotides harboring distinct molecular barcodes (per row: BCri; per column: BCci). Both oligonucleotides share a complementary sequence (Gibson). The 5′ end of the BCri oligonucleotide contains an amino C6 linker modification, followed by 4 “S” (cytosine or guanine) nucleotides, for UV crosslinking.

(B) Once BCcj primers are deposited on top of the printed BCri oligonucleotides, the glass slide is UV irradiated for covalent crosslinking, followed by probes’ elongation thanks to their complementary Gibson region. This elongation process (T4 DNA polymerase) generates a long probe composed by a T7 promoter (T7p), two unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), two molecular barcodes flanking the complementary Gibson sequence, and a poly(T).

(C) Electropherogram demonstrating the generation of a long probe (116 nt length) after T4 DNA polymerase elongation.

(D) DNA array scan (TRITC filter) after incubation of a double-barcoded DNA array with poly(A)-Cy3-labeled molecules.

(E) NGS-library preparation strategy for capturing messenger RNA (mRNA) from tissues deposited on top of the double-barcoded manufactured DNA arrays.

(F) Bioinformatics pipeline in use for SrT.

(G) Micrograph illustrating a part of a manufactured DNA array composed by 32 × 32 printed spots in an interstitial manner, leading to a density of 2,048 different probes.

(H) Scan of a DNA array (TRITC filter) hosting a cryosection of multiple human brain organoids (hBGs embedded together), after cDNA labeling with dCTP-Cy3. Note that, due to our manual scanning, only regions presenting tissue sections were imaged.

(I) Fraction of sequenced reads retrieved from library preparation in (H) after the primary bioinformatics analysis. Yield corresponds to the ratio between the reads retrieved in transcripts in the tissue region (5.6 million) and the initial number of sequenced reads (80.4 million).

(J) Violin plots illustrating the number of transcripts per gexel (gene expression elements, i.e., a spatial spot) retrieved in several SrT assays performed with double-barcoded manufactured DNA arrays at different sequencing depths (80–20 million reads), in comparison with an assay with commercial DNA array (Visium 10× Genomics). Note that the Visium assay has been performed with >100 million reads.

(K) Digitized view of the SrT assay performed in (H) generated with MULTILAYER from the 5.6 million reads retrieved in known transcripts in tissue regions.

(L) Molecular tissue substructure partitioning performed by MULTILAYER based on gene co-expression pattern signatures (≥4 contiguous gexels per pattern). Each color corresponds to one of the 24 revealed substructures.

(M) Tissue terms enrichment analysis per substructure retrieved in (L) and classified by their localization within the identified hBGs. Green arrows: spatial substructures (19, 20, 17) enriched for tissue terms not related to neuroectodermal differentiation. Spatial location of these structures is also highlighted in (L) (green arrows).

(N) Comparison between ST (in H) and bulk transcriptomics assessed in hBGs. LFC, fold change in log2.

(O) Comparison between the number of upregulated gexels in ST retrieved in gene patterns (>4 contiguous gexels) and the differential expression detected in bulk transcriptomics. Red dashed line highlights an LFC of 1. Two genes (APH1B and ARL8B) are highlighted as not found differentially expressed in bulk but presenting an important number of upregulated gexels in the ST assay.

Depositing probes on top of previously printed oligonucleotides is performed at a high accuracy with the pico-litter spotter Sciflexarrayer S3 (Scienion). Thanks to two high-resolution cameras, this instrument allows us to control the volume of the drop (∼250 pL) and its potential deviation from the printing axisand to verify the quality of the printout at the end of the process (Figure S1).

Printed DNA arrays are first UV irradiated to immobilize the DNA probes, then they are covered with a solution containing T4 DNA polymerase for elongating the hybridized oligonucleotides (Figure 1B).This step generates in situ a 116-nt-length DNA probe presenting a poly(T) sequence at the 3′ end and two distinct barcodes providing positional information (row/column coordinates) (Figure 1C). The capacity of the double-barcoded DNA arrays to capture poly(A) sequences was verified by their exposure to poly(A)-cyanine-3 (Cy3)-labeled oligonucleotides (Figure 1D). Importantly, the aforementioned manufacturing strategy of double-barcoded DNA arrays requires only 64 oligonucleotides for generating 1,024 different DNA probes, or only 128 oligonucleotides for reaching a density of 4,096 different probes, similar to the currently improved DNA arrays commercialized by 10× Genomics. Hence, the production costs of the double-barcoded arrays are 16- to 32-fold lower than those presenting a single 18-mer molecular barcode.

In order to use the aforementioned double-barcoded DNA arrays for SrT, we have engineered a molecular biology strategy in which the messenger RNA retrieved in tissue sections is converted in complementary DNA (cDNA) in situ, followed by a poly(C) tailing with Terminal transferase, as described in previous next-generation sequencing (NGS)-library preparation strategies4,5 (Figure 1E). The poly(C) sequence is used for hybridizing a poly(G)-oligonucleotide, presenting a known adapter at its 5′ end (adapter seq1), and elongated for generating a cDNA strand harboring the captured cDNA sequence, as well as the double-barcoded information. Finally, the complementary strand is released by alkaline treatment and recovered from the DNA array for its transfer into an Eppendorf tube. A second adapter attached to a T7 promoter sequence is used together with a complementary sequence to the adapter seq1 for a first PCR DNA amplification step, followed by a second amplification process incorporating the required adapters for Illumina NGS sequencing (P5; P7 sequences; Figure 1E).

In addition to the molecular biology strategy for SrT assays, we have generated a bioinformatics pipeline targeting the retrieval of the Gibson sequence flanked by two molecular barcodes prior to the alignment to the reference genome, the mapping of genomic features, and the reconstruction of a spatial coordinates matrix associated with the retrieved read counts per transcripts (Figure 1F). The outcome of this primary analysis is processed by our previously described tool, MULTILAYER, which is able to normalize the spatial read-count levels, identify differentially expressed genes in a local context, detect gene co-expression patterns, and perform molecular tissue substructure partitioning.6,7

This double-barcoding strategy has been used for manufacturing DNA arrays composed of 2,048 unique DNA probes (32 × 32 spots printed twice in an interstitial manner; Figure 1G). Then, multiple human brain organoids (hBGs; 4 months of culture) were cryosectioned together and deposited on top of the manufactured DNA arrays. In situ reverse transcription was revealed by the incorporation of dCTP-Cy3 (Figure 1H). NGS of the corresponding SrT library revealed that from a total of ∼80 million reads, 63 million presented the Gibson sequence, but only ∼28 million also presented the required flanking positional barcodes (Figure 1I). Furthermore, ∼20 million reads were mapped to the human genome, from which 5.6 million matched with known transcripts and were retrieved within tissue regions, leading to a yield of ∼7% relative to the total mapped reads. The analysis of multiple other sections at various sequencing-depth levels revealed a yield of spatially captured transcripts ranging between 3.5 and 7%, equivalent to that obtained when using commercial DNA arrays (Visium 10× Genomics [Figure S2]). Importantly, our double-barcoded arrays presented ∼4,000 transcripts per gexel (local gene expression pixels) on average for a sequencing depth of ∼80 million reads, while the assay with Visium DNA arrays revealed less than 2,000 transcripts per gexel, despite the use of >116 million reads. This can be explained by the difference in the number of printed spots and resolution (2,048 spots in our double-barcoded arrays and ∼5,000 spots for Visium arrays) (Figure 1J). Indeed, the use of >40 million reads for SrT with the double-barcoded arrays allowed us to obtain >2,000 transcripts/gexel (Figures 1J and S2).

A digitized view of the analyzed hBGs revealed a SrT map presenting raw read counts ranging between 672 and >55,000 per gexel (Figure 1K). Tissue partitioning, based on localized gene co-expression patterns (≥4 contiguous gexels per pattern; Tanimoto similarity threshold: 25%), revealed 24 molecular tissue substructures (Figures 1L and S3). Tissue term enrichment analysis applied to co-expressed genes retrieved in partitioned regions revealed signatures associated with terms like neuronal epithelium or fetal brain cortex for most of the hBGs, while others like oligodendrocyte, spinal cord, or neuronal progenitor cells were more restricted to a given hBG (Figure 1M). Such differences strongly support the well-described heterogeneity within hBG cultures, further supported by the observation of some tissue substructures presenting tissue terms devoid of neuroectoderm-derived signatures (green arrows; 17, 19, 20; Figures 1L and 1M). Finally, a direct comparison of the upregulated genes detected with the double-barcoded SrT strategy with a bulk transcriptome mapping revealed ∼30% overlap (Figure 1N). Such a difference can be explained by the inherent heterogeneity within hBGs as well as the by sensitivity of SrT assays to reveal local signatures, which are averaged in bulk assays. Indeed, among the 42 upregulated gene expression patterns detected within the analyzed hBGs, 27 are not found upregulated in bulk (Figure 1O). Among them, genes like APH1B (coding for a gamma-secretase subunit, and recently considered as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease8) or ARL8B (GTPase playing a major role in the positioning of interstitial axon branches9) presented >30 upregulated gexels in the SrT map but were not found to be induced in the bulk transcriptome assay (Figures 1O and S3).

One of the major interests to count with a low-cost production of DNA arrays for SrT is the ability to perform a large number of assays, for instance for reconstructing a three-dimensional view of the tissue of interest. Herein, we analyzed fifteen consecutive sections of two hBGs (9 months of culture), covering 600 μm of the tissue thickness (Figure 2A). Among them, nine sections were deposited on double-barcoded DNA arrays for SrT (2,048 probes; Figures 2B and S4). After Illumina sequencing, their processing with MULTILAYER allowed identifying several over-expressed genes across sections, among them CNTNAP2, a member of the neurexin family, involved in synapse formation and essential for neuronal development10 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional spatial transcriptomics view of hBGs

(A) Top: micrograph displaying a tissue section of two hBGs embedded together. Bottom: scheme of the 15 consecutive sections (s26 to s56) collected across both hBGs (left hBG, L-hBG; right hBG, R-hBG). Sections in green were used for immunofluorescence (IF), while sections in black were used for SrT.

(B) Left: scan of a DNA array (TRITC filter) hosting a cryosection (section 27) after cDNA labeling with dCTP-Cy3. Note that, due to our manual scanning, only regions presenting tissue sections were imaged. Middle: SrT digitized view of the corresponding section displaying the number of read counts per gexel. Right: SrT digitized view after applying a compression factor (cf.) of 2× to reduce the matrix to 32 × 32 (condensed spots), leading to a gain in read count intensity.

(C) Three-dimensional view of the upregulation of CNTNAP2 across all sections (LFC > 1). Pseudo-coordinates are computed by aligning all sections relative to the center of the L-hBG and the R-hBG. Colored gexels highlight CNTNAP2 upregulation per tissue section.

(D) Comparison between the IF labeling of the protein Caspr2 (green) and the differential gene expression of CNTNAP2, which codes for this protein in multiple sections across the hBGs. Differential gene expression is computed relative to the average expression of CNTNAP2 within a tissue section. In addition, nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

(E) Number of upregulated genes (LFC > 1) across all sections (green bar plot), specific to a given section (blue bar plots) or shared among at least two sections (orange bar plots).

(F) Left: upregulated genes in consecutive sections. Right: three-dimensional view of the upregulated genes across sections. Colored sections coincide with the color code per section displayed in (C).

(G) Upregulation of the gene GRM4 or GRIA1 across sections, illustrating their distinct regionality within the hBGs.

(H) Comparison between the IF labeling of the protein MGlu4 (coded by GRM4) or GluA1 (coded by GRIA1) and the differential gene expression of their corresponding coding genes.

We have validated the expression of CNTNAP2 by immunostaining the contactin-associated protein CASPR2 in six different sections across the tissue (Figure 2D). Furthermore, regions presenting high levels of CASPR2 immunostaining correlated with CNTNAP2 over-expression observed in consecutive sections, despite the fact that these comparisons are performed in 20-μm-distant sections as well as that we compare protein detection levels with gene over-expression computed relative to the average expression over the whole tissue section.

In addition to CNTNAP2, we have found other 277 genes presenting the same behavior (Figure 2E). Furthermore, between 60 and 500 genes were upregulated specifically in each section, while most of them (up to 2,500 genes) appeared upregulated in more than one section (Figure 2E). Interestingly, these “shared” genes appeared upregulated preferentially up to three consecutive sections across the tissue, covering a distance of ∼150 μm, corresponding to ∼15 cells on average (Figure 2F). Among them, we have focused our attention on the gene GRM4, coding for the glutamate metabotropic receptor 4 (MGLU4), and the gene GRIA1, coding for the glutamate ionotropic receptor AMPA type subunit 1 (GLUA1). As illustrated in Figure 2G, GRM4 appears specifically upregulated within the first sections (section 31 [s31], s34), while GRIA1 has been observed upregulated in s50 and s56. Immunostaining targeting the protein MGLU4 confirmed higher levels of this factor in s30 than in s39, while the protein GLUA1 presented stronger immunolabeling in s55 than in s36. In both cases, a good correlation between the immunolabeling intensity and the gene over-expression signatures in consecutive sections was observed (Figures 2H and S5).

To reveal relevant molecular tissue substructures within the studied hBGs, we have partitioned all consecutive sections based on gene co-expression patterns (≥3 contiguous gexels per pattern; Tanimoto similarity threshold: 10%) (Figure 3A). This analysis revealed up to 16 spatially localized communities per section. Comparing their gene co-expression content per spatial community across sections led to the identification of 33 spatial classes. A network representation of these relationships highlights the presence of spatial classes shared among multiple tissues (e.g., class “0”), with others being specific to consecutive sections (e.g., class “16”) (Figure 3B). Clustering upregulated genes retrieved in three consecutive sections and associated with the aforementioned spatial classes revealed the presence of three major groups based on their spatial localization (Figure 3C). These groups are enriched for a variety of neuronal subtypes (glutamatergic: group “a”; cholinergic: group “c”), including specialized terms like retinal progenitors (group “b”) or taste receptor cells (group “c”) but also glial cells (astrocytes: group “a”; oligodendrocyte precursors (OPCs): groups “a”, “b,” and “c”), in agreement with a complex tissue architecture due to the variety of cell types but also their spatial localization (Figures 3D and S6).

Figure 3.

Gene co-expression signatures across consecutive sections reveals molecular tissue substructures within hBGs associated to a large diversity of cell types

(A) Molecular tissue stratification based on gene co-expression pattern signatures performed by MULTILAYER (≥3 contiguous gexels per pattern; Tanimoto similarity threshold: 10%) A total of 16 different spatial communities (subregions) were identified across all sections. L-hBG/R-hBG, hBGs located either at the left or the right side, respectively.

(B) Network representation of the various spatial communities detected per tissue section and their association to spatial classes, defined as spatial communities sharing common gene co-expression patterns. Colored sections coincide with the color code per section displayed in Figure 2C.

(C) Clustering of the number of genes per spatial classes and associated with 3 consecutive sections revealing three major groups (“a,” “b,” and “c”) (Pearson correlation).

(D) Top panel: cell-type enrichment analysis associated with all three groups (Panglao and CellMarkerAugmented DBs). Bottom panel: three-dimensional view of the spatial classes per tissue section retrieved in all three groups.

Discussion

Overall, we have provided herein a three-dimensional view of the molecular complexity retrieved within human cerebral organoids. As far as we know, together with two other studies,11,12 this is the third report focused on the integration of multiple consecutive spatial transcriptomics, most likely due to the elevated costs associated with these type of assays. We anticipate that the manufacturing strategy for producing double-barcoded DNA arrays reported herein will provide means to democratize the use of SrT assays, for instance for reconstructing three-dimensional molecular landscapes of complex tissues. Indeed, while a diversity of recently developed technological solutions allows either interrogating gene expression in a spatial context in an unbiased manner (e.g., Visium,2 DBiT-seq,13 Stereo-seq14) or by using selected gene panels allowing to reach even (sub)cellular resolution (e.g., MERFISH15), their elevated costs represent a major bottleneck for democratizing their use. Furthermore, most of them are delimited to rather small physical surfaces or require particular dedicated instruments. The technology presented in this study allows us to circumvent several of these drawbacks, including manufacturing costs and custom sizing of the printed surfaces, and even allows us to expand its use to other type of molecular biology strategies.

Limitations of the study

Although the present study demonstrated an innovative strategy for manufacturing DNA arrays dedicated to spatial transcriptomics, the resolution of the assay remains low in comparison to the current commercial solutions. This limitation is further enhanced in this study when addressing small tissues like cerebral organoids, in which fewer gexels are used for stratifying their molecular complexity.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| GluR-1 (E−6) | Santa Cruz | Sc-13152; RRID:AB_627932 |

| mGluR-4 (B-8) | Santa Cruz | Sc-376485; RRID:AB_11149542 |

| CASPR2 (H-10) Alexa Fluor 488 | Santa Cruz | Sc-398454 AF488 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 15140122 |

| mTeSR plus Medium | Stem cell | 100–0276 |

| Matrigel | Corning | 354277 |

| Matrigel | Corning | 354230 |

| DMEM/F12 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 11330–032 |

| KOSR | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 10828–028 |

| glutaMAX | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 35050–038 |

| MEM-NEAA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 11140–050 |

| bFGF | Thermo Fisher Scientific | PHG0264 |

| Y-27632 dihydrochloride | Stem cell Technologies | 72304 |

| SB-431542 | Stem Cell Technologies | 72232 |

| LDN-193189 | Stem Cell Technologies | 72147 |

| N2 supplement | Thermos Fisher Scientific | 17505–048 |

| Neurobasal Medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 21103–049 |

| B27 without vitamin A supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 12587–010 |

| B27 supplement | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 17504–044 |

| Insulin solution | Sigma Merk | I9278-5ML |

| Mercaptoethanol | Thermos Fisher Scientific | 31350010 |

| Trizol RNA isolation | Thermos Fisher Scientific | 15596026 |

| sciSPOT Oligos B& solution | Scienon | CBD-5421-50 |

| T4 DNA polymerase | New England Biolads | M0203L |

| Murine RNAse Inhibitors | New England Biolads | M0314 |

| SuperScript IV | Life Technologies | 18090200 |

| Actinomycin D | Sigma Merk | A1410-2MG |

| Proteinase K | Invitrogen | 4333793 |

| PKD buffer | Quiagen | 1034963 |

| TDT | New England Biolads | M0315 |

| Klenow Exo- | New Englands Biolads | M0212 |

| glycogene | MP | Glyco001 |

| Q5 hot start high fidelity master mix | New Englands Biolads | M0464L |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Ultra Low attachment plates P4 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 144530 |

| Ultra Low attachment plates P6 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 150239 |

| Organoid Embedding Sheet | Stem Cell Technologies | 08579 |

| NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina | New Englands Biolads | E7770 |

| Superfrost Adhesion Microscope Slides | Epredia | J7800AMNZ |

| dATP solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | R0141 |

| dCTP solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | R0151 |

| dGTP solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | R0161 |

| dTTP solution | Thermo Fisher Sientific | R0171 |

| dCTP-Cy3 | Cytivia | PA53021 |

| 20X SSC buffer | Sigma Merk | S6639 |

| Para-formaldheyde | Life Technologies | 28908 |

| PBS | Life Technologies | 70011–036 |

| Cadre génétique, 25 μL (1,0 × 1.0 cm) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | AB0576 |

| Bovine Serum Albumine | Sigma Merk | A9418-10G |

| SDS buffer | Sigma Merk | 71736 |

| NEBNext multiplex oligos for illumina index primer set 1 | New England Biolads | E7335 |

| SPRIselect beads | Beckman Coulter | B23318 |

| Triton 100-X | Sigma Merk | 93443-100ML |

| DAPI solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 62248 |

| Glycerol | Sigma Aldrich | G5516-100ML |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human BJ primary fibroblast | ATCC | CRL-2522 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| BCr generic primer: SSSSGACTCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG WSNNWSNNVNNNNNNNNACATTGAAGAA CCTGTAGATAACTCGCTGT |

Sigma | This paper |

| BCc generic primer: NBAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAWSNNWSN NVNNNNNNNNACAGCGAGTTATCTACAG GTTCTTCAATGT |

Sigma | This paper |

| 2ND strand synthesis primer: GTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTG GGGGGGGGH |

Sigma | This paper |

| Amplification adapter seq 1 primer: GTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

Sigma | This paper |

| Amplification adapter seq2 primer: TACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCG ATCTGACTCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG |

Sigma | This paper |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| SysISTD | This paper | GitHub - SysFate/SysISTD; Zenodo; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8180576 |

| Multilayer | Moehlin et al., STAR Protoc. 2021 Sep 14; 2(4):100823.7https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100823 | https://github.com/SysFate/MULTILAYER; Zenodo; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8180632 |

| Scanning Software | Microvisioneer | manualWSI Microvisioneer |

| Other | ||

| DNA pico litter spotter | Scienion | Sciflexarrayer S3 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Marco Antonio Mendoza-Parra (mmendoza@genoscope.cns.fr, marco-antonio.mendoza-parra@cnrs.fr).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new materials.

Experimental model and study participant details

Human induced Pluripotent Stem (hIPS) cells were obtained by reprogramming of BJ primary fibroblasts obtained from ATCC (CRL-2522), as described in our previous article.16 hIPS were cultured in mTeSR Plus Medium (100–0276 Stem Cell) + Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S) 1% (15140122 Thermo Fisher Scientific) on Matrigel coating (354277 Corning).

Method details

Cerebral organoid formation

Cerebral organoids were cultured by forming embryoid bodies (EBs) using hanging drops (20,000 cells per drop of 22 μL) in EB Formation Medium (for 50 mL: 40 mL DMEM/F12 (11330-032 Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 mL KOSR (10828-028 Thermo Fisher Scientific), 500 μL GlutaMAX (35050-038 Thermo Fisher Scientific), 500 μL MEM-NEAA (11140-050 Thermo Fisher Scientific), 500 μL P/S supplemented just before use with bFGF (PHG0264 Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4 ng/mL, Y-27632 dihydrochloride (ROCK Inhibitor, 72304 Stem Cell Technologies) at 50 μM, SB-431542 (72232 Stem Cell Technologies) at 10 μM and LDN-193189 (72147 Stem Cell Technologies) at 100 nM). After 2–3 days as hanging drops, EBs were transferred in 24 well Ultra Low Attachment plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific P24; 144530 “untreated Nunc”) with EB Formation Medium (same as above except that ROCK Inhibitor is used at 20 μM), to refresh 2 days after transfer. After 1 week in EB Formation Medium, EBs were transferred in Neural Induction Medium (for 50 mL: 48.5mL DMEM/F12, 500 μL N2 Supplement (17505-048 Thermo Fisher Scientific), 500 μL GlutaMAX, 500 μL P/S, 500 μL MEM-NEAA) until embedding in Matrigel Matrix (354230 Corning) using an Organoid Embedding Sheet (08579 Stem Cell Technologies). After embedding, droplets were put in 6-well Ultra Low Attachment Plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific P6: 150239 “untreated Nunc”) in Expansion Medium without vitamin A (for 50 mL: 24 mL DMEM/F12, 24 mL Neurobasal Medium (21103-049 Thermo Fisher Scientific), 500 μL GlutaMAX, 500 μL P/S, 500 μL B27 without Vitamin A Supplement (12587-010 Thermo Fisher Scientific), 250 μL N2 Supplement, 250 μL MEM-NEAA, 12.5 μL Insulin solution, 0.5 μL 2-Mercaptoethanol). After 4 days in Expansion Medium, Organoids were transfered to Maturation Medium with Vitamin A (same as Expansion Medium, except B27 without Vitamin A is replaced by B27 Supplement (17504-044 Thermo Fisher Scientific)) and cultured under shaking at 60 rpm (Infors Celltron Orbital Shaker) with refresh of medium once a week. Human brain organoids used in this study were collected either at 4 or 9 months of culture by snap-freezing in isopentane and embedded in OCT prior cryosectioning.

Bulk transcriptomics for human brain organoids

For Bulk RNA-seq transcriptomics, a human brain organoid cultured during 4 months has been dissociated in TRIzol RNA isolation reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific 15596026). Extracted RNA has been processed with the NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (E7770). hiPS cells were also processed with TRIzol RNA isolation reagent and NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit. Libraries were sequenced within the French National Sequencing Center, Genoscope (150-nt pair-end sequencing; NovaSeq Illumina).

Both bulk human brain organoid and hiPS control sequenced samples were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19; Bowtie 2.1.0 under default parameters). Mapped reads were associated with known transcripts with featureCounts.17 Differential expression analysis between bulk human brain organoid and iPS control readouts was done with DESeq2 R package.

DNA arrays manufacturing

DNA arrays for spatially resolved transcriptomics were manufactured by depositing two types of complementary oligonucleotides, herein defined as “Barcode for rows (BCr)” and “Barcode for columns (BCc)” hosting sequences. The BCr oligonucleotide presents an amino C6 linker at the 5′ extremity, followed by four G or C nucleotides (S), a T7 promoter sequence (GACTCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG), a unique molecular idenfitier (UMI: WSNNWSNNV), a molecular barcode (8 nucleotides) associated to the printed row in the DNA array, and a 30 nucleotides long adapter sequence with a GC-content of 40%, previously used for Gibson assembly reactions3 (herein named as Gibson sequence: “ACATTGAAGAACCTG-TAGATAACTCGCTGT”).

Similarly, the BCc oligonucleotide is composed by “NBAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA” sequence at the 5′ extremity (where B corresponds to any nucleotide except A), a unique molecular idenfitier (UMI: WSNNWSNNV), a molecular barcode (8 nucleotides) associated to the printed column in the DNA array, and a complementary Gibson sequence.

Oligonucleotides are diluted to 5 μM in presence of sciSPOT Oligos B1 solution (Scienion CBD-5421-50) in a 96 wells plate and stored at −20°C for long storage.

DNA arrays were printed onto Superfrost Plus Adhesion Microscope Slides (Epredia J7800AMNZ). For generating DNA arrays composed by 2,048 different probes (177 μm pitch distance; ∼100 μm printed spot), 32 BCr oligonucleotides presenting a unique molecular barcode were printed per row, by depositing ∼250 pL (250 μm between contiguous spots) with a DNA pico-litter spotter (Scienion sciflexarrayer S3). Similarly, 32 different BCc oligonucleotides were printed per column, by spotting ∼250 pL of each of them on top of the previoulsy prinded BCr oligonucleotides. Then, the same 32 BCr oligonucleotides were printed per row with a shifted position of 125 μm in both axis (i.e., interstitial printing), followed by the deposition of other 32 different BCc oligonucleotides printed per column. Hence, we needed in total 32 unique BCr (printed twice) and 64 unique BCc oligonucleotides.

Finally, fiducial borders were printed per DNA array, by adding three row/columns of spots with the used pitch distance (250 μm) by printing a BCr1 oligonucleotide presenting a Cy3-label at the 3′-extremity.

UV irradiation (254 nm; 5 min) has been applied for crosslinking, followed by T4 DNA polymerase elongation (15 μL/printed region with coverslips: 0.03 U/μL T4 DNA Polymerase (New England Biolads M0203L); 0.2 mM dNTPs (Thermo Fisher Scientific R0141/R0151/R0161/R0171); 37°C; 1h). To monitor the double-strand DNA elongation performance, a quality control assay is systematically done within a batch production (18 slides per batch; 3 printed regions per glass slide (8 × 8 mm size; 250 μm pitch distance)) by incorporating a dCTP-Cy3 nucleotide during the elongation (dATP/GTP/TTP at 52 μM, dCTP at 50 μM and dCTP-Cy3 at 20 μM (Cytivia PA53021)), and analyzed by fluorescent microscopy. After elongation, slides have been washed with 0.1X SSC buffer (Sigma S6639), and ddH2O, and finally spin dried (Labnet slide spinner C1303-T-230V, 4800 rpm). DNA array slides have been stored at +4°C in a sealed container.

Organoids tissue cryosectioning and in situ reverse transcription

Tissue samples were cryosectionned (20 μm sections collected at −20°C) and deposited on the DNA-arrays defined regions. During this process, slides were kept inside the cryostat chamber in order to conserve the integrity of the RNA and at −80°C for long storage.

Tissue sections were fixed with 4% Para-formaldheyde (PFA) (Life technologies 28908) in 1X PBS (Life technologies 70011–036) at room temperature during 10 min, then washed twice with 1X PBS, followed by a wash with double-distilled water (ddH2O).

Tissues deposited on DNA arrays were covered with ddH2O and heat at 65°C during 5 min, followed by a fast chilling procedure (−20°C; 2 min). Remaining water was replaced by hybridization mix (1 U/μL RNAse Inhibitor(New England Biolads M0314) in 6X SSC), and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. DNA arrays were washed by dipping them into a 50 mL falcon of 0.1X SSC then into a 50 mL falcon of ddH2O. Finally, tissue sections were air dried during 10 min.

To avoid evaporation, reverse transcription (RT) is performed within sealed chambers (Thermoscientific small size AB-0576). DNA arrays presenting tissue sections were incubated with RT mix (10 U/μL of SuperScript IV (Life Technologies 18090200), 1X SSIV buffer (Life Technologies 18090200), 5 mM DTT (Life Technologies 18090200), 20 μg/mL actinomycin D (Sigma A1410-2MG), 0.2 mg/mL Bovine Serum Albumine (BSA) (Sigma Merk A9418-10G), a mix of dATP/dTTP/dGTP (130 μM each), 125 μM of dCTP and 50 μM dCTP-Cy3, 1 U/μL of RNAse Inhibitors) at 42°C overnight with a heated lid at 70°C. Next day, slides were washed by dipping them into a 50 mL falcon of 0.1X SSC, then into a 50 mL falcon of ddH2O and spin-dried. Finally, DNA arrays were scanned with the TRICT filter to reveal the presence of the fiducial borders as well as the physical position of tissue sections on top of the printed DNA arrays, revealed by the newly synthesized cDNA.

After imaging, tissue sections were digested during 1 h at 37°C and at 300rpm (2.5 mg/mL proteinase K (Invitrogen 4333793) in PKD buffer (Quiagen 1034963)). Slides were washed in containers under agitation (400 rpm) as following: 100 mL of preheated buffer 1 (2X SSC and 0.1X SDS (Sigma 71736); 50°C) during 10 min, 5 min with buffer 2 (0.2X SSC; room temperature), 5 minutres with buffer 3 (0.1X SSC; room temperature). Finally slides were washed by dipping them in a 50 mL falcon containing ddH2O and spin-dried. DNA arrays were inspected at this stage to make sure that tissues was completely removed. DNA arrays were incubated with a freshly prepared 0.1 N NaOH solution during 10 min at room temperature, washed with the same solution, then neutralized for 2 min (for 100μL of 0.1 N NaOH, add 11.8 μL of 10X TE and, 6.5 μL of 1.25 M acetic acid). Finally, slides were washed by dipping them into a 50 mL falcon of 0.1X SSC, then into a 50 mL falcon of ddH2O and spin-dried.

cDNA’s complementary strand synthesis

DNA arrays were incubated with a poly-C tailing mix (0.6 U/μL TDT (New England Biolads M0315), 1X terminal transferase buffer (New England Biolads BO315), 0.3X CoCl2 (New England Biolads B0252), 0.2 mM dCTP) during 35 min at 37°C, then 20 min at 70°C to deactivate the enzyme and cooled at 12°C. Under these conditions, the length of the poly-C tail should be of ∼20 nts in average.4 Then, slides were washed in a 50 mL falcon containing 0.1X SSC, then in a falcon containing ddH2O prior to be spin-dried.

To generate a complementary DNA strand, DNA arrays were incubated with a 2nd strand synthesis mix (0.1 U/μL klenow exo- (New England Biolads M0212), 0.2 mg/mL BSA, 1X NEB2 buffer (New England Biolads B7002), 0.5 mM dNTPs) in presence of an oligonucleotide presenting a complementary sequence for the poly-C tailed sequence, as well as a 5′-extremity providing an adapter sequence (1μM final concentration “GTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTGGGGGGGGGH”). Second strand synthesis was performed within sealed chambers at 47°C during 5 min (primer anhealing), 37°C during 1 h (extension), 10 min at 70°C (enzyme deactivation) and cooled at 12°C. Slides were washed in a 50 mL falcon containing 0.1X SSC and a second falcon containing ddH2O.

Newly synthesized complementary DNA strands were recovered by incubating DNA arrays with 100 μL of 0.1N NaOH solution. After 10 min of incubation, NaOH solution has been collected in a 1.5 mL eppendorf, DNA arrays were washed with other 100 μL of 0.1N NaOH solution and collected within the same eppendorf. The 200 μL collected NaOH solution has been neutralized with 23.6 μL of 10X TE and 13 μL of 1.25 M acetic acid. DNA arrays were neutralized with 100μL 0.1N NaOH solution mixed with 11.8μL 10X TE and 6.5μL 1.25M acetic acid, then washed with 0.1X SCC and ddH2O for potential reuse if required.

Collected solution has been ethanol precipitated (2X EtOH volume, 200 mM NaCl, 1μL of 35 mg/mL glycogen (MP Glyco001); 1 h at −20°C; centrifuged at 12000 rpm, washed with 70% EtOH) and resuspended in 23 μL of ddH2O for 15 min at room temperature.

cDNA capture validation by quantitative PCR and illumina sequencing library preparation

The 23 μL of cDNA’s complementary-probe strand solution in ddH2O has been mixed with 25 μL of Q5 hot start high fidelity 2X master mix (M0464L), 1 μL adapter seq1 primer (GTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT; 0.2 μM final conc.) and 1 μL adapter seq2 primer containing a part of the T7-promoter sequence (TACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTGACTCGTAATAC GACTCACTATAGGG; 0.2 μM final concentration).

This mix has been PCR amplifyied (98°C, 30 s; 15 cycles: 98°C 10 s; 65°C 75 s; then 65°C 5 min; 12°C hold), cleanned at 0.9X ratio with SPRIselect beads (Beckman Coulter B23318) and resuspended in 24μL of ddH2O.

A second round of PCR amplification has been performed by mixing the 24 μL of adaptors linked cDNA’s complementary-probe strand with 25 μL 2X Q5 high fidelity ot start master mix, 0.5 μL of universal primer and 0.5 μL of index primer (0.1 μM final concentration; NEBNext multiplex oligos for Illumina index primers set 1 E7335). This mix has been amplified for 15 cycles (same amplification conditions as before), then cleanned at an 0.8X ratio with SPRISelect Beads (this ratio is used to get rid off fragments <200nt because the DNA-array probes added to the illumina sequencing adaptors and barcodes is 223 nt long without capturing any RNA). Final elution has been done in 25 μL of ddH2O.

5 μL of this library are used for quantitative PCR evaluation, targeting known transcript sequences (poly-A proximal regions), and the remaining 20 μL is used for Illumina sequencing (150 nts paired-ends sequencing; NovaSeq).

Bioinformatics processing

Primary analysis has been performed with our in-house developed tool SysISTD (SysFate Illumina Spatial transcriptomics Demultiplexer: https://github.com/SysFate/SysISTD).

SysISTD takes as entry paired-end sequenced reads (fastq or fastq.gz format), and two TSV files, the first one containing the sequence of the molecular barcodes associated to the rows or column in the printed arrays and the second file presenting the physical position architecture of the spatial barcodes. SysISTD searches for the Gibson sequence (regex query), then for two neighboring barcodes. Paired-reads presenting these features were aligned to the human genome (hg19) with Bowtie2, and known transcripts were annotated with featureCounts.17

As outcome, SysISTD generated a matrix presenting read counts associated to physical coordinates in the array in columns and known transcripts ID in rows. To focus the downstream analysis to the physical positions corresponding to the analyzed tissue, we used an in-house R script taking as entry an image of the DNA array scanned with the TRICT filter after the reverse transcription step. This image reveals the presence of the fiducial borders and the cDNA within the tissue. Specifically, we upload to R a croped image within the fiducials (imager package) and we use the “px.flood” function to retrieve the pixels associated to the tissue. Finally we applied a pixel to gexel coordinates conversion prior to cross this information with the outcome of SysISTD.

The “tissue-focused” matrix presenting read counts associated to spatial coordinates in columns, known transcripts in rows was processed with our previously described tool MULTILAYER.6,7 For human brain organoids processed in Figure 1, tissue partitioning has been performed with ≥4 contiguous gexels per pattern; Tanimoto Similarity threshold: 25%; while for the 3-dimensional tissue reconstruction in Figure 3, tissue partitioning has been performed with ≥3 contiguous gexels per pattern; Tanimoto Similarity threshold: 10%.

To compare contiguous sections, the “batch option” of MULTILAYER has been used, allowing to compute spatial classes in addition to spatial communities. Spatial classes, Spatial communities and tissue relationships were visualized within Cytoscape.

3-dimensional view of upregulated genes across sections were generated with an in-house R script (library “rgl”). Prior visualization, spatial gexels across sections were aligned relative to the center of the left human brain organoid (L-hBG) and the angle between the horizontal axis and a vector between the centers of the L-hBG and the R-hBG. Pseudo coordinates were computed by rotating tissues by the aforementioned angle and by centering the zero coordinate to the center of the L-hBG.

Cell/tissue type enrichment analysis has been performed with EnrichR18 with the ARCHS4,19 CellMarkerAugmented20 and Panglao21 databases. These databases are incorporated within MULTILAYER, allowing to perform the aforementioned enrichment analysis directly within this tool.

Immunostaining

Tissue sections were fixed by 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature, then washed 3 times in 1X PBS. Sections were permeabilized by 0.25% Triton (Sigma Merk 93443-100M) in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature, washed 3 times in 1X PBS and then blocked for 30 min at room temperature with blocking solution (1% BSA, 0.1% Triton in 1X PBS). After removing excess of blocking solution, tissue sections were first stained with primary mouse antibodies 1/250 diluted in blocking solution (GluR-1 (E−6) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies sc-13152) or mGluR-4 (B-8) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies sc-376485)) overnight at +4°C. The following day, tissue sections were washed 3 times for 5 min in 1X PBS, then stained with donkey secondary antibody targeting mouse primary antibodies DAM-555 (Sigma Merk SAB3701101-2MG) diluted at 1/1000 in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature. After 3 washes with 1X PBS (5 min each), tissue sections were stained with conjugated primary mouse antibody CASPR2 (H-10) Alexa Fluor 488 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies sc-398454 AF488) diluted at 1/250 in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature and then washed 3 times in 1X PBS for 5 min. Tissue sections were finally stained with DAPI solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific 62248) diluted at 1/5000 in 1X PBS, washed 3 times for 5 min in 1X PBS and mounted with glycerol (Sigma Aldrich G5516-100M) with cover slips. Whole immuno-stained human brain organoids and their corresponding nuclear staining (DAPI) were imaged with a manual scanning software (manualWSI Microvisioneer) under the same exposure time conditions per immuno-staining.

Data access

All raw datasets generated on this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE223020. Furthermore, processed spatial matrices as well as the corresponding scanned images are available herein: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ptv86nczbv.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Downstream data processing has been performed with MULTILAYER and MULTILAYER Compressor, available at https://github.com/SysFate/MULTILAYER; Zenodo; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8180632. A brief description concerning the use of MULTILAYER in the context of this study is available in Figure S3.

Spatially-resolved transcriptomics assay yields are detailed in Figure S2.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the team SysFate for contributing to the discussion of this project and the Genoscope sequencing platform for their technical support. This work was supported by the institutional bodies CEA, CNRS, and Université d’Evry-Val d’Essonne; the Genopole Thematic Incentive Actions funding (ATIGE-2017); and the “Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale” (FRM; funding ALZ-201912009904), as well as the Institut National Du Cancer (INCa: Funding 2020-181).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.M.-P.; formal analysis, G.L., F.S., J.M., and M.A.M.-P.; investigation, G.L.; methodology, G.L., A.B., A.A., and L.M.; resources, A.B., A.A., and L.M.; data curation, F.S. and J.M.; software, F.S. and J.M.; writing – original draft, M.A.M.-P.; writing – review & editing, F.Y. and J.-P.D.; supervision, J.-P.D. and M.A.M.-P.; funding acquisition, J.-P.D. and M.A.M.-P.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: September 1, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2023.100573.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

All raw datasets generated in this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE223020. Furthermore, processed spatial matrices as well as the corresponding scanned images are available herein: Mendeley Data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ptv86nczbv.

-

•

Primary analysis has been performed with our in-house developed tool SysISTD (SysFate Illumina Spatial transcriptomics Demultiplexer: https://github.com/SysFate/SysISTD; Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8180576).

-

•

Any additional information required to reproduce this work is available from the lead contact.

References

- 1.Rao A., Barkley D., França G.S., Yanai I. Exploring tissue architecture using spatial transcriptomics. Nature. 2021;596:211–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03634-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ståhl P.L., Salmén F., Vickovic S., Lundmark A., Navarro J.F., Magnusson J., Giacomello S., Asp M., Westholm J.O., Huss M., et al. Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science. 2016;353:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlecht U., Mok J., Dallett C., Berka J. ConcatSeq: A method for increasing throughput of single molecule sequencing by concatenating short DNA fragments. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5252. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05503-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu P., Jingyi W., Reinhard B., Sun-Yee K., Qiongyi Z., Chunming D., Weiping H., Wei X., Feng X. TELP, a sensitive and versatile library construction method for next-generation sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku818. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25223787/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankaranarayanan P., Mendoza-Parra M.-A., Walia M., Wang L., Li N., Trindade L.M., Gronemeyer H. Single-tube linear DNA amplification (LinDA) for robust ChIP-seq. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:565–567. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moehlin J., Mollet B., Colombo B.M., Mendoza-Parra M.A. Inferring biologically relevant molecular tissue substructures by agglomerative clustering of digitized spatial transcriptomes with multilayer. cels. 2021;12:694–705.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2021.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moehlin J., Koshy A., Stüder F., Mendoza-Parra M.A. Protocol for using MULTILAYER to reveal molecular tissue substructures from digitized spatial transcriptomes. STAR Protoc. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park Y.H., Pyun J.-M., Hodges A., Jang J.-W., Bice P.J., Kim S., Saykin A.J., Nho K., AddNeuroMed consortium and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Dysregulated expression levels of APH1B in peripheral blood are associated with brain atrophy and amyloid-β deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2021;13:183. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00919-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adnan G., Rubikaite A., Khan M., Reber M., Suetterlin P., Hindges R., Drescher U. The GTPase Arl8B Plays a Principle Role in the Positioning of Interstitial Axon Branches by Spatially Controlling Autophagosome and Lysosome Location. J. Neurosci. 2020;40:8103–8118. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1759-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St George-Hyslop F., Kivisild T., Livesey F.J. The role of contactin-associated protein-like 2 in neurodevelopmental disease and human cerebral cortex evolution. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022;15 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.1017144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortiz C., Navarro J.F., Jurek A., Märtin A., Lundeberg J., Meletis K. Molecular atlas of the adult mouse brain. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eabb3446. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vickovic S., Schapiro D., Carlberg K., Lötstedt B., Larsson L., Hildebrandt F., Korotkova M., Hensvold A.H., Catrina A.I., Sorger P.K., et al. Three-dimensional spatial transcriptomics uncovers cell type localizations in the human rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Commun. Biol. 2022;5:129–211. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03050-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Yang M., Deng Y., Su G., Enninful A., Guo C.C., Tebaldi T., Zhang D., Kim D., Bai Z., et al. High-Spatial-Resolution Multi-Omics Sequencing via Deterministic Barcoding in Tissue. Cell. 2020;183:1665–1681.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen A., Liao S., Cheng M., Ma K., Wu L., Lai Y., Qiu X., Yang J., Xu J., Hao S., et al. Spatiotemporal transcriptomic atlas of mouse organogenesis using DNA nanoball-patterned arrays. Cell. 2022;185:1777–1792.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia C., Fan J., Emanuel G., Hao J., Zhuang X. Spatial transcriptome profiling by MERFISH reveals subcellular RNA compartmentalization and cell cycle-dependent gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:19490–19499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1912459116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavoni S., Jarray R., Nassor F., Guyot A.-C., Cottin S., Rontard J., Mikol J., Mabondzo A., Deslys J.-P., Yates F. Small-molecule induction of Aβ-42 peptide production in human cerebral organoids to model Alzheimer’s disease associated phenotypes. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao Y., Smyth G.K., Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen E.Y., Tan C.M., Kou Y., Duan Q., Wang Z., Meirelles G.V., Clark N.R., Ma’ayan A. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinf. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachmann A., Torre D., Keenan A.B., Jagodnik K.M., Lee H.J., Wang L., Silverstein M.C., Ma’ayan A. Massive mining of publicly available RNA-seq data from human and mouse. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1366. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03751-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X., Lan Y., Xu J., Quan F., Zhao E., Deng C., Luo T., Xu L., Liao G., Yan M., et al. CellMarker: a manually curated resource of cell markers in human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D721–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franzén O., Gan L.-M., Björkegren J.L.M. PanglaoDB: a web server for exploration of mouse and human single-cell RNA sequencing data. Database. 2019;2019:baz046. doi: 10.1093/database/baz046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All raw datasets generated in this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE223020. Furthermore, processed spatial matrices as well as the corresponding scanned images are available herein: Mendeley Data: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ptv86nczbv.

-

•

Primary analysis has been performed with our in-house developed tool SysISTD (SysFate Illumina Spatial transcriptomics Demultiplexer: https://github.com/SysFate/SysISTD; Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8180576).

-

•

Any additional information required to reproduce this work is available from the lead contact.