Abstract

Copyrolysis is a potential method for the collaborative disposal of biomass and plastics. There is an interaction between biomass and plastics during copyrolysis. In this work, a combination of ReaxFF-MD simulation and experimental validation was used to investigate the pyrolysis reaction process of the biomass and plastic, observing the evolution of free radicals at the molecular level and exploring the distribution of pyrolysis products. TG-MS results show that reaction temperature ranges for cellulose and PVC are 296–400 and 267–480 °C, respectively. HCl is the main product of PVC pyrolysis, and mixing with cellulose will reduce the yield of HCl. The ReaxFF method was used to model the pyrolysis of cellulose and PVC. The modeling temperature is much higher than the real reaction temperature, which is attributed to the time scale of picoseconds of ReaxFF-MD modeling. Modeling results show that the yield of HCl of the cellulose/PVC mixture is obviously lower than that of pure PVC. When mixed with cellulose, the HCl release is largely inhibited and more chlorine elements are retained in the pyrolysis hydrocarbon fraction or solid products.

1. Introduction

Pyrolysis is an important way to recycle solid fuels or waste. Pyrolysis utilizes high-temperature conditions to breakdown large molecular chains in a directed manner, generating high value-added products such as fuel gas, pyrolysis oil, and semicoke, which can be utilized in various ways.1 Gas products can be used as fuels or chemical raw materials. Pyrolysis oil can be further refined into transportation fuel or chemical raw materials, and semicoke can be used to prepare catalyst carriers, activated carbon, and soil improvers.2

Plastic is a typical organic solid waste, and the pyrolysis mechanisms of different plastics are similar. When heated to a certain temperature, the system’s energy reaches the bond energy of each atomic link, causing chemical bonds to breakdown into small molecular fragments. The reaction process can be divided into thermal initiation, polymer chain cleavage, and chain termination. The thermal initiation process generates a large number of free radicals and free electrons at high temperatures, leading to irregular cleavage, while chain termination is the process in which free radicals undergo disproportionation reactions to generate compounds.3

The pyrolysis mechanism of chlorinated plastics, such as polyvinyl chloride, involves the removal of hydrogen chloride at high temperatures, leading to the formation of conjugated olefins containing carbon–carbon double bonds.4 The bond energy of Cl near the carbon–carbon double bond is relatively low, making it easy to break under heating and release as hydrogen chloride. With the release of a large amount of hydrogen chloride, the conjugated olefin reaches a critical length and terminates. Due to the high content of chlorine in polyvinyl chloride, the recycling efficiency of solid waste is greatly reduced, increasing the difficulty of waste disposal, and the pyrolysis recovery process is constrained to some extent. The main reason is that the HCl removed from polyvinyl chloride is an acidic gas with strong corrosiveness, and it can also generate dioxins, so it is particularly important to dispose hydrogen chloride properly.5,6

There is an interaction between the biomass and plastics during copyrolysis.7 When they are copyrolyzed, biomass generates a large amount of free radicals, triggering polymer chain scission reactions, while plastics contain a high content of hydrogen elements that can act as a hydrogen source to provide hydrogen for biomass pyrolysis, promoting biomass decomposition. Experimental studies have found that HCl released during PVC pyrolysis can undergo catalytic acidolysis with cellulose, promoting the dehydration reaction of cellulose, while the hydroxyl groups in cellulose can promote the removal of HCl.8

The interaction between the biomass and plastics during copyrolysis has been reported in the literature. Sophonrat et al.9 studied the interaction between cellulose and various plastics and found that copyrolysis of PE/PP/PS/cellulose promoted the generation of single-ring aromatic hydrocarbons. Sajdak et al.10 investigated the copyrolysis characteristics of two types of biomass with polypropylene and found that different types of biomass exhibited different pyrolysis behaviors, mainly influenced by the content of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in the material.

However, there is still lack of a detailed mechanism for the interaction during the copyrolysis of biomass and plastics at the molecular level.

With the development of computer technology, molecular simulation has become an increasingly important approach for studying chemical reactions. Reactive force field molecular dynamics (ReaxFF-MD) is a molecular simulation method that combines the ReaxFF reactive force field with molecular dynamics methods and can be used to simulate chemical reactions in complex systems.11,12 In recent years, the ReaxFF method has been widely used to study the pyrolysis reactions of polymers.

He et al.13 used the ReaxFF-MD method combined with the Auto RMA tool for reaction mechanism analysis to investigate the reaction mechanism of copyrolysis of typical polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS) waste plastics. Wang et al.14 used the ReaxFF-MD method studied the copyrolysis mechanism of cellulose and polyethylene. They considered the pyrolysis products during copyrolysis and found hydrocarbon and H radicals from polyethylene, interacting with the alcoholic groups and furans, which contributed to producing alcohols and suppressed the formation of aldehydes and ketones. Castro-Marcano et al.15 used the ReaxFF-MD method to study the reaction mechanism of coal pyrolysis and combustion. Zheng et al.16 studied the pyrolysis mechanism using a long-chain cellulose model through ReaxFF-MD and VARxMD visualization analysis, and the simulated evolution of products was consistent with the Py-GC/MS observation results. In summary, various studies have demonstrated that the ReaxFF-MD method can effectively reveal the chemical reaction mechanism of large molecule oxidation or pyrolysis. However, until now, there is a lack of molecular dynamics mechanism studies related to copyrolysis of PVC and biomass, especially the synergistic effect during copyrolysis.

This paper employs a combination of ReaxFF-MD simulation and experimental validation to investigate the pyrolysis reaction process of biomass and plastics, observing the evolution of free radicals at the molecular level and exploring the distribution of pyrolysis products. Furthermore, the paper reveals the reaction mechanism of the copyrolysis of plastics and biomass, which provides a theoretical basis for the coordinated disposal of biomass and plastic waste.

2. Experimental and Modeling Methods

2.1. Experimental Methods

The pyrolysis experiments were performed on a coupled instrument consisting of an STA 409PC (NETZSCH, Germany) simultaneous thermal analyzer and an Aeolos QMS403C (NETZSCH, Germany) quadrupole mass spectrometer. The system can perform simultaneous thermal gravimetric analysis (TG) and product fragment analysis (MS).

The maximum temperature in the reactor can reach 1500 °C, with a maximum heating rate of 50 °C/min, temperature accuracy of < ± 1 °C, and enthalpy accuracy of ±3%. The gaseous products generated during the sample pyrolysis process can be swept from bottom to top into the mass spectrometer for online analysis by the carrier gas. In order to prevent low-boiling point substances from condensing between the connecting pipes, a stainless-steel capillary is used to connect the mass spectrometer and thermal analyzer, and it is heated and maintained at a constant temperature of 350 °C.

For the experiments, aluminum oxide crucibles were used. Before each experiment, the crucibles were calcined in a muffle furnace at 1000 °C for 1 h to avoid the influence of other impurities in the crucibles on the experimental results. Each experiment used a balance to weigh 4–6 mg of the sample, which was then placed in the sample crucible. Prior to the experiment, the reaction chamber was evacuated to −0.5 MPa using a vacuum pump, followed by the introduction of argon gas to 0 MPa. Then, pure argon was introduced as the carrier gas with a total flow rate of 50 mL/min. After the balance reading stabilized, the heating program was started, and the temperature was increased to 800 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min, at which point data collection was stopped. The heating was then stopped, and argon gas was continuously introduced to cool the system to room temperature.

TG-MS coupling technology allows for the simultaneous analysis of small-molecule gas products generated during pyrolysis. Gas molecules are ionized in the ion source, generating positively charged ions with different mass-to-charge ratios (m/e). After being accelerated by a high-voltage electric field, they are deflected in a magnetic field and then reach the collector, producing a signal whose intensity is proportional to the number of ions. The obtained spectrum, with signal intensity as the y-axis and mass-to-charge ratio (m/e) as the x-axis, is the mass spectrum. By analysis of the mass spectrum, the relative concentration of gas products over time can be obtained. In this work, HCl, with m/e equaling 36.5, was detected and recorded.

2.2. Modeling Methods

Lignocellulosic biomass consists of three main components including cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. In this work, cellulose, which is a typical structure of the three components, was used to represent lignocellulosic biomass. The pyrolysis of cellulose and PVC was modeled using ReaxFF-MD. The simulation accounted for various energy contributions, including bond energy, lone pairs, valence geometry, over/undercoordination, torsion, and bond conjugation. To describe nonbonding interactions and coordination changes related to the chemical reactions, shielded van der Waals and Coulomb potentials were employed along with dynamic charge equilibration via the electronegativity equilibration method (EEM). ReaxFF produced results consistent with quantum–mechanical calculations and experiments for multiple hydrocarbon reactions but with significantly less computational load. As a result, it has the potential to simulate large reactive systems.

The LAMMPS package with the ReaxFF module was utilized to conduct a simulation.17,18 LAMMPS stands for large atomic/molecular massively parallel simulators, which is an open-source package for molecular dynamics simulations developed by Sandia National Laboratories. LAMMPS supports a wide range of particle types for the simulation of atoms, polymer molecules, biomolecules, metals, particles, and other types of systems. Cellulose systems comprising 10 glucose monomers were built using a cellulose builder, each of which consists of 10 β-phase cellulose chains.

The ReaxFF-MD simulations were initiated by performing 20 ps energy minimization of the system at 50 K. Subsequently, the system was equilibrated under a constant atom number, volume, and temperature (NVT) ensemble at 300 K. To achieve the desired density of cellulose and PVC, the macromolecule density was adjusted at 300 K and 10 MPa using the constant atom number, pressure, and temperature (NPT) ensemble. The system was then relaxed via a no-reaction NVT-MD simulation at 300 K. Finally, a series of nonisothermal simulations were conducted using the NVT ensemble at heating rates of 10 K/ps within the temperature range of 500–3000 K. To solve Newton’s equation of motion, the Verlet approach was employed with a time step of 0.25 fs. A Berendsen thermostat was utilized to regulate the temperature by using a damping constant of 100 fs. The bond-order cutoff of 0.3 was used to identify the product fragments. The C/H/O/S/F/Cl/N reactive force field19,20 which has been proved to be accurate in describing thermal reactions of hydrocarbon materials was adopted in this study.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results

Cellulose (Beijing Bielingwei Technology Co., Ltd.) and poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.) were selected as the raw materials for this experiment. The industrial analysis and elemental analysis results are shown in Table 1. PVC and cellulose were mixed and ground to below 150 mesh as the reaction raw materials. The raw materials were stored in a vacuum box at a temperature of 60 °C.

Table 1. Proximate and Ultimate Analysis of PVC and Cellulose.

| proximate analysis/wt % |

ultimate analysis/wt % |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | moisture | volatiles | fixed carbon | ash | C | H | Oa | N | S | Cl |

| PVC | 0.35 | 99.26 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 38.68 | 5.05 | 0.02 | 55.79 | ||

| cellulose | 0.28 | 93.76 | 5.86 | 0.1 | 42.58 | 6.08 | 50.96 | |||

Calculated by difference.

The pyrolysis of cellulose, PVC, and the mixture was conducted and the TG curves are summarized in Figure 1 as follows.

Figure 1.

TG curves of cellulose, PVC, and the mixture.

The weight loss curve of cellulose is flat within the temperature range of 100–285 °C, without any obvious weight loss phenomenon, indicating that cellulose does not generate a large amount of volatile components through pyrolysis at relatively low temperatures. According to publications,16,21,22 at lower temperatures, cellulose mainly undergoes external water precipitation and preliminary depolymerization of macromolecular chains, generating initial pyrolysis products such as active cellulose. With a further temperature increase, the thermal weight loss curve of cellulose rapidly decreases, indicating that cellulose undergoes fast pyrolysis and releases a large amount of volatile components, and this reaction temperature range is between 296 and 400 °C, which is the main temperature range for cellulose pyrolysis. With a further temperature increase, the thermal weight loss curve slowly decreases, and a small amount of volatile components is still emitted until the complete pyrolysis of cellulose at 700–800 °C, after which the thermal weight loss curve no longer changes. The char mass yield of cellulose at 800 °C is about 11.32 wt %.

As for PVC, there are two stages during PVC pyrolysis based on the TG curves, namely, the thermal dehydrochlorination stage and the breakdown of the intermediate products produced during the dehydrochlorination stage.23 The initial reaction temperature is about 267 °C, the temperature range of the first stage of PVC thermal decomposition is 267–320 °C, and there is 50.7% loss of mass during this stage. According to some publications,4 this stage belongs to the thermal dehydrochlorination of PVC. The second stage covers a temperature range of 320–480 °C, which is attributed to the breakdown of the intermediate products produced after the dehydrochlorination stage. The char mass yield of PVC at 800 °C is about 8.25 wt %.

With respect to the mixture of PVC and cellulose, the initial decomposition temperature is lower, which indicated that the HCl released from PVC may act as an acid catalyst to promote the dehydration and decomposition of cellulose and glucose monomers, thereby enhancing the synergistic effect of copyrolysis. The char yield of the mixture is about 14.27 wt %, which is larger than the individual char yield. The mass loss rate of the mixed material during pyrolysis is lower than that of pure cellulose or PVC, indicating that as the residual char content increases, low-temperature dehydration can reduce the hydrogen and oxygen atoms in cellulose. This process reduces the possibility of cellulose depolymerization, while the lack of hydrogen atoms and ring cleavage will result in a higher coke yield.

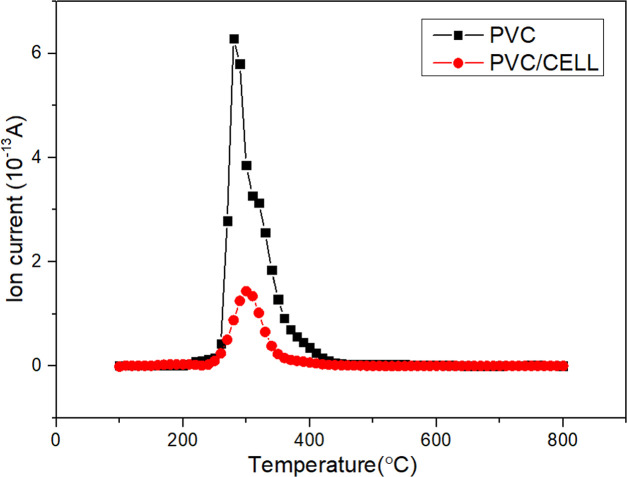

Furthermore, the generation properties of HCl were analyzed by online mass spectrometry, and the concentration curve of the HCl ion is shown in the figure below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Release tendency of ionized fragments with m/z = 36.5 during pyrolysis of PVC and the mixture.

It can be seen that the HCl release peak of pure PVC is 280 °C, which is located at the temperature range of the first stage as discussed above. HCl is released until 450 °C. When mixed with cellulose, the HCl release is largely inhibited. One possible reason is that HCl released from PVC reacts with small-molecular compounds generated during cellulose pyrolysis, leading to the consumption of HCl. Jia-gui et al.24 suggest that it may be due to the reaction of small-molecule products generated from cellulose pyrolysis with HCl, leading to the consumption of HCl. Kuramochi et al.25 studied HCl emission during the copyrolysis of demolition wood and a small amount of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) film. They found that HCl emission was reduced by the presence of wood and revealed that hemicellulose significantly reduced HCl emission by fixing most of the Cl molecules in a sample into a pyrolyzed residue.

3.2. Modeling Results

3.2.1. Molecular Model Construction and Optimization

To analyze the pyrolysis and product yield trends of cellulose, PVC, and the mixture, the molecular models of three polymers were constructed initially. The amorphous cell module in the Material Studio platform was used to construct the molecular clusters. The construction function in the amorphous cell was used to build the initial system with a density of 0.1 g/cm3. The Forcite module was used to optimize the system binding to prevent errors in the subsequent molecular dynamics simulation due to unreasonable binding configurations (such as overcrowded contacts).

Then, the NPT ensemble was used to compress and decompress the model under pressures of 0.01 GPa and 0.1 MPa, respectively. To achieve the desired density of cellulose and PVC, the macromolecule density was adjusted to 1.21 and 1.18 g/cm3 at 300 K and 10 MPa using the constant atom number, pressure, and temperature (NPT) ensemble. The optimized density values were comparable with actual values (1.5 and 1.38 g/cm3 for cellulose and PVC, respectively). The density optimization results are shown in Figure 3 as follows.

Figure 3.

Variation of molecular cell density with optimization time (NPT ensemble, 0.01 GPa).

After annealing and dynamic simulation, a series of structural configurations of the model are obtained, from which the configuration with the lowest energy will be selected. The configurations of the model clusters are shown in Figure 4 as follows.

Figure 4.

Optimized model clusters and single molecular chains.

3.2.2. Product Yields during Pyrolysis of Cellulose and PVC

Next, the product yields during the pyrolysis of individual cellulose and PVC are analyzed. According to experimental results in publications,26−28 the pyrolysis products of cellulose mainly include solid char, bio-oil, and gases. Among them, bio-oil is a complex mixture, mainly composed of acids, phenols, aldehydes, ketones, and aromatic hydrocarbons; gases are mainly composed of CO, CO2, CH4, H2, and other hydrocarbons. The evolution of the molecular configurations of PVC and cellulose with temperature is summarized in Figure 5 as follows.

Figure 5.

Evolution of molecular configurations during the pyrolysis of PVC and cellulose.

First, the solid conversion rates for three models were studied. During the heating process, the decomposition of cellulose, PVC, and the mixture will take place. In the molecular systems, there are quite a lot of molecule species. In this work, species with a molecular weight higher than 500 or a number of carbon atoms higher than 20 are regarded as char compounds. By addition of the mass of solid components in each reaction step, the remaining solid mass at each temperature can be obtained, and the curve can be plotted as shown below (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Residual solid mass percentage (calculating TG curves).

The initial pyrolysis temperature of cellulose is around 1600 K, and the finishing temperature is about 2200 K. The initial thermal decomposition temperature of PVC is around 1500 K, and its thermal decomposition temperature range is between 1500 and 2600 K. The initial decomposition temperature of PVC is lower than that of cellulose, which is in agreement with the experimental results. It can also be observed that the temperature of thermal decomposition reactions in molecular simulations is significantly higher than that of the experimental results. ReaxFF-MD simulations typically operate on a time scale of picoseconds, which is significantly shorter than the time scale of experiments that operate on a scale of seconds. To compensate for this difference, ReaxFF-MD simulations require increased temperatures to accelerate reaction kinetics, resulting in chemical reactions occurring within an extremely short period of time.29,30 Several ReaxFF studies have shown that elevated temperatures in MD simulations can accurately replicate experimental observations at their respective temperatures.31,32 With respect to the PVC/cellulose mixture, the initial decomposition temperature is about 1600 K, which is a little lower than that of cellulose.

Although the simulation temperature is generally much higher than the experimental temperature, the overall thermal decomposition behavior of the three molecular models is similar to the experimental results.

Next, the individual compounds produced during pyrolysis of three models were analyzed, and the results are summarized in Figures 7, 8, and 9–9 as follows.

Figure 7.

Product distribution during cellulose pyrolysis from 500 to 3000 K.

Figure 8.

Product distribution during PVC pyrolysis from 500 to 3000 K.

Figure 9.

Product distribution during copyrolysis of cellulose and PVC from 500 to 3000 K.

As shown in Figure 7, eight kinds of pyrolysis products, including permanent gaseous species (H2, CO, CO2), water, and typical organic compounds (levoglucosan (C6H10O5), C2H4O2, formic acid(CH2O2), and formaldehyde (CH2O)), are recorded. It can be seen that the generation of water molecules has the lowest temperature requirement and starts at the initial stage of cellulose pyrolysis (1700 K) due to the dehydroxylation reaction of cellulose. As for permanent gaseous species (H2, CO, CO2), CO is released at around 1900 K, while CO2 and H2 are produced at a higher temperature (2200 K). The yield of permanent gases increases rapidly with an increase of temperature. This is consistent with the experimental results reported in the literature.16,28

With respect to the organic compounds, levoglucosan (C6H10O5) is a typical intermediate product during cellulose pyrolysis.33 It is produced at 1800 K and quickly reached the peak amount and then decreased at higher temperature. When the temperature is higher than 2700 K, no levoglucosan is recorded, which is attributed to the secondary reaction to produce smaller and stable species. C2H4O2 represents acetic acid or glycolic aldehyde, which is produced at 1600 K. The yield of C2H4O2 reached the maximum at a temperature of 2500 K and then decreased. Different from levoglucosan, C2H4O2 still exists in large quantities at 3000 K. Formic acid and formaldehyde are initially produced at 1800 and 1600 K, respectively. With increasing pyrolysis temperature, both yields of formic acid and formaldehyde increased.

With respect to PVC, HCl is the key product. As shown in Figure 8, HCl is initially released at around 1950 K and with increasing modeling temperature, the yield of HCl rapidly increased. A small amount of Cl is released at Cl2, while most of the Cl is released in the form of chloroethylene (C2H3Cl), which is the monomer of polyvinyl chloride. Chloroethylene is released at around 1600 K, which is earlier than HCl, which is attributed to the chain scission of PVC. The yield of chloroethylene increased rapidly with pyrolysis temperature, and when the temperature reaches 2700 K, the yield begins to decrease. At high temperatures, chlorinated hydrocarbons undergo secondary reactions to produce HCl. Acetylene (C2H2) is another major thermal decomposition product of PVC, with an initial release temperature of about 2400 K, higher than those of other products. With increasing pyrolysis temperature, the yield of acetylene rapidly increased.

Next, the copyrolysis of cellulose and PVC is studied. The yields of some key species are summarized in Figure 9 as follows.

It can be seen that the yield of HCl of the cellulose/PVC mixture is obviously lower than that of pure PVC. When mixed with cellulose, the HCl release is largely inhibited. This is consistent with the experimental results. Jia-gui et al.24 suggest that it may be due to the reaction of small-molecule products generated from cellulose pyrolysis with HCl, leading to the consumption of HCl. Experimental studies have found that HCl released during PVC pyrolysis can undergo catalytic acidolysis with cellulose, promoting the dehydration reaction of cellulose, while the hydroxyl groups in cellulose can promote the removal of HCl.8 The yield of CO is also much lower than that of pure cellulose pyrolysis. It means that copyrolysis will inhibit the inhibit decarbonylation reaction, thereby suppressing the formation of CO. The yields of organic compounds, such as CH2O and C2H4O2, are not influenced by copyrolysis with PVC.

3.3. Discussion

PVC is a major component of municipal solid waste, while biomass is the main component of rural solid waste. The current methods for treating biomass are mainly landfills and incineration. Landfill not only occupies land resources but also emits greenhouse gases such as methane, while incineration produces a large amount of toxic and harmful substances that can harm the health of living organisms. Furthermore, both methods do not efficiently recover energy from biomass. Therefore, in recent years, many researchers have conducted studies on the copyrolysis of PVC and biomass, maximizing the synergistic effect to recover the chemical and biomass energy from PVC and biomass, producing high value-added chemicals, and reducing environmental pollution.

Obviously, there is a significant synergistic effect between cellulose and PVC during their copyrolysis process, especially on the products. The synergistic effect was illustrated by the experimental and modeling method. First, it was found through thermogravimetric experimental studies that the initial decomposition temperature was lower, which indicated that the HCl released from PVC may act as an acid catalyst to promote the dehydration and decomposition of cellulose and glucose monomers, thereby enhancing the synergistic effect of copyrolysis. The char yield of the mixture is about 14.27 wt %, which is larger than the individual char yield. Second, the yield and releasing properties of HCl during pyrolysis and copyrolysis were analyzed by online mass spectrometry. When mixed with cellulose, the HCl release is largely inhibited. One possible reason is that the HCl released from PVC reacts with small molecular compounds generated during cellulose pyrolysis, leading to the consumption of HCl. The yield of CO is also much lower than that of pure cellulose pyrolysis. It means that copyrolysis will inhibit the inhibit decarbonylation reaction, thereby suppressing the formation of CO.

Some similar synergistic effect during copyrolysis of biomass and plastic has been studied by other researchers. Özsin et al.34 investigated the synergistic effect of copyrolysis of PVC and other plastics with walnut shells and peach kernels at 500 °C. It was found that compared with copyrolysis with other plastics, the addition of PVC was unfavorable for the formation of bio-oil, and the highest oil yield was only 17.6%. In addition, the hydrogen–carbon ratio of copyrolysis tar decreased and the recombination fraction increased. Some studies have also shown that copyrolysis of PVC and biomass is unfavorable for increasing the oil yield and improving the oil quality. This is likely due to the chlorine-containing nature of PVC itself, which catalyzes the dehydrogenation of biomass through HCl generated during the pyrolysis process. On the one hand, this is beneficial for the formation of heavy components, and on the other hand, it is conducive to their polymerization into char. Some researchers have utilized this characteristic to increase the yield of carbonization products and to modify carbon materials. Matsuzawa et al.7 studied the interaction between cellulose and PVC during copyrolysis. They found the char of a mixture of cellulose and PVC to have fewer hydroxyl groups and more C=O and C=C bonds compared with the char of pure cellulose. HCl evolution from the chlorinated polymer might thus possibly induce reactions of dehydration, scission in intraring of glucose unit, cross-linkage, and charring rather than the depolymerization of cellulose.

With a combination of experimental and modeling results, the schematic diagram for the interaction during copyrolysis of cellulose and PVC is summarized in Figure 10 as follows.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram for the interaction during copyrolysis of cellulose and PVC.

Based on the experimental and calculation results, the interaction between cellulose and PVC during copyrolysis was found and discussed. Thermogravimetric experiments showed that the initial decomposition temperature was lower, which indicated that the HCl released from PVC may act as an acid catalyst to promote the dehydration and decomposition of cellulose and glucose monomers, thereby enhancing the synergistic effect of copyrolysis. As pointed out in the above-mentioned section, the copyrolysis improved the yield of char. The char yield was 14.27 wt %, which is larger than the individual char yield. Both experimental and modeling results showed that the HCl yield was inhibited during copyrolysis with cellulose, which is attributed to the hydroxyl groups in cellulose, leading to the consumption of HCl. The yield of CO is also much lower than that of pure cellulose pyrolysis. It means that copyrolysis will inhibit the inhibit decarbonylation reaction, thereby suppressing the formation of CO.

4. Conclusions

Copyrolysis is a potential method for the collaborative disposal of biomass and plastics. There is an interaction between biomass and plastics during copyrolysis. In this work, a combination of ReaxFF-MD simulation and experimental validation was used to investigate the pyrolysis reaction process of cellulose and PVC, observing the evolution of free radicals at the molecular level and exploring the distribution of pyrolysis products. TG-MS results show that reaction temperature ranges for cellulose and PVC are 285–400 and 250–480 °C, respectively. HCl is the main product of PVC pyrolysis, and mixing with cellulose will reduce the yield of HCl. The ReaxFF method was used to model the pyrolysis of cellulose and PVC. The modeling temperature is much higher than the real reaction temperature, which is attributed to the time scale of picoseconds during ReaxFF-MD modeling. Modeling results show that the yield of HCl of the cellulose/PVC mixture is obviously lower than that of pure PVC. When mixed with cellulose, the HCl release is largely inhibited and more chlorine elements are retained in the pyrolysis hydrocarbon fraction or solid products. Meanwhile, copyrolysis will inhibit the inhibit decarbonylation reaction, thereby suppressing the formation of CO.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Chen D.; Yin L.; Wang H.; et al. Pyrolysis technologies for municipal solid waste: a review. Waste Manage. 2014, 34 (12), 2466–2486. 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andooz A.; Eqbalpour M.; Kowsari E.; et al. A comprehensive review on pyrolysis of E-waste and its sustainability. J. Cleaner Prod. 2022, 333, 130191 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi M. S.; Oasmaa A.; Pihkola H.; et al. Pyrolysis of plastic waste: Opportunities and challenges. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2020, 152, 104804 10.1016/j.jaap.2020.104804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.; Sun L.; Ma C.; et al. Thermal degradation of PVC: A review. Waste Manage. 2016, 48, 300–314. 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z.; Li J.; Gu T.; et al. Effects of torrefaction on the formation and distribution of dioxins during wood and PVC pyrolysis: An experimental and mechanistic study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 157, 105240 10.1016/j.jaap.2021.105240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buekens A.; Cen K. Waste incineration, PVC, and dioxins. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 2011, 13, 190–197. 10.1007/s10163-011-0018-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa Y.; Ayabe M.; Nishino J. Acceleration of cellulose co-pyrolysis with polymer. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2001, 71 (3), 435–444. 10.1016/S0141-3910(00)00195-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai S.; Yamamoto M.; Takahashi Y.; et al. Impact of common plastics on cellulose pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2019, 33 (7), 6837–6841. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b01376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sophonrat N.; Sandström L.; Johansson A. C.; et al. Co-pyrolysis of Mixed Plastics and Cellulose: An Interaction Study by Py-GC × GC/MS. Energy Fuels 2017, 31 (10), 11078–11090. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b01887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sajdak M. Impact of plastic blends on the product yield from co-pyrolysis of lignin-rich materials. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 124, 415–425. 10.1016/j.jaap.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senftle T. P.; Hong S.; Islam M. M.; et al. The ReaxFF reactive force-field: development, applications and future directions. npj Comput. Mater. 2016, 2 (1), 15011 10.1038/npjcompumats.2015.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Duin A. C. T.; Dasgupta S.; Lorant F.; et al. ReaxFF: A Reactive Force Field for Hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105 (41), 9396–9409. 10.1021/jp004368u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He X.-c.; Chen D.-z. ReaxFF MD study on the early stage co-pyrolysis of mixed PE/PP/PS plastic waste. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2022, 50 (3), 346–356. 10.1016/S1872-5813(21)60161-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Li Y.; Zhang C.; et al. A study on co-pyrolysis mechanisms of biomass and polyethylene via ReaxFF molecular dynamic simulation and density functional theory. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 150, 22–35. 10.1016/j.psep.2021.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Marcano F.; Kamat A. M.; Russo M. F.; et al. Combustion of an Illinois No. 6 coal char simulated using an atomistic char representation and the ReaxFF reactive force field. Combust. Flame 2012, 159 (3), 1272–1285. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2011.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M.; Wang Z.; Li X.; et al. Initial reaction mechanisms of cellulose pyrolysis revealed by ReaxFF molecular dynamics. Fuel 2016, 177, 130–141. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atomic L.-s.; M M. P.. Simulator. Lammps, http:/lammps.sandia.gov. 2013.

- Liu J.; Li X.; Guo L.; et al. Reaction analysis and visualization of ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2014, 53, 13–22. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood M. A.; Van A. C.; Duin; Strachan A. Coupled thermal and electromagnetic induced decomposition in the molecular explosive αHMX; a reactive molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118 (5), 885–895. 10.1021/jp406248m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong D.; Gao P.; Wang C. A comprehensive understanding of the synergistic effect during co-pyrolysis of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and coal. Energy 2022, 239, 122258 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lédé J. Cellulose pyrolysis kinetics: An historical review on the existence and role of intermediate active cellulose. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2012, 94, 17–32. 10.1016/j.jaap.2011.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan P. R.; Dalluge D. L.; Shanks B. H.; et al. Distinguishing primary and secondary reactions of cellulose pyrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102 (8), 5265–5269. 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-H.; Chang C. Y.; Hor J. L.; et al. Two-Stage pyrolysis model of PVC. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1994, 72 (4), 644–650. 10.1002/cjce.5450720414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia-gui Y.; et al. Co-pyrolysis and Cl Release Characteristics of PVC and Lignocellulose. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2023, 51, 939–948. 10.19906/j.cnki.JFCT.2023014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi H.; Nakajima D.; Goto S.; et al. HCl emission during co-pyrolysis of demolition wood with a small amount of PVC film and the effect of wood constituents on HCl emission reduction. Fuel 2008, 87 (13), 3155–3157. 10.1016/j.fuel.2008.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Dai G.; Yang H.; et al. Lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis mechanism: A state-of-the-art review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 62, 33–86. 10.1016/j.pecs.2017.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.; Dai Y.; Yang H.; et al. A Review of Recent Advances in Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2020, 34 (12), 15557–15578. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c03107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Yan R.; Chen H.; et al. Characteristics of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin pyrolysis. Fuel 2007, 86 (12), 1781–1788. 10.1016/j.fuel.2006.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- So/rensen M. R.; Voter A. F. Temperature-accelerated dynamics for simulation of infrequent events. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112 (21), 9599–9606. 10.1063/1.481576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paajanen A.; Vaari J. High-temperature decomposition of the cellulose molecule: a stochastic molecular dynamics study. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2713–2725. 10.1007/s10570-017-1325-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bal K. M.; Neyts E. C. Direct observation of realistic-temperature fuel combustion mechanisms in atomistic simulations. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (8), 5280–5286. 10.1039/C6SC00498A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X.-M.; Wang Q. D.; Li J. Q.; et al. ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations of oxidation of toluene at high temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116 (40), 9811–9818. 10.1021/jp304040q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduskar S.; Maliekkal V.; Neurock M.; et al. On the Yield of Levoglucosan from Cellulose Pyrolysis. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6 (5), 7017–7025. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Özsin G.; Pütün A. E. A comparative study on co-pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass with polyethylene terephthalate, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride: Synergistic effects and product characteristics. J. Cleaner Prod. 2018, 205, 1127–1138. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]