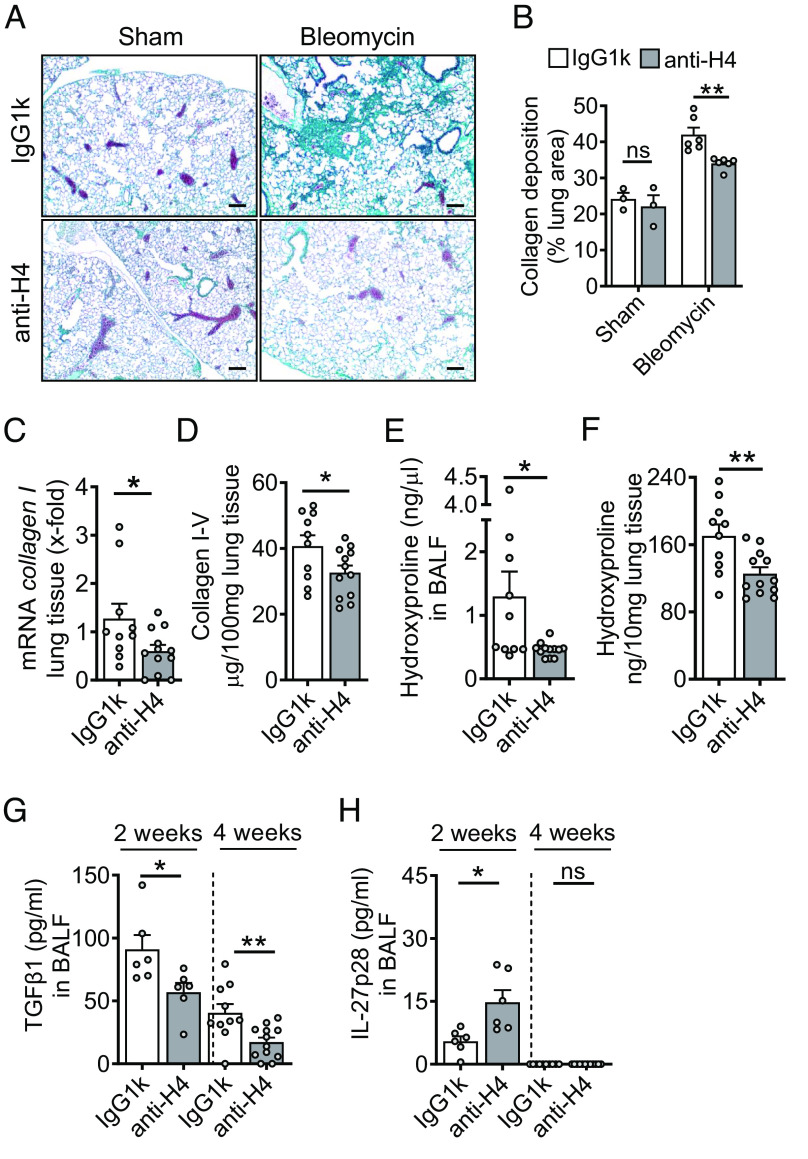

Fig. 2.

Externalized histones promote pulmonary fibrosis. (A) Histology of lungs from WT mice which received either monoclonal anti-H2A/H4 antibodies (clone: BWA3, 250 µg/mouse i.v.) or mouse IgG1κ isotype control antibodies simultaneously with i.t. bleomycin (n = 3–6/group). Masson–Goldner’s trichrome staining of lungs was performed after 4 wk (Scale bar, 50 μm). (B) Quantification of lung collagen deposition from scanned whole slides from mice in frame A. (C) ECM expression as evaluated by RT-PCR for collagen I (col1a2) mRNA in lung homogenates during bleomycin-induced fibrosis. (D) SIRCOL assay for collagen I–V in lung tissue of anti-histone antibody-treated mice or control IgG1k-treated mice after bleomycin i.t. (E and F) Hydroxyproline concentrations in BALF and lung tissue of anti-histone antibody-treated mice as compared to IgG1k controls during fibrosis, 4 wk. (G and H) TGFβ1 and IL-27p28 concentrations in BALF of anti-histone antibody-treated mice as compared to IgG1k controls at 2 wk or 4 wk after bleomycin, ELISA. Horizontal dashed lines indicate groups of samples which were analyzed on separate days and ELISA plates. Experiments in all frames were done with C57BL/6 J (WT) mice and analyzed 4 wk (frame A–F) or 2 wk (stated in frame G and H) after bleomycin i.t. (1 U/kg body weight). Numbers of mice in frames B–H are indicated by circles; Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns: not significant.