Abstract

Background:

Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB)1 plays a critical role in the management of patients with salivary gland lesions. A specific diagnosis can be difficult due to the wide range of lesions with overlapping morphologic features, potentially leading to interpretation errors. We analyzed the cytologic-histologic discrepancies identified in the quality assurance program of a major cancer center in cases of salivary gland FNAB and performed a root cause analysis.

Material and Methods:

Salivary gland FNAB specimens performed during 12 year period at a major tertiary cancer center were reviewed. The inclusion criteria for this study included FNAB cases of salivary glands with subsequent histologic or flow cytometry follow up. The cytologic diagnoses for these cases were re-categorized according to the Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology (MSRSGC)2 based on the original reports. The risk of neoplasm and malignancy (RON3 and ROM4, respectively) based on the cases with subsequent resection or flow cytometry and the most common causes of discrepancy were analyzed.

Results:

The RON ranged from 41 % to 99% and the ROM ranged from 22% to 99% among the different MSRSGC categories. Lymphoid and myoepithelial rich lesions were the most common miscategorized lesions using the MSRSGC. Reactive changes due to inflammation were associated with overcalls. The most common malignancy in the atypical category was mucoepidermoid carcinomas.

Conclusion:

Myoepithelial and lymphoid rich lesions arising in the salivary gland are associated with a higher risk of misclassification. The use of category IVB in the MSRSGC is appropriate for lesions with abundant myoepithelial cells. Reactive atypia seen in sialadenitis was the most common feature associated with overcall.

Keywords: Salivary gland, Cytology, quality assurance, risk of malignancy

INTRODUCTION

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC)5 of salivary gland is used worldwide for the diagnosis and management of salivary gland tumors. It is a minimally invasive, safe, cost-effective, and accurate test that is extremely useful in classifying a substantial subset of salivary gland nodules as benign, and thus reduces unnecessary invasive surgical procedures in patients with benign diseases. In addition, it helps to tailor management strategies.[1–4] The reported sensitivity and specificity of salivary gland FNAB to distinguish neoplastic vs. non-neoplastic lesions is high, ranging from 86% to 100%, with a specificity ranging from 90%–100%. [5–8]

Despite the high sensitivity of salivary gland FNAB to identify lesions requiring surgical resection, a specific diagnosis can be challenging due to the wide range of lesions that can have overlapping morphologic features, including lesions with oncocytic morphology [9–11] or lesions with basaloid features[10, 12–14]. Both benign and malignant lesions can share morphological similarities and the pathological diagnosis might depend on extensive histological evaluation after surgical resection. Although ancillary studies, such as immunohistochemical, cytogenetic, or molecular studies might be helpful in a subset of cases, the limited material available from salivary gland FNAB might hinder a full work- up and not all lesions demonstrate immunohistochemical or molecular findings that would enable a specific classification.

These limitations in salivary gland FNAB led the American Society of Cytopathology and the International Academy of Cytology to introduce an international classification scheme for reporting salivary gland FNA. The goal of this classification, the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology (MSRSGC), was to standardize the reporting system of salivary gland FNA and improve the communication among pathologists, surgeons, and clinicians managing salivary gland lesions. The classification was based on the experience of experts in the field of cytopathology and on evidence from the literature. It is a six tiered classification with the neoplastic category subdivided into benign and salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (Table 1) [15]

Table 1:

Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology categories

| I. | Non-diagnostic |

| II. | Non-neoplastic |

| III. | Atypical |

| IVa. | Neoplastic-Benign |

| IVb | Neoplastic – Salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential |

| IV. | Suspicious for malignancy |

| V. | Malignant |

Cytologic- histologic correlation (CHC)6 is a quality assurance process used to evaluate potential sources of misdiagnosis in Cytology with the intent to increase sensitivity and specificity. According to a national survey of 546 participating laboratories sponsored by the College of American Pathologists published in 2013, cytologic-histologic correlation was tied for first place among 15 quality metrics considered useful in a QA7 program, along with multiheaded case review of difficult cases and retrospective review of negative for intraepithelial lesion and malignancy (NILM)8 slides in current HSIL9 Pap test cases[16] This activity is required by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA)[17]10 for cervico-vaginal specimens to identify laboratory errors and many institutions extend this practice for non-gynecologic specimens. The analysis can be used to identify common reasons for discrepancies, from sampling errors to system-based errors. The current study reflects the findings of the CHC activity that is part of the Quality Assurance (QA) protocols implemented in Cytology Service at our institution. This protocol uses the departmental laboratory information system to search for all subsequent surgical specimens obtained within 3 months of a cytology diagnosis. The goal of this study is to analyze the results of this QA program for cases of salivary gland FNAB in the context of the MSRSGC in a large tertiary cancer center.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB)11 and the Department of Pathology database was queried for salivary gland FNA specimens diagnosed between 2008 and 2020 at a major tertiary cancer center. Only FNAB cases that have corresponding histologic or flow cytometry correlation were included in this study. All surgical diagnoses were matched manually to ensure that they correspond to the site in which the FNAB was obtained. The matched cases were evaluated for diagnosis concordance or discrepancy by 2 cytopathologists. The cytologic diagnoses for these cases were categorized according to the MSRSGC based on the original reports and/or review of cases.

The recategorization into different Milan categories and reviewing of all available cytologic material of discrepant cases (smears, Thinprep, and cell block preparations on glass slides or digital images) were carried out by 2 cytopathologists. Imaging correlation and evaluation of ancillary studies were conducted when available. The risk of neoplasm and malignancy (RON and ROM, respectively) were calculated for each MSRSGC category based on the histologic resection or flow cytometry diagnosis. The most common causes of discrepancy were analyzed. Discrepancies were defined as those in which the primary cytologic diagnosis could potentially result in unnecessary surgery or delay of treatment. The morphological findings of the discrepant cases were further analyzed in the context of the surgical diagnosis to identify potential causes of error, which could be due to sampling, misinterpretation of the morphological findings, or system-based deficiency such as lack of flow cytometry studies. Cases classified as atypical were not considered discrepant, but the reasons for a less definite diagnosis were evaluated.

In cases with multiple samples, only the diagnostic cases were used in the study (non-diagnostic cases were excluded). If a case underwent more than one FNAB and the samples were classified in different MSRSGC categories, all biopsies were included as independent cases. If a repeat biopsy was classified in the same MSRSGC category, only one FNAB diagnosis was included in the study.

RESULTS

The diagnoses from 2723 cases of salivary gland FNABs were reviewed. A total of 657 FNAB samples from 638 patients that met the above criteria were included in this study. Among the 638 patients, 620 patients had only one diagnostic sample, while 18 patients had repeat biopsies (17 patients had one repeat biopsy, and 1 patient had two repeat biopsies). Corresponding surgical specimens and/or flow cytometry studies were available for all 638 patients. The gender distribution was almost evenly distributed with a female to male ratio of 1.02. The predominant patient age ranged from 41–80 years. The most common site biopsied among the cases with a subsequent resection was parotid gland (575/657, 87.5%), followed by submandibular gland (73/657, 11.1%), and minor salivary glands (9/657, 1.4%). The FNAB diagnosis distribution according to the MSRSGC were the following: 21 (3.2%) were classified as non-diagnostic (MSRSGC category I) cases, 64 (9.7%) as non-neoplastic (MSRSGC category II), 62 (9.4%) as atypical (MSRSGC category III) cases, 106 (16.1%) as neoplastic benign (MSRSGC category IVa), 141 (21.5%) as salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential(MSRSGC category IVb), 41 (6.2%) as suspicious (MSRSGC category V) and 222 (33.8%) as malignant(MSRSGC category VI).

All 21 cases originally diagnosed as non-diagnostic (MSRSGC category I) presented with a mass lesion on ultrasound examination. The histological correlation in these 21 cases included non-neoplastic lesions (n=6), benign neoplasms (n=9) and malignant neoplasms (n=6). Six of the MSRSGC category I cases were shown to be inflammatory in nature. Among the benign neoplasms seen in this category, 5 of 9 cases were hemangiomas or lymphangiomas. On re-review, all cytology specimens did not contain diagnostic material. Therefore, the discrepancies were attributed to sampling errors. Nonetheless, the RON was 71% while the ROM was 29%. The surgical diagnoses of the neoplasms in this category are listed in Table 2.

Table 2:

Histologic follow up for cytology cases diagnosed as non-diagnostic (MSRSGC category) (n=21)

| Histologic diagnosis | Corresponding MSRSGC category |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Benign cysts (2) | Non-neoplastic (6) |

| Salivary gland tissue with chronic inflammation (4) | |

|

| |

| Hemangiomas and lymphangioma (5) | Neoplastic-benign (9) |

| Pleomorphic adenomas (3) | |

| Basal cell adenoma (1) | |

|

| |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (1) | Neoplastic-malignant (6) |

| Acinic cell carcinoma (1) | |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma(1) | |

| Spindle cell melanoma (1) | |

| Basal cell carcinoma (1) | |

| Carcinoma-Ex pleomorphic adenoma (myoepithelial carcinoma) (1) | |

Thirty eight of 64 specimens originally classified as non-neoplastic (MSRSGC category II) were confirmed as non-neoplastic based on the histological correlation (n=23) or flow cytometry studies (n=15), while 26 subsequent (surgical specimen) contained a neoplasm, either benign or malignant. (Table 3) On review of the 26 discrepant cases in this category, 22 cases contained no diagnostic material (sampling error) and 2 cases were subsequently diagnosed as low grade lymphoma. These 2 cases had no concurrent flow cytometry studies performed. The 2 remaining discrepant cases in this category were represented by cases of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, a particular difficult cytological diagnosis, which might have been best classified as atypical or suspicious. The RON and ROM in this category were 41% and 22%, respectively, however, if cases with sampling errors or lack of flow cytometry studies were excluded, the ROM would be 3%.

Table 3:

Histologic follow up for cytology cases diagnosed as non-neoplastic (MSRSGC category II) (n=64)

| Histologic diagnosis and flow cytometry results | Corresponding MSRSGC category |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Benign cysts (6) | Non-neoplastic (38) |

| Salivary gland tissue with chronic inflammation (14) | |

| Salivary gland tissue with granulomatous inflammation (1) | |

| Benign lymph nodes (17)* | |

|

| |

| Pleomorphic adenomas (5) | Neoplastic-benign (12) |

| Warthin tumors (4) | |

| Hemangioma (1) | |

| Intercalated duct adenoma (1) | |

| Lipoma (1) | |

|

| |

| Lymphomas (6) | Neoplastic-malignant (14) |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (3) | |

| Acinic cell carcinoma (1) | |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenoma (with | |

| epithelial/myoepithelial differentiation) (1) | |

| Carcinoma with squamous/basaloid features (1) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma, metastatic (1) | |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma (1) | |

• 15 confirmed with flow cytometry studies

Among the 62 cases in originally classified MSRSGC category III (Atypical), seventeen were proven to be non-neoplastic lesions on resection, while 45 cases showed the presence of a neoplasm (22 benign and 23 malignant neoplasms). The diagnoses are summarized in table 4. The benign neoplasms in this category were represented by 10 pleomorphic adenomas and 8 Warthin tumors. The most common malignant lesions in this category were 8 cases of lymphoma and 7 cases of mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC)12. The histological diagnoses of each lesion in this category are listed in Table 4.

Table 4:

Histologic follow up for cytology cases diagnosed as atypical (MSRSGC category III) (n=62)

| Histologic diagnosis | Corresponding MSRSGC category |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Benign cysts (5) | Non-neoplastic (17) |

| Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (2) | |

| Salivary gland tissue with chronic inflammation (10) | |

|

| |

| Pleomorphic adenomas (10) | Neoplastic-benign (22) |

| Warthin tumors (8) | |

| Benign oncocytic neoplasm (2) | |

| Cystadenoma (1) | |

| Hemangioma (1) | |

|

| |

| Lymphomas (8) | Neoplastic-malignant (23) |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (7) | |

| Acinic cell carcinoma (3) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma (2) | |

| Carcinoma with squamous features (1) | |

| High grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, metastatic (1) | |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma (1) | |

One hundred and six cases were originally diagnosed cytologically as benign neoplasms (MSRSGC category IVa), of which 26 demonstrated the presence of a malignant neoplasm leading to a ROM of 25%. The histological diagnoses for lesions in this category are listed in table 5. The most common malignant neoplasms identified on resection in this MSRSGC category were carcinomas with at least focal myoepithelial differentiation (17 of 26) followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma (3 of 26).

Table 5:

Histologic follow up for cytology cases diagnosed as neoplastic-benign (MSRSGC category IVa) (n=106)

| Histologic diagnosis | Corresponding MSRSGC category |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Benign parotid tissue with prominent neurovascular bundle (1) | Non-neoplastic (1) |

|

| |

| Pleomorphic adenomas (58) | Neoplastic-benign (79) |

| Warthin tumors (15) | |

| Oncocytomas (4) | |

| Basal cell adenomas (2) | |

|

| |

| Myoepithelial carcinomas (14) | Neoplastic-malignant (26) |

| -myoepithelial carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (10) | |

| -myoepithelial carcinoma (4) | |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinomas (3) | |

| Adenoid cystic carcinomas (3) | |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (1) | |

| Polymorphous adenocarcinoma (1) | |

| Malignant solitary fibrous tumor (1) | |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenoma, salivary duct carcinoma type (1) | |

| Acinic cell carcinoma (1) | |

| Oncocytic carcinoma (1) | |

A total of 141 cases were included in the MSRSGC category IVb (salivary gland of uncertain malignant potential). The presence of a neoplasm was confirmed in 134 cases, while 7 cases did not show the presence of a neoplasm on resection. Six of the 7 cases that did not show the presence of a neoplasm were cystic lesions with oncocytic changes and associated inflammation and 1 case was a case of intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia. The RON in this category was 95% and the risk of malignancy was 62%. The histological findings are summarized in table 6.

Table 6:

Histologic follow up for cytology cases diagnosed as neoplastic-Uncertain malignant potential (MSRSGC category IVb) (n=141)

| Histologic diagnosis | Corresponding MSRSGC category |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Salivary gland tissue with chronic inflammation (3) | Non-neoplastic (7) |

| Salivary gland tissue with oncocytic changes (3) | |

| Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia (1) | |

|

| |

| Pleomorphic adenomas (28) | Neoplastic-benign (47) |

| Oncocytoma (6) | |

| Warthin tumors (5) | |

| Basal cell adenomas (3) | |

| Schwannoma (3) | |

| Cylindroma (1) | |

| Intercalated duct adenoma. (1) | |

|

| |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenomas, salivary duct carcinoma (4) | Neoplastic-malignant (87) |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenomas, myoepithelial carcinoma (6) | |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenomas, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma (1) | |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenomas, high grade carcinoma (1) | |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (12) | |

| Myoepithelial carcinomas (11) | |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinomas (10) | |

| Acinic cell carcinomas (10) | |

| Adenoid cystic carcinomas (8) | |

| Basal cell adenocarcinomas (6) | |

| Secretory carcinomas (4) | |

| Salivary duct carcinomas (3) | |

| Melanomas (2) | |

| Squamous cell carcinomas (2) | |

| Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma (1) | |

| Oncocytic carcinoma (1) | |

| Polymorphous adenocarcinoma (1) | |

| Low grade salivary carcinoma with myoepithelial and ductal features (1) | |

| High grade carcinoma, NOS (1) | |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma (1) | |

| Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (1) | |

FNAB cases originally diagnosed as suspicious (MSRSGC category V) accounted for 41 cases in this series, of which 36 were shown to be malignant neoplasms on resection and one case was a benign neoplasm resulting in a RON of 90% and a ROM of 88%. The histological diagnoses for lesions in this category are summarized in table 7. Four misclassified lesions in this category were nonneoplastic lesions with either inflammatory or oncocytic changes/squamous metaplasia.

Table 7:

Histologic follow up for cytology cases diagnosed as Suspicious (MSRSGC category V) (n=41)

| Histologic diagnosis and flow cytometry | Corresponding MSRSGC category |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Cysts with oncocytic/squamous changes (2) | Non-neoplastic (4) |

| Sialadenitis (2) | |

|

| |

| Pleomorphic adenoma(1) | Neoplastic-benign (1) |

|

| |

| Lymphomas (20) | Neoplastic-malignant (36) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma (3) | |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (2) | |

| Salivary duct carcinomas (2) | |

| Acinic cell carcinomas (2) | |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenomas, salivary duct carcinoma (1) | |

| Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenomas, high grade carcinoma (1) | |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinomas (1) | |

| Basal cell adenocarcinomas (1) | |

| Metastatic breast carcinoma (1) | |

| High grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (1) | |

| Liposarcoma (1) | |

A total of 222 cases were included in the MSRSGC malignant category (MSRSGC category VI) and the subsequent tissue specimen confirmed the presence of a neoplasm in 221 cases, of which 220 cases were malignant resulting in a ROM of 99%. One case originally thought to be malignant on FNAB demonstrated to be a basal cell adenoma on resection, while one case did not show the presence of a neoplasm on resection. This latter case contained an increased number of large lymphoid cells and was thought to represent lymphoma. However, the resection specimen demonstrated the presence of a lymph node with florid follicular hyperplasia. The histological diagnoses for lesions in this category are listed in table 8.

Table 8:

Histologic follow up for cytology cases diagnosed as Malignant (MSRSGC category VI) (n=222)

| Histologic diagnosis and flow cytometry | Corresponding MSRSGC category |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (1) | Non-neoplastic (1) |

|

| |

| Basal cell adenoma (1) | Neoplastic-benign (1) |

|

| |

| Carcinomas (124) | Neoplastic-malignant (220) |

| - Squamous cell carcinomas (42) | |

| - Salivary duct carcinomas (4 Ca-Ex-PA) (25) | |

| - Acinic cell carcinomas (10) | |

| - Merkel cell carcinomas (9) | |

| - Metastatic carcinomas (9) | |

| - Mucoepidermoid carcinomas (8) | |

| - Adenoid cystic carcinomas (6) | |

| - Secretory carcinoma (1) | |

| - Basal cell adenocarcinoma, (1) | |

| - High grade Carcinoma-Ex PA (1) | |

| - Oncocytic carcinoma (1) | |

| - Epithelial-Myoepithelial carcinoma (1) | |

| - Carcinomas with squamous features (2) | |

| - Carcinoma with basaloid and squamous features (1) | |

| - High grade salivary gland carcinoma with myoepithelial features (1) | |

| - Carcinoma Ex-pleomorphic adenoma (1) | |

| - High grade carcinoma, NOS (1) | |

| - High grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (1) | |

| - Adenocarcinoma (1) | |

| - Adenocarcinoma with mucinous and signet ring features, primary vs. Metastasis (1) | |

| - Carcinoma, primary vs. Breast origin (1) | |

| Lymphomas (58) | |

| Melanomas (34) | |

| Sarcomas (2) | |

| Ependymoma (1) | |

| Malignant epithelioid neoplasm, NOS (1) | |

DISCUSSION

The results of this study had similar demographic distribution as those previously reported studies. The age range was broad with increased frequency of neoplasms between ages 41–80 years[18] We also observed a slight female predominance in this series, a finding also seen in prior studies[19, 20]. Similar to prior studies, most of the salivary gland neoplasms were found in the major salivary glands [21–23]. The distribution of the cases among the different MSRSGC categories was different from the one seen in prior other studies[19, 20, 24, 25] with a higher prevalence of malignant cases. One difference was the much higher number of cases in the malignant category. The differences could be attributed to the nature of our institution as a tertiary cancer center and the fact that only cases with histological correlation were included in this study.

The high RON (71%) seen in MSRSGC category I highlights the importance of adequacy assessment and radiological correlation to determine if the lesion was correctly sampled. Ten FNAB cases that demonstrated to be neoplasms on resection in this category did not contain diagnostic cells. The remaining 5 neoplasms were represented by benign vascular lesions that are difficult to sample by FNAB. The ROM in MSRSGC category I in this series (29%) is higher than found by Lui et al, but within the range seen in the literature.[26] The possible causes of discrepancy might be attributed to the case type distribution in each institution or study.

The cases included in the non-neoplastic categories (MSRSGC category II) were mostly lesions containing lymphocytes. The diagnosis of sialadenitis on ultrasound or other imaging studies can be challenging when it is not bilateral[27, 28] The FNAB specimens correctly diagnosed as non-neoplastic were represented by reactive lymphoid population, a diagnosis confirmed by flow cytometry studies and/or follow up; or cystic lesions associated with lymphocytes (n=38). Four cases subsequently diagnosed as lymphoma contained small lymphocytes, but no concurrent flow cytometry studies were performed at the time of the FNAB. Two cases of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL)13 were misdiagnosed as benign. The diagnosis of NLPHL is challenging in cytology specimens and requires an excision for a definite diagnosis. The remaining 20 FNA cases that demonstrated the presence of a neoplasm on resection did not contain diagnostic cells of the lesion in question, and the cytology specimens consisted only of benign salivary tissue, lymphocytes, and/or cyst contents. These findings highlight the importance of radiological correlation and additional sampling if the specimen contains only lymphocytes and a nodule/mass is present. It is important to remember that the diagnosis of sialadenitis on ultrasound or in other imaging study can be challenging when it is not bilateral[27, 28] Although the ROM in this category (22%) is higher than the average described by Lui et al (10.8%)[26], the ROM decreases to 3% if the lesions later considered being a sampling error and lesions without flow cytometry studies are excluded from the calculation. These findings suggest that the MSRSGC category II diagnosis should be used judiciously with adequate radiological correlation.

The histological diagnosis following a MSRSGC category III (Atypical) diagnosis included 22 benign neoplasms (10 pleomorphic adenomas and 8 Warthin tumors) and 23 malignant neoplasms. A definite diagnosis could not be rendered due to the paucity of diagnostic cells, or lack of adequate ancillary studies in all cases. The most common malignant lesions included in this category were 8 cases of low-grade lymphoma. None of these lymphoma cases had concurrent diagnostic flow cytometry studies to support the diagnosis. The most common lymphoma arising in the salivary gland is extranodal marginal zone lymphoma. [29] However, the diagnosis of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma can be difficult morphologically as it is represented by a population of small atypical lymphocytes admixed with a reactive lymphoid population in the background. The neoplastic population can only be reliably detected by flow cytometry studies. The proposed Sydney system for reporting lymph nodes also suggests the classification of these lesions as atypical if lymphomas cannot be ruled out and there are no supporting flow cytometry studies.[30] The second most common malignancy encountered in this category was MEC (n=7) that contained only a few cells with abundant cytoplasm in the cytology specimen and the differential diagnosis included Warthin tumor. Both MEC and Warthin tumors can be challenging to diagnose on FNAB, particularly in hypocellular specimen. Torous et al reported that a definite diagnosis of Warthin tumor can be challenging in a hypocellular specimens[31], while Miller et al described a relatively lower diagnostic accuracy (78.7%) for cases of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. [32]

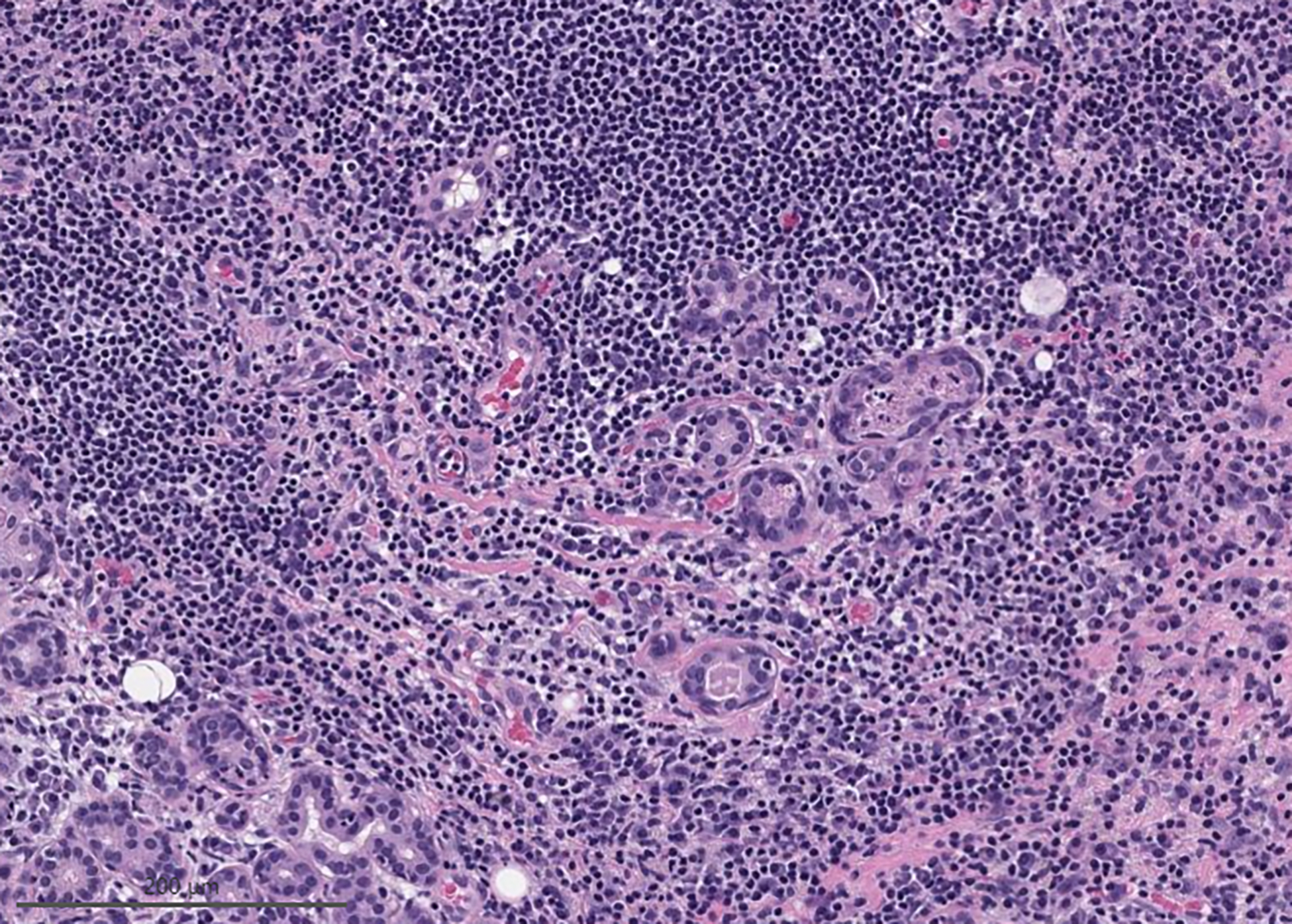

Most cases included in the MSRSGC category IVa were correctly diagnosed as neoplastic. However, the ROM (25%) in our study was higher than described in the literature.[26] The higher ROM observed might be attributed to the type of cases seen in our institution, a major tertiary cancer center. While previous studies reported that most cases were included in MSRSGC category IVa, our series had more cases classified as MSRSGC category VI (n=222) than MSRSGC category IVa (n=106). Carcinomas with myoepithelial differentiation represented most of the malignant cases originally reported as MSRSGC category IVa (17 of 26). Among these 17 cases, 10 were reported as myoepithelial carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma on excision and 4 were myoepithelial carcinomas. The diverse morphology of myoepithelial cells and the inability to fully evaluate the capsule in the cytology specimens makes it difficult to make a diagnosis of myoepithelial carcinoma in FNAB specimens. (figure 1) Furthermore, the presence of hyalinized or myxoid stroma can be misleading as similar features can be seen in myoepithelial rich pleomorphic adenomas and myoepithelial neoplasms. These discordant cases highlight the challenges faced in the diagnosis of carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma in the form of myoepithelial carcinoma using FNAB. This diagnosis requires extensive histological evaluation of the lesion. There is currently no biomarker that can reliably distinguish a benign myoepithelial lesion from a malignant one. This finding suggests that all lesions with abundant myoepithelial cells are best classified as salivary gland neoplasms of uncertain malignant potential, even when metachromatic material is present. Based on this study, an abundance of myoepithelial cells in a salivary gland FNA might suggest a myoepithelial neoplasm or myoepithelial carcinoma arising in a background of pleomorphic adenoma. This finding highlights the importance of the quality assurance program to identify root causes for misclassification of malignant lesions as benign and highlights challenges in the interpretation of myoepithelial rich lesions. It also confirms the findings from Reerds et al who identified myoepithelial carcinomas as the most common cause of a false-negative lesion with a false negative rate of 57%.[33] The identification of this root cause has led to a change in our diagnostic approach to myoepithelial rich lesions with the adoption of more strict criteria for lesions included in category IVa. Interestingly, no lymphoid lesions were included in this category.

Figure 1:

Case initially misdiagnosed as benign neoplasm; Myoepithelial carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. A) Smear containing abundant myoepithelial cells associated with metachromatic stroma (Modified Giemsa stained slide) B) Surgical resection showing the presence of myoepithelial carcinoma next to a pleomorphic adenoma C) Myoepithelial carcinoma showing myoepithelial cells with varying degrees of atypia.

The RON in the MSRSGC IVb was 95% and the ROM was 62%. There was a wide variety of malignant lesions included in this category that could be correctly diagnosed as malignant if ancillary studies were performed. Recently described immunocytochemical and molecular markers probably would have allowed better classification of some of these malignant neoplasms. No ancillary studies were performed among the malignant neoplasms in this category due to a lack of material for additional studies or because the cases preceded the identification of the diagnostic markers. The non-neoplastic cases in this category were represented by cases of sialadenitis with epithelial atypia, (figure 2) some in the form of oncocytic changes.

Figure 2:

Case initially misdiagnosed as neoplastic A) Clusters of basal cells associated with lymphocytes, which was initially thought to represent a basal cell adenoma. (Modified Giemsa stain) B) Surgical resection demonstrated chronic sialadenitis.

High RON and ROM were seen in MSRSGC category V as expected, however, 4 cases were found to be non-neoplastic lesions on resection. The histological sections demonstrated the presence of sialadenitis with reactive epithelial atypia. These findings suggest that close correlation with radiological findings and a conservative approach are suggested in the interpretation of cases with associated inflammation. This potential pitfall has been previously reported by several authors. [10, 23, 24, 34–38]

The MSRSGC category VI ROM was 99%. The only case that demonstrated to be non-neoplastic on resection was a case of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia containing many centroblasts. The case was initially interpreted as large cell lymphoma. No flow cytometry studies were performed in this case, highlighting the importance of ancillary studies in lymphoid rich lesions. Only one additional case in this category was not a malignant lesion on resection. It was a case of basal cell adenoma, which was diagnosed before the implementation of the MSRSGC in our institution. In retrospect, this lesion would be best categorized as category IVb.

Our findings demonstrated that salivary gland FNAB is a good diagnostic tool for the detection of neoplasms with RON above 90% in MSRSGC categories IV and above. This QA process allowed the identification of diagnostic approaches that might help to prevent future misdiagnosis or misclassifications. Salivary gland masses composed of lymphoid cells require a careful approach with accompanying flow cytometry studies, whenever possible. Inflammation can induce marked epithelial atypia as seen in non-neoplastic cases seen in MSRSGC categories IV-VI in our series. Myoepithelial cell rich lesions might be better categorized as MSRSGC category IVb to avoid underdiagnosis.

Funding/Disclosure:

This study was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Oscar Lin, MD PhD is a consultant for Hologic and Janssen

The manuscript represents one of the largest studies evaluating a quality assurance (QA) program for salivary gland fine needle aspiration (FNA) in the context of the Milan System For reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology at a major cancer center. The studies included a root cause analysis of the discrepancies identified in this QA process.

FNAB- Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy

MSRSGC- Milan system for reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology

RON- Risk of Neoplasm

ROM-Risk of Malignancy

FNAC- Fine-needle aspiration cytology

CHC- Cytologic-histologic correlation

QA- Quality Assurance

NILM- Negative for intraepithelial lesion and malignancy

HSIL- High-Grade intraepithelial lesion

CLIA- Clinical laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988

IRB- Institutional Review Board

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

NLPHL- Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colella G, et al. , Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2010. 68(9): p. 2146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson AE, <clinical experience Thhinprep imager - Copy.pdf>. Acta Cytol, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain R, et al. , Fine needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of salivary gland lesions: A study with histologic comparison. Cytojournal, 2013. 10: p. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kala C, Kala S, and Khan L, Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: An Experience with the Implication for Risk of Malignancy. J Cytol, 2019. 36(3): p. 160164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt RL, et al. , A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of fine-needle aspiration cytology for parotid gland lesions. Am J Clin Pathol, 2011. 136(1): p. 45–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu CC, et al. , Sensitivity, Specificity, and Posttest Probability of Parotid Fine-Needle Aspiration: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2016. 154(1): p. 9–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt RL, et al. , Diagnostic accuracy studies of fine-needle aspiration show wide variation in reporting of study population characteristics: implications for external validity. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2014. 138(1): p. 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyagi R and Dey P, Diagnostic problems of salivary gland tumors. Diagn Cytopathol, 2015. 43(6): p. 495–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Hussein S and Khader SN, Cytopathology approach to rare salivary gland lesions with oncocytic features. Diagnostic Cytopathology, 2019. 47(10): p. 1090–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith CC, et al. , Salivary Gland Tumor Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 2015. 143(6): p. 839–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hang JF, et al. , Multi-institutional validation of a modified scheme for subcategorizing salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (SUMP). Cancer Cytopathol, 2022. 130(7): p. 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seethala RR, Basaloid/blue salivary gland tumors. Modern Pathology, 2017. 30(S1): p. S84–S95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantley RL, Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology of Cellular Basaloid Neoplasms of the Salivary Gland. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 2019. 143(11): p. 1338–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gargano SM, et al. , Cytohistologic correlation of basaloid salivary gland neoplasms: Can cytomorphologic classification be used to diagnose and grade these tumors? Cancer Cytopathology, 2020. 128(2): p. 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pusztaszeri M, et al. , Salivary Gland Fine Needle Aspiration and Introduction of the Milan Reporting System. Adv Anat Pathol, 2019. 26(2): p. 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crothers BA, et al. , Quality improvement opportunities in gynecologic cytologic-histologic correlations: findings from the College of American Pathologists Gynecologic Cytopathology Quality Consensus Conference working group 4. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2013. 137(2): p. 199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Administration, D.o.H.a.H.S.H.C.F., Clinical Laboratory improvement amendments of 1998—standard: cytology.. Codified at 42 CFR §493.1274(c)(2). Fed Regist. 1992;57(40):7146. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horvath L and Kraft M, Evaluation of ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration in the assessment of head and neck lesions. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 2019. 276(10): p. 2903–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castrodad‐Rodríguez CA, et al. , Application of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: Experience of an academic institution in a tertiary academic medical center. Cancer Cytopathology, 2021. 129(3): p. 204–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leite AA, et al. , Retrospective application of the Milan System for reporting salivary gland cytopathology: A Cancer Center experience. Diagnostic Cytopathology, 2020. 48(9): p. 821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araya J, et al. , Incidence and prevalence of salivary gland tumours in Valparaiso, Chile. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal, 2015: p. e532–e539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinheimer A, et al. , Retrospective study of 124 cases of salivary gland tumors and literature review. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry, 2019: p. 0–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajwanshi A, et al. , Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary glands: Diagnostic pitfalls—revisited. Diagnostic Cytopathology, 2006. 34(8): p. 580–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hafez NH and Abusinna ES, Risk assessment of salivary gland cytological categories of the milan system: a retrospective cytomorphological and immunocytochemical institutional study. Turkish Journal of Pathology, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaushik R, et al. , Incorporation of the Milan system in reporting salivary gland fine needle aspiration cytology—An insight into its value addition to the conventional system. Diagnostic Cytopathology, 2020. 48(1): p. 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lui SK, et al. , Nondiagnostic salivary gland FNAs are associated with decreased risk of malignancy compared with “all-comer” patients: Analysis of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology with a focus on Milan I: Nondiagnostic. Cancer Cytopathol, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rollins SD and Elshenawy Y, Images for the interventional cytopathologist: Salivary gland ultrasound and cytology. Cancer Cytopathology, 2019. 127(11): p. 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman HT and Pagedar NA, Ultrasound-Guided Salivary Gland Techniques and Interpretations. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am, 2018. 26(2): p. 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbondanzo SL, Extranodal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma of the salivary gland. Ann Diagn Pathol, 2001. 5(4): p. 246–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Abbadi MA, et al. , A Proposal for the Performance, Classification, and Reporting of Lymph Node Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytopathology: The Sydney System. Acta Cytol, 2020. 64(4): p. 306–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torous VF and Faquin WC, The Milan System classification of Warthin tumor: A large institutional study of 124 cases highlighting cytologic features that limit definitive interpretation. Cancer Cytopathol, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller JA, et al. , Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, and adenoid cystic carcinoma on fine-needle aspiration biopsy and The Milan System: an international multi-institutional study. J Am Soc Cytopathol, 2019. 8(5): p. 270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reerds STH, et al. , Accuracy of parotid gland FNA cytology and reliability of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology in clinical practice. Cancer Cytopathol, 2021. 129(9): p. 719–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirata Y, et al. , Application of the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: A 10-Year Experience in a Single Japanese Institution. Acta Cytologica, 2020: p. 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maleki Z, et al. , “Suspicious” salivary gland FNA: Risk of malignancy and interinstitutional variability. Cancer Cytopathology, 2018. 126(2): p. 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JH, et al. , A retrospective cytohistological correlation of fine-needle aspiration cytology with classification by the Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine, 2020. 54(5): p. 419–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salehi S and Maleki Z, Diagnostic challenges and problem cases in salivary gland cytology: A 20-year experience. Cancer Cytopathology, 2018. 126(2): p. 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, et al. , “Atypical” salivary gland fine needle aspiration: Risk of malignancy and interinstitutional variability. Diagnostic Cytopathology, 2017. 45(12): p. 1088–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]