Abstract

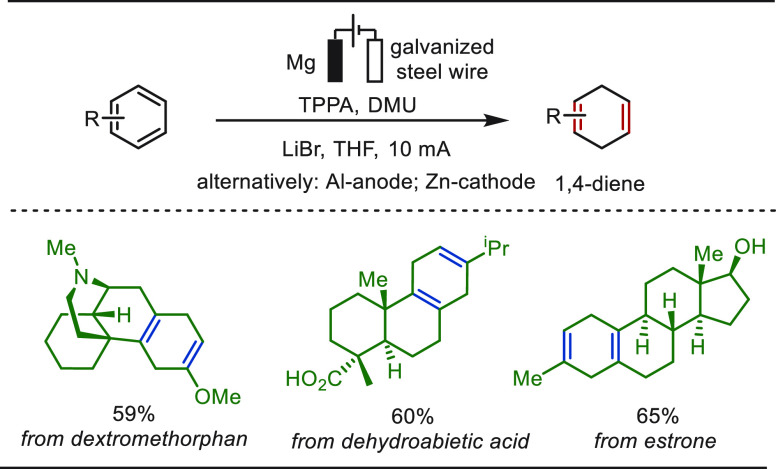

Late-stage functionalization (LSF) constitutes a powerful strategy for the assembly or diversification of novel molecular entities with improved physicochemical or biological activities. LSF can thus greatly accelerate the development of medicinally relevant compounds, crop protecting agents, and functional materials. Electrochemical molecular synthesis has emerged as an environmentally friendly platform for the transformation of organic compounds. Over the past decade, electrochemical late-stage functionalization (eLSF) has gained major momentum, which is summarized herein up to February 2023.

1. Introduction

The direct and site-selective late-stage diversification of structurally complex molecules is of great potential for drug discovery, materials science, crop protection, and other areas.1−8 This approach avoids a complete de novo synthesis of a target molecule, enables the rapid creation of large compound libraries, and hence offers the promise of a fast exploration of structure–activity relationships (SARs). Thereby, an improvement of pharmacokinetics properties as well as physicochemical drug characteristics, such as potency, stability, solubility, and selectivity, is frequently viable.9 The most synthetically useful late-stage functionalization (LSF) strategy is often the direct installation of fluorophores or small, noninvasive groups—inter alia methyl, hydroxyl, chloro, fluoro, or trifluoromethyl—with a selectivity control at a specific site of an existing biologically relevant molecule. The introduction of a small group can dramatically affect the bioactivity profiles of a structurally complex pharmaceutical molecule. For instance, Pfizer found that the installation of a methyl group to a morpholine-containing compound of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) agonist, gave rise to a 45-fold potency increase.10 In the past decade, a large number of LSF approaches have been developed, including metal-catalyzed transformations,11−21 visible-light-induced photocatalysis22−34 and enzyme catalysis,35−43 among others (Scheme 1a).44−48

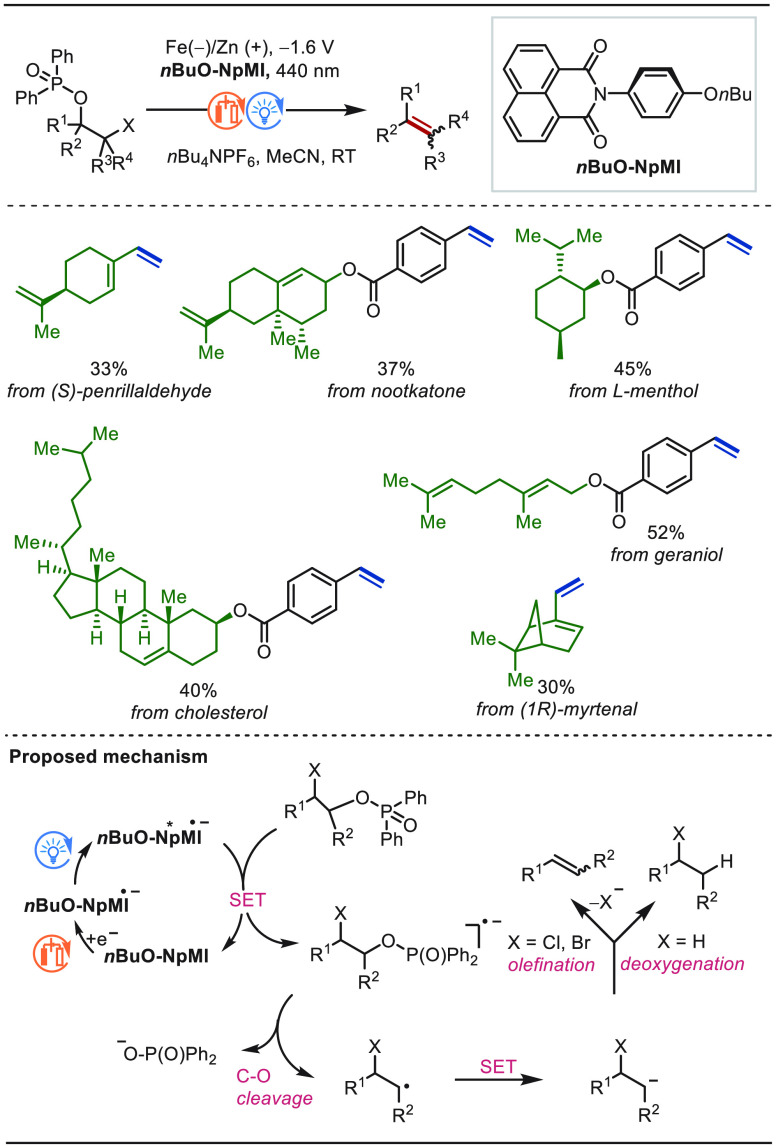

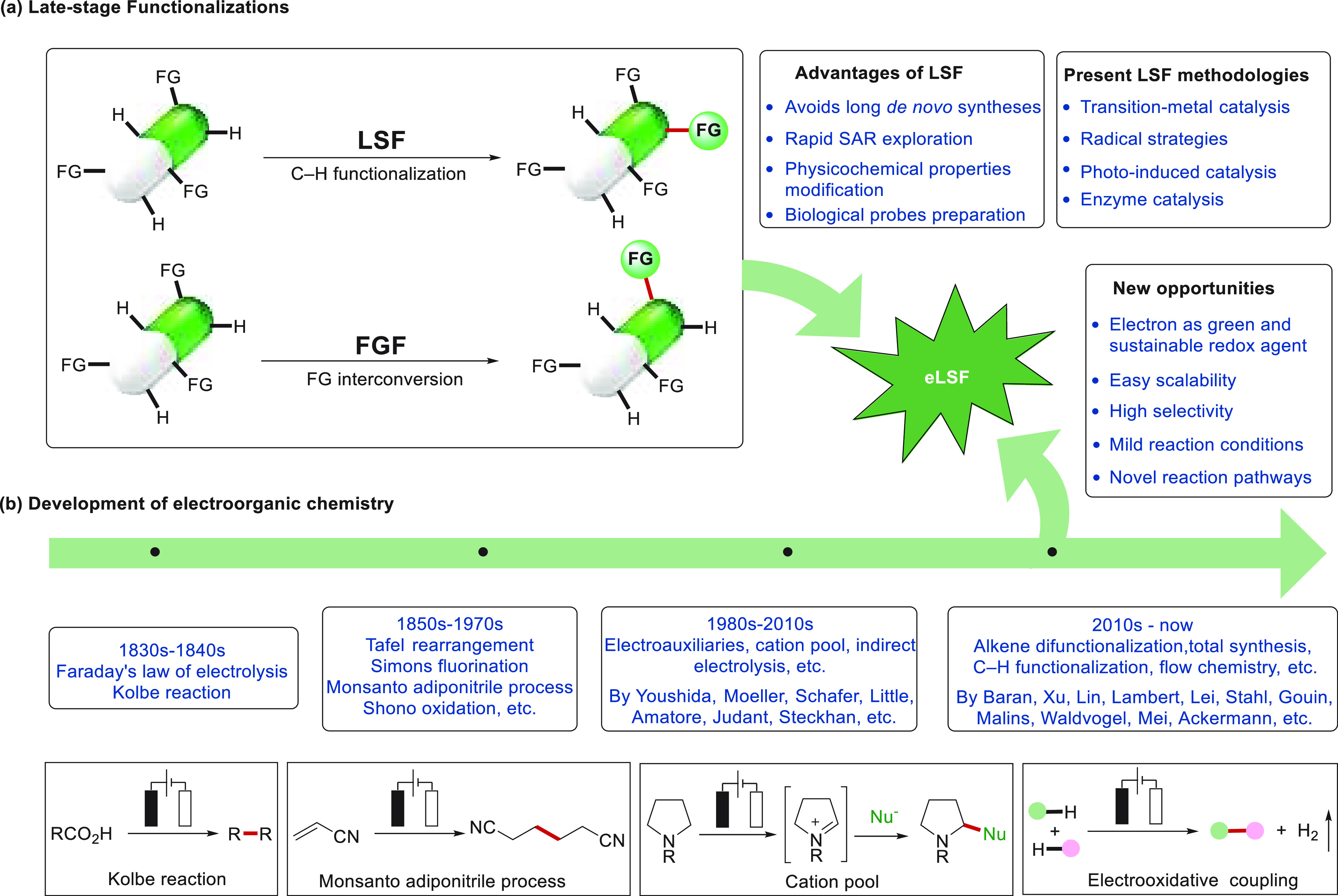

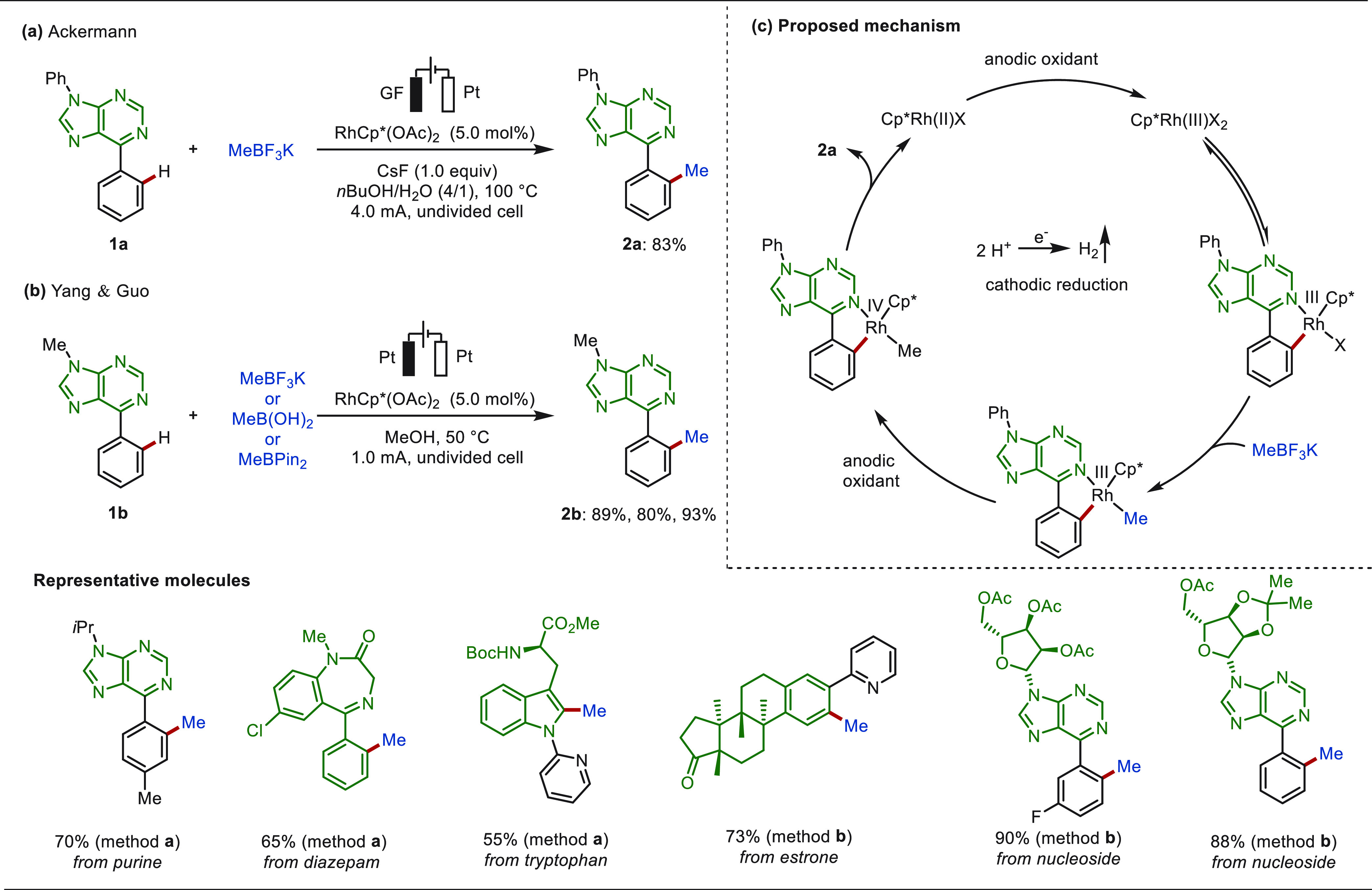

Scheme 1. Opportunities for Electrochemical Late-Stage Functionalization Strategies in Drug Discovery.

Electrochemical synthesis is a robust tool for sustainable molecular syntheses since it generally features mild reaction conditions, high selectivities, and facile scalability by flow techniques (Scheme 1b). Electrosynthesis has a history of nearly 200 years that can be traced back to Faraday’s conversion of acetic acid in the 1830s49 and Kolbe’s electrochemical decarboxylative dimerization,50 as well as industrially conducted processes, including the Simons fluorination process,51 the Monsanto adiponitrile process,52 and the Shono oxidation.53 Yoshida introduced the concepts of electroauxiliaries and cation pool to increase the electrosynthesis viability in the late 20th century.54−56 Meanwhile, Steckhan elegantly formalized the principles of indirect electrolysis, which thereafter brought forth numerous mediator-driven processes.57,58 Subsequent key achievements on the direct electrolysis were made by Schäfer,59 Lund,60 Little,61−63 Moeller,64 Jutand,65 and Amatore66 around the 21st century. On the basis of these pioneering contributions, electro-organic synthesis reemerged in the past decade, with major contributions by Baran,67 Xu,68 Lei,69 Ackermann,70 Lambert,71 Lin,72 Gouin,73 Waldvogel,74 Stahl,75 Malins,76 and Mei,77 among others.78−85 Thus, major advances have been achieved in various fields, including C–H activation, reductive cross-electrophile coupling, alkene difunctionalization, nitrogen-centered radical mediated chemistry, total synthesis, and the LSF of natural products and medicinally relevant molecules (Scheme 1b).

Over the years, a variety of articles have been published that summarized the impressive advances made in the field of electro-organic synthesis86−106 and late-stage functionalization,1−8,46,107−113 respectively. In contrast, comprehensive reviews of electrochemical late-stage functionalization has remained elusive.76 Thus, we herein aim at providing an overview on the advances in the area of electrochemical late-stage functionalization (eLSF), with a topical focus on biorelevant compounds. Notably, we define eLSF reactions as the direct, site-selective, and chemoselective functionalization of C–H bonds or endogenous functional groups on biologically relevant molecules, natural products, pharmaceuticals, or structurally complex molecules consisting of these moieties to provide their analogues. Such alterations may have the capacity to modulate properties, in a beneficial manner of binding affinity, drug metabolism, or pharmacokinetic properties, generally without loss of or even with an enhancement of the drug’s biological activity.

2. eLSF of C–H Bonds

Over the past decade, the merger of electrocatalysis with C–H activation has revolutionized the art of molecular synthesis. Particularly, a number of these electrochemical C–H functionalization techniques have been successfully applied for late-stage diversification of natural products and pharmaceuticals, and these key developments afforded tremendous opportunities in drug discovery programs.

2.1. eLSF of C(sp2)–H Bonds

2.1.1. Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Carbonization

Among numerous strategies for late-stage functionalization, the methylation reaction plays a unique role in the modulation of bioactive molecules.6 The incorporation of a simple methyl group can dramatically improve their potency by enhancing lipophilicity, metabolic stability, and binding interactions, among others, which are collectively referred as the “magic methyl effect”. A literature survey of >2000 cases revealed that 8% of methyl installations led to a > 10-fold potency boost, and >100-fold activity increases in 0.4% of cases.9 Consequently, and despite indisputable progress, new synthetic methylation strategies, particularly direct C–H methylation, are highly sought after.

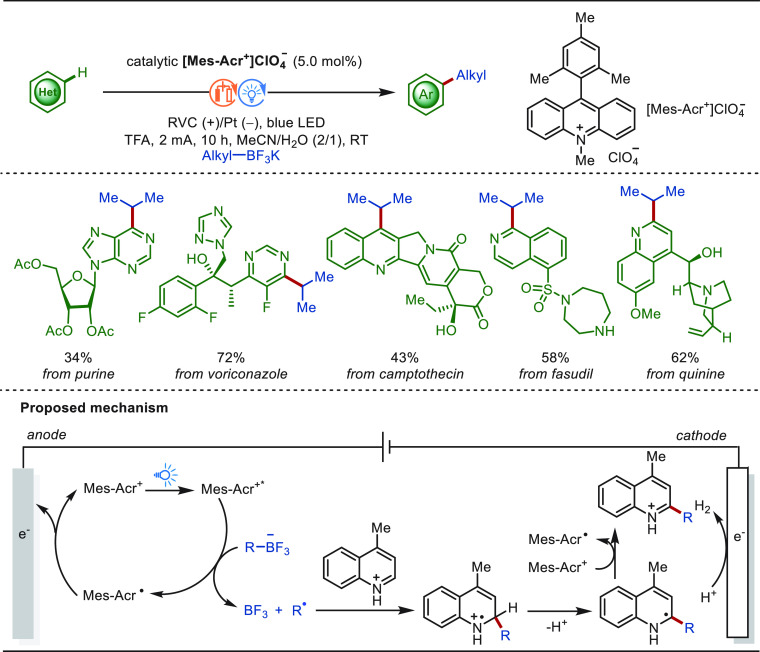

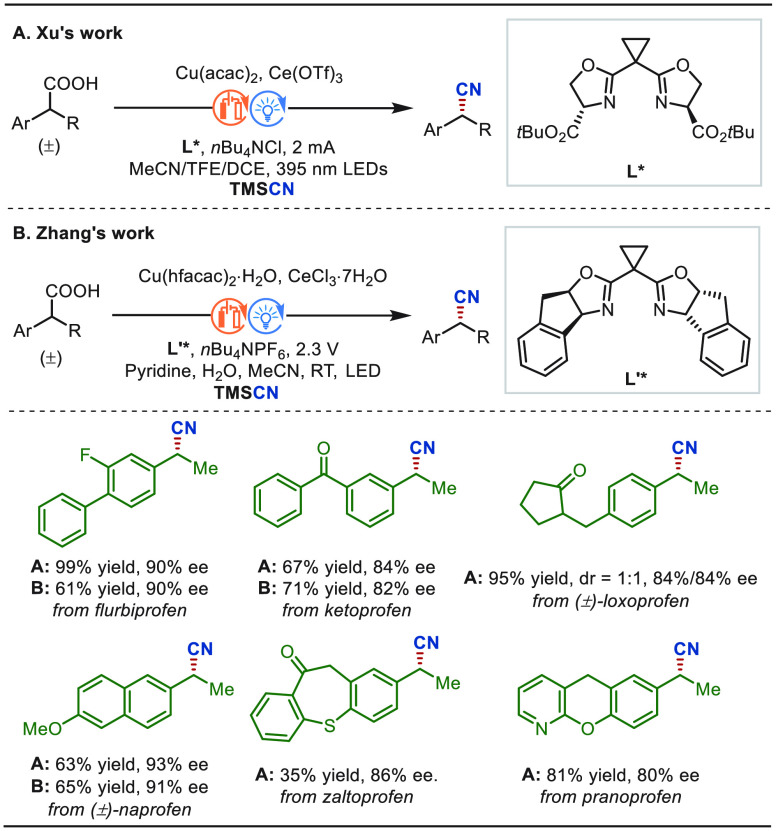

In 2017, Mei and co-workers first disclosed the electrochemical C(sp2)–H methylation via anodic oxidation with MeBF3K as the methyl source under the catalysis of Pd(OAc)2, offering an alternative methylation strategy to conventional method that requires strong chemical oxidants.114,115 In 2022, the Ackermann group reported on an electrochemical ortho C(sp2)–H methylation of N-heteroarenes with the aid of RhCp*(OAc)2 as a catalyst and MeBF3K as the methyl source in a mixture of nBuOH and H2O (Scheme 2a).116 This approach proceeded in a user-friendly undivided cell setup and has been successfully applied to various biologically molecules, including purines, diazepam, and amino acids with high levels of site- and monoselectivity. Shortly thereafter, Guo and co-workers described a similar transformation in MeOH. Besides MeBF3K, MeB(OH)2 and MeBPin were further used as coupling partners for this rhodaelectro-catalyzed C–H methylation (Scheme 2b).117 Hence, the eLSF of a variety of bioactive architectures including purines, estrone, nucleosides, and nucleotides were achieved under mild reaction conditions. Current was the only oxidant for this catalysis. Mechanistic studies indicated that an anodic-oxidation-induced reductive elimination occurred within a rhodium(III/IV/II) regime. Meanwhile, H2 was released as the byproduct at the cathode (Scheme 2).

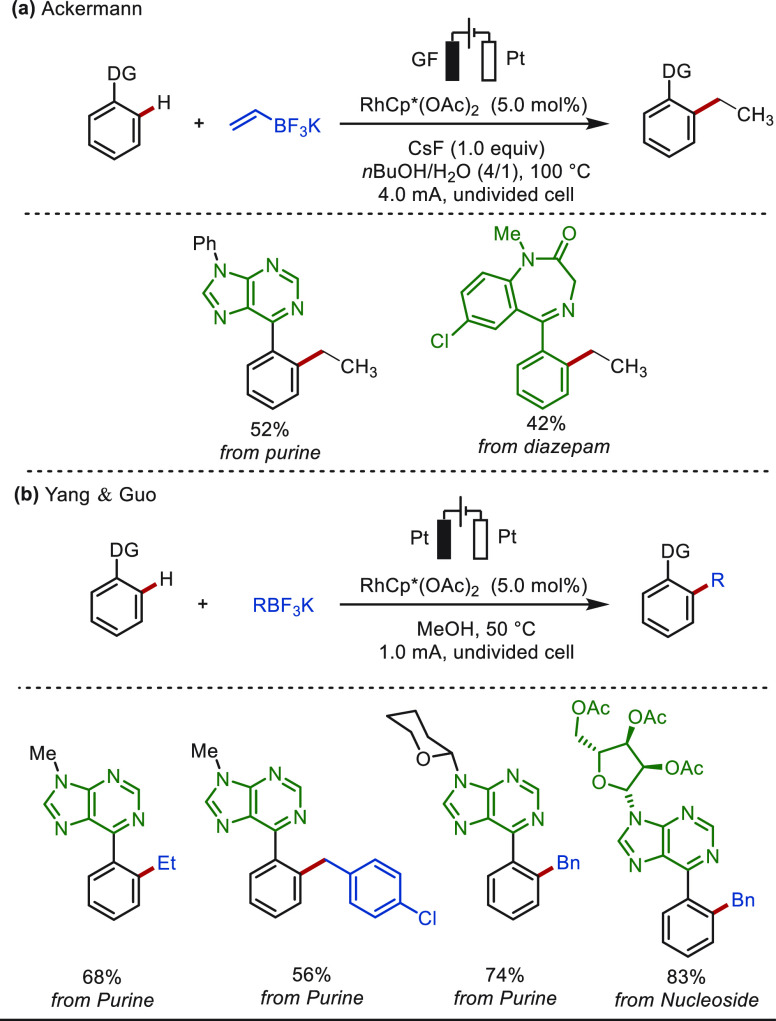

Scheme 2. Electrochemical Rhodium-Catalyzed Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Methylation.

In addition, the monoselective C–H ethylation of purines and diazepam was achieved by the Ackermann group with VinBF3K by paired electrolysis, in which the reduction of in situ generated vinylated products takes place at the cathode to afford the ethylated products (Scheme 3a).116 Under Guo’s reaction conditions, different alkylation agents was examined for the LSF of purine derivatives (Scheme 3b).117 While potassium ethyltrifluoroborate and potassium benzylic trifluoroborates were identified as suitable substrates, giving the desired alkylation products, other alkyltrifluoroborates (nbutyl, trifluoromethyl, and cyclohexyl) were unsuccessful.

Scheme 3. Electrochemical Rhodium-Catalyzed Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Alkylation.

Approximately 20% of commercial drugs contain at least one fluorine atom.118 The introduction of fluorine-containing groups leads to a significant boost in the potency of bioactive compounds.119,120 Particularly, trifluoromethylated compounds are in high demand in pharmaceutical industries and medicinal chemistry, since they can display unique lipophilicity and bioactivity.121,122 Consequently, direct C–H trifluoromethylation occupies an important position in terms of LSF.

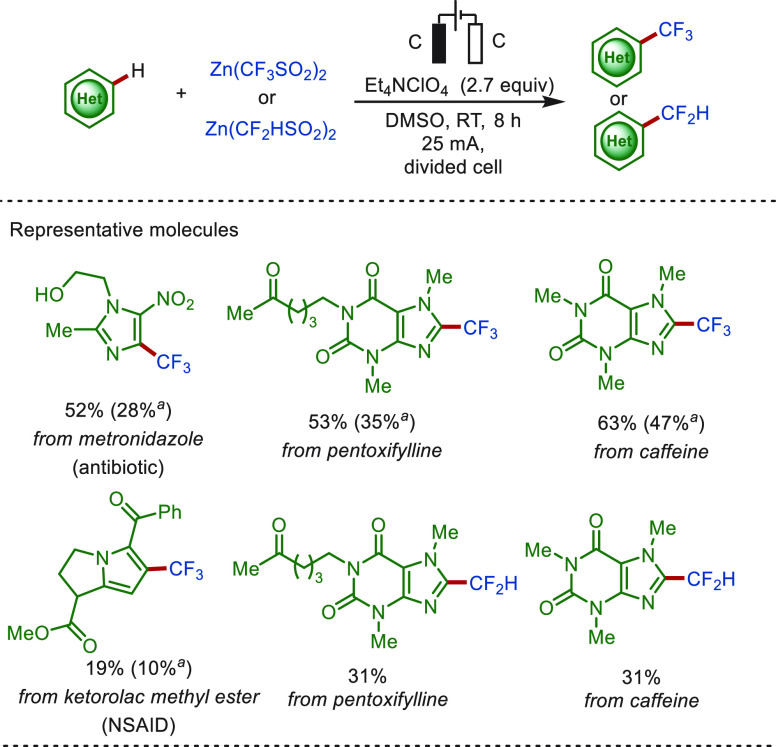

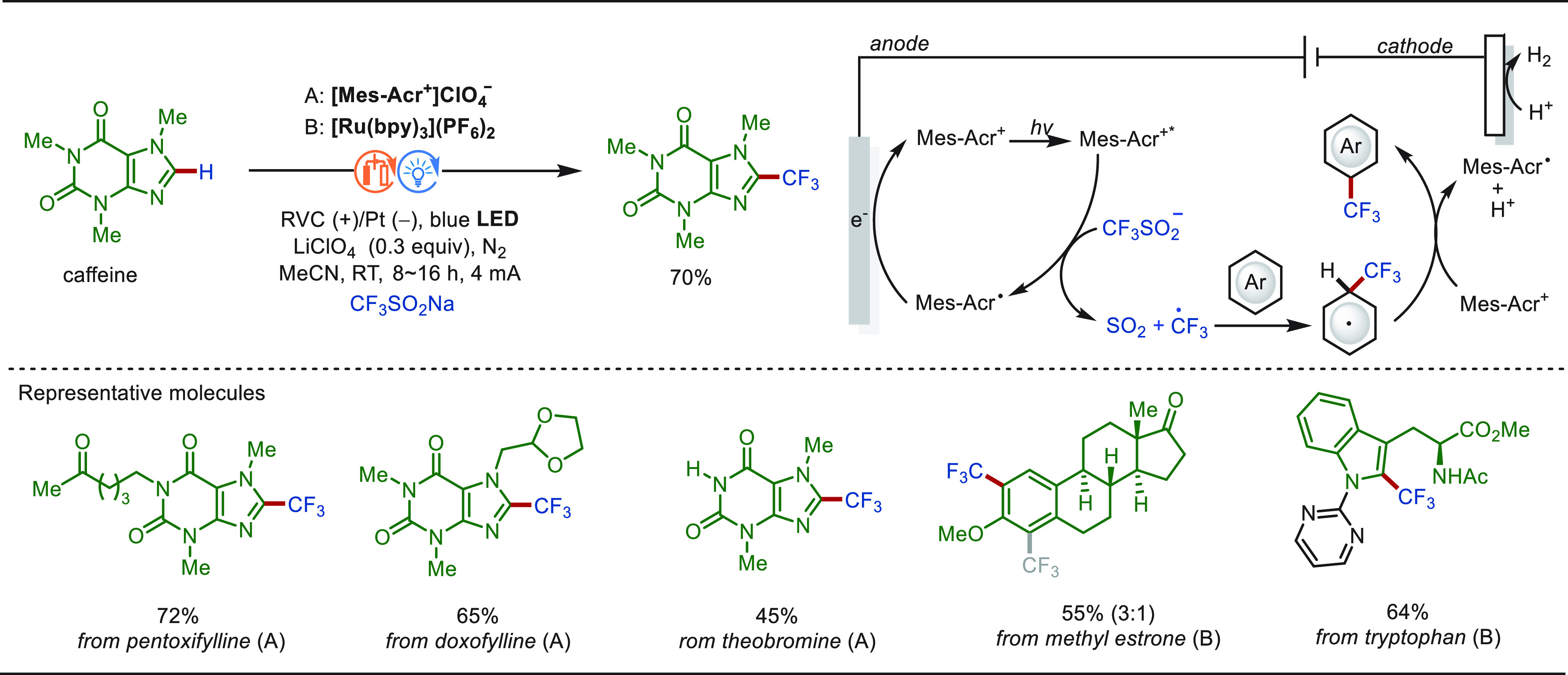

In 2014, Baran and co-workers reported an electrochemical C(sp2)–H trifluoromethylation of heterocyclics with Zn(CF3SO2)2 under constant current electrolysis (Scheme 4).123 This approach featured mild reaction conditions with high site-selectivity and offers a wide application for late-stage trifluoromethylation of molecular architectures, including metronidazole, pentoxifylline, caffeine, and ketorolac methyl ester. Notably, this strategy resulted in significantly improved yields compared to the traditional method using tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP) as the radical initiator and oxidant. Mechanistic studies indicated a controlled electron transfer at the anode, giving a sulfinate radical, which was rapidly converted to fluoroalkyl radical by cleavage and releasing SO2. Difluoromethylation of complex molecules was also achieved with Zn(CF2HSO2)2 at an elevated temperature of 60 °C, albeit in lower yield because of the poor reactivity of the CF2H radical with heterocycles.123

Scheme 4. Electrochemical Controlled C(sp2)–H Late-Stage Trifluoromethylation and Difluoromethylation.

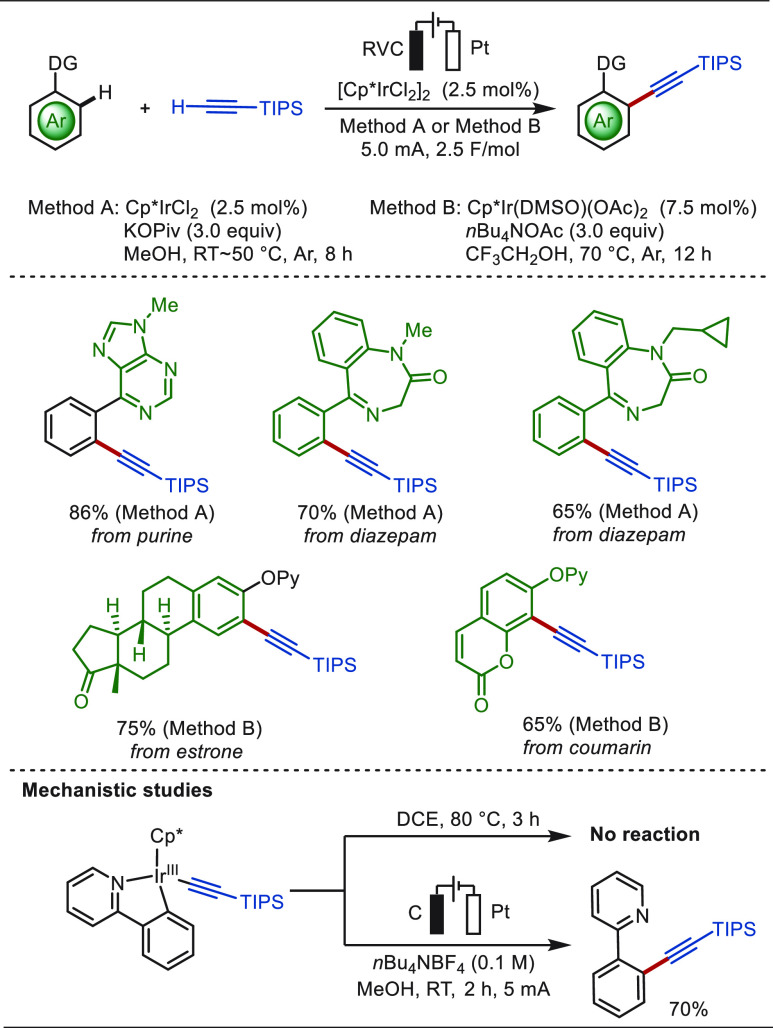

The transition-metal-catalyzed C–H alkynylation is a practical strategy in synthetic chemistry to install the versatile alkyne as a (transient) functional group.124−126 In 2020, Shi and Xie reported an electrochemical iridium-catalyzed directed C(sp2)–H alkynylation with terminal alkyne in an undivided cell (Scheme 5).127 Here, anodic oxidation was enabled by an iridium(III) intermediate to promote reductive elimination, affording the desired coupling products in excellent to good yields without the use of exogenous chemical oxidants. This transformation was amenable to various N-based directing groups, such as pyridyl, pyrazolyl, and isoquinolyl, enabling a high atom economy with H2 as the byproduct. The success of installing an alkyne on complex bioactive molecules, including derivatives of purine, diazepam, estrone, and coumarin, highlighted the potential application of this approach in late-stage functionalization of pharmaceuticals.

Scheme 5. Electrochemical Iridium-Catalyzed Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Alkynylation.

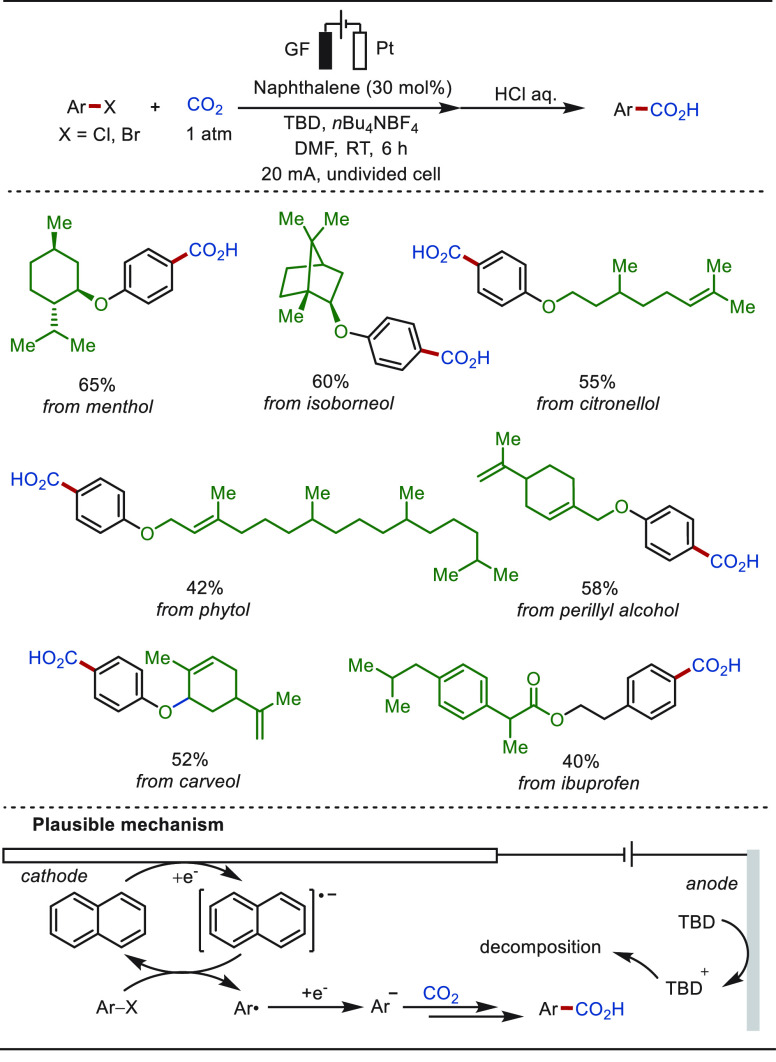

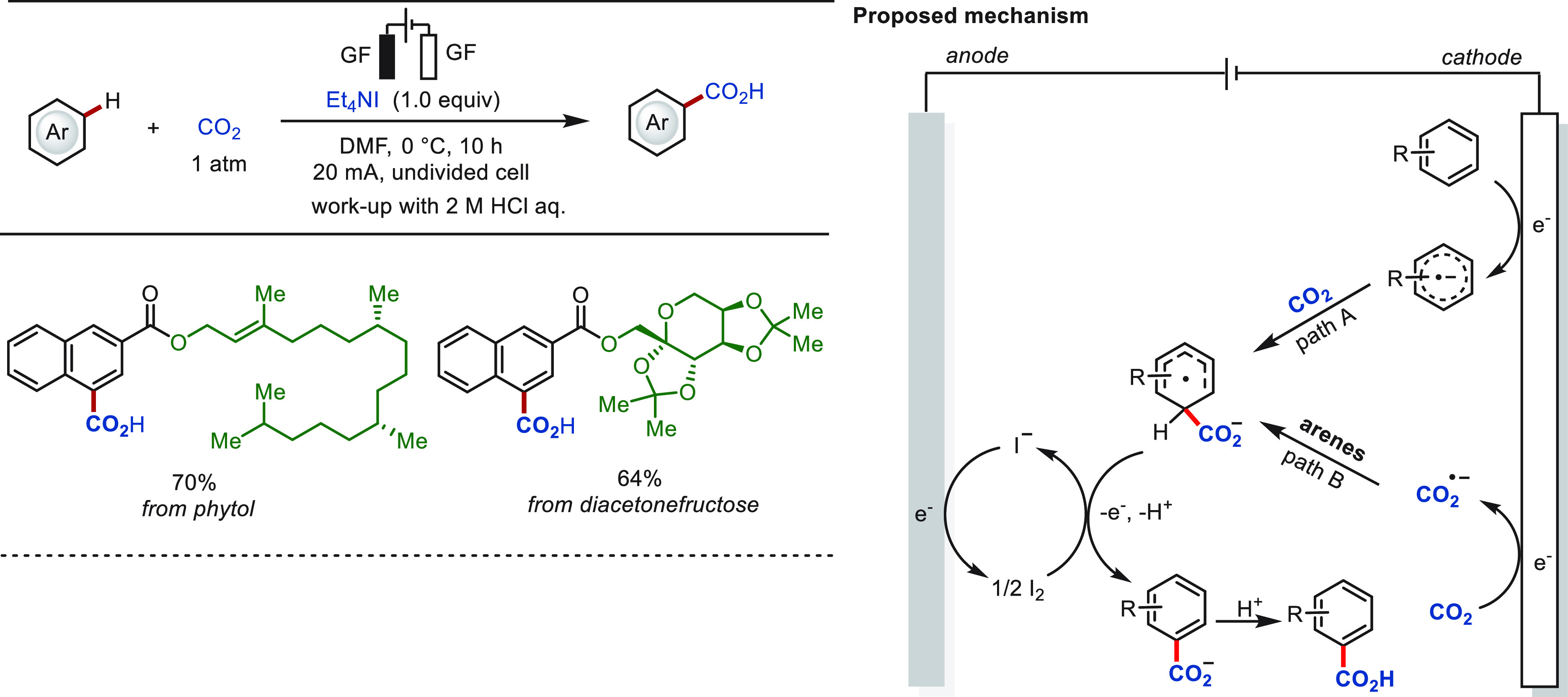

CO2 is an abundant C-1 source that has been widely used in electrochemical transformations to construct diverse carboxylic acid compounds or their derivatives.128−144 In 2022, the Qiu group reported a direct aromatic C(sp2)–H carboxylation approach with CO2 to access synthetically useful aryl carboxylic acids (Scheme 6).145 This transformation proceeded in an undivided cell, displaying high site selectivity and chemoselectivity and obviating the use of a transition-metal catalyst. An array of challenging arenes, including electron-deficient naphthalenes, as well as heteroarenes such as pyridines and substituted quinolines, proved to be suitable substrates. The late-stage carboxylation of bioactive molecules derived from phytol and diacetonefructose was achieved efficiently. For a substrate with a less negative reduction potential, the process commences with the arene reduction at the cathode to form the corresponding radical anion. By contrast, for a substrate with a more negative reduction potential than that of CO2, the transformation starts with the CO2 reduction to a CO2 radical anion.

Scheme 6. Electrochemical Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Carboxylation with CO2.

2.1.2. Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Oxygenation

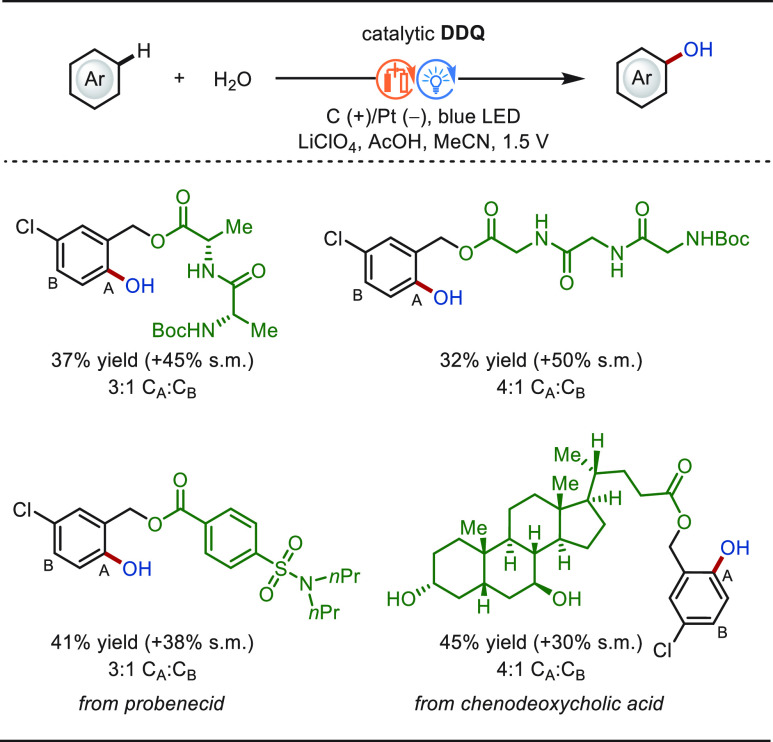

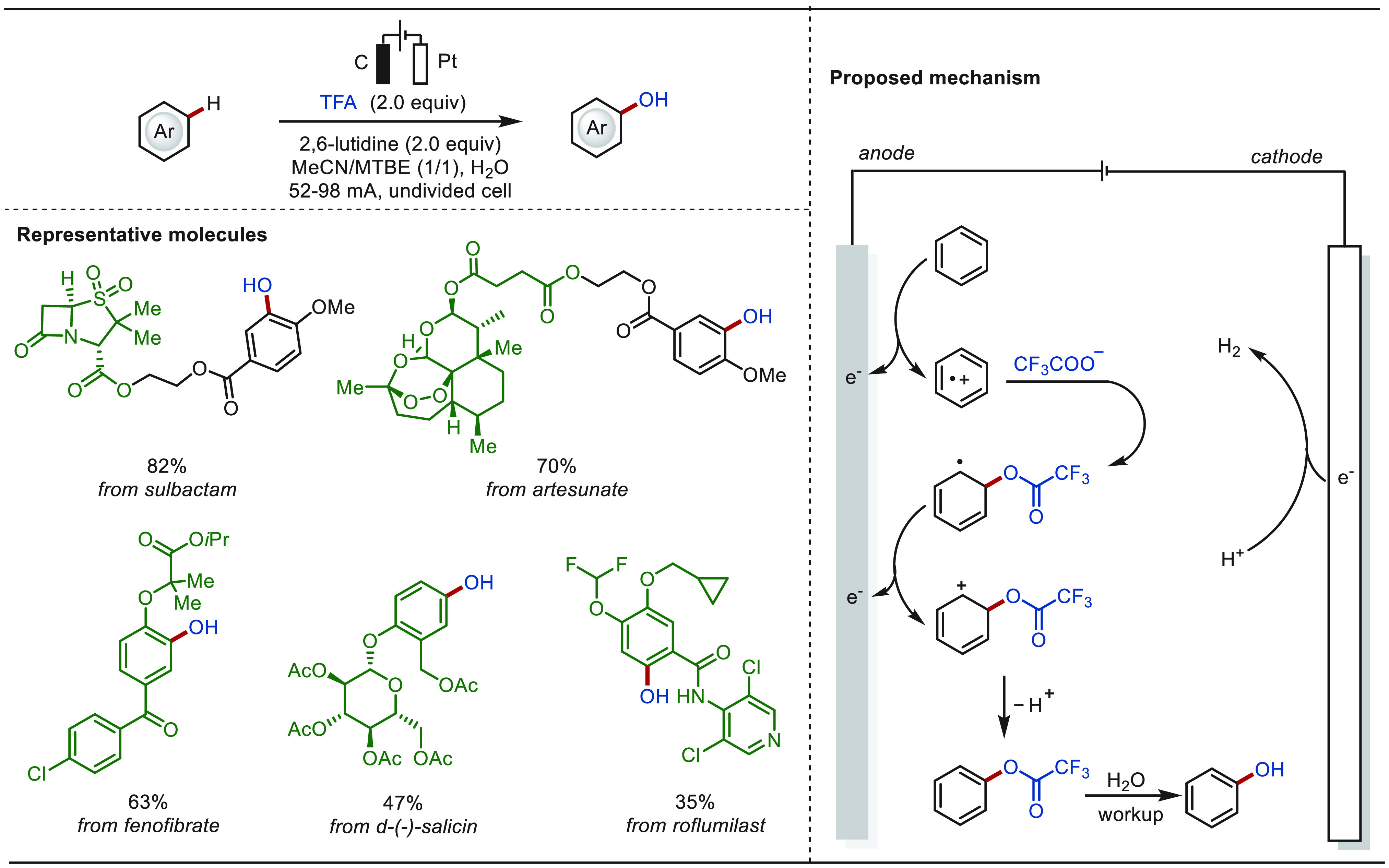

The direct hydroxylation of arene C(sp2)–H bonds is a highly sought-after transformation in the field of LSF, since the introduction of a small −OH group can dramatically improve inter alia the water solubility of the drug molecules.38 However, the controlled electrochemical hydroxylation of the aromatic C–H bond is challenging to achieve given the high propensity of the phenol to undergo overoxidation. To attenuate the overoxidation issue, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was taken into consideration as the oxygen donor to first generate aryl trifluoroacetate intermediates, followed by hydrolysis to release the hydroxylated products.146,147 Although this approach seems promising, the viable methods are limited to a few examples of structurally simple and electron-deficient/neutral arenes. Electron-rich arenes still typically suffer from overoxidation and self-coupling side reactions, and hence cannot efficiently converted to phenols.148

Continuous-flow electrochemical microreactors have the potential to increase the reaction efficiency and reducing overoxidation.149−155 In this context, the Xu group elegantly realized electrochemical C(sp2)–H hydroxylation of diverse arenes with high efficiency and selectivity in a continuous flow electrochemical microreactor (Scheme 7).156 The approach proceeded under mild conditions without chemical oxidants or transition-metal catalysts, featuring a broad scope of arenes with diverse electronic properties. The overoxidation reaction was greatly inhibited. The eLSF of a number of natural products and drug derivatives was achieved in an efficient and selective manner.

Scheme 7. Electrochemical Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Hydroxylation.

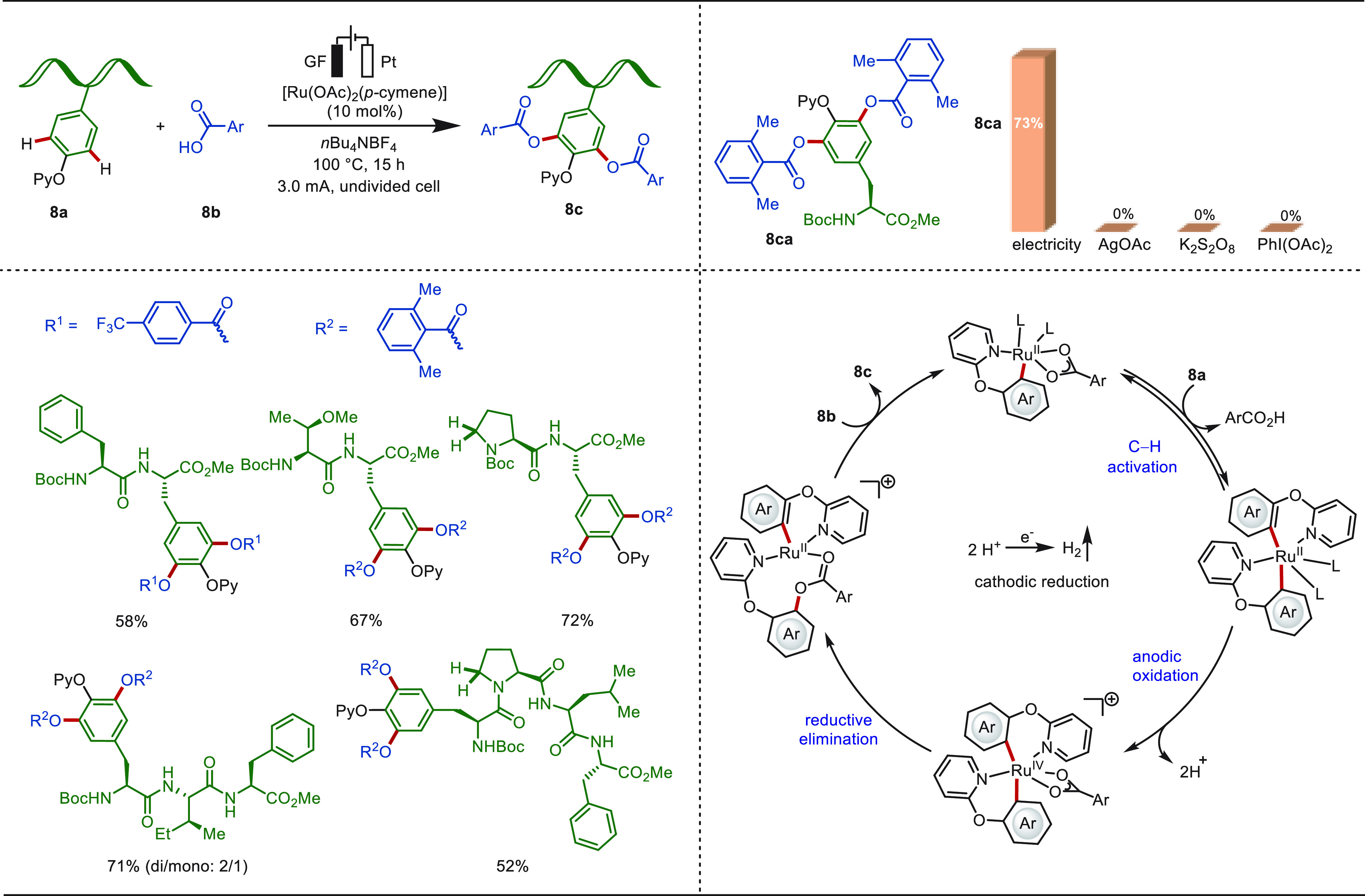

Besides the direct electrolysis method, the merger of electrocatalysis with organometallic C–H activation provides another sustainable strategy for the oxygenation of the aromatic C(sp2)–H bond.157−162 The Ackermann group has previously reported rhodaelectro- and ruthenaelectro-catalyzed hydroxylations of diverse arenes with TFA.159,161 Very recently, the same group achieved the ruthenaelectro-catalyzed late-stage C(sp2)–H acyloxylation of tyrosine-containing peptides with various aromatic acids (Scheme 8).162 Notably, attempted transformations with chemical oxidants, including AgOAc, K2S2O8, and PhI(OAc)2, proved to be ineffective — a strong testament to the robust nature of the electrochemical approach. A variety of di-, tri-, and tetrapeptides were efficiently acyloxylated without epimerization of the otherwise sensitive peptides. Remarkably, this electro-oxidative regime bypassed Shono-type manifolds even when employing proline-containing peptides. Mechanistic studies indicated that p-cymene dissociated during the catalytic cycle and the catalyst underwent a ruthenium II/IV regime likely involving a bis-cyclometalated complex intermediate.

Scheme 8. Electrochemical Late-Stage C–H Acyloxylation of Tyrosine-Containing Peptides.

Reproduced with permission from ref (162). Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry.

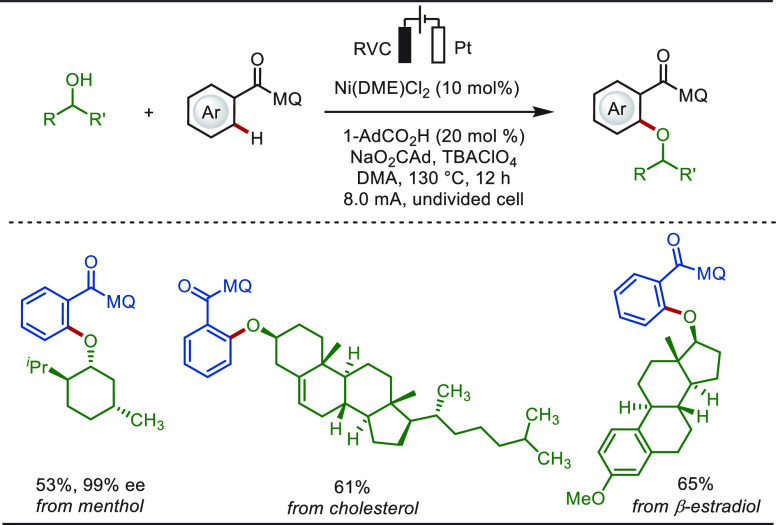

In 2019, Ackermann reported a rare example of electro-oxidative nickel-catalyzed C(sp2)–H alkoxylation reaction with secondary alcohols (Scheme 9).158 This metallaelectrocatalysis exhibited high chemo- and positional-selectivity, and the plausible mechanism of this transformation involves a nickel(IV)-intermediate. Notably, various naturally occurring alcohols, such as menthol, cholesterol, and β-estradiol, were accommodated as coupling partners, delivering the corresponding aromatic ethers in excellent yields.

Scheme 9. Electro-oxidative C–H Alkoxylation of Arenes with Secondary Alcohols.

2.1.3. Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Amination

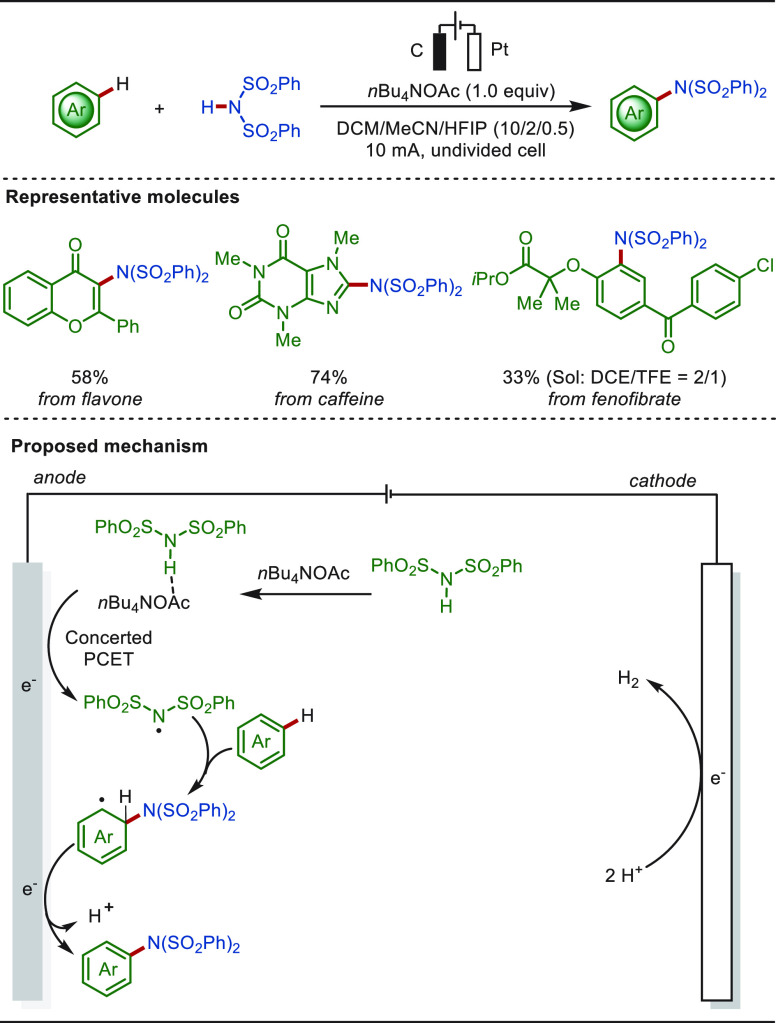

The electro-oxidative C–H/N–H cross-coupling is a straightforward and powerful tool to install nitrogen functionalities into aromatic compounds. In 2019, the Lei group reported an intermolecular cross-coupling between sulfonimides and aromatic arenes (Scheme 10).163 The transformation proceeded through a nitrogen-centered radical addition pathway under transition-metal-free and exogenous oxidant-free conditions. A variety of arenes, alkenes, heteroarenes, and pharmaceuticals, such as flavone, caffeine, and fenofibrate, were amenable scaffolds. Aryl sulfonamides or aniline derivatives could thus be obtained after the deprotection process. Mechanistic studies indicated that the nitrogen-centered radicals were generated via a proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) process jointly mediated by nBu4NOAc and an anodic oxidation process.163,164 Concurrently, the Ackermann group achieved an electrochemical oxidation induced C(sp2)–H nitrogenation for a variety of heteroarenes, including pyrroles, indoles, benzothiophene, and benzofuran.165 In addition, metallaelectro-catalyzed C(sp2)–H aminations have been realized with diverse transition-metal catalysts (Ni, Co, Cu, etc.).166−169

Scheme 10. Electrochemical Late-Stage Aminations.

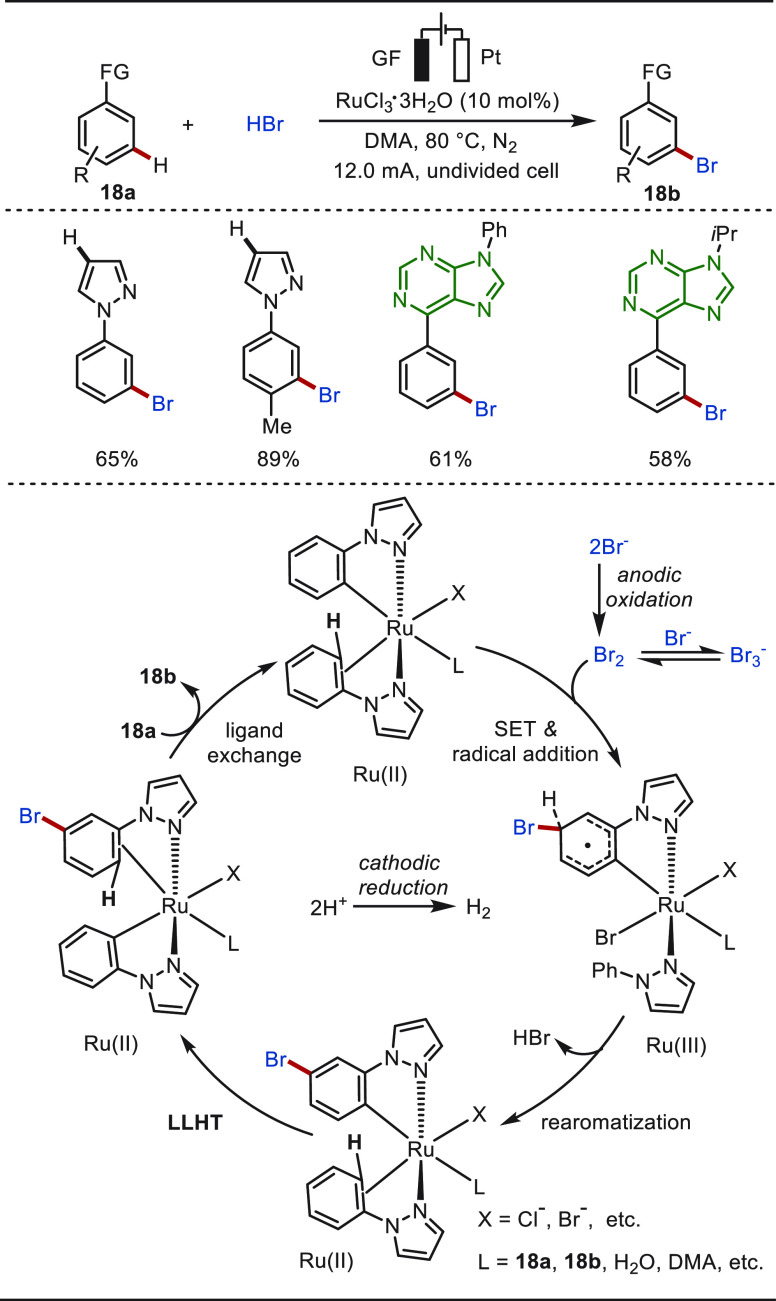

Introducing a functional group into a peptide or a protein under mild, user-friendly conditions is of great significance in the field of chemical biology, medical chemistry, and pharmacology.170−173 In this context, the post modification of the phenolic tyrosine side chain has become the most commonly used strategy due to its relatively high reactivity and low abundance in the proteome (2.9%). Thus, early in the 1990s, Walton and Heptinstall had reported on the modification of hen egg-white lysozyme proteins and horse heart myoglobin via electro-oxidative nitration in a mildly acidic buffer (Scheme 11).174−178

Scheme 11. Electrochemical Late-Stage Nitrogenation.

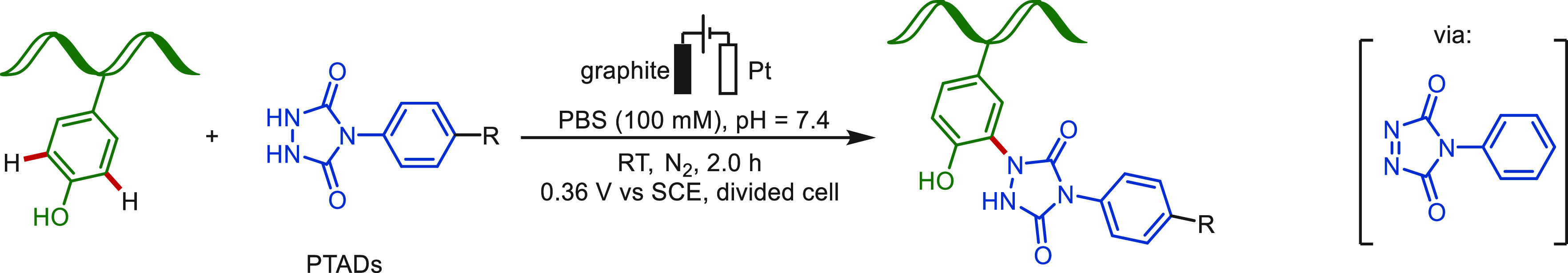

The development of efficient methods for the conjugation of native proteins is relevant for chemical biology and biotherapies, among others. In 2010, Barbas disclosed an ene-like reaction between the tyrosine residues and substituted phenyl-3H-1,2,4-triazole-3,5(4H)-diones (PTADs).179 Bulk chemical oxidant and cosolvents or scavengers (e.g., Tris) needed to be employed, which limited its application scope. In 2018, Gouin and co-workers discovered the electrochemical Y-click reaction at a mild oxidative potential (+0.36 V, constant voltage electrolysis) in an aqueous buffer (Scheme 12).73 At the low potential conditions, the in situ generated reactive species is immediately conjugated with tyrosine, hence minimizing undesired side reactions and leading to a higher selectivity. The utility of this protocol was highlighted by the functionalization of a remarkably broad range of substrates. Both the small peptide hormone oxytocin and epratuzumab, a 152 kDa monoclonal antibody, were selectively modified by this method. In addition, Huan and Li recently employed this strategy to cross-link peptides and proteins at tyrosine residues without the use of photoirradiation or a metal catalyst.180

Scheme 12. Electrochemical Peptide and Protein Modification at Tyrosine.

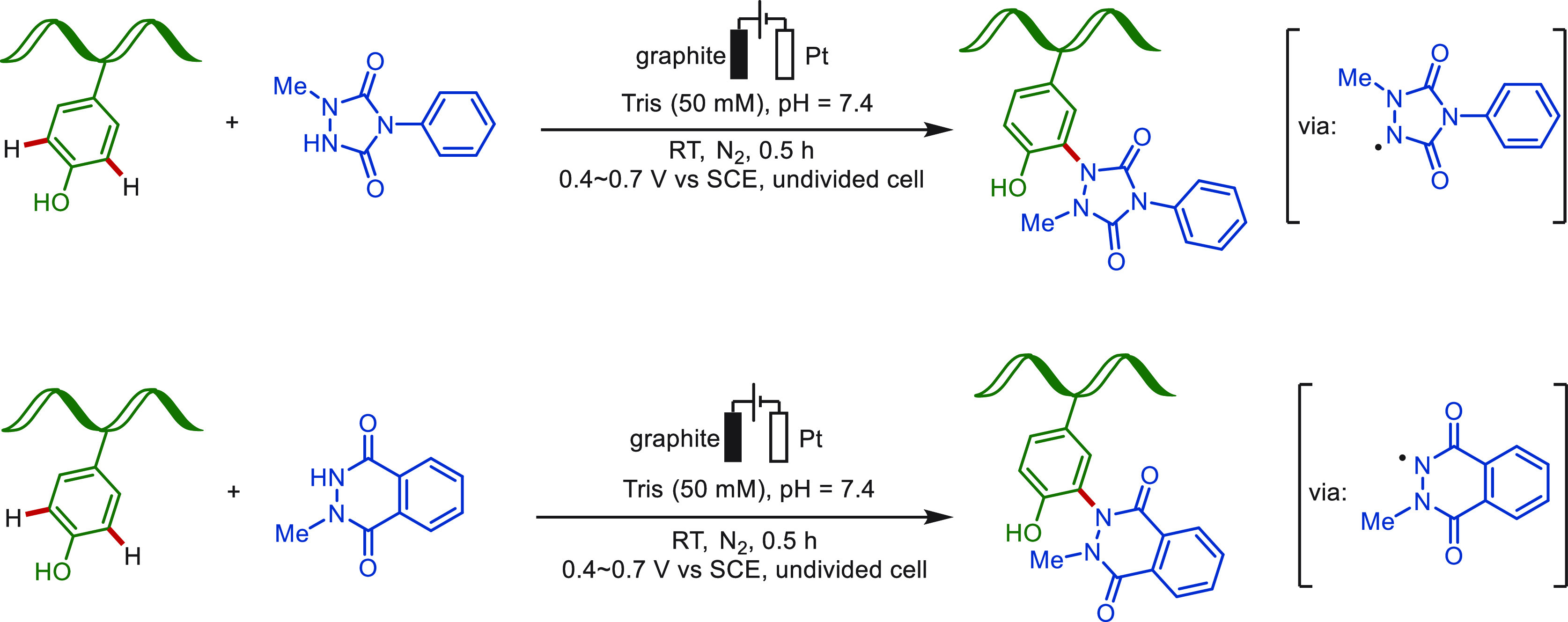

In 2020, Nakamura and co-workers likewise devised a modified version of the e-Y-click reaction for selective bioconjugation at tyrosine residues (Scheme 13).181 In their studies, N-methyl luminol and 1-methyl-4-phenylurazole derivatives were used as active small-molecules, which easily converted to the corresponding nitrogen radical species via the SET process under electro-oxidative conditions. A protected model octapeptide angiotensin II was successfully modified at the native tyrosine residue in a biological fashion. This approach employed purely aqueous buffer (Tris, 50 mM), neutral pH (7.4), and mild electrochemical conditions (400–700 mV), representing a truly biocompatible electrochemical modification strategies.

Scheme 13. Selective Peptide Modification at Tyrosine Using N-Methyl Luminol and 1-Methyl-4-Phenylurazole.

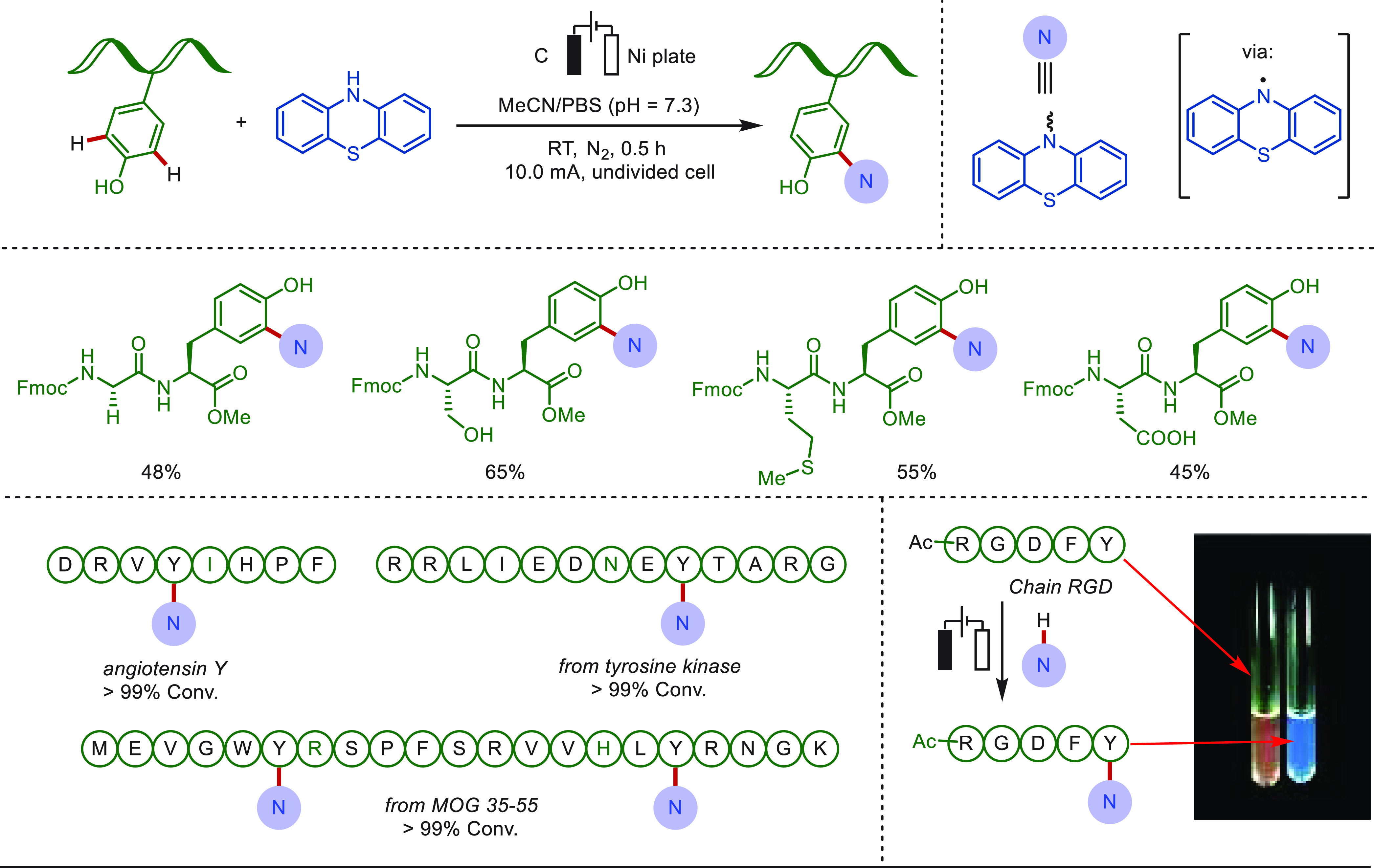

In contrast, the Lei group described an electrochemical method to execute the bioconjugation of a tyrosine side chain with phenothiazine derivatives in a simple and rapid manner (Scheme 14).182 This approach provided direct and efficient access to LSF of oligopeptides and proteins, featuring high chemo- and site-selectivity, without the use of transition-metal or chemical oxidants. Valuable bioactive compounds, such as angiotensin Y, tyrosine protein kinases, and MOG 35-55, selectively underwent the electro-oxidative bioconjugation process. It was also demonstrated that the phenothiazine-labeled peptide could be utilized as a fluorophore.

Scheme 14. Electrochemical Late-Stage C–H Nitrogenation of Tyrosine-Containing Peptides.

Reproduced with permission from ref (182). Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry.

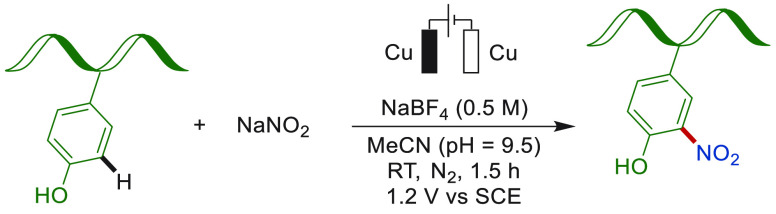

2.1.4. Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Phosphorylation

The development of efficient late-stage phosphorylation methods is of considerable importance, given that organophosphorus compounds have wide utilities in medicinal chemistry.183 The past few years have seen significant development of electrochemical phosphorylation methodologies.184−191 In 2019, Budnikova and co-workers realized the metallaelectro-catalyzed coupling reactions of caffeine with dialkylphosphites (Scheme 15).185 Interestingly, diverse transition metals, including Pd(OAc)2, AgOAc, and Bipy3Ni(BF4)2 proved to be efficient for these transformations, affording the phosphorylated caffeine in good yields of 62–80%.

Scheme 15. Electrocatalytic Coupling Reactions of Caffeine with Dialkylphosphites.

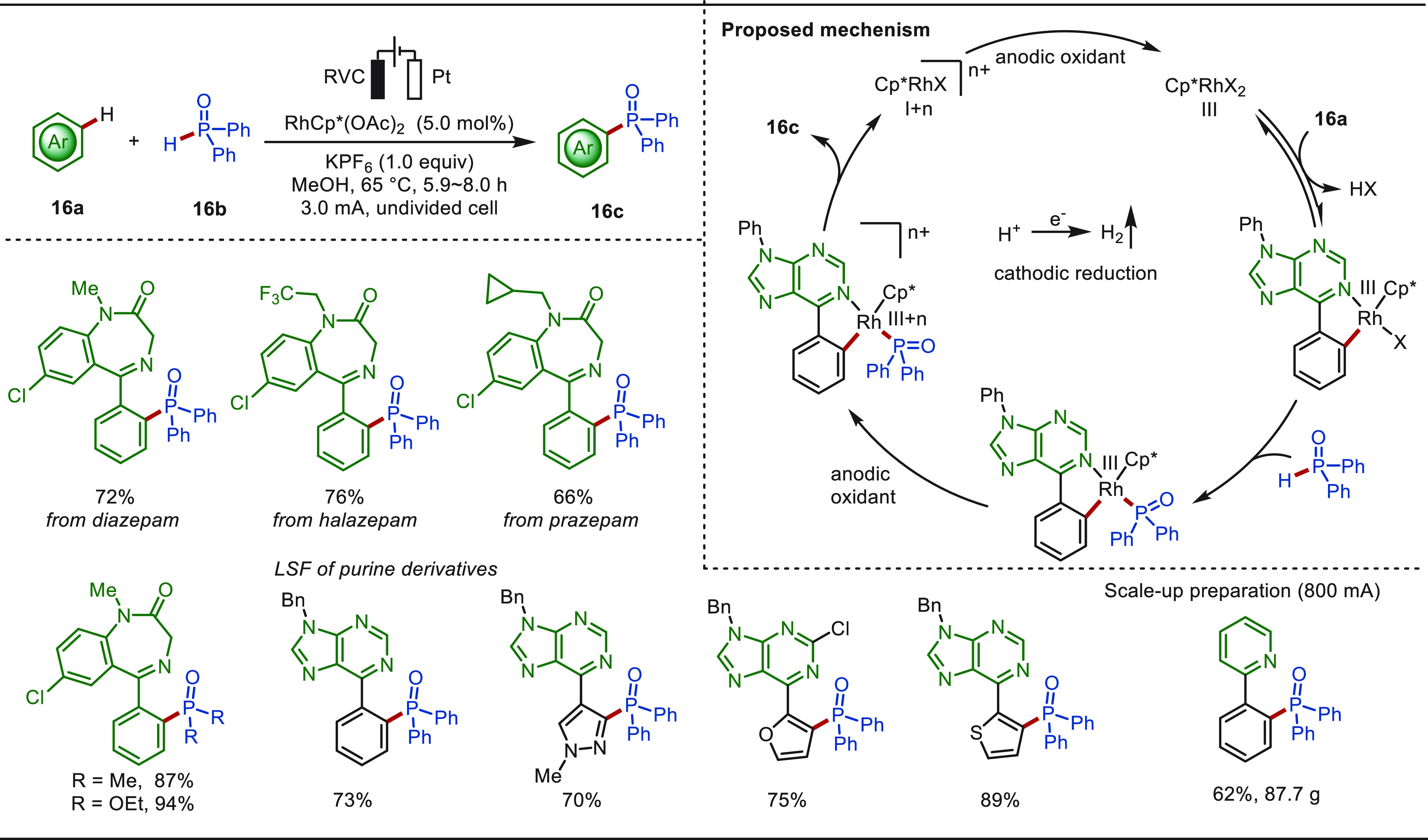

In the same year, Xu and co-workers reported an rhodaelectro-catalyzed late-stage aryl C(sp2)–H phosphorylation reaction with various phosphine oxides (Scheme 16).186 The electrochemical approach was characterized by a broad scope and high functional group tolerance without using exogenous chemical oxidants. The method proved to be compatible with the eLSF of a variety of bioactive molecules such as diazepam and purine derivatives. Notably, this electrochemical reaction was also easily scaled up, remarkably yielding a phosphonate product in 87.7 g. Mechanistic interrogation suggested that the C–P bond was formed via an oxidation-induced reductive elimination process.

Scheme 16. Electrochemical Rhodium-Catalyzed C(sp2)–H Phosphorylation.

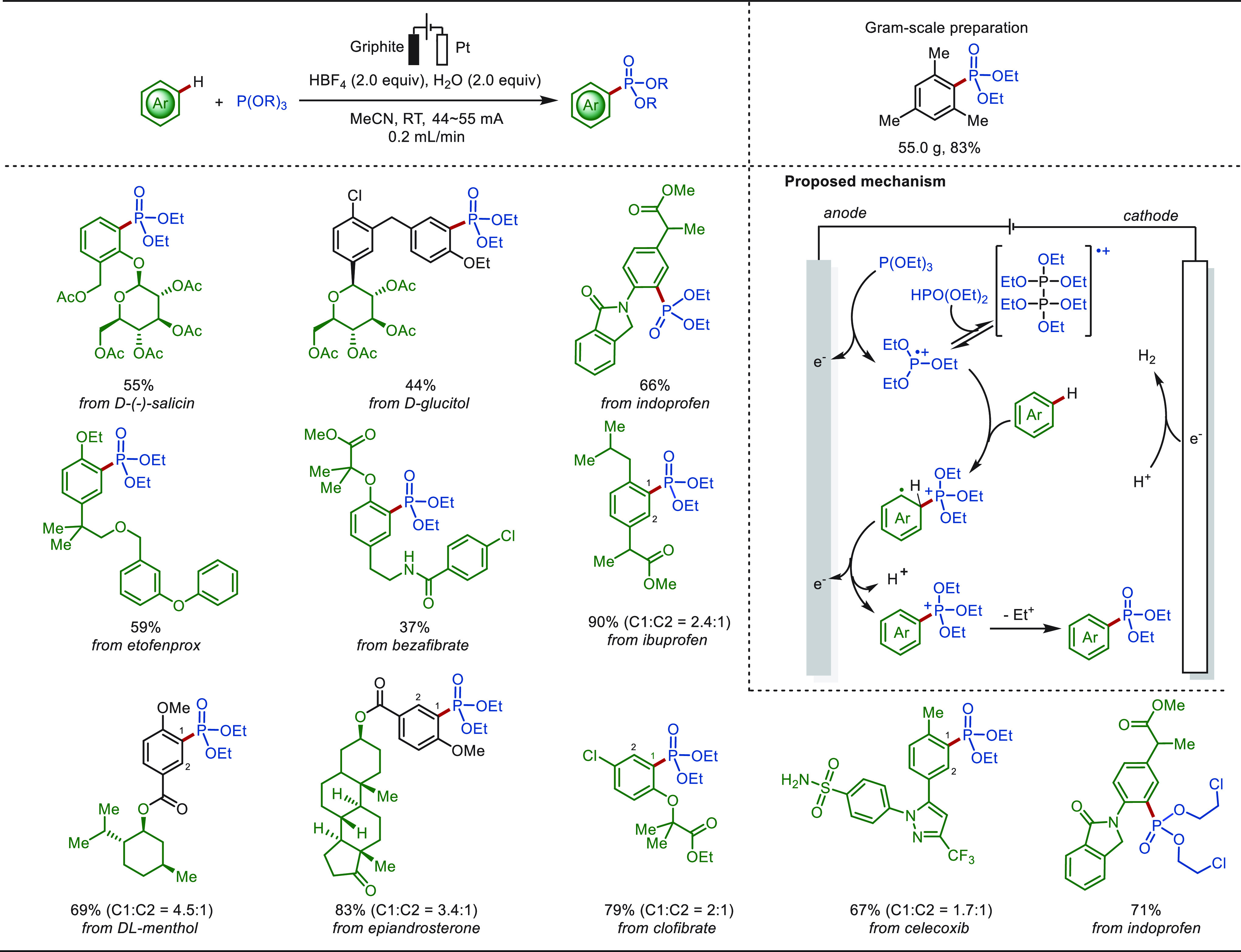

In 2021, the Xu group furthermore disclosed an electrochemical aromatic C(sp2)–H phosphorylation reaction using triethyl phosphite P(OR)3 in a continuous flow cell, obviating the use of exogenous chemical oxidants and transition-metal catalysts (Scheme 17).187 This continuous flow electrosynthesis was found to be compatible with both electron-rich and electron-deficient arenes. The practical utility of this electrochemical phosphorylation was further illustrated by the continuous production of one phosphonate product in 55.0 g. The C–P bond was formed through the reaction of arenes with in situ anodically generated P-radical cations. The selective late-stage functionalization of a series of bioactive compounds and natural products was accomplished through continuous flow electrosynthesis.

Scheme 17. Electrochemical Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Phosphorylation in Continuous Flow.

2.1.5. Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Halogenation

The incorporation of a halide atom into drug molecules may have a profound effect on enhancing their biological properties.192 In addition, halogenated arenes, particularly aryl bromides, can be quickly converted to radio-labeled compounds, showing great utilities in metabolism studies.193 Moreover, halogenated arenes and heterocycles are versatile intermediates in diverse organic transformations.194 Therefore, the development of efficient and atom-economical halogenation methodologies under mild conditions has been a long-term goal in molecular synthesis. Traditionally, strong corrosive, oxidizing reagents (X2, NXS) or halides (X−) combined with external strong chemical oxidants were needed for halogenation of arenes.195 In contrast, electrochemistry offers a powerful alternative for various halogenation reactions with simple halides salts or an aqueous HX solution as the halogenating source.196−203

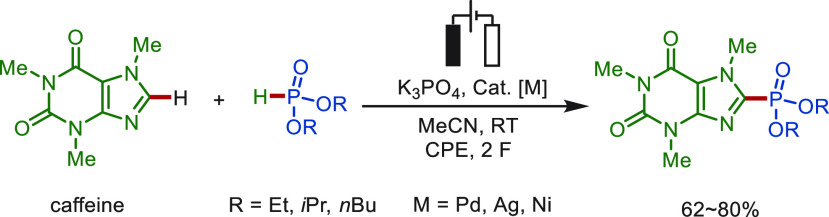

Recently, Ackermann and co-workers disclosed electrochemical ruthenium-catalyzed distal C(sp2)–H bromination with an aqueous HBr solution as the brominating agent (Scheme 18).199 The regioselective meta-C–H bromination was conducted in an undivided cell by the catalysis of RuCl3·XH2O, under external ligand- and electrolyte-free conditions, featuring an ample substrate scope. Particularly, phenylpyrazole was readily brominated at the meta-position on the benzenoid moiety rather than at the commonly functionalized electron-rich pyrazole ring. Thus, and in sharp contrast, the bromination of pyrazolylarene under reported ruthenium/NBS conditions204 or electrochemical metal-free200 conditions proved to occur on the electron-rich pyrazole rings via a simple SEAr process. Purine derivatives were identified as suitable substrates for the ruthena-electrocatalyzed meta-C–H bromination. Mechanistic studies revealed that the bromide ion Br– was oxidized to molecular Br2, which equilibrated with the tribromide anion Br3– by combining and/or releasing a bromide ion. Then the bromination process occurred between Br2 and the in situ generated cycloruthenated complex. The desired meta-brominated product was released after ligand-to-ligand hydrogen transfer (LLHT) and a ligand exchange process.

Scheme 18. Ruthenaelectro-Catalyzed meta-C–H Bromination with HBr.

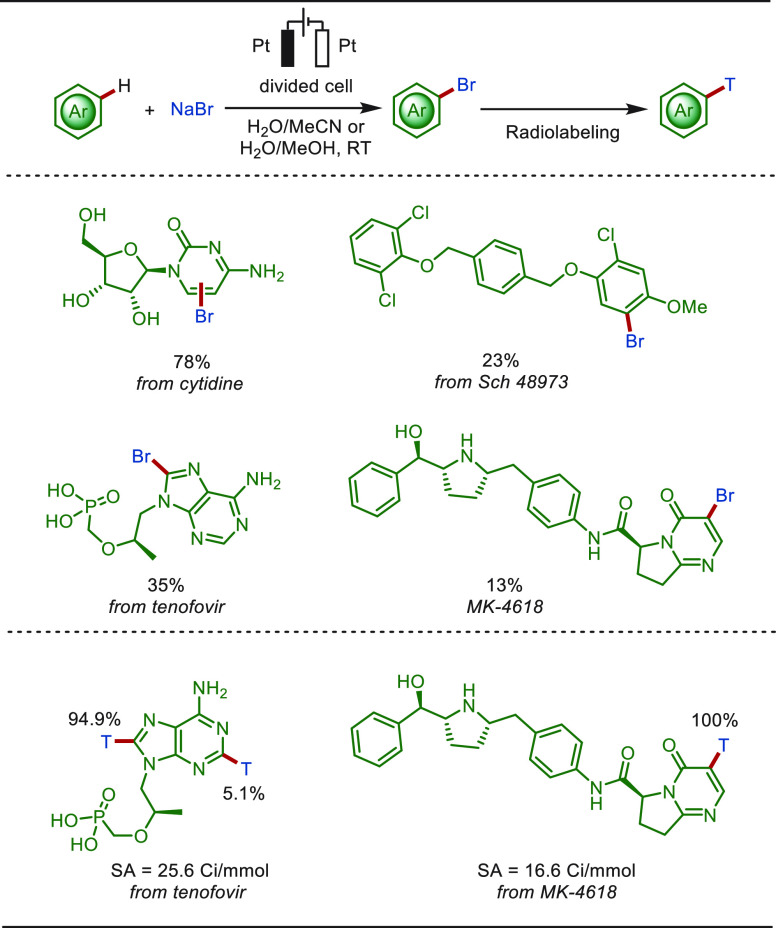

In 2017, Rivera and Liu disclosed an eLSF bromination method using NaBr in a mixture of water with acetonitrile/methanol (Scheme 19).202 The bromination reactions were conducted in a separate microflow electrochemical cell under mild conditions. Electrochemical bromination of drug molecules, including Cytidine, Sch 48793, Tenofovir, and MK-4618, gave rise to the corresponding aryl bromides. The brominated analogues of Tenofovir and MK-4618 were further converted to the corresponding tritium labeled products.

Scheme 19. Electrochemical Late-Stage Bromination of Drug Molecules with NaBr.

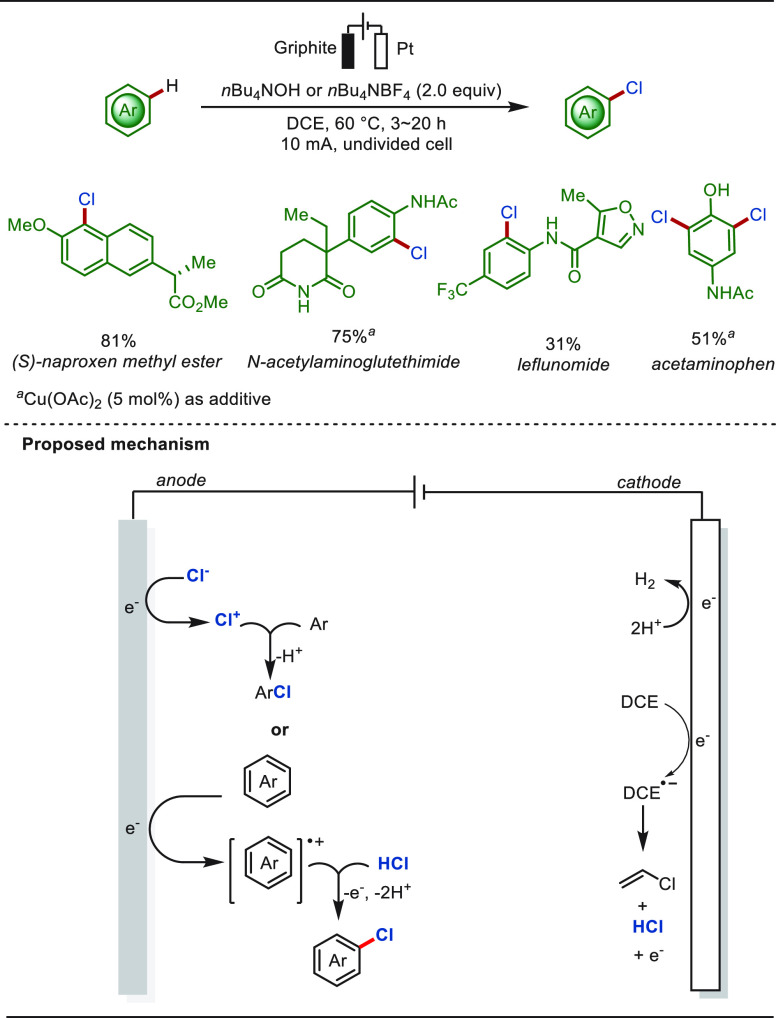

Jiao and co-workers elegantly achieved the electrochemical aromatic chlorination with common solvent DCE as the chloro source, producing vinyl chloride as a useful byproduct (Scheme 20).203 In this work, the electrochemical dehydrochlorination of DCE occurred by controlling the current intensity, producing vinyl chloride and HCl. This method opened a new avenue for the preparation of (hetero)aryl chlorides and vinyl chloride in an environmentally benign manner. The mild nature and practicality of the method was further demonstrated by its easily scaled-up and efficient eLSF chlorination of a number of bioactive molecules, such as (S)-naproxen methyl ester, leflunomide, and acetaminophen. Using a similar strategy, McNeil and co-workers recently realized the chlorination of arenes with waste poly(vinyl chloride) as a chloro source.83

Scheme 20. Paired Electrocatalysis for the Preparation of Aryl Chlorides Using DCE.

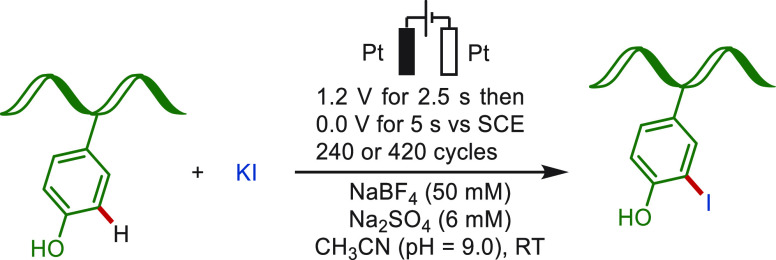

In addition to the electrochemical protein late-stage nitrogenation (vide supra), Heptinstall and co-workers have developed the selective electrochemical iodination of horse heart myoglobin with KI (Scheme 21).205 Since rapid anodic oxidation of an iodide anion led to persistent formation of the undesirable triiodide, the authors used an innovative “redox pulse” method (2.5 s at 0.4 V vs SCE and 5 s at 0.0 V vs SCE, 240 cycles) to enable mono- and double iodination of myoglobin with high levels of selectivity. Notably, this exquisitely controlled protein iodination strategy could proceed at both high and very low iodide concentrations, offering improved selectivity compared to those of reported chemical and enzymatic methods.

Scheme 21. Electrochemical Late-Stage C(sp2)–H Iodination of Tyrosine-Containing Protein.

2.1.6. Late-Stage Annulation Reactions via C(sp2)–H Activations

In the past two decades, annulations via C–H bonds activation have revolutionized the art of preparing cyclic compounds.206−208 Particularly, the electrochemical annulations have gained significant recent momentum without the use of sacrificial chemical oxidants, such as Cu(OAc)2 and AgOAc, avoiding the generation of undesired byproducts and increasing the atom economy.209−220 Diverse five-, six-, and seven-membered rings have been efficiently assembled through formal [3 + 2], [4 + 1], [4 + 2], or [5 + 2] cycloadditions. However, only a small part of these tools were exploited for chemo-selective eLSF.

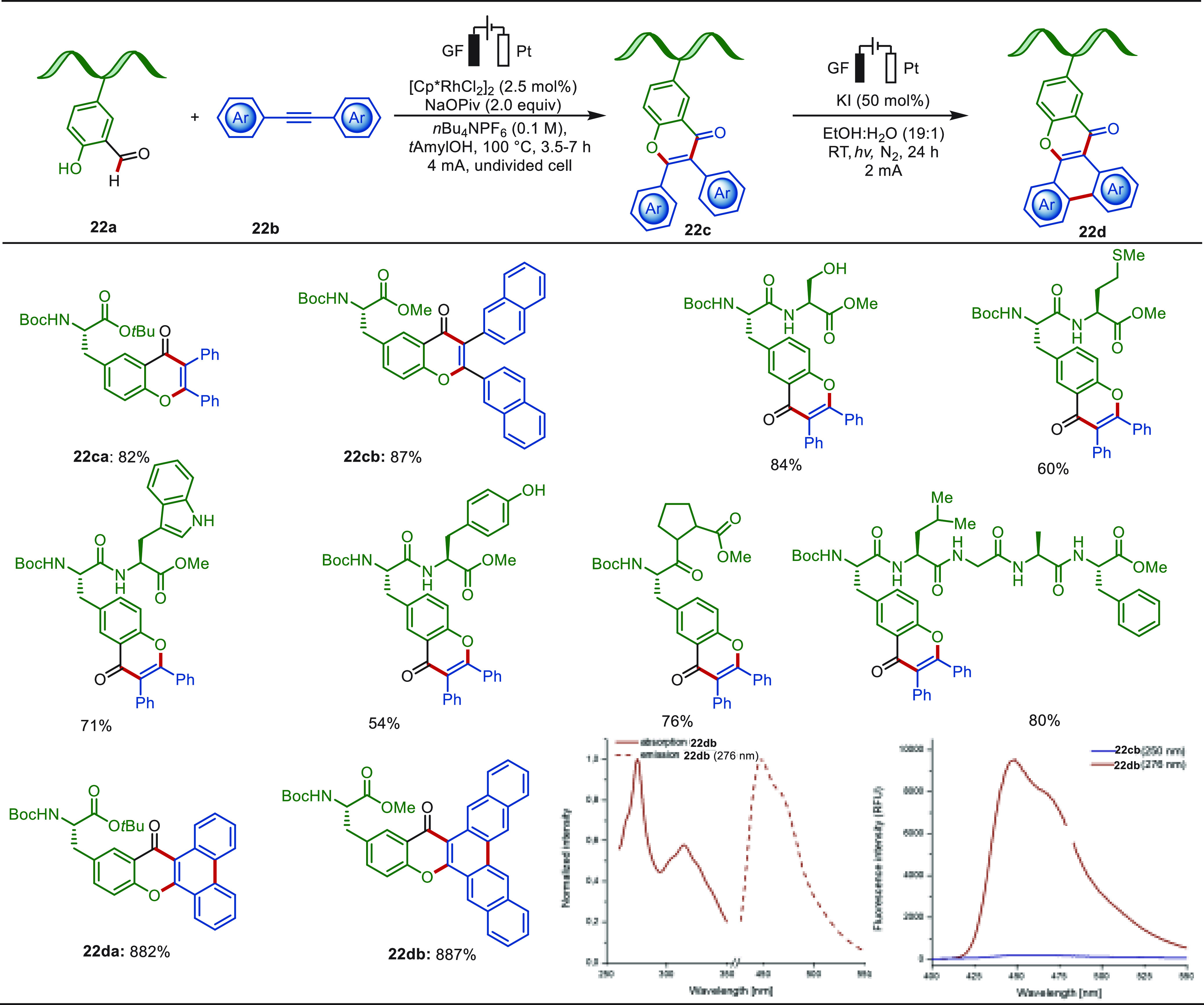

In 2021, the Ackermann group reported on the rhodaelectro-catalyzed annulations of 2-hydroxybenzaldehydes with alkynes by electrochemical formyl C–H activation (Scheme 22).221 The strategy was applicable to the functionalization of tyrosine derivatives and hence enabled access to site-selective electrolabeling of tyrosine-derived fluorescent amino acids and peptides. A broad variety of dipeptides, even including oxidation-sensitive methionine and serine containing peptides as well as polypeptide, were efficiently converted to the desired products. Mechanistic studies provided strong support for an oxidation-induced reductive elimination within a rhodium(III/IV/II) manifold. Notably, a mediated photoelectrochemical oxidation of the modified amino acids allowed for access to π-extended peptide labels, which exhibited intense fluorescence and have great potential as fluorogenic probes.

Scheme 22. Rhodaelectro-Catalyzed Peptide Late-Stage Labeling via Formyl C–H Activation.

Reproduced with permission from ref (221). Copyright 2021, Springer Nature.

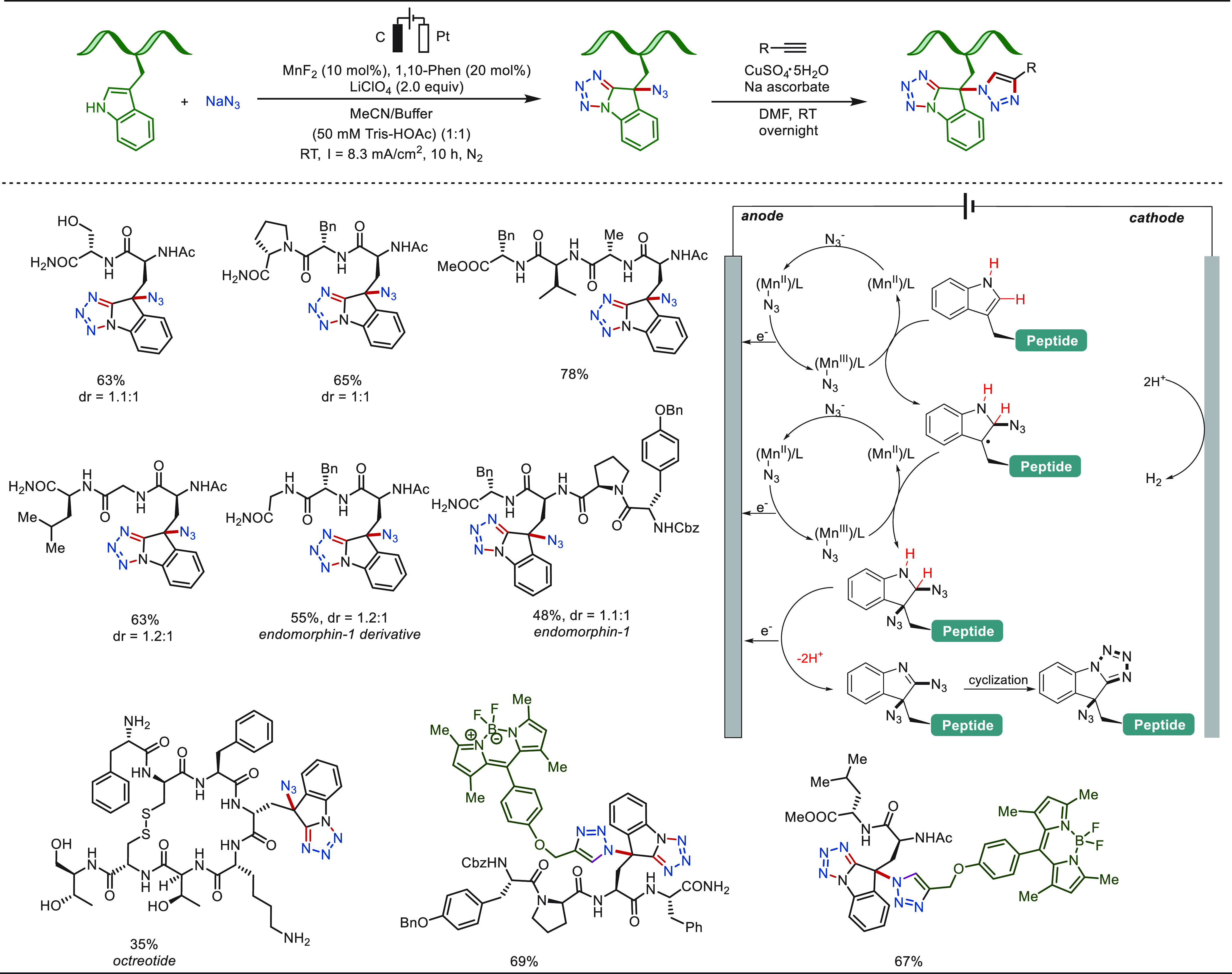

Very recently, Weng and co-workers developed an electrochemical LSF of tryptophan-containing peptides with NaN3 to afford azide-substituted tetrazolo[1,5-α]indolecontaining peptides (Scheme 23).222 This reaction used an earth abundant Mn catalyst under mild buffered conditions. This strategy was applicable for a wide range of peptides with good functional-group tolerance and high site-selectivity. In addition, the thus-obtained Trp-containing peptides with an azide group could be further derivatized to various triazole products by a copper-catalyzed “click” reaction. The reaction was proposed to proceed through manganese-mediated diazidation of the indole unit, followed by the dehydrogenation and heterocyclization to deliver the LSF products.

Scheme 23. Tandem Electrochemical Oxidative Azidation/Heterocyclization of Tryptophan-Containing Peptides.

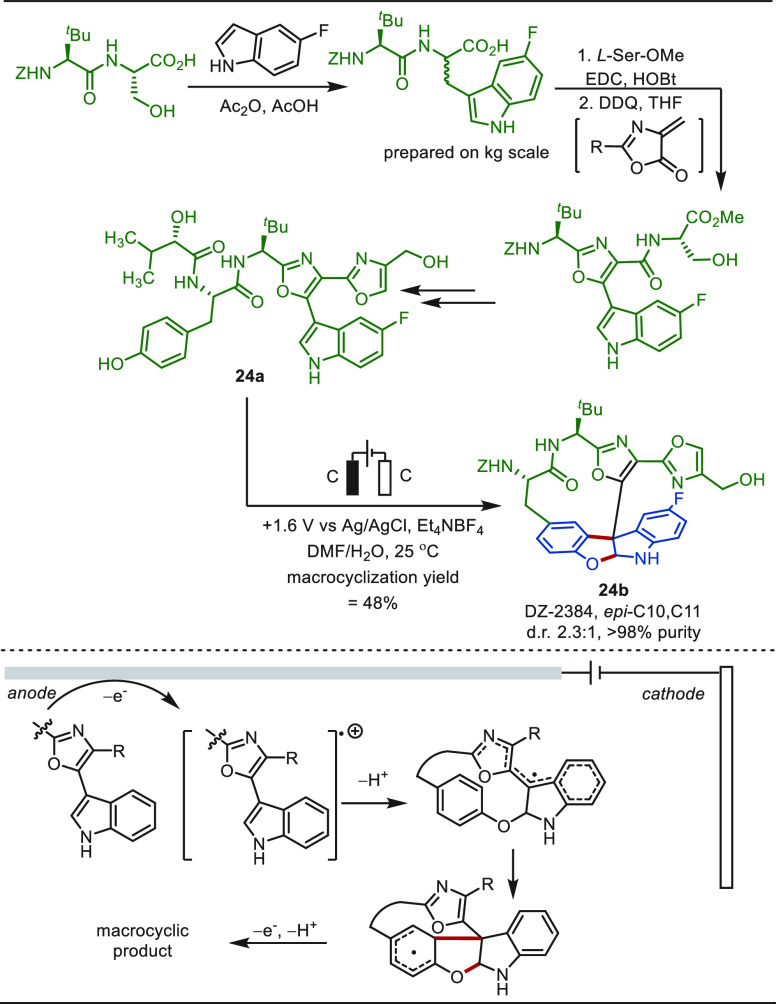

The synthesis of macrocycles—abundant motifs in biologically relevant molecules and pharmaceuticals—continues to represent a popular arena for synthesis chemists.223−227 However, the construction of large ring systems is challenging, considering geometrical and thermodynamic constraints. Recently, electrochemical transformations have emerged as useful techniques in this regard. In 2015, Harran uncovered an electro-oxidative late-stage macrocyclization strategy for a scalable synthesis of antimitotic agent DZ-2384 (Scheme 24).228 The synthetic strategy used the dipeptide tert-Leu-5-F-Trp-OH as the precursor for the synthesis. After strategic modification over this dipeptide, advanced intermediate 24a was synthesized, which upon constant potential electrolysis realized an oxidative cyclization on the indole core to construct the DZ-2384 analogue in moderate yields. The oxidative cyclization involved SET oxidation of 24a, which then underwent a nucleophilic attack with the phenolic −OH functionality present in the molecule. Next a 5-exo-trig cyclization with the arene counterpart followed by aromatization generated the DZ-2384.

Scheme 24. Electrochemical Oxidative Macrocyclization for the Synthesis of DZ-2384.

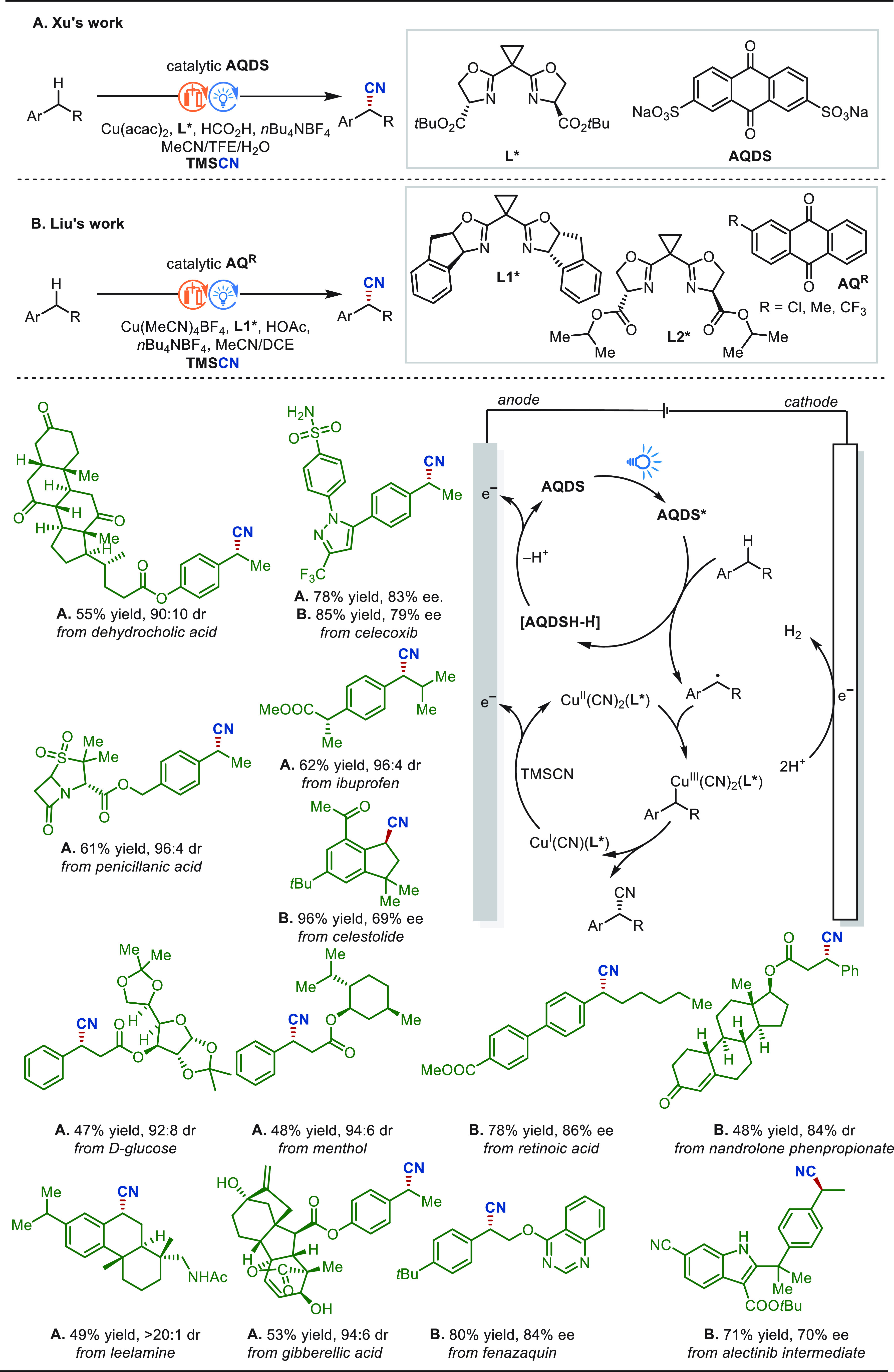

2.2. eLSF of C(sp3)–H Bonds

2.2.1. Late-Stage Benzylic C(sp3)–H Functionalization

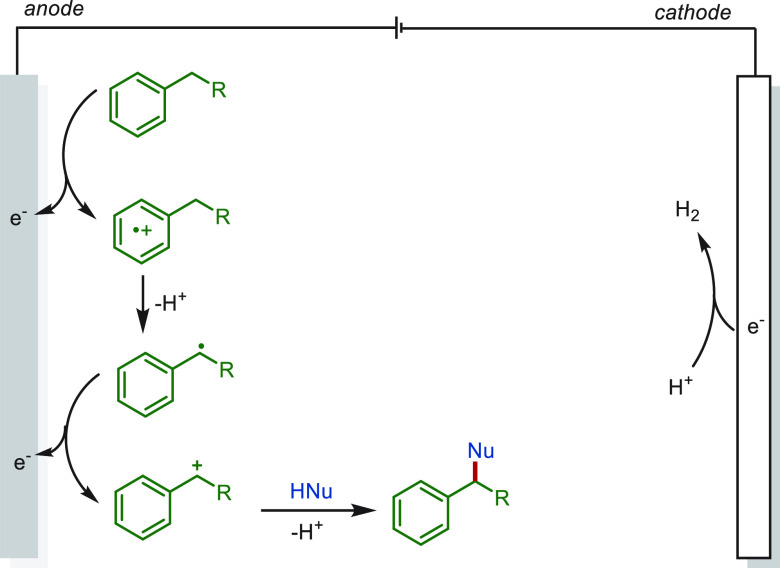

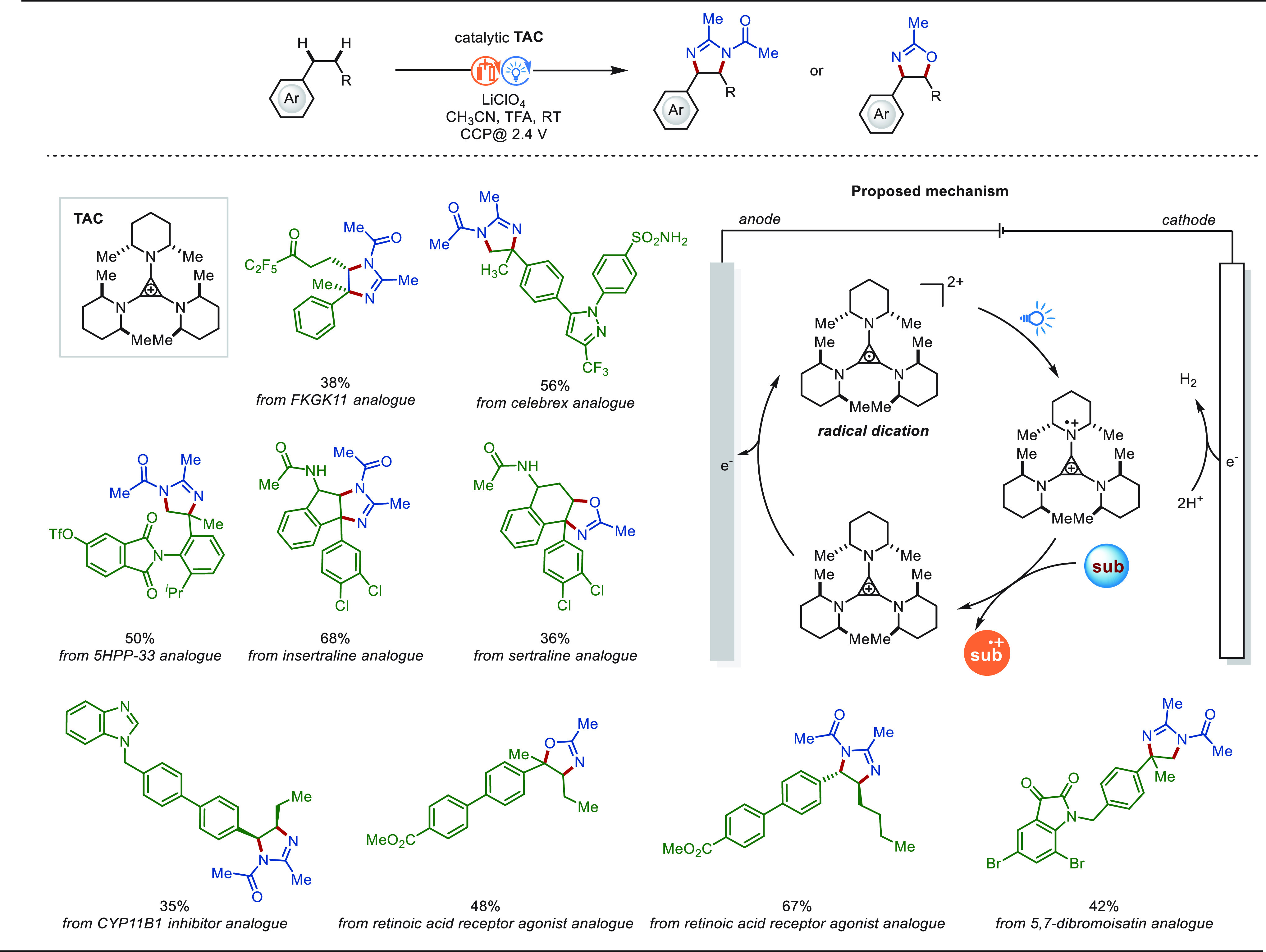

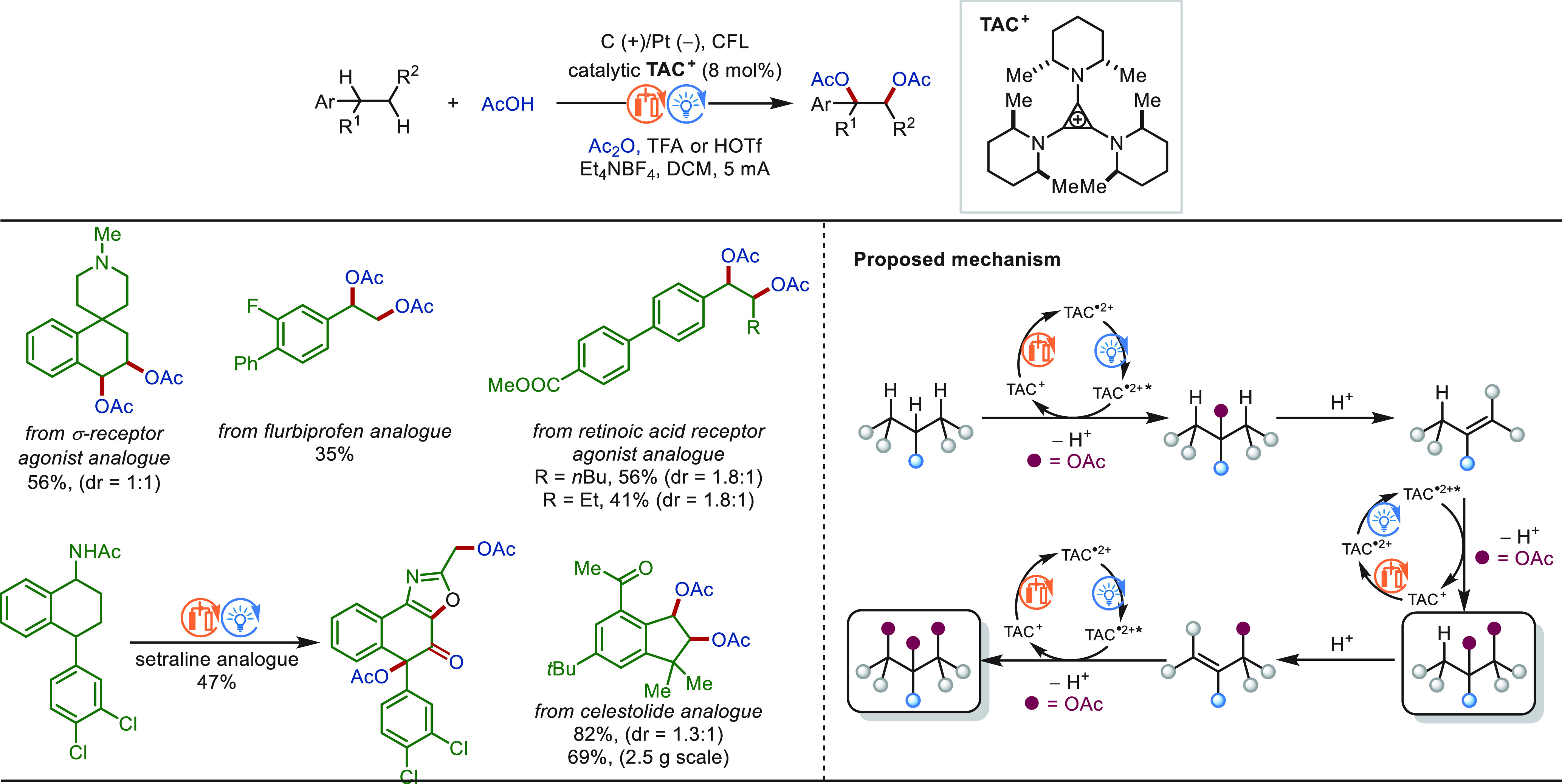

Benzylic C(sp3)–H bonds are ubiquitous in natural products and drug molecules. About 25% of the 200 best-selling drugs contain benzylic C–H bonds. The relatively low bond dissociation energy of benzylic C–H bonds enables high site-selectivity among various types of C–H bonds in structurally complex molecules.229 Therefore, benzylic C(sp3)–H functionalization has wide application foreground in the LSF field and has received a great deal of attention. In this context, significant progress was achieved for electrochemical benzylic C(sp3)–H functionalization.230 The reaction mechanism was proposed as following for most cases: Anodic oxidation of the hydrocarbon substrate gives an arene-centered radical cation, which undergoes rapid proton transfer and a second electron transfer oxidation to form a benzylic cation. Then, the intermediate was trapped by a nucleophilic reagent to afford the final product (Scheme 25). Meanwhile, hydrogen gas is generated at the cathode. Notably, the selection of a suitable solvent generally plays a key role in such transformation to modulate the oxidation potentials of the starting substrate and the product to avoid overoxidation.

Scheme 25. Proposed Mechanism for Electrochemical Benzylic C(sp3)–H Functionalization.

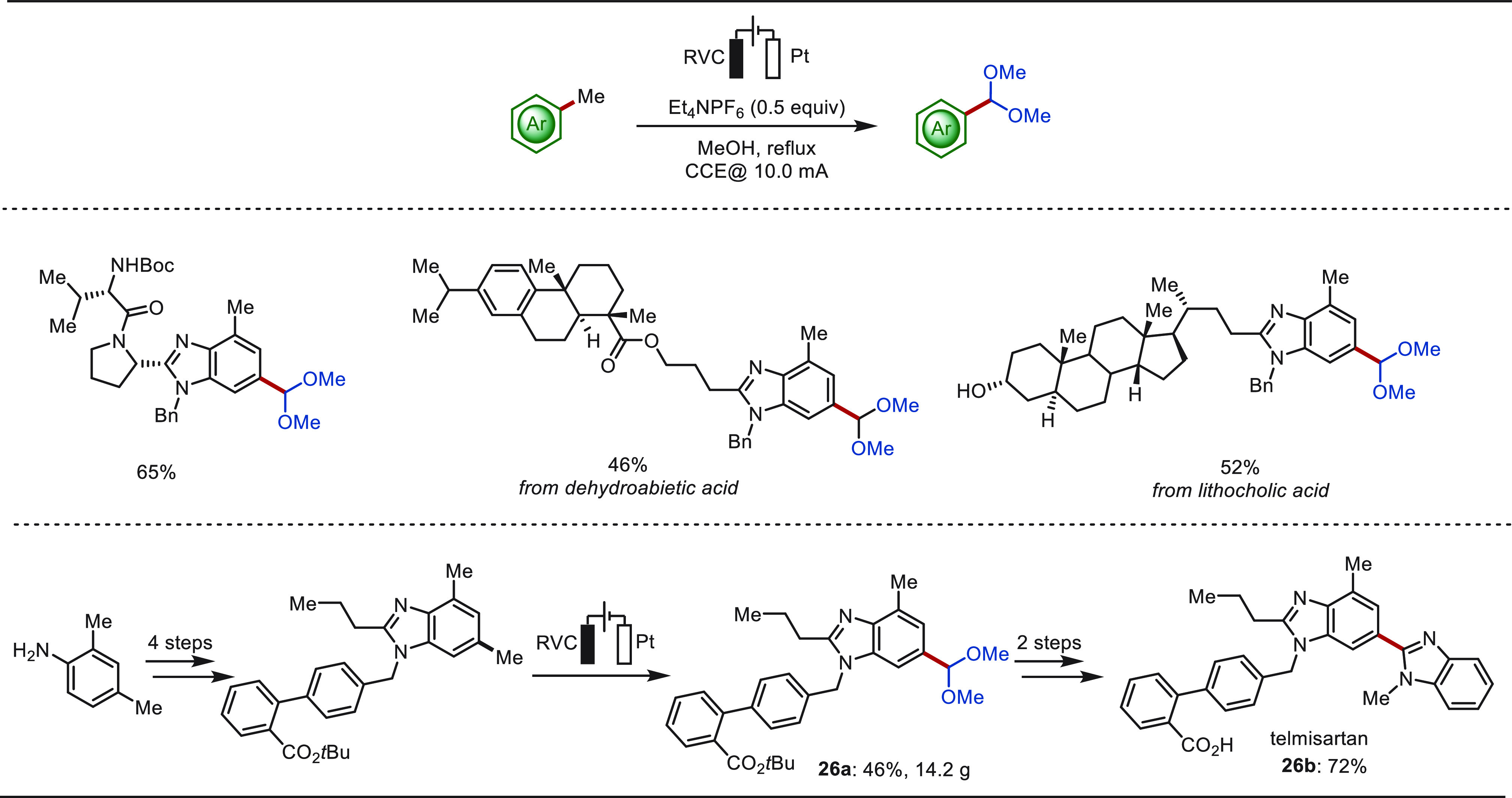

The formyl group is a synthetically versatile functional group that can be converted to a variety of functionalities. The oxygenation of methylarenes to benzaldehyde derivatives is of significant practical interest for LSF as the benzyl methyl motifs are widely present in drug molecules. However, control of chemo-selective oxidation with highly functionalized methylarenes remains a significant challenge due to the product overoxidation and selectivity issues for substrates featuring multiple oxidizable C–H bonds.231,232 Recently, the Xu group disclosed an electrochemical method that can site-selectively oxidize methyl benzoheterocycles to aromatic acetals in an undivided cell setup, without the utility of transition-metal catalysts and exogenous chemical oxidants (Scheme 26).233 The acetals could be easily hydrolyzed to the corresponding aldehydes in one-pot or in a separate step. This electro-oxidation approach was amenable to various functionalized benzoheterocycles and medicinally relevant molecules. The utility of this electro-oxidation reaction was further demonstrated by the efficient construction of the antihypertensive drug telmisartan 26b, in which the key dimethyl acetal intermediate 26a was obtained on a 14.2 g scale by site-selective electro-oxidation reaction.

Scheme 26. Electrochemical Late-Stage Oxidation of Various Methylarenes.

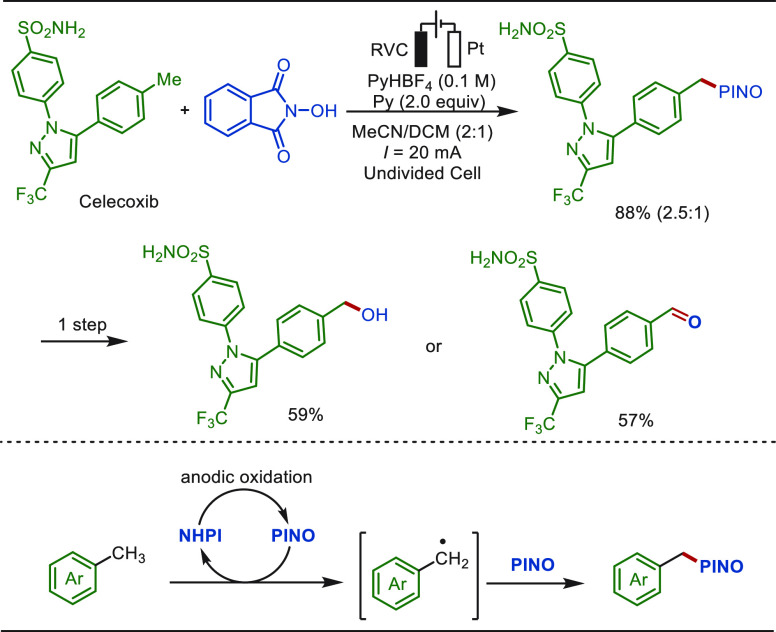

The oxidation of methylarenes is generally ineffective for electron-neutral and electron-deficient arenes since their higher redox potentials lead to poor selectivity or competitive solvent oxidation. A NHPI (N-hydroxypthalimide) mediated electrosynthetic method was developed by Stahl and co-workers to overcome these limitations (Scheme 27).234 In their studies, proton-coupled electrochemical oxidation of NHPI generated the PINO (phthalimide-N-oxyl) radical, which serves as a hydrogen-atom-transfer (HAT) mediator and as a metastable persistent radical to trap the in situ generated benzylic radicals. This PINOylation reaction operated at ∼0.5–1.5 V lower electrode potentials compared with the direct electrolysis methods, and hence enables the mediated electrolysis approach to tolerate a broad scope of methylarenes with diverse electronic properties and ancillary functional groups. The synthetic utility of this method was clearly reflected by facial conversion of the thus-obtained products into benzylic alcohols or aldehydes under photochemical conditions, both of which are compatible with LSF of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory pharmaceutical celecoxib.

Scheme 27. NHPI Mediated Late-Stage Benzylic Oxidation of Methylarenes.

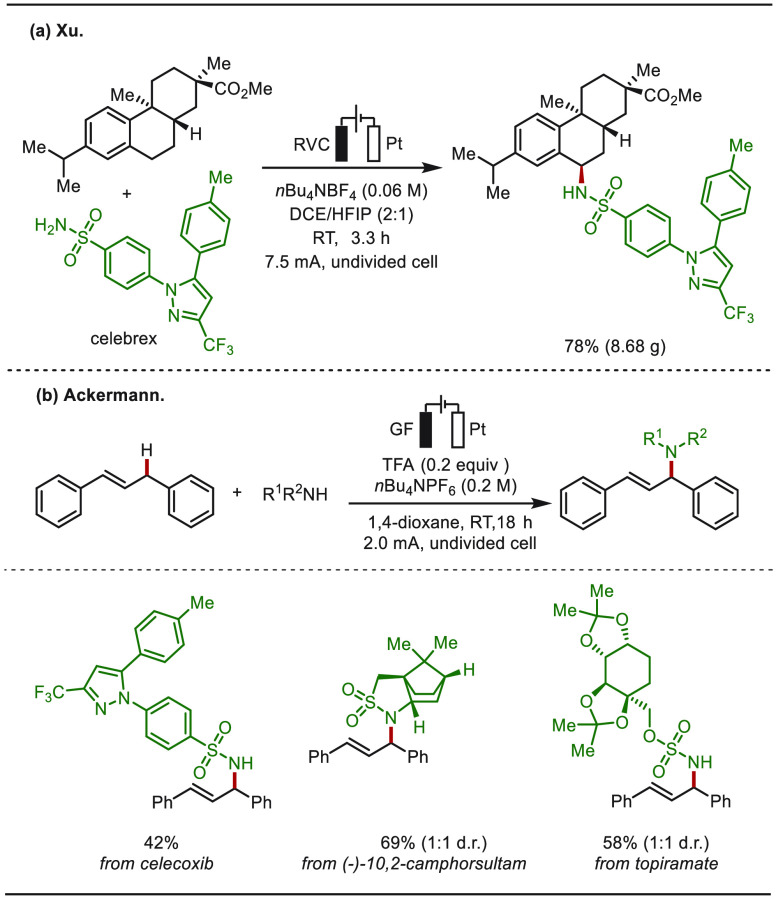

In 2021, Xu and co-workers reported on a site-selective electrochemical benzylic C–H amination via the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) without the need of exogenous oxidants or transition-metal catalysts (Scheme 28a).235 The practical utility of this electrochemical C–H amination reaction was illustrated by a gram-scale preparation with Celebrex as the aminating source, giving the corresponding C(sp3)–N coupling product in 78% yield. Meanwhile, the Ackermann group disclosed an effective method for electrochemical C–H aminations of 1,3-diarylpropenes via direct oxidative C(sp3)–H functionalizations with various substituted amides including the chiral auxiliary (−)-10,2-camphorsultam as well as the sulfonamide drugs Celebrex and Topiramate (Scheme 28b).236

Scheme 28. eLSF by Benzylic C–H Amination.

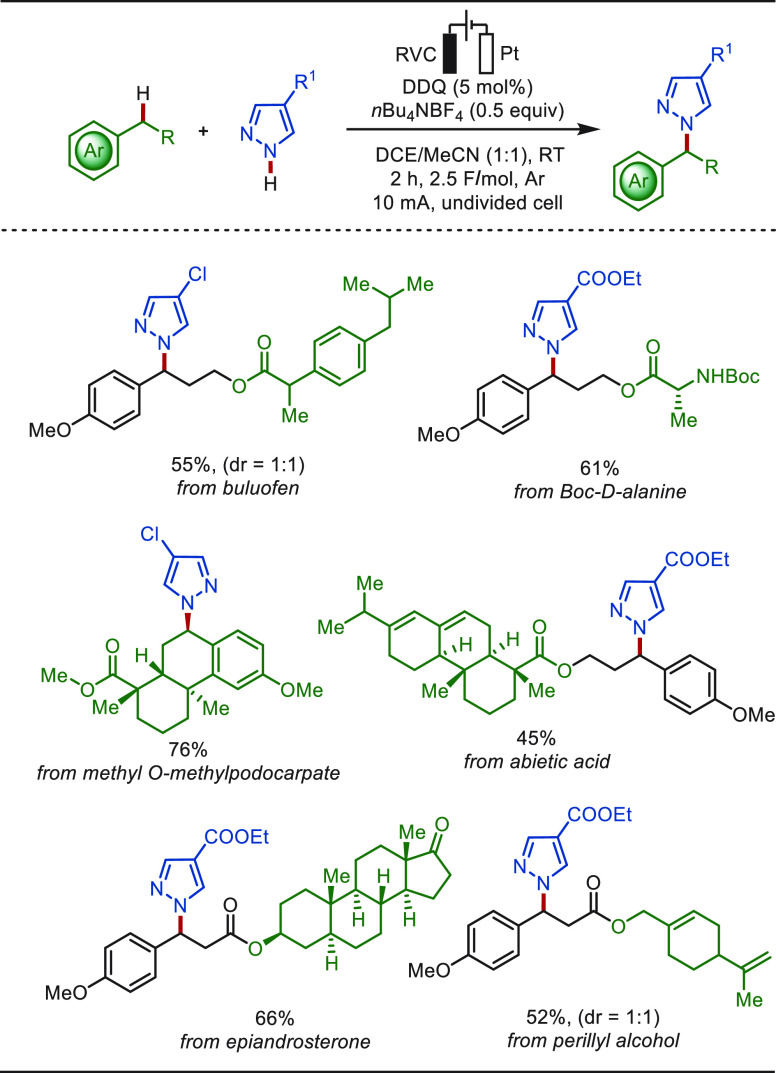

The Wang group also achieved a similar benzylic C–H amination reaction with diverse pyrazoles in a mixture of DCE and MeCN as solvents (Scheme 29).237 DDQ (2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone) was employed as a redox mediator to improve the electrolysis efficiency. The compatibility of this electrochemical strategy was demonstrated by the late-stage aminations of bioactive molecule substrates deriving from buluofen, abietic acid, epiandrosterone, and perillyl alcohol.

Scheme 29. DDQ-Mediated Late-Stage Benzylic C–H Azolation.

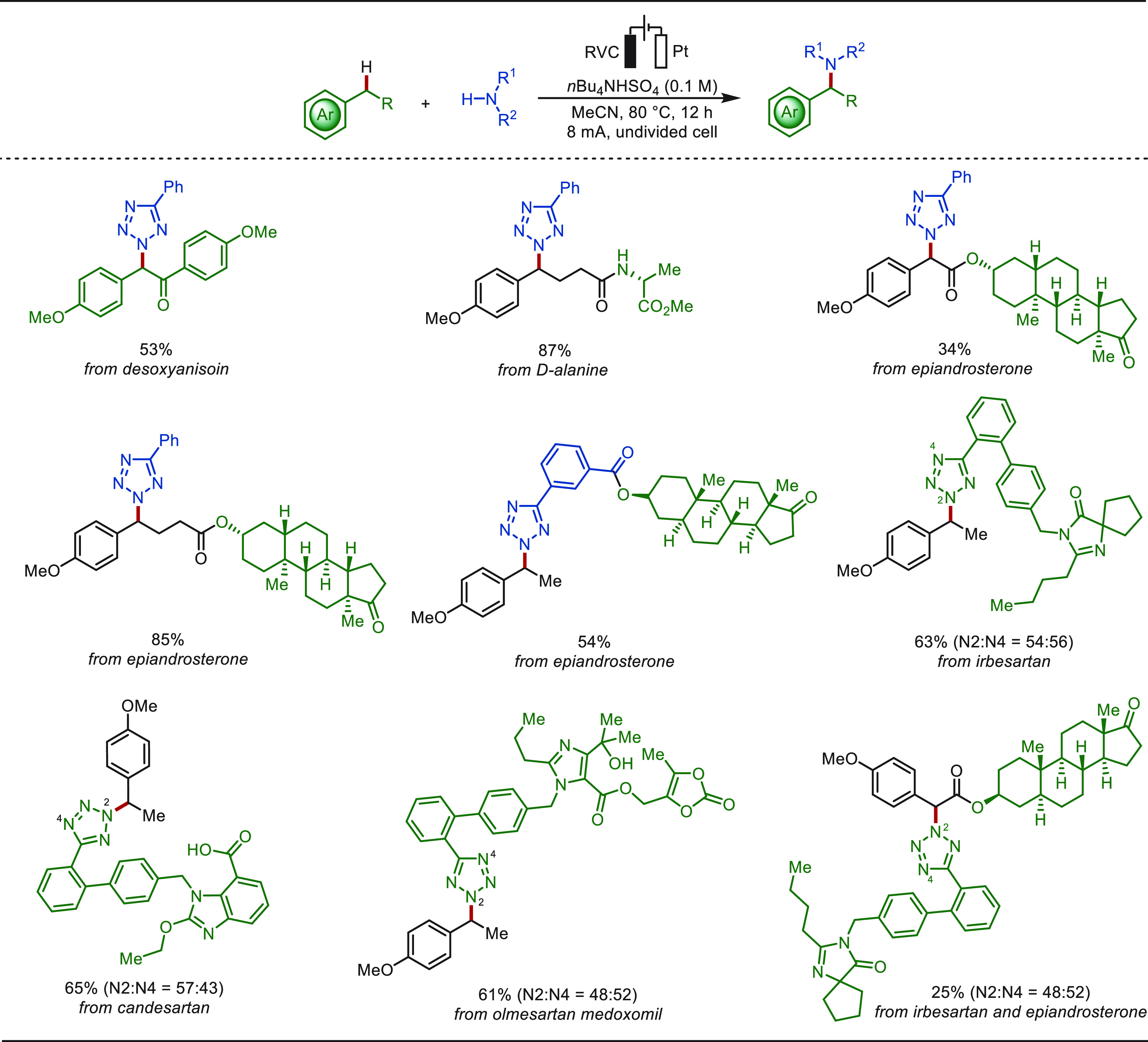

Later, Ruan and co-workers showed that azoles were suitable amination reagents for the electrochemical C–H/N–H cross-coupling reactions, with nBu4NHSO4 as the electrolyte and MeCN as the solvent in an undivided cell (Scheme 30).238 The azolation occurred efficiently and selectively at primary, secondary, and even challenging tertiary benzylic positions. This approach was directly exploited to install azole or benzyl motifs on a variety of structurally complex drug molecules.

Scheme 30. Electrochemical Late-Stage Benzylic C–H Azolation.

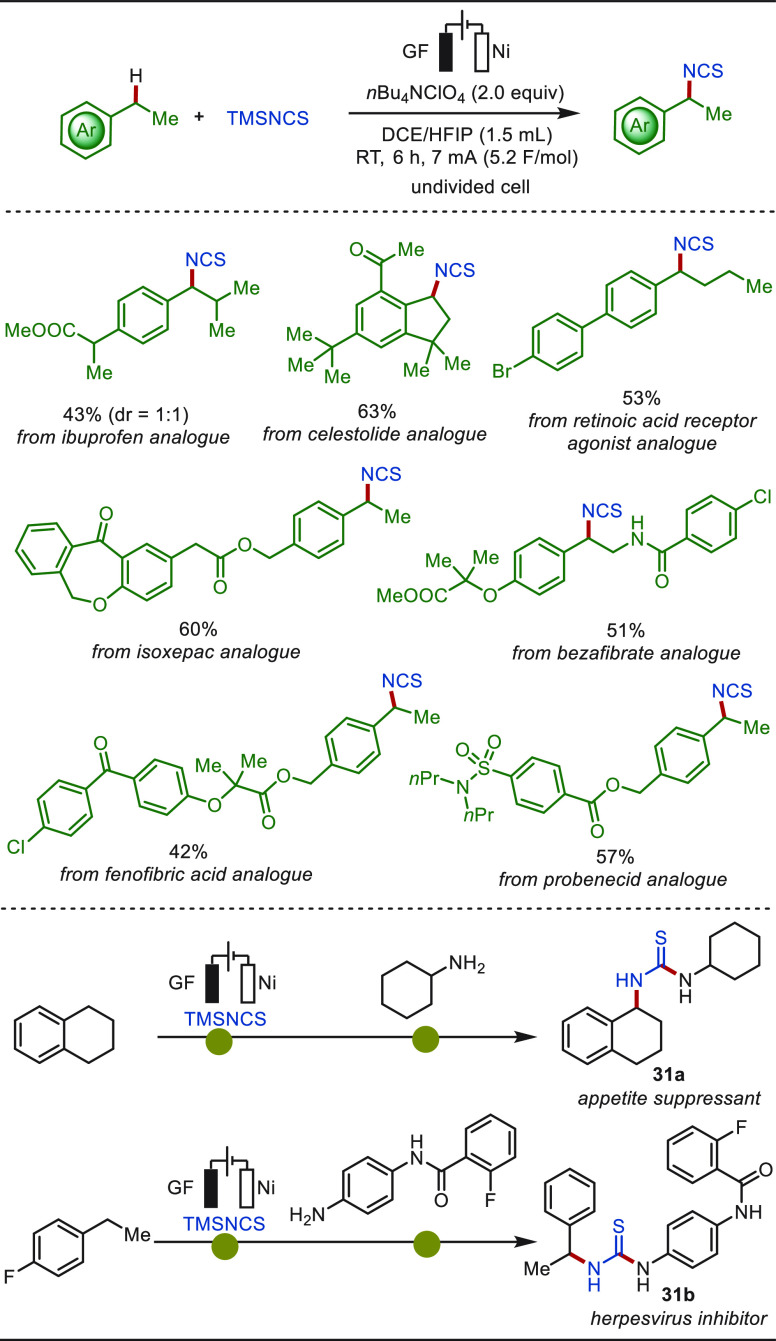

Direct C(sp3)–H isothiocyanations represent a straightforward strategy for the introduction of the versatile isothiocyanate functional group.239 Recently, Guo and Wen disclosed an electrochemical late stage benzylic C(sp3)–H isothiocyanation with TMSNCS (Scheme 31).240 A broad range of drug and bioactive molecules smoothly underwent the isothiocyanation under mild conditions with high chemo- and regio-selectivity. The chemoselectivity was attributed to the ready isomerization of in situ generated thiocyanates to isothiocyanates under the electrolysis conditions. In addition, with the electrochemical isothiocyanation strategy, two drug molecules—appetite suppressant 31a and herpesvirus inhibitor 31b—were prepared in a one-pot, two-step procedure from readily available alkylated arenes. In contrast, previous syntheses of these two compounds required four- and three-step processes, respectively.

Scheme 31. Electrochemical Late-Stage Benzylic C–H Isothiocyanation.

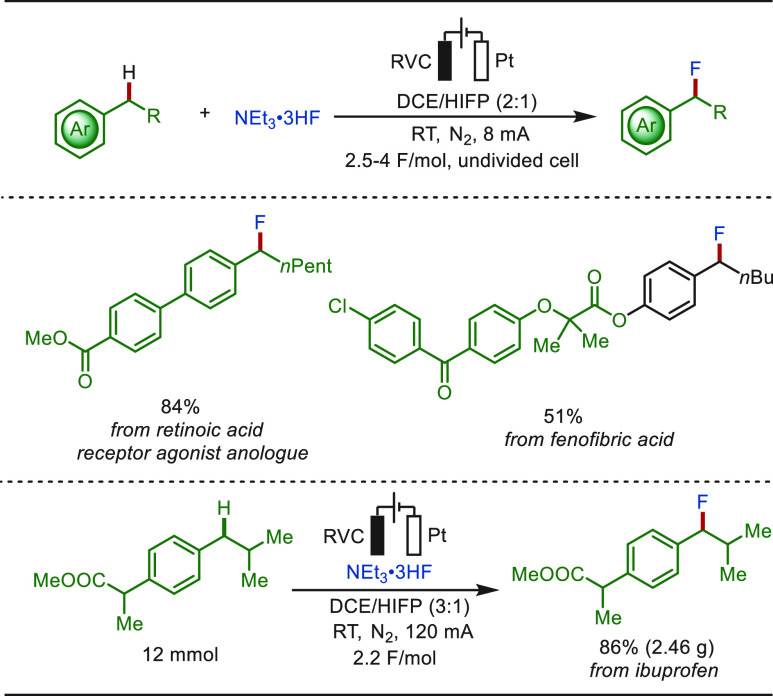

The straightforward and efficient introduction of fluorine is of great important in medicinal chemistry because of the unique properties of the C–F bond.241−245 In recent years, electrochemical fluorinations of C(sp3)–H bonds with nucleophilic fluoride sources have gained more attention.246−249 Recently, the Ackermann group developed a selective electrochemical C(sp3)–H fluorination with readily available NEt3·3HF, in lieu of alternative expensive electrophilic fluorine reagents (Scheme 32).249 External oxidants and transition-metal catalysts, as well as directing groups, were not required. The method displayed broad functional group tolerance, setting the stage for the late-stage fluorination of bioactive drugs. The practical utility was substantiated by fluorination of ibuprofen on a large scale of 2.5 g. Notably, adamantane was fluorinated at the tertiary position under otherwise identical electrolysis conditions, implying considerable potential for alkane modification. In addition, the synthetic utility of the C(sp3)–H fluorination could be further illustrated by a subsequent one-pot arylation of the generated benzylic fluorides.

Scheme 32. Electrochemical Late-Stage Benzylic C–H Fluorination.

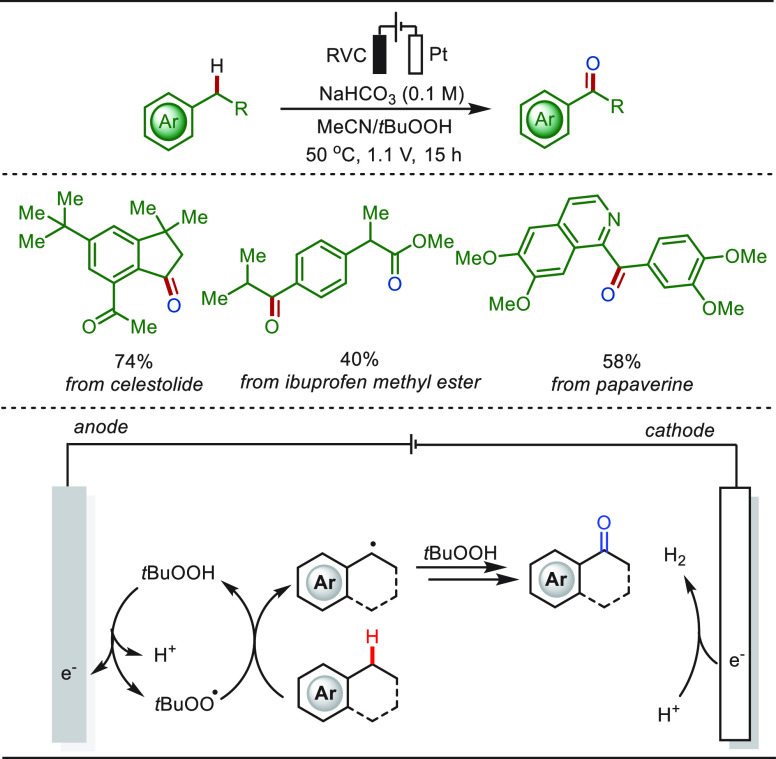

Ketones are versatile functional groups and omnipresent in natural products and biologically active compounds.250 Recently, Liu and co-workers developed a sustainable protocol for direct benzylic C–H bond oxidation of alkylarenes to provide the corresponding ketone compounds with tert-butyl hydroperoxide as the radical- and oxygen-source (Scheme 33).251 The tert-butyl peroxyl radical was first generated by mild anodic oxidation. Then, the hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) occurred to form a benzylic radical, which reacts with tBuOOH, affording the corresponding ketone. This approach was successfully applied to the LSF of bioactive molecules, including celestolide, ibuprofen methyl ester, and papaverine, in synthetically useful yields without affecting other functional groups.

Scheme 33. Electrochemical Late-Stage Benzylic C–H Bonds Oxidation to Form Ketones.

2.2.2. Late-Stage Allylic C(sp3)–H Functionalization

Over the past decade, late-stage allylic C(sp3)–H functionalization has attracted substantial interest among organic chemists, benefiting from the fact that the carbon–carbon double bond is widely present in natural products and drug molecules. The allylic C(sp3)–H bond features relatively low bond dissociation energy, which enables high site selectivity in structurally complex molecules. In this context, electrochemical late-stage allylic C(sp3)–H functionalization has witnessed considerable recent progress.252−255

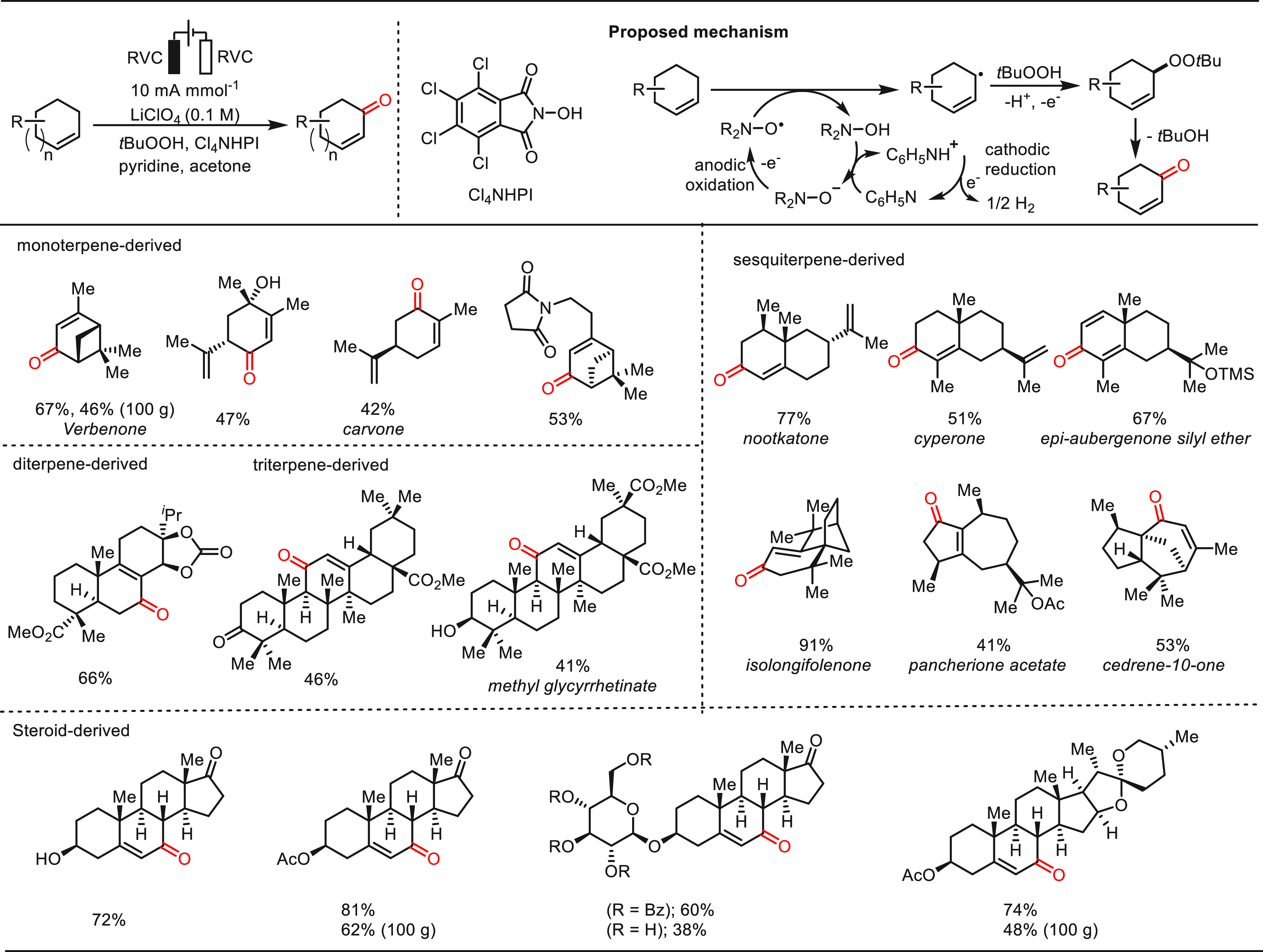

In 2016, Baran and co-workers described an elegant electrochemical allylic C(sp3)–H oxidation strategy using 20 mol % Cl4NHPI as a redox mediator, pyridine (2.0 equiv) as the base, tBuOOH (1.5 equiv) as a co-oxidant, and LiClO4 as the electrolyte (0.1 M) in acetone under constant-current conditions in an undivided cell (Scheme 34).255 This powerful electrochemical approach was characterized by a broad substrate scope, high chemoselectivity, and operational simplicity. A variety of representative terpenes were oxidized under the electrolysis conditions, affording corresponding versatile monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, diterpenes, triterpenes, and steroids, which have outstanding utilities in food, fragrance, and pharmaceuticals industries. Notably, the user-friendly and robust nature of this electrochemical allylic C–H oxidation was demonstrated by 100 g preparation of several products with good efficiency.

Scheme 34. Electrochemical Late-Stage Allylic C(sp3)–H Oxidation.

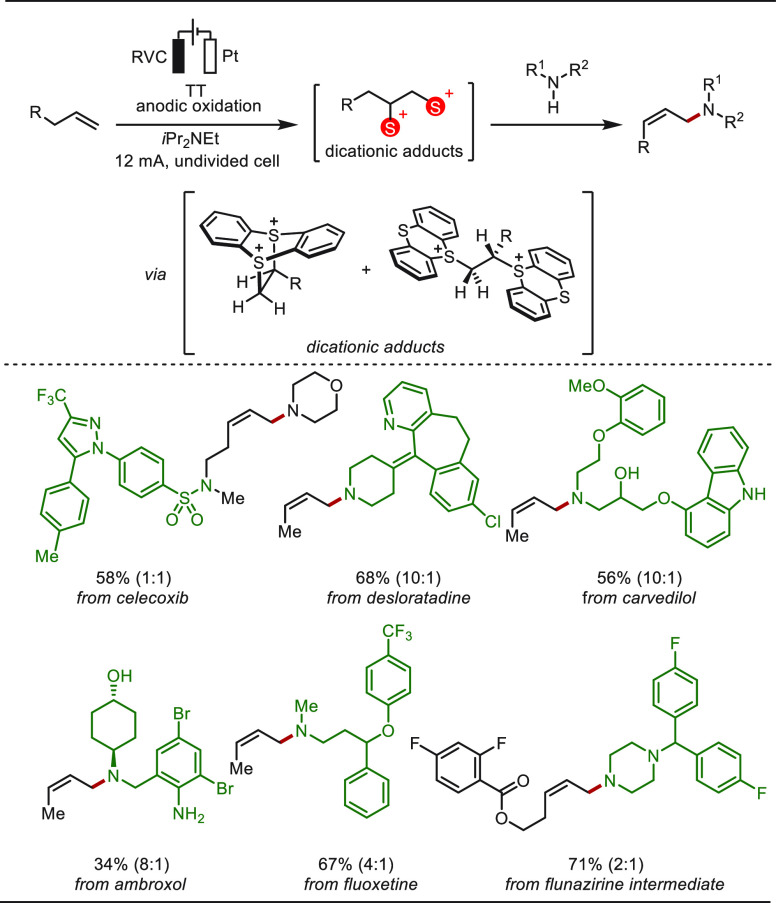

Allylic amines are valuable building blocks in molecular synthesis and they are likewise prevalent in diverse biologically active molecules.256−258 In 2021, Wickens and co-workers developed a most user-friendly electrochemical strategy to prepare aliphatic allylic amines by the oxidative coupling of unactivated alkenes with secondary aliphatic amines (Scheme 35).259 This reaction proceeded via the electrochemical formation of a dicationic alkene-bis(thianthrene) adduct between thianthrene (TT) and the alkene substrate. Treatment of these adducts with aliphatic amines and base efficiently provides the corresponding linear, tertiary allylic amine products in high Z selectivity. Complex biologically active molecules are amenable to this transformation as both amine and alkene partners. Mechanistic studies revealed the vinylthianthrenium salts as the key reactive intermediates.

Scheme 35. Electrochemical Late-Stage Allylic C(sp3)–H Amination.

2.2.3. Late-Stage α-C(sp3)–H Functionalization of Carbonyls

The diversification of the C(sp3)–H bond adjacent to a carbonyl group is among the most basic transformations of utmost utility in molecular chemistry. Representative examples include the Claisen condensation, aldol reactions, or the Mannich reaction. In this context, α-C(sp3)–H functionalization of carbonyl compounds has been extensively explored.260−268 Particularly, significant recent momentum has been gained in eLSF and preparation of pharmaceutical derivatives.

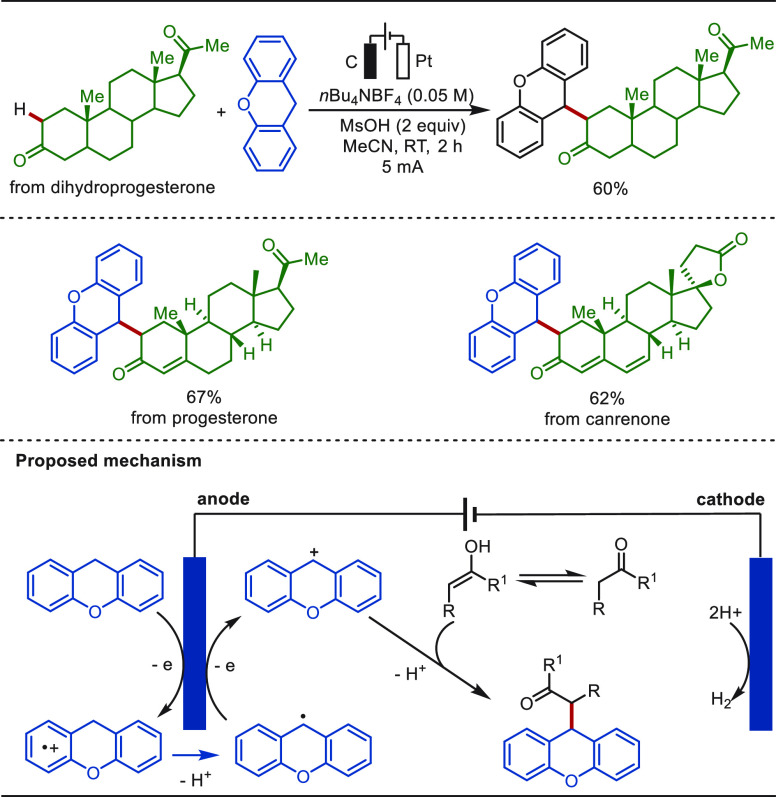

In 2020, Li and Song reported a practical electro-oxidative dehydrogenative cross-coupling of ketones with xanthenes (Scheme 36).261 This transformation was performed under mild conditions, featuring a high atom economy and excellent functional-group tolerance. Drug molecules including dihydroprogesterone, progesterone, and canrenone proved to be compatible with the electrochemical C(sp3)–H/C(sp3)–H cross-coupling reactions, giving the corresponding products in excellent yields. Mechanistic studies indicated that a stabilized carbocation was first generated via anodic oxidation of xanthene. Then, the intermediate reacted with the nucleophilic enol to afford the cross-coupling product.

Scheme 36. Electrochemical Dehydrogenative Cross-Coupling of Ketones with Xanthenes (66).

Carbonyl desaturation to enone is a fundamental organic oxidation that was widely employed in organic synthesis.269 Established approaches to achieve this transformation generally rely on transition metals (Cu or Pd) or stoichiometric oxidative reagents.270−273 In 2021, Baran and co-workers disclosed an operationally simple electrochemical method to access such structures from enol phosphates or silanes, which can be readily formed from carbonyls (Scheme 37).262 This electrochemically driven desaturation (EDD) was characterized by a broad substrate scope including a variety of ketones and lactams. Notably, the late-stage site-selective desaturation of structurally complex molecules, which is difficult to achieve, afforded the desired enones in synthetically useful yields. In addition, the practical utility of the EDD was further illustrated by the desaturation of 4 g of cyclopentadecanone-derived silyl enol ether 37a to afford cyclopentadecenone 37b, which is easily converted to the valuable (R)-muscone 37c. Increasing the current from 10 to 300 mA and using alternating polarity enabled the EDD reaction to smoothly afforded compound 37b in a 66% isolated yield. By further increasing the current to 3.6 A, 100 g of 37a was successfully converted into 37b in a 61% yield in a flow apparatus that contained six reaction cells. Mechanistic studies suggested a radical-based manifold, involving two consecutive single-electron oxidations of enol silane to form oxonium, which released the desired enone after hydrolysis.

Scheme 37. Electrochemically Driven Late-Stage Desaturation of Carbonyl Compounds.

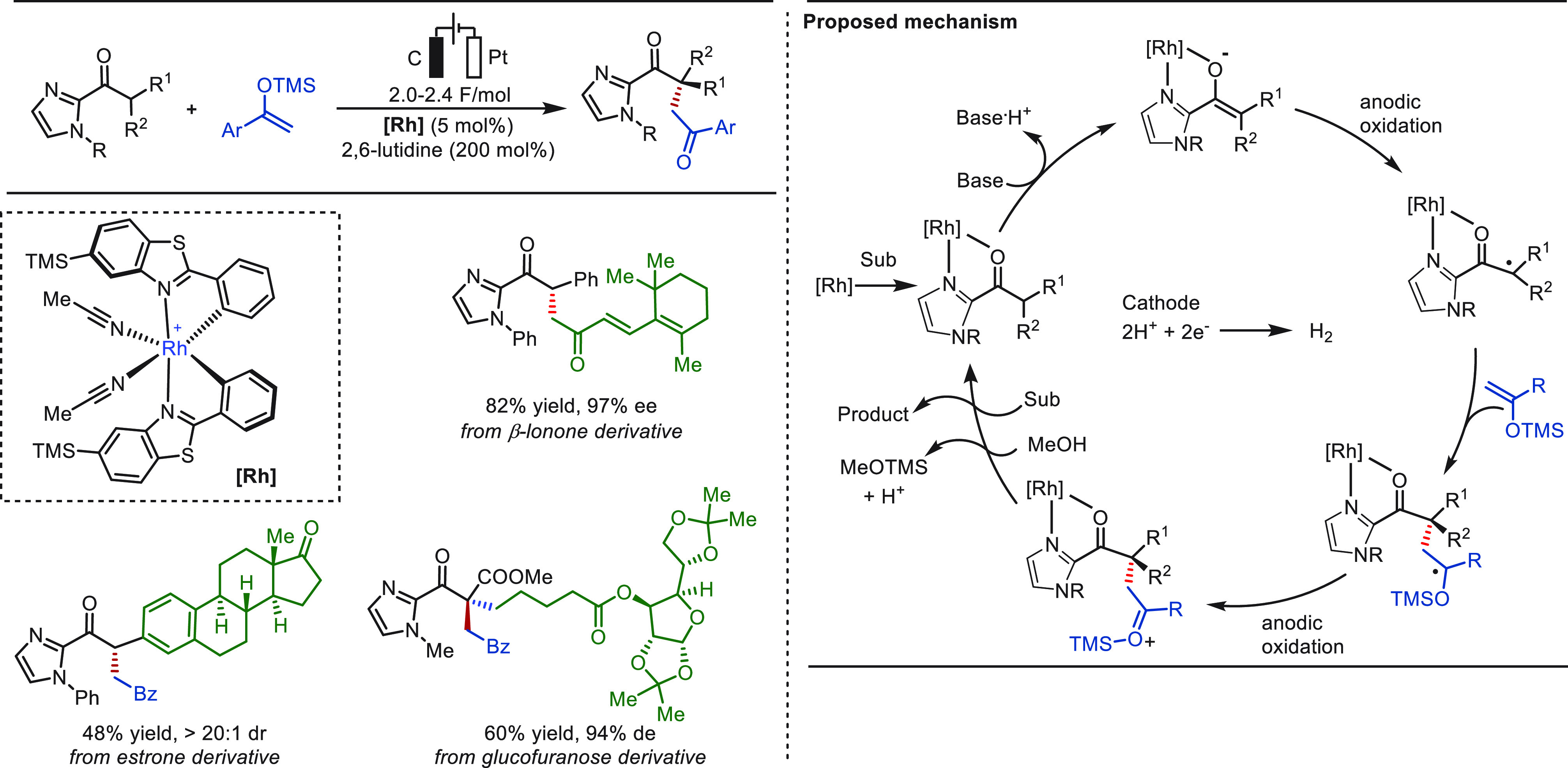

By the merger of organic electrosynthesis with asymmetric catalysis, the Meggers group introduced, in 2019, a versatile electricity-driven chiral Lewis acid catalyzed asymmetric coupling of 2-acyl imidazoles with silyl enol ethers to generate synthetically useful 1,4-dicarbonyls, which include products bearing all-carbon quaternary stereocenters (Scheme 38).263 The chiral-at-metal rhodium catalyst played a dual role in both the electrochemical step and to guarantee the asymmetric induction, enabling mild reaction conditions, a broad substrate scope, and high chemo- and enantioselectivities (up to >99% ee). The robustness of this approach is further demonstrated by the effective generation of complex products derived from β-ionone estrone and glucofuranose. Notably, the cleavage of the imidazolyl group could be achieved without a significant loss of optical purity.

Scheme 38. eLSF by α-C(sp3)–H Functionalization of Carbonyls.

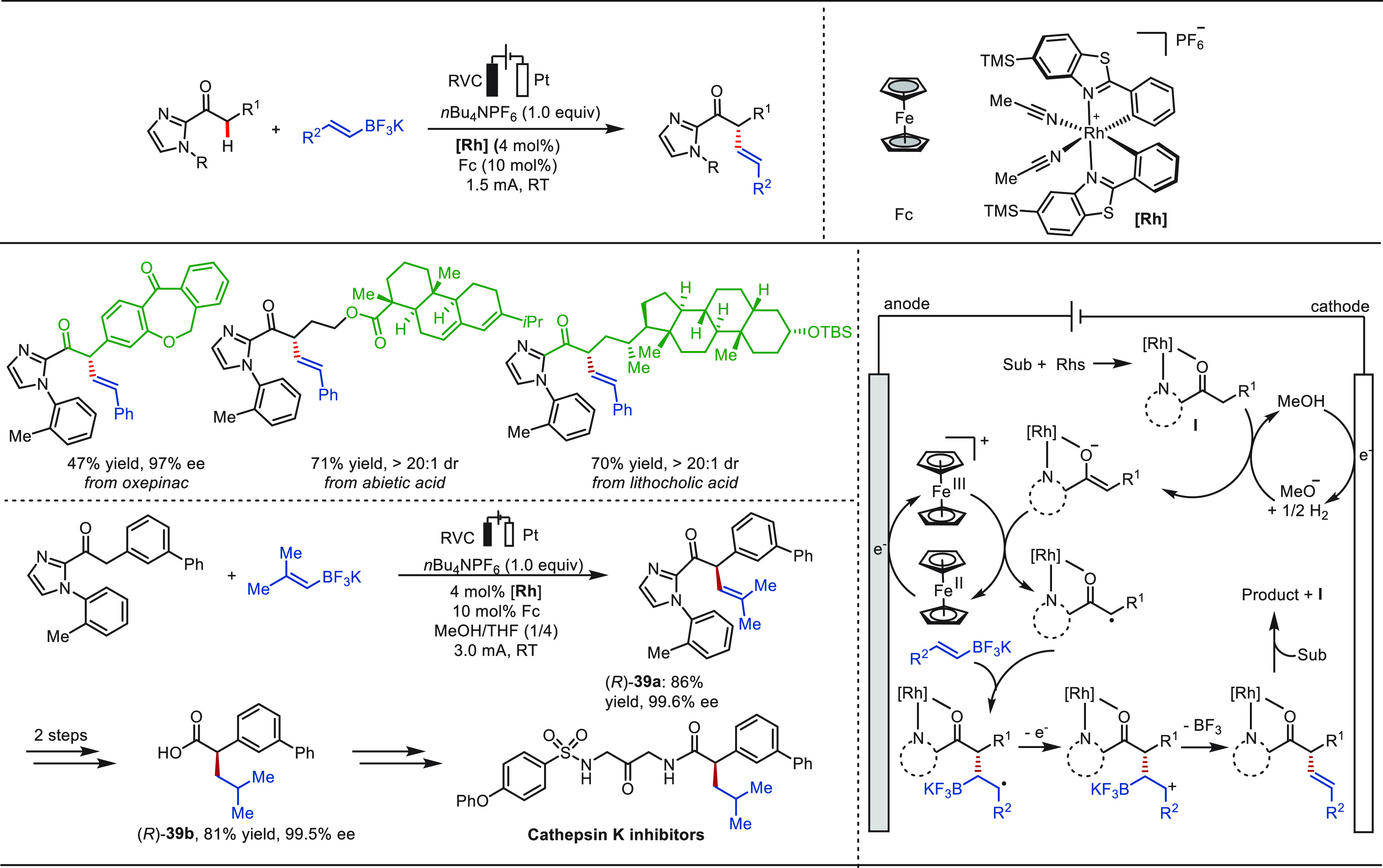

Recently, Meggers and co-workers reported another conceptually related approach to achieve enantioselective α-C(sp3)–H alkenylation of ketones with potassium alkenyl trifluoroborates (Scheme 39).264 The electrochemical asymmetric oxidative coupling reaction features a broad substrate scope, high yields (up to 94%), and exceptional enantioselectivities (≥99% ee). Catalytic amounts of ferrocene were used as the redox mediator, which enables the key chiral rhodium-involving single-electron transfer reaction to homogeneously occur in the solution rather than at the electrode surface, hence providing mild electrochemical conditions. The eLSF alkenylation of complex molecules derived from oxepinac, abietic acid, and lithocholic acid were accomplished in excellent yields via the electricity-driven asymmetric synthesis method. Moreover, this approach was applied to the straightforward assembly of intermediates (R)-39a of the cathepsin K inhibitor in 86% yield with an ee value up to 99.6%.

Scheme 39. Electrochemical Late-Stage α-C(sp3)–H Alkenylation of Carbonyls.

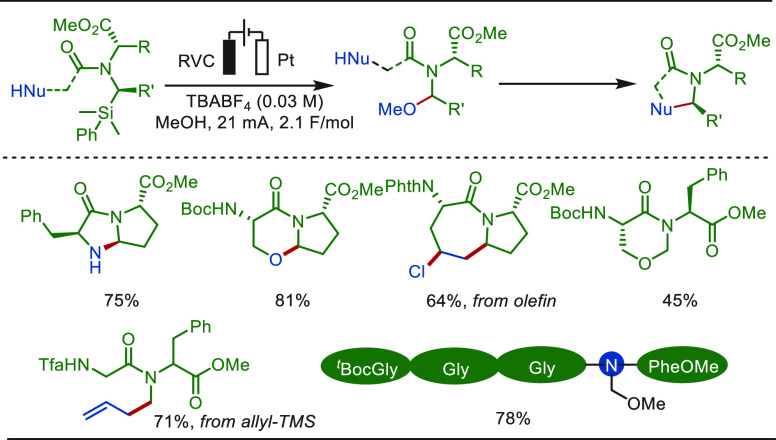

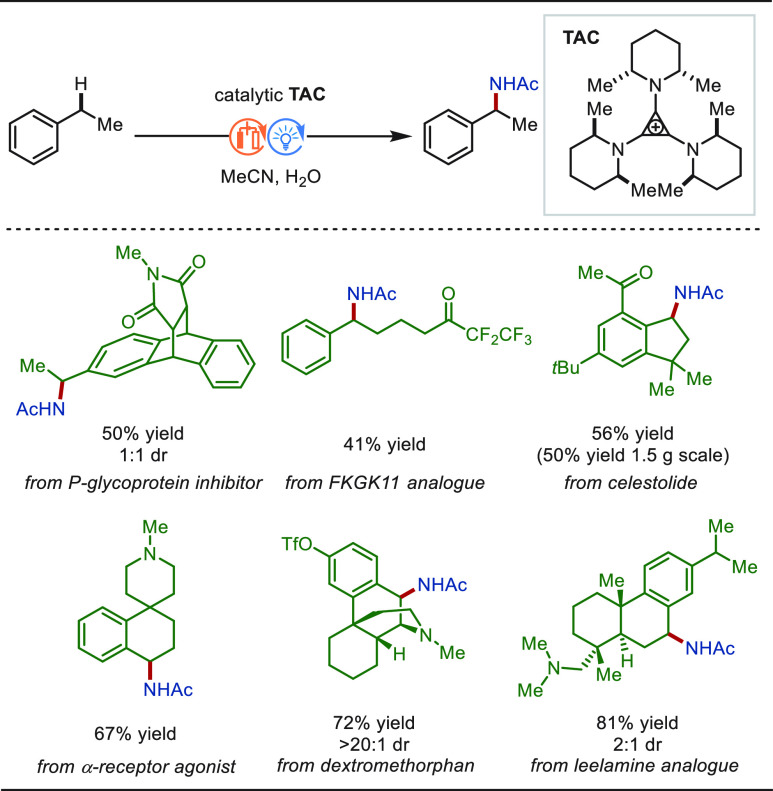

2.2.4. Late-Stage α-C(sp3)–H Functionalization of Amines

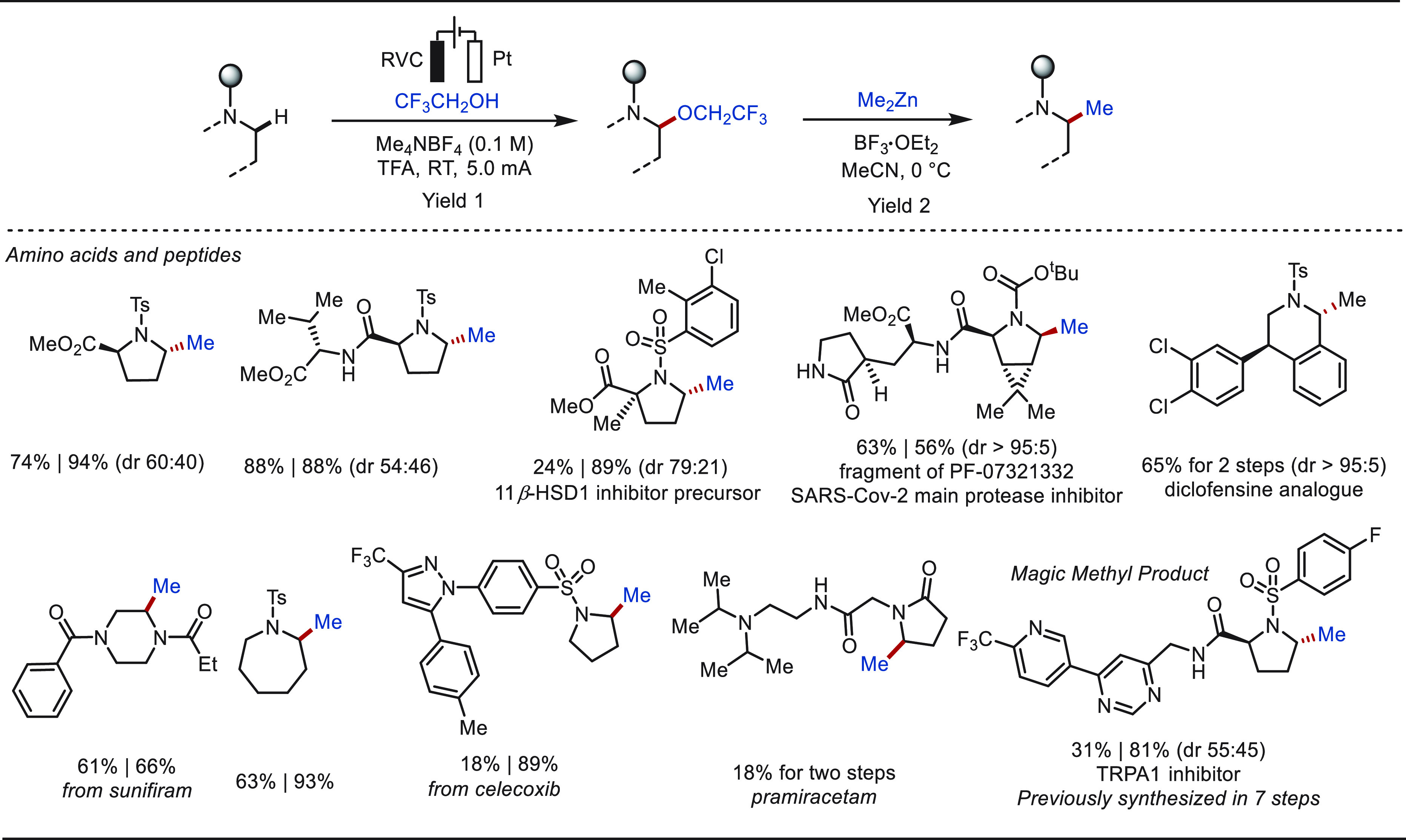

The electrochemical functionalization of C(sp3)–H bonds adjacent to nitrogen atoms, such as the well-esablished Shono oxidation, has been wildly applied in organic synthesis.274,275 However, until recently, it was primarily employed for the functionalization of structurally simple compounds. Based on the classic Shono oxidation reaction, Lin and Terrett recently reported a modular and practical strategy for eLSF α-methylation of structurally complex amines derivatives (Scheme 40).276 The electro-oxidation generated N,O-acetal readily reacted with organozinc reagents, enabling the facile installation of a methyl moiety as well as various other important groups. This improved electrochemical protocol features operational simplicity and high functional group compatibility. The site-selective late-stage methylation of a variety of bioactive targets, has been efficiently achieved. Notably, a drug molecule of TRPA1 inhibit, which has been explored for the “magic methyl” effect, presenting a >10-fold boost in potency, was previously synthesized using de novo routes in a total of 7 steps.277 In sharp contrast, this compound could be readily prepared from its parent inhibitor by this electron driven approach.

Scheme 40. Electrochemical Late-Stage α-Methylation of Amines.

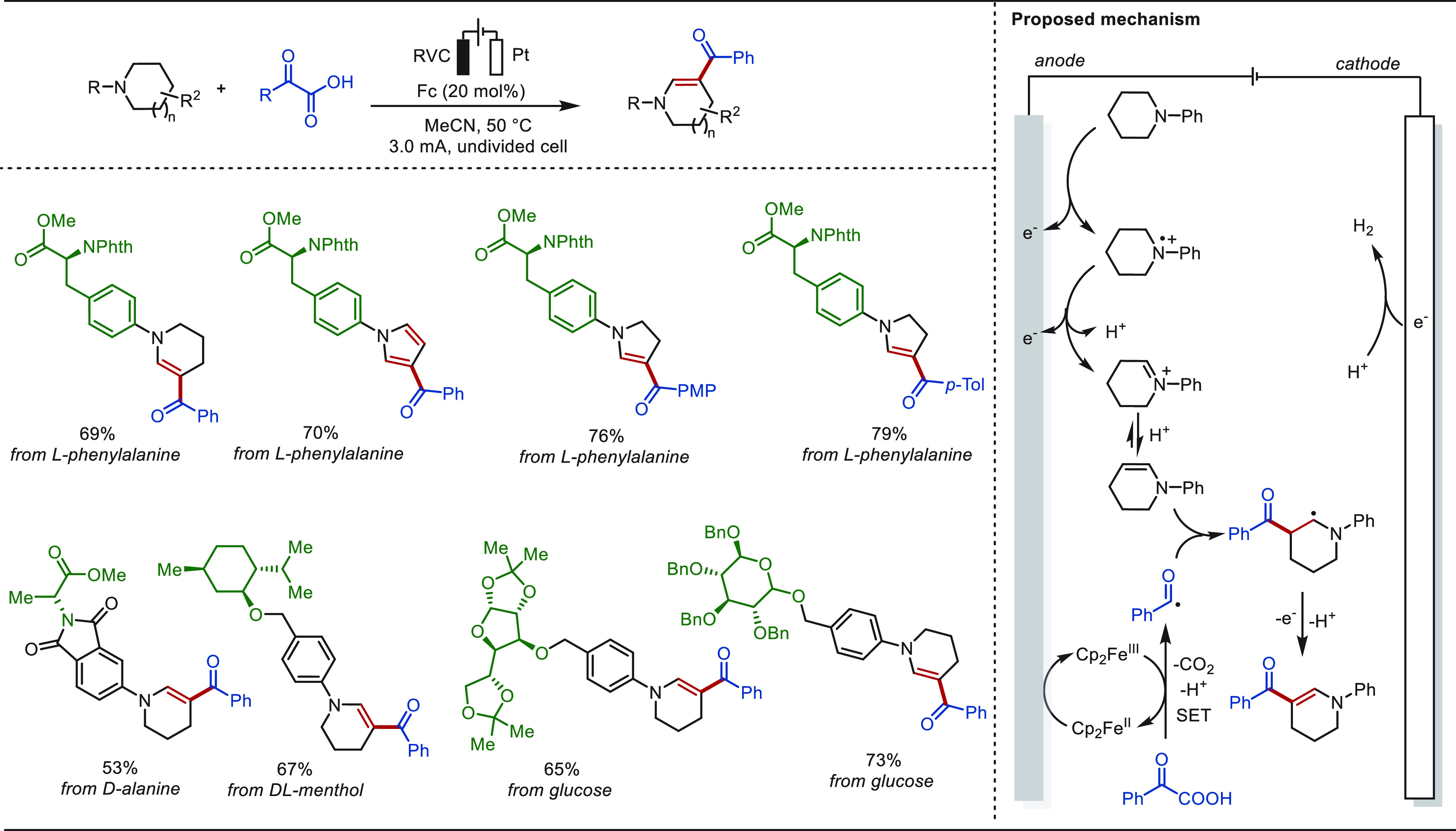

Electrochemical dehydrogenation based on the α-C(sp3)–H activation of amines represent an important organic transformation to ubiquitous unsaturated compounds.278−283 In 2018, the Lei group disclosed a TEMPO-mediated dehydrogenation of N-heterocycles in an undivided cell to access a variety of five- and six-membered nitrogen-heteroarenes without the usage of sacrificial hydrogen acceptors.282 Recently, Qiu and co-workers reported a straightforward and robust approach of electrochemically driven desaturative β-C(sp3)–H functionalization of cyclic amines (Scheme 41).284 Various β-substituted desaturated cyclic amines were obtained under constant current electrolysis in MeCN at 50 °C. This transformation was achieved via multiple single-electron oxidation processes with catalytic amounts of ferrocene as a redox mediator. The unique utility of this approach was clearly demonstrated by the eLSF of natural products and derivatives (Scheme 41). Diverse pyrrolidine- or piperidine-containing molecules deriving from l-phenylalanine, d-alanine, d,l-menthol, glucofuranose, and glucopyranose afforded the corresponding desaturated acylation products in excellent yields. Notably, the reaction of l-phenylalanine bearing a pyrrolidine motif with phenylacetic acid formed a pyrrole product through further electro-oxidation.

Scheme 41. Electrochemically Driven Desaturative β-C(sp3)–H Functionalization of Amines.

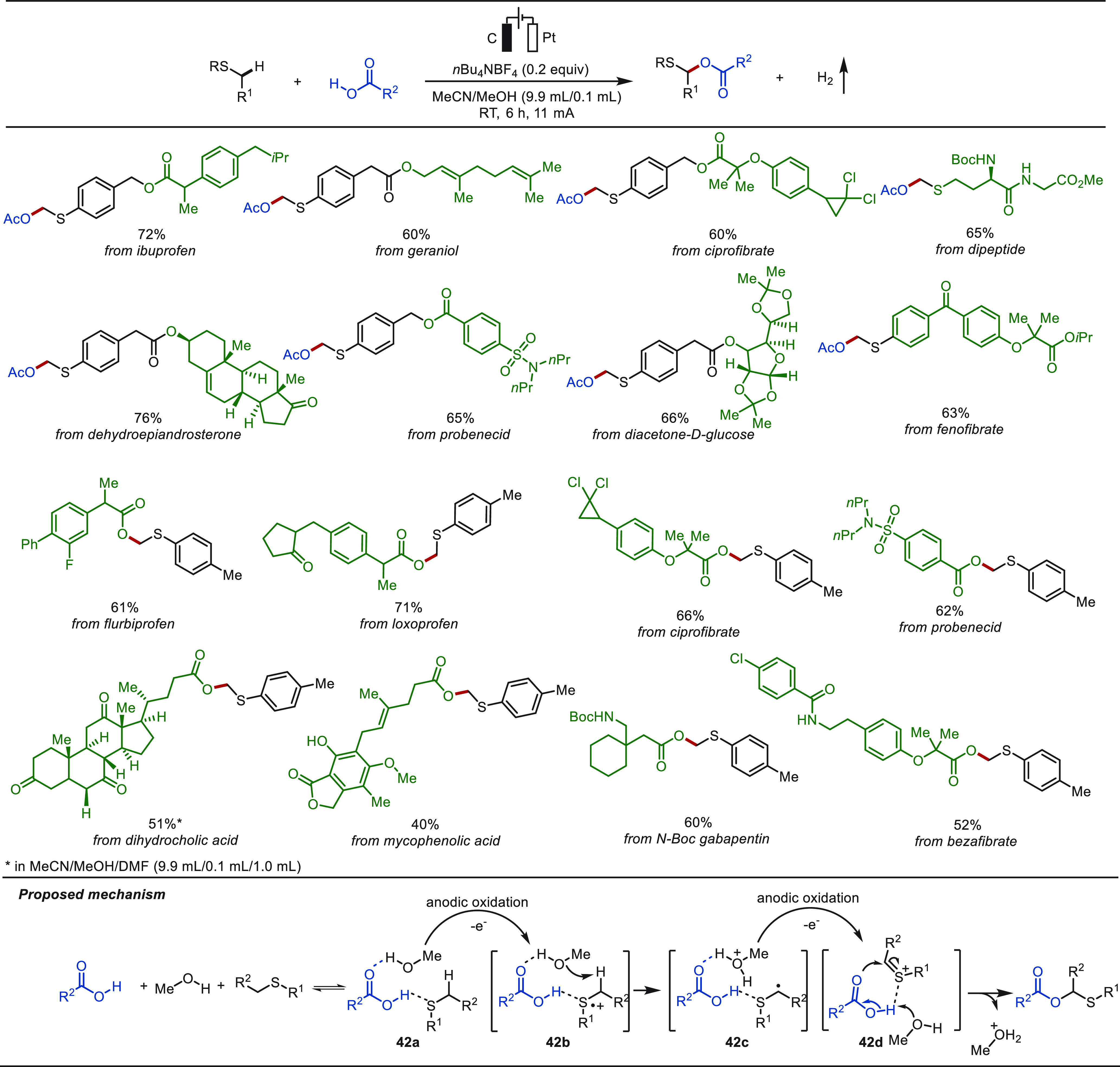

2.2.5. Late-Stage C(sp3)–H Functionalization of Sulfides

The precise and selective activation of oxidation-sensitive sulfur-containing compounds is a significant challenge due to its inherent activity and complicated valence states.285 In 2021, Lei and co-workers reported on an electrochemical protocol for the construction of α-acyloxy sulfides, which represent key structural motifs in agrochemicals and pharmaceuticals (Scheme 42).286 This electro-oxidized C(sp3)–H/O–H cross-coupling protocol was found to be environmentally friendly, highly selective, and scalable while featuring an exceptionally broad substrate scope. The robustness and utility of this protocol was demonstrated by the efficient eLSF of a wealth of bioactive molecules, including amino acids, peptides, and pharmaceuticals. Mechanistic studies suggested a synergistic effect of the self-assembly induced C(sp3)–H/O–H coupling pathway. Sulfide, AcOH, and MeOH assemble into an adduct, and hydrogen bonding between AcOH and the sulfur atom can facilitate a SET oxidation of sulfide. MeOH selectively captures the proton to form the state 42c with high regioselectivity. Then, a thionium ion is generated via the loss of a proton and an electron, and the desired product is finally delivered after the nucleophilic attack of AcOH to the thionium ion.

Scheme 42. Electrochemical Late-Stage α-C(sp3)–H Acyloxylation of Sulfides.

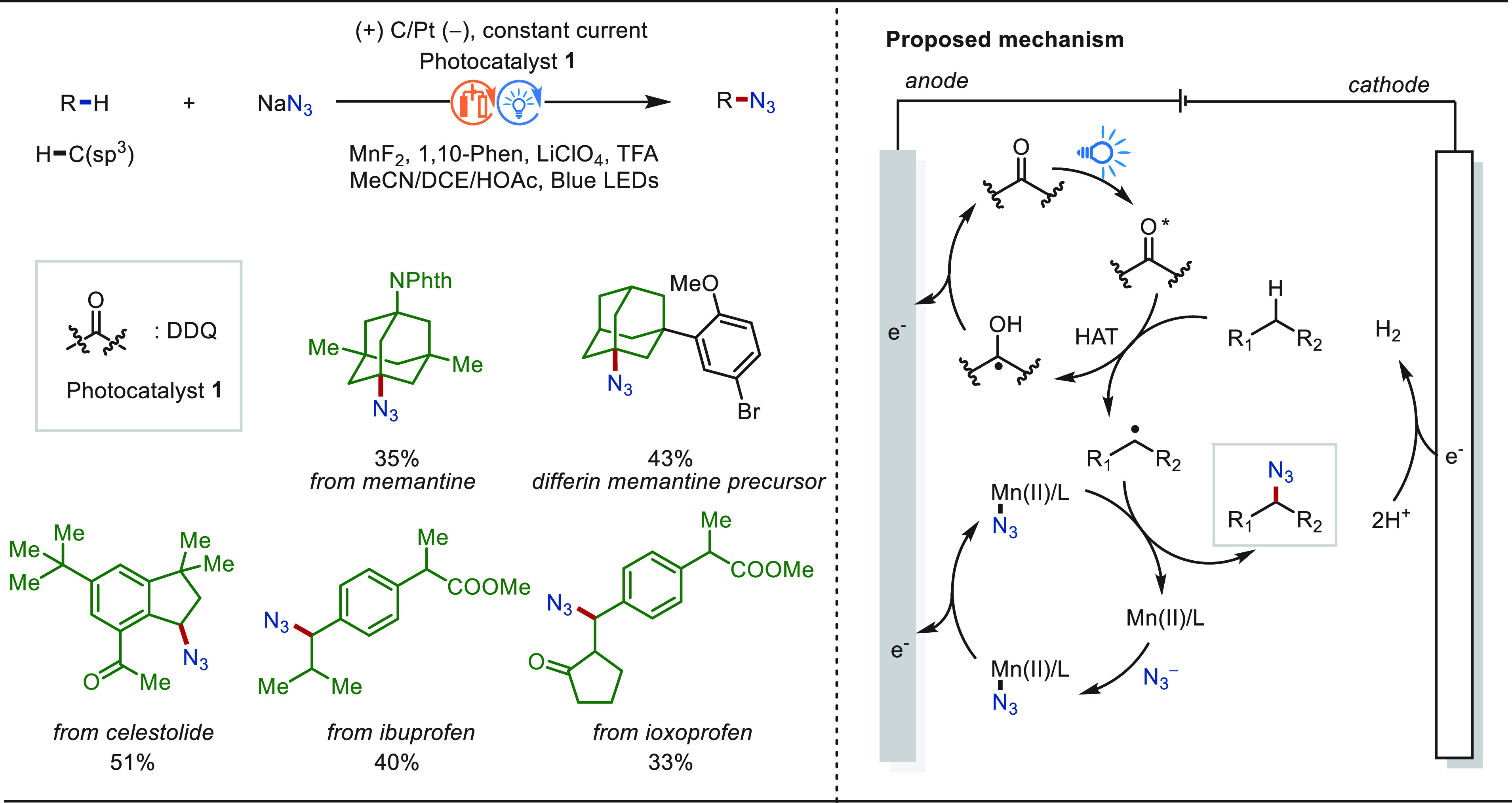

2.2.6. Late-Stage Unactivated C(sp3)–H Functionalization

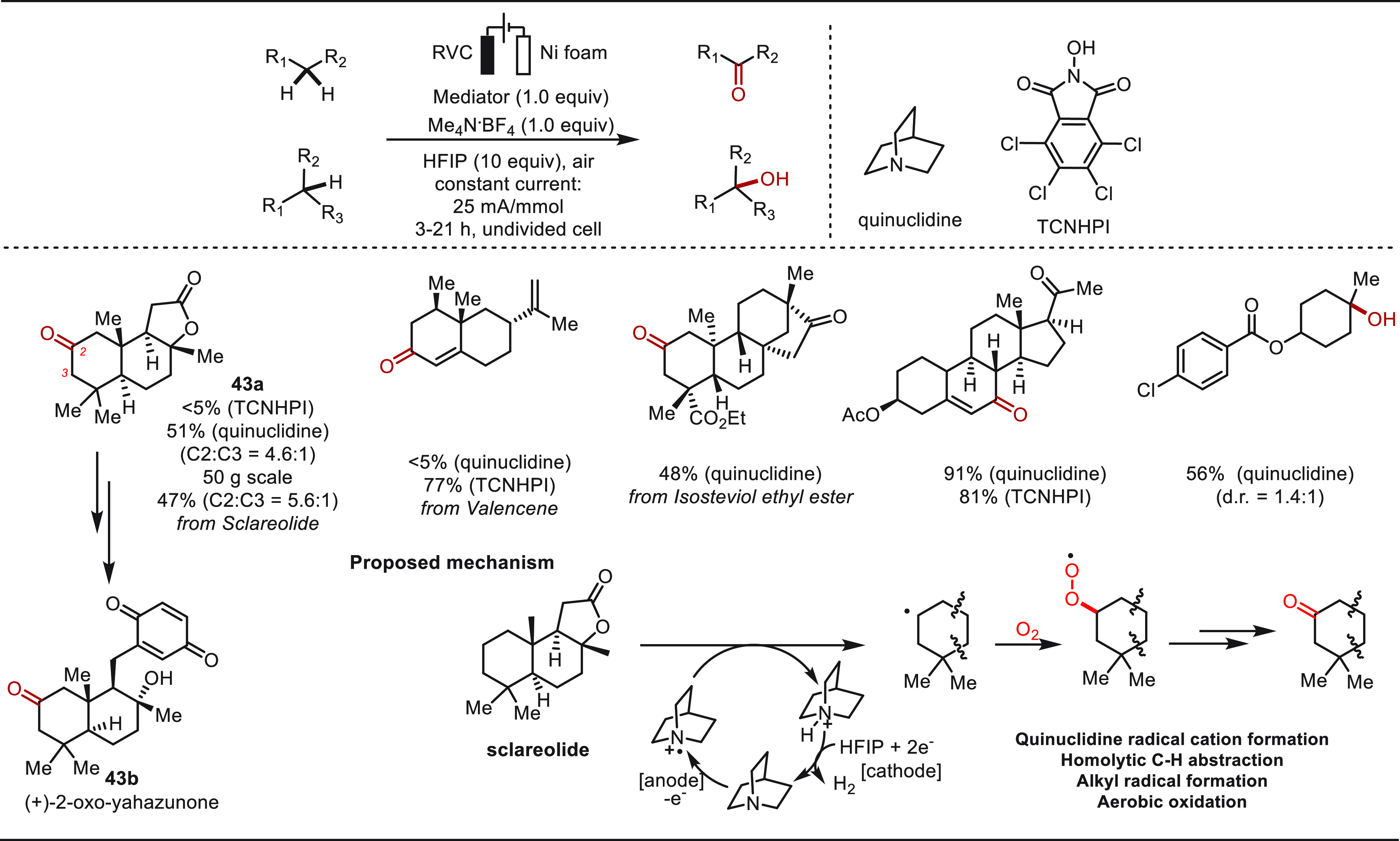

Unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds generally feature a high redox potential of more than 3.0 V vs SCE.287 Thus, the direct electrolysis of the C(sp3)–H bond represents a formidable challenge, since oxidation of other functionalities or solvents is likely to occur prior to the desired C–H oxidation of simple alkanes. Despite the difficulties, scientists have made remarkable progress in electrochemical late-stage functionalization of unactivated C(sp3)–H bond by the use of redox mediators or transition-metal catalysts.288,289

In 2017, the Baran group presented a practical electrochemical oxidation of otherwise unactivated C–H bonds in MeCN with Me4NBF4 as the electrolyte and HFIP as the additive (Scheme 43).288 Identification of a suitable redox mediator was the key to success for high yields and chemoselectivities. While using quinuclidine as a mediator allowed the selective late-stage oxidation of Sclareolide in a 51% yield at ca. 1.8 V vs SCE Ag/AgCl, the use of TCNHPI as mediator is superior on those bearing multiple olefin motifs, such as valencene. The quinuclidine-based redox mediator system further proved compatible for the eLSF of isosteviol ethyl ester and oxidation of a terpene to a relative steroid. In addition, a tertiary C–H bond is efficiently oxidized to the corresponding alcohol under the quinuclidine-mediated electrolysis. The utility of this protocol was illustrated with a 50 g scale late-stage oxidation of sclareolide to 43a, which is a key intermediate for the synthesis of (+)-2-oxo-yahazunone. Mechanistically, the in situ anodic oxidation generated quinuclidine radical cation served as a HAT reagent and O2 was involved in the later aerobic oxidation step.

Scheme 43. Electrochemical Late-Stage Oxidation of Unactivated C(sp3)–H Bonds.

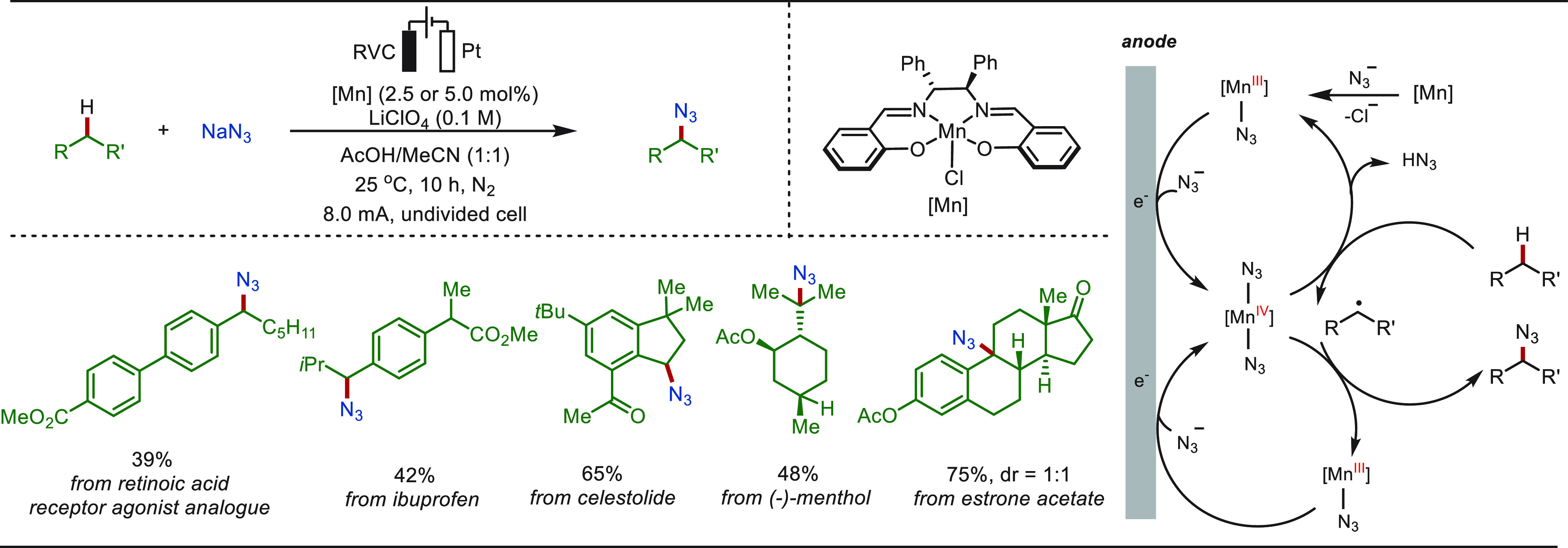

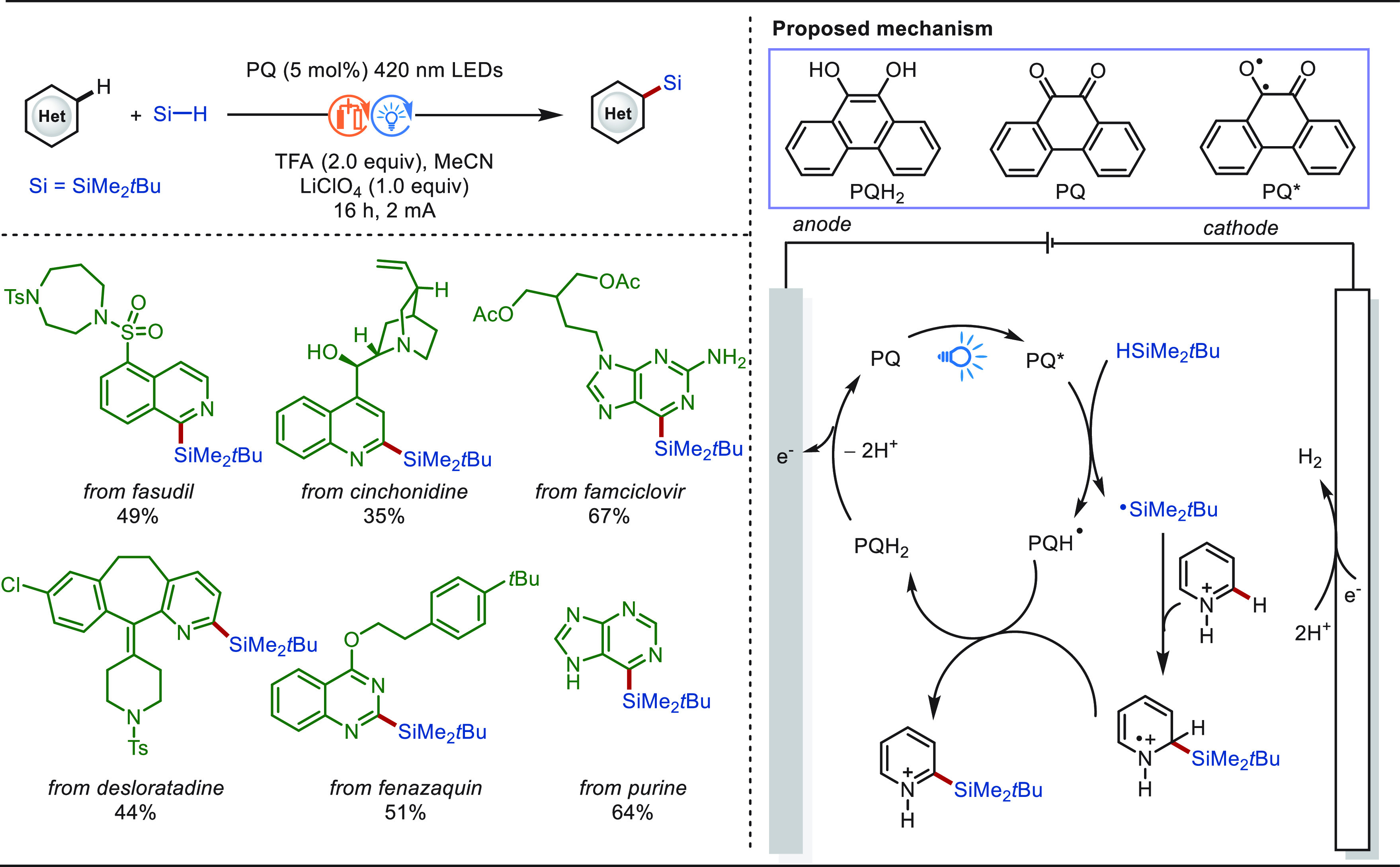

Organic azides are key intermediates for numerous transformations in medicinal chemistry, peptide chemistry, or molecular biology.290−292 Traditionally, stoichiometric amounts of strong indiscriminate chemical oxidants, such as NFSI and hypervalent iodine reagents, are required to install the azido group into C(sp3)–H bonds. By contrast, in 2021, the Ackermann group disclosed a manganaelectro-catalyzed C–H azidation of otherwise unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds with most user-friendly NaN3 as the nitrogen-source and traceless electrons as the sole redox-reagent (Scheme 44).289 The robustness and practicability of the resource-economic method was highlighted by the eLSF azidation of a variety of bioactive molecules. Detailed mechanistic studies supported a unique manganese(III/IV) regime, avoiding overoxidation to the carbocation and thus suppressing undesired side-reactions to oxygenated products.

Scheme 44. Electrochemical Late-Stage C(sp3)–H Azidation.

The merger of electrochemistry with organometallic catalysis has shown significant advances in C(sp3)–H activation. For example, Mei and Sanford, respectively, have achieved unactivated C(sp3)–H bond oxygenation by palladium catalysis under electrochemical conditions.293,294 This strategy is expected to be used in the late-stage modification of bioactive molecules in the future.

2.3. eLSF of C(sp)–H Bonds

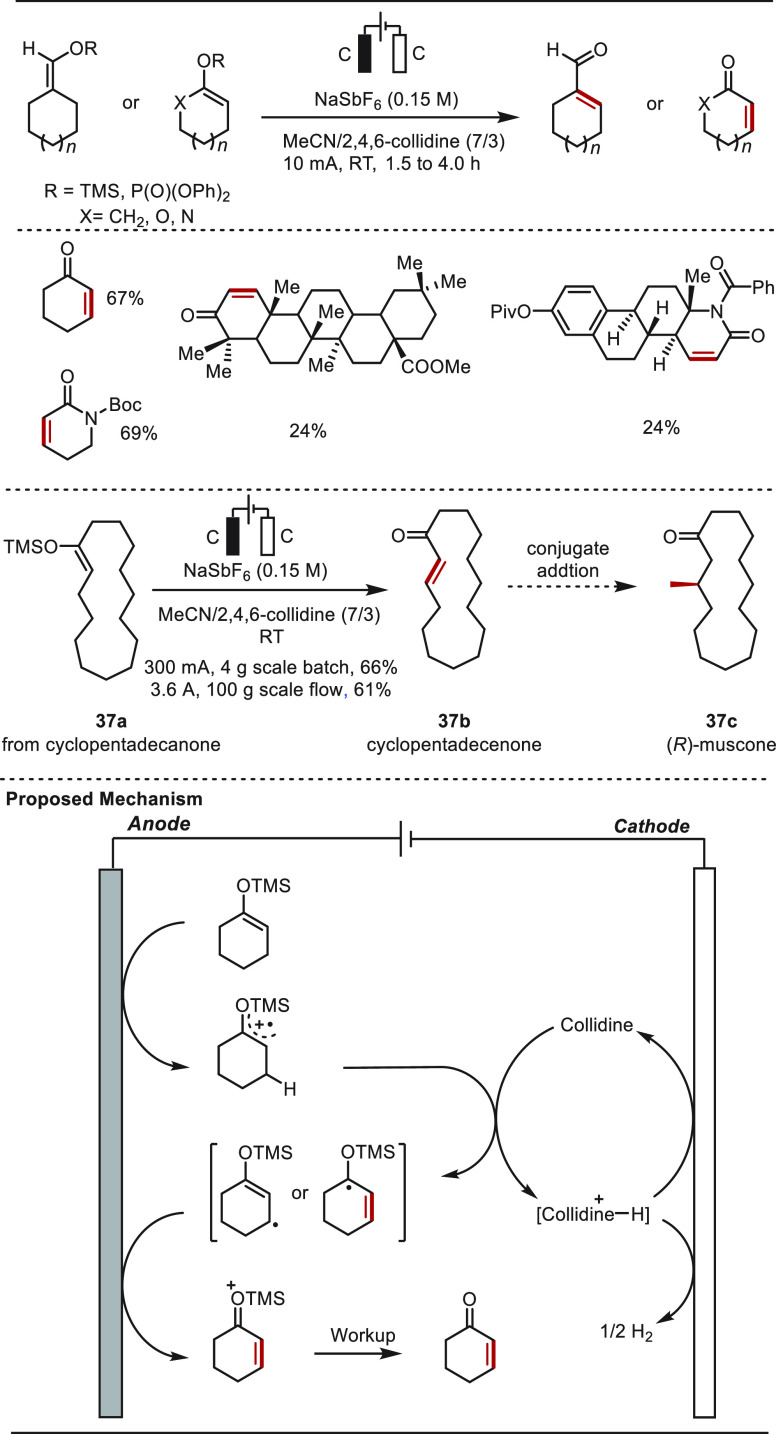

Oxidative carbonylation of alkynes represents an important transformation in molecular synthesis that generally uses O2 as the oxidant. However, the explosibility of gas mixtures of CO/O2 (12.5–74.0%) deters scalable application of this process. In 2019, the Lei group disclosed an electro-oxidative palladium-catalyzed carbonylation of alkynes to 2-ynamides under copper- and O2-free conditions (Scheme 45). This transformation occurred under potentiostatic conditions, and the role of the current was to oxidize Pd(0) to Pd(II), which was also the rate-determining step of this process. The eLSF of propyzamide with CO (1 atm) and NH4NO3 furnished corresponding propiolamide in a 63% yield. Primary and secondary amines proved to be amenable for this electrochemical aminocarbonylation reaction. Drug molecules, including desloratadine, fluoxetine, and desbenzyl donepezil, smoothly underwent eLSF, affording desired 2-ynamides in satisfactory yields.

Scheme 45. Electrochemical Palladium-Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation of Terminal Alkynes.

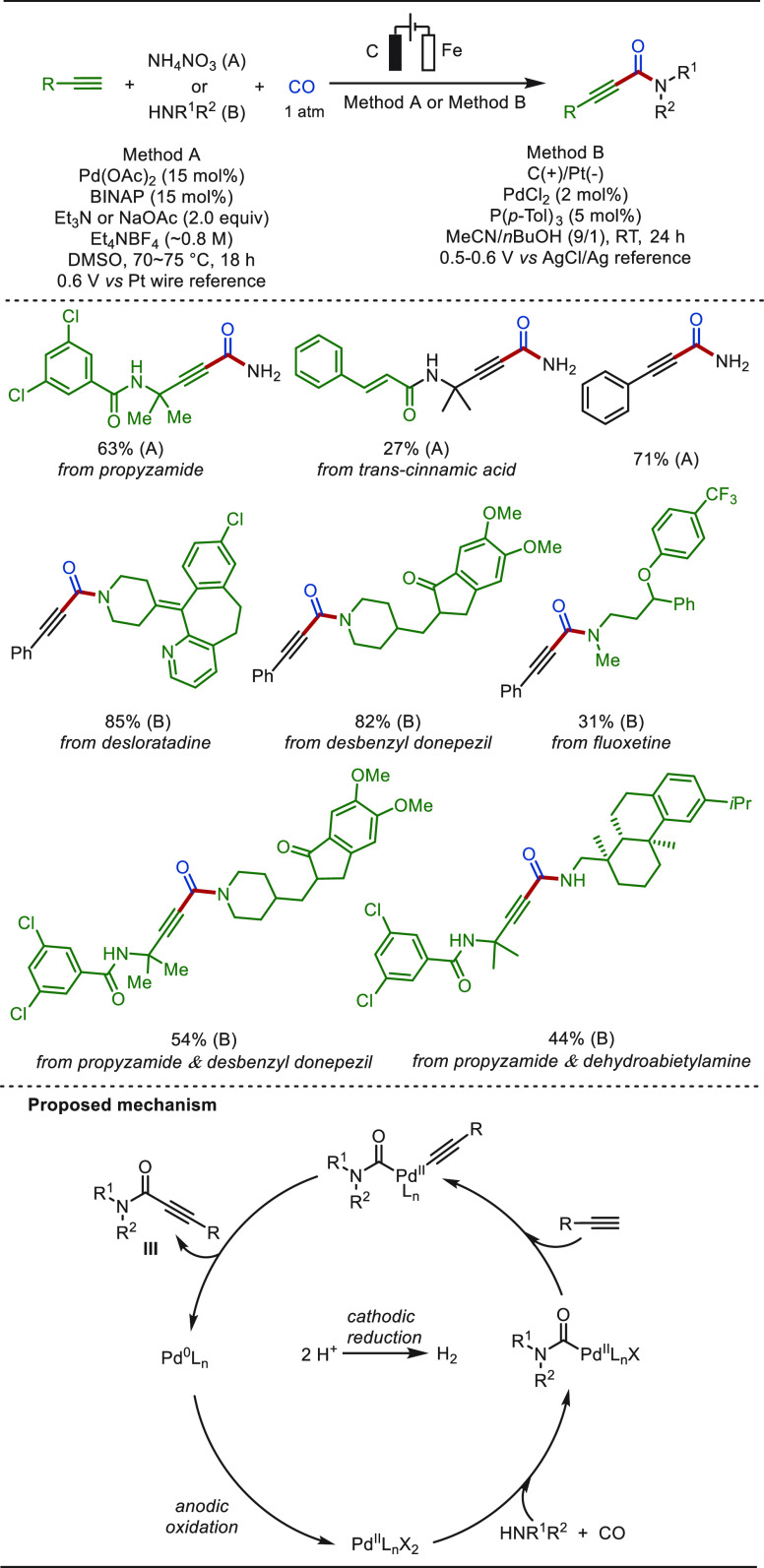

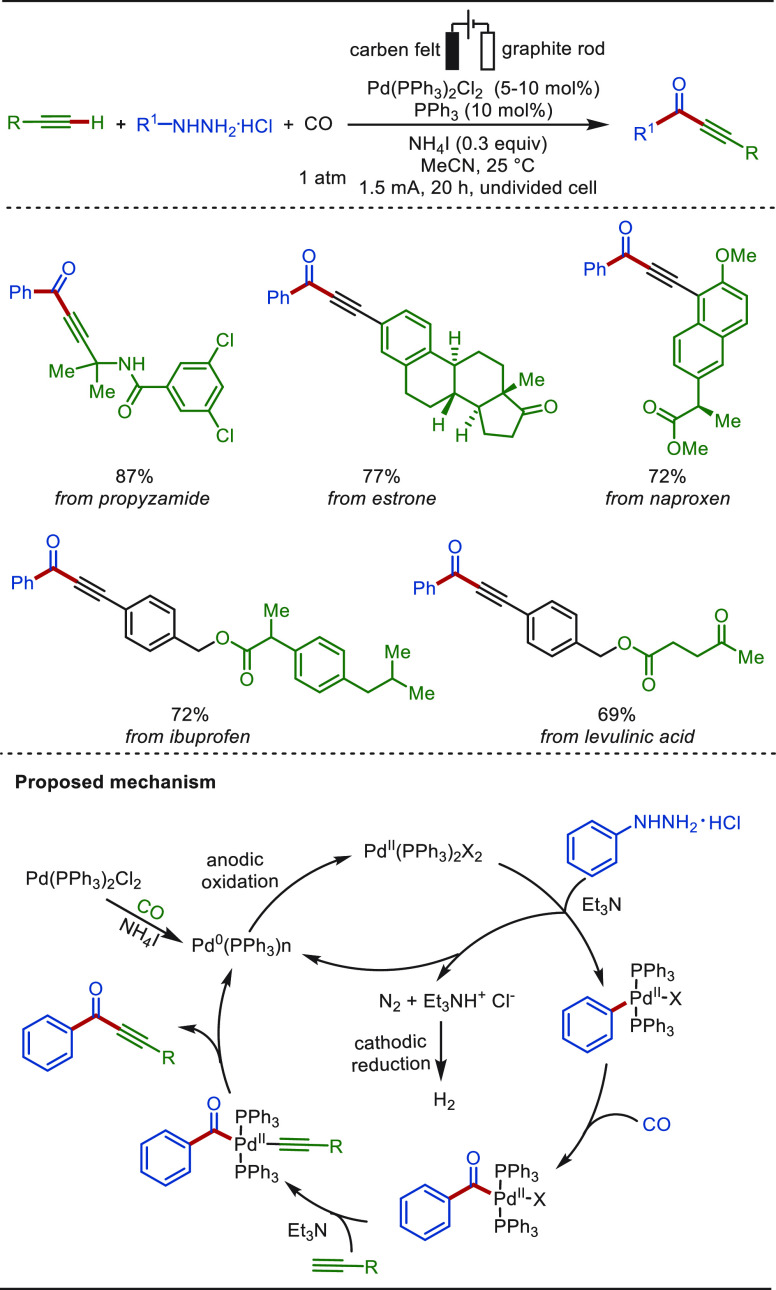

In 2021, by employing arylhydrazines instead of amines, Lei and co-workers further accomplished the electrochemical palladium-catalyzed oxidative carbonylation of alkynes to synthesize ynones, which is an alternative supplement of the carbonylative Sonogashira–Hagihara reaction (Scheme 46).295 The LSF of bioactive molecules deriving from propyzamide, estrone, naproxen, ibuprofen, and levulinic acid afforded the corresponding ynones in excellent yields. Similarly, the process occurs via a proposed palladium(0)/palladium(II) regime, and the use of current as oxidant avoids the explosion hazard of CO.

Scheme 46. Electrochemical Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Sonogashira–Hagihara Carbonylation of Arylhydrazines and Alkynes.

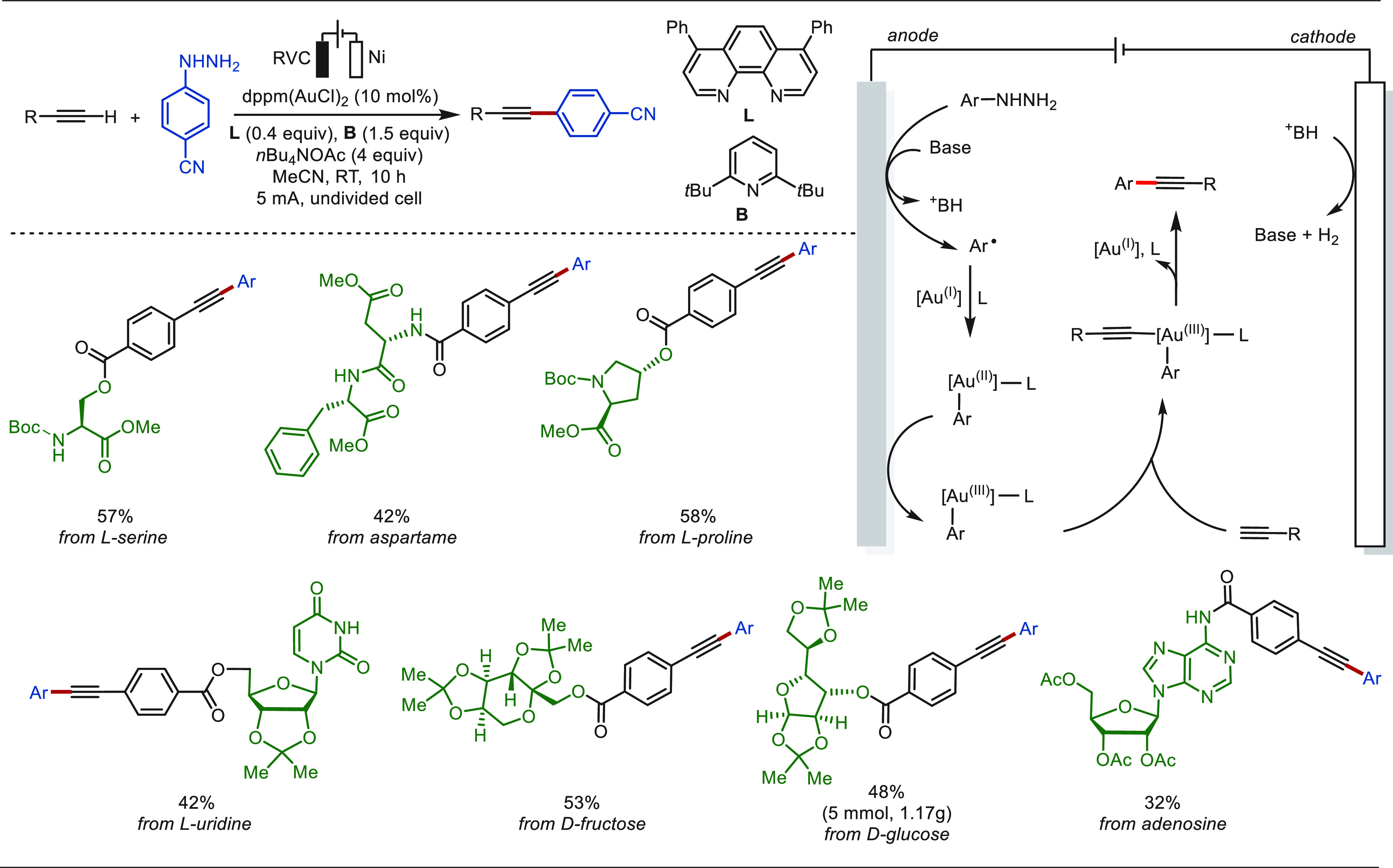

Recently, Xie and co-workers disclosed a electrochemical gold-catalyzed C(sp)–C(sp2) coupling reaction between structurally complex alkynes and arylhydrazines (Scheme 47).296 This approach exhibited broad functional group tolerance without the use of chemical oxidants. The robustness of this approach was further illustrated by the efficient late-stage modification of a variety of alkynes tethered to biomolecules. Mechanistic studies suggested the anodic oxidation of aromatic hydrazine to generate an aryl radical, which recombined with gold(I) and underwent further anodic oxidation to form the Ar–Au(III) species for subsequent σ-activation of alkynes.

Scheme 47. Electrochemical Gold-Catalyzed Oxidative C(sp)–C(sp2) Coupling.

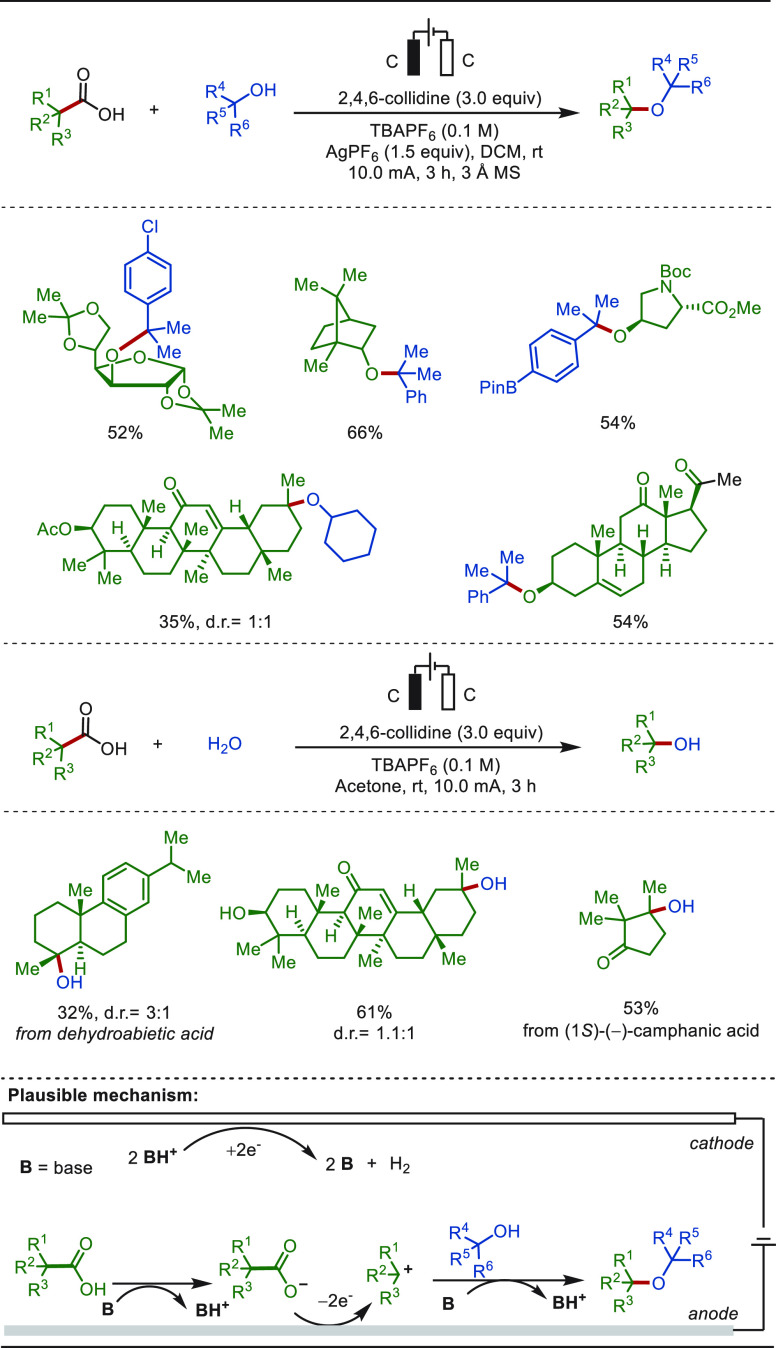

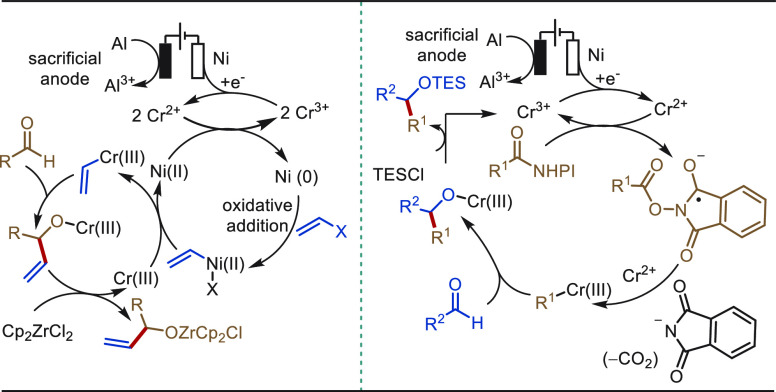

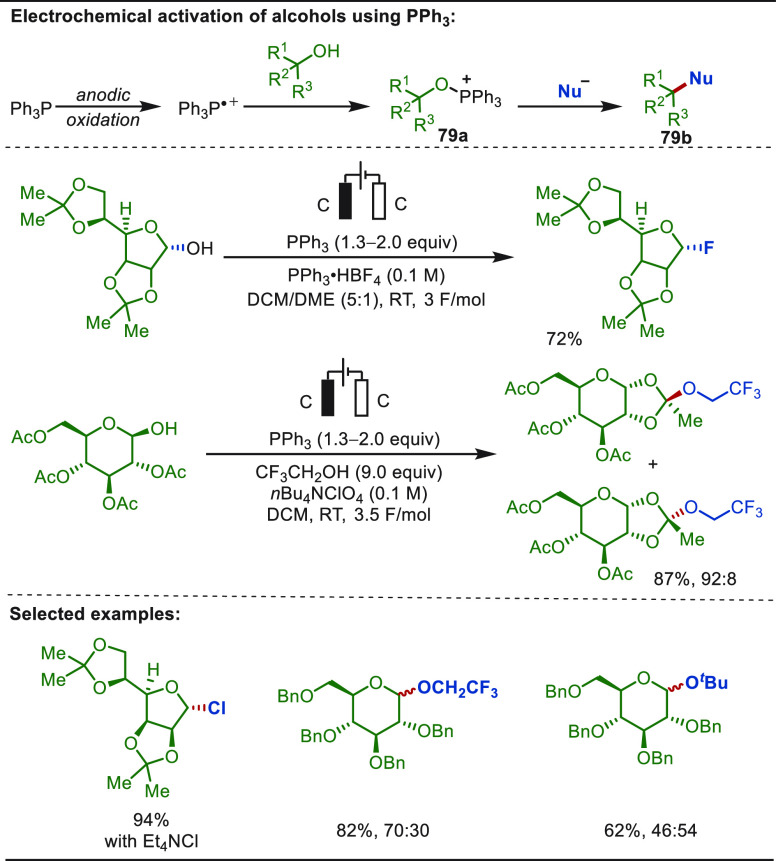

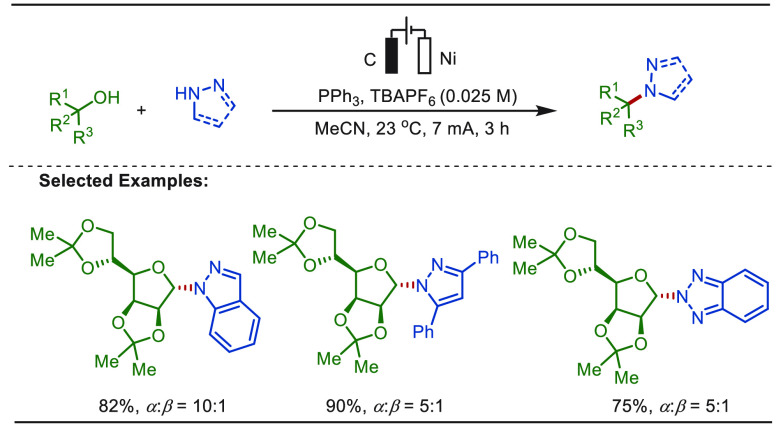

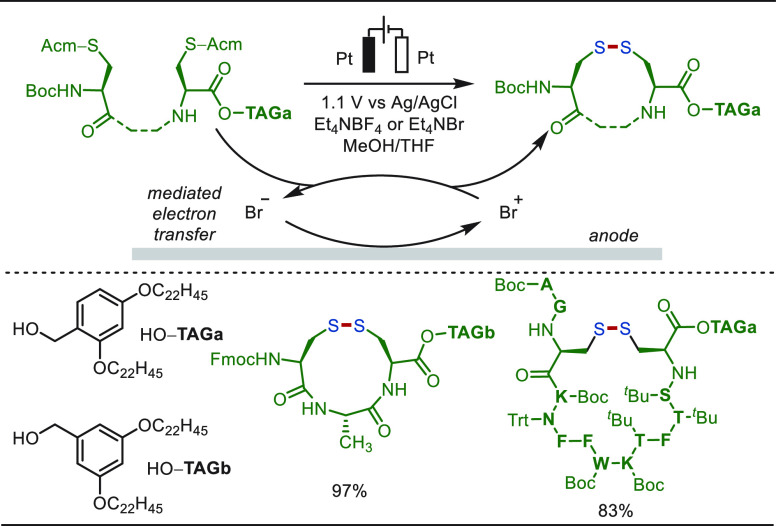

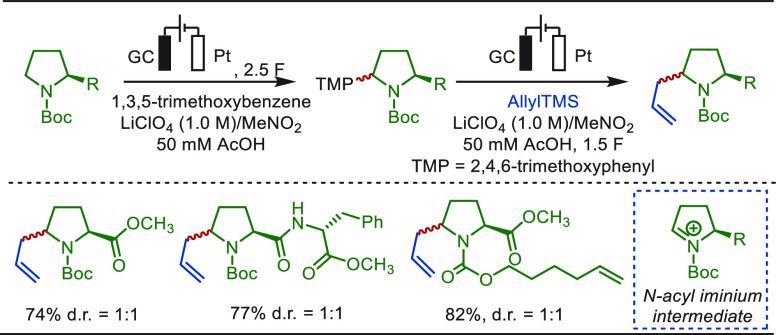

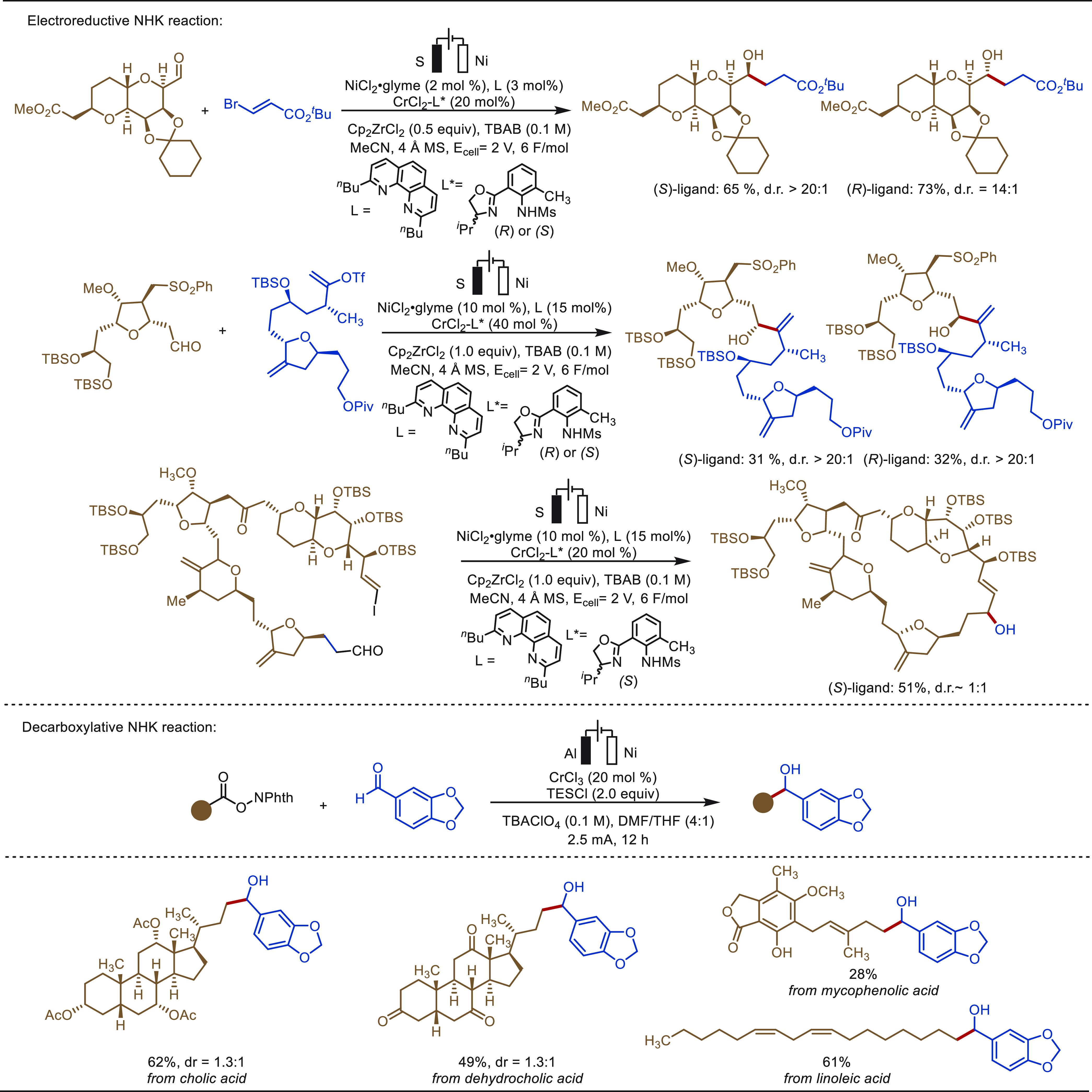

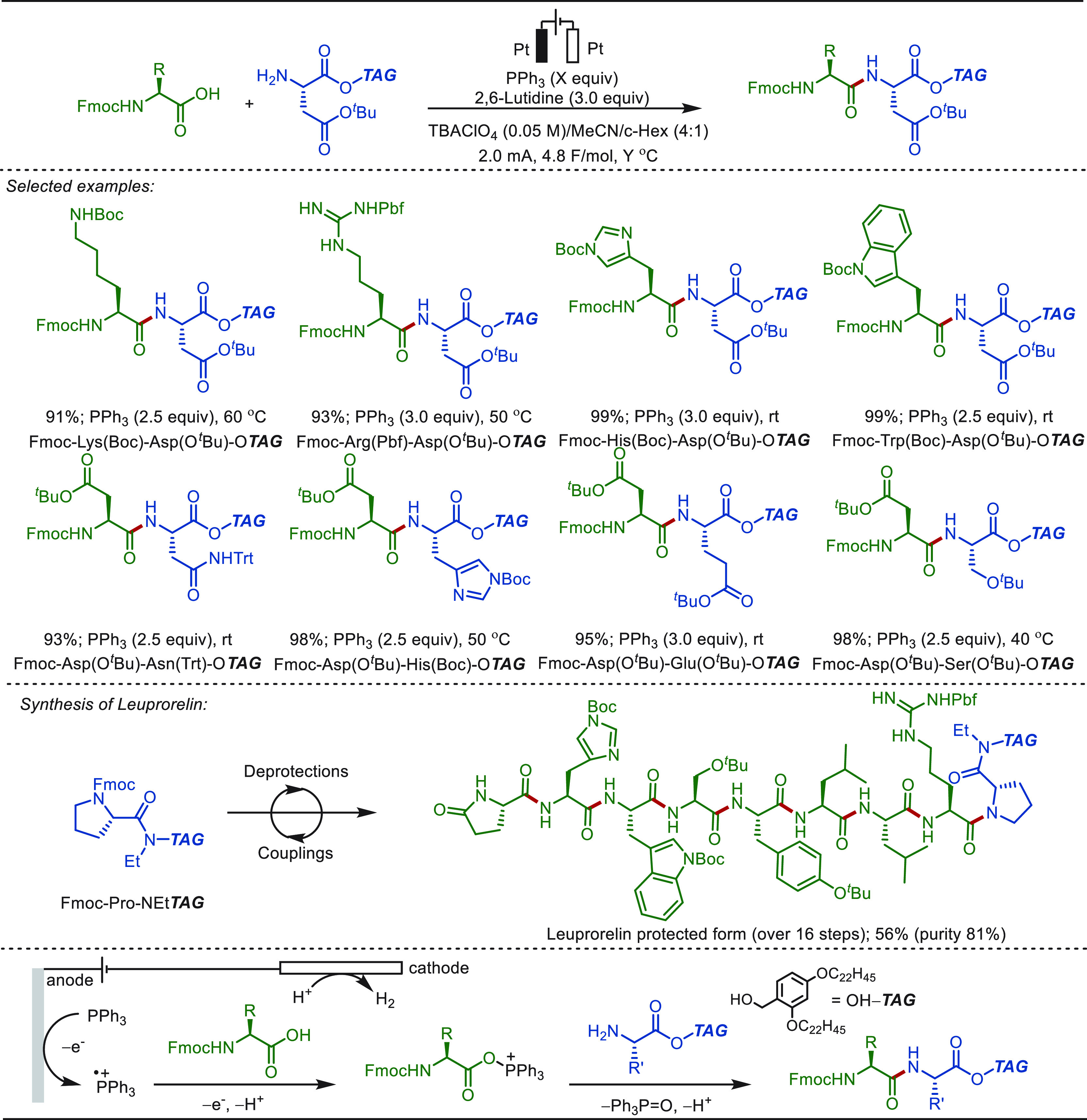

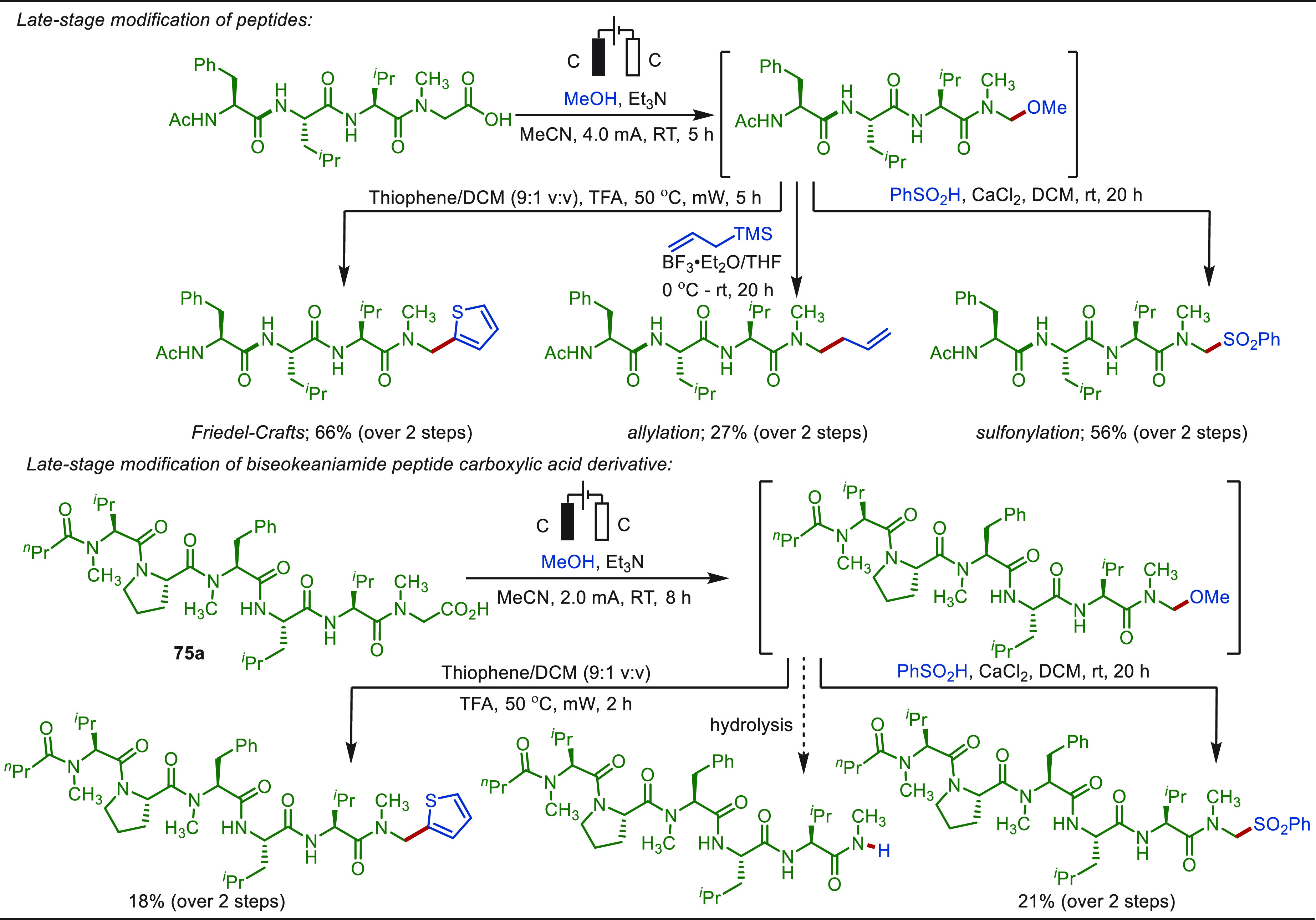

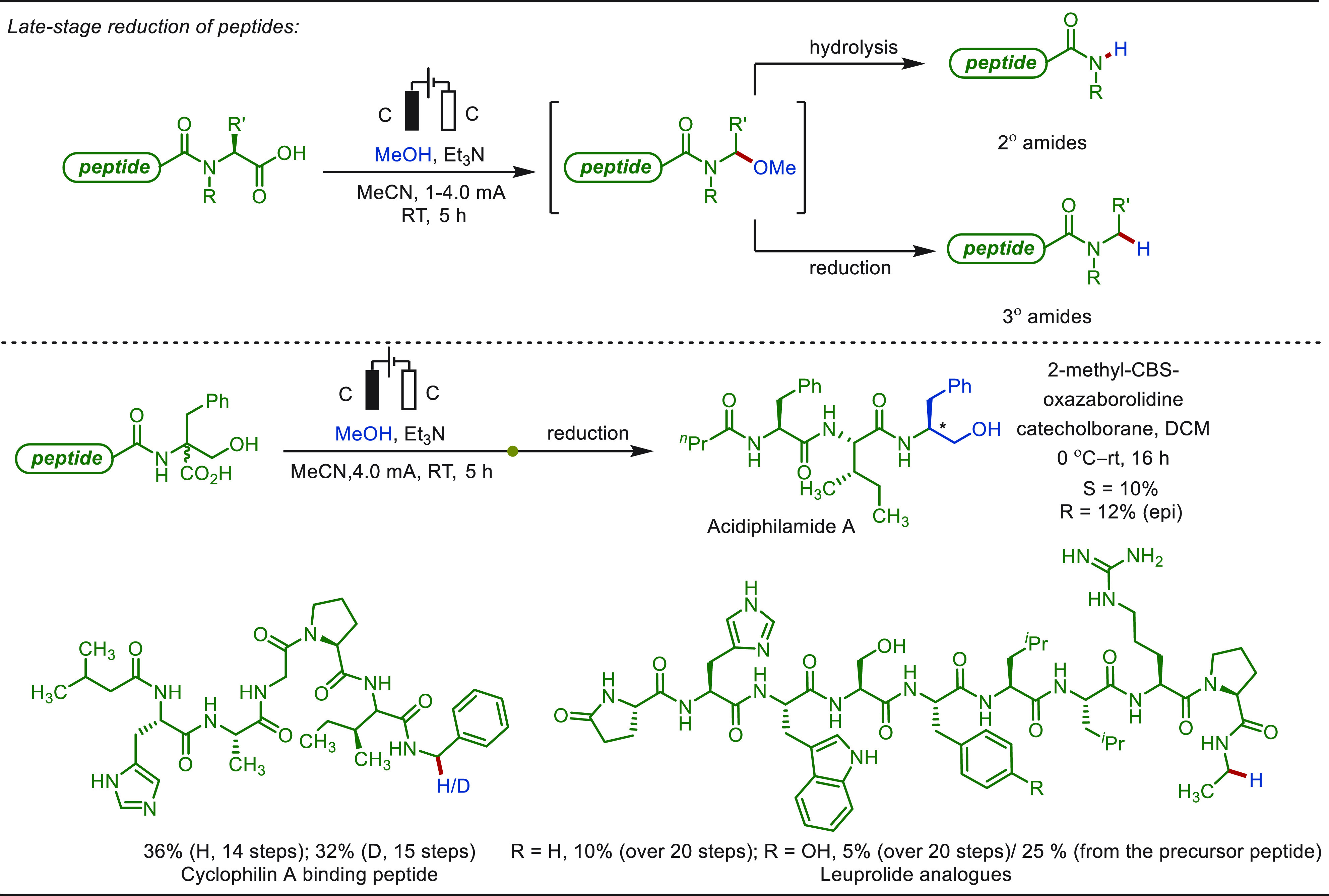

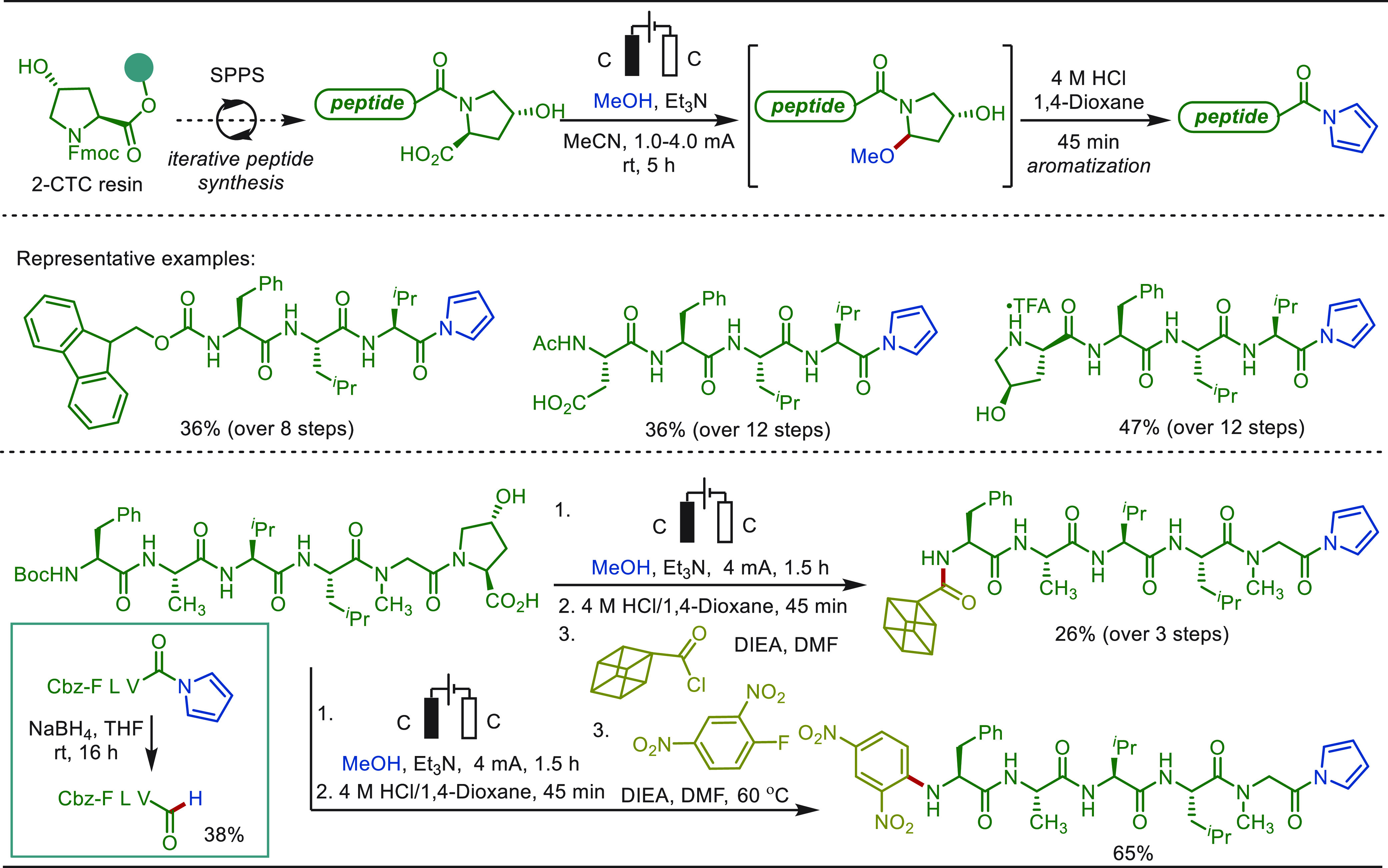

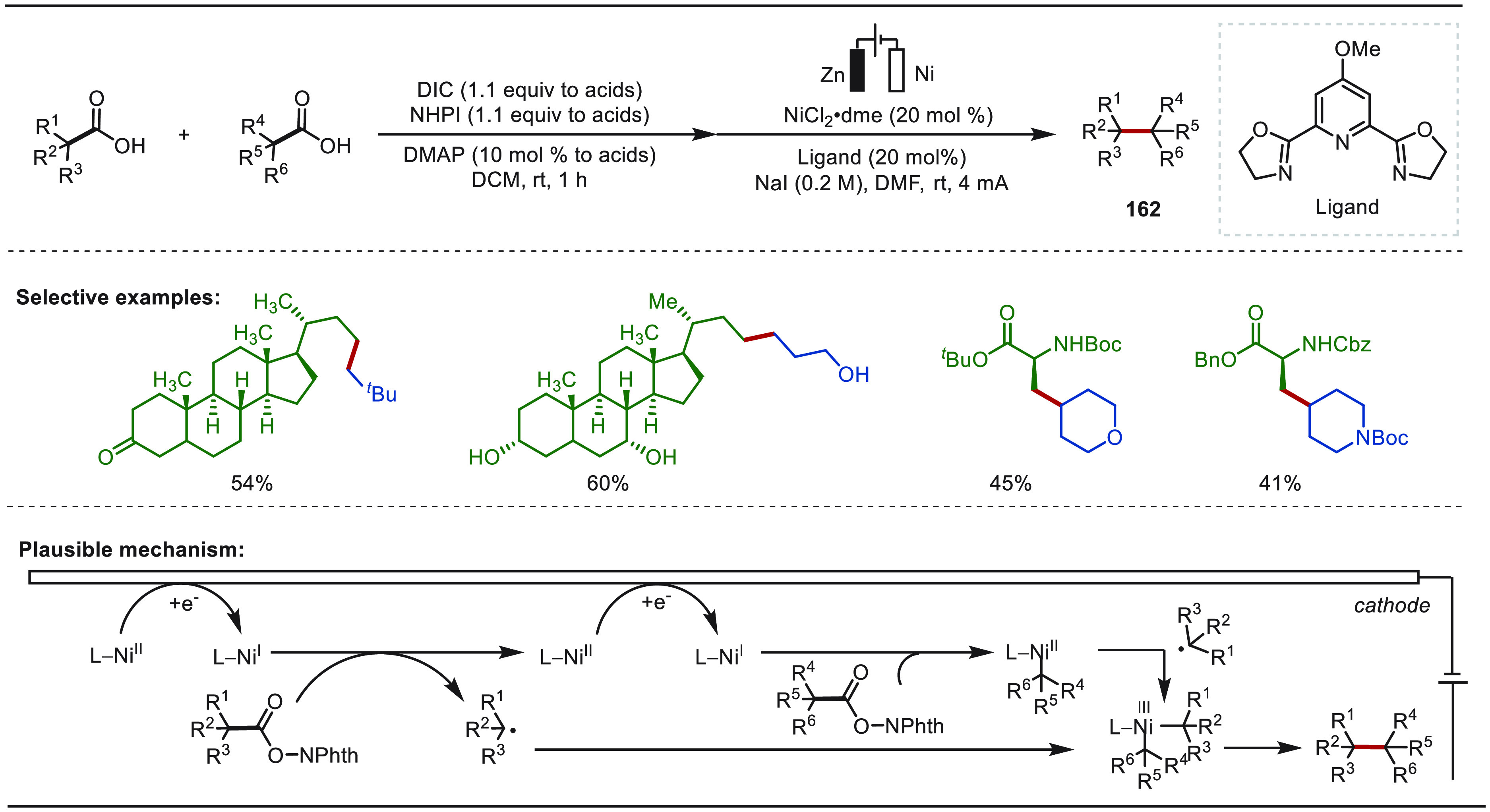

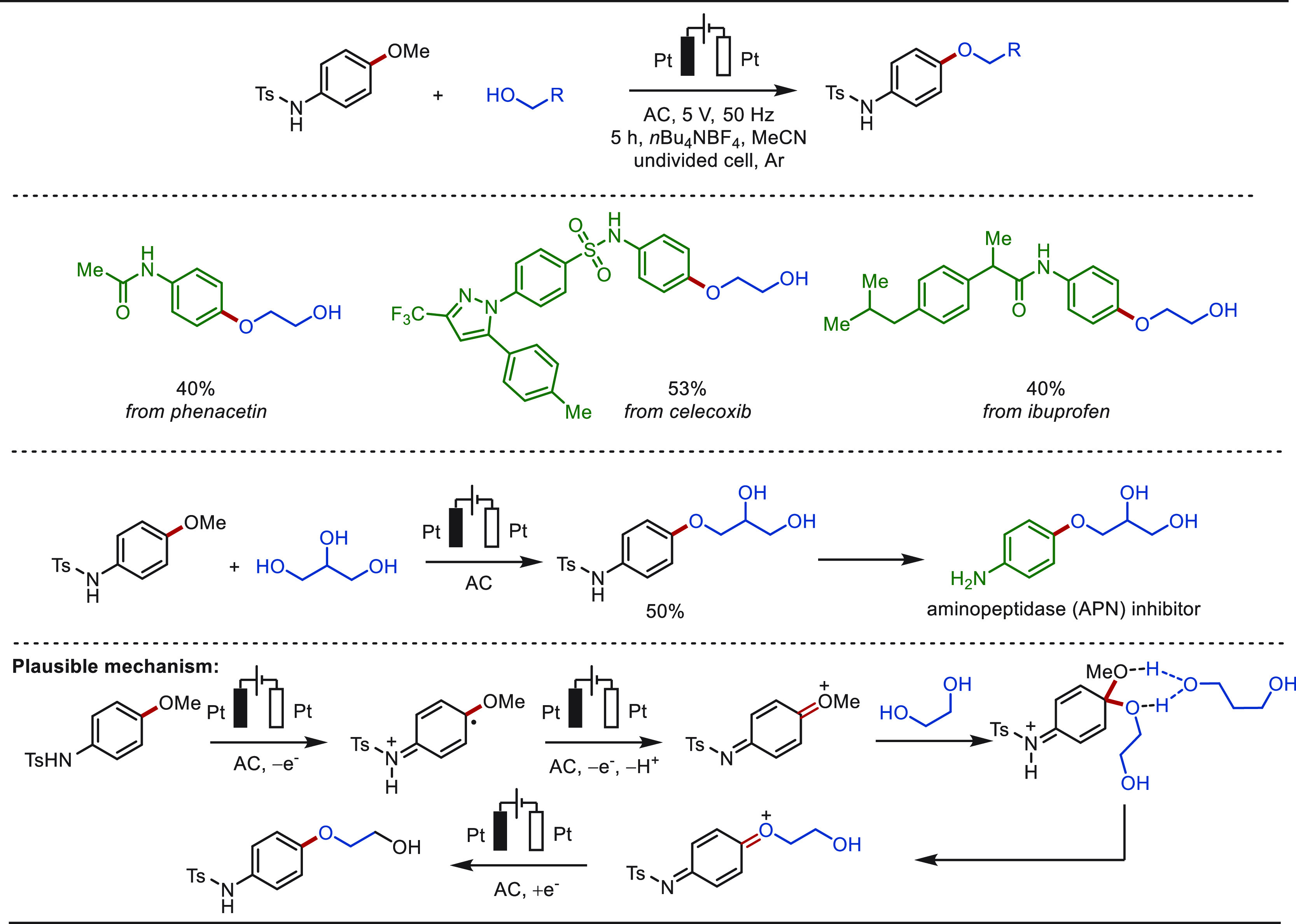

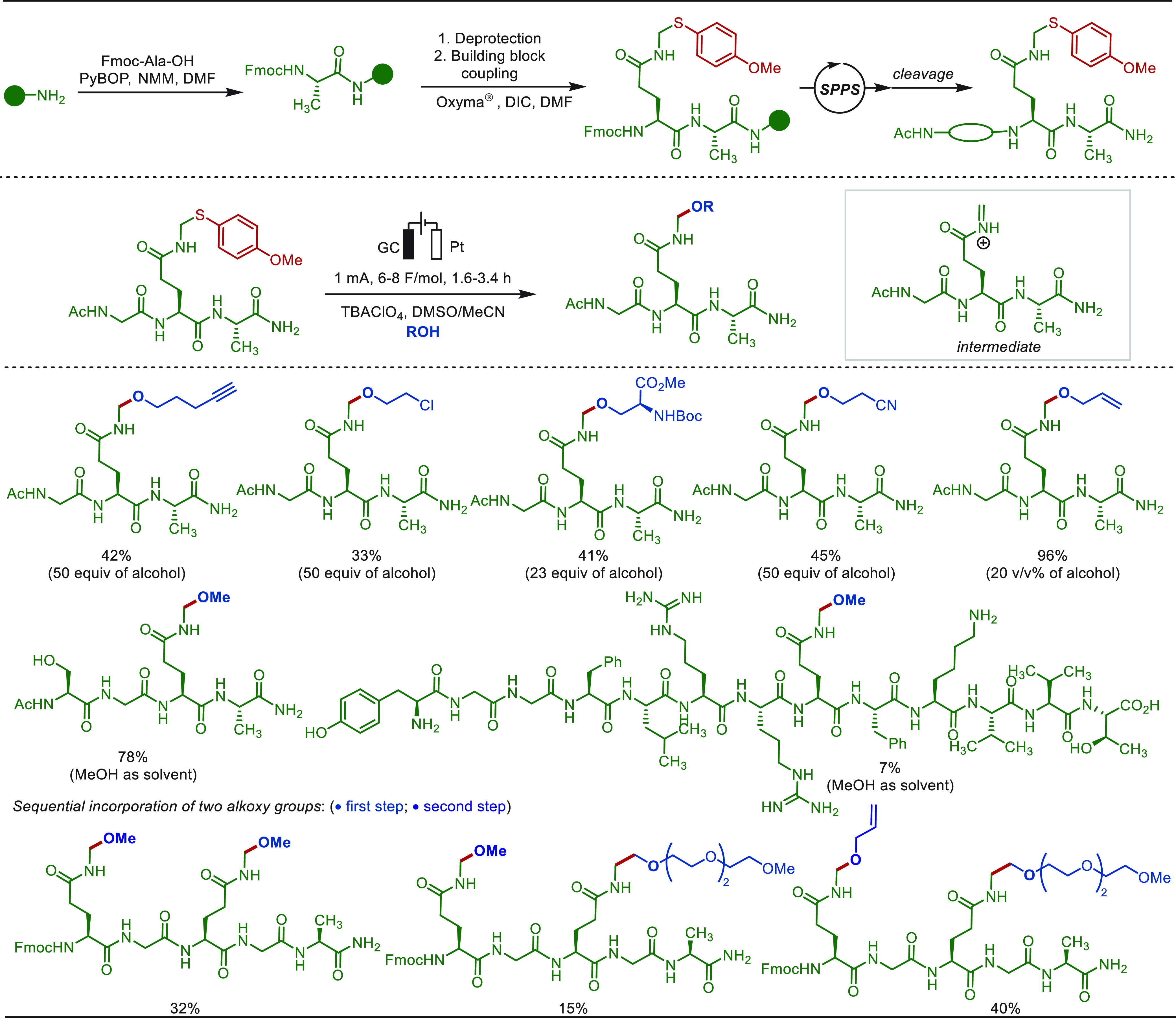

3. eLSF of Functional Groups

Electrocatalytic interconversion of common organic functionalities bears unique potential for the advancement of organic synthesis. Interestingly, owing to their robust and mild conditions, these approaches are often adopted for the late-stage derivatization of complex organic molecules. In the following section, we will discuss the progress in the area of electrochemical late-stage functional group modification strategies.

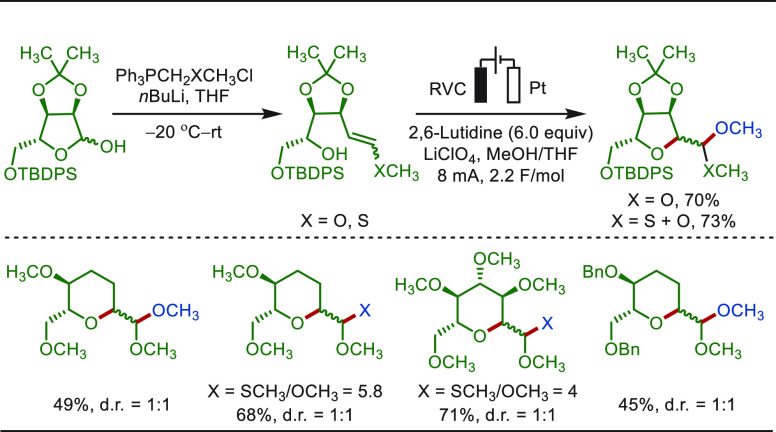

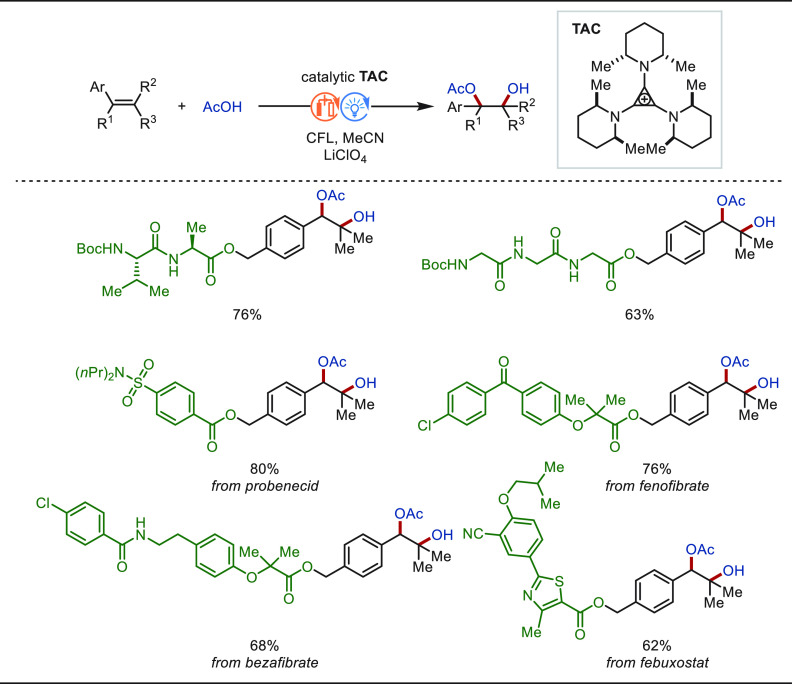

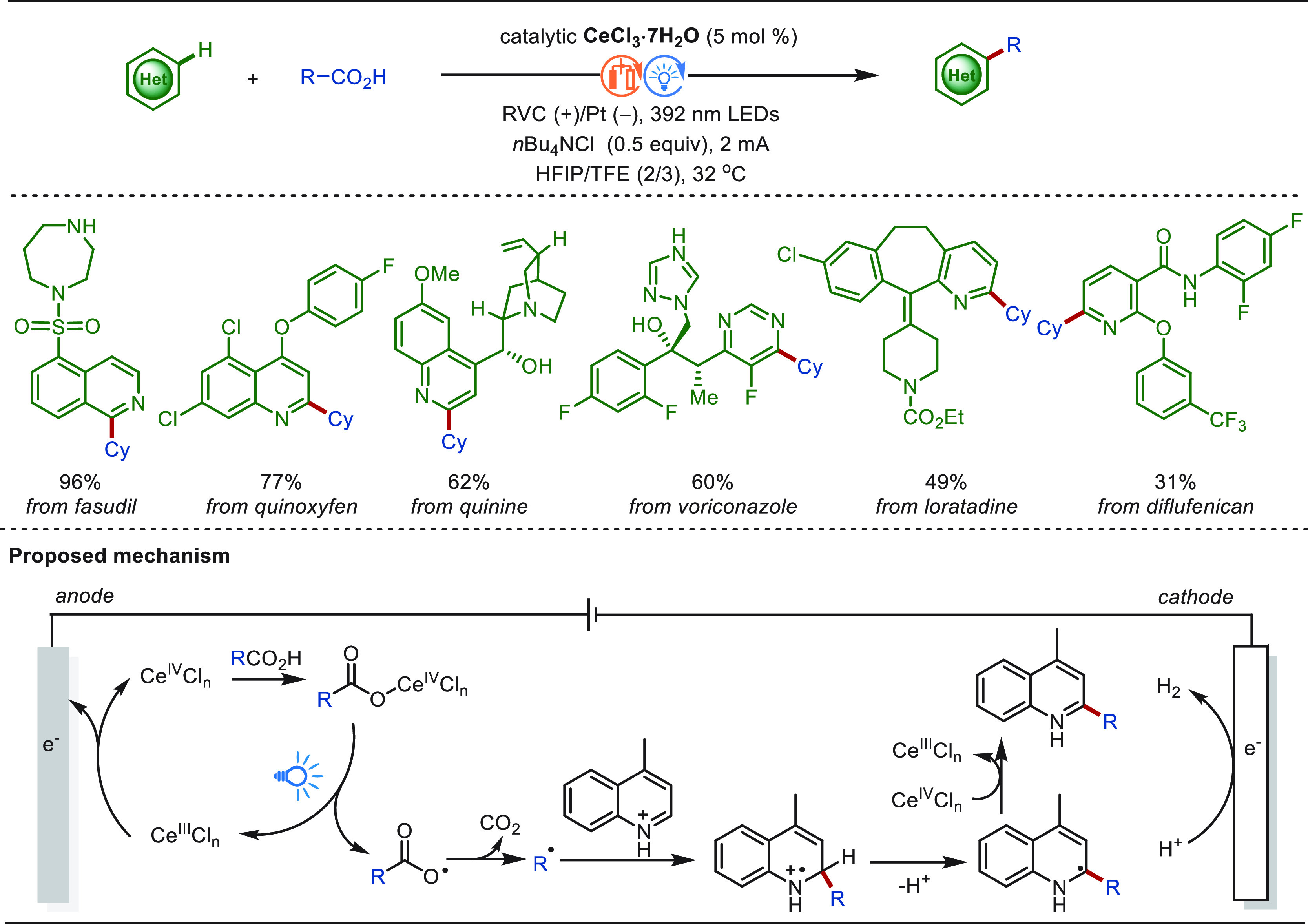

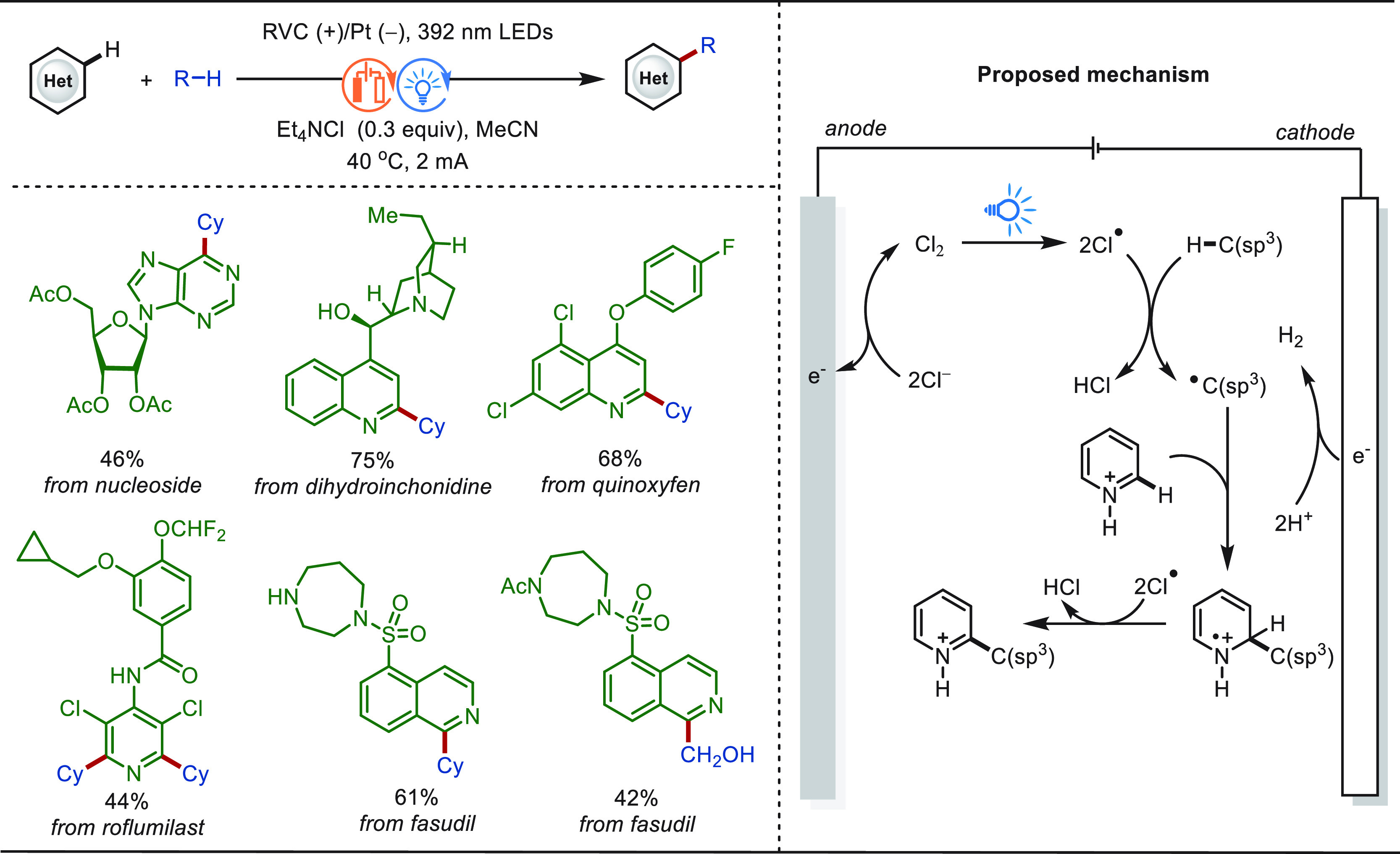

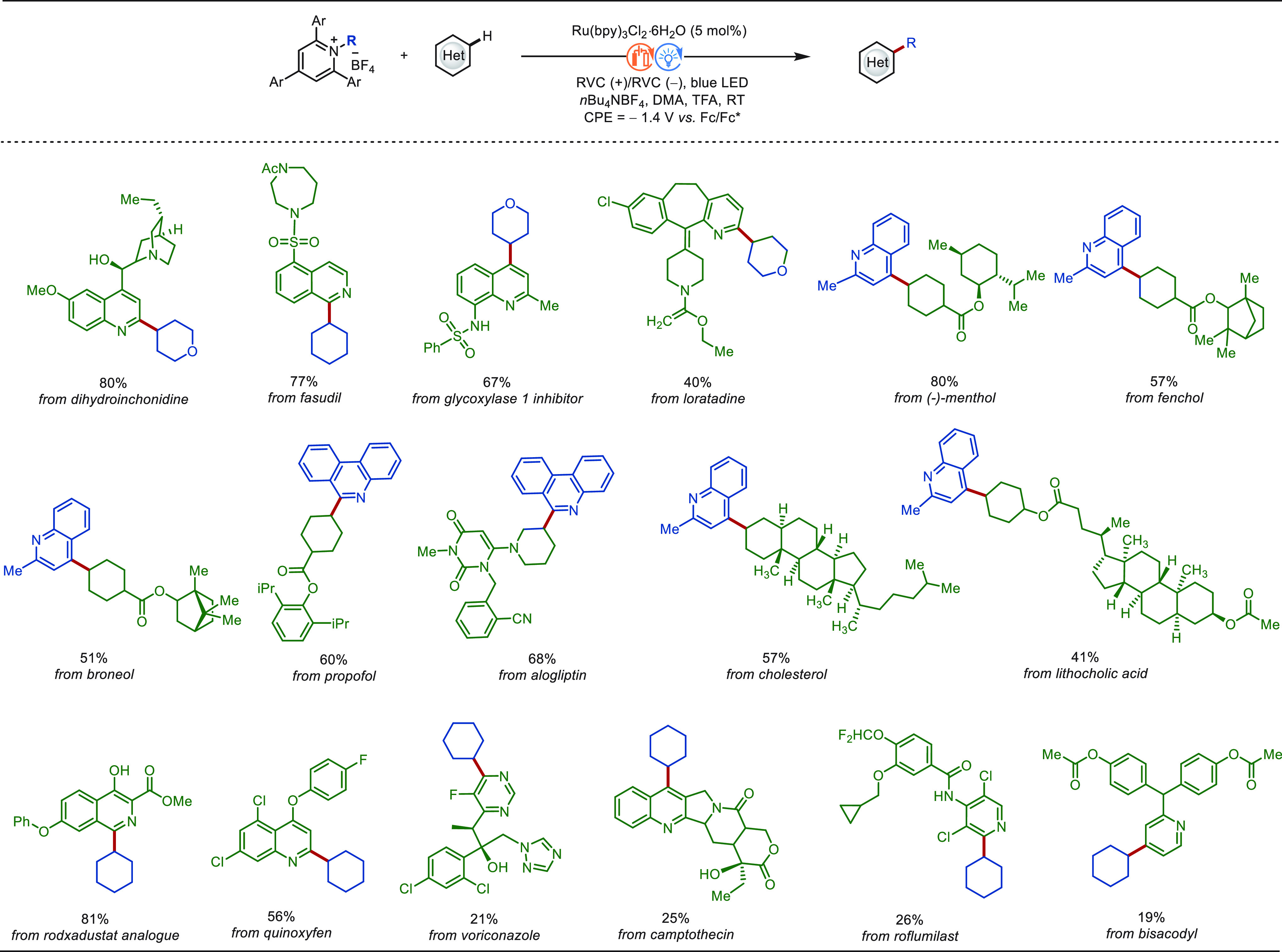

3.1. eLSF of Alkenes and Alkynes

Olefins are prevalent structural motifs in various biologically relevant molecules and natural products.297,298 These moieties are quite reactive and are often garnered for incorporating new functional groups in the molecule.299−306 Synthetic manipulation of these substructures is thus used as a versatile strategy for late-stage functionalization reactions.

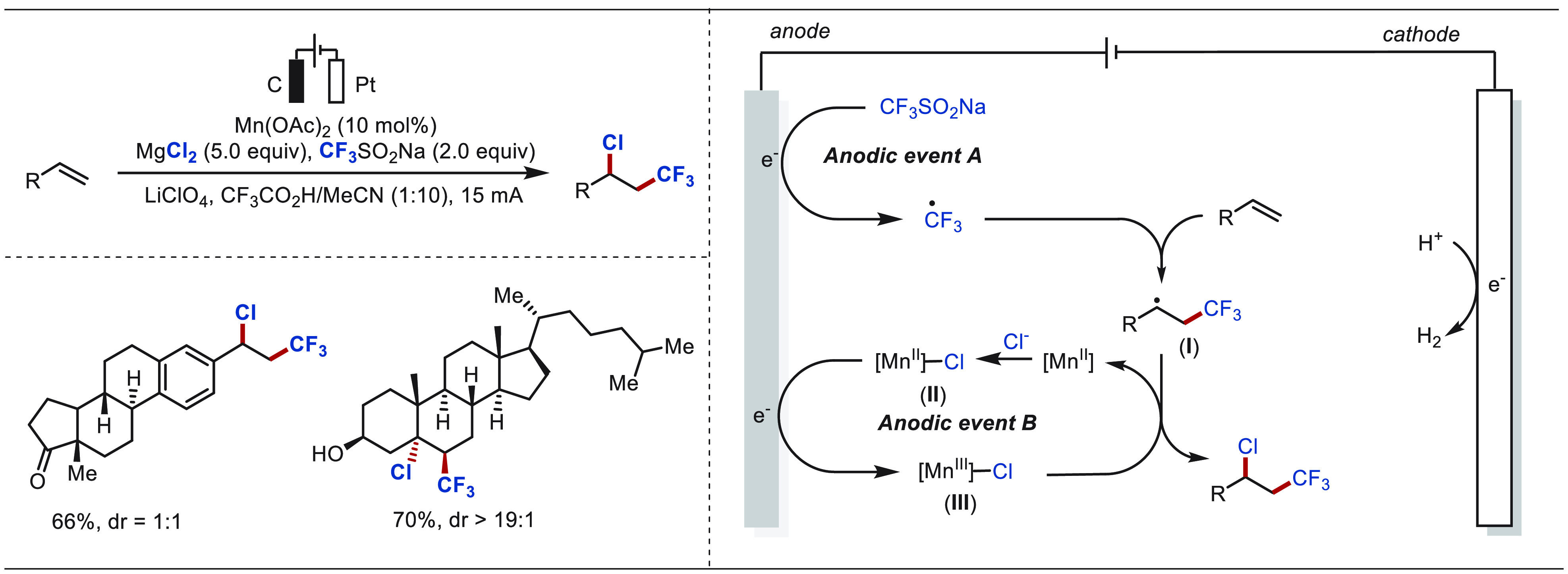

The Lin group has done great contributions in the field of metallaelectro-catalyzed functionalization of alkenes.301,302,304−309 In 2018, Lin described an electro-oxidative heterodifunctionalization of olefins enabled by anodic oxidation of CF3SO2Na (Scheme 48).307 The interception of the anodically generated trifluoromethyl radical with a terminal olefin formed a secondary alkyl radical intermediate, which was trapped with a chloride radical to form the heterodifunctionalized product. The use of catalytic Mn(OAc)2 assisted the electrochemical process through the formation of an alleged Mn(III)-Cl radical chlorinating agent, which helped the chloride radical recombination step. This anodically coupled electrocatalytic process was exploited for the late-stage functionalization of several natural product analogues.

Scheme 48. Electro-oxidative Chlorotrifluoromethylation of Olefins.

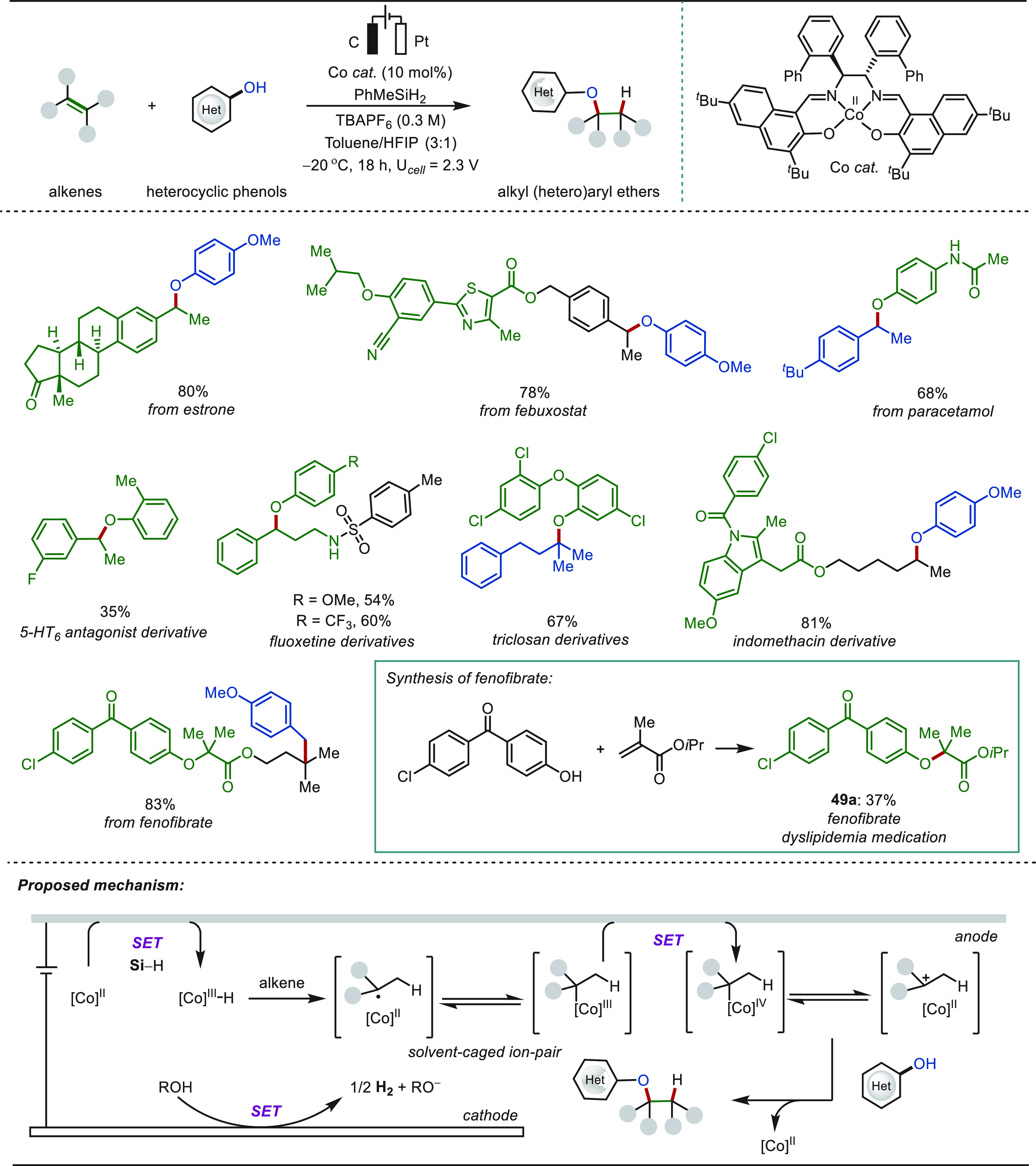

Later, a cobalt-salen-catalyzed hydroetherification strategy was demonstrated by Kim and Shin combining MHAT and anodic oxidation (Scheme 49).310 Generally, in MHAT strategies, weak nucleophiles exhibit poor reactivity owing to the formation of a “solvent-caged radical pair”, which deflates the nucleophilic entrapment process. Anodic oxidation of the caged intermediate detoured the detrimental bimetallic disproportionation pathway and enabled the nucleophilic displacement process. The electrocatalysis involved a plausible cobalt(II/III/IV) pathway for product formation. This versatile strategy was employed for the late-stage hydroetherification of estrone, febuxostat, paracetamol, fluoxetine, triclosan, indomethacin derivatives including many other important organic molecules. The versatility of the hydroetherification strategy was also highlighted through the synthesis of fenofibrate 49a, an oral medication for dyslipidemia.

Scheme 49. Electrochemical Cobalt-Catalyzed Late-Stage Hydroetherification of Olefins.

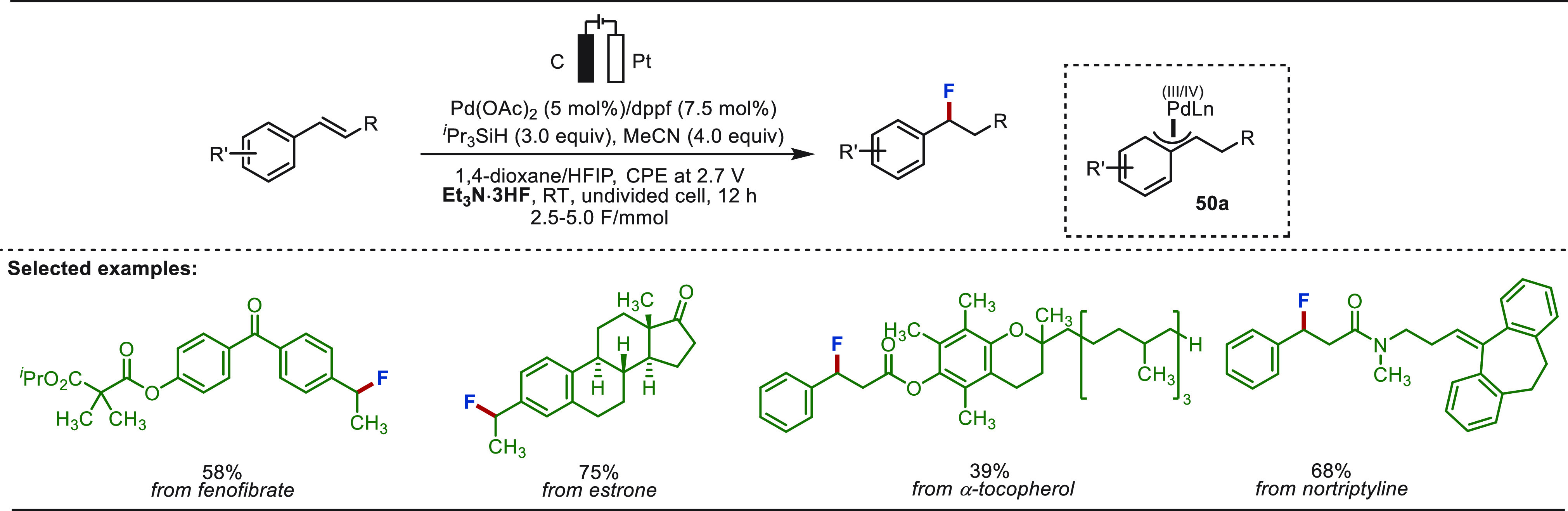

They further illustrated an electro-oxidative palladium-catalyzed approach very recently to realize benzylic fluorinations in a straightforward manner using Et3N·3HF as a nucleophilic fluorinating agent (Scheme 50).311 Similar to the prior findings, this strategy operated through a metal hydride intermediate, which after migratory insertion with the olefin formed a high-valent η3-benzylpalladium intermediate. This intermediate under electro-oxidative conditions guided a nucleophilic displacement reaction with the nucleophilic fluorinating agent. This hydrofluorination strategy employed the dppf ligand and silane as the hydride source. The formation of intermediate 50a was confirmed by cyclic voltammetry studies. This approach was employed for the selective benzylic fluorination of biologically relevant nortriptyline, fenofibrate, estrone, and α-tocopherol derivatives.

Scheme 50. Electrochemical Palladium-Catalyzed Late-Stage Hydrofluorination of Olefins.

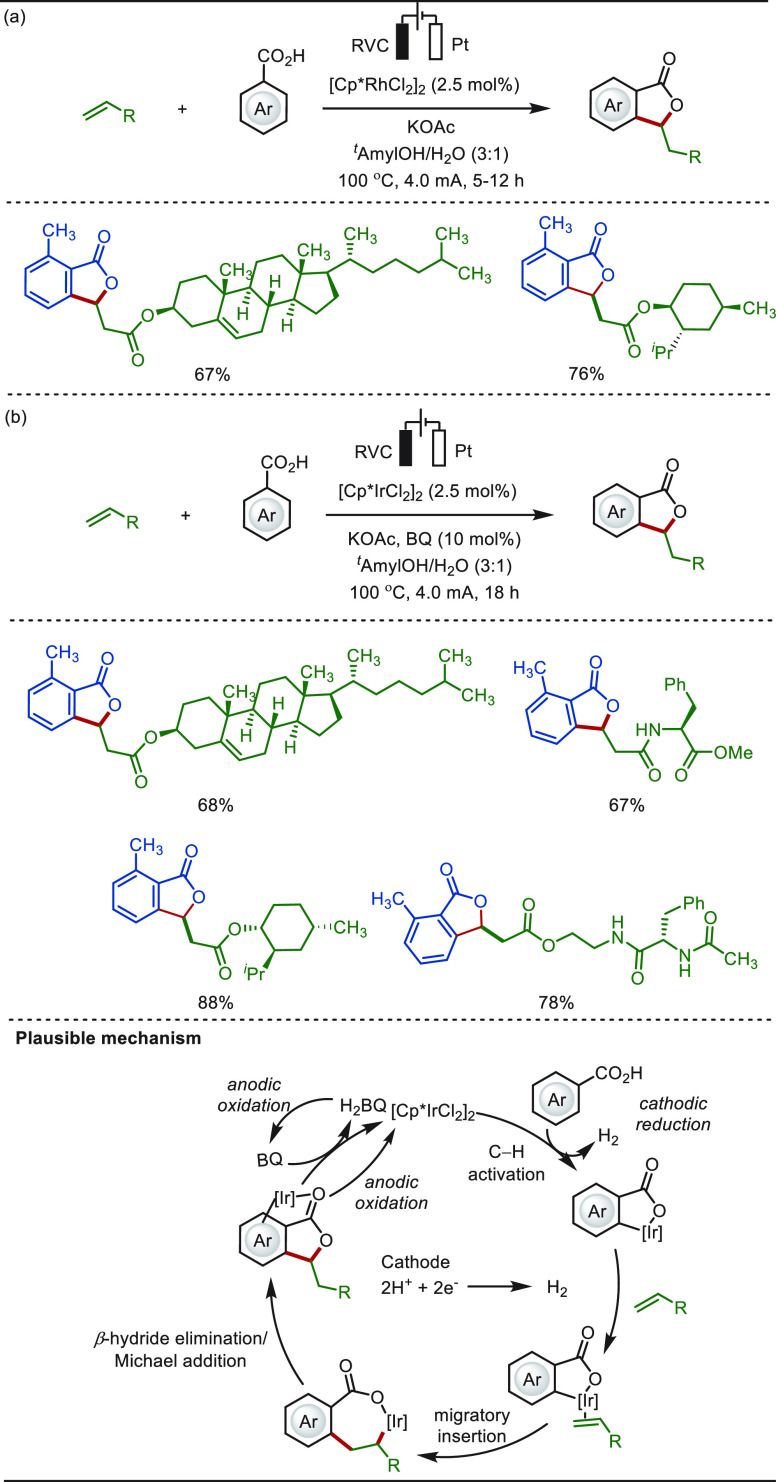

In 2018, Ackermann reported the versatile electro-oxidative olefination/annulation approach under rhodium and iridium catalysis, respectively (Scheme 51).312,313 These chemo- and site-selective strategies harvested electricity as the renewable terminal oxidant, converting easily accessible aromatic carboxylic acids to synthetically meaningful phthalides. Various acrylate analogues embracing naturally occurring complex terpenoids and amino acids were compatible to the reaction conditions generating respective phthalides in high yields. While the rhoda-electrocatalyzed approach relied on direct anodic oxidation to regenerate the rhodium(III)-catalyst, catalytic amounts of benzoquinone redox-mediator were necessary to promote an iridium-catalyzed transformation.

Scheme 51. Electro-oxidative Late-Stage Annulation of Biologically Relevant Olefins.

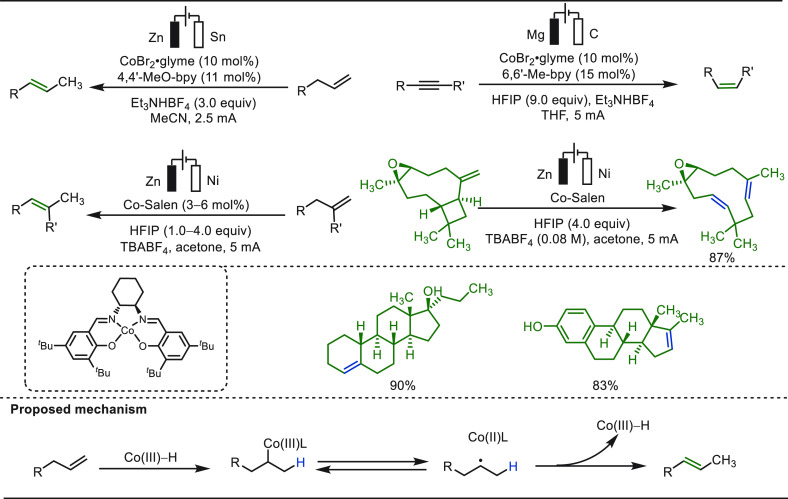

The controlled isomerization of readily available terminal alkenes or reduction of alkynes is an effective and practical strategy to access internal olefins.314−319 Recently, Baran and co-workers established an electroreductive Co-catalyzed regioselective olefin isomerization strategy harnessing transition-metal hydride intermediates (Scheme 52).320 The cathodic reduction of high-valent Co(III)-species formed low-valent Co(I)-species, which can effectively reduce protons to form a Co(III)–H intermediate. This cobalt hydride intermediate when reacted with terminal olefins and alkynes, it selectively transformed them into corresponding internal olefins and Z-olefins, respectively. This simple and straightforward method proved to be applicable for the modification of a variety of substrates including the late-stage derivatization of structurally complex organic architectures.

Scheme 52. Electroreductive Cobalt-Catalyzed Late-Stage Functionalization of Olefins and Alkynes.

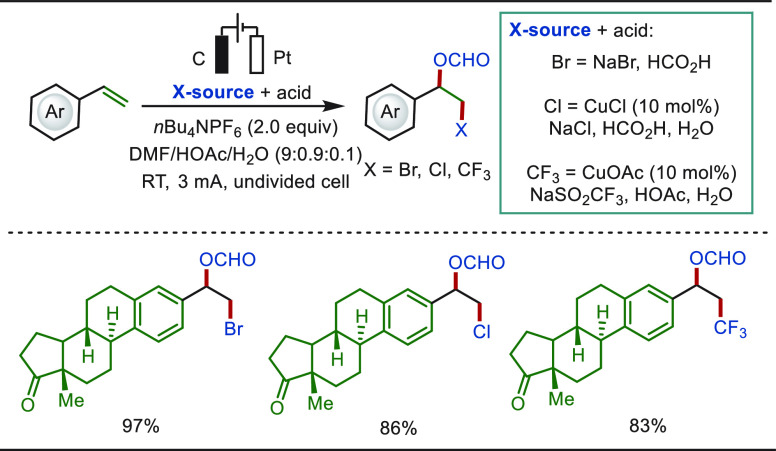

The electrochemical functionalization of alkenes under transition-metal-free conditions has also been extensively studied. In 2019, Fang and Hu reported a scalable difunctionalization of olefins harnessing anodic oxidation, in which the reaction presumably proceeded through a nucleophilic addition of dimethylformamide to the benzylic carbocation, formed after anodic oxidation of a benzylic radical (Scheme 53).321 This approach allowed for the bromination, chlorination, and trifluoromethylation-formyloxyation of naturally occurring steroids using bench-stable NaBr, NaCl, and NaSO2CF3 as corresponding radical sources.

Scheme 53. Late-Stage Difunctionalization of Steroid Derivatives.

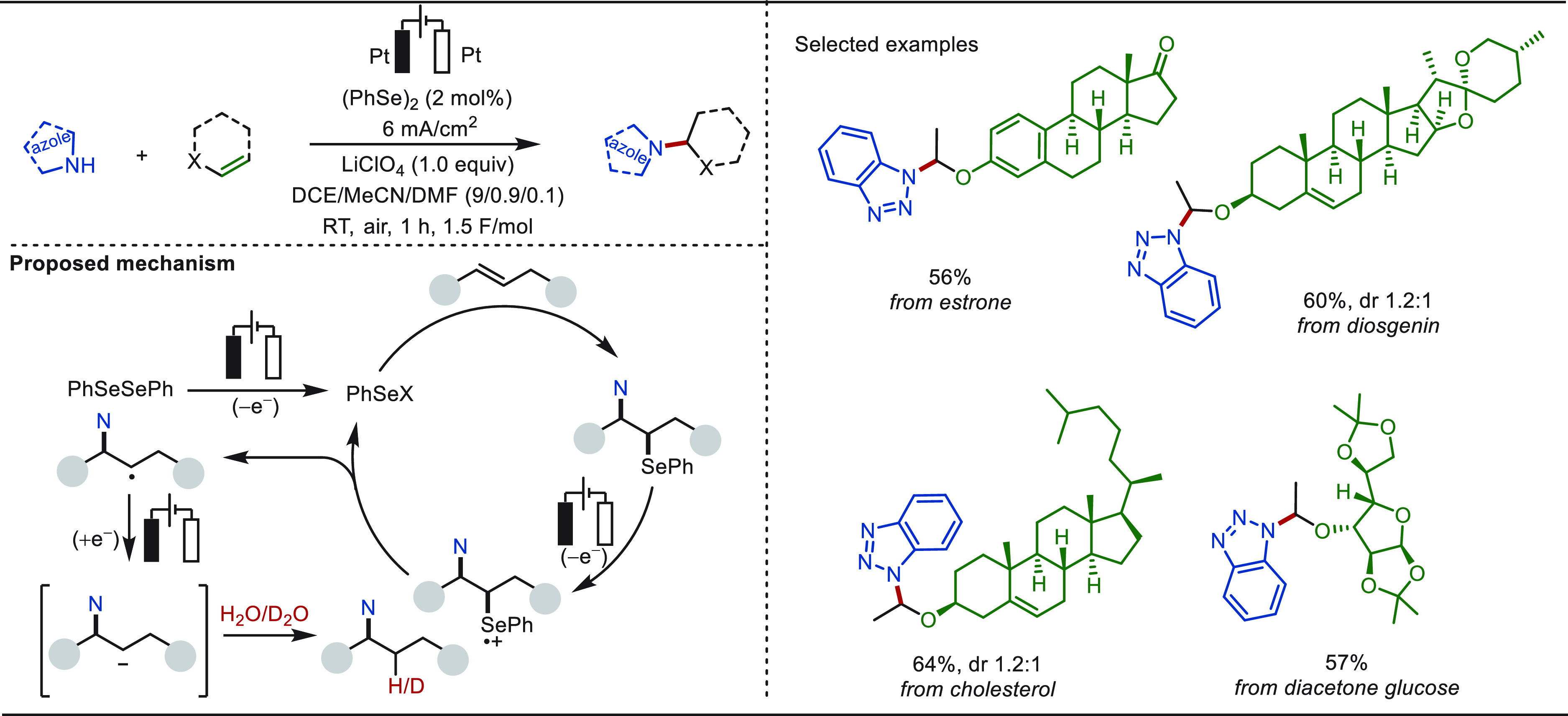

Recently, Xu and Zeng demonstrated a versatile electroseleno-catalytic hydroazolylation of olefins in the absence of external oxidants (Scheme 54).322,323 Electrochemical conditions acetivated the diselenide catalyst to PhSe+ or PhSe·, which triggered an electrophilic activation of the olefin followed by a nucleophilic addition with the azole substrate. The difunctionalized product then realized an anodic oxidation induced deselenylation generating the hydroaminated product. Deuterium labeling studies revealed the significance of the cathode in this transformation, which assisted in the formation of a carbanion. The role of the cathode was further concluded by executing the reaction in a divided cell, in which the substrate at the cathodic chamber was consumed and no product formation was observed in the anodic chamber. This electroseleno-catalyzed approach enabled the diversification of estrone, cholesterol, diosgenin, and diacetone glucose analogues with good yields.

Scheme 54. Electrochemical Selenium-Catalyzed Late-Stage Hydroazolation of Olefins.

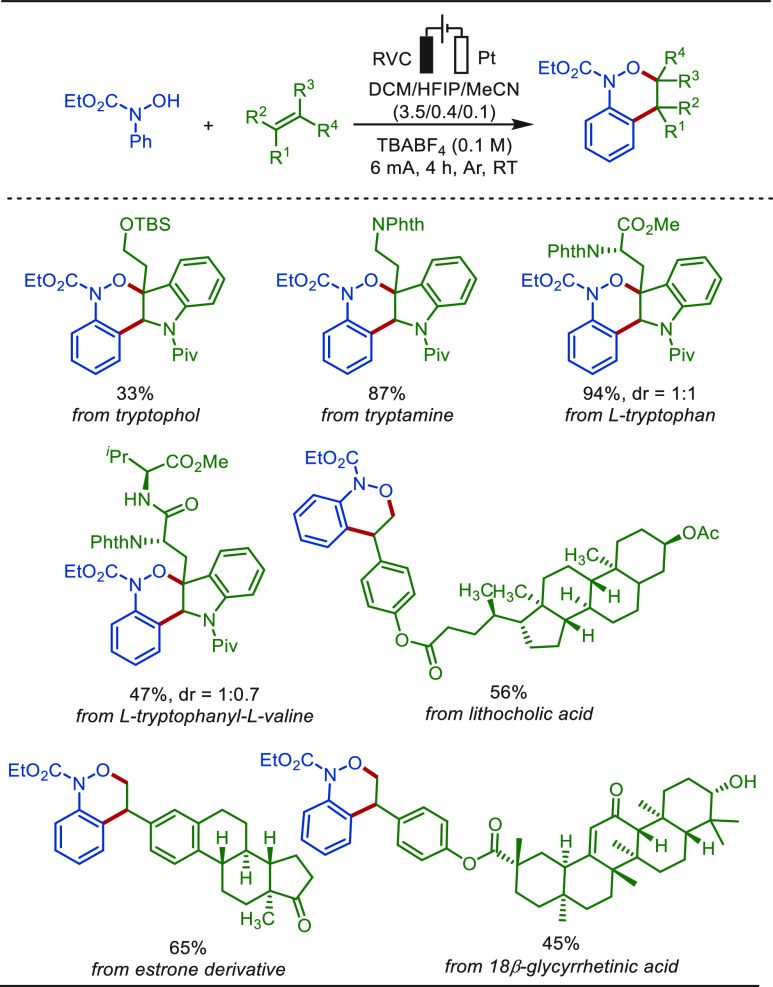

In 2021, Han reported a (4 + 2)-annulation strategy for the construction of benzo[c]-[1,2]oxazines in good yields (Scheme 55).324 Anodic oxidation of hydroxamic acid produced an amidoxyl radical intermediate. This intermediate reacted with the olefin substrate, constructing the oxazine core structures in decent yields. This mild, external oxidant-free approach was used to execute late-stage functionalization of tryptophol, tryptamine, tryptophan and its analogous peptides, and various steroid derivatives in high efficacy.

Scheme 55. Electrochemical Late-Stage [4 + 2] Annulation of Olefins with Hydroxamic Acid.

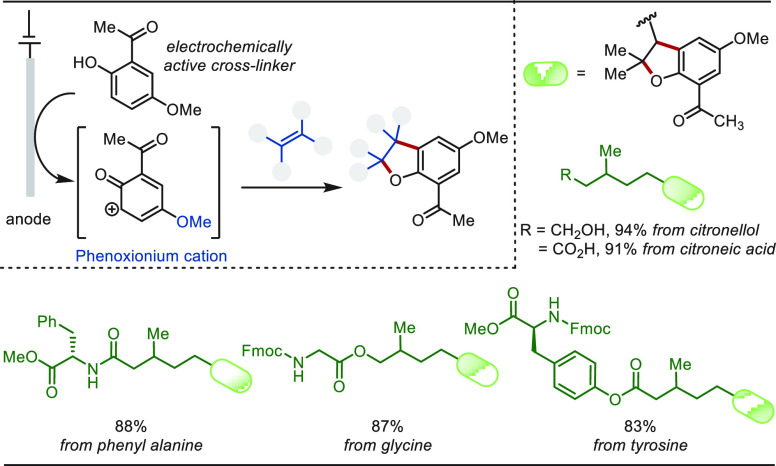

Anodic oxidation-based electrochemical functionalization of olefins was also transcended for a late-stage labeling of biologically relevant olefins (Scheme 56).325 An oxidizable phenol derivative was used as the cross-linker, which upon anodic oxidation formed a phenoxionium cation. This phenoxionium intermediate underwent a facile [3 + 2] addition with the olefin to form a fluorescent active dihydrobenzofuran moiety. The electrochemical labeling approach was able to cross-link citronellol, citroneic acid, and amino acid derivatives with high efficacy.

Scheme 56. Late-Stage Electrochemical Labelling of Biologically Relevant Olefins.

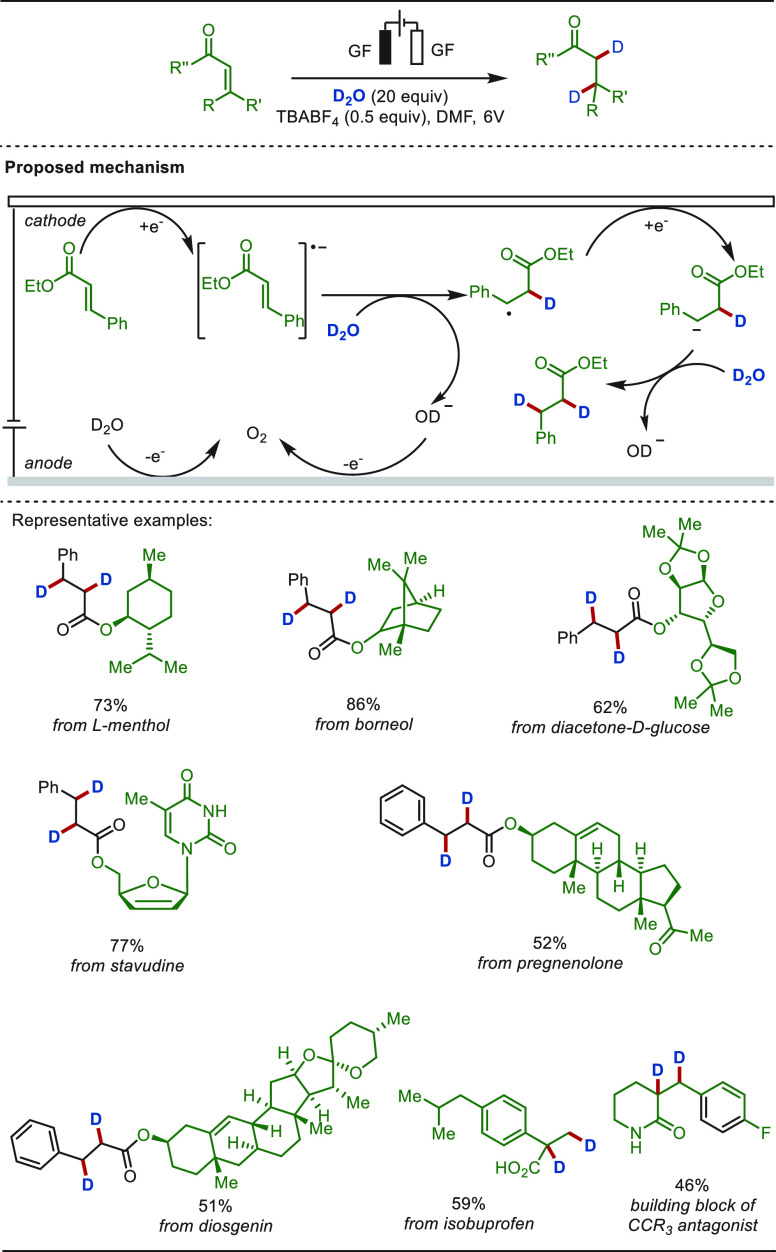

Late-stage olefin functionalizations are not limited to electro-oxidative approaches. Indeed, electroreductive functionalizations of olefins are gaining significant momentum.326 In this context, Cheng reported selective electroreductive deuteration of α,β-unstaurated carbonyl compounds using D2O as the deuterium source (Scheme 57). This electroreductive approach used graphite-felt as the cathode as well as the anode and operated in the absence of an external catalyst, and thus obviated the need of stoichiometric metallic reductants unlike prior examples. An oxygen evolution was observed at the anode, confirmed using isotopically labeled water (H218O), which regulated the need of an additional reductant along with maintaining the pH of the medium during the process. This simple and versatile deuteration method exhibited tremendous potential enabling the late-stage deuteration of a large variety of biologically relevant molecules and pharmaceuticals.

Scheme 57. Electroreductive Late-Stage Hydrogenation of Olefins with D2O.

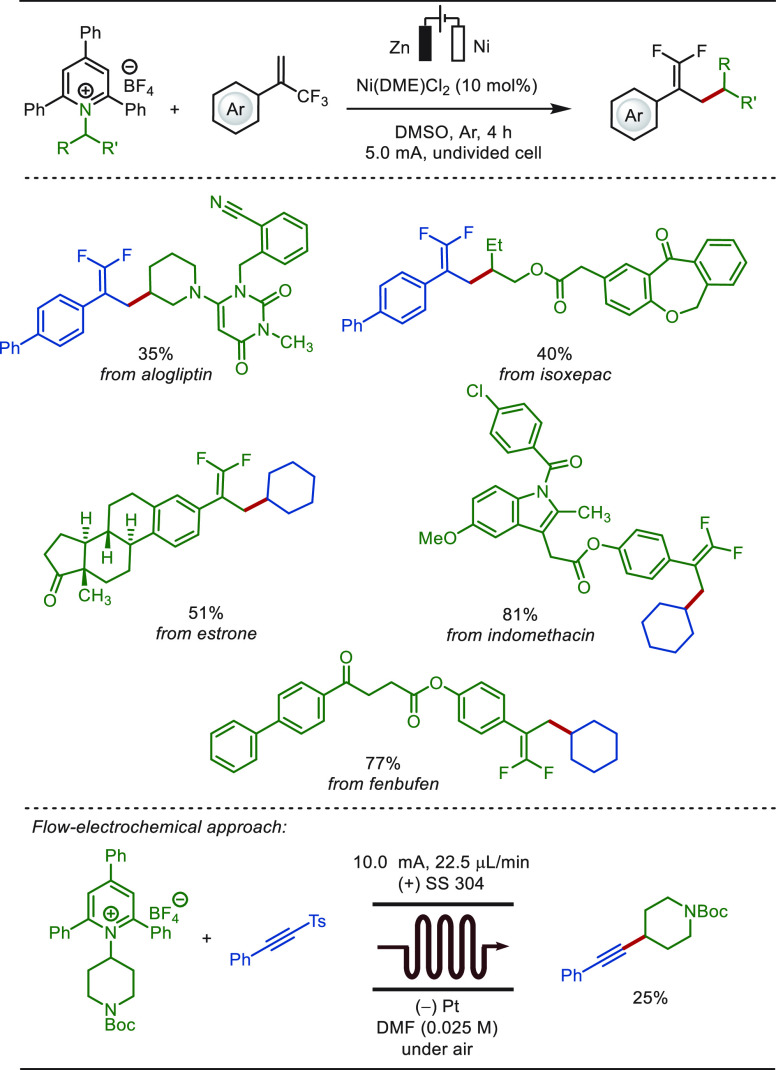

In 2021, Pan disclosed a straightforward electroreductive defluorinative functionalization of trifluoromethylated styrenes (Scheme 58).327 Notably, straightforward synthetic routes to C–C bonds harvesting sp3-hybridized carbon-centered radicals have always been considered as versatile approaches in organic synthesis. The authors used easily accessible Katritzky salt as a useful source for the generation of C(sp3)-centered radicals. This reductive deaminative approach required a sacrificial zinc anode and obviated the need for external electrolytes. Single electron reduction of Katrizky salts generated alkyl radicals, which were intercepted by the olefin forming benzylic radical. This benzylic radical under electroreductive conditions underwent SET reduction, which facilitated the defluorination of the CF3 unit, generating 1,1-difluoro substituted olefins. Interestingly the method was also operative under flow-electrochemical conditions. The synthetic utility of the method was reflected by the late-stage modification of alogliptin, isopexac, estrone, indomethacin, and fenbufen analogues.

Scheme 58. Electroreductive Late-Stage Defluorinative Alkylation of Trifluoromethylated Styrenes.

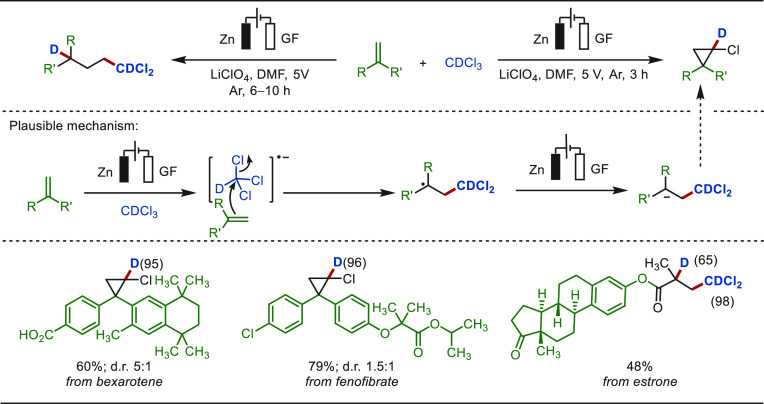

Recently, Cheng has developed an electroreductive cyclopropanation of olefins, where deuterated chloroform was used as the C1-synthon (Scheme 59).328 This electrochemical method employed a sacrificial Zn-anode for the SET reduction of CDCl3 forming a CDCl2 radical. The transient CDCl2 radical then reacted with the olefin and forged an alkyl radical, which upon eletroreduction constructed the deuterated cyclopropane derivative plausibly through the formation of a carbanion intermediate and subsequent substitution of a chloride group from the CDCl2 unit. Alternatively, the carbanion intermediate was also trapped using suitable proton/deuterium sources and CDCl3 for one-carbon elongation of terminal olefins. The current method was susceptible to afford various deuterated cyclopropane analogues with high labeling of deuterium. This cyclopropanation strategy enabled the late-stage functionalization of estrone, bexarotene, and fenofibrate analogues.

Scheme 59. Electroreductive Late-Stage Functionalization of Olefins with Deuterochloroform.

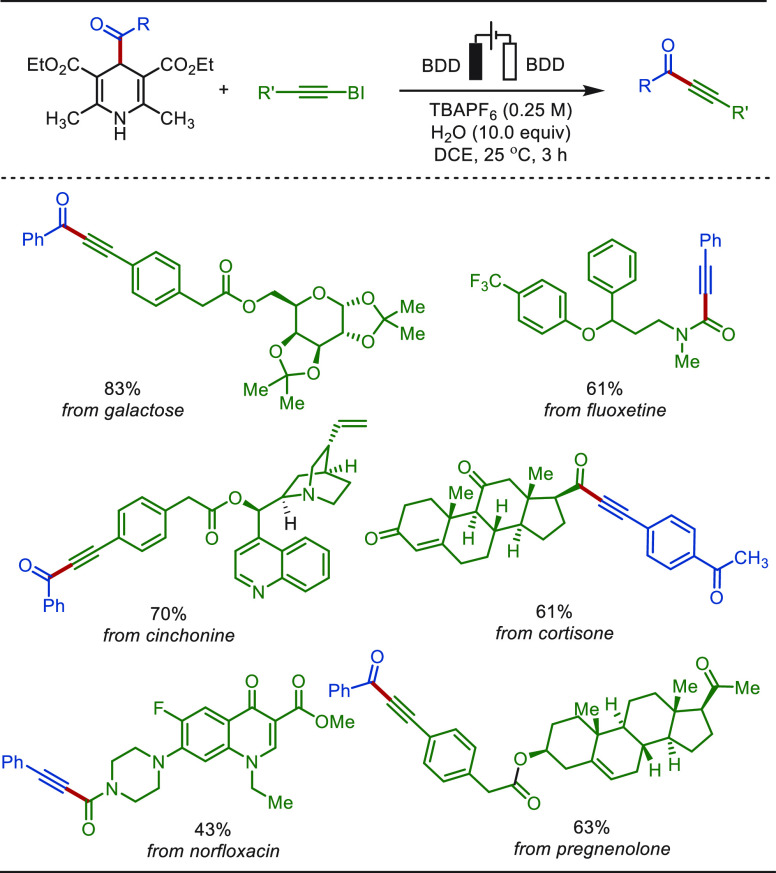

Alkynes are present in a variety of natural products and biologically relevant molecules.329 Thus, late-stage alkynylation reactions and the diversification of alkynes have also remained an attractive target in the synthetic regime. Wang delineated the conversion of 4-acyl-1,4-dihydropyridines (DHPs) into ynones through an anodic oxidation-based approach (Scheme 60).330 This reaction proceeded through the electro-oxidation of DHPs, which then produced acyl radicals. The acyl radical intermediate was then intercepted with a hypervalent iodine derived alkynyl group transfer reagent and bestowed the ynones in good to excellent yields. Notably, boron-doped diamond (BDD) was used as the electrode for this electrochemical process. Various pharmaceuticals and biologically relevant molecules were diversified by following this approach.

Scheme 60. Electrochemical Synthesis of Ynones.

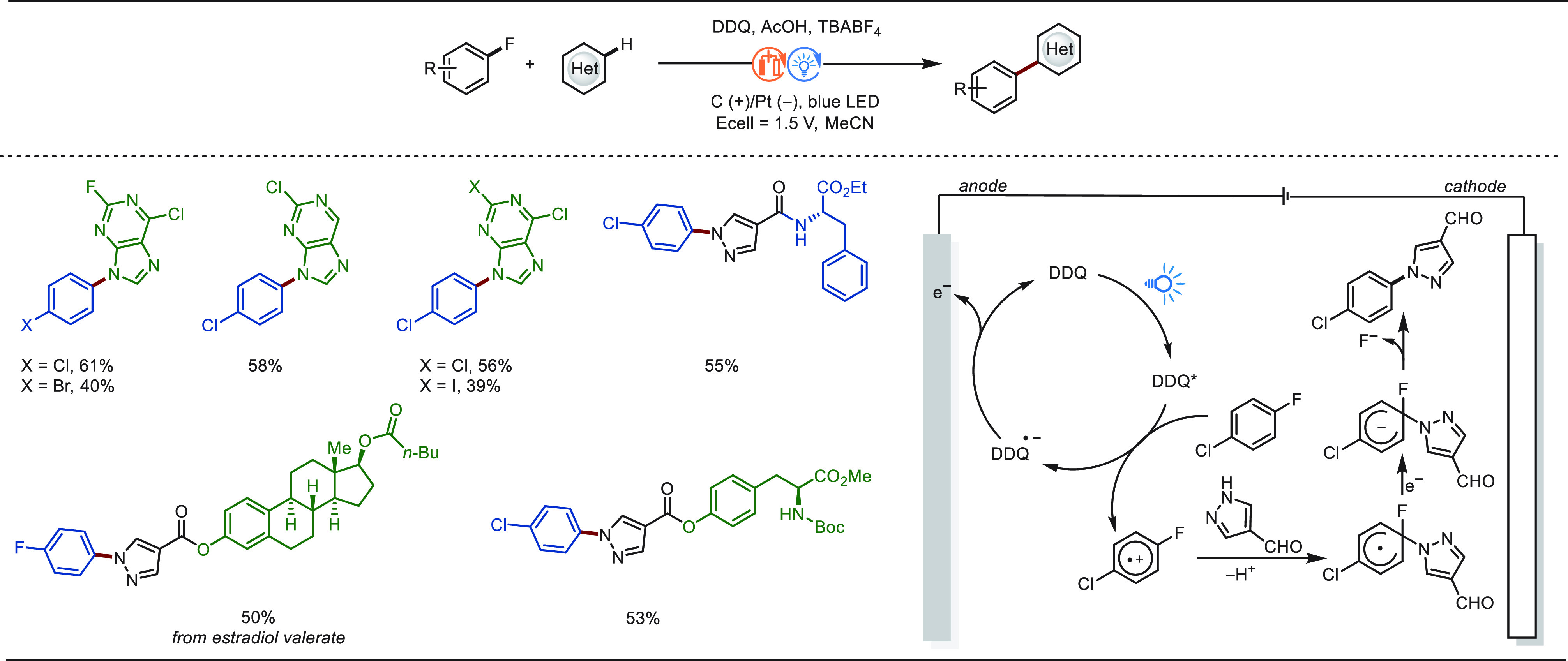

3.2. eLSF of Organic Halides

For years, organic halides have served as convenient synthetic handles for a diverse range of functionalizations using transition-metal catalysis.331−333 Manipulations over these moieties result in controlled and selective functionalization processes. Notably, electrochemical conditions have also appeared as a unique transformative tool to harvest these functionalities for late-stage functionalization reactions, and several such strategies have been reported in recent years.

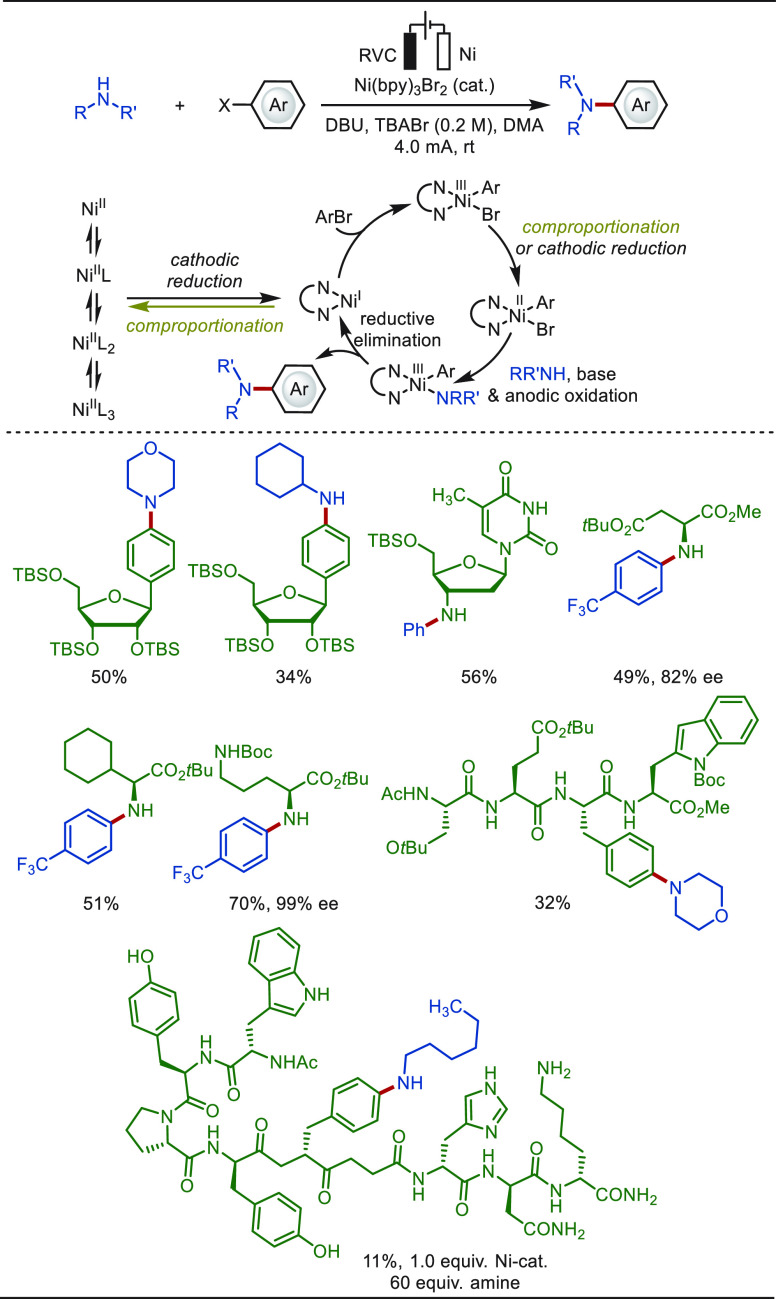

Amines and their analogues are of considerable synthetic relevance in terms of their medicinal properties.334 Notably, a large variety of pharmaceuticals or biologically relevant molecules are analogues of amines. Thus, the sustainable construction of C–N bonds have gained tremendous attention in synthetic chemists’ repertoire.256,335−338 Despite the presence of numerous synthetic strategies to gain access to these fundamental units, general and economic approaches for late-stage amination reactions have unfortunately remained elusive. In this context, Baran reported a versatile nickel-catalyzed amination of aryl halides under electrochemical conditions (Scheme 61).339 This electrocatalytic protocol harvested both cathodic reduction and anodic oxidation during the catalytic cycle to enable the transformation. The proposed catalytic cycle is initiated by the cathodic reduction of nickel(II)-precatalysts to form the nickel(I) active catalyst. The oxidative insertion of the aryl bromides onto the nickel(I) catalyst followed by comproportionation or cathodic reduction of nickel(III)-species generated nickel(II)-species. The nickel(II) intermediate after ligand exchange with the amine and reductive elimination yielded the desired aminated product. The amination reaction was successfully realized with diverse amino acids, peptides, and sugar derivatives.

Scheme 61. Nickel-Catalyzed Electrochemical Amination of Aryl Halides.

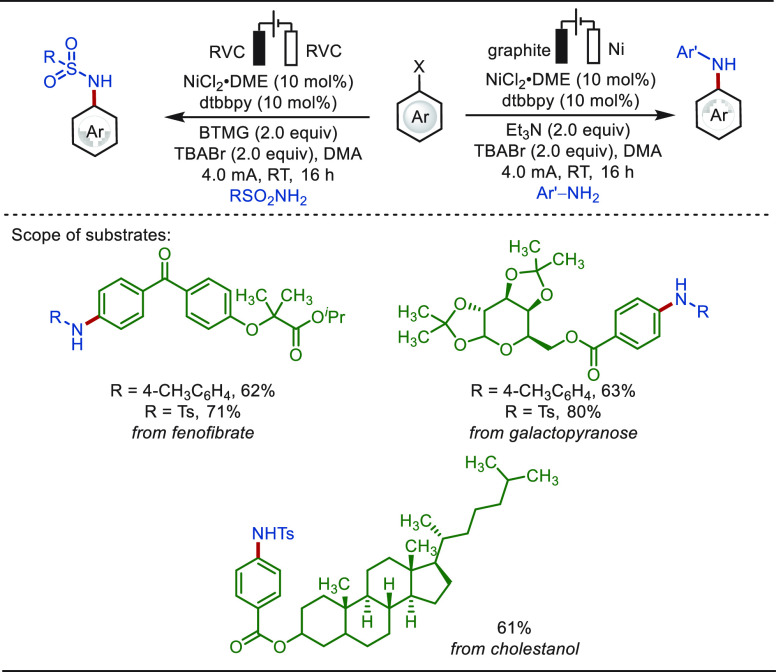

In 2021, Rueping reported an electrochemical amination of aryl bromides with weak N-centered nucleophiles (Scheme 62).340 This nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling strategy was also amenable to accommodate more challenging aryl tosylates as electrophiles, harnessing anilines, sulfonamides, sulfoximines, carbamates, and imines as nucleophiles. Interestingly, the protocol was proven to be applicable for the late-stage modification of fenofibrate, galactopyranose, and cholestanol derivatives.

Scheme 62. Nickel-Catalyzed Electrochemical Amination with Weak N-Centered Nucleophiles.

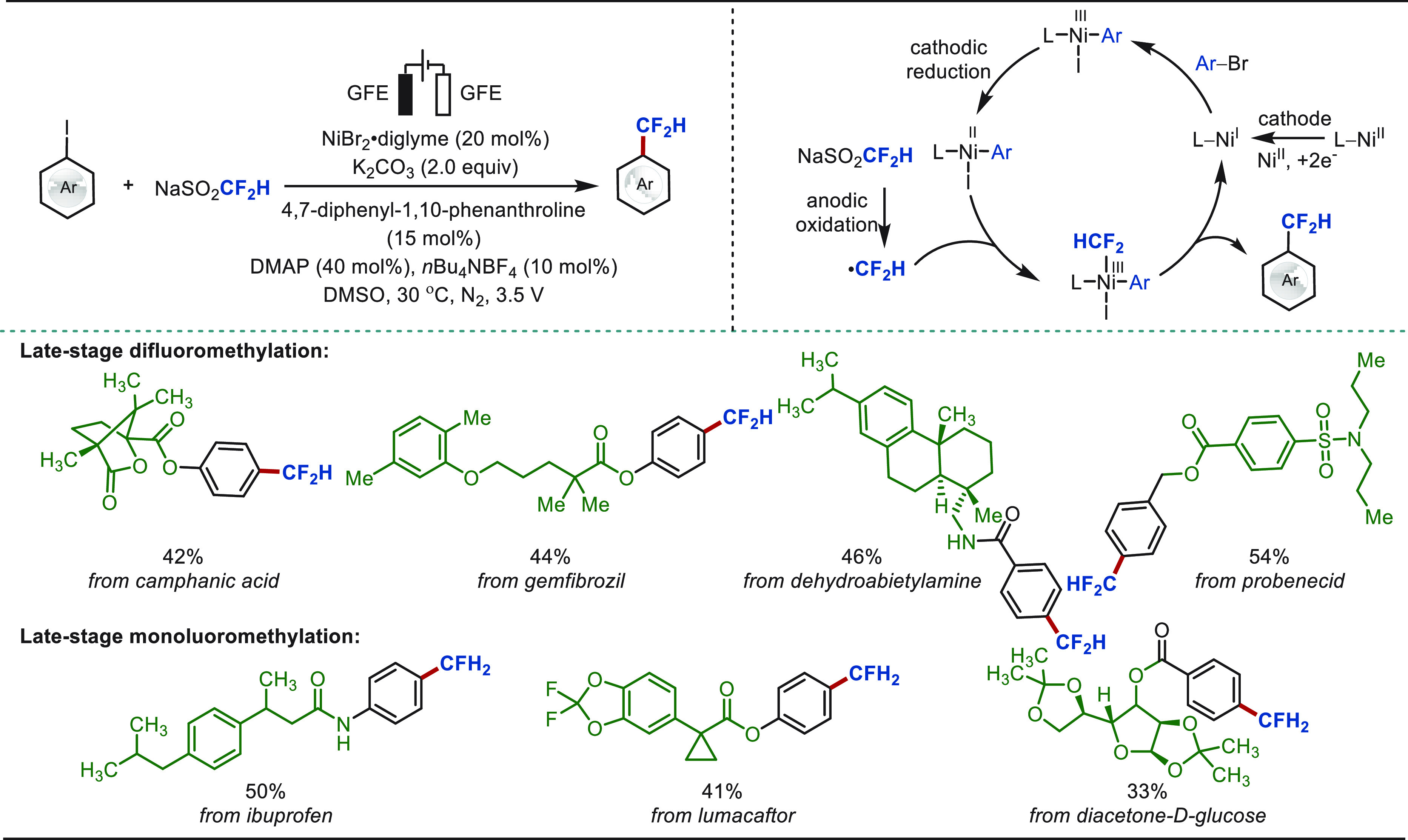

Later, Wang and Zhang developed a general nickel-catalyzed fluoroalkylation strategy with aryl iodides (Scheme 63).341 This strategy was operative via paired electrolysis, where the sulfinate salt was oxidized at the anode, forming a fluoroalkyl radical, while the cathodic reduction allowed the low-valent nickel catalysis. This method displayed good functional group compatibility and high substrate diversity. The synthetically meaningful strategy for the incorporation of difluoromethyl and monofluoromethyl groups to arenes enabled the functionalization of a broad range of natural product analogues and biologically relevant molecules.

Scheme 63. Ni-Catalyzed Late-Stage Fluoroalkylation of Aryl Iodides.

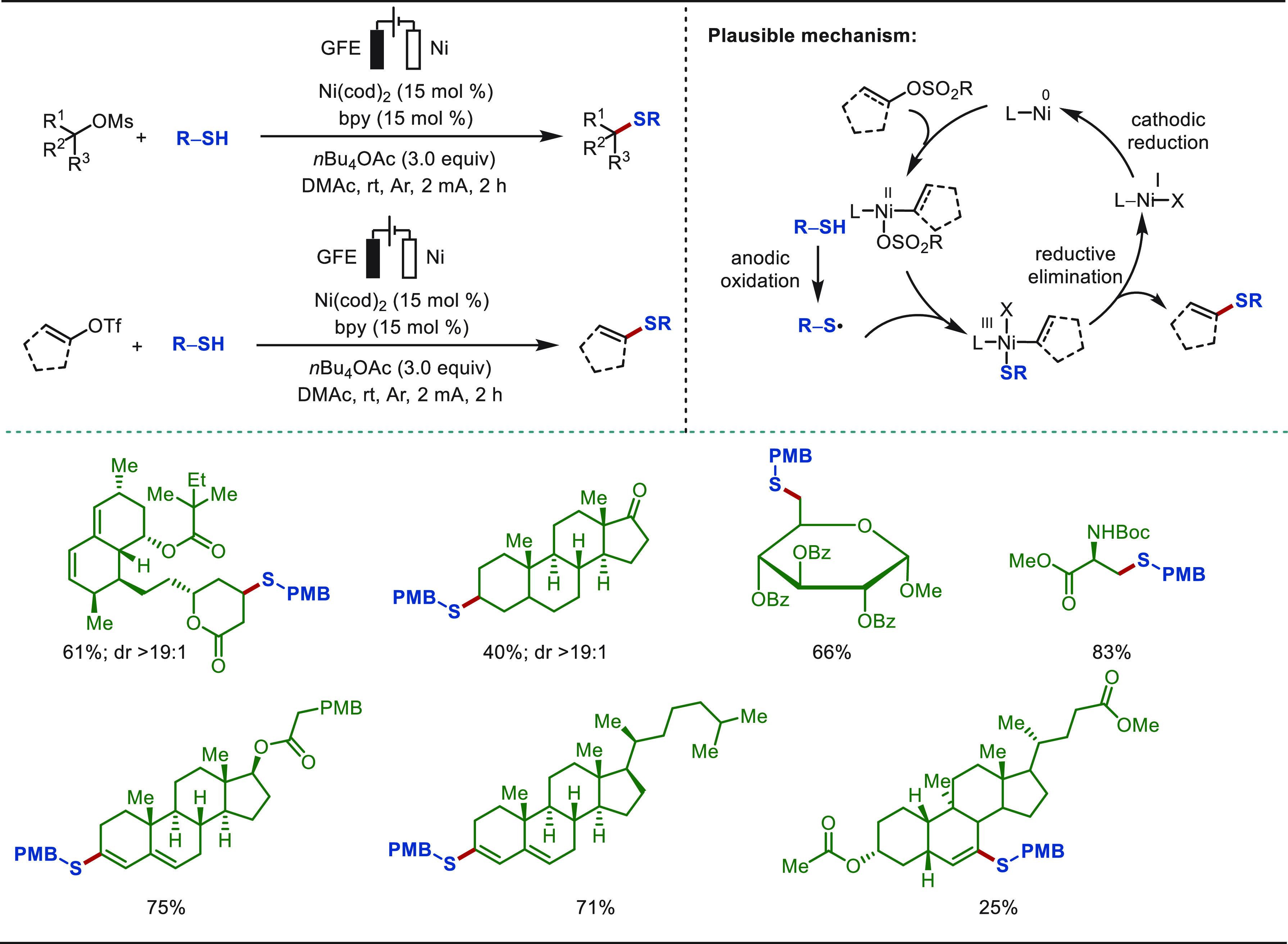

Electrochemical nickel-catalyzed functionalization strategies were not limited to organic halides. Indeed, the corresponding pseudohalides also served well as useful substrates for such transformations.342−344 In 2021, Wang and co-workers reported one such example, in which electrochemical nickel-catalysis was employed for deoxygenative thiolation of ketones (Scheme 64).345 In both of the cases the deoxygenation was facilitated through an initial activation of alcohols and ketones converting them to alkyl mesylate and vinyl triflate analogues, respectively. These reactive pseudohalide functionalities efficiently participated in the nickel-catalyzed thiolation reactions, generating the corresponding thioethers in high yields. Both approaches showed excellent functional group compatibility and enabled the late-stage diversification of a glucide derivative and various steroid analogues.

Scheme 64. Electrochemical Nickel-Catalyzed Deoxygenative Thiolation Reactions.

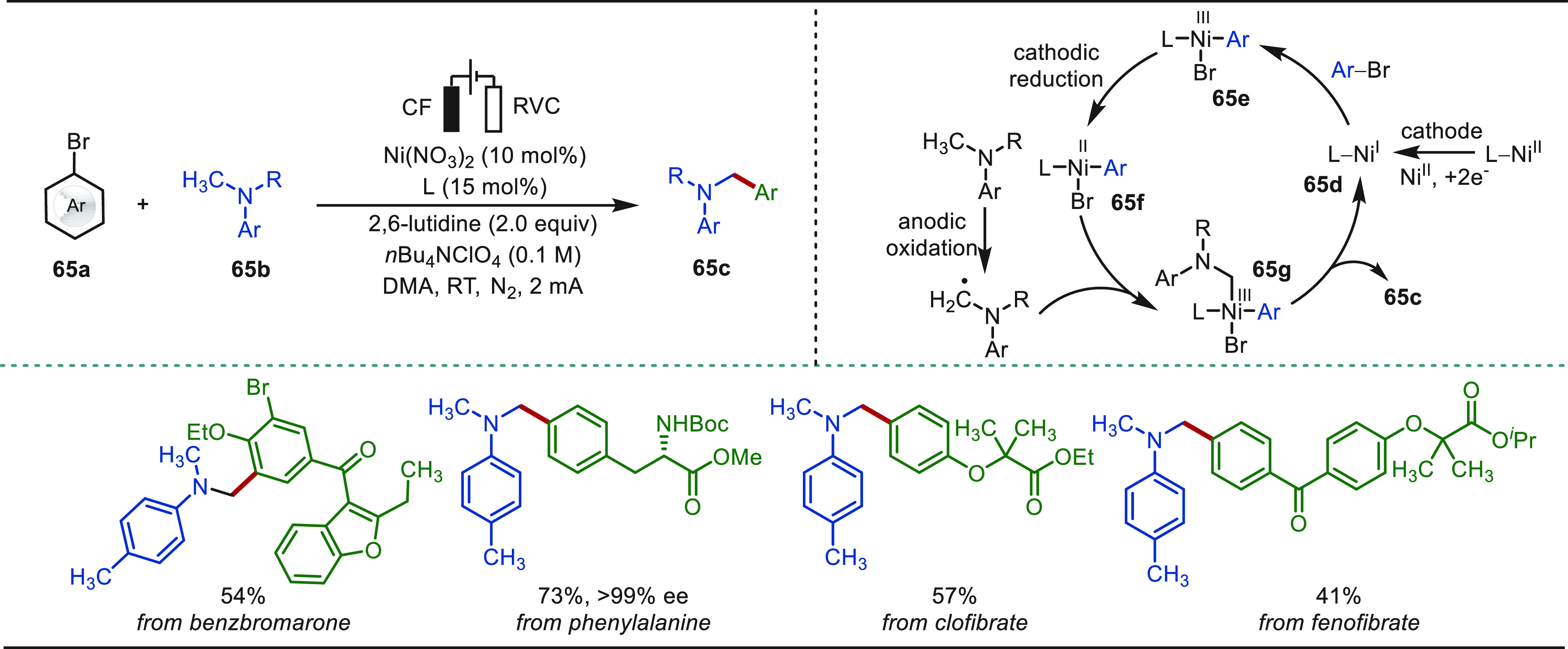

In 2021, Ye and Li reported an electrochemical nickel-catalyzed aminomethylation reaction of aryl bromides (Scheme 65).346 The reaction was proposed to proceed through a cathodic reduction of the nickel(II)-precatalyst, which upon oxidative addition to the aryl bromide gives intermediate 65e. Intermediate 65e after another cathodic reduction was intercepted by the aminomethyl radical, generated through anodic oxidation of the corresponding tertiary amine, producing intermediate 65g. Reductive elimination of 65g gave the desired aminomethylated product. This strategy was particularly powerful for the late-stage derivatization of benzobromarone, phenylalanine, clofibrate, and fenofibrate analogues.

Scheme 65. Nickel-Catalyzed Late-Stage Aminomethylation of Aryl Bromides.

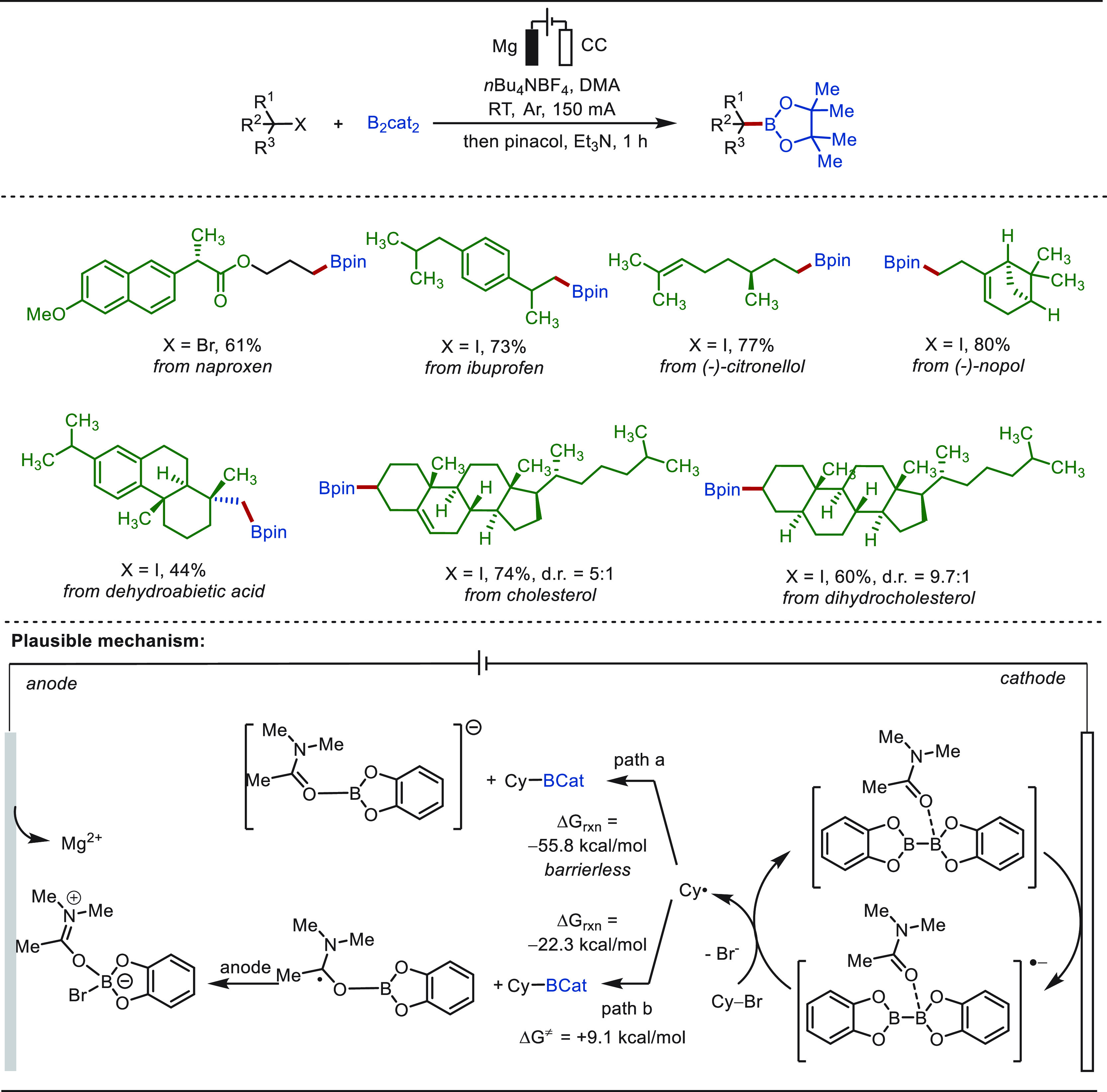

In 2021, a practical borylation was developed by Qi and Lu under electroreductive conditions (Scheme 66).347 The reduction of organic halides was induced with the aid of a sacrificial magnesium-anode, generating an alkyl radical, which was then intercepted with the diborane to construct the borylated product. The protocol operated under a high current (∼150 mA) with alkyl chlorides, bromides, and iodides. The efficiency of the approach was demonstrated through efficient late-stage borylation of natural products and drug analogues. Notably, the borylating agent served both as a boron source and a mediator controlling the reactivity of the process. The DMA stabilized B2cat2 mediated the single-electron reduction of the alkyl halide generating the alkyl radical, which then realized a barrierless radical–radical cross-coupling with B2cat2. Detailed DFT studies rendered the possibility of path b unlikely to be operative, with an activation energy barrier of 9.1 kcal/mol.

Scheme 66. Electrochemical Late-Stage Borylation of Alkyl Halides.

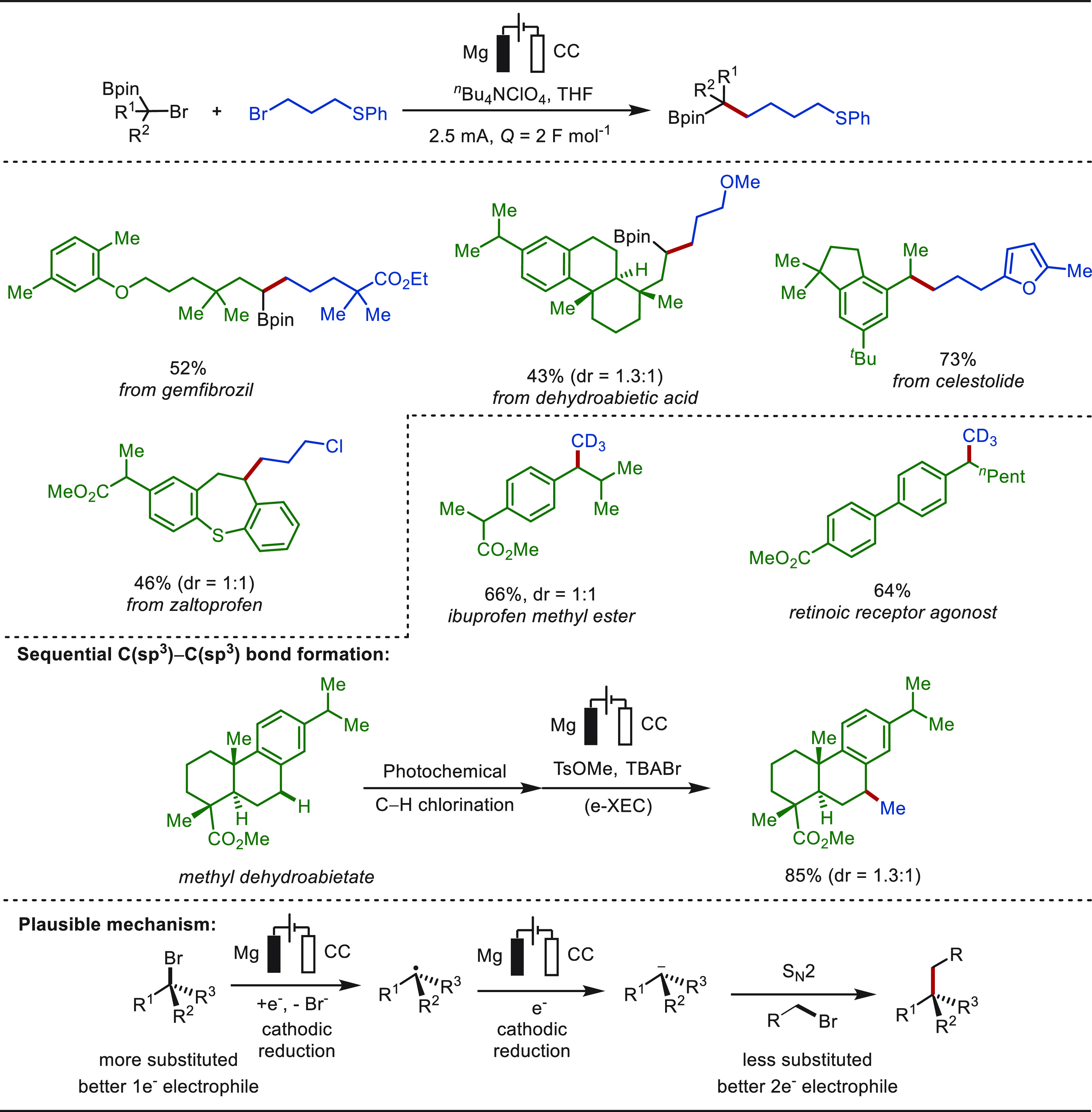

The presence of C(sp3)-rich organic molecules may improve efficacy for the drug-candidates in clinical trials.348 Thus, constant effort has been devoted to devising methods for selective formation of C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds. In 2022, Lin and co-workers developed an electroreductive strategy for the construction of C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds harvesting easily accessible alkyl halides as the alkyl source (Scheme 67).349 A selective cathodic reduction of the more substituted alkyl halide to the corresponding carbanion governed a preferential substitution of comparatively less substituted alkyl halide, forging the C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond with high precision. Altering the transition-metal-catalyzed approach with the direct electrolysis of alkyl halides avoided the typical β-hydride elimination pathway, offering a modular selective C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond formation. A sacrificial Mg-anode effectuated this transformation and the mild reaction conditions enabled the late-stage modification of complex organic molecules and drug derivatives. Further, a sequential photochemical chlorination of benzylic C–H bond followed by electroreductive methylation of methyl dehydroabietate exhibited the broad synthetic utility of this electrochemically driven cross-electrophile coupling (e-XEC). Interestingly, this sequential electrochemical alkylation process was also successful for the late-stage deuteromethylation of ibuprofen and retionic acid receptor agonist.

Scheme 67. Electrochemically Driven Late-Stage C(sp3)–C(sp3) Bond Formation.

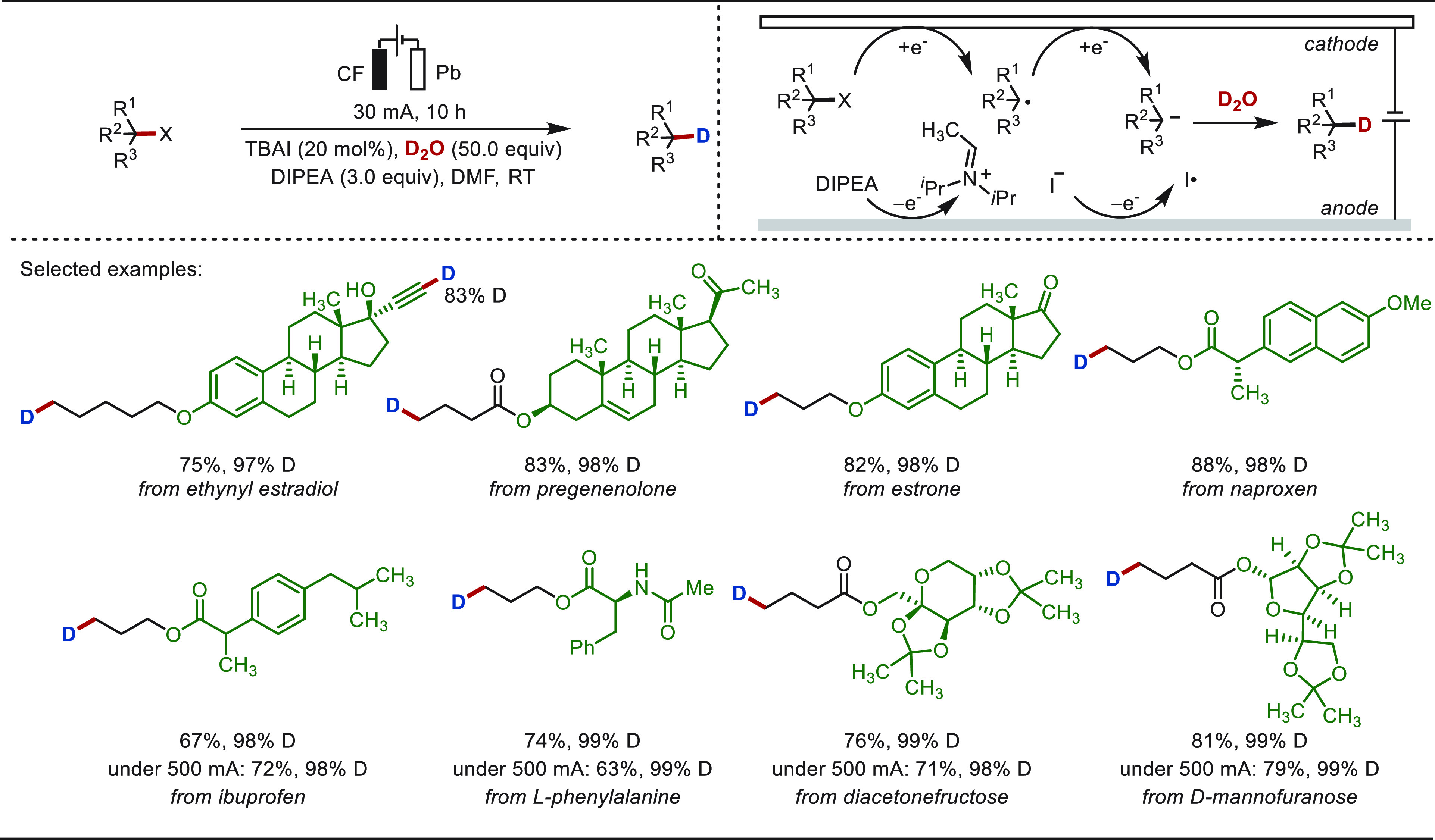

Reductive deuteration of organic halides331,350−352 constitutes a promising method to prepare deuterated molecules, which are widely used in pharmaceutical research.353−355 In 2022, Qiu described an interesting example of late-stage deuteration of organic halides, where high deuterium incorporation (up to 99%) in the product was achieved using simple D2O as the deuterium source (Scheme 68).356 The plausible reaction mechanism involved a 2-fold cathodic reduction of the organic halide forming a carbanion intermediate, which is quenched with the D2O present in the medium. This protocol was adopted for the deuterium labeling of various pharmaceuticals and their intermediates along with other complex substrates. The strategy also functioned well under 500 mA current with high selectivity, which intimated the applicability in industrial application. Under related conditions, the electrochemical reductive deuteration of aryl halides and benzylic chlorides was achieved by Lei357 and Lin,358 respectively.

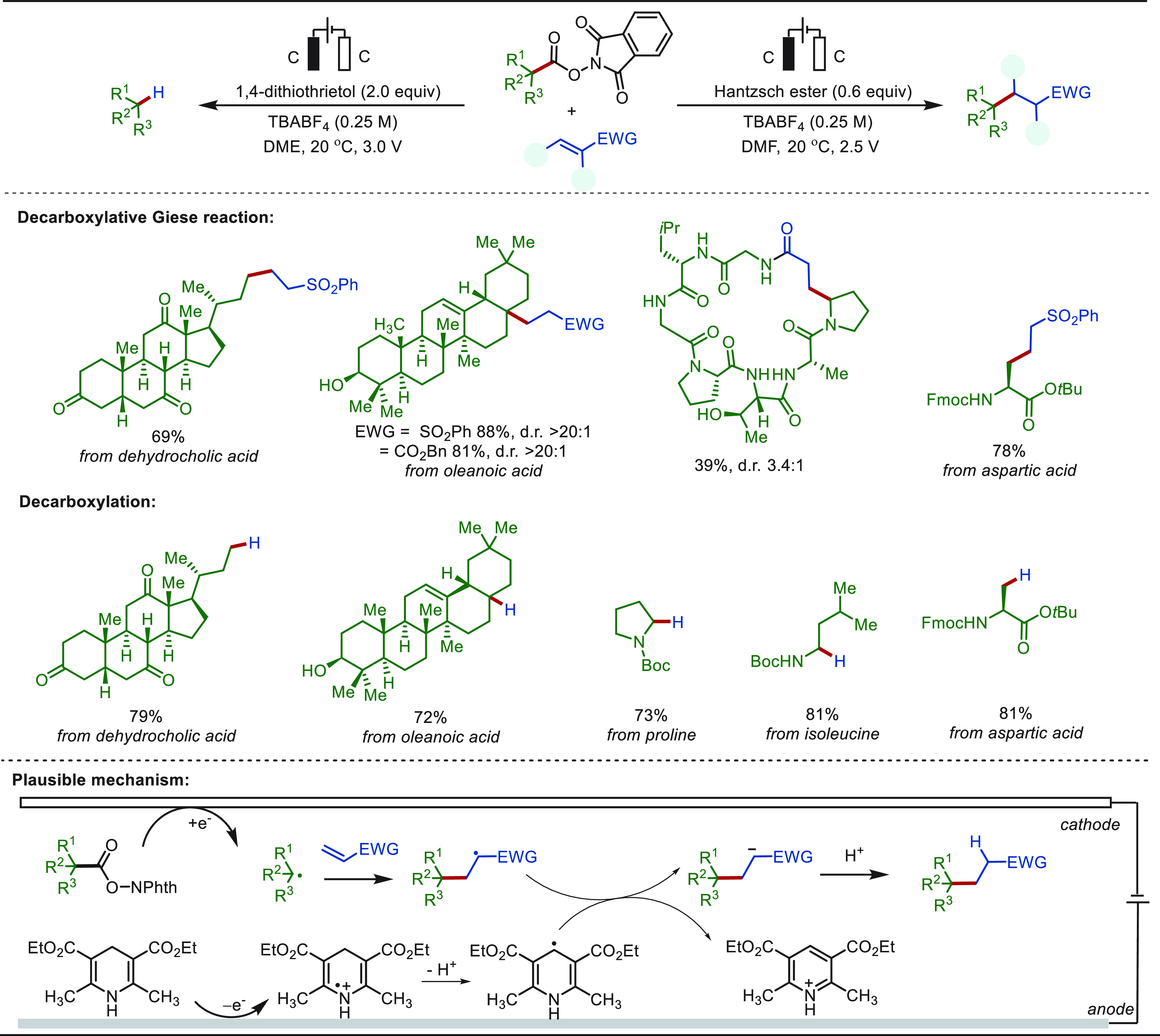

Scheme 68. Electrochemical Late-Stage Deuteration of Alkyl Halides.