Abstract

We present the case of a 39-year-old man with epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting. The patient scored 4 in the Visual Triage Checklist of acute respiratory symptoms; a COVID-19 swab was taken. Prompt review of the peripheral blood smear showed evidence of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Because the patient had a picture of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, plasma exchange and corticosteroids were started immediately. After 3 days, he developed severe ischaemic stroke and his swabs came back positive for COVID-19 by reverse transcription PCR. Therefore, triple therapy was started (lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin and interferon beta-1b). White blood cell count reached 50×109/L (normal range, 4.5–11×109/L), mainly neutrophils. All the workup for autoimmune diseases was negative. The patient showed delayed improvement in lactate dehydrogenase, haemoglobin and platelet count until we increased the volume of plasma exchange and subsided the inflammatory response of COVID-19. After that, the patient showed an excellent recovery.

Keywords: haematology (incl blood transfusion), malignant and benign haematology, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, stroke, influenza

Background

We still do not know a great deal about the manifestations associated with the coronavirus pandemic; cases with COVID-19 usually present with a unique pattern. Active COVID-19 infection complicated with ischaemic stroke1 and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) makes our case particularly challenging since TTP is a life-threatening condition among haematological diseases.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old Saudi man with a known case of diabetes mellitus type II and hypertension came with a history of epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting for approximately 7 days before admission. These symptoms were not related to food, were continual and did not improve through the administration of medications. The patient had no history of fever, cough, shortness of breath, change in the level of consciousness or skin rash. There was no history of bleeding from any orifices. The patient had not experienced a similar illness before. He was taking metformin and losartan. He denied history of autoimmune diseases within his family. His surgical, family and social histories were unremarkable.

On physical examination, the patient was stable and not in acute distress. His vital signs, including orthostatic, were normal. Pallor and pale conjunctivae were found, but were not jaundiced. The chest was clear with equal air entry and no added sounds. An abdominal examination revealed epigastric tenderness and no hepatosplenomegaly when palpated. There was no skin rash. A neurological examination was normal. There was no evidence of active oral, nasal or rectal bleeding.

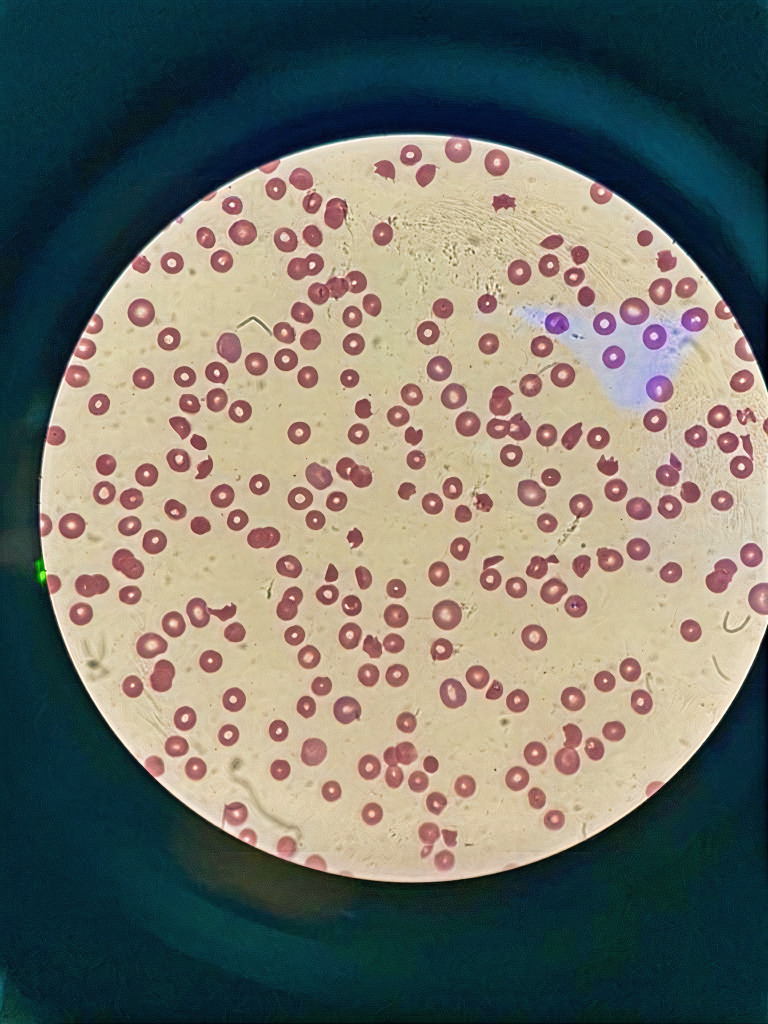

Initial complete blood count showed white blood cells (WBCs) of 14.6×103/µL (normal range, 4.5–11×103/µL), profound anaemia, haemoglobin of 67 g/L (normal range, 130–170 g/L) and a very low platelet of 6×109/L (normal range, 150–410×109/L). Schistocytes of 9% were found on a peripheral blood smear (figure 1). The workup for haemolysis was positive. Therefore, the patient was confirmed with thrombotic TTP due to thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and schistocytes in the peripheral blood film. The PLASMIC score was 6, which meant that the patient had a high risk of severe ADAMTS13 deficiency. A summary of the laboratory data and imaging is shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Peripheral blood smear on admission showed 9% schistocytes.

Table 1.

List of laboratory data and imaging

| CBC | ↓Haemoglobin, 6.7 g/dL (normal range, 13–17 g/dL) Normal MCV, 91.0 fL (normal range, 83–100 fL) ↑ RDW, 18.3% (normal range, 11%–14%) ↓ Platelet, 6×103/µL (normal range, 150–410×103/µL) ↑ WBC, 14 600×103/µL (normal range, 4.5–11×103/µL) |

| Haemolysis workup | ↑ Total bilirubin, 48.0 µmol/L (normal range, 0–20 µmol/L) ↑ Indirect bilirubin, 26.6 µmol/L (normal range, 0–8.6 µmol/L) ↑ LDH, 1600 U/L (normal range, 125–220 U/L) ↓ Haptoglobin, 0.2 g/L (normal range, 0.3–2.0 g/L) ↑ Reticulocyte count, 34.4% (normal range, 0.3%–1.5%) Negative direct Coombs test |

| Renal function and urinalysis | Normal BUN, 6.7 mmol/L (normal range, 2.5–7.5 mmol/L) Normal creatinine, 77 µmol/L (normal range, 50–110 µmol/L) Normal urinalysis |

| Serology | ↑ CRP, 7.68 mg/L (normal range, 0.0009–3.3 mg/L) ESR, 2 mm/1st hour (normal range, 0–10 mm/1st hour) Negative ANA and anti-dsDNA Negative anticardiolipin, β−2 glycoprotein I antibody and lupus anticoagulant Negative ANCA screening Negative anti-Smith Normal C3 and C4 Negative rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP Negative thyroglobulin antibody |

| ADAMTS 13 | Not available |

| Coagulation | Normal PT, INR, PTT and fibrinogen level ↑ D-dimer, 7.29 µg/mL (normal range, <0.5 µg/mL) |

| Infection workup | ↑ Ferritin, 1556 ng/mL (normal range, 18–270 ng/mL) Negative blood culture, urine culture, anti-HIV, anti-HBV and anti-HCV |

| Malignancy workup | Normal range of B-HCG, CEA, CA 19-9 and tPSA |

| Imaging |

|

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; B-HCG, beta human chorionic gonadotropin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CA 19-9, cancer antigen 19-9; CBC, complete blood count; CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CRP, C reactive protein; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; INR, international normalised ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PE, pulmonary embolism; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; RDW, red cell distribution width; tPSA, total prostate-specific antigen; WBC, white blood cell.

Differential diagnosis

An extensive investigation was done to know the cause of TTP (as mentioned in table 1). After that, an imaging CT (chest, abdomen and pelvis) was done, which showed thickening of the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries, which is concerning of vasculitis or atherosclerosis. A rheumatology consultation was done, which requested a serology workup for autoimmune disease. However, the workup was negative (as mentioned in table 1), which most probably revealed that it was idiopathic TTP. Then, the test for COVID-19 was positive, so we thought that the virus was a trigger. We knew that it was the most commonly reported complication of COVID-19 because of the absence of regular response of idiopathic TTP and ischaemic stroke happened even after four sessions of plasma exchange.

Treatment

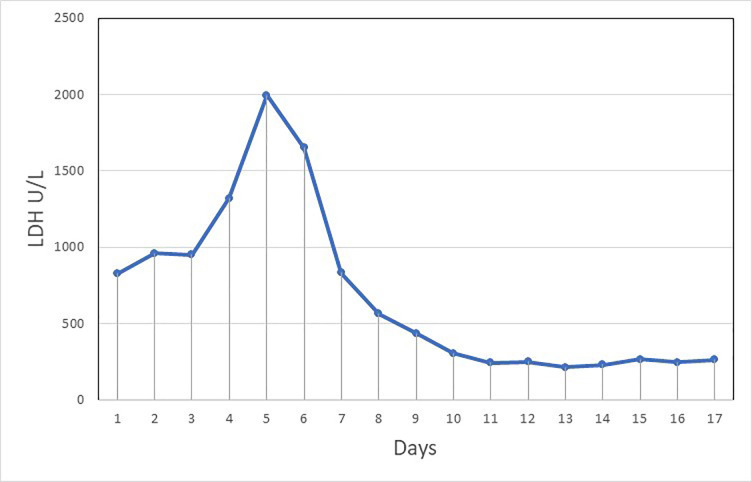

Because the patient came from a peripheral hospital that is located in the COVID-19 pandemic area and because he came with a history of nausea and vomiting, we scored 4 in the Visual Triage Checklist for acute respiratory symptoms. He was isolated and a nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 was obtained. A central venous catheter was inserted and plasma exchange started immediately at the emergency department level, combined with a first dose of methylprednisolone (1000 mg daily for 3 days). The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, and management continued there. Until day 3, no improvement was noticed in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (figure 2) and platelet count.

Figure 2.

Lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH) chart from day 1 to day 17.

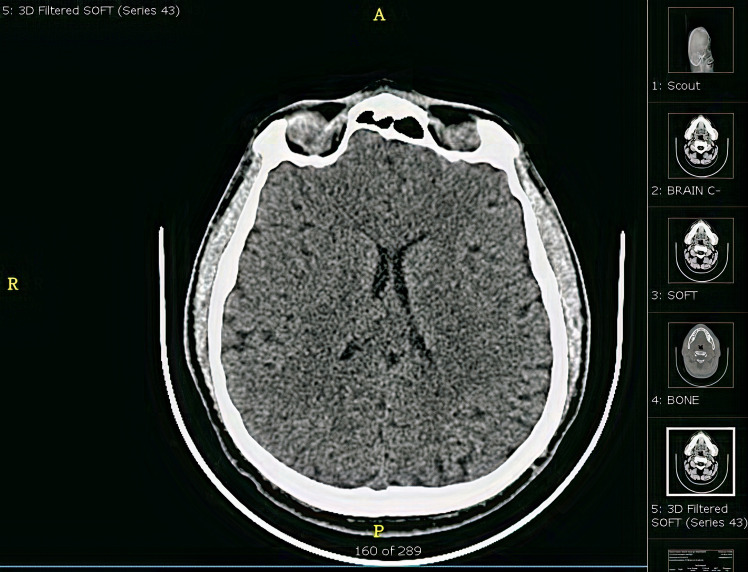

On day 4, the patient developed acute ischaemic stroke, which was revealed by a new onset of left-sided hemiplegia. Power was 0/5 in the upper and lower limbs. Acute psychosis was associated with this. He was vitally stable unless the blood pressure reached 170/100 mm Hg. CT of the brain showed normal study. There was no evidence of bleeding or ischaemia (figure 3). During the same day, his swab came back positive for COVID-19 by reverse transcription PCR. The infectious disease team became involved and they started triple therapy (lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin and interferon beta-1b). A rheumatology consultation was done regarding the finding of CT (chest, abdomen, pelvis), and they requested a serology workup for autoimmune disease. However, the workup was negative (as mentioned in table 1).

Figure 3.

CT of the brain: normal study and no evidence of bleeding or ischaemia.

On day 6, the patient was agitated and not oriented to time, place and person; on the contrary, weakness improved to 3/5 and there was still no increase in the platelet count; therefore, we increased the plasma volume from 40 mL/kg to 60 mL/kg. WBCs that were trending up reached up to 50×103/µL (normal range, 4.5–11×103/µL), mainly neutrophils. The patient did not have fever or respiratory symptoms.

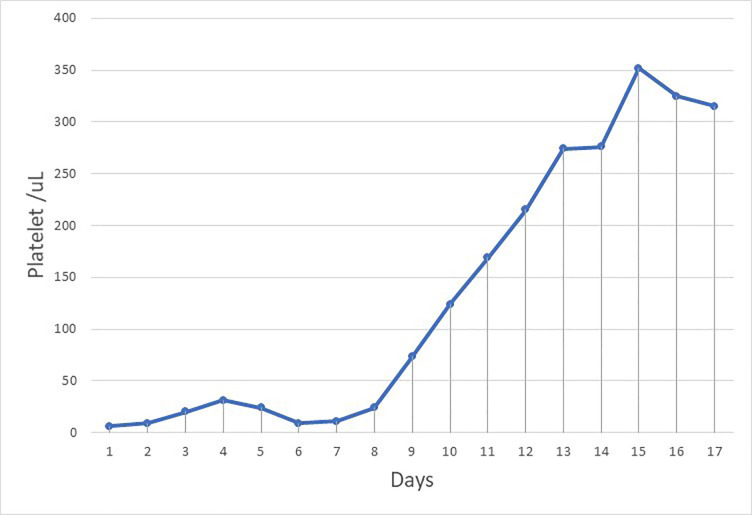

On days 8 and 9, his mental status recovered and there was improvement in platelet count (figure 4), haemoglobin, and schistocytes, with a simultaneous decrease in WBC count to normal range (figure 5), ferritin, C reactive protein (CRP) and D-dimer. This suggests that the inflammatory process of COVID-19 had a role in the recovery of TTP. The patient was then transferred to isolation ward, and second swabs of COVID-19 came back negative. There were a total of 13 sessions of plasma exchange conducted with prednisolone (60 mg for 2 weeks tapered to 10 mg every week). He received a first dose of rituximab (375 mg/m2 intravenously once weekly for 4 weeks) and was then discharged home as he had improved.

Figure 4.

Platelet chart from day 1 to day 17.

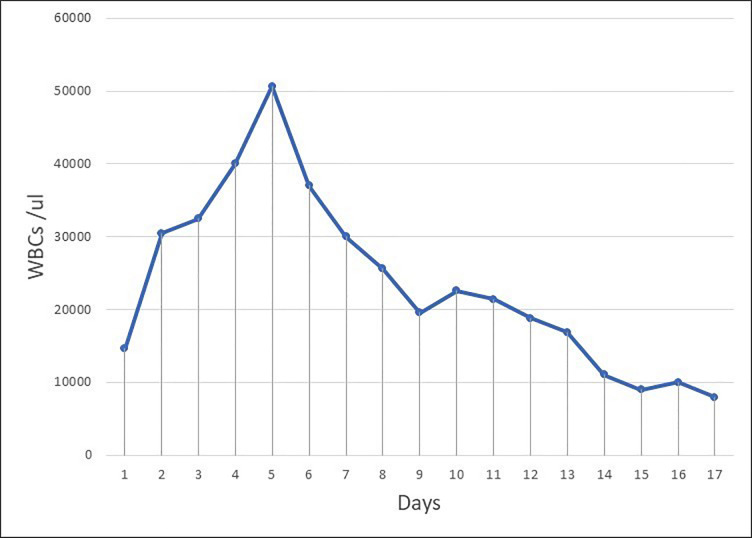

Figure 5.

White blood cell (WBC) chart from day 1 to day 17.

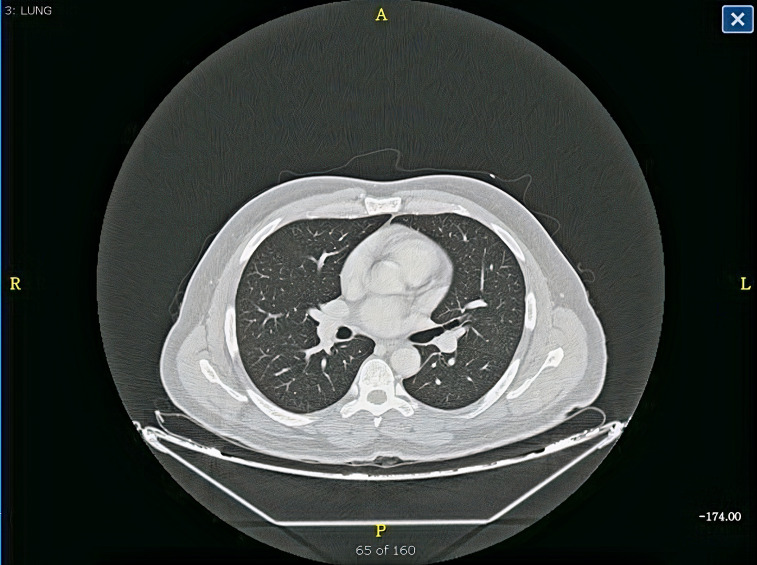

Figure 6.

CT of the chest showed normal lungs and no pulmonary embolism.

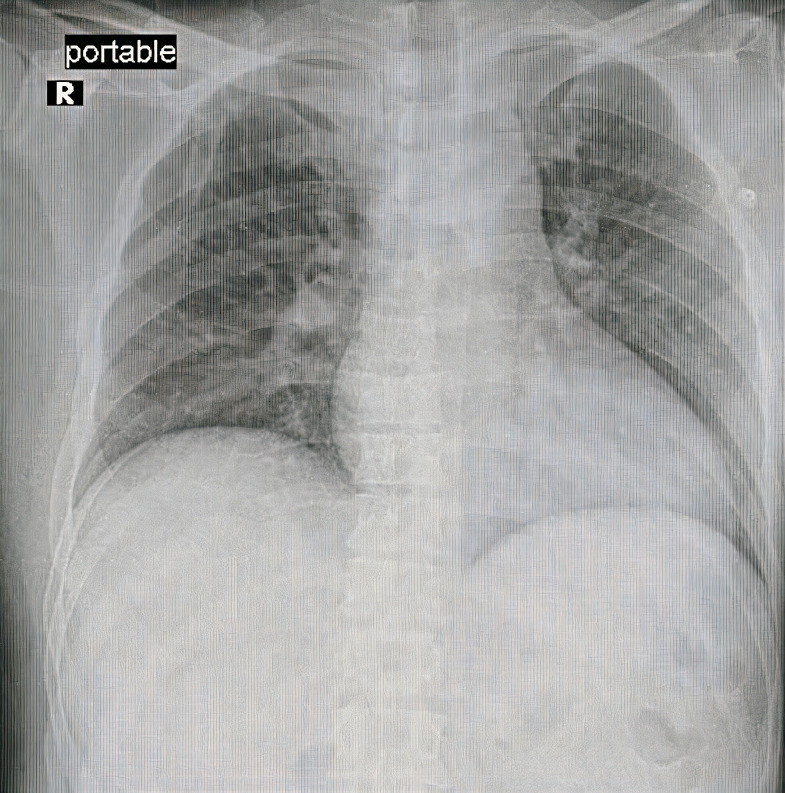

Figure 7.

Chest X-ray was normal.

Outcome and follow-up

We noticed an improvement in platelet count with a simultaneous decrease in WBC count, ferritin, CRP and D-dimer, which suggests that the inflammatory process of COVID-19 had a role in the improvement of TTP. The patient was discharged in a good general status after he received his first dose of rituximab.2

Discussion

The COVID-19 outbreak is an exceptional global public health challenge. Since the end of December 2019, when the first case of SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed in Wuhan, China, the disease has spread exponentially. The most common symptoms in patients with COVID-19 are fever, shortness of breath and dry cough. In our case, unlike other studies, TTP was observed with no history of any haematological diseases.

In this case, the patient developed ischaemic stroke as TTP increases the risk of microthrombi in the central nervous system3 and also COVID-19 increases the risk of such complications,1 which made his neurological risk more higher than others. Also, during the start of TTP treatment with standard plasmapheresis (one plasma volume), we observed a delay in improvement of his platelet count, haemoglobin level and LDH level until days 8 and 9 till we increased the plasma volume to 1.5 in combination with the management of COVID-19. After exclusion of all the secondary causes of TTP, his COVID-19 swab came positive, which was the most probable cause. The pathogenesis of TTP due to COVID-19 is not fully understood and has not been investigated, but it resolved as COVID-19 swab came back negative after 10 days of receiving COVID-19 triple therapy with plasmapheresis. Early diagnosis, quarantine and immediate treatment resulted in a good prognosis.

Learning points.

COVID-19 may present as a haematological disease that is not related to respiratory fields.

The response of thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) was slow compared with other TTPs.

It is better to delay retuximab until it becomes clear that the COVID-19 result is negative, since it could enhance COVID-19 activity.2

To understand the pathogenesis and proper management of TTP in patients with COVID-19, we need more positive cases to be evaluated in large studies.

Our goal is to report one of the haematological manifestations which could help physicians to suspect COVID-19 cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Faisal Aljuhani, Majed Aldhubayb,Ibrahim Almarshad, Mohsen Tulbah, Ahmad Aljarallah, Jehad Alkhlaf and Abdulaziz Almutiri.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both EA and OA are haematology consultant, and they treated the case mentioned in this report and provided all details required. MA took responsibility of COVID-19 treatment as he is an infectious disease consultant. EA and AA took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Fifi JT, Mocco J. COVID-19 related stroke in young individuals. Lancet Neurol 2020;19:713–5. 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30272-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cataland S, Coppo P, Scully M, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: frequently asked questions. American Society of hematology. Available: https://www.hematology.org/covid-19/covid-19-and-ttp [Accessed 22 Sep 2020].

- 3.Castro JTdeS, Rittner L, Appenzeller S, et al. Association of plasmic score with neurological symptoms in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). Blood 2019;134:4894. 10.1182/blood-2019-129144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]