Abstract

As one of the most prevalent RNA modifications in animals, adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing facilitates the environmental adaptation of organisms by diversifying the proteome in a temporal–spatial manner. In flies and bees, the editing enzyme Adar has independently gained two different autorecoding sites that form an autofeedback loop, stabilizing the overall editing efficiency. This ensures cellular homeostasis by keeping the normal function of target genes. However, in a broader range of insects, the evolutionary dynamics and significance of this Adar autoregulatory mechanism are unclear. We retrieved the genomes of 377 arthropod species covering the five major insect orders (Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera, and Lepidoptera) and aligned the Adar autorecoding sites across all genomes. We found that the two autorecoding sites underwent compensatory gains and losses during the evolution of two orders with the most sequenced species (Diptera and Hymenoptera), and that the two editing sites were mutually exclusive among them: One editable site is significantly linked to another uneditable site. This autorecoding mechanism of Adar could flexibly diversify the proteome and stabilize global editing activity. Many insects independently selected different autorecoding sites to achieve a feedback loop and regulate the global RNA editome, revealing an interesting phenomenon during evolution. Our study reveals the evolutionary force acting on accurate regulation of RNA editing activity in insects and thus deepens our understanding of the functional importance of RNA editing in environmental adaptation and evolution.

Keywords: A-to-I RNA editing, Adar, autorecoding, insect evolution, compensatory gains and losses

INTRODUCTION

The proteomic diversifying role of A-to-I RNA editing in animals

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing, catalyzed by ADAR (adenosine deaminase acting on RNA) enzymes, is one of the most prevalent types of RNA modification in animals (Palladino et al. 2000; Savva et al. 2012b). Inosine is structurally similar to guanosine (Fig. 1A), and therefore A-to-I RNA editing will cause similar consequences to A-to-G mutations. A-to-I editing is able to diversify the transcriptome beyond the genomic sequence (Eisenberg and Levanon 2018). If editing takes place in the coding sequence (CDS) of mRNAs, then it might alter the genomically encoded amino acid and lead to nonsynonymous changes. Nonsynonymous editing events are also termed “recoding” events (Alon et al. 2015). Mammalian genomes typically encode three ADAR genes (ADAR1, ADAR2, and ADAR3) (Savva et al. 2012b), among which ADAR2 is mainly responsible for targeting the CDS editing sites (Tan et al. 2017). Insects have experienced a loss of ADAR genes during evolution (Jin et al. 2009; Duan et al. 2022) and the only remaining Adar gene in insects is homologous to mammalian ADAR2 (Palladino et al. 2000; Keegan et al. 2011). This leads to the overrepresentation of CDS editing and recoding sites in insects compared to the editing distribution in mammals (Ramaswami and Li 2014; Picardi et al. 2017; Duan et al. 2021). The A-to-I recoded genes are highly enriched in neuronal genes due to the high expression of ADAR enzyme coupled with the tissue-specific expression of ADAR-targeted genes in nervous systems (Liscovitch-Brauer et al. 2017; Duan et al. 2018; Sapiro et al. 2019). These prevalent recoding events largely diversify the neuronal proteome.

FIGURE 1.

A-to-I RNA editing and the autorecoding sites in the Adar gene. (A) Chemical structure of adenosine, inosine, and guanosine and the process of A-to-I RNA editing mediated by the ADAR enzyme. In insects, there is a single copy of the Adar gene. (B) Adar autoregulatory pathway in Drosophila melanogaster. The autorecoding site in flies changes a Ser to a Gly, termed S > G site. (C) Convergent evolution of Adar autorecoding sites in flies and bees (Duan et al. 2021, 2022). Editing levels of each site are shown for each species. D. mel, Drosophila melanogaster; D. sim, Drosophila simulans; D. sec, Drosophila sechellia; D. ere, Drosophila erecta; B. ter, Bombus terrestris; A. mel, Apis mellifera. Editable Ser codons (at the first position) include AGT/C. Uneditable Ser codons (at the first position) include TCN (N = A/C/G/T). Editable Ile codon (at the third position) includes ATA. Uneditable Ile codons (at the third position) include ATC/T. (D) Domains and structures of Adar protein in D. melanogaster and A. mellifera. The positions of the two autorecoding sites, namely site1 and site2, are labeled in the figure.

Adaptation of nonsynonymous A-to-I RNA editing

Despite the consequential similarity between A-to-I RNA editing and A-to-G DNA mutations, a key difference is that RNA editing could regulate the proteomic diversity in a controllable manner, avoiding the pleiotropic effect caused by DNA mutations (Duan et al. 2017). RNA editing could act as the evolutionary driving force that helps organisms adapt to changeable environments (Gommans et al. 2009). Several cases have shown that this temporal–spatial flexibility of RNA editing facilitates the environmental adaptation of organisms. For example, the editing levels of a recoding site in the octopus potassium channel correlate with water temperature and regulate the opening kinetics of the channel (Garrett and Rosenthal 2012; Liscovitch-Brauer et al. 2017). Moreover, at the transcriptome-wide level, the evolutionarily adaptive signals are also observed in the brain editomes of Drosophila and other species (Yu et al. 2016; Duan et al. 2017; Shoshan et al. 2021).

Besides the “proteomic diversifying hypothesis” of RNA editing, another complementary theory proposed that nonsynonymous editing is designed for reversing unfavorable DNA mutations and thus restoring the ancestral genome sequence (Jiang and Zhang 2019; Duan et al. 2023a). This “restorative hypothesis” is generally applicable to plants and a few non-insect animal species. This theory strictly requires that RNA editing mimics DNA mutation so that no tissue-specificity editing is needed (Duan et al. 2023a). Nevertheless, it is commonly believed that in the majority of the animals, the diversifying hypothesis still dominates the evolutionary significance of nonsynonymous RNA editing (Duan et al. 2017, 2023b; Shoshan et al. 2021).

Autorecoding site in the Adar gene and its regulatory role

Given the adaptive proteomic diversification role of RNA editing in animals, the accurate temporal–spatial regulation of editing efficiency becomes the prerequisite for achieving the advantage of this RNA editing mechanism because hyper- or hypoactivity of RNA editing would lead to various abnormalities (Khermesh et al. 2016; Song et al. 2021). In Drosophila, the Adar gene has an autorecoding site in its own mRNA that changes AGT (Ser) to GGT (Gly) (Fig. 1B), termed S > G site. The protein produced from the edited Gly isoform (ADARG) has lower editing activity than the original Ser isoform (ADARS) (Savva et al. 2012a), creating an autofeedback loop to confine (stabilize) the global editing activity (Fig. 1B). In different Drosophila species (Dipetra), this S > G autorecoding site in Adar is highly conserved (Fig. 1C,D). Interestingly, in honeybee and bumblebee (Hymenoptera), the Adar gene has another autorecoding site that changes ATA (Ile) to ATG (Met), termed I > M site (Fig. 1C,D). The editing level of this I > M autoediting site is also positively correlated with the global editing activity in bumblebees (Porath et al. 2019) (see Discussion for the interpretation). It is believed that the two different autoregulatory recoding sites in Adar were independently gained in these two distant clades (flies and bees) (Duan et al. 2021).

Apart from this convergent evolution phenomenon, a more striking pattern is the occurrence of the uneditable version of the preedit amino acid (Fig. 1C). For the S > G site in Drosophila (AGT, denoted as site1), the orthologous site in the bee genome is TCA (Ser), an uneditable Ser codon (at the first position). For the I > M site in bees (ATA, denoted as site2), the orthologous site in the fly genome is ATT, an uneditable codon (at the third position) (Fig. 1C). On one hand, the autoregulatory sites (site1 in flies and site2 in bees) were independently gained through convergent evolution; on the other hand, site2 in flies and site1 in bees have smartly avoided the “editability” and have kept the original amino acid (Fig. 1C). It seems that one editable site is always linked to another uneditable site.

Aims, scopes, and significance

Regarding these two autoregulatory recoding sites in the insect Adar gene, the major questions need to be clarified under a larger evolutionary scale: (i) What are the origins and evolutionary dynamics (gains and losses) of these two sites in insects? (ii) Do these two sites show significant linkage disequilibrium (LD) in different insects, which is an editable codon to be linked with another uneditable codon (Fig. 1C)? (iii) Did these two autorecoding sites undergo compensatory evolution? (iv) Do the autorecoding sites typically conform with the diversifying hypothesis of RNA editing? As an essential regulatory mechanism that facilitates organisms adapting to the environment, RNA editing needs to be accurately modulated. Autorecoding sites enable the formation of a natural feedback loop that stabilizes the overall editing activity. Therefore, answers to our questions will help us better understand the indispensability of this regulatory mechanism in light of evolution.

In this study, we retrieved the publicly available genomes of 377 arthropod species, including one non-insect arthropod and 376 insects, covering the top five insect orders with the most abundant sequenced genomes (Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera, and Lepidoptera). By aligning the Adar autorecoding sites across all genomes, we have the following findings: (i) The two autorecoding editing sites (AGT/C and ATA) together with their uneditable counterparts (TCN and ATT/C) have frequently undergone independent gains and losses during evolution; (ii) Diptera and Hymenoptera, the two orders with >100 available genomes, have selectively chosen two different autorecoding sites, respectively. The two autorecoding sites are mutually exclusive: One site (e.g., ATA at site2) is significantly linked to another uneditable codon in the other site (e.g., TCT at site1), and vice versa (P < 0.001 in both orders); (iii) the two autorecoding sites underwent compensatory evolution; (iv) the evolutionary dynamics of the autorecoding sites, coupled with the strong linkage between one editable site and another uneditable codon, suggest the diversifying role of this autoregulatory mechanism of Adar during insect evolution. Different insects tend to selectively choose one autofeedback loop (but exclude the other way, P < 0.001) to stabilize the global editing activity. Our work deepens our understanding of the origin and evolution of regulatory RNA editing that facilitates the environmental adaptation of organisms.

RESULTS

Two autorecoding sites in Adar underwent frequent gains and losses during insect evolution

To identify the Adar gene in insect genomes and characterize the evolutionary dynamics of the autorecoding sites, we retrieved the publicly available genomes (with annotation) of 377 arthropod species, including one non-insect arthropod (Ixodes scapularis: Ixodida) and 376 insects (Materials and Methods). Our collection covered the top five major insect orders with the most known species as well as the most sequenced genomes: Hemiptera (34 species), Hymenoptera (104 species), Coleoptera (38 species), Diptera (113 species), and Lepidoptera (74 species). The other 13 insects (4 + 9), together with I. scapularis, were used as outgroups of the five major insect orders (Fig. 2A). Insects only have one Adar gene (Palladino et al. 2000; Keegan et al. 2011), so it is technically feasible to accurately identify the Adar gene in the genome of each insect (Materials and Methods).

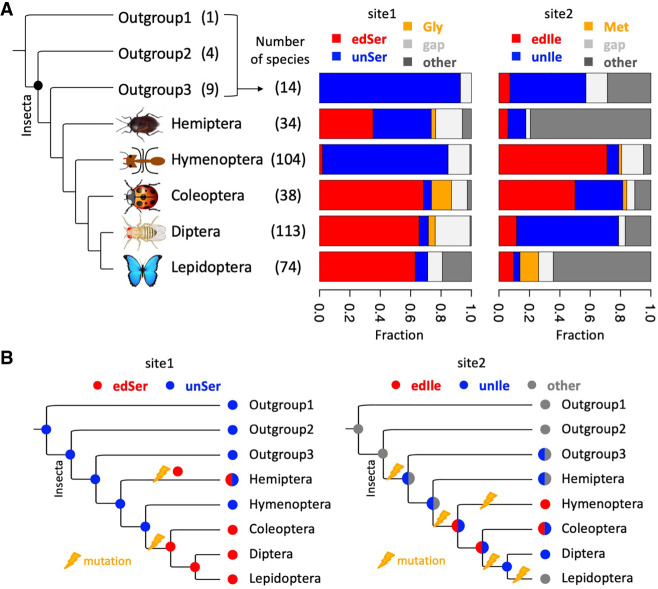

FIGURE 2.

Evolutionary dynamics of autorecoding sites in Adar. (A) Fractions of the editable (red), uneditable (blue), postedit (orange) codons of site1 and site2 in different clades. The phylogenetic tree represents a topology without branch length information. Gaps and other codons are colored in gray. (B) Gains and losses of editable (red) and uneditable (blue) codons at autorecoding sites. For site2, the codons other than editable or uneditable Ile are colored in gray. “Insecta” means the insect class.

According to the known positions of site1 and site2 in D. melanogaster (Fig. 1C), we extracted the orthologous codons in all species. We divided the site1 codons into five categories: editable Ser codons (red), uneditable Ser codons (blue), postedit version Gly codons (orange), gaps in the alignment (light gray), and others (dark gray) (Fig. 2A). In the 14 outgroup species of the five major clades, 13 species had uneditable Ser codons and one species was gapped, suggesting that the ancestral state of site1 was likely to be an uneditable Ser codon(s) (Fig. 2B). Hemiptera, the most external branch of the five major insect orders, had almost equal amounts of editable Ser codons and uneditable Ser codons, while in Hymenoptera, the uneditable Ser codons were dominant (Fig. 2A). This indicated that the editable Ser codons were gained in Hemiptera (Fig. 2B). Moreover, in the three orders of the most inner branches (Coleoptera, Diptera, and Lepidoptera), editable Ser codons were prevalent (Fig. 2A). Thus, it is highly likely that the editable Ser codons were gained in the common ancestor of Coleoptera, Diptera, and Lepidoptera (Fig. 2B).

The evolutionary history of site2 was more complicated. In the two most inner clades, Diptera was dominated by uneditable Ile codons but Lepidoptera had abundant other codons which were neither Ile codons nor the postedit version Met (Fig. 2A). Coleoptera had comparable editable Ile codons and uneditable Ile codons, while in Hymenoptera, the editable Ile codons were dominant (Fig. 2A). In Hemiptera and the outgroups, other codons were prevalent and the uneditable Ile codons only appeared in outgroup3 (Fig. 2A,B). According to these observations, the most possible evolutionary trajectory of site2 (in five major clades) is (Fig. 2B): (i) The ancestral state was a mixture of uneditable Ile codons and other codons; (ii) this status was maintained in Hemiptera; (iii) the common ancestor of the four inner clades has acquired an editable Ile codon; (iv) then the uneditable Ile codon was further lost in Hymenoptera so that only the editable Ile was observable; (v) the common ancestor of the three inner clades has maintained a mixture of editable and uneditable Ile codons, and this trend was extended to Coleoptera; (vi) Lepidoptera experienced extensive changes and acquired many other non-Ile codons; and (vii) editable Ile codons were lost in Diptera and only the uneditable Ile codons were maintained (Fig. 2B).

An editable codon is strongly linked to another uneditable codon: compensatory evolution of autorecoding sites in insects

Despite the complex evolutionary history of the two autorecoding sites in Adar genes, we did observe two orders with interesting patterns. Hymenoptera (104 species) generally had an uneditable Ser codon at site1 and an editable Ile codon at site2, while Diptera (113 species) had an editable Ser codon at site1 and an uneditable Ile codon at site2 (Fig. 2). We intuitively asked whether an editable codon is significantly linked to another uneditable codon (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

LD between the two autorecoding sites in the Adar gene. (A) Diptera. (B) Hymenoptera. (C) Hemiptera, Coleoptera, and Lepidoptera. The editable codons are colored in red. The uneditable codons are colored in blue. The D, r2, and P-values of LD are shown. Under P < 0.05, a positive D-value means that the two editable codons are mutually favored, and a negative D-value means that the two editable codons are mutually exclusive.

To do so, we mainly focused on the two orders with the most sequenced species (Diptera and Hymenoptera) and calculated the LD (Lewontin 1988) of the two editable codons (Materials and Methods). LD is originally used in population genetics and here we borrow this idea to measure how unexpected the linkage is between the two editable codons. Briefly, let E1 = editable Ser at site1, U1 = uneditable Ser at site1, E2 = editable Ile at site2, and U2 = uneditable Ile at site2. We counted the numbers of the four haplotypes E1E2, E1U2, U1E2, U1U2. Among the five major insect orders, Hemiptera and Lepidoptera contained a large fraction of non-Ile codons at site2 and therefore no sufficient numbers of E2 and U2 were available (Fig. 2). Coleoptera did not have enough numbers of the four haplotypes. Then, only Diptera and Hymenoptera were used.

In Diptera, 77.5% of the species belonged to the E1U2 haplotype among the four combinations (Fig. 3A). LD analysis showed D < 0 and P = 1.1 × 10−4, suggesting that the editable Ser codon at site1 and the editable Ile codon at site2 were mutually exclusive (avoided). In other words, an editable Ser was significantly linked to an uneditable Ile. Similarly, in Hymenoptera, an uneditable Ser codon at site1 was significantly linked to an editable Ile codon at site2 (D < 0 and P = 6.4 × 10−4), the haplotype of which consisted of 91.1% of the total species (Fig. 3B). The observations in Diptera and Hymenoptera showed the avoidance of the double-editable haplotype and indicated that one autorecoding site in the Adar gene might be enough. This inference was understandable given that both autorecoding sites were designed to form a feedback loop that constrains the total editing activity of Adar. Once an autorecoding site was obtained during evolution, then there is no need to acquire another redundant one. For the other three orders (Hemiptera, Coleoptera, and Lepidoptera), although at least 30 species were sequenced for each order, the numbers of species belonging to the four haplotypes were insufficient to obtain a significant LD (Fig. 3C). Therefore, at this stage, the relationship between the two editing sites among these orders remains uncertain. Moreover, it should be noted that Coleoptera and Lepidoptera are the top two orders with the most estimated insect species, but the sequenced species in these two orders are much less than Diptera and Hymenoptera.

Next, in Diptera and Hymenoptera, the significant linkage between an editable and an uneditable codon at the two autorecoding sites raises a follow-up question as to whether the two sites underwent compensatory evolution in Diptera or Hymenoptera. From the evolutionary dynamics of individual editing sites (Fig. 2), we could infer that the ancestor of all insects had an uneditable Ser codon at site1 and a non-Ile codon at site2 (Fig. 4). After extensive mutation and long-term evolution, site2 became heterozygous, containing both editable and uneditable Ile codons. Then, incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) occurred and Hymenoptera acquired the editable Ile allele (Fig. 4). The uneditable Ser and editable Ile haplotype (unSer-edIle) were fixed in Hymenoptera. Meanwhile, the other allele of the double uneditable haplotype (unSer-unIle) was acquired by the ancestor of Diptera. However, this double uneditable allele was unable to regulate the Adar activity so that Diptera has independently acquired an editable Ser codon at site1 to compensate the uneditable Ile at site2 (Fig. 4). Again, the limited sample size in Hemiptera, Coleoptera, and Lepidoptera prevents us from uncovering the accurate evolutionary trajectory of the autorecoding sites. Another notable fact is that many of the sequenced species in Diptera came from the Drosophila genus, which all had an editable Ser codon at site1 and an uneditable Ile codon at site2. This sampling bias might have contributed to the strong LD observed in Diptera.

FIGURE 4.

The evolutionary trajectory of the linkage of the two autorecoding sites. Editable codons are colored in red and uneditable codons in blue. Site1 in Diptera underwent compensatory mutations to acquire an editable Ser codon, which compensated the uneditable Ile in site2. As the postedited amino acids (Gly at site1 and Met at site2) did not appear at the ancestral nodes, these two autorecoding sites did not conform with the restorative hypothesis mentioned below.

One autorecoding site in Adar might be necessary and sufficient

If the regulation of Adar activity by autorecoding is essential, then we should expect each species to have at least one autorecoding site in Adar. In fact, among the five major insect orders we studied, four orders (Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera, and Lepidoptera) had over 65% species with at least one autorecoding site (Fig. 5A). In Coleoptera, this fraction was as high as 86.8%. Notably, Hemiptera had <50% species with an autorecoding site due to a large fraction of gaps at site1 and plenty of non-Ile codons at site2 (Fig. 2A). If we solely focus on editable and uneditable codons at site1, there is still ∼50% of the species possessing an editable autorecoding site. Therefore, there was a general trend that most of the species from the five major insect clades had the demand to acquire an autorecoding site in the Adar gene, presumably in order to regulate and stabilize the overall RNA editing activity. This suggests that autorecoding of Adar is necessary.

FIGURE 5.

Species with autorecoding site in the Adar gene. (A) Fractions of species with at least one autorecoding site. The numbers of species of each clade are provided in parentheses. (B) The 3-mer motif around the focal editing site. The sequences of all species with autorecoding sites were pooled.

Moreover, as the LD analyses showed, in major insect orders the two autorecoding codons in the Adar gene were mutually exclusive: An editable codon at one site was significantly linked to an uneditable codon at another site (Fig. 3). This indicates that one autorecoding site might be sufficient. Taken together, we concluded that having one autorecoding site in Adar is necessary and sufficient. This theory is highly plausible given that this autorecoding mechanism functions as a stabilizer to limit the overall editing activity to a reasonable range.

The editable codons have high editability

Indeed, our inference of the Adar autorecoding event in each species was largely based on whether the codon was “editable” (containing an adenosine at a given position). However, an editable codon does not ensure the occurrence of RNA editing events. Strictly speaking, RNA-seq data or Sanger verification are needed to confirm the occurrence of editing events at the autorecoding sites. Nevertheless, we provide the following evidence to prove that the editable codon was an accurate representation of the editing events.

There were few insect species with RNA-seq data of heads or brains that have been studied on the Adar autorecoding site (four Drosophila species and two bees). Site1 was highly conserved in Drosophila, and site2 was highly conserved in bees. Accordingly, editing events were detected at the editable codon for all species and the editing levels ranged from 0.2 to 0.5 (Fig. 1C; Porath et al. 2019; Duan et al. 2021). These known facts suggest that if another species has an editable codon at the orthologous site, then the editing event is likely to take place.

RNA editing is more likely a probability, and this probability is determined by Adar activity (trans) as well as the sequence context (cis). For all our species with an editable codon at site1 or site2, the sequence context (3-mer motif) around the autorecoding site is the most favorable binding motif of the Adar enzyme, which is HAG (Fig. 5B): a non-G (H) nucleotide upstream of the focal editing site and a G downstream from the focal editing site (Duan et al. 2017). This again suggests that the context of the editable codons has already been optimized to allow efficient RNA editing.

DISCUSSION

Adaptation of Adar autorecoding sites: the proteomic diversifying hypothesis

In this work, we have observed independent gains and losses and compensatory evolution of the Adar autorecoding sites in major insect orders, demonstrating the functional importance of this autoregulatory mechanism in insects. However, one question remains to be answered. Based on known theories of adaptive RNA editing, if an editing site is evolutionarily adaptive, then it should conform with either the “proteomic diversifying hypothesis” (Gommans et al. 2009; Duan et al. 2017) or the “restorative hypothesis” (Jiang and Zhang 2019; Duan et al. 2023a). The adaptive nature of the Adar autorecoding sites should be clarified.

The proteomic diversifying hypothesis stresses that RNA editing provides the spatial–temporal flexibility to facilitate a species adapting to a changeable environment or to regulate the developmental/tissue-specific transcriptomes of an organism. This flexibility successfully avoids the pleiotropic effect introduced by DNA mutations (Fig. 6A). If a DNA mutation is beneficial in adult flies but deleterious in larva, then this mutation could not be maintained as it would be purged along with the elimination of larva (Fig. 6A). In contrast, RNA editing could selectively “mutate” the adult transcriptome while keeping the larva transcriptome intact. This posttranscriptional modification avoids the antagonism caused by DNA mutations (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Adaptive proteomic diversification of Adar autorecoding site. (A) The adaptiveness of RNA editing is achieved by temporal–spatial flexibility of controlling the proteomic diversity, avoiding the pleiotropic effect of DNA mutations. (B) Correlation between the global Adar activity and the autorecoding level of S > G site in different samples of D. melanogaster. (C) The stabilizing effect of the Adar autorecoding site.

Evidence suggests that the Adar S > G autorecoding site in D. melanogaster typically conforms to this scenario. Across different developmental stages and tissues, Adar expression varies widely and is the highest in adult heads but relatively low in larva (Duan et al. 2017). Accordingly, the editing level of the Adar S > G site correlates with the global Adar expression (Fig. 6B). As the edited AdarG isoform has lower editing activity than the unedited AdarS version (Fig. 1B), this autorecoding site allows the flexible switch between the two Adar isoforms, stabilizing the global Adar activity (and thus the overall editing efficiency in the transcriptome) (Fig. 6C). This is strong evidence supporting the proteomic diversifying role of the Adar autorecoding site.

In contrast, no evidence supports the restorative hypothesis of these autorecoding sites. The restorative hypothesis proposes that A-to-I RNA editing reverses (rescues) genomic G-to-A mutations. This requires the existence of G-allele, which is the postedited version in the ancestral node. In our case, however, very rare postedited codons were observed among the species (Gly for site1 and Met for site2, Fig. 2A). One could hardly find a case where an A-to-I RNA editing site takes place on an adenosine site with ancestral guanosine. Given these observations, the autorecoding sites in the Adar gene belong to the “proteomic diversification” category.

Adar autorecoding level is still positively correlated with the global editing level, although it plays an inhibitory role

While in flies the S > G autorecoding (site1) forms a negative feedback loop (Savva et al. 2012a), in bumblebees the editing level of this I > M autoediting (site2) is positively correlated with the global editing activity in bumblebees (Porath et al. 2019). This does not mean that autoediting at site2 promotes editing activity. As shown in Figure 6B,C, even in Drosophila the autorecoding level at site1 should be positively correlated with global editing activity.

We presume two extreme situations:

Case1: Adar expression = 10, no autorecoding (L_auto = 0), total editing activity = 100, global editing level L_global = 0.1.

Case2: If we double Adar expression to 20 without autorecoding (L_auto = 0), then the total editing activity will be 200 and the global editing level will be L_global = 0.2.

However, at Adar expression = 20, there is autorecoding, so that the total editing activity is suppressed to <200. Consequently, the global editing level will be L_global < 0.2 and maybe 0.16.

Comparing case1 and case2, the autorecoding level L_auto is positively correlated with global editing level L_global, but the autorecoding still plays an inhibitory role in Adar editing activity.

Conservation and convergent evolution

Regarding the convergent evolution of autorecoding sites in different clades, we need to clarify and distinguish between the two terminologies: conservation and convergent evolution (Fig. 7). In the broad sense, convergent evolution does not necessarily require the emergence of the same gene or site. For example, the wings in birds, bats, and insects came from different origins but this case is treated as the textbook example of convergent evolution. Here, let us focus on a single editing siteA in Hymenoptera and Diptera. If siteA is observed in all other insect clades as well as the outgroup, then our conclusion is that siteA is conserved between Hymenoptera and Diptera (Fig. 7). For another siteB, if it is only present in Hymenoptera and Diptera but not in other clades, then we conclude that siteB underwent convergent evolution in the two orders (Fig. 7). If geneX has two different editing sites in Hymenoptera and Diptera, respectively, just like the case of Adar autorecoding, then it is interpreted that the orthologous genes independently gained the autorecoding mechanism, justifying convergent evolution (Fig. 7). Importantly, genome-wide evidence for convergent evolution is that the number of edited orthologous genes significantly exceeded the random expectation (Duan et al. 2021, 2022), suggesting that the editing sites are not scattered in the orthologous genes by chance. Similarly, when we focus on the presence and absence of orthologous genes, the presence of geneY in all clades represents the conservation of geneY (Fig. 7). The presence of paralog geneY1 in Hymenoptera and geneY2 in Diptera indicates convergent evolution (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Elucidating conservation and convergent evolution at different layers. Sites and genes are shown as examples. SiteA and siteB are two editing sites. GeneX has two editing sites. Y1 and Y2 are the paralogous genes. “√” represents the presence and “O” represents the absence. “cons,” conservation; “converg,” convergent evolution.

ADAR autoediting in other animal clades

Given the interesting findings in autorecoding sites in insects, it is intuitive to ask if autoediting exists in other animal clades like mammals. We retrieved the lists of A-to-I editing sites of human and mouse from our previous collection (Duan et al. 2022). In humans, ADAR1 has 189 editing sites in 3′UTR, 341 intronic sites, and three nonsynonymous sites. ADAR2 has two sites in 3′UTR, 422 intronic sites, 12 nonsynonymous sites, and seven synonymous sites. ADAR3 has 45 sites in 3′UTR and 634 intronic sites. In mice, ADAR1, ADAR2, and ADAR3 have two, 22, and 64 intronic editing sites, respectively. Although these editing sites take place on mammalian ADAR genes, they are not necessarily edited by the corresponding paralog. For example, the editing sites in ADAR2 transcripts may not be exactly edited by ADAR2. Therefore, strictly speaking they are not “autoediting” sites. Moreover, the functional studies on editing sites in mammalian ADAR genes are very rare (Lin et al. 2023). In contrast, insects only have one Adar gene so that the editing sites in Adar transcripts are definitely exerted by Adar itself.

Conclusions

Our work has the following main findings: (i) Two autorecoding sites in the Adar gene underwent frequent gains and losses during insect evolution; (ii) one autorecoding site per species is enough: an editable codon at one site is significantly linked to an uneditable codon at another site; (iii) compensatory evolution is observed for the two autorecoding sites; (iv) autorecoding sites in the Adar gene confer their adaptiveness by diversifying the proteome in a temporal–spatial manner. Different clades of insects independently selected different autorecoding sites in the Adar gene to achieve the same goal, which is to form an autofeedback loop and stabilize the global RNA editing levels. This evolutionary trajectory has not been reported in any other animal clades and therefore represents a miracle in insect evolution. Our study reveals the necessity of accurate regulation of RNA editing activity in insects, and thus deepens our understanding on the functional importance of this RNA editing mechanism in environmental adaptation and evolution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data availability

The genome accession IDs of the 377 arthropod species are provided in Supplemental Table S1. Our collection includes outgroup1 (Ixodida, one species), outgroup2 (Ephemeroptera and Odonata, four species), outgroup3 (Orthoptera, Phasmatodea, Plecoptera, and Blattodea, nine species), Hemiptera (34 species), Hymenoptera (104 species), Coleoptera (38 species), Diptera (113 species), and Lepidoptera (74 species). The Adar protein sequence of D. melanogaster was downloaded from FlyBase (https://flybase.org/) version dm6.04 with protein ID FBpp0308381 (corresponding transcript ID: FBtr0339272, gene ID: FBgn0026086). The topology of the phylogenetic tree was retrieved from the TimeTree website (http://www.timetree.org/).

Sequence alignment

Insects only have one Adar gene that is homologous to mammalian ADAR2 (Palladino et al. 2000; Keegan et al. 2011). The Adar sequence in model insect D. melanogaster is well annotated. We aligned the D. melanogaster Adar protein sequence to the CDS sequence of each arthropod species with tblastn (Camacho et al. 2009). Default parameters were used. The hit with the lowest E-value was regarded as the Adar gene in each species. The Adar gene sequences from all species were combined into one file and were aligned with mafft (Katoh and Standley, 2013) with default parameters. The orthologous sites of the two autorecoding codons were extracted from the alignments according to their known positions in D. melanogaster. Note that “gap” means that in the multiple sequence alignment, there are particular regions that are unaligned in some species (while in other species there are aligned sequences). The unaligned regions are gaps. In the case of the Adar autorecoding site, gap in a species means that this species does not have this codon at all, let alone the editable or uneditable status. However, there is a possibility that the “gap” does not really represent the deletion in the orthologous site. It is likely due to the low quality of some genome assemblies. Moreover, the gap might not be a technical bias from the alignment as the Adar gene is highly conserved in insects. Each insect has one Adar gene and there are almost no confounding factors to affect the alignment. Thus, the alignment should be simple and accurate.

Classification of editable and uneditable codons

In all species, the orthologous sites of site1 and site2 were classified into five groups. For site1, editable Ser codons (at the first position) include AGT/C, uneditable Ser codons (at the first position) include TCN (N = A/C/G/T), postedit version is GGN (Gly), unaligned regions are gaps, and the remaining is denoted as others. For site2, editable Ile codon (at the third position) includes ATA, uneditable Ile codons (at the third position) include ATC/T, postedit version is ATG (Met), and the same goes for gaps and others.

Linkage disequilibrium

LD was calculated following Lewontin (1988). For both site1 and site2, we denoted the editable codon as E and the uneditable codon as U. The frequencies of E and U at site1 and site2 were E1, E2, U1, and U2. The haplotype frequencies of the four combinations were fE–E, fU–U, fE–U, and fU–E. We then defined the following parameters.

D = fE–E fU–U − fE–U fU–E. D > 0 means E1 and E2 are mutually favored and D < 0 means E1 and E2 are mutually exclusive.

r2 = D2/E1E2U1U2.

χ2 = r2 · N, where N is the total number of the four haplotypes.

The P-value of LD was calculated by P(χ2) under df = 1.

Protein structure prediction

The 3D structure of Adar was accomplished by AlphaFold. AlphaFold was performed by running the AlphaFold2 notebook on Google Collaboratory cloud computing facilities with default parameters. The Google Colab is accessible online at https://colab.research.google.com/github/phenix-project/Colabs/blob/main/alphafold2/AlphaFold2.ipynb.

Statistical tests

Statistical tests P(χ2) were performed in R studio (R version 3.6.3). The graphical works were done in the R environment.

DATA DEPOSITION

The genome accession IDs of the 377 arthropod species were provided in Supplemental Table S1. Our collection included outgroup1 (Ixodida, one species), outgroup2 (Ephemeroptera and Odonata, four species), outgroup3 (Orthoptera, Phasmatodea, Plecoptera, and Blattodea, nine species), Hemiptera (34 species), Hymenoptera (104 species), Coleoptera (38 species), Diptera (113 species), and Lepidoptera (74 species). The Adar protein sequence of Drosophila melanogaster was downloaded from FlyBase (https://flybase.org/) version dm6.04 with protein ID FBpp0308381 (corresponding transcript ID: FBtr0339272, gene ID: FBgn0026086). The topology of the phylogenetic tree was retrieved from the TimeTree website (http://www.timetree.org/).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the 2115 Talent Development Program of the China Agricultural University for financial support. This study is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31922012), and the 2115 Talent Development Program of the China Agricultural University.

Author contributions: Conceptualization and supervision: W.C. and H.L. Data analysis: Y.D. and L.M. Writing—original draft: Y.D. and L.M. Writing—review and editing: Y.D, L.M., F.S., T.L., W.C., and H.L.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.079682.123.

MEET THE FIRST AUTHOR

Ling Ma.

Meet the First Author(s) is an editorial feature within RNA, in which the first author(s) of research-based papers in each issue have the opportunity to introduce themselves and their work to readers of RNA and the RNA research community. Ling Ma is a co-first author of this paper, “Autorecoding A-to-I RNA editing sites in the Adar gene underwent compensatory gains and losses in major insect clades.” Dr. Duan was introduced in a previous RNA paper; in this paper we introduce Ling Ma, who is a PhD student in the China Agricultural University with a bioinformatics background. She studies the evolutionary genomics of insects and also participates in the studies of A-to-I RNA editing with Dr. Yuange Duan.

What are the major results described in your paper and how do they impact this branch of the field?

A-to-I RNA editing is the most prevalent RNA modification in metazoans. Adar is the only enzyme responsible for A-to-I editing in insects. Adar mRNA has two autorecoding sites that regulate enzymatic activity. Our paper is the first study that clarifies the evolutionary trajectory of the two autorecoding sites in the whole insect clade.

What led you to study RNA or this aspect of RNA science?

A-to-I RNA editing could diversify the proteome in a flexible manner, adding phenotypic plasticity to the organisms, helping them to adapt to a changeable environment. This is the most fascinating part of studying RNA biology.

What are some of the landmark moments that provoked your interest in science or your development as a scientist?

When I published my first SCI paper on genome evolution, I felt excited and decided to be a good scientist in the future.

If you were able to give one piece of advice to your younger self, what would that be?

My advice to my younger self is spend more time thinking of scientific questions/stories and spend less time on technical issues.

Are there specific individuals or groups who have influenced your philosophy or approach to science?

Professor Wanzhi Cai's group provides me with the platform to do my genomic analyses. Drs. Hu Li, Fan Song, and Li Tian have taught me entomological knowledge, and Dr. Yuange Duan usually guides me with some evolutionary insights.

What were the strongest aspects of your collaboration as co-first authors?

Both co-first authors (Yuange Duan and Ling Ma) specialize in evolutionary genomics and bioinformatics. This makes a pleasant collaboration on this comparative genomic paper on Adar evolution.

REFERENCES

- Alon S, Garrett SC, Levanon EY, Olson S, Graveley BR, Rosenthal JJ, Eisenberg E. 2015. The majority of transcripts in the squid nervous system are extensively recoded by A-to-I RNA editing. Elife 4: e05198. 10.7554/eLife.05198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 421. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Dou S, Luo S, Zhang H, Lu J. 2017. Adaptation of A-to-I RNA editing in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 13: e1006648. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Dou S, Zhang H, Wu C, Wu M, Lu J. 2018. Linkage of A-to-I RNA editing in metazoans and the impact on genome evolution. Mol Biol Evol 35: 132–148. 10.1093/molbev/msx274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Dou S, Porath HT, Huang J, Eisenberg E, Lu J. 2021. A-to-I RNA editing in honeybees shows signals of adaptation and convergent evolution. iScience 24: 101983. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Tang X, Lu J. 2022. Evolutionary driving forces of A-to-I editing in metazoans. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 13: e1666. 10.1002/wrna.1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Cai W, Li H. 2023a. Chloroplast C-to-U RNA editing in vascular plants is adaptive due to its restorative effect: testing the restorative hypothesis. RNA 29: 141–152. 10.1261/rna.079450.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Li H, Cai W. 2023b. Adaptation of A-to-I RNA editing in bacteria, fungi, and animals. Front Microbiol 14: 1204080. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1204080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E, Levanon EY. 2018. A-to-I RNA editing—immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat Rev Genet 19: 473–490. 10.1038/s41576-018-0006-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett S, Rosenthal JJ. 2012. RNA editing underlies temperature adaptation in K+ channels from polar octopuses. Science 335: 848–851. 10.1126/science.1212795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gommans WM, Mullen SP, Maas S. 2009. RNA editing: a driving force for adaptive evolution? Bioessays 31: 1137–1145. 10.1002/bies.200900045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Zhang J. 2019. The preponderance of nonsynonymous A-to-I RNA editing in coleoids is nonadaptive. Nat Commun 10: 5411. 10.1038/s41467-019-13275-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Zhang W, Li Q. 2009. Origins and evolution of ADAR-mediated RNA editing. IUBMB Life 61: 572–578. 10.1002/iub.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30: 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan LP, McGurk L, Palavicini JP, Brindle J, Paro S, Li X, Rosenthal JJ, O'Connell MA. 2011. Functional conservation in human and Drosophila of metazoan ADAR2 involved in RNA editing: loss of ADAR1 in insects. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 7249–7262. 10.1093/nar/gkr423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khermesh K, D'Erchia AM, Barak M, Annese A, Wachtel C, Levanon EY, Picardi E, Eisenberg E. 2016. Reduced levels of protein recoding by A-to-I RNA editing in Alzheimer's disease. RNA 22: 290–302. 10.1261/rna.054627.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin RC. 1988. On measures of gametic disequilibrium. Genetics 120: 849–852. 10.1093/genetics/120.3.849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Zhao S, Li X, Miao Z, Cao J, Chen Y, Shi Z, Zhang J, Wang D, Chen S, et al. 2023. Cathepsin B S-nitrosylation promotes ADAR1-mediated editing of its own mRNA transcript via an ADD1/MATR3 regulatory axis. Cell Res 33: 546–561. 10.1038/s41422-023-00812-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liscovitch-Brauer N, Alon S, Porath HT, Elstein B, Unger R, Ziv T, Admon A, Levanon EY, Rosenthal JJC, Eisenberg E. 2017. Trade-off between transcriptome plasticity and genome evolution in cephalopods. Cell 169: 191–202.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O'Connell MA, Reenan RA. 2000. dADAR, a Drosophila double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase is highly developmentally regulated and is itself a target for RNA editing. RNA 6: 1004–1018. 10.1017/S1355838200000248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardi E, D'Erchia AM, Lo Giudice C, Pesole G. 2017. REDIportal: a comprehensive database of A-to-I RNA editing events in humans. Nucleic Acids Res 45: D750–D757. 10.1093/nar/gkw767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porath HT, Hazan E, Shpigler H, Cohen M, Band M, Ben-Shahar Y, Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Bloch G. 2019. RNA editing is abundant and correlates with task performance in a social bumblebee. Nat Commun 10: 1065. 10.1038/s41467-019-09543-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswami G, Li JB. 2014. RADAR: a rigorously annotated database of A-to-I RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D109–D113. 10.1093/nar/gkt996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapiro AL, Shmueli A, Henry GL, Li Q, Shalit T, Yaron O, Paas Y, Li JB, Shohat-Ophir G. 2019. Illuminating spatial A-to-I RNA editing signatures within the Drosophila brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116: 2318–2327. 10.1073/pnas.1811768116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savva YA, Jepson JE, Sahin A, Sugden AU, Dorsky JS, Alpert L, Lawrence C, Reenan RA. 2012a. Auto-regulatory RNA editing fine-tunes mRNA re-coding and complex behaviour in Drosophila. Nat Commun 3: 790. 10.1038/ncomms1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savva YA, Rieder LE, Reenan RA. 2012b. The ADAR protein family. Genome Biol 13: 252. 10.1186/gb-2012-13-12-252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoshan Y, Liscovitch-Brauer N, Rosenthal JJC, Eisenberg E. 2021. Adaptive proteome diversification by nonsynonymous A-to-I RNA editing in coleoid cephalopods. Mol Biol Evol 38: 3775–3788. 10.1093/molbev/msab154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Shiromoto Y, Minakuchi M, Nishikura K. 2021. The role of RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 13: e1665. 10.1002/wrna.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MH, Li Q, Shanmugam R, Piskol R, Kohler J, Young AN, Liu KI, Zhang R, Ramaswami G, Ariyoshi K, et al. 2017. Dynamic landscape and regulation of RNA editing in mammals. Nature 550: 249–254. 10.1038/nature24041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Zhou H, Kong Y, Pan B, Chen L, Wang H, Hao P, Li X. 2016. The landscape of A-to-I RNA editome is shaped by both positive and purifying selection. PLoS Genet 12: e1006191. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The genome accession IDs of the 377 arthropod species are provided in Supplemental Table S1. Our collection includes outgroup1 (Ixodida, one species), outgroup2 (Ephemeroptera and Odonata, four species), outgroup3 (Orthoptera, Phasmatodea, Plecoptera, and Blattodea, nine species), Hemiptera (34 species), Hymenoptera (104 species), Coleoptera (38 species), Diptera (113 species), and Lepidoptera (74 species). The Adar protein sequence of D. melanogaster was downloaded from FlyBase (https://flybase.org/) version dm6.04 with protein ID FBpp0308381 (corresponding transcript ID: FBtr0339272, gene ID: FBgn0026086). The topology of the phylogenetic tree was retrieved from the TimeTree website (http://www.timetree.org/).