Highlights

-

•

Confirmed the potential anticancer properties of lithium compounds, a medication safely used for decades, in treating pancreatic cancer.

-

•

For the first time, it has been demonstrated that lithium chloride induces apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress.

-

•

Indicating the Prospects of Metal Ion Pharmaceuticals in Cancer Treatment.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Targeted therapy, Natural medicine, Lithium

Abstract

Lithium compounds, a classic class of metal complex medicine that target GSK 3β and are widely known as mood-stabilizer, have recently been reported as potential anti-tumor drugs. The objective of this investigation was to explore the anticancer potential of lithium chloride (LiCl) and elucidate its mode of action in pancreatic cancer cells. The MTT, colony formation, and Edu assay were used to evaluate the impact of LiCl on pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Various methods were employed to investigate the anti-tumor activity of LiCl and its underlying mechanisms. Cell cycle analysis and apoptosis detection assays were utilized for in vitro experiments, while the orthotopic pancreatic cancer mouse model was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of LiCl treatment in vivo. Furthermore, the impact of LiCl on the proliferation of patient-derived organoids was also studied. The results demonstrated that LiCl inhibited the proliferation of pancreatic cancer (PC) cells, induced G2/M phase arrest, and activated apoptosis. Notably, the triggering of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by LiCl was observed, leading to the activation of the PERK/CHOP/GADD34 pathway, which subsequently promoted apoptosis in PC cells. In the future, Lithium compounds could become an essential adjunct in the treatment of human pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer continues to be a highly lethal malignancy, with projections suggesting it will be the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the coming decades [1]. Its incidence is also increasing in china [2]. Over 90 % of pancreatic cancer cases are due to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), which represents the primary type of pancreatic cancer [3]. PDAC exhibits the worst 5-year survival rate among common malignancies, primarily due to challenges in early diagnosis and its common chemoresistance [4]. While approximately 15 % of PDAC cases are amenable to curative surgery, both local and systemic recurrences are frequent after surgery. Patients who underwent surgery prior to receiving adjuvant chemotherapy have an average life expectancy limited to a range of 20 to 23 months [5]. Consequently, additional therapeutic options are urgently needed to treat this malignance.

Lithium compounds are commonly used for treatment of bipolar disorders with clinical relevance for more than 50 years [6] and are known for their ability to block the activity of the GSK-3α and β isoforms [7]. Lithium has been used in psychiatry since the mid-nineteenth century. After obtaining FDA (Food and Drug Administration) approval in 1970, lithium has primarily been utilized in the United States for managing bipolar disorder and remains the most frequently prescribed medication for this mental health condition [8]. Retrospective studies have shown that bipolar disorder patients receiving lithium therapy have a significant lower risk for cancer than those not treated with lithium [9], [10], [11], [12]. Recent studies have found that lithium salts can inhibit the proliferation and development of various tumors [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Existing research has demonstrated that lithium exerts most of its pharmacological effects by inhibiting the activity of some phosphate-transfer enzymes, including GSK3β, which require magnesium as a co-factor [19]. Tumor samples from PDAC patients demonstrated a gradual rise in GSK3β, which was associated with unfavorable prognostic outcomes [20,21]. Previous research has indicated that the hedgehog-GLI signaling pathway can be targeted by lithium to inhibit the tumorigenic potential of PDAC cells [22]. However, the efficacy and mechanism of GSK3β inhibitor lithium impacts on PDAC cells deserves a deeper understanding and study.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a dynamic structure essential for various cellular processes, including calcium storage, protein synthesis, and lipid metabolism [23]. Stresses such as famine, hypoxia, oxidative damage, depletion of Ca2+, fluctuations in pH, ATP depletion, virus infections, and hypoglycemia can disrupt ER homeostasis [24]. Endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction leads to the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR), resulting in a significant accumulation of misfolded proteins. The buildup of these proteins can induce ER stress in an attempt to maintain endoplasmic reticulum stability. However, when the stress intensity exceeds a certain threshold and becomes unmanageable, ER stress triggers a cell death process [25]. Specifically, three major proteins located in the ER lumen are responsible for UPR activation: pancreatic eIF2-α kinase (PERK) [26], high inositol-requiring 1 (IRE1-α) [27], and ATF6 [28]. Accumulating evidence implicates the mechanism of many anticancer drugs in relation to endoplasmic reticulum stress [29]. Additionally, metallic complexes with redox capability and interchanging structures are emerging as promising anti-tumor agents by targeting ER stress [30]. Therefore, we identified endoplasmic reticulum stress as a potential mechanism underlying lithium's anticancer effects.

Our research, for the first time, highlights the crucial role of endoplasmic reticulum activation in lithium treatment for PDAC, both in vivo and in vitro. Lithium compounds may serve as a suitable complementary strategy for the increase of effectiveness of PDAC therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

In the cell culture experiment, four human PC cell lines, CFPAC-1, HPAF2, MIAPACA2 and PSN-1 were purchased from ATCC. Murine pancreatic cell line MT5 (KrasLSL-G12D, Trp53LSL-R270H, Pdx1-cre) was a gift from David Tuveson (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY). MT5-luc cell line established by transduction of luciferase-expression lentiviral constructs with enhanced firefly luciferase to MT5 was a gift from YAN CHAO Lab, Nanjing University, China. According to the instructions from ATCC, cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Beijing, China) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) (AusGneX, Molendinar, Australia) or in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Beijing, China) supplemented with 10 % FBS (AusGneX, Molendinar, Australia), and incubated at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere.

Human pancreatic tumor organoid culture and drug treatment

Organoids were isolated and cultured using Tuveson's protocols [31]. After being embedded in GFR Matrigel, the cells were cultured in a complete medium, which was refreshed every three days. After a 15-min digestion with TrypLE (GIBCO) at 37 °C, the organoids were incorporated into GFR Matrigel.

To study the effects of lithium treatment on organoids, the cells were first seeded into 48-well plates and allowed to recover for seven days before being subjected to lithium treatment. Subsequently, the organoids were subjected to a medium that consisted of a range of LiCl concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, or 80 mM) for seven days, during which they were imaged every three days. Finally, CellTiter-Glo 3D Reagent (Promega, Madison, USA) was used to determine the viability of the cells, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Reagents and antibodies

Lithium chloride (#L9650-100G) and ISRIB (#SML-0843-5MG) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Other reagents included Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (#T818538-25g) from MACKLIN (Shanghai China), BeyoClick™ EdU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 594 (#C0078L), RIPA Buffer (#P0013C), and PMSF (#ST506) from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). The Pierce BCA Protein Assay kit (#23227) was obtained from Thermo (Rockford, USA). Antibodies used for western blot, immunofluorescence, and immunofluorescence included caspase-3 (9664S), cleaved caspase-3 (#9664), PARP (#9542), Bcl-2 (#3498), BAX (#5023), ATF4 (#11815),eIF2α(#5324) and p-eIF2α (#3398) purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (CST, Beverly, MA, USA), and PERK (20582-1-AP), BiP (11587-1-AP), CHOP (15204-1-AP), GADD34 (10449-1-AP), and Ki67 (27309-1-AP) purchased from ProteinTech Group (ProteinTech, Chicago, IL, USA). All antibodies were diluted according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell viability assay

To begin with, 5000 PC cells were seeded in each well of a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h. The cell viability assay was performed using Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) after treating the cells with various concentrations of lithium chloride for 24, 48 or 72 h. After incubation with 100 μl medium containing 10 μl MTT for 4 h, the absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a SPECTROstar Nano instrument (SpectraMax M4, Molecular Devices, USA). The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, USA).

Colony formation assay

Following treatment with varying concentrations of LiCl (0 or 20 mM) for 24 h, a colony formation assay was conducted according to previous protocols [32]. Colony density and area were measured using the ColonyArea plugin in ImageJ (US National Institutes of Health) [33].

EdU detection

Cell proliferation in PC cells was assessed by treating them with different concentrations of LiCl for 48 h, followed by EdU staining using the BeyoClick™ EdU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 594 (C00788S; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (TCS SP8-MP, Leica).

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

PC cells were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with varying concentrations of LiCl for 48 h. Following incubation, cells were harvested and subjected to staining with PI (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. FlowJo software version 10.0 was utilized to determine the percentage of cells in each phase of the cell cycle.

Cell apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry

Following treatment with various concentrations of LiCl for 48 h, cells were harvested and subjected to the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry (Attune NxT, Thermo Fisher, USA) was used to analyze the samples, and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 10.0.

Immunofluorescence analysis

PC cells were cultured on sterile glass cover slips in 24-well plates and treated with various concentrations of LiCl for 24 h. After fixing the cells with 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min and permeabilizing them with 0.2 % Triton X-100 for 15 min, the cells were blocked with 5 % BSA for 30 min. The cells were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies protected from light at 37 °C for 60 min. TUNEL staining was performed using the TUNEL BrightGreen Apoptosis Detection Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The cells were observed under a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 880, ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany or TCS SP8-MP, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and the images were analyzed using ImageJ software (Rawak Software Inc., Stuttgart, Germany).

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated and then washed with cold PBS (Gibco, Beijing, China) prior to lysing in RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) on ice for 30 min. After centrifuging the cell lysates for 15 min (12,000 g at 4 °C), the supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations were measured utilizing the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific. Following this, equivalent protein quantities were separated using 6.0 % to 12.5 % SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto PVDF membranes acquired from MilliporeSigma. Membranes underwent blocking in TBST containing 5 % skimmed milk, followed by the addition of primary antibodies and an overnight incubation at 4 °C. Subsequently, a 1-h incubation with HRP-linked secondary antibodies was performed, and protein detection was carried out using the Tanon™ High-sig ECL Western Blotting Detection System (Tanon, #180-5001). The membranes were then detected with a Tanon imaging system (Tanon, #5200s).

RNA sequencing

Cells were treated with or without 20 mM LiCl for 24 h, and the complete RNA was isolated from the cells utilizing the TRIzol agent (Invitrogen Life Technologies). RNA purification, library construction, and sequencing were performed by Majorbio Biotech, including mRNA isolation using the polyA selection method with oligo (dT) beads, cDNA synthesis from random hexamer primers (Illumina) using the SuperScript double-stranded cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, CA), and paired-end library sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing system.

Orthotopic studies

Immunocompetent male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Gempharmatech Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (20201105). The experimental animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle and at a temperature of 24 ± 2 °C, with free access to food and water. The orthotopic experiments were conducted by administering a 50-microliter cell suspension with 5 × 104 MT5-luc cells directly into the pancreatic tissue, based on the orthotopic guide by Erstad et al. [34]. The growth of tumors was evaluated weekly with the IVIS Lumina LT In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer, USA). The mice were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation following an intraperitoneal administration of 150 mg/kg D-luciferin, and bioluminescent readings were processed using the Living Image software (PerkinElmer, USA). Seven days post-orthotopic surgery, mice were assorted into two distinct groups according to their bioluminescence intensity: control (n = 9) and LiCl (n = 9) treatment. The LiCl group received intraperitoneal injections of 150 mg/kg/day LiCl dissolved in 200 μl ddH2O, while the control group received intraperitoneal injections of 150 mg/kg/day NaCl dissolved in 200 μl ddH2O following the same procedure.

Immunohistochemistry

The orthotopic tumors were isolated from mice and fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde diluted with 0.1 M PBS at room temperature. Following washing and dehydration in graded ethanol (70–100 %), The neoplastic specimens were encased in paraffin before being sectioned into slices measuring 5 micrometers in thickness. The process of antigen retrieval involved heating tissue samples in a Tris-EDTA solution using a microwave for a duration of 10 min, followed by a subsequent 3 % hydrogen peroxide treatment. The sections were then incubated with anti-Ki67 primary antibody (1:200 dilution) overnight at 4 °C, followed by secondary antibody and DAB (BOSTER, China). The stained sections were evaluated based on staining intensity (0–3) and extent of stained cells (0–4) and assigned a total score (0–12) by multiplying staining intensity and extent of stained cells. Cells with total score ≥8 were considered as positive cells. The calculation for the proportion of Ki67 positive cells was determined using this formula: Proportion of Ki67 positive cells (in %) = (Number of Ki67 positive cells / Total number of cells) × 100 %.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

After 48 h of LiCl treatment, PC cells were fixed overnight with a 2.5 % glutaraldehyde solution with 1 % osmium tetroxide for 2 h. The samples were then dehydrated using alcohol, embedded in Epon resin, and visualized using TEM (Hitachi H-7650, Tokyo, Japan).

Data collection and online tools

The mRNA expression data were downloaded from the GEO database, including microarray files GSE62452, GSE28735, GSE15471, and GSE43288. GSE62452 comprises 69 pancreatic malignancies and 61 surrounding non-cancerous tissues from individuals with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The GSE28735 dataset comprises 45 pairs of primary and neighboring malignant tissue samples obtained from individuals with PAAD while GSE15471 features 36 sets of primary and neighboring malignant tissue samples. GSE43288 includes 13 PanIN samples, 3 normal pancreases samples and 4 PDAC samples. The Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma dataset (TCGA-PAAD) from The Cancer Genome Atlas was combined with data obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project to investigate variations in the expression of GSK3β. This analysis was conducted on GEPIA [35]. The GSK3β ROC curve based on the TCGA-PAAD data combined with GTEx data, GSK3β gene expression comparison based on the GEO data and the OS and DFS analysis of TCGA-PAAD data were performed on online Xiantao tool. The OS analysis of GSE28735 and ICGC_Array were performed on OSpaad [36].

Statistical analysis

Every experiment was conducted a minimum of three times, with the findings expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The statistical evaluations involved unpaired t-tests to assess distinctions between two groups, one-way ANOVA with a subsequent Tukey's test for comparing three or more groups, and the application of Spearman's rank-order correlation technique to determine the relationship between two sets. Survival data were represented through Kaplan–Meier curves, which were then contrasted using the log-rank method. A p-value below 0.05 was deemed to indicate statistical significance.

Results

GSK3β is highly expressed in PDAC and associated with shorter survival

To study the expression of GSK3β in PDAC, the TCGA-PAAD data combined with GTEx data was analyzed, aberrant overexpression of GSK3β was implicated in PDAC (Fig. 1(a)). Additionally, The ROC curve demonstrated GSK3β's robust ability to distinguish between PDAC and normal pancreas samples using TCGA and GTEx datasets, with an AUC of 0.983, suggesting its potential as an exceptionally effective diagnostic biomolecule (Fig. 1(b)). Three GEO (GSE62452, GSE28735, and GSE5471) datasets owning PC tissue samples and adjacent non-cancerous tissue samples were extracted (Fig. 1(c)–(e)). GSK3β was markedly upregulated in PC tissue samples compared to non-cancerous tissue samples. The GEO dataset (GSE43288) further revealed significant differences between normal samples and either Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) or PDAC samples, with a significant increase observed from the PanIN to the PDAC samples (Fig. 1(f)). Significant difference was found in the comparison of DFS by K–M curve based on the TCGA dataset (Fig. 1(g)). Moreover, survival data analysis demonstrated a significant negative correlation between GSK3β expression levels and overall survival in the ICGC_Array and GSE28735 datasets, as shown by the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of OS (Fig. 1(g), (h)). Taken together, these results suggest that GSK3β may be associated with PDAC progression, and GSK3β inhibitors, such as lithium compounds, could potentially serve as treatments for pancreatic cancer.

Fig. 1.

GSK3β is highly expressed in PDAC tissues and associated with shorter survival. (a) GSK3β's median expression was examined through RNA-seq data including 171 healthy pancreatic samples and 179 pancreatic tumor samples acquired from the GTEX and TCGA. Pancreatic tumors had a median GSK3β expression of 14.97, while normal pancreatic tissues had a median expression of 2.97. (b) ROC curve analysis was employed to evaluate the diagnostic potential of GSK3β in the TCGA-GTEx PAAD cohort. (c–e) GSK3β expression in matched tumor and healthy tissues was examined by scrutinizing the transcriptome of dataset GSE62452 (n = 61 paired PAAD tumor samples with adjacent normal pancreatic tissues), GSE28735 (n = 45), and GSE15471 (n = 36). (f) Comparison of GSK3β mRNA normalized expression in the GSE43288 dataset among normal pancreas (n = 3), PanIN (n = 13), and pancreatic tumor tissues (n = 4). (g) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of DFS and OS based on GSK3β mRNA expression in the TCGA-PAAD dataset. (h) Kaplan–Meier survival evaluations for OS were carried out based on GSK3β mRNA expression in the GSE28735 and ICGC_Array datasets. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

LiCl inhibits the growth and proliferation of PC cell lines and PC organoids in vitro

In order to investigate the impact of LiCl on the growth of various PC cell lines, four separate PC cell lines were subjected to escalating LiCl concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 mM) over a duration of 48 h. The MTT assay was employed to assess cell viability. After 48 h of LiCl exposure, a notable decline in PC cell survivability was observed (Fig. 2(a)). The IC50 values of LiCl in these PC cell lines were determined as follows: 17.01 mM (CFPAC-1), 29.55 mM (HPAF2), 38.21 mM (MIAPACA2), and 19.17 mM (PSN-1). CFPAC-1 and PSN-1 were selected for subsequent experimentation. These cell lines were treated with increasing LiCl concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, or 80 mM) for 24, 48, or 72 h. In each cell type, inhibitory effects were observed to be both dose- and time-dependent (Fig. 2(a), (c)). To validate the anti-proliferative properties of LiCl on PC cell proliferation, colony formation assays were conducted. Notable differences between control and LiCl-treated cells were observed after a 7-day experiment, with LiCl treatment causing a significant reduction in colony area (Fig. 2(d), (e)). Furthermore, the EdU incorporation assay was taken to determine cell proliferation rates with or without LiCl treatment. The presence of EdU intensity within cells is indicative of the active proliferation of cells. In this study, the concentration of LiCl was found to be inversely proportional to the percentage of labelled cells in both CFPAC-1 and PSN-1 cell lines (Fig. 2(f), (g)). Additionally, three patient-derived PC organoids treated with varying LiCl concentrations exhibited significant inhibitory effects (Fig. 2(h)). The findings suggest that treating PC cell lines and PC organoids with LiCl leads to significant anti-proliferative outcomes in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

Fig. 2.

LiCl inhibits the viability and proliferation of PC cell lines and PC organoids in vitro. (a) MTT assay was used to measure cell viability of 4 PC cell lines underwent treatment with varying LiCl concentrations for 48 h. (b, c) Graphs illustrating the percentage inhibition of PC cells in relation to dose and duration. CFPAC-1 and PSN-1 cells were exposed to different concentrations (0–80 mM) for 24, 48, or 72 h. (d, e) The colony formation of PC cell lines was assessed with 0, or 10 mM LiCl treatments for a duration of 24 h, followed by 7 days of culture. (f, g) CFPAC-1 and PSN-1 were treated with LiCl (0,5,10,20 mM) for 48 h, and The Edu incorporation assay was employed to investigate DNA synthesis. (h) PC organoids from three patients imaged using phase-contrast microscopy. Data, expressed as mean ± SD, were derived from three separate experiments. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

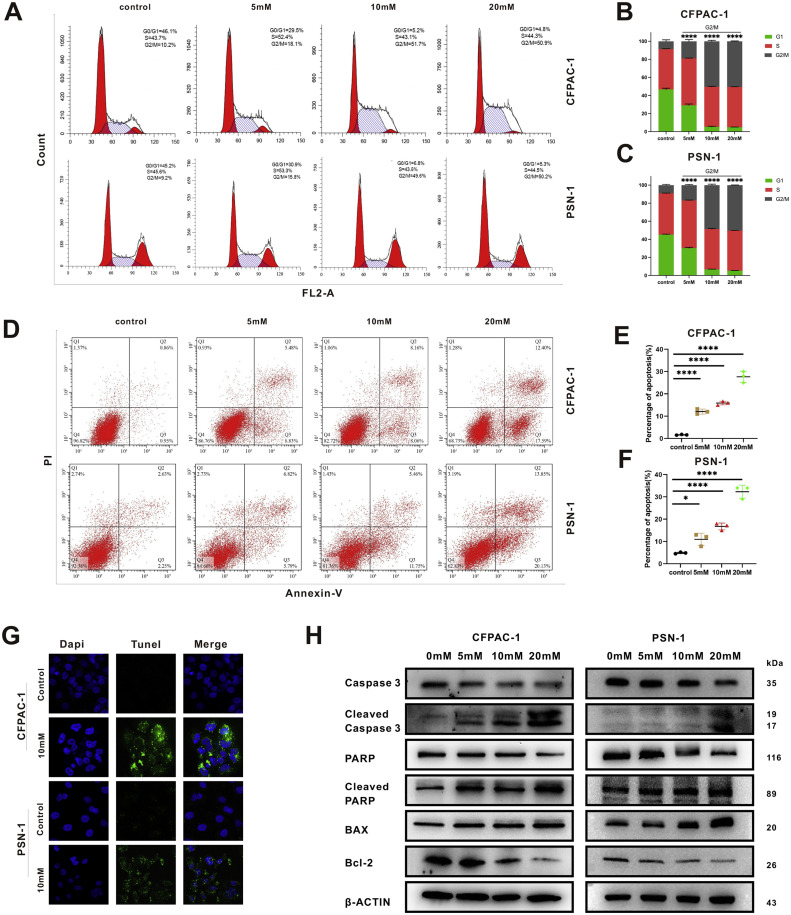

LiCl triggers G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in PC cell lines

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the growth-inhibiting effects of LiCl, flow cytometric analysis was employed to assess its impact on cell cycle progression. The analysis involved PI-stained CFPAC-1 and PSN-1 cells subjected to different LiCl concentrations for 24 h (Fig. 3(a)). A dose-responsive increase of G2/M phase proportion and a corresponding decrease in G1 phase proportion were noted (Fig. 3(b), (c)). Simultaneously, CFPAC-1 and PSN-1 were treated with LiCl in various concentrations for 24 h before Annexin-V-FITC and PI staining (Fig. 3(d)). A dose-responsive elevation in apoptotic cell percentages was revealed by flow cytometry assessment (Fig. 3(e), (f)). To confirm that the impact on PC cell lines was due to apoptosis induced by LiCl, the TUNEL assay was performed. Compared with the control groups, the treatment groups showed a strong apoptotic signal both in CFPAC-1 and PSN-1 cell lines (Fig. 3(g)). In addition, western blot analysis revealed dose-responsive upregulation of cleaved PARP, BAX and cleaved caspase 3 expression, alongside with downregulation of caspase 3 and Bcl-2 expression, signifying successful induction of apoptosis in the tested cell lines (Fig. 3(h)). Totally, these results provide evidence that LiCl triggers apoptosis and G2/M phase arrest in PDAC cells in a dose- responsive manner.

Fig. 3.

LiCl triggers G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in PC cell lines. (a–c) G2/M phase arrest triggered by LiCl administration. Post 24-h LiCl exposure, cells underwent flow cytometry analysis following PI staining. (d–f) Apoptosis induction by LiCl, ascertained through flow cytometry. After a 24-h LiCl exposure, cells were stained by Annexin-V-FITC and PI. (g) The TUNEL assay was carried out to verify the apoptosis induced by LiCl treatment. (h) Western blot experiments demonstrated dose-dependent changes in several apoptosis-related indicators. Data, expressed as mean ± SD, were derived from three separate experiments. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

LiCl induced apoptosis via activation of ER stress

To investigate the underlying mechanism through which LiCl induces proapoptotic effects in PC cells, RNA sequencing was performed to reveal gene expression changes in the PSN-1 cell line treated with or without 20 mM LiCl for 24 h. Significant changes in gene expression were revealed by RNA-sequencing analysis (Fig. 4(a)). Based on cutoff log2 (fold change) > 1.2, 2952 upregulated genes as well as 2790 downregulated genes were identified. CHOP (DDIT3), a well-known ER stress indicator, was significantly upregulated as well as GADD34 (PPP1R15A), a target gene of the UPR which is activated by CHOP (Fig. 4(b)). The analysis of gene ontology (GO) enrichment highlighted a notable overrepresentation of several modules across diverse GO categories (Fig. 4(c)). Several signaling pathways associated with ER stress was led by LiCl treatment, as indicated by the GO analysis (Fig. 4(d)). Anticancer drugs often induce cancer cell apoptosis by causing ER stress. Therefore, we hypothesized that ER stress might be involved in the initiation of apoptosis in PC cell lines. To further confirm this, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) was used to observe the cell microstructural changes after LiCl-treatment. TEM imaging revealed swollen endoplasmic reticulum, indicative of ER stress, as well as highly condensed chromatin (CC), indicative of apoptosis, in the LiCl-treated cells, suggesting the occurrence of ER stress and apoptosis caused by LiCl (Fig. 4(e)). Double-staining of TUNEL and CHOP was performed after PSN-1 and CFPAC-1 were treated with LiCl (20 mM) for 24 h. A dose-dependent Increase of TUNEL staining co-localized with CHOP immunoreactivity was observed under confocal microscope (Fig. 4(f)). Additionally, a dose-dependent increase in the expression of ER stress pathway key proteins, such as BiP, PERK, ATF4, eIF2α, p-eIF2α, CHOP and GADD34, was observed in the LiCl-treated group (Fig. 4(g)). Simultaneously, the endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibitor, ISRIB [37], targeting p-eIF2α and its downstream effectors CHOP and GADD34, was employed. Through Western blot and TUNEL experiments, effective attenuation of lithium chloride-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis by ISRIB was observed (Fig. 4(h), (i)). Collectively, the obtained findings collectively establish that LiCl triggers apoptosis in PC cell lines via the activation of ER stress.

Fig. 4.

LiCl induces apoptosis via activation of ER stress. (a) RNA-sequencing unveiled a significant change in gene expression. Heat map showed the genes significantly influenced by LiCl treatment (20 mM, 24 h) compared to the control group. (b) A volcano plot illustrates the differentially expressed genes, with downregulated genes marked in blue while upregulated genes marked in red. Notably, CHOP(DDIT3) and PPP1R15A(GADD34) are emphasized in the plot. (c) Differentially expressed mRNAs were linked to various GO terms via GO enrichment analysis. (d) ER stress-related signaling pathways were activated in the LiCl-exposed group. (e) Swollen endoplasmic reticulum (red asterisk labeled) was observed in the transmission electron microscope images of LiCl-treated cell. Apoptotic body with highly condensed chromatin (CC) was also observed in LiCl-treated cell. Normal endoplasmic reticulum was labeled by red arrows. (f) Double-label staining of CHOP (red) and TUNEL (green). (g) Western blot analysis of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers in two PC cell lines. (h) Western blot analysis of key endoplasmic reticulum stress markers and cleaved PARP in two PC cell lines. Cells were either left untreated, treated with LiCl(20 mM), treated with ISRIB(250 nM), or subjected to a combination of both for 48 h. (i) TUNEL assays were performed. Cells were either left untreated, treated with LiCl(20 mM), treated with ISRIB(250 nM), or subjected to a combination of both for 48 h.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

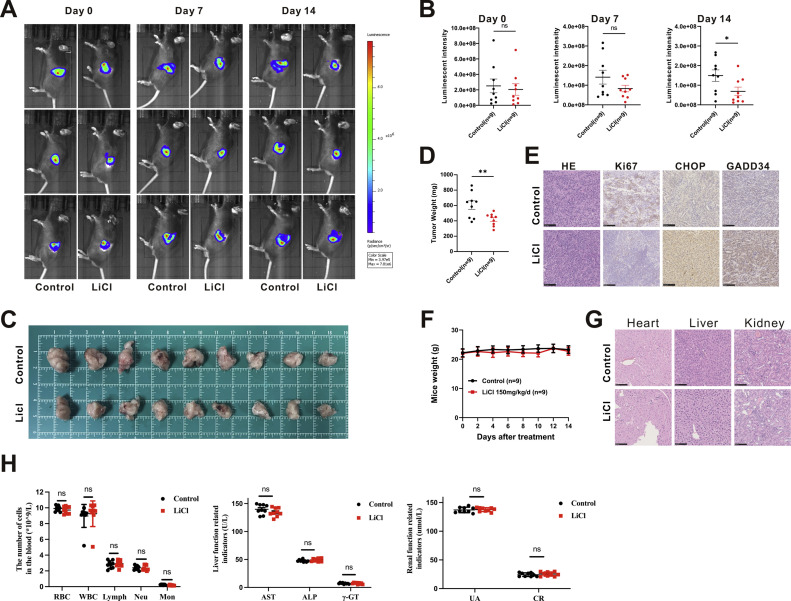

LiCl inhibits PC cell tumorigenesis in vivo

To evaluate the impact of LiCl on tumorigenesis in vivo, orthotopic implantation experiments were conducted. Mice (n = 18) were implanted with 5 × 104 MT5-luc cells in the pancreas. IVIS imaging was performed to confirm the presence of tumors seven days post-implantation (Fig. 5(a)). The Mice were then evenly distributed into two groups based on their tumor luminescent intensity captured in IVIS images. Mice in the treatment group (n = 9) received LiCl, while those in the control group (n = 9) received NaCl in a dose of 150 mg/kg/day dissolved in 200 μl of ddH2O. The treatments were administered via intraperitoneal injection for 14 days before sacrifice. The luminous intensity of each group was compared once a week to assess the statistical differences between the two groups until the endpoint, revealing a significant disparity in luminescent intensity before sacrifice on day 14 (Fig. 5(b)). Furthermore, the tumor weight was markedly reduced in the LiCl group compared to the control group (Fig. 5(c), (d)). Immunohistochemical analysis was employed to measure the expression levels of CHOP, GADD34, as well as proliferation marker (Ki67). Decreased Ki67 expression and increased CHOP and GADD34 expression were observed in tumor sections from treatment group compared to the control group (Fig. 5(e)). To verify the safety of LiCl on mice, the body weight changes of the mice in two groups were compared, and no statistical difference was found (Fig. 5(f)). Furthermore, no histological changes were observed in important target organs such as the heart, liver, and kidney (Fig. 5(g)). Additionally, blood tests including kidney function tests and liver function tests also showed no significant changes (Fig. 5(h)). Collectively, these results align with in vitro findings and suggest that LiCl demonstrates potent antitumor effects in a pancreatic cancer orthotopic mouse model by inducing ER stress.

Fig. 5.

LiCl inhibits PC cell tumorigenesis in vivo. (a) IVIS images were obtained once a week after implantation. (b) Luminous intensity of photons emitted from each tumor in the IVIS images was quantified. (c) Images of orthotopic MT5-luc tumors after treatment. A group of 18 mice were split into two subgroups and administered either LiCl (150 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally) or NaCl (150 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneally) for a duration of 14 days. (d) Bodyweight changes of mice during drug administration. (e) The weights of excised tumors from individual mice. (f) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC) examinations for Ki67, CHOP, and GADD34 in the tumor samples. (g) HE staining of cardiac, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary tissues from the mice. (h) Comprehensive blood cell analysis and main examination of kidney and liver function before sacrifice.

Discussion

While immunotherapy and other emerging treatment methods have provided hope for cancer treatment, pancreatic cancer still ranks among the top causes of cancer-related deaths globally [38]. Existing treatment options need to be effectively supplemented until a revolutionary treatment option is discovered. Therefore, our work may serve as an effective complement to existing treatment options.

Lithium compounds have been demonstrated to possess broad-spectrum antitumor activity in bipolar disorder patients by targeting GSK3β. However, whether lithium has a direct ability to inhibit tumor growth is not entirely clear. In both in vivo and in vitro experiments, lithium suppressed PDAC tumor cells growth, as demonstrated by our findings. We hypothesized that the antitumor effects of the treatment were due to an unknown mechanism other than targeting GSK3β. LiCl triggers cell death in human choroidal melanoma cells through the CHOP/NOXA/Mcl-1 pathway [23]. Similarly, we observed that in our research, the proapoptotic factor BAX increased, while the antiapoptotic factor Bcl-2 was reduced, along with the activation of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 3, which play critical roles in the caspase family. Thus, it is hypothesized that LiCl triggers the apoptotic process in PC cells.

ER stress exhibits as a double-edged sword in tumors [39]. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and ensuring accurate protein synthesis. Subjecting cells to the adverse external conditions results in the buildup of improperly folded or unfolded proteins in the ER, leading to ER stress. Several drugs, including bortezomib [40], suffruticosa aqueous extracts [41] and apatinib [42], cause ER stress and ultimately leading to apoptosis. Similar to these findings, our studies also revealed that LiCl induced an increase in PERK, which initiates ER stress. EIF2α which is in the downstream of PERK is reported to be activated by the accumulation of PERK in the form of phosphorylation. Upregulation of p-eIF2α can activate downstream ATF4, leading to increased transcription factor CHOP expression. Apoptosis is finally induced by the accumulation of GADD34 and the reduction of Bcl-2 which are influenced controlled by CHOP [43] (Fig. 6). We obtained the same phenomena and mechanisms in both in vivo and in vitro experiments. Simultaneously, we employed an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress inhibitor, ISRIB, which specifically targets CHOP and GDADD34, both of which played crucial roles in our study, effectively reversing the occurrence of this phenomenon. Therefore, in our study, we demonstrated that ER stress is triggered by LiCl. In turn, an increase in apoptosis was subsequently promoted by ER stress in PC cells.

Fig. 6.

A schematic representation demonstrates the antineoplastic properties of lithium in pancreatic cancer cells. Lithium triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress and initiates the activation of the PERK/CHOP/GADD34 cascade, ultimately leading to increased PC cell death through enhanced expression of GADD34.

With a long-standing history of safe usage, lithium compounds inherently possess safety advantages as potential candidates for anticancer drugs. In the context of prevailing clinical applications primarily focused on psychiatry, the side effects of lithium preparations are predominantly associated with systems such as the urinary, digestive, and endocrine systems. The most severe among these side effects is interstitial nephropathy, commonly emerging after a decade or two of medication [44]. Given the aggressive nature of pancreatic cancer, these side effects seem tolerable under vigilant monitoring and potential benefits. However, bridging the gap between the human tumor microenvironment and animal tumor models introduces a significant challenge in maintaining adequate blood drug concentrations within human tumor tissue during clinical deployment. Exploring the therapeutic potential of lithium preparations against pancreatic cancer could potentially gain momentum through diverse animal tumor models in the future. Simultaneously, the augmentation of targeted therapeutic efficacy might involve the integration of technologies such as nanoparticle technology [45,46] to further enhance their precision and impact.

Conclusions

In summary, our study has unveiled the inhibitory impact of lithium chloride (LiCl) on PDAC cells, both in vitro and in vivo. We have elucidated that the primary mechanism driving LiCl-induced apoptosis in PDAC cells is ER stress. Collectively, these insights from our study provide a solid foundation for considering lithium as a promising therapeutic option for PDAC and pave the way for further exploration in the field of pancreatic cancer treatment.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hao Wu: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Yin Zhang: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. Jiawei Liang: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization. Jianzhuang Wu: Methodology, Software. Yixuan Zhang: Methodology, Software. Haochen Su: Methodology, Software. Qiyue Zhang: Methodology, Software. Yonghua Shen: Resources. Shanshan Shen: Resources. Lei Wang: Writing – review & editing. Xiaoping Zou: Writing – review & editing. Cheng Hang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Shu Zhang: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Ying Lv: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101792.

Contributor Information

Cheng Hang, Email: hc5626@suda.edu.cn.

Shu Zhang, Email: zhangsgastro@nju.edu.cn.

Ying Lv, Email: lvying@njglyy.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Mizrahi J.D., Surana R., Valle J.W., Shroff R.T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2020;395:2008–2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30974-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng R., et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. J. Natl. Cancer Center. 2022;2:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orth M., et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: biological hallmarks, current status, and future perspectives of combined modality treatment approaches. Radiat. Oncol. 2019;14:141. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1345-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Springfeld C., et al. Chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. La Presse Médicale. 2019;48:e159–e174. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2019.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari D., Gustafsson A., Andersson R. Update on the management of pancreatic cancer: surgery is not enough. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3157–3165. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Licht R.W. Lithium: still a major option in the management of bipolar disorder. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012;18:219–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freland L., Beaulieu J.-M. Inhibition of GSK3 by lithium, from single molecules to signaling networks. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2012;5:14. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shorter E. The history of lithium therapy. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:4–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen Y., Chetrit A., Cohen Y., Sirota P., Modan B. Cancer morbidity in psychiatric patients: influence of lithium carbonate treatment. Med. Oncol. 1998;15:32–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02787342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinsson L., Westman J., Hällgren J., Ösby U., Backlund L. Lithium treatment and cancer incidence in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18:33–40. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang R.-Y., Hsieh K.-P., Huang W.-W., Yang Y.-H. Use of lithium and cancer risk in patients with bipolar disorder: population-based cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2016;209:393–399. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.181362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anmella G., et al. Risk of cancer in bipolar disorder and the potential role of lithium: international collaborative systematic review and meta-analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021;126:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazor M., Kawano Y., Zhu H., Waxman J., Kypta R.M. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 represses androgen receptor activity and prostate cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2004;23:7882–7892. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duffy D.J., Krstic A., Schwarzl T., Higgins D.G., Kolch W. GSK3 inhibitors regulate MYCN mRNA levels and reduce neuroblastoma cell viability through multiple mechanisms, including p53 and Wnt signaling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:454–467. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0560-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao Q., Lu X., Feng Y.-J. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta positively regulates the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells. Cell Res. 2006;16:671–677. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H., et al. Lithium chloride suppresses colorectal cancer cell survival and proliferation through ROS/GSK-3β/NF-κB signaling pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014;2014:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/241864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L., et al. Lithium chloride promotes apoptosis in human leukemia NB4 cells by inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2015;12:805–810. doi: 10.7150/ijms.12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q., Zhang Q., Li H., Zhao X., Zhang H. LiCl induces apoptosis via CHOP/NOXA/Mcl-1 axis in human choroidal melanoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:96. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakobsson E., et al. Towards a unified understanding of lithium action in basic biology and its significance for applied biology. J Membr Biol. 2017;250:587–604. doi: 10.1007/s00232-017-9998-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pecoraro C., et al. GSK3β as a novel promising target to overcome chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Drug Resist. Updates. 2021;58 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2021.100779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding L., Billadeau D.D. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β: a novel therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2020;24:417–426. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1743681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng Z., et al. Lithium inhibits tumorigenic potential of PDA cells through targeting hedgehog-GLI signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz D.S., Blower M.D. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016;73:79–94. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2052-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori K. The unfolded protein response: the dawn of a new field. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2015;91:469–480. doi: 10.2183/pjab.91.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szegezdi E., Logue S.E., Gorman A.M., Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:880–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McQuiston A., Diehl J.A. Recent insights into PERK-dependent signaling from the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. F1000Res. 2017;6:1897. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12138.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams C.J., Kopp M.C., Larburu N., Nowak P.R., Ali M.M.U. Structure and molecular mechanism of ER stress signaling by the unfolded protein response signal activator IRE1. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019;6:11. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haze K., Yoshida H., Yanagi H., Yura T., Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Healy S.J.M., Gorman A.M., Mousavi-Shafaei P., Gupta S., Samali A. Targeting the endoplasmic reticulum-stress response as an anticancer strategy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009;625:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King A.P., Wilson J.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: an arising target for metal-based anticancer agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:8113–8136. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00259c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boj S.F., et al. Organoid models of human and mouse ductal pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2015;160:324–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., et al. Hesperadin suppresses pancreatic cancer through ATF4/GADD45A axis at nanomolar concentrations. Oncogene. 2022;41:3394–3408. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzmán C., Bagga M., Kaur A., Westermarck J., Abankwa D. ColonyArea: an ImageJ plugin to automatically quantify colony formation in clonogenic assays. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erstad D.J., et al. Orthotopic and heterotopic murine models of pancreatic cancer and their different responses to FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018;11 doi: 10.1242/dmm.034793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Z., et al. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucl. Acids Res. 2017;45:W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang G., et al. OSpaad: an online tool to perform survival analysis by integrating gen e expression profiling and long-term follow-up data of 1319 pancreatic carcinoma patients. Mol. Carcinog. 2020;59:304–310. doi: 10.1002/mc.23154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidrauski C., et al. Pharmacological brake-release of mRNA translation enhances cognitive memory. Elife. 2013;2:e00498. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sung H., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siwecka N., et al. Dual role of endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated unfolded protein response signaling pathway in carcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:4354. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selimovic D., et al. Bortezomib/proteasome inhibitor triggers both apoptosis and autophagy-dependent pathways in melanoma cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y.-H., et al. Aqueous extracts of Paeonia suffruticosa modulates mitochondrial proteostasis by reactive oxygen species-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2018;46:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng H., et al. Apatinib-induced protective autophagy and apoptosis through the AKT-mT. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1030. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1054-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu H., Tian M., Ding C., Yu S. The C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) transcription factor functions in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and microbial infection. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:3083. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferensztajn-Rochowiak E., Rybakowski J.K. Long-term lithium therapy: side effects and interactions. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023;16 doi: 10.3390/ph16010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J.-J., Zhang W.-C., Guo Y.-W., Chen X.-Y., Zhang Y.-N. Metal nanoparticles as a promising technology in targeted cancer treatment. Drug Deliv. 2022;29:664–678. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2039804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neha D., et al. Metallic nanoparticles as drug delivery system for the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021;18:1261–1290. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2021.1912008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.