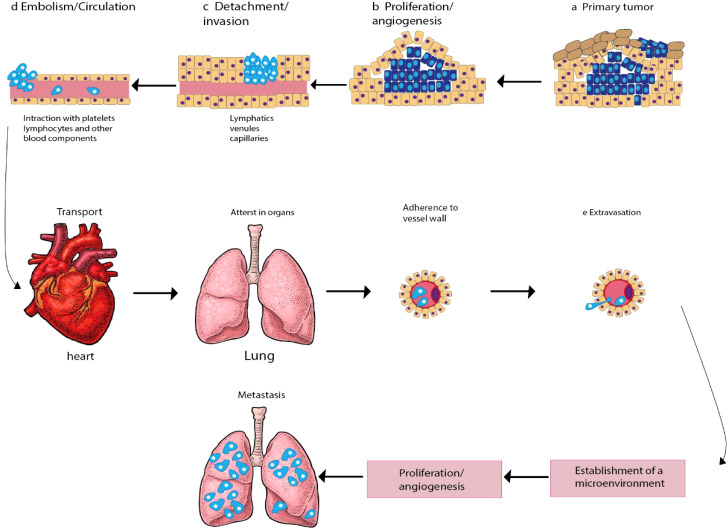

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram depicting the main steps in the formation of a metastasis. The progression of cancer metastasis involves a series of selective steps that are influenced by interactions between metastatic cells and homeostatic factors. Failure of a tumor cell to complete any step effectively terminates the process. Consequently, the formation of clinically relevant metastases reflects the survival and growth of distinct subpopulations of cells that already exist within primary tumors. (A) The process begins with cellular transformation and tumor growth. (B) Extensive vascularization should occur if the tumor size increases. This is achieved through the synthesis and secretion of angiogenic factors, which establish a capillary network from the surrounding host tissue. (C) Some tumor cells migrate and invade the host stroma via several parallel mechanisms. Lymphatic channels offer little resistance to penetration by tumor cells and are the most common route for tumor cell entry into the circulation. (D) Subsequently, detachment and embolization of single tumor cells or aggregates occur; most circulating tumor cells are quickly destroyed. Once cancer cells survive in the circulation, they become trapped in the capillary beds of distant organs by adhering to either capillary endothelial cells or the subendothelial basement membrane. (E) Extravasation then occurs, likely through mechanisms similar to those during invasion. Proliferation within the organ parenchyma completes the metastatic process. To continue growing, the micrometastasis must develop a vascular network and evade destruction by host defenses. The cells can then invade blood vessels, enter the circulation, and create new metastases.