Abstract

Background and Objectives

People with Parkinson disease (PWP) and their care partners have high palliative care needs resulting from disabling motor and nonmotor symptoms. There is growing support for palliative care (PC) approaches to Parkinson disease. However, little is known regarding the extent to which the palliative needs of PWP and care partners are currently being met. This study's primary objective is to describe PWP's and care partners' perceptions of the extent to which their PC needs are being met. Secondary objectives are to describe their perceptions of the quality of clinical communication and their knowledge of PC.

Methods

PWPs and care partners (n = 12,995) who had consented to receiving surveys from the Parkinson's Foundation were emailed an electronic survey. PC was operationalized as comprising 5 key components: systematic assessment and management of (1) nonmotor symptoms, (2) PWPs' emotional and spiritual needs, (3) care partners' needs, (4) the completion of annual advance care planning, and (5) timely referrals to specialist palliative care and hospice when appropriate.

Results

A total 1,882 individuals (1,266 PWP and 616 care partners) responded to the survey (response rate 14.5%). Few PWP (22%) reported that their neurologists never asked regarding bothersome nonmotor symptoms or did so or only if they brought it up. Fifty percent of PWP reported that pain as a specific nonmotor symptom was never managed or managed only if they brought it up. Similarly, PWPs' emotional and spiritual needs (55%), care partners' well-being (57%), and completion of advance care planning documentation (79%) were never addressed or only addressed if PWP brought it up. The quality of clinical communication was generally rated as open and honest (64% PWP). Fewer PWP (30%) reported that doctors helped them deal with the uncertainties of Parkinson disease. Most PWP (85%) reported being knowledgeable regarding PC, and 68% reported that the goal of PC was to help friends and family cope with the illness.

Discussion

Although some elements of PC are currently being addressed in routine care for PWP, there are many gaps and opportunities for improvement. These data may facilitate focused attention and development of resources to improve the quality and availability of PC for Parkinson disease.

Introduction

People with Parkinson disease (PWP) and their family care partners have significant palliative care (PC) needs arising from multiple progressively disabling symptoms such as pain, depression, and fatigue,1 as well as spiritual and existential struggles, grief, and demoralization.2 Given the high prevalence of care partner stress, underrecognition and undertreatment of complex nonmotor symptoms,3 and high rates of death in hospitals,4 a PC approach is appropriate at all stages of the disease.

PC is defined as an approach to medical care that goes beyond diagnosis and treatment of the underlying disease to address complex symptomatology, psychosocial, and spiritual needs of people living with life-altering illness and of their families, and defining personalized goals of treatment.5,6 Although sometimes believed to be appropriate only at the end of life and cancer, PC is an emerging area of interest in the clinical care of PWP with guidelines and clinical trials supporting a PC approach for PWP even from the early stages of the disease5,7,8 and suggesting roles for neurologists, allied professionals, and palliative and neuropalliative specialists in providing this care.9,10 There is a growing call to action for neurologists to incorporate a palliative approach into routine care for Parkinson disease (PD).11 Movement disorder specialists increasingly appreciate the role for PC in the management of PD and desire more PC skills and education relevant to PD.12,13 PWP and families also support integrating PC approaches across all stages of PD,14 especially because it relates to advance care planning where they express a need for a “roadmap” of the disease course to guide future planning.15 Last, professional and disease societies are placing the components of PC such as advance care planning into their guidelines and quality metrics. Advance care planning is a key component of a PC approach and is now recognized as a key quality metric by the American Academy of Neurology.5,16

On the basis of the above considerations, a large project was initiated to integrate PC as a part of routine care offered at the Parkinson's Foundation's Centers of Excellence (COE) in the United States. However, PWP and care partners' perceptions of the extent to which their PC needs are currently met is unknown. The primary objective of this study is to describe PWPs' and family care partners' perceptions on the extent to which their PC needs are met with the goals of targeting implementation efforts and setting a baseline standard for future comparisons. The secondary objectives are to describe (1) PWP and family care partners' perceptions of the effectiveness of communications with medical providers, (2) PWP and family care partners' personal knowledge of PC, and (3) the differences in PC reach between persons receiving care through a COE vs care received from a non-COE practice.

Methods

The study was part of a larger project (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Dissemination and Implementation Award # DI-2019C2-17499) aimed at implementing team-based outpatient palliative care across 33 Parkinson's Foundation-affiliated Centers of Excellence in the United States. To be designated as a Parkinson's Foundation COE, institutions are required to meet standards of rigorous research, comprehensive care delivery, professional education, and patient outreach service criteria and undergo a selective peer-review evaluation.

To help guide implementation efforts and provide a baseline measure of reach, a cross-sectional survey was distributed to PWP and care partners (both within and outside of the COE network in the United States) who had provided consent to receiving surveys from the Parkinson's Foundation. PC was operationalized as comprising 5 key components: (1) management of nonmotor symptoms, (2) support for PWPs' emotional and spiritual needs, (3) recognition and support of care partners' needs, (4) the completion of annual advance care planning, and (5) timely referrals to specialist palliative care and hospice when appropriate.

Survey Design

The survey comprised questions pertaining to respondents' (1) perceptions on the extent to which the 5 components of PC were provided, (2) satisfaction with communication with providers, and (3) knowledge of PC. Because no validated scale existed to directly measure the 5 components of PC, the research team generated survey items to evaluate these. For items related to the first 4 components of PC (systematic assessment and management of (1) nonmotor symptoms, (2) PWPs' emotional and spiritual needs, (3) care partners' needs, and (4) annual advance care planning), respondents were required to choose one of the 6 options (never, rarely, only if I bring it up, at every visit, does not apply to me, and I do not know). Because our goal for the project was systematic assessment, we chose the options of “only if I bring it up,” “rarely,” or “never” as our mark of suboptimal care. For statements related to the fifth and final component, namely, timely referrals to specialist palliative care (PC clinic or in-home PC), and hospice, there were 3 available responses: “yes/no/I do not know.” The parent study's patient and care partner advisory council reviewed the survey, and their suggestions were incorporated. Questions related to their satisfaction with the effectiveness of communication with their providers were adapted from the Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer measure.17 To assess the knowledge of PC, we adapted questions from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS).18

Data Collection

Surveys were distributed through the Parkinson's Foundation to persons with Parkinson disease (PWP) and care partners who had consented to participating in their surveys. Potential study participants (n = 12,995) included those receiving care at a COE and those receiving care outside of the COE network (non-COE). An electronic survey was sent via email to potential participants between September 9, 2021, to January 20, 2022.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The authors confirm that survey participants' consent was not required for this work and hence was not obtained. The Advarra Institutional Review Board (IRB) provided the Parkinson's Foundation approval for the distribution of the surveys that was regulated under an existing protocol. The parent study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board (RSRB Study 00005799).

Statistical Analysis

The results are reported as means (standard deviation) for continuous measures (e.g., age) and percent responding to each survey item, separately for PWP and care partners. Comparisons between those identifying as currently receiving care at a COE or at a non-COE were made using T-tests for continuous measures and Chi-square tests for categorical survey items with p-values <0.05 being considered statistically significant. The assessment of differences in knowledge between those receiving care at a COE or at a non-COE were also adjusted for the education level. These results were unappreciatively different from the unadjusted results and are not reported. The results are based on actual responses, and instances of missing values were excluded. To report more clearly on perceptions of PWP and care partners regarding the receipt of the first 4 PC components (systematic assessment and management of nonmotor symptoms, patient emotional and spiritual needs, care partner needs, and completion of annual advance care planning), the responses of “does not apply to me” and “I do not know” were excluded from the analyses of data related to these components.

Data Availability

Individual respondent level data will not be shared because although identifying information were not gathered, it may be possible to identify respondents based on data related to demographics and geographical location. Aggregated data are provided in the manuscript and can be shared upon request.

Results

Of the 12,995 surveys sent, a total of 1,882 participants (1,266 PWP and 616 care partners) completed it, with a response rate of 14.5%. Although PWP and care partner respondents were not required to be related to each other or to be from the same household, it is possible that some PWP and care partner respondents may have been from the same household. Among PWP, 357 (28%) received care at a COE, 835 (66%) received care at non-COE, and 74 (6%) reported they did not know if they received care at or outside a COE. Of the 616 care partner respondents, 169 (27%) reported that their PWP received care at a COE, and 428 (70%) at a non-COE (Table 1). The mean (standard deviation) age for PWP was 71.4 (7.9) and for care partners was 70.1 (8.5) and 60% of the PWP and 84% care partners were women. Many PWP respondents had been diagnosed with PD < 10 years ago (79% PWP and 65% care partners).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patient and Care Partner Respondents

| PWP (n = 1266) | PWP at COE (n = 357) | PWP at non-COE (n = 835) | p Value | Care partners (n = 616) | Care partners at COE (n = 169) | Care partners at non-COE (n = 428) | p Value | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) PWP = 1262 and care partner = 615 | 71.4 (7.9) | 70.1 (7.9) | 71.9 (7.8) | <0.001 | 70.1 (8.5) | 70.4 (8.0) | 69.8 (8.6) | 0.42 |

| Years with PD for person with PD/for person with Parkinson that you support, n (%) PD = 1255 | 0.27 | 0.04 | ||||||

| <5 y | 610 (48.6) | 163 (45.7) | 423 (50.7) | 207 (33.6) | 47 (27.8) | 154 (36.0) | ||

| 5–9 y | 386 (30.8) | 116 (32.5) | 253 (30.3) | 191 (31.0) | 50 (29.6) | 136 (31.8) | ||

| ≥10 y | 259 (20.6) | 78 (21.8) | 159 (19.0) | 218 (35.4) | 72 (42.6) | 138 (32.2) | ||

| Sex, n (%) PWP = 1264 and care partner = 614 | 0.54 | 0.35 | ||||||

| Female | 752 (59.5) | 213 (59.7) | 497 (59.5) | 515 (83.9) | 136 (80.5) | 365 (85.3) | ||

| Male | 507 (40.1) | 144 (40.3) | 333 (39.9) | 97 (15.8) | 33 (19.5) | 61 (14.3) | ||

| Nonbinary | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Race, n (%) | 0.93 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Caucasian/White | 1176 (92.9) | 334 (93.6) | 780 (93.4) | 570 (92.5) | 164 (97.0) | 390 (91.1) | ||

| Non-Caucasian/White | 90 (7.1) | 23 (6.4) | 55 (6.6) | 46 (7.5) | 5 (3.0) | 38 (8.9) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) PWP = 1261 and care partner = 614 | 0.63 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 31 (2.5) | 7 (2.0) | 22 (2.6) | 15 (2.4) | 5 (3.0) | 10 (2.3) | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 901 (71.5) | 266 (74.5) | 600 (71.9) | 458 (74.6) | 122 (72.2) | 321 (75.0) | ||

| Other | 183 (14.5) | 51 (14.3) | 115 (13.8) | 80 (13.0) | 20 (11.8) | 60 (14.0) | ||

| Unknown | 66 (5.2) | 17 (4.8) | 44 (5.3) | 25 (4.1) | 9 (5.3) | 16 (3.7) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 80 (6.3) | 16 (4.5) | 54 (6.5) | 36 (5.9) | 13 (7.7) | 21 (4.9) | ||

| Education, n (%) PWP = 1258 and care partner = 612 | <0.001 | 0.05 | ||||||

| ≥Bachelor's degree | 927 (73.7) | 290 (81.7) | 591 (71.0) | 434 (70.9) | 129 (76.8) | 292 (68.5) | ||

| <Bachelor's degree | 331 (26.3) | 65 (18.3) | 241 (29.0) | 178 (29.1) | 39 (23.2) | 134 (31.5) | ||

| Income, n (%) PWP = 893 and care partner = 411 | 0.004 | 0.34 | ||||||

| $50,000 or more | 667 (74.7) | 215 (81.4) | 424 (72.2) | 334 (81.3) | 99 (83.9) | 225 (79.8) | ||

| Less than $50,000 | 226 (25.3) | 49 (18.6) | 163 (27.8) | 77 (18.7) | 19 (16.1) | 57 (20.2) |

Survey Findings on the Extent of Receipt of Key Components of PC

Survey results on the key components of PC are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Respondents' Perception of Receipt of Nonmotor and Psychosocial Components of Palliative Care

| PWP (n = 1266) | PWP at COE (n = 357) | PWP at non- COE (n = 835) | p Value | Care partners (n = 616) | Care partners at COE (n = 169) | Care partners at non- COE (n = 428) | p Value | |

| Systematic management of nonmotor symptoms | ||||||||

| How often does Parkinson doctor ask about most bothersome nonmovement symptoms, n (%) PWP = 1119 and care partner = 546 | 0.001 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Never | 48 (4.3) | 9 (2.6) | 38 (5.0) | 14 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (3.4) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 200 (17.9) | 53 (15.6) | 144 (18.9) | 94 (17.2) | 22 (14.1) | 72 (18.6) | ||

| Rarely | 103 (9.2) | 18 (5.3) | 81 (10.6) | 39 (7.1) | 6 (3.9) | 32 (8.3) | ||

| At every visit | 769 (68.6) | 260 (76.5) | 500 (65.5) | 399 (73.1) | 128 (82.0) | 269 (69.7) | ||

| How often does Parkinson doctor provide treatment or support for nonmovement symptoms, n (%) PWP = 1078 and care partner = 544 | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 67 (6.2) | 12 (3.6) | 55 (7.5) | 27 (5.0) | 6 (3.9) | 19 (4.9) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 224 (20.8) | 58 (17.3) | 163 (22.4) | 119 (21.9) | 24 (15.6) | 95 (24.6) | ||

| Rarely | 149 (13.8) | 31 (9.3) | 113 (15.5) | 70 (12.9) | 11 (7.1) | 59 (15.3) | ||

| At every visit | 638 (59.2) | 234 (69.8) | 398 (54.6) | 328 (60.3) | 113 (73.4) | 213 (55.2) | ||

| How often does Parkinson doctor coordinate the treatment or support for nonmovement symptoms with primary care provider and other doctors (Example: heart doctor, diabetes doctor, etc), n (%) PWP = 869 and care partner = 468 | 0.002 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Never | 262 (30.2) | 64 (23.6) | 196 (33.6) | 111 (23.7) | 23 (18.1) | 86 (25.5) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 130 (15.0) | 34 (1.6) | 95 (16.3) | 78 (16.7) | 17 (13.4) | 61 (18.1) | ||

| Rarely | 196 (22.6) | 67 (24.7) | 123 (21.0) | 109 (23.3) | 27 (21.3) | 81 (24.0) | ||

| At every visit | 281 (32.3) | 106 (39.1) | 169 (29.0) | 170 (36.3) | 60 (47.2) | 109 (32.3) | ||

| How often does Parkinson doctor or a member of their team do the following: Manage any pain (including pain medication) may be experiencing, n (%) PWP = 746 and care partner = 377 | 0.01 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Never | 144 (19.3) | 35 (16.3) | 109 (20.9) | 70 (18.6) | 12 (12.4) | 56 (20.2) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 228 (30.6) | 54 (25.1) | 172 (33.0) | 110 (29.2) | 27 (27.8) | 82 (29.6) | ||

| Rarely | 108 (14.5) | 29 (13.5) | 76 (14.6) | 52 (13.8) | 16 (16.5) | 36 (13.0) | ||

| At every visit | 266 (35.7) | 97 (45.1) | 164 (31.5) | 145 (38.5) | 42 (43.3) | 103 (37.2) | ||

| Patient emotional and spiritual needs | ||||||||

| How often does Parkinson doctor or a member of their team do the following: Ask about any grief, guilt, sadness, or spiritual concerns, n (%) PWP = 941 and care partner = 487 | 0.07 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 342 (36.3) | 93 (32.3) | 247 (38.6) | 190 (39.0) | 36 (25.0) | 152 (44.7) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 175 (18.6) | 52 (1.1) | 120 (18.8) | 79 (16.2) | 24 (16.7) | 54 (15.9) | ||

| Rarely | 162 (17.2) | 47 (16.3) | 111 (17.3) | 99 (20.3) | 35 (24.3) | 64 (18.8) | ||

| At every visit | 262 (27.8) | 96 (33.3) | 162 (25.3) | 119 (24.4) | 49 (34.0) | 70 (20.6) | ||

| Help connect with a chaplain or counsellor for spiritual or related concerns, n (%) PWP = 726, Care partner = 407 | 0.07 | 0.20 | ||||||

| Never | 533 (73.4) | 149 (68.0) | 377 (75.7) | 297 (73.0) | 72 (65.4) | 222 (75.5) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 87 (12.0) | 30 (13.7) | 56 (11.2) | 52 (12.8) | 17 (15.5) | 35 (11.9) | ||

| Rarely | 70 (9.6) | 23 (10.5) | 46 (9.2) | 36 (8.8) | 12 (10.9) | 24 (8.2) | ||

| At every visit | 36 (5.0) | 17 (7.8) | 19 (3.8) | 22 (5.4) | 9 (8.2) | 13 (4.4) | ||

Table 3.

Respondents’ Perception of Receipt of Care Partner Support, Advance Care Planning, and Timely PC Referral Components of Palliative Care

| PWP (n = 1266) | PWP at COE (n = 357) | PWP at non- COE (n = 835) | p Value | Care partners (n = 616) | Care partners at COE (n = 169) | Care partners at non- COE (n = 428) | p Value | |

| Care partner needs | ||||||||

| How often does Parkinson doctor or a member of their team do the following: Ask care partner about the care partner's needs and well-being, n (%) PWP = 786 and care partner = 510 | <0.001 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Never | 373 (47.5) | 91 (36.8) | 279 (52.9) | 261 (51.2) | 58 (40.0) | 202 (55.6) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 76 (9.7) | 23 (9.3) | 50 (9.5) | 68 (13.3) | 24 (16.5) | 44 (12.1) | ||

| Rarely | 135 (17.2) | 47 (19.0) | 84 (15.9) | 97 (19.0) | 33 (22.8) | 63 (17.4) | ||

| At every visit | 202 (25.7) | 86 (34.8) | 114 (21.6) | 84 (16.5) | 30 (20.7) | 54 (14.9) | ||

| Provide care partners with additional support (Example: Resources or referrals to specialists such as social worker, counsellor, etc), n (%) PWP = 745 and care partner = 494 | 0.001 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Never | 393 (52.8) | 96 (41.9) | 291 (57.6) | 245 (49.6) | 61 (44.2) | 183 (51.7) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 112 (15.0) | 40 (17.5) | 70 (13.9) | 92 (18.6) | 28 (20.3) | 64 (18.1) | ||

| Rarely | 124 (16.6) | 46 (20.1) | 75 (14.8) | 87 (17.6) | 20 (14.5) | 66 (18.6) | ||

| At every visit | 116 (15.6) | 47 (20.5) | 69 (13.7) | 70 (14.2) | 29 (21.0) | 41 (11.6) | ||

| Advance care planning | ||||||||

| Talk about what future with Parkinson could look like, n (%) PWP = 1073 and care partner = 525 | 0.31 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Never | 369 (34.4) | 106 (32.0) | 259 (35.7) | 201 (38.3) | 44 (29.1) | 155 (41.8) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 250 (23.3) | 80 (24.2) | 166 (22.9) | 106 (20.2) | 36 (23.8) | 70 (18.9) | ||

| Rarely | 283 (26.4) | 83 (25.1) | 194 (26.7) | 143 (27.2) | 46 (30.5) | 96 (25.9) | ||

| At every visit | 171 (15.9) | 62 (18.7) | 107 (14.7) | 75 (14.3) | 25 (16.6) | 50 (13.5) | ||

| Talk about how to best prepare for the future with Parkinson including wishes for how to be cared for if very sick and unable to communicate, n (%) PWP = 1028 and care partner = 497 | 0.09 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Never | 601 (58.5) | 169 (53.8) | 428 (61.3) | 297 (59.8) | 75 (51.7) | 219 (62.8) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 168 (16.3) | 57 (1.1) | 105 (15.0) | 90 (18.1) | 30 (20.7) | 60 (17.2) | ||

| Rarely | 181 (17.6) | 57 (18.1) | 119 (17.1) | 84 (16.9) | 26 (17.9) | 58 (16.6) | ||

| At every visit | 78 (7.6) | 31 (9.9) | 46 (6.6) | 26 (5.2) | 14 (9.7) | 12 (3.4) | ||

| Complete advance care planning documentation (Example: Advance Directives, Living Will, Power of Attorney, or Health-care Proxy), n (%) PD = 939 and care partner = 447 | 0.16 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 601 (64.0) | 173 (60.1) | 421 (66.1) | 289 (64.6) | 64 (50.8) | 222 (69.8) | ||

| Only if I bring it up | 137 (14.6) | 51 (17.7) | 84 (13.2) | 62 (13.9) | 25 (19.8) | 37 (11.6) | ||

| Rarely | 139 (14.8) | 41 (14.2) | 94 (14.8) | 54 (12.1) | 17 (13.5) | 37 (11.6) | ||

| At every visit | 62 (6.6) | 23 (8.0) | 38 (6.0) | 42 (9.4) | 20 (15.9) | 22 (6.9) | ||

| Timely referrals to specialist palliative care and hospice | ||||||||

| Has your Parkinson doctor ever talked to you about palliative care clinic or in-home palliative care, n (%) PD = 1076 and care partner = 530 | 0.39 | 0.41 | ||||||

| Yes | 39 (3.6) | 16 (4.9) | 23 (3.1) | 42 (7.9) | 16 (10.4) | 26 (7.0) | ||

| No | 1005 (93.4) | 303 (92.1) | 687 (93.9) | 464 (87.6) | 132 (85.7) | 329 (88.4) | ||

| I do not know | 32 (3.0) | 10 (3.0) | 22 (3.0) | 24 (4.5) | 6 (3.9) | 17 (4.6) | ||

| If talked to, ever referred | 0.03 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Yes | 18 (46.2) | 11 (68.8) | 7 (30.4) | 23 (54.8) | 9 (56.3) | 14 (53.9) | ||

| No | 17 (43.6) | 5 (31.3) | 12 (52.2) | 18 (42.9) | 7 (43.8) | 11 (42.3) | ||

| I do not know | 4 (10.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (17.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.9) | ||

| Has your Parkinson doctor ever talked to you about hospice, n (%) PD = 1076 and care partner = 530 | 0.28 | 0.84 | ||||||

| Yes | 16 (1.5) | 7 (2.1) | 7 (1.0) | 12 (2.3) | 4 (2.6) | 8 (2.2) | ||

| No | 1055 (98.1) | 320 (97.3) | 722 (98.6) | 505 (95.3) | 147 (95.5) | 354 (95.2) | ||

| I do not know | 5 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 13 (2.5) | 3 (2.0) | 10 (2.7) | ||

| If talked to, ever referred | 0.47 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Yes | 5 (31.3) | 3 (42.9) | 1 (14.3) | 8 (66.7) | 3 (75.0) | 5 (62.5) | ||

| No | 9 (56.3) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (71.4) | 4 (33.3) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) | ||

| I do not know | 2 (12.5) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Assessment and Management of Nonmotor Symptoms

Few PWP (22%) and care partners (20%) reported that their PD doctor never asked regarding the most bothersome nonmotor symptoms or asked only if they brought it up. However, 27% PWP and care partners reported never receiving support for managing these symptoms or receiving support only if they brought it up (Table 2). More PWP (50%) and care partners (48%) reported that pain as a specific nonmotor symptom was either never managed or managed only if they brought it up.

Assessment and Management of PWPs' Emotional and Spiritual Needs

Over half of the respondents (55% PWP and care partners) reported that the PD doctor either never asked regarding the PWP's grief, guilt, sadness, or spiritual concerns or did so only if they brought it up (Table 2). Respondents were rarely (10% PWP and 9% care partners) connected with chaplains or counselors and some only if the PWP or care partners brought it up (12% PWP and 13% care partners).

Assessment and Management of Care Partners' Needs

Few PD doctors routinely enquired regarding the care partners' needs and well-being (PWP 26% and care partners 17%) (Table 3). More respondents reported that additional support for the care partner was either never provided or provided only if they brought it up (68% PWP and care partners).

Advance Care Planning

Most respondents (84% PWP and 86% care partners) reported that their PD doctors never, rarely, or only if they brought it up discussed what the future with PD would look like (Table 3). Approximately two-thirds of PWP (64%) and care partners (65%) reported that the PD doctor never completed any advance care planning documentation.

Timely Referrals to PC Specialist and Hospice

The results related to timely referrals to PC specialists (PC clinic or in-home PC services) and/or hospice services (Table 3) need to be viewed in the context of the fact that the study sample comprised many PWP (79% PWP respondents and 65% care partner respondents) who were diagnosed less than 10 years ago (Table 1). Thus, 4% PWP and 8% care partners reported that the PD provider discussed palliative care or in-home palliative care with them. Among those providers who had discussed palliative care, approximately half provided a referral to specialist palliative care services (PWP 46% and 55% care partners). Among the few PWP and care partners (2%) who reported having had conversations regarding hospice with the PD providers, 31% PWP and 67% care partners stated they had received a referral to hospice.

Effectiveness of Communication With Doctors and Health Professionals

Approximately two-thirds of PWP and care partners (69%) reported that their PD doctors and other health care professionals made them feel comfortable regarding asking questions (Table 4). The quality of communication with doctors and health care professionals was rated as being open and honest communications (64% PWP and 59% care partners), and approximately half of the respondents (48% PWP and 57% care partners) reported that their team ensured they understood the steps in the care of PD. However, fewer PWP (25%) and care partners (22%) felt that their doctors did very well or an outstanding job talking to them regarding how to cope with fears, stress, and other feelings or in helping them dealing with the uncertainties of PD (30% PWP and 26% care partners).

Table 4.

Respondents' Perceptions of the Effectiveness of Communication With Doctors and Health Professionals

| PWP (n = 1266) | PWP at COE (n = 357) | PWP non-COE (n = 835) | p Value | Care partner (n = 616) | Care partner at COE (n = 169) | Care partner at non-COE (n = 428) | p Value | |

| Communication effectiveness | ||||||||

| How much do doctors and other health professionals make you feel comfortable asking questions, n (%) PWP = 1052 and care partner = 516 | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Not at all | 20 (1.9) | 7 (2.2) | 10 (1.4) | 10 (1.9) | 3 (2.0) | 7 (1.9) | ||

| Not very much | 58 (5.5) | 9 (2.8) | 48 (6.7) | 21 (4.1) | 1 (0.7) | 19 (5.2) | ||

| Somewhat | 254 (24.1) | 62 (19.3) | 192 (26.9) | 129 (25.0) | 22 (14.8) | 107 (29.4) | ||

| A lot | 371 (35.3) | 120 (37.3) | 246 (34.4) | 171 (33.1) | 55 (36.9) | 114 (31.3) | ||

| A great deal | 349 (33.2) | 124 (38.5) | 219 (30.6) | 185 (35.9) | 68 (45.6) | 117 (32.1) | ||

| How often do doctors and other health professionals have open and honest communication, n (%) PWP = 1051 and care partner = 516 | <0.001 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Never | 13 (1.2) | 4 (1.3) | 9 (1.3) | 17 (3.3) | 4 (2.7) | 12 (3.3) | ||

| Rarely | 87 (8.3) | 9 (2.8) | 76 (10.6) | 69 (13.4) | 10 (6.7) | 58 (15.9) | ||

| Sometimes | 281 (26.7) | 76 (23.7) | 202 (28.3) | 126 (24.4) | 33 (22.2) | 93 (25.6) | ||

| Often | 346 (32.9) | 110 (34.3) | 234 (32.7) | 170 (33.0) | 50 (33.6) | 119 (32.7) | ||

| Always | 324 (30.8) | 122 (38.0) | 194 (27.1) | 134 (26.0) | 52 (34.9) | 82 (22.5) | ||

| How much do doctors and other health professionals give information and resources to help make decisions, n (%) PWP = 1051 and care partners = 516 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Not at all | 58 (5.5) | 9 (2.8) | 48 (6.7) | 27 (5.2) | 3 (2.0) | 24 (6.6) | ||

| Not very much | 183 (17.4) | 38 (11.8) | 145 (20.3) | 109 (21.1) | 18 (12.1) | 90 (24.7) | ||

| Somewhat | 321 (30.5) | 87 (27.0) | 228 (31.9) | 198 (38.4) | 55 (36.9) | 143 (39.3) | ||

| A lot | 326 (31.0) | 117 (36.3) | 204 (28.6) | 122 (23.6) | 50 (33.6) | 70 (19.2) | ||

| A great deal | 163 (15.5) | 89 (12.5) | 89 (12.5) | 60 (11.6) | 23 (15.4) | 37 (10.2) | ||

| How well do doctors and other health professionals talk about how to cope with any fears, stress, and other feelings, n (%) PWP = 1052 and care partner = 516 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Poorly | 83 (7.9) | 18 (5.6) | 65 (9.1) | 62 (12.0) | 5 (3.4) | 56 (15.4) | ||

| Not very well | 315 (29.9) | 77 (23.9) | 232 (32.5) | 170 (33.0) | 47 (31.5) | 123 (33.8) | ||

| Fairly well | 298 (28.3) | 95 (29.5) | 197 (27.6) | 129 (25.0) | 38 (25.5) | 90 (24.7) | ||

| Very well | 206 (19.6) | 79 (24.5) | 127 (17.8) | 84 (16.3) | 29 (19.5) | 54 (14.8) | ||

| Outstanding | 54 (5.1) | 25 (7.8) | 28 (3.9) | 30 (5.8) | 15 (10.1) | 15 (4.1) | ||

| Does not apply | 96 (9.1) | 18 (5.6) | 65 (9.1) | 41 (8.0) | 5 (3.4) | 56 (15.4) | ||

| How often do doctors and other health professionals make sure the steps in care are understood, n (%) PWP = 1051 and care partner = 516 | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 79 (7.5) | 13 (4.0) | 64 (9.0) | 32 (6.2) | 7 (4.7) | 24 (6.6) | ||

| Rarely | 168 (16.0) | 39 (12.1) | 127 (17.8) | 56 (10.9) | 6 (4) | 50 (13.7) | ||

| Sometimes | 303 (28.8) | 89 (27.6) | 211 (29.6) | 136 (26.4) | 28 (18.8) | 107 (29.4) | ||

| Often | 316 (30.1) | 111 (34.5) | 199 (27.9) | 155 (30.0) | 52 (34.9) | 102 (28.0) | ||

| Always | 185 (17.6) | 70 (21.7) | 113 (15.8) | 137 (26.6) | 56 (37.6) | 81 (22.3) | ||

| How well do doctors and other health professionals help deal with the uncertainties about Parkinson's disease, n (%) PWP = 1052 and care partner = 516 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Poorly | 74 (7.0) | 12 (3.7) | 61 (8.5) | 41 (8.0) | 6 (4.0) | 34 (9.3) | ||

| Not very well | 270 (25.7) | 65 (20.2) | 201 (28.1) | 142 (27.5) | 28 (18.8) | 113 (31.0) | ||

| Fairly well | 316 (30.0) | 102 (31.7) | 208 (29.1) | 172 (33.3) | 53 (35.6) | 118 (32.4) | ||

| Very well | 245 (23.3) | 90 (28.0) | 151 (21.1) | 94 (18.2) | 35 (23.5) | 59 (16.2) | ||

| Outstanding | 65 (6.2) | 31 (9.6) | 34 (4.8) | 40 (7.8) | 21 (14.1) | 19 (5.2) | ||

| Does not apply/have not been any uncertainties | 82 (7.8) | 12 (3.7) | 61 (8.5) | 27 (5.2) | 6 (4.0) | 21 5.8) |

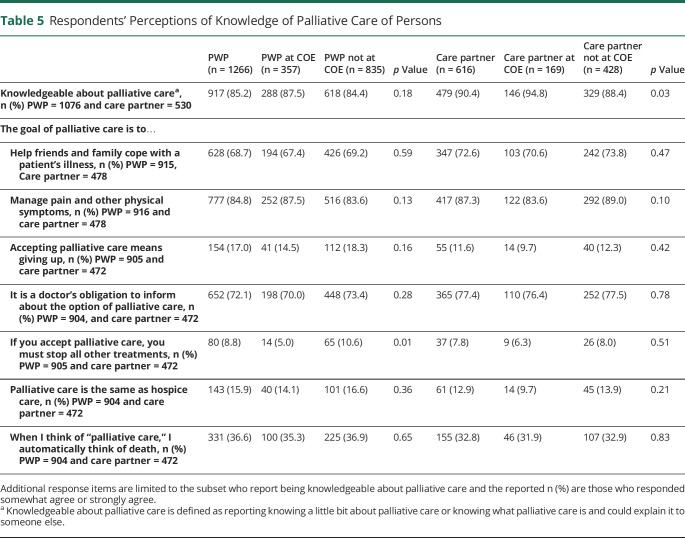

Knowledge of Palliative Care

Most PWP (85%) and care partners (90%) reported being knowledgeable regarding PC (Table 5). Many felt that the goal of PC was to help families cope with the PWP's illness (68% PWP and 73% care partners) and managing pain and other symptoms (85% PWP and 87% care partners). Approximately one-third (37% PWP and 33% care partners) reported that when they thought of PC, they automatically thought of death and few (17% PWP; 12% care partners) felt that accepting PC meant “giving up.”

Table 5.

Respondents' Perceptions of Knowledge of Palliative Care of Persons

| PWP (n = 1266) | PWP at COE (n = 357) | PWP not at COE (n = 835) | p Value | Care partner (n = 616) | Care partner at COE (n = 169) | Care partner not at COE (n = 428) | p Value | |

| Knowledgeable about palliative carea, n (%) PWP = 1076 and care partner = 530 | 917 (85.2) | 288 (87.5) | 618 (84.4) | 0.18 | 479 (90.4) | 146 (94.8) | 329 (88.4) | 0.03 |

| The goal of palliative care is to… | ||||||||

| Help friends and family cope with a patient's illness, n (%) PWP = 915, Care partner = 478 | 628 (68.7) | 194 (67.4) | 426 (69.2) | 0.59 | 347 (72.6) | 103 (70.6) | 242 (73.8) | 0.47 |

| Manage pain and other physical symptoms, n (%) PWP = 916 and care partner = 478 | 777 (84.8) | 252 (87.5) | 516 (83.6) | 0.13 | 417 (87.3) | 122 (83.6) | 292 (89.0) | 0.10 |

| Accepting palliative care means giving up, n (%) PWP = 905 and care partner = 472 | 154 (17.0) | 41 (14.5) | 112 (18.3) | 0.16 | 55 (11.6) | 14 (9.7) | 40 (12.3) | 0.42 |

| It is a doctor's obligation to inform about the option of palliative care, n (%) PWP = 904, and care partner = 472 | 652 (72.1) | 198 (70.0) | 448 (73.4) | 0.28 | 365 (77.4) | 110 (76.4) | 252 (77.5) | 0.78 |

| If you accept palliative care, you must stop all other treatments, n (%) PWP = 905 and care partner = 472 | 80 (8.8) | 14 (5.0) | 65 (10.6) | 0.01 | 37 (7.8) | 9 (6.3) | 26 (8.0) | 0.51 |

| Palliative care is the same as hospice care, n (%) PWP = 904 and care partner = 472 | 143 (15.9) | 40 (14.1) | 101 (16.6) | 0.36 | 61 (12.9) | 14 (9.7) | 45 (13.9) | 0.21 |

| When I think of “palliative care,” I automatically think of death, n (%) PWP = 904 and care partner = 472 | 331 (36.6) | 100 (35.3) | 225 (36.9) | 0.65 | 155 (32.8) | 46 (31.9) | 107 (32.9) | 0.83 |

Additional response items are limited to the subset who report being knowledgeable about palliative care and the reported n (%) are those who responded somewhat agree or strongly agree.

Knowledgeable about palliative care is defined as reporting knowing a little bit about palliative care or knowing what palliative care is and could explain it to someone else.

Comparison of the Results Between Centers of Excellence and Noncenters of Excellence

PWP receiving care at a COE had an overall higher level of formal education (more than a bachelor's degree: 82% COE and 71% non-COE) and earned a higher income (≥$50,000: 81% COE and 72% non-COE) than those receiving care at a non-COE (Table 1).

Among the key components of PC, differences between COE and non-COE were significant for the assessment and management of nonmotor symptoms and for the assessment of care partners' needs and support (Table 2). Fewer PWP (18% COE and 24% non-COE) and care partners (14% COE; 22% non-COE) at COE than those at non-COE reported that their PD doctor never asked about their most bothersome nonmotor symptom or asked only if they brought it up. Similarly, fewer PWP receiving care at COE (21%) than at a non-COE (30%) reported that their PD doctor never provided treatment or support for nonmotor symptoms or did so only if they brought it up.

Communication with providers was also perceived to be more effective by those receiving care at a COE compared with those receiving care at a non-COE with the difference between COE and non-COE respondents being significant for all items (Table 4). More PWP at COE (49%) than at a non-COE (41%) felt their doctors gave them information and resources that helped them a lot or a great deal to make decisions.

PWP and care partners' at both COE and non-COEs were knowledgeable about PC (Table 5). Fewer PWP at COEs (5%) than those at non-COE (11%) felt that accepting PC meant all other treatments must be stopped.

Discussion

This study shows that although PWP and care partners reported that providers asked about bothersome nonmotor symptoms, there is significant need in other areas relevant to PC, such as care partner support, psychosocial support, and advance care planning. The quality of communication from providers was good in some domains (honest and open) but less so in others (coping with uncertainty and difficult emotions). Knowledge of PC among PWP and care partners in this sample was better than that seen in other disease populations (e.g., cancer) and the general public.19,20 Last, COE did show some areas of strength compared with non-COE, although overall, the results were more similar than different with PWP and care partners at both COE and non-COE sites reporting a low to modest rate of clinicians delivering fundamental elements of a PC approach.

Symptom management is a core domain of palliative care21 and is also recognized as a vital component of primary palliative care for neurologic illness.10 Nonmotor symptoms are increasingly recognized as core features of PD that warrant routine evaluation and management, forming an integral part of standard treatment for PWP. Our survey shows that there is a relatively low proportion of patients who did not discuss nonmotor symptoms, likely because routine evaluation of these symptoms has recently been readily adopted as a component of routine care for PD. However, it is worth noting that a low proportion of survey respondents reported having discussions regarding pain as a symptom. Although pain may not be common early in the disease course, it is reported in most PWP over the course of the illness and frequently reflects an underlying neurologic cause (e.g., dystonia and neuropathic pain).22 Similarly, there are also nonneurologic causes of chronic pain (e.g., arthritis and other musculoskeletal pain) which may not be directly because of PD. Although the management of nonneurologic types of pain may not be within the purview of neurologists, the routine assessment of pain related to PD is necessary for overall symptom management and is integral to palliative care for neurologic illness.5 Our survey suggests that PWP recognize the importance of including pain in the overall symptom management.

Although efforts to apply PC into PD care have been proposed for over 15 years,23 it is only in recent years that substantive evidence shows the role of PC for PWP24 and the effectiveness of varying approaches to PC approaches.7,25 This growing evidence has led a national and international push to integrate this approach into routine care.1,26 Our survey respondents' perception that components of a PC approach such as advance care planning discussions, psychosocial issues, and care partner support were less frequently or rarely addressed should not be surprising because the PC approach is currently not rigorously addressed in most neurology or movement training programs.27 It is possible that the lack of institutional support, adequate staff, and resources to address psychosocial issues and care partner support may be deterrents. The concept of primary palliative care as a core skillset for neurologists is also relatively new,10 and many providers still carry strong biases or misperceptions of the goals, purpose, and benefits of PC that may lead to both passive and active resistance of this approach.28 These biases include beliefs that PC relates only to alleviating disease symptoms and decreasing negative emotions although the quality of life includes positive aspects. However, a PC approach has the potential to encourage hope, joy, and love and to promote goals of care conversations around what is meaningful to patients and families.29

Effective communication between PWP, care partners, and clinicians is central to the PC approach and may be one area to target for educational and quality improvement efforts. Communication skills that are critical to the PC approach include delivering “bad news” honestly and with compassion, addressing difficult emotions, and helping people to plan for the future.10 Training in these areas improves not only patient satisfaction with communication but also improves the treatment adherence and reduces physician burnout.30 Care coordination across providers may also be seen as a communication skill and one that may be particularly important in ensuring that PC issues do not fall between the cracks of our health care systems.

Respondents were familiar with the term “palliative care,” where most correctly identified many of the core concepts. It is encouraging that in this sample respondents identified psychosocial and care partner support as core to the PC approach and saw PC as being more than end of life or hospice care. This suggests that there would be openness to both this approach and term, a finding suggested in previous smaller studies31,32 and from the writings of patient and care partner advocates.14 However, there is still room to improve and the potential for respondent bias in this sample should not be underestimated because our study participants may not be representative of the larger PD population.

To bridge the gap between recognition and adoption of a PC approach for PD, clinicians and health care systems may look to guidance for PC delivery in nonneurologic conditions.33 In 2013, the National Consensus Project published the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care which identified several domains in the creation and maintenance of high-quality PC that can serve as a framework for the implementation of PC in routine neurologic care.34,35 Domains identified by the National Consensus Project overlap with the 5 components of PC queried in our survey, including the need for effective communication, assessments of emotional and care partners' needs, and care planning. The domains also align with published recommendations from the American Academy of Neurology and the European Parkinson's Disease Association which recognize incorporation of PC and advance care planning as markers of high quality care.5,16,36 We would also like to acknowledge that these guidelines and approaches are relatively new and that it will take time for clinical practice and culture to change. Although clinician education is an important piece of this system, institutional support (or barriers) to these models of care should not be underestimated (e.g., reimbursement for time spent in advance care planning).

There are several complementary models of PC for patients with PD which may address the unmet needs identified in our study.9 The most familiar is a consultative model, in which PWP are referred to a palliative medicine specialist for complex needs (e.g., chronic pain, dealing with multiple comorbidities, and family conflicts around goals of care) or comanagement in advanced disease or for end of life/hospice care. This model is not appropriate for all PC needs because there are not enough PC specialists to see all patients with PD and, more importantly, consultative models will tend to be reactive and could add to care coordination issues.37,38 Integrated models, in which a palliative medicine specialist is embedded into a neurology practice, is an alternative way of addressing complex needs and advanced patients and may provide greater continuity of care. Although many institutions are creating such clinics, there remains a shortage of either palliative medicine specialists or neuropalliative care specialists to meet the bulk of needs.39 The last, and perhaps the most important model, is the primary (also known as generalist) PC in which the movement disorders team takes on fundamental aspects of the PC approach including annual advance care planning, nonmotor symptom management, basic psychosocial support for the patient and family, and timely referrals for specialist PC services.10 In this model, neurologists without fellowship or other specialist training in PC deliver a palliative approach in their own practice. Although this approach may hold promise for addressing gaps in care for PWP and care partners, there are currently no studies which examine the effect on patient and care partner outcomes under the primary palliative care model for neurologists and medical providers caring for PWP.

Although our study was not designed to identify barriers to implementing PC for PWP, other literature and guidance in the field provides insight.13,40 There are both educational and structural barriers which need to be addressed to ensure neurologists and clinicians are prepared to address PC needs for PWP and care partners. This will require both the integration of the PC fundamentals into postgraduate medical education and continuing medical education. We may also look toward models which bring together clinicians across disciplines in neurology, primary care, and palliative medicine. At a health care systems level, the spoke-hub-node model is one multidisciplinary approach for integrating PC into routine, neurologic care and has been studied in PC for nonneurologic illness.41 In this approach, either the PC specialist, primary care provider, or primary neurologist serves as a hub for managing communications among the health care team. This may be achieved by ancillary providers, such as social workers or nurses, who have expertise in mobilizing resources for meeting unmet needs such as those identified in our study. Although the implementation of these individual and system-wide changes may help address the needs revealed in our survey, larger changes to reimbursement practices and availability of providers and ancillary staff are also needed to ensure that primary PC can be provided by non-PC-trained clinicians.

Our study has several limitations. Generalizability of our findings is limited for several reasons. First, we surveyed PWP and care partners who had consented to receiving surveys from the Parkinson's Foundation, and hence, those surveyed may not represent all PWP and care partners with the condition. Because data were obtained from a survey, there is also the potential for response bias. In addition, our relatively low response rate could suggest that respondents were individuals who are more able or willing to complete the survey, whether because of the ease of accessibility because of disease severity, access to computers, or availability among care partners to assist with survey completion. There may be differences between COE and non-COE respondents based on factors that lead them (or allow them) to get care at tertiary COE. In addition, because many of our respondents reported higher income and education, we may not have captured the perceptions of those with lesser education or access to resources. However, if those with more access to resources are not receiving adequate PC, it can be argued that it may be even more inadequate for those with less resources. The wording of one of the survey responses presents an additional limitation. We included the phrase “at every visit” in the items related to the 5 components of PC to capture the systematic ways that providers caring for PWP attended to PC, but a response like “regularly but not at every visit” may be a better bar for care. Finally, the results of these perceptions were not verified to determine the true occurrence of the 5 components of PC and instead represent the PWP and their care partners' recollection and perception of the receipt of these services.

Although many PWP and their care partners recognize PC as important and accurately define it as emphasizing the quality of life, many PC needs are not addressed routinely in PD. PC education, institutional supports, changes to reimbursement practices, and staffing changes may be needed to adequately prepare providers for meeting the unmet palliative needs of PWP and care partners.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all those with PD and their care partners who participated in the survey. They would also like to thank Dr. Anna Naito and Nicole Yarab (Parkinson's Foundation) for their support with data collection. Finally and importantly, they would like to thank the study's Patient and Carepartner Advisory Council for their valuable input and unwavering support of this research.

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Sandhya Seshadri, PhD, MA, MS | Department of Neurology, University of Rochester, NY | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Megan Dini, MA | Parkinson’s Foundation, New York | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, and major role in the acquisition of data |

| Zachary Macchi, MD | Department of Neurology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Peggy Auinger, MS | Department of Neurology; Center for Health & Technology, University of Rochester, NY | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Sally A. Norton, PhD, RN | University of Rochester School of Nursing, NY | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, and study concept or design |

| Jodi S. Holtrop, PhD, MCHES | Department of Family Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Medical Campus | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, and study concept or design |

| Benzi M. Kluger, MD, MS | Department of Neurology, University of Rochester, NY | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

This project was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®) [Dissemination and Implementation Award # DI-2019C2-17499]. The views, statements, and opinions in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Disclosure

B. M. Kluger received funding related to this work from the National Institute of Aging (K02AG062). All other authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Kluger BM, Dolhun R, Sumrall M, Hall K, Okun MS. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: time to move beyond cancer. Mov Disord. 2021;36(6):1325-1329. doi: 10.1002/mds.28556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hermanns M, Deal B, Haas B. Biopsychosocial and spiritual aspects of Parkinson disease: an integrative review. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(4):194-205. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3182527593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shulman LM, Taback RL, Rabinstein AA, Weiner WJ. Non-recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8(3):193-197. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00015-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sleeman KE, Ho YK, Verne J, et al. Place of death, and its relation with underlying cause of death, in Parkinson's disease, motor neurone disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):840-846. doi: 10.1177/0269216313490436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor LP, Besbris JM, Graf WD, Rubin MA, Cruz-Flores S, Epstein LG. Clinical guidance in neuropalliative care: an AAN position statement. Neurology. 2022;98(10):409-416. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000200063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care—creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173-1175. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1215620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kluger BM, Miyasaki J, Katz M, et al. Comparison of Integrated outpatient palliative care with standard care in patients with Parkinson disease and related disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):551-560. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onarheim KJ, Lindvall S, Graham L. The European Parkinson's disease standards of care consensus statement. Mov Disord. 2014;29:S169. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarolli CG, Holloway RG. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: outpatient needs and models of care over the disease trajectory. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(S1):S44-S51. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.11.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creutzfeldt CJ, Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Neurologists as primary palliative care providers: communication and practice approaches. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(1):40-48. doi: 10.1212/cpj.0000000000000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holloway RG, Kramer NM. Advancing the neuropalliative care approach-a call to action. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(1):7-8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyasaki JM, Lim SY, Chaudhuri KR, et al. Access and attitudes toward palliative care among movement disorders clinicians. Mov Disord. 2022;37(1):182-189. doi: 10.1002/mds.28773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lennaerts H, Groot M, Steppe M, et al. Palliative care for patients with Parkinson's disease: study protocol for a mixed methods study. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0248-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall K, Sumrall M, Thelen G, Kluger BM. Palliative care for Parkinson's disease: suggestions from a council of patient and carepartners. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2017;3(1):16. doi: 10.1038/s41531-017-0016-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan SR, Kluger B, Ayele R, et al. Optimizing future planning in Parkinson disease: suggestions for a comprehensive roadmap from patients and care partners. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(S1):S63-S74. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.09.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Factor SA, Bennett A, Hohler AD, Wang D, Miyasaki JM. Quality improvement in neurology: Parkinson disease update quality measurement set: executive summary. Neurology. 2016;86(24):2278-2283. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International R. Patient centered communication in cancer care:6-item instrument (PCC-Ca-6) [online]. Accessed May 8, 2021. rti.org/impact/patient-centered-communication-cancer-care-instrument.

- 18.Institute NC. Health information: national trends survey. Cycle 2, 2018 [online]. hints.cancer.gov/data/survey-instruments.aspx#H5C2

- 19.Chosich B, Burgess M, Earnest A, et al. Cancer patients' perceptions of palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(3):1207-1214. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04917-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins A, McLachlan SA, Philip J. Initial perceptions of palliative care: an exploratory qualitative study of patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Palliat Med. 2017;31(9):825-832. doi: 10.1177/0269216317696420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: the World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2002;24(2):91-96. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00440-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha AD, Jankovic J. Pain in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27(4):485-491. doi: 10.1002/mds.23959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudson PL, Toye C, Kristjanson LJ. Would people with Parkinson's disease benefit from palliative care? Palliat Med. 2006;20(2):87-94. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1108oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kluger BM, Shattuck J, Berk J, et al. Defining palliative care needs in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2019;6(2):125-131. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veronese S, Gallo G, Valle A, et al. Specialist palliative care improves the quality of life in advanced neurodegenerative disorders: NE-PAL, a pilot randomised controlled study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(2):164-172. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kluger BM, Fox S, Timmons S, et al. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: meeting summary and recommendations for clinical research. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;37:19-26. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta AK, Najjar S, May N, Shah B, Blackhall L. A needs assessment of palliative care education among the United States Adult Neurology Residency Programs. J Palliat Med 2018;21(10):1448-1457. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, et al. Not the 'grim reaper service': an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(1):e000544. doi: 10.1161/jaha.113.000544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kluger BM, Garvan CW, Holloway RG. Joy, suffering, and the goals of medicine. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(3):265-266. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755-761. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3597-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boersma I, Jones J, Carter J, et al. Parkinson disease patients' perspectives on palliative care needs: what are they telling us? Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6(3):209-219. doi: 10.1212/cpj.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boersma I, Jones J, Coughlan C, et al. Palliative care and Parkinson's disease: caregiver perspectives. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(9):930-938. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(11):e588–e653. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30415-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson EW, Frazer MS, Schellinger SE. Expanding the palliative care domains to meet the needs of a community-based supportive care model. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(2):258-265. doi: 10.1177/1049909117705061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. Kans Nurse. 2004;79(9):16-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Parkinson Disease Association. The European Parkinson's disease standards of care consensus statement [online]. Accessed November 13, 2020. epda.eu.com/media/1181/epda-consensus-statement-en.pdf.

- 37.Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, Salsberg ES. The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(4):1216-1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramanathan U, Tanuseputro P. Improving access to palliative care for persons with Parkinson disease. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(2):149-151. doi: 10.21037/apm.2019.11.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson MT, Barrett KM. Emerging subspecialties in neurology: neuropalliative care. Neurology. 2014;82(21):e180-e182. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000000453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waldron M, Kernohan WG, Hasson F, Foster S, Cochrane B, Payne C. Allied health professional's views on palliative care for people with advanced Parkinson's disease. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2011;18(1):48-57. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2011.18.1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huitema AA, Harkness K, Heckman GA, McKelvie RS. The spoke-hub-and-node model of integrated heart failure care. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(7):863-870. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Individual respondent level data will not be shared because although identifying information were not gathered, it may be possible to identify respondents based on data related to demographics and geographical location. Aggregated data are provided in the manuscript and can be shared upon request.