Graphical abstract

Keywords: Tinplate scraps, Sn extraction, Selective leaching, Ultrasound-assisted, Acoustoelectric synergy

Highlights

-

•

Thermodynamic and parameters for selective alkaline leaching of Sn are studied.

-

•

Ultrasound can observably facilitate the alkaline leaching of Sn from tinplate scraps.

-

•

Microstructure, kinetics and electrochemistry differences in leaching are investigated.

-

•

Novel acoustoelectric synergy is applied to clarify tin intensifying dissolution mechanism.

Abstract

Clean and fast extraction of tin from the surface of tinplate scraps is of great significance for the efficient utilization of waste resources. However, the dense tin layer causes the low efficiency of conventional leaching process. To improve Sn leaching efficiency, the ultrasound technique was adopted to extract Sn from tinplate scraps by alkaline leaching in this study. In the NaOH-H2O2 leaching system, metallic tin and alloyed tin in Fe-Sn alloy located on the surface of tinplate scraps can be oxidized and transferred to soluble Na2SnO3, while the iron in Fe-Sn alloy was oxidized to oxides which were chemically inert in alkaline solution. The differences in chemical solubility of Sn and Fe, and solubleness of stannate and iron oxides gave rise to the selective separation of Sn from the tinplate scraps. The effects of the leaching parameters on the Sn leaching behaviors in conventional and ultrasound-assisted leaching processes were compared. The conventional leaching temperature and time were significantly reduced during the ultrasound-assisted leaching process. Almost all of Sn can be extracted after conventional leaching at 1 mol/L NaOH, temperature of 80 ℃ and time of 60 min, however the same Sn leaching effect can be achieved by ultrasound-assisted leaching at 60 ℃ for 30 min with ultrasound power of 60% (360 W). Sn leaching kinetics based on the plate model demonstrated the reaction rate constant of the ultrasound-assisted leaching was 70% higher than that of the conventional leaching. A novel acoustoelectric synergy effect underlying intensifying mechanism by ultrasound irradiation was proposed in this study. Eventually, this work provided a rapid and clean tin extraction method from tinplate scraps via the ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching treatment.

1. Introduction

Tinplate is commercial cold-rolled sheet steel coated with 0.5–2.0 wt% tin. Due to the excellent corrosion resistance, non-toxic, high strength, and good ductility characteristics, tinplate packaging containers are well received by general consumers, and widely used in food packaging, pharmaceutical packaging, daily necessities packaging, instrument packaging, and industrial packaging [1]. According to incomplete statistics, the global annual consumption of tinplate is about 15 million to 16 million tons. With the rapid consumption of packaging supplies, a large amount of tinplate scraps is produced every year, and the valuable metals of Sn and Fe need to be recycled urgently [2]. Comprehensive utilization of tinplate scraps has dual significance for environmental protection and resource recovery.

Many attempts have been made to extract the valuable tin from the tinplate scraps. Based on the physical and chemical properties of fusibility, volatility, and solubility for tin, the commonly used methods for tin extraction from tinplate scraps include the thermal detinning [3] and hydrometallurgical leaching processes. Temperature is an important factor affecting tin volatilization since the higher the temperature, the greater the saturated vapor pressure of metallic tin. Therefore, in industrial production, thermal detinning and vacuum distillation were conducted to recover tin from tinplate scraps. Thermal detinning was reported to remove tin from tinplate scraps with 0.43 wt% Sn after fragmentation and cleaning [4]. As the tinplate was roasted at 700 ℃ for 10 min, and the tin removal efficiency was about 89 wt%. The rest tin was not volatilized due to the oxidation of Sn to hardly volatile and inert SnO2 which was partially retained in an intermediate layer. Tin can be also recovered from tin-coated copper-clad steel wire scrap via the sulfurized volatilization technology [5]. 91.26% of Sn is extracted from this wire scrap after surface sulfuration roasting in vacuum pressure of 10 Pa with FeS2/Sn molar ratio of 1.8 at 1050 °C for 240 min. Moreover, vacuum is favorable to high-temperature volatilization and can accelerate volatilization kinetics. Due to the vapor pressure difference of Pb, Sb, and Sn, vacuum distillation was applied to extract tin from Sn-Pb-Sb alloy via the orthogonal experiments under a limited vacuum degree of 5 Pa, and under conditions of distillation temperature of 1200 ℃ and time of 25 min, 99.82% of tin could be recovered [6]. It’s therefore suggested that tin recovery by thermal treatment from tin-bearing scraps has the advantage of high tin recovery efficiency, but it is characterized as high energy consumption and huge equipment investment.

Based on the probable solubility properties of tin in acid or alkaline solution, plentiful hydrometallurgical leaching treatments of tin-bearing alloys were investigated to extract tin. Mechanical stripping pretreatment followed by H2SO4-CuSO4 chemical leaching process was applied to recover tin from tin-coated copper-clad steel plate scrap via the replacement reaction between Sn and Cu(II), in which Sn was converted to Sn(II) and further oxidized to Sn(IV). The Sn(IV) can be hydrolyzed to Sn(OH)4 for the preparation of SnO2 via calcination. After that, the comprehensive recovery of Sn is 92.13% and the purity of SnO2 product is 99.21% [7]. To enhance the Sn leaching efficiency, Cl- was introduced into the H2SO4-CuSO4 leaching system to dissolve the tin from tin-coated copper-clad steel plate scrap [8]. It’s thermodynamically feasible that Cu can easily react with Cu(II) in acidic solution in the presence of Cl-, and the Cl- addition can facilitate the dissolution of Cu covered on the surface of the tin layer, thereby increasing the detinning rate to over 98.5%. The replacement dissolution of Sn by Cu(II) in H2SO4-CuSO4-Cl- leaching system was efficient for the tin extraction while further multistep purification operations would be applied to realize the separation of Sn and Cu from the acid leachate.

Alkaline leaching is also effective for tin extraction from Sn-bearing alloys. The dissolution behaviors of tin from pure tin and 50 wt% Sn-50 wt% Fe alloys in sodium hydroxide solutions were compared [9], and it’s demonstrated that the dissolution rate of tin from Sn-Fe alloy in NaOH solution was higher than that of pure tin due to the electrochemical reaction. An electrolytic detinning process was performed in a 2.5 mol/L NaOH solution to decrease the tin content in tinplate scrap [1]. It’s demonstrated that applying current can accelerate the tin dissolution, and 2.5 mol/L NaOH solution could readily dissolve the metallic tin-coating while the Sn-Fe intermetallic layer underneath was hardly leached at room temperature. It’s demonstrated that alkaline leaching has a broad application prospect for tin extraction while the dissolution of Fe-Sn alloy phase must be intensified to ensure efficient recovery of tin. On the other hand, the electrochemical corrosion of tin coating in the research field of metal corrosion can be used to clarify the tin extraction from tinplate scraps in the solution [10], [11]. In this work, the electrochemical measurement was applied to reveal the tin dissolution mechanism in alkaline environment.

As a green and efficient technology, ultrasound-assisted technology has many applications in washing, chemical reaction, and materials synthesis in aqueous system [12], [13], [14]. In hydrometallurgical leaching process, ultrasonic irradiation can increase the dissolution kinetics and metal recovery [15], [16]. In the solution system, ultrasound can produce favorable mechanical and chemical effects on the reaction medium by sound cavitation which can accelerate chemical reactions on most occasions [17], [18], [19]. According to the proven beneficial effects, ultrasound irradiation is potential technique to enhance the Sn leaching efficiency from tinplate scraps with a metallic tin-coating and underneath Sn-Fe alloy layer in this work.

Simple leaching treatment for tin recycling from tinplate scraps showing a broad application prospect [20]. How to improve the leaching efficiency is one of the elementary problems in the hydrometallurgy industry. To improve the leaching efficiency of tin, ultrasound-assisted extraction of Sn from tinplate scraps by alkaline leaching were investigated in this study. Thermodynamic basis for the selective extraction of Sn from tinplate scraps was first calculated to determine suitable conditions for selective tin leaching. After that, the effects of the leaching parameters on the Sn leaching efficiency in conventional and ultrasound-assisted leaching processes were also investigated and compared. The tin leaching kinetics, phase transformation, microstructure evolution, and electrochemical dissolution were researched, and a novel acoustoelectric synergy effect underlying intensify mechanism by ultrasound irradiation was proposed in this study. Eventually, the ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching treatment of tinplate scraps can achieve rapidly selective tin extraction.

2. Experimental

2.1. Raw materials

The tinplate scraps used in this work are obtained from a salvage station, and the Sn and Fe contents are 1.14% and 98.86%, respectively. Fig. 1 shows the main characterizations of the as-received tinplate scraps. As shown in Fig. 1(a), the XRD pattern indicates that the main phases in the scraps are Fe, Sn, and alloyed FeSn2. TG-DSC analysis of the tinplate scraps heated from 50 ℃ to 700 ℃ with a heating rate of 10 ℃/min in an air atmosphere, and the curves are displayed in Fig. 1(b). It’s found that the weight loss of tinplate scraps is in a minuscule variation before 590 ℃, and after that, the weight of tinplate scraps is increased due to the oxidation reactions of Fe, Sn, and FeSn2 since the DSC curve has an exothermic peak at 590 ℃. Fig. 1(c) shows the optical microstructure of the original tinplate scrap surface. As observed, the coated tin has a relatively smooth and dense surface. SEM-EDS analyses of the cross-section tinplate scrap are shown in Fig. 1(d) and (e). The cross-section SEM image in Fig. 1(d) shows that the tin coating thickness of tinplate scrap is approximately 150 μm. Line scanning analysis demonstrates that Fe and Sn are unevenly distributed in the tin coating. Energy disperse spectroscopy displays that the tin content in the surface layer (tin content of about 86% in Spectrum 1) is much higher than that of the inner layer (tin content of about 18% in Spectrum 2).

Fig. 1.

Characterizations of the tinplate scraps. (a) XRD patterns; (b) TG-DSC curves. (c) Optical microstructure of the tinplate scraps surface; (d) SEM-EDS analysis of the cross-section; (e) Line scanning analysis.

Alkaline leaching was conducted to extract tin from the tinplate scraps. The used leaching agent and oxidizing agent are NaOH and 30% H2O2, and they are all analytical purity obtained from Tianjin Kermel Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., China. In addition, the Sn, and Fe standard solutions for ICP testing were provided by the National Analysis and Testing Center for Non-ferrous Metals and Electronic Materials, China.

2.2. Methodology

In this work, the conventional and ultrasound-assisted leaching experiments of tinplate scraps were conducted and compared. Fig. 2 draws the schematic diagrams of the ultrasound-assisted leaching and conventional leaching processes for Sn extraction from tinplate scraps. To acquire accurate leaching results, the lumpy tinplate scraps were sheared into small square pieces with a size of 2 cm × 2 cm before leaching. For comparative study, in the ultrasound-assisted leaching procedure, mechanical agitation was not utilized while the scrap samples were only leached under ultrasonic irradiation by the ultrasonic equipment which has an adjustable power with a range of 240–600 W. On the contrary, mechanical agitation was applied to homogenize the solution in the conventional leaching.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagrams of the ultrasound-assisted leaching and conventional leaching processes for Sn extraction from tinplate scraps.

In the leaching process, the main investigated parameters were listed as follows: NaOH concentrations, H2O2 dosage, leaching temperature and time, liquid-to-solid (L/S) ratio, and ultrasound power. After leaching at a fixed temperature for a given period, the leachate was filtered to realize the separation of tin and iron. After separation, the leachate can be further condensed to obtain sodium stannate (Na2SnO3), and the original iron scrap after tin exfoliation can be compressed as an iron block for ferroalloy production. The preparation of Na2SnO3 from leachate and ferroalloy production from leaching residue were not involved in this study. The thermodynamics, kinetics, electrochemistry aspects of alkali leaching, and the characterizations of leaching residues were considered to determine the intensifying dissolution mechanism.

In this study, the leaching rate is used to express the leaching effect. After filtration, the Sn and Fe content in the leachates were measured by inductively coupled plasma (ICP-OES, Thermo Scientific iCAP PRO X, America) to calculate the Sn and Fe leaching rates. Due to uneven tinning thickness and composition in the tinplate scraps, 5 g tinplate scraps were completely dissolved in aqua regia to quantificationally test the Sn and Fe contents. All of the leaching tests were performed thrice, and the mean value of the leaching rates was used as the final result with a standard deviation in 5%. The leaching rate (x) was calculated using the following Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where m1 is the mass of Fe or Sn in the leachate, g; c is the Fe or Sn content in the leachate, g/L; V is the leachate volume, L; m2 is the mass of Fe or Sn in the original tinplate scraps, g; α is the Fe or Sn grade in the original tinplate scraps, %; m0 is the mass of the tinplate scraps used in each leaching experiment, g.

Thermogravimetric Analysis - Differential Scanning Calorimetry (TG-DSC, Netzsch STA 449F5, Germany) analysis was used to obtain values of weight and heat changes during the heating process. X-ray diffraction (XRD, RIGAKU D/Max 2500, Japan) was applied to measure the phase transformations of tinplate scrap during the alkaline leaching process. The surface microstructure and chemical composition evolutions of tinplate scraps in the conventional and ultrasound-assisted leaching processes were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Thermo Scientific/Helios G4 CX, America) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector for spot, lining and mapping scanning analyses to reveal the selective dissolution behaviors of tin. In addition, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo ESCALAB 250XI, America) was also used to detect the chemical states of Fe and Sn elements which have extremely lower content. Cyclic voltammogram (CV) curves of tinplate scraps dissolved under conventional and ultrasound-assisted conditions were recorded by an electrochemical workstation (Metrohm Autolab, PGSTAT 302 N, Swiss) to characterize the anodic peaks and cathodic peaks. Thermodynamic analyses of the Sn-H2O and Fe-H2O systems under various pH ranges were calculated by HSC Chemistry software to ascertain the suitable leaching conditions for the selective dissolution of Sn.

3. Thermodynamic basis for the selective extraction of Sn

Fig. 3 shows the E-pH diagrams of Sn-H2O and Fe-H2O systems at 25 ℃. As seen in Fig. 3(a), the main Sn-bearing species in the acid-base solutions include Sn, Sn4+, Sn2+, Sn(OH)2, Sn(OH)4, HSnO2-, and Sn(OH)62-. In general, the dissolved ionic Sn4+ and Sn2+ mainly exist in the acid environment with pH below 2.8, and the stable existence intervals for the dissolved ionic HSnO2- and Sn(OH)62- are in the alkaline environment with pH over 9.0. In addition, compared with the metallic Sn, it requires higher potentials to realize the oxidation of zero-valence tin to higher-valence ionic ions. It’s suggested that both in the acid and alkaline solutions, the tin can transfer from the tinplate scarps to solution by adjusting the oxidation potential and pH values. In order to realize the selective extraction of tin from the tinplate scraps, the Fe-bearing phases in the leaching process should be controlled as a solid state. As for the E-pH diagram of Fe-H2O system shown in Fig. 3(b), the main Fe-bearing species are Fe, Fe2+, Fe3+, Fe(OH)2, Fe3O4, Fe2O3, and FeO42-. The stable existing regions for the solid phases including Fe(OH)2, Fe3O4, and Fe2O3 are marked as light pink color in Fig. 3(b), which has weakly acidic and alkaline environments. By comprehensive consideration, the Sn should convert to HSnO2- and Sn(OH)62- while the Fe transfer to Fe(OH)2, Fe3O4, and Fe2O3 at an alkaline environment to realize the selective extraction of tin.

Fig. 3.

Eh-pH diagrams calculated at 25 ℃. (a) Sn-H2O system; (b) Fe-H2O system.

Based on the thermodynamics analysis, suitable oxidizing agents and alkali concentrations should be guaranteed to achieve a favorable tin leaching efficiency. In this study, NaOH and H2O2 were used to extract Sn, and the main chemical reaction Eq. (2) is listed as follows:

| (2) |

Sodium stannate (Na2SnO3) is water soluble, and the dissolution reaction of Na2SnO3 is described as Eq. (3).

| (3) |

On the other hand, the Fe would be oxidized to Fe(OH)2, Fe3O4, and Fe2O3 in alkaline environment based on the following Eqs. (4)-(6):

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Conventional alkaline leaching

Fig. 4 shows the effects of conventional leaching parameters, including the leaching temperature, H2O2 dosage, liquid-to-solid ratio, and leaching time on the Sn and Fe leaching rates under various NaOH concentrations.

Fig. 4.

Effect of conventional leaching parameters on the Sn and Fe leaching rate under various NaOH concentrations. (a) Effect of leaching temperature on Sn leaching, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, liquid-to-solid ratio (L/S) of 15:1, 10 min; (b) Effect of H2O2 dosage on Sn leaching, 80 °C, L/S of 15:1, 10 min; (c) Effect of leaching liquid-to-solid ratio (L/S) on Sn leaching, 80 ℃, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, 10 min; (d) Effect of time on Sn leaching, 80 ℃, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, L/S of 15:1; (e) Effect of leaching temperature on Fe leaching, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, L/S of 15:1, 10 min; (f) Effect of H2O2 dosage on Fe leaching, 80 ℃, L/S of 15:1, 10 min.

Fig. 4(a) presents the effect of temperature on the leaching rate of Sn from tinplate scraps dissolved at H2O2 dosage of 33.3% (5 mL/15 mL), liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1 (L/S of 15:1), and reaction time of 10 min. In general, the Sn leaching rate continuously increases with the increase of temperature from 25 ℃ to 80 ℃ under NaOH concentration range of 1-4 mol/L. By leaching in 4 mol/L NaOH, the Sn leaching rate is increased from 3.7% to 79.3% as the temperature is elevated from 25 ℃ to 80 ℃. It’s also found that the Sn leaching rate increases with the increment of NaOH concentration at arbitrary temperatures, especially at temperatures over 60 ℃. At 80 ℃, the Sn leaching rate is increased from 52.3% to 79.3% when the NaOH concentration is augmented from 1 mol/L to 4 mol/L. Raising temperature is favorable to the Sn extraction, however excessively high temperature will lead to the rapid decomposition of H2O2 which will aggrandize oxidant consumption [21]. In addition, high temperature also causes pressure operation and high requirements on equipment. In this work, leaching temperature range of 60–80 ℃ is recommended for the Sn extraction from tinplate scraps.

Fig. 4(b) shows the effect of H2O2 dosage on the Sn leaching rate from tinplate scraps dissolved under various NaOH concentrations with liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1 at 80 ℃ for 10 min. As observed, the Sn leaching rate is increased with the rising H2O2 dosage at all the investigated NaOH concentrations. The maximum Sn leaching rate reaches about 100% with H2O2 dosage of 33.3% (For example, 5 mL H2O2 is added into 15 mL NaOH solution). Fig. 4(c) shows the effect of liquid-to-solid ratio on the Sn leaching rate, and the other experimental conditions are fixed as follows: H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, leaching temperature of 80 ℃, and time of 10 min. The Sn leaching rate presents an upward trend at the liquid-to-solid ratio range of 3:1 to 20:1. The high liquid-to-solid ratio ensures sufficient NaOH to dissolve the tin metals. Liquid-to-solid ratio range of 15:1-20:1 is recommended for the Sn extraction. Fig. 4 (d) draws the effect of leaching time on the Sn leaching rate. It’s found that the Sn leaching rate is increased firstly and then maintains constant with the increase of leaching time. The leaching time to reach equilibrium is affected by the NaOH concentration. At 1 mol/L NaOH, the Sn leaching rate is increased from 24.24% to 97.2% as the leaching time is extended from 5 min to 60 min, while the Sn leaching rate is increased from 69.10% to 99.55% with prolonging time from 5 min to 30 min at 4 mol/L NaOH. In order to ensure the complete dissolution of tin, the suitable time in conventional leaching is 60-80 min.

Fig. 4(e) and (f) display the effects of leaching temperature and H2O2 dosage on the Fe leaching rate under various NaOH concentrations. It’s demonstrated that the Fe leaching rates in all the investigated experiments are kept at 0, indicating that the alloyed and metallic Fe cannot dissolve into NaOH-H2O2 solution. In consequence, the NaOH-H2O2 system can realize the selective dissolution of Sn, which is beneficial to the separation of Sn from the tinplate scraps. The suitable conventional leaching parameters obtained from the above-mentioned results are summarized as follows: leaching temperature of 80 ℃, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1-20:1, and leaching time of 60-80 min.

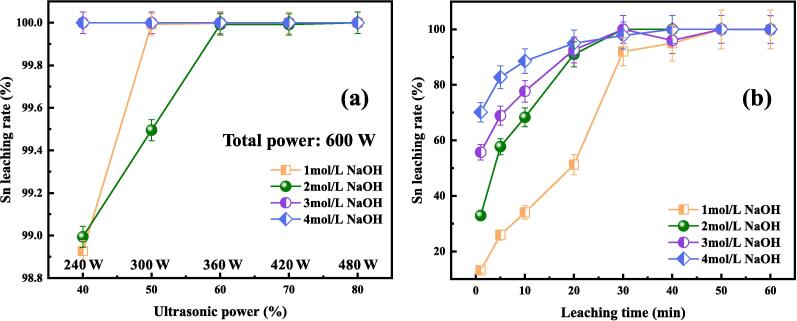

4.2. Ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching

Ultrasound irradiation was adopted to intensify the Sn extraction from tinplate scraps. Based on the conventional leaching conditions, liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, and leaching temperature of 60 ℃ were kept constant in the ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching experiments. Fig. 5 shows the effect of ultrasound power and leaching time on Sn leaching rate under different NaOH concentrations, and the corresponding leaching time is fixed as 60 min and ultrasound power is constant at 60% (total power of 600 W). As shown in Fig. 5(a), all the Sn leaching rates are over 98% with the introduction of ultrasound into the leaching system. It’s demonstrated that ultrasound irradiation can significantly enhance tin dissolution. By leaching at 3 or 4 mol/L NaOH for 60 min, the Sn leaching rates are as high as 100% even at a low ultrasound power of 40% (240 W). In the leaching solutions with lower NaOH concentrations of 1 mol/L and 2 mol/L, the ultrasound powers for the total dissolution of Sn are about 50% (300 W) and 60% (360 W), respectively. It’s suggested that the higher the concentration, the lower the ultrasound power required. As a result, ultrasound power of 60%-80% (360 W-480 W) should be provided to ensure satisfactory Sn dissolution under a wide NaOH concentration range.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ultrasonic power and leaching time on Sn leaching rate under different NaOH concentrations. (a) Effect of ultrasound power, 60 °C, temperature, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, L/S of 15:1, 60 min; (b) Effect of leaching time, 60 °C, temperature, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, L/S of 15:1, ultrasonic power of 80%.

Fig. 5(b) exhibits the Sn leaching behaviors in the ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching for various time intervals. It’s shown that the Sn leaching rates increase rapidly and then reach equilibrium with the extension of leaching time. For example, the Sn leaching rate obtained at 4 mol/L NaOH is increased from 70.1% to 97.8% with the increase of time from 1 min to 30 min, while the time reaching equilibrium for Sn leaching is about 40 min as the tinplate scraps are dissolved in 1 mol/L NaOH. Considering the thorough extraction of Sn, leaching time of 30 min is commendatory for the Sn extraction from tinplate scraps by ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching.

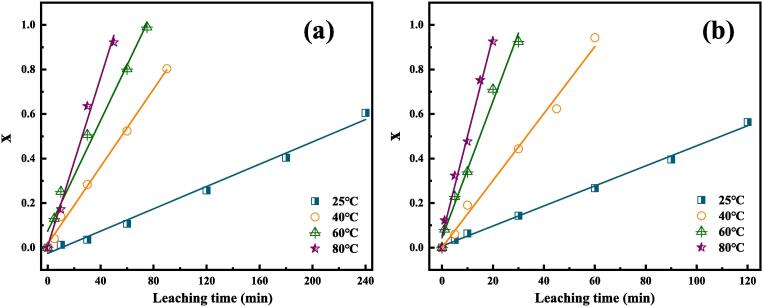

4.3. Kinetics study

Compared with conventional Sn leaching, the ultrasound-assisted leaching process presents an advantage in leaching kinetics and leaching efficiency. In this study, flaky tinplate scraps with a size of 2 cm × 2 cm were used in the leaching process. The unreacted shrinking core model is generally used to characterize the leaching kinetic mechanism for the granular material [22]. The Sn dissolution process from the surface of flaky tinplate scraps has the following features, 1) the thickness of tinplate scraps used in this study is uniform; 2) the insoluble iron matrix has good structural strength, and it is inert in the alkaline solution; 3) the solute diffusion direction is perpendicular to the particle thickness direction. These leaching conditions conform to the assumption prerequisite of the plate model. In combination with the material shape and dissolution characteristics, plate model is used to simulate the Sn leaching process, and the kinetic equation is described as the following Eq. (7):

| (7) |

where x is the Sn leaching rate, %; k is the apparent reaction rate constant, min−1; t is the leaching time, min.

The relationship between Sn leaching rate and reaction time at different temperatures in conventional leaching and ultrasound-assisted leaching processes are compared, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. To better reveal the ultrasonic strengthening mechanism, lower NaOH concentration of 1 mol/L and ultrasound power of 60% were applied in the kinetics study. The other experimental conditions for the leaching study were kept constant as follows: H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1. As observed in Fig. 6, the Sn leaching rate exhibits a linear relationship before the reaction equilibrium. After calculation of slops of the four lines in Fig. 6, the reaction rate constants and corresponding regression coefficients at various temperatures are acquired and listed in Table 1. As can be seen from Table 1, the correlation coefficients of all the fitted curves are over 0.98, indicating that the plate model can accurately forecast the leaching rate. Both in the conventional and ultrasound-assisted leaching processes, the reaction rate constants increase with the increase of temperature from 25 ℃ to 80 ℃. On the other hand, comparing the reaction rate constants at the same temperatures, the reaction rate constants acquired under ultrasound irradiation are much higher (over 70%) than those obtained under conventional leaching, verifying that the ultrasound is favorable for Sn extraction from tinplate scraps.

Fig. 6.

Relationship between Sn leaching rate and reaction time at different temperatures. (a) Conventional leaching; (b) Ultrasound-assisted leaching.

Table 1.

Values of leaching rate constant k and correlation coefficients (R2) for conventional and ultrasound-assisted leaching at different temperatures.

| Temperature (℃) | Conventional leaching |

Ultrasound-assisted leaching |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k × 10-3 (min−1) | R2 | k × 10-3 (min−1) | R2 | |

| 25 | 2.5 | 0.9905 | 4.5 | 0.9967 |

| 40 | 8.7 | 0.9952 | 15.1 | 0.9903 |

| 60 | 12.4 | 0.9835 | 30.6 | 0.9887 |

| 80 | 18.9 | 0.9901 | 44.7 | 0.9884 |

4.4. Characterization of the intermediates

Fig. 7 shows the phase transformation of the tinplate scraps during the ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching process at different times. Fig. 7(a) presents the XRD patterns of tinplate scraps after leaching at different times. It’s found that diffraction peak intensities of FeSn2 alloy phase decrease with the increase of leaching time. In particular, it's also detected by careful observation that the main diffraction peaks of FeSn2 gradually shift from 35.2° towards 34.5° with the increase of time. It’s demonstrated that the FeSn2 alloy phase is dissolved in the NaOH-H2O2 system, accompanying with the change of the crystal structure of alloy phase. On the contrary, the diffraction peak intensities of Fe increase with prolonging the leaching time, which is ascribed to the dissolution of surface Fe-Sn alloy and exposure of metallic iron matrix.

Fig. 7.

Phase transformation of the tinplate scraps during the ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching process. (a) XRD patterns; (b) Sn3d spectra of original tinplate scrap; (c) Fe2p spectra of original tinplate scrap; (d) Sn3d spectra of tinplate scrap after leaching; (e) Fe2p spectra of tinplate scrap after leaching.

Fig. 7 (b)-(e) show the XPS analysis of the tinplate scraps before and after alkaline leaching to ascertain the chemical states of Fe and Sn elements on the surface. As for the Sn3d spectrum of the original tinplate scraps (Fig. 6(b)), the characteristic peaks with binding energies of 486.78 eV (Sn3d5/2) and 495.18 eV (Sn3d3/2) are metallic tin coating on the surface of tinplate scraps. Some alloyed Sn phases also exist in original scraps with binding energies of 485.18 eV, 493.68 eV, and 496.68 eV. As for the Fe2p spectrum in Fig. 6(c), a singlet of metallic iron with binding energy of 716.28 eV is observed in the tinplate scraps. Compared with the raw material, the characteristic peak areas of metallic Sn on the surface of tinplate scraps after alkaline leaching is diminished, which is attributed to the Sn dissolution. Although the Na2SnO3 is soluble in the alkaline solution, a small quantity of Na2SnO3 with binding energy of 480.88 eV is adhere to the surface of tinplate which can be detected by the XPS. Fig. 6 (e) shows the Fe2p spectrum of tinplate after alkaline leaching. It’s discovered that the metallic Fe in the tin coating (as the form of Sn-Fe alloy) is disappeared, and some iron oxides are generated during the leaching process. The formation of insoluble iron oxides is beneficial to the separation and recovery of Sn from the tinplate scraps.

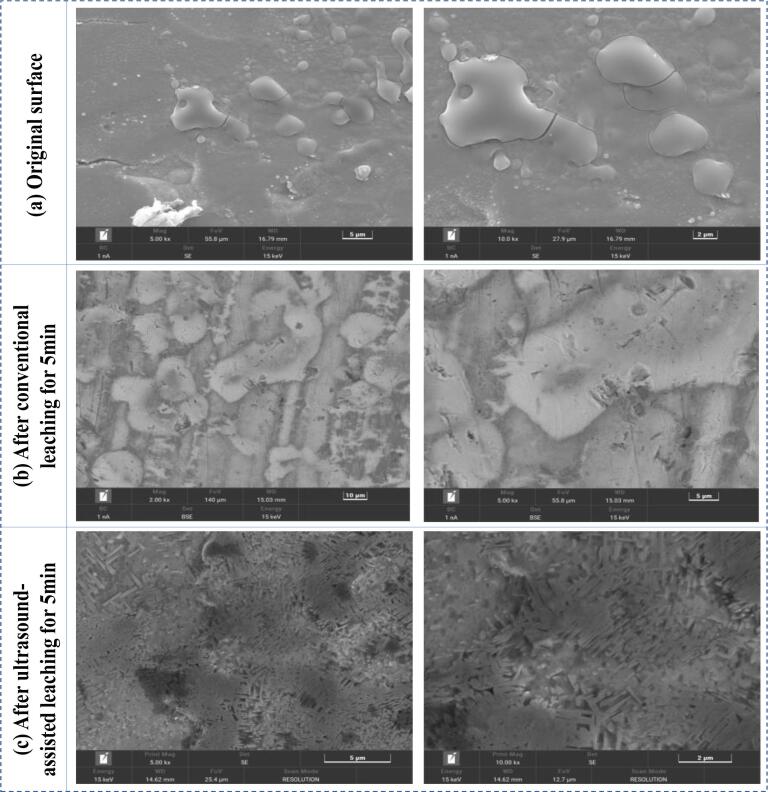

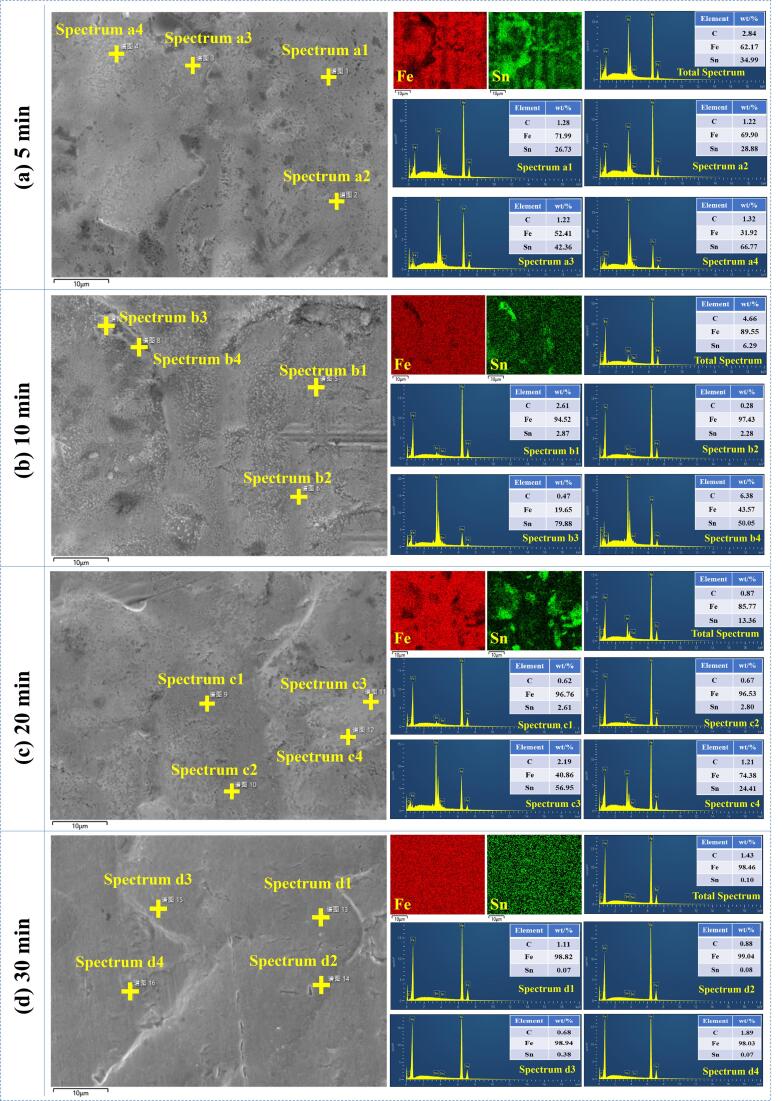

Fig. 8 shows the SEM images of the tinplate scrap surface before and after leaching for 5 min. As observed in Fig. 8(a), the original tinplate scraps have a dense surface and the tin layer has smooth grains, which are formed in the electroplating process. After conventional alkaline leaching, some tin grains are tough and damaged slightly as illustrated in Fig. 8(b), which is due to the dissolution of a small amount of tin from the surface of tinplate scraps. With the introduction of ultrasound waves into the leaching process, flocculent structure is generated on the surface of tinplate scraps, indicating the tin grains are seriously destroyed via the shear and cavitation effects of ultrasound irradiation. Compared with the surface images of conventional leaching, the Sn leaching is significantly strengthened in the ultrasound-assisted leaching process. Fig. 9 shows the SEM-EDS analyses of tinplate scraps after ultrasound-assisted leaching at various times. From the energy spectrum analyses, the tin content on the surface of the tinplate scraps gradually decreases as the sonication treatment time increases from 5 min to 30 min, and the average Sn content is only 0.1% after 30 min sonication treatment. Fe and Sn mapping images also demonstrate that some Sn are distributed unevenly on the surface of tinplate scraps, while the tin in all locations is almost dissolved completely during the ultrasound-assisted leaching for 30 min. These microscopic results are consistent with the Sn leaching rates.

Fig. 8.

SEM images of the tinplate scrap surface before and after leaching. (a) Original tinplate scrap; (b) After conventional leaching; (c) After ultrasound-assisted leaching.

Fig. 9.

SEM-EDS analyses of tinplate scraps after ultrasound-assisted leaching at various times. (a) 5 min; (b) 10 min; (c) 20 min; (d) 30 min.

4.5. Possible physical and chemical mechanism via ultrasound intensifying

Selective leaching of Sn can be realized by alkaline leaching with NaOH and H2O2 from the tinplate scraps. In the conventional leaching, the leaching rates of Sn and Fe from tinplate scraps are about 100% and 0 respectively under the leaching conditions of 1 mol/L NaOH, temperature of 80 ℃, and time of 80 min. As the ultrasound wave is introduced into the alkaline solution, Sn leaching rate of 100% can be achieved by leaching in 1 mol/L NaOH at 60 ℃ for 30 min with ultrasound power of 60%. The leaching temperature and time are significantly reduced during the ultrasound-assisted leaching process.

As reported, the main raw materials in the ultrasound-assisted leaching in the previous studies are concentrated on the sulfide ores and oxide ores. Being different from the minerals, the main phase of the tinplate scraps used in this work is Sn-Fe alloy and metallic Sn, in which the metallic bond is a chemical combination attracted by the electrostatic attraction between free electrons and metal ions. Tinplate scraps rich in free electrons have excellent electrical conductivity, and the movement of free electrons has a significant effect on the redox leaching process. The electrochemical properties of the tinplate scraps were characterized to determine the intensifying dissolution mechanism of metallic substances during the ultrasound-assisted leaching process.

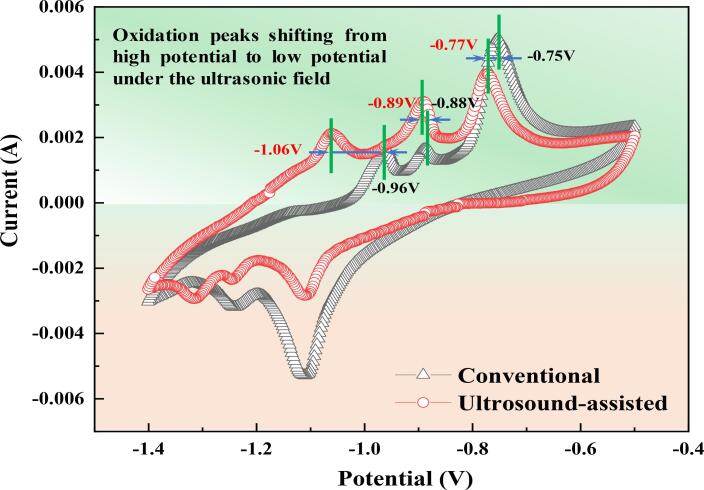

Fig. 10 shows the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the tinplate scarps dissolved in 1 mol/L NaOH solution at a scanning speed of 0.05 V/s with and without ultrasound irradiation, and the tinplate scrap is used as the anode and graphite is acted as the cathode. As shown in Fig. 10, obvious anode peaks and cathode peaks can be observed from the CV curves. At the anode peak, the current gradually increases with the increase of potential and gradually decreases after reaching the peak value, and the formation mechanism of CV anode peak is mainly related to the redox reaction on the electrode surface. As for the CV curves tested in the conventional leaching, obvious anode peaks at −0.75 V, −0.88 V, and −0.96 V are formed. However, these corresponding peaks shift to −0.77 V, −0.89 V, and −1.06 V with the introduction of ultrasound. It’s verified that oxidation peaks are shifting from high potential to low potential under the ultrasonic field, suggesting that ultrasound makes oxidation of tinplate scraps easy to happen. This reduced voltage may be due to that the acoustoelectric synergy effect of ultrasound causes electrons to move rapidly.

Fig. 10.

CV curves of tinplate scraps dissolved under conventional and ultrasound-assisted conditions.

Fig. 11 draws the schematic diagram for the rapid tin extraction from tinplate scraps via ultrasound-assisted leaching. Based on the reports in the literature and the result investigated in this study, the possible intensifying mechanism of ultrasound for fast Sn leaching includes the physical and chemical aspects.

Fig. 11.

Schematic diagram for the rapid tin extraction from tinplate scraps via ultrasound-assisted leaching. (a) Physical aspect: acoustic cavitation effect; (b) Chemical aspect: acoustoelectric and chemistry effect.

Generally speaking, the mechanical vibration waves generated by the ultrasonic generator would cause high-speed jets and micro-jets in the solution, which further results in macroscopic turbulence of solution and provides a good hydrodynamic condition for the leaching [23], [24]. In the leaching system of fine particles, these vibration waves also can contribute to the high-speed collisions of solid particles, which can accelerate the dissolution rate of fine particles [25], [26]. However, acoustic cavitation is more beneficial to the leaching of flaky tinplate scraps, and the relevant physical mechanism is drawn in Fig. 11(a). Due to the acoustic cavitation effect, microbubble clusters can be generated, and these microbubbles expand rapidly and then suddenly burst on the surface of tinplate scraps as the acoustic pressure reaches a certain value. Instantaneous high temperature and high pressure can significantly enhance the Sn dissolution on the surface of tinplate scraps.

The chemical aspect of intensifying mechanism is attributed to the chemistry and acoustoelectric synergy effects, as drawn in Fig. 11(b). During the leaching process, both the Sn and Fe can be dissolved in the NaOH-H2O2 system, and the corresponding electron loss is according to the anodic reaction of Eq. (8) and Eq. (9), respectively. On the other hand, the H2O2 oxidizer gets electrons turning into hydroxide (OH–) based on the cathodic reaction of Eq. (10). The rapid transfer of electrons can enhance the rapid anodic reaction. Under ultrasonic field, the acoustoelectric synergy effect can intensify the electron transfer which has been demonstrated in the electrochemical tests as shown in Fig. 10. This advantageous acoustoelectric synergy effect facilitates the conduction of Eqs. (8)-(10) by enhancing electron transport during the ultrasound-assisted leaching process.

It should be specially explained that the Fe is also oxidized by H2O2 to Fe2O3 which is chemically inert in the NaOH solution, while the stannate (SnO32-) is soluble in the NaOH solution with concentration of 1-4 mol/L. The differences in the chemical solubility of stannate and iron oxides give rise to the separation of Sn from the tinplate scraps. In addition, the sedimentary iron oxides on the surface of iron matrix impede the further dissolution of metallic iron, so there is almost no Fe ion in the leaching solution. Overlaying Eqs. (8)-(10), the total reaction for the Sn dissolution from tinplate scraps is summarized as Eq. (11).

In summary, under the combined effect of physical and chemical aspects, the Sn leaching rate is significantly improved and the leaching time is observably shortened. The ultrasound-assisted leaching technology and novel acoustoelectric synergy effect proposed in this work are applicable to the extraction of valuable metals from various metal-based scraps.

| Sn(s) + 6OH- = SnO32-(l) + 4e- + 3H2O | (8) |

| 2Fe(s) + 6OH- = Fe2O3(s) + 6e- + 3H2O | (9) |

| 5H2O2 + 10e- = 10OH- | (10) |

| Sn + 2Fe + 5H2O2 + 2NaOH = Fe2O3 + Na2SnO3 + 6H2O | (11) |

5. Conclusions

(1) This work provided a rapid and clean tin extraction from tinplate scraps via the ultrasound-assisted alkaline leaching treatment. Almost 100% Sn can be extracted from the tinplate scraps in NaOH solution under the following leaching conditions: ultrasound power of 40%-80% (240 W-480 W), temperature of 60 ℃, H2O2 dosage of 33.3%, liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1–20:1, and leaching time of 30 min.

(2) Low concentration of NaOH system can better reflect the advantages of ultrasound-assisted leaching. Sn leaching kinetics conducted at 1 mol/L NaOH based on the plate model demonstrated the reaction rate constant of the ultrasound-assisted leaching was 70% higher than that of conventional leaching. Compared with conventional leaching, the temperature and time of ultrasound-assisted leaching were reduced by 20 ℃ and 30 min under the same NaOH concentration.

(3) The physical and chemical effects of ultrasound played important roles in the tin dissolution from tinplate scraps with flat structure and metallic bond. In the physical aspect, acoustic cavitation effect gave rise to the generation of microbubble clusters, and the instantaneous high temperature and high pressure caused by the microbubble expanding and bursting can significantly enhance the metal dissolution on the surface. In the chemical aspect, Sn and Fe in Fe-Sn alloy can be oxidized and transferred to soluble Na2SnO3 and insoluble iron oxides in the NaOH-H2O2 system based on the following anodic reactions with bulk electron transfer: Sn(s) + 6OH- = SnO32-(l) + 4e- + 3H2O and 2Fe(s) + 6OH- = Fe2O3(s) + 6e- + 3H2O, respectively. The acoustoelectric synergy effect in the metal-based tinplate scraps caused by the ultrasound can intensify the electron transfer and further facilitate these anodic reactions, resulting in rapid tin leaching.

(4) The ultrasound-assisted leaching technology and novel acoustoelectric synergy effect proposed in this work were applicable to the extraction of valuable metals from various metal-based scraps.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their thanks to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52174263, 52004254), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (No. 222300420075, 222301420030), and the Innovative Talents Supporting Plan in Universities of Henan Province (No. 23HASTIT004) for the financial support. Special thanks were given to the Project of Zhongyuan Critical Metals Laboratory (No. GJJSGFYQ202323) for the technical assistance of leaching equipment.

Contributor Information

Guihong Han, Email: hanguihong@zzu.edu.cn.

Li Zhang, Email: zhanglicsu@zzu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Mombelli D., Buonincontri M., Mapelli C., Gruttadauria A., Barella S., Fusari F., Rinaldini D. Effect of tinplated scraps surface-to-volume ratio on the efficiency of the electrolytic detinning process. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022;19:1217–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.05.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albuquerque T.L.M., Mattos C.A., Scur G., Kissimoto K. Life cycle costing and externalities to analyze circular economy strategy: comparison between aluminum packaging and tinplate. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;234:477–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C.L., Zhang W. Study on the current situation and analysis of supply and demand of global tin resource. Conservat. Utiliz. Min. 2021;41:172–178. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 4.López-Delgado A., Lobo-Recio M.Á., Peña C., López V., López F.A. Characteristics and thermal detinning of ferrous scrap from Spanish MSW compost plants. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2005;44(2):167–183. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2004.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y.F., Liu D.C., Liu S.H., Yang B., Dai Y.N., Kong L.X., Mao J.L. Extraction of Sn from Sn-Pb-Sb alloy by vacuum distillation. Chin. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 2014;34(06):650–655. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C.M., Ma J.P., Li Y.F., Yang B., Xu B.Q. Recovery of tin from tin-coated copper-clad steel wire scrap using surface sulfuration-vacuum volatilization. Vacuum. 2023;212 doi: 10.1016/j.vacuum.2023.112052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang R.L., Qiu K.Q. Research on extracting tin and preparation of sodium stannate from slag containing tin. Min. Metall. 2008;1 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Y.F. Zheng, Study on Separating and Withdrawing Copper, tin from the Circuit Plank Sludge by Alkali Roasting, 2010 (Master thesis, Nanchang University) (in Chinese).

- 9.Jia G.B., Yang B., Liu D.C. Deeply removing lead from Pb-Sn alloy with vacuum distillation. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. Chin. 2013;23(6):1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/S1003-6326(13)62666-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X., Wu S., Shi Q., Wang J.H., Hu W.B. Influence of tensile strain on the corrosion behavior of tinplate in 0.1 mol/l NaCl solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022;17:22113. doi: 10.20964/2022.11.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X.K., Xie Y., Feng C., Ding Z.M., Li D.K., Zhou X.B., Wu T.Q. Atmospheric corrosion of tin coatings on H62 brass and T2 copper in an urban environment. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022;141 doi: 10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahmani F., Haghighi M., Vafaeian Y., Estifaee P. Hydrogen production via CO2 reforming of methane over ZrO2-Doped Ni/ZSM-5 nanostructured catalyst prepared by ultrasound assisted sequential impregnation method. J. Power Sources. 2014;272:816–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.08.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahboob S., Haghighi M., Rahmani F. Sonochemically preparation and characterization of bimetallic Ni-Co/Al2O3-ZrO2 nanocatalyst: Effects of ultrasound irradiation time and power on catalytic properties and activity in dry reforming of CH4. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;38:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahmani F., Haghighi M. Sono-dispersion of Cr over nanostructured LaAPSO-34 used in CO2 assisted dehydrogenation of ethane: Effects of Si/Al ratio and La incorporation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015;27:1684–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2015.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Y.D., Zhang B., Huang Z.Y. Separation of heavy metals from sludge by ultrasound-assisted acid leaching. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2013;36(04) (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahimi G., Rastegar S.O., Chianeha F.R., Gu T. Ultrasound-assisted leaching of vanadium from fly ash using lemon juice organic acids. RSC Advance. 2020;10:1685–1696. doi: 10.1039/D0RA90109A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang K., Zhang L.B., Lv C., Li S.W., Peng J.H., Ma A.Y., Chen W.H., Xie F. The enhancing effect of microwave irradiation and ultrasonic wave on the recovery of zinc sulfide ores. High Temp. Mater. Processes. 2017;36(6):587–591. doi: 10.1515/htmp-2015-0230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia G., Lu M., Su X., Zhao X. Iron removal from kaolin using thiourea assisted by ultrasonic wave. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012;19:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J., Wu A.X., Wang Y.M., Chen X.S. Experimental research in leaching of copper bearing tailings enhanced by ultrasonic treatment. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2008;18:98–102. doi: 10.1016/S1006-1266(08)60021-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin J.C., Ning S.Y., Zeng J.S., He Z.Y., Hu F.T., Li Y.M., Fujita T., Wei Y.Z. Leaching behavior and process optimization of tin recovery from waste liquid crystal display under mechanical activation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023;399 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habbache N., Alane N., Djerad S., Tifouti L. Leaching of copper oxide with different acid solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2009;152(2–3):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2009.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie H.M., Li S.W., Zhang L.B., Wang Y.M., Long H.L. Roasting pretreatment combined with ultrasonic enhanced leaching lead from electrolytic manganese anode mud. Metals. 2019;9(5):601. doi: 10.3390/met9050601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou S.Y., Zhang Y.J., Meng Q., Dong P., Fei Z.T., Li Q.X. Recycling of LiCoO2 cathode material from spent lithium ion batteries by ultrasonic enhanced leaching and one-step regeneration. J. Environ. Manage. 2021;277 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akçay M., Elik A., Savaşcı S. Effect of ultrasonication on extraction rate and on recovery of strontium from river sediment using flame atomic absorption spectrometry. Analyst. 1989;114(9):1079–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang J., Zhang E.D., Zhang L.B., Peng J.H., Zhou J.W., Srinivasakannan C., Yang C.J. A comparison of ultrasound-augmented and conventional leaching of silver from sintering dust using acidic thiourea. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capelo J.L., Lavilla I., Bendicho C. Ultrasonic extraction followed by sonolysis-ozonolysis as a sample pretreatment method for determination of reactive arsenic toward sodium tetrahydroborate by flow injection-hydride generation AAS. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:3732–3736. doi: 10.1021/ac010193o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]