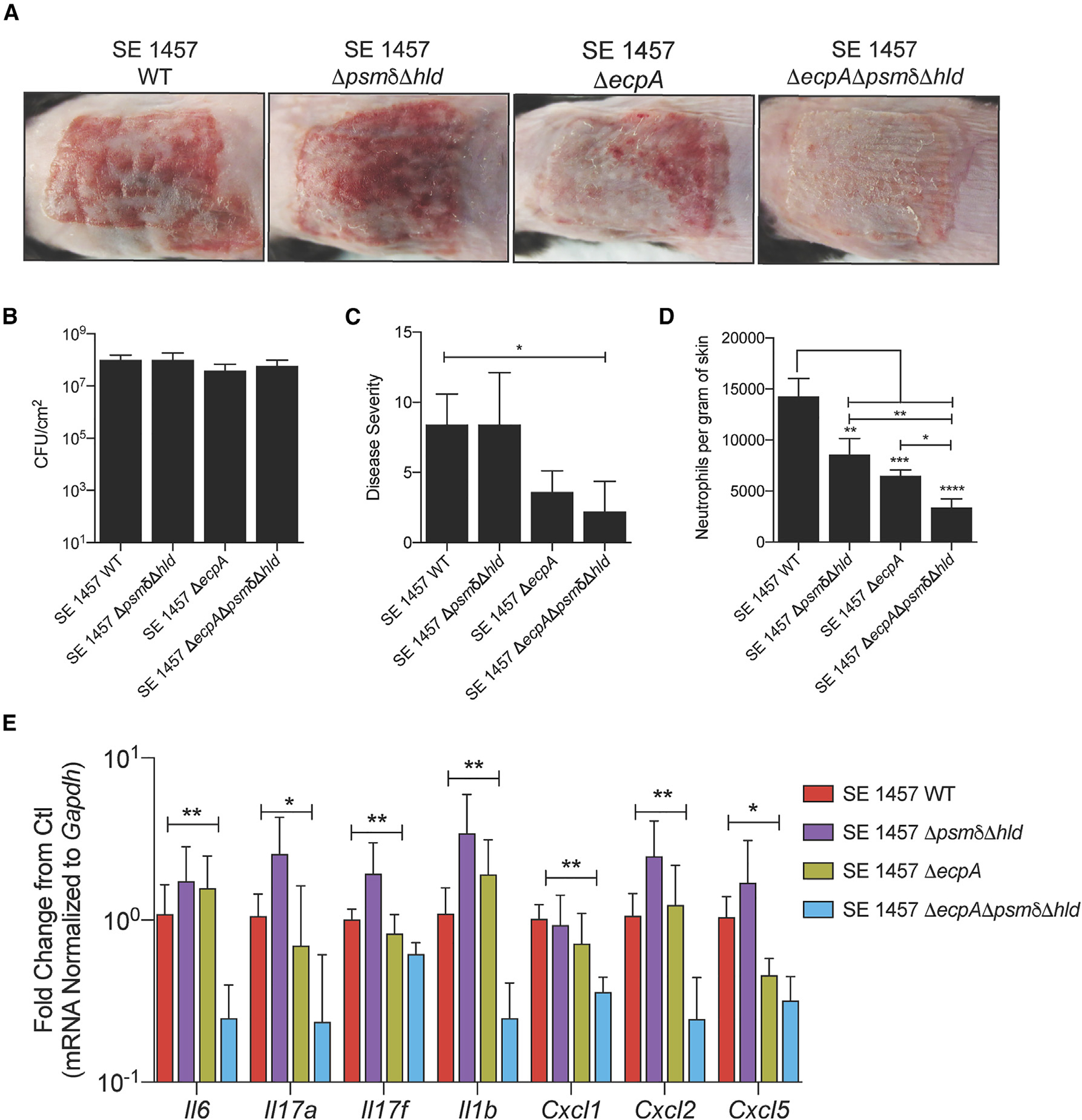

Figure 4. Both SE PSMs and EcpA promote skin inflammation in late inflammatory epicutaneous mouse model.

(A) Representative pictures of murine back skin after epicutaneous application of 1 × 107 CFU/cm2 of SE wild-type (WT), SE ΔpsmδΔhld, SE ΔecpA, or SE ΔpsmδΔhldΔecpA for 72 h (n = 5 per group).

(B and C) CFU/cm2 of live bacteria and single-blinded assessment of skin disease severity following the 72-h application of epicutaneous bacteria. See also Figure S3.

(D) Flow cytometric analysis of neutrophils (CD45+,CD11b+,Ly6G+) per gram of skin following the 72-h application of epicutaneous bacteria. Results represent mean ± SEM and a parametric unpaired one-way ANOVA analysis was used to determine statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(E) qPCR analysis of up-regulated inflammatory genes in murine skin treated for 72 h with epicutaneous application of 1 × 107 CFU/cm2 of SE wild-type or mutant strains SE ΔpsmδΔhld, SE ΔecpA, or SE ΔpsmδΔhldΔecpA (n = 5 per group). Results are representative of at least two independent experiments. Mean ± SEM and a non-parametric unpaired Kruskal-Wallis analysis was used to determine statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.