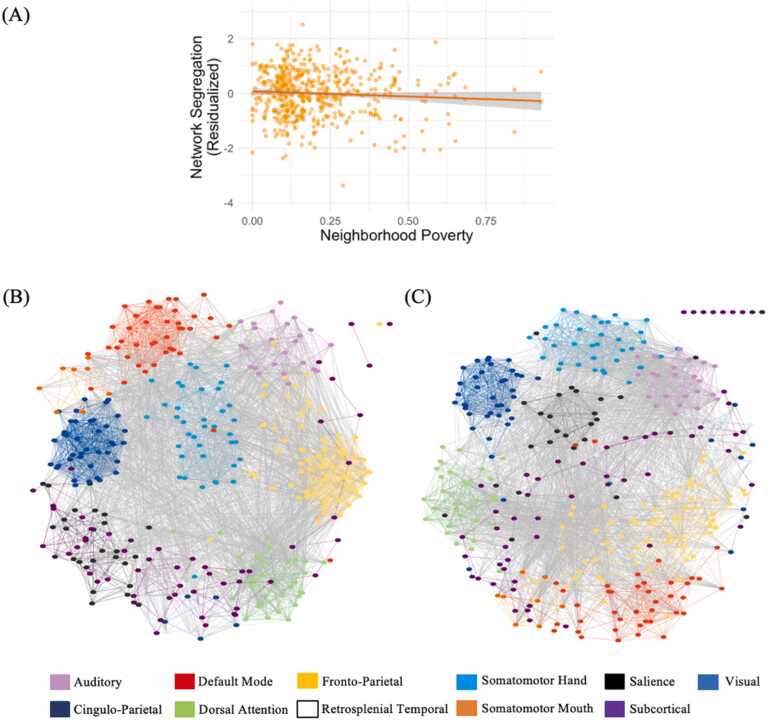

Fig. 2.

Greater exposure to neighborhood poverty during childhood is associated with reduced functional network segregation during adolescence. A) Neighborhood poverty is negatively associated with the principal component of network segregation. Network segregation is residualized against age, sex, race, head motion, scan type, mean functional connectivity, family income, and parental education. B-C) Individual graphs from a participant with the lowest (0 %; Panel B) and highest (93 %; Panel C) levels of neighborhood poverty in the sample. These graphs provide a qualitative illustration of the association between neighborhood poverty and network segregation across the sample. Each color represents a brain network, each colored line represents a within-network connection, and each gray line represents a between-network connection. For visualization purposes, only connections stronger than .30 are depicted (isolate nodes at the top right corner represent nodes without connections stronger than .30). Nodes with stronger connectivity are closer together. Overall, functional networks are more segregated (i.e., distance is shorter among nodes within networks and greater among nodes between networks) at low (Panel B) compared to high (Panel C) levels of neighborhood poverty. Spring graphs generated in Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003).