Abstract

Epilepsy is a disorder that affects around 1% of the population. Approximately one third of patients do not respond to anti-convulsant drugs treatment. To understand the underlying biological processes involved in drug resistant epilepsy (DRE), a combination of proteomics strategies was used to compare molecular differences and enzymatic activities in tissue implicated in seizure onset to tissue with no abnormal activity within patients. Label free quantitation identified 17 proteins with altered abundance in the seizure onset zone as compared to tissue with normal activity. Assessment of oxidative protein damage by protein carbonylation identified additional 11 proteins with potentially altered function in the seizure onset zone. Pathway analysis revealed that most of the affected proteins are involved in energy metabolism and redox balance. Further, enzymatic assays showed significantly decreased activity of transketolase indicating a disruption of the Pentose Phosphate Pathway and diversion of intermediates into purine metabolic pathway, resulting in the generation of the potentially pro-convulsant metabolites. Altogether, these findings suggest that imbalance in energy metabolism and redox balance, pathways critical to proper neuronal function, play important roles in neuronal network hyperexcitability and can be used as a primary target for potential therapeutic strategies to combat DRE.

Keywords: Seizure, Drug resistant epilepsy, Protein carbonylation, Proteomics

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most prevalent neurological disorders in the world, and it is estimated that 2.2 million people in the United States alone suffer from this disease [1]. Epilepsy is signified by repeated occurrence of unprovoked seizures [2]. While epilepsy is known to be caused by a variety of factors, including but not limited to genetic factors, head trauma and infection, the majority of cases are idiopathic [3]. The treatment of epilepsy largely consists of anti-seizure drugs; however, up to one third of patients do not respond to this first line treatment [3,4]. Epilepsy is unique among chronic conditions in terms of the relatively high percentage of indirect morbidity-related costs; 70% for persons with intractable epilepsy compared with an average of 11% for all persons with chronic disease [5]. Those with epilepsy carry a significantly increased risk of premature mortality - more than two-fold, as measured across all age groups [6]. Moreover, the risk for death is several-fold higher in those with uncontrolled seizures, especially deaths due to injuries and suicide [7], and those with uncontrolled seizures incur health care costs are 5 times higher compared to those in remission [8]. For those patients with medically refractory cases of epilepsy, surgery is often an option. Epilepsy surgery aims to remove areas of the brain responsible for seizure onset [9]. In cases favorable to surgery success rates can approach 90% [10]. In those cases which don’t result in complete cessation of seizures there is often at least a 75% long term reduction in seizures [11–14]. While the surgery is most often beneficial, it cannot be carried out in all patients with epilepsy and can be associated with severe side effects such as problems with memory, visual impairment, or psychiatric issues including depression and mood problems [15]. In some cases, a ketogenic diet can be implemented, emphasizing high fat content, with low carbohydrate load. This is often effective in the control of seizures, particularly in epileptic encephalopathies of infancy and childhood, but compliance with the ketogenic diet can often be difficult or have clinical side effects that necessitate discontinuation [16]. The chief anticonvulsant effects of the ketogenic diet appear to originate from its effects on energy metabolism, particularly with intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), however, the underlying cause of the epilepsy is often not known [17]. To address this issue and attempt to identify new drug targets, proteomic studies have been undertaken. Although brain tissue would provide the ideal medium for studying these relationships, several studies have attempted to find proteomic changes using less invasive techniques, such as cerebrospinal fluid, which allows comparison to age matched controls [18,19]. These studies have identified multiple potential target proteins, but are unable to address proteomic changes occurring within the brain and importantly within the seizure onset zone. To address this issue, it is possible to use epileptic tissue from epilepsy surgery and directly study changes in the brain tissue. Meriaux et al. combined MALDI imaging with a shotgun approach to compare epileptic resections to control samples and identified the leucine rich glioma inactivated 1 gene, which had been earlier implicated in epilepsy [20,21]. He et al. used 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis combined with MALDI-MS/MS to compare epileptic tissue from surgery to an autopsy sample and found an increase of apolipoprotein A1 precursor in the epileptic tissue, possibly in response to central nervous system insult [22]. Using similar techniques with comparison of surgical tissue to autopsy tissue Yang et al. identified lipid regulator acyl-CoA thioester hydrolase as being decreased in epileptic patients [23]. One drawback of these studies is the identification of a proper control. In another study Yang et al. found that the increase of apolipoprotein A1 in epileptic hippocampus compared to postmortem hippocampus was likely not due to changes in neuronal cells, but rather accounted for by extravasates [24]. For this reason, care must be taken in both choice and preparation of control samples for brain tissue. Perhaps the most promising control is to use surrounding tissue which does not display erratic signaling, but is still to be removed in the course of the surgery. In their study of glioblastomas, Lemee et al. found that using peritumoral tissue was the preferred control tissue for proteomic analysis [25].

In this study, tissue from epilepsy surgery was investigated to identify the biological processes disrupted. Three separate samples were obtained from surgical resections from each patient as defined by unique electrophysiological characteristics and monitored by subdural electroencephalography (EEG): quiescent zone (areas within the resected tissue that showed background activity without evidence of epileptiform discharges), irritative zone (area of brain tissue that generates interictal epileptiform discharges), and seizure onset zone (brain tissue that is directly responsible for the generation of seizures). This allowed a unique opportunity to examine changes within a patient with samples matched to the nearest control-adjacent tissue. To examine the tissue in the three groups, “bottom-up” proteomic was used to identify proteins with changes in expression level. To investigate a potential role of oxidatively modified proteins in seizure onset, “top-down” strategy targeting protein carbonylation was carried out as the oxidative stress was also suggested to play an important role in epilepsy [26]. Additionally, Simeone et al. showed increased oxidants in mitochondria isolated from a mouse model of epilepsy, and that a treatment including the antioxidants vitamin C and vitamin E was able to protect mice from seizures in both a genetic and drug induced model of epilepsy [27]. Protein carbonylation was selected as it represents an irreversible oxidative modification and a hallmark of exposure to oxidative stress [28,29]. Proteomics data indicate multiple pathways with altered protein levels as well as increased oxidative stress, including proteins involved in energy metabolism, redox balance, lipid metabolism and proteins with structural function. Changes on metabolic pathway dynamics were determined using activity assays of key enzymes involved in energy metabolism and redox balance and indicated a major disruption in Pentose Phosphate Pathway. These results help to provide better understanding of the mechanisms of epileptic seizure onset and may provide insight into potential therapeutic targets in drug resistant epilepsy.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample collection and processing

All samples were collected under protocol #376–12-EP approved by the Ethics Committee - Institutional Review Board (IRB) at University of Nebraska medical Center (UNMC) and University of Nebraska –Lincoln (UNL). Brain tissue utilized for the study was obtained from patients undergoing surgery for refractory epilepsy in extratemporal regions. These patients had undergone a full pre-surgical epilepsy evaluation, using noninvasive means of localizing seizure activity. The brain areas studies comprised of neocortical tissue sections of the frontal, parietal, and/or temporal regions, which were chosen based on the region of the individual patient’s seizure localization. Only sections of the cerebral neocortex were utilized for the study, to ensure tissue consistency. More primitive areas of brain, including mesocortex and allocortex, were not used for the study, even if the decision was made to resect these areas on clinical grounds. Once the decision was made to proceed with surgery, they were implanted with subdural electrode arrays, to assist in the localization and mapping of seizures (Fig. 1). Based on these studies, specific ‘zones’ were identified electrographically, consisted of a) seizure onset zone: brain region indicated by initiation of seizure activity by EEG studies, b) irritative zone: brain regions showing evidence of interictal epileptiform activity which signify an irritative process which is localized outside of seizure onset zones, and c) quiescent zone: brain regions which show normal background activity (Fig. 1). Brain tissues were collected immediately after surgical resections, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in −80 °C until further analysis.

Fig. 1.

Representative map of a patient showing the different zones removed in epilepsy surgery. Resections were as follows: seizure onset, electrodes 50–52; irritative zone, electrodes 10–12; and quiescent zone electrodes 20, 28, 36, and 44. Brain tissue samples from each zone in each patient were then used to (A) identify up−/ down-regulated proteins using LC-MS; (B) assess oxidative damage using 2D-DIGE targeting protein carbonylation, and (C) determine the activity of key enzymes.

To investigate changes in protein levels associated with seizure onset, a mass spectrometry based proteomics approach was utilized. Brain tissue from four patients who underwent surgery to treat refractive epilepsy was analyzed. Protein levels were determined by label free quantitation (LFQ) on a Waters Synapt G2 TOF by LC-MSE on three of the samples, and oxidative damage as measured by protein carbonylation was determined for all 4 samples used (Fig. 1A and B). Further, enzyme activity assays were performed to investigate the energy metabolism (Fig. 1C).

2.2. Protein extraction

Brain tissue was homogenized in Homogenization Buffer (75% MeOH and 0.15 M NaCl) in a Bullet Blender 24 (Next Advance). Two hundred μL of the Homogenization Buffer was added to each 100 mg of tissue along with approximately 50 μL of ZrO beads (Next Advance) followed by homogenization (2 min beating followed by 30 s on ice repeated 3 times or until tissue completely homogenized). Samples were incubated on ice for 2 min to settle the beads and the suspension was transferred to a new tube labeled as crude extract. Proteins were further precipitated by combining 50 μL of crude extract with 200 μL of MeOH followed by vortexing for 1 min. Samples were then centrifuged for 5 min at 15,000 × g. The supernatant was removed and the pellet allowed to air dry at room temperature. After resuspension in 200 μL Lysis Buffer (100 mM Tris pH 7.5; 8 M urea; 1 mM PMSF) dilutions of 1:10 and 1:100 in water were assayed by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific) to determine protein concentration.

2.3. Delipidation

A volume of resuspended protein in Lysis Buffer corresponding to 100 μg of protein (as determined by BCA assay) was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 3 volumes of cold acetone followed by incubation on ice for 30 min. After incubation samples were pelleted for 2 min at 15,000 ×g and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed with cold acetone 2 times and excess acetone was evaporated in a speed vac for approximately 15 min. Samples were stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.4. Denaturation and digestion

Dried delipidated pellets (containing 100 μg of protein) were resuspended in 20 μL Denaturation Buffer (25 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC), pH 8.0; 10 mM TCEP; 5% sodium deoxycholate (SDC)) and incubated at 60 °C for 10 min to fully solubilize protein. Five μL of Alkylation Buffer (100 mM iodoacetamide in water) was added and the samples were incubated in the dark for 60 min at room temperature. Samples were then diluted with 175 μL Dilution Buffer (25 mM ABC, pH 8.0) followed by the addition of 2 μL of trypsin solution (1 μg/mL in 25 mM ABC) then incubation in the dark at 37 °C overnight. Ten μL of 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was then added to quench the reaction and remove SDC (lowering pH to 5.0 precipitates SDC). After 30 min incubation pelleted SDC was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min and supernatants were transferred to new tubes for direct analysis by LC-MS.

2.5. LC-MSE analysis

A Waters nanoAcquity UPLC coupled to a Waters Synapt G2 mass spectrometer was used for proteomic analysis. Mobile phases for the UPLC consisted of Solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and Solvent B (0.1% formic acid in ACN). Two μL of digested samples was loaded onto a Trap C-18 enrichment column (0.3 × 1 mm, Waters) and washed for 3 min with 10 μL/min Solvent A. Peptides were then eluted at 0.5 μL/min onto a C-18 reversed phase nanocolumn (0.075 × 250 mm, Waters) with the following gradient: at 0 min 5% B, 95 min increase to 50% B, increased to 85% B at 96 min and held for 1 min, at 98 min decreased to 5% B and held for one minute, then increased to 85% B at 100 min and held for one minute. The gradient was then returned to 5% B at 102 min and held for 19 min to reequilibrate the column. Collection of MS data was performed using the Data Independent Acquisition (MSE) mode with a capillary voltage of 2900 V, source temperature at 70 °C and cone gas flow at 6 L/min. Spectra were acquired from 50 to 2000 m/z and MSE was collected with alternating low (4 eV) and elevated ramp (17 eV to 42 eV) energy over the range of 100–1500 m/z. All raw data files for LFQ were imported into Progenesis QI for protein identification and quantitation. All runs were aligned by the software to the most suitable reference as determined by Progenesis QI. Peak picking for the runs was performed using the most sensitive setting in the automatic sensitivity method, and a chromatographic peak width of 0.2 min was required. Data was searched against the NCBI database with peptide tolerance and fragment tolerance set to auto. Search parameters also included up to 2 missed cleavages, fixed modification of carbamiodomethyl, and variable modifications of methionine oxidation. For ion matching the requirements were set at least 2 fragments per peptide with 5 fragments per protein and one peptide per protein.

2.6. DIGE analysis of carbonylated proteins

DIGE (difference gel electrophoresis) analysis used cyanine hydrazide dyes (Cy3 and Cy5) to label protein carbonyls as previously described [30]. Briefly, 350 μg of protein from individual samples was labeled with the Cy5 fluorophore, while an additional 350 μg of protein was combined to form a pool which was labeled with the Cy3 fluorophore. Following isoelectric focusing and gel running fluorescence was visualized on a Typhoon FLA-9500 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), and images were analyzed using Progenesis SameSpots (Nonlinear Dynamics) to align and quantitate fluorescent for individual spots.

2.7. Enzyme activity assays

Proteins were extracted from brain tissue for the enzyme assays using a ratio of 100 mg brain tissue to 200 μL of PBS plus 2 μL of protease inhibitor cocktail (Prod. # 78410, Fisher) omitting EDTA. Tissue was homogenized using the Bullet Blender as described above. Following disruption homogenate was centrifuged for 5 min at 15,000 × g and the supernatant was collected for the experiments. To assay 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase activity 131.5 μL of glycyl-glycyl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.6) was combined with 10 μL of 300 mM MgCl2 and 2.5 μL of the protein supernatant at 37 °C and allowed to equilibrate. Following equilibration 2 μL of 20 mg/mL NADP was added and the reaction was again allowed to equilibrate. Finally, 2 μL of 6-phosphogluconate (20 mg/mL) was added to start the reaction and the absorbance at 340 nm was recorded on a Cary 50 spectrometer. Transketolase activity was measured through a coupled reaction with triosephosphate isomerase and glycerolphosphate dehydrogenase as the decrease of NADH resulting from the conversion of DHAP into glycerol phosphate. Briefly, 115.5 μL of glycyl-glycine buffer (250 mM, pH 7.6) was combined with 15 μL of 300 mM MgCl2, 5 μL of 0.1% TPP, 1 μL of GDH/TPI (2000 U) and 2.5 μL of the protein extract. After equilibration at 37 °C 1 μL of 20 mg/mL NADH was added and allowed to equilibrate. To begin the assay 5 μL each of xylulose-5-phosphate and ribose-5 phosphate (100 mM and 50 mM respectively) was added and the absorbance at 340 nm was recorded. Activity was normalized to protein concentration for the samples as determined using the BCA assay as described above.

2.8. Data availability

Raw data and Mascot results for protein carbonylation and peptide quantitation for label free quantification are available at ProteomeXchange (accession number PXD010415).

3. Results

3.1. Protein level changes identified by label free quantitation

Following LC-MSE the resulting spectra was processed using Progenesis QI software to identify proteins and quantitate protein levels. Overall, 409 proteins containing at least two identified peptides were found.

Repeated measures ANOVA of all three zones revealed trends in pattern rather than direct significant changes demonstrating the irritative zone as the “mix” zone between onset/silent zones and irritative zone (data not shown). To focus on the differences between extreme conditions, the seizure onset zone (seizure activity) and quiescent zone (normal background activity) pairwise analysis was performed excluding the irritative zone. Using the Progenesis QI software, pairwise repeated measures ANOVA identified 17 proteins that had a 1.1-fold change between onset and quiescent zones and a p < .10 (Table 1). Of the 17 proteins identified, two had been identified in the three-way ANOVA. Annotation of the proteins found by pairwise analysis using Blast2GO showed enrichment in molecular function for binding and catalytic activity (Fig. 2A and B). Proteins identified by the pairwise analysis mapped largely to energy pathways, and implicated potential mitochondrial imbalance.

Table 1.

Proteins identified with a p < .10 and a fold change > 1.1 comparing seizure onset to quiescent zone (n = 3).

| Accession | p-value | Protein description | FC O/Q |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| P08729 | 0.06 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 7 | 2.61 |

| A6NHL2 | 0.04 | Tubulin alpha chain-like 3 | 1.35 |

| Q6P587 | 0.05 | Acylpyruvase FAHD1, mitochondrial | 1.32 |

| Q96JH7 | 0.07 | Deubiquitinating protein VCIP135 | 1.32 |

| Q8N945 | 0.07 | PRELI domain-contain protein 2 | 1.29 |

| Q96MP5 | 0.08 | Zinc finger SWIM domain-containing protein 3 | 1.23 |

| Q01814 | 0.08 | Plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPase | 1.18 |

| P12532 | 0.09 | Creatine Kinase U-type, mitochondrial | 1.17 |

| P11177 | 0.05 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta, mitochondrial | 1.16 |

| Q6S8J3 | 0.02 | POTE ankyrin domain family member E | 1.14 |

| Q9NWU1 | 0.03 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase, mitochondrial | 1.13 |

| P22061 | 0.06 | Protein-L-isoaspartate(D-aspartate) O-methyltransferase | 1.11 |

| P06733 | 0.06 | Alpha-enolase | −1.10 |

| P07108 | 0.10 | Acyl-CoA-binding protein | −1.11 |

| Q16206 | 0.08 | Ecto-NOX dissulfide-thiol exchanger 2 | −1.12 |

| Q9UQ16 | 0.05 | Dynamin-3 | −1.12 |

| Q9NXZ1 | 0.02 | Sarcoma antigen 1 | −1.15 |

Fig. 2.

Proteins identified by proteomics analysis. (A) Molecular function of 27 proteins with change in protein levels or increased oxidation annotated using Blast2GO program for identified proteins for pairwise analysis of onset vs. quiescent zones, (B): Function of 18 proteins annotated to ‘Catalytic Activity’ in A, (C) Activity of GAPDH and the oxidative branch of the PPP show no change while transketolase shows decreased activity (n = 3; error bars +/− 1 SD), (D) Triplicate of a single patient shows reduction of TKT activity and confirms randomization procedure (n = 3; error bars +/− 1 SD).

3.2. Protein oxidative damage

Previous work has shown in animal models that induction of seizures increases reactive oxygen species, suggesting that oxidative stress may play a role in epilepsy [31–34]. Protein carbonylation is an irreversible modification of specific amino acid side chains which has been shown to affect protein function/activity, and increased protein carbonylation has been implicated in models of epilepsy [35–38]. To compare protein carbonylation between seizure onset and quiescent zones 2D-DIGE following differential labeling of carbonylated proteins with Cy3/Cy5 was used (Fig. 1 B). This method identified increased intensity in 13 spots when comparing the seizure onset zone to the quiescent zone with a p < .05 and a fold change > 1.5. Two other spots which did not have a p < .5 but had a fold change > 1.5 in three patients were included in the subsequent analysis. Eleven proteins were identified in these spots by LC-MS/MS with a mascot score greater than 50 (Table 2). Two proteins were identified in multiple spots, likely represent different isoforms (charge states) of the same protein as resolved by IEF, as lysine and arginine are major targets of carbonylation, and following carbonylation the positive charge of these residues is lost [39,40]. Proteins with catalytic function, particularly from the glycolytic pathway were the major target of protein carbonylation in seizure onset zone as compared to quiescent zone (Fig. 2A and B).

Table 2.

Proteins identified having 1.5 fold increased carbonylation with a p < .05 in the seizure onset zone compared to the quiescent zone (n = 4; proteins in bold n = 3).

| Accession | Protein description | Score | SDS* | Coverage [%] | Fold increase | ANOVA (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| P12277 | Creatine Kinase B-type | 1438 | 15 | 54 | 2.0 | 0.046 |

| P21796 | Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 | 1211 | 9 | 44 | 1.5 | 0.011 |

| P07195 | L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain | 845 | 11 | 39 | 2.2 | 0.046 |

| P18669 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | 758 | 11 | 70 | 1.6 | 0.043 |

| P00915 | Carbonic anhydrase | 656 | 8 | 55 | 1.6 | 0.010 |

| P11142 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 463 | 11 | 32 | 1.8 | 0.017 |

| P09936 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isoeyme L1 | 461 | 5 | 60 | 1.7 | 0.029 |

| P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 315 | 7 | 33 | 1.6 | 0.022 |

| P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 289 | 7 | 40 | 1.5 | 0.031 |

| P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 248 | 7 | 37 | 2.1 | 0.050 |

| P62873 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit β-1 | 166 | 4 | 19 | 2.4 | 0.041 |

| P60709 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | 159 | 5 | 59 | 1.9 | 0.003 |

| P07195 | Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | 127 | 5 | 48 | 1.7 | 0.037 |

| P60174 | Triosesphosphate isomerase | 54 | 1 | 4 | 2.8 | 0.003 |

Significant distinct sequences.

3.3. Enzymatic activity assays

The Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) is an important factor in the ability of the cell to combat oxidative stress [41]. This pathway is responsible for the production of the reducing equivalent NADPH, as well as being a branch point for the biosynthesis of purine metabolites [42–44]. As no PPP components were identified in neither the LFQ proteomics screen nor as being carbonylated by 2D-DIGE in vitro protein assays were performed to assess the activity of this pathway. Three samples were assayed for maximum activity of GAPDH, TKT, and the oxidative branch of the PPP (PPP ox (6-PGDH + G-6-PDH)) between seizure onset and quiescent zone. To control for variation across the tissue samples in each enzyme assay, samples were broken into smaller fragments and randomly combined into three fractions, one for each assay. GAPDH and PPP ox both showed no change in activity, while TKT activity was significantly reduced (Fig. 2C). To confirm randomization of tissue, TKT was assayed in a single patient’s sample in triplicate using the same randomization procedure. TKT activity was decreased (p = .01) showing that randomization of tissue was successful (Fig. 2D). Taken together with the previous results, this data indicates that glycolysis is not a preferred pathway in seizure prone tissue, and PPP may shunt ribose-5-phosphate into purine metabolism.

4. Discussion

In this study label free quantification, differential labeling to measure protein oxidative stress, and enzyme assays were used to assess molecular changes in epileptic tissue. This experimental design allowed for comparison of tissue within patients which had different pathology, in particular seizure onset zone and tissue which exhibits no seizure activity (quiescent zone), as monitored by EEG. Altered proteins were found to map to major pathways including mitochondrial function and membrane potential, central and fatty acid metabolism, and redox balance (Fig. 2 A and B).

Mitochondrial creatine kinase (CKU) was observed to have higher protein levels, while brain creatine kinase (CKB) was observed to have increased carbonylation in seizure onset areas as compared to quiescent regions. Creatine kinase is an important enzyme for the production of high energy phosphorylated metabolites which are used to rapidly restore energy to cells under conditions of high energy usage. In animal models of epilepsy, an increase in CK activity is associated with seizure activity, and knock out of CKB results in delayed seizure onset and a decrease in seizure activity seen by EEG [45–48]. The increased levels of CKB, along with the previous observations of increased activity of CK post seizure is most likely indicative of the need for the effected tissue to replace high energy phosphocreatine stores following high energy output due to seizure activity. Carbonylation of CKU may be due to increased oxidative stress in the mitochondria, or reflect basal levels of CKU carbonylation, as while the increase of CKU protein levels was not significant (p = .237), there was a trend to increased CKU levels.

Other proteins having an increase in carbonylation include voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (VDAC1), carbonic anhydrase (CA), and ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 (UCHL1). VDAC1 is the mitochondrial porin and may be damaged in response to increased production of ROS by the mitochondria [26]. It has been speculated that carbonylation of VDAC1 may result in conformational changes of the protein [49]. In this case carbonylation of VDAC1 may alter the pore and dysregulate the transfer of substrate molecules, such as ATP and Ca2+ thus effecting neuronal excitability. CA has long been implicated in seizure onsets, as CA inhibitors show anti-seizure activity and are used to treat epilepsy [50]. UCHL1 is a protein which has previously been implicated in alteration of neuronal function through its association with Parkinson’s disease, and in this disorder, is shown to be carbonylated [51,52]. UCHL1 has been shown to bind and extend the half-life of free ubiquitin in neurons, and thus potentially play a critical role in ensuring the proper function of the turnover of damaged proteins [53]. Deregulation of the ubiquitin proteasomal system in seizure onset tissue may result in aberrant protein homeostasis, affecting neuronal function and contributing to the evolution of seizures. Actin has been shown to be susceptible to protein carbonylation resulting in destabilization of actin polymers [54]. In a mouse model of epilepsy actin was shown to be destabilized following kainate treatment, and the stabilization of actin has been proposed as a therapeutic target to treat epilepsy [55–57].

Another pathway which was altered in seizure onset zone compared to quiescent zone was fatty acid metabolism. The acylpyruvase FAHD1 was shown to be increased in seizure onset zone. FAHD1 catalyzes the formation of pyruvate from acetylpyruvate, and an increase in this enzyme may be indicative of onset zone tissue utilizing fatty acids for increased energy production in lieu of glycolysis [58]. This protein also displays oxaloacetate decarboxylase activity [59]. PRELI domain-containing protein 2 (PRELID2) was also increased in the onset zone. The function of the PRELI domain is not well understood, but it has been shown that proteins containing a PRELI domain are important for mitochondrial function and protein homeostasis under conditions of oxidative stress [60,61]. These proteins also prevent apoptosis by maintaining mitochondrial potential (ΔΨm) and preventing mitochondrial fragmentation which is seen in cells under oxidative stress [62,63]. The third and final protein in this group which was increased was 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase, mitochondrial (OXSM) which plays a role in the synthesis of long chain fatty acids believed to be required for proper mitochondrial function [64]. Acyl-CoA-binding protein (DBI) levels were decreased. DBI is believed to exert neuromodulatory action via interaction with the GABA receptor, and DBI has been shown to have endozepine like activity.

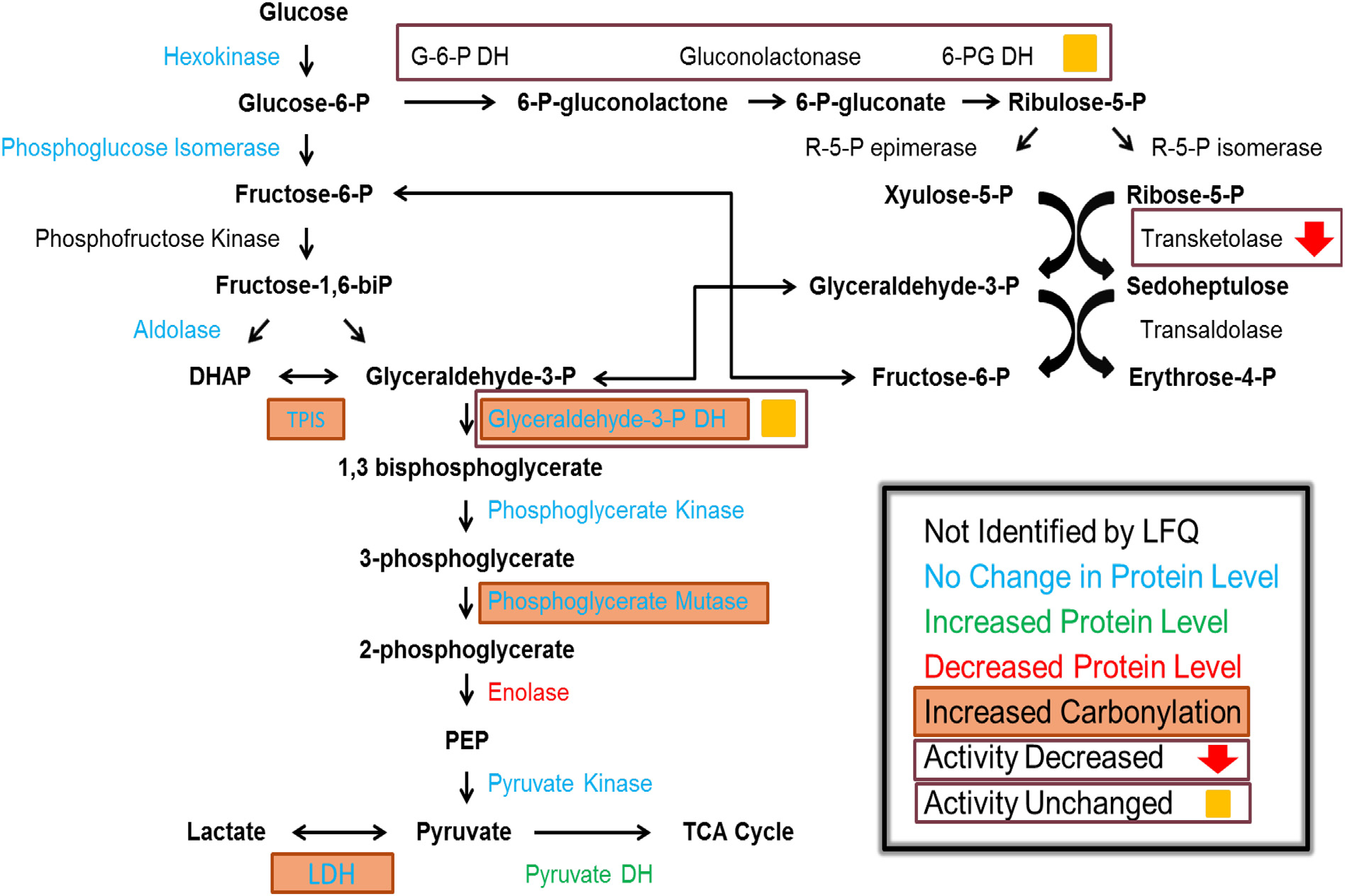

The main pathway altered in seizure onset zone was central carbon metabolism, in particular the ‘second leg’ of glycolysis starting with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and proceeding to pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) (Fig. 3). All proteins in this pathway from GAPDH through pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) were identified in the LFQ proteomic screen. One subunit of PDH was identified as having increased levels in onset zone, while a decrease in enolase (ENO1) was found. This may be explained by the observed fact that lactate dehydrogenase is a known target for anti-epileptic drugs, and it is believed that neurons in seizure prone tissues utilize lactic acid released by astrocytes for energy via the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle pathway [65]. PDH is the rate limiting step linking central carbon metabolism and the TCA cycle, and an increase in PDH activity may result in decreased bioavailability of lactic acid for the neurons to utilize, as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) directly competes with PDH for pyruvate utilization in astrocytes. While no change was observed in the levels of LDH subunits, increased carbonylation of LDH B chain was seen. This alteration may result in increased production of pyruvate from lactic acid in neurons, as increased lactic acid production by astrocytes following glutamate stimulation has been implicated in neuronal excitability [66]. Contrariwise, as the samples were of overall brain tissue, and not a specific cell types, this carbonylation may be indicative of decreased LDH activity in astrocytes allowing for increased extracellular lactic acid levels to trigger neuronal cells. Interestingly, the ketogenic diet is a high fat diet which is extremely low in both simple and complex sugars which has been shown to be effective in the treatment of many seizure epilepsy types [26,67,68]. Although the mechanism by which the ketogenic diet works is unknown, it is believed to function at least in part through the reprograming of neuronal cells to utilize ketone bodies as opposed to hexose sugars for energy production [69]. The effect of this treatment may be to shift astrocyte energy production away from glycolysis resulting in a decrease of lactic acid production, which is a direct product of glycolysis.

Fig. 3.

Summary of results from this study in central carbon metabolism. LFQ results indicated by color of protein name, increased carbonylation indicated by filled box around protein name and results of enzyme assays indicated inside open boxes.

GAPDH, a key link between glycolysis and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP), was shown to be carbonylated in seizure onset zones. This modification, in addition to the increase of oxidation in phosphoglycerate mutase 1 (PGAM1), triosephosphate isomerase (TPI), and a decrease in overall levels of ENO1 indicate that the activity of this ‘second leg’ of glycolysis may be significantly altered. This is further supported by the fact that decreases in glycolytic rate have been shown to be coupled to carbonylation of glycolytic enzymes [35]. The result of these combined insults suggest a diversion of metabolic flux into the PPP for the production of reducing equivalents of NADPH to compensate for increased oxidative stress conditions associated with epilepsy [26,31]. Serine is upstream of the production of the inhibitory neurotransmitter glycine, and disruption of serine levels by decreased production of 3-phosphoglycerate due to modification of this branch of glycolysis may alter glycine bioavailability. GAPDH is also a key regulator of the amino acid D-serine, a NMDA receptor co-agonist, and serine supplementation has recently emerged as a novel therapeutic agent in epilepsy [70–72]. Finally, GAPDH has been shown to co-localize with the inhibitory GABA receptor, and phosphorylation of this receptor by GAPDH is required for its function [73]. Alteration of GAPDH by carbonylation may prevent the activation of GABA receptor and reduce inhibitory signaling in tissue associated with seizure onset leading to uncontrolled excitation.

To further investigate the flux into and out of the PPP enzyme activity assays were performed on the oxidative branch of the PPP, TKT, and GAPDH. Interestingly, the oxidative branch of the PPP as well as the key transitional enzyme GAPDH did not show a significant change in activity, while TKT had a clear decrease in seizure onset tissue. TKT is a critical determinant of the fate of metabolites, and decreased activity would lead to a shift of metabolites into the purine metabolic pathway. Additionally, fructose-1,6-diphosphate has been shown to inhibit seizures in models of epilepsy, and it is thought that the mechanism by which this molecule acts is through the inhibition of glycolysis, thus providing increased substrates for the PPP [74–76]. This decrease in activity may also account for the alteration of glycolytic enzymes found in this study, as metabolites are shifted towards the PPP away from glycolysis. This indicates that metabolites may be entering the PPP and being utilized for the production of purine metabolites. Adenosine has emerged as an intriguing target for the treatment of epilepsy due to its action on adenosine receptors in the brain [77–80]. Another effect of shifting metabolism to the purine pathway would be the over-production of uric acid. Uric acid has been implicated in seizure burden in both animal models and in case studies [81,82]. Treatment with allopurinol, a hypoxanthine derivative which inhibits xanthine oxidase and prevents the formation of uric acid has been used successfully to treat seizures [81,83].

5. Conclusion

This study implicated key metabolic pathways involved in seizure generation and how their alteration may be related to the presence of refractory epilepsy (Fig. 4). Central carbon metabolism is balanced depending on the needs of the cell, with the PPP a major determinant of how sugars are used. In general, there are four modes that the PPP functions. The first two result in the production of ribose-5-phosphate either with or without utilization of the oxidative branch for NADPH production. These two modes are generally required in dividing cells, and in the case of neurons are not major contributing factors. The third mode is performed under oxidizing conditions, where the oxidative branch of the PPP is utilized to produce NADPH, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate is converted back into glucose-6-phosphate and completely utilized for the production of NADPH. In this case there is no production of either pyruvate or lactate for energy usage. The final mode is the utilization of the oxidative branch of the PPP to produce NADPH followed by a return to glycolysis and the production of ATP from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate. Under stress conditions consisting of both oxidative stress and energy depletion the fourth mode would be utilized. It is proposed that under normal conditions in both non-seizure and seizure prone tissue glucose is utilized by glial cells through the glycolytic pathway to produce energy (Fig. 4A and B). At the same time these cells supply energy to neuronal cells in the form of lactate. In normal brain tissue, stress causes central carbon metabolism to be routed into the pentose phosphate pathway to produce reducing equivalents of NADPH, following which it is shunted back into glycolysis (Fig. 4C). Seizure prone tissue responds similarly; however, due to a defect metabolites are moved into the purine metabolic pathway (Fig. 4D). This results in neurons depending on either distal sources of lactate or fatty acids to produce energy, as well as creating an imbalance in purine metabolites. The asynchronization of ATP formation by glycolysis and in particular the TCA cycle results in increasing reliance on adenylate kinase to maintain ATP balance. There is evidence that adenylate kinase protein levels are reduced in the neurons of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, indicating that seizure prone tissue may not be able to properly utilize this pathway properly, along with the fact that multiple targets have been utilized for the treatment of seizures in the purine metabolic pathway [84–92]. This implies at least three pathways may be suitable targets for the treatment of epilepsy. The first target is to supplement the TCA cycle to restore ATP balance to the neurons. It is widely agreed that this is one of the key mechanisms by with the ketogenic diet works, as it shifts metabolism to ketone bodies which supplement the TCA cycle directly without utilizing glucose. However, under the stress conditions which result in seizure there is high levels of oxidative stress, implicating a second target, namely supplementing the cells natural antioxidant systems. This would decrease the burden on the pentose phosphate pathway (phosphosugars) being required to produce NADPH, and in turn preventing cells from utilizing glucose can shift metabolism away from the purine pathway and production of potentially harmful metabolites such as uric acid. The third target is purine metabolism. Xanthine oxidase has been targeted in the treatment of epilepsy, showing that inhibition of later stages of purine metabolism may result in higher levels of upstream metabolites, in particular adenosine, which has emerged as a promising therapy option itself.

Fig. 4.

Response of either normal or seizure prone tissue to stress conditions. Under non stress conditions in both tissues (A and B) glucose is utilized by astrocytes which is converted into lactate to feed neurons. In stress conditions normal tissue (C) shunts metabolites through the PPP to produce NADPH before finishing glycolysis; however, in seizure prone tissue (D) these metabolites do not return to glycolysis and are directed into purine metabolism resulting in energy imbalance.

Based on the findings of this work, a large scale prospective trial that examines a cohort of individuals with varied epilepsy diagnoses could potentially be considered. By following serum markers of energy and lipid metabolism, as well as some of the indicators of oxidative stress that were discussed above in response to various treatment strategies (such as with medications, surgery, and neurostimulation techniques), it may be possible to establish relationships between these markers and specific therapeutic interventions. Additionally, analysis of nutrient intake of participants could also yield valuable information, and could suggest dietary changes or potential nutraceutical supplements that could be used to enhance seizure control. This information could then be used in the long term to develop personalized therapies for individual patients with epilepsy, using their specific markers of metabolism and oxidative stress along with their specific seizure subtype in order to determine the ideal combination of treatments necessary to optimize their seizure control.

Significance:

Epileptic seizures are some of the most difficult to treat neurological disorders. Up to 40% of patients with epilepsy are resistant to first- and second-line anticonvulsant therapy, a condition that has been classified as refractory epilepsy. One potential therapy for this patient population is the ketogenic diet (KD), which has been proven effective against multiple refractory seizure types However, compliance with the KD is extremely difficult, and carries severe risks, including ketoacidosis, renal failure, and dangerous electrolyte imbalances. Therefore, identification of pathways disruptions or shortages can potentially uncover cellular targets for anticonvulsants, leading to a personalized treatment approach depending on a patient’s individual metabolic signature.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Dr. Ron Cerny from Mass Spectrometry Core Facility at Department of Chemistry at UNL, to carry out proteomics analytical runs.

Funding source

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (P20RR017675, 5R35GM119770 and 508P20GM104320), and from National Institute of Health/United States Department of Agriculture – National Institute of Food and Agriculture (1R01DK107264/NIFA2016–67001-25301).

Abbreviations:

- DRE

Drug resistant epilepsy

- LFQ

Label free quantitation

- DIGE

Difference gel electrophoresis

- EEG

Electroencephalography

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Credit author statement

R.A.G., D.M., C.H.T.B., Z.P., H.K. and K.Sa. carried out experiments; R.A.G., D.M., C.H.T.B., C.P.B., K.Si., T.S., T.H., C.K.H. and J.A. performed data analysis and interpretation; R.A.G. and J.A. wrote paper with input from all the authors.

References

- [1].Epilepsy Across the Spectrum: Promoting Health and Understanding, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lawn N, Chan J, Lee J, Dunne J, Is the first seizure epilepsy and when? Epilepsia 56 (9) (2015) 1425–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Heron S, Scheffer I, Berkovic S, Dibbens L, Mulley J, Channelopathies in idiopathic epilepsy, Neurotherapeutics 4 (2) (2007) 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Berg AT, Identification of pharmacoresistant epilepsy, Neurol. Clin. 27 (4) (2009) 1003–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Begley CE, Famulari M, Annegers JF, Larirson DR, Reynolds TF, Coan S, Dubinsky S, Newmark ME, Leibson C, So EL, Rocca WA, The cost of epilepsy in the United States: an estimate from population-based clinical and survey data, Epilepsia 41 (3) (2000) 342–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Thhurman DJ, Logroscino G, Beghj E, Hauser WA, Hesdorffer DC, Newton CR, Scorza FA, Sander JW, Tomson T, The burden of premature mortality of epilepsy in high-income countries: a systematic review from the mortality task force of the international league against epilepsy, Epilepsia 58 (1) (2017) 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thurman DJ, Hesdorffer DC, French JA, Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: assessing the public health burden, Epilepsia 55 (10) (2014) 1479–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gao L, Xia L, Pan SQ, Xiong T, Li SC, Burden of epilepsy: a prevalence-based cost of illness study of direct, indirect and intangible costs for epilepsy, Epilepsy Res. 110 (2015) 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mansouri A, Fallah A, Valiante TA, Determining surgical candidacy in temporal lobe epilepsy, Epilepsy Res.Treat. 2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kanchanatawan B, Limothai C, Srikijvilaikul T, Maes M, Clinical predictors of 2-year outcome of resective epilepsy surgery in adults with refractory epilepsy: a cohort study, BMJ Open 4 (4) (2014) e004852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chapman K, Wyllie E, Najm I, Ruggieri P, Bingaman W, Luders J, Kotagal P, Lachhwani D, Dinner D, Lüders HO, Seizure outcome after epilepsy surgery in patients with normal preoperative MRI, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 76 (5) (2005) 710–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Fong JS, Jehi L, Najm I, Prayson RA, Busch R, Bingaman W, Seizure outcome and its predictors after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery in patients with normal MRI, Epilepsia 52 (8) (2011) 1393–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Holmes MD, Born DE, Kutsy RL, Wilensky AJ, Ojemann GA, Ojemann LM, Outcome after surgery in patients with refractory temporal lobe epilepsy and normal MRI, Seizure 9 (6) (2000) 407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Walczak T, Surgical treatment of the epilepsies, ed 2. Edited by Engel Jerome Jr, New York, Raven Press, 1993, 786 pp, illustrated, $135.00, Ann. Neurol. 35 (2) (1994) 252. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Meador K, Psychiatry problems after epilepsy surgery, Epilepsy Curr. 5 (1) (2005) 28–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Neal EG, Chaffe H, Schwartz RH, Lawson MS, Edwards N, Fitzsimmons G, Whitney A, Cross JH, The ketogenic diet for the treatment of childhood epilepsy: a randomised controlled trial, Lancet Neurol. 7 (6) (2008) 500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Georgiadis I, Kapsalaki EZ, Fountas KN, Temporal lobe resective surgery for medically intractable epilepsy: a review of complications and side effects, Epilepsy Res. Treat. 2013 (2013) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xiao F, Chen D, Lu Y, Xiao Z, Guan LF, Yuan J, Wang L, Xi ZQ, Wang XF, Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid from patients with idiopathic temporal lobe epilepsy, Brain Res. 1255 (2009) 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yu W, Chen D, Wang Z, Zhou C, Luo J, Xu Y, Shen L, Yin H, Tao S, Xiao Z, Xiao F, Lu Y, Wang X, Time-dependent decrease of clusterin as a potential cerebrospinal fluid biomarker for drug-resistant epilepsy, J. Mol. Neurosci. 54 (1) (2014) 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mériaux C, Franck J, Park DB, Quanico J, Kim YH, Chung CK, Park YM, Steinbusch H, Salzet M, Fournier I, Human temporal lobe epilepsy analyses by tissue proteomics, Hippocampus 24 (6) (2014) 628–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kalachikov S, Evgrafov O, Ross B, Winawer M, Barker-Cummings C, Boneschi FM, Choi C, Morozov P, Das K, Teplitskaya E, Yu A, Cayanis E, Penchaszadeh G, Kottmann AH, Pedley TA, Hauser WA, Ottman R, Gilliam TC, Mutations in LGI1 cause autosomal-dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features, Nat. Genet. 30 (3) (2002) 335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].He S, Wang Q, He J, Pu H, Yang W, Ji J, Proteomic analysis and comparison of the biopsy and autopsy specimen of human brain temporal lobe, Proteomics 6 (18) (2006) 4987–4996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yang JW, Czech T, Yamada J, Csaszar E, Baumgartner C, Slavc I, Lubec G, Aberrant cytosolic acyl-CoA thioester hydrolase in hippocampus of patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, Amino Acids 27 (3–4) (2004) 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang J-W, Czech T, Gelpi E, Lubec G, Extravasation of plasma proteins can confound interpretation of proteomic studies of brain: a lesson from apo A-I in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, Mol. Brain Res. 139 (2) (2005) 348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lemée J-M, Com E, Clavreul A, Avril T, Quillien V, de Tayrac M, Pineau C, Menei P, Proteomic analysis of glioblastomas: what is the best brain control sample? J. Proteome 85 (2013) 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rowley S, Patel M, Mitochondrial involvement and oxidative stress in temporal lobe epilepsy, Free Radic. Biol. Med. 62 (2013) 121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Simeone KA, Matthews SA, Samson KK, Simeone TA, Targeting deficiencies in mitochondrial respiratory complex I and functional uncoupling exerts anti-seizure effects in a genetic model of temporal lobe epilepsy and in a model of acute temporal lobe seizures, Exp. Neurol. 251 (2014) 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim JH, Sedlak M, Gao Q, Riley CP, Regnier FE, Adamec J, Oxidative stress studies in yeast with a frataxin mutant: a proteomics perspective, J. Proteome Res. 9 (2) (2010) 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kim JH, Sedlak M, Gao Q, Riley CP, Regnier FE, Adamec J, Dynamics of protein damage in yeast frataxin mutant exposed to oxidative stress, OMICS 14 (6) (2010) 689–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Boone Cory HT, Grove RA, Adamcova D, Braga CP, Adamec J, Revealing oxidative damage to enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in yeast: an integration of 2D DIGE, quantitative proteomics, and bioinformatics, Proteomics 16 (13) (2016) 1889–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liang LP, Ho YS, Patel M, Mitochondrial superoxide production in kainate-induced hippocampal damage, Neuroscience 101 (3) (2000) 563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gupta YK, Briyal S, Chaudhary G, Protective effect of trans-resveratrol against kainic acid-induced seizures and oxidative stress in rats, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 71 (1–2) (2002) 245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ramos SF, Mendonça BP, Leffa DD, Pacheco R, Damiani AP, Hainzenreder G, Petronilho F, Dal-Pizzol F, Guerrini R, Calo G, Gavioli EC, Boeck CR, de Andrade VM, Effects of neuropeptide S on seizures and oxidative damage induced by pentylenetetrazole in mice, Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 103 (2) (2012) 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Patsoukis N, Zervoudakis G, Panagopoulos NT, Georgiou CD, Angelatou F, Matsokis NA, Thiol redox state (TRS) and oxidative stress in the mouse hippocampus after pentylenetetrazol-induced epileptic seizure, Neurosci. Lett. 357 (2) (2004) 83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].England K, Odriscoll C, Cotter TG, Carbonylation of glycolytic proteins is a key response to drug-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis, Cell Death Differ. 11 (3) (2003) 252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Choi J, Rees HD, Weintraub ST, Levey AI, Chin L-S, Li L, Oxidative modifications and aggregation of Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase associated with alzheimer and parkinson diseases, J. Biol. Chem. 280 (12) (2005) 11648–11655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Doyle K, Fitzpatrick FA, Redox Signaling, alkylation (carbonylation) of conserved cysteines inactivates class I histone deacetylases 1, 2, and 3 and antagonizes their transcriptional repressor function, J. Biol. Chem. 285 (23) (2010) 17417–17424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ryan K, Backos DS, Reigan P, Patel M, Post-translational oxidative modification and inactivation of mitochondrial complex I in epileptogenesis, J. Neurosci. 32 (33) (2012) 11250–11258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Suzuki YJ, Carini M, Butterfield DA, Protein carbonylation, Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12 (3) (2010) 323–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Castegna A, Aksenov M, Thongboonkerd V, Klein JB, Pierce WM, Booze R, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA, Proteomic identification of oxidatively modified proteins in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Part II: dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2, α-enolase and heat shock cognate 71, J. Neurochem. 82 (6) (2002) 1524–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kuehne A, Emmert H, Soehle J, Winnefeld M, Fischer F, Wenck H, Gallinat S, Terstegen L, Lucius R, Hildebrand J, Zamboni N, Acute activation of oxidative pentose phosphate pathway as first-line response to oxidative stress in human skin cells, Mol. Cell 59 (3) (2015) 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stringer JL, Xu K, Possible mechanisms for the anticonvulsant activity of fructose-1,6-diphosphate, Epilepsia 49 (Suppl. 8) (2008) 101–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yang Y, Lane AN, Ricketts CJ, Sourbier C, Wei M-H, Shuch B, Pike L, Wu M, Rouault TA, Boros LG, Fan TWM, Linehan WM, Metabolic reprogramming for producing energy and reducing power in fumarate hydratase null cells from hereditary leiomyomatosis renal cell carcinoma, PLoS One 8 (8) (2013) e72179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fridman A, Saha A, Chan A, Darren E Casteel, Renate B. Pilz, Gerry R. Boss, Cell cycle regulation of purine synthesis by phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate and inorganic phosphate, Biochem. J. 454 (1) (2013) 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Holtzman D, Meyers R, Khait I, Jensen F, Brain creatine kinase reaction rates and reactant concentrations during seizures in developing rats, Epilepsy Res. 27 (1) (1997) 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Eraković V, Župan G, Varljen J, Laginja J, Simonić A, Altered activities of rat brain metabolic enzymes in electroconvulsive shock-induced seizures, Epilepsia 42 (2) (2001) 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Jost CR, Van der Zee CEEM, In ‘t Zandt HJA, Oerlemans F, Verheij M, Streijger F, Fransen J, Heerschap A, Cools AR, Wieringa B, Creatine kinase B-driven energy transfer in the brain is important for habituation and spatial learning behaviour, mossy fibre field size and determination of seizure susceptibility, Eur. J. Neurosci. 15 (10) (2002) 1692–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Streijger F, Scheenen WJJM, Van Luijtelaar G, Oerlemans F, Wieringa B, Van der Zee CEEM, Complete brain-type creatine kinase deficiency in mice blocks seizure activity and affects intracellular calcium kinetics, Epilepsia 51 (1) (2010) 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Messina A, Reina S, Guarino F, De Pinto V, VDAC isoforms in mammals, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1818 (6) (2012) 1466–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Aggarwal M, Kondeti B, McKenna R, Anticonvulsant/antiepileptic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: a patent review, Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 23 (6) (2013) 717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Choi J, Levey AI, Weintraub ST, Rees HD, Gearing M, Chin L-S, Li L, Oxidative modifications and down-regulation of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase l1 associated with idiopathic Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, J. Biol. Chem. 279 (13) (2004) 13256–13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Konya C, Hatanaka Y, Fujiwara Y, Uchida K, Nagai Y, Wada K, Kabuta T, Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in α-synuclein and UCH-L1 inhibit the unconventional secretion of UCH-L1, Neurochem. Int. 59 (2) (2011) 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Osaka H, Wang Y-L, Takada K, Takizawa S, Setsuie R, Li H, Sato Y, Nishikawa K, Sun Y-J, Sakurai M, Harada T, Hara Y, Kimura I, Chiba S, Namikawa K, Kiyama H, Noda M, Aoki S, Wada K, Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 binds to and stabilizes monoubiquitin in neuron, Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 (16) (2003) 1945–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Castro JP, Jung T, Grune T, Almeida H, Actin carbonylation: from cell dysfunction to organism disorder, J. Proteome 92 (2013) 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zeng L-H, Xu L, Rensing NR, Sinatra PM, Rothman SM, Wong M, Kainate seizures cause acute dendritic injury and actin depolymerization in vivo, J. Neurosci. 27 (43) (2007) 11604–11613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Wong M, Stabilizing dendritic stucture as a novel therapeutic approach for epilepsy, Expert. Rev. Neurother. 8 (6) (2008) 907–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sbai O, Khrestchatisky M, Esclapez M, Ferhat L, Drebrin a expression is altered after pilocarpine-induced seizures: time course of changes is consistent for a role in the integrity and stability of dendritic spines of hippocampal granule cells, Hippocampus 22 (3) (2012) 477–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Pircher H, Straganz GD, Ehehalt D, Morrow G, Tanguay RM, Jansen-Dürr P, Identification of human fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase domain-containing protein 1 (FAHD1) as a novel mitochondrial acylpyruvase, J. Biol. Chem. 286 (42) (2011) 36500–36508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pircher H, von Grafenstein S, Diener T, Metzger C, Albertini E, Taferner A, Unterluggauer H, Kramer C, Liedl KR, Jansen-Dürr P , Identification of FAH domain-containing protein 1 (FAHD1) as oxaloacetate decarboxylase, J. Biol. Chem. 290 (11) (2015) 6755–6762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kim BY, Cho MH, Kim KJ, Cho KJ, Kim SW, Kim HS, Jung W-W, Lee BH, Lee BH, Lee SG, Effects of PRELI in oxidative-stressed HepG2 cells, Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 45 (4) (2015) 419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Potting C, Wilmes C, Engmann T, Osman C, Langer T, Regulation of mitochondrial phospholipids by Ups1/PRELI-like proteins depends on proteolysis and Mdm35, EMBO J. 29 (17) (2010) 2888–2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].McKeller MR, Herrera-Rodriguez S, Ma W, Ortiz-Quintero B, Rangel R, Candé C, Sims-Mourtada JC, Melnikova V, Kashi C, Phan LM, Chen Z, Huang P, Dunner K, Kroemer G, Singh KK, Martinez-Valdez H, Vital function of PRELI and essential requirement of its LEA motif, Cell Death Dis. 1 (2) (2010) e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tsubouchi A, Tsuyama T, Fujioka M, Kohda H, Okamoto-Furuta K, Aigaki T, Uemura T, Mitochondrial protein Preli-like is required for development of dendritic arbors and prevents their regression in the drosophila sensory nervous system, Development 136 (22) (2009) 3757–3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zhang L, Joshi AK, Hofmann J, Schweizer E, Smith S, Cloning, expression, and characterization of the human mitochondrial β-ketoacyl synthase: complementation of the yeast cem1 knock-out strain, J. Biol. Chem. 280 (13) (2005) 12422–12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Sada N, Lee S, Katsu T, Otsuki T, Inoue T, Targeting LDH enzymes with a stiripentol analog to treat epilepsy, Science 347 (6228) (2015) 1362–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: a mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 (22) (1994) 10625–10629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Vining EPG, Tonic and atonic seizures: medical therapy and ketogenic diet, Epilepsia 50 (2009) 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bough KJ, Rho JM, Anticonvulsant mechanisms of the ketogenic diet, Epilepsia 48 (1) (2007) 43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Masino S, Rho J, Mechanisms of Ketogenic Diet Action, (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Löscher W, Wlaź P, Rundfeldt C, Baran H, Hönack D, Anticonvulsant effects of the glycine/NMDA receptor ligands d-cycloserine and d-serine but not R-(+)-HA-966 in amygdala-kindled rats, Br. J. Pharmacol. 112 (1) (1994) 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Klatte K, Kirschstein T, Otte D, Pothmann L, Müller L, Tokay T, Kober M, Uebachs M, Zimmer A, Beck H, Impaired d-serine-mediated cotransmission mediates cognitive dysfunction in epilepsy, J. Neurosci. 33 (32) (2013) 13066–13080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Brassier A, Valayannopoulos V, Bahi-Buisson N, Wiame E, Hubert L, Boddaert N, Kaminska A, Habarou F, Desguerre I, Van Schaftingen E, Ottolenghi C, de Lonlay P, Two new cases of serine deficiency disorders treated with l-serine, Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 20 (1) (2016) 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Laschet JJ, Minier F, Kurcewicz I, Bureau MH, Trottier S, Jeanneteau F, Griffon N, Samyn B, Van Beeumen J, Louvel J, Sokoloff P, Pumain R, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is a GABAA receptor kinase linking glycolysis to neuronal inhibition, J. Neurosci. 24 (35) (2004) 7614–7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Ding Y, Wang S, Zhang M.-m, Guo Y, Yang Y, Weng S.-q, Wu J.-m, Qiu X, Ding M.-p, Fructose-1,6-diphosphate inhibits seizure acquisition in fast hippocampal kindling, Neurosci. Lett. 477 (1) (2010) 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Ding Y, Wang S, Jiang Y, Yang Y, Zhang M, Guo Y, Wang S, M.-p. Ding, Fructose-1,6-diphosphate protects against epileptogenesis by modifying cation-chloride co-transporters in a model of amygdaloid-kindling temporal epilepticus, Brain Res. 1539 (2013) 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lian X-Y, Khan FA, Stringer JL, Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate has anticonvulsant activity in models of acute seizures in adult rats, J. Neurosci. 27 (44) (2007) 12007–12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Siebel AM, Menezes FP, Capiotti KM, Kist LW, Schaefer IDC, Frantz JZ, Bogo MR, Da Silva RS, Bonan CD, Role of adenosine signaling on pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in zebrafish, Zebrafish 12 (2) (2015) 127–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Shen HY, Sun H, Hanthorn MM, Zhi Z, Lan JQ, Poulsen DJ, Wang RK, Boison D, Overexpression of adenosine kinase in cortical astrocytes generates focal neocortical epilepsy in mice: laboratory investigation, J. Neurosurg. 120 (3) (2014) 628–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Muzzi M, Coppi E, Pugliese AM, Chiarugi A, Anticonvulsant effect of AMP by direct activation of adenosine A1 receptor, Exp. Neurol. 250 (2013) 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Zsolt K, Katalin AK, Gabor J, Janos B, Laszlo H, Renata L, Arpad D, Non-adenosine nucleoside inosine, guanosine and uridine as promising antiepileptic drugs: a summary of current literature, Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 14 (13) (2014) 1033–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Thyrion L, Raedt R, Portelli J, Van Loo P, Wadman WJ, Glorieux G, Lambrecht BN, Janssens S, Vonck K, Boon P, Uric acid is released in the brain during seizure activity and increases severity of seizures in a mouse model for acute limbic seizures, Exp. Neurol. 277 (2016) 244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Coleman M, Landgrebe M, Landgrebe A, Purine Seizure Disorders, Epilepsia. 27 (3) (1986) 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Togha M, Akhondzadeh S, Motamedi M, Ahmadi B, Razeghi S, Allopurinol as adjunctive therapy in intractable epilepsy: a double-blind and placebo-controlled trial, Arch. Med. Res. 38 (3) (2007) 313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Lai Y, Hu X, Chen G, Wang X, Zhu B, Down-regulation of adenylate kinase 5 in temporal lobe epilepsy patients and rat model, J. Neurol. Sci. 366 (2016) 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Warren TJ, Simeone TA, Smith DD, Grove R, Adamec J, Samson KK, Roundtree HM, Madhavan D, Simeone KA, Adenosine has two faces: regionally dichotomous adenosine tone in a model of epilepsy with comorbid sleep disorders, Neurobiol. Dis. 114 (2018) 45–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Boison D, Adenosinergic signaling in epilepsy, Neuropharmacology 104 (2016) 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Boison D, Role of adenosine in status epilepticus: A potential new target? Epilepsia 54 (0 6) (2013) 20–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kovács Z, Kékesi KA, Dobolyi Á, Lakatos R, Juhász G, Absence epileptic activity changing effects of non-adenosine nucleoside inosine, guanosine and uridine in Wistar albino Glaxo Rijswijk rats, Neuroscience. 300 (2015) 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Salerno C, D’Eufemia P, Finocchiaro R, Celli M, Spalice A, Iannetti P, Crifò C, Giardini O, Effect of d-ribose on purine synthesis and neurological symptoms in a patient with adenylosuccinase deficiency, Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 1453 (1) (1999) 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Stover JF, Lowitzsch K, Kempski OS, Cerebrospinal fluid hypoxanthine, xanthine. and uric acid levels may reflect glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in different neurological diseases, Neurosci. Lett. 238 (1) (1997) 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Marangos PJ, Loftus T, Wiesner J, Lowe T, Rossi E, Browne CE, Gruber HE,. Adenosinergic modulation of Homocysteine-induced seizures in mice, Epilepsia. 31 (3) (1990) 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Pérez-Dueñas B, Sempere Á, Campistol J, Alonso-Colmenero I, Díez M, González V, Merinero B, Desviat LR, Artuch R, Novel features in the evolution of adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency, Eur. J. Paediatr.Neurol. 16 (4) (2012) 343–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data and Mascot results for protein carbonylation and peptide quantitation for label free quantification are available at ProteomeXchange (accession number PXD010415).