Abstract

The present special section critical of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy or Training (ACT in either case) and its basis in psychological flexibility, relational frame theory, functional contextualism, and contextual behavioral science (CBS) contains both worthwhile criticisms and fundamental misunderstandings. Noting the °important historical role that behavior analysis has played in the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) tradition, we argue that CBS as a modern face of behavior analytic thinking has a potentially important positive role to play in CBT going forward. We clarify functional contextualism and its link to ethical behavior, attempting to clear up misunderstandings that could seriously undermine genuine scientific conversations. We then examine the limits of using syndromes and protocols as a basis for further developing models and methods; the role of measurement and processes of change in driving progress toward more personalized interventions; how pragmatically useful concepts can help basic science inform practice; how both small and large-scale studies can contribute to scientific progress; and how all these strands can be pulled together to benefit humanity. In each area, we argue that further progress will require major modifications in our traditional approaches to such areas as psychometrics, the conduct of randomized trials, the analysis of findings using traditional normative statistics, and the use of data from diverse cultures and marginalized populations. There have been multiple generational shifts in our field’s history, and a similar shift appears to be taking place once again.

Keywords: functional contextualism, contextual behavioral science, acceptance and commitment therapy, processes of change, relational frame theory, idionomic analysis, processbased therapy

If the history of science is any guide, one fact is certain: All scientific theories are wrong, we just do not know where yet. Despite its flaws, science is arguably the most progressive social institution ever created, but progress is neither linear nor certain. A lack of genuine progress can last for decades, especially when assumptions go untested, methodologies are flawed and widely used, or concepts become prematurely dominant. Criticism, self-criticism, and awareness of ignorance can be part of a process that can lead to better solutions, but only if the ultimate focus is on how to use awareness of such limitations to create effective pathways ahead. We seek such a pathway ahead here.

Behavioral and cognitive therapy have been at the forefront of an effort to use a scientific approach to learn how to create progress in the alleviation of human suffering and promotion of human prosperity. This tradition has had a positive impact on the world. In an almost generational way, every twenty years or so it has transitioned through a set of ideas designed to create progress, each building upon the previous one. After beginning with the simple idea that experimental tests of well-specified methods linked to basic learning principles would foster progress (Rachman, 1963), the field soon agreed that attending carefully to the content of cognition and emotion was also critical (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), and later that the relationship between the individual and their own experiences in such areas of acceptance, mindfulness, and values needed to be added (Hayes, 2004).

Today, there is once again a tangible sense that we need something new. This special section provides a critical examination of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy or Training (ACT in either case) and the Contextual Behavioral Science (CBS) approach that could have implications for the future of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and evidence-based intervention (EBI).

In that spirit we have assembled a team to examine what we can learn from the strengths and weaknesses of the ACT tradition that can help create progress in evidence-based interventions. Steve Hayes is the originator of many of the core ideas focused on in this special section and a former Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) President, as well as former President of the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science (ABCS), the international scientific association that has focused on CBS development. Stefan Hofmann is a major CBT researcher and also a former ABCT President who has been a leading voice for a process-based approach; and Joseph Ciarrochi is an ACT researcher, developmental scientist, and former President of ACBS who is expert in assessment and positive psychology and who has taken the lead in creating new analytic methods more adequate to the road we see ahead. For the past several years, the three of us and our colleagues have attempted to help move the field into a more process-oriented direction (e.g., Ciarrochi, Hayes, Oades, Hofmann, 2021; Ciarrochi, Sahdra, Hofmann, & Hayes, 2022; Hayes, Hofmann, & Ciarrochi, 2020a; Hayes, Hofmann, & Ciarrochi, 2020b; Hayes, Hofmann, Stanton, Carpenter, Sanford, Curtiss, & Ciarrochi, 2019; Sanford, Ciarrochi, Hofmann, Chin, Gates, & Hayes, 2022). We believe we are now at the doorstep of a major change in our field (Hayes, Ciarrochi, Hofmann, Chin, & Sahdra, 2022).

In this article, our discussion will focus on a handful of key issues relevant to our combined future. We will describe a metaphorical non-linear climb up a spiral staircase, where progressing to higher steps depends on earlier ones, but can always return to stand over areas of work that were common in the past. Progress may leave the lower steps behind, but this does not mean they were not useful or essential. We examine criticisms of the ACT/CBS program, make a few criticisms of our own, assess where we are in CBT/EBI, and briefly look at what lies ahead.

Our approach in this response article does set aside a point-by-point rebuttal in all of the many areas criticized. We are the wrong team to mount such a defense, but more importantly, it would miss the opportunity of the moment. ACT methods are recognized as evidence-based in a range of areas according to well-regarded scientific agencies or professional groups including the World Health Organization, the U. K.’s NICE guidelines, the U. S. Department of Defense, the U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and similar organizations around the world (see https://contextualscience.org/state_of_the_act_evidence for links to these reviews). In addition, there are now over 430 meta-analyses or systematic, scoping, or narrative reviews of ACT (see bit.ly/ACTmetas), including several meta-analyses of meta-analyses, which can readily be consulted by all. The body of review work by respected agencies or by independent scholars with no a priori commitments ensures a degree of seriousness and care that cannot be matched by anecdotal tales even by well-meaning critics. Thus, while we will address criticisms, our focus will be more on how these issues may bear on the future development of our field.

We will discuss the following issues in this response: philosophy of science and ethics; the role of syndromes and protocols in overall comparisons of methods; measurement and conceptual issues in understanding group versus individual improvement; how to link complexities of basic science to clinical concepts; how to broaden the definition of quality of science; and how consideration of these issues give us the opportunity for CBT itself to have a more positive impact on humanity. A process-based approach is emerging from many corners of CBT, be they cognitive (e.g., A. M. Hayes & Andrews, 2020; Reif, 2020), or behavioral (e.g., Gloster & Karekla, 2020; McCracken, 2020) and it does not do full justice to the range of issues involved to use ACT criticisms as a primary springboard. Thus, we encourage readers who find value in the more forward looking aspects of the present paper to investigate the issues involved through further readings in a process-based approach.

Otherizing the Functional Contextual Wing of CBT

We will begin with a brief look at the historical and social context of our reply so that the reader can bring an attitude of curiosity and independent thinking to what is in this extraordinary special section. The two articles by the guest editors of this special section (McKay & O’Donohue - this issue) and one of the other articles (McLoughlin & Roche – this issue) present such a dark picture of ACT and C ontextual B ehavioral S cience that we will have to expend quite a few pages of our response just so to create a context for a genuine conversation. If some claims made in their articles about ACT and CBS were true, legitimate scientific conversation would understandably have to end.

We think we have detected a source of fundamental misunderstanding (described later) but we have to note that there are scientifically flawed styles of argument in the guest editors’ articles that interfere with the more important and intellectually substantive tasks at hand. In the guest editors’ introductory article, statements are made that are factually incorrect or are not supported by needed references. For example, supposedly, “ACT at times is presented as an alternative—even a superior alternative” to “other forms of cognitive behavior therapy” but no quotes are given to help the reader evaluate that opinion (who said that, about what, and where). The mere fact that the ACT model has inspired extensive research around the globe in many specific topical areas is inexplicably treated as a scientific weakness, as is the careful listing of all available published randomized controlled trials regardless of whether the findings are good, bad, or indifferent simply because the list is both broadly focused and long. The guest editors state that “no other psychotherapy has ever been presented to have the causal efficacy to function as a treatment for such a wide variety of problems” (MS p. 4) as if listing available research is a claim of causal efficacy. The point being made is even darker and McKay and O’Donohue eventually spell it out:

Notably, this website lists no reports of any treatment failures or iatrogenic effects associated with ACT. There are no reports of studies of ACT failing to show positive outcomes or, in fact, any data providing any disconfirmatory data for any theoretical commitment made in any of the works of ACT originators or proponents (e.g., Hayes et al., 1999).

In other words, while the list of available randomized trials claims to be relatively comprehensive it is actually filtered to show only positive results.

That alone would make the list thoroughly dishonest and permanently eliminate ACT and CBS as a legitimate members of the CBT community, or indeed any serious scientific community. It is, however, demonstrably not true.

Any reader can go to this section of ACBS website (bit.ly/ACTRCTs) and read what the list aspires to be and then assess how well it lives up to its aspirations. Here is what the website currently says:

“The intent of this list is to add all randomized controlled trials of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and its components that have appeared in the scientific literature, whether alone or in combination with other methods, under the label “ACT” or the closely related terms such as “Acceptance-based behavior therapy” or “mindfulness-acceptance-commitment” and so on, regardless of outcome, language, or country of origin. Only articles appearing in a scientific journal will be included in the list. Dissertations, theses, working papers, conference presentations, studies in book chapters, and so on are not listed until they appear in a scientific journal.”

An email link is then provided (missingstudies@gmail.com) for readers to report any overlooked studies.

The list is undoubtedly not 100% comprehensive because finding studies and updating the list is a continuous and at times difficult process, especially in the last few years as the rate of published research has increased. Regardless, many hundreds of hours have been put in over many years to make it more nearly complete. It has been an especially arduous task to identify non-English research from some LAMIC countries, for example. Mainstream indexing engines simply ignore many journals from these countries, and it is an understandable point of pride for the CBS community that several hundred studies on the RCT list come from the 88% of the human population who are not in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) countries. We will return to that topic below.

As the page itself promises, however, there is no filtering based on outcomes. Filtering would defeat the stated purposes of the list: supporting accurate meta-analyses and systematic reviews, and helping researchers and practitioners find relevant research in given areas. The webpage itself tries to guide the reader:

If you are using this list to determine to what degree ACT is evidence-based in a particular area, please do not just count studies. … look at the meta-analyses and the systematic, scoping, or narrative reviews (go to bit.ly/ACTmetas), and consult the reviews of respected agencies (the World Health Organization; the NICE guidelines; NREPP and so on), or do your own systematic review. Consider processes of change, and more intensive idiographic studies, not just RCTs.

Fortunately, interested readers can easily check on the veracity of the guest editors’ claim of academic dishonesty by browsing through the RCT list themselves, or by examining the forest plots in well-done and large meta-analyses and then looking to the see if studies with negative effect sizes detected by objective reviewers are included in the list (note that secondary analyses or subsequent follow ups on the same RCT are not included, but those are easy to find from the primary reference that should be listed.) A bit of checking will show that there are dozens of studies on this list showing better outcomes for other methods over ACT. Indeed, there has been for many years a page on the ACBS website publicizing negative findings with a link to report any that are missing (https://contextualscience.org/negative_findings).

We agree that the list of ACT RCTs is very large: as of the moment it contains 1, 041 RCTs covering work with 81,101 participants in studies done by over 3, 250 unique researchers across the globe. The breadth of areas addressed is also very large, but there are good reasons for that and these reasons bear on the positive future we foresee for the CBT community, whatever one thinks of ACT per se.

The ACT model is a kind of “pilot test” of a process-oriented approach that is “universalist” in intent (Hayes et al., 2022), going beyond psychotherapy in any narrow sense of the term to topics addressed by positive psychology and intervention science generally. By design, ACT focuses on processes of change that arguably apply not just to traditional psychiatric disorders, but also to a wide range of behavioral health and social wellness areas. As a reflection of that, the populations most frequently addressed in the list of ACT randomized trials are “cancer patients” and “parents and caregivers”. Researchers and practitioners use the ACT model as a training approach in such areas as life coaching, organizational work, sports, nursing, physical therapy, health promotion, and on and on; it has moved strongly into the analysis of indirect methods of care, such as self-help books, apps, websites, and peer support programs across virtually all age ranges and populations. It appeals to providers and researchers in the developing world for reasons we will note later.

Doing a study is not making a claim, it’s asking a question, and the psychological flexibility model fits with the traditional aspiration of behavior analysis and modification to apply behavioral principles to all aspects of life. CBT began to lose that vision as psychiatric syndromes became its focus in the 1980’s, but ACT did not and after 40 years of development, it appears to have caught the attention of researchers across the globe. That is not something CBS should have to apologize for. Based on the breadth of human need in mental and behavioral health and social wellness, searching for broadly applicable principles of positive change is something our filed should aspire to and the steps taken to establish such worldwide interest and breadth of application, may serve as a useful guide for the larger CBT family of methods.

The solo or combined articles by the guest editors struggle with fairness in enough other areas that it is simply not worth addressing these in a point-by-point way. Purely as examples: they spend nearly a page on criticisms of one specific ACT study from 15 years ago on diabetes management (O’Donohue, Snipes & Soto; 2016) but not a word is spent on the detailed response to those criticisms (Gregg & Hayes, 2016) nor that the original study (Gregg et al., 2007) has since been replicated by independent teams and recent meta-analyses in the area have broadly confirmed the original findings (e.g., Sakamoto et al., 2021). The guest editors cite a meta-analysis highly critical of ACT by Ost, 2014, when there were only 60 ACT randomized controlled trials (less than 6% of those available now) but not the documentation of the over 90 errors in that report that touched upon 80% of the articles reviewed (Atkins et al., 2017; to which Ost, 2017 replied), nor the hundreds of meta-analyses published since. They extensively cite a decade-old blog by James Coyne (2012, but apparently no longer available), pointing to a putatively fatal flaw in one of the earliest ACT RCTs of the modern era based on how the missing data for two participants were handled (Bach & Hayes, 2002). A direct replication by an independent team (Gaudiano & Herbert, 2006), and a combined reanalysis that confirmed the original findings even after following all of Dr. Coyne’s recommendations (Bach, Gaudiano, Hayes, & Herbert, 2013) are not mentioned.

The guest editors’ articles (and parts of the McLoughlin and Roche article) might foster an “us versus them” mindset in CBT professionals who are unaware of the long history of contextual behaviorism and its positive role in the development of the behavioral and cognitive therapies. It is not that hard to do since the more behavioral wing of our tradition is a minority view in the modern era. Some things that made ACT initially seem surprising to the CBT community in the early days of the so-called “third wave” are actually linked to behavior analytic styles of research, measurement, and analysis that are not well understood nor widely practiced in our field and that we have argued elsewhere are now becoming particularly relevant in the era of process-based CBT (Hayes et al., 2022). Like that walk up the spiral staircase referred to earlier (perhaps one designed by Escher!), the journey of CBT and evidence-based interventions (EBI) began in process-oriented functional analytic idiographic work, moved to syndromal diagnosis, group-based analyses, and protocols validated by RCTs, and has now has climbed back over idiographic methods, but in a new and exciting form. Some (not all) of the apparent weaknesses of the CBS tradition identified in this special section are not bugs, they are features – and moreover they are ones that are very much relevant to the future development of CBT and EBI.

In our view, as a set of authors from different wings of CBT, there is no “us versus them.” At least a dozen past Presidents of ABCT hailed from the behavior analytic wing of the tradition rather than what we now think of as the CBT mainstream. Major mainstream CBT researchers have extensively examined ACT in “risky tests” and the pattern of results suggest ACT brought new and useful concepts and methods into the CBT family (e.g., see the several studies on ACT by former ABCT President Michelle Craske and her team after Arch, Eifert, Davies, Vilardaga, Rose, & Craske, 2012). We have argued elsewhere (Hayes et al., 2022) and will do so again in this paper, that a more idiographic focus n biopsychosocial processes of change should help the CBT and EBI traditions work together cooperatively to create a better future. “Otherizing” members of the family of behavioral and cognitive therapy is a step in the wrong direction. However, we must in this response address the core stated reasons underlying the attempt to “otherize” because if, as some of the special section authors claim, the CBS philosophy of science is itself manipulative or immoral, the research tradition based on that philosophy deserves to be excluded. To that topic we now turn.

Philosophy of Science

Historically, one of the most important contributions of contextual behavioral science to mainstream intervention science and the family of behavioral and cognitive therapies has been to press for greater clarity about philosophical assumptions and greater attention to the historical roots of behaviorism. The concept of “contextualism” was Stephen C. Pepper’s (1942) term for pragmatism. Contextual behavioral science, ACT, and various elements of what became the “third wave” of behavioral and cognitive therapy were and are based on the pragmatic wing of behaviorism, particularly Skinner’s radical behaviorism (Hayes, Hayes, & Reese, 1988).

Hayes clearly stated that connection in an ABCT Presidential address (Hayes, 2004) but he was not the first President of ABCT to do so. The late Neil Jacobson did that several years earlier in his Presidential address (Jacobson, 1997) that focused almost entirely on philosophy of science issues. He argued “Behavior therapy, as of 1997, has little to do with its philosophical roots in behaviorism, and we have paid a price for our departure from those roots. … contextualism provides a much needed overarching system that not only unites behavioral interventions, but has demonstrated some vitality in recent years for creating new interventions that do not emphasize cognitive therapy. The future of behavior therapy would be best served by revisiting our philosophical roots, returning to functional analytic thinking, and by attending to context.” (p. 435).

Functional contextualism is foundational to ACT and contextual behavioral science and if it is fatally flawed, so is the entire enterprise. Being clear about one’s scientific assumptions and ensuring that they are coherent is the very domain of philosophy of science. The “third-wave” is often rightly credited with increasing that focus in CBT. Because assumptions are pre-analytic and are thus scientifically incommensurable, awareness of assumptions can help soften the harsh walls and barriers between professionals. Indeed, despite significant differences, the authors of this paper have been able to cooperate well for nearly a decade, in part because of an understanding of our assumptions and places we may differ. This is not a unique event. The Inter-Organizational Task Force on Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology Doctoral Education, organized by ABCT (Klepac et al., 2012), but including ACBS as one of its members, explicitly encouraged greater attention to philosophy of science issues, hoping to foster greater consilience between the behavioral and cognitive therapies.

But cooperation requires clarity. The special section guest editors and McLoughlin and Roche present seemingly damning critiques of functional contextualism, but do so based on a mischaracterization of what functional contextualism actually is. It is thus necessary to characterize functional contextualism before returning to the criticisms and specifying how they ignore or distort what has been clearly stated.

Functional contextualism is a specific philosophy of science of relevance to psychology and behavioral science. Because of that, it is necessary to begin by stating how science is defined, how the psychological level of analysis is defined, and then to describe the goals and features of functional contextualism in the context of those definitions. Where possible we will quote direct quotes so that there can be no doubt about the stated position.

In the defining article on contextual behavioral science published in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, it was said that “from a functional and contextual perspective, scientific analysis is a social enterprise that seeks the development of increasingly organized statements of relations among events that allow analytic goals to be accomplished with precision, scope, and depth, based on verifiable experience” adding that “precision means that only a limited number of analytic concepts apply to a given case; scope means a given analytic concept applies to a range of cases; and depth means analytic concepts cohere across well-established scientific domains” (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Wilson, 2012, p. 2). In the first book on ACT, the psychological level of analysis is defined as “whole organisms interacting in and with a historical and situational context” (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999, p. 18). Those two ideas are foundational to understanding the specific ideas functional contextualism contains.

The first published description of functional contextualism was in the pages of this very journal in an article that used the example of cognition to explore the implications of functional contextualism for clinical research and practice (Hayes & Hayes, 1992). It was emphasized that the analytic unit in contextualism is the “act-in-context” and that this applies as much to the behavior of the scientist as to organisms being studied, which means it also applies to knowledge development. The article gave credit to B. F. Skinner’s radical behaviorism for the inclusion of these ideas in behavioral psychology but complained that “because Skinner embraced philosophically incompatible views, it is not possible to articulate the radical behavioral position” (p. 229). A series of publications (Hayes, 1987; Hayes, Hayes, & Reese, 1988; Morris, 1988) had already explored Skinner’s radical behaviorism as a form of contextualism. Pepper’s (1942) philosophical ideas were used, not because they were popular, but “because they point to fundamental differences in the assumptions and premises of groups of behavior analysts and therapists.” (Hayes & Hayes, 1992, p. 231), but it was quickly understood that these ideas required refinement for pragmatism to be safely used as a philosophy of science.

Readers were warned (Hayes & Hayes, 1992) that “contextualistic psychologies may differ widely depending on their goals,” that is, their specific truth criteria (p. 233). While descriptive contextualistic efforts such as social constructionism, dramaturgy, or hermeneutics sought “simply an understanding of participants in an interaction” (p. 233), functional contextualism built on Skinner’s interest in “prediction and control.” The term “control” was changed to “influence” (since control in behavior analysis also means lack of variability, which is confusing in this context) and in line with a contextualistic view of science generally, it “seeks empirically-based analyses that achieve all of these goals jointly (not any one in isolation)” (p. 233) and in ways that have precision, scope, and depth. Thus, functional contextualists seek increasingly organized statements of relations among events bearing on whole organisms interacting in and with a context considered historically and situationally that allow those interactions to be predicted-and-influenced with precision, scope, and depth and based on verifiable experience. That is the publicly stated “ultimate analytic goal” of functional contextualism.

A book chapter written at that same time (Hayes, 1993) more fully explicated more fully what problems functional contextualism is meant to solve. Clarity on these points is key in the present context because the articles by O’Donohue (this issue) and McLoughlin and Roche (this issue) regularly find flaws in pragmatism / contextualism but they misunderstand how functional contextualism attempts to address very flaws.

The core of the argument in Hayes (1993) is that pragmatism cannot work as a philosophy of science if all it means is “it works for me.” Instead, it is argued that “ultimate analytic goals are foundational in contextualism” (Hayes, 1993, p. 17). Implicit, ad hoc, unstated, and hidden purposes are roundly criticized. Instead, it is said clearly that “only explicit, stated, specific, a priori goals can make successful working a trustworthy guide” (p. 16) for science, adding that “without an explicit goal all cognitive claims by contextualists are dogmatic” (p. 17) in the sense that the claim goes beyond the cognitive basis for the claim.

It is very important to note before proceeding that the word “goal” in functional contextual writing must not be conflated with the analysis of “goals” in ACT writings. Functional contextualism is foundational for ACT, not the other way around, and the word “goal” means something fundamentally different in these two contexts. As we will show, the guest editors and McLoughlin and Roche (in line with Ruiz & Roche, 2007) have conflated these and it creates grotesque misunderstandings.

It would be inherently contradictory to treat a term that results from scientific analysis (“goals” as used in ACT) to mean the same thing as when that word is used to establish useful philosophical assumptions for that very analysis (“goals” as used in functional contextualism). To avoid this contradiction, when talking about “goals” in the context of functional contextualism, we will here regularly use the less confusing term “fully specified truth criterion” or just “truth criterion.” If one were going to use later ACT terms to describe this step, explicit and overly stated scientific values would be closer to what is meant (and occasionally ACT authors do talk about scientific values in that way: see Wilson, Whiteman, & Bordieri, 2013).

Hayes (1993) essentially argued that the problem with pragmatism as a philosophy of science is that its truth criterion is not adequately specified by such terms as “successful working.” In that chapter, James is characterized as the “first contextualistic dogmatist” since he argued that religious belief is true because “whatever its residual difficulties may be, experience shows that it certainly does work” (James, 1907, p. 133) but he never publicly and clearly specified what he was working toward. Thus, others were unfairly deprived of a right “to vote with my feet. If your goal is not mine, your useful analyses are likely to be useless for me.” (Hayes, 1993, p. 18). Instead, James merely gave examples of how religion “works”– a post hoc justification process that could be applied to any reinforced behavior, from drug addiction to rape.

Skinner is also characterized as a contextualistic dogmatist. He claimed that the purpose of science is prediction and control, but he thereby turned a public statement of the truth criterion for his brand of pragmatic psychology into a statement of fact that emerged from his scientific analysis. That is lethal for a contextualistic worldview because it creates an infinite regress (similar to the one produced by misusing the word “goal” as both the grounds for analysis and also the outcome of analysis). Hayes (1993) argued there was a far better alternative: “Viewed as a contextualist, Skinner should have said “‘My goals are to predict and control behavior.’ This is absolutely Skinner’s privilege, and it requires no defense. Any goal is legitimate within contextualism, because goals are foundational and pre-analytic. Once again, others can then vote with their feet.” (p. 20). Note, however, that when it is said that “any goal is legitimate within contextualism” that does not mean that any scientific purpose or “goal” is legitimate within functional contextualism, since functional contextualism is defined by a particular truth criterion. Rather, what is meant is that there are varieties of scientific contextualism (the very title of the book containing the Hayes, 1993 chapter; Hayes, Hayes, Reese, & Sarbin, 1993) and that each of these should be defined by their fully specified truth criteria. Criteria that are implicit, vague, incompatible, rapidly changing, or that fail to be used as a criterion for assessment and analysis were strongly criticized (see Hayes, 1993, p. 20–21). Without public and transparent criteria, people cannot then empirically evaluate the progress of a given pragmatic scientific approach via replication, and choose to participate or not in a scientific research program based on the empirical progress of the approach.

While descriptive contextualists can “readily stay true to the underlying root metaphor of contextualism” (that of the integrated act-in-context) because their “purposes do not threaten a holistic perspective”, “it is difficult to assess and to share the accomplishment of their goal” (which is the appreciation of the elements that participate in the whole) and for that reason “it is difficult to build a progressive science based on descriptive contextualism.” (Hayes & Hayes, 1992, p. 22). For functional contextualists the strengths and weaknesses are the opposite. One can “readily assess and share the accomplishments of their goals” and “know when they have constructed an analysis well enough – when they can predict-and-influence behavior with adequate precision and scope” (Hayes & Hayes, 1992, p. 24) but by specifying “influence” as part of the truth criterion, one must “distinguish between events that are -- at least in principle -- manipulable and those that are not” which creates a “the difficulty of maintaining contact with the [holistic] root metaphor” (p. 25).

In the 30 years since all of this was stated a lot has happened in ACT, RFT, and CBS, but the pre-analytic commitment to functional contextualism has not waned. Furthermore, the definition of functional contextualism has not waivered.

O’Donohue recognizes the centrality of goals in functional contextualism but he fails to realize this is about fully and publicly specifying the pragmatic truth criterion of this philosophy of science a priori. Instead, he conflates that important step with the personal goals and personal values of the individual, as discussed in ACT. Perhaps it is unfair to criticize O’Donohue on this basis, since he is simply repeating Ruiz and Roche (2007), who do the same thing in the pivotal paragraph quoted by O’Donohue:

Within contextualism, the scientist’s personal values are considered to be the basis for the development of scientific goals. Furthermore, personal values are indefensible and entitled to remain private, and pragmatic truth is established when the scientist’s analytic goals are reached. In conflict situations, therefore, the fulfillment of the scientist’s value-based personal goals is the criterion by which to assess the worth of the scientific practice. The scientist, in turn, is not, in principle accountable to others in the scientific or broader community. This explicit stance on the scientist’s accountability is reminiscent of the form of pragmatism developed by Machiavelli (p. 2).

We do agree this could be Machiavellian, but linking this position to functional contextualism is based on a logical and scholarly error that fundamentally mischaracterizes what it is. In an ACT model, personal values are indeed considered to be a primary way to evaluate personal goals (e.g., making money is not a value, it’s merely a goal; making money could be a reasonable part of a values-based journey, however, such as when a person seeks out a job so that they can parent their children in a way that lovingly provides for their security and safety). But the philosophical need for pragmatism to fully specify its truth criterion by publicly stating its “ultimate analytic goal” has nothing to do with the later ACT analysis of personal goals being made meaningful by their link to chosen values. This conflation produces multiple contradictions. It blurs the results of analysis with the pre-analytic assumptions of analysis, which are logically distinct domains; in contains the same error that Hayes (1993) criticized James for making, namely allowing post hoc rationalizations of preferences to substitute for a fully specified truth criterion stated a priori; and it has functional contextualists seemingly arguing on the one hand that the worth of scientific analysis is assessed by the accomplishment of whatever private self-interests the scientist may have, AND on the other hand, that they must state their truth criteria explicitly, specifically, and a priori so that people can vote with their feet. In short this conflation produces an incoherent mess,.

This same confusion is everywhere in the guest editors’ articles. In one of the few actual quotes of Hayes, O’Donohue says that contextualists hold to moral relativism because “‘truth’ refers to the achievement of a purpose and multiple truths are possible” (Vilardaga, Hayes, and Schelin, 2007, p. 120; as cited by O’Donohue, MS p. 8). By ending there O’Donohue leaves off the very next sentence and the immediately following paragraph that calls for a more fully specified truth criterion to solve that “multiple truth” problem.

Science is a social enterprise and if ultimate analytic goals are to be achieved with precision, scope, and depth and based on verifiable experience, then private, personal goals cannot substitute for pragmatic truth criteria that are explicit and publicly stated. The “validation” of truth in functional contextualism occurs through empirical replication across a wide variety of situational, personal, social, and cultural contexts. Replication as part of this social enterprise called science is impossible if truth criteria are hidden, unstated, and personal. The metaphor of allowing others to “vote with their feet” (used three times in Hayes, 1993), obviously makes no sense if scientific goals can be secret.

Let’s see if Machiavellianism could be hidden inside functional contextualism while staying true to functional contextualism. Imagine a psychopathic, manipulative scientist who secretly thinks, “the goal of my science is to become powerful in the academic world, by being manipulative and lying about data and publicly attacking those who interfere with my power.” By definition, if someone pursues such a goal as the anchor for their science, that is very different from pursing “prediction-and-influence with precision, scope, and depth” so this is not functional contextualism. Furthermore, these two goals would be empirically incompatible as well, because what may allow advancement based on lies and attacking would not also produce greater prediction and influence of psychological events with precision, scope, and depth and based on verifiable experience. Finally, this kind of psychopathic “science” cannot really be a contextualistic science of any kind because it does not have the features of one. Where is replication? How can I verify what you say if you are lying to me? Where is the fully specified truth criteria that allow other to vote with their feet? Only pseudoscience could result.

Confusion on these various points probably helps explain the anomaly of O’Donohue (2018) claiming that ACT research “raises clear issues about bias, pseudoscience, and intellectual vice” (p. 21), even as major scientific bodies such as the World Health Organization endorse ACT methods based on their independent research and on reviews of existing research (e.g., WHO, 2020). The same conceptual mistake also appears to be the source of McLoughlin and Roche’s entire section on moral relativism, and the earlier use of the term Machiavellian by Ruiz and Roche, 2007. Sadly, this confusion makes large sections of both of these articles and McKay and O’Donohue’s orientation article simply irrelevant to either ACT or CBS, and thus of little use as a guide for how CBS may further the development of CBT and EBI.

O’Donohue’s criticisms usefully connect with a tricky issue that is the subject of current arguments within functional contextualism when he strongly criticizes the idea that perhaps different ways of speaking about the a-ontological nature of functional contextualism need to be explored. ACT is explicitly based on evolutionary thinking (Wilson & Hayes, 2018), and evolutionary epistemology can be quite disorienting, even to other evolutionists. For example, based on modeling studies, thoughtful modern evolutionary scientists sometimes argue that humans are not necessarily connecting with a pre-organized real world in any normal sense of the term when sensing the environment (Hoffman, 2019). It is theoretically possible that as long as our sensory system promotes survival, it may be advantageous to present a simplified sensory falsehood as “reality,” much as a computer operating system can present files on the screen as blue rectangles when they in fact have neither shape nor color. Whether or not that is so scientifically, it is admittedly very hard to talk to most people that way given the naïve realism that normal human language promotes.

Learning how to communicate flexibly about proximal or strategic goals that are linked to the anchor of stated ultimate analytic goals is not sinister or dishonest. Behavior analysts have been struggling with this for more than half a century, as have many wings of science. 20 years after Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968) created the field of applied behavior analysis, they noted (1987) “The past 20 years have shown us again and again that our audiences respond very negatively to our systematic explanations of our programs and their underlying assumptions, yet very positively to the total spectacle of our programs … as long as they are left ‘unexplained’ by us.” (p. 315–316).

These founders of applied behavior analysis saw three alternatives to solving that problem:

“find ways to teach its culture to talk behavior-analytically (or at least to value behavior-analytic talk);

develop non behavior-analytic talk for public display, and see if that talk will prove as useful for research and analysis as present behavior-analytic talk, or whether two languages must be maintained; or

let it be (we represent approximately 2% of American psychology, and we are currently stable at that level)” (p. 316).

Mainstream applied behavior analysis took options a and c, and they have suffered the consequences. Sometimes student members of the CBT community are surprised to learn that clinical behavior analysis is even alive because their professors told them that Skinnerian behaviorism died long, long ago. From its beginning a few years after this foundational article, what became CBS adopted a variant of Baer et al’s (1987) option b: the creation of an accessible language system and an expanded technical basic behavior analytic account of language and cognition. The initial paper that led to ACT, RFT, and functional contextualism (Hayes, 1984) tried to show how even seemingly non-naturalistic or mentalistic terms such as “spirituality” could be helpful in scientific thinking if they oriented scientists and practitioners toward important psychological domains and if subsequent sets of functional analyses could be generated that at least partially explained how and why this domain was important. Thus, ACT deliberately has multiple language systems within it, as the pragmatic founders of ABA had proposed (Baer et al., 1987). These different ways of speaking for clinical, philosophical, and research purposes need to be kept distinct. O’Donahue compares a short list of technical behavioral principles in conditioning and learning (note, not constructs in CBT per se) with a seemingly long list of philosophical concepts, clinical terms, middle-level theoretical terms, and basic technical terms from RFT all listed under the label “Constructs in ACT.” That is not an appropriate comparison unless such a list is refined and categorized properly, which is not difficult to do by those well versed in the approach. Virtually no CBT therapist could do therapy or therapy research using only the short list of technical behavioral terms O’Donohue provides, and indeed, that fact is part of why CBT emerged from traditional behavior therapy in the first place.

Baer, Wolf, and Risley were not encouraging behaviorists to play fast and loose with the truth by speaking of talk for public use that is held to account for its impact on research and analysis, perhaps as supplemented by a technical behavioral account. They were expressing a healthy form of pragmatism that entirely comports with functional contextualism, once the need for prediction-and-influence with precision, scope, and depth is added as a “friendly amendment” to what these founders of traditional behavior analysis meant by “useful for research and analysis.”

In the eyes of a pragmatist or contextualist all language – even scientific language -- begins and ends as a purposive social behavior, not a passageway to pre-organized reality. Skinner expressed it this way: “[Scientific knowledge] is a corpus of rules for effective action, and there is a special sense in which it could be ‘true’ if it yields the most effective action possible. . . .(A) proposition is ‘true’ to the extent that with its help the listener responds effectively to the situation it describes” (Skinner, 1974, p. 235).

Machiavelli was not a scientist and Machiavellianism could never serve as a relatively adequate philosophy of science. Cheating, dishonesty, and manipulation of others cannot be the foundation of any successful science. Specifically, as it applies to the goals of functional contextualism, Machiavellian science would produce imprecision not precision of analytic concepts; limitations of scope, not scope; lack of interdisciplinary depth, not depth; and failures to replicate and thus an inability to develop increasingly organized statement of relations of event based on verifiable experience. In short, it would lead to scientific failure.

ACT and Morality

O’Donohue repeats a similar error made earlier when turning to clinical values. He states: “In the ACT model, values are only evaluated by the extent to which these work for the individual.” (MS p. 22). Again, this is upside down. Just as philosophically, clear “ultimate analytic goals” provide the truth criteria by which scientific “working” can be defined, ACT and the psychological flexibility model suggests that values do the same for individuals. The psychological flexibility model arguably provides many of the more important psychosocial supports human beings need to make values choices of this kind, in a way that is broadly similar to the arguments for values clarity in McLoughlin and Roche (this issue).

Functional contextualism is a philosophy of science, not a moral philosophy, but functional contextualists can study moral and prosocial behavior and try to learn how to foster it. They can also take moral stands as individuals, associations, or groups.

ACT is well known in evidence-based intervention for championing the centrality of values to human functioning. A wide variety of measures have been developed, and intervention programs deployed and tested. Whatever their weakness, only the most churlish critic would argue no progress has been made. We should not demand that any philosophy of science now must also become a moral philosophy, however. Science can promote prosocial behavior in safer ways.

As part of the healthcare system, ACT has indeed stayed away from telling patients what their values should be. That is virtually an ethical requirement of most applied professions unless these services are provided as part of pastoral or clergical care. Culturally speaking, the idea of respecting clients’ capacity for choice should not alone lead to concern. After all, every major spiritual and religious tradition recognizes that the individual ultimately needs to affirm their own life direction even if scripture or tradition provides a guide for these choices. There is a long and dark history of behavioral scientists judging the behavior of others and attempting to dictate moral choices to others. When reductionistic world views become moral philosophies, they then often begin to tear down spiritual, religious, and other cultural traditions that have long been central to human development – books like The God Delusion (Dawkins, 2006) are arguably an example; as may be the sad attempt to import the hidden cultural and economic biases of traditional psychiatric diagnosis into global health concerns (Jacob & Patel, 2014).

ACT seeks to empower but not dictate moral choice. Cultural humility in this area is part of why ACT has spread around the world: local experts use ACT in ways that fit their own culture and values. For example, the Muslim world has produced over 270 randomized controlled trials on ACT as well as dozens of studies about how to use the Holy Quran or other Islamic scriptures as part of ACT work (a partial list can be found at https://contextualscience.org/act_and_islamic_research). ACT has been adopted by the United States military chaplains as one of only three evidence-based methods that chaplains are trained in by the US government, and it’s arguably now the most widely accepted and used (Wortmann, Nieuwsma, Cantrell, Fernandez, Smigelsky & Meador, 2023) in part because military priests, imams, ministers, and rabbis can all see how ACT respects and supports their faith traditions. There are entire books on how the clergy or pastoral counselors can combine a wide variety of spiritual and religious traditions with ACT (e.g., see Nieuwsma, Walser, & Hayes, 2016), and ACT self-help books are available for those with specific religious beliefs (e.g., Knabb, 2022). ACT has also been combined with Elinor Ostrom’s Nobel Prize winning core design principles to support religious and prosocial groups (Atkins, Wilson, & Hayes, 2019).

Inside ACBS there are indeed stated values of the association. The recent Task Force Report on the strategies and tactics of contextual behavioral science research, for example, (Hayes et al., 2021) openly declared that “Contextual behavioral science cannot be conducted in a vacuum, blind to ethical and social values or its impact on society” (p. 180) and it goes on to list multiple prosocial goals of this intellectual and practical tradition. Just as an example, it argued that “if the goals of [the] organization or group include the promotion of prosperity, thriving, health, and wellbeing, it must also be explicit about its interest in and study of social justice, equity, fairness, privilege, bias and other social dimensions of importance.” (p. 180).

Multiple conceptual articles have been written on moral behavior from an ACT and CBS point of view (e.g., Hayes, 2022; Hayes, Gifford, & Hayes, 1998). Clinically, an ACT approach to values is far from “just do what works for you.”

In a sense, values are leaps of faith. The ACT model suggests that values choices and clarity are fostered when people have greater psychological flexibility. This includes greater cognitive and emotional flexibility. The claim is that people hurt where they care, so openness to such things as healthy guilt or sorrow over loss is thought to be critical to empowering clear value choices. Cognitive flexibility is needed to diminish mere compliance or self-coercion which tends to pull for counter control (e.g., acting inconsistently with value to experience feelings of not being coerced). The mindfulness skills of coming into the present moment and connecting fully with others via a more transcendent or spiritual sense of self is thought to be key to detecting moments where values choices are relevant and how one’s behavior impact ‘s others well-being. And finally, people need to know how to create values-based habits of action in order to complete the process of establishing intrinsic chosen qualities of being and doing as reinforcers for actual action.

There are entire books walking out the basic and applied science of values from a psychological flexibility point of view (e.g., Dahl, Plumb, Stewart, & Lundgren, 2009) but this need not be argued in the abstract or in a purely theoretical way. ACT has been applied to reducing problems that anyone would agree are immoral, and we can measure the impact it has there. Consider domestic violence, where men beat the ones they love.

By far the most common methods of working with people who are court adjudicated for domestic violence are either traditional CBT, the Duluth model, or their combination. The Duluth model adopts a feminist approach and teaches men that their violence comes from entitlement, gender bias, and the use of violence in relationships to exercise control and power over others. These methods do what some ACT critics appear to want ACT to do: they tell these men what their values should be, in this case based on feminist theory. When combined with traditional CBT, cognitive methods are then used to help the men confront the mental errors that have led to their various negative attitudes, emotions, and behavior.

Unfortunately, these programs have limited effectiveness in reducing actual violence. A recent comprehensive meta-analysis of programs targeting people who commit domestic violence found the overall effect on repeat offending was not even statistically significant (Wilson, Feder, & Olaghere, 2021). Earlier reviews found no evidence of improvement for partner reports of abuse (Feder & Wilson, 2005) and only about a 5% reduction in physical aggression for those receiving traditional CBT, Duluth intervention, or both (Babcock et al., 2004). This is clearly an area where CBT needs to get stronger. ACT may be able to help us do that.

In an ACT approach, people who commit violence toward partners are treated as whole people who have often had a difficult history themselves. Shaming of any kind is avoided because often these men have been abused as children and shame is a trigger emotion for violence towards others. The ACT groups walk these men into the hell of their own history, teaching psychological flexibility skills of openness, awareness, and values engagement and committed action. Participants are never told what they must believe or value. Instead, a context is created for these men to explore their own hearts and minds more fully. As would be expected from the model described earlier, a broader set of psychological flexibility skills are trained and then used to help the men become clearer about who and how they want to be in the world and as a partner.

That is the theory – but what is the empirical result? A recent randomized trial with court adjudicated people who commit domestic violence, published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (Zarling & Russell, 2022), found that compared to the Duluth model, although differences in domestic violence charges after 1 year were not statistically significant, ACT participants had significantly fewer violent crimes, or crimes of any kind, and they displayed fewer interpersonal violence behaviors in the eyes of their partners. An earlier study showed similar effects compared to a CBT/ Duluth combination (Zarling, Bannon, & Berta, 2019).

It is not a panacea, more data are needed, and of course any study or set of studies has flaws, but these findings look like real progress. The state of Iowa thinks so at least. As a result of these studies, Iowa is now using ACT instead of the Duluth model in addressing this significant problem, and other states are rapidly importing the approach.

Social gains of this kind should be something to applaud in the family of behavioral and cognitive therapies because they can be built on by others. There is nothing in the psychological flexibility model that is hostile to the core sensitivities of the many approaches within the CBT family. If the dystopian and demonstrably false vision of the three articles in this series that view ACT as immoral or Machiavellian were taken seriously, gains such as these and the broad welcome given ACT by spiritual and religious traditions around the world would be inexplicable.

Having addressed the most serious criticism that would if true create a rupture in the family of behavioral and cognitive therapies and would exclude ACT and CBS, we can turn to some of the additional criticisms and solutions that are proposed in these various articles. In each case we will try to use them as a springboard to consider our future as a field.

Syndromes and Protocols

In the last 40 years evidence-based treatment has been almost synonymous with the evolution of treatment protocols that target psychiatric diagnoses. Some of the articles in the present special section call for more of that approach: even larger studies with even better defined or more comprehensive protocols for even more narrowly diagnosed individuals. O’Donohue, for example, chides the Task Force on the strategies and tactics of CBS research, on which all three of the authors served (Hayes, et al., 2022) for not adopting Ost’s methodological advice (2014), which included downgrading all articles that did not contain DSM diagnoses backed up by clinical interviews.

With respect, we deliberately did not take that advice. We did not take it because it is not likely to be progressive. Applied behavioral science is “progressive” when its evidence-based concepts and methods apply more efficiently and effectively over time to a broader range of phenomena, with an increasingly precise and coherent understanding about why these effects occur.

Let’s look at what the traditional approach has wrought in our field and whether it is progressive in that sense. A study done a decade ago by Stefan Hofmann and his students identified 269 meta-analytic studies examining the efficacy of CBT and reviewed a representative sample of 106 meta-analyses (Hofmann et al., 2012). They covered virtually all DSM-defined syndromes: substance use disorder, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, depression and dysthymia, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders, eating disorders, insomnia, personality disorders, distress due to general medical conditions, chronic pain and fatigue. In these studies, the validity and utility of the DSM was rarely questioned, and the powerful forces wanting it to remain in power were not regularly called out. Perhaps that was because people believed we were making good progress. But were we?

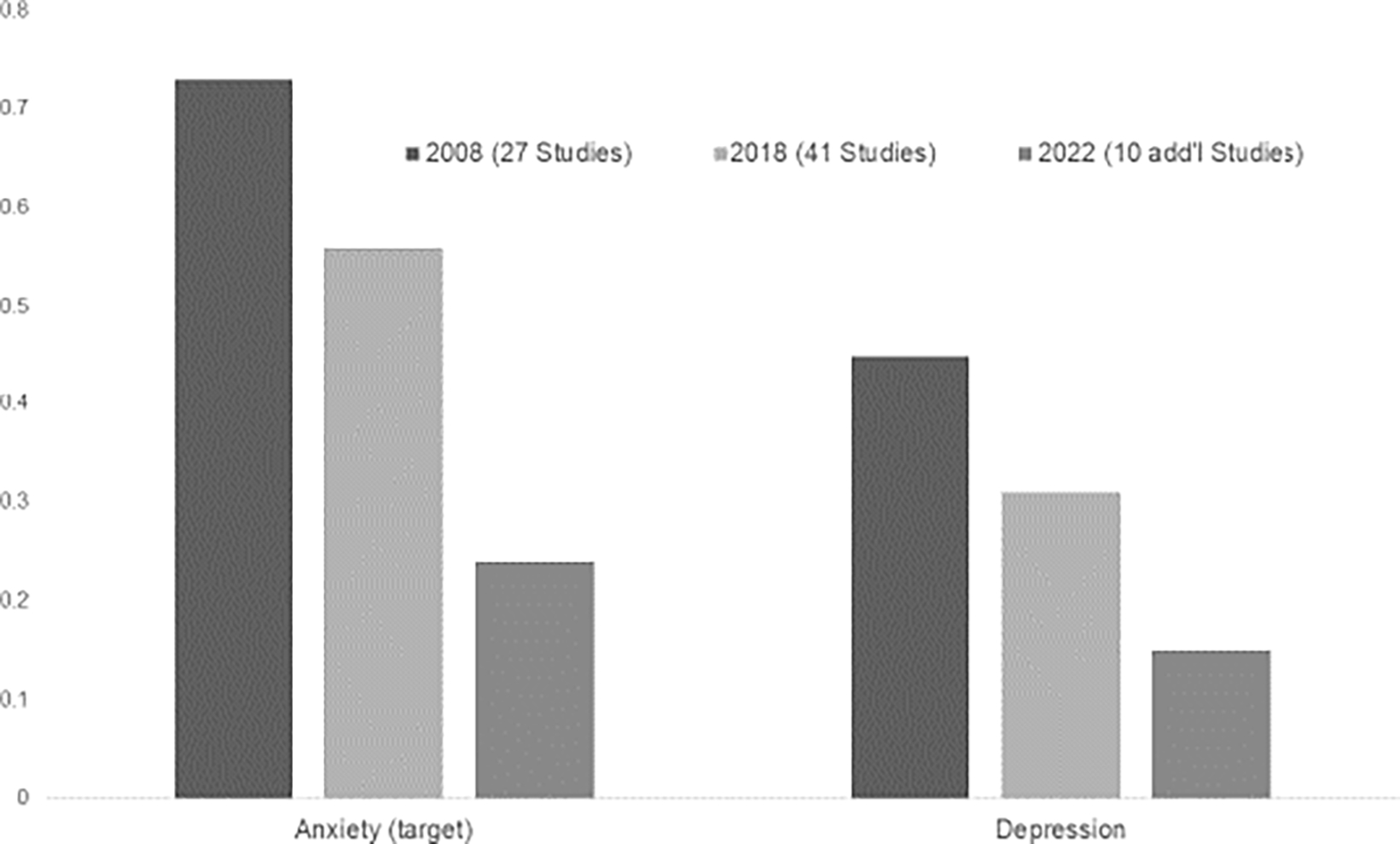

Sadly, the answer is no. For example, over the years, Hofmann and colleagues have been closely following the efficacy of CBT for anxiety disorders in higher quality randomized clinical trials, publishing three meta-analyses in high-level journals. The first one (Hofmann & Smits, 2008) reviewed all of the placebo-controlled RCTs examining CBT for anxiety disorders from between the 1st available year and March 1, 2007. Of 1,165 studies that were initially identified, 27 met all inclusion criteria for such high quality RCTs. Random effect models of completer samples yielded a pooled effect size (Hedges’ g) of 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.88–1.65) for continuous anxiety severity measures and 0.45 (90% confidence interval, 0.25–0.65) for depressive symptom severity measures.

Encouraged, and hoping for additional progress, an updated analysis was published 10 years later (Carpenter et al., 2018). It included 41 studies that randomly assigned patients (N = 2,843) with the various DSM-defined anxiety disorders to CBT or a psychological or pill placebo condition. This time, findings demonstrated more moderate placebo-controlled effects of CBT on target disorder symptoms (Hedges’ g = 0.56), and small to moderate effects on other anxiety symptoms (Hedges’ g = 0.38), depression (Hedges’ g = 0.31), and quality of life (Hedges’ g = 0.30).

The third meta-analysis (Bhattacharya et al., 2023) examined randomized placebo-controlled trials published since 2017 (the year the previous meta-analysis ended). Ten additional high-quality studies were identified with a total of 1,250 participants who met the inclusion criteria. Now only small placebo-controlled effects were observed for CBT on the target disorder symptoms (Hedges’ g = 0.24, p < 0.05) and depression (Hedges’ g = 0.15, p = n.s). Stated simply, to the authors’ surprise and dismay, placebo-controlled CBT effects appear to be shrinking over the years (see Figure 1). To adequately test whether effect sizes increase or decrease over the years, we would need to pool all studies or participants and examine whether study year is a significant and independent mediator and that has not yet been done. An earlier meta-analysis from the depression literature found that the effect sizes of CBT are falling (Johnsen & Friborg, 2015), whereas another one reported that they may not be systematically falling (Cristea et al., 2017). A similar analysis of nearly 500 RCTs of psychotherapy for youth mental health (ages 4 to 18) found over a 53-year period that effect sizes either revealed non-significant change or significant deterioration (Weisz et al., 2019)

Figure 1:

Change in placebo-controlled Hedges’ g effect sizes of randomized controlled trials over the years of publication of 3 meta-analyses.

Note that nobody seems to be suggesting that the CBT effect sizes for anxiety or depression are increasing. In fact, to our knowledge, there is scant evidence to suggest that CBT effects are increasing over the years for any DSM-defined disorder. Our CBT protocols are simply not getting better over the years.

The possible reasons for this are manifold and range from changes in the DSM criteria to the level of rigor of large funded RCTs to patient selection criteria. Whatever the reason, it’s impossible to call his trend progressive. We must now question the argument that we should continue doing what we have been doing, just do more of it, or do it better, or do it differently. The idea we are doing just fine is simply not true.

When scientific cul-du-sacs are encountered, fundamentally changing direction requires understanding of what went wrong. We believe that what has gone wrong started long ago.

The discussion of how to classify people with psychological problems has intensified again during the last few years, ignited by the publication of the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and the 11th edition of the International Classification System of Diseases (ICD) by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019. Many basic concepts of these systems can be traced back to the simplistic latent disease model of Emil Kraepelin (Kraepelin, 1893) and Eugen Bleuler (Bleuler, 1911). These ancient concepts conceived mental disorders as biological diseases, similar to viral infections. Despite the many failures of biomedical models of human suffering (e.g., the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, the dexamethasone suppression test of depression test, etc), they have remained the basis of much of our current research and treatment evaluations. Behaviors and subjective reports are seen as mere expressions of this hidden and yet to be discovered latent disease. It is the presence versus absence of this hidden disease that supposedly distinguishes “disordered” individuals from the so-called “normal” ones.

The distinction between “normality” vs. “abnormality” has formed the basis for our concepts and statistical tools in mainstream scientific psychology from the beginning. The first person ever to call himself a psychologist declared “more psychology can be learned from statistical averages than from all philosophers, except Aristotle” (translated from Wundt, 1862, p. xxv). But the psychology of individual differences was never about individuals – it was about evaluating the worth of individuals based on their differences from a normative, often idealized group. This dirty history is built into our designs, statistics, and concepts in a way that should cause all people of good will to pause.

Many psychologists still do not realize that Francis Galton was the father of eugenics, and standard statistical tools were built in part to accomplish its purposes. Such heroes of traditional behavioral science as Karl Pearson, R. A. Fisher, or Frank Yates followed in Galton’s footsteps, as advocates or even professors of eugenics. It was the vigorous intellectual support of psychology itself in the form of psychometrics, IQ testing, and psychiatric diagnosis, especially in America, that laid the scientific and legal ground-work for what became the genocide, mass murders, and euthanasia propagated by Nazi Germany. This is a part of our shared history that we as a discipline never chose to process or even to fully acknowledge. It is rare to see researchers admit that psychiatric nosology and psychometrics was from the beginning part of this enterprise to separate the “superior” people from the “inferior” people so as to decide who should propagate.

Sadly, it was. For example, Bleuler, originator of the very term “schizophrenia,” said this in his 1924 Textbook of Psychiatry:

The more severely burdened should not propagate themselves… If we do nothing but make mental and physical cripples capable of propagating themselves, and the healthy stocks have to limit the number of their children because so much has to be done for the maintenance of others, if natural selection is generally suppressed, then unless we will get new measures our race must rapidly deteriorate.

Several features of the modern era have now combined to prepare us as a field to face this history and challenge its implicit impact. The application of normative statistics to the life trajectory of the people we serve requires that between person variability reliably predict within person variability to a known degree. The key focus of practitioners trying to create improvement in particular people is a “within person variability” issue. Unfortunately, behavioral science has only recently (Molenaar, 2004) awakened to a long proven mathematical fact from the physical sciences that similarity of these sources of variability can only be assumed if the phenomena is ergodic (Birkhoff, 1931; von Neumann, 1932). Ergodicity is vanishingly rare or even absent in psychology, but the conceptual and methodological scaffolding of our field has been built assuming it.

The controversy around the classification systems became particularly heated more recently when Thomas Insel, then director of the National Institute of Mental Health, dismissed the DSM-5 as a clinically invalid system no longer deserving any federal money by his institute to examine the validity of the diagnostic categories (e.g., Insel et al., 2010). The shortcomings of the DSM and the ICD are obvious to clinicians and researchers alike. For example, it is not clear why “abnormal” shyness as defined by an arbitrary set of criteria developed by a committee translates to “social anxiety disorder” (SAD) which is then treated with an FDA approved drug, such as the SSRI medication paroxetine.

As professionals have sought alternatives to the DSM or ICD, they regularly make the same error that appears to have helped create stagnation in our field to begin with. The Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) (T. R. Insel, 2014) advocated focusing on basic mechanisms and processes of change in mental health problems that are based on scientifically well-defined psychological and neurobiological concepts as a framework for research. Unfortunately, the winners were pre-chosen (genes and brain circuits: see Insel et al., 2010, p. 749) and even the originator of this approach now admits its failure (Insel, 2021).

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) (HiTop, 2023) recommends using a more data-driven approach to define symptom clusters. This approach has similarities to investigating the structure of personality traits, which resulted in the Big Five model (O. P. John, 1990). In effect, this doubles down on the same ergodic error of the DSM itself.

We have recently argued that all models that use a “nomothetic” approach in order to answer idiographic problems are doomed to failure. Classification approaches that are oriented towards differences between persons are unable to fully understand the source of important changes within the individual. For this, we need to utilize idiographic approaches for studying processes within persons that are then build into nomothetic generalizations if and only if they improve idiographic fit: what we have called an “idionomic” approach (Hayes et al., 2022). The process-based approach stresses the importance of an individualized diagnostic process, but also emphasizes the importance of understanding how complex networks work in the context of basic principles of evolutionary theory, focusing on aspects such as variation, selection and retention of psychological, sociocultural, and biophysiological processes as typical and highly relevant adaptation strategies (Hayes et al., 2020a; 2020b).

The two meta-analysis in the current issue (Evey and Steinman; Williams et al.) appear to be carefully done and we don’t have major criticisms of them. We especially appreciate the attempt to retain intensive designs in the Evey and Steinman piece; and the direct treatment comparison focus that Williams et al. maintained. We do not question their findings as such. We note that ACT is not syndromally focused and it has only been recently that syndrome bound meta-analyses could be realistically done as its deliberately broad research agenda has finally produced enough research in specific areas to make such comparisons possible.

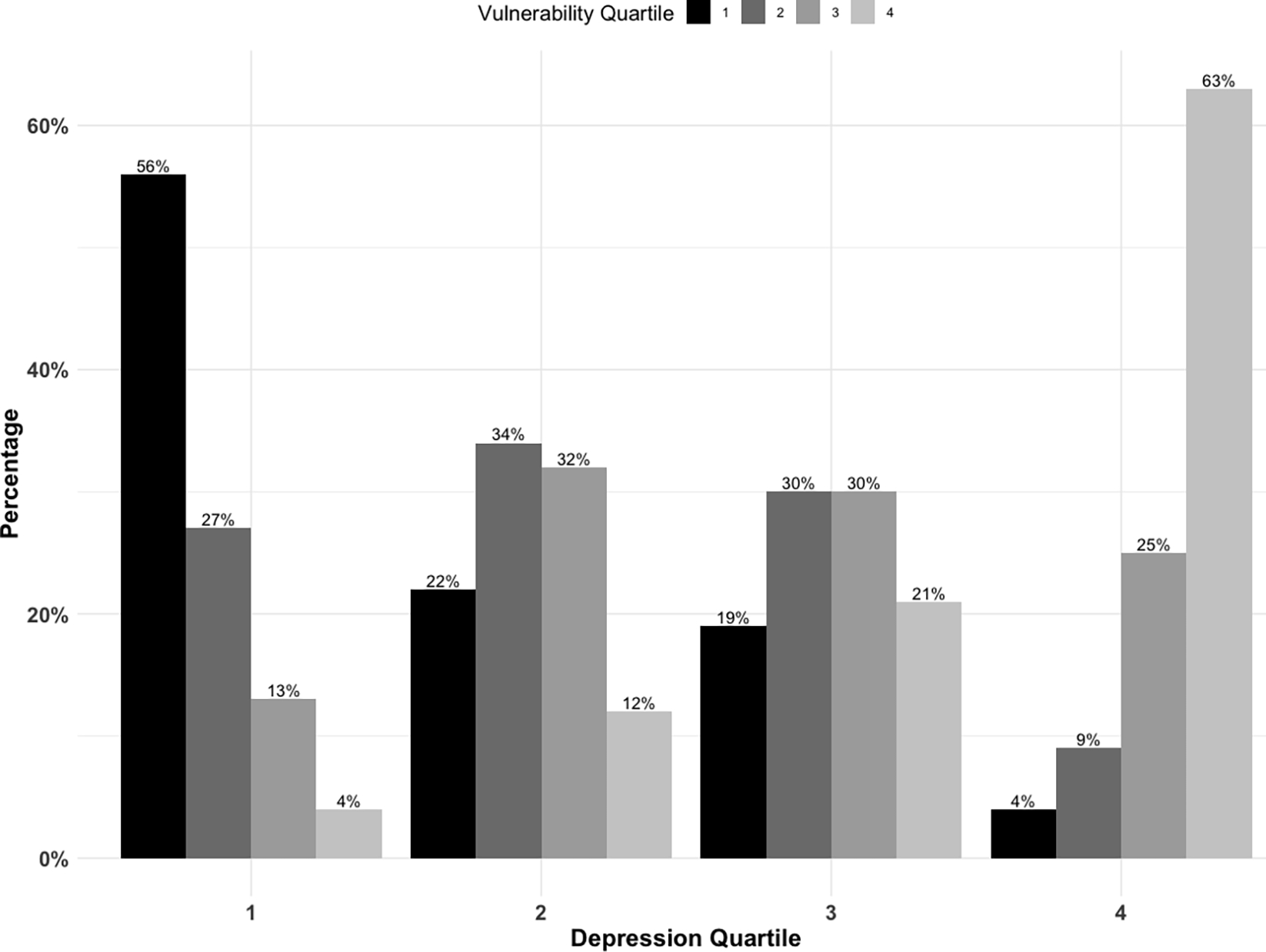

Going forward head to head comparisons of overall protocols within syndromal areas should, we believe, take a back seat to a focus on how elements of treatment models and interventions may apply within any given area, especially if moderation or idiographic response is likely. Consider the series of careful studies of ACT and CBT in Michelle Craske’s laboratory. Sometimes ACT did better (e.g., Arch et al., 2012), or the same (Craske et al., 2014), but since these effects were moderated the really exciting finding is that both methods may apply but to different people at different times. For example, in a group of clients with mixed anxiety disorders, traditional CBT outperformed ACT among those at moderate levels of baseline anxiety sensitivity, and among those with no comorbid mood disorder; ACT outperformed CBT among those with comorbid mood disorders (Wolitzky-Taylor, Arch, Rosenfield, & Craske, 2012).

If we really start focusing on that as the most important finding we need to modify our methods and analyse s to augment what we know. In traditional randomized trials the data are not collected or analyzed in a way that can give analytic priority to within person variability: the normative analyses done assume ergodicity. As a research team, we have several studies coming that show how much this may distort our model of individual relationships (e.g., Ciarrochi et al, 2023; Sahdra et al., in press). If, say, traditional CBT is currently better supported overall than ACT for depression, which it likely is (Williams et al.), yes, we need to take that fact seriously, but we also need to consider the individual, and on a process level we need to understand which elements of both approaches may be needed to obtain the best outcome.

If we want to do a better job of treatment tailoring, we need to shift our attention to idiographically important processes of change (Hayes et al., 2022), individual functional analysis, and treatment kernels that move relevant processes. While traditional mediation can arguably be a start, it is critical to begin to examine these issues idiographically because traditional statistical methods of mediation cannot fully meet their own analytic assumptions and estimated mediation effects may not apply to many or even any individuals (Hofmann, Curtiss, & Hayes, 2020).

The broader issue is that diagnoses are here to support treatment decisions. However, the DSM or ICD categories are of limited (if any) clinical utility. A traditional diagnosis has virtually no clinical implications in part because treatment is an individual issue, and the ergodic error prevents top-down normative categories from having powerful and reliable idiographic implications. This simply cannot be where our field stops.

What we need are functional analytic concepts that link client processes to treatment kernels within a coherent model. ACT is just a beginning example of that approach. So far ACT treatment kernels appear to work in a broadly coherent way (e.g., Levin, Hildebrandt, Lillis, & Hayes, 2012; Villatte, Vilardaga, Villatte, Vilardaga, Atkins, & Hayes, 2016). With replication by multiple independent teams, and the wide involvement of practitioners, that can be built upon. As this work enters into a modern idionomic era, we are certain to find that all of our current models are flawed. Scientific skepticism will help us going forward. Scientific cynicism will not.

Making Measurement Useful

Two of the articles in the special issue (Arch, Fishbein, Finkelstein, & Luoma; McLoughlin and Roche) argue that some of the common core measures used to assess psychological flexibility, such the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ and AAQ2), are hobbled or even invalid because they correlate moderately with neuroticism and factor analysis indicate that AAQ items load on a neuroticism factor. McLoughlin and Roche in particular concludes that the AAQ is simply a measure of neuroticism, and as their title suggests, extends this to the idea that all ACT process research is invalid or nearly worthless once the AAQ is eliminated.

The AAQ is old, undoubtedly has weaknesses, and is rapidly being superseded by arguably better measures. Putting aside even the various statistical concerns, neither the AAQ I nor AAQ II assess the entire psychological flexibility model as it is understood today (e.g., there are no items on attentional flexibility). On that basis alone the AAQ is not a fully adequate measure of this formative concept, since formative concepts do not assume that their elements can be eliminated and not including an element can change the conceptual domain of the construct (Coltman et al., 2008). The AAQ has been a useful and progressive part of a 40 year research and practical journey, however, and that in our opinion it would be regressive for AAQ work to be unduly dismissed. It has helped foster an increasing focus on processes of change and it has provided clinicians with clinical targets that are widely understood and useful. The AAQ has successfully demonstrated mediation in at least 37 studies (Hayes et al, 2022), and several of these designs control for time 1 measures of negative symptoms that correlate with neuroticism or add additional possible mediators that do so. Furthermore, even if the AAQ is crossed off the list entirely, other measures of psychological flexibility and mindfulness are still the single most common successful mediator known in all of treatment science (Hayes et al., 2022).

The AAQ was an initial process-based step which has arguably led to further improvements in measurement and intervention. The bigger question now is, how do we improve on process measures including the AAQ? McLoughlin and Roche’s suggestion is that we double down on traditional psychometric approaches, such as those that focus on the factor structure of measures based on large groups of individuals. We wish to suggest a profoundly different approach, but to do so, we need to discuss the traditional approach and why we believe it will not lead to measures that rise to the challenges of today.

Traditional psychometric approaches are often dominated by a game that might be called “Big-5 Gotcha.” In Big-5 Gotcha, the goal is to take any new measure and then see if it correlates with one of the extremely broad big five factors of extraversion, neuroticism, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. If it does, then you get to say “gotcha”. Here is how McLoughlin and others play big-5 gotcha.

Show that the AAQ correlates moderately with neuroticism ( say .6 to .7)

Show that it loads on a neuroticism factor

Say “gotcha” and then claim the measure is “just neuroticism” and is therefore not measuring what it is supposed to. Toss it out.

This game makes some sense within the traditional psychometric worldview. Measures are assumed to reflect latent constructs which are implicitly assumed to be “real things.” Neuroticism is thing-like, a kind of giraffe in a forest with four other types of animals, extraversion, neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness. In this worldview, creating a new measure is like claiming you have discovered a new animal. Psychometricians are naturally skeptical. You’ve got to prove that this new animal is not really one of the already existing animals. You don’t want to give two different names to the same animal, whether that be giraffe or neuroticism.

This way of thinking is usually based on the assumptions of elemental realism (Hayes et al., 1988): Measures point to true elements in a great world-machine and our goal is to model it. To do so we need to identify and name the parts and then describe how they work together by using structural equation modeling to construct complex measurement and path models that represent the “true” relationships between variables.

The functional contextualist, in contrast, does not assume a measure points to pre-organized reality (Ciarrochi & Bailey, 2008; Hayes et al., 1988). Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t, but that just is not the primary goal of functional contextualism. F unctional contextualists want measures that help guide them while intervening in and with the real world. They do not ask, which is the real thing, neuroticism or psychological flexibility? They ask, which measure gives me the most useful information to help my client in ways that lead to positive outcomes?

To illustrate how the treatment and conceptual utility question changes our perspective on measurement, let’s consider items from the AAQ-2 and from Neuroticism (Gow et al., 2005).

For third wave CBT practitioners, high scores on the AAQ-2 items are much more informative than on the neuroticism items. If someone is afraid of their feelings, then you can help them to experience those feelings in a safe space so they become less afraid. If someone believes that memories interfere with a fulfilling life, you can help them learn to carry their memories with them as they work towards what matters. Each of the AAQ-2 items link clearly to ACT theory and intervention processes. In contrast, the neuroticism items don’t provide the ACT or third-wave CBT practitioner any direction, other than knowing the person gets frequently distressed.