Abstract

Background:

Over 700 hospitals participate in the ACS-NSQIP, but most pancreatectomies are performed in 165 centers participating in the pancreas procedure-targeted registry. We hypothesized these hospitals (“targeted hospitals”) may provide more specialized care than those not participating (“standard hospitals”).

Study design:

The 2014–2019 pancreas-targeted and standard ACS-NSQIP registry were reviewed regarding patient demographics, comorbidities, and perioperative outcomes using standard univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses. Primary outcomes included 30-day mortality and serious morbidity.

Results:

The registry included 30,357 pancreatoduodenectomies (80% in targeted hospitals) and 14,800 distal pancreatectomies (76% in targeted hospitals). Preoperative and intraoperative characteristics of patients treated at targeted versus standard hospitals were comparable. On multivariable analysis, pancreatoduodenectomies performed at targeted hospitals were associated with a 39% decrease in 30-day mortality [odds ratio (OR) 0.61, 95% confidence intervals 0.50–0.75], 17% decrease in serious morbidity [OR 0.83 (0.77–0.89)], and 41% decrease in failure-to-rescue [OR 0.59 (0.47–0.74)]. These differences did not apply to distal pancreatectomies. Participation in the targeted registry was associated with higher rates of optimal surgery for both pancreatoduodenectomy [OR 1.33 (1.25–1.41)] and distal pancreatectomy [OR 1.17 (1.06–1.30)].

Conclusion:

Mortality and failure-to-rescue rates after pancreatoduodenectomy in targeted hospitals were nearly half of rates in standard ACS-NSQIP hospitals. Further research should delineate factors underlying this effect and highlight opportunities for improvement.

Keywords: NSQIP, pancreatectomy, failure-to-rescue, quality, complication, mortality

INTRODUCTION

The goal of the ACS-NSQIP (American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program) is to improve surgical outcomes by collecting and disseminating perioperative data.1,2 Improving outcomes is particularly important for procedures like pancreatectomies, which carry significant perioperative risks.3 Hospital participation in the ACS-NSQIP has been associated with long-term reductions in morbidity, mortality, and surgical site infections.4 With the addition of the procedure-targeted datasets, more specific variables of certain procedures are now collected to further improve those procedures. NSQIP hospitals that perform the minimum number of 1,680 cases per year may voluntarily opt in to provide procedure-targeted data. While there are no qualifications specific to pancreatectomies for targeted registry participation, participating hospitals are usually high-volume centers with dedicated clinical pathways or quality improvement initiatives centered around these procedures.5,6 Hospitals that target pancreatectomy are asked to collect all cases if they perform fewer than 100 per year or they may sample a majority if they perform more than 100 per year. This process of self-selection has the potential to introduce selection bias between the two datasets.7

While the addition of procedure-specific variables is intended to improve risk adjustment, how generalizable these datasets are is unclear because the hospitals that choose to participate may have different patient characteristics, referral patterns, and clinical pathways. Hospitals participating in the procedure-targeted registries may be more likely to have dedicated clinical pathways, higher volume of cases, and better ancillary support, but the patient population may be more complex. Last, hospitals with more resources may be more likely to justify the additional cost of opting into the procedure-targeted NSQIP. In this regard, we hypothesized that the outcomes of patients undergoing pancreatectomy in hospitals participating in the procedure-targeted registry may be superior and sought to explore the potential differences between the pancreas-targeted and the non-targeted (“standard”) ACS-NSQIP registries by comparing the patient population and clinical outcomes of patients treated in hospitals participating in these registries.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

This analysis was retrospective using prospectively collected data from the standard and the pancreas-targeted ACS NSQIP registry. The registry was queried for data from January 2014 to December 2019. All patients who underwent a pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) or distal pancreatectomy (DP) were selected using relevant current procedural terminology (CPT) codes (48140, 48150, 48152, 48153, 48154) and stratified based on whether the hospital was participating in the pancreas-targeted (“pancreas-targeted”) or non-targeted (“standard”) registry. The ACS-NSQIP does not collect data on patients younger than 18 years, transplant or trauma patients, and those undergoing hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. The study was reviewed and determined “Not Human Subjects Research” by the institutional review board at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Data Sources

The ACS-NSQIP facilitates quality improvement by providing participating hospitals with risk-adjusted data and participation has been shown to reduce adverse outcomes over time.4 Trained surgical clinical reviewers collect the data which are regularly audited to ensure reliability.8 The ACS-NSQIP registry includes 135 preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables. The pancreas-targeted registry was launched in 2014 and includes additional preoperative (biliary stent, recent chemotherapy/radiation), intraoperative (preoperative antibiotics, use of wound protector, pancreatic duct size, pancreatic gland texture, vascular resection, drain use), and postoperative variables (drain amylase and removal, pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, percutaneous drainage, intensive care unit stay, margin status, tumor histology and tumor staging) specifically relevant to pancreas surgery.9 The majority of procedure-targeted hospitals also participate in a virtual HPB (hepato-pancreato-biliary) Collaborative which provides additional semi-annual comparative reports.10

Covariates

The covariates included all variables captured in the standard ACS-NSQIP registry including data on patient demographics, comorbidities, disease characteristics, preoperative bloodwork, operative variables, and postoperative outcomes.11 Pancreas-specific variables captured in the pancreas-targeted registry were only analyzed for descriptive purposes. Variables were not further analyzed if their incidence was <1% in the population.

Outcomes

The main outcomes of this study were 30-day mortality and serious morbidity. Secondary outcomes included overall morbidity, any infectious complication, failure-to-rescue, and optimal surgery. Serious morbidity was defined as the occurrence of organ space surgical site infection (SSI), wound dehiscence, pulmonary embolism, ventilator dependency greater than 48 hours after surgery, renal failure, stroke, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, sepsis/septic shock, and return to the operating room.12,13 Optimal surgery was defined as avoidance of postoperative mortality, serious morbidity, reoperation, with a postoperative length of stay <75th percentile and no readmission.14 Overall morbidity was defined as any postoperative complication captured in the ACS-NSQIP including superficial SSI, urinary tract infection, and deep vein thrombosis. Any infection was defined as any surgical site infection (superficial, deep, or organ-space), pneumonia, urinary tract infection, sepsis, or septic shock. Failure-to-rescue was defined as death after occurrence of serious morbidity.15,16

Statistical Analysis

Standard univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed. Totals and percentages were used to present categorical data. Continuous data were presented as a median with interquartile range (IQR). Comparisons were made using the Pearson χ2 test for discrete variables and the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Due to the relatively large sample sizes, the standard mean difference (SMD) and odds ratio (OR) also were calculated to provide a measure for clinical significance; an SMD ≥0.1 was considered to indicate clinical significance.17 The analyses were performed in a complete case basis (cases with missing data were ignored).

First, univariate analyses were performed to compare the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables of patients in the pancreas-targeted versus the standard registry. Following this analysis, multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate differences among the two groups in the primary and secondary outcomes while adjusting for any differences in the preoperative and intraoperative characteristics. The initial regression models included all preoperative and intraoperative variables with incidence >1%. A stepwise backwards selection process was then used to eliminate covariates until the Akaike Information Criterion was minimized.18 The results of the multivariable analysis are presented as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. The analysis was performed using R software version 4.1.0 “Camp Pontanezen”.19

Missing Data

The analyses were performed in a complete case basis. Data were missing for operative approach in 23.2%, preoperative bilirubin in 10.1%, preoperative albumin in 11.2%, preoperative platelet count in 2.7%, preoperative partial thromboplastin time in 42.5%, and length of hospital stay in 1.1%. Less than 1% of data were missing for obesity, ASA class, operative time, and 30-day mortality.

RESULTS

Of 45,157 pancreatectomies performed between 2014 and 2019, 35,379 (78%) were done in targeted hospitals. The number of hospitals participating in the pancreatectomy procedure-targeted registry increased from 106 in 2014 to 165 in 2019. About two-thirds of the operations were pancreatoduodenectomies with a slightly higher rate in the targeted registry (68% versus 64% for the standard registry, p<0.05) and roughly a third were distal pancreatectomies (32% versus 36%). The median age of the patients was 65 years [IQR (interquartile range) 56 – 73] and half were female (50%). Three-quarters of the patients were white (74%). The two groups were well-balanced with regards to preoperative and intraoperative characteristics when the standard mean difference of ≥0.1 clinically significant factor was utilized (Table 1). Transfusions were required less often in pancreas-targeted hospitals (PD: 18.2% versus 21.7%, p<0.001 and DP: 11.2% versus 18.2%, p<0.001). Operative time was slightly longer in pancreas-targeted hospitals (PD: 5.9 versus 5.7 hours, p <0.001, DP: 3.5 versus 3.4 hours, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Preoperative and intraoperative characteristics

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | Distal pancreatectomy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Standard NSQIP (N=6,286) | Pancreas-Targeted NSQIP (N=24,071) | p-value | Standard NSQIP (N=3,492) | Pancreas-Targeted NSQIP (N=11,308) | p-value |

| Age (years); median (IQR) | 66 (58–73) | 66 (58–73) | 0.036 | 63 (52–71) | 63 (53–72) | 0.020 |

| Female sex | 3,419 (54%) | 12,877 (54%) | 0.210 | 1,560 (45%) | 5,035 (45%) | 0.894 |

| Race | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||||

| White | 4,631 (74%) | 17,934 (75%) | 2,513 (72) | 8,344 (74) | ||

| Other | 717 (11%) | 3,090 (13%) | 400 (12%) | 1,353 (12%) | ||

| Missing | 938 (15%) | 3,047 (13%) | 579 (17%) | 1,611 (14%) | ||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | 1,797 (29%) | 6,458 (27%) | 0.005 | 1,301 (38%) | 4,169 (37%) | 0.582 |

| BMI; median (IQR) | 26.8 (24–31) | 26.6 (23–30) | 0.004 | 28 (24–33) | 28 (24–32) | 0.287 |

| Smoking | 1,181 (19%) | 4,216(18%) | 0.020 | 635 (18%) | 1,825 (16%) | 0.005 |

| History of COPD | 276 (4%) | 998 (4%) | 0.409 | 147 (4%) | 455 (4%) | 0.662 |

| Dyspnea | 330 (5%) | 1,231 (5%) | 0.688 | 226 (7%) | 645 (6%) | 0.100 |

| Hypertension | 3,481 (55%) | 12,735 (53%) | <0.001 | 1,779 (51%) | 5,813 (51%) | 0.648 |

| Diabetes | 1,762 (28%) | 6,357 (26%) | 0.010 | 909 (26%) | 2,774 (25%) | 0.077 |

| Disseminated cancer * | 526 (8%) | 1,013 (4%) | <0.001* | 450 (13%) | 803 (7%) | <0.001* |

| History of chronic steroids | 194 (3%) | 652 (3%) | 0.115 | 131 (4%) | 425 (4%) | 1.000 |

| Weight loss (>10% in last 6 months) | 846 (14%) | 3,600 (15%) | 0.003 | 228 (7%) | 681 (6%) | 0.294 |

| Preoperative sepsis | 141 (2%) | 261 (1%) | <0.001 | 90 (3%) | 129 (1%) | <0.001* |

| ASA class | 0.253 | 0.84 | ||||

| 1 | 1,289 (21%) | 5,167 (22%) | 1,034 (30%) | 3,406 (30%) | ||

| 2–3 | 4,530 (72%) | 17,185 (71%) | 2,277 (65%) | 7,323 (65%) | ||

| 4–5 | 457 (7%) | 1,702 (7%) | 178 (5%) | 567 (5%) | ||

| Hematocrit <40% | 2,211 (36%) | 8,274 (35%) | 0.187 | 1,563 (46%) | 5,488 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin <3 g/dL | 1,228 (11%) | 3,984 (10%) | 0.001 | 800 (7%) | 2,123 (3%) | <0.001* |

| Bleeding requiring transfusion | 1,363 (21.7%) | 4,380 (18.2%) | <0.001 | 635 (18.2%) | 1,265 (11.2%) | <0.001* |

| Operative time (minutes); median (IQR) | 342 (262–441) | 359 (282–447) | <0.001 | 203 (147–280) | 212 (157–283) | <0.001 |

Bleeding requiring transfusion is captured from the surgery start time up to 72 hours after.

Abbreviations: NSQIP: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, IQR: Interquartile range, BMI: Body Mass Index, COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists

Standardized mean difference ≥0.1

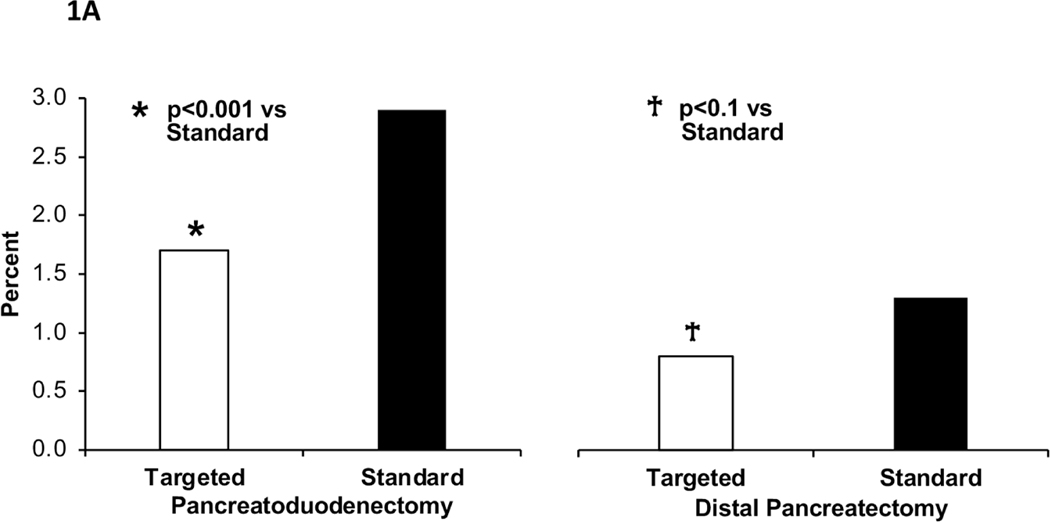

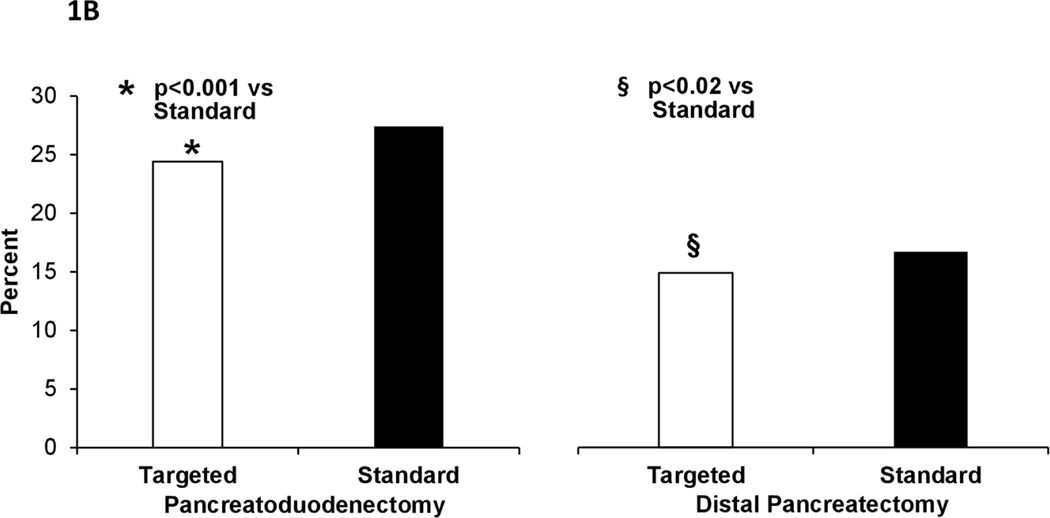

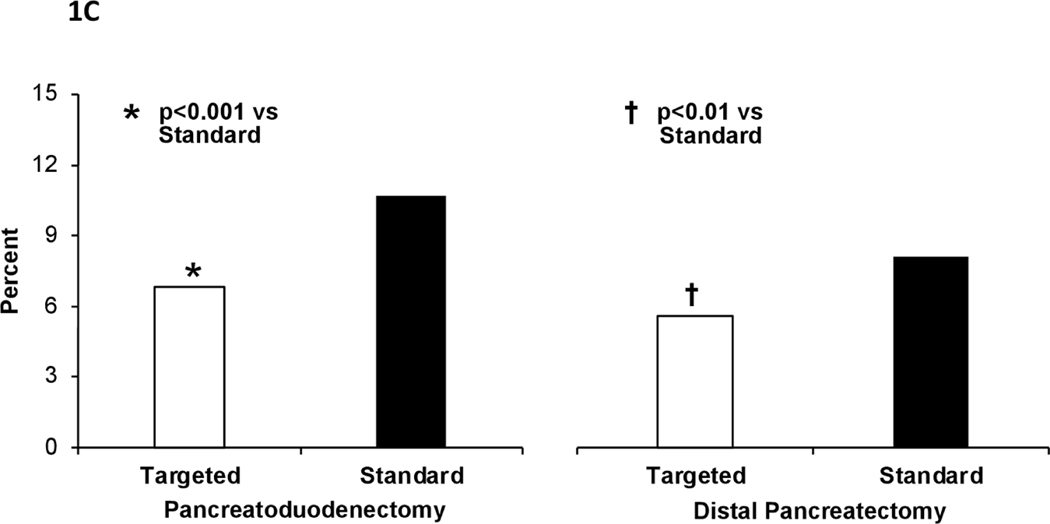

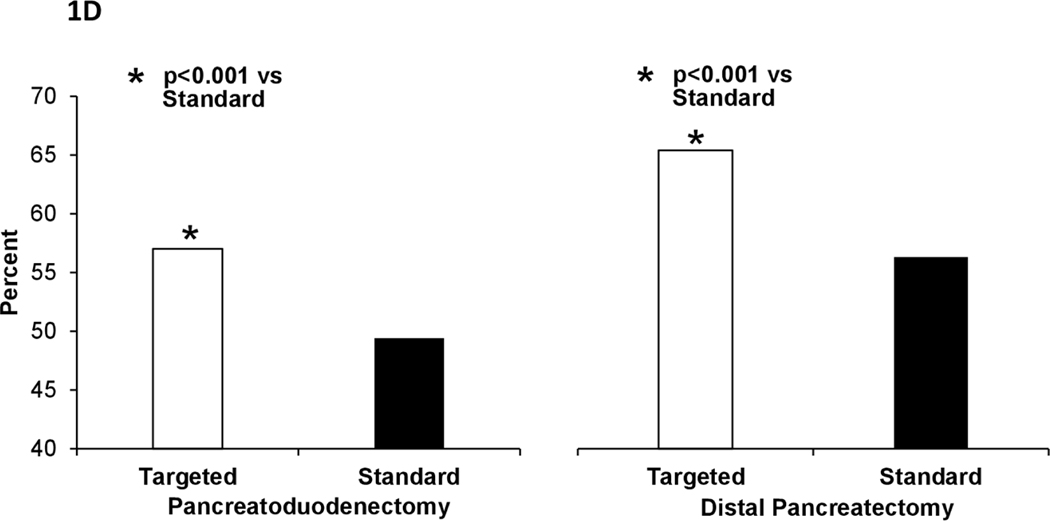

Univariate analysis of postoperative clinical outcomes is presented in Table 2. Unadjusted risk for 30-day mortality was lower in pancreas-targeted hospitals for both pancreatoduodenectomies (1.7% versus 2.9%, p<0.001) and distal pancreatectomies (0.8% versus 1.3%, p=0.008) (Figure 1A). Risk for postoperative complications also was lower in pancreas-targeted hospitals, including serious morbidity (PD: 24.4 % versus 27.4%, p<0.001; DP: 14.9% versus 16.7%, p=0.017) (Figure 1B), overall morbidity (PD: 44.5% versus 48.6%, p<0.001; DP: 28.2% versus 36.0%, p<0.001), and any infectious complication (PD: 30.3% versus 33.2%, p<0.001; DP: 17.7% versus 20.6%, p<0.001). Failure-to-rescue was higher in standard hospitals for pancreatoduodenectomies (10.7% versus 6.8%, p<0.001) and distal pancreatectomies (8.1% versus 5.6%, p=0.004) (Figure 1C). Optimal surgery was achieved more often in procedure-targeted hospitals (PD: 57.0% versus 49.4%, p<0.001 and DP: 65.4% versus 56.3%, p<0.001) (Figure 1D).

Table 2.

Postoperative outcomes by univariate analysis

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | Distal Pancreatectomy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Standard NSQIP (N=6,286) | Pancreas-Targeted NSQIP (N=24,071) | p-value | Standard NSQIP (N=3,492) | Pancreas- Targeted NSQIP (N=11,308) | p-value |

| 30-day mortality | 184 (2.9%) | 400 (1.7%) | <0.001 | 47 (1.3%) | 94 (0.8%) | 0.008 |

| Serious morbidity | 1,720 (27.4%) | 5,871 (24.4%) | <0.001 | 578 (16.7%) | 1,681 (14.9%) | 0.017 |

| Failure-to-rescue ± | 184 (10.7%) | 400 (6.8%) | <0.001 | 47 (8.1%) | 94 (5.6%) | 0.004 |

| Overall morbidity | 3,057 (48.6%) | 10,716 (44.5%) | <0.001 | 1,257 (36.0%) | 3,189 (28.2%) | <0.001* |

| Any infection | 2,084 (33.2%) | 7,282 (30.3%) | <0.001 | 721 (20.6%) | 1,996 (17.7%) | <0.001 |

| Superficial SSI | 420 (6.7%) | 1,892 (7.9%) | 0.002 | 111 (3.2%) | 280 (2.5%) | 0.028 |

| Deep SSI | 143 (2.3%) | 325 (1.4%) | <0.001 | 29 (0.8%) | 62 (0.5%) | 0.082 |

| Organ-space SSI | 1,036 (16.5%) | 3,868 (16.1%) | 0.441 | 374 (10.7%) | 1,190 (10.5%) | 0.778 |

| Sepsis/shock | 939 (14.9%) | 2,941 (12.2%) | <0.001 | 206 (5.9%) | 597 (5.3%) | 0.171 |

| Dehiscence | 105 (1.7%) | 311 (1.3%) | 0.025 | 27 (0.8%) | 31 (0.3%) | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 349 (5.6%) | 898 (3.7%) | <0.001 | 162 (4.6%) | 318 (2.8%) | <0.001 |

| Reintubation | 306 (4.9%) | 862 (3.6%) | <0.001 | 72 (2.1%) | 184 (1.6%) | 0.099 |

| Failure to wean ventilator | 241 (3.8%) | 681 (2.8%) | <0.001 | 59 (1.7%) | 160 (1.4%) | 0.274 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 230 (3.7%) | 921 (3.8%) | 0.561 | 108 (3.1%) | 325 (2.9%) | 0.540 |

| Unplanned return to OR | 431 (6.9%) | 1,329 (5.5%) | <0.001 | 145 (4.2%) | 340 (3.0%) | 0.001 |

| Postop LOS (days); median (IQR) | 9.0 (7.0–14.0) | 8.0 (6.0–12.0) | <0.001 | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | <0.001 |

| Unplanned readmission | 1,080 (17.2%) | 4,085 (17.0%) | 0.707 | 561 (16.1%) | 1,839 (16.3%) | 0.802 |

| Optimal surgery | 3,129 (49.9%) | 13,706 (57.0%) | <0.001* | 1,964 (56.3%) | 7,391 (65.4%) | <0.001* |

Abbreviations: NSQIP: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, LOS: Length of Stay, IQR: Interquartile Range, SSI: Surgical Site Infection, OR: Operating Room.

Standardized mean difference >0.1

The denominator for this variable is the number of patients experiencing a serious complication (PD: N= 1,720 for standard NSQIP and 5,871 for pancreas-targeted NSQIP, DP: N= 578 for standard NSQIP and 1,681 for pancreas-targeted NSQIP)

Figure 1A –

30-day mortality for pancreatoduodenectomy (left) and distal pancreatectomy (right) in procedure-targeted and standard hospitals

Figure 1B –

Serious morbidity for pancreatoduodenectomy (left) and distal pancreatectomy (right) in procedure-targeted and standard hospitals

Figure 1C –

Failure-to-rescue for pancreatoduodenectomy (left) and distal pancreatectomy (right) in procedure-targeted and standard hospitals

Figure 1D –

Optimal surgery for pancreatoduodenectomy (left) and distal pancreatectomy (right) in procedure-targeted and standard hospitals

* - p<0.001 vs standard

† p<0.01 vs Standard

Patients undergoing pancreatectomy in hospitals participating in the pancreas-targeted ACS NSQIP registry had significantly lower risked-adjusted morbidity, mortality, and failure to rescue compared to hospitals participating in the standard ACS NSQIP registry. The importance of this finding is that hospitals who self-selected to invest on targeted registry participation had better outcomes and benchmarking against the pancreas-targeted ACS NSQIP registry outcomes should be done with caution.

On multivariable analysis (Table 3), pancreatoduodenectomies in pancreas-targeted hospitals were associated with lower 30-day mortality [OR 0.61 (95% CI 0.50–0.75)], serious morbidity [OR 0.83 (0.77–0.89)], failure-to-rescue [OR 0.59 (0.47–0.74)], overall morbidity [OR 0.83 (0.78–0.89)], and any infectious complication [OR 0.83 (0.78–0.89)]. For distal pancreatectomies, no significant difference was observed in 30-day mortality [OR 0.83 (0.50–1.39)], serious morbidity [OR 1.03 (0.90–1.18)], or failure-to-rescue [OR 0.89 (0.52–1.50)]; however, targeted hospitals were associated with lower overall morbidity [OR 0.75 (0.68–0.83)] and infectious complications [OR 0.85 (0.76–0.95]. Participation in the targeted registry also was associated with higher rates of optimal surgery for both pancreatoduodenectomies [OR 1.33 (1.25–1.41)] and distal pancreatectomies [OR 1.17 (1.06–1.30)].

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of the risk-adjusted effect of hospital participation to pancreas-targeted ACS-NSQIP on postoperative clinical outcomes

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | Distal Pancreatectomy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Outcome | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | p-value |

| 30-day mortality | 0.61 | 0.50 – 0.75 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.50 – 1.39 | 0.49 |

| Serious morbidity | 0.83 | 0.77 – 0.89 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 0.90 – 1.18 | 0.65 |

| Failure-to-rescue | 0.59 | 0.47 – 0.74 | <0.001 | 0.89 | 0.52 – 1.50 | 0.65 |

| Overall morbidity | 0.83 | 0.78 – 0.89 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.68 – 0.83 | <0.001 |

| Any infectious complication | 0.83 | 0.78 – 0.89 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.76 – 0.95 | 0.003 |

| Optimal surgery | 1.33 | 1.25 – 1.41 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.06 – 1.30 | 0.002 |

The initial regression models included all pre-operative and intraoperative variables with incidence >1%. A stepwise backwards selection process was then used to eliminate covariates until the Akaike Information Criterion was minimized.

Abbreviations: ACS-NSQIP: American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

DISCUSSION

This analysis suggests that among hospitals participating in the ACS-NSQIP, those participating in the pancreas-targeted registry were associated with significantly lower risk for mortality and serious morbidity. Specifically for pancreatoduodenectomy, failure-to-rescue and other complications also were less prevalent in targeted hospitals. No clinically significant differences (SMD >0.1) were observed in the characteristics of the patients treated in pancreas-targeted versus standard hospitals. For both pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy, optimal surgery was achieved more often in procedure-targeted hospitals.

We hypothesized that hospitals opting in the pancreas-targeted registry are likely higher-volume hospitals and may treat more complicated patients with potentially higher perioperative risk. However, while a number of statistically significant differences were noted with very large sample sizes, we found no clinically significant differences in the rates of comorbidities between the compared groups. While the data cannot completely capture the full extent of a patient’s health status and perioperative risk, our findings suggest that any selection bias in this regard is likely not clinically significant. Of note, at procedure-targeted hospitals, operative times were longer but fewer perioperative transfusions were required. These perioperative parameters have been correlated with better operative outcomes.20

The procedure-targeted dataset captures all of the variables found in the standard NSQIP as well as procedure-specific variables. Participation rates vary by year, but in 2019, 719 hospitals participated in the standard ACS-NSQIP, and 165 hospitals chose the pancreas-targeted registry.21 Of note, based on this analysis, targeted hospitals account for a quarter of the overall hospitals but perform over three quarter of pancreatectomies in the ACS-NSQIP registry, indicating that most of them are higher-volume centers. Analysis of the listed procedure-targeted hospitals suggests that the vast majority are academic medical centers, and many are known for performing high volumes of pancreatic surgery.

While the current study noted a difference in outcomes between targeted and standard hospitals for both PD and DP, this finding was not the case in a similar study examining abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs in terms of patient characteristics or clinical outcomes.5 These results, interpreted within the context of the present findings, suggest the level of applicability may vary between the standard NSQIP and the different procedure-targeted registries and may warrant further research.

The term “optimal” surgery is increasingly used to evaluate quality of care and has been used in relation to a wide variety of surgical specialties in the literature.22–24 As a composite variable, typically a higher number of events are observed, which allows for favorable power calculations. Specialty centers have been shown to have higher rates of “optimal outcome” or “Textbook Outcome” for adult congenital surgery, mitral valve repair, hepatic procedures, and recently pancreatecomies.22,23,25–27 Optimal pancreatic surgery outcome can be defined with variables found in the pancreas-targeted ACS-NSQIP registry and is an all-or-none measurement. Beane et al reported the rates of optimal pancreatoduodenectomies and distal pancreatectomies in North America to be 50–60% (improved by 3–5% between 2013 and 2017), which is comparable to this study’s results of 50–65%.14 The novel observation of the current analysis is that procedure-targeted hospitals were more likely to achieve optimal pancreatic surgery by an order of 33% for PD and 17% for DP.

Hospitals participating in the pancreas-targeted registry had a 16% decrease in serious complications with an almost two-fold decrease in mortality rate. Considering the groups were relatively well-balanced clinically with regards to preoperative characteristics, this mismatch between complications and mortality rates may be attributed to significant failure-to-rescue at standard hospitals. Failure-to-rescue is the inability to prevent death once postoperative complications have occurred.16,28 Factors that affect failure-to-rescue are largely related to the institution and the presence of specialty teams and can be divided into two categories: early detection of postoperative complications and adequate management of them as they arise.

Failure-to-rescue may be affected by nursing and ancillary support training and staffing ratios, 24/7 subspecialty service coverage (i.e. interventional radiology), as well as hospital size, surgeon experience, hospital technology, and more.16,29 In a transatlantic analysis, Gleeson et al reported that management of complications by Interventional Radiology improved failure-to-rescue compared to reoperation.29 El Amrani et al also reported that failure-to-rescue was over two-fold if the patient was transferred to a different hospital after pancreatectomy, and over three-fold if the transferring facility was a low volume center.30 Moreover, several studies have suggested that high hospital volume and centralization are associated with decreased mortality and failure-to-rescue after pancreatic surgeries.31–34 Considering the impact failure-to-rescue has on mortality rates, some have argued that rescue is a better focus for quality improvement and mortality reduction than complication rates alone.35,36

The current findings should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. First, this study is retrospective and suffers the inherent limitations of this design, including potential for selection bias, confounding, recollection bias, and misclassification.8 Still, the ACS-NSQIP data are prospectively collected, and the data extraction is standardized and has been previously validated.9 Furthermore, the extracted data may not accurately capture the complete health status of patients, and potential exists for unmeasured bias in risk stratification.37 Specifically for pancreas surgery, many clinically significant variables, such as preoperative stent, preoperative chemotherapy/radiation, cancer histology, pancreatic texture, and postoperative fistulas or delayed gastric emptying are only captured in the targeted registry and were therefore not amenable for analysis for this study. The variability in hospital participation in the targeted registry year by year also could create some confounding in the interpretation of the results. However, a steady growth in the number of procedure-targeted hospitals has been observed over time. Last, patients are only followed for 30 days postoperatively and evidence exists that patients undergoing major operations such as hepatectomies may suffer significant morbidity and mortality up to 90 days postoperatively.38 Nevertheless, both standard and procedure-targeted patients were monitored for 30 days.

CONCLUSION

Hospitals participating in the pancreas-targeted registry had almost half the mortality rate after pancreatoduodenectomy, even after risk adjustment. Patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) at procedure-targeted hospitals also experienced less serious and overall morbidity (17%) and failure-to-rescue (41%). This systemic decrease in morbidity, mortality, and failure-to-rescue following PD should be considered in future research utilizing these registries. Optimal outcomes were achieved more commonly at procedure-targeted hospitals for both PD (33%) and distal pancreatectomy (17%). In addition, use of the ACS-NSQIP for pancreatectomy-related clinical outcome benchmarking should be done with caution, noting the above differences. Further research is warranted to delineate the mechanisms underlying this relationship and inform targets for quality improvement.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1 TR003107. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- ACS-NSQIP

American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

- OR

odds ratio

- CPT

current procedural terminology

- SMD

standardized mean difference

- IQR

interquartile range

- CI

confidence interval

- AAA

abdominal aortic aneurysms

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURE

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henderson WG, Daley J. Design and statistical methodology of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: why is it what it is? Am J Surg. Nov 2009;198(5 Suppl):S19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko CY, Hall BL, Hart AJ, Cohen ME, Hoyt DB. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: achieving better and safer surgery. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. May 2015;41(5):199–204. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(15)41026-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newhook TE, LaPar DJ, Lindberg JM, Bauer TW, Adams RB, Zaydfudim VM. Morbidity and mortality of pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign and premalignant pancreatic neoplasms. J Gastrointest Surg. Jun 2015;19(6):1072–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2799-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen ME, Liu Y, Ko CY, Hall BL. Improved Surgical Outcomes for ACS NSQIP Hospitals Over Time: Evaluation of Hospital Cohorts With up to 8 Years of Participation. Ann Surg. Feb 2016;263(2):267–73. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soden PA, Zettervall SL, Ultee KH, et al. Patient selection and perioperative outcomes are similar between targeted and nontargeted hospitals (in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program) for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. Feb 2017;65(2):362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.04.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Program ACoS-NSQI. ACS-NSQIP: Participation Options. Accessed June 11, 2022, https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/244702/NSQIP-Participation-Options.pdf

- 7.Johnston LE, Robinson WP, Tracci MC, et al. Vascular Quality Initiative and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program registries capture different populations and outcomes in open infrainguinal bypass. J Vasc Surg. Sep 2016;64(3):629–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.03.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiloach M, Frencher SK, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. Jan 2010;210(1):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.User Guide for the 2021 ACS NSQIP Procedure Targeted Participant Use Data File (PUF). American College of Surgeons. Accessed May 28 2023, https://www.facs.org/media/cyaaq1yl/pt_nsqip_puf_userguide_2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitt HA, Kilbane M, Strasberg SM, et al. ACS-NSQIP has the potential to create an HPB-NSQIP option. HPB (Oxford). Aug 2009;11(5):405–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00074.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Accessed July 15, 2021, [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mavros MN, Coburn NG, Davis LE, Zuk V, Hallet J. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with elevated INR undergoing hepatectomy: an analysis of the American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program registry. HPB (Oxford). July 2021;23(7):1008–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2020.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilimoria KY, Chung JW, Hedges LV, et al. National Cluster-Randomized Trial of Duty-Hour Flexibility in Surgical Training. N Engl J Med. Feb 25 2016;374(8):713–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beane JD, Borrebach JD, Zureikat AH, Kilbane EM, Thompson VM, Pitt HA. Optimal Pancreatic Surgery: Are We Making Progress in North America? Ann Surg. 10 01 2021;274(4):e355–e363. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. Oct 01 2009;361(14):1368–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleeson EM, Pitt HA, Mackay TM, et al. Failure to Rescue After Pancreatoduodenectomy: A Transatlantic Analysis. Ann Surg. September 01 2021;274(3):459–466. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC. Using the Standardized Difference to Compare the Prevalence of a Binary Variable Between Two Groups in Observational Research. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation. 2009/05/14 2009;38(6):1228–1234. doi: 10.1080/03610910902859574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Portet S A primer on model selection using the Akaike Information Criterion. Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:111–128. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ball CG, Pitt HA, Kilbane ME, Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Lillemoe KD. Peri-operative blood transfusion and operative time are quality indicators for pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). Sep 2010;12(7):465–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00209.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ACS NSQIP Participant Use Data File. American College of Surgeons. Accessed September 25, 2022, https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/data-and-registries/acsnsqip/participant-use-data-file/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beane JD, Hyer M, Mehta R, et al. Optimal hepatic surgery: Are we making progress in North America? Surgery. December 2021;170(6):1741–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2021.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saydy N, Moubayed SP, Bussières M, et al. What is the optimal outcome after endoscopic sinus surgery in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis? A consultation of Canadian experts. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jun 16 2021;50(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s40463-021-00519-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meara JG, Hughes CD, Sanchez K, Catallozzi L, Clark R, Kummer AW. Optimal Outcomes Reporting (OOR): A New Value-Based Metric for Outcome Reporting Following Cleft Palate Repair. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. January 2021;58(1):19–24. doi: 10.1177/1055665620931708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vouhé PR. Adult congenital surgery: current management. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;23(3):209–15. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badhwar V, Vemulapalli S, Mack MA, et al. Volume-Outcome Association of Mitral Valve Surgery in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 10 January 2020;5(10):1092–1101. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyer JM, Diaz A, Pawlik TM. The win ratio: A novel approach to define and analyze postoperative composite outcomes to reflect patient and clinician priorities. Surgery. Aug 26 2022;doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2022.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silber JH, Romano PS, Rosen AK, Wang Y, Even-Shoshan O, Volpp KG. Failure-to-rescue: comparing definitions to measure quality of care. Med Care. Oct 2007;45(10):918–25. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31812e01cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghaferi AA, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital characteristics associated with failure to rescue from complications after pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. Sep 2010;211(3):325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Amrani M, Lenne X, Clément G, et al. Referring Patients to Expert Centers After Pancreatectomy Is Too Late to Improve Outcome. Inter-hospital Transfer Analysis in Nationwide Study of 19,938 Patients. Ann Surg. November 2020;272(5):723–730. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Amrani M, Clement G, Lenne X, et al. Failure-to-rescue in Patients Undergoing Pancreatectomy: Is Hospital Volume a Standard for Quality Improvement Programs? Nationwide Analysis of 12,333 Patients. Ann Surg. November 2018;268(5):799–807. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lequeu JB, Cottenet J, Facy O, Perrin T, Bernard A, Quantin C. Failure to rescue in patients with distal pancreatectomy: a nationwide analysis of 10,632 patients. HPB (Oxford). September 2021;23(9):1410–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amini N, Spolverato G, Kim Y, Pawlik TM. Trends in Hospital Volume and Failure to Rescue for Pancreatic Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. Sep 2015;19(9):1581–92. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2800-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamirisa NP, Parmar AD, Vargas GM, et al. Relative Contributions of Complications and Failure to Rescue on Mortality in Older Patients Undergoing Pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. Feb 2016;263(2):385–91. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varley PR, Geller DA, Tsung A. Factors influencing failure to rescue after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a National Surgical Quality Improvement Project Perspective. J Surg Res. June 15 2017;214:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheetz KH, Waits SA, Krell RW, Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ, Ghaferi AA. Improving mortality following emergent surgery in older patients requires focus on complication rescue. Ann Surg. Oct 2013;258(4):614–7; discussion 617–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a5021d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyman WB, Passeri M, Cochran A, et al. Discrepancy in Postoperative Outcomes between Auditing Databases: A NSQIP Comparison. Am Surg. Aug 01 2018;84(8):1294–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayo SC, Shore AD, Nathan H, et al. Refining the definition of perioperative mortality following hepatectomy using death within 90 days as the standard criterion. HPB (Oxford). Jul 2011;13(7):473–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00326.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]