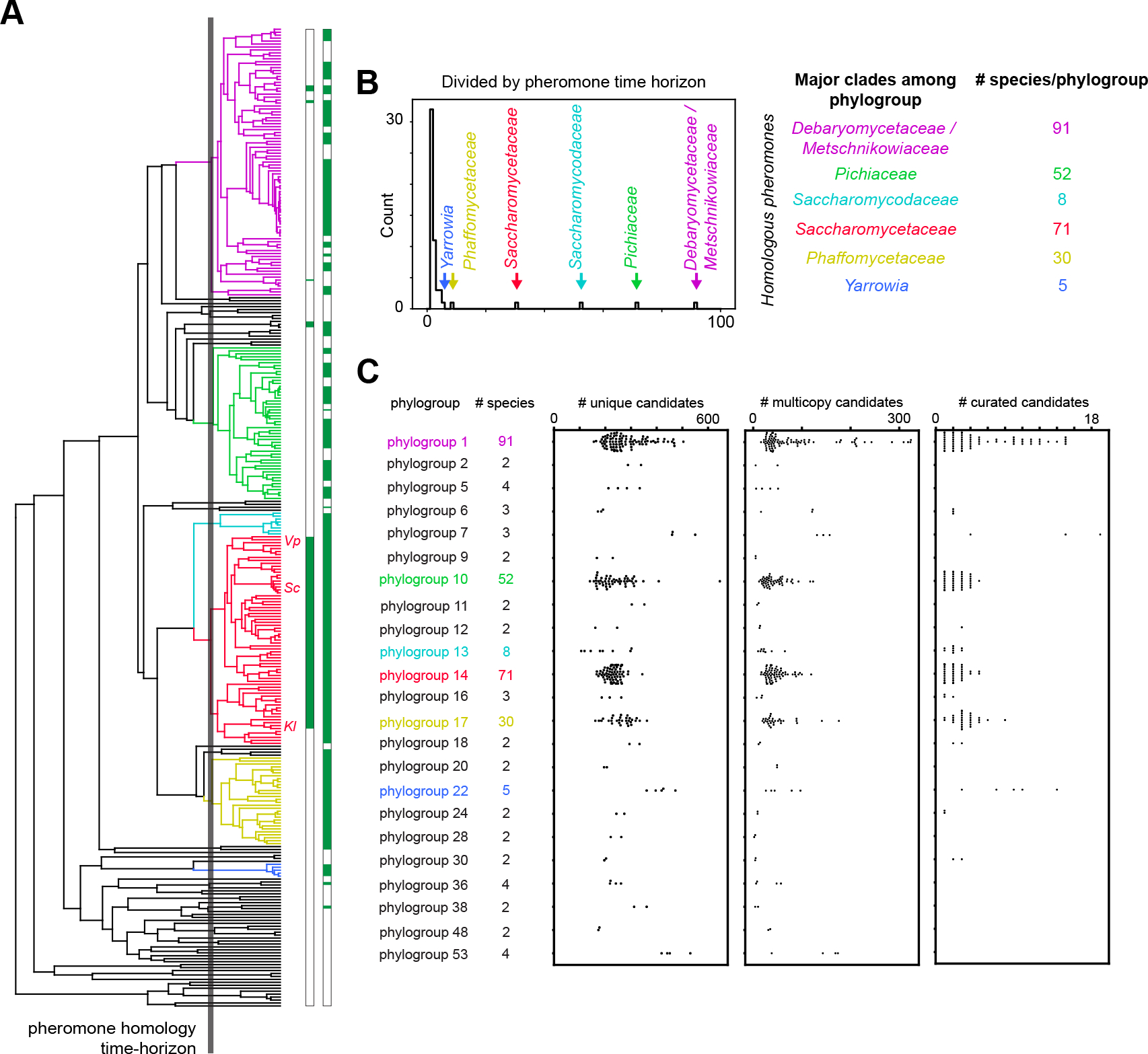

Figure 3. Fungal pheromones are conserved within closely related species and are often encoded in multiple copies in a genome.

(A) Phylogenetic tree describing the evolutionary relationship of 332 yeasts with two horizons indicated. The solid grey line indicates the assumed maximum evolutionary distance at which mature pheromone sequences show detectable sequence homology, operationally defined by the divergence time of S. cerevisiae (Sc) and Kluveromyces lactis (Kl), whose pheromones show detectable sequence homology. The leaves corresponding to Sc, Kl and Vanderwaltozyma polyspora (Vp) are indicated on the tree. The leaves of the tree are also annotated in green for species with known pheromones prior to our work (first column) and species with pheromones identified in our work (second column). (B) Based on the pheromone homology time horizon (solid grey line in A), we separated 332 yeast genomes into 23 phylogroups of at least 2 species; there are also 32 singleton species. The most populated phylogroups correspond to the listed well-known clades where closely related species have been densely sequenced. These clades are represented in the tree by the corresponding colors. (C) Number of pheromone candidates per species plotted for each of the 23 conserved-pheromone phylogroups, where each circle corresponds to the number of candidates in a species, and each copy of a group of closely homologous sequences within a genome is counted separately. Selecting for candidates that have at least two homologous copies within the clade reduces the number of viable candidates per genome to 10–300 (center panel compared to left). Manual curation of candidates similar to known pheromones identifies the most likely pheromone(s) in each genome (right panel) for experimental validation. The curated candidates include both multiple copies of a single best candidate and multiple distinct candidates if a single best pheromone cannot be uniquely identified. There are 1–19 candidates encoded in each species for experimental testing. Some phylogroups contain too few species and thus no candidates rose above the rest through curation. See also Figure S3, S6, S7.