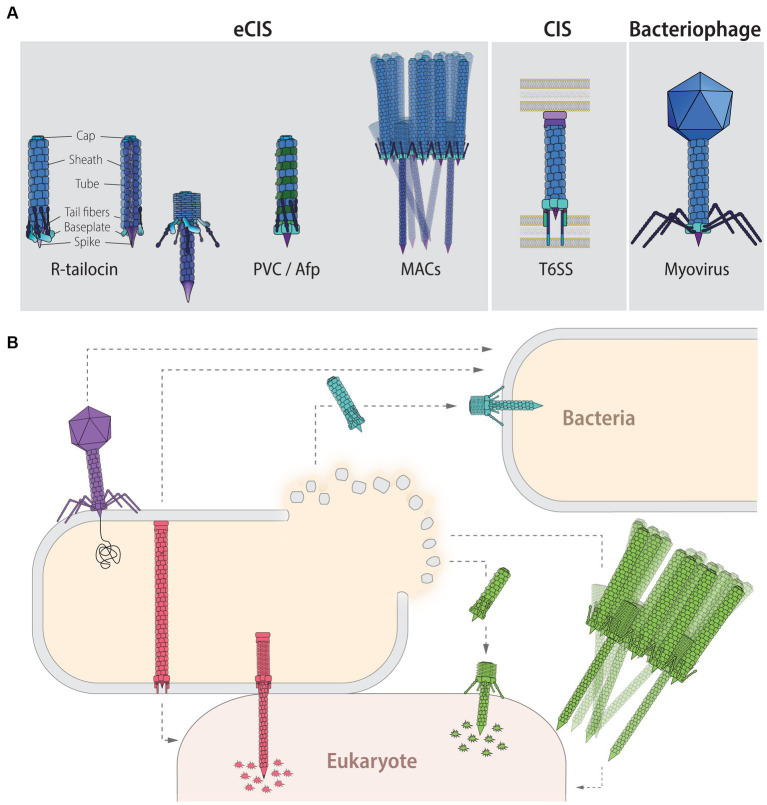

Figure 1.

Contractile injection systems (CISs): classification, targets and function. (A) CISs are thought to be evolved from the contractile tail of Myoviridae phages and can be classified into two main groups: extracellular CISs (eCISs) and cell wall-anchored type VI secretion systems (T6SSs). Extracellular CISs encompass R-tailocins (left, extended state; right contracted state; colors indicate the different building blocks) as well as various phage tail-like structures such as the Photorhabdus virulence cassettes (PVCs), the antifeeding prophages (Afps), and the metamorphosis-inducing contractile structures (MACs). Sizes of eCISs range between 80 and 180 nm, for R-tailocins, Afps and PVCs, while MACs form larger arrays which have been reported to range up to 920 nm, formed out of individual components of about 310 nm. (B) Phages (purple) directly interact with a host bacterial cell by injecting their genetic content. T6SSs (red) are assembled in the producing cell and upon contact with a target cell, either bacterial or eukaryotic, the device contracts and injects toxic effectors into the prokaryotic or eukaryotic prey. Extracellular CISs are released upon lysis of the producing cell. R-tailocins (light blue) have only been found to target other bacteria by puncturing and destabilizing their membrane without injecting effectors, while protein-translocating eCISs like PVCs, Afps and MACs (green) target eukaryotic cells by injecting eCIS-associated toxins (EATs). For MACs, only part of the star-shaped structure formed by the assembly of a large number of eCISs is shown.