Abstract

This paper focuses on “alternative methods for initial broiler processing” and exploration of alternative processing including slaughter at the farm immediately after catching. On-farm slaughter and transport (FSaT) is envisioned as a mobile unit that stuns, slaughters, and shackles the broiler carcasses at the farm. A separate trailer-unit then transports the shackled broiler carcasses to the processing plant. Once at the processing plant carcasses are mechanically transferred into plant shackle lines and moved into processing. The hypothesis is that the FSaT approach will dramatically improve overall bird welfare and well-being by reducing live handling and eliminating live transport from the farm to the processing plant. In addition, ancillary impacts could include: improving yield efficiencies by eliminating dead on arrivals, potentially reducing water and energy consumption, reducing labor requirements at the processing plant with the elimination of live rehang, and offering an economically sustainable alternative. The FSaT approach represents a radical change from traditional processing, and its effects on poultry processing need to be evaluated. This paper presents results of experiments conducted at a commercial poultry processor to evaluate feather picking efficiency, carcass bacteriological loading, and meat quality for delayed processed carcasses.

Key words: poultry transport welfare, delayed processing, defeathering, carcass microbiology, meat quality

INTRODUCTION

Under the current system, stressors such as physical discomfort, abnormal social settings, novel physical surroundings, crowded containers, the presence of humans, extreme weather conditions, high and low temperatures, and other factors (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2016) are all associated with live animal transport. The documented negative effects of live catching and transport on broiler welfare include heat and environmental stressors (Mitchell and Kettlewell, 1998), bruising and other damage (Jacobs et al., 2017), effects of holding broiler chickens in their transport containers (Warriss et al., 1999), and broilers dead on arrival (DOA) at the processing plant. These preslaughter stages have been identified as persistent critical phases of the production process in regard to need for improving animal welfare (Schwartzkopf-Gensweina et al., 2012). In traditional U.S. processing systems using electrical stunning, birds are handled alive twice, once at the farm during catching and crating and once at the processing facility during shackling, which compounds distress (Sparrey and Kettlewell, 1994; Bedanova et al., 2007; Lines et al., 2012). These welfare issues are endemic to the current process and are not easily alleviated through incremental equipment innovation. It is unlikely that by modifying the current systems we will be able to substantially improve future broiler well-being.

Current solutions to bird welfare concerns during transport are a patchwork of incremental improvements that simply address the symptoms and not the root causes. This paper describes an innovative strategy for slaughter (preprocessing) broilers on the farm before transport. This approach called on-farm slaughter and transport (FSaT) eliminates live transport and thus will significantly improve overall bird welfare and well-being by eliminating the inherent stressors involved in live transport from the farm to the processing plant. It will also achieve additional positive impacts such as eliminating surface water runoff contamination at the processing plant bird-holding area and providing a safer animal/carcass transportation system. The FSaT approach represents a fundamental change from traditional processing, and its effects on poultry processing need to be evaluated. This paper presents results of experiments conducted at a commercial poultry processor to evaluate feather picking efficiency, bacteriological loading, and meat quality for delayed processed carcasses.

LIVE TRANSPORT OF POULTRY—IMPACTING THE WELFARE AND MEAT QUALITY OF BIRDS

K. Schwean-Lardner, karen.schwean@usask.ca, and T.G. Crowe, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Canada.

Transportation of commercial poultry to slaughter is complex. There are many factors that play a role in the level of distress that birds experience. For example, truck design differs among geographic/environmental conditions, ranging from naturally ventilated to mechanically/actively ventilated trucks with supplemental heat or cooling. Other features within naturally ventilated trucks include the porosity of side coverings and locations and sizes of openings to allow the management of airflow through the trailer, which affects the temperature and humidity experienced by broilers. Within mechanically ventilated trucks, the configuration of equipment and bird-holding containers also change airflow patterns. Birds can be exposed to temperature/relative humidity (TRH) combinations that can potentially result in hypo- or hyperthermia within the same load. Regardless of environmental conditions, birds are exposed to feed and water removal, which is a stressful event that increases over time and can lead to dehydration and hunger during transit and holding. Other potential stressors include changes in group structure, density and environment within the crates or modules, noise, or vibration while in transit, to name just a few. We also know that a bird's feather cover plays a significant role in its ability to cope with various TRH combinations (Beaulac et al., 2020; Frerichs et al., 2021, 2022).

Research at the University of Saskatchewan has focused on some of these components, in particular TRH combinations and trip duration, for both cold and hot conditions, which if not managed properly, can have detrimental effects on bird welfare. This section will focus primarily on the impacts of cold and hot TRH combinations at crate/module levels during transport of poultry.

Behavioral Coping Responses During Potential Thermal Stress

Regardless of bird type, behavior changes in an initial attempt to cope when birds are exposed to cold or hot/humid environments. In cold conditions, birds initially activate behavioral responses that include shivering, huddling, and ptiloerection (to trap air between the feathers and the skin), and birds become motionless in efforts to maintain body heat (Henrikson et al., 2018; Beaulac et al., 2020; Frerichs et al., 2022). Broilers will burrow under each other to maintain body heat (Strawford et al., 2011). The effects of cold conditions are compounded if feathers get wet (Hunter et al., 1999) as can occur during cold-weather transport.

In hot conditions, panting increases initially, and during small temperature/humidity increases, can be sufficient to lower body temperature. However, if it is too hot with high humidity, excessive panting is ineffective in controlling body temperature, and can lead to alkalosis, which reduces the effectiveness of essential physiological mechanisms in the body (Marder and Arad, 1989) and can lead to death. Other behavioral coping mechanisms include attempting to spatially isolate or spread wings, or as noted in turkeys, place the neck on a cool surface (Vermette et al., 2017; Henrikson et al., 2018). Eventually, prior to death, birds become immobile, likely due to energy depletion, particularly when transported for longer periods of time.

Meat Quality Impacts of Thermal Stress

When exposed to cold conditions and the birds cannot cope by behavioral mechanisms alone, the core body temperature starts to decline (Dadger et al., 2011). Eventually, this can contribute to death if body temperature reduction is severe. The cold exposure (below 0°C for 3–4 h; Dadger et al., 2010; −4°C and below; Dadger et al., 2012b) also increases muscle pH (30 h postmortem), which in turn has a negative effect on meat quality by decreasing water-holding capacity (Dadger et al., 2010) and altering the color of the breast muscle to a darker color in broilers (Dadger et al., 2010), turkeys (Vermette et al., 2017; Henrikson et al., 2018), and end-of-cycle laying hens (Beaulac et al., 2020; Frerichs et al., 2021). These traits are indicative of dark, firm, and dry meat (DFD), which results from the rapid depletion of muscle glycogen stores prior to death (Dadger et al., 2011, 2012a,b). Numerous factors can alter the prevalence of these specific meat quality issues, including feather cover (Frerichs et al., 2021), and bird body size/age (Dadger et al., 2011).

Hot and humid exposure during transport can result in other meat quality challenges. In these cases, muscle pH and water-holding capacity are reduced. Breast muscle becomes lighter in color (Dadger et al., 2010). These traits are indicative of pale, soft, and exudative (PSE) meat, which has a much lower value and is not preferred by customers. Body size/age/gender and feather cover also play a part in physiological responses to hot and humid conditions. For example, well-feathered end-of-lay hens have greater difficulty coping with 30°C conditions than do poorly feathered birds (Beaulac et al., 2020; Frerichs et al., 2021). Sixteen-wk-old toms are less able to handle these temperatures than are 12-wk-old turkey hens (Munson et al. unpublished), and similar data have been shown in broilers (Dadger et al., 2011).

To conclude, transport during hot/humid or cold conditions poses significant welfare and meat quality challenges. Proper trailer design and control of airflow are vital in managing the environment, but the challenges are complex.

OVERVIEW OF ON-FARM SLAUGHTER AND TRANSPORT IN THE FUTURE

Alex V. Samoylov, alexander.samoylov@gtri.gatech.edu, Wayne Daley, and Aklilu Giorges, Georgia Tech Research Institute, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

To address the aforementioned issues associated with live transport, we proposed an on-farm slaughter and transport (FSaT) concept. The goals of the FSaT system are to improve poultry well-being through reimagining transportation to decrease injuries and distress and to investigate preslaughter stunning approaches to further minimize pain and distress, which aligns with multiple priority areas of the Welfare and Well-being of Agricultural Animals Program. Traditionally, live broilers are transported to the processing facilities in modular coops, held, unloaded, shackled, and then stunned and killed. The FSaT system reimagines how the broilers are slaughtered and transported to the processing plant. It moves stunning and killing (bleeding) operations to the farm and transports carcasses as opposed to living broilers, which eliminates transport and reshackling of live broilers. A schematic representation of the current vs. proposed process can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

FSaT vs. traditional processing.

To achieve that vision, the FSaT system employs 2 mobile units: Processing Trailer and Transport Trailer placed on standard 53-foot trailers (Figure 2). The processing trailer is equipped with systems to receive birds from the broiler house, a stunning system, and a station for shackling. The transport trailer consists of guiding rails, electrical motors, and shackles arranged in a way that we can transport close to 4,300 broilers in 1 trip. The FSaT system concept utilizes mechanical harvesting to load broilers into drawers that are then transferred to the processing trailer that provides stunning and shackling stations. Subsequently, the stunned/shackled broilers are moved to the transport trailer where a neck cut procedure is performed. This transport trailer then hauls the bled carcasses to the processing facility. To make this process work, a mechanical system design that uses a mobile platform that can be easily moved between locations at the farm and between farms was created.

Figure 2.

On-farm slaughter concept.

Our hypothesis is that moving the slaughter function to the farm and transporting carcasses as opposed to live birds will significantly reduce and eliminate stressors such as bird handling, heat, cold, and other environmental exposure, and improve bird welfare and well-being compared to current industry practices. In order to explore this hypothesis, the on-farm stunning and transport effects on yield, processing efficiencies, and food safety and quality need to be evaluated.

Proposed changes represent a fundamental departure from the current well-established transport process. As such, the research teams at Georgia Tech Research Institute, the University of Georgia, Auburn University, and USDA-ARS are currently investigating the impacts of FSaT processing on carcass defeathering quality, bacteriological loading, and meat quality.

AT PLANT PROCESSING—DEFEATHERING AND CARCASS QUALITY

Brian Kiepper, bkiepper@uga.edu, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA.

Aklilu Giorges and Alex V. Samoylov, Georgia Tech Research Institute, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Broiler carcass defeathering (feather “picking” or “plucking”) is a process done in the poultry processing line immediately after immersion scalding and prior to evisceration. Defeathering is accomplished using automated equipment fitted with banks of rotating rubber finger pickers that exert tangential pressure, causing the feathers to be removed/“plucked” from the skin. Due to the complex shape of chickens, as well as the variable forces required to pick the feathers, several sections of picking banks in series are required for removing all feathers from carcasses. Carcass defeathering takes place after immersion scalding, which significantly reduces feather-to-feather follicle retention force by 90% (Klose et al., 1961, 1962; Dickens and Shackelford, 1988). The current scalding and picking process has been in practice for several decades. The current method of scalding and the defeathering processes is effective in reducing the feather retention force for the removal of feathers from the skin, although it has several drawbacks in terms of energy and water use, as well as food safety and quality (Dickens and Shackelford, 1988). Conventional scalding, loosening feathers from the feather follicles in the skin, is done at relatively high water temperatures (Hard: 59°C–64°C or 138°F–148°F, Medium: 54°C–58°C or 129°F–136°F, and Soft: 50°C–53°C or 122°F–128°F), with corresponding cycle times (Hard: 45 s, Medium: 90 s, and Soft: 120 s) (Owens et al., 2010). The agent that holds the feather within the feather follicle is not known, but it is generally believed to involve the tendons of the feather muscles and the friction and the corneous connecting sheets between the follicular lining and the feather shaft (Ostmann et al., 1964; Lucas and Stettenheim, 1972). Goll et al. (1964) demonstrated the immature collagen begins to solubilize above 45°C, and Briskey et al. (1966) suggested that actin and myosin denature at temperatures of 40°C to 60°C. Therefore, the possibility exists that during scalding (50°C–64°C) moist heat denaturation and a slight solubilization of collagen may occur, causing a loosening effect of the feather within the feather follicle.

It is clear that delay in carcass processing postmortem has an impact in the scalding and picking processes mainly due to the stiffening of the carcass with the onset of rigor mortis. Feather retention force is reduced during immersion scalding; however, the onset of rigor postmortem results in a stiffer carcass that is less flexible during picking resulting in feathers remaining on the carcasses. Our previous laboratory observations showed lower feather removal force with delayed processing when carcasses were held at body temperature; however, it is not clear that the observation is universal.

One of the main objectives of the current work was to assess and evaluate delayed postmortem carcass scalding and picking in a full-scale operating poultry processing setting. Indeed, the on-farm slaughtering process (FSaT) creates a new set of challenges and opportunities for process improvements. Several questions need to be answered to predict the impact of time delay between slaughter and scalding and defeathering. When it comes to feather retention force, it has been established that feather retention force is specific to the area of the carcass (the feather tracts) being picked. For example, wing primary and tail feathers require a high feather-removing force, and the pull force also depends on feather orientation relative to the skin surface (Buhr et al., 1997). Thus, the current work attempted to capture and classify the location and overall carcass picking quality in a commercial processing plant setting.

An experiment consisting of 3 trials, conducted on 3 separate production days, was completed in a commercial broiler processing facility utilizing a total of 240 carcasses. During each trial, 60 broiler carcasses were randomly selected and removed from a shackle line after bleed out and just prior to scalder entry. Selected carcasses were then placed on specially designed hanging racks, leg banded, and assigned to 1 of 3 treatments (2, 4, or 6 h delay scalding and defeathering). The next 20 carcasses were allowed to pass through the scalding tanks and feather pickers as usual without delay, and these carcasses were collected and leg banded for grading as a control group as New York Dressed carcasses following exit from the final picker. Each of the 3 trials utilized 80 carcasses. After the designated delay period, the 20 carcasses assigned to that treatment were rehung on the shackle line prior to the scalder tanks and were scalded and picked. After picking, the carcasses were removed from the shackle line and graded. Carcasses were graded in 4 categories: feather picking quality, number of broken wings, number of broken shanks, and miscellaneous other carcass damage. Feather picking quality was scored as 1, 2, or 3, where 1 indicated no feathers left on carcass, 2 indicated a few remaining feathers, and 3 represented many feathers left on the carcass.

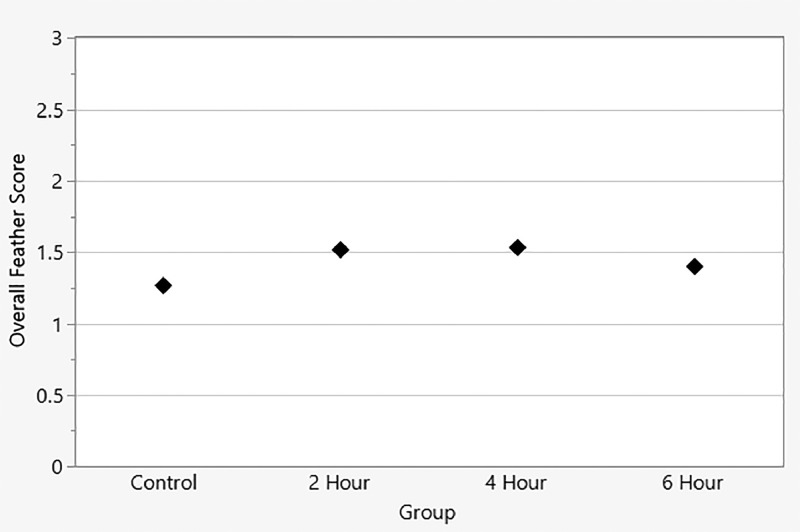

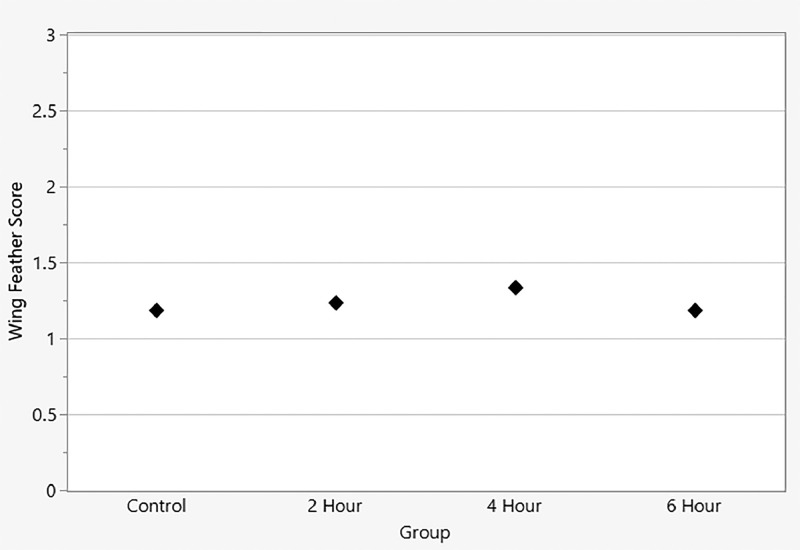

The feather removal quality was evaluated in 3 parts: wings, tail, and overall carcass, where overall included all parts except wings and tail. After the picking process, each individual carcass was evaluated and assigned a value based on the removal of feathers, and the mean feather score was calculated for the 4 groups (control, 2, 4, and 6 h). Figure 3 presents the average feather removal quality observed vs. the delay processing time for overall feather removal quality, where 1 indicates the best and 3 indicates the worst defeathering. Indeed, the flock as well as the experimental day operational conditions varied, and the day-to-day data showed significant variation among the experimental days. In general, a parabolic picking quality trend was observed in all cases with increasing delay scalding time. Furthermore, Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the average feather removal quality score for the wing and tail sections, respectively. The wing feather removal quality score was found to be comparable to the control group except on one of the test days. Similarly, the tail feather removal quality score also showed a similar trend to the wing feather removal for delay processed groups. Since both the wing and tail feathers are known to have greater feather retention force than the other feather tracts on the carcass, but their removal was similar to control defeathering values, indicates that delayed scalding did not directly impact feather retention force. Furthermore, the higher carcass feather picking quality scores for all delayed scalding treatment groups (2–6 h) indicates that carcass stiffness during defeathering most likely hampered optimal carcass rotation during defeathering.

Figure 3.

Average feather removal quality observed for 3 different experimental days.

Figure 4.

Average wing feather removal quality score for 3 different field experimental days.

Figure 5.

Average tail feather removal quality score for 3 different field experimental days.

Tukey's honest significance test described the differences between each group's mean feather score. Table 1 presents each day and overall mean feather scores and letter grades observed. A mean feather picking quality score was calculated for each of the 4 treatment groups (control, 2, 4, and 6 h delay) for each trial and resulting means were statistically analyzed. Experiment results showed significant differences in feather picking quality (control = 1.27b, 2 h = 1.52ab, 4 h = 1.53a, 6 h = 1.40ab). While it was found that the 4 h treatment groups possessed statistically significantly higher feather scores than the control group, no statistically significant differences were found among the treatment groups. Based on the plots and table, the overall picking score shows that the control group performed slightly better.

Table 1.

Overall feather removal quality.

| Group | Mean1 |

|---|---|

| 4 h | 1.53A |

| 2 h | 1.52AB |

| 6 h | 1.40AB |

| Control | 1.27B |

Levels not connected by the same letter are significantly different.

EFFECTS OF DELAYED BROILER CARCASS PROCESSING ON DEFEATHERED CARCASS MICROBIOLOGY

Dianna Bourassa, dvb0006@auburn.edu, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA.

Jeff Buhr, USDA-ARS, Athens, GA, USA.

One major concern with regards to on-farm slaughter is the potential for an impact on the safety of raw poultry products produced in this system. Historically, a carcass that has been bled and had feathers removed was known as a New York Dressed (NYD) carcass. These carcasses had head, feet, and viscera still remaining with the carcass and were held to age and to “develop flavor.” Prior to 1940, most poultry in the United States was shipped as NYD (NRC, 1987). The shift from the sale of poultry as NYD to Ready to Cook (RTC) came about due to market trends, electrical refrigeration replacing ice, and the desire of consumers to have a ready to cook product (Baker et al., 1955). In past research evaluating microbiological differences between NYD and RTC, it was found that NYD carcasses had lower bacterial counts than RTC carcasses, even after multiple days of storage around 45°F (Pennington et al., 1911; Baker et al., 1955). Delaying processing of carcasses for alternative slaughter is similar to NYD in that carcasses are not immediately eviscerated after death. However, carcasses slaughtered in this alternative system are only held for 2 to 6 h prior to scalding, picking, and evisceration, instead of for multiple days. To evaluate the safety of alternatively processed broilers, experiments were conducted to evaluate potential changes in carcass microbiology resulting from a holding period prior to scalding.

A series of experiments were conducted evaluating microbial changes when scalding and defeathering were delayed following slaughter. In Experiment 1, carcasses were held for 0 or 8 h postslaughter and eviscerated whole carcass rinses (WCR) evaluated for aerobic plate counts (APC), Enterobacteriaceae (EB), Salmonella, and Campylobacter. In Experiment 2, carcasses were held for 0 or 4 h at 4°C, 27°C, or 40°C and eviscerated WCR evaluated for APC, EB, Salmonella, and Campylobacter. For Experiment 3, carcasses were processed in a commercial processing facility and held for 0, 2, 4, or 6 h. After defeathering, carcass rinses were evaluated for APC, EB, Salmonella, and Campylobacter.

In Experiment 1, following 8 h of processing delay at room temperature, APC, EB, and Campylobacter were significantly higher at 8 h compared to 0 h, but no difference was observed for Salmonella (Table 2). In Experiment 2, there were significantly fewer Salmonella WCR positive samples for the 40°C carcasses in comparison to 4°C or 27°C carcasses (20 vs. 100%) (Table 3). No differences were observed in APC, EB, or Campylobacter from WCR samples. For Experiment 3, shown in Table 4, no differences were observed for EB (3.6 log CFU/mL) or Salmonella (87% positive). There was a slight increase of approximately 0.4 log CFU/mL of APC after 4 or 6 h of hold time and an increase between 2 and 4 h for Campylobacter (45–79% positive). However, this increase may have been due to carcass defeathering at a later timepoint during the commercial facility operational shift.

Table 2.

Experiment 1. Microbiological analyses of whole carcass rinses from eviscerated carcasses that were held at 24°C for 0 or 8 h between bleedout and scalding.

| Hour | Aerobic plate count | Enterobacteriaceae | Salmonella | Campylobacter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.73B ± 0.35 | 4.02B ± 0.76 | 2/10 | 4/10B |

| 8 | 5.38A ± 0.44 | 4.64A ± 0.44 | 5/10 | 10/10A |

Aerobic plate count and Enterobacteriaceae are reported in log10 CFU/mL of rinsate ± standard error.

Salmonella and Campylobacter prevalence are reported as # positive/# sampled.

Means in the same column with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Experiment 2. Microbiological analyses of whole carcass rinses from eviscerated carcasses that were held for 0 or 4 h at 4°C, 27°C, or 40°C between bleedout and scalding.

| Temperature | Aerobic plate count | Enterobacteriaceae | Salmonella | Campylobacter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No holding | 5.75 ± 0.09 | 4.39 ± 0.06 | 4/5 | 2/5 |

| 4°C | 5.65 ± 0.26 | 4.59 ± 0.38 | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| 27°C | 5.78 ± 0.10 | 4.96 ± 0.17 | 5/5 | 3/5 |

| 40°C | 5.78 ± 0.06 | 4.81 ± 0.13 | 1/5 | 5/5 |

Aerobic plate count and Enterobacteriaceae are reported in log10 CFU/mL of rinsate ± standard error.

Salmonella and Campylobacter prevalence are reported as # positive/# sampled.

Table 4.

Experiment 3. Microbiological analyses of whole carcass rinses from defeathered carcasses that were held for 0, 2, 4, or 6 h at approximately 30°C between bleedout and scalding.

| Hour | Aerobic plate count | Enterobacteriaceae | Salmonella | Campylobacter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No holding | 4.67B ± 0.10 | 3.62 ± 0.14 | 27/30 | 16/30AB |

| 2 h | 4.81AB ± 0.12 | 3.68 ± 0.16 | 25/29 | 13/29B |

| 4 h | 5.06A ± 0.17 | 3.60 ± 0.14 | 24/29 | 23/29A |

| 6 h | 5.06A ± 0.16 | 3.71 ± 0.11 | 26/29 | 21/29AB |

Aerobic plate count and Enterobacteriaceae are reported in log10 CFU/mL of rinsate ± standard error.

Salmonella and Campylobacter prevalence are reported as # positive/# sampled.

Means in the same column with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

Overall, there is no clear indication that holding carcasses for up to 8 h between bleedout and scalding has any impact on the bacterial food safety of the poultry meat produced. The changes in carcass microbiology from 0 h vs. delayed processing carcasses was minimal (<1 log10 CFU/mL) and is not expected to influence meat product safety. Differences observed in the prevalence of Salmonella or Campylobacter were inconsistent and are hypothesized to be due to other factors such as cross-contamination during processing later in the day.

EFFECTS OF DELAYED BROILER CARCASS PROCESSING ON BREAST MEAT QUALITY

Brian Bowker, brian.bowker@usda.gov, and Hong Zhuang, USDA-ARS, Athens, Georgia, USA.

Antemortem factors such as live bird transportation and handling prior to slaughter and processing can impact not only bird well-being but also meat quality. Research has shown that distress on birds generally has a negative impact on meat quality. Theoretically, slaughtering broilers on the farm and transporting carcasses to the processing plant has the potential to improve meat quality by eliminating bird distress related to transportation and handling. However, the logistics required for on-farm slaughter may potentially introduce other variables related to the flow and timing of carcass processing that may impact meat quality. In standard commercial broiler slaughter operations, the major steps of primary processing (stunning, exsanguination, defeathering, and evisceration) occur rapidly with no delays as carcasses are usually placed in chillers within 15 to 20 min after bleeding. With on-farm slaughter there would likely be a time delay between the initial processing steps of stunning and exsanguination and subsequent steps of defeathering, evisceration, and carcass chilling. The interacting phenomena of postmortem muscle energy metabolism, rigor mortis development, and muscle temperature decline due to carcass chilling have a major influence on the transformation of muscle tissue to meat and the final quality of the product. The rate and extent of these intrinsic changes within the muscle and the time postmortem at which they occur relative to slaughter and processing steps can influence meat quality. Compared to conventional slaughtering procedures, the inherent delays between processing steps with on-farm slaughter will likely result in the muscle tissue being at a different postmortem state relative to the processing steps. To determine if delays between slaughter and subsequent carcass processing steps influence broiler breast meat quality, 2 studies were completed. One study was conducted in a pilot processing plant with different types of stunning (electrical, carbon dioxide gas, low atmosphere hypoxia) and a 2 h delay between stunning-bleeding and carcass scalding (Table 5). A second study was conducted at a commercial plant with either a 0, 2, 4, or 6 h delay between stunning (electrical) and bleeding and the carcass scalding (Table 6).

Table 5.

Effect of delayed carcass processing (2 h) with electrical, carbon dioxide gas, and low atmosphere (LA) stunning on breast meat quality (pilot plant experiment1).

| Trait | Control (ES) (n = 30) | ES + 2 h (n = 30) | CO2 + 2 h (n = 30) | LA + 2 h (n = 30) | SEM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discoloration %2 | 11.7 | 60.0 | 70.0 | 73.3 | ||

| L* (skin-side, raw fillet) | 61.6 | 61.3 | 61.1 | 61.7 | 3.21 | 0.903 |

| a* (skin-side, raw fillet) | 1.07b | 2.36a | 2.09ab | 2.67a | 0.30 | 0.002 |

| b* (skin-side, raw fillet) | 13.3 | 14.0 | 13.6 | 14.0 | 0.41 | 0.621 |

| L* (skin-side, cooked fillet) | 80.1a | 76.1b | 79.3ab | 76.6ab | 1.04 | 0.016 |

| a* (skin-side, cooked fillet) | 2.35b | 3.04a | 2.31b | 2.73ab | 0.16 | 0.007 |

| b* (skin-side, cooked fillet) | 19.2b | 20.9a | 19.5ab | 19.1b | 0.42 | 0.017 |

| pH 24 h | 5.99 | 5.98 | 6.00 | 5.99 | 0.07 | 0.868 |

| Drip loss %, d 1 | 2.27c | 2.81bc | 3.15ab | 3.47a | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Drip loss %, d 4 | 5.00b | 6.44a | 6.18a | 7.08a | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Drip loss %, d 7 | 6.92c | 8.15b | 8.47b | 9.94a | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Cook loss % | 21.0 | 21.4 | 21.5 | 22.1 | 4.23 | 0.819 |

| BMORS, peak force (N) | 13.0 | 12.1 | 11.2 | 11.3 | 0.55 | 0.054 |

| BMORS, shear energy (N*mm) | 149.8 | 140.2 | 134.1 | 133.4 | 6.0 | 0.079 |

| Thaw loss % | 6.20b | 7.44ab | 7.34ab | 8.13a | 0.85 | 0.012 |

| Marination uptake % | 12.1 | 10.9 | 10.6 | 11.7 | 0.70 | 0.160 |

| Cook loss %, marinated | 12.8 | 13.6 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 1.37 | 0.468 |

| BMORS, peak force (N), marinated | 6.28b | 8.07a | 7.28ab | 7.30ab | 0.36 | 0.010 |

| BMORS, shear energy (N*mm), marinated | 82.4b | 98.8a | 92.1ab | 90.7ab | 3.3 | 0.008 |

Means in the same row with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

Carcasses were air-chilled at 4°C and breast fillets were deboned at 24 h postmortem for meat quality measurements.

Percentage of fillets with mild to severe discoloration. Calculated based on 30 carcasses (60 breast fillets)/treatment.

Table 6.

Effect of delayed carcass processing (0, 2, 4, 6 h) with electrical stunning on breast meat quality (commercial plant experiment1).

| Trait | 0 h (n = 30) | 2 h (n = 30) | 4 h (n = 30) | 6 h (n = 30) | SEM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discoloration %2 | 0 | 45.1 | 71.6 | 54.8 | ||

| L* (skin-side, raw fillet) | 61.9 | 61.9 | 62.8 | 63.5 | 0.77 | 0.182 |

| a* (skin-side, raw fillet) | 0.48b | 0.77ab | 1.00ab | 1.27a | 0.64 | 0.020 |

| b* (skin-side, raw fillet) | 11.4 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 12.0 | 1.02 | 0.203 |

| L* (skin-side, cooked fillet) | 82.4 | 82.3 | 81.4 | 82.6 | 1.04 | 0.171 |

| a* (skin-side, cooked fillet) | 1.67 | 1.50 | 1.80 | 1.61 | 0.25 | 0.245 |

| b* (skin-side, cooked fillet) | 16.0 | 15.4 | 15.9 | 15.7 | 0.31 | 0.207 |

| pH 24 h | 5.75 | 5.76 | 5.79 | 5.72 | 0.04 | 0.072 |

| Drip loss %, d 1 | 2.18ab | 1.74b | 2.73a | 2.37ab | 0.54 | 0.031 |

| Drip loss %, d 4 | 5.15 | 4.95 | 5.15 | 5.22 | 1.19 | 0.941 |

| Drip loss %, d 7 | 6.93 | 6.41 | 7.02 | 6.83 | 1.77 | 0.701 |

| Cook loss % | 19.5b | 19.9b | 19.9b | 21.8a | 1.08 | 0.010 |

| BMORS, peak force (N) | 18.8a | 17.6ab | 16.0ab | 15.5b | 6.36 | 0.017 |

| BMORS, shear energy (N*mm) | 110.1a | 102.1ab | 93.5b | 91.3b | 27.1 | 0.014 |

| Thaw loss % | 9.33 | 9.16 | 9.66 | 9.48 | 0.81 | 0.834 |

| Marination uptake % | 10.9b | 12.7b | 14.6b | 19.8a | 1.71 | <0.001 |

| Cook loss %, marinated | 15.4 | 15.1 | 14.9 | 15.0 | 1.06 | 0.855 |

| BMORS, peak force (N), marinated | 7.16ab | 7.11ab | 8.18a | 6.61b | 0.65 | 0.046 |

| BMORS, shear energy (N*mm), marinated | 46.9ab | 46.5ab | 52.7a | 42.9b | 4.38 | 0.034 |

Means in the same row with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

Breast fillets were deboned after carcass defeathering, chilled in ice-water, and stored at 4°C until 24 h postmortem for meat quality measurements.

Percentage of fillets with mild to severe discoloration. Calculated based on 30 carcasses (60 breast fillets)/treatment.

With regards to meat quality, the most notable effect observed with delayed carcass processing was on the visual characteristics of the breast meat. In both studies, delayed processing of broiler carcasses resulted in a greater proportion of the raw breast fillets exhibiting reddish discoloration on the cranial end of the muscle. These observations were supported by objective color measurements (L*a*b*) which showed that delayed processing increased redness (a*) values on the surface of raw fillets. No differences were observed in L* (lightness) or b* (yellowness) measurements. The discoloration effect seemed to be more prevalent with gas and low atmosphere stunning in the pilot plant study and with longer holding delays (4 and 6 h) in the commercial plant study. The discoloration was thought to be the result of residual blood collecting at the cranial end of the muscle as the result of the carcasses being hung by the legs during the delay treatments. After cooking the fillets, there were some minor statistical differences in L* (lightness) and b* (yellowness) values between treatments; however, differences in lean color and discoloration were not visually discernable in the cooked fillets. Thus, cooking fillets seemed to minimize any color differences due to delayed processing. Additionally, differences in the visual discoloration in the raw fillets were not observed following a freeze-thaw cycle or vacuum-tumble marination.

The rate and extent of the postmortem pH decline (as glycogen is converted to lactic acid) in muscle can impact the ability of the meat to bind inherent or added water. Delayed processing did not impact ultimate meat pH at 24 h postmortem, regardless of stunning method or the duration of delay in processing. The pH of the breast meat at earlier postmortem times was not measured in these studies; therefore, the impact of delayed processing on the rate of meat pH decline was not determined. With regards to the water-holding capacity of the meat, delayed processing had only minor effects. In the commercial plant study, muscle drip loss was not impacted by delayed processing. However, in the pilot plant study, muscle drip loss was slightly increased in delayed processed samples after 4 and 7 d of cold storage. Freeze-thaw loss was not influenced by delayed processing with electrical stunning (2, 4, or 6 h delay) or gas stunning, but was greater with low atmosphere stunning followed by a 2 h delay in processing. Cook loss was not impacted by delayed processing in the pilot plant study. In the commercial plant study, cook loss was similar between 0, 2, and 4 h delay treatments, but was slightly greater in the 6 h treatment.

Available data suggest that delayed processing can potentially have a positive impact on cooked meat texture. In the commercial plant study, cooked meat shear force decreased with increasing delays in processing. This was likely due to a further progression of rigor mortis development at the time of deboning with delayed processing. In the pilot plant study, although the effect was not statistically significant, there was a strong trend (P < 0.10) for breast fillets from the delayed processing treatments to have lower cooked shear force values than controls even though breast fillets remained on the carcasses until 24 h postmortem.

In these 2 studies, the cranial portions of the fillets were vacuum-tumbled marinated after a freeze-thaw cycle to determine the influence that delayed processing may have on the further-processing potential of broiler breast meat. In the pilot plant study, delayed processing did not have a significant impact on marinade uptake by the fillets. In the commercial plant trial, delayed processing had a positive impact on marinade uptake. In marinated samples, cook loss was not influenced by delayed processing in either trial. Cooked meat shear force in marinated samples was not significantly different between delayed processed samples and controls in the commercial plant trial. However, in the pilot plant study in which breast fillets were not deboned until 24 h postmortem, the average cooked shear force value in marinated samples was slightly greater with electrical stunning and 2 h delayed processing.

Observations from these studies suggest that delaying the time between initial broiler slaughter steps (stunning and bleeding) and carcass defeathering is not detrimental to most meat quality characteristics and may actually improve cooked meat texture. Although delayed processing can potentially increase discoloration (pinking) in the raw breast meat, data suggest that it is not a problem in cooked or marinated meat. It is hypothesized that water-immersion chilling of intact broiler carcasses following delayed processing will help to minimize the potential problems with breast meat discoloration. Further research is warranted to determine how stunning, storage conditions during carcass bleed-out and transportation, and carcass chilling and handling methods can be optimized to enhance meat quality. Overall, these studies suggest that delays in carcass processing that would likely occur with on-farm broiler slaughter would not be problematic with regards to breast meat quality.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from the field trials of the FSaT system did not show major differences between defeathering quality for carcasses processed using traditional methods and the FSaT process. No bacterial differences were observed in APC, EB, or Campylobacter from WCR samples. There was a slight increase of APC after 4 or 6 h of hold time and an increase between 2 and 4 h for Campylobacter. However, this increase may have been due to carcass defeathering at a later time point during the commercial facility operational shift. Observations from the study suggest that delaying the time between initial broiler slaughter steps (stunning-bleeding) and carcass defeathering is not detrimental to most meat quality characteristics and may actually improve cooked meat texture. Overall, these studies suggest that delays in carcass processing that would likely occur with on-farm broiler slaughter would not be problematic with regards to breast meat quality.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- American Veterinary Medical Association . AVMA Guidelines for the Humane Slaughter of Animals: 2016 Edition. AVMA; Schaumburg, IL: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baker R.C., Naylor H.B., Pfund M.C., Einset E., Staempfli W. Keeping quality of ready-to-cook and dressed poultry. Poult. Sci. 1955;35:398–406. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulac K., Crowe T.G., Schwean-Lardner K. Simulated transport of well- and poor-feathered brown-strain end-of-cycle hens and the impact on stress physiology, behavior, and meat quality. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:6753–6763. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedanova I., Voslarova E., Chloupek P., Pistekova V., Suchy P., Blahova J., Dobsikova R., Vecerek V. Stress in broilers resulting from shackling. Poult. Sci. 2007;86:1065–1069. doi: 10.1093/ps/86.6.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briskey E.J., Cassens R.G., Trautman J.C. Univ. Wise. Press; Madison, WI: 1966. The Physiology and Biochemistry of Muscle as a Food. [Google Scholar]

- Buhr R.J., Cason J.A., Rowland G.N. Feather retention force in broilers ante-, peri-, and post-mortem as influenced by carcass orientation, angle of extraction, and slaughter method. Poult. Sci. 1997;76:1591–1601. doi: 10.1093/ps/76.11.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadger S., Crowe T.G., Classen H.L., Watts J.M., Shand P.J. Broiler chicken thigh and breast muscle responses to cold stress during simulated transport before slaughter. Poult. Sci. 2012;91:1454–1464. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadger S., Lee E.S., Crowe T.G., Classen H.L., Shand P.J. Characteristics of cold-induced dark, firm, dry broiler chicken breast meat. Br. Poult. Sci. 2012;53:351–359. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2012.695335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadger S., Lee E.S., Leer T.L.V., Burlinguette N., Classen H.L., Crowe T.G., Shand P.J. Effect of microclimate temperature during transportation of broiler chickens on quality of the pectoralis major muscle. Poult. Sci. 2010;89:1033–1041. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadger S., Lee E.S., Leer T.L.V., Crowe T.G., Classen H.L., Shand P.J. Effect of acute cold exposure, age, sex, and lairage of broiler chicken meat quality. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:444–457. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens J.A., Shackelford A.D. Feather-releasing forces related to stunning, scaling time, and scalding temperature. Poult. Sci. 1988;67:1069–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Frerichs C., Beaulac K., Crowe T.G., Schwean-Lardner K. The effects of simulated transport on the muscle characteristics of white-feathered end-of-cycle hens. Poult. Sci. 2021;100 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frerichs C., Beaulac K., Crowe T.G., Schwean-Lardner K. The influence on behavior and physiology of white-feathered end-of-cycle hens during simulated transport. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll D.E., Hoekstra W.O., Bray R.W. Age associated changes in bovine muscle connective tissue. I. Exposure to increasing temperature. J. Food Sci. 1964;29:615–621. [Google Scholar]

- Henrikson Z.A., Vermette C.J., Schwean-Lardner K., Crowe T.G. Effects of cold exposure on physiology, meat quality, and behavior of turkey hens and toms crated at transport density. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:347–357. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter R.R., Mitchell M.A., Carlisle A.J. Wetting of broilers during cold weather transport: a major source of physiological stress? Br. Poult. Sci. 1999;40:48–49. doi: 10.1080/00071669986828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs L., Delezie E., Duchateau L., Goethals K., Frank A.M. Impact of the separate pre-slaughter stages on broiler chicken welfare. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:266–273. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose A.A., Mecchi E.P., Pool M.F. Observations on factors influencing feather release. Poult. Sci. 1961;40:1029–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Klose A.A., Mecchi E.P., Pool M.F. Feather release by scalding and other factors. Poult. Sci. 1962;41:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Lines J., Berry P., Cook P., Schofield C., Knowles T. Improving the poultry shackle line. Anim. Welf. 2012;21:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A.M., Stettenheim P.R. U. S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1972. Avian Anatomy Integument. Agriculture Handbook 362. [Google Scholar]

- Marder J., Arad Z. Panting and acid-base regulation in heat stressed birds. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1989;94A:395–400. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(89)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M.A., Kettlewell P.J. Physiological stress and welfare of broiler chickens in transit: solutions not problems. Poult. Sci. 1998;77:1803–1814. doi: 10.1093/ps/77.12.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (US) Committee on Public Health Risk Assessment of Poultry Inspection Programs, Chapter 2, Poultry inspection in the United States: history and current procedures, Poultry Inspection: The Basis for a Risk-Assessment Approach, 1987, National Academies Press (US); Washington, DC. Accessed 17 Oct. 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218008/. [PubMed]

- Ostmann O.W., Peterson R.A., Ringer R.K. Effect of spinal cord transection and stimulation on feather release. Poult. Sci. 1964;43:648–654. [Google Scholar]

- Owens C.M., Alvarado C.Z., Sams A.R. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2010. Poultry Meat Processing. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington M.E., Witmer E., Pierce H.C. The comparative rate of decomposition in drawn and undrawn market poultry. U.S. Dept. Agr. Bur. Chem. Circ. 1911;70:5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzkopf-Gensweina K.S., Faucitano L., Dadgar S., Shand P., González L.A., Crowe T.G. Road transport of cattle, swine and poultry in North America and its impact on animal welfare, carcass and meat quality: a review. Meat Sci. 2012;92:227–243. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrey J.M., Kettlewell P.J. Shackling of poultry: is it a welfare problem. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 1994;50:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Strawford M.L., Watts J.M., Crowe T.G., Classen H.L., Shand P.J. The effects of simulated cold weather transport on core body temperature and behavior of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2011;90:2415–2424. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermette C.J., Henrikson Z.A., Schwean-Lardner K., Crowe T.G. Influence of hot exposure on 12-week-old turkey hen physiology, welfare, and meat quality and 16-week-old turkey tom core body temperature when crated at transport density. Poult. Sci. 2017;96:3836–3843. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warriss P.D., Knowles T.G., Brown S.N., Edwards J.E., Kettlewell P.J., Mitchell M.A., Baxter C.A. Effects of lairage time on body temperature and glycogen reserves of broiler chickens held in transport modules. Vet. Rec. 1999;145:218–222. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.8.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]