Abstract

Background:

The palliative care initial encounter can have a positive impact on the quality of life of patients and family carers if it proves to be a meaningful experience. A better understanding of what makes the encounter meaningful would reinforce the provision of person-centred, quality palliative care.

Aim:

To explore the expectations that patients with cancer, family carers and palliative care professionals have of this initial encounter.

Design:

Qualitative descriptive study with content analysis of transcripts from 60 semi-structured interviews.

Setting/participants:

Twenty patients with cancer, 20 family carers and 20 palliative care professionals from 10 institutions across Spain.

Results:

Four themes were developed from the analysis of interviews: (1) the initial encounter as an opportunity to understand what palliative care entails; (2) individualised care; (3) professional commitment to the patient and family carers: present and future; and (4) acknowledgement.

Conclusion:

The initial encounter becomes meaningful when it facilitates a shared understanding of what palliative care entails and acknowledgement of the needs and/or roles of patients with cancer, family carers and professionals. Further studies are required to explore how a perception of acknowledgement may best be fostered in the initial encounter.

Keywords: Palliative care, therapeutic alliance, patients, caregivers, cancer, qualitative research

What is already known about the topic?

Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life of patients and family carers by meeting their individual needs.

The initial encounter is the starting point for establishing a therapeutic alliance.

What this paper adds?

The initial encounter is seen as an opportunity to understand what palliative care entails.

It becomes a positive experience if it facilitates a shared understanding and acknowledgement of the needs and/or roles of patients with cancer, family carers and professionals.

A relationship of trust and safety must be established from the outset.

Implication for practice, theory or policy

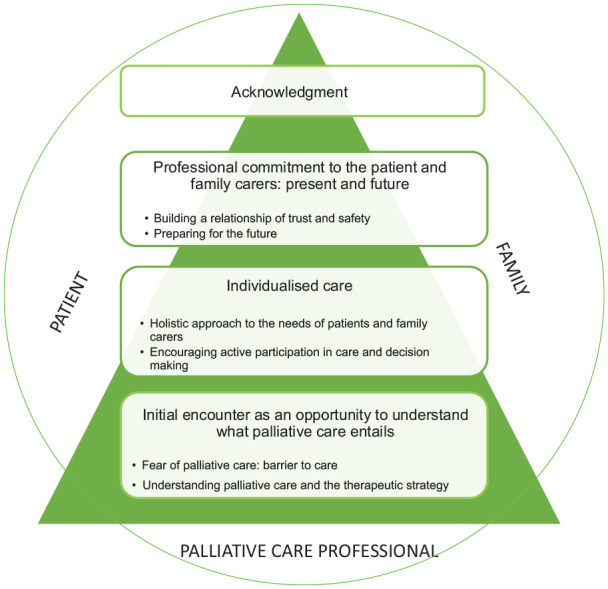

We propose an explanatory model showing how the core goals of palliative care may be met in the initial encounter.

A key task for palliative care professionals in the initial encounter is to identify priority areas of care.

Background

The primary aim of palliative care is to improve the quality of life of patients and their family carers, preventing and alleviating suffering 1 through an individualised approach to needs2–4 (managing symptoms, addressing concerns and the challenges faced). 5 The process of meeting this goal begins in the initial encounter (the latter defined as the first or first and second appointments with the palliative care team) between the patient, family carers and the palliative care team,6–9 the starting point for establishing a therapeutic alliance – the positive connection between patient, family carer and the healthcare professional established through collaboration, communication and respect – and drawing up a care plan. 6 Importantly, a strong therapeutic alliance has been linked to greater acceptance of life-threatening illness, 10 and it can have a positive impact on the quality of life of patients and families. 11 The initial encounter must therefore provide patients the opportunity to express all their needs, which includes broaching the difficult topic of death and dying. 13 This is important as unmet needs are associated with greater emotional distress and increased costs of end-of-life care.14–17

As in the triangle of care model that has been described in relation to dementia, 18 palliative care involves a collaborative relationship between patient, family carers and health professionals, one for which the initial encounter can set the tone. 8 Although some studies explore conversations related to palliative care and end of life care;19,20 to our knowledge, no previous study has examined in depth the expectations that patients with cancer, family carers and professionals have of this first encounter. Exploring their respective views would provide greater insight into what makes the initial encounter meaningful.

Methods

Design

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study informed by naturalistic inquiry as Sandelowski 21 proposes, to explore the expectations of patients with cancer, family carers and health professionals with regard to the palliative care initial encounter. This methodological approach was chosen as it allows to explore and describe the experiences and views of participants in relation to the initial encounter as a phenomenon in a given context (palliative care).

Setting

Participants were recruited from a variety of palliative care services of patients with cancer of 10 institutions across Spain: inpatient service, outpatient clinic and domiciliary care services.

Population

Participants were adult patients with cancer, family carers and palliative care professionals (physicians and nurses) from the palliative care service of ten institutions across Spain recruited after their initial encounter (we refer to the initial encounter as the first or first and second appointment with the palliative care team).

Sample

Patients, and family carers after the first encounter with the palliative care team. We also included physicians and nurses after attending the first encounter with patients and family carer. We used purposive sampling of maximum variability as it was intended to explore the typology of patients in terms of demographic variability, setting and type of cancer. The ultimate goal of this intentional sampling was to obtain information-rich participants for the study. Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for patients, family carers and palliative care professionals.

| Health professionals | 1. Physicians or nurses |

| 2. From inpatient or outpatient palliative care settings | |

| 3. Who had an active role in the initial encounter (defined as the first and second visit) 20 with the patient | |

| 4. And who had a minimum of 2 years of experience in palliative care | |

| Patients | 1. Patients with cancer |

| 2. Who were attending an outpatient or inpatient palliative care service | |

| 3. Had recently had their initial encounter with the palliative care team | |

| 4. Whose symptoms were controlled at the time of interview (according to physician criteria) | |

| 5. Who were informed about and understood why they had been referred to palliative care | |

| 6. And who were considered good informants according to the clinical leads from each participating institution | |

| Family carers | 1. Main caregivers of a patient with cancer |

| 2. Who were present during their relative’s initial encounter with the palliative care team | |

| 3. And who were aware of their relative’s diagnosis and prognosis |

Recruitment

Participants were recruited after their initial encounter in the palliative care service. Patients were referred to palliative care by their oncologist. Patients and family carers were invited to participate in the study by the palliative care professional after the appointment.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured individual interviews conducted between October 2020 and January 2022. This data collection technique is directed toward discovering the who, what, where and how was the experience of the first encounter in the palliative care service, question of special relevance to practitioners and policymakers. The interview guide (Table 2) was developed based on the results of a previous systematic review. 12 All interviews were conducted by the same researcher (BGF), whose professional background is in oncology nursing. Video-based online interviewing was used due to restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. 22 The fact of connecting virtually with the participants, helped us to carry out a sampling of maximum variability. Interviews lasted between 22 and 78 min (mean 52, SD: 16), and they were all audio-recorded and transcribed. All participants provided written informed consent prior to the interview. Recordings and transcripts were assigned an alphanumeric code to ensure anonymity of data; the letter in the code indicated the type of informant (patient with cancer, family carer, health professional).

Table 2.

Questions guiding the semi-structured interview.

| Palliative care professional |

|---|

| • I would like to know how you approach the initial encounter (the first, or first and second appointments) with patients and their family carers. Could you say something about how you go about it? |

| • How do patients react to this? Do they expect you to ask them these things? |

| • What for you is the most important thing to achieve in this initial encounter? |

| • At the end of the interview, what does the patient’s expression tell you about the impact it has had on them? |

| • Do you think they are surprised by any of your questions or the topics you raise? |

| Patient/family carer |

| • What did you think or feel when you were told about the referral to palliative care? (Did it make you think or feel anything in particular?) |

| • Do you remember what your main problems were, the things that most made you suffer at the time you first met with the palliative care team? |

| • Could you tell me something about how you felt during and after that first meeting? |

| • What did they ask you about in the first meeting? Was there anything that surprised you? |

| • Based on what you as the patient/family carer would expect or hope for from the first meeting, what recommendations would you give to the palliative care team? |

Data analysis

Transcripts were read and re-read by one of the researchers (BGF) to develop a broad understanding of the content and were then analysed line-by-line and coded. A content analysis was carried out, a typical analysis strategy of descriptive qualitative studies. 21 Content analysis was performed following the approach proposed by Graneheim and Lundman. 23 Content analysis yielded a total of 752 codes, which were then grouped into categories, subthemes and, at a more interpretative level of analysis, four main themes. 22 This initial interpretation was discussed within the research group, and the proposed themes were reviewed by three other researchers (CMR, IC, DP) to enable triangulation of data. After interviewing ten participants in each of the three groups of informants no new information emerged. However, a total of 20 semi-structured interviews per group were conducted to confirm data and ensure greater variability. Data were categorised using ATLAS.ti 9.

Rigour and trustworthiness of the analysis

To ensure analytical rigour we took into account the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Table 3). 24

Table 3.

Criteria for ensuring rigour and trustworthiness, based on Lincoln and Guba. 24

| Credibility | Triangulation of data by researchers |

|---|---|

| Ensuring data saturation | |

| Transferability and dependability | Description of participants and the setting |

| Confirmability | Description of the data analysis process |

| Interpretation supported by numerous quotes from interviews with participants |

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (ref. MED-2018-10), as well as by the review boards of the 10 participant institutions.

Results

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with 60 participants from ten palliative care services across Spain. Table 4 lists the demographic characteristics of participants.

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics of participants.

| Patients | Family carers | Health professionals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male: 13 | Male: 9 | Male: 6 |

| Female: 7 | Female: 11 | Female: 14 | |

| Mean age (years) ± SD | 70.80 ± 6.25 | 53.40 ± 14.23 | 46.65 ± 7.71 |

| Professional background | Nurse: 8 | ||

| Physician: 12 | |||

| Experience in palliative care (years) ± SD | 13.28 ± 8.73 | ||

| Primary work setting | Inpatient service: 9 | Inpatient service: 7 | Inpatient service: 7 |

| Outpatient clinic: 8 | Outpatient clinic: 11 | Outpatient clinic: 8 | |

| Domiciliary care: 3 | Domiciliary care: 2 | Domiciliary care: 4 | |

| Long-stay facility: 1 | |||

| Type of cancer | Lung: 6 | ||

| Gastrointestinal: 5 | |||

| Genitourinary: 5 | |||

| Breast: 2 | |||

| Bone marrow: 1 | |||

| Liposarcoma: 1 | |||

| Living situation | With spouse/partner: 14 | With the patient: 11 | |

| With son or daughter: 2 | With spouse/partner: 8 | ||

| With other relatives: 1 | Alone: 1 | ||

| Alone: 3 | |||

| Relationship to patient | Spouse or partner: 10 | ||

| Son or daughter: 9 | |||

| Other family relationship: 1 | |||

| Type of cancer of their relative | Lung: 5 | ||

| Gastrointestinal: 6 | |||

| Genitourinary: 3 | |||

| Breast: 2 | |||

| Gynaecological: 2 | |||

| Brain: 1 | |||

| Oral cavity: 1 |

Four themes were developed from the analysis of interviews: (1) initial encounter as an opportunity to understand what palliative care entails, (2) individualised care, (3) professional commitment to the patient and family carers: present and future; and (4) acknowledgement, which derived as a conclusion of the previous themes. Table 5 shows the main themes, sub-themes and categories, along with illustrative quotes for each.

Table 5.

Overview of the main themes, sub-themes and categories, along with illustrative quotes, that describe the perspectives of palliative care professionals, patients and family carers regarding the initial encounter.

| Overarching theme: Acknowledgement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main themes | Sub-themes | Categories | Quotes |

| Initial encounter as an opportunity to understand what palliative care entails | Fear of palliative care: barrier to care | Association with end of life | Patient 16: ‘That word (palliative) really really scares me. My brother died two years ago and he was in palliative care [. . .] when they referred me, I thought it was the end for me, I thought about my own end . . .’ |

| Family carer 11: ‘The first thing you think is that nothing can be done now’. | |||

| Professional 8 (physician): ‘I think they come with the idea that it’s over, that as soon as they hear the word “palliative” it means that nothing more can be done’. | |||

| Question regarding the suitability of the term ‘palliative care’ | Patient 10: ‘They introduced themselves as the team of doctors who would treat my pain’. | ||

| Family carer 16: ‘And the pain was terrible, I spent four days in hospital [. . .] And then the people from the pain clinic came’. | |||

| Professional 1 (nurse): ‘I often say that I’m the symptom management nurse and that we work alongside the oncologists’. | |||

| Understanding palliative care and the therapeutic strategy | Expectations of patients and family carers | Professional 15 (physician): ‘I always ask them what they are expecting from the consultation, what they have been told [. . .] And I always ask them what they expect before explaining how I see it’. | |

| Talking about palliative care | Patient 19: ‘Well, I did think, when they talked about palliative care, well, you think you’re going to die. But then they explained that it was more than this, that it was about dealing with pain, about coping better [. . .] My idea changed after the appointment, I’m OK with it, I’m OK’. | ||

| Family carer 13: ‘Well, they explained what palliative care was. That was the first thing, that it was to see what could be done to help him, to help my Dad feel better’. | |||

| Professional 7 (physician): ‘I explain, and this might take up at least 5 or 10 minutes of the 40 minutes I have available, what palliative care is so that they are not frightened by it. You need to spend time explaining what palliative care is, what it is we do now, which is offer early care of this kind’. | |||

| Need for early intervention | Professional 17 (physician): ‘And they see that it’s about teams working together, that others are there to treat the disease in specific ways, while we’re here to address all the other aspects, it’s not just about treating the cancer’. | ||

| Individualised care | Holistic approach to the needs of patients and family carers | Multidimensional approach with an emphasis on symptom management | Patient 14: ‘My main concern was the pain [. . .] what I wanted was the pain to go away [. . .] every ten metres or so I had to stop or find somewhere to sit down. Because I couldn’t take another step’. |

| Family carer 13: ‘For the pain, because I was never not in pain . . . and now I have a 50 mcg morphine patch, before I needed a rescue tablet every 4 hours [. . .] in the overall scheme of things, it’s better’. | |||

| Professional 14 (physician): ‘If they’re not sleeping because of some worry, then maybe it’s something that can be easily addressed, they tell you about it and then they sleep better, it’s not about giving them pills’. | |||

| Addressing concerns | Patient 13: ‘Rock bottom, that’s how I feel and that’s the worst thing, because I see I’m not able to do anything. A woman who’s worked all her life, there in the market, who’s got up really early every day, who’s had a family at home, there were four or five of us at home. And we were all doing well, and now I’m of no use, I can’t even peel a potato. Now I have to peel a potato sitting down. It really drags me down [. . .] It’s what bothers me the most, feeling that I’m no longer useful’. | ||

| Family carer 7: ‘My Dad, what he doesn’t want is to lose, well, you know, his independence, to have to rely on others’. | |||

| Professional 3 (Nurse): ‘When you ask about their mood, how they’re feeling . . . and what they’re most worried about, then what usually comes up is the issue of dying, that they’re not going to see the grandchildren grow up . . .’ | |||

| Encouraging active participation in care and decision-making | Shared responsibility for decision-making | Patient 5: ‘They asked me what I was most bothered by, and for me it’s the diarrhoea. Apart from that I’m not too bad. Well, there’s the disease of course, but I’ve accepted that. So that’s what we focused on’. | |

| Family carer 13: ‘Well, that was the first thing, that it was to see what could be done to help him, to help my Dad feel better, and we decided together what it was we most needed at that point’. | |||

| Professional 14 (physician): ‘And then to understand more about what the patient’s main problems are, and also those that are most important for them, so it’s about the problems we consider to be the most pressing and those which patients see as being more important, and then drawing up a plan together. They need to see that there’s a plan and that it’s made with them, that we’re working with them’. | |||

| Family carers as facilitators | Patient 19: ‘Oh yes, it gives me confidence (his wife’s presence in the consultation). My wife (he pauses) . . . she’s what I’ve got’. | ||

| Family carer 12: ‘The doctor also spoke to me, she asked me about my mother, how I found her to be, she included me and that did me good’. | |||

| Professional 5 (physician): ‘And a really important thing, I want the first appointment, I want the person and the family carers, because I also want the family to be involved, I want them to feel welcomed and supported by the team, that they feel there’s an open door and a place where their problems will be heard [. . .] and also they (the family) provide extra information about the patient’. | |||

| Professional commitment to the patient and family carers: present and future | Building a relationship of trust and safety | Feeling connected | Patient 15: ‘She told me I could contact her whenever . . . She wrote down the phone number for me. If I needed anything, I should call her. It gives you peace of mind’. |

| Family carer 11: ‘We’re less anxious because we know that if a problem arises, she’s there to help as much as possible’. | |||

| Professional 10 (physician): ‘My hope is that the patient feels better after the consultation, that they feel heard and accompanied and open to us, able to go on. That they feel we have something to offer, something important. That it won’t be a lot of technology or more chemo, but that we have something important to offer them and we’re here for them’. | |||

| Accompanied to the end | Patient 9: ‘Palliative care is about being accompanied, because there might be no way back’. | ||

| Family carer 17: ‘You feel . . . you feel supported, you feel you’re not alone, there’s someone by your side. Well, apart from the family, that is. The medical team, knowing they’ll be there for you’. | |||

| Professional 10 (physician): ‘I might try to change the pain medication, adjust the treatment, but above all it’s about the commitment, communicating to them that we’ll be with them to the end and we’re going to take care of them wherever they are’. | |||

| Active listening | Patient 5: ‘That you can speak, you can explain your problem, being heard, I was grateful for that’. | ||

| Family carer 7: ‘So then I was more relaxed because at that point what he needed was someone to listen to him, to reassure him, because he was really anxious, and the doctor managed to do this. Seeing that my Dad had found someone who listened to him, who reassured him, and that they saw eye to eye, well, that was really important for me’. | |||

| Professional 12 (nurse): ‘It might be that they call saying they’re in a lot of pain and the medication isn’t dealing with it, but then what they least talk to you about is the pain. Instead, there’s a string of worries that they need to share with someone outside the family, someone who they can tell it all to’. | |||

| Preparing for the future | Focusing on the present due to uncertainty about possible suffering in the future vs talking about the future | Patient 9: ‘No, what I mean is, with how things are at the moment I feel strong enough that I don’t need to talk about the end, because I see it as far off. Maybe later, OK, but right now I have the strength to cope with the disease. Who knows what’ll happen tomorrow or the day after, but at the moment I don’t need to talk about it, I see it as far off’. | |

| Family carer 7: ‘For a week now my sisters and I have been talking with Dad, really frankly, about how he’s in the final stage of his life and how he doesn’t want to be in pain’. | |||

| Professional 19 (nurse): ‘And I think what they find hardest to bring up is the question of the end of life. What it will be like . . . that’s what they find hard . . .’ | |||

| Uncertainty about possible suffering | Patient 14: ‘Do you know what? I don’t want to think, to think, I want . . . I want to take things as they come, not come crashing down [. . .] I’m not afraid of death, I’m afraid of suffering’. | ||

| Family carer 7: ‘When they talked about, well, the end of life, my Dad, what he said was that he didn’t want to suffer . . .’ | |||

| Professional 2 (physician): ‘Exploring their fears is essential, so often . . . Not always about death . . . although yes, many of them are afraid of dying, but what a lot of patients fear is suffering’. | |||

| Need for information | Patient 9: ‘I’d like to know, yes, I’d like to know. If I’ll be in pain, if it will be prolonged, all that is what . . .’ | ||

| Family carer 17: ‘Well, I’d prefer them to be straight with me about the disease, because we don’t know . . . is there likely to be long left, we don’t know . . .’ | |||

| Professional 19 (nurse): ‘Later we also look at how much information the patient has about the diagnosis, the prognosis, if they know, if they want to know, because often they don’t want to know . . . the others around them, if they’re there, if they have support . . .∫’ | |||

Theme 1. Initial encounter as an opportunity to understand what palliative care entails

The initial encounter was described as an opportunity to address the fear of palliative care that derives from its association with the end of life, and to enable a better understanding of what palliative care entails.

Subtheme 1. Fear of palliative care: Barrier to care

Patients and family carers spoke of their fear about being referred to palliative care, due to the association of the word ‘palliative’ with the end of life, and hence the referral was often experienced as threatening. This feeling was sometimes heightened in cases where a family member had already died in the context of palliative care.

When they told me I’d be seen by the palliative care team, I thought the worst, I thought about the end [. . .]. When you hear ‘palliative care’ . . . well, you think you’re going to die. (Patient 19)

For their part, health professionals considered that the scope of what they could offer was not well understood, and they were keenly aware of the ‘cultural connotations of palliative care as the end of life’ (Professional 17, physician). They also felt that oncologists and other specialists were often afraid of the impact that a referral to palliative care might have on patients and families, such that referrals were often made late in the process, thus limiting what the palliative care team could do.

We’re a last resort . . . they’ve been treating someone with advanced disease, and eventually they get to the end of the road, and there’s this fear and they make the referral, but by then it can be hard to find a way in to accompany and support families. (Professional 3, nurse)

This perception of palliative care as the end of life leads many professionals to question whether it is the most suitable term to describe what they do. In fact, the majority of those we interviewed referred to themselves as the ‘support or symptom management team’ (Professional 10, physician). Some patients or family carers also referred to the ‘pain team’ (Family carer 13) or ‘symptom management team’ (Patient 11), as this was how the palliative team care had introduced itself.

Subtheme 2. Understanding palliative care and the therapeutic strategy

For professionals, it was important ‘to use the term, to explain what palliative care means’ (Professional 2, physician), and to get across the idea that it is part of the treatment process as a whole. However, they also said that before using the word ‘palliative’, it was necessary to explore how much patients know and what their expectations are. In this respect, the initial encounter is seen as part of the therapeutic strategy and as an opportunity to help patients and family carers understand more about what palliative care entails. Importantly, many of the patients and family carers we interviewed said that their view of palliative care changed following the initial encounter, with some of them recognising that it was about ‘being able to have a better quality of life’ (Family carer 11).

Another aspect highlighted by professionals was the need for contact with palliative care services (inpatient and outpatient services) to be introduced as early as possible so as to counteract the negative connotations associated with it. Doing so can help patients to perceive a more coordinated approach to their treatment and to understand that the palliative care and oncology teams have different but complementary roles to play.

The earlier the patient gets to know us the better, because we work alongside oncology, and once they grasp that there are two teams involved, patients are able to separate what they talk to the oncologist about from what they share with us. (Professional 10, physician)

Theme 2. Individualised care

The initial encounter was also described as reflecting a holistic person-centred approach, in which it was important to encourage patients and family carers to become active participants in the care process and decision-making.

Subtheme 1. Holistic approach to the needs of patients and family carers

Patients and family carers said they expected the initial encounter to address physical symptoms, with an emphasis on managing pain, as this was the most common reason for their referral to palliative care.

At the time I thought they’d sent me to a specialist to sort out my pain. That’s what I thought, as the focus was on pain [. . .]. (Patient 9)

While both patients and family carers considered that needs of this kind had been addressed, they were surprised to be asked about other aspects of the disease and the impact it was having on their lives (the family, loss of autonomy, etc.). However, they felt helped by this more holistic approach.

I was surprised, because I thought it was going to be, I don’t know, more medical, more focused on symptoms . . . and then they asked me all those other things and I thought it was great, I was grateful to be able to talk about all that was bothering me. (Patient 4)

Professionals also highlighted the importance of adopting a holistic approach to needs in the initial encounter: ‘my aim is to identify whatever is causing distress in the patient’ (Professional 4, physician).

Subtheme 2. Encouraging active participation in care and decision-making

For professionals, a key objective in the initial encounter was to involve patients and family carers in ‘care and [. . .] decision-making’ (Professional 7, physician). The family carers we interviewed expressed a willingness to participate in both these aspects. As for patients, although they said they had been invited to participate in decision-making and did so, none of them described this specifically as a need.

Professionals were clear that family carers could play an important role as ‘facilitators’ (Professional 2, physician) of the therapeutic alliance and in helping to understand the patient’s needs, and patients themselves considered family support to be fundamental. For their part, family carers were grateful to be treated as active participants in the initial encounter.

Very good in terms of getting the family to participate, and so we decided things together with the professional we saw upon admission, and well, you appreciate and are grateful for that. (Family carer 10)

Theme 3. Professional commitment to the patient and family carers: Present and future

The commitment to patients and family carers is reflected in the importance that professionals ascribe to building a relationship of trust and safety and to anticipating future needs.

Subtheme 1. Building a relationship of trust and safety

Not only patients but also family carers and professionals referred to palliative care as a safety net. For patients and their family carers, knowing that the team was there for them was a calming influence and made them feel safe. Professionals likewise aimed in the initial encounter ‘to make them feel safe’ (Professional 2, physician), and they also highlighted the need to ensure that patients and families knew that they would be accompanied to the end.

You tell them [the patient and family carers] that we’ll always be there for them, accompanying them, and that we’ll try to help them in all these aspects. (Professional 12, Nurse)

For the professionals there is a need to convey confidence to the patient in order to build a therapeutic relationship. Palliative care professionals fear harming the patient while assessing their needs and therefore, they refer the need to show empathy to build a bond of trust to allow a complete conversation with the patient and family carer. Professionals state that building this bond is important as they feel rejection by patients and family carers due to social association of palliative care with the end of life. Professionals also stressed the importance of active listening in the initial encounter so as to understand the patient’s needs in greater depth. In their view, focusing on the patient’s primary needs and worries helped to create a climate of trust and safety, thus strengthening the therapeutic alliance.

Subtheme 2. Preparing for the future

Some patients said they saw the end of life as something distant and hence they preferred to focus on their current needs and concerns: ‘It’s not something I want to talk about, because it’s not part of my thinking, I see it as far off [. . .] as if right now it doesn’t exist; my concern right now is the pain’ (Patient 19). They also expressed uncertainty about the possibility of suffering, and this generated an aversion to talking about the future. By contrast, some professionals felt it was important to anticipate a patient’s future needs: ‘And you need to plan for the future and anticipate what may emerge as the disease progresses. That’s important for them’ (Professional 10, physician).

Professionals also remarked that conversations about the future were useful for exploring, in the initial encounter, a patient’s possible fears about suffering. However, they felt it was important to decide on a case-by-case basis whether to broach the subject, as some patients did not wish to talk about the end of life.

Another important aspect of the initial encounter for patients and family carers was being informed about the prognosis and expected disease course: ‘I want to know how long I’ve got left’ (Patient 13). Professionals too considered that it was easier to assess a patient’s needs, both present and future, if the patient was well informed: ‘If patients know what the prognosis and diagnosis are, then you can begin to ask them about their values in life, what it means to them to have this happen to them, what are they turning to for support’ (Professional 14, physician).

Theme 4: Acknowledgement

A common theme running throughout the narratives of all three groups of participants was the need for acknowledgement in the palliative care initial encounter. This theme derived as a conclusion of theme 1, 2 and 3. For patients, this manifested in having their different needs heard and attended to, such that they felt understood as a person above and beyond their physical illness. Family carers felt acknowledged by being invited to be active participants in care and decision-making, and through recognition of their role in supporting the patient. As for professionals, it was important for them that patients and family carers gained an understanding both of what palliative care entails and of the fact that the team was there to support them throughout the therapeutic process.

Explanatory model

Finally, on a more interpretative level of analysis, one of the researchers (BGF) re-analysed the categories, sub-themes and themes and developed an explanatory model of how the core goals of palliative care may begin to be met in the initial encounter (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Explanatory model of the initial encounter in palliative care.

The model illustrates how patients with cancer, family carers and palliative care professionals can form a therapeutic partnership in the initial encounter. The basis of palliative care is provided by professionals (the base of the triangle in Figure 1), but their contribution feeds into the experiences of patients with cancer and families, such that together those involved can reach a shared understanding of their respective needs and/or roles (apex of the triangle). The four main themes we identified appear in the model in sequential order (from base to apex). Thus, an understanding of what palliative care entails (Theme 1) must first be achieved so as to enable the development of an individualised and holistic care plan, one that goes beyond symptom management (Theme 2). This individualised approach then paves the way for a professional commitment to the patient and family carers, both now and in the future (Theme 3). These three interconnected themes reflect what needs to be addressed in order to meet the core goals of palliative care, and by doing so all those involved (patient, family carers and professionals) may feel acknowledged (Theme 4) as elements of a therapeutic partnership in a meaningful initial encounter.

Discussion

Main findings of the study

The initial encounter was seen as an opportunity to understand what palliative care entails. In the view of professionals, the fact that the term ‘palliative’ is associated with the end of life25–29 often led to late referrals to their service, thereby limiting what they were able to offer patients.30–32 Although the term is widely used, professionals were nonetheless concerned about its potentially negative impact on patients, 32 and as other studies have found,26,27,33 they sometimes used synonyms such as ‘support’ or ‘symptom management’ team. It has been argued that referring to supportive rather than palliative care may encourage referral to this service,30,34,35 although doing so might hinder a fuller understanding of palliative care by equating it with symptom management.36,37 This is not a trivial issue, insofar as palliative care is also about preventing, not merely ameliorating suffering, hence the importance of early intervention of this kind, as this can have a positive impact on patients’ quality of life,38–41 symptom management,38–40 levels of emotional distress 42 and even survival.38,43 At all events, it is important to address not only patients’ physical symptoms but also their psychosocial and spiritual needs,12,44–46 which if left unmet can undermine quality of life. 4 Accordingly, palliative care needs to be tailored to the biological and psychosocial needs of each individual patient 47 through a holistic approach that is able to address all aspects of their personhood.

Our results support previous research that has highlighted the importance of engaging patients and family carers as active participants from the outset.48–50 Shared decision-making has been found to have a positive impact on patients’ quality of life51,52 and to enhance their perceived control. 53 There is also evidence that it reduces healthcare costs. 54 Although some studies have found that patients are keen to participate in decision-making,52,55 those we interviewed did not regard it as a specific need. This may reflect their trust in the palliative care team, or perhaps a wish to leave decision-making ultimately to the professionals.

Another key issue to emerge from our analysis was the importance of professional commitment to patients and family carers, and this included anticipating what their future needs may be. However, professionals and patients often differed in their preference for talking about the future as opposed to focusing on the present, with many patients opting for the latter, which could be due to concerns about the possibility of future suffering. Hannon et al. 27 argue that being able to talk about future-related fears and preferences is beneficial for patients, reflecting the view that timely conversations about death and dying need to form part of palliative care, provided that the patient’s readiness to engage in such conversations is taken into consideration. 19

Finally, and underpinning all the aforementioned themes, our analysis suggests that the palliative care initial encounter becomes meaningful when it facilitates a shared understanding and acknowledgement of the needs and/or roles of all those involved. For patients, this means being acknowledged in all aspects of their personhood, 56 for family carers it manifests through their active participation in care and decision-making, 57 while for professionals it is about successfully communicating all that they and the palliative care service can offer. 58

What this study adds

Based on the themes and sub-themes that were developed from our analysis of interviews with patients with cancer, family carers and professionals, we propose an explanatory model showing how the core goals of palliative care may begin to be met in the initial encounter. The model comprises four interconnected aspects or levels, which when addressed in an integrated way foster the creation of a partnership of care. As in Maslow’s pyramid of needs, 59 the most basic need – in this case, an understanding of what palliative care entails – must be addressed first, as it is this which paves the way for the development of an individualised care plan and a professional commitment to patients and family carers, the aim of which is to meet their present needs and anticipate future ones.

Based on this model we would argue that the palliative care initial encounter becomes a positive and meaningful experience when it facilitates a shared understanding and acknowledgement of the needs and/or roles of all those involved. This is consistent with the notion of skilled companionship that has been suggested as a way of viewing the nursing role, and where the third level of care corresponds to shared understanding between nurse and patient. 60 At all events, further studies are required to explore how the perception of acknowledgement may best be fostered in the initial encounter.

Strengths and limitations

The primary limitation of this study concerns the specific characteristics of participants, namely clinically stable patients with cancer, family carers of such patients and palliative care physicians and nurses. It is unclear, therefore, to what extent our findings may be generalizable to other populations, that is to say, patients with other life-threatening illnesses and end-of-life care professionals from other disciplines (e.g. psychologists, social workers). Future studies should aim to explore the perspective of these groups regarding the palliative care initial encounter. The major strength of our study is the large number of interviews conducted, allowing data saturation to be reached, as well as the fact that participants were recruited from ten different palliative care settings. A further strength is the triangulation of informants and of data by researchers, which reduces the likelihood of bias in our interpretation.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the importance of the initial encounter in palliative care and suggest that it must serve not only to explore and address the needs of patients and family carers but also to communicate a holistic vision of end-of-life care. Central to this is the establishment of a therapeutic alliance in which a shared understanding and acknowledgement of needs and roles can emerge, thus enabling a partnership of care to be formed. When this is achieved, the initial encounter may become a positive and meaningful experience for all those involved. The explanatory model we propose illustrates how the core goals of palliative care may begin to be met in the initial encounter.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participants in this study for their time and sharing of their experiences. We would also like to thank Alan Nance for translating and copy editing the original manuscript. We also acknowledge the support of Josep Porta-Sales and Albert Balaguer. This study was supported by the WeCare: End-of-life Care Chair at the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) ‘Una manera de hacer Europa’, grant number PI19/01901.

Ethics committee approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya (ref. MED-2018-10), as well as by the review boards of the ten participant institutions.

ORCID iDs: Blanca Goni-Fuste  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1475-4466

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1475-4466

Joaquim Julià-Torras  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1462-3167

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1462-3167

Andrea Rodríguez-Prat  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6382-243X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6382-243X

Iris Crespo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1212-4540

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1212-4540

References

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO Definition of palliative care. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antunes B, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice: a systematic review of facilitators and barriers. Palliat Med 2014; 28(2): 158–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Janssen DJA, Johnson MJ, Spruit MA. Palliative care needs assessment in chronic heart failure. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2018; 12(1): 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang T, Molassiotis A, Pui B, et al. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2018; 17(96): 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osse BHP, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Schadé E, et al. Problems to discuss with cancer patients in palliative care: a comprehensive approach. Patient Educ Couns 2002; 47(3): 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the human connection scale. Cancer 2009; 115(14): 3302–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moorhouse P, Mallery LH. Palliative and therapeutic harmonization: a model for appropriate decision-making in frail older adults. J Am Geriatric Soc 2012; 60(12): 2326–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Danielsen BV, Sand AM, Rosland JH, et al. Experiences and challenges of home care nurses and general practitioners in home-based palliative care: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2018; 17(95): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferraz SL, O’Connor M, Mazzucchelli TG. Exploring compassion from the perspective of health care professionals working in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2020; 23(11): 1478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaye EC, Rockwell S, Woods C, et al. Facilitators associated with building and sustaining therapeutic alliance in advanced pediatric cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4(8): 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas T, Althouse A, Sigler L, et al. Stronger therapeutic alliance is associated with better quality of life among patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2021; 30(7): 1086–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goni-Fuste B, Crespo I, Monforte-Royo C, et al. What defines the comprehensive assessment of needs in palliative care? An integrative systematic review. Palliat Med 2021; 35(4): 651–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crespo I, Monforte-Royo C, Balaguer A, et al. Screening for the desire to die in the first palliative care encounter: a proof-of-concept study. Palliat Med 2020; 24(4): 570–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Faller H, Bülzebruck H, Drings P, et al. Coping, distress, and survival among patients with lung cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56(8): 756–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balboni T, Balboni M, Paulk ME, et al. Support of cancer patients’ spiritual needs and associations with medical care costs at the end of life. Cancer 2011; 117(23): 5383–5391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Winkelman WD, Lauderdale K, Balboni M, et al. The relationship of spiritual concerns to the quality of life of advanced cancer patients: preliminary findings. J Palliat Med 2011; 14(9): 1022–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Hui D, et al. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2012; 30(5): 455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hannan R. Triangle of care. Nurs Older People 2014; 26(7): 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brighton LJ, Bristowe K. Communication in palliative care: talking about the end of life, before the end of life. Postgr Med J 2016; 92: 466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bergenholtz H, Missel M, Timm H. Talking about death and dying in a hospital setting – a qualitative study of the wishes for end-of-life conversations from the perspective of patients and spouses. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19(1): 168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23(4): 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004; 24(2): 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Foley G. Video-based online interviews for palliative care research: a new normal in COVID-19? Palliat Med 2021; 35(3): 625–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25. McIlfatrick S, Slater P, Beck E, et al. Examining public knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards palliative care: a mixed method sequential study. BMC Palliat Care 2021; 20(44): 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Can Med Assoc J 2016; 188(10): E217–E227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hannon B, Swami N, Rodin G, et al. Experiences of patients and caregivers with early palliative care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2017; 31(1): 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sarradon-Eck A, Besle S, Troian J, et al. Understanding the barriers to introducing early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2019; 22(5): 508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sobocki BK, Guziak M. The terms supportive and palliative care—analysis of their prevalence and use: Quasi-systematic review. Palliat Med Pract 2021; 15(3): 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salins N, Ghoshal A, Hughes S, et al. How views of oncologists and haematologists impact palliative care referral: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2020; 19(1): 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. AlMouaalamy N, AlMarwani K, AlMehmadi A, et al. Referral time of advance cancer patients to palliative care services and its predictors in specialized cancer center. Cureus 2020; 12(12): e12300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alcalde J, Zimmermann C. Stigma about palliative care: origins and solutions. Ecancermedicalscience 2022; 16: 1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zambrano SC, Centeno C, Larkin PJ, et al. Using the term “palliative care”: International survey of how palliative care researchers and academics perceive the term “palliative care”. J Palliat Med 2019; 23(2): 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 2011; 16(1): 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sorensen A, Wentlandt K, Le LW, et al. Practices and opinions of specialized palliative care physicians regarding early palliative care in oncology. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28(2): 877–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sorensen A, Le LW, Swami N, et al. Readiness for delivering early palliative care: A survey of primary care and specialised physicians. Palliat Med 2020; 34(1): 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Von Roenn JH, Voltz R, Serrie A. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013; 11(Suppl 1): S11–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med 2010; 363(8): 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 383(9930): 1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ferrell B, Sun V, Hurria A, et al. Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 2015; 50(6): 758–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(8): 834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016; 316(20): 2104–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(13): 1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kane PM, Ellis-Smith CI, Daveson BA, et al. Understanding how a palliative-specific patient-reported outcome intervention works to facilitate patient-centred care in advanced heart failure: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2017; 32(1): 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boucher NA, Johnson KS, Leblanc TW. Acute leukemia patients’ needs: qualitative findings and opportunities for early palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55(2): 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, et al. Redefining palliative care: a new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60(4): 754–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Davison N. Personalized approach and precision medicine in supportive and end-of-life care for patients with advanced and end-stage kidney disease. Semin Nephrol 2018; 38(4): 336–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park M, Giap T, Lee M, et al. Patient- and family-centered care interventions for improving the quality of health care: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Nurs Stud 2018; 87: 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Geerts PAF, Van der Weijden T, Chisari G, et al. The next step toward patient-centeredness in multidisciplinary cancer team meetings: an interview study with professionals. J Multidiscip Healthc 2021; 14: 1311–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tarberg AS, Thronæs M, Landstad BJ, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of patient participation and the involvement of family caregivers in the palliative care pathway. Heal Expect 2022; 25: 1945–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Castro E, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, et al. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99(12): 1923–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kuosmanen L, Hupli M, Ahtiluoto S, et al. Patient participation in shared decision-making in palliative care: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2021; 30(23–24): 3415–3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rodríguez-Prat A, Pergolizzi D, Crespo I, et al. Control in patients with advanced cancer: An interpretative phenomenological study. BMC Palliat Care 2022; 21: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ 2007; 335(7609): 24–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lawhon VM, England RE, Wallace AS, et al. “It’s important to me”: a qualitative analysis on shared decision-making and patient preferences in older adults with early-stage breast cancer. Psychooncology 2021; 30(2): 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Errasti-Ibarrondo B, Pérez M, Carrasco JM, et al. Essential elements of the relationship between the nurse and the person with advanced and terminal cancer: a meta-ethnography. Nurs Outlook 2015; 63: 255–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Van Oosterhout SPC, Ermers DJM, Van Amstel FKP, et al. Experiences of bereaved family caregivers with shared decision-making in palliative cancer treatment: a qualitative interview study. BMC Palliat Care 2021; 20; 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Reigada C, Centeno C, Gonçalves E, et al. Palliative care professionals’ message to others: an ethnographic approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(10): 5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 1943; 50(4): 370–396. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dierckx de Casterlé B. Realising skilled companionship in nursing: a utopian idea or difficult challenge? J Clin Nurs 2015; 24: 3327–3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]