ABSTRACT.

In rural Uganda, many people who are ill consult traditional healers prior to visiting the formal healthcare system. Traditional healers provide supportive care for common illnesses, but their care may delay diagnosis and management of illnesses that can increase morbidity and mortality, hinder early detection of epidemic-prone diseases, and increase occupational risk to traditional healers. We conducted open-ended, semi-structured interviews with a convenience sample of 11 traditional healers in the plague-endemic West Nile region of northwestern Uganda to assess their knowledge, practices, and attitudes regarding plague and the local healthcare system. Most were generally knowledgeable about plague transmission and its clinical presentation and expressed willingness to refer patients to the formal healthcare system. We initiated a public health outreach program to further improve engagement between traditional healers and local health centers to foster trust in the formal healthcare system and improve early identification and referral of patients with plaguelike symptoms, which can reflect numerous other infectious and noninfectious conditions. During 2010–2019, 65 traditional healers were involved in the outreach program; 52 traditional healers referred 788 patients to area health centers. The diagnosis was available for 775 patients; malaria (37%) and respiratory tract infections (23%) were the most common diagnoses. One patient had confirmed bubonic plague. Outreach to improve communication and trust between traditional healers and local healthcare settings may result in improved early case detection and intervention not only for plague but also for other serious conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Plague is a life-threatening zoonosis caused by the gram-negative bacillus Yersinia pestis.1–3 Human plague is usually acquired through the bite of infected rodent fleas, resulting in bubonic plague, characterized by fever and regional lymphadenopathy.1 Left untreated, infection can spread to the lungs, resulting in a fulminant pneumonia. Pneumonic plague is frequently fatal and poses a risk of person-to-person transmission through respiratory droplets.3–6 Cutaneous lesions, gastrointestinal disease with vomiting and diarrhea, and meningitis can also occur.3 These symptoms overlap with other more common diseases, including lower respiratory tract infection, malaria, and sepsis. Early and effective antimicrobial treatment is critical to mitigate morbidity and mortality due to plague and to prevent pneumonic plague outbreaks.

Plague is endemic in specific regions of the Americas, Asia, and Africa,1,7,8 including the highlands of the West Nile region of northwestern Uganda. During a plague outbreak in this region in late 2006, 127 human cases were identified, with 28 deaths.9 An additional 225 human cases were reported during 2008–2016.10,11 Since 2008, the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have partnered to institute a robust plague detection and response program in the West Nile region. Components of this effort include clinic and community-based surveillance for plague in humans and animals, as well as enhanced laboratory diagnosis and rapid response capacity.6,10–12

People living in the predominantly rural, plague-endemic region of Uganda face complex barriers to obtaining healthcare that impact early detection and treatment of plague.10,11 In Uganda, as in much of sub-Saharan Africa, healthcare is often segmented between that provisioned by the formal healthcare system and that provisioned by traditional medicine providers, or “traditional healers.” People with suspected plague who seek care from a traditional healer may do so because of physical distance to a health facility, lack of trust in health facilities, or attribution of symptoms to non-biomedical causes.13–15 A 2013 survey in the region demonstrated that more than half of people who reported experiencing plaguelike symptoms of fever and a swelling in the year prior first sought care from somewhere other than a health center.11 Seeking care from traditional healers delays receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy, increasing the likelihood of transmission to others, including endangering traditional healers themselves.6,11 A traditional healer died of pneumonic plague after unknowingly caring for a patient with plague during an outbreak in Madagascar,16 and a traditional healer died of plague in Uganda during a similar circumstance in the late 1990s (T. Apangu, personal communication).

Lack of mutual trust and open communication between traditional healers and the formal healthcare system in many areas of sub-Saharan Africa is a barrier to early disease detection and improved health outcomes.17–19 Outreach and educational interventions aimed toward traditional healers or improved integration with traditional healers and the formal healthcare system have occurred particularly for HIV/AIDS.20,21 Because plague can be rapidly fatal if not treated in the first few days with appropriate antibiotics, collaboration aimed at early recognition and referral between traditional healers and the formal healthcare system may improve early recognition of plague and mitigate morbidity, mortality, and risk of epidemic spread while decreasing occupational risk for traditional healers. Here, we summarize a qualitative assessment of knowledge and practices of traditional healers related to plague in the plague-endemic West Nile region of Uganda and describe a related public health outreach effort to engage traditional healers and encourage referral of patients with plaguelike illness to nearby health centers to foster early detection and treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Location.

Plague is endemic in areas of higher elevation in Arua and Zombo districts within the West Nile region along the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), approximately 350 km northwest of Kampala. The UVRI’s plague program is headquartered at its field station in the regional hub of Arua City (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Uganda, with Arua and Zombo districts and Arua City denoted. The UVRI Arua Field Station, home of the plague program, is located in Arua City. UVRI = Uganda Virus Research Institute.

Qualitative assessment of knowledge and practices of traditional healers.

To better understand the knowledge, experience, and common practices regarding patients with plaguelike illness, we interviewed a convenience sample of local traditional healers who were identified through recommendations of local health officers, village leaders, and the community of healers themselves. Criteria for inclusion in the qualitative assessment were ≥ 18 years of age and either primary or secondary occupation as a provider of traditional medicine in their community. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all participating traditional healers. Participants were given the equivalent of a $5 phone card (or $5 in Ugandan shillings if they did not have a phone) as compensation for their time.

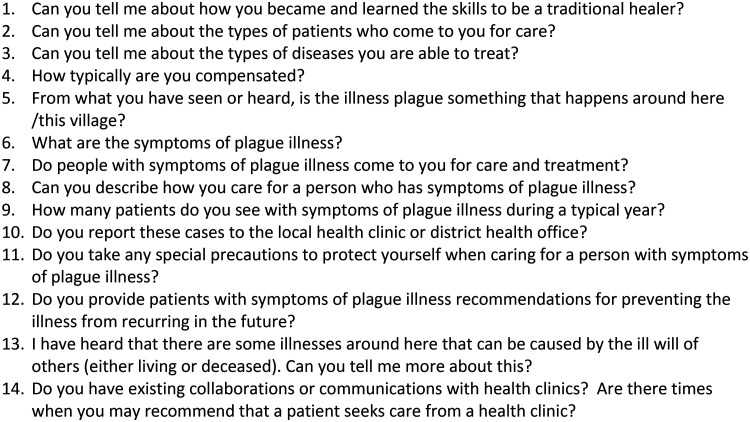

Interviews were conducted during September 2009 and occurred in the local languages spoken in the region using an open-ended, semi-structured interview guide by one of three investigators (M. H. H., E. Z.-G., K. S. G.) with the assistance of two local schoolteachers who served as translators (Figure 2). A second researcher was present to observe and record notes. These schoolteachers were not associated with healthcare provision. Interviews were between 45 minutes and 1 hour in length, and translation occurred in real time during the interviews. Topics covered during interviews included overall practice characteristics (number of patients attended, specialties in treatment, how he/she interacts with patients, etc.), general beliefs around illness causation and treatment, and the traditional healers’ knowledge of plague and their prior experience with plague, if any. Interviews were not recorded; the primary interviewer and the secondary observer took written notes during the interviews. Both sets of notes were synthesized and reviewed for accuracy by the primary interviewer, secondary observer, and translator after each interview.

Figure 2.

Semi-structured interview guide used during interviews with traditional healers.

Data analysis was manually conducted using a grounded theory methodology to identify broad, consistent themes emerging from the interviews.22 Two main researchers (E. Z.-G. and M. H. H.) independently reviewed the qualitative data and agreed upon generated themes. Themes were assigned to broad categories while maintaining any cross-category relationship. General categories included practice characteristics (herbal medicine versus religious faith healer versus spiritual diviner, practitioner training, patient population, acute versus chronic disease care, compensation), knowledge and experience with plague (e.g., clinical diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control), and impressions of and experience with allopathic health centers (e.g., previous collaborations, willingness to collaborate).

Health center referral program.

Recognition of the important role of traditional healers in provisioning first-line care in communities combined with positive reactions from traditional healers participating in the qualitative assessment described above prompted the creation of a collaborative public health outreach program between traditional healers and local health centers. All traditional healers who were part of the qualitative assessment were invited to receive dedicated education on plague; the program encouraged prompt referral of patients presenting with plaguelike illness to local health centers. The outreach program was implemented by UVRI Arua Plague Program clinicians, in conjunction with local administrative and health leaders and clinic staff in the two local languages. Healers received general and plague-specific health education verbally and were provided with a record book, a laminated pictorial guide on plague, and a referral card (Supplemental Figure), which they were instructed to send with patients whom they referred to health centers. When presented at the triage area of the local health center, the card elevated the urgency for evaluation and allowed for rapid triage, moving the referred patient to the front of any queue. All other aspects of patient evaluation and care followed standard clinic procedures for any patient with plaguelike symptoms arriving at the health center, including a physical exam, collection of clinical specimens for laboratory testing, and treatment, as deemed appropriate by the clinician based upon his or her assessment and diagnosis. Traditional healers participating in the initial phase received a simple mobile phone and airtime for use in contacting health center and plague program staff. In later years, neither airtime nor phones were provided; however, healers were compensated for travel, food costs, and their time when meeting at central locations for feedback and discussion.

The outreach program was intended to promote feedback to the healers to ensure that they remained engaged and continued to gain personal and professional satisfaction from the program. Patients were asked by the UVRI Arua and/or local health center staff to return to the traditional healer who referred them after they had recovered from their illness and inform the healers about their experience at the health center. When possible, UVRI Arua and/or health center staff also called the traditional healer to discuss the referral and to answer questions from the traditional healer. The UVRI Arua clinical staff also supported direct medical care in these health facilities during this time under the auspices of plague preparedness; they noted information from clinical log books for persons known to have been referred by traditional healers to ensure information on these patients was captured for provisioning back to each healer on a monthly basis, including the final diagnosis and outcome (improved, died, or referred for a higher level of care). Staff from the UVRI Arua field station met monthly with traditional healers to review referred cases and provide additional or refresher education as needed. General interest and word of mouth led to increased interest among other traditional healers in the region, allowing for program expansion and continued provisioning of informal general and plague-specific health education on ongoing and ad hoc bases to traditional healers, including one-on-one and group meetings where culturally relevant examples and associated discussion could ensue.

We have summarized referrals made by traditional healers participating in the program during 2010–2019 according to clinical outcome and diagnoses made by the health center according to organ system involved. Human subject research approval for the qualitative assessment was obtained from the UVRI, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the CDC. A nonresearch program evaluation determination to summarize the program referrals was obtained from the CDC.

RESULTS

Qualitative assessment.

Among 11 traditional healers approached for participation, all 11 consented to participate in the qualitative assessment. The distance between their homesteads/practice locations and the nearest health center ranged from 1 to 18 km. Most treated patients of all ages.

Practice characteristics of traditional healers.

All traditional healers preferred to be referred to as “doctor.” Six reported receiving training from an independent organization or from another traditional medicine practitioner. Three did not receive formal training but stated that they have an ability based on a gift from an ancestral spirit or god. Most described their practice as fulfilling a calling. Some traditional healers reported treating primarily acute conditions, whereas others reported that they concentrated on chronic conditions that could not be cured at the local clinic or hospital. Several reported a specialty including treating gonorrhea, snakebites, malaria, compound fractures, poisoning, or bewitchment. Notably, a few practitioners specifically stated that they do not treat HIV/AIDS or plague. Treatment occurred in the homestead of the traditional healers, usually in a structure separate from their living quarters. Only one traditional healer used personal protective equipment when treating patients, specifically rubber boots, eyeglasses, and gloves. Others said that they would like to have and use personal protective equipment but lacked access.

The traditional medicine practices of those interviewed varied, with some describing their practice as based primarily on the use of herbs, whereas others described their practice as based on spiritual techniques. Although spiritual traditional healers also used herbs in treatments, they often cited the role of ancestors in their practice. Some spiritual traditional healers used cutting as part of their treatment (alone or in conjunction with an herb poultice), whereas herbal traditional healers reported that they did not cut patients. Among our sample, the herbal traditional healers were located predominantly in Arua district (location dominated by the Lugbara tribe), and spiritual traditional healers were located mainly in Zombo district (location dominated by the Alur tribe).

All respondents reported questioning the patient and evaluating physical characteristics before deciding on a treatment course. The spiritual traditional healers described that ancestral spirits guided them both in diagnosis and treatment (e.g., herb selection or other approaches) of patients.

Knowledge and experience with plague.

When asked about their knowledge of plague, all traditional healers stated that plague occurs in the region and reported some degree of knowledge of plague. All respondents described a role for rats or their fleas in plague transmission. Although most could not quantify the number of patients with plaguelike illness who had presented to their practice, three traditional healers reported seeing 2, 3, and 10 patients, with plaguelike illness during 2008–2009 (the year before the interviews). Although some traditional healers mentioned awareness of previous pneumonic plague outbreaks, they did not identify person-to-person transmission as playing a role in these outbreaks.

Most respondents were familiar with the symptoms of plague, including swelling in the neck, axillary, or inguinal regions (bubos) and commonly associated vomiting, diarrhea, and neck stiffness. They most often pointed to their neck (e.g., cervical bubo) as an example, but several also indicated underarms and groin as possible bubo locations. One practitioner stated:

“The rat comes inside, the flea bites you, and the blood is weak. That’s when a person starts to vomit, have diarrhea, high temperature and then dies.” (Healer #5)

Most respondents indicated that they do not try to treat plague patients in their practice and consider plague to be an illness that is more appropriately treated at a health center; however, one healer indicated that he would incise the bubo with a razor and pack it with herbs, indicating an intent to treat patients with plague directly and lacking any personal protective equipment. Another practitioner explained:

“I had a young girl with plague symptoms. The girl was helpless. I knew to take her to [name of the nearest health center] because I knew the symptoms. I knew I couldn’t help because herbs can’t help plague.” (Healer #7)

Some practitioners mentioned high fever and sudden death as suspicious signs for witchcraft, both of which are possible points of confusion in differentiation of plague. However, respondents stated that buboes were a distinct sign of plague, unlikely to be attributed to bewitchment. Meningitis and curses (e.g., swollen leg due to stepping on an herb that has been cursed and placed in one’s path) were mentioned as illnesses with presentations similar to plague. Responses underscored the challenge in clearly identifying a patient with plague versus another condition that looks like plague:

“With high fever, I give the patient a mix of local herbs, one spoonful, and a powder. If the person sneezes, then it is okay for me to continue. If not, then they must be taken to [name of nearby hospital].” (Healer #3)

and

“I first determine the level of illness; the critically ill person is treated immediately. The ancestral spirit lets me know if I can treat the person or not. Sometimes I don’t know if it’s plague, but the spirit instructs me. Other sicknesses have similar symptoms. Especially high fever is a sign the person has been bewitched. The ancestral spirit rejects those with plague, so they are sent to the clinic.” (Healer #9)

Arranging transport to health centers or hospitals if needed was noted as a challenge. One respondent mentioned that it would be desirable to call ahead if they referred a patient so that the patient would not have to wait (and possibly leave without being seen if the queue was long).

Interaction between traditional and formal health practitioners.

Participating healers noted that patients often seek treatment from traditional healers before going to health centers. Nevertheless, there were descriptions of people seeking traditional healers after treatment in the hospital or health center had “failed,” including in circumstances of “snakebite” (Healer #7) and “poisoning” (Healer #10). Many of the respondents had participated in meetings or trainings at local hospitals in the past. One traditional healer mentioned a specific training focused on identifying patients with leprosy and HIV/AIDS and the need to refer such cases to the hospital. Some were proud to show their certificates or other items they had received at these training programs. Several practitioners mentioned that they had ongoing collaborations with local health centers. All expressed willingness to explore a more formal collaboration with health centers. Several traditional healers stated that they would like to be able to call health centers when they make a referral to ensure that the patient will be seen in a timely manner.

Health center referral program.

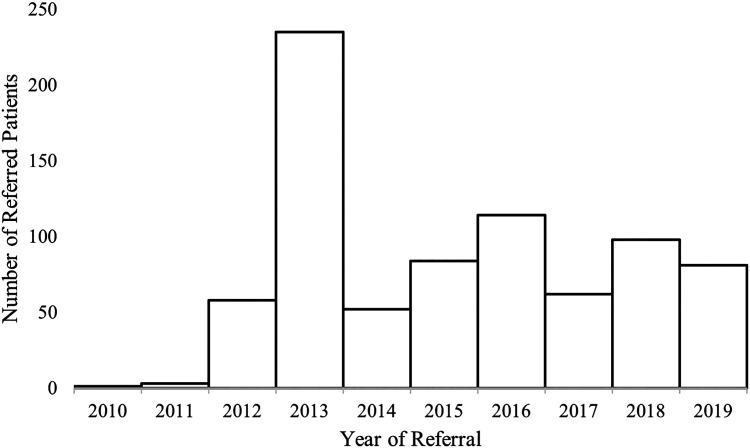

Ten of the 11 traditional healers who participated in the qualitative assessment agreed to participate in the initiation of a public health outreach and referral program. The referral program began in 2010; as a result of word of mouth, the number of healers engaged increased over time to a maximum of 65 in 2019. During 2010–2019, 52 traditional healers (80%) referred a total of 788 patients with plaguelike symptoms to health centers or hospitals (Figure 3). The number of total referrals from traditional healers in the region ranged from 1 to 235 annually (median: 72 referrals). The number of annual referrals from each traditional healer varied widely (range: 0–141; median: 4 patients); five traditional healers referred > 50 patients, whereas 32 traditional healers referred ≤ 5 patients during 2010–2019.

Figure 3.

Total number of patients referred to health centers by traditional healers each year during 2010–2019.

Diagnoses and clinical outcomes of referred patients.

Information on diagnoses ultimately made by health centers was obtained by the UVRI staff working in area health centers during the time period and was available for 775 patients (98%) (Table 1). The most common diagnoses were malaria (37%) and respiratory tract infections (24%). One patient was diagnosed with bubonic plague; other critical diagnoses included severe malaria (10 patients), cerebral malaria (one patient), pulmonary tuberculosis (seven patients), acute abdomen requiring urgent surgery (one patient), and bacterial meningitis (one patient). Among 781 patients with available information on their clinical outcome, nearly all (764; 98%) improved. Fifteen (2%) were referred for a higher level of care, and two (< 1%) died. The diagnoses for the two patients who died were 1) pneumonia with pleural effusion and 2) septicemia.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and diagnoses made by health centers for patients referred by traditional healers

| Demographics | Number of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 401 | 51 |

| < 18 years | 323 | 42 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Malaria | 285 | 36.8 |

| Severe malaria | 10 | 1.3 |

| Cerebral malaria | 1 | 0.1 |

| Respiratory disease | 189 | 24.4 |

| Respiratory tract infection | 148 | 19.1 |

| Pneumonia | 33 | 4.3 |

| Other* | 8 | 1.0 |

| Gastrointestinal disease† | 72 | 9.3 |

| Genitourinary tract disease | 61 | 7.9 |

| Sexually transmitted infection‡ | 35 | 4.5 |

| Urinary tract infection | 23 | 3.0 |

| Other§ | 3 | 0.4 |

| Musculoskeletal disease‖ | 49 | 6.3 |

| Neurologic disease | 30 | 3.9 |

| Seizures/epilepsy | 21 | 2.7 |

| Other¶ | 9 | 1.2 |

| Head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat conditions# | 32 | 4.1 |

| Helminthiasis | 29 | 3.7 |

| Skin and soft tissue infections** | 28 | 3.6 |

| Psychiatric disorder†† | 15 | 1.9 |

| Obstetric or gynecologic disorders‡‡ | 14 | 1.8 |

| Trauma/injury§§ | 11 | 1.4 |

| Tuberculosis‖‖ | 8 | 1.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease¶¶ | 8 | 1.0 |

| Surgical problems | 8 | 1.0 |

| Acute abdomen | 1 | 0.1 |

| Other## | 7 | 0.9 |

| Serious bacterial infections | 5 | 0.6 |

| Plague | 1 | 0.1 |

| Other*** | 4 | 0.5 |

| Other††† | 19 | 2.5 |

NOS = not otherwise specified. Patients could have more than one diagnosis.

Includes asthma (5) and bronchitis (3).

Includes peptic ulcer disease (28), gastroenteritis (15), diarrhea (12), dysentery (7), food poisoning (4), ascites (3), gastroesophageal reflux disease (2), and hemorrhoids (1).

Includes pelvic inflammatory disease (23), sexually transmitted infection NOS (9), and epididymitis/orchitis (3).

Includes benign prostatic hypertrophy (2) and vaginal candidiasis (1).

Includes lower back pain (36), arthritis (6), muscular pain (6), and sciatica (4).

Includes paralysis/paraplegia (5), stroke (2), and neuritis (2).

Includes conjunctivitis (12), otitis media (6), tonsillitis (5), mastoiditis (2), pharyngitis (2), sinusitis (1), cataracts (1), pterygium (1), and dental caries (1).

Includes cellulitis (9), tinea corporis (7), abscess (5), lymphadenitis (3), myositis (2), mastitis (1), and impetigo (1).

Includes mental illness NOS (9), psychosis (3), alcohol misuse (1), conversion disorder (1), and mood disorder NOS (1).

Includes pregnancy (6), active labor (2), dysmenorrhea (2), hyperemesis gravidarum (2), dysfunctional uterine bleeding (1), and puerperal fever (1).

Includes wound or other soft tissue injury (7), fracture (2), snakebite (1), and dog bite (1).

Includes pulmonary tuberculosis (7) and extrapulmonary tuberculosis (1).

Includes hypertension (7) and angina (1).

Includes postoperative pain (4), inguinal hernia (1), chronic appendicitis (1), and lipoma (1).

Includes bacterial meningitis (1), sepsis (1), septic arthritis (1), and enteric fever (1).

Includes HIV testing (3), protein-energy malnutrition (3), diabetes mellitus (3), chicken pox (2), confusion (2), cervical adenopathy (2), allergies (1), allergic dermatitis (1), fatigue (1), and general body pain (1).

A 27-year-old male patient with confirmed plague infection presented with fever, prostration, inguinal adenopathy, weakness, and loss of appetite. He believed that he had stepped on something cursed and sought care from a traditional healer. The traditional healer recognized the inguinal adenopathy as a possible plague bubo and referred the patient to the local health center, calling the center first because of the established contacts associated with the referral program. The traditional healer transported the patient directly via bicycle to the nearest health center, where staff was already prepared for his arrival. After a rapid initial evaluation and appropriate specimen collection for laboratory confirmation, the patient received effective antimicrobial treatment. The UVRI Arua Plague Program personnel visited the patient’s homestead to evaluate his family and perform environmental sampling. The patient’s wife was ill with a cough, although she tested negative for plague. Indoor residual spraying was applied to all homes within the patient’s village to eliminate the potential for off-host Y. pestis–infected fleas to pose an ongoing risk in the area. No additional cases of plague occurred in the village.

DISCUSSION

Traditional medicine practitioners in the plague-endemic northwestern part of Uganda are well-accepted members of the local community who play a vital role in the provision of health care to a population that faces multifactorial barriers to adequate healthcare in the formal healthcare system. The majority of interviewed traditional healers were generally knowledgeable about plague transmission and clinical presentations, and although some indicated they would refer anyone they thought might have plague to the nearby health center, the challenge in identifying plague when compared with other, far more common conditions with similar presentation was evident. Thereafter, we initiated a public health outreach program to improve recognition of possible plague among traditional healers and to promote early referral to local health centers to mitigate morbidity and mortality, decrease occupational risk to traditional healers, and serve as one component of a multipronged approach to community-based surveillance for plague in the region. During the first 10 years of the outreach program, healers referred patients with a wide array of serious illnesses that present with overlapping symptoms to plague, including bubonic plague, as well as severe malaria and respiratory illness, demonstrating public health impacts beyond early detection of plague in the communities.

Plague is episodic, even in endemic areas such as the West Nile region of Uganda. At the time of writing, no confirmed plague had occurred in humans or animals in the West Nile region of Uganda due to autochthonous transmission since 2015; however, an imported pneumonic plague case from the DRC in 2019 led to one additional Ugandan case that was recognized after an alert provided by health authorities in the DRC well before additional chains of transmission could occur.12 Only one plague case was identified through the referral program, likely reflecting decreased enzootic plague activity in this region during the time frame. The engagement with traditional healers served to incorporate them into a multipronged, community-based surveillance system for plague and allowed for rapid initiation of control measures in the village of the patient with confirmed plague, potentially preventing additional cases of plague. Early referral likely saved the patient’s life and may have mitigated progression to pneumonic plague with subsequent potential for secondary transmission, which could have generated a pneumonic plague outbreak with high mortality.

The qualitative assessment of traditional healers in the region was an informative snapshot of the diversity of practices and breadth of knowledge that may exist among this community. The assessment included interviews with a small number of traditional healers and was not intended to develop generalizable knowledge of all practices in the region or outside the region. Furthermore, use of real-time translation during data collection may have resulted in oversimplification of answers and thus diminished the full meaning and integrity of the interview data. Nevertheless, the traditional medicine practices were geographically diverse within this plague-endemic region, although responses related to plague were largely consistent across the respondents on key issues. The public health outreach and health center referral program is an informal collaboration; traditional healers who participated varied in the frequency in which they referred patients. Although patient volume may have varied substantially depending on the size of the population and the presence of other healers working in the same area, some healers did not refer any patients with plaguelike symptoms during 2010–2019, indicating differential 1) uptake of training material or comprehension of plaguelike symptoms, 2) disposition toward the goal of the collaboration and/or willingness to refer patients, or 3) likelihood of certain traditional healers to see patients with acute plaguelike illness, such as those who focus on bone setting or chronic illness. The current program lacks standard curriculum or documents; development of such documents could also improve potential for this type of program to be replicated elsewhere. Similarly, the outreach program was not implemented as a study through which effectiveness of the outreach intervention could be measured quantitatively or qualitatively, such as through measures of change in rate of referrals or through interviews; development of more formal processes for further evaluation are envisioned, although measurement is also complicated by the episodic nature of illness occurrence.

Traditional healers are typically respected community members who play a vital role in the provision of healthcare services to persons with limited access to the formal healthcare system in many parts of the world.23–25 An understanding of the local definitions of illness can equip formal healthcare providers with the ability to more effectively communicate with both patients and alternative providers; yet, physical distance and limited access to safe means of transportation of ill persons remain barriers to early access to the formal healthcare system in the plague-endemic region of Uganda. Additional interventions to support emergency transportation services that also include traditional healers may also further the early detection of severe illnesses in the community. Collaboration, trust, and communication between practitioners of traditional medicine and those of the formal healthcare system in settings where they coexist is paramount to improving early disease detection; such collaboration resulted in improved outcomes for children with severe malaria in Tanzania26 and improved HIV testing rates in rural Uganda.27 Educational interventions may fail if adequate and mutual trust between traditional and formal medical practitioners is not fostered, if traditional healers’ referrals are not honored, or an under-resourced healthcare system is unable to adequately care for referred patients.20 In this context, multiple years of investment in personnel and supplies at health centers in the region for improving plague detection, treatment, and response enabled rapid triage of referred patients at health centers and allowed for clinical care to be provisioned adequately and responsively, fostering an ongoing cycle of trust.

Our findings underscore the importance of increasing collaboration and trust between traditional healers and formal healthcare providers, not only for rare outbreak-prone diseases such as plague, but also as a safety net to improve recognition and treatment of other serious conditions. Similar collaborations in other countries where plague has been common in recent years, including the DRC and Madagascar, may yield not only improved early detection of this severe and rapidly fatal disease but also improve health outcomes for a variety of acute conditions.

CONCLUSION

Traditional healers serve as de facto frontline healthcare providers in many parts of the world, including those where plague is endemic. In the plague-endemic area of Uganda, formal engagement between traditional healers and health centers that focused on plague resulted in improved collaboration and referral of critically ill patients with general plaguelike symptoms who suffered from a broad range of conditions, extending its impact far beyond plague. These findings support the rationale for improved collaboration between traditional healers and the formal healthcare system—healers should be incorporated as a component of community-based surveillance for plague in endemic areas to foster early disease detection and mitigation of morbidity and mortality. Such collaboration can foster improved health outcomes far beyond the initial disease focus.

Supplemental Materials

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Uganda Ministry of Health, Arua and Zombo district governments, health facility staff, participating traditional healers, and the communities in the West Nile region of Uganda. We also thank Christine Black and Kerry Cavanaugh for their assistance.

Note: Supplemental material appears at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. Prentice MB, Rahalison L, 2007. Plague. Lancet 369: 1196–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perry RD, Fetherston JD, 1997. Yersinia pestis–etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev 10: 35–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson CA, Meaney-Delman D, Fleck-Derderian S, Cooley KM, Yu PA, Mead PS, 2021. Antimicrobial treatment and prophylaxis of plague: recommendations for Naturally acquired infections and bioterrorism response. MMWR Recomm Rep 70: 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kool JL, 2005. Risk of person-to-person transmission of pneumonic plague. Clin Infect Dis 40: 1166–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nelson CA, Fleck-Derderian S, Cooley KM, Meaney-Delman D, Becksted HA, Russell Z, Renaud B, Bertherat E, Mead PS, 2020. Antimicrobial treatment of human plague: a systematic review of the literature on individual cases, 1937–2019. Clin Infect Dis 70: S3–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Begier EM. et al. , 2006. Pneumonic plague cluster, Uganda, 2004. Emerg Infect Dis 12: 460–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bertherat E, 2019. Plague around the world in 2019. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 94: 289–292. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schneider MC, Najera P, Aldighieri S, Galan DI, Bertherat E, Ruiz A, Dumit E, Gabastou JM, Espinal MA, 2014. Where does human plague still persist in Latin America? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) , 2009. Bubonic and pneumonic plague – Uganda, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 58: 778–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Forrester JD. et al. , 2017. Patterns of human plague in Uganda, 2008–2016. Emerg Infect Dis 23: 1517–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kugeler KJ. et al. , 2017. Knowledge and practices related to plague in an endemic area of Uganda. Int J Infect Dis 64: 80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Apangu T. et al. , 2020. Intervention to stop transmission of imported pneumonic plague – Uganda, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69: 241–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sundararajan R, Mwanga-Amumpaire J, Adrama H, Tumuhairwe J, Mbabazi S, Mworozi K, Carroll R, Bangsberg D, Boum Y, Ware NC, 2015. Sociocultural and structural factors contributing to delays in treatment for children with severe malaria: a qualitative study in southwestern Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 92: 933–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Savigny D, Mayombana C, Mwageni E, Masanja H, Minhaj A, Mkilindi Y, Mbuya C, Kasale H, Reid G, 2004. Care-seeking patterns for fatal malaria in Tanzania. Malar J 3: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kengeya-Kayondo JF, Seeley JA, Kajura-Bajenja E, Kabunga E, Mubiru E, Sembajja F, Mulder DW, 1994. Recognition, treatment seeking behaviour and perception of cause of malaria among rural women in Uganda. Acta Trop 58: 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ratsitorahina M, Chanteau S, Rahalison L, Ratsifasoamanana L, Boisier P, 2000. Epidemiological and diagnostic aspects of the outbreak of pneumonic plague in Madagascar. Lancet 355: 111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Audet CM, Hamilton E, Hughart L, Salato J, 2015. Engagement of traditional healers and birth attendants as a controversial proposal to extend the HIV health workforce. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 12: 238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Watt ASJ. et al. , 2017. Collaboration between biomedical and complementary and alternative care providers: barriers and pathways. Qual Health Res 27: 2177–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chipolombwe J, Muula AS, 2005. Allopathic health professionals’ perceptions towards traditional health practice in Lilongwe, Malawi. Malawi Med J 17: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Audet CM, Salato J, Blevins M, Amsalem D, Vermund SH, Gaspar F, 2013. Educational intervention increased referrals to allopathic care by traditional healers in three high HIV-prevalence rural districts in Mozambique. PLoS One 8: e70326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS , 2006. Collaborating with Traditional Healers for HIV Prevention and Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: Suggestions for Programme Managers and Field Workers. Available at: https://data.unaids.org/pub/report/2006/jc0967-tradhealers_en.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2023.

- 22. Corbin J, Strauss A, 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moshabela M. et al. , 2017. Traditional healers, faith healers and medical practitioners: the contribution of medical pluralism to bottlenecks along the cascade of care for HIV/AIDS in Eastern and Southern Africa. Sex Transm Infect 93 (Suppl 3): e052974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization , 2013. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy: 2014–2023. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506096. Accessed February 1, 2023.

- 25. Konde-Lule J, Gitta SN, Lindfors A, Okuonzi S, Onama VO, Forsberg BC, 2010. Private and public health care in rural areas of Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 10: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Makundi EA, Malebo HM, Mhame P, Kitua AY, Warsame M, 2006. Role of traditional healers in the management of severe malaria among children below five years of age: the case of Kilosa and Handeni Districts, Tanzania. Malar J 5: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sundararajan R, Ponticiello M, Lee MH, Strathdee SA, Muyindike W, Nansera D, King R, Fitzgerald D, Mwanga-Amumpaire J, 2021. Traditional healer-delivered point-of-care HIV testing versus referral to clinical facilities for adults of unknown serostatus in rural Uganda: a mixed-methods, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health 9: e1579–e1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.