Key Points

Question

Which pharmacotherapies are associated with improved outcomes for people with alcohol use disorder?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis that included 118 clinical trials and 20 976 participants, 50 mg/d of oral naltrexone and acamprosate were each associated with significantly improved alcohol consumption-related outcomes compared with placebo.

Meaning

These findings support oral naltrexone at 50 mg/d and acamprosate as first-line therapies for alcohol use disorder.

Abstract

Importance

Alcohol use disorder affects more than 28.3 million people in the United States and is associated with increased rates of morbidity and mortality.

Objective

To compare efficacy and comparative efficacy of therapies for alcohol use disorder.

Data Sources

PubMed, the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane Central Trials Registry, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and EMBASE were searched from November 2012 to September 9, 2022 Literature was subsequently systematically monitored to identify relevant articles up to August 14, 2023, and the PubMed search was updated on August 14, 2023.

Study Selection

For efficacy outcomes, randomized clinical trials of at least 12 weeks’ duration were included. For adverse effects, randomized clinical trials and prospective cohort studies that compared drug therapies and reported health outcomes or harms were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers evaluated each study, assessed risk of bias, and graded strength of evidence. Meta-analyses used random-effects models. Numbers needed to treat were calculated for medications with at least moderate strength of evidence for benefit.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was alcohol consumption. Secondary outcomes were motor vehicle crashes, injuries, quality of life, function, mortality, and harms.

Results

Data from 118 clinical trials and 20 976 participants were included. The numbers needed to treat to prevent 1 person from returning to any drinking were 11 (95% CI, 1-32) for acamprosate and 18 (95% CI, 4-32) for oral naltrexone at a dose of 50 mg/d. Compared with placebo, oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) was associated with lower rates of return to heavy drinking, with a number needed to treat of 11 (95% CI, 5-41). Injectable naltrexone was associated with fewer drinking days over the 30-day treatment period (weighted mean difference, −4.99 days; 95% CI, −9.49 to −0.49 days) Adverse effects included higher gastrointestinal distress for acamprosate (diarrhea: risk ratio, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.27-1.97) and naltrexone (nausea: risk ratio, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.51-1.98; vomiting: risk ratio, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91) compared with placebo.

Conclusions and Relevance

In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, these findings support the use of oral naltrexone at 50 mg/d and acamprosate as first-line pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder.

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates efficacy and comparative efficacy of 9 therapies for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Introduction

Unhealthy alcohol use is the third leading preventable cause of death in the United States, accounting for 145 000 deaths annually.1 Data from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health suggested that more than 28.3 million people aged 12 years or older in the United States met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) (DSM-5) criteria for alcohol use disorder (eTable 1 in Supplement 1) in the past year.2,3 The COVID-19 pandemic may have been associated with increased numbers of people with alcohol use disorder.2,3 Among the 29.5 million people reporting a past-year alcohol use disorder in 2021, an estimated 0.9%, or 265 000 people, received pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder.4

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated efficacy and comparative efficacy of 9 therapies for alcohol use disorder that are either approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (eTable 2 in Supplement 1) or more commonly used in the United States for alcohol use disorder.

Methods

The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022324376). A full technical report that addressed 5 questions (eTable 3 in Supplement 1) details methods, search strategies, and additional information.

Data Sources and Searches

PubMed, the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane Central Trials Registry, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and EMBASE were searched for English-language studies of adults aged 18 years or older from November 1, 2012, to September 9, 2022; eligible articles published before these searches were obtained from a previously published (2014) systematic review on this topic.5,6 A librarian (C.V.) performed all searches. A second librarian peer-reviewed the searches using the validated Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist.7 Reference lists of pertinent reviews and trials were manually searched for additional relevant citations. After September 9, 2022, an ongoing systematic monitoring of the literature was conducted through article alerts. An updated search of PubMed was conducted on August 14, 2023, to identify studies published since that may affect the conclusions or understanding of the evidence; those searches did not identify new studies for inclusion.

Study Selection

Studies that enrolled adults with alcohol use disorder and evaluated an FDA-approved medication (acamprosate, disulfiram, or naltrexone) or any of 6 off-label medications (baclofen, gabapentin, varenicline, topiramate, prazosin, and ondansetron) for at least 12 weeks of treatment in an outpatient setting were eligible for inclusion. Twelve weeks of treatment were required because longitudinal studies reported that shorter treatment may yield misleading conclusions about efficacy due to fluctuations in drinking behavior. Eligible studies were required to assess 1 of the following outcomes: (1) alcohol consumption, consisting of return to any drinking, return to heavy drinking, percentage of drinking days, percentage of heavy drinking days (≥4 drinks per day for women; ≥5 drinks per day for men), or number of drinks per drinking day; (2) health outcomes—motor vehicle crashes, injuries, quality of life, function, or mortality; or (3) adverse events.

For efficacy outcomes, double-blind randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that compared 1 of the FDA-approved or off-label medications listed above with placebo or with another medication were eligible for inclusion. For adverse effects, in addition to the double-blind RCTs included for efficacy, studies with the following designs were eligible if they compared 2 drugs of interest: nonrandomized or open-label trials, subgroup analyses from trials, prospective cohort studies, and case-control studies. Nonrandomized and observational studies were included to address harms because RCTs had insufficient sample sizes and duration to identify rare harms.

Two investigators independently reviewed each title and abstract. Studies marked for possible inclusion by either reviewer underwent independent full-text review by 2 reviewers. If the reviewers disagreed, they resolved conflicts by discussion and consensus or by consulting a third, senior member of the team.

Data Extraction, Risk-of-Bias Assessment, and Strength of Evidence

Structured data extraction forms were used to gather relevant data from each article. At least 2 investigators reviewed all data extractions for completeness and accuracy.

To assess the risk of bias of studies, the investigators used predefined criteria based on established guidance.8,9,10 The studies were rated as having low, medium, high, or unclear risk of bias.8,9 Questions were included about adequacy of randomization, allocation concealment, similarity of groups at baseline, masking, attrition, validity and reliability of measures, approaches to analyses, and methods of handling missing data. Two independent reviewers assessed risk of bias for each study. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The strength of evidence was graded as high, moderate, low, or insufficient based on established guidance.11 The approach incorporated 4 key domains: risk of bias, consistency, directness, and precision. Two reviewers assessed each domain for each outcome and determined an overall grade. Differences were resolved by consensus.

In these analyses, results are presented for medications for which there was at least low strength of evidence for benefit for some outcomes.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The primary outcome was alcohol consumption, defined as any alcohol use, return to heavy drinking, and number of drinks per week. Meta-analyses of RCTs were performed using random-effects models.12 We used the DerSimonian and Laird estimator for our primary analyses, with sensitivity analyses using a restricted maximum likelihood model when the pooled effects were statistically significant. For continuous outcomes, weighted mean differences (WMDs) and 95% CIs were calculated. For binary outcomes, risk ratios (RRs) between groups and 95% CIs were calculated. The I2 statistic was calculated to assess statistical heterogeneity.13,14 Potential sources of heterogeneity were examined by analyzing subgroups defined by patient population (eg, US vs non-US studies). Analyses were conducted using Stata version BE-17 (StataCorp). Statistical significance was assumed when 95% CIs of pooled results did not cross 0. All testing was 2-sided. Numbers needed to treat were calculated when pooled RRs for binary outcomes found a statistically significant result and there was at least moderate strength of evidence for benefit. When quantitative synthesis was not appropriate (eg, <2 similar studies), the data were synthesized qualitatively.

Results

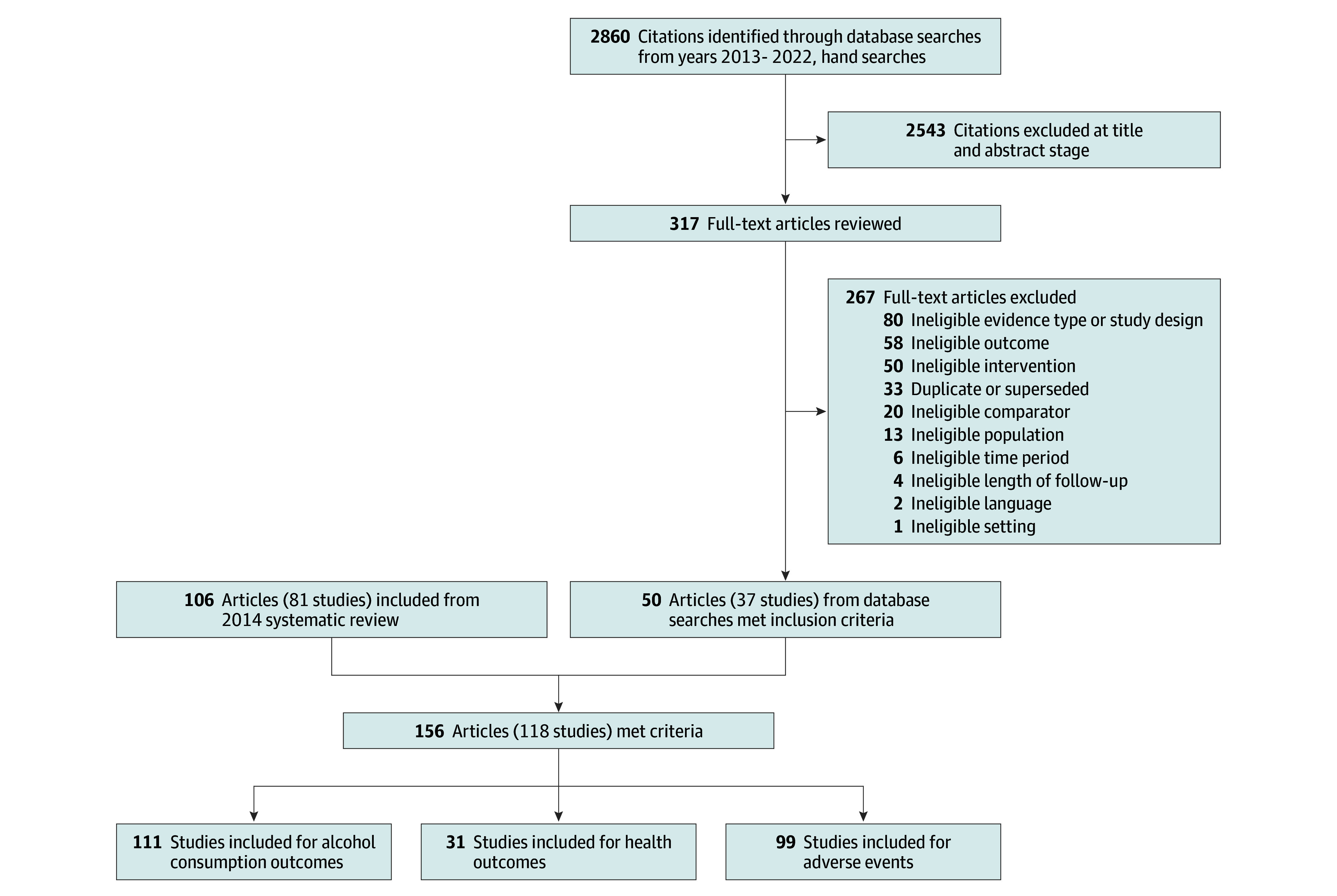

The database search identified 2860 citations, and 2543 citations were excluded during title and abstract review. Of 317 full-text articles included after title and abstract review, 267 were excluded, leaving 156 articles that described results of 118 RCTs (Figure 1). Of these, 81 RCTs (106 articles) were included in the 2014 systematic review on this topic,5 and 37 RCTs (50 articles) were new. No observational studies providing data on adverse effects were identified, and therefore all data on adverse events were obtained from RCTs.

Figure 1. Study Identification and Review for Medications Used in the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder.

Characteristics of the 37 RCTs that were new since 2104 are shown in eTable 4 in Supplement 1. Sample sizes ranged from 12 to 921. Treatment duration ranged from 12 to 52 weeks. All participants met criteria for alcohol dependence in 103 of 118 of the clinical trials. Recruitment methods varied and included treatment programs, advertisements, referrals, or a combination. Eighty-seven (73.7%) of 118 studies included psychosocial co-interventions. For these studies, effect sizes reflect the benefits of medications added to psychosocial interventions compared with placebo added to psychosocial interventions. Of 23 studies that assessed efficacy of acamprosate, 16 were conducted in Europe and 4 were conducted in the United States. Of 49 studies of naltrexone, 32 were conducted in the United States and 8 were conducted in Europe. Of the 118 included studies, 100 included a co-intervention such as medical management, specific harm reduction, or counseling approaches.

Three medications (ondansetron, varenicline, and prazosin) had either low strength of evidence suggesting benefit or insufficient evidence and are not further discussed (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

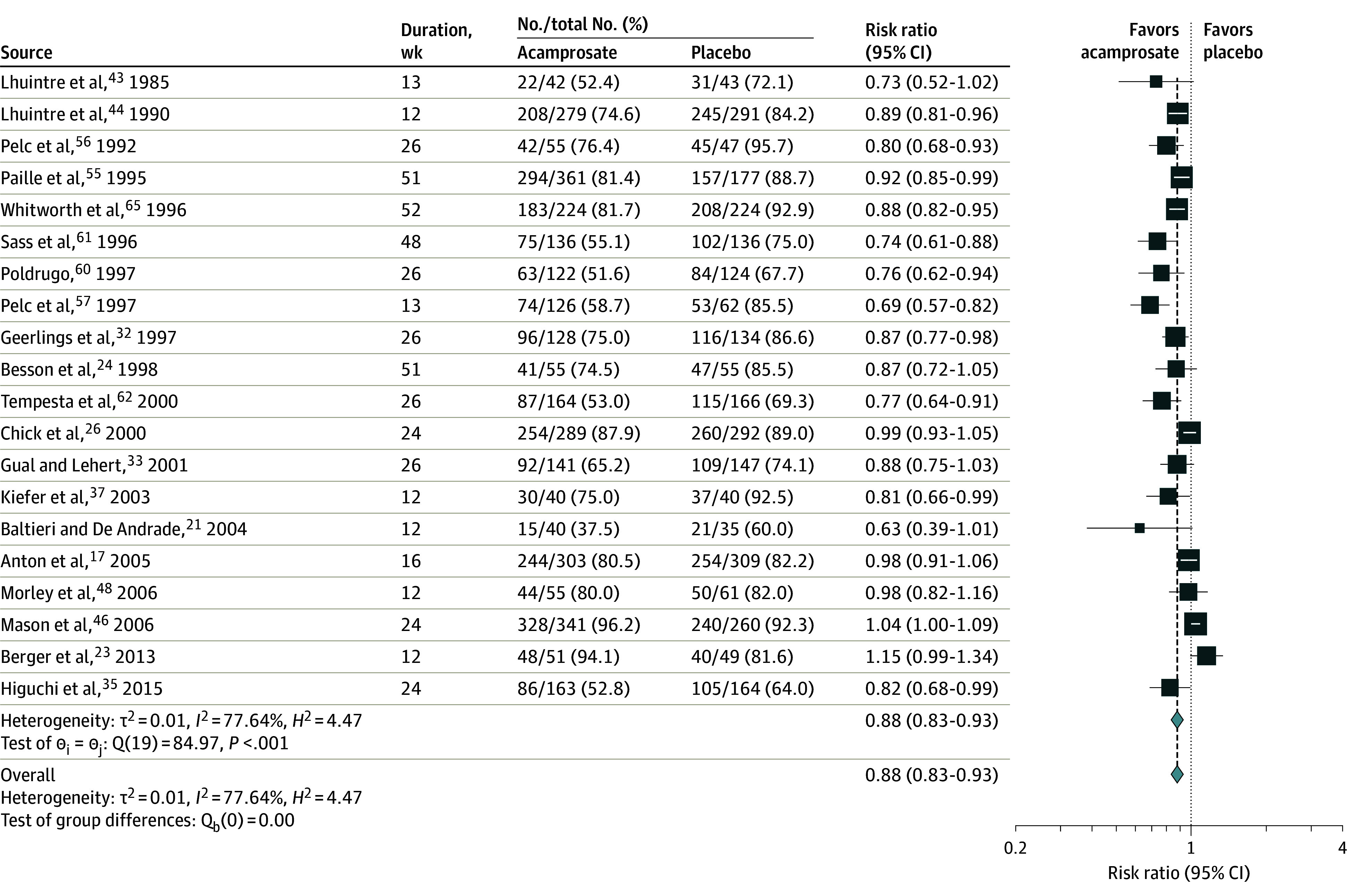

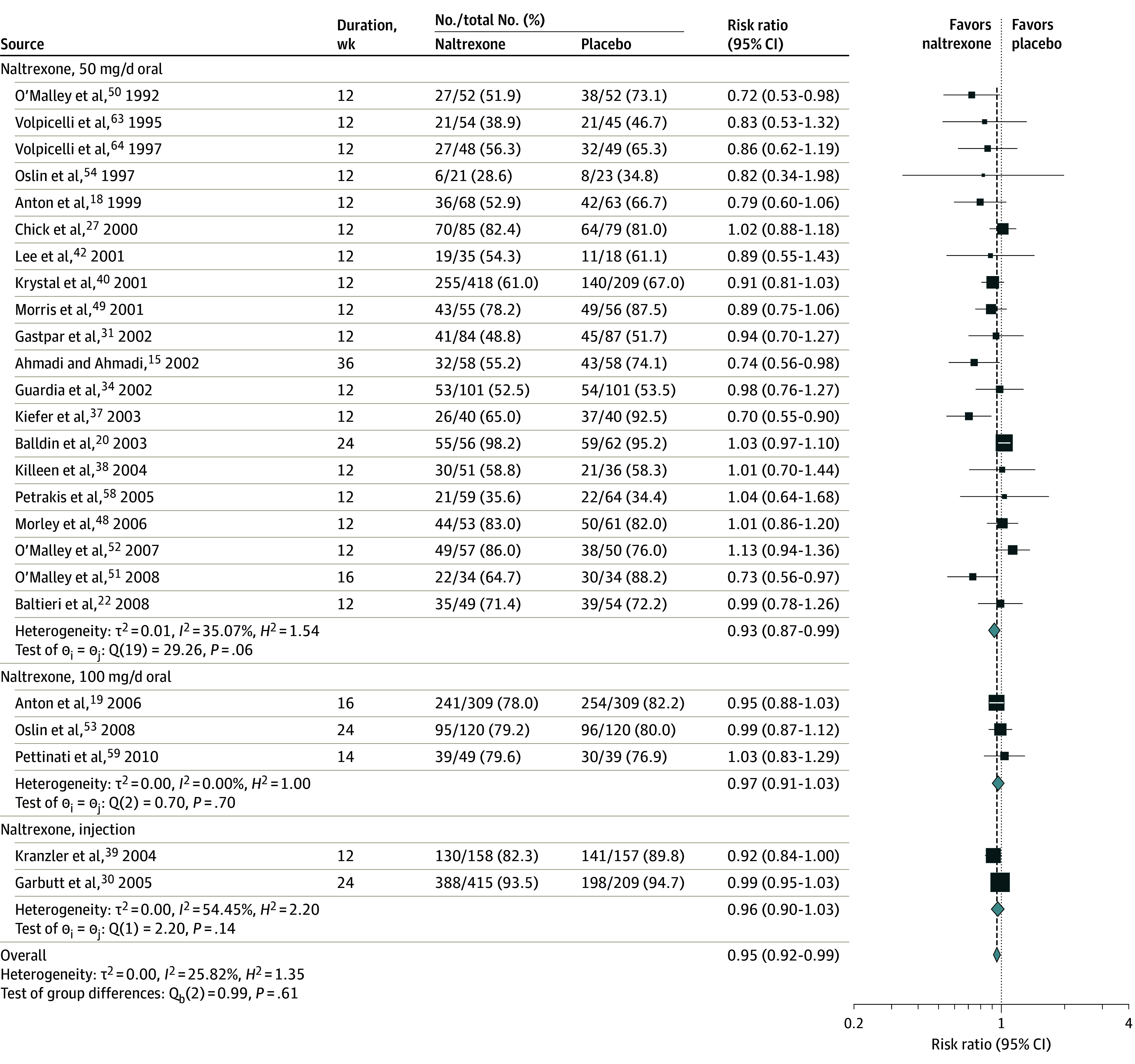

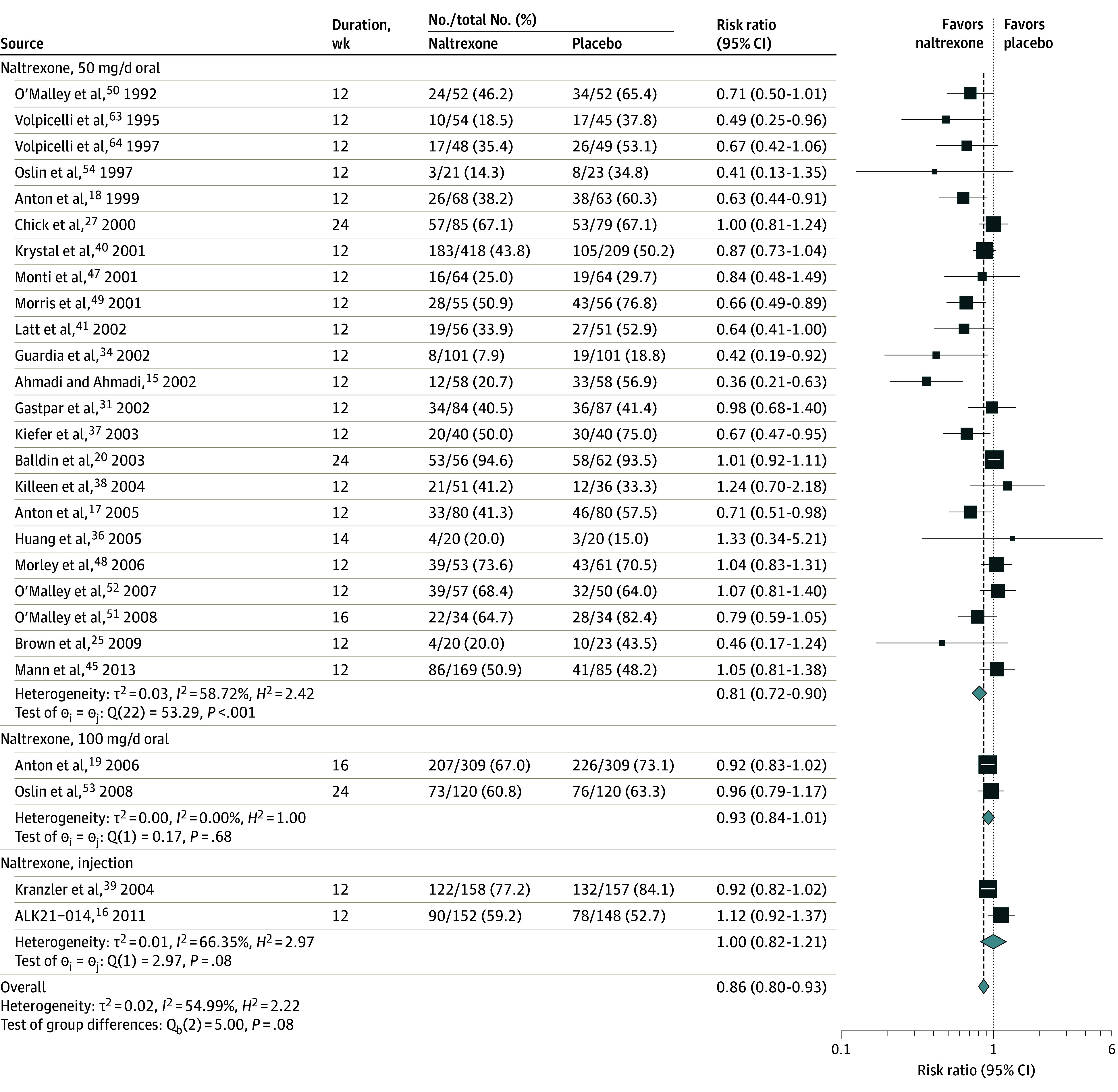

Alcohol Consumption Outcomes

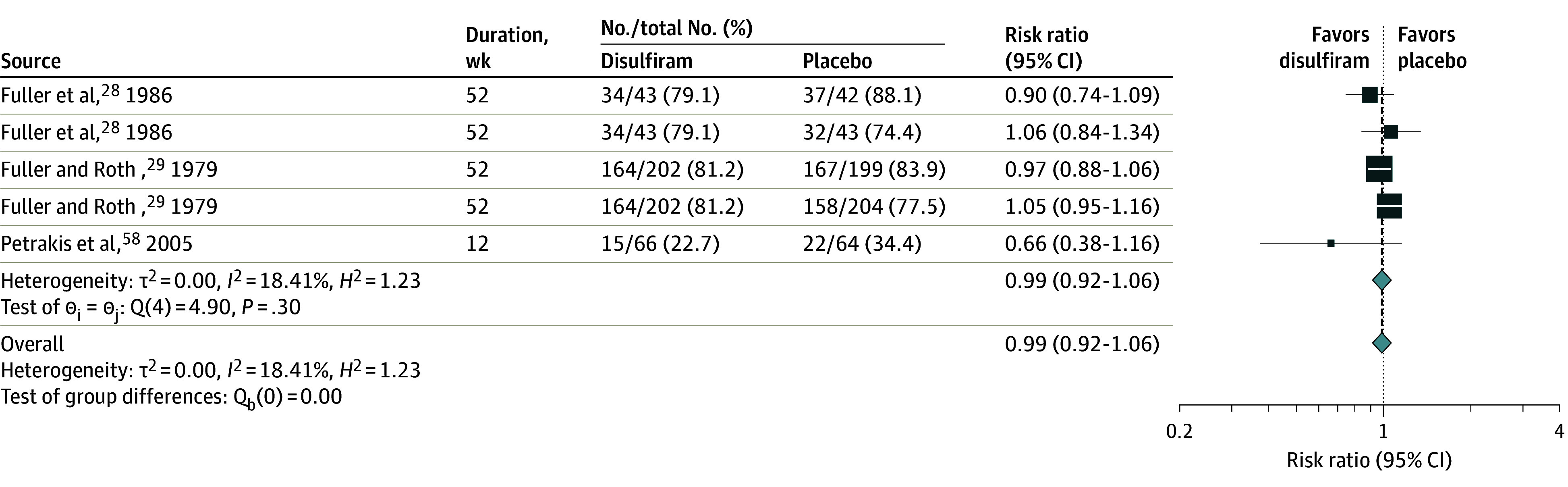

Among the medications with an FDA indication for alcohol use disorder, acamprosate and naltrexone were associated with statistically significant improvement in alcohol consumption outcomes (Table, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6; eAppendix in Supplement 1).15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66 Compared with placebo, numbers needed to treat to prevent 1 person from returning to any drinking were 11 (95% CI, 1-32; 20 trials; n = 6380) for acamprosate and 18 (95% CI, 4-32; 16 trials; n = 2347) for oral naltrexone (50 mg/d), respectively. There was no significant difference in return to heavy drinking between acamprosate and placebo (RR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.05; P = .69; range, 41.9%-81.5% with acamprosate, 45.8%-82.9% with placebo). Compared with placebo, oral naltrexone (50 mg/d) was associated with a statistically significant improvement in return to heavy drinking (RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.72-0.90; P < .001; range, 14.3%-94.6% with naltrexone, 29.7%-93.5% with placebo) with a number needed to treat of 11 (95% CI, 5-41; 19 trials; n = 2875). Compared with placebo, injectable naltrexone was not associated with lower rates of return to any drinking (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90-1.03; P = .14; 2 trials; n = 939; range, 82.3%-93.5% with naltrexone, 89.8%-94.7% with placebo) or return to heavy drinking (RR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.82-1.21; P = .09; 2 trials; n = 615; range, 59.2%-77.2% with naltrexone, 52.7%-84.1% with placebo). Compared with placebo, injectable naltrexone was associated with greater reduction in percentage of drinking days (WMD, −4.99; 95% CI, −9.49 to −0.49; P = .23; 2 trials; n = 467) and percentage of heavy drinking days (WMD, −4.7; 95% CI, −8.6 to −0.73; P = .80; 3 trials; n = 956). Data from 3 RCTs that included 622 participants did not show an association of disulfiram compared with placebo for preventing return to any drinking (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.90-1.17; P = .28; range, 22.7%-81.2% with disulfiram, 34.4%-88.1% with placebo) (Table).

Table. Summary of Findings and Strength of Evidence From Trials Assessing Efficacy of Medications With at Least Low Strength of Evidence for Benefit for Alcohol Use Disordera.

| Acamprosate | Baclofen | Disulfiram | Gabapentin | Naltrexone | Topiramate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 mg/d, oral | 100 mg/d, oral | Injection | Any dose | ||||||

| Return to any drinking | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 20 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 25 | 1 |

| No. of participants | 6380 | 995 | 622 | 522 | 2347 | 946 | 939 | 4604 | 106 |

| Results effect size (95% CI) | RR, 0.88 (0.83-0.93) | RR, 0.83 (0.70-0.98) | RR, 1.03 (0.90-1.17) | RR, 0.92 (0.83-1.02) | RR, 0.93 (0.87-0.99) | RR, 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | RR, 0.96 (0.90-1.03) | RR, 0.95 (0.92-0.99) | Topiramate, 53.8%; placebo, 72.2% |

| Number needed to treat (95% CI)c | 11 (1-32) | 18 (4-32) | |||||||

| Strength of evidence | Moderate | Low | Low (no effect) | Low | Moderate | Low (no effect) | Low (no effect) | Moderate | Insufficient |

| Return to heavy drinking | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 7 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 27 | 1 |

| No. of participants | 2496 | 483 | 0 | 522 | 3170 | 858 | 615 | 4645 | 170 |

| Results effect size (95% CI) | RR, 0.99 (0.94-1.05) | RR, 0.92 (0.80-1.06) | RR, 0.90 (0.82-0.98) | RR, 0.81 (0.72-0.90) | RR, 0.93 (0.84-1.01) | RR, 1.00 (0.82-1.21) | RR, 0.86 (0.80-0.93) | Topiramate, 10%; placebo, 14% | |

| Number needed to treat (95% CI)c | 11 (5-41) | ||||||||

| Strength of evidence | Moderate (no effect) | Low (no effect) | Insufficient | Low | Moderate | Low (no effect) | Low (no effect) | Moderate | Insufficient |

| Percentage of drinking days | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 14 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 15 | 3 | 2 | 24d | 8 |

| No. of participants | 4916 | 714 | 290 | 112 | 1992 | 1023 | 467 | 4021 | 1080 |

| Results effect size (95% CI)b | WMD, −8.3 (−12.2 to −4.4) | WMD, −5.55 (−18.79 to 7.69) | No significant difference | No significant difference | WMD, −5.1 (−7.16 to −3.04) | WMD, −2.3 (−5.60 to 0.99) | WMD, −4.99 (−9.49 to 0.49) | WMD, −4.51 (−6.26 to −2.77) | WMD, −7.2 (−14.3 to −0.1) |

| Strength of evidence | Moderate | Low (no effect) | Insufficient | Insufficient | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Percentage of heavy drinking days | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 2 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 9 |

| No. of participants | 123 | 1112 | 0 | 600 | 624 | 423 | 956 | 2167 | 1210 |

| Results effect size (95% CI)b | WMD, −3.4 (−6.45 to 5.86) | WMD, −2.16 (−7.34 to 3.02) | No significant difference | WMD, −4.3 (−7.60 to −0.91) | WMD, −3.1 (−5.8 to −0.3) | WMD, −4.68 (−8.63 to −0.73) | WMD, −3.92 (−5.86 to −1.97) | WMD, −6.2 (−10.9 to −1.4) | |

| Strength of evidence | Insufficient | Low (no effect) | Insufficient | Low (no effect) | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Drinks per drinking day | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 7 |

| No. of participants | 139 | 146 | 0 | 428 | 1018 | 240 | 0 | 2011 | 922 |

| Results effect size (95% CI)b | WMD, 0.6 (−1.43 to 2.64) | WMD, 0.85 (−2.23 to 3.93) | No significant difference | WMD, −0.49 (−0.92 to −0.06) | WMD, 1.9 (−1.5 to 5.2) | WMD, −0.85 (−1.44 to −0.26) | WMD, −2.0 (−3.1 to −1.0) | ||

| Strength of evidence | Insufficient | Low (no effect) | Insufficient | Low (no effect) | Low | Insufficient | Insufficient | Low | Moderate |

| Motor vehicle crashes or injuries | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 0e | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||

| No. of participants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 541 | |||

| Results effect size (95% CI)b | Reduced risk | ||||||||

| Strength of evidence | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | Low | |||

| Quality of life or function | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | |||

| No. of participants | 612f | 384g | 0 | 0 | 1844h | 118i | |||

| Results effect size (95% CI)b | No significant differencej | No significant difference | Some conflicting resultsk | No significant difference | |||||

| Strength of evidence | Insufficient | Low (no effect) | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | Low (no effect) | |||

| Mortality | |||||||||

| No. of studies | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | |||

| No. of participants | 2677 | 660 | 0 | 0 | 1738 | 507 | |||

| Results effect size (95% CI)b | 7 events (acamprosate) vs 6 events (placebo) | 8 baclofen vs 3 placebo | 1 event (naltrexone) vs 2 events (placebo) | Not reported | |||||

| Strength of evidence | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient | |||

Abbreviations: RR, risk ratio; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Blank cells indicate data not applicable. Strength of evidence was not rated for naltrexone by dose. Heavy drinking days was defined as ≥4 drinks/d for women and ≥5 drinks/d for men.

Negative effect sizes favor intervention over placebo/control.

Lack of entry for number needed to treat indicates that the relative risk (95% CI) was not statistically significant, so the investigators did not calculate a number needed to treat or the effect measure was not one that allows direct calculation of number needed to treat (eg, WMD).

One study contained 2 treatment groups included in the meta-analysis.79

Results were not reported for each treatment group separately, but there were no clinically significant differences across treatment groups.

Quality of life and functioning were assessed with the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) and 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) version 2 physical and mental health scores.

Quality of life and functioning were assessed with the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).

Each trial used a different measure to assess quality of life and functioning, including the Short Inventory of Problems, SF-36, WHOQOL, SF-12 version 2 physical and mental health scores, Drinker Inventory of Consequences, and SF-12.

Quality of life was assessed with the SF-36.

Results were not reported for each treatment group separately, but there were no clinically significant differences across treatment groups.

One study rated as having unclear risk of bias reported that 1 patient in the placebo group died by “accident.” No other details on the cause or nature of the accident were provided.44 That study also reported 1 injury in the acamprosate group and 2 in the placebo group. Another study, rated as having high risk of bias, reported a “traffic accident” in the acamprosate group.80

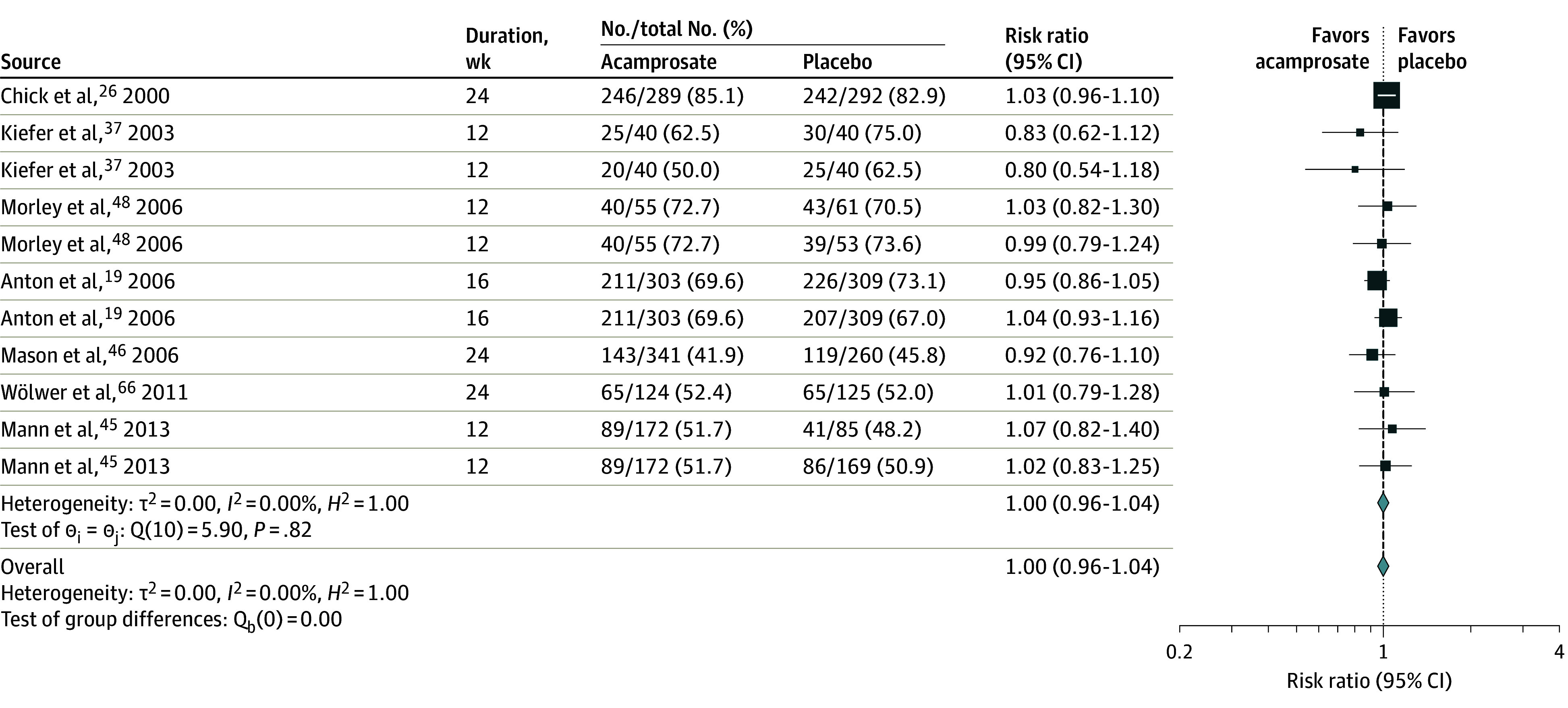

Figure 2. Return to Any Drinking, Acamprosate vs Placebo.

Figure 3. Return to Any Drinking, Disulfiram vs Placebo.

Multiple comparisons within publications are presented separately.

Figure 4. Return to Any Drinking, Naltrexone vs Placebo.

“Overall” refers to pooled estimate for all forms of naltrexone (50 mg/d oral, 100 mg/d oral, and injection).

Figure 5. Return to Heavy Drinking, Acamprosate vs Placebo.

Heavy drinking is defined as ≥4 drinks/d for women and ≥5 drinks/d for men. Multiple comparisons within publications are presented separately.

Figure 6. Return to Heavy Drinking, Naltrexone vs Placebo.

“Overall” refers to pooled estimate for all forms of naltrexone (50 mg/d oral, 100 mg/d oral, and injection). Heavy drinking is defined as ≥4 drinks/d for women and ≥5 drinks/d for men.

Among medications without an FDA indication for alcohol use disorder treatment, compared with placebo, topiramate was associated with statistically significant improvement in the weighted mean of absolute percentage of drinking days (WMD, −7.2; 95% CI, −14.3 to −0.1; P = .14; range, 5.5%-62.4% with topiramate, 6.4%-70.9%), percentage of heavy drinking days (WMD, −6.2; 95% CI, −10.9 to −1.4; P = .32; range, 2.3%-43.8% with topiramate, 5.3%-51.8% with placebo), and number of drinks per drinking day (WMD, −2.0; 95% CI, −3.1 to −1.0; P = .19; range, 1.2-6.5 with topiramate, 4.0-8.8 with placebo). These findings were associated with moderate strength of evidence. Of 13 double-blind placebo-controlled RCTs that included 1607 participants, compared with placebo, baclofen was associated with significantly lower rates of return to any drinking (RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.98; P < .001; range, 28.6%-92.4% with baclofen, 53.2%-89.9% with placebo). Because of imprecision of the effect estimate and inconsistency of results, baclofen data were graded as having low strength of evidence. Compared with placebo, gabapentin was not significantly associated with lower rates of return to any drinking (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83-1.02: P = .08; range, 79.5-86.1 with gabapentin, 88.2-95.9 with placebo) or with significant reduction in return to heavy drinking (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.98; P = .75; range, 63.4-75.9 with gabapentin, 77.6-87.0 with placebo), but both results had low strength of evidence and only 3 clinical trials reported these outcomes.

A meta-analysis of 4 RCTs including 1141 participants that directly compared acamprosate with naltrexone19,37,45,48 found no statistically significant difference between the 2 medications for improvement in alcohol use outcomes consisting of return to any drinking (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.96-1.10; P = .57; range, 75.0-80.5 with acamprosate, 65.0-83.0 with naltrexone; 3 trials; n = 800) or return to heavy drinking (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.93-1.11; P = .65; range, 50.0-72.7 with acamprosate, 50.9-73.6 with naltrexone; 4 trials; n = 1141).

Health Outcomes

There was insufficient evidence from RCTs to assess whether treatment with most medications was associated with improved health outcomes. Outcomes such as motor vehicle crashes, injuries, quality of life, function, and mortality were infrequently reported in the included studies (Table).

Adverse Effects

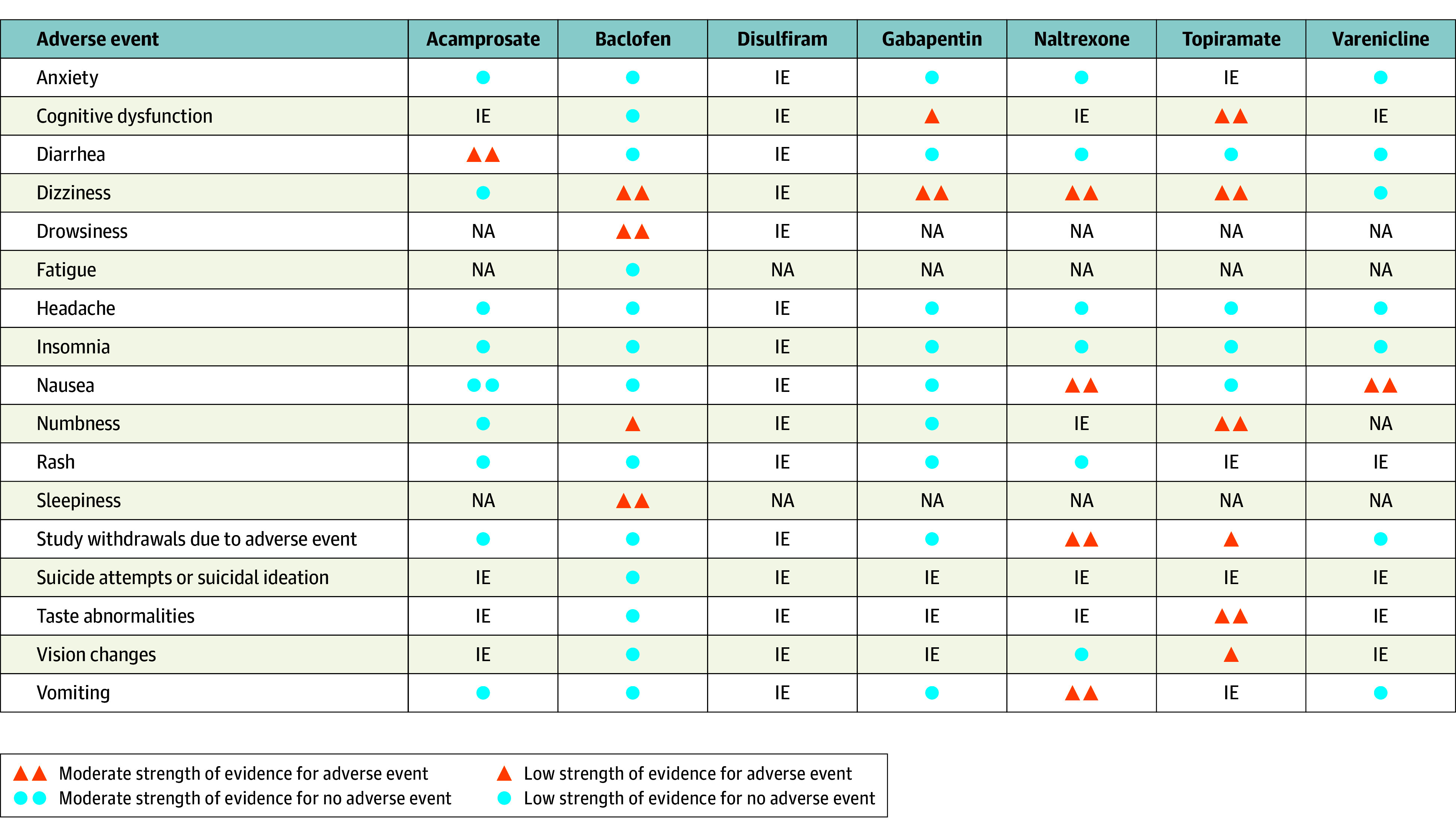

Adverse event data were often not collected using standardized measures, and methods for systematically capturing adverse events were often not reported (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Summary of Strength-of-Evidence Assessments for Harms Outcomes.

IE indicates insufficient evidence; NA, not assessed. This figure includes all drugs with a rating of at least low strength of evidence for adverse events for at least 1 outcome. All doses of naltrexone were assessed together.

Among medications with at least some (low) strength of evidence for benefit in any outcome, compared with placebo, dizziness was the most common mild adverse effect across medications and was reported with naltrexone (RR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.47-2.69; P = .37; range, 2.9%-34.8% with naltrexone, 0.0%-20.6% with placebo), baclofen (RR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.40-2.55; P = .40; range, 4.8%-30.2% with baclofen, 0.0%-22.8% with placebo), topiramate (RR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.39-3.78; P = .65; range, 0.0%-28.0% with topiramate, 1.9%-10.7% with placebo), and gabapentin (RR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.24-2.32; P = .83; range, 6.5%-7.8% with gabapentin, 3.8%-6.0% with placebo). Compared with placebo, any gastrointestinal distress was more common for acamprosate (diarrhea: RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.27-1.97; P = .03; range, 3.0%-63.7% with acamprosate, 1.6%-64.9% with placebo) and naltrexone (nausea: RR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.51-1.98; P = .19; range, 2.5%-57.6% with naltrexone, 0.0%-47.1% with placebo; vomiting: RR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.23-1.91; P = .79; range, 0.0%-25.6% with naltrexone, 0.0%-23.4% with placebo). Compared with placebo, baclofen was associated with higher rates of drowsiness (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.15-1.86; P = .28; range, 6.3%-50.0% with baclofen, 9.4%-32.6% with placebo), numbness (RR, 7.78; 95% CI, 1.42-42.56; P = .48; range, 7.1%-12.6% with baclofen, 0.0%-1.1% with placebo), and sleepiness (RR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.11-2.97; P = .77; range, 2.4%-36.2% with baclofen, 0.0%-17.7% with placebo). Compared with placebo, topiramate was associated with higher risks of many adverse events, including paresthesias (RR, 3.08; 95% CI, 2.11-4.49; P = .06; range, 0.0%-57.3% with topiramate, 1.9%-29.4% with placebo), taste abnormalities (RR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.70-5.34; P = .04; range, 15.1%-53.3% with topiramate, 4.8%-31.3% with placebo), and cognitive dysfunction (RR, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.58-3.55; P = .48; range, 12.6%-23.9% with topiramate, 5.4%-11.3% with placebo). Compared with placebo, gabapentin was associated with cognitive dysfunction (RR, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.51-5.06; P = .37; range, 5.9%-25.5% with gabapentin, 5.7%-17% with placebo) and dizziness (RR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.24-2.32; P = .83; range, 21.2%-56.8% with gabapentin, 13.7%-32.6% with placebo). In direct comparisons of acamprosate and oral naltrexone in RCTs, patients treated with acamprosate had lower rates of nausea (RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.35-0.88; P = .11; range, 3.8%-23.8% with acamprosate, 2.5%-55.6% with naltrexone) and vomiting (RR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.39-0.93; P = .88; range, 8.9%-11.1% with acamprosate, 14.6%-22.2% with naltrexone) compared with those treated with naltrexone.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis that included 118 clinical trials, the highest strength of evidence for treatment of alcohol use disorder was available for acamprosate and oral naltrexone (50 mg/d). Randomized clinical trials that directly compared naltrexone, 50 mg/d, with acamprosate did not consistently established superiority of either medication. Studies of naltrexone had moderate strength of evidence for reducing return to any drinking, return to heavy drinking, percentage of drinking days, and percentage of heavy drinking days at the 50-mg/d oral dose compared with placebo. Fewer data were available for the 100-mg/d oral and injectable doses. Studies of acamprosate showed moderate strength of evidence for significant reduction in return to any drinking and reduction in drinking days compared with placebo. Acamprosate was not associated with benefit for return to heavy drinking (moderate strength of evidence).

Oral naltrexone is more convenient than acamprosate, requiring a single daily dose, whereas acamprosate is typically prescribed as 2 tablets administered 3 times daily. Acamprosate is contraindicated for people with severe kidney impairment and requires dose adjustments for moderate kidney impairment. Oral naltrexone is contraindicated for patients with acute hepatitis or liver failure and for those using opioids or who have anticipated need for opioids. Naltrexone can precipitate severe withdrawal for patients dependent on opioid medications.

Disulfiram has been FDA approved for alcohol use disorder since the 1950s. However, relatively limited evidence exists to support the efficacy of disulfiram compared with placebo for preventing return to any drinking or other alcohol consumption outcomes. Four RCTs of disulfiram have been published that were not eligible for this review because of their trial designs and comparisons.67,68,69,70 These small trials (with 15 or fewer disulfiram-treated patients in each) had limitations that included a small sample size and inability to distinguish between benefits from disulfiram and benefits of counseling or benefits from therapeutic relationships with the investigative team.71,72

Among medications without FDA approval for alcohol use disorder, studies of topiramate compared with placebo had moderate strength of evidence for significant reductions in percentage of drinking days, percentage of heavy drinking days, and drinks per drinking days. However, topiramate was associated with adverse effects that included cognitive dysfunction, dizziness, numbness and/or tingling, and taste abnormalities. Studies of baclofen and gabapentin had low strength of evidence for benefit in at least 1 outcome. Evidence was largely insufficient or low for benefit on health outcomes, including quality of life, motor vehicle crashes, and mortality.

Alcohol use disorder is associated with numerous health problems, including but not limited to hypertension, heart disease, stroke, cognitive impairment, sleep problems, depression, anxiety, peripheral neuropathy, gastritis and gastric ulcers, liver disease including cirrhosis, pancreatitis, osteoporosis, anemia, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, and several types of cancer.73,74 Excessive alcohol consumption is also associated with higher rates of homicide, suicide, motor vehicle crashes and deaths, sexual violence, domestic violence, and drownings.75

Applicability of Findings

Using DSM-5 criteria, most participants in the included studies likely had moderate to severe alcohol use disorder. Thus, applicability of the findings to people with mild alcohol use disorder is uncertain. The mean age of participants was typically between 40 and 49 years, with only 21 studies enrolling younger or older populations. Thus, it is uncertain whether the medications have similar efficacy for older (eg, aged ≥65 years) or younger (eg, aged in their 20s) people. Of the 70 studies that provided data on race and sex, most (n = 63) included a majority of White male participants, and none specified sex other than male or female. Because 100 of 118 clinical trials studied drug therapy combined with a nonmedication treatment (such as counseling), results reflect benefits from a combination of medication and cotherapy compared with placebo and cotherapy.

Of the 5 studies of acamprosate that were conducted in the United States, most reported no significant benefit either for return to any drinking or return to heavy drinking. Clinical trials conducted in the United States recruited patients largely through advertisements, while 15 of 22 clinical trials in other countries recruited participants from inpatient settings, where patients may have undergone alcohol withdrawal and medications may have been initiated before discharge. Patients recruited in the clinical trials conducted in the United States may have represented a more general population with a larger range of alcohol use at baseline. Thus, the lack of efficacy in US-based trials for acamprosate may reflect differences in patient characteristics and differences in the health care systems compared with clinical trials from other countries.

Most studies required patients to abstain for at least a few days before initiating medication, and the medications were generally recommended for maintenance of abstinence. Acamprosate and injectable naltrexone are FDA approved only for use in patients who have established abstinence, although the duration of required abstinence is not established. Three studies enrolling patients who were not yet abstinent reported reduction in heavy drinking with naltrexone compared with placebo30,76 or acamprosate compared with placebo.33

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, clinical trials with less than 12 weeks of follow-up from the time of medication initiation were excluded. Second, the meta-analysis combined studies of participants with diagnoses of both alcohol dependence and depression and studies of participants without both alcohol dependence and depression. Third, studies may have selectively reported outcomes. Fourth, long-term information about adverse effects was not available. Fifth, for adverse event outcomes, due to small sample sizes and relatively small numbers of events, evidence was often insufficient to determine whether adverse event outcomes were increased. Sixth, in some included studies, less than 100% of participants had alcohol use disorder. Specifically, 3 studies reported that less than 90% of participants had alcohol use disorder.24,77,78

Conclusions

In conjunction with psychosocial interventions, these findings support the use of oral naltrexone, 50 mg/d, and acamprosate as first-line pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder.

Educational Objective: To identify the key insights or developments described in this article.

-

In this meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder, the authors excluded studies evaluating treatment for less than 12 weeks. Why?

Drinking behavior does not change suddenly but tends to “ramp up” and “ramp down,” and shorter time frames limit determination of marginal changes around thresholds for heavy drinking.

Evaluation of health outcomes, including injury, quality of life, and mortality, require a minimum of 6 months to gather sufficient numbers for meaningful comparison.

Studies of treatment for less than 12 weeks may yield misleading results because fluctuations in drinking behavior may be mistaken for efficacy.

-

Among medications with an US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indication for alcohol use disorder (acamprosate, disulfiram, and naltrexone), which were associated with a statistically significant reduction in alcohol consumption?

Acamprosate and naltrexone

Disulfiram only

No medication with an FDA indication for treating patients with alcohol use disorder was associated with efficacy.

-

What conclusions did the authors reach regarding alcohol use treatment and health outcomes including motor vehicle crashes, injury, quality of life, and mortality?

Any treatment for alcohol use disorder, compared with no pharmacologic treatment, was associated with lower risk of traumatic injury and death.

Available trials provided insufficient evidence to assess whether treatment was associated with better health outcomes.

Only acamprosate reduced overall mortality at 12 weeks.

eTable 1. Definitions of Unhealthy Alcohol Use (Sometimes Previously Referred to as Alcohol Misuse)

eTable 2. Medications That Are FDA Approved for Treating Adults With Alcohol Dependence

eTable 3. Questions for the Full Technical Report and This Manuscript

eTable 4. Characteristics of Included Studies

eTable 5. Summary of Findings and Strength of Evidence for Efficacy of Medications Used Off-Label or Those Under Investigation

eAppendix. Reference List for Figures 2 Through 5

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Deaths from excessive alcohol use in the United States. Accessed January 23, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/features/excessive-alcohol-deaths.html

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Published 2021. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . National Survey on Drug Use and Health, detailed tables. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-nsduh-detailed-tables

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Published 2022. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt39443/2021NSDUHFFRRev010323.pdf

- 5.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for Adults with Alcohol-Use Disorders in Outpatient Settings. Published May 13, 2014. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/alcohol-misuse-drug-therapy/research [PubMed]

- 6.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS: Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47095/ [PubMed]

- 9.Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, et al. Assessing the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies in Systematic Reviews of Health Care Interventions. Published 2012. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ [PubMed]

- 10.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions—Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Effective Health-Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(5):513-523. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmadi J, Ahmadi N. A double blind, placebo-controlled study of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Ger J Psychiatry. 2002;5(4):85-89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ClinicalTrials.gov . ALK21-014: efficacy and safety of Medisorb naltrexone (Vivitrol) after enforced abstinence. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00501631

- 17.Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P, et al. Naltrexone combined with either cognitive behavioral or motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(4):349-357. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000172071.81258.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, Latham PK, Malcolm RJ, Dias JK. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1758-1764. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. ; COMBINE Study Research Group . Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balldin J, Berglund M, Borg S, et al. A 6-month controlled naltrexone study: combined effect with cognitive behavioral therapy in outpatient treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(7):1142-1149. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000075548.83053.A9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baltieri DA, De Andrade AG. Acamprosate in alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled efficacy study in a standard clinical setting. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(1):136-139. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baltieri DA, Daró FR, Ribeiro PL, de Andrade AG. Comparing topiramate with naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2008;103(12):2035-2044. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger L, Fisher M, Brondino M, et al. Efficacy of acamprosate for alcohol dependence in a family medicine setting in the United States: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(4):668-674. doi: 10.1111/acer.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besson J, Aeby F, Kasas A, Lehert P, Potgieter A. Combined efficacy of acamprosate and disulfiram in the treatment of alcoholism: a controlled study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(3):573-579. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown ES, Carmody TJ, Schmitz JM, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of naltrexone in outpatients with bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(11):1863-1869. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01024.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chick J, Anton R, Checinski K, et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35(6):587-593. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.6.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chick J, Howlett H, Morgan MY, Ritson B. United Kingdom Multicentre Acamprosate Study (UKMAS): a 6-month prospective study of acamprosate versus placebo in preventing relapse after withdrawal from alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35(2):176-187. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuller RK, Branchey L, Brightwell DR, et al. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism: a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. JAMA. 1986;256(11):1449-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03380110055026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuller RK, Roth HP. Disulfiram for the treatment of alcoholism: an evaluation in 128 men. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(6):901-904. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-6-901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, et al. ; Vivitrex Study Group . Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617-1625. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gastpar M, Bonnet U, Böning J, et al. Lack of efficacy of naltrexone in the prevention of alcohol relapse: results from a German multicenter study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(6):592-598. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200212000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geerlings PJ, Ansoms C, Van Den Brink W. Acamprosate and prevention of relapse in alcoholics: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study in out-patient alcoholics in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. Eur Addict Res. 1997;3(3):129-137. doi: 10.1159/000259166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gual A, Lehert P. Acamprosate during and after acute alcohol withdrawal: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in Spain. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36(5):413-418. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.5.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guardia J, Caso C, Arias F, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol-dependence disorder: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(9):1381-1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higuchi S; Japanese Acamprosate Study Group . Efficacy of acamprosate for the treatment of alcohol dependence long after recovery from withdrawal syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in Japan (Sunrise Study). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):181-188. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang MC, Chen CH, Yu JM, Chen CC. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence in Taiwan. Addict Biol. 2005;10(3):289-292. doi: 10.1080/13556210500223504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiefer F, Jahn H, Tarnaske T, et al. Comparing and combining naltrexone and acamprosate in relapse prevention of alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(1):92-99. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Killeen TK, Brady KT, Gold PB, et al. Effectiveness of naltrexone in a community treatment program. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(11):1710-1717. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000145688.30448.2C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kranzler HR, Wesson DR, Billot L; Drug Abuse Sciences Naltrexone Depot Study Group . Naltrexone depot for treatment of alcohol dependence: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(7):1051-1059. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000130804.08397.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krystal JH, Cramer JA, Krol WF, Kirk GF, Rosenheck RA; Veterans Affairs Naltrexone Cooperative Study 425 Group . Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1734-1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latt NC, Jurd S, Houseman J, Wutzke SE. Naltrexone in alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial of effectiveness in a standard clinical setting. Med J Aust. 2002;176(11):530-534. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee A, Tan S, Lim D, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of male alcoholics—an effectiveness study in Singapore. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2001;20(2):193-199. doi: 10.1080/09595230120058579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lhuintre JP, Daoust M, Moore ND, et al. Ability of calcium bis acetyl homotaurine, a GABA agonist, to prevent relapse in weaned alcoholics. Lancet. 1985;1(8436):1014-1016. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91615-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lhuintre JP, Moore N, Tran G, et al. Acamprosate appears to decrease alcohol intake in weaned alcoholics. Alcohol Alcohol. 1990;25(6):613-622. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a045057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mann K, Lemenager T, Hoffmann S, et al. ; PREDICT Study Team . Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled pharmacotherapy trial in alcoholism conducted in Germany and comparison with the US COMBINE study. Addict Biol. 2013;18(6):937-946. doi: 10.1111/adb.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mason BJ, Goodman AM, Chabac S, Lehert P. Effect of oral acamprosate on abstinence in patients with alcohol dependence in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial: the role of patient motivation. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(5):383-393. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Swift RM, et al. Naltrexone and cue exposure with coping and communication skills training for alcoholics: treatment process and 1-year outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(11):1634-1647. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morley KC, Teesson M, Reid SC, et al. Naltrexone versus acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a multi-centre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 2006;101(10):1451-1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01555.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morris PL, Hopwood M, Whelan G, Gardiner J, Drummond E. Naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2001;96(11):1565-1573. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115654.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Schottenfeld RS, Meyer RE, Rounsaville B. Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(11):881-887. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110045007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Malley SS, Robin RW, Levenson AL, et al. Naltrexone alone and with sertraline for the treatment of alcohol dependence in Alaska natives and non-natives residing in rural settings: a randomized controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(7):1271-1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00682.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Malley SS, Sinha R, Grilo CM, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioral coping skills therapy for the treatment of alcohol drinking and eating disorder features in alcohol-dependent women: a randomized controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(4):625-634. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of naltrexone in the context of different levels of psychosocial intervention. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(7):1299-1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00698.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oslin D, Liberto JG, O’Brien J, Krois S, Norbeck J. Naltrexone as an adjunctive treatment for older patients with alcohol dependence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5(4):324-332. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199700540-0000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paille FM, Guelfi JD, Perkins AC, Royer RJ, Steru L, Parot P. Double-blind randomized multicentre trial of acamprosate in maintaining abstinence from alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30(2):239-247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pelc I, Le Bon O, Verbanck P, Lehert P, Opsomer L. Calciumacetylhomotaurinate for maintaining abstinence in weaned alcoholic patients: a placebo-controlled double-blind multi-centre study. In: Naranjo CA, Sellers EM, eds. Novel Pharmacological Interventions for Alcoholism. Springer-Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pelc I, Verbanck P, Le Bon O, Gavrilovic M, Lion K, Lehert P. Efficacy and safety of acamprosate in the treatment of detoxified alcohol-dependent patients: a 90-day placebo-controlled dose-finding study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:73-77. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.1.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petrakis IL, Poling J, Levinson C, Nich C, Carroll K, Rounsaville B; VA New England VISN I MIRECC Study Group . Naltrexone and disulfiram in patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(10):1128-1137. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pettinati HM, Oslin DW, Kampman KM, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial combining sertraline and naltrexone for treating co-occurring depression and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):668-675. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08060852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Poldrugo F. Acamprosate treatment in a long-term community-based alcohol rehabilitation programme. Addiction. 1997;92(11):1537-1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb02873.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sass H, Soyka M, Mann K, Zieglgänsberger W. Relapse prevention by acamprosate: results from a placebo-controlled study on alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(8):673-680. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830080023006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tempesta E, Janiri L, Bignamini A, Chabac S, Potgieter A. Acamprosate and relapse prevention in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a placebo-controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35(2):202-209. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.2.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Volpicelli JR, Clay KL, Watson NT, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism: predicting response to naltrexone. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(suppl 7):39-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Volpicelli JR, Rhines KC, Rhines JS, Volpicelli LA, Alterman AI, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone and alcohol dependence: role of subject compliance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(8):737-742. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200071010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitworth AB, Fischer F, Lesch OM, et al. Comparison of acamprosate and placebo in long-term treatment of alcohol dependence. Lancet. 1996;347(9013):1438-1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91682-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wölwer W, Frommann N, Jänner M, et al. The effects of combined acamprosate and integrative behaviour therapy in the outpatient treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118(2-3):417-422. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Azrin NH, Sisson RW, Meyers R, Godley M. Alcoholism treatment by disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1982;13(2):105-112. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(82)90050-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azrin NH. Improvements in the community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther. 1976;14(5):339-348. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(76)90021-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liebson IA, Tommasello A, Bigelow GE. A behavioral treatment of alcoholic methadone patients. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(3):342-344. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-3-342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gerrein JR, Rosenberg CM, Manohar V. Disulfiram maintenance in outpatient treatment of alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28(6):798-802. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750360034004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saitz R. Medications for alcohol use disorders. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jonas DE, Feltner C, Garbutt JC. Medications for alcohol use disorders—reply. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1351. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med. 2004;38(5):613-619. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492-501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y. Alcohol-attributable fraction for injury in the U.S. general population: data from the 2005 National Alcohol Survey. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(4):535-538. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kranzler HR, Armeli S, Tennen H, et al. Targeted naltrexone for early problem drinkers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(3):294-304. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000084030.22282.6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cook RL, Zhou Z, Miguez MJ, et al. Reduction in drinking was associated with improved clinical outcomes in women with HIV infection and unhealthy alcohol use: results from a randomized clinical trial of oral naltrexone versus placebo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(8):1790-1800. doi: 10.1111/acer.14130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Edelman EJ, Moore BA, Holt SR, et al. Efficacy of extended-release naltrexone on HIV-related and drinking outcomes among HIV-positive patients: a randomized-controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(1):211-221. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2241-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Foa EB, Yusko DA, McLean CP, et al. Concurrent naltrexone and prolonged exposure therapy for patients with comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(5):488-495. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laaksonen E, Koski-Jännes A, Salaspuro M, Ahtinen H, Alho H. A randomized, multicentre, open-label, comparative trial of disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43(1):53-61. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Definitions of Unhealthy Alcohol Use (Sometimes Previously Referred to as Alcohol Misuse)

eTable 2. Medications That Are FDA Approved for Treating Adults With Alcohol Dependence

eTable 3. Questions for the Full Technical Report and This Manuscript

eTable 4. Characteristics of Included Studies

eTable 5. Summary of Findings and Strength of Evidence for Efficacy of Medications Used Off-Label or Those Under Investigation

eAppendix. Reference List for Figures 2 Through 5

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement