Abstract

Terminal oligopyrimidine motif-containing mRNAs (TOPs) encode all ribosomal proteins in mammals and are regulated to tune ribosome synthesis to cell state. Previous studies implicate LARP1 in 40S- or 80S-ribosome complexes that repress and stabilize TOPs. However, a mechanistic understanding of how LARP1 and TOPs interact with these complexes to coordinate TOP outcomes is lacking. Here, we show that LARP1 senses the cellular supply of ribosomes by directly binding non-translating ribosomal subunits. Cryo-EM structures reveal a previously uncharacterized domain of LARP1 bound to and occluding the 40S mRNA channel. Free cytosolic ribosomes induce sequestration of TOPs in repressed 80S-LARP1-TOP complexes independent of alterations in mTOR signaling. Together, this work demonstrates a general ribosome-sensing function of LARP1 that allows it to tune ribosome protein synthesis to cellular demand.

One-Sentence Summary:

LARP1 directly binds free ribosomal subunits to repress TOP mRNAs

Terminal oligopyrimidine motif-containing mRNAs (TOPs) begin with a +1 cytidine nucleotide followed by 4-15 pyrimidines and encode all ribosomal proteins in mammals (1). For decades, it has been known that TOP translation is acutely regulated to coordinate ribosomal protein synthesis with demand across diverse cellular contexts (2–11) in a manner wholly dependent on the TOP motif at the 5’-end (12–14). These findings ultimately led to the identification of La-related protein 1 (LARP1) – a multi-domain evolutionarily-conserved RNA binding protein (15) – as a key regulator that directly binds to the TOP motif (16–19).

LARP1 binds TOPs under conditions of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition, leading to translational repression, as well as stabilization and polyA-tail lengthening of the mRNA (16, 19–22). Despite some literature suggesting mTOR components could be dispensable for TOP control (23–25), mTOR is thought of as the quintessential regulator of TOP translation (16, 26–28) in part through direct phosphorylation of LARP1 (19, 29–33). Interestingly, the LARP1-TOP complex itself is thought to be associated with ribosomes as LARP1 and TOPs sediment with 40S ribosome complexes (TOP-40S) during normal growth conditions (34) or 80S ribosome complexes (TOP-80S) during mTOR inhibition (27, 31, 35). One recent report argued that the TOP-80S reflects single-ribosome (monosomal) translation that protects TOPs and permits their rapid reactivation (35). A recent CLIP-seq study defined contacts between LARP1 and 18S rRNA of the 40S ribosomal subunit near the mRNA channel (36). Despite these mechanistic insights, the function, regulation, and biophysical nature of the interaction of LARP1 and TOPs with 40S and 80S ribosomes is not entirely clear.

Here, we define the association of the LARP1-TOP complex with ribosomes. Through biochemical and structural analysis, we demonstrate that the TOP-80S comprises non-translating, weakly-associated 40S and 60S subunits that bind directly to LARP1 and not to the TOP. We show that free ribosomal subunits bind directly to LARP1 and repress TOPs independent of changes in mTOR signaling previously thought to be fundamental to TOP regulation. Our observations provide molecular insights into how LARP1 senses free ribosomes to tune the synthesis of ribosomal proteins to cellular demand.

A system to study TOP association with 40S and 80S ribosomes

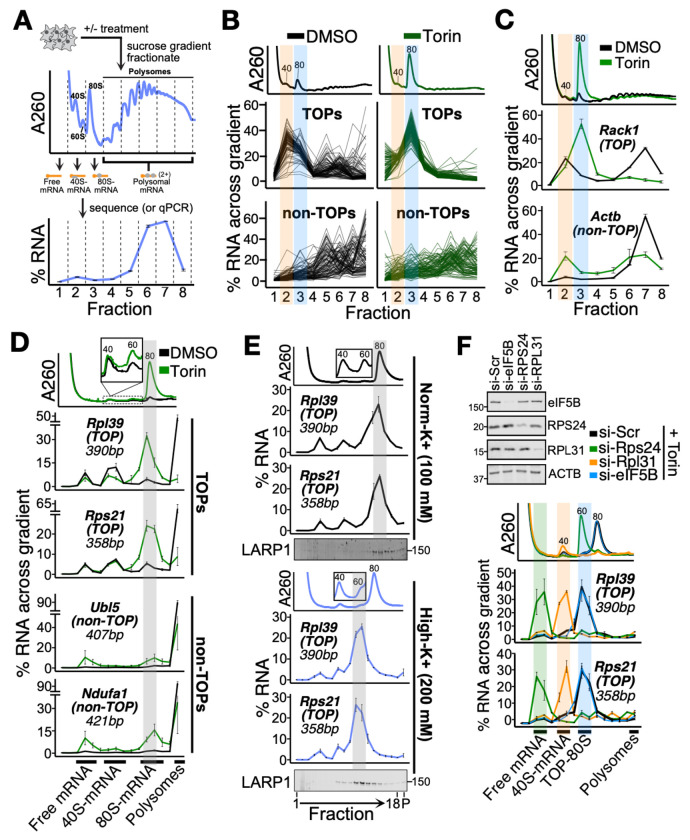

To study the TOP-80S, we treated cells with either DMSO (control) or the mTOR inhibitor, Torin1 (37), fractionated cell lysates across a sucrose gradient and performed nanopore sequencing of mRNAs isolated from each fraction (Fig. 1A). Normalization to spike-in mRNAs enabled us to quantify the percent distribution of each mRNA species in each fraction across the gradient. In DMSO, TOPs sediment in a bimodal distribution (Fig. 1B): one population sediments in sub-polysomal fractions, representing translationally-repressed mRNAs associated with 40S subunits (4, 21, 34), and the other population sediments in polysomal fractions, representing highly-translated mRNAs. In contrast, non-TOPs are more uniformly distributed across polysomal fractions, indicative of active translation. Upon Torin1 treatment, TOPs redistribute en masse to the 80S fraction (Fig. 1B). In contrast, non-TOPs shift to lighter fractions but remain distributed across the gradient, consistent with a modest global decrease in their translation upon Torin1 treatment (Fig. 1B). These data agree with previous reports showing stronger translational repression of TOPs compared to non-TOPs with Torin1 treatment (20, 28). Importantly, qPCR for individual TOPs recapitulated the same redistribution from the 40S and polysomal fractions to the 80S fraction upon Torin1 treatment (Fig. 1C and fig. S1A). These data therefore define a robust system for interrogating the sedimentation of TOPs with 40S and 80S ribosomes.

Fig. 1. Characterization of the TOP-80S complex.

(A) Schematic of experimental setup. Cell lysates were separated by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose gradient and fractionated. The amount of each RNA species in each fraction is presented as a percentage of the whole across the gradient as shown here for a representative mRNA. (B) U266B1 cells were treated with DMSO or 300 nM Torin1 for 1 h, lysed, and processed as shown in (A) followed by PCR-cDNA nanopore sequencing. A260 traces for each treatment are shown in upper panels. Each line represents the fractional distribution of a single mRNA across the gradient. Top: 96 annotated TOPs are plotted +/− Torin1. Bottom: A random sample of 96 non-TOPs are plotted +/− Torin1. Orange and blue highlights correspond to the TOP-40S and TOP-80S, respectively. (C) HEK293T cells were treated with DMSO or 300 nM Torin1 for 1 h and processed as shown in (A) followed by qPCR against genes of interest. Orange and blue highlights correspond to the TOP-40S and TOP-80S, respectively. (D) HEK293T cells were treated with DMSO or 300 nM Torin1 for 1 h and lysates fractionated on 15-35% sucrose gradients containing 100 mM KOAc followed by qPCR against genes of interest. Gray highlight corresponds to the TOP-80S. (E) HEK293T cells were treated with 300 nM Torin1 for 1 h and lysates fractionated along 15-35% sucrose gradients containing either 100 mM KOAc (Norm-K+) or 200 mM KOAc (High-K+) followed by qPCR against genes of interest. Gray highlight corresponds to the TOP-80S. Western blots against LARP1 from the same samples are presented below qPCR traces. (F) HEK293T cells were treated with siRNAs targeting scrambled (si-Scr), Rps24, Rpl31, or eIF5B followed by 300 nM Torin1 for 1 h. Western blots demonstrating knockdown efficiency are shown. Lysates were fractionated along 15-35% sucrose gradients containing 200 mM KOAc followed by qPCR against genes of interest. Green, orange, and blue highlights correspond to free mRNA, TOP-40S, and TOP-80S, respectively. For (C-F), data are shown from one experiment representative of two biological replicates. For qPCR plots, error bars reflect the SD of 2-4 technical replicates from one experiment.

TOP-80S ribosomes are weakly-associated and non-translating

To better resolve the messenger ribonucleoprotein (mRNP) complexes in the sub-polysomal fractions, we ultracentrifuged cellular lysates over lower percentage sucrose gradients, fractionated finely, and probed for size-matched, endogenous mRNAs whose annotated size of < 500 bp should minimally affect the sedimentation of mRNPs. Hereafter we refer to these as “spread” gradients. This protocol allowed us to identify three distinct populations of TOPs which sediment in the sub-polysomal region of the gradient: 1) Free mRNA, 2) TOP-40S and 3) TOP-80S (Fig. 1D). We also extracted the material that sedimented to the bottom of the ultracentrifuge tube. This allows us to determine the proportion of each mRNA species in polysomes and therefore account for the full cytoplasmic expression of a given mRNA species.

As seen previously, after Torin1 treatment TOPs (Rpl39 and Rps21) exit polysomes and sediment with 80S monosomes (Fig. 1D). In contrast, non-TOPs (Ubl5 and Ndufa1) are more resistant to Torin1 treatment: a substantial portion remains in polysomes and a moderate portion sediments with the free mRNA or 80S peaks. In accordance with previous studies (21, 35), the TOP-80S fails to form in LARP1-KO cells upon Torin1 treatment, confirming that LARP1 is a critical component of this complex (fig. S1B).

Because of the high resolution afforded by these spread gradients, we were able to resolve a subtle leftward shift of TOPs in the 80S region compared to non-TOPs (Fig. 1D). We wondered whether the ribosome species associating with TOPs might be qualitatively different from an elongating 80S monosome. We treated cells with Torin1 and then compared the sedimentation of TOPs in gradients containing 100 mM (“norm-K+”) or 200 mM (“high-K+”) KOAc. While TOPs sediment with the leftmost edge of the monosome peak in norm-K+ gradients, they sediment even further left (closer to the 60S distribution) in high-K+ gradients (Fig. 1E). This finding is reminiscent of early work showing that high KOAc causes vacant 40S and 60S couples (but not mRNA-engaged ribosomes) to split as they travel through the gradient, leading to intermediate migrations of the dissociating 40S and 60S components (38–40) (see supplementary text on “TOP-80S shift in high-K+ gradients”). Importantly, LARP1 protein undergoes the same redistribution in high-K+ gradients, landing in the TOP-80S left-shifted peak (Fig. 1E). Titrating KOAc even higher to 500 mM causes TOPs to sediment still further left, likely reflecting earlier dissociation in the gradient (fig. S1C). Based on these data, we propose that the TOP-80S contains vacant 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits which are not directly engaged in translating the bound mRNA.

To directly evaluate whether both 40S and 60S subunits are present in the TOP-80S, we treated cells with Torin1 following siRNA-mediated knockdown of RPS24 (a 40S protein) or RPL31 (a 60S protein). These knockdowns impacted the overall abundance of 40S and 60S subunits as previously observed for other ribosomal protein knockdowns (34). Importantly, si-RPS24 resulted in migration of TOPs entirely in the free mRNA fraction (with no ribosomal subunits bound) while si-RPL31 resulted in migration of TOPs entirely in the TOP-40S fraction (Fig. 1F). These data confirm that the TOP-80S contains both a 40S and a 60S subunit. Importantly, these data also demonstrate that the 40S joins first and directly to the TOP because knockdown of the 40S prevents both subunits from joining while knockdown of the 60S prevents only 60S joining.

To test our model that the TOP-80S does not contain actively elongating monosomes, we knocked down eIF5B, an initiation factor which mediates 60S joining at AUG start codons (41). In untreated cells, eIF5B knockdown caused an increase in the monosome peak confirming that the knockdown was sufficient to globally inhibit translation initiation (fig. S1D). Strikingly, eIF5B knockdown did not impact the migration or abundance of the TOP-80S under Torin1 treatment (Fig. 1F). These data demonstrate that 60S joining to the TOP-80S is not mediated by canonical mechanisms (eIF5B) at an AUG start codon. Instead, consistent with the high-K+ data (Fig. 1E), these data suggest that the TOP-80S is composed of 40S and 60S subunits bound to one another by more general inter-subunit interactions independent of translation initiation. Surprisingly, we also noticed that eIF5B knockdown strongly induced formation of the TOP-80S in untreated cells, phenocopying what we had observed with Torin1 (fig. S1D). This provides further evidence that 60S joining to LARP1-TOP complexes is not occurring by canonical mechanisms. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the TOP-80S contains a TOP mRNA complexed with LARP1, a 40S subunit and a weakly-associated 60S subunit, and is likely non-translating.

Cryo-EM structures reveal LARP1 bound in the mRNA channel of the 40S subunit

Intrigued by the association of LARP1 and TOPs with 40S subunits, we solved a single-particle cryo-EM structure of mature human 40S ribosome complexes with LARP1 at 3.2 Å resolution, obtained from an in vivo immunoprecipitation using PYM1 (a known ribosome-associated factor (42)) as purification bait (Figs. 2A–2B, figs. S2A, S3A, S4A, and table S1). The resolved density maps allowed us to construct a de novo model of the 40S ribosome and unambiguously assign and fit AlphaFold (43) predicted models for amino acids 660-724 of the long-isoform annotation of LARP1 (ENSEMBL LARP1-204) (44) (see supplementary texts on “Validation of LARP1 structure from PYM1 IP” and “LARP1 isoforms”). This assignment of LARP1 was further confirmed by a second cryo-EM structure which we obtained using LARP1 as purification bait (Fig. 2C and figs. S2B, S4B). Based on these two structures we were able to define a previously uncharacterized domain of LARP1 spanning residues 650-730 between the La (polyA-binding (45–47)) and DM15 (m7G-TOP-binding (17, 18)) domains, which we call the Ribosome Binding Region (RBR; Fig. 2A). Importantly, while LARP1 is found in an identical position in both structures, the superior structure obtained from the PYM1 sample is used for discussion in the remainder of the paper.

Fig. 2. Cryo-EM analysis of the interaction between LARP1 and the 40S ribosome.

(A) Schematic showing the domain arrangement of LARP1 protein. (B) Three different views of cryo-EM structure of the human LARP1-40S ribosome complex (from PYM1 sample). (C) Back view of cryo-EM structure of the LARP1-40S ribosome complex (from LARP1 sample). (D) Zoom-in of the RBR of LARP1 bound within the mRNA channel of the 40S ribosomal subunit. References to specific figure panels are annotated with the corresponding letter circled in red. (E) LARP1 residues 660-665 bind to the decoding center of the 40S ribosome. Key residues interacting with uS3 (blue) and 18S rRNA (yellow) are shown. (F-I) Detailed schematics of LARP1 residues 666-694; key residues interacting with 18S rRNA helices 1 and 18 (yellow, F), uS3 (blue, G), uS5 (green, H) and eS30 (pink, I) are shown. (J) LARP1 residues 708-724 interacting with 18S rRNA (yellow), uS3 (blue) and eS17 (light green) are shown. For (D-J), residues and nucleobases are annotated and stacking interactions are indicated by black bidirectional arrows. (K) LARP1-KO cells (HEK293T) were transfected with plasmids expressing either FLAG peptide alone (Mock), LARP1, or LARP1-RBRmut followed by treatment with 300 nM Torin1 for 1 h. The domain map detailing mutated residues in the RBRmut (top left) and western blots showing LARP1 expression (bottom left) are shown. Lysates were fractionated along 15-35% sucrose gradients containing 200 mM KOAc followed by qPCR against genes of interest. Gray highlight corresponds to the TOP-80S. Data are shown from a single experiment representative of two biological replicates. For qPCR data, error bars reflect the SD of 2-4 technical replicates from one experiment. (L) LARP1-KO cells (HEK293T) were treated as described in (K). Protein was extracted from the gradient fractions and western blotted for FLAG-tagged LARP1.

Only the RBR of LARP1 could be observed in our structure and extends from the inter-subunit side to the solvent side of the 40S subunit through the mRNA entry channel (Fig. 2B–2C and figs. S4A–S4B). The RBR can be subdivided into three segments of defined density separated by short stretches of unresolved density (Fig. 2D and figs. S4C–S4E). The first segment of residues 660-694 traverses from the decoding center (DC) through the mRNA channel (Fig. 2D and fig. S4C). The N-terminus of this segment is located within the DC where residue H665 stacks with base C1698 (C1397 in E. coli) of the 18S rRNA which plays an important role during tRNA decoding (Fig. 2E) (48). This localization agrees with PAR-CLIP data identifying contacts between LARP1 and nucleotides 1698-1702 of the 18S rRNA (36). The subsequent protein helix (residues 667-694) passes through the mRNA channel using basic residues to interact with 18S rRNA helices 1 and 18 (e.g. R668 with h1 and K670 with h18; Fig. 2F). Deeper in the channel the same helix makes hydrophobic contacts with ribosomal proteins uS3, uS5, and eS30: Y685 of LARP1 stacks with R117 and R124 of uS3 (Fig. 2G); Y686, L683 and I679 of LARP1 contact the hydrophobic surface of uS5 (Fig. 2H); and W691 of LARP1 stacks with F49 of eS30 (Fig. 2I). Following this helix, LARP1 becomes disordered and the second segment of the RBR emerges and includes residues 708-724 which make hydrophobic contacts with the C-terminal tail of uS3 and with the N-terminal domain of eS17 (Fig. 2J and fig. S4D). Finally, an unknown density on the surface of RACK1 is plausibly a third segment of the RBR (fig. S4E). However, we were unable to confidently assign this region due to the lack of structural features and low local resolution.

The cryo-EM structure of LARP1 bound to 40S subunits within the DC and mRNA channel immediately suggests that the complex is translationally inactive. Indeed, superimposing the mRNA density from a solved structure of a scanning 48S preinitiation complex (PIC) (49) reveals that the LARP1 RBR directly clashes with mRNA density in the channel and would occlude mRNA binding (fig. S5A). We further speculate that LARP1 binding to the DC could hinder the association of eIF1A, a critical initiation factor (fig. S5B) (50). Finally, the LARP1 RBR occupies a similar position in the mRNA channel to known translation repressors SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 (51) (fig. S5C) and human SERBP1 (52) (fig. S5D). These observations suggest these factors may employ a conserved mechanism for translation inhibition.

To validate the LARP1-40S structure we introduced nine alanine point mutations into full-length LARP1 at important contact sites with the 40S subunit (“LARP1-RBRmut”) (Fig. 2K). We transfected plasmids expressing either FLAG peptide alone (Mock), FLAG-tagged wild-type LARP1 (LARP1), or FLAG-tagged LARP1-RBRmut (RBRmut) into LARP1-KO cells and treated with Torin1 to evaluate formation of the TOP-80S. Importantly, both the LARP1 and RBRmut constructs are equally expressed and stable as determined by western blot (Fig. 2K). While the TOP-40S and TOP-80S complexes readily form in cells expressing exogenous LARP1, these complexes fail to form in cells expressing either Mock or the RBRmut; these data establish that the RBR of LARP1 is required for the formation of TOP-40S and TOP-80S (Fig. 2K). By comparison, the sedimentation profile of a non-TOP mRNA, Ubl5, is largely unperturbed in these different backgrounds (Fig. 2K). Furthermore, while wild-type LARP1 protein sediments in the same distribution as the TOP-80S in Torin1-treated cells, the RBRmut protein sediments with free mRNA. These data suggest that the RBRmut LARP1 protein can still bind mRNAs but can no longer bind ribosomes (Fig. 2L). Collectively, these data show that the TOP-40S and TOP-80S are composed of non-translating ribosomal subunits, wherein the 40S subunit is directly bound to LARP1 and not to the TOP itself.

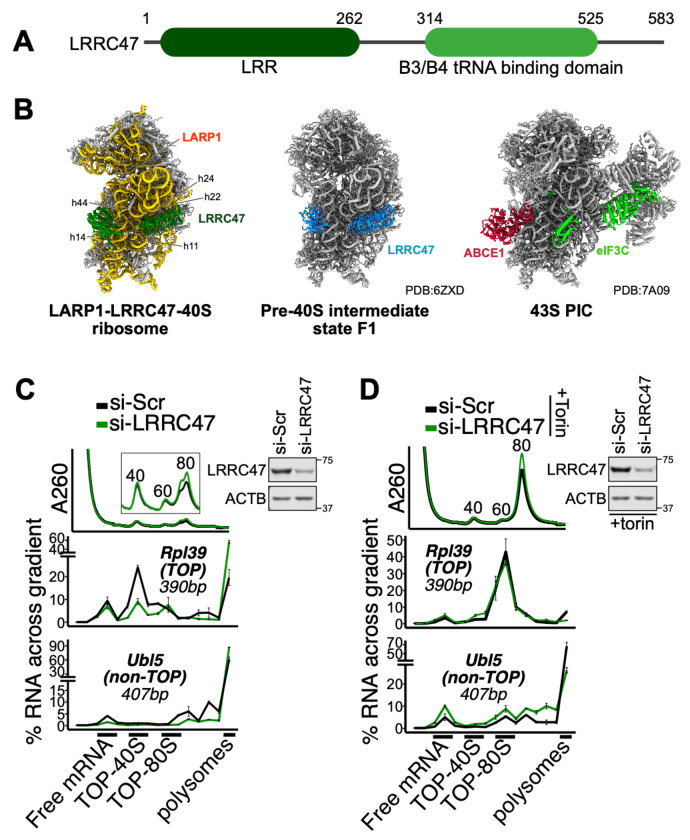

LRRC47 is a potential new player in regulating TOP translation

In addition to the LARP1-40S ribosome structure, we obtained a LARP1-LRRC47-40S structure from the same in vivo PYM1 immunoprecipitation at 3.4 Å resolution (figs. S2A, S3B, and S4F). We were able to construct a de novo model of the 40S ribosome and unambiguously assign and fit the AlphaFold (43) predicted models for LRRC47. LRRC47 has an N-terminal leucine rich repeat (LRR) domain and C-terminal B3/B4 tRNA-binding domain (Fig. 3A) and was previously captured on late cytoplasmic pre-40S biogenesis intermediates (53). In our LARP1-LRRC47-40S structure, LARP1 is in an identical position as seen for the LARP1-40S structure (figs. S4A, S4B, and S4F) and LRRC47 is positioned identically to what was observed in the pre-40S intermediate state F1 (Fig. 3B) (53). The LRR domain of LRRC47 binds h11, h22, and h24 and its B3/B4 tRNA binding domain binds h5, h14, and h44 of the 18S rRNA (Fig. 3B) (53). The LRR domain would spatially clash with eIF3C and the B3/B4 tRNA binding domain would spatially clash with ABCE1 (53, 54) (Fig. 3B), immediately suggesting that LRRC47 would interfere with assembly of the 43S pre-initiation complex (PIC). These observations are consistent with the model proposed above wherein LARP1-bound 40S complexes are translationally inactive.

Fig 3. LRRC47 promotes the TOP-40S.

(A) Domain map of LRRC47 showing LRR (dark green) and B3/B4 tRNA-binding (light green) domains. (B) Structural comparison of the LARP1-LRRC47-40S ribosome (left), pre-40S ribosome state F1 (middle) and 43S pre-initiation complex (right). LARP1 (tomato red), LRRC47 (green and blue), ABCE1 (red) and eIF3C (light green) are shown. PIC: pre-initiation complex. (C) HEK293T cells were treated with siRNAs targeting scrambled (si-Scr) or LRRC47 and lysates fractionated along 15-35% sucrose gradients containing 200 mM KOAc followed by qPCR against genes of interest. Western blots showing knockdown efficiency are shown. (D) Same setup as in (C) except that cells were treated with 300 nM Torin1 for 1 h prior to lysis. For (C-D), data are shown from a single experiment representative of two biological replicates. For qPCR data, error bars reflect the SD of 2-4 technical replicates from one experiment.

While there is limited information on the biological function of LRRC47, it has been hypothesized to act as an anti-association factor as its position on the 40S would preclude 60S joining (53). We therefore reasoned that LRRC47 might be involved in forming or stabilizing the TOP-40S (34). To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the formation of TOP-40S in cells transfected with scrambled siRNAs or those targeting LRRC47. SiRNA against LRRC47 decreased the abundance of the TOP-40S and increased the proportion of TOPs in polysomes, suggesting that LRRC47 either stabilizes or promotes formation of the TOP-40S under normal growth conditions (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the sedimentation of non-TOPs was largely unperturbed (Fig. 3C). We also evaluated the formation of the TOP-80S in cells treated with Torin1. Knockdown of LRRC47 had no effect on formation of the TOP-80S, suggesting that LRRC47 does not effectively prevent 60S subunit joining to the TOP-40S upon Torin1 treatment (Fig. 3D). Considering that LRRC47 has an unclear role in late-stage 40S biogenesis (53), an enticing possibility is that 60S joining under Torin1 conditions kicks LRRC47 off to serve a role in repressing late stages of ribosome biogenesis.

LARP1 senses free ribosomes to coordinate TOP repression independent of mTOR signaling

The observation that LARP1 binds directly to ribosomes raised the possibility that LARP1 might sense free ribosomes within the cell and couple this function to tuning the translation of TOPs. To test this model, we treated cells with a wide range of conditions broadly known to increase the availability of free ribosomes and probed for formation of the TOP-80S.

Because translational control of TOPs has been extensively studied in the context of mTOR signaling (16, 19–21, 26–28, 31, 35, 55–57), we began by perturbing downstream components of the mTOR signaling pathway. A major outcome of mTOR inhibition is disruption of the eIF4E-eIF4G interaction that is critical to translation initiation (58). As expected, siRNA-mediated knockdown of either eIF4E or eIF4G led to a global decrease in translation initiation as evidenced by an increase in the monosome peak and decrease in polysomes (Fig. 4A). Importantly, neither condition led to an observable change in eIF4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1) phosphorylation (a canonical readout of mTOR signaling (37)) or eIF2S1/eIF2α phosphorylation (a canonical readout of the integrated stress response (ISR) (59)) (Fig. 4A). Nonetheless, both conditions led to a redistribution of TOPs, but not non-TOPs, to the 80S fraction by qPCR, indicating formation of the TOP-80S (Fig. 4A and fig. S6A). Furthermore, the distribution of LARP1 protein across the polysome profile revealed increased sedimentation with the 80S fraction upon eIF4E knockdown, consistent with LARP1 involvement in the TOP-80S (fig. S6B). These data demonstrate that the sequestration of TOPs in the TOP-80S can be decoupled from changes in mTOR signaling.

Fig. 4. TOPs are repressed in 80S complexes independent of changes in mTOR signaling.

(A) HEK293T cells were treated with siRNAs targeting scrambled (si-Scr), eIF4E, or eIF4G and lysates fractionated along 10-50% sucrose gradients followed by qPCR against genes of interest. Western blots showing knockdown efficiency and for proteins of interest are shown. (B) Identical to (A) except with siRNAs targeting scrambled (si-Scr), eIF4A1/2, eIF3B, or eIF2S1. (C) HEK293T cells were treated with siRNAs targeting scrambled (si-Scr), eIF4E, eIF4G, eIF4A1/2, eIF3B, or eIF2S1 and lysates fractionated along 15-35% sucrose gradients containing 200 mM KOAc followed by qPCR against genes of interest. (D) Identical to (A) except cells were treated with Torin1 (300 nM, 1 h), Silvestrol (30 nM, 1 h), Sodium arsenite (Arsenite; 100 μM, 1 h), or Puromycin (250 μM, 30 min). (E) Identical to (C) except cells were treated with Torin1 (300 nM, 1 h), Silvestrol (30 nM, 1 h), Sodium arsenite (Arsenite; 100 μM, 1 h), or Puromycin (250 μM, 30 min). For (A-E), gray highlights correspond to the TOP-80S. Data are shown from one experiment representative of two biological replicates (A, B, D) or one biological replicate (C, E). For qPCR data, error bars reflect the SD of 2-4 technical replicates from one experiment. (F) Phos-tag gel for LARP1 following identical treatments to those described throughout Figure 4. Data are shown from one experiment representative of two biological replicates. (G) Model: LARP1 senses increases in free 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits within the cell which induces binding and repression of TOPs. Ribosomes bind directly to the LARP1 RBR which is located between the DM15 domain (blue) and La domain (green).

Since eIF4E and eIF4G knockdown should both reduce association of eIF4E with the m7G-cap of mRNAs (60, 61), it seemed plausible that these knockdowns might simply allow LARP1 to better compete with eIF4E for the m7G-cap of TOPs. We therefore wondered whether formation of the TOP-80S might simply reflect increased accessibility or a more general phenomenon caused by increased free ribosomes. To this end, we next depleted diverse components of the translation initiation machinery, but in this case those not directly affecting cap-binding by eIF4E. As expected, knockdown of eIF4A1/eIF4A2 (dual knockdown), eIF3B, or eIF2S1/eIF2α all substantially increased 80S abundance, confirming that global translation initiation was decreased (Fig. 4B). Again, we observed little-to-no decrease in mTOR signaling in any of these conditions. Interestingly, we did note modest upregulation of mTOR activity with siRNA against eIF2S1/eIF2 that likely results from negative crosstalk between the eIF2 and mTOR signaling pathways (Fig. 4B) (62, 63). Remarkably, as with eIF4E and eIF4G depletion, treatment with each siRNA led to the collective redistribution of TOPs, but not non-TOPs, to the 80S fraction (Fig. 4B and fig. S7A), suggesting that increased availability of free ribosomes is sufficient to induce formation of the TOP-80S.

To formally establish the identity of the TOP-80S in these conditions, we repeated the initiation factor knockdowns in spread, high-K+ gradients. Importantly, in all conditions, the TOP-80S sediments distinctly upstream of the canonical 80S (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that the TOP-80S under all of these conditions corresponds to non-translating, loosely-associated 40S and 60S subunits which are bound to LARP1 and not to the TOP itself. In contrast, all knockdowns induced a small but appreciable proportion of non-TOP mRNA to sediment with the canonical 80S, providing a nice marker for non-TOP mRNAs which are still translated by a single, elongating monosome (Fig. 4C).

As a final test of the hypothesis that LARP1 senses free ribosomes, we used pharmacological inhibitors to stress cells and acutely increase the availability of free ribosomes. In addition to Torin1 as a positive control, we treated cells with silvestrol (an eIF4A inhibitor (64)), sodium arsenite (an inducer of eIF2S1/eIF2α-phosphorylation and the ISR (65)), or puromycin (a tyrosyl-tRNA mimetic which releases nascent peptides and triggers dissociation of ribosome subunits from mRNAs (66)). As expected, acute treatments with all compounds (for 1 hour or less) resulted in a marked increase in monosomes (Fig. 4D). While Torin1 induced an almost complete loss of 4EBP1 phosphorylation at T37/T46 and S65, there was no observable change in mTOR signaling detected with any other agents (Fig. 4D). As expected, sodium arsenite potently activated the ISR, as observable by increased eIF2S1/eIF2α phosphorylation and modest translational activation of ATF4 mRNA by qPCR (Fig. 4D and fig. S7B). As with the initiation factor knockdown experiments, treatment with each of these pharmacological agents led to a redistribution of TOPs, but not non-TOPs, to the 80S fraction (Fig. 4D and fig. S7B). Further experiments again showed that the TOP-80S sedimented distinctly upstream of the translating 80S in spread, high-K+ gradients (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these data demonstrate that LARP1-mediated translational repression of the TOPs occurs dynamically in response to acute increases in the availability of free ribosomes.

A prevailing model implicates LARP1 phosphorylation at multiple residues as a key mediator of TOP regulation (19, 25, 29–33). Given that none of the pharmacological agents impacted mTOR signaling to 4EBP1, we wondered whether LARP1 phosphorylation status might also be unaffected. We queried LARP1 phosphorylation using Phos-tag gels in which phosphorylated proteins run more slowly than non-phosphorylated proteins. Only Torin1 induced an obvious downshift in the migration pattern of LARP1 by Phos-tag gel while all other treatments that also lead to the formation of the TOP-80S did not lead to an obvious downshift (Fig. 4F). These data indicate that phosphorylation of LARP1 is not appreciably decreased under these regimes and collectively argue that phosphorylated LARP1 can recruit ribosomes and TOPs to repress their translation.

Discussion

We have defined molecular features of interactions between LARP1, TOPs and 40S and 80S ribosomes. Our biochemistry and structural approaches identified the RBR of LARP1 which directly binds 40S subunits in a manner that prevents mRNA binding and thus translation. In order to form the TOP-80S, the RBR binds a 40S subunit while the DM15 domain simultaneously binds a TOP, and the 60S joins through normal subunit interface interactions that are salt-sensitive. This view is supported by the observation that mutations in either the RBR or DM15 domains preclude TOP-80S formation (our data and (35)). Through these coordinated binding events, we propose that LARP1 can directly sense free ribosomes and tune the repression of TOPs accordingly (Model Fig. 4G).

LARP1 exists at an abundance of ~105 copies per mammalian cell (67), roughly stoichiometric with mRNA (68) but at least an order of magnitude less abundant than ribosomes (69). As such, this sensing mechanism seems well-suited to coordination of TOP repression rather than to sequestration of inactive ribosomes. Importantly, our data show that LARP1-ribosome sensing can occur independent of observable phosphorylation changes in 4EBP1 and LARP1. We acknowledge, however, that signaling downstream of mTOR and other kinases likely provides additional layers of regulation that determine how effectively these repressive complexes form (19, 25, 29–33). For example, it is possible that in certain cell types or regimes, 4EBP1 phosphorylation may play more critical roles in providing access to the TOP m7G-cap (28, 57).

While our data do not allow us to assign an order of events for complex formation, we are inclined toward a model in which free 40S subunits first bind LARP1 and this induces binding to TOPs. An exciting possibility would be if ribosome binding induces a conformational change that increases DM15 affinity for the TOP motif. Importantly, our data also do not allow us to claim an essential role for 60S joining to form the TOP-80S, although formation of this complex is robust and ubiquitous in all conditions tested. Formation of this complex may simply reflect the binding equilibrium in the cell that occurs in the presence of an excess of both 40S and 60S subunits. Alternatively, given the established role of LARP1 in stabilizing TOPs (16, 34, 57, 70), 60S joining could drive stabilization by mass action (Fig. 4G), allowing for more TOPs to be recruited into the most stable state.

The ribosome-sensing function of LARP1 uncovered here seems likely to be implicated in cell states in which free ribosome concentrations are altered or dynamically regulated such as cell differentiation (71), changes in cell size (72, 73), and disease (74, 75). Importantly, LARP1 expression is elevated and associated with adverse prognosis in several cancers including cervical (76), non-small cell lung (76, 77), hepatocellular (78), colorectal (79), and ovarian cancers (80). Considering the varying demands on ribosome number in each of these diseases and cell states, LARP1-ribosome sensing could serve as a general mechanism to tune synthesis of ribosomal proteins to the availability of free ribosomes across a diverse array of healthy and diseased mammalian cell contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Green, Cheng, and Timp Labs for helpful comments and suggestions during preparation of this manuscript. We thank Paul Hook for help with Nanopore sequencing analysis. We thank Carson Thoreen for providing LARP1-KO cell lines (HEK293T) and LARP1 expression plasmids.

Funding

Howard Hughes Medical Institute HHMI_GREEN (RG)

National Institutes of Health (NCI) grant F30CA260910 (JAS)

National Institutes of Health MSTP program grant T32GM136577 (JAS and KLS)

National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 32371350 (JC)

Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission grants 22410712400, 22ZR1413600 (JC)

National Institutes of Health (NHGRI) grant HG010538 (WT)

Footnotes

Competing interests

RG is on the scientific advisory board of Alltrna, Initial Therapeutics and Arrakis Pharmaceuticals and serves as a consultant for Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Brystol-Myers Squibb (Celgene), Monta Rosa Therapeutics, and Flagship Pioneering. RG previously served on the scientific advisory board at Moderna. WT has two patents (8,748,091 and 8,394,584) licensed to ONT and received reimbursement for travel, accommodation, and/or conference fees to speak at events organized by ONT.

Data and materials availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information. Nanopore sequencing data is deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE246077). Code for analyzing sequencing data and qPCR data, and for generating plots has been posted on GitHub at repository 2023_Saba_Larp1 (https://github.com/jakesaba/2023_Saba_LARP1). Any additional data, code, or materials used in this article will be made available upon request. Cryo-EM structural data will be deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and Protein Data Bank (PDB) to be released upon article publication.

References and Notes:

- 1.Meyuhas O., Kahan T., The race to decipher the top secrets of TOP mRNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1849, 801–811 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DePhilip R. M., Rudert W. A., Lieberman I., Preferential stimulation of ribosomal protein synthesis by insulin and in the absence of ribosomal and messenger ribonucleic acid formation. Biochemistry. 19, 1662–1669 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geyer P. K., Meyuhas O., Perry R. P., Johnson L. F., Regulation of ribosomal protein mRNA content and translation in growth-stimulated mouse fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 685–693 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyuhas O., Thompson E. A. Jr, Perry R. P., Glucocorticoids selectively inhibit translation of ribosomal protein mRNAs in P1798 lymphosarcoma cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 2691–2699 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aloni R., Peleg D., Meyuhas O., Selective translational control and nonspecific posttranscriptional regulation of ribosomal protein gene expression during development and regeneration of rat liver. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 2203–2212 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loreni F., Thomas G., Amaldi F., Transcription inhibitors stimulate translation of 5’ TOP mRNAs through activation of S6 kinase and the mTOR/FRAP signalling pathway. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 6594–6601 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolovich M., Lerer T., Bolkier Y., Cohen H., Meyuhas O., Lithium can relieve translational repression of TOP mRNAs elicited by various blocks along the cell cycle in a glycogen synthase kinase-3-and S6-kinase-independent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5336–5342 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuxworth W. J. Jr, Shiraishi H., Moschella P. C., Yamane K., McDermott P. J., Kuppuswamy D., Translational activation of 5’-TOP mRNA in pressure overload myocardium. Basic Res. Cardiol. 103, 41–53 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jouffe C., Cretenet G., Symul L., Martin E., Atger F., Naef F., Gachon F., The circadian clock coordinates ribosome biogenesis. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001455 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miloslavski R., Cohen E., Avraham A., Iluz Y., Hayouka Z., Kasir J., Mudhasani R., Jones S. N., Cybulski N., Rüegg M. A., Larsson O., Gandin V., Rajakumar A., Topisirovic I., Meyuhas O., Oxygen sufficiency controls TOP mRNA translation via the TSC-Rheb-mTOR pathway in a 4E-BP-independent manner. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 255–266 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cottrell K. A., Chiou R. C., Weber J. D., Upregulation of 5’-terminal oligopyrimidine mRNA translation upon loss of the ARF tumor suppressor. Sci. Rep. 10, 22276 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy S., Avni D., Hariharan N., Perry R. P., Meyuhas O., Oligopyrimidine tract at the 5’ end of mammalian ribosomal protein mRNAs is required for their translational control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 88 (1991), pp. 3319–3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond M. L., Merrick W., Bowman L. H., Sequences mediating the translation of mouse S16 ribosomal protein mRNA during myoblast differentiation and in vitro and possible control points for the in vitro translation. Genes Dev. 5, 1723–1736 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biberman Y., Meyuhas O., Substitution of just five nucleotides at and around the transcription start site of rat beta-actin promoter is sufficient to render the resulting transcript a subject for translational control. FEBS Lett. 405, 333–336 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bousquet-Antonelli C., Deragon J.-M., A comprehensive analysis of the La-motif protein superfamily. RNA. 15, 750–764 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonseca B. D., Zakaria C., Jia J.-J., Graber T. E., Svitkin Y., Tahmasebi S., Healy D., Hoang H.-D., Jensen J. M., Diao I. T., Lussier A., Dajadian C., Padmanabhan N., Wang W., Matta-Camacho E., Hearnden J., Smith E. M., Tsukumo Y., Yanagiya A., Morita M., Petroulakis E., González J. L., Hernández G., Alain T., Damgaard C. K., La-related Protein 1 (LARP1) Represses Terminal Oligopyrimidine (TOP) mRNA Translation Downstream of mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1). J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15996–16020 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lahr R. M., Mack S. M., Héroux A., Blagden S. P., Bousquet-Antonelli C., Deragon J.-M., Berman A. J., The La-related protein 1-specific domain repurposes HEAT-like repeats to directly bind a 5’TOP sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 8077–8088 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahr R. M., Fonseca B. D., Ciotti G. E., Al-Ashtal H. A., Jia J.-J., Niklaus M. R., Blagden S. P., Alain T., Berman A. J., La-related protein 1 (LARP1) binds the mRNA cap, blocking eIF4F assembly on TOP mRNAs. Elife. 6, e24146 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philippe L., Vasseur J.-J., Debart F., Thoreen C. C., La-related protein 1 (LARP1) repression of TOP mRNA translation is mediated through its cap-binding domain and controlled by an adjacent regulatory region. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 1457–1469 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philippe L., van den Elzen A. M. G., Watson M. J., Thoreen C. C., Global analysis of LARP1 translation targets reveals tunable and dynamic features of 5’ TOP motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 5319–5328 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuentes P., Pelletier J., Martinez-Herráez C., Diez-Obrero V., Iannizzotto F., Rubio T., Garcia-Cajide M., Menoyo S., Moreno V., Salazar R., Tauler A., Gentilella A., The 40S-LARP1 complex reprograms the cellular translatome upon mTOR inhibition to preserve the protein synthetic capacity. Sci Adv. 7, eabg9275 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogami K., Oishi Y., Sakamoto K., Okumura M., Yamagishi R., Inoue T., Hibino M., Nogimori T., Yamaguchi N., Furutachi K., Hosoda N., Inagaki H., Hoshino S.-I., mTOR- and LARP1-dependent regulation of TOP mRNA poly(A) tail and ribosome loading. Cell Rep. 41, 111548 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patursky-Polischuk I., Stolovich-Rain M., Hausner-Hanochi M., Kasir J., Cybulski N., Avruch J., Rüegg M. A., Hall M. N., Meyuhas O., The TSC-mTOR Pathway Mediates Translational Activation of TOP mRNAs by Insulin Largely in a Raptor-or Rictor-Independent Manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 1670 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li B. B., Qian C., Gameiro P. A., Liu C.-C., Jiang T., Roberts T. M., Struhl K., Zhao J. J., Targeted profiling of RNA translation reveals mTOR-4EBP1/2-independent translation regulation of mRNAs encoding ribosomal proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115, E9325–E9332 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haneke K., Schott J., Lindner D., Hollensen A. K., Damgaard C. K., Mongis C., Knop M., Palm W., Ruggieri A., Stoecklin G., CDK1 couples proliferation with protein synthesis. J. Cell Biol. 219 (2020), doi: 10.1083/jcb.201906147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jefferies H. B., Reinhard C., Kozma S. C., Thomas G., Rapamycin selectively represses translation of the “polypyrimidine tract” mRNA family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91, 4441–4445 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terada N., Patel H. R., Takase K., Kohno K., Nairn A. C., Gelfand E. W., Rapamycin selectively inhibits translation of mRNAs encoding elongation factors and ribosomal proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91, 11477–11481 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thoreen C. C., Chantranupong L., Keys H. R., Wang T., Gray N. S., Sabatini D. M., A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature. 485 (2012), pp. 109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu Y., Yoon S.-O., Poulogiannis G., Yang Q., Ma X. M., Villén J., Kubica N., Hoffman G. R., Cantley L. C., Gygi S. P., Blenis J., Phosphoproteomic Analysis Identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 Substrate That Negatively Regulates Insulin Signaling. Science. 332, 1322–1326 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang S. A., Pacold M. E., Cervantes C. L., Lim D., Lou H. J., Ottina K., Gray N. S., Turk B. E., Yaffe M. B., Sabatini D. M., mTORC1 phosphorylation sites encode their sensitivity to starvation and rapamycin. Science. 341, 1236566 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong S., Freeberg M. A., Han T., Kamath A., Yao Y., Fukuda T., Suzuki T., Kim J. K., Inoki K., LARP1 functions as a molecular switch for mTORC1-mediated translation of an essential class of mRNAs. Elife. 6 (2017), doi: 10.7554/eLife.25237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fonseca B. D., Lahr R. M., Damgaard C. K., Alain T., Berman A. J., LARP1 on TOP of ribosome production. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 9, e1480 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia J.-J., Lahr R. M., Solgaard M. T., Moraes B. J., Pointet R., Yang A.-D., Celucci G., Graber T. E., Hoang H.-D., Niklaus M. R., Pena I. A., Hollensen A. K., Smith E. M., Chaker-Margot M., Anton L., Dajadian C., Livingstone M., Hearnden J., Wang X.-D., Yu Y., Maier T., Damgaard C. K., Berman A. J., Alain T., Fonseca B. D., mTORC1 promotes TOP mRNA translation through site-specific phosphorylation of LARP1. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 3461–3489 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gentilella A., Morón-Duran F. D., Fuentes P., Zweig-Rocha G., Riaño-Canalias F., Pelletier J., Ruiz M., Turón G., Castaño J., Tauler A., Bueno C., Menéndez P., Kozma S. C., Thomas G., Autogenous Control of 5’TOP mRNA Stability by 40S Ribosomes. Mol. Cell. 67, 55–70.e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider C., Erhard F., Binotti B., Buchberger A., Vogel J., Fischer U., An unusual mode of baseline translation adjusts cellular protein synthesis capacity to metabolic needs. Cell Rep. 41, 111467 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolin E., Guo J. K., Blanco M. R., Perez A. A., Goronzy I. N., Abdou A. A., Gorhe D., Guttman M., Jovanovic M., SPIDR: a highly multiplexed method for mapping RNA-protein interactions uncovers a potential mechanism for selective translational suppression upon cellular stress. bioRxiv (2023), doi: 10.1101/2023.06.05.543769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thoreen C. C., Kang S. A., Chang J. W., Liu Q., Zhang J., Gao Y., Reichling L. J., Sim T., Sabatini D. M., Gray N. S., An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8023–8032 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Infante A. A., Baierlein R., Pressure-induced dissociation of sedimenting ribosomes: effect on sedimentation patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 68, 1780–1785 (1971). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beller R. J., Lubsen N. H., Effect of polypeptide chain length on dissociation of ribosomal complexes. Biochemistry. 11, 3271–3276 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noll M., Hapke B., Schreier M. H., Noll H., Structural dynamics of bacterial ribosomes. I. Characterization of vacant couples and their relation to complexed ribosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 75, 281–294 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J. H., Pestova T. V., Shin B.-S., Cao C., Choi S. K., Dever T. E., Initiation factor eIF5B catalyzes second GTP-dependent step in eukaryotic translation initiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99, 16689–16694 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diem M. D., Chan C. C., Younis I., Dreyfuss G., PYM binds the cytoplasmic exon-junction complex and ribosomes to enhance translation of spliced mRNAs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 1173–1179 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., Tunyasuvunakool K., Bates R., Žídek A., Potapenko A., Bridgland A., Meyer C., Kohl S. A. A., Ballard A. J., Cowie A., Romera-Paredes B., Nikolov S., Jain R., Adler J., Back T., Petersen S., Reiman D., Clancy E., Zielinski M., Steinegger M., Pacholska M., Berghammer T., Bodenstein S., Silver D., Vinyals O., Senior A. W., Kavukcuoglu K., Kohli P., Hassabis D., Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 596, 583–589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwenzer H., Abdel Mouti M., Neubert P., Morris J., Stockton J., Bonham S., Fellermeyer M., Chettle J., Fischer R., Beggs A. D., Blagden S. P., LARP1 isoform expression in human cancer cell lines. RNA Biol. 18, 237–247 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mattijssen S., Kozlov G., Gaidamakov S., Ranjan A., Fonseca B. D., Gehring K., Maraia R. J., The isolated La-module of LARP1 mediates 3’ poly(A) protection and mRNA stabilization, dependent on its intrinsic PAM2 binding to PABPC1. RNA Biol. 18, 275–289 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozlov G., Mattijssen S., Jiang J., Nyandwi S., Sprules T., Iben J. R., Coon S. L., Gaidamakov S., Noronha A. M., Wilds C. J., Maraia R. J., Gehring K., Structural basis of 3’-end poly(A) RNA recognition by LARP1. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 9534–9547 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Ashtal H. A., Rubottom C. M., Leeper T. C., Berman A. J., The LARP1 La-Module recognizes both ends of TOP mRNAs. RNA Biol. 18, 248–258 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jenner L. B., Demeshkina N., Yusupova G., Yusupov M., Structural aspects of messenger RNA reading frame maintenance by the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 555–560 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brito Querido J., Sokabe M., Kraatz S., Gordiyenko Y., Skehel J. M., Fraser C. S., Ramakrishnan V., Structure of a human 48S translational initiation complex. Science. 369, 1220–1227 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yi S.-H., Petrychenko V., Schliep J. E., Goyal A., Linden A., Chari A., Urlaub H., Stark H., Rodnina M. V., Adio S., Fischer N., Conformational rearrangements upon start codon recognition in human 48S translation initiation complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 5282–5298 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thoms M., Buschauer R., Ameismeier M., Koepke L., Denk T., Hirschenberger M., Kratzat H., Hayn M., Mackens-Kiani T., Cheng J., Straub J. H., Stürzel C. M., Fröhlich T., Berninghausen O., Becker T., Kirchhoff F., Sparrer K. M. J., Beckmann R., Structural basis for translational shutdown and immune evasion by the Nsp1 protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 369, 1249–1255 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wells J. N., Buschauer R., Mackens-Kiani T., Best K., Kratzat H., Berninghausen O., Becker T., Gilbert W., Cheng J., Beckmann R., Structure and function of yeast Lso2 and human CCDC124 bound to hibernating ribosomes. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000780 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ameismeier M., Zemp I., van den Heuvel J., Thoms M., Berninghausen O., Kutay U., Beckmann R., Structural basis for the final steps of human 40S ribosome maturation. Nature. 587, 683–687 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kratzat H., Mackens-Kiani T., Ameismeier M., Potocnjak M., Cheng J., Dacheux E., Namane A., Berninghausen O., Herzog F., Fromont-Racine M., Becker T., Beckmann R., A structural inventory of native ribosomal ABCE1-43S pre-initiation complexes. EMBO J. 40, e105179 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huo Y., Iadevaia V., Yao Z., Kelly I., Cosulich S., Guichard S., Foster L. J., Proud C. G., Stable isotope-labelling analysis of the impact of inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin on protein synthesis. Biochem. J. 444, 141–151 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith E. M., Benbahouche N. E. H., Morris K., Wilczynska A., Gillen S., Schmidt T., Meijer H. A., Jukes-Jones R., Cain K., Jones C., Stoneley M., Waldron J. A., Bell C., Fonseca B. D., Blagden S., Willis A. E., Bushell M., The mTOR regulated RNA-binding protein LARP1 requires PABPC1 for guided mRNA interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 458–478 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hochstoeger T., Papasaikas P., Piskadlo E., Chao J. A., Distinct roles of LARP1 and 4EBP1/2 in regulating translation and stability of 5’TOP mRNAs. bioRxiv (2023), p. 2023.05.22.541712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haghighat A., Mader S., Pause A., Sonenberg N., Repression of cap-dependent translation by 4E-binding protein 1: competition with p220 for binding to eukaryotic initiation factor-4E. EMBO J. 14, 5701–5709 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pakos-Zebrucka K., Koryga I., Mnich K., Ljujic M., Samali A., Gorman A. M., The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 17, 1374–1395 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haghighat A., Sonenberg N., eIF4G dramatically enhances the binding of eIF4E to the mRNA 5’-cap structure. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21677–21680 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yanagiya A., Svitkin Y. V., Shibata S., Mikami S., Imataka H., Sonenberg N., Requirement of RNA binding of mammalian eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI (eIF4GI) for efficient interaction of eIF4E with the mRNA cap. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 1661–1669 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nikonorova I. A., Mirek E. T., Signore C. C., Goudie M. P., Wek R. C., Anthony T. G., Time-resolved analysis of amino acid stress identifies eIF2 phosphorylation as necessary to inhibit mTORC1 activity in liver. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 5005–5015 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Averous J., Lambert-Langlais S., Mesclon F., Carraro V., Parry L., Jousse C., Bruhat A., Maurin A. C., Pierre P., Proud C. G., Fafournoux P., GCN2 contributes to mTORC1 inhibition by leucine deprivation through an ATF4 independent mechanism. Sci. Rep. 6, 27698 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolfe A. L., Singh K., Zhong Y., Drewe P., Rajasekhar V. K., Sanghvi V. R., Mavrakis K. J., Jiang M., Roderick J. E., Van der Meulen J., Schatz J. H., Rodrigo C. M., Zhao C., Rondou P., de Stanchina E., Teruya-Feldstein J., Kelliher M. A., Speleman F., Porco J. A. Jr, Pelletier J., Rätsch G., Wendel H.-G., RNA G-quadruplexes cause eIF4A-dependent oncogene translation in cancer. Nature. 513, 65–70 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duncan R. F., Hershey J. W., Translational repression by chemical inducers of the stress response occurs by different pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 256, 651–661 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Azzam M. E., Algranati I. D., Mechanism of Puromycin Action: Fate of Ribosomes after Release of Nascent Protein Chains from Polysomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 70, 3866–3869 (1973). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiśniewski J. R., Hein M. Y., Cox J., Mann M., A “proteomic ruler” for protein copy number and concentration estimation without spike-in standards. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 13, 3497–3506 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Velculescu V. E., Madden S. L., Zhang L., Lash A. E., Yu J., Rago C., Lal A., Wang C. J., Beaudry G. A., Ciriello K. M., Cook B. P., Dufault M. R., Ferguson A. T., Gao Y., He T. C., Hermeking H., Hiraldo S. K., Hwang P. M., Lopez M. A., Luderer H. F., Mathews B., Petroziello J. M., Polyak K., Zawel L., Kinzler K. W., Analysis of human transcriptomes. Nat. Genet. 23, 387–388 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duncan R., Hershey J. W., Identification and quantitation of levels of protein synthesis initiation factors in crude HeLa cell lysates by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 7228–7235 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aoki K., Adachi S., Homoto M., Kusano H., Koike K., Natsume T., LARP1 specifically recognizes the 3’ terminus of poly(A) mRNA. FEBS Lett. 587, 2173–2178 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saba J. A., Liakath-Ali K., Green R., Watt F. M., Translational control of stem cell function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 671–690 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Delarue M., Brittingham G. P., Pfeffer S., Surovtsev I. V., Pinglay S., Kennedy K. J., Schaffer M., Gutierrez J. I., Sang D., Poterewicz G., Chung J. K., Plitzko J. M., Groves J. T., Jacobs-Wagner C., Engel B. D., Holt L. J., mTORC1 Controls Phase Separation and the Biophysical Properties of the Cytoplasm by Tuning Crowding. Cell. 174, 338–349.e20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fingar D. C., Salama S., Tsou C., Harlow E., Blenis J., Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4E. Genes Dev. 16, 1472–1487 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khajuria R. K., Munschauer M., Ulirsch J. C., Fiorini C., Ludwig L. S., McFarland S. K., Abdulhay N. J., Specht H., Keshishian H., Mani D. R., Jovanovic M., Ellis S. R., Fulco C. P., Engreitz J. M., Schütz S., Lian J., Gripp K. W., Weinberg O. K., Pinkus G. S., Gehrke L., Regev A., Lander E. S., Gazda H. T., Lee W. Y., Panse V. G., Carr S. A., Sankaran V. G., Ribosome Levels Selectively Regulate Translation and Lineage Commitment in Human Hematopoiesis. Cell. 173, 90–103.e19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mills E. W., Green R., Ingolia N. T., Slowed decay of mRNAs enhances platelet specific translation. Blood. 129 (2017), pp. e38–e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mura M., Hopkins T. G., Michael T., Abd-Latip N., Weir J., Aboagye E., Mauri F., Jameson C., Sturge J., Gabra H., Bushell M., Willis A. E., Curry E., Blagden S. P., LARP1 post-transcriptionally regulates mTOR and contributes to cancer progression. Oncogene. 34, 5025–5036 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu Z., Xu J., Lu H., Lin B., Cai S., Guo J., Zang F., Chen R., LARP1 is regulated by the XIST/miR-374a axis and functions as an oncogene in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 38, 3659–3667 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xie C., Huang L., Xie S., Xie D., Zhang G., Wang P., Peng L., Gao Z., LARP1 predict the prognosis for early-stage and AFP-normal hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 11, 272 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ye L., Lin S.-T., Mi Y.-S., Liu Y., Ma Y., Sun H.-M., Peng Z.-H., Fan J.-W., Overexpression of LARP1 predicts poor prognosis of colorectal cancer and is expected to be a potential therapeutic target. Tumour Biol. 37, 14585–14594 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hopkins T. G., Mura M., Al-Ashtal H. A., Lahr R. M., Abd-Latip N., Sweeney K., Lu H., Weir J., El-Bahrawy M., Steel J. H., Ghaem-Maghami S., Aboagye E. O., Berman A. J., Blagden S. P., The RNA-binding protein LARP1 is a post-transcriptional regulator of survival and tumorigenesis in ovarian cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 1227–1246 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ameismeier M., Cheng J., Berninghausen O., Beckmann R., Visualizing late states of human 40S ribosomal subunit maturation. Nature. 558, 249–253 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zemp I., Wild T., O’Donohue M.-F., Wandrey F., Widmann B., Gleizes P.-E., Kutay U., Distinct cytoplasmic maturation steps of 40S ribosomal subunit precursors require hRio2. J. Cell Biol. 185, 1167–1180 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zheng S. Q., Palovcak E., Armache J.-P., Verba K. A., Cheng Y., Agard D. A., MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang K., Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 193, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zivanov J., Nakane T., Forsberg B. O., Kimanius D., Hagen W. J., Lindahl E., Scheres S. H., New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife. 7 (2018), doi: 10.7554/eLife.42166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Punjani A., Rubinstein J. L., Fleet D. J., Brubaker M. A., cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods. 14, 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sanchez-Garcia R., Gomez-Blanco J., Cuervo A., Carazo J. M., Sorzano C. O. S., Vargas J., DeepEMhancer: a deep learning solution for cryo-EM volume post-processing. Commun Biol. 4, 874 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Emsley P., Cowtan K., Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L.-W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H., PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen V. B., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C., MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Meng E. C., Pettersen E. F., Couch G. S., Morris J. H., Ferrin T. E., UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information. Nanopore sequencing data is deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE246077). Code for analyzing sequencing data and qPCR data, and for generating plots has been posted on GitHub at repository 2023_Saba_Larp1 (https://github.com/jakesaba/2023_Saba_LARP1). Any additional data, code, or materials used in this article will be made available upon request. Cryo-EM structural data will be deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and Protein Data Bank (PDB) to be released upon article publication.