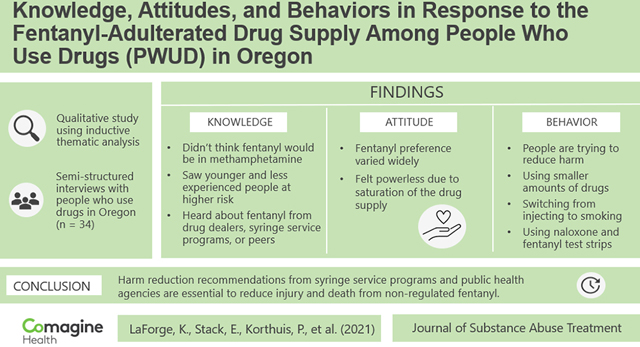

Abstract

Introduction:

Nonpharmaceutical fentanyl has reconfigured the U.S. illicit drug market, contributing to a drastic increase in overdose drug deaths. While illicit fentanyl has subsumed the drug supply in the Northeast and Midwest, it has more recently reached the West. For this study, we explored knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among people who use drugs in Oregon in the context of the emergence of fentanyl in the drug supply.

Methods:

We conducted in-depth interviews by phone with 34 people who use drugs in Oregon from May to June 2021. We used thematic analysis to analyze transcripts and construct themes.

Results:

People who use drugs knew about fentanyl, expressed doubt that fentanyl could be found in methamphetamine; believed those who were younger or less experienced were at higher risk for harm; and received information about fentanyl from drug dealers, syringe service programs, or peers (other people who use drugs). Preference for fentanyl’s presence in drugs like heroin or methamphetamine was mixed. Some felt that their preference was irrelevant since fentanyl was unavoidable. Participants reported engaging in harm reduction practices, including communicating about fentanyl with dealers and peers, testing for fentanyl, using smaller quantities of drugs, switching from injecting to smoking, and using naloxone.

Conclusion:

People who use drugs are responding to the rise of fentanyl on the West Coast and are concerned about the increasing uncertainty and hazards of the drug supply. They are willing and motivated to adopt harm reduction behaviors. Harm reduction promotion from syringe service programs and public health agencies is essential to reduce injury and death from nonpharmaceutical fentanyl.

Keywords: Fentanyl, Overdose, Opioids, Methamphetamine, Substance use, Harm reduction, Qualitative research

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The precipitous growth of nonpharmaceutical fentanyl in the drug supply in the United States has driven a rapid increase in overdose deaths (Mattson et al., 2021). Fentanyl is sold as pills or powders and adulterates other drugs, including heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine (Zibbell, 2019). In Vancouver, BC, a recent study identified fentanyl compounds in 84% of client-reported heroin (Karamouzian et al., 2018). Urine drug tests have shown a 154% increase from 2016 to 2019 in samples positive for fentanyl and methamphetamine (Twillman et al., 2020) and high co-occurrence of fentanyl alongside the sedative xylazine (Korn et al., 2021).

Fentanyl and fentanyl-adulterated drugs first saturated the drug supply in the American Northeast and Midwest (Ciccarone, 2019) and more recently have reached the West (Shover et al., 2020). In 2019, 26% of drug overdose deaths in the West involved nonpharmaceutical fentanyl, a 68% increase from 2018 and the largest increase in any US region (Mattson et al., 2021). Rates of overdose deaths involving methamphetamines and psychostimulants (i.e., cocaine) in Oregon have risen 447% over the past decade, from 42 deaths in 2010 to 230 deaths in 2018 (Oregon Health Authority Opioid Overdose and Misue Public Health Division, 2022). Increasing rates of fentanyl-related overdose have accompanied increasing co-use of opioids and stimulants (Baker et al., 2021; Daniulaityte et al., 2020; Strickland et al., 2019; Twillman et al., 2020).

Preference for fentanyl among people who use drugs (PWUD) varies. Some evidence suggests that preference for fentanyl may increase alongside the intensification of fentanyl saturation of the drug supply. Studies conducted within the past five years have found a preference for fentanyl among 27–44% of PWUD (Daniulaityte et al., 2019; Ickowicz et al., 2021; Morales et al., 2019; Peiper et al., 2019). Among PWUD, those who are younger, white, and use drugs daily are more likely to prefer fentanyl (Morales et al., 2019). A slightly increasing preference for fentanyl observed across studies may be attributed to increased use of fentanyl because of fentanyl’s saturation in the drug supply (Mars et al., 2019). Increasing exposure may increase tolerance levels among PWUD, which may shift preference toward more potent opioids (Armenian et al., 2018; Ickowicz et al., 2021; Peiper et al., 2019). Fentanyl is now detected in nonopioid drugs such as stimulants, but the field knows little about perceptions of fentanyl among people who use stimulants.

PWUD are open to adopting harm reduction strategies to reduce the risk of harm from fentanyl. PWUD practice sensory methods to detect fentanyl by sight, taste, or smell (Ciccarone et al., 2017; Daniulaityte et al., 2019; Duhart Clarke et al., 2022; Mars et al., 2018; McCrae et al., 2021; Rouhani et al., 2019; Zibbell et al., 2021). PWUD have also reported using tester shots (Mars et al., 2018), switching from injecting to smoking (Kral et al., 2021), using fentanyl test strips (McGowan et al., 2018; Zibbell et al., 2021), carrying naloxone (Goldman et al., 2019), and using drugs in smaller quantities (Somerville et al., 2017) to reduce fentanyl-related harm. Those who experienced an overdose (Goldman et al., 2019), injected drugs, or screened positive for fentanyl may be more likely to adopt harm reduction practices (Brar et al., 2020). PWUD have responded favorably to drug checking services (Sherman et al., 2019) and safe consumption spaces (Park et al., 2019), but drug checking presents barriers for PWUD, including giving up a drug sample, time, availability, and ambivalence to overdose risk (Bardwell et al., 2019).

While researchers in the American Northeast (Goldman et al., 2019; Gunn et al., 2021; Krieger et al., 2018; Latkin et al., 2019; Morales et al., 2019; Park et al., 2019; Rouhani et al., 2019; Weicker et al., 2020), American Midwest (Daniulaityte et al., 2019; Daniulaityte et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2018), and Canada (Bardwell et al., 2019; Brar et al., 2020; Karamouzian et al., 2018) have explored knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in response to fentanyl in the drug supply, we know less about perceptions of fentanyl and fentanyl harm reduction practices among people newly encountering fentanyl in the US Northwest, and among those with co-use of methamphetamine and opioids. The prevalence of drug use in Oregon has increased more than in other states; according to national survey data from 2019 to 2020, among those aged 12 or older, Oregon has the second-highest rate of overall past year illicit drug use (21.2%), ranks third in substance use disorder diagnoses (18.2%), and ranks first (1.9%) in the United States for reported past year methamphetamine use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021). In a recent study among adults who use drugs in rural Oregon, 96% of those who had used opioids in the past month reported also using methamphetamines (Baker et al., 2021). Given high rates of regional drug use, polysubstance use, and the dramatic increase in overdose deaths related to fentanyl on the West Coast, we believe regional specific–research is warranted given a rapidly evolving drug supply. This study aims to explore knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors associated with the rise of fentanyl in the drug supply among rural and urban people who use drugs in Oregon.

2. Methods

We conducted rapid assessment semi-structured qualitative interviews with PWUD from seven rural and urban Oregon counties (i.e., Clatsop, Deschutes, Josephine, Lane, Marion, Multnomah, and Umatilla). We selected counties with the following criteria: high overdose rates (relative to other Oregon counties); fentanyl seizures by the High-Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA) program; strong community connections to support recruitment; and geographic spread across the state. We built the interview guide by reviewing the literature, consulting with people with lived experience of substance use, and iteratively testing and refining guides with study team members (See Appendix Item 1). We conducted interviews by phone using interview guides that assessed fentanyl knowledge, fentanyl preferences, the experience of unintentional exposure to fentanyl, and fentanyl-involved overdoses. The OHSU Institutional Review Board approved the study and granted a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

2.1. Participants and procedures

We recruited participants (n = 34) from May 11 to June 25, 2021. We worked with syringe service program and community organization staff to recruit, including peer recovery support specialists who distributed flyers and assisted with participant-driven sampling. We aimed to conduct approximately 35 interviews, a sample size chosen based on team member experience, research aims, and research questions (Malterud et al., 2016). To be eligible, participants had to be age 18 or older and have endorsed the use of methamphetamine, cocaine, benzodiazepines, heroin, fentanyl, or other opioids in the past 30 days. Interviews lasted from 45 to 100 minutes. Local syringe service programs and peer recovery support programs provided access to phones for participants. We obtained verbal consent before data collection.

Four research staff conducted all interviews. Research staff had master’s or bachelors-level training in public health (JP, KL), psychology (JEL), sociology (KL), and anthropology (SS), and all had experience collecting qualitative data and interviewing PWUD. Interviewers were trained to follow written procedures if a participant expressed experiencing thoughts of suicide, including providing the Suicide Lifeline number, offering to connect the participant to an on-call clinician for crisis counseling, and offering to connect the participant to a peer recovery support specialist for support. Study leadership reviewed interview audio recordings to provide ongoing feedback and ensure interview quality and completeness. Participants received a $50 e-gift card for participation, sent via email or text. A professional transcriptionist transcribed audio-recorded interviews, and study team members uploaded transcripts into NVivo software (Version 12) for analysis.

2.2. Analysis

We used thematic analysis with a deductive coding structure to analyze the interviews (Boyatzis, 1998). We used the interview guide to create the initial codes and an iterative process to refine the codebook. To achieve acceptable interrater reliability, two team members (KL, SS) coded the same transcript and ran a coding comparison query. The first test yielded a low kappa coefficient, so coders reviewed discrepant codes and added clarity to codebook definitions. Coders then coded a second transcript and ran a coding comparison query, achieving a kappa coefficient of > .80, which was deemed sufficient. Coders coded the remaining transcripts independently, meeting regularly to assess coding consistency. We stopped collecting data after completing 34 interviews; we considered our sample size (n = 34) sufficient given our data’s strength, density, and information power (Malterud et al., 2016). The qualitative research team (KL, SS, ES, JP) constructed themes from coded data by focusing on data applicability to our research questions (To what extent are PWUD in Oregon aware of fentanyl risks or able to identify fentanyl; and what are their perceptions of fentanyl desirability and avoidance techniques?); usefulness in designing interventions; and if data seemed important, urgent, novel, or surprising. Qualitative analysts brought themes to investigator team discussions and refined them iteratively in large group meetings. This analysis focused on themes around knowledge of, attitudes and preferences toward, and behavior change related to fentanyl.

3. Results

Of the 34 participants, most identified as female (47%) or male (47%), age ≥ 30 years (91.2%), and non-Hispanic White (74%). Thirty-two (94%) participants reported using methamphetamine or other stimulants in the past month, 28 (82%) reported heroin use, 21 (62%) reported nonpharmaceutical fentanyl use, 16 (47%) reported illicit benzodiazepine use, 8 (24%) reported cocaine or crack use, and 14 (44%) reported use of opioid pills (not perceived to be fentanyl). Twenty-eight (82%) reported using heroin and methamphetamine in the past month. Thirty (88%) participants reported injection drug use in the past 30 days (Table 1). We grouped findings into three main themes: 1) fentanyl knowledge, 2) attitudes toward fentanyl, and 3) fentanyl-related behaviors.

Table 1:

Participant demographics (n = 34)

| Characteristic | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 16 (47%) |

| Male | 16 (47%) |

| Non-binary | 2 (6%) |

| Age | |

| < 30 | 3 (9%) |

| 30–39 | 15 (44%) |

| 40–49 | 11 (32%) |

| 50+ | 5 (15%) |

| Race | |

| White | 29 (85%) |

| Multiracial | 3 (9%) |

| African American or Black | 1 (3%) |

| Other | 1 (3%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 28 (82%) |

| Hispanic | 6 (18%) |

| Urbanicity** | |

| Urban county | 15 (44%)_ |

| Rural county | 19 (56%) |

| Past 30-day drug use | |

| Methamphetamine/stimulants | 31 (91%) |

| Heroin | 28 (82%) |

| Street fentanyl* | 21 (62%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 16 (47%) |

| Opiate painkillers | 15 (44%) |

| Cocaine or crack* | 8 (24%) |

| Polysubstance use | |

| Heroin/opiate painkillers/street fentanyl and methamphetamine/stimulants/cocaine | 28 (82%) |

| Injection drug use in past 30 days | |

| Yes | 30 (88%) |

| No | 4 (12%) |

Missing 1 response

Designated by Office of Management and Budget (OMB) county designation

3.1. Fentanyl knowledge

3.1.1. Participants were aware of fentanyl danger

Participants expressed knowledge that fentanyl was dangerous, common, and present in many different drugs. Participants had received information about fentanyl in the drug supply from dealers, syringe service programs, and community members. Most participants knew fentanyl is an opioid and understood it to be dangerous. Participants highlighted the increased risk of overdose from fentanyl. When asked what they know about fentanyl, one participant described:

“It’s extremely potent, and it’s killing a bunch of people right now. I think I’ve lost 30 friends because of fentanyl in the past, I don’t know, six months.” (Male, 41–50 years old, Urban)

3.1.2. Participants believed less experienced and young PWUD were at high risk

Some participants reasoned that their length of time using drugs protected them from an overdose; for example: “I’m not really worried about myself. As I said, I’ve been doing it [heroin] for 27 years. It doesn’t even really get me high anymore, so I don’t worry about overdosing or anything like that.” Another reported a lowered perception of risk among young people, explaining that

“It’s a lot of the younger people who are not even scared of it [fentanyl]. It’s like, “Well, let’s do it.” It’s crazy. Stupid… I feel bad for the young people doing that stuff to begin with…. Yeah. I’d say 18 to 25.” (Male, 51–60 years old, Urban)

3.1.3. Participants who used methamphetamine believed they were at less risk

Participants reported knowledge of fentanyl presence in a wide variety of drugs, including stimulants, heroin, and benzodiazepines. They underscored the presence of fentanyl in heroin, claiming, “It’s [heroin] pretty much made out of fentanyl these days.” Some participants who used methamphetamine did not expect fentanyl adulteration of methamphetamine. A participant who used methamphetamine shared, “I personally don’t have any concerns because, like I said, I personally don’t use heroin.” Other participants echoed this disbelief that fentanyl would be in methamphetamine:

I have not [heard of fentanyl in meth]. Is that a thing? They’re trying to get people strung-out on it, I guess. Well, I guess. I don’t know. I don’t see how it would smoke very well in meth, but I could be wrong. (Female, 31–40 years old, Urban)

I never thought that fentanyl would be in meth. If you think of it, it’s used in substances. One is a stimulant and one’s a depressant, so you wouldn’t think that someone would mix the two. With fentanyl being an opiate and addicting, of course, it always seems someone would want their part to sell more, so they would mix it. But you can mix it—I didn’t know you could, until my friend had her fentanyl test strips. She tested her meth and it was in there. I would have never thought that. (Female, 31–40 years old, Urban)

Well, we only do meth. We don’t seek out any other drugs. We don’t do pills. We avoid that altogether. (Female, 31–40 years old, Rural)

3.1.4. Participants are talking about fentanyl’s presence in drugs with drug dealers, syringe service programs, or peers

Participants reported receiving information about fentanyl when buying drugs from drug dealers. Some participants had negative impressions of talking to dealers about fentanyl in their drugs:

They say, “Oh no, it’s fine” and “That’s not in there.” I’m sure it is, but they’re not going to tell you that. Oh, they don’t care. You tell them that you don’t want it and they’ll just force it down your throat anyway. Yeah. I don’t talk very much to them about anything. They’re not very good people to be talking to anyway. (Female, 31–40 years old, Rural)

Others described conversations with dealers who exhibited care and provided useful information about fentanyl, “The last time, my guy told me that there was fentanyl in it [methamphetamine] and to be super careful, because he knows how I am with it. It was nice of him to warn me, for sure.” Participants also learned about fentanyl in the drug supply more generally from syringe service programs or through peers.

Some of it is just on the street through other peers, peer drug users, also at the exchange for syringes, the nursing staff there. There’s people there who educated us a little bit about overdoses in the area and things like that. (Female, 31–40 years old, Rural)

3.2. Attitudes toward fentanyl

3.2.1. Participants’ preferences related to fentanyl varied

Preference for fentanyl was mixed. Some participants reported preferring fentanyl, liking the intensity of the high; for example: “It [fentanyl] increases the rush. Yeah. It makes it more potent”. Participants also liked the cost-effectiveness of fentanyl’s higher potency, explaining “I like fentanyl because you just need a little tiny bit of it, and you can get really high from a little bit of it”.

In contrast, other participants disliked the increased risk of overdose from fentanyl, the strong physical effects, and the uncertainty about potency that comes with fentanyl.

“I just don’t like how dangerous it is, how quick it is before it just kills you, pretty much. I’ve lost a lot of friends to it. The mortality rate behind it is crazy.” (Female, 31–40, Urban)

“I don’t like drugs when they’re causing me to literally pass out while I’m in the middle of something important or something.” (Male, 21 to 30 years old, Urban)

“It’s so hard to dose. I don’t trust somebody to distribute it across the bag that I’m doing. I don’t trust their knowledge of chemistry or pharmacokinetics or anything with pharmacology to be able to accurately cut heroin or any drug for a lot of people to safely do it.” (Female, 41–50 years old, Rural)

3.2.2. Participants’ preferences related to fentanyl were overshadowed by its ubiquity in the drug supply

Participants often reported ambivalent and sometimes conflicting sentiments about their preferences, which may be rooted in a sense of powerlessness in the face of a nearly completely adulterated drug supply. Participants shared:

Because the way I look at it, there is no way of avoiding it. If it’s there, it’s there. If it’s in it, it’s in it. I really can’t avoid it. I certainly don’t know what to do to get it out of it. I’m not a cook. I don’t know. I’ve never tried to do it, and I don’t want to try to do that. (Male, 31–40 years old, Urban)

Many participants expressed that fentanyl was unavoidable in the drug supply. When asked what harm reduction practices can be used to avoid buying drugs with fentanyl in them one participant explained, “Really, I can’t do anything. I really don’t do much to avoid it [fentanyl]. I don’t want it. All you can do is hope for the best.” Other participants explained that their need to avoid withdrawal drove their willingness to buy and use fentanyl or fentanyl-adulterated drugs:

Because my dealers are more transparent, they usually tell me the shit in the fentanyl is cheaper. If I’m really broke, but I need to get well, I’ll just fucking take it. Or before I’ll seek it out, if I’m really, really broke, I’m like, hey, I can get half as much that I normally get, and it’ll still last me this long. (Uses she/her pronouns, 21–30 years old, Urban)

Among all the addict friends that I have, none of them hesitate to use it the same way, in the same amount that they would use heroin. Usually, when they get it, they’re so sick that they just need that relief. There’s no hesitation whatsoever. (Female, 41–50 years old, Rural)

3.3. Harm reduction behavior

Participants commonly reported the adoption or continued use of harm reduction methods to decrease risk or harm from fentanyl. Participants also used harm reduction methods when buying drugs and when using drugs.

3.3.1. Purchasing drugs

Participants employed various strategies to reduce harm from fentanyl when buying drugs. Participants reported buying only from trusted sources, which participants defined as dealers they knew or went to repeatedly, “I only buy it [heroin]from the same people: One. I always go to the same person. I just don’t buy from random people.” Participants also reported learning about drug quality from others and using that information when purchasing drugs, “Well, if I hear that a bag for sure has been cut with fentanyl, I’ll be less apt to buy it than bags that I know haven’t been.”

3.3.2. Using drugs

Participants described using harm reduction methods when using drugs that they suspected had fentanyl in them. Some participants described methods to detect fentanyl before using drugs.

Others thought the experience of using fentanyl was unique, and they could tell they had used fentanyl after the experience. Participants relied on feel, taste, smell, or appearance to determine fentanyl’s presence in heroin. When asked how they knew fentanyl is in heroin, participants shared:

“It’s hard to explain. Fentanyl has a different high to it. It’s more like sleepy and less euphoric. Heroin is like… I don’t even know. It’s like putting a warm blanket on a cold day.” (Male, 21–30 years old, Urban)

“It does actually give it a bit of a “mediciney” taste. Heroin is normally vinegary. When it’s got fentanyl in it, it has more of a mediciney taste.” (Female, 31–40 years old, Urban)

“Usually, if it’s the more darker or shinier—more shiny, I would say shinier—it usually has more fentanyl in it [heroin].” (Female, 31–40 years old, Urban)

I’d say I don’t know what jet fuel tastes like, but when there’s a lot of fentanyl in a batch, it tastes really like jet fuel. It’s almost like jet fuel or something. (Male, 51–60 years old, Urban)

Participants held different views on the effectiveness of using sensory methods to detect fentanyl in other drugs, some felt “pretty confident about it” while another expressed that “It [heroin] could look, taste, and smell amazing, and then you do it, it’s complete garbage. Or it could be the complete opposite 180 of that.”

Some participants reported using fentanyl test strips to determine if fentanyl was present in drugs, although opinions on fentanyl test strip usefulness were mixed. While some participants mentioned that using fentanyl test strips helped to increase their knowledge, others expressed frustration with difficulty in using fentanyl test strips and the limited use of fentanyl test strips, explaining that “Even if you test it, you don’t know how much fentanyl is in the batch [of heroin]. The test strip doesn’t tell you that. It doesn’t tell you that this is 30-percent fentanyl and then 70-percent heroin, or fucking whatever.” The frequency with which people would test their drugs using fentanyl test strips varied widely from “every once in a while” to “twice a week.” Others had never used, heard of, or had access to fentanyl test strips.

Participants also described using harm reduction techniques such as switching from injecting to smoking. When asked about ways to reduce potential harm from fentanyl-adulterated drugs, one participant said they “smoke it [drug unclear] rather than inject it, because you’ll go to sleep before you actually flop [pass out]. Whereas injecting it, you might wait—you might flop.” Many participants also stated that “You could always do more but you can never do less,” reporting that they do a small amount at first to determine the strength of the drug.

Finally, participants overwhelmingly reported use of naloxone, and awareness that higher doses of naloxone were often needed in overdoses involving fentanyl:

“But the nasal ones, every time I’ve heard of the nasal ones, people have to use three or four of those on them because it doesn’t get in their mucous membranes fast enough.” (Female, 31–40 years old, Urban)

One participant told a story of overdosing on heroin, which they suspected contained fentanyl:

“My girlfriend found me in the bathroom. I’d already been down on the ground for at least 15, 20 to 30 minutes, probably. I was gasping for air. This was in a public restroom, in a public bathroom at Rite Aid in [redacted]. They found me like that, and they hit me with Narcan before they called 911… It was a pharmacist at Rite Aid [who hit me with Narcan] … They hit me with one. It was the nasal spray kind of Narcan. When the ambulance got there, they hit me with the injection of it. They only hit twice—one in the nasal, and one injection in my leg.” (Male, 31–40 years old, Urban)

4. Discussion

In our interviews with people who use drugs in two urban and five rural counties across Oregon, we found that participants understood fentanyl to be widely present in the drug supply and a driver of increased risk of overdose. We also found that fentanyl preferences varied. PWUD are internally conflicted, struggling with ambivalence and powerlessness, desirability, and fear of harm or overdose. We found that participants used or adopted multiple harm reduction strategies to reduce the risk of harm from fentanyl.

Our data suggest that people who primarily used methamphetamine were less aware of potential fentanyl adulteration in their drugs. This perception is a concern given Oregon’s high rates of polysubstance use involving opioids and methamphetamine (Baker et al., 2021). In our sample, 94% of participants reported methamphetamine or other stimulant use, and 82% reported using methamphetamine and heroin, opioids, or fentanyl. Participants in this study did not expect methamphetamine to be adulterated with fentanyl and doubted they were being exposed to fentanyl when they were not seeking out opioids. People who exclusively use stimulants may be less likely than people who use multiple substances or heroin alone to adopt harm reduction practices in the wake of fentanyl (Brar et al., 2020). Moreover, some PWUD who use heroin and methamphetamine report using methamphetamine to reverse heroin-related overdose (Baker et al., 2021; Daniulaityte et al., 2022). Our findings underscore the need for tailored interventions to reduce harm among people who use multiple substances. Findings also add to the existing literature by suggesting an increased need for information sharing with people who use stimulants. Communication strategies will likely differ for those who use stimulants regularly, those who use stimulants concurrently with opioids, and those who use stimulants occasionally or infrequently.

The degree to which drugs other than heroin are adulterated with fentanyl remains largely unknown. The drug supply changes rapidly, and widespread drug testing in the United States remains rare, making reliable data challenging to procure. Autopsy reports reveal drugs present in the event of overdose death but do not reveal drug composition. Drug seizure data are also limited; drug seizure agencies typically only test drugs involved in criminal cases. A study in Vancouver, BC, found that among drugs believed to be crystal methamphetamine, 5.9% tested positive for fentanyl (Tupper et al., 2018). In a recent study in San Francisco, among women who used cocaine or methamphetamine (but not heroin or opioids), fentanyl was detected in 0.3% of urine samples (Meacham et al., 2020). These early findings suggest a low but clinically important prevalence of fentanyl adulteration in methamphetamine; however, given difficulties around large-scale assessment of overall fentanyl adulteration within methamphetamine in the drug supply, our knowledge remains limited. Without access to fentanyl test strips and, importantly, more advanced testing devices like spectrometers (Harding et al., 2022), PWUD will have limited knowledge about their drugs’ contents. More evidence and drug testing are urgently needed to understand the severity of fentanyl adulteration in drugs besides heroin.

Participants reported a variety of harm reduction techniques adopted in response to fentanyl in the drug supply, including sensory methods of fentanyl detection, switching from injecting to smoking, and naloxone use. Despite the adoption of state laws aiming to facilitate naloxone distribution and use (Davis & Carr, 2015; Freeman et al., 2018), barriers remain, including lack of naloxone in rural areas (Walters et al., 2021), pharmacies not stocking naloxone (Guadamuz et al., 2019), cost (Schneider, Dayton, et al., 2021), lack of knowledge of where to obtain naloxone (Schneider, Urquhart, et al., 2021), and stigma (Hassan et al., 2022; Ko et al., 2021; McKnight & Des Jarlais, 2018; Winstanley et al., 2016). Access to harm reduction services may be further complicated by rurality (Seaman et al., 2021), a marginalized status like being female (Harris et al., 2021), or a person of color (Mistler et al., 2021). A recent study found that only 61% and 30% of people who use opioids reported having naloxone in urban and rural counties, respectively (Lipira et al., 2021). Emerging findings suggest that access to harm reduction services worsened during COVID-19 (Bolinski et al., 2022). Due to the high potency and binding affinity of fentanyl, reversing an overdose from fentanyl may require multiple administrations of naloxone (Kerensky & Walley, 2017), increasing the need for naloxone. Widespread and amplified distribution of naloxone is necessary to combat overdose mortality from fentanyl.

Finally, participants reported switching from injecting to smoking as a harm reduction strategy. This finding is consistent with recent research detailing a shift from injecting heroin to smoking fentanyl among people who inject drugs in San Francisco (Kral et al., 2021). Smoking instead of injecting drugs is advocated by public health and harm reduction agencies to reduce blood-borne infections and other harms but does not eliminate the overdose risk from fentanyl; but recently has been complicated by backlash to funding for safer smoking supplies (Stolberg, 2022). Our findings suggest that people who use drugs are responding to fentanyl adulteration in drugs and are motivated to adopt behaviors to reduce risk.

Although adoption of harm reduction practices is beneficial, a lack of options and feelings of powerlessness still drive PWUD to take grave risks. Our results highlight that with fentanyl expansion in the drug supply (Ciccarone, 2021), many people who use drugs to ease withdrawal symptoms do not have a choice except to use the drugs available to them. An evaluation of drug-checking services found that when drugs were positive for fentanyl pre-consumption, only 11% of participants planned to dispose of the drug, and 36% planned to reduce their dose (Karamouzian et al., 2018). The ability to use drug checking information may also be complicated among the most marginalized PWUD, who may not be able to afford to replace adulterated drugs (Bonn et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2021). Other studies have reported fatalism among people who use drugs toward fentanyl adulteration and overdose (Bardwell et al., 2019; Harris et al., 2021), which might reflect a reaction to the loss of agency in a fentanyl-saturated drug market. Our findings add to the existing literature by highlighting fear and feelings of helplessness produced or made worse by the increasing presence of fentanyl and fentanyl analogs among urban and rural people who use drugs in Oregon. Policymakers should consider more aggressive measures to reduce the risk of death posed by the unsafe drug supply, including overdose prevention sites and safer supply initiatives.

These findings, alongside other emergent evidence in the Pacific Northwest (Baker et al., 2021; Banta-Green & Williams, 2021), unfortunately indicate a similar fentanyl trajectory to Northeastern states characterized by high rates of fentanyl-related overdose. State and county public health departments, and local harm reduction agencies in Oregon have adopted similar practices to Northeastern states, supporting naloxone and fentanyl test strip distribution, syringe service programs (Oregon Health Authority Substance Use: Public Health Division, 2022), and, more recently, campaigns targeting youth about pills containing fentanyl. In November 2020, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of illegal substances (like heroin and methamphetamine) via Measure 110. The impact of Measure 110, which also includes funding for substance use treatment, is pending evaluation and it remains to be seen how it will impact the Oregon drug environment.

Our study has three important limitations. First, we worked with harm reduction agencies and peer support programs to recruit participants for this study. This limitation biased our sample toward people who regularly access and use harm reduction services. Second, the restrictions of COVID-19 forced us to adapt our recruitment strategy away from using in-person field recruitment. Future research should seek to understand the experiences with fentanyl among people who are less socially or geographically connected to harm reduction agencies. Third, our sample was limited in its lack of racial diversity. Although white people are the racial majority within Oregon, white participants were overrepresented in our sample relative to the state. These results are limited in that they do not reflect the knowledge, attitudes, or behavior of people of color regarding fentanyl. This experience varies due to structural racism and racialized stigma.

5. Conclusion

Our study suggests that PWUD, especially those connected to harm reduction services, are informed about and responding to the rise of fentanyl in the drug supply in Oregon. As fentanyl prevalence increases in the Pacific Northwest, public health organizations, state and county officials, and advocates must work to shift perceptions among PWUD about the prevalence of fentanyl in methamphetamine and other illicit substances; develop communication campaigns to alert the public of the increasing risk of drug use; increase distribution of naloxone and safer use kits (including smoking supplies); implement overdose prevention sites and drug checking services; increase access to low-barrier treatment including medications for opioid use disorder; and disseminate information through syringe service programs, harm reduction agencies, and peer networks to reduce the risk of overdose death.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

People who use drugs expressed doubt that fentanyl could be in methamphetamine

People who are less experienced using drugs may be at higher risk for harm

People feel powerless due to fentanyl saturation of the drug supply

People are talking about fentanyl with dealers and peers

People are switching from injecting to smoking to reduce harm

Acknowledgments:

We would like to express our deep appreciation for participants in this study who generously offered their time, wisdom, and perspectives to this research. This work would not be possible without the support and participation of our community partners across the state of Oregon including Joanna Cooper, Jordan Shin, Rebecca Noad, Amanda McCluskey, Laurie Hubbard, Ashley Jones, Megan Torres, Bill Bernard, Roxanne Hoyt, Amy Ashton-Williams, Jessica Pankey, Sabrina Garcia, Dawn Merrigan, Dean Jones, Joad Clark, Vinny Cancelliere, Lynn Vigil, Piper Marks, Rhody Elzaghal, Paul Gonzales, Joshua Haynes, Larry Howell, Lisa Kennedy, Claire Sidlow, Anthony Wilson, and Dane Zahner.

Funding Source:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (UH3DA044831, UG1DA01581), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1 NU17CE925018-01-00), and the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (UL1TR002369).

Footnotes

CRediT author statement

Kate LaForge: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft Erin Stack: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision Sarah Shin: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing Justine Pope: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation Jessica E. Larsen: Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing Gillian Leichtling: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition Judith M. Leahy: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing Andrew Seaman: Formal analysis, Writing – Review & Editing Dan Hoover: Writing – Review & Editing Mikaela Byers: Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing Caiti Barrie: Writing – Review & Editing Laura Chisholm: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition P. Todd Korthuis: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition

Conflict of interest:

Andrew Seaman has received investigator-initiated research support from Gilead and Merck Pharmaceuticals.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Armenian P, Vo KT, Barr-Walker J, & Lynch KL (2018). Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: a comprehensive review. Neuropharmacology, 134, 121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R, Leichtling G, Hildebran C, Pinela C, Waddell E, Sidlow C, Leahy JM, & Korthuis PT (2021). “Like Yin and Yang”: Perceptions of Methamphetamine Benefits and Consequences Among People Who Use Opioids in Rural Communities. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 15(1), 34–39. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta-Green C, & Williams J. (2021). Dramatic increases in opioid overdose deaths due to fentanyl among young people in Washington State. Seattle, WA: Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute, University of Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell G, Boyd J, Tupper KW, & Kerr T. (2019). “We don’t got that kind of time, man. We’re trying to get high!”: Exploring potential use of drug checking technologies among structurally vulnerable people who use drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 71, 125–132. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolinski RS, Walters S, Salisbury-Afshar E, Ouellet LJ, Jenkins WD, Almirol E, Van Ham B, Fletcher S, Johnson C, Schneider JA, Ompad D, & Pho MT (2022). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Drug Use Behaviors, Fentanyl Exposure, and Harm Reduction Service Support among People Who Use Drugs in Rural Settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19(4). 10.3390/ijerph19042230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn M, Palayew A, Bartlett S, Brothers TD, Touesnard N, & Tyndall M. (2020). Addressing the syndemic of HIV, hepatitis C, overdose, and COVID-19 among people who use drugs: the potential roles for decriminalization and safe supply. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 81(5), 556–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brar R, Grant C, DeBeck K, Milloy MJ, Fairbairn N, Wood E, Kerr T, & Hayashi K. (2020). Changes in drug use behaviors coinciding with the emergence of illicit fentanyl among people who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 46(5), 625–631. 10.1080/00952990.2020.1771721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D. (2019). The triple wave epidemic: supply and demand drivers of the US opioid overdose crisis. The International Journal of Drug Policy, 71, 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D. (2021). The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(4), 344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarone D, Ondocsin J, & Mars SG (2017). Heroin uncertainties: Exploring users’ perceptions of fentanyl-adulterated and -substituted ‘heroin’. International Journal of Drug Policy, 46, 146–155. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Carlson RR, Juhascik MP, Strayer KE, & Sizemore IE (2019). Street fentanyl use: Experiences, preferences, and concordance between self-reports and urine toxicology. International Journal of Drug Policy, 71, 3–9. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Silverstein SM, Crawford TN, Martins SS, Zule W, Zaragoza AJ, & Carlson RG (2020). Methamphetamine use and its correlates among individuals with opioid use disorder in a Midwestern US city. Substance Use & Misuse, 55(11), 1781–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniulaityte R, Silverstein SM, Getz K, Juhascik M, McElhinny M, & Dudley S. (2022). Lay knowledge and practices of methamphetamine use to manage opioid-related overdose risks. International Journal of Drug Policy, 99, 103463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, & Carr D. (2015). Legal changes to increase access to naloxone for opioid overdose reversal in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 112–120. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhart Clarke SE, Kral AH, & Zibbell JE (2022). Consuming illicit opioids during a drug overdose epidemic: Illicit fentanyls, drug discernment, and the radical transformation of the illicit opioid market. International Journal of Drug Policy, 99, 103467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman PR, Hankosky ER, Lofwall MR, & Talbert JC (2018). The changing landscape of naloxone availability in the United States, 2011 – 2017. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 191, 361–364. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman JE, Krieger MS, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn M, Sherman SG, Green TC, Bernstein E, Hadland SE, & Marshall BDL (2019). Suspected involvement of fentanyl in prior overdoses and engagement in harm reduction practices among young adults who use drugs. Substance Abuse, 40(4), 519–526. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1616245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadamuz JS, Alexander GC, Chaudhri T, Trotzky-Sirr R, & Qato DM (2019). Availability and Cost of Naloxone Nasal Spray at Pharmacies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2017. JAMA Network Open, 2(6), e195388. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn CM, Maschke A, Harris M, Schoenberger SF, Sampath S, Walley AY, & Bagley SM (2021). Age-based preferences for risk communication in the fentanyl era: ‘A lot of people keep seeing other people die and that’s not enough for them’. Addiction, 116(6), 1495–1504. 10.1111/add.15305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding RW, Wagner KT, Fiuty P, Smith KP, Page K, & Wagner KD (2022). “It’s called overamping”: experiences of overdose among people who use methamphetamine. Harm reduction journal, 19(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MTH, Bagley SM, Maschke A, Schoenberger SF, Sampath S, Walley AY, & Gunn CM (2021). Competing risks of women and men who use fentanyl: “The number one thing I worry about would be my safety and number two would be overdose”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 125, 108313. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan R, Roland KB, Hernandez B, Goldman L, Evans KN, Gaul Z, Agnew-Brune C, Buchacz K, & Fukuda HD (2022). A qualitative study of service engagement and unmet needs among unstably housed people who inject drugs in Massachusetts. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 108722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ickowicz S, Kerr T, Grant C, Milloy M, Wood E, & Hayashi K. (2021). Increasing preference for fentanyl among a cohort of people who use opioids in Vancouver, Canada, 2017–2018. Substance Abuse, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Karamouzian M, Dohoo C, Forsting S, McNeil R, Kerr T, & Lysyshyn M. (2018). Evaluation of a fentanyl drug checking service for clients of a supervised injection facility, Vancouver, Canada. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(1), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerensky T, & Walley AY (2017). Opioid overdose prevention and naloxone rescue kits: what we know and what we don’t know. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 12(4). 10.1186/s13722-0160068-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J, Chan E, & Doroudgar S. (2021). Patient perspectives of barriers to naloxone obtainment and use in a primary care, underserved setting: A qualitative study. Substance Abuse, 42(4), 1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn WR, Stone MD, Haviland KL, Toohey JM, & Stickle DF (2021). High prevalence of xylazine among fentanyl screen-positive urines from hospitalized patients, Philadelphia, 2021. Clinica Chimica Acta, 521, 151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral AH, Lambdin BH, Browne EN, Wenger LD, Bluthenthal RN, Zibbell JE, & Davidson PJ (2021). Transition from injecting opioids to smoking fentanyl in San Francisco, California. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 227, 109003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger MS, Goedel WC, Buxton JA, Lysyshyn M, Bernstein E, Sherman SG, Rich JD, Hadland SE, Green TC, & Marshall BDL (2018). Use of rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 61, 52–58. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Dayton L, Davey-Rothwell MA, & Tobin KE (2019). Fentanyl and Drug Overdose: Perceptions of Fentanyl Risk, Overdose Risk Behaviors, and Opportunities for Intervention among People who use Opioids in Baltimore, USA. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(6), 998–1006. 10.1080/10826084.2018.1555597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipira L, Leichtling G, Cook RR, Leahy JM, Orellana ER, Korthuis PT, & Menza TW (2021). Predictors of having naloxone in urban and rural Oregon findings from NHBS and the OR-HOPE study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 227, 108912. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, & Guassora AD (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars SG, Ondocsin J, & Ciccarone D. (2018). Toots, tastes and tester shots: user accounts of drug sampling methods for gauging heroin potency. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(1), 26. 10.1186/s12954-018-0232-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars SG, Rosenblum D, & Ciccarone D. (2019). Illicit fentanyls in the opioid street market: desired or imposed? Addiction, 114(5), 774–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, Kariisa M, Patel P, & Davis NL (2021). Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(6), 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae K, Wood E, Lysyshyn M, Tobias S, Wilson D, Arredondo J, & Ti L. (2021). The utility of visual appearance in predicting the composition of street opioids. Substance Abuse, 42(4), 775–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan CR, Harris M, Platt L, Hope V, & Rhodes T. (2018). Fentanyl self-testing outside supervised injection settings to prevent opioid overdose: Do we know enough to promote it? International Journal of Drug Policy, 58, 31–36. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight C, & Des Jarlais DC (2018). Being “hooked up” during a sharp increase in the availability of illicitly manufactured fentanyl: Adaptations of drug using practices among people who use drugs (PWUD) in New York City. International Journal of Drug Policy, 60, 82–88. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacham MC, Lynch KL, Coffin PO, Wade A, Wheeler E, & Riley ED (2020). Addressing overdose risk among unstably housed women in San Francisco, California: an examination of potential fentanyl contamination of multiple substances. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JM, Stogner JM, Miller BL, & Blough S. (2018). Exploring synthetic heroin: Accounts of acetyl fentanyl use from a sample of dually diagnosed drug offenders. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(1), 121–127. 10.1111/dar.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistler CB, Chandra DK, Copenhaver MM, Wickersham JA, & Shrestha R. (2021). Engagement in Harm Reduction Strategies After Suspected Fentanyl Contamination Among Opioid-Dependent Individuals. Journal of Community Health, 46(2), 349–357. 10.1007/s10900-020-00928-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales KB, Park JN, Glick JL, Rouhani S, Green TC, & Sherman SG (2019). Preference for drugs containing fentanyl from a cross-sectional survey of people who use illicit opioids in three United States cities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 204, 107547. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Health Authority Opioid Overdose and Misue Public Health Division. (2022). Overdose Deaths - Vital Records https://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/PreventionWellness/SubstanceUse/Opioids/Pages/data.aspx

- Oregon Health Authority Substance Use: Public Health Division. (2022). Harm Reduction. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PREVENTIONWELLNESS/SUBSTANCEUSE/Pages/harm-reduction.aspx

- Park JN, Sherman SG, Rouhani S, Morales KB, McKenzie M, Allen ST, Marshall BDL, & Green TC (2019). Willingness to Use Safe Consumption Spaces among Opioid Users at High Risk of Fentanyl Overdose in Baltimore, Providence, and Boston. Journal of Urban Health, 96(3), 353–366. 10.1007/s11524-019-00365-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, & Zibbell JE (2019). Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. International Journal of Drug Policy, 63, 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MK, Roth AM, Tabb LP, Groves AK, & Lankenau SE (2021). “I probably got a minute”: Perceptions of fentanyl test strip use among people who use stimulants. The International Journal of Drug Policy, 92, 103147-103147. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani S, Park JN, Morales KB, Green TC, & Sherman SG (2019). Harm reduction measures employed by people using opioids with suspected fentanyl exposure in Boston, Baltimore, and Providence. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 39. 10.1186/s12954-019-0311-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KE, Dayton L, Winiker AK, Tobin KE, & Latkin CA (2021). The role of overdose reversal training in knowing where to get naloxone: Implications for improving naloxone access among people who use drugs. Substance Abuse, 42(4), 438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KE, Urquhart GJ, Rouhani S, Park JN, Morris M, Allen ST, & Sherman SG (2021). Practical implications of naloxone knowledge among suburban people who use opioids. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman A, Leichtling G, Stack E, Gray M, Pope J, Larsen JE, Leahy JM, Gelberg L, & Korthuis PT (2021). Harm Reduction and Adaptations Among PWUD in Rural Oregon During COVID-19. AIDS and Behavior, 25(5), 1331–1339. 10.1007/s10461-020-03141-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Morales KB, Park JN, McKenzie M, Marshall BDL, & Green TC (2019). Acceptability of implementing community-based drug checking services for people who use drugs in three United States cities: Baltimore, Boston and Providence. International Journal of Drug Policy, 68, 46–53. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shover CL, Falasinnu TO, Dwyer CL, Santos NB, Cunningham NJ, Freedman RB, Vest NA, & Humphreys K. (2020). Steep increases in fentanyl-related mortality west of the Mississippi River: recent evidence from county and state surveillance. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 216, 108314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville NJ, O’Donnell J, Gladden RM, Zibbell JE, Green TC, Younkin M, Ruiz S, BabakhanlouChase H, Chan M, Callis BP, Kuramoto-Crawford J, Nields HM, & Walley AY (2017). Characteristics of Fentanyl Overdose - Massachusetts, 2014–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(14), 382–386. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6614a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolberg S. (2022). Uproar Over ‘Crack Pipes’ Puts Biden Drug Strategy at Risk. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/21/us/politics/biden-harm-reduction-crack-pipes.html

- Strickland JC, Havens JR, & Stoops WW (2019). A nationally representative analysis of “twin epidemics”: Rising rates of methamphetamine use among persons who use opioids. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 204, 107592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuse Substance and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). 2019–2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Model-Based Prevalence Estimates. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf

- Tupper KW, McCrae K, Garber I, Lysyshyn M, & Wood E. (2018). Initial results of a drug checking pilot program to detect fentanyl adulteration in a Canadian setting. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 242–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twillman RK, Dawson E, LaRue L, Guevara MG, Whitley P, & Huskey A. (2020). Evaluation of trends of near-real-time urine drug test results for methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl. JAMA Network Open, 3(1), e1918514-e1918514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters SM, Felsher M, Frank D, Townsend T, Muncan B, Friedman SR, & Ompad D. (2021). Rural and Urban Differences in Overdose Response and Prevention Among Persons Who Inject Drugs. Research Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-262761/v1 [DOI]

- Weicker NP, Owczarzak J, Urquhart G, Park JN, Rouhani S, Ling R, Morris M, & Sherman SG (2020). Agency in the fentanyl era: Exploring the utility of fentanyl test strips in an opaque drug market. International Journal of Drug Policy, 84, 102900. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley EL, Clark A, Feinberg J, & Wilder CM (2016). Barriers to implementation of opioid overdose prevention programs in Ohio. Substance Abuse, 37(1), 42–46. 10.1080/08897077.2015.1132294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibbell JE (2019). Latest Evolution of the Opioid Crisis: Changing Patterns in Fentanyl Adulteration of Heroin, Cocaine, and Methamphetamine and Associated Overdose Risk. In. RTI International. https://www.rti.org/insights/latest-evolution-opioid-crisis-changing-patterns-fentanyl-adulteration-heroin-cocaine-and

- Zibbell JE, Peiper NC, Clarke SED, Salazar ZR, Vincent LB, Kral AH, & Feinberg J. (2021). Consumer discernment of fentanyl in illicit opioids confirmed by fentanyl test strips: Lessons from a syringe services program in North Carolina. International Journal of Drug Policy, 103128. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.