Abstract

Background

Alcohol drinking behaviors change temporally and can lead to changes in related cancer risks; previous studies have been unable to identify the association between the two using a single-measurement approach. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the association of drinking trajectories with the cancer risk in Korean men.

Methods

A trajectory analysis using group-based trajectory modeling was performed on 2,839,332 men using data on alcohol drinking levels collected thrice during the Korean National Health Insurance Service’s general health screening program conducted between 2002 and 2007. Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to evaluate the associations between drinking trajectories and cancer incidence, after adjustments for age, income, body mass index, smoking status, physical activity, family history of cancer, and comorbidities.

Results

During 10.5 years of follow-up, 189,617 cancer cases were recorded. Six trajectories were determined: non-drinking, light, moderate, decreasing-heavy, increasing-heavy, and steady-heavy. Light-to-heavy alcohol consumption increased the risk for all cancers combined in a dose-dependent manner (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02–1.05 for light drinking, aHR 1.06; 95% CI 1.05–1.08 for moderate drinking, aHR 1.19; 95% CI, 1.16–1.22 for decreasing-heavy drinking, aHR 1.23; 95% CI, 1.20–1.26 for increasing-heavy drinking, and aHR 1.33; 95% CI, 1.29–1.38 for steady-heavy drinking [P-trend <0.001]). Light-to-heavy alcohol consumption was linked to lip, oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, colorectal, laryngeal, stomach, and gallbladder and biliary tract cancer risks, while heavy alcohol consumption was associated with hepatic, pancreatic, and lung cancer risks. An inverse association was observed for thyroid cancer. The cancer risks were lower for decreasing-heavy drinkers, compared to steady-heavy drinkers.

Conclusion

No safe drinking limits were identified for cancer risks; reduction in heavy intake had protective effects.

Key words: alcohol, cancer, cohort, Korea, trajectory

INTRODUCTION

Alcoholic beverages are classified as Group 1 carcinogens, with sufficient evidence supporting their role in cavity, pharyngeal, laryngeal, esophageal, colorectal, hepatic, and female breast cancers.1 Positive associations have been suggested between alcoholic beverages and gastric, pancreatic, gallbladder, lung, and prostate cancers.2,3 Some national guidelines recommend moderate drinking due to the protective effects of light-to-moderate drinking on the risk of cardiovascular diseases. However, whether such safe drinking limits exist for the risk of cancer remains controversial.4,5 In previous studies, estimation of an association between alcohol consumption and cancer risk mostly relied on single measurements of alcohol intake.2,3 However, temporal changes in the drinking amount have been reported.6,7 One study revealed that the alcohol consumption-associated cancer risk differed at different times.8 Thus, temporally different drinking patterns may lead to changes in the related cancer risks. Associations between alcohol consumption and cancer risk were reversible following drinking cessation.9 However, this finding is derived from retrospective studies, some of which analyzed subsets of former drinkers, which are not representative of the general population.9 Further studies on alcohol consumption and its health effects must involve a broader population and perform repeated measurements to reveal alcohol drinking patterns with greater accuracy.3

Recent epidemiological studies have adopted trajectory analyses10,11 to identify behavioral patterns over time. Several studies have investigated alcohol consumption trajectories7,12,13 and their associations with health outcomes, including all-cause mortality,14 cardiovascular disease incidence15 and mortality,14 and cancer mortality.14 However, there is limited research on alcohol consumption trajectories and cancer development.6,16 A recent Australian cohort study examined lifetime drinking patterns and suggested critical timelines regarding alcohol-related cancer etiology and prevention.6 However, it examined a limited number of cancers and focused on alcohol-related cancers.6 Therefore, using a trajectory analysis to comprehensively investigate the cancer risk based on alcohol drinking patterns would be meaningful. This population-based cohort study aimed to evaluate the associations of alcohol consumption trajectories with the risk of 20 cancers in Korean men.

METHODS

Data source and study population

The National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) is a public database covering the entire Korean population (50 million).17,18 The database comprises annually collected data on socio-demographics, healthcare utilization, mortality, and health examinations performed periodically.17 Insured adults and their dependents are eligible for a biennial general health examination.18

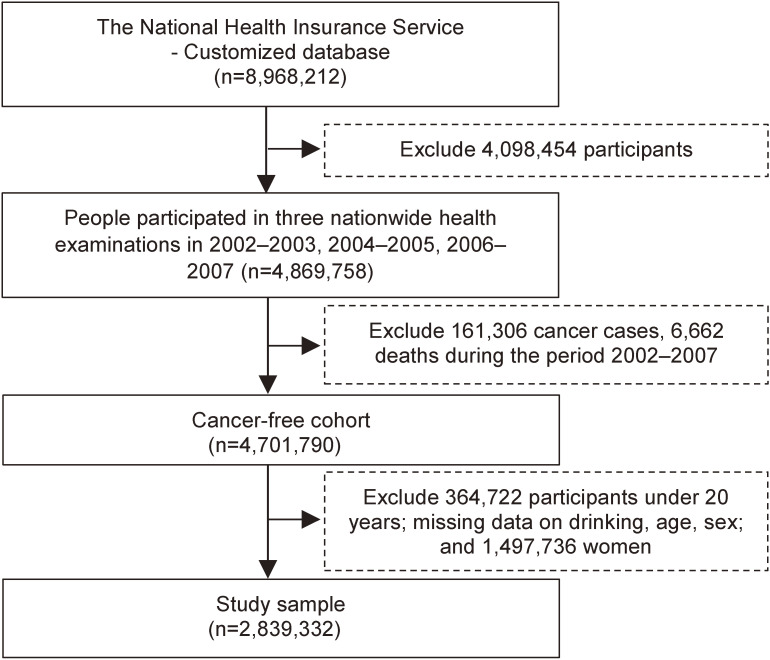

We referred to a customized NHIS database of 8,968,212 participants who underwent the 2002–2003 nationwide health examination and were followed up through to 2018. Among these, 4,869,758 individuals who underwent the 2002–2003, 2004–2005, and 2006–2007 nationwide health examinations were included. However, 161,306 individuals diagnosed with cancer before 2008; 6,662 individuals who died before 2008; 364,722 individuals under 20 years of age or with missing baseline data on age, sex, or alcohol consumption at the three aforementioned examinations; and 1,497,736 women were excluded. The remaining 2,839,332 men were finally included in this study. The study flow is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

This study was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC2018-0279), because it used anonymized secondary data. The requirement of informed consent was waived for the same reason.

Exposure and covariates

Alcohol consumption

Data on the drinking frequency and amount (per time) were collected using a self-administered questionnaire. Soju is the most commonly consumed alcoholic beverage in Korea; thus, the drinking amount per time was expressed in terms of soju bottles. Alcohol consumption (g/day) was estimated using the following formula:

where Q, V, C, d, and F represent the drinking amount per time (bottles), volume of the soju bottle (360 mL), percentage of ethanol by volume (20%), specific gravity of ethanol (0.8 g/mL), and monthly drinking frequency (reported for 28 days), respectively. Alcohol consumption was then categorized into six levels: 0, 1–9.9, 10–19.9, 20–29.9, 30–49.9, and ≥50 g/day. Data on the drinking levels collected during the three examinations were used for a trajectory analysis to determine the drinking patterns during 2002–2007. For people attending two examinations within a wave, data from the earlier measurement were used.

Covariates

Baseline data (2002–2003) on the age, income, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, physical activity, family history of cancer, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were used to adjust for confounding variables. Age and CCI19 were considered continuous, while categorical covariates included income (quintiles), BMI20 (<18.5, 18.5–22.9, 23.0–24.9, and ≥25.0 kg/m2), smoking status (never, former, and current smokers), physical activity (0, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, and 7 times/week), and family history of cancer (yes or no).

Case ascertainment

Cancer cases were defined by primary cancer diagnosis in hospitals, using the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes. Participants diagnosed before 2008 were excluded from the study population to form a cancer-free cohort. To obtain conservative results, cancer cases ascertained during 2008–2018 were confirmed by “V193,” a special code introduced by the NHIS from September 2005 to expand the insurance benefits for patients with cancer. The cancer date was defined as the first date of primary cancer diagnosis. The outcomes of interest included all cancers combined and alcohol-related cancers, which were categorized into the alcohol-related cancer group, including lip, oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, colorectal, hepatic, and laryngeal cancers.1 All cancers comprised these alcohol-related cancers and 15 other cancers (according to the GLOBOCAN cancer dictionary; hereafter referred to as “other cancer types”) for which evidence on a causal relationship with alcohol consumption is lacking.21

Statistical methods

Trajectory analysis

Trajectory analysis is used to determine distinct subgroups of similar behavioral patterns over time in a defined population.10 We adopted group-based trajectory modelling to investigate alcohol consumption, using the PROC TRAJ procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).11 Among the different trajectory analysis strategies, this semi-parametric strategy is commonly used in epidemiological research because it produces less complex and easy-to-interpret models that require less computing time.10

First, during group number selection, one-to-seven-group quadratic models were examined, given that up to six alcohol consumption trajectories were identified in previous studies.7,12,13 The optimal number of groups was identified based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC).11 However, the BIC values increased as more groups were added to the models (eTable 1). Then, a decision was taken based on group membership (≥1%), model parsimony, and distinct model features (eTable 2). A six-group model was selected because of the ability to separate abstainers and light drinkers and to subgroup different patterns of heavy alcohol consumption.

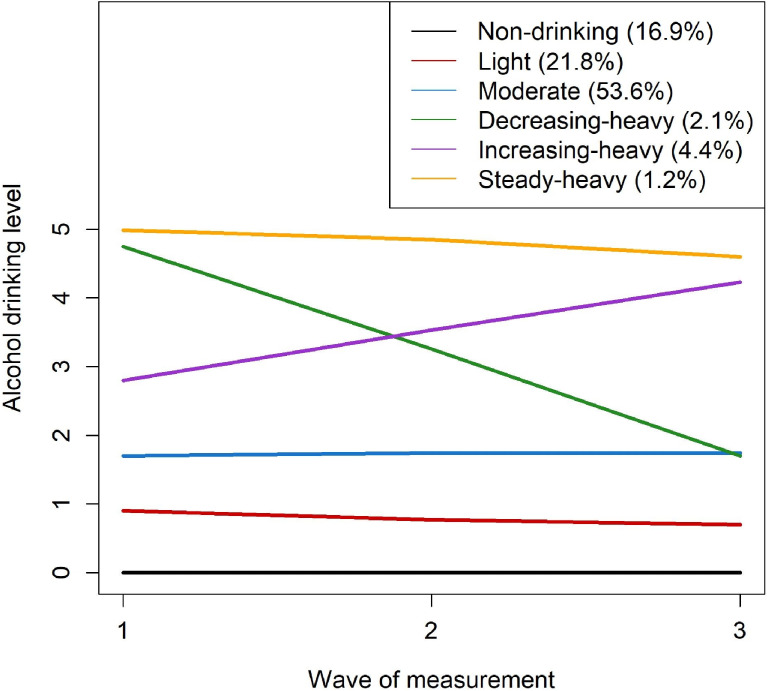

Next, during group order optimization, groups with a non-significant quadratic order (P-value <0.05) were reduced to those with a linear order.22 The never-drinker group was set at zero order. Models with extreme standard errors in the parameters were excluded. Based on the BIC values, we selected the six-group model with zero, linear, linear, linear, linear, and linear orders (Figure 2). Finally, the following six alcohol consumption trajectories were identified: 1) TR1, non-drinking (group membership after assignment: N = 480,832, 16.9%; drinking amount over three waves of measurement: mean 0; standard deviation [SD], 0 g/day); 2) TR2, light (N = 619,617, 21.8%; mean 3.2; SD, 2.1 g/day); 3) TR3, moderate (N = 1,521,465, 53.6%; mean 12.3; SD, 6.5 g/day); 4) TR4, decreasing-heavy (N = 60,511, 2.1%; mean 35.2; SD, 9.1 g/day); 5) TR5, increasing-heavy (N = 123,122, 4.4%; mean 38.7; SD, 9.3 g/day); and 6) TR6, steady-heavy (N = 33,785; 1.2%; mean 60.9; SD, 13.9 g/day).

Figure 2. Alcohol consumption trajectory model.

The final model was then evaluated using the average posterior probability (AvePP) of assignment and the odds of correct classification (OCC). An AvePP ≥0.7 and an OCC ≥5.0 are recommended to indicate good group assignment.11 Almost all groups in the selected models had a high AvePP (≥0.8) and OCC (≥12.3), except for the TR3 (moderate) group (OCC = 4.5; eTable 3). However, considering its OCC value was close to the recommended value, TR3 was also accepted for further analysis.

Cox proportional hazard regression

The Cox proportional hazard method was used to evaluate the associations between alcohol consumption and cancer incidence. The group assignment to alcohol consumption trajectories was treated as an independent variable (categorical). Furthermore, the baseline drinking level was utilized for comparison with the trajectory approach. Censored cases included participants who died during 2008–2018 or did not experience any events by the end of 2018. The time-to-event (years) was defined as the duration from January 1, 2008, to the cancer date, censored date, or December 31, 2018, whichever occurred first. It was assumed that a patient diagnosed with a specific cancer type was no longer at risk of other malignancies; thus, they were treated as censored on their cancer date in the analysis of other cancers. The non-drinking group was used as the reference.

Sensitivity analysis

Several sensitivity analyses were performed. To elicit the implications for behavioral change, the association of alcohol trajectories with the cancer risk was evaluated with TR6 (steady-heavy) as the reference. Because smoking status is highly correlated with drinking status, a subgroup analysis was performed for non-smokers. During the consideration of latent cases, we excluded cancer cases diagnosed in the year after 2007 from the study population. Furthermore, given that each trajectory of heavy drinkers, namely TR4 (decreasing-heavy), TR5 (increasing-heavy), and TR6 (steady-heavy), accounted for less than 5% of the study population, we combined these three groups into one (“heavy drinkers”) and examined the association of alcohol trajectories with the cancer risk.

RESULTS

General characteristics of the study population and cancer incidence

The general characteristics of the study population (by the alcohol drinking trajectories) are presented in Table 1 (descriptions by the baseline alcohol drinking levels in eTable 4). At the baseline, the mean age of the participants was 41.5 (SD, 11.6) years. Participants with excess weight (BMI ≥23 kg/m2) accounted for 61.7% of the total cohort. Only 18.7% participants performed physical exercises regularly (≥3 times/week). Approximately 50% of the participants were current smokers; approximately 71.5% reported being alcohol drinkers at the baseline and 14.0% consumed ≥20 g/day of alcohol. The trajectory approach assigned alcohol drinking levels consistent with the single-measurement classifications. Moderate and heavy drinkers were more likely to be older than light drinkers.

Table 1. General characteristics of the study population at study entry (2002–2003).

| Total (n = 2,839,332) |

(1) Non-drinking (n = 480,832) |

(2) Light (n = 619,617) |

(3) Moderate (n = 1,521,465) |

(4) Decreasing-heavy (n = 60,511) |

(5) Increasing-heavy (n = 123,122) |

(6) Steady-heavy (n = 33,785) |

|

| Age group, N (%) | |||||||

| 20–<30 years | 414,361 (14.6) | 45,013 (9.4) | 97,665 (15.8) | 250,627 (16.5) | 12,795 (10.4) | 6,482 (10.7) | 1,779 (5.3) |

| 30–<40 years | 956,856 (33.7) | 123,736 (25.7) | 209,055 (33.7) | 566,077 (37.2) | 36,342 (29.5) | 15,037 (24.9) | 6,609 (19.6) |

| 40–<50 years | 808,558 (28.5) | 134,635 (28.0) | 167,233 (27.0) | 437,288 (28.7) | 39,108 (31.8) | 18,727 (30.9) | 11,567 (34.2) |

| 50–<60 years | 403,361 (14.2) | 92,814 (19.3) | 87,257 (14.1) | 182,621 (12.0) | 21,058 (17.1) | 11,397 (18.8) | 8,214 (24.3) |

| 60–<70 years | 198,786 (7.0) | 61,729 (12.8) | 45,033 (7.3) | 69,227 (4.6) | 11,251 (9.1) | 6,936 (11.5) | 4,610 (13.6) |

| ≥70 years | 57,410 (2.0) | 22,905 (4.8) | 13,374 (2.2) | 15,625 (1.0) | 2,568 (2.1) | 1,932 (3.2) | 1,006 (3.0) |

|

| |||||||

| Income, N (%) | |||||||

| 1st quintile | 255,292 (9.0) | 54,850 (11.4) | 57,869 (9.3) | 120,829 (7.9) | 12,043 (9.8) | 6,267 (10.4) | 3,434 (10.2) |

| 2nd quintile | 390,612 (13.8) | 69,942 (14.5) | 85,708 (13.8) | 201,888 (13.3) | 18,337 (14.9) | 9,667 (16.0) | 5,070 (15.0) |

| 3rd quintile | 675,213 (23.8) | 109,303 (22.7) | 144,799 (23.4) | 367,757 (24.2) | 30,311 (24.6) | 14,921 (24.7) | 8,122 (24.0) |

| 4th quintile | 700,008 (24.7) | 111,855 (23.3) | 149,416 (24.1) | 385,606 (25.3) | 30,502 (24.8) | 14,283 (23.6) | 8,346 (24.7) |

| 5th quintile | 705,478 (24.8) | 120,629 (25.1) | 155,229 (25.1) | 380,311 (25.0) | 28,093 (22.8) | 13,198 (21.8) | 8,018 (23.7) |

| Missing | 112,729 (4.0) | 14,253 (3.0) | 26,596 (4.3) | 65,074 (4.3) | 3,836 (3.1) | 2,175 (3.6) | 795 (2.4) |

|

| |||||||

| Family history of cancer, N (%) | 367,548 (12.9) | 60,887 (12.7) | 73,402 (11.8) | 202,716 (13.3) | 8,338 (13.8) | 17,016 (13.8) | 5,189 (15.4) |

|

| |||||||

| Body mass index, N (%) | |||||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 60,652 (2.1) | 13,672 (2.8) | 14,515 (2.3) | 27,146 (1.8) | 1,947 (1.6) | 1,045 (1.7) | 605 (1.8) |

| 18.5–22.9 kg/m2 | 1,023,640 (36.1) | 181,328 (37.7) | 235,578 (38.0) | 536,885 (35.3) | 39,582 (32.1) | 19,235 (31.8) | 11,032 (32.7) |

| 22.9–24.9 kg/m2 | 780,828 (27.5) | 128,737 (26.8) | 169,391 (27.3) | 425,510 (28.0) | 32,711 (26.6) | 15,751 (26.0) | 8,728 (25.8) |

| ≥25 kg/m2 | 972,424 (34.2) | 156,248 (32.5) | 199,260 (32.2) | 530,386 (34.9) | 48,754 (39.6) | 24,402 (40.3) | 13,374 (39.6) |

| Missing | 1,788 (0.1) | 847 (0.2) | 873 (0.1) | 1,538 (0.1) | 128 (0.1) | 78 (0.1) | 46 (0.1) |

|

| |||||||

| Alcohol drinking, N (%) | |||||||

| 0 g/day | 810,493 (28.5) | 480,832 (100) | 247,558 (40.0) | 76,925 (5.1) | 5,178 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1–9.9 g/day | 891,728 (31.4) | 0 (0) | 291,129 (47.0) | 590,674 (38.8) | 9,925 (8.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 10–19.9 g/day | 738,441 (26.0) | 0 (0) | 70,383 (11.4) | 637,200 (41.9) | 30,858 (25.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 20–29.9 g/day | 227,533 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 8,608 (1.4) | 175,108 (11.5) | 43,817 (35.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 30–49.9 g/day | 63,085 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 1,939 (0.3) | 32,436 (2.1) | 21,274 (17.3) | 7,436 (12.3) | 0 (0) |

| ≥50 g/day | 108,052 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9,122 (0.6) | 12,070 (9.8) | 53,075 (87.7) | 33,785 (100) |

|

| |||||||

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||||

| Never smoker | 1,014,304 (35.7) | 269,547 (56.1) | 270,465 (43.7) | 427,420 (28.1) | 27,151 (22.1) | 12,790 (21.1) | 6,931 (20.5) |

| Former smoker | 445,732 (15.7) | 56,795 (11.8) | 94,035 (15.2) | 261,963 (17.2) | 18,989 (15.4) | 8,867 (14.7) | 5,083 (15.0) |

| Current smoker | 1,367,240 (48.2) | 152,571 (31.7) | 251,396 (40.6) | 826,422 (54.3) | 76,471 (62.1) | 38,684 (63.9) | 21,696 (64.2) |

| Missing | 12,056 (0.4) | 1,919 (0.4) | 3,721 (0.6) | 5,660 (0.4) | 511 (0.4) | 170 (0.3) | 75 (0.2) |

|

| |||||||

| Physical exercise, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 times/week | 1,238,772 (43.6) | 232,243 (48.3) | 280,387 (45.3) | 616,044 (40.5) | 31,266 (51.7) | 59,968 (48.7) | 18,864 (55.8) |

| 1–2 times/week | 997,719 (35.1) | 145,246 (30.2) | 210,266 (33.9) | 581,584 (38.2) | 15,828 (26.2) | 37,077 (30.1) | 7,718 (22.8) |

| 3–4 times/week | 326,480 (11.5) | 52,016 (10.8) | 69,234 (11.2) | 182,818 (12) | 6,027 (10) | 13,311 (10.8) | 3,074 (9.1) |

| 5–6 times/week | 71,344 (2.5) | 12,185 (2.5) | 14,823 (2.4) | 38,482 (2.5) | 1,592 (2.6) | 3,325 (2.7) | 937 (2.8) |

| Almost everyday | 132,090 (4.7) | 28,570 (5.9) | 27,951 (4.5) | 61,839 (4.1) | 4,540 (7.5) | 6,572 (5.3) | 2,618 (7.7) |

| Missing | 72,927 (2.6) | 10,572 (2.2) | 16,956 (2.7) | 40,698 (2.7) | 1,258 (2.1) | 2,869 (2.3) | 574 (1.7) |

|

| |||||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 2,805,892 (98.8) | 471,826 (98.1) | 611,025 (98.6) | 1,508,451 (99.1) | 59,639 (98.6) | 121,619 (98.8) | 33,332 (98.7) |

| 1 | 27,490 (1.0) | 7,055 (1.5) | 6,990 (1.1) | 11,120 (0.7) | 717 (1.2) | 1,247 (1.0) | 361 (1.1) |

| 2 | 4,358 (0.2) | 1,337 (0.3) | 1,177 (0.2) | 1,458 (0.1) | 118 (0.2) | 195 (0.2) | 73 (0.2) |

| ≥3 | 1,592 (0.1) | 614 (0.1) | 425 (0.1) | 436 (0.1) | 37 (0.1) | 61 (0) | 19 (0.1) |

After a mean follow-up of 10.5 years, 189,617 cancer cases were recorded (Table 2). The leading cancers included gastric (19.8%), colorectal (14.2%), lung (11.3%), prostate (10.4%), liver (8.8%), and thyroid (8.4%) cancers.

Table 2. Number of cancer incident cases during 2008–2018.

| Cancer types | ICD-10 | N (%) |

| Lip, oral cavity, and pharynx | C00–14 | 3,071 (1.6) |

| Esophagus | C15 | 2,652 (1.4) |

| Stomach | C16 | 37,614 (19.8) |

| Colon and rectum | C18–20 | 26,887 (14.2) |

| Liver | C22 | 16,624 (8.8) |

| Gallbladder and biliary tract | C23–24 | 4,266 (2.2) |

| Pancreas | C25 | 4,722 (2.5) |

| Larynx | C32 | 1,602 (0.8) |

| Lung | C33–34 | 21,464 (11.3) |

| Breast | C50 | 144 (0.1) |

| Prostate | C61 | 19,686 (10.4) |

| Testis | C62 | 251 (0.1) |

| Kidney | C64 | 5,270 (2.8) |

| Bladder | C67 | 6,332 (3.3) |

| Brain | C70–72 | 2,090 (1.1) |

| Thyroid gland | C73 | 15,901 (8.4) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | C81 | 158 (0.1) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | C82–86,96 | 3,592 (1.9) |

| Multiple myeloma, malignant plasma cell neoplasms | C90 | 1,245 (0.7) |

| Leukemia | C91–95 | 2,556 (1.3) |

| Others | Others | 13,490 (7.1) |

|

| ||

| Total | C00–97 | 189,617 |

ICD-10, the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision.

Cancer risks according to alcohol consumption

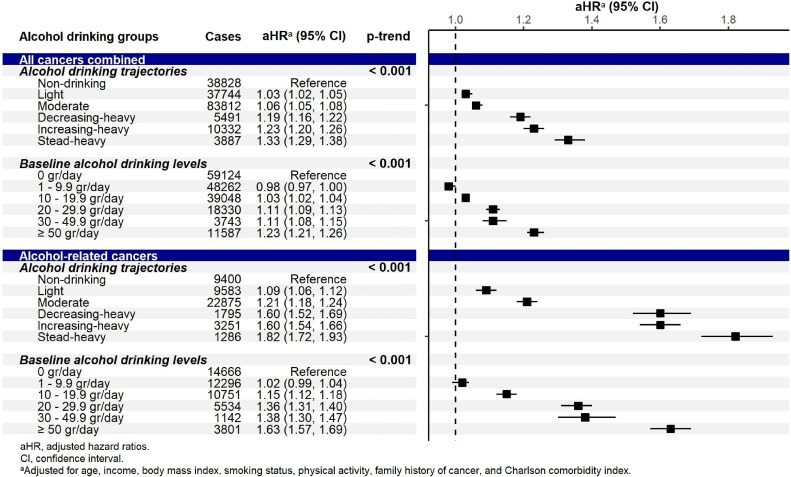

The adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations of alcohol consumption with cancer incidence are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5. For all cancers combined, alcohol intake significantly increased the cancer risk in a dose-dependent manner (ie, the risk increased with the drinking level; Figure 3). Specifically, in the trajectory approach, compared to the TR1 (non-drinking) trajectory, the aHRs were 1.03 (95% CI, 1.02–1.05) for the TR2 (light), 1.06 (95% CI, 1.05–1.08) for the TR3 (moderate), 1.19 (95% CI, 1.16–1.22) for the TR4 (decreasing-heavy), 1.23 (95% CI, 1.20–1.26) for the TR5 (increasing-heavy), and 1.33 (95% CI, 1.29–1.38) for the TR6 (steady-heavy) trajectories (P-trend <0.001). In the single-measurement approach, the cancer risk was observed to increase significantly from light alcohol intake (10 g/day) at slightly smaller magnitudes. For the alcohol-related cancer group (Figure 3), the significantly elevated risks were also observed in all trajectories with higher estimates and in a dose-dependent manner (P-trend <0.001).

Figure 3. Adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for the association between alcohol consumption and the risk for all cancers combined and for all alcohol-related cancers combined.

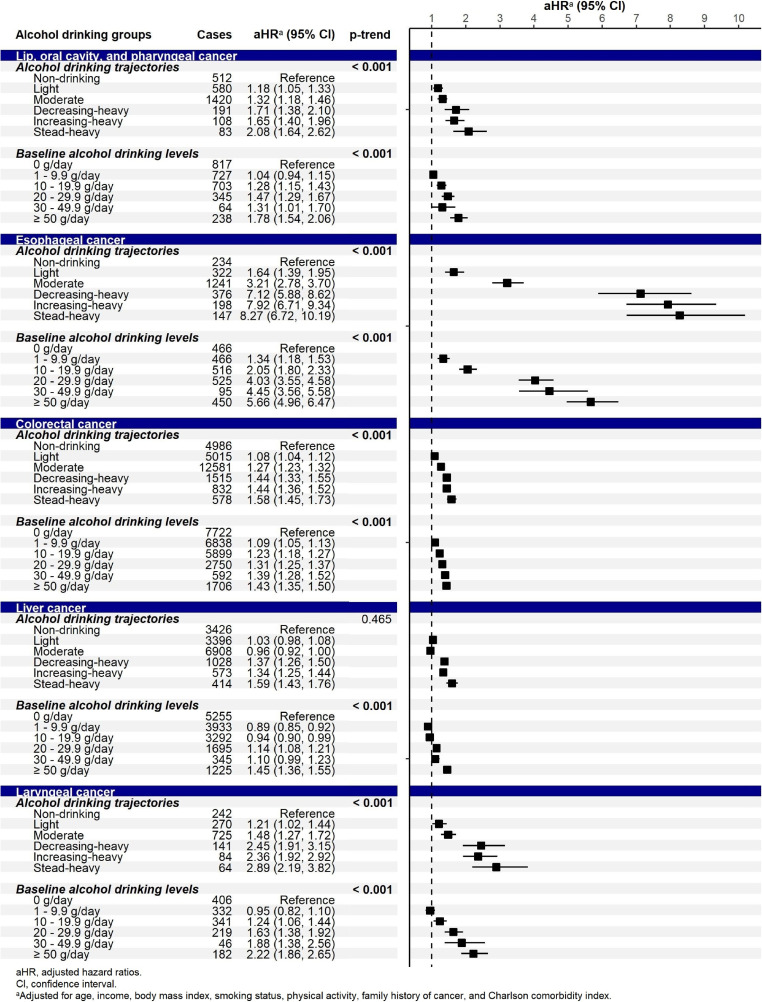

Figure 4. Adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for the association between alcohol consumption and the risk for alcohol-related cancers.

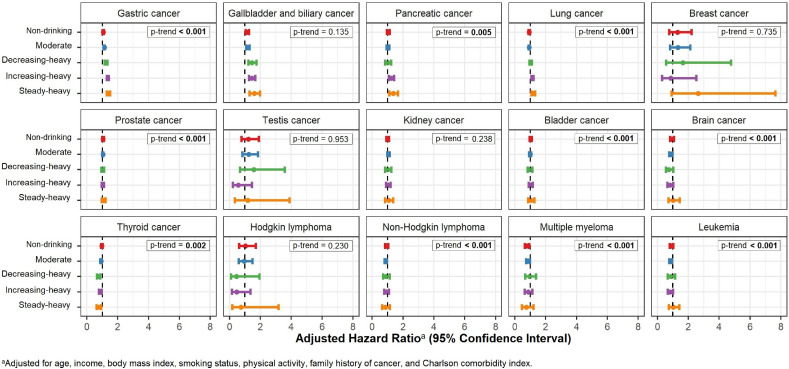

Figure 5. Adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) for the association between alcohol consumption and the risk for the group of other cancer types.

By specific cancers, significant associations were observed in alcohol-related cancers (Figure 4). The estimates of the association were the highest for esophageal cancer, followed by laryngeal cancer. The cancer risk significantly increased for all drinking trajectories for lip, oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, colorectal, and laryngeal cancers. Significant elevation was observed at heavy alcohol intake for liver cancer, specifically in the TR4 (decreasing-heavy), TR5 (increasing-heavy), and TR6 (steady-heavy) trajectories. We also found significant associations for some other cancers whose causal relationships with alcohol consumption have not been established yet (Figure 5, eTable 5). The risk increased by 7–40% for gastric cancer and 15–61% for gallbladder and biliary tract cancers following light intake; it also increased by 25–37% for pancreatic cancer and 15–19% for lung cancer in the TR5 (increasing-heavy) and TR6 (steady-heavy) trajectories. A significant inverse association was observed for thyroid cancer following moderate intake.

Sensitivity analysis revealed that compared to the TR6 (steady-heavy) trajectory, other trajectories were at a significantly lower risk for all cancers and all alcohol-related cancers combined (eTable 6). In particular, the risk for all cancers combined in the TR4 (decreasing-heavy) trajectory significantly decreased by 11–12%. Subgroup analysis of non-smokers supported our main findings (eTable 7). However, for lung cancer, a significant association between alcohol consumption and cancer risk was observed in the TR5 (increasing-heavy) trajectory only. The results after excluding incident cases during 1 year after 2007 were consistent with those of the main analysis (eTable 8). In the analysis of the combined “heavy drinker” group (eTable 9), the pooled risks were significantly increased for pancreatic and lung cancers, which were only found in the TR5 (increasing-heavy) and the TR6 (steady-heavy) trajectories in the main analysis.

DISCUSSION

We identified significant associations between alcohol consumption trajectories and the risks of all cancers combined, alcohol-related cancers combined (including lip, oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, colorectal, laryngeal, and hepatic cancers),1–3,23 and several cancers (including stomach, gallbladder, biliary tract, pancreatic, and lung cancers). The previously mentioned Australian study investigating alcohol consumption trajectories over the life-course also observed increased risks of alcohol-related cancers with similar estimates (45–94% increase).6 However, the limited number of cancer cases in that study enabled specific evaluations of the association between alcohol consumption and only colorectal cancer.6

We noted a significant cancer-risk elevation from light alcohol intake (≥10 g/day), which was previously reported for several cancers (including oropharyngeal, esophageal, and colorectal cancers).4,5,24,25 A meta-analysis on lifetime alcohol consumption also supports our findings for upper aero-digestive tract and colorectal cancers.23 However, some previous studies on colorectal cancer did not identify a significant relevance to the cancer risk at light alcohol consumption.26,27 Particularly, a meta-analysis of five case-control and 11 nested case-control studies reported a J-shaped association of alcohol consumption with the colorectal cancer risk, in which light-to-moderate drinking (≤28 g/day) was associated with a risk reduction (OR 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88–0.98), compared to non/occasional drinking (≤1 g/day).26 The significant associations of low alcohol consumption with laryngeal, gastric, and gallbladder and biliary tract cancers in our study have not been reported previously.4,5,28 A large sample size might enable us to detect the association at light alcohol intake. The temporal change of alcohol consumption can be captured with multiple measurements in trajectory analyses. For example, among the 891,728 participants consuming 1–9.9 g/day of alcohol at the baseline, 361,122 (40.5%) participants increased their consumption over a 6-year period (data not shown). They were then classified into three trajectories: TR2 (light; 32.7%), TR3 (moderate; 66.2%), and TR4 (increasing-heavy; 1.1%). Therefore, alcohol trajectories provide a useful approach for alcohol consumption classification.

The positive associations of heavy alcohol intake with hepatic and pancreatic cancers noted in this study have also been reported previously.2,29–31 We found a positive association of heavy drinking with lung cancer, which supports the finding from a meta-analysis that noted a 14% risk increase for >50 g/day of alcohol intake.2 Among non-smokers, this association reached statistical significance in only the TR5 (increasing-heavy) trajectory, given the small number of cases in the TR6 (steady-heavy) trajectory (N = 73, data not shown). A review on the association between alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in non-smokers concluded no clear effects of alcohol drinking on cancer risk; however, some of the studies included in the review showed a dose-response relation for total alcohol intake and for spirits.32 Further studies that consider the interaction between alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking and adjust for the smoking quantity are required to confirm the findings for this cancer type.

Our findings of the inverse association between alcohol consumption and thyroid cancer risk support the findings of previous studies.2 The mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear, although the following biological processes may be involved: reduction in the thyroid-stimulating hormone levels (risk factor for thyroid cancer) and its direct toxic effect on the thyroid cells (leading to thyroid volume reduction).33,34 Previous studies on the thyroid cancer “epidemic” in Korea suggested that the chance of thyroid cancer detection may be higher in never drinkers as they might seek healthcare services more actively.35,36 A positive dose-dependent association between alcohol use and thyroid enlargement was also reported previously.37 Thus, the protective effect of alcohol consumption on thyroid cancer should be interpreted cautiously.

Although distinct behavioral patterns identified in the trajectory analyses were specific to sample data,11 some of our trajectories were similar to those reported in other studies.7,12 The light, increasing-heavy, and decreasing-heavy trajectories in our study may correspond to the stable low risk, low-to-moderate risk, and moderate-to-low risk classes reported by Baek and Choi (2021),7 who analyzed Korean adults over a 11-year-period. Apart from the stable moderate risk class in their study, we further subgrouped moderate and heavy drinkers into two more classes (moderate and steady-heavy drinkers), enabling the detection of risk reduction in decreasing-heavy drinkers, compared with steady-heavy drinkers. In the Australian study, different patterns of heavy drinking were also observed during the life-course.6 Alcohol trajectories mapped over a short period, such as in our study, might not reflect the lifetime behavior for an individual. Nevertheless, the trajectory approach offers some key advantages over the single-measurement approach. First, trajectory modelling was performed in consistency with the baseline classification; it was more effective in demonstrating the association of alcohol consumption with the cancer risk at higher magnitudes of estimate. Trajectory analyses over a longer period may potentially reduce the sick-quitter bias caused by heterogeneity of the reference group (lifetime abstainers and former drinkers). Second, trajectory analysis differentiates subgroups of heavy drinkers. Lower risks in decreasing-heavy drinkers as compared to in steady-heavy drinkers implied positive health effects of drinking reduction. Conversely, the trade-off between distinctive model features and group membership should be considered. Provided that moderate and heavy drinkers accounted for only 6% of the population (≥30 g/day) at the baseline, a small group membership in subgroups of heavy drinking was expected; 1% of the study population was included in the model selection criteria instead of 5% applied in other studies.11 The sensitivity analysis was performed with the combined group of heavy drinkers, supporting our main findings. Lastly, the model selection criteria seemed subjective, particularly in case of the BICs increasing with the group number.11 We evaluated selected models using diagnostic criteria to ensure model quality for further analysis.

Our study has several strengths. Considering that the controversy on safe drinking limits with respect to cancer risks was derived from case-control studies, the population-based cohort design of our study is its strength. A large sample size and a long follow-up period helped examine various cancers. Furthermore, a trajectory analysis was used to capture the temporal alcohol drinking patterns. However, this study also has some limitations. Alcohol consumption was self-reported, so it could be under-reported.38 Besides, we were unable to distinguish between former and non-drinkers, because data on the drinking status were not available. Using insurance claims data, we defined cancer cases using ICD-10 codes as those diagnosed primarily and further confirmed by a special code for cancer patients. The reliability of primary cancer diagnosis in the NHIS data was confirmed in a recent study.39 Although we adjusted for some important covariates, residual confounders may exist, such as education, diet, and genetics. Future research should investigate drinking trajectories over longer time periods and adjust for confounders more comprehensively for specific cancers.

Alcohol-related health burden, including cancers, is a critical public health concern.40 In 2020, alcoholic beverages were globally responsible for 741,300 (4.1%) of new cases of cancers of all types, and the largest burden was present in men (76.7%).41 In Korea, men aged ≥15 years consume a yearly average of 16.7 L of pure alcohol (corresponding consumption in the western Pacific region: 7.3 L; 2016).40 While alcohol drinking is accepted in the Korean culture, no national action plan has been introduced in the country, making control of alcohol consumption tremendously challenging.40 This study provides high-quality evidence in support of alcohol carcinogenicity to humans and policy advocacy. In addition to alcohol-related cancers with established relations, we presented the associations of alcohol drinking with gastric, gallbladder and biliary tract, and pancreatic cancers. Drinking behaviors may change over time, leading to changes in related cancer risks. Therefore, for cancer prevention, initiation of alcohol consumption should be avoided and heavy drinkers should quit as soon as possible.

In conclusion, no safe drinking limits were identified for cancer risk. Light-to-heavy alcohol consumption significantly increased the risk for all cancers combined and for alcohol-related cancers combined in a dose-responsive pattern. Light alcohol consumption was significantly associated with the risk of lip, oral cavity, pharyngeal, esophageal, colorectal, laryngeal, stomach, and gallbladder and biliary tract cancers, and heavy consumption with the risk of hepatic, pancreatic, and lung cancers. Reduction in heavy alcohol consumption showed protective effects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by the National Cancer Center [grant number NCC-2010301]. The National Cancer Center had no role in the designing of the study; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the paper for publication. We also thank Ms Inhye Chang for providing administrative support for this work.

Data availability: The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available upon request from the National Health Insurance Sharing Service (https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Jin-Kyoung Oh and Min Kyung Lim. Methodology: Minji Han, Thi Tra Bui, Thi Phuong Thao Tran, and Ngoc Minh Luu. Formal analysis: Thi Tra Bui. Investigation: Jin-Kyoung Oh and Thi Tra Bui. Writing-original draft preparation: Thi Tra Bui. Writing-review and editing: Jin-Kyoung Oh and Min Kyung Lim. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

eTable 1. BIC estimation in trajectory analysis

eTable 2. Trajectory model selection

eTable 3. Trajectory model evaluation for the selected model (011111)

eTable 4. General characteristics of the study population by baseline alcohol drinking levels

eTable 5. Adjusted hazard ratiosa for the association between alcohol consumption and the risk for the group of other cancer types

eTable 6. Sensitivity analysis: Adjusted hazard ratiosa for the association between alcohol consumption trajectories and the cancer risk with the steady-heavy trajectory as the reference group

eTable 7. Adjusted hazard ratiosa for the association between alcohol consumption and the cancer risk in the subgroup of non-smokers (N = 1,014,304)

eTable 8. Adjusted hazard ratiosa for the association between alcohol consumption trajectories and the cancer risk in case of excluding all cancer cases diagnosed within 1 year after the exposure measurement period (2002–2007) (N = 2,821,315)

eTable 9. Adjusted hazard ratiosa (95% confidence interval) for the association between alcohol consumption trajectories and the cancer risk with the combination of the three alcohol trajectories into one group

REFERENCES

- 1.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans . Alcohol consumption and ethyl carbamate. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2010;96:3–1383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:580–593. 10.1038/bjc.2014.579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papadimitriou N, Markozannes G, Kanellopoulou A, et al. An umbrella review of the evidence associating diet and cancer risk at 11 anatomical sites. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4579. 10.1038/s41467-021-24861-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi YJ, Myung SK, Lee JH. Light alcohol drinking and risk of cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:474–487. 10.4143/crt.2017.094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Light alcohol drinking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:301–308. 10.1093/annonc/mds337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassett JK, MacInnis RJ, Yang Y, et al. Alcohol intake trajectories during the life course and risk of alcohol-related cancer: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:56–66. 10.1002/ijc.33973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baek S, Choi EH. A longitudinal analysis of alcohol use behavior among Korean adults and related factors: a latent class growth model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:8797. 10.3390/ijerph18168797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JE, Ryu Y, Cho SI. The effect of reference group classification and change in alcohol consumption on the association between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2017;41:379–387. 10.1111/acer.13299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarl J, Gerdtham UG. Time pattern of reduction in risk of oesophageal cancer following alcohol cessation—a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2012. Jul;107(7):1234–1243. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguena Nguefack HL, Pagé MG, Katz J, et al. Trajectory modelling techniques useful to epidemiological research: a comparative narrative review of approaches. Clin Epidemiol. 2020;12:1205–1222. 10.2147/CLEP.S265287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagin DS. Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. 214p. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobo JK, Greek AA, Klepinger DH, Herting JR. Predicting 10-year alcohol use trajectories among men age 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013. Feb;21:204–213. 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg N, Kiviruusu O, Karvonen S, et al. A 26-year follow-up study of heavy drinking trajectories from adolescence to mid-adulthood and adult disadvantage. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013. Jul–Aug;48:452–457. 10.1093/alcalc/agt026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jankhotkaew J, Bundhamcharoen K, Suphanchaimat R, et al. Associations between alcohol consumption trajectory and deaths due to cancer, cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: a 30-year follow-up cohort study in Thailand. BMJ Open. 2020. Dec 24;10:e038198. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Neill D, Britton A, Hannah MK, et al. Association of longitudinal alcohol consumption trajectories with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of six cohort studies using individual participant data. BMC Med. 2018. Aug 22;16:124. 10.1186/s12916-018-1123-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donat-Vargas C, Guerrero-Zotano Á, Casas A, et al. Trajectories of alcohol consumption during life and the risk of developing breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2021. Oct;125:1168–1176. 10.1038/s41416-021-01492-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheol Seong S, Kim YY, Khang YH, et al. Data Resource Profile: The National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:799–800. 10.1093/ije/dyw253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Lee JS, Park SH, Shin SA, Kim K. Cohort Profile: The National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:e15. 10.1093/ije/dyv319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Expert Consultation . Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global cancer observatory: cancer today – data and methods. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data-sources-methods; 2021 Accessed 16.07.2021.

- 22.Andruff H, Carraro N, Thompson A, Gaudreau P, Louvet B. Latent class growth modelling: a tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2009;5:11–24. 10.20982/tqmp.05.1.p011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayasekara H, MacInnis RJ, Room R, English DR. Long-term alcohol consumption and breast, upper aero-digestive tract and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51:315–330. 10.1093/alcalc/agv110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Duan H, Yang H, Lin J. A pooled analysis of alcohol intake and colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:6878–6889. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi YJ, Lee DH, Han KD, et al. The relationship between drinking alcohol and esophageal, gastric or colorectal cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of South Korea. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185778. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNabb S, Harrison TA, Albanes D, et al. Meta-analysis of 16 studies of the association of alcohol with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020. Feb 1;146:861–873. 10.1002/ijc.32377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu JZ, Wang YM, Zhou QY, Zhu KF, Yu CH, Li YM. Systematic review with meta-analysis: alcohol consumption and the risk of colorectal adenoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014. Aug;40(4):325–337. 10.1111/apt.12841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Islami F, Tramacere I, Rota M, et al. Alcohol drinking and laryngeal cancer: overall and dose-risk relation-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:802–810. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park H, Shin SK, Joo I, Song DS, Jang JW, Park JW. Systematic review with meta-analysis: low-level alcohol consumption and the risk of liver cancer. Gut Liver. 2020;14:792–807. 10.5009/gnl19163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu PY, Shu L, Shen SS, Chen XJ, Zhang XY. Dietary patterns and pancreatic cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9:38. 10.3390/nu9010038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang YT, Gou YW, Jin WW, Xiao M, Fang HY. Association between alcohol intake and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:212. 10.1186/s12885-016-2241-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García-Lavandeira JA, Ruano-Ravina A, Barros-Dios JM. Alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in never smokers. Gac Sanit. 2016;30:311–317. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegedüs L, Rasmussen N, Ravn V, Kastrup J, Krogsgaard K, Aldershvile J. Independent effects of liver disease and chronic alcoholism on thyroid function and size: the possibility of a toxic effect of alcohol on the thyroid gland. Metabolism. 1988;37:229–233. 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90100-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knudsen N, Bülow I, Laurberg P, Perrild H, Ovesen L, Jørgensen T. Alcohol consumption is associated with reduced prevalence of goitre and solitary thyroid nodules. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2001;55:41–46. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahn HS, Kim HJ, Welch HG. Korea’s thyroid-cancer “epidemic”-screening and overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1765–1767. 10.1056/NEJMp1409841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn HS, Kim HJ, Kim KH, et al. Thyroid cancer screening in South Korea increases detection of papillary cancers with no impact on other subtypes or thyroid cancer mortality. Thyroid. 2016;26:1535–1540. 10.1089/thy.2016.0075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valeix P, Faure P, Bertrais S, Vergnaud AC, Dauchet L, Hercberg S. Effects of light to moderate alcohol consumption on thyroid volume and thyroid function. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;68:988–995. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stockwell T, Zhao J, Macdonald S. Who under-reports their alcohol consumption in telephone surveys and by how much? An application of the ‘yesterday method’ in a national Canadian substance use survey. Addiction. 2014;109:1657–1666. 10.1111/add.12609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang MS, Park M, Back JH, et al. Validation of cancer diagnosis based on the National Health Insurance Service Database versus the National Cancer Registry Database in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2022. Apr;54:352–361. 10.4143/crt.2021.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.

- 41.Rumgay H, Shield K, Charvat H, et al. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021. Aug;22:1071–1080. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00279-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.