Abstract

Off-target aerobic activation of PR-104A by human aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) has confounded the development of this dual hypoxia/gene therapy prodrug. Previous attempts to design prodrugs resistant to AKR1C3 activation have resulted in candidates that require further optimization. Herein we report the evaluation of a lipophilic series of PR-104A analogues in which a piperazine moiety has been introduced to improve drug-like properties. Octanol–water partition coefficients (LogD7.4) spanned >2 orders of magnitude. 2D antiproliferative and 3D multicellular clonogenic assays using isogenic HCT116 and H1299 cells confirmed that all examples were resistant to AKR1C3 metabolism while producing an E. coli NfsA nitroreductase-mediated bystander effect. Prodrugs 16, 17, and 20 demonstrated efficacy in H1299 xenografts where only a minority of tumor cells express NfsA. These prodrugs and their bromo/mesylate counterparts (25–27) were also evaluated for hypoxia-selective cell killing in vitro. These results in conjunction with stability assays recommended prodrug 26 (CP-506) for Phase I/II clinical trial.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Prodrug, Cancer gene therapy, Nitroreductase, Nitrobenzamide mustard

PR-104A (1) is a 3,5-dinitrobenzamide nitrogen mustard prodrug administered to patients as the water-soluble phosphate ester pre-prodrug PR-104 (2)1 (Figure 1). Rapid conversion of PR-104 by serum esterases produces PR-104A, originally designed as a hypoxia-activated prodrug (HAP) that undergoes nitro reduction by cellular one-electron reductase’s under low-oxygen conditions. Reduction facilitates formation of the hydroxylamine (PR-104H) and amine (PR-104M) metabolites, which can lead to cytotoxicity through generation of interstrand DNA cross-links.1,2 In addition, concerted two-electron reduction by bacterial nitroreductase’s such asEscherichia coliNfsA (NfsA_Ec) can reduce PR-104A directly to various cytotoxic metabolites in an oxygen-independent manner.3 This is particularly useful in a gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (GDEPT) setting, whereby vector-mediated delivery of NfsA_Ec to tumor cells is able to produce localized activation of PR-104A, thus increasing its therapeutic index. PR-104 has been investigated clinically as a HAP4,5 and studied in preclinical models of GDEPT with some success.6,7 However, two-electron reduction by human aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) is known to contribute to off-target activation in oxygenated tissues, restricting the maximum plasma exposure achievable in human patients to between 10 and 29% of that achievable in murine models.8,9 In addition, rapid clearance of PR-104A in patients as a result of glucuronidation of the pendent primary alcohol side chain by UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 2B7 produces a suboptimal pharmacokinetic profile.10

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of reported (di)nitrobenzamide alcohol hypoxia/GDEPT prodrugs 1, 3, and 5 and their respective water-soluble phosphate ester pre-prodrugs 2, 4, and 6.

We recently reported a novel analogue of PR-104A, termed SN29176 (3) (Figure 1), that was designed to be resistant to off-target activation by human AKR1C3 while retaining hypoxia selectivity in vitro and in vivo when administered as the pre-prodrug SN35141 (4).9 In addition, we explored a series of analogues of SN29176 of varying lipophilicity and identified prodrug 5 (and its pre-prodrug 6) (Figure 1) as a preferred hypoxia/GDEPT prodrug with an optimized bystander effect (the ability of cytotoxic metabolites to diffuse into and sterilize metabolically naïve neighboring cells).11 While elimination of AKR1C3 activation is a significant advance, prodrugs 3 and 5 still contain an alcohol side chain and only achieve sufficient aqueous solubility for in vivo administration through use of a phosphate pre-prodrug strategy, rendering them susceptible to rapid clearance through the glucuronidation pathway. In addition, prodrug 5 exists as atropisomers at ambient temperature due to hindered rotation about the tertiary carboxamide moiety, an unfavorable feature that likely complicates further development. We hypothesized that replacement of the alcohol side chain of these derivatives with a symmetrical piperazine moiety would prevent the formation of atropisomers and also provide sufficient aqueous solubility for direct in vivo administration, thereby eliminating glucuronidation as a potential clearance mechanism. Herein we describe the design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a novel piperazine-bearing SN29176 analogue series, seeking to vary the lipophilicity of the compounds at both the alkylsulfone moiety (R1, Scheme 1) and the piperazine nitrogen (R2, Scheme 1), with the aim of identifying a hypoxia/GDEPT prodrug with an optimized bystander effect that remains resistant to human AKR1C3 metabolism.

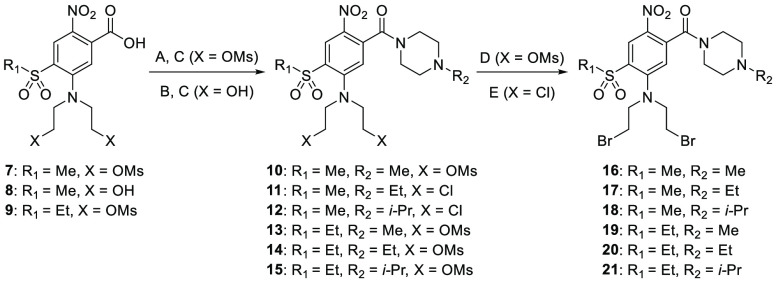

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 16–21.

Reagents and conditions: (A) (COCl)2, cat. DMF, MgO, DCM, MeCN, 0 °C to rt; (B) SOCl2, cat. DMF, reflux; (C) 1-alkylpiperazine, DCM, THF, 0 °C to rt; (D) LiBr, acetone, rt; (E) LiBr, 3-methyl-2-butanone, reflux.

We previously compared and contrasted two alternate routes in the preparation of prodrug 5 and analogues.11 Similar methods were employed in the synthesis of the current compounds. Briefly, diol carboxylic acid 8(9) was chlorinated with thionyl chloride, and the resultant acid chloride was coupled with 1-ethylpiperazine and 1-isopropylpiperazine to give the dichloro carboxamides 11 and 12, respectively (Scheme 1). Chlorine to bromine halogen exchange using lithium bromide in 3-methyl-2-butanone at reflux then gave the dibromo compounds 17 and 18, respectively. An improved route to the remaining compounds involved conversion of bismesylates 7 and 9(11) to their acid chlorides using oxalyl chloride in the presence of MgO to avoid undesired displacement of the mesylate groups with chloride ions. Coupling of the freshly prepared acid chlorides with various alkylpiperazines in situ then gave the bismesylate carboxamides (10, 13–15). Mesylate displacement using lithium bromide in acetone at room temperature then gave the desired dibromo derivatives (16, 19–21) (Scheme 1).

A low-cell-density antiproliferative assay was performed to determine the activity of compounds 16–21 in comparison to PR-104A (1) in both HCT116 and H1299 cell lines overexpressing the major nitroreductase fromE. coli, NfsA_Ec, and human AKR1C3. Both cell lines demonstrated WT:AKR1C3 antiproliferative ratios of <2 across all the novel compounds, compared to ratios of 15–60-fold for PR-104A (Table 1). This indicates that positioning of the piperazinecarboxamide side chain adjacent to the nitro substituent successfully prevents AKR1C3-mediated prodrug metabolism. In the HCT116 genetic background, NfsA_Ec expression led to antiproliferative activity, defined as the concentration required for 50% inhibition of control cell growth (IC50), ranging from 0.09 to 0.50 μM. There was a general trend that the methylsulfone (R1 = Me) derivatives (16–18) were more efficacious than their ethylsulfone (R1 = Et) comparators (19–21) in NfsA_Ec-expressing HCT116 cells. This was also observed in the H1299 cell line overexpressing NfsA_Ec, where IC50 values of the novel compounds ranged from 0.15 to 0.69 μM. Consistent with previous observations,11 it appeared that NfsA_Ec activity may be compromised as the analogue series became more lipophilic; therefore, we took the compounds forward into three-dimensional cell culture assays to investigate further.

Table 1. Cellular Antiproliferative Activity of Compounds 16–21 in HCT116 and H1299 Isogenic Cell Lines.

| HCT116

IC50 (μM)c |

HCT116

ratiosd |

H1299

IC50 (μM)c |

H1299 ratiosd |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R2 | LogD7.4a | WT | AKR1C3 | NfsA_Ec | WT:1C3 | WT:NfsA | WT | AKR1C3 | NfsA_Ec | WT:1C3 | WT:NfsA |

| 1 | NA | NA | 1.0 | 66 | 1.1 | 0.016 | 60 | 4125 | 114 | 7.4 | 0.048 | 15 | 2375 |

| 16 | Me | Me | 1.4 | 102 | 70 | 0.089 | 1.5 | 1146 | 98 | 102 | 0.154 | 1.0 | 636 |

| 17 | Me | Et | 1.7 | 77 | 49 | 0.104 | 1.6 | 740 | 71 | 71 | 0.175 | 1.0 | 406 |

| 18 | Me | i-Pr | 1.9b | 61 | 53 | 0.132 | 1.2 | 462 | 59 | 69 | 0.287 | 0.9 | 206 |

| 19 | Et | Me | 2.2b | 83 | 73 | 0.231 | 1.1 | 359 | 85 | 58 | 0.546 | 1.5 | 156 |

| 20 | Et | Et | 2.1 | 95 | 62 | 0.186 | 1.5 | 511 | 67 | 54 | 0.552 | 1.2 | 121 |

| 21 | Et | i-Pr | 2.5b | 65 | 70 | 0.496 | 0.9 | 131 | 49 | 67 | 0.685 | 0.7 | 73 |

Octanol–water partition coefficient, measured using a shake-flask method at pH 7.4.

Calculated using measured samples.

Relative sensitivity of HCT116 and H1299 monolayer cell lines determined as the concentration of prodrug required to inhibit cell growth by 50% compared to the untreated controls following 4 h drug exposure and 5 days’ regrowth. Mean IC50 values are shown. The coefficient of variation (CV) was <20% across all samples (standard error of the mean (SEM) values are included in Supplementary Table 1).

Ratio values were determined as the ratio of the average IC50 values between the nontransfected (wild-type, WT) and transfected (AKR1C3- or NfsA_Ec-expressing) cell lines.

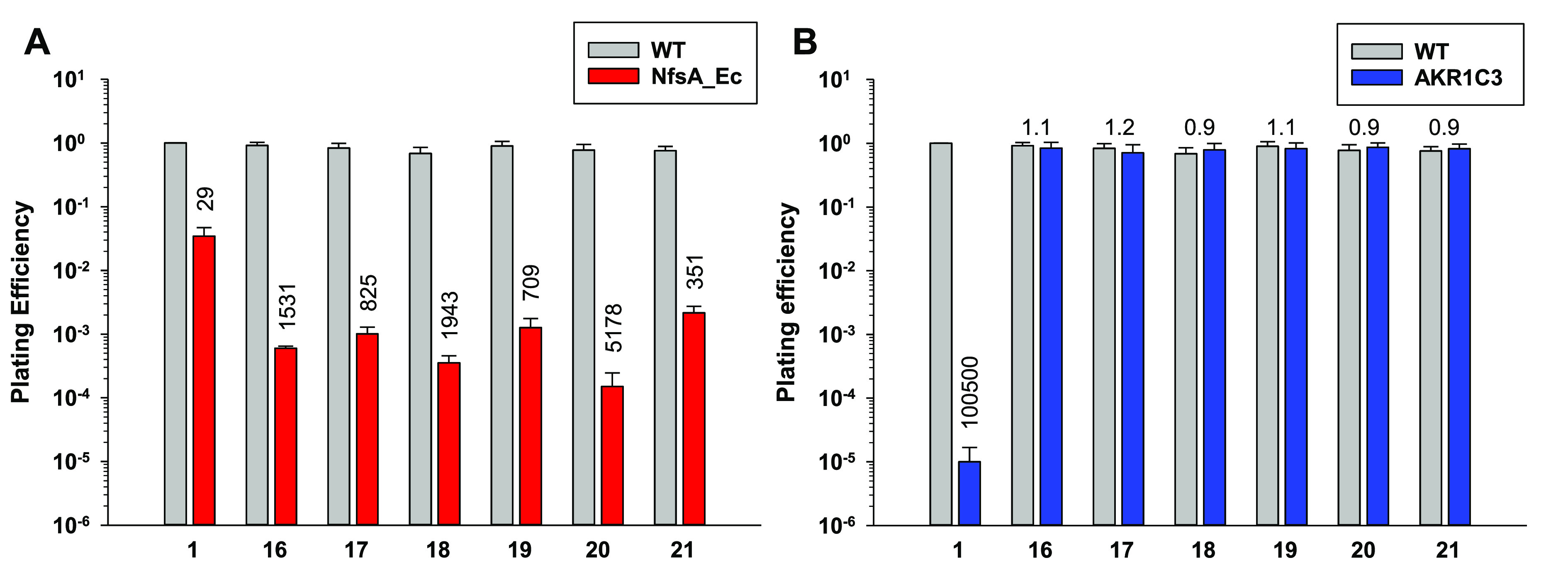

Three-dimensional mixed-cell multicellular layer (MCL) assays, with a minority (3%) of metabolically active NfsA_Ec-positive cells, allow for rigorous testing of prodrug bystander effects by measurement of clonogenic death of the major metabolically naïve cell population. Here, active cytotoxic prodrug metabolites are able to diffuse from “activator” cells into metabolically naïve “target” cells that are normally refractory to prodrug, exerting a “bystander effect”. Each of the novel analogues demonstrated an improvement in bystander activity (>700-fold change in plating efficiency compared to 100% wild-type control MCLs following exposure to 10 μM prodrug (cf. PR-104A (1), 29-fold change in plating efficiency; Figure 2A)). Notably, all of the novel compounds performed better than PR-104A in this assay despite having >5.5-fold higher HCT116 NfsA_Ec IC50 values.

Figure 2.

Clonogenic survival of isogenic HCT116 cells in three-dimensional cell culture multicellular layers (MCLs) exposed to 10 μM PR-104A (1) or prodrugs 16–21. Average plating efficiencies of (A) HCT116 WT MCLs and HCT116 WT MCLs including 3% HCT116 NfsA_Ec cells or (B) HCT116 WT MCLs and HCT116 AKR1C3 MCLs. Values are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments. Fold change in plating efficiency is indicated above the columns for each compound and was determined as the ratio of the plating efficiency values between the nontransfected (wild-type, WT) and transfected (NfsA_Ec- or AKR1C3-expressing) cell lines.

We also tested the novel analogue series for AKR1C3 activity in 3D using 100% AKR1C3-expressing MCLs, confirming that all compounds were not activated by AKR1C3 at a concentration of 10 μM (Figure 2B). We had previously observed during the discovery of prodrug 5 that AKR1C3 activation can be detected in this MCL assay as the LogD7.4 value of the alcohol-bearing analogue series approaches approximately 1.6.11 Encouragingly, these data indicate that the introduction of a piperazine moiety in the analogous position is not tolerated by the AKR1C3 enzyme irrespective of the lipophilicity of the compound tested.

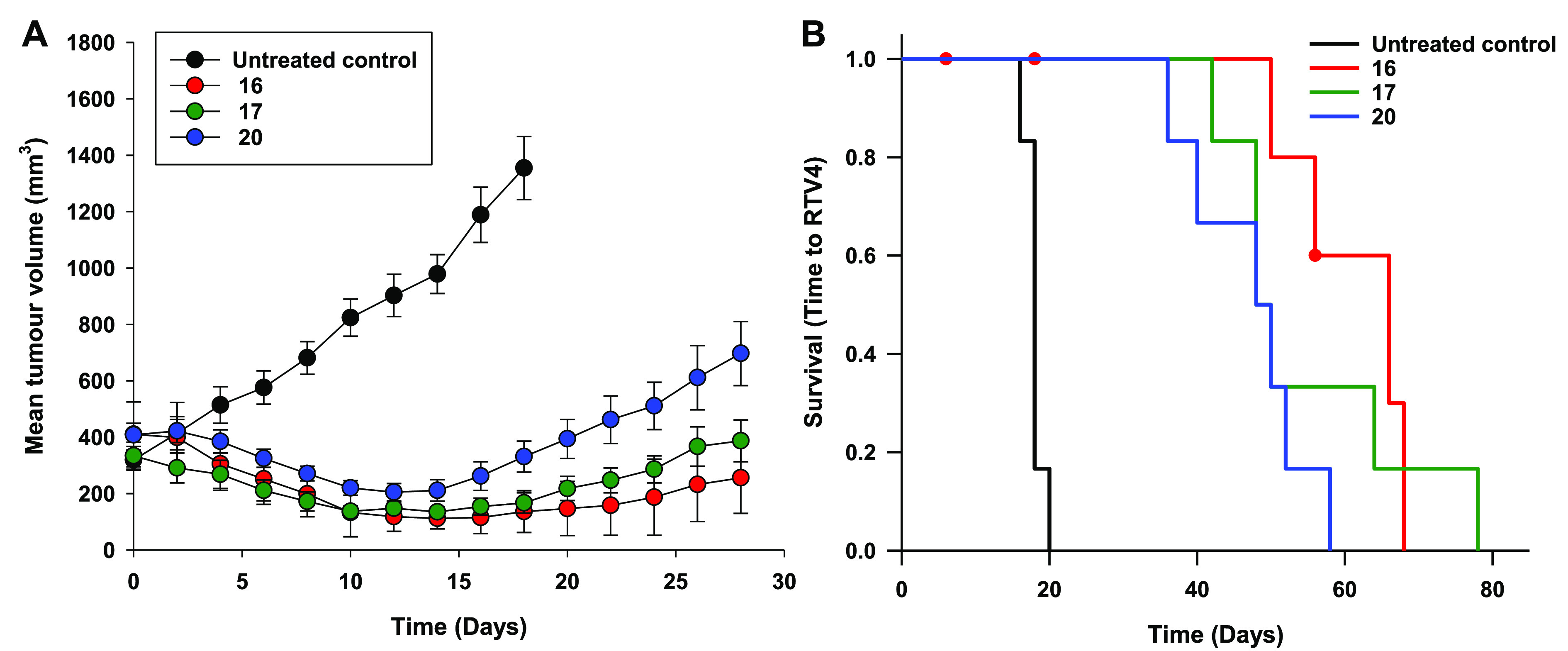

Compounds 16 and 17 were selected for in vivo analysis on the basis of possessing the largest NfsA_Ec IC50 ratios (Table 1), and compound 20 was selected as an ethylsulfone (R1 = Et) example with an acceptable NfsA_Ec IC50 ratio and with maximal log cell kill (LCK) in 3D (Figure 2A), thus ensuring a range in LogD7.4 values. The efficacy of the three lead compounds (16, 17, and 20) was evaluated at a nominal equimolar dose of 1000 μmol/kg (500 μmol/kg BID), which was found to be well-tolerated in non-tumor-bearing mice with minimal body weight loss (<10% for all compounds). The tumor growth delay assay employed utilizes H1299 tumor xenografts expressing a minority (33%) of NfsA_Ec-expressing H1299 “activator” cells (Figure 3A). This tumor model necessitates the presence of a robust prodrug bystander effect in order to achieve therapeutic efficacy and mimics the heterogeneous vector distribution commonly observed with gene therapy vectors. Untreated control tumors grew progressively, reaching 4 times the original starting volume (RTV4) in a median time of 18 days (Figure 3B). Tumors treated with compound 16 reached RTV4 in a median time of 66 days, a 267% improvement compared to controls (Figure 3B). However, the body weight loss nadir observed for this treatment group was significant in tumor-bearing animals, with an average of 12% body weight loss across the group (Supplementary Figure 1). Tumors treated with compounds 17 and 20 both reached RTV4 in a median time of 49 days (Figure 3B), a 167% improvement compared to controls (P = 0.32). Both compounds were well-tolerated, with ≤7% body weight loss observed at nadir (Day 6) and complete recovery by Day 16. However, there was a trend for 17 to exert greater control over tumor volume (60% regression in average tumor size in this group compared to 50% for compound 20, although this was not significant; P = 0.18), and thus, 17 was selected as the preferred candidate for GDEPT applications.

Figure 3.

Antitumor activity of compounds 16, 17, and 20 in NIH-III nude mice bearing NfsA_Ec-expressing H1299 xenografts. (A) Inhibition of growth of 33% NfsA_Ec/67% WT H1299 xenografts following intraperitoneal administration of test agents as a monotherapy (1000 μmol/kg [500 μmol/kg BID], Day 0, N ≥ 6 animals per group). (B) Kaplan–Meier analysis of the tumor growth delay study. The end point was defined as the time for tumors to reach 4 times the original starting volume (RTV4).

We next sought to investigate the potential of compounds 16, 17, and 20 as hypoxia-activated prodrugs. To provide a direct comparison with PR-104A (1) and a broader range of prodrug LogD7.4, we first prepared the direct bromo/mesylate asymmetric nitrogen mustard comparators of 16, 17, and 20 and advanced them to biological evaluation alongside their dibromo counterparts.

Briefly, the bromo/mesylate prodrugs 25–27 were prepared from the bismesylates 10, 24, and 14, respectively, through nucleophilic bromide displacement employing 1 equiv of lithium bromide followed by column chromatography (Scheme 2). Bismesylate 24 was itself prepared from fluorobenzene 22(12) via nucleophilic displacement with diethanolamine to give diol 23 and subsequent mesylation with methanesulfonic anhydride. While the present route to the asymmetric mustards is convenient for generating analogues on a small scale, we have recently reported the synthesis of prodrug 26 where we introduced the asymmetric mustard through reaction of fluorobenzene 22 with aziridine ethanol in the presence of lithium bromide,12 in an manner analogous to that described for the preparation of PR-104A.13

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compounds 25–27.

Reagents and conditions: (A) diethanolamine, DMSO, rt; (B) Ms2O, DCM, Et3N, 0 °C; (C) 1 equiv of LiBr, acetone, rt.

The ability of the dibromo (16, 17, and 20) and bromo/mesylate (25–27) mustard analogue series to selectively kill cells in the absence of oxygen was evaluated using a low-cell-density antiproliferative assay under aerobic and anoxic conditions (Table 2). In SiHa and HCT116 cells, all compounds displayed moderate hypoxic cytotoxicity ratios (HCRs; aerobic IC50 value divided by anoxic IC50 value) ranging from 11- to >20-fold and 5.3- to 21-fold, respectively. Overexpression of the human one-electron reductase cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) in HCT116 cells resulted in higher HCR values, ranging from 21- to 93-fold.

Table 2. Cellular Antiproliferative Activity of Compounds 16, 17, 20, and 25–27 in SiHa and HCT116 Isogenic Cell Lines under Aerobic and Anoxic Conditions.

| SiHa

IC50 (μM)b |

HCT116

IC50 (μM)b |

HCT116

POR IC50 (μM)d |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | R1 | R2 | X | LogD7.4a | aerobic | anoxic | HCRc | aerobic | anoxic | HCRc | aerobic | anoxic | HCRc |

| 1 | NA | NA | NA | 1.0 | 19 | 2.7 | 7.0 | 38 | 2.5 | 15 | 41 | 0.14 | 293 |

| 16 | Me | Me | Br | 1.4 | 241 | 16 | 15 | 160 | 24 | 6.6 | 82 | 0.88 | 93 |

| 25 | Me | Et | OMs | 0.3 | 561 | 47 | 12 | 368 | 23 | 16 | 139 | 1.6 | 87 |

| 17 | Me | Et | Br | 1.7 | 164 | 10 | 16 | 145 | 21 | 6.9 | 54 | 0.66 | 82 |

| 26 | Me | Et | OMs | 0.6 | 459 | 22 | 21 | 288 | 14 | 21 | 112 | 1.2 | 93 |

| 20 | Et | Et | Br | 2.1 | 253 | 23 | 11 | 142 | 27 | 5.3 | 60 | 2.8 | 21 |

| 27 | Et | Et | OMs | 1.0 | >300 | 15 | >20 | 254 | 18 | 14 | 122 | 2.8 | 44 |

Octanol–water partition coefficient, measured using a shake-flask method at pH 7.4.

Relative sensitivity of SiHa, HCT116 (wild type), and HCT116 POR monolayer cell lines under aerobic and anoxic conditions. IC50 values were determined as the concentration of prodrug required to inhibit cell growth by 50% compared to the untreated controls after 4 h drug exposure under aerobic or anoxic conditions followed by 5 days’ regrowth under aerobic conditions. Mean IC50 values are shown. The CV was <20% across all samples (SEM values are included in Supplementary Table 2).

HCR = hypoxic cytotoxicity ratio, determined as the ratio of IC50 values between aerobic and anoxic conditions.

HCT116 POR = HCT116 colon cancer cells transfected to overexpress human cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR).

We then determined the hypoxia-selective cytotoxicity of the analogue series in HCT116 three-dimensional MCLs, where the bystander effect of compounds may play a more significant role11 (Figure 4). Following exposure to 100 μM drug, cell death was minimal under hyperoxic conditions (95% O2, 5% CO2), with LCK values ranging from 0.016 to 0.38. In contrast, under anoxic conditions (95% N2, 5% CO2), a significant increase in cell death was observed across the analogue series, with LCK values ranging from 2.3 to 3.7. Unsurprisingly, LCK values were highest for the most lipophilic compounds (16, 17, and 20), consistent with our previous observations that increasing LogD7.4 correlated with increasing LCK at tissuelike cell densities.11 Overall, these data indicated that all compounds in the dibromo and bromo/mesylate mustard analogue series were hypoxia-selective. We therefore selected the preferred dibromo NfsA_Ec candidate 17 and its corresponding bromo/mesylate analogue 26 to advance to comparative mouse microsome stability testing.

Figure 4.

Clonogenic survival of HCT116 cells in three-dimensional cell culture multicellular layers (MCLs) exposed to 100 μM prodrugs 16, 17, 20, and 25–27 under aerobic and anoxic conditions. Log cell kill = Log CS(control) – Log CS(treated), where CS is the number of clonogenic survivors per MCL. Values are mean ± SEM for ≥3 independent experiments.

The relative extent of oxidative metabolism (metabolic or microsomal stability) of compounds 17 and 26 was determined using hepatic male mouse microsomal enzymes with NADPH as a cofactor (Figure 5). Both compounds underwent appreciable metabolic degradation over the period of the incubation (30 min), but compound 26 was more stable, with an estimated half-life of 41.2 min, compared to 6.05 min for compound 17. The enzymatic biotransformation of both compounds was negligible in the absence of NADPH, suggesting that CYP-mediated metabolism may be primarily responsible for the loss of the parent compounds. The poorer stability of compound 17 is consistent with the increased lipophilicity of the compound (relative to 26), suggesting greater CYP engagement and loss of parent compound through oxidative dealkylation of the bromoethyl mustard moiety, a known source of nitrogen mustard detoxification.14,15

Figure 5.

Stability of prodrugs 17 and 26 following incubation with mouse liver microsomes. Values are mean percentage of parent compound remaining ± SEM for triplicate incubations, with or without the addition of cofactor NADPH.

In summary, a lipophilic series of dibromo mustard GDEPT prodrugs (16–21) were synthesized incorporating a piperazine carboxamide moiety to improve the limitations of previously reported examples. Low- and high-cell-density assays in isogenic cell lines confirmed that the prodrugs were resistant to human AKR1C3 metabolism, an off-target activity that confounded the clinical development of PR-104. Conversely, low- and high-cell-density assays in cell lines overexpressing NfsA_Ec, the major nitroreductase from E. coli, confirmed that the prodrugs were substrates for this nitroreductase and were capable of exerting significant bystander cell killing, a key requirement for a GDEPT prodrug. This was further supported by in vivo evaluation of prodrugs 16, 17, and 20 in NIH-III nude mice bearing H1299 xenografts where a minority of cells (33%) express NfsA_Ec. In this GDEPT model, significant tumor growth delays and improvements in time to end point (RTV4) were observed. Next, the bromo/mesylate mustard counterparts of prodrugs 16, 17, and 20 were synthesized (25–27), and testing of the resulting series was extended to kill hypoxic cells in low- and high-cell-density in vitro assays. All examples demonstrated potential, with overexpression of the human cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase amplifying the effect in a mechanistically consistent oxygen-inhibited (one-electron) manner. However, mouse liver microsome stability testing of prodrugs 17 and 26 recommended the asymmetric bromo/mesylate prodrug 26 for further evaluation. Detailed mechanistic studies of prodrug 26 (also known as CP-506) have confirmed that it is resistant to AKR1C3 metabolism while demonstrating promising hypoxia-dependent antitumor activity in several human xenograft models.12 Targeted high-resolution/accurate-mass liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry adductomics studies have shown that prodrug 26 forms quantitatively more DNA adducts in cancer cells under hypoxia than normoxia.16 In addition, spatially resolved pharmacokinetic/pharmacokinetic modeling indicates that prodrug 26 possesses favorable pharmacological properties17 that support its selection (by Convert Pharmaceuticals) as a second-generation nitrobenzamide hypoxia-activated prodrug for Phase I/II clinical evaluation (NCT04954599).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Kendall Carlin, Ms. Huai-Ling Hsu, and Dr. Adrian Blaser for providing technical support for this project. This research was funded by The Health Research Council of New Zealand (14/289 and 17/255) and a Ph.D. scholarship from the University of Auckland awarded to A.M.M. The graphical abstract was created using BioRender.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AKR1C3

aldo-keto reductase 1C3

- CV

coefficient of variation

- GDEPT

gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy

- HAP

hypoxia-activated prodrug

- HCR

hypoxic cytotoxicity ratio

- LCK

log cell kill

- MCL

multicellular layer

- POR

human cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase

- RTV4

time for tumors to reach 4 times the original volume

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- WT

wild-type

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.3c00321.

Synthetic procedures for compounds 16–21 and 25–27, drug information and formulation, materials and methods for biological assays, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary Figure 1, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra for key compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ A.A. and A.M.M. contributed equally; A.V.P. and J.B.S. contributed equally. A.A., A.M.M., M.R.A., C.P.G., M.R.B., S.S., A.V.P., and J.B.S. conceived and designed the experiments; A.A., A.M.M., M.R.A., C.P.G., M.R.B., and S.S. performed the experiments; A.A., A.M.M., M.R.A., C.P.G., M.R.B., and S.S. analyzed the data; A.V.P. and J.B.S. acquired funding; A.A., A.M.M., A.V.P., and J.B.S. wrote the manuscript; M.R.A., C.P.G., M.R.B., and S.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript; all of the authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A.A., A.M.M., C.P.G., A.V.P., and J.B.S. are listed as inventors on the patents DK2888227T3, EP2888227B1, US10202408B2, CA2886574C, US9873710B2, AU2013/306514B2, and US9505791B2 issued and assigned to Health Innovation Ventures. As such, they potentially stand to benefit financially from the commercial development of this intellectual property. J.B.S. and A.V.P. report receipt of consultancy fees from Convert Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Material

References

- Patterson A. V.; Ferry D. M.; Edmunds S. J.; Gu Y.; Singleton R. S.; Patel K.; Pullen S. M.; Hicks K. O.; Syddall S. P.; Atwell G. J.; Yang S.; Denny W. A.; Wilson W. R. Mechanism of Action and Preclinical Antitumor Activity of the Novel Hypoxia-Activated DNA Cross-Linking Agent PR-104. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13 (13), 3922–3932. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.; Patterson A. V.; Atwell G. J.; Chernikova S. B.; Brown J. M.; Thompson L. H.; Wilson W. R. Roles of DNA Repair and Reductase Activity in the Cytotoxicity of the Hypoxia-Activated Dinitrobenzamide Mustard PR-104A. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8 (6), 1714–1723. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowday A. M.; Ashoorzadeh A.; Williams E. M.; Copp J. N.; Silva S.; Bull M. R.; Abbattista M. R.; Anderson R. F.; Flanagan J. U.; Guise C. P.; Ackerley D. F.; Smaill J. B.; Patterson A. V. Rational Design of an AKR1C3-Resistant Analog of PR-104 for Enzyme-Prodrug Therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 116, 176–187. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson M. B.; Rischin D.; Pegram M.; Gutheil J.; Patterson A. V.; Denny W. A.; Wilson W. R. A Phase I Trial of PR-104, a Nitrogen Mustard Prodrug Activated by Both Hypoxia and Aldo-Keto Reductase 1C3, in Patients with Solid Tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2010, 65 (4), 791–801. 10.1007/s00280-009-1188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeage M. J.; Gu Y.; Wilson W. R.; Hill A.; Amies K.; Melink T. J.; Jameson M. B. A Phase I Trial of PR-104, a Pre-Prodrug of the Bioreductive Prodrug PR-104A, given Weekly to Solid Tumour Patients. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 432. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.-C.; Ahn G.-O.; Kioi M.; Dorie M.-J.; Patterson A. V.; Brown J. M. Optimized Clostridium-Directed Enzyme Prodrug Therapy Improves the Antitumor Activity of the Novel DNA Cross-Linking Agent PR-104. Cancer Res. 2008, 68 (19), 7995–8003. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton D. C.; Mowday A. M.; Guise C. P.; Syddall S. P.; Bai S. Y.; Li D.; Ashoorzadeh A.; Smaill J. B.; Wilson W. R.; Patterson A. V. Bioreductive Prodrug PR-104 Improves the Tumour Distribution and Titre of the Nitroreductase-Armed Oncolytic Adenovirus ONYX-411NTR Leading to Therapeutic Benefit. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022, 29 (7), 1021–1032. 10.1038/s41417-021-00409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guise C. P.; Abbattista M. R.; Singleton R. S.; Holford S. D.; Connolly J.; Dachs G. U.; Fox S. B.; Pollock R.; Harvey J.; Guilford P.; Doñate F.; Wilson W. R.; Patterson A. V. The Bioreductive Prodrug PR-104A Is Activated under Aerobic Conditions by Human Aldo-Keto Reductase 1C3. Cancer Res. 2010, 70 (4), 1573–1584. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbattista M. R.; Ashoorzadeh A.; Guise C. P.; Mowday A. M.; Mittra R.; Silva S.; Hicks K. O.; Bull M. R.; Jackson-Patel V.; Lin X.; Prosser G. A.; Lambie N. K.; Dachs G. U.; Ackerley D. F.; Smaill J. B.; Patterson A. V. Restoring Tumour Selectivity of the Bioreductive Prodrug PR-104 by Developing an Analogue Resistant to Aerobic Metabolism by Human Aldo-Keto Reductase 1C3. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14 (12), 1231. 10.3390/ph14121231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y.; Tingle M. D.; Wilson W. R. Glucuronidation of Anticancer Prodrug PR-104A: Species Differences, Identification of Human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases, and Implications for Therapy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 337 (3), 692–702. 10.1124/jpet.111.180703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashoorzadeh A.; Mowday A. M.; Guise C. P.; Silva S.; Bull M. R.; Abbattista M. R.; Copp J. N.; Williams E. M.; Ackerley D. F.; Patterson A. V.; Smaill J. B. Interrogation of the Structure–Activity Relationship of a Lipophilic Nitroaromatic Prodrug Series Designed for Cancer Gene Therapy Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15 (2), 185. 10.3390/ph15020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wiel A. M. A.; Jackson-Patel V.; Niemans R.; Yaromina A.; Liu E.; Marcus D.; Mowday A. M.; Lieuwes N. G.; Biemans R.; Lin X.; Fu Z.; Kumara S.; Jochems A.; Ashoorzadeh A.; Anderson R. F.; Hicks K. O.; Bull M. R.; Abbattista M. R.; Guise C. P.; Deschoemaeker S.; Thiolloy S.; Heyerick A.; Solivio M. J.; Balbo S.; Smaill J. B.; Theys J.; Dubois L. J.; Patterson A. V.; Lambin P. Selectively Targeting Tumor Hypoxia With the Hypoxia-Activated Prodrug CP-506. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20 (12), 2372–2383. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.; Atwell G. J.; Denny W. A. Synthesis of Asymmetric Halomesylate Mustards with Aziridineethanol/Alkali Metal Halides: Application to an Improved Synthesis of the Hypoxia Prodrug PR-104. Tetrahedron 2007, 63 (25), 5470–5476. 10.1016/j.tet.2007.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goren M. P.; Wright R. K.; Pratt C. B.; Pell F. E. Dechloroethylation of Ifosfamide and Neurotoxicity. Lancet 1986, 328 (8517), 1219–1220. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills K. A.; Chess-Williams R.; McDermott C. Novel Insights into the Mechanism of Cyclophosphamide-Induced Bladder Toxicity: Chloroacetaldehyde’s Contribution to Urothelial Dysfunction in Vitro. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93 (11), 3291–3303. 10.1007/s00204-019-02589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solivio M. J.; Stornetta A.; Gilissen J.; Villalta P. W.; Deschoemaeker S.; Heyerick A.; Dubois L.; Balbo S. In Vivo Identification of Adducts from the New Hypoxia-Activated Prodrug CP-506 Using DNA Adductomics. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35 (2), 275–282. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.1c00329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Patel V.; Liu E.; Bull M. R.; Ashoorzadeh A.; Bogle G.; Wolfram A.; Hicks K. O.; Smaill J. B.; Patterson A. V. Tissue Pharmacokinetic Properties and Bystander Potential of Hypoxia-Activated Prodrug CP-506 by Agent-Based Modelling. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 803602 10.3389/fphar.2022.803602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.