Abstract

Water is a primary source of electrons and protons for photosynthetic organisms. For the production of hydrogen through the process of mimicking natural photosynthesis, photosystem II (PSII)-based hybrid photosynthetic systems have been created, both with and without an external voltage source. In the past 30 years, various PSII immobilization techniques have been proposed, and redox polymers have been created for charge transfer from PSII. This review considers the main components of photosynthetic systems, methods for evaluating efficiency, implemented systems and the ways to improve them. Recently, low-overpotential catalysts have emerged that do not contain precious metals, which could ultimately replace Pt and Ir catalysts and make water electrolysis cheaper. However, PSII competes with semiconductor analogues that are less efficient but more stable. Methods originally created for sensors also allow for the use of PSII as a component of a photoanode. To date, charge transfer from PSII remains a bottleneck for such systems. Novel data about action mechanism of artificial electron acceptors in PSII could develop redox polymers to level out mass transport limitations. Hydrogen-producing systems based on PSII have allowed to work out processes in artificial photosynthesis, investigate its features and limitations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12551-023-01139-5.

Keywords: Semi-artificial photosynthesis, Photosystem II immobilization, Hydrogenase immobilization, Redox polymers, Hydrogen evolution reaction, Water-splitting

Introduction

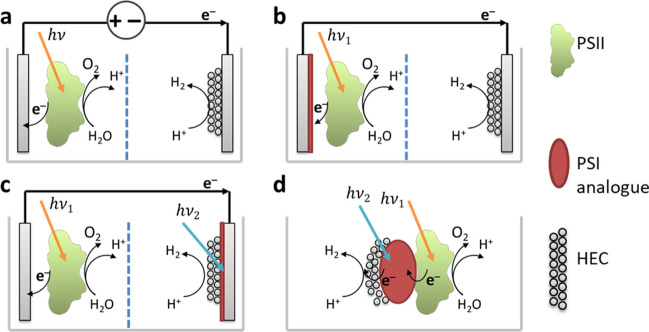

The increase in energy demand and problems related to environmental protection are among the serious problems faced by humanity. The use of more environmentally friendly fuels and methods of their production will reduce the negative impact of the power industry on the environment. Solar radiation is a powerful and stable source of energy, with a capacity of 1.3 × 105 TW. Simultaneously, the total Earth energy demand is 18 TW (Looney 2021). Currently, solar energy has good efficiency indicators, with commercially available silicon solar cells reaching up to 20% (Sopian et al. 2017). Another interesting direction to use solar energy is the creation of artificial photosynthesis systems (APSS) for fuel production. Since photosystem II is the primary point of the proton-coupled electron transport chain, it is considered to be one of the main parts of semiartificial photosynthesizing systems (SAPSS). For efficient hydrogen production, both APSS and SAPSS must contain at least three components: the photoactive component, oxygen evolution catalyst (OEC) and hydrogen evolution catalyst (HEC). PSII contains first (water oxidation cluster) and second (P680), providing rational matching to each other. For overall water splitting, SAPSS can be completed in different ways (Fig. 1): by wiring PSII to an electrode with direct or mediated electron transfer (DET and MET) or by wiring PSII directly to a hydrogen evolution photocatalyst (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Different configurations of SAPSS; photoelectrochemical water splitting (a–c): PSII wiring to HEC by (Mersch et al. 2015) external bias (a), immobilization of PSII on photoanode (Li et al. 2017b; Sokol et al. 2018) (b), and immobilization of HEC on photocathode (Wang et al. 2016) (c). One bulk system (Wang et al. 2014) (d)

The efficiency of PSII-based water splitting SAPSS could theoretically achieve 10.5% (Dau and Zaharieva 2009). Despite the fact that this level has not yet been reached, many PSII-based systems for hydrogen production have been created; thus, 5.4% light conversion is achieved with an applied voltage of 0.8 V at low light (Mersch et al. 2015).

For overall water splitting, the energy gap between hydrogen evolution and the PSII electron acceptor should be bridged (Fig. 2) by external bias (Fig. 1a) or Z-scheme exploitation (Fig. 1b, c). Artificial Z-schemes are inspired by natural photosynthesis: two photons have to be adsorbed per electron by PSII and PSI. The Z-scheme provides reactions with a higher redox potential gap. In semiartificial photosynthesis, PSI can be played by semiconductors (Li et al. 2017b) or sensitizers on the surface of wide band semiconductors such as TiO2 (Rao et al. 1990; Sokol et al. 2018). To provide hydrogen evolution, the catalyst potential must be less than − 0.4 V vs. SHE (at pH = 7, = 101.33 kPa); therefore, to force electron transfer from PSII to hydrogen, according to the overpotential of the catalyst and redox potential of the acceptor from PSII, a 0.4–1 V gap should be bridged. Not only the main components are important for overall performance but also the method of PSII wiring to the electrode.

Fig. 2.

Energy diagram of natural (left) and artificial (right) photosynthesis. The role of PQ can be played by its analogs XQ (DCBQ, DMBQ; or quinone wired to polymer chain); for long distance transfer, POs could be used. Approximately 1 V is needed to force electron transfer from the redox polymer to the hydrogenase, which can be applied by bias or PSI analogs: semiconductors with bands > 1 V (Wang et al. 2016; Li et al. 2017b; Wang et al. 2014) or sensitized semiconductors (Rao et al. 1990; Sokol et al. 2018) such as TiO2

Rational wiring of the photosystem to the electrode for electrochemical water splitting or directly to the hydrogen evolution photocatalyst is critical to obtain high overall performance. Since the first PSII immobilization technique was performed (Rao et al. 1990), several methods have been developed to enhance electron transfer (Badura et al. 2008; Li et al. 2017a; Yehezkeli et al. 2013, 2012), surface area (Kato et al. 2012; Mersch et al. 2015), and oriented immobilization (Badura et al. 2006; Kato et al. 2013). Using a combination of these techniques, the performance of the PSII photoanode can be significantly increased (Mersch et al. 2015; Sakai et al. 2013; Sokol et al. 2018).

Here, we review techniques to enhance SAPSS effectiveness by optimizing each component of the system as electrodes design and redox systems. Finally, SAPSSs for photoelectrochemical production of hydrogen will be considered.

Estimating the effectiveness of water splitting

There are several indicators for performance estimation of the whole semiartificial cell and photoanode in particular (Chen et al. 2010). Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency (STH) characterizes which part of solar energy is converted to Gibbs energy ΔG.

| 1 |

where P is sunlight energy flux, AM1.5 G 100 mW cm-2 is considered to be a standard, but it could be reduced for thin layers, S is the geometrical surface area, E0 is the difference between the redox potential of water splitting and hydrogen evolution (1.23 V at 25 °C), and ηF is the faradaic efficiency for hydrogen evolution. As ηF usually exceeds 90%, current density comparison is common practice. STH is suitable for overall performance estimation and depends on several processes, such as light adsorption, internal quantum yield, and energy difference between levels. If the system requires an external bias to drive water splitting, the efficiency can be examined by the applied bias STH (AB-STH) where Vb is the applied bias.

| 2 |

This equation has one disadvantage: it does not consider that external bias can be applied by photoelements, which can supplement the adsorption spectrum of the PSII electrode.Taking wiring of the enzyme to the electrode into consideration, it is important to obtain the specific current density based on the number of reaction centers (RCs). The concentration of chlorophyll a is given in most works; on the other hand, the RC concentration is often disregarded. The RC concentration can be estimated by division by the number of chlorophyll a molecules per RC if PSII is isolated from cyanobacteria (35 chlorophyll a molecules per RC) (Gisriel et al. 2022; Umena et al. 2011). Turnover frequency can be used to characterize PSII wiring:

| 3 |

where F is the Faraday constant and nPSII is the number of PSII RC per surface area.

Electrode design

There are several substrates used for PSII immobilization: gold, translucent semiconductors such as fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) or indium tin oxide (ITO) and TiO2 (Voloshin et al. 2022; Zhang and Reisner 2019). Electron acceptors such as DCBQ can greatly increase electron transfer rates from PSII to the electrode since access to the RC of PSII is limited. Using diffusible mediators could affect both wiring PSII to the matrix and matrix conduction (Brinkert et al. 2016).

PSII was first immobilized on the electrode by (Rao et al. 1990). Interestingly, the sensitized TiO2 was used to immobilize PSII-enriched membrane particles. Therefore, it could also be considered the first semiartificial electrode that realizes the Z-scheme, although the authors did not investigate the opportunity of using such a scheme for hydrogen production. Authors used Ru (II)L2(L 2,2′-bipyridyl-4,4′-dercaboxylate) as sensitizer. The photobioelectrode with PSII-enriched membranes showed a direct photocurrent of 5 μA cm-2 and a 35 μA cm-2 photocurrent mediated by 400 mM 2,6-dichloro-p-benzoquinone (DCBQ). The direct current of the obtained photoanodes was 12 times higher than the maximum observed for single layers of PSII on flat electrodes in (Kato et al. 2013), which indicates that the electrode had a large real surface affordable for PSII.

Later, several reports were published on PSII monolayer immobilization on a gold electrode (Badura et al. 2006; Maly et al. 2005a). Monolayer PSII is important for understanding the charge transfer process and leaves out the pore sizes and shapes. His-tag is a commonly used purification tag consisting of 6 or more consecutive histidine residues. Including such a tag into the protein of interest by genetic modification allows immobilization of the protein on bivalent Ni or Co atoms in chelating resins such as nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) (Bricker et al. 1998). Therefore, His-tagged PSII can also be immobilized by Ni-NTA (Badura et al. 2006; Maly et al. 2005a). It was shown that mass transport could be difficult for continuous PSII films (Maly et al. 2005a), and a higher current density was detected when bovine serum albumin (BSA) spared PSII films, which facilitated diffusion of the mediator through the protein film. A maximum current density of 0.1 μA cm-2 was achieved with duroquinone as the electron mediator. It should be noted that authors used PSII from Synechococcus elongatus with His-tag at psbC chain, which leads to suboptimal orientation. PSII with a His-tag at CP47 or CP43 is oriented by the stromal side to electrodes, which decreases the distance between the QB site and electrode for better overall performance. The same authors realized another mobilization technique on the basis of poly-mercapto-p-benzoquinone (polyMBQ) electrodeposited on the surface of an Au electrode. polyMBQ played the roles of both redox polymer and immobilization agent by embedding into the QB site. The current densities reached 0.8 μA cm-2 (Maly et al. 2005b)

Next, immobilization enhancement was made by Badura et al. (Badura et al. 2006). Mass transport limitation was overcome by increasing the distance between Ni-NTA chains (Fig. 2a). Thus, the DCBQ MET current density rose to 14 μA cm-2. For more details about immobilization on Au electrodes, see review (Badura et al. 2011). Additionally, covalent immobilization on meso-ITO was performed (Kato et al. 2013) with the highest direct current density of 0.43 μA cm-2 at 0.5 V vs SHE. The self-assembled monolayer on ITO was created by H2O3P(CH2)CO2H. Next, PSII was first oriented by electrostatic interactions on the surface of ITO and then bound with COO- on the surface of the monolayer (Fig. 2c). Using ITO for multilayer immobilization of the photosystem has advantages over Au because of its transparency.

The application of a macropore surface can also be used to increase the current density: the porous nature of the electrode surface leads to a higher load of enzyme. Solid nanoparticles and polymer spheres can be used to quite easily achieve inverse opal ITO structure (Badura et al. 2011; Sokol et al. 2016). Spheres and nanoparticles dispersed in solvent are applied on the surface of the conductive substrate. Dried electrodes are sintered at 450–500 °C (Fig. 3a). The boiling point of polystyrene is 430°, so the sphere matrix is fully evaporated after sintering. For a sphere with a diameter of 750 nm, the size of channels between pores reaches 150 nm, which is enough for PSII to deeply penetrate inside the matrix (Sokol et al. 2016); the real surface area available for PSII contact can be increased 30 times for a 20-μm layer.

Fig. 3.

Immobilization techniques: a Ni-NTA binding with BSA spacers (Maly et al. 2005a), b 1-octanethiol and [16-mercaptohexadecanoic acid -Ni-NTA] (100 : 1 is optimal ratio) binds CPHis43 forming monolayers of PSII (Badura et al. 2006), and c covalent immobilization for DET (Kato et al. 2013); based on provided data

Nanoparticles must meet several requirements to be used in such electrodes. First, they must be translucent enough that light could reach PSII concealed in deep layers of electrodes. For example, ITO nanoparticles can be used in 40-μm layers (Sokol et al. 2016), whereas TiO2 P25 is limited to 20 μm (Sokol et al. 2018). A further thickness increase does not lead to higher current densities because of abundant light flux. Second, the material should have a high conductivity.

Summing up the topic of electrode design, we should admit that both wiring and macroporous design are currently implemented. However, the necessary potential at the anode is more than 0.44 V vs SHE, which significantly reduces HC − STHanode for photoanodes with Os-polymers. Obviously, further discovery of optimal redox polymers and modification of PSII active sites could increase the overall performance and stability of semiartificial photosynthesis.

Redox polymers

The definitive nature and intricate structure of PSII protein complexes are a matter-of-course obstacle to the effective conversion of photoinduced biological potential into electrical current. During the invention of new SAPSSs, one needs to accommodate the physiological incompatibility between external membrane photosensitive complexes and the surfaces of electrodes commonly used for those purposes. The Qb site of PSII is deeply enclosed in its protein structure, which necessitates researchers to find a workaround: other methods of electron transfer via mediated (MET) or direct (DET) electron transfer. DET may become hindered by the poor structural availability of active centers. In this case, the conversion of the photoinduced reduction potential into the energy of chemical reactions or electricity may prove less efficient while interacting with artificially integrated electrical components such as electrodes by means of DET. SAPSS with mediated electron transfer from the active center of the photobiocatalytic complex to the electrode surface seems preferable from this point of view. These systems can be broadly divided into two general subgroups: diffusible mediators and redox-active polymers. The current section will review an application of redox-active polymers for PSII wiring (Fig. 4) and their potential use in SAPSS (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Macroporous electrodes for increased loading of PSII: a scheme of macroporous electrode preparation; after evaporation of the matrix, pores are formed, which enables immobilization of enzyme complexes, membranes and whole cells. (Mersch et al. 2015). b Photocurrent densities of IO-ITO electrodes (based on (Sokol et al. 2016)) for flat, 20, 40, and 80-μm layers of IO-ITO.

Fig. 5.

Progress in wiring PSII to electrodes. Dependence of turnover frequency on applied polymer (left chart): poly(1-vinylimidazole)-Os(bipy)2Cl-polymer (Pos) (Sokol et al. 2016), poly(mercapto-p-benzoquinone) (pMBQ) (Yehezkeli et al. 2012), poly(bis-aniline) (PbANI) (Yehezkeli et al. 2012), poly lysine benzoquinone (pLBQ) (Yehezkeli et al. 2013), direct electron transfer from PSII (DET) (Sokol et al. 2016), polyethyleneglycolmethacrylat (PPhen) (Sokol et al. 2016), poly(1-vinylimidazole)-Os(bipy)2Cl-polymer (Pos) modified with indium tin oxide nanoparticles (ITO) (Lee et al. 2021). Current density for different electrode designs (right chart): golden electrode modified with poly(1-vinylimidazole)-Os(bipy)2Cl-polymer (Pos) (Badura et al. 2008; Hartmann et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020), golden electrode modified with poly(mercapto-p-benzoquinone) (pMBQ) (Yehezkeli et al. 2012), golden electrode modified with poly(bis-aniline) (PbANI) (Yehezkeli et al. 2012), indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode modified with poly lysine benzoquinone (pLBQ) (Yehezkeli et al. 2013), direct electron transfer from PSII to inverse opal/indium tin oxide (IO-ITO) electrode (Sokol et al. 2016), inverse opal/indium tin oxide (IO-ITO) electrode modified with poly(1-vinylimidazole)-Os(bipy)2Cl-polymer (Pos) (Sokol et al. 2016), inverse opal/indium tin oxide (IO-ITO) electrode modified with polyethyleneglycolmethacrylat (PPhen) (Sokol et al. 2016), indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode modified with polypyrrole p-benzoquinone (PPyBQ) (Li et al. 2017a), carbon paper modified with poly(fluorene-co-phenylene) (PFP) (Zeng et al. 2021), graphite electrode modified with poly(1-vinylimidazole)-Os(bipy)2Cl-polymer (Pos) and indium tin oxide (ITO) nanoparticles (Lee et al. 2021) (Supplementary Table 1)

Branched osmium–polymer biocomposites

Osmium is widely used to modify polymer chains such as polyvinylimidazole (PVI) by binding to imidazole heterocycles and organizing compact charged structures branching from the polymer backbone (Aslan et al. 2017). Such a dimensional composition potentially allows the application of nonconductive polymers, allowing electrons to skip from one charged osmium cluster to another, which allegedly creates a more branched network with optimal immobilization of photoactive centers (Fig. 5) (Weliwatte et al. 2021).

In the 2008 article, the research team from Bochum (Badura et al. 2008) applied an Os-modified polymer (Fig. 6) with a redox potential of 0.44 vs. NHE to achieve efficient wiring of PSII to the surface of the Au electrode. Polyethyleneglycol diglycidyl ether (PEGDGE) was applied to cross-link the Os(bpy)2Cl-modified redox-active polymer polyvinylimidazole (Pos) and improve the overall stability of the photoanode. The photocurrent density peaked at 45 μA cm-2 at a potential of + 0.52 V vs. NHE. This article is mainly focused on demonstrating the practical feasibility of the PSII immobilization technique by applying osmium composite as a part of a biocathode element.

Fig. 6.

Redox polymers on energy diagram vs. SHE and structural formula

Hartmann et al. (2018), despite evaluating the preferential D1 variant for a specific thermophilic cyanobacterium, Thermosynechococcus elongatus, still has an interesting observation, which can prove to be useful and supplement the already available results. According to the chronoamperometric results presented in the article, one can notice a significant drop in photocurrent density during the first 200 s of measurement, after which the value stabilizes and remains almost constant over a time span of approximately 30 min. The resulting photocurrent density is approx. 10 μA/cm2. The authors consider this phenomenon to take place due to opportunistic immobilization of PSII on the polymer surface, which in order sets active centers of PSII in suboptimal orientation, leading to ineffective electron transfer distances and swift destabilization and inactivation of PSII redox centers with reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Vöpel et al. 2016).

(Wang et al. 2020), stating the same Pos-based biocomposites, estimates the diverse investment of inhibiting herbicides in the effectiveness of PSII electron transfer routes and the resulting photocurrent densities. 3-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) and 2-tertbutyl-4,6-dinitrophenol (dinoterb) herbicides were used for those purposes. Electrochemical measurements of PSII immobilized on Pos surfaces were conducted on Au electrodes. The resulting photocurrent densities are plausible (Fig. 5) but are impeded low stability. Upon addition of DCMU to the solution, anticipated drop in activity of PSII was observed, however, PSII was able to retain residual activity even at excessive concentration levels of DCMU, sufficient to load all immobilized complexes. According to chronoamperometric measurements (Fig. 5), a significant drop in photocurrent density was observed, which was acknowledged by the authors and explained by the rather thin polymer coating acquired during the tests as well as partial dysfunction of Os centers caused by the peeling of the polymer film.

More ambiguous results were acquired upon the addition of dinoterb to the solution (Fig. 5). The notable increase in current, observed in both chronoamperometric and voltammetry measurements, is not typical for a supposedly inhibiting dopant, so the authors explain it by the possible influence of the deprotonated phenolic species on the polymer film, which favorably affects its dimensional structure and improves the overall stability of polymer films. As a phenolic inhibitor, dinoterb presents a rather low pKa value of 4.80; thus, it is fully deprotonated at pH 6.5, acting as an additional counterion and affecting the degree of swelling and repulsion between electroactive sites. In contrast, DCMU cannot act as a counterion due to the lack of a phenolic AOH function.

In 2016, (Sokol et al. 2016) introduced their own view of a problem of quantitative assessment, characterization and potential applications of several polymer complexes, namely, osmium (Pos)- and phenothiazine (Pphen)-embedded polymers along with vesicular inverse opal/indium tin oxide (IO-ITO) electrodes. The results acquired during the electrochemical measurements approve osmium complexes as a more prospective electron transfer matrix. Despite the redox potential of Pphen being similar to that of plastoquinones A and B, the poor stability of its surface immobilization on IO-ITO electrodes makes Pphen an unsuitable intermediary for electron transfer in comparison with Pos.

This article positively stands out from the line of previous works due to its high reproducibility, in addition to the detailed quantitative characterization through the values of photocurrent density and its relative time degradation for both polymers with and without mediator 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (DCBQ). Most required and wish-to-be mentioned features, such as external quantum efficiency (EQE), turnover frequency (TOF) and surface concentration of active centers (Г) depending on the thickness of the film, were also measured and represented.

Thus far, modification of IO-ITO electrodes with Pos has led to approx. 15-fold increase in EQE (0.3–> 4.4%) and an even better result of 7.7% upon the addition of 1 mM DCBQ to the solution. These results, as well as the significant photocurrent densities acquired in this article, support the beneficial nature of PSII immobilization on the surface of the given Pos-PEGDGE composites and efficient electron transfer pathways between PSII and the positively charged Os3+ branches of the polymer as well as the amino and imidazole groups.

Article published in ChemSusChem in 2021 by (Lee et al. 2021) deserves special mention because instead of PSII active centers, authors apply full-fledged thylakoids. Graphite electrodes modified with ITO nanoparticles and Pos serve as a host. The article showcases fundamental thylakoid applicability for photobioelement construction: the EQEs measured at λ = 430 and 660 nm were 12.2% and 18.5%, respectively. The current density peaked at 497 μA cm-2 with a maximum loading of thylakoid membranes (TM)/Pos/ITOnps of 1140 pmol cm-2. Approximately 41% of this value was provided by MET from the QA site of PSII.

Linear polymer-based biocomposites

A wide variety of redox polymers were applied for the task of wiring electrodes to PSII. One popular strategy consists of the application of polymers containing quinone domains (pQ) (Fig. 6). According to the authors, such a configuration allows the quinone unit of the polymer to enter the QB site of PSII. In this paragraph, we discuss pQ as well as other linear redox polymers.

Studies applying linear polymers usually operate with thin layers, thus restricting their current densities and other electrochemical characteristics. Either, the direct comparison of current densities is not particularly correct due to the difference in materials and loadings of protein, therefore TOF is more significant.

Yehezkeli et al. (2012) operated with gold-plated glass anodes with poly(mercapto-p-benzoquinone) (pMBQ) as an electroconductive polymer in addition to bis-aniline cross-linked Au nanoparticles used as an immobilization matrix for PSII. The photocurrent density was measured as low as 2.6 μA/cm2, TOF = 1.2. Such negligible current densities can be explained differently. First, authors explain such low current densities by ineffective loading of PSII on a polymer surface (1.5 × 10-12 mol/cm2 for pMBQ and only 8.5 × 10-13 mol/cm2 for bis-aniline cross-linked Au nanoparticles) and by suboptimal orientation of PSII reaction sites during immobilization. Second, researchers decided to run electrochemical measurements in such limits of potential that they would still be suitable for bilirubin oxidase (BoX) activity because the main goal was stated as creation of a completed hybrid photovoltaic cell with BoX cathode element, rather than just a top shelf effectiveness PSII-based photoanode. It is possible that if one tries to investigate the same electrochemical setup but in conditions similar to the previously mentioned Pos-modified anodes, one will obtain better microscale photocurrent densities. Thus, pMBQ is a plausible material for electron transfer from the QB site of PSII.

Lower magnitudes were obtained by Li et al. (2017a) in their research on a plausible biohybrid photoanode setup consisting of PSII immobilized on a surface of benzoquinone-doped polypyrrole polymer nanowires (PPyBQ) interconnected with ITO electrodes. The authors managed to obtain photocurrent densities as high as 358 nA/cm2, which is 39 times lower for direct electron transfer between PSII and the electrode.

The honorable mention goes to the 2013 (Yehezkeli et al. 2013) article dedicated to a single-electrode full-body photoelement consisting of a PSII/poly lysine benzoquinone (pLBQ) anodic compound and a PSI/poly-benzylviologen cathodic compound. In addition, some interesting gathered electrochemical data highlight the competitive ability of pLBQ in the field of electron transfer between PSII and the ITO electrode surface. The polymer complex was able to provide 0.5 μA/cm2 at 0.2 V vs. NHE (suboptimal potential), which gives way for further improvement.

Zeng et al. (2021) also acquired potentially applicable and very similar results during their work, considering the combination of photoactive polymer poly(fluorine-co-phenylene) (PFP) and bacterial sites of Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Upon illumination, PFP was able to absorb in the ultraviolet spectrum and further transfer absorbed light to PSII to split water to activate the photosynthetic process. A 53% improvement in oxygen output was observed for Synechococcus/PFP over control cells, whereas PFP alone produced negligible oxygen under the same conditions. The consistent current density estimated at 132 nA/cm2 for PFP-modified Syne (which improved almost twice relative to 71 nA/cm-2 for cells without a polymer) alludes to the possible further increase in MET efficiency and better energy conversion following the replacement of the immobilized agent (Syne) with PSII.

In conclusion, with the aim of targeting improved electrical wiring at interfaces, electroconductive polymers should pursue physiological compatibility with PSII as well as a greater effective surface to complete optimal immobilization of PSII complexes, which has yet to be achieved for both branched Os-polymers and simpler linear polymers due to the opportunistic nature of current PSII immobilization techniques and hampered accessibility of its active center.

Hydrogen evolution reaction

Hydrogen production effectiveness directly correlates with the choice of catalyst immobilized on an electrode surface. It can be platinum, some intricate complexes such as metalorganic frameworks (MOFs) (Budnikova 2020), nanoparticles (Zhu et al. 2020), or hydrogenase complexes (Vincent et al. 2007). The activity of the catalyst depends on the temperature, pH, and effective surface of immobilization (or total number of active sites, as it goes for MOF and hydrogenases). MOF and hydrogenase pore design may also contribute to diffusion, which significantly varies the actual activity. Here, we will discuss the most efficient catalysts from each compound group. It should also be taken into consideration that a correct comparison can be performed only under the same conditions (pH, temperature, medium composition), so the further extrapolation of catalyst characteristics to different conditions may prove to be entirely incorrect. Among the HER characteristics are the overvoltage at a constant current density of 10 μA/cm2, Tafel coefficient, and TOF. The equilibrium potential at the cathode depends on the activity of hydronium ions , molecular hydrogen concentration (H2) and temperature (T), according to the equation:

| 4 |

where E0 stands for NHE.

Electrocatalytic reactions can be described using the Butler–Volmer equation:

| 5 |

where stands for the overvoltage, α is a transfer coefficient, and c1 and c2 are the substrate and product concentrations, respectively. In the case of negligible reverse currents, the total current can be described by the Tafel equation:

| 6 |

where b is the Tafel constant, which can be expressed as For HER/HOR reactions, the effective Tafel constant depends on the catalyst type and catalytic reaction path (Shinagawa et al. 2015).

Thus, the Tafel constant is dependent on the proportion of occupied binding sites θ, which in turn depends on the overvoltage, which can be explained by the two-stage nature of the hydrogen formation (decomposition) process. The first step consists of a potential-dependent adsorption of protons on a catalyst surface (Volmer reaction). The other is altered depending on the process: formation of molecular hydrogen from atoms adsorbed on the surface (Tafel reaction) or potential-dependent desorption (Heyrovsky reaction).

Volmer reaction:

| 7 |

| 8 |

Heyrovsky reaction:

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

Tafel reaction:

Defined by the slowest reaction, different dependences of the current on the overvoltage can be observed (Shinagawa et al. 2015).

Volmer:

| 12 |

Heyrovsky:

| 13 |

Tafel:

| 14 |

where k and k-1 are the rates of forward and reverse reactions, respectively, f = F/RT. Thus, the Tafel constants are estimated to be 30, 40, and 120 mV under standard conditions and α = 0.5. Accordingly, the “bottleneck” reaction can be estimated by those values.

The lowest Tafel constant is 30 mV, which directs us to platinum and some other catalysts operating at the same constant in acidic environments. In the case of MOF and hydrogenase, the determining reactions are the Volmer or Heyrovsky. The power of catalytic activity is to a large extent determined by the enthalpy of hydrogen ion binding to the catalyst. The best activity according to the Sabatier principle is shown by compounds that show closest to zero values of ΔGH. Among pure metals, platinum and palladium demonstrate the highest catalytic activity. At the same time, graphitized carbon nanoparticles coated with platinum (20% Pt/C) are already used in fuel cells due to their high activity and serve as a reference standard. Reducing the size of nanoparticles makes it possible to increase the effective catalytic surface area; however, as shown in (Tan et al. 2015), Pt faces rather than edges exhibit catalytic activity; therefore, a farther size decrease below the limit of 2 nm impairs the catalytic activity. Ruthenium nanoparticles are a less expensive platinum alternative. Nevertheless, ruthenium nanoparticles bound in C2N (Ru@C2N) layers exhibit high activity and are stable over a wide pH range (Mahmood et al. 2017), which is vital for hybrid system applications.

Transition metal compounds can be used as catalysts instead of noble metals. Their catalytic activity in order of decrease is Ni > Mo > W > Fe > Cu (Mahmood et al. 2017). In recent decades, catalysts based on transition metals comparable to 20% Pt/C have been obtained. Additionally, depending on the ligands, ΔGH of the compound can approach zero. Nickel nanorods coated with NiP2 exhibit a high catalytic activity. Additional coating with ruthenium makes it possible to obtain even higher activity similar to that of commercial 20% Pt/C (Liu et al. 2018). Plausible activity is also demonstrated by Ni-Cu nanoparticles enclosed in graphene monolayers. Ni, Mo and oxygen nanoalloys demonstrate record activity, but they are hindered by extremely low stability.

In addition to nanoparticles, MOF-based HER catalysts have been developed (see review Budnikova 2020). Several MOF catalysts with a Tafel constant less than 90 mV stand out among the others: 3D MOFs based on ferrocenyl diphosphates and 4,4′ bipyridine ligands (3D NibpyfcdHp and 3D CobpyfcdHp) show good stability and a Tafel constant of 60 mV for Ni and 65 mV for Co in 0.5 M H2SO4 (Khrizanforova et al. 2020). Additionally, it is worth mentioning hexaiminohexaazatrinaphthalene (HAHATN) compounds, in which the transition metal atoms are bonded by two and four N-groups, as well as the Ni compounds Ni3(Ni3HAHATN)2, which demonstrate the maximum activity (Tafel constant for Ni compounds is 45.6 mV in 0.1 M KOH) (Huang et al. 2020). The cascade structure has large hexagonal pores that facilitate diffusion to NiN2 catalytic sites. An overvoltage of η10 = 120 mV makes Ni3(Ni3HAHATN)2 a promising catalyst for hydrogen-producing hybrid cell applications. Ni can also be a part of some hydrogenases.

Another alternative for catalysts in photoelectrochemical hydrogen production is hydrogenase. Hydrogenase is the enzyme catalyzing the activation of molecular hydrogen. In spite of the simplest molecule in nature, H2, scientists have already found that microorganisms have created more than 3.5 thousand different genes for hydrogenase coding (Søndergaard et al. 2016). The modern classification of hydrogenases is based on the metal content in the active center, phylogeny, peculiarities of gene organization, physiological function inside cells, and natural electron donors/acceptors (see review Greening et al. 2015). In accordance with this classification, hydrogenases are separated into NiFe, FeFe, and Fe hydrogenases.

Enzymes from the last group, Fe hydrogenases, are very specific in electron donors (Buurman G, Shima S, Thauer RK (2000) The metal-free hydrogenase from methanogenic archaea: evidence for a bound cofactor. Febs Letters 485(2-3): 200-204.) and are not used in electrochemical research.

Among FeFe hydrogenases, one can find different structures, starting from one-subunit to four-subunit structures (see review Vignais and Billoud 2007). Recombinant Clostridium acetobutylicum FeFe hydrogenase expressed in E. coli was immobilized on anatase TiO2 for hydrogen evolution (Morra et al. 2011). FeFe hydrogenases consist of only one subunit, as in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Forestier et al. 2003) and Desulfovibrio fructosovorans (Jacq-Bailly et al. 2021), which are the enzymes with the highest specific activity in hydrogen production reactions of 750 and 50 μmol [H2] mg-1[H2ase] min-1 for the HOR and HER, respectively. That is why these enzymes are very interesting in electrochemical hydrogen production in PSII-based SAPSS. Fe However, due to the very high sensitivity of these enzymes to the toxic action of oxygen, wiring them to electrodes and stabilizing their activity is still under basic research.

NiFe hydrogenases are the most diverse class. They are divided into 4 groups (Greening et al. 2015). The first two groups present hydrogen uptake membrane-bound or cytosolic hydrogenses. However, different examples are very promising in hydrogen-producing electrochemical activity. For example, hydrogen uptake hydrogenases from Desulfovibrio vulgaris, Desulfomicrobium baculatum, and Aquifex aeolicus have been actively studied in bioelectrochemical research. Moreover, hydrogenases from Aquifex aeolicus (Luo et al. 2009) and from Thiocapsa bogorovii (Tsygankov et al. 2023, in press) are very stable and active at high (up to 80 °C) temperatures.

[NiFeSe]-hydrogenase from Desulfomicrobium baculatum (Nam et al. 2018; Reisner et al. 2009; Sakai et al. 2013; Zhang and Reisner 2019) is well known for its high oxygen tolerance and good performance and is most commonly used in hydrogen-producing photoelectrochemical cells (Evans et al. 2021; Schäfer et al. 2013), but [NiFeSe]-hydrogenases from Desulfomicrobium baculatum, Desulfovibrio vulgaris Miyazaki F (Kaur 2020), and D. vulgaris Hildenborough (Marques et al. 2017) are the ones to be studied the most.

One could suggest that the application of hydrogenases to practical bioelectrochemistry is just a question of scientific interest. However, the hydrogenase from Cytrobacter S77 was shown to surpass Pt in HOR electrochemical activity (Matsumoto et al. 2014). IO-mesoITO, which was used for mediated PSII wiring, was used for direct immobilization of NiFeSe hydrogenase from Desulfomicrobium baculatum, showing a current density of 1 mA at an overpotential of 146 mV. It should be noted that such a hydrogen cathode demonstrated non-Tafel kinetics: the current density increased almost linearly for overvoltages from 46 to 246 mV. Additionally, hydrogenases were used to construct hybrid photocatalysts by immobilizing them on sensitized semiconductor surfaces (Reisner et al. 2009) and directly to sensitizers (Zadvornyy et al. 2012).

Hydrogenases, like other electroactive enzymes, can be immobilized on the electrode surface by physical adsorption, covalent binding, entrapment in a conductive (often electroactive) matrix, and cross-linking (Xiao et al. 2019). All methods proved to be useful for different hydrogenases, but the immobilization of a particular enzyme on the electrode surface is often challenging and requires particular investigation. Nevertheless, oriented immobilization of hydrogenases provides high activity (up to a dozen mA/cm2 (So et al. 2016)).

Unlike artificial catalysts, hydrogenases immobilized on electrodes have a very small range of exponential current growth due to overvoltage (Mersch et al. 2015; also see review Vincent et al. 2007). HAHATN and Ru@C2N catalysts demonstrate severely larger activity. Nevertheless, a great number of hybrid cell papers have chosen hydrogenases as HER catalysts (Mersch et al. 2015; Sakai et al. 2013; Sokol et al. 2018), as the activity in such SAPSSs is mostly limited by the wiring of PSII.

Hybrid systems

Effective immobilization and wiring techniques have enabled the construction of hydrogen evolution systems. In 2015, (Mersch et al. 2015) presented IO-mesoITO|PSII|Nafion|H2ase| IO-mesoITO. PSII was immobilized on a macroporous ITO (40 μm), which allowed an increase in current densities of 20 μA cm-2 for DET and 0.93 mA cm-2 for DCBQ-mediated ET. The hydrogenase electrode gave 2 mA cm-2 for the 20 μm layer at − 0.6 V vs SHE. For overall water splitting, a 20 μm IO-ITO layer for PSII and a 12-μm H2ase electrode were used. The cell showed a current density of 450 μA cm-2 at 0.9 V (AB − STH = 1.5% at this bias). AB-STH was significantly improved at low light 5.4% at U = 0.8 This may indicate that multilayer cells would give rise to overall performance.

Bias-free overall water splitting was a next step in the development of PSII-based cells. To maximize the Z-scheme performance, adsorption specters of PSII and PSI analogs should have low overlap; otherwise, whole cell performance would be the product of individuals. The role of PSI may be played by semiconductors with an appropriate energy structure: the valence band (VB) should be above 0.44 V vs SHE (for the Os redox polymer), and the conduction band (CB) should be below − 0.5 V. Sensitized wideband semiconductors such as TiO2 can also be used as an alternative. Moreover, water splitting can be implemented not only in electrochemical cells but also by direct wiring of PSII to HEP.

Thus, PSII-enriched membranes were coupled to the artificial photocatalyst Ru2S3/CdS or Ru/SrTiO3:Rh with an inorganic electron shuttle [/] (FeCy) (Wang et al. 2014). PSII-enriched membrane fragments were bound to the surface of Ru/SrTiO3:Rh particles by hydrophilic interactions, while the contact angle between PSII and Ru2S3/CdS was 90° due to the hydrophobic nature of CdS. This is one of the reasons for the better performance of Ru/SrTiO3:Rh 2500 mol[H2] mol[PSII]-1h-1 against 1400 mol[H2] mol[PSII]-1h-1 of Ru2S3/CdS. Based on the data, the provided STH of the system was limited by 0.06%.

Bias-free electrochemical water splitting was performed by (Wang et al. 2016). The feature of the mentioned cell consists of the photocatalyst used at the cathode: a transparent double-junction Si solar cell decorated with Pt. The PSII solution with FeCy was separated from Si|Pt by Nafion. The efficiency of STH is 0.29%. It is worth noting here that wiring Si solar cells to the electrolyzer with Pt electrodes could give 7% STH.

PSII-enriched membranes were used in (Li et al. 2017b). 2,6-Dimethyl-benzoquinone was used to couple PSII with a graphite electrode, which was connected to an FeCy solution cell with CdS nanoparticles deposited on an FTO substrate (Fig. 7). CdS was connected by wire to Pt to perform overall water splitting with an STH of 0.34%. Light consistently passed CdS and PSII bulk. CdS adsorbs light up to 550-nm CdS, so red light is available for PSII. A stable current density of 0.3 mA cm2 was achieved wheras simple coupling of PSII to CdS resulted in a photocurrent drop, which could be caused by adsorption of PSII-enriched membranes onto CdS blocking oxidation active sites or side effects. A two-electrode photoelectrochemical cell (PEC) CdS|FeCy4-/ FeCy3-, Nafion, and H+/H2|Pt was also ivestigated by itself with FeCy3- acting as a sacrificial electron donor. The incident photon-to-current efficiency (ICPE) reached 25% near 420 nm at 0.3 mA cm-2 with ηF 100%. The cell was illuminated by 100 mW cm-2, which is 10 times higher than the standard. As shown (Mersch et al. 2015), the effectiveness of such cells could drop with increasing light intensity. Additionally, we have to note the good stability of the system for an hour. This work is important for understanding multijunction systems. Using an additional semiconductor layer on the surface of CdS may play the same role as FeCy solution cells.

Fig. 7.

Bias-free hydrogen production with PSII-enriched membrane fragments (Li et al. 2017b) a scheme of cell: Pt is separated from PSII bulk by Nafion membrane, charge from PSII transfers to graphite electrode with DMBQ/DMBQH2, FeCy is mediator between graphite and CdS surface. b Energy diagram of the cell

Immobilized PSII for bias-free water splitting was performed by (Sokol et al. 2018). PSII was wired with POs to IO-mesoTiO2|FTO sensitized with diketopyrrolopyrrole (dpp) or ruthenium bis(2,2′-bipy)(4,4′-bis(phosphonic acid)-2,2′-bipy) dibromide dye (RuP). IO-mesoTiO2 was connected by wire to the cathode IO-mesoITO with immobilized H2ase. The best STH was achieved with RuP 28 μA cm-2 with a low stability half-life time of 6.5 min. This work is a proof of concept, although the low stability of isolated PSII must be admitted.

Conclusions

The effective design of the electrodes made it possible to increase the current density of the photoanode, both due to the larger surface area of the electrode (Mersch et al. 2015; Sakai et al. 2013; Sokol et al. 2016) and due to the oriented immobilization of the enzyme(Badura et al. 2006; Kato et al. 2013; Maly et al. 2005b). Redox polymers, such as Os (Sokol et al. 2018, 2016) and benzoquinone derivatives (Maly et al. 2005b; Yehezkeli et al. 2013, 2012), also played an important role in increasing the current density. At the same time, the latter also allows to immobilize PSII by interacting with the QB site. A wide range of hydrogen catalysts allows the use of both platinum and compounds without noble metals, such as MOF (Huang et al. 2020; Khrizanforova et al. 2020). In addition, hydrogenases are a good alternative due to the possibility of direct electron transfer to the cathode (Mersch et al. 2015; Sakai et al. 2013; Sokol et al. 2018; Xiao et al. 2019). Understanding hybrid systems allowed to create SAPSS capable of producing hydrogen with a low external voltage (Mersch et al. 2015). Moreover, the implementation of the Z-scheme made it possible to obtain hydrogen without external voltage (Li et al. 2017b; Sokol et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2014).

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of such systems remains at a low level. Despite the progress in wiring PSII by redox polymers, TOF remains higher with the addition of mediators such as DCBQ (Sokol et al. 2016), which suggests that there is room to develop redox polymers. On the other hand, the loading of PSII is limited, both due to the attenuation of light and the increase in the resistance of porous layers with increasing layer thickness (Mersch et al. 2015; Sokol et al. 2018). The obvious bottleneck in using PSII in such systems is its extremely low stability. The use of redox polymers makes it possible to significantly increase the lifetime of the enzyme; in addition, the use of PSII membrane fragments enriched with PSII, such as BBY, also gives a significant increase in stability (Li et al. 2017b; Rao et al. 1990). Additionally, osmolytes can be used (Voloshin et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the use of PSII in industrial systems seems unlikely, although the creation of such systems made it possible to work out many stages of artificial photosynthesis. As an alternative, artificial systems can act, which have much higher stability. However, such systems can be commercially in demand only at a significantly lower cost compared to solar cells. New catalysts allow the replacement of rare Pt and Ir materials from earth abundant elements, which are traditional in water electrolysis. Therefore, (Ramakrishnan et al. 2022) NiFe oxide on a highly porous N-doped carbon nanosheet both for the anode and cathode shows better activity than Pt|IrO2 at potentials higher than 1.7 V, which corresponds to 72% efficiency. Combined with solar cells, the overall SHE will achieve more than 10%.

On the other hand, the immobilization of PS II can be useful for use in sensors and other devices that do not require a long lifetime (Çakıroğlu et al. 2023; Maly et al. 2005a). Moreover, the electrochemistry of PSII-containing preparations is a valuable method for investigating the fundamental mechanisms of charge separation and transfer.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Review and the description of redox polymers used for PSII wiring to electrodes were done by Sergey Bushnev. Review and the description of hydrogenases were done by Anatoly Tsygankov and Ivan Doronin. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ivan Doronin. Raif Vasilov and Anatoly Tsygankov revised the work and edited the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (RSF 19-14-00255).

Declarations

Ethical approval

This is not applicable.

Consent to participate

This is not applicable.

Consent for publication

This is not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aslan S, Conghaile P, Leech D, Gorton L, Timur S, Anik U. Development of an osmium redox polymer mediated bioanode and examination of its performance in Gluconobacter oxydans based microbial fuel cell. Electroanalysis. 2017;29:1651–1657. doi: 10.1002/elan.201600727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badura A, Esper B, Ataka K, Grunwald C, Wöll C, Kuhlmann J, Heberle J, Rögner M. Light-Driven Water Splitting for (Bio-)Hydrogen production: photosystem 2 as the central part of a bioelectrochemical device. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:1385. doi: 10.1562/2006-07-14-rc-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badura A, Guschin D, Esper B, Kothe T, Neugebauer S, Schuhmann W, Rögner M. Photo-induced electron transfer between photosystem 2 via cross-linked redox hydrogels. Electroanalysis. 2008;20:1043–1047. doi: 10.1002/elan.200804191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badura A, Kothe T, Schuhmann W, Rögner M (2011) Wiring photosynthetic enzymes to electrodes. Energy Environ Sci. 10.1039/c1ee01285a

- Bricker TM, Morvant J, Masri N, Sutton HM, Frankel LK, (1998) Isolation of a highly active Photosystem II preparation from Synechocystis 6803 using a histidine-tagged mutant of CP 47. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 1409, 50–57. 10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00148-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brinkert K, Le Formal F, Li X, Durrant J, William Rutherford A, Fantuzzi A. Photocurrents from photosystem II in a metal oxide hybrid system: electron transfer pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2016;1857:1497–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnikova YH. Recent advances in metal-organic frameworks for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution and overall water splitting reactions. Dalton Transactions. 2020;49:12483–12502. doi: 10.1039/d0dt01741h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çakıroğlu B, Jabiyeva N, Holzinger M (2023) Photosystem II as a chemiluminescence-induced photosensitizer for photoelectrochemical biofuel cell-type biosensing system. Biosens Bioelectron 226. 10.1016/j.bios.2023.115133 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Jaramillo TF, Deutsch TG, Kleiman-Shwarsctein A, Forman AJ, Gaillard N, Garland R, Takanabe K, Heske C, Sunkara M, McFarland EW, Domen K, Milled EL, Dinh HN (2010) Accelerating materials development for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production: standards for methods, definitions, and reporting protocols. J Mater Res. 10.1557/jmr.2010.0020

- Dau H, Zaharieva I. Principles, efficiency, and blueprint character of solar-energy conversion in photosynthetic water oxidation. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:1861–1870. doi: 10.1021/ar900225y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM, Krahn N, Murphy BJ, Lee H, Armstrong FA, Söll D. Selective cysteine-to-selenocysteine changes in a [NiFe]-hydrogenase confirm a special position for catalysis and oxygen tolerance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118:e2100921118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2100921118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestier M, King P, Zhang L, Posewitz M, Schwarzer S, Happe T, Ghirardi ML, Seibert M. Expression of two [Fe]-hydrogenases in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under anaerobic conditions. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2750–2758. doi: 10.1046/J.1432-1033.2003.03656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisriel CJ, Wang J, Liu J, Flesher DA, Reiss KM, Huang H-L, Yang KR, Armstrong WH, Gunner MR, Batista VS, Debus RJ, Brudvig GW. High-resolution cryo-electron microscopy structure of photosystem II from the mesophilic cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022;119:1–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116765118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening C, Biswas A, Carere CR, Jackson CJ, Taylor MC, Stott MB, Cook GM, Morales SE (2015) Genomic and metagenomic surveys of hydrogenase distribution indicate H2 is a widely utilised energy source for microbial growth and survival. The ISME Journal 2016 10:3 10, 761–777. 10.1038/ismej.2015.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hartmann V, Ruff A, Schuhmann W, Rögner M, Nowaczyk MM. Analysis of photosystem II electron transfer with natural PsbA-variants by redox polymer/protein biophotoelectrochemistry. Photosynthetica. 2018;56:229–235. doi: 10.1007/s11099-018-0775-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Zhao Y, Bai Y, Li F, Zhang Y, Chen Y. Conductive metal–organic frameworks with extra metallic sites as an efficient electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Advanced Science. 2020;7:1–9. doi: 10.1002/advs.202000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacq-Bailly A, Benvenuti M, Payne N, Kpebe A, Felbek C, Fourmond V, Léger C, Brugna M, Baffert C. Electrochemical Characterization of a complex FeFe hydrogenase, the electron-bifurcating Hnd from Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. Front Chem. 2021;8:573305. doi: 10.3389/FCHEM.2020.573305/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Cardona T, Rutherford AW, Reisner E. Covalent immobilization of oriented photosystem II on a nanostructured electrode for solar water oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10610–10613. doi: 10.1021/ja404699h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Cardona T, Rutherford AW, Reisner E. Photoelectrochemical water oxidation with photosystem II Integrated in a mesoporous indium–tin oxide electrode. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8332–8335. doi: 10.1021/ja301488d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khrizanforova V, Shekurov R, Miluykov V, Khrizanforov M, Bon V, Kaskel S, Gubaidullin A, Sinyashin O, Budnikova Y. 3D Ni and Co redox-active metal-organic frameworks based on ferrocenyl diphosphinate and 4,4′-bipyridine ligands as efficient electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Dalton Transactions. 2020;49:2794–2802. doi: 10.1039/c9dt04834k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur AP (2009) Genetic and molecular characterizations of hydrogenases and sulfate metabolism proteins of Desulfovibrio vulgaris Miyazaki F. Inaugural dissertation for the doctoral degree. The Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf

- Lee J, Shin H, Kang C, Kim S. Solar energy conversion through thylakoid membranes wired by osmium redox polymer and indium tin oxide nanoparticles. ChemSusChem. 2021;14:2216–2225. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202100288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Feng X, Fei J, Cai P, Li J, Huang J, Li J (2017a) Interfacial assembly of photosystem II with conducting polymer films toward enhanced photo-bioelectrochemical cells. Adv Mater Interfaces 4. 10.1002/admi.201600619

- Liu Y, Liu S, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Gu L, Zhao S, Xu D, Li Y, Bao J, Dai Z. Ru Modulation effects in the synthesis of unique rod-like Ni@Ni2P-Ru heterostructures and their remarkable electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140:2731–2734. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wang W, Ding C, Wang Z, Liao S, Li C. Biomimetic electron transport via multiredox shuttles from photosystem II to a photoelectrochemical cell for solar water splitting. Energy Environ Sci. 2017;10:765–771. doi: 10.1039/c6ee03401b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Looney B (2021) bp Statistical review of world energy 2021. https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-full-report.pdf

- Luo X, Brugna M, Tron-Infossi P, Giudici-Orticoni MT, Lojou É. Immobilization of the hyperthermophilic hydrogenase from Aquifex aeolicus bacterium onto gold and carbon nanotube electrodes for efficient H2 oxidation. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2009;14:1275–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0572-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood J, Li F, Jung SM, Okyay MS, Ahmad I, Kim SJ, Park N, Jeong HY, Baek JB. An efficient and pH-universal ruthenium-based catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12:441–446. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly J, Krejci J, Ilie M, Jakubka L, Masojídek J, Pilloton R, Sameh K, Steffan P, Stryhal Z, Sugiura M (2005a) Monolayers of photosystem II on gold electrodes with enhanced sensor response-effect of porosity and protein layer arrangement. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry.:1558–1567. 10.1007/s00216-005-3149-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maly J, Masojidek J, Masci A, Ilie M, Cianci E, Foglietti V, Vastarella W, Pilloton R. Direct mediatorless electron transport between the monolayer of photosystem II and poly(mercapto-p-benzoquinone) modified gold electrode - new design of biosensor for herbicide detection. Biosens Bioelectron. 2005;21:923–932. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques MC, Tapia C, Gutiérrez-Sanz O, Ramos AR, Keller KL, Wall JD, De Lacey AL, Matias PM, Pereira IAC. The direct role of selenocysteine in [NiFeSe] hydrogenase maturation and catalysis. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:544–550. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T, Eguchi S, Nakai H, Hibino T, Yoon K-S, Ogo S. [NiFe]Hydrogenase from Citrobacter sp. S-77 Surpasses platinum as an electrode for H 2 oxidation reaction. Angewandte Chemie. 2014;126:9041–9044. doi: 10.1002/ange.201404701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersch D, Lee CY, Zhang JZ, Brinkert K, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Rutherford AW, Reisner E. Wiring of photosystem II to hydrogenase for photoelectrochemical water splitting. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8541–8549. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morra S, Valetti F, Sadeghi SJ, King PW, Meyer T, Gilardi G. Direct electrochemistry of an FeFe-hydrogenase on a TiO2 electrode. Chemical Communications. 2011;47:10566–10568. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14535e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam DH, Zhang JZ, Andrei V, Kornienko N, Heidary N, Wagner A, Nakanishi K, Sokol KP, Slater B, Zebger I, Hofmann S, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Park CB, Reisner E. Solar water splitting with a hydrogenase integrated in photoelectrochemical tandem cells. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. 2018;57:10595–10599. doi: 10.1002/anie.201805027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan S, Velusamy DB, Sengodan S, Nagaraju G, Kim DH, Kim AR, Yoo DJ. Rational design of multifunctional electrocatalyst: an approach towards efficient overall water splitting and rechargeable flexible solid-state zinc–air battery. Appl Catal B. 2022;300:120752. doi: 10.1016/J.APCATB.2021.120752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao KK, Hall DO, Vlachopoulos N, Grätzel M, Evans MCW, Seibert M. Photoelectrochemical responses of photosystem II particles immobilized on dye-derivatized TiO2 films. J Photochem Photobiol, B. 1990;5(3–4):379–389. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(90)85052-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner E, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Armstrong FA (2009) Catalytic electrochemistry of a [NiFeSe]-hydrogenase on TiO2 and demonstration of its suitability for visible-light driven H2 production. Chem comm:550–552. 10.1039/b817371k [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sakai T, Mersch D, Reisner E. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution with a hydrogenase in a mediator-free system under high levels of oxygen. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. 2013;52:12313–12316. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer C, Friedrich B, Lenza O. Novel, oxygen-insensitive group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase in Ralstonia eutropha. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5137–5145. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01576-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinagawa T, Garcia-Esparza AT, Takanabe K. Insight on Tafel slopes from a microkinetic analysis of aqueous electrocatalysis for energy conversion. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–21. doi: 10.1038/srep13801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So K, Kitazumi Y, Shirai O, Nishikawa K, Higuchi Y, Kano K. Direct electron transfer-type dual gas diffusion H2/O2 biofuel cells. J Mater Chem A Mater. 2016;4:8742–8749. doi: 10.1039/c6ta02654k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol KP, Mersch D, Hartmann V, Zhang JZ, Nowaczyk MM, Rögner M, Ruff A, Schuhmann W, Plumeré N, Reisner E. Rational wiring of photosystem II to hierarchical indium tin oxide electrodes using redox polymers. Energy Environ Sci. 2016;9:3698–3709. doi: 10.1039/c6ee01363e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol KP, Robinson WE, Warnan J, Kornienko N, Nowaczyk MM, Ruff A, Zhang JZ, Reisner E. Bias-free photoelectrochemical water splitting with photosystem II on a dye-sensitized photoanode wired to hydrogenase. Nat Energy. 2018;3:944–951. doi: 10.1038/s41560-018-0232-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Søndergaard D, Pedersen CNS, Greening C (2016) HydDB: A web tool for hydrogenase classification and analysis. Scientific Reports 2016 6:1 6, 1–8. 10.1038/srep34212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sopian K, Cheow SL, Zaidi SH (2017) An overview of crystalline silicon solar cell technology: past, present, and future, in: AIP Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Physics Inc. 10.1063/1.4999854

- Tan TL, Wang LL, Zhang J, Johnson DD, Bai K. Platinum nanoparticle during electrochemical hydrogen evolution: adsorbate distribution, active reaction species, and size effect. ACS Catal. 2015;5:2376–2383. doi: 10.1021/cs501840c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen JR, Kamiya N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9Å. Nature. 2011;473:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignais PM, Billoud B. Occurrence, classification, and biological function of hydrogenases: an overview. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4206–4272. doi: 10.1021/cr050196r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent KA, Parkin A, Armstrong FA. Investigating and exploiting the electrocatalytic properties of hydrogenases. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4366–4413. doi: 10.1021/cr050191u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voloshin RA, Brady NG, Zharmukhamedov SK, Feyziyev YM, Huseynova IM, Najafpour MM, Shen JR, Veziroglu TN, Bruce BD, Allakhverdiev SI. Influence of osmolytes on the stability of thylakoid-based dye-sensitized solar cells. Int J Energy Res. 2019;43:8878–8889. doi: 10.1002/er.4866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voloshin RA, Shumilova SM, Zadneprovskaya EV, Zharmukhamedov SK, Alwasel S, Hou HJM, Allakhverdiev SI. Photosystem II in bio-photovoltaic devices. Photosynthetica. 2022;60:121–135. doi: 10.32615/ps.2022.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vöpel T, Ning Saw E, Hartmann V, Williams R, Müller F, Schuhmann W, Plumeré N, Nowaczyk M, Ebbinghaus S, Rögner M. Simultaneous measurements of photocurrents and H 2 O 2 evolution from solvent exposed photosystem 2 complexes. Biointerphases. 2016;11:019001. doi: 10.1116/1.4938090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Zhao F, Hartmann V, Nowaczyk MM, Ruff A, Schuhmann W, Conzuelo F (2020) Reassessing the rationale behind herbicide biosensors: the case of a photosystem II/redox polymer-based bioelectrodefs. Bioelectrochemistry 136. 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2020.107597 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang W, Chen J, Li C, Tian W. Achieving solar overall water splitting with hybrid photosystems of photosystem II and artificial photocatalysts. Nat Commun. 2014;5:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Wang H, Zhu Q, Qin W, Han G, Shen J, Zong X, Li C. Spatially separated photosystem II and a silicon photoelectrochemical cell for overall water splitting: a natural–artificial photosynthetic hybrid. Angewandte Chemie. 2016;128:9375–9379. doi: 10.1002/ange.201604091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weliwatte NS, Grattieri M, Minteer SD (2021) Rational design of artificial redox-mediating systems toward upgrading photobioelectrocatalysis. Photochemical and Photobiological Sciences. 10.1007/s43630-021-00099-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xiao X, Xia HQ, Wu R, Bai L, Yan L, Magner E, Cosnier S, Lojou E, Zhu Z, Liu A. Tackling the challenges of enzymatic (bio)fuel cells. Chem Rev. 2019;119:9509–9558. doi: 10.1021/ACS.CHEMREV.9B00115/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/CR-2019-001152_0023.JPEG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehezkeli O, Tel-Vered R, Michaeli D, Nechushtai R, Willner I. Photosystem i (PSI)/Photosystem II (PSII)-based photo-bioelectrochemical cells revealing directional generation of photocurrents. Small. 2013;9:2970–2978. doi: 10.1002/smll.201300051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehezkeli O, Tel-Vered R, Wasserman J, Trifonov A, Michaeli D, Nechushtai R, Willner I (2012) Integrated photosystem II-based photo-bioelectrochemical cells. Nat Commun 3. 10.1038/ncomms1741 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zadvornyy OA, Lucon JE, Gerlach R, Zorin NA, Douglas T, Elgren TE, Peters JW. Photo-induced H2 production by [NiFe]-hydrogenase from T. roseopersicina covalently linked to a Ru(II) photosensitizer. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;106:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Zhou X, Qi R, Dai N, Fu X, Zhao H, Peng K, Yuan H, Huang Y, Lv F, Liu L, Wang S (2021) Photoactive conjugated polymer-based hybrid biosystems for enhancing cyanobacterial photosynthesis and regulating redox state of protein. Adv Funct Mater 31. 10.1002/adfm.202007814

- Zhang JZ, Reisner E (2019) Advancing photosystem II photoelectrochemistry for semi-artificial photosynthesis. Nat Rev Chem 4. 10.1038/s41570-019-0149-4

- Zhu J, Hu L, Zhao P, Lee LYS, Wong KY. Recent advances in electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution using nanoparticles. Chem Rev. 2020;120:851–918. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.