Abstract

Moderately advanced (stage III) and advanced (stage IV a & b) OSMF requires surgical intervention for management A number of options are available for reconstruction of post OSMF oral cavity defects. In our study we retrospectively compared buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap and platysma flap for reconstruction of the buccal mucosal defects. Patient records were obtained from the medical records section of the Institute and divided into three groups; group A (buccal fat pad), group B (nasolabial group) and group C (platysma flap). Maximal mouth opening and intercommisural distance were the primary outcomes. Kruskal Wallis test was used to test the mean difference between three groups. Mann–Whitney test was used for intergroup comparisons. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate the mean difference in outcomes at each follow up interval. A p value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant at 95% confidence interval. After 1 year follow up patients in platysma group had significantly better mouth opening (39.84 ± 1.65 mm) compared to both buccal fat pad (36.69 ± 3.41 mm) and nasolabial groups (37.94 ± 0.43 mm). Inter commisural distance was significantly better in patients reconstructed with platysma flap (59.21 ± 0.99 mm) compared to both buccal fat pad (54.11 ± 1 mm) and nasolabial flap (56.84 ± 1.48 mm). Platysma flap lead to significantly better maximal mouth opening compared to both nasolabial and buccal fat pad. Both buccal fat pad and nasolabial lead to comparable mouth opening. Inter commissural distance is maximum with platysma flap followed by nasolabial flap and buccal fat pad.

Keywords: Oral submucous fibrosis, Buccal fat pad, Nasolabial flap, Platysma flap, Oral cavity reconstruction

Introduction

Rationale

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a chronic progressive and scarring disease characterized by abnormal collagen deposition. It is particularly widespread in South East Asia because of areca nut chewing. OSMF is a precancerous disease and the malignant potential has ranged from 1.5 to 30% [1–3]. Most cases of OSMF are seen in middle aged individuals, however; Pediatric OSMF is a newer challenging entity with 16.6% of cases in some western countries [4]. The etiology is multifactorial with Areca nut chewing, nutritional deficiencies, stress, genetic predisposition being most common [1, 2, 5]. The management of OSMF is stage dependent, better prognosis with early diagnosis. Detection at an early stage may be managed with only habit cessation. However, moderate to advanced stage disease may require medical and surgical intervention [6].

Surgical therapy includes simple excision of fibrous bands; excision with temporalis myotomy and coronoidectomy followed by reconstruction with buccal fat pad (BFP), NLF (Nasolabial Flap), skin grafts, free flaps, platelet rich fibrin, temporalis fascia, platysma myocutaneous flap etc. [6–10]. Studies comparing BFP and NLF gave equally good results with most studies favoring BFP over NLF owing to its ease of harvest and fewer complications [11, 12]. However, studies have also favored NLF over BFP in reconstruction of OSMF defects [13]. Quality of Life Assessment in patients suffering from OSMF have shown a significant deterioration compared to normal individuals [14, 15]. Studies evaluating QOL (quality of life) with nasolabial flap in oral cavity reconstruction showed favorable results in terms of improved mouth opening.

Platysma myocutaneous flap (PMF) is an axial pattern flap with advantages of having minimum donor site morbidity, appropriate flap thickness for intra oral defects and minimum scarring. Studies have shown its effectiveness for small to medium sized intra oral defects 2–4 cm2 [16].

Objectives:

Our study retrospectively evaluates patients reconstructed with either Buccal Fat Pad or Nasolabial Flap or platysma myocutaneous flap for OSMF defects in terms of post-operative functional outcomes.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study was a retrospective analysis of patient records obtained from the medical records directory of the Institute. Screening of records was done from January 2014-December 2021. Initially records were obtained of all patients who presented to the OPD of Faculty of Dental Sciences Banaras Hindu University and were diagnosed with OSMF. The study is in accordance with the STROBE guidelines [17].

Participants

After initial screening of the records by two authors RNB and AKS finally the second level screening was done based on the below mentioned parameters for inclusion in the study.

Mouth Opening < 20 mm

Clinically and histologically diagnosed cases of OSMF

Surgically treated OSMF cases.

Reconstruction with either buccal fat pad or nasolabial flap or platysma flap.

Minimum 1 year follow up.

Adequate data on post operative outcomes.

Patients with previous history of surgery, other known causes of trismus, biopsy showing malignant changes and medically compromised patients were excluded from the study.

Treatment

Patients diagnosed with OSMF Grade III and IV was taken into consideration.

Patient records thus obtained was divided into three groups; Group A (buccal fat pad), Group B (nasolabial flap) and Group C (platysma flap). The management of OSMF cases in our Institute follows a standard protocol

Intubation with Fibreoptic bronchoscopy/ blind nasal intubation.

Excision of vertical fibrotic bands extending from the retrocommisure area to the soft palate avoiding injury to the Stenson’s duct.

Extraction of all third molars.

Recording of maximum interincisal distance. If this is < 35 mm then B/L coronoidotomy.

Buccal fat pad group (Group A): The buccal fat was harvested through the postero–superior margin of the defect with the help of blunt dissection around the capsule of the fat. On an average 3–5 cm of length and 4–6 cm of width of the fat pad was obtained upon dissection. The fat pad was apposed to the oral mucosa with the help of horizontal mattress 3–0 monocryl sutures.

Nasolabial Flap (Group B): An elliptical marking of approximately 1.5–2.5 cm was centered on the nasolabial groove. In our cases only inferiorly based flaps were used. The width to length ratio was 1:3. The tip of the flap was positioned 15mm distal to the medial canthus and the tapering was no more than 35°. The dissection of the flap was done in the supramuscular plane. The flap was transferred to the oral cavity through a transbuccal tunnel and the flap was sutured to the surrounding mucosa with 3–0 monocryl horizontal mattress sutures. After 3 weeks the flap was divided and the tunnel was closed.

Platysma myocutaneous flap (Group C): Superiorly based platysma flap was used for our cases. Two flaps were marked on either side of the midline with the neck hyperextended below the inferior border of the mandible. The superior incision was made and dissection was done in the supra platysmal layer. The inferior incision was made in a similar fashion. The platysma muscle was incised 1 cm inferior to the inferior edge of the skin paddle and a sub platysmal layer was developed upto the inferior border of the mandible. Incisions were then given 1 cm apart from the skin paddle in all directions and the flap was fully mobilized. The flap was insetted into the oral cavity through a subplatysmal tunnel and sutured with the help of 3–0 monocryl horizontal mattress sutures.

Post operatively all patients received a soft temporomandibular joint trainer to avoid injury to the flaps. Nasogastric feeding tubes were placed in all patients for 7 days. Post operative physiotherapy was started on the third post operative day initially with wooden spatulas three to four times daily. Later Histers jaw exerciser was used once daily from the 5th post operative day along with mouth opening exercises with wooden spatulas. All patients underwent aggressive physiotherapy for a period of 1 year.

Evaluation and Outcome

The predictor variable in our study was the three different reconstructive options rendered; buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap and platysma flap for OSMF defect reconstruction. The primary outcome variable was maximal mouth opening and inter-commissural distance measured for a period of 1 year. The secondary outcome variable was post operative complications. Patients were followed for a minimum period of 1 year.

Statistical Analysis

Data was coded and summarized using SPSS version 23.0 for windows. Data was checked for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Shapiro–Wilk test. For non normal data Kruskal Wallis test was used to test the mean difference between three groups. Mann–Whitney test was used for intergroup comparisons. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate the mean difference in outcomes at each follow up interval. A p value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant at 95% confidence interval.

Results

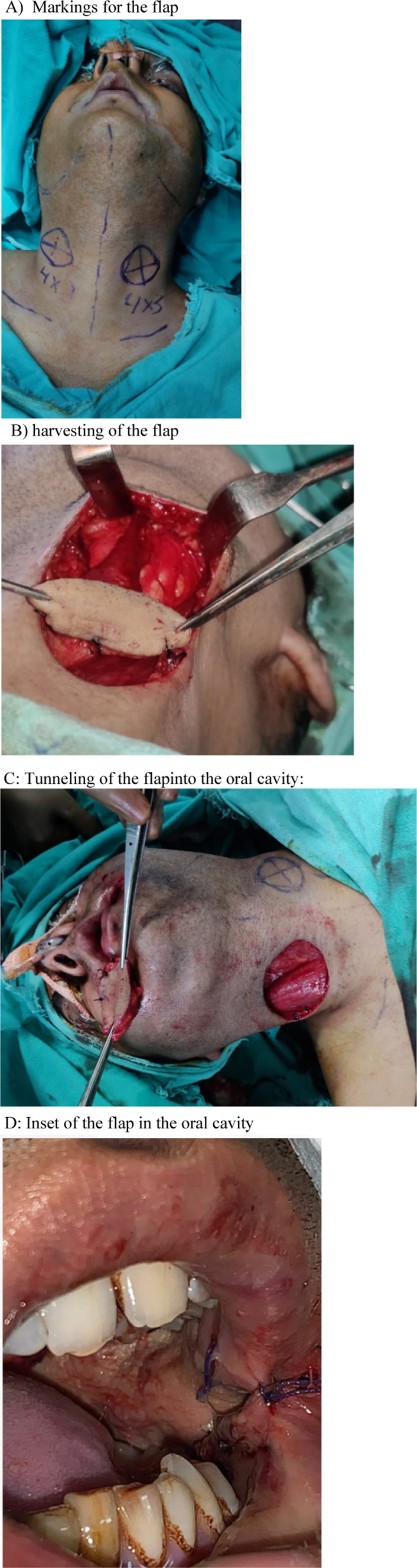

A total of 152 patients were selected based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patient records were divided into three groups based on the predictor variable; Group A (buccal fat pad, n = 65) (Fig. 1), Group B (nasolabial flap, n = 49) (Fig. 2) and Group C (platysma myocutaneous flap, n = 38) (Fig. 3A–D). The Male:Female ratio was 1:0.52. The minimum follow up period was 1 year and the median period was 20 months (12–48 months). The mean age of the patients in our study was 48.7 ± 4.57 years. Results of the normality test are displayed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Epithelization of buccal fat pad

Fig. 2.

Nasolabial flap

Fig. 3.

Group C (platysma myocutaneous flap). A Markings for the flap. B Harvesting of the flap. C Tunneling of the flap into the oral cavity. D Inset of the flap in the oral cavity

Table 1.

Test for normality

| Tests of normality | Group | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | Shapiro–Wilk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig | Statistic | df | Sig | ||

| Pre Op (M/O) | Group A | 0.297 | 65 | 0 | 0.812 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.376 | 49 | 0 | 0.629 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.252 | 38 | 0 | 0.787 | 38 | 0 | |

| Post OP (M/O) | Group A | 0.242 | 65 | 0 | 0.85 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.271 | 49 | 0 | 0.814 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.241 | 38 | 0 | 0.776 | 38 | 0 | |

| 6 months (M/O) | Group A | 0.312 | 65 | 0 | 0.691 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.371 | 49 | 0 | 0.764 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.518 | 38 | 0 | 0.4 | 38 | 0 | |

| 12 months (M/O) | Group A | 0.265 | 65 | 0 | 0.805 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.536 | 49 | 0 | 0.127 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.304 | 38 | 0 | 0.776 | 38 | 0 | |

| Commisure pre | Group A | 0.438 | 65 | 0 | 0.58 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.449 | 49 | 0 | 0.566 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.446 | 38 | 0 | 0.57 | 38 | 0 | |

| Commisure post | Group A | 0.49 | 65 | 0 | 0.49 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.381 | 49 | 0 | 0.739 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.352 | 38 | 0 | 0.636 | 38 | 0 | |

| Commisure 6 months | Group A | 0.453 | 65 | 0 | 0.56 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.355 | 49 | 0 | 0.635 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.338 | 38 | 0 | 0.637 | 38 | 0 | |

| Commisure 12 months | Group A | 0.367 | 65 | 0 | 0.632 | 65 | 0 |

| Group B | 0.397 | 49 | 0 | 0.618 | 49 | 0 | |

| Group C | 0.393 | 38 | 0 | 0.621 | 38 | 0 | |

Maximal Mouth Opening

The mean pre operative mouth opening in Groups A, B and C were 13.94 ± 2.97 mm, 13.86 ± 1.0 mm and 13.66 ± 3.42 mm respectively (p value = 0.42). There was no statistical significant difference in MMO among the groups in the immediate post operative period (p value = 0.705). At the end of 6 months there was a statistically better MMO in group C (40.66 ± 1.71) compared to group A (39.71 ± 2.82). However the difference was insignificant between groups A and B and groups B and C. At the end of 12 months the difference in MMO between group A and B was insignificant (p value = 0.496). The platysma group had significantly better MMO compared to both Groups A and B (p value < 0.001). All three groups showed statistical significant reduction in mouth opening from immediate post operative period to 12 months (p value < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of mouth opening

| M/O | Group A (buccal fat pad) n = 65 | Group B (nasolabial flap) n = 49 | Group C (platysma flap) n = 38 | p value | A versus B | A versus c | B versus c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre Op | 13.94 ± 2.97 | 13.86 ± 1.0 | 13.66 ± 3.42 | 0.42 | 0.104 | 0.394 | 0.685 |

| Post OP | 50.89 ± 2.44 | 50.65 ± 3.02 | 51.16 ± 3.02 | 0.705 | 0.665 | 0.617 | 0.400 |

| 6 months | 39.71 ± 2.82 | 40.14 ± 1.04 | 40.66 ± 1.71 | 0.043 | 0.145 | 0.015 | 0.234 |

| 12 months | 36.69 ± 3.41 | 37.94 ± 0.43 | 39.84 ± 1.65 | < 0.001 | 0.496 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Post op versus pre op | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 6 months versus post op | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 12 months versus 6 months | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Inter Commissural Distance

The mean inter commissural distance pre operatively was 51.54 ± 2.33 mm in group A, 51.43 ± 2.28 mm in group B and 51.45 ± 2.3 mm in Group C (p value 0.963). There was a statistical significant decrease in inter commissural distance in all three groups from immediate post operative period to 12 months (p value < 0.001). Intergroup comparisons at 6 months follow up showed statistically higher intercommisural distance in group C compared to both groups B and A. Group B also had better intercommisural distance compared to group A at 6 months. At 12 months follow up group C had statistically better inter commissural distance compared to both groups A and B, group B had better inter commissural distance compared to group A (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of inter-commissural distance

| Inter-commisure distance | Group A (buccal fat pad) | Group B (nasolabial flap) | Group C (platysma flap) | p value | A versus B | A versus C | B versus C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre Op | 51.54 ± 2.33 | 51.43 ± 2.28 | 51.45 ± 2.3 | 0.963 | 0.800 | 0.847 | 0.970 |

| Post OP | 64 ± 2.02 | 63.69 ± 1.88 | 63.95 ± 1.01 | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.023 | 0.607 |

| 6 months | 56.38 ± 2.26 | 60.94 ± 1.01 | 62.5 ± 2.53 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.021 |

| 12 months | 54.11 ± 1 | 56.84 ± 1.48 | 59.21 ± 0.99 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| p value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Post op versus pre op | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 6 months versus post op | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 12 months versus 6 months | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Healing and Complications

The mean time for epithelization in buccal fat group was 36. 50 ± 3.13 days. The mean time taken for mucosalization in nasolabial group was 184.4 ± 3.76 days and 186.97 ± 5.87 days in platysma group. Partial flap necrosis occurred in three patients; 2 in group B and 1 in group A. TMJ subluxation was present in two patients of Group C. None of the patients had any post operative infections. Distortion of the commisure was present in two patients of group B. Patients in group B experienced scarring in the nasolabial area but all healed without any hypertrophic scarring.

Discussion

Key Results

After 1 year follow up patients in platysma group had significantly better maximal mouth opening (39.84 ± 1.65 mm) compared to both buccal fat pad (36.69 ± 3.41 mm) and nasolabial groups (37.94 ± 0.43 mm). The difference in MMO was insignificant between buccal fat and nasolabial groups after 1 year follow up. Inter commisural distance was significantly better in patients reconstructed with platysma flap (59.21 ± 0.99 mm) compared to both buccal fat pad (54.11 ± 1 mm) and nasolabial flap (56.84 ± 1.48 mm). Patients reconstructed with nasolabial flap showed significantly higher commissural distance at 12 months compared to buccal fat pad. There was a statistical significant reduction in inter commissural distance and mouth opening in all three groups from immediate post operative period to 12 months.

Limitations

Studies with long term follow up are necessary to evaluate the outcome and also quality of life assessment.

Cosmetic assessment ideally should have been done with proper scar assessment scale and with at least two observers. The retrospective nature of our study suffered this flaw.

Since the groups are not randomized there might be selection and allocation bias in the study.

Interpretation

Moderately advanced (stage III) and advanced (stage IV a & b) OSMF requires surgical intervention for management [18]. As previously discussed a number of options are available for reconstruction of the oral cavity defect. In our study we retrospectively compared buccal fat pad, nasolabial flap and platysma flap for reconstruction of the buccal mucosal defects.

The buccal fat anatomically occupies the masticatory space with its main body and 4 extensions; buccal, pterygoid, pterygopalatine and temporal. The BFP has three lobes; anterior, intermediate and posterior. The BFP has a mean thickness of 6 mm and can cover a surface of up to 10 cm2. The BFP is ideal for the closure of small defects within the oral cavity (4 × 4 cm) and is relatively contraindicated for defects > 5 cm [19]. The nasolabial flap can be harvested either as a random pattern flap or an axial flap. The inferiorly based axial flap is based on the facial artery and the superiorly based flap is based on the angular artery. Various variants of the flap can be harvested; defatted, ordinary, musculocutaneous, full thickness and composite nasolabial flap [20] The platysma myocutaneous flap can be used to cover intra oral defects ranging from 50 to 75 cm2. The advantages include good color match, minimal donor site morbidity and good thickness [21]. The recent study by Anehosur et al. comparing buccal fat pad and nasolabial flap showed significant improvement in mouth opening and inter commisural distance in the nasolabial group compared to buccal fat pad group[22]. Buccal fat pad has a limitation in covering the anterior most portion of the oral cavity; the retrocommisure area. This anterior portion often left raw which heals by secondary intention and leads to fibrosis. Aggressive physiotherapy has shown to counteract the fibrosis associated with buccal fat pad [11]. Agrawal et al. [2, 13, 24]. Pardeshi et al. [25] in their study favored recommended the use of buccal fat pad for moderate trismus (> 15 mm mouth opening) and nasolabial flap for severe trismus (< 15 mm) owing to the bulk provided by the latter. Ambereen et al. [26] recommended reconstructing OSMF defects both with buccal fat pad and nasolabial flap; the buccal fat was used for reconstructing the posterior most portion of the oral cavity and nasolabial flap was used for reconstructing the anterior portion. Tiwari et al. [27] in their meta analysis concluded that buccal fat pad was favored by majority of the authors. The major limitation was the anterior reach of the flap which could be controlled with aggressive physiotherapy. Nasolabial flap can be used for severe trismus however it leaves a posterior dead space which could be counteracted with a sandwich technique. Nasolabial flaps also suffer certain complications like intra oral hair growth, fish mouth deformity and extra oral scars. Platysma myocutaneous flap would provide the necessary bulk required for reconstruction and would also reduce the donor site morbidity associated with nasolabial flap.

Conclusion

Platysma flap lead to significantly better maximal mouth opening compared to both nasolabial and buccal fat pad. Both buccal fat pad and nasolabial lead to comparable mouth opening. Inter commissural distance is maximum with platysma flap followed by nasolabial flap and buccal fat pad. There was a significant decrease in both mouth opening and commissural distance from immediate post operative period to 1 year.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ Contribution

All authors have made significant contribution in preparing the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive any form of funding.

Data Availability

Can be shared on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Obtained (No. Dean/2020/EC/2138).

Consent for Publication

All authors give full consent to publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hande AH, Chaudhary MS, Gawande MN, Gadbail AR, Zade PR, Bajaj S, Patil SK, Tekade S. Oral submucous fibrosis: an enigmatic morpho-insight. J Cancer Res Ther. 2019;15(3):463–469. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_522_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shih YH, Wang TH, Shieh TM, Tseng YH. Oral submucous fibrosis: a review on etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(12):2940. doi: 10.3390/ijms20122940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng Q, Li H, Chen J, Wang Y, Tang Z. Oral submucous fibrosis in Asian countries. J Oral Pathol Med. 2020;49(4):294–304. doi: 10.1111/jop.12924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chitguppi C, Brar T. Paediatric oral submucous fibrosis—the neglected pre-malignancy of childhood. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;97:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan PA, Arakeri G. Oral submucous fibrosis—an increasing global healthcare problem. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46(6):405. doi: 10.1111/jop.12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray JG, Chatterjee R, Chaudhuri K. Oral submucous fibrosis: a global challenge. Rising incidence, risk factors, management, and research priorities. Periodontol. 2019;200080(1):200–212. doi: 10.1111/prd.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pathak H, Mohanty S, Urs AB, Dabas J. Treatment of oral mucosal lesions by scalpel excision and platelet-rich fibrin membrane grafting: a review of 26 sites. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(9):1865–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokal NJ, Raje RS, Ranade SV, Prasad JS, Thatte RL. Release of oral submucous fibrosis and reconstruction using superficial temporal fascia flap and split skin graft—a new technique. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58(8):1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bande CR, Datarkar A, Khare N. Extended nasolabial flap compared with the platysma myocutaneous muscle flap for reconstruction of intraoral defects after release of oral submucous fibrosis: a comparative study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan RC, Wei FC, Tsao CK, Kao HK, Chang YM, Tsai CY, Chen WH. Free flap reconstruction after surgical release of oral submucous fibrosis: long-term maintenance and its clinical implications. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(3):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rai A, Datarkar A, Rai M. Is buccal fat pad a better option than nasolabial flap for reconstruction of intraoral defects after surgical release of fibrous bands in patients with oral submucous fibrosis? A pilot study: a protocol for the management of oral submucous fibrosis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42(5):e111–e116. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patil SB, Durairaj D, Suresh Kumar G, Karthikeyan D, Pradeep D. Comparison of extended nasolabial flap versus buccal fat pad graft in the surgical management of oral submucous fibrosis: a prospective pilot study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;16(3):312–321. doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0975-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agrawal D, Pathak R, Newaskar V, Idrees F, Waskle R. A comparative clinical evaluation of the buccal fat pad and extended nasolabial flap in the reconstruction of the surgical defect in oral submucous fibrosis patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;76(3):676.e1–676.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhry K, Bali R, Patnana AK, Bindra S, Jain G, Sharma PP. Impact of oral submucous fibrosis on quality of life: a cross-sectional study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2019;18(2):260–265. doi: 10.1007/s12663-018-1114-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaudhry K, Bali R, Patnana AK, Chattopadhyay C, Sharma PP, Khatana S. Impact of oral submucous fibrosis on quality of life: a multifactorial assessment. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2020;19(2):251–256. doi: 10.1007/s12663-019-01190-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bande C, Joshi A, Gawande M, Tiwari M, Rode V. Utility of superiorly based platysma myocutaneous flap for reconstruction of intraoral surgical defects: our experience. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;22(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10006-017-0665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna JN, Andrade NN. Oral submucous fibrosis: a new concept in surgical management. Report of 100 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;24(6):433–439. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chouikh F, Dierks EJ. The buccal fat pad flap. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 2021;33(2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahpeyma A, Khajehahmadi S. The place of nasolabial flap in orofacial reconstruction: a review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2016;12:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baur DA, Williams J, Alakaily X. The platysma myocutaneous flap. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 2014;26(3):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anehosur V, Singh PK, Dikhit PS, Vadera H. Clinical evaluation of buccal fat pad and nasolabial flap for oral submucous fibrosis intraoral defects. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2021;14(3):196–200. doi: 10.1177/1943387520962264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kavarana NM, Bhathena HM. Surgery for severe trismus in submucous fibrosis. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40(4):407–409. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(88)90020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borle RM, Borle SR. Management of oral submucous fibrosis : a conservative approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49(8):788–791. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pardeshi P, Padhye M, Mandlik G, Mehta P, Vij K, Madiwale G, et al. Clinical evaluation of nasolabial flap & buccal fat pad graft for surgical treatment of oral submucous fibrosis—a randomized clinical trial on 50 patients in Indian population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(Supp 1):e121–e122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.08.733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambereen A, Lal B, Agarwal B, Yadav R, Roychoudhury A. Sandwich technique for the surgical management of oral submucous fibrosis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57(9):944–945.2. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiwari P, Bera RN, Chauhan N. What is the optimal reconstructive option for oral submucous fibrosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of buccal pad of fat versus conventional nasolabial and extended nasolabial flap versus platysma myocutaneous flap. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2020;19(4):490–497. doi: 10.1007/s12663-020-01373-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Can be shared on request.