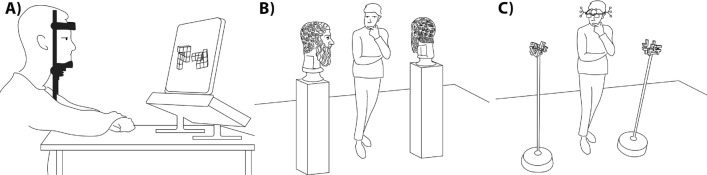

Figure 1.

Our experiment as it evolved, beginning with Sheppard and Metzler’s inspiration, the reality of visuospatial problem-solving “in the wild”, and our actual setup. (A) The study of human vision often involves a two-dimensional probe, i.e., visual function. As illustrated here, the subject sits at a desk with head stabilized in a forehead and chin mount while performing an experiment involving images on a screen. (B) Real-world visuospatial problem-solving, i.e. functional vision, however, is distinctively different. Here we show someone in a sculpture gallery wondering if these two marble heads are the same. Humans do not passively receive stimuli; rather, they choose what to look at and how. We move our head and body in a three-dimensional world and view objects from directions and positions that are most suited to our viewing purpose. It should be clear that answering our sculpture query here might require more than one glance. It is we who decide what to look at, not an experimenter. (C) Our experimental setup is as shown. A subject wears a special, wireless headset and is shown two objects mounted on posts at certain 3D orientations. The subject is asked to determine, without touching, if the two objects are the same (in all aspects) or different and is completely free and untethered to move anywhere they choose. Gaze and view are precisely recorded (see Methods and Materials).