Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to determine the factors associated with the concentrations of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and its major metabolite, desethylhydroxychloroquine (DHCQ), in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods

Patients with SLE taking oral HCQ for at least 3 months were recruited from the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital. Clinical characteristics and laboratory values were examined. The concentrations of HCQ and DHCQ were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography, and the effects of various factors on the concentrations were investigated.

Results

A total of 272 patients were included in this study. The average concentration of HCQ was 690.90 ng/ml and the average concentration of DHCQ was 431.84 ng/ml. Multivariate analysis indicated that gender (P = 0.015), age (year) (P < 0.001), weight (kg) (P = 0.013), duration of HCQ use (month) (P < 0.001), systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLEDAI) (P < 0.001), platelet count (× 109/l) (P < 0.001), immunoglobulin G levels (g/l) (P = 0.014) were associated with low HCQ concentrations. Gender (P = 0.006), duration of HCQ use (month) (P < 0.001), SLEDAI (P = 0.007), and platelet count (× 109/l) (P < 0.001) were associated with low DHCQ concentrations.

Conclusions

Patients with SLE require long-term administration of HCQ, but blood levels vary widely between individuals. Studying the factors influencing the blood HCQ and DHCQ concentrations and optimizing the dose according to individual characteristics might help to improve the efficacy of HCQ.

Trial Registration

ChiCTR2300070628.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-023-00598-2.

Keywords: Hydroxychloroquine, Systemic lupus erythematosus, Blood concentration, Analysis of influencing factors

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) are complex, and its blood concentrations vary greatly between treated patients, leading to differences in efficacy. |

| A low blood concentration of HCQ is a marker and predictor of disease progression in patients with SLE. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Gender, age, weight, duration of HCQ use, systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLEDAI), platelet count, and immunoglobulin G levels might explain the differences in concentration. |

| Combining blood HCQ or desethylhydroxychloroquine (DHCQ) concentrations with individual patient characteristics to optimize dosage might help improve treatment outcomes in Chinese patients with SLE. |

Introduction

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), a 4-aminoquinoline antimalarial agent, is the cornerstone of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) medical therapy [1, 2]. Long-term use of HCQ in patients with SLE can reduce disease activity, lower the risk of organ damage and thrombosis, improve blood glucose and lipid profiles, and increase patient survival [3].

The pharmacokinetics of HCQ are complex, and its blood concentrations vary greatly between treated patients, including healthy volunteers and adherent patients [4], leading to differences in efficacy [5]. Studies have shown a significant correlation between whole blood HCQ levels and clinical outcomes in patients with SLE [1, 6–8]. According to the study by Fasano et al., higher HCQ blood levels have a protective effect against disease attacks [9]. Poor compliance, as indicated by HCQ concentrations below 100 ng/ml, was found in 29% of patients with SLE [10] and can predict adverse outcomes [11]. Additionally, a low blood concentration of HCQ is a marker and predictor of disease progression in patients with SLE, with a negative predictive value of 96% at a whole blood HCQ concentration of 1000 ng/ml [12]. Therefore, investigating the factors that influence HCQ blood concentration is crucial for assessing patient compliance, evaluating treatment efficacy, and adjusting treatment plans.

HCQ is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes to desethylhydroxychloroquine (DHCQ) and desethylchloroquine (DCQ), with DHCQ being the main active metabolite [13, 14]. Studies have suggested a correlation between blood DHCQ concentrations and HCQ efficacy [15]. So far, there have been few studies on the relationship between HCQ concentrations and clinical factors in patients with SLE, and few studies involving metabolites [16]. In this study, we analyzed various clinical factors to identify factors contributing to the wide inter-individual variation in blood HCQ and DHCQ concentrations, with the aim of guiding individual HCQ dose adjustment.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (Approval Number: 2021-643-02). The study population was patients hospitalized in the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital from January 2020 to December 2022. Inclusion criteria were patients who met the 1997 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria [17], had been treated with oral HCQ for at least 3 months at a daily dose of 400 mg, and consented to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were pregnant and lactating women, patients with incomplete data, patients at risk and need to use high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 1 mg·kg−1·d−1 prednisone or equivalent doses of other hormones), and patients with poor adherence.

Data Collection

The collected data included patient basic characteristics (gender, age, weight, etc.), information on combination medication, and laboratory test results such as white blood cell (WBC), platelet, red blood cell (RBC), neutrophil percent (NEUT%), lymphocyte percent (LY%), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin, creatinine (CR), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), complement C3, complement C4, immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin A (IgA), immunoglobulin M (IgM), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Measurement of HCQ, DHCQ Concentrations

Fasting venous blood was collected from patients early in the morning. Whole blood HCQ and DHCQ concentrations were quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography. Patients with HCQ concentration < 100 ng/ml were excluded for non-compliant with medication [6, 18, 19]. All measurements were performed at the Precision Medicine Center of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing, China), using a method adapted from a previously published method [20].

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze qualitative data. Independent samples t test was used to compare the means of two independent groups. The association of influencing factors and low HCQ and DHCQ blood concentrations was assessed with binary logistic regression analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics

This study analyzed 272 patients who received a daily dose of 400 mg HCQ, and their characteristics were presented in Table 1. The mean patient age was 40.63 ± 14.60 years, with 88.24% being female, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 22.67 ± 4.26 kg/m2. 86.40% of patients were taking glucocorticoids and 49.63% patients were taking immunosuppressants. The mean HCQ concentration was 690.90 ng/ml and the mean DHCQ concentration was 431.84 ng/ml.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 272 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus

| Category | |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 240 (88.24) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 40.63 (14.60) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 60.07 (13.20) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 22.67 (4.26) |

| Duration, months, mean (SD) | 10.12 (10.47) |

| With glucocorticoids, n (%) | 235 (86.40) |

| With immunosuppressants, n (%) | 135 (49.63) |

| SLEDAI, mean (SD) | 7.92 (3.63) |

| Anti-ds DNA positive, n (%) | 85 (31.25) |

| HCQ concentration, ng/ml, mean (SD) | 690.90 (541.12) |

| DHCQ concentration, ng/ml, mean (SD) | 431.84 (430.53) |

HCQ hydroxychloroquine, DHCQ desethylhydroxychloroquine, BMI body mass index, Duration duration of HCQ use, SLEDAI systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index, Anti-ds DNA anti-double-stranded DNA

Univariate Analysis

Patients were divided into two groups based on the mean blood concentrations of HCQ and DHCQ. Patients with HCQ blood concentrations ≤ the mean (690.90 ng/ml) were classified as the low concentration group (n = 158), and patients with HCQ blood concentrations > the mean (690.90 ng/ml) were classified as the high concentration group (n = 114). For HCQ concentrations, statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in gender (P = 0.039), age (P = 0.041), weight (P = 0.029), duration of HCQ use (P < 0.001), SLEDAI (P < 0.001), platelet count (P < 0.001), RBC count (P = 0.046), complement C3 levels (P < 0.001), complement C4 levels (P < 0.001), and IgG levels (P = 0.021) (Table 2). Patients with DHCQ blood concentrations ≤ the mean (431.84 ng/ml) were categorized as the low concentration group (n = 176) and patients with DHCQ blood concentrations > the mean (431.84 ng/ml) were categorized as the high concentration group (n = 96). Gender (P = 0.013), duration of HCQ use (P < 0.001), SLEDAI (P = 0.003), platelet count (P < 0.001), ALT (P = 0.008), albumin (P = 0.034), BUN (P = 0.010), CR (P = 0.011), eGFR (P = 0.014), CRP (P = 0.026), complement C4 levels (P < 0.001), and IgG levels (P = 0.004) were related to DHCQ concentrations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of univariate analysis of HCQ and DHCQ concentrations

| Category | Total population | HCQ concentration | DHCQ concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 272) | Low (n = 158) | High (n = 114) | P value | Low (n = 176) | High (n = 96) | P value | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.039 | 0.013 | |||||

| Female | 240 (88.24) | 134 (84.81) | 106 (92.98) | 149 (84.66) | 91 (94.79) | ||

| Male | 32 (11.76) | 24 (15.19) | 8 (7.02) | 27 (15.34) | 5 (5.21) | ||

| Age, years, n (%) | 0.041 | 0.055 | |||||

| < 50 | 190 (69.85) | 118 (74.68) | 72 (63.16) | 116 (65.91) | 74 (77.08) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 82 (30.15) | 40 (25.32) | 42 (36.84) | 60 (34.09) | 22 (22.92) | ||

| Weight, kg | 60.07 (13.20) | 61.56 (13.99) | 58.02 (11.77) | 0.029 | 61.08 (13.92) | 58.23 (11.61) | 0.089 |

| BMI, kg/m2, n (%) | 0.995 | 0.306 | |||||

| < 24 kg/m2 | 179 (65.81) | 104 (65.82) | 75 (65.79) | 112 (63.64) | 67 (69.79) | ||

| ≥ 24 kg/m2 | 93 (34.19) | 54 (34.18) | 39 (34.21) | 64 (36.36) | 29 (30.21) | ||

| Duration, n (%) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||

| < 6 months | 151 (55.51) | 102 (64.56) | 49 (42.98) | 113 (64.21) | 38 (39.58) | ||

| 6–12 months | 39 (14.34) | 26 (16.45) | 13 (11.40) | 26 (14.77) | 13 (13.54) | ||

| > 12 months | 82 (30.15) | 30 (18.99) | 52 (45.62) | 37 (21.02) | 45 (46.88) | ||

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 0.593 | 0.983 | |||||

| With | 235 (86.40) | 138 (87.34) | 97 (85.09) | 152 (86.36) | 83 (86.46) | ||

| Without | 37 (13.60) | 20 (12.66) | 17 (14.91) | 24 (13.64) | 13 (13.54) | ||

| Immunosuppressants, n (%) | 0.698 | 0.676 | |||||

| With | 135 (49.63) | 80 (50.63) | 55 (48.25) | 89 (50.57) | 46 (47.92) | ||

| Without | 137 (50.37) | 78 (49.37) | 59 (51.75) | 87 (49.43) | 50 (52.08) | ||

| SLEDAI, n (%) | < 0.001 | 0.003 | |||||

| ≤ 4 | 209 (76.84) | 103 (65.19) | 106 (92.98) | 124 (70.45) | 85 (88.54) | ||

| 5–9 | 61 (22.43) | 53 (33.54) | 8 (7.02) | 50 (28.41) | 11 (11.46) | ||

| 10–14 | 2 (0.73) | 2 (1.27) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.14) | 0 (0) | ||

| Anti-ds DNA, n (%) | 0.079 | 0.784 | |||||

| Positive | 85 (31.25) | 56 (35.44) | 29 (25.44) | 56 (31.82) | 29 (30.21) | ||

| Negative | 187 (68.75) | 102 (64.56) | 85 (74.56) | 120 (68.18) | 67 (69.79) | ||

| WBC, × 109/l | 6.41 (3.11) | 6.15 (2.98) | 6.77 (3.26) | 0.104 | 6.25 (3.22) | 6.71 (2.91) | 0.246 |

| Platelet, × 109/l | 194.17 (96.69) | 175.70 (87.81) | 219.76 (102.81) | < 0.001 | 172.68 (91.21) | 233.56 (94.44) | < 0.001 |

| RBC, × 1012/l | 3.59 (0.76) | 3.51 (0.74) | 3.70 (0.78) | 0.046 | 3.59 (0.75) | 3.59 (0.79) | 0.979 |

| NEUT% | 69.19 (12.88) | 69.74 (13.58) | 68.43 (11.86) | 0.412 | 69.22 (12.68) | 69.12 (13.31) | 0.951 |

| LY% | 22.43 (11.03) | 21.93 (11.52) | 23.13 (10.33) | 0.377 | 22.21 (10.54) | 22.82 (11.93) | 0.664 |

| ALT, U/l | 25.02 (36.89) | 24.52 (21.09) | 25.72 (51.43) | 0.791 | 28.40 (44.89) | 18.83 (10.55) | 0.008 |

| AST, U/l | 24.02 (31.06) | 21.87 (14.02) | 26.99 (45.00) | 0.242 | 25.69 (36.35) | 20.94 (17.41) | 0.229 |

| Albumin, g/l | 34.56 (5.86) | 34.55 (5.85) | 34.58 (5.89) | 0.971 | 35.12 (5.66) | 33.54 (6.09) | 0.034 |

| TC, mmol/l | 4.52 (1.41) | 4.47 (1.12) | 4.59 (1.74) | 0.515 | 4.40 (1.08) | 4.74 (1.86) | 0.106 |

| TG, mmol/l | 1.88 (1.16) | 1.88 (1.11) | 1.89 (1.22) | 0.942 | 1.81 (1.09) | 2.01 (1.27) | 0.195 |

| HDL-C, mmol/l | 1.24 (0.39) | 1.20 (0.40) | 1.29 (0.37) | 0.055 | 1.22 (0.39) | 1.26 (0.39) | 0.432 |

| LDL-C, mmol/l | 2.49 (1.10) | 2.45 (0.92) | 2.54 (1.31) | 0.509 | 2.39 (0.88) | 2.65 (1.40) | 0.101 |

| BUN, mmol/l | 7.12 (4.64) | 6.81 (3.74) | 7.55 (5.64) | 0.222 | 6.50 (3.40) | 8.26 (6.16) | 0.010 |

| CR, umol/l | 74.97 (86.69) | 66.89 (47.93) | 86.17 (120.89) | 0.109 | 62.26 (39.08) | 98.26 (133.33) | 0.011 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 122.99 (50.85) | 126.34 (49.48) | 118.34 (52.55) | 0.201 | 128.55 (48.96) | 112.80 (52.89) | 0.014 |

| CRP, mg/l | 7.32 (10.65) | 6.82 (10.68) | 8.02 (10.61) | 0.359 | 6.21 (9.90) | 9.36 (11.68) | 0.026 |

| Complement C3, g/l | 0.91 (0.30) | 0.85 (0.29) | 1.00 (0.27) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.31) | 0.94 (0.26) | 0.271 |

| Complement C4, g/l | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.08) | 0.20 (0.08) | < 0.001 | 0.15 (0.08) | 0.20 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| IgG, g/l | 13.19 (6.36) | 13.95 (5.92) | 12.14 (6.81) | 0.021 | 14.01 (5.87) | 11.70 (6.95) | 0.004 |

| IgA, g/l | 2.64 (1.57) | 2.75 (1.73) | 2.49 (1.31) | 0.178 | 2.76 (1.71) | 2.43 (1.26) | 0.106 |

| IgM, g/l | 1.38 (1.48) | 1.47 (1.65) | 1.26 (1.21) | 0.239 | 1.49 (1.67) | 1.20 (1.05) | 0.128 |

| ESR, mm/h | 27.89 (22.66) | 28.96 (22.48) | 26.40 (22.92) | 0.360 | 28.30 (22.54) | 27.14 (22.99) | 0.687 |

Values are mean with SD in parentheses or number of patients with percentage in parentheses. Significant P values are in bold

HCQ hydroxychloroquine, DHCQ desethylhydroxychloroquine, BMI body mass index; Duration duration of HCQ use, SLEDAI systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index, Anti-ds DNA anti-double-stranded DNA, WBC white blood cell, RBC red blood cell, NEUT% neutrophil percent, LY% lymphocyte percent, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate transaminase, TC total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, BUN blood urea nitrogen, CR creatinine, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, CRP C-reactive protein, IgG immunoglobulin G, IgA immunoglobulin A, IgM immunoglobulin M, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Multivariate Analysis

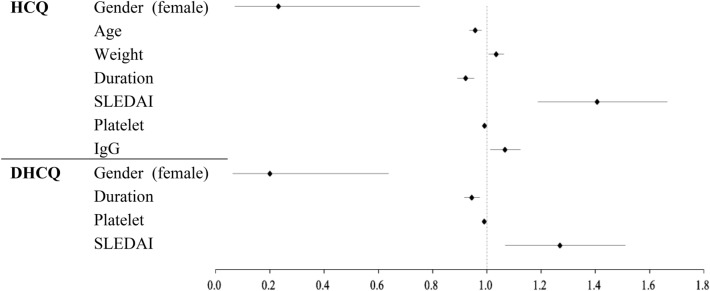

To determine factors independently associated with low blood HCQ and DHCQ concentrations, binary logistic regression was used to examine factors that showed significant differences (P < 0.05) in univariate analysis. Table 3 and Fig. 1 shows the data analysis results. Gender (OR = 0.23; P = 0.015; 95% CI = 0.07–0.75), age (year) (OR = 0.96; P < 0.001; 95% CI = 0.94–0.98), weight (kg) (OR = 1.04; P = 0.013; 95% CI = 1.01–1.06), duration of HCQ use (month) (OR = 0.92; P < 0.001; 95% CI = 0.89–0.95), SLEDAI (OR = 1.41; P < 0.001; 95% CI = 1.19–1.67), platelet count (× 109/l) (OR = 0.99; P < 0.001; 95% CI = 0.99–1.00), and IgG levels (g/l) (OR = 1.07; P = 0.014; 95% CI = 1.01–1.12) were associated with low HCQ concentrations. Gender (OR = 0.20; P = 0.006; 95% CI = 0.06–0.64), duration of HCQ use (month) (OR = 0.95; P < 0.001; 95% CI = 0.92–0.97), SLEDAI (OR = 1.27, P = 0.007, 95% CI = 1.07–1.51), and platelet count (× 109/l) (OR = 0.99; P < 0.001; 95% CI = 0.99–1.00) were associated with low DHCQ concentrations. In addition, we performed linear regression (Supplementary Table 1), the results also confirmed the influence of the above factors.

Table 3.

Factors associated with low HCQ and DHCQ concentrations

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCQ | |||

| Gender (female) | 0.23 | 0.07–0.75 | 0.015 |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.94–0.98 | < 0.001 |

| Weight | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.013 |

| Duration | 0.92 | 0.89–0.95 | < 0.001 |

| SLEDAI | 1.41 | 1.19–1.67 | < 0.001 |

| Platelet | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | < 0.001 |

| RBC | 1.15 | 0.71 -1.84 | 0.575 |

| Complement C3 | 0.56 | 0.11–2.74 | 0.472 |

| Complement C4 | 0.07 | 0.00–9.55 | 0.287 |

| IgG | 1.07 | 1.01–1.12 | 0.014 |

| DHCQ | |||

| Gender (female) | 0.20 | 0.06–0.64 | 0.006 |

| Duration | 0.95 | 0.92–0.97 | < 0.001 |

| SLEDAI | 1.27 | 1.07–1.51 | 0.007 |

| Platelet | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | < 0.001 |

| ALT | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | 0.146 |

| Albumin | 1.05 | 0.98–1.12 | 0.187 |

| BUN | 1.01 | 0.89–1.15 | 0.857 |

| CR | 0.99 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.158 |

| eGFR | 1.00 | 0.99–1.00 | 0.543 |

| CRP | 0.98 | 0.95–1.00 | 0.072 |

| Complement C4 | 0.04 | 0.00–2.35 | 0.122 |

| IgG | 1.02 | 0.97–1.08 | 0.418 |

Significant P values are in bold

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, HCQ hydroxychloroquine, DHCQ desethylhydroxychloroquine, Duration duration of HCQ use, SLEDAI systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index, RBC red blood cell, IgG immunoglobulin G, ALT alanine transaminase, BUN blood urea nitrogen, CR creatinine, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, CRP C-reactive protein

Fig. 1.

Binary logistic regression model results. HCQ hydroxychloroquine, DHCQ desethylhydroxychloroquine, Duration duration of HCQ use, SLEDAI systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index, IgG immunoglobulin G

Discussion

HCQ is commonly used as a first-line treatment for SLE and other rheumatic diseases. Its pharmacokinetic profile is complex, and blood levels vary widely between individuals. Blood concentrations of HCQ have been shown to correlate with clinical efficacy and can indicate patient compliance [6–8, 10]. In this study, we investigated potential factors that may affect HCQ and DHCQ concentrations by comparing patient characteristics between high and low concentration groups. Binary logistic regression analysis revealed that gender, age, weight, duration of HCQ use, SLEDAI, platelet count, and IgG levels were influencing factors for low blood HCQ concentrations. Duration of HCQ use, platelet count, SLEDAI and gender were influencing factors for low blood DHCQ concentrations.

Although several studies have investigated the relationship between HCQ concentrations and clinical factors in patients with rheumatic diseases, most have not examined DHCQ concentrations [5, 16, 21]. Our study was one of the few in which both HCQ and DHCQ concentrations were measured in the Chinese population with SLE. In addition, to avoid the confounding effects of dose, we only included patients taking a daily dose of 400 mg HCQ.

We found higher concentrations of HCQ and DHCQ in female patients. This gender difference in drug concentration may be attributed to differences in CYP-mediated metabolism, the influence of sex hormones on absorption, and the difference of fat percentage in body composition [22]. Estrogen has been shown to downregulate CYP3A4 expression [23].

HCQ has a large apparent volume of distribution (over 2000 l) due to poor plasma protein binding (about 50%) and high tissue binding (including blood cells) [7, 24]. Our study results were consistent with this finding. We observed higher HCQ blood levels in patients with low body weight, and the expected delay in reaching steady-state concentrations (3–4 months) due to the accumulation of HCQ in tissues may explain the positive correlation between HCQ and DHCQ concentrations and duration of HCQ use [25, 26].

HCQ is primarily metabolized by CYP450 enzymes in the liver to a variety of active metabolites, with approximately one-quarter of the prototype being cleared through the kidneys [27–29]. A previous study that included 111 patients with SLE receiving long-term HCQ therapy observed higher HCQ concentrations in patients with renal insufficiency [5]. In our study, we did not find an association between renal function and HCQ or DHCQ concentrations, as it was challenging to recruit patients with SLE on long-term HCQ due to their clinical severity and use of higher doses of immunosuppressive drugs and glucocorticoids. However, we did observe higher HCQ blood levels in older patients, which may be due to decreased renal function.

The SLEDAI score, which measures lupus disease activity, is strongly correlated with HCQ concentration [21]. The effective concentration threshold of HCQ in clinical practice is still controversial [30]. Costedoat-Chalumeau et al. [12] recommended a whole-blood HCQ target concentration of 1000 ng/ml for patients with SLE. In our study, only 19.49% of patients (n = 53) achieved this target. For the goal of 750 ng/ml in a meta-analysis by Garg et al. [30], 37.5% (n = 102) of patients achieved it. Our study showed that higher HCQ concentrations were associated with lower SLEDAI in the population with a mean HCQ concentration of 690.90 ng/ml. Thus, we found that higher HCQ concentrations were beneficial in reducing disease activity even in the range below previously recommended concentration. In addition, higher DHCQ concentrations were also found to be beneficial in reducing disease activity.

Our study also found a significant association between low platelet counts and low HCQ and DHCQ blood concentrations. We believe this finding may be related to the fact that we measured the whole blood rather than serum concentration. HCQ has been shown to bind to platelets and other blood cells, which can result in its retention in the blood and limit its distribution to eliminated organs [31]. This may explain why low platelet count was associated with lower HCQ and DHCQ blood concentrations in our study.

This study has some limitations. First, this study was limited by patient compliance, which may lead to bias. In our study, the mean HCQ concentration was significantly lower than that in other populations. Although we excluded patients with blood levels below 100 ng/ml, some patients may still be noncompliant with medication. One explanation for this could be that the study population were hospitalized patients, who tended to have more active SLE and were more likely to be nonadherent. Second, the sample size of this study was relatively small, and only hospital attenders were included, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population. Third, Lee et al. showed that HCQ and DHCQ blood concentrations may be influenced by genetic polymorphisms in CYP450 enzymes [32], but our study did not consider genetic factors. Future studies with larger sample sizes and more diverse populations, as well as consideration of genetic factors, may provide further insights into the factors that influence HCQ and DHCQ blood concentrations in patients with SLE.

Conclusions

In summary, this study found that several factors, including gender, age, weight, duration of HCQ use, SLEDAI, platelet count, and IgG levels, influenced the blood concentrations of HCQ. The duration of HCQ use, platelet count, SLEDAI, and gender were found to be influencing factors for low blood DHCQ concentrations. Notably, higher HCQ and DHCQ blood concentrations were beneficial in reducing disease activity, even if the concentrations were maintained below the recommended concentration. These findings suggested that examining the related factors and optimizing the dose according to individual characteristics might help to improve the efficacy of HCQ in Chinese patients with SLE.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients for participating in this study.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Weihong Ge and Yujie Zhou; data collection and assembly: Xuan Huang and Han Xie; data analysis and interpretation: Xuan Huang, Qing Shu and Xuemei Luo; article drafting: Xuan Huang; critical revision of the article: Han Xie; final approval of the article: all authors.

Funding

This work was supported by Jiangsu Research Hospital Association (YJ202112) and Jiangsu Pharmaceutical Association (Q202213). The Rapid Service Fee was funded by Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital.

Data Availability

The data sets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Xuan Huang, Han Xie, Qing Shu, Xuemei Luo, Weihong Ge, and Yujie Zhou have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (Approval number: 2021-643-02; Trial registration number: ChiCTR2300070628). All research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave written informed consent.

Footnotes

Xuan Huang and Han Xie contributed equally to this work and share the first authorship.

Contributor Information

Weihong Ge, Email: hanqing_214@hotmail.com.

Han Xie, Email: 185759811@qq.com.

Yujie Zhou, Email: yujiezhoum@163.com.

References

- 1.Al-Rawi H, Meggitt SJ, Williams FM, et al. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of hydroxychloroquine in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018;27:847–852. doi: 10.1177/0961203317727601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durcan L, Clarke WA, Magder LS, et al. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels in SLE: clarifying dosing controversies and improving adherence. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2092–2097. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M, Zhao Y, Zhang Z, et al. 2020 Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Immunol Res. 2020;1:5–23. doi: 10.2478/rir-2020-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tett SE, Cutler DJ, Beck C, et al. Concentration-effect relationship of hydroxychloroquine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis–a prospective, dose ranging study. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1656–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong X, Jin Y, Zhang Q, et al. Low estimated glomerular filtration rate is an independent risk factor for higher hydroxychloroquine concentration. Clin Rheumatol. 2023;42:1943–1950. doi: 10.1007/s10067-023-06576-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Guern LEV, Piette J-C. Routine hydroxychloroquine blood concentration measurement in systemic lupus erythematosus reaches adulthood. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:1997–1999. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.151094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zahr N, Urien S, Funck-Brentano C, et al. Evaluation of hydroxychloroquine blood concentrations and effects in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;14:273. doi: 10.3390/ph14030273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok CC. Therapeutic monitoring of the immuno-modulating drugs in systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:35–41. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1212659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fasano S, Messiniti V, Iudici M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine daily dose, hydroxychloroquine blood levels and the risk of flares in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med. 2023;10:e000841. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2022-000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ting TV, Kudalkar D, Nelson S, et al. Usefulness of cellular text messaging for improving adherence among adolescents and young adults with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:174–179. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu C-Y, Lin Y-S, Cheng T-T, et al. Adherence to hydroxychloroquine improves long-term survival of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology. 2018;57:1743–1751. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Amoura Z, Hulot J-S, et al. Low blood concentration of hydroxychloroquine is a marker for and predictor of disease exacerbations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3284–3290. doi: 10.1002/art.22156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rendic S, Guengerich FP. Metabolism and interactions of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine with human cytochrome P450 enzymes and drug transporters. Curr Drug Metab. 2020;21:1127–1135. doi: 10.2174/1389200221999201208211537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paniri A, Hosseini MM, Rasoulinejad A, et al. Molecular effects and retinopathy induced by hydroxychloroquine during SARS-CoV-2 therapy: Role of CYP450 isoforms and epigenetic modulations. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;886:173454. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munster T, Gibbs JP, Shen D, et al. Hydroxychloroquine concentration-response relationships in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1460–1469. doi: 10.1002/art.10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jallouli M, Galicier L, Zahr N, et al. Determinants of hydroxychloroquine blood concentration variations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:2176–2184. doi: 10.1002/art.39194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochberg MC. Updating the American college of rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725–1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iudici M, Pantano I, Fasano S, et al. Health status and concomitant prescription of immunosuppressants are risk factors for hydroxychloroquine non-adherence in systemic lupus patients with prolonged inactive disease. Lupus. 2018;27:265–272. doi: 10.1177/0961203317717631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Amoura Z, Hulot J-S, et al. Very low blood hydroxychloroquine concentration as an objective marker of poor adherence to treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:821–824. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.067835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo X, Peng Y, Ge W. A sensitive and optimized HPLC-FLD method for the simultaneous quantification of hydroxychloroquine and its two metabolites in blood of systemic lupus erythematosus patients. J Chromatogr Sci. 2020;58:600–605. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmaa023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeon Lee J, Lee J, Ki Kwok S, et al. Factors related to blood hydroxychloroquine concentration in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:536–542. doi: 10.1002/acr.22962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allegra S, De Francia S, De Nicolò A, et al. Effect of gender and age on voriconazole trough concentrations in Italian adult patients. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2020;45:405–412. doi: 10.1007/s13318-019-00603-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monostory K, Dvorak Z. Steroid regulation of drug-metabolizing cytochromes P450. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:154–172. doi: 10.2174/138920011795016854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ippolito MM, Flexner C. Dose optimization of hydroxychloroquine for coronavirus infection 2019: do blood concentrations matter? Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2965–2967. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dima A, Jurcut C, Arnaud L. Hydroxychloroquine in systemic and autoimmune diseases: where are we now? Jt Bone Spine. 2021;88:105143. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2021.105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tett SE, Cutler DJ, Day RO, et al. A dose-ranging study of the pharmacokinetics of hydroxy-chloroquine following intravenous administration to healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26:303–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb05281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haładyj E, Sikora M, Felis-Giemza A, et al. Antimalarials: are they effective and safe in rheumatic diseases? Reumatologia. 2018;56:164–173. doi: 10.5114/reum.2018.76904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udupa A, Leverenz D, Balevic SJ, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and COVID-19: a rheumatologist’s take on the lessons learned. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2021;21:5. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00983-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geamănu Pancă A, Popa-Cherecheanu A, Marinescu B, et al. Retinal toxicity associated with chronic exposure to hydroxychloroquine and its ocular screening. Rev J Med Life. 2014;7:322–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garg S, Unnithan R, Hansen KE, et al. Clinical significance of monitoring hydroxychloroquine levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2021;73:707–716. doi: 10.1002/acr.24155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Bari MAA. Chloroquine analogues in drug discovery: new directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:1608–1621. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JY, Vinayagamoorthy N, Han K, et al. Association of polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 with blood hydroxychloroquine levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:184–190. doi: 10.1002/art.39402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.