Abstract

Obesity is an important risk factor and common comorbidity of childhood asthma. Simultaneously, obesity-related asthma, a distinct asthma phenotype, has attracted significant attention owing to its association with more severe clinical manifestations, poorer disease control, and reduced quality of life. The establishment of the gut microbiota during early life is essential for maintaining metabolic balance and fostering the development of the immune system in children. Microbial dysbiosis influences host lipid metabolism, triggers chronic low-grade inflammation, and affects immune responses. It is intimately linked to the susceptibility to childhood obesity and asthma and plays a potentially crucial transitional role in the progression of obesity-related asthma. This review article summarizes the latest research on the interplay between asthma and obesity, with a particular focus on the mediating role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of obesity-related asthma. This study aims to provide valuable insight to enhance our understanding of this condition and offer preliminary evidence to support the development of therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: gut microbiota, obesity, asthma, children, lipid metabolism, chronic low-grade inflammation, immune

1. Introduction

Asthma and obesity are important public health concerns affecting children's health. According to data from the 2021 Global Asthma Network Stage I cross-sectional study, approximately 9.1% of children and 11% of adolescents had asthma in the previous year, with nearly half experiencing severe symptoms (Asher et al., 2021). In 2016, the worldwide prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents in boys and girls aged 5–19 years were 7.8 and 5.6%, respectively (Bentham et al., 2017). An estimated 206 million children and adolescents will experience obesity worldwide by 2025; this number is expected to reach 254 million by 2030 (Jebeile et al., 2022). Obesity and asthma are not simply coexisting conditions; research indicates that obese children have a >50% higher risk of developing asthma than normal-weight children (Malden et al., 2021). In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified obesity as a significant risk factor for asthma (Grossman et al., 2017).

The increased risk of childhood asthma due to obesity may be attributed to early-life experiences or parental factors. Notably, rapid weight gain during the initial 6–18 months after birth is strongly linked to a 2.1–3.3 times higher risk of non-atopic asthma; this correlation is particularly pronounced among boys (Ho et al., 2022). Furthermore, there is a linear relationship between the risk of childhood asthma and an increase in maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) (Rosenquist et al., 2023). Clinical symptoms tend to be more severe in children with comorbid asthma and obesity, who experience more frequent exacerbations. Additionally, disease control is often poorer in this group and characterized by reduced responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroids and an increased likelihood of unresponsiveness to bronchodilators (Peters et al., 2018). In 2014, the Global Initiative for Asthma identified “asthma with obesity” as an asthmatic phenotype (Reddel et al., 2015). The above evidence suggests a correlation between asthma and obesity and that obesity-related asthma has specific mechanisms and treatments.

Obesity complicates asthma phenotypes, and previous research highlighted its possibility associated with obesity-induced lipid status disturbances and chronic systemic inflammation (Miethe et al., 2020). In addition to classical atopic asthma, children with obesity-related asthma exhibit CD4+ T cells polarizing toward Th1 and Th17 profiles (Nyambuya et al., 2020; Leija-Mart́ınez et al., 2022). With technological advancements in the microbiome field, increasing evidence has linked obesity, asthma, and dysbiosis of the gut microbiota. The human body consists of trillions of microbes that congregate in the intestine to form a complex community known as the gut microbiota (Adak and Khan, 2019). The gut microbiota is a complicated and dynamic ecosystem that coevolves with the host, develops during infancy, and plateaus during adulthood (Bäckhed et al., 2015). It plays a role in regulating host lipid metabolism and the inflammatory response as well as stimulating the development of the immune system by assisting the host in digesting food and releasing nutrients (Yu et al., 2019; Zhuang et al., 2019). The disruption of healthy and timely microbial colonization has long-term health effects, particularly increased susceptibility to allergic and metabolic diseases (Lloyd and Marsland, 2017; Zhang and Dang, 2022). Increasing evidence suggests that the gut microbiota may play a bridging role in the mechanisms underlying the increased risk of obesity and asthma. However, this series of complex mechanism changes has yet to be fully elucidated and interconnected. This article summarizes the latest research on the correlation between obesity and asthma and provides a detailed explanation of the potential mediating mechanisms of the gut microbiota.

2. Impact of early-life gut microbiota colonization on asthma and obesity

2.1. Factors influencing early-life gut microbiota colonization

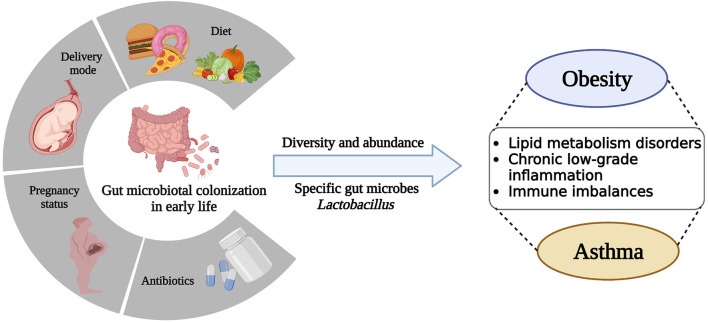

The postnatal period is often referred to as the “window of opportunity,” a critical time for microbial colonization as well as the rapid maturation and development of various systems in children, including the immune and metabolic systems (Johnson and DePaolo, 2017; Robertson et al., 2019). These systems evolve in tandem and are highly interdependent, strongly supporting children's growth. Maternal pregnancy status, delivery mode, diet, and early-life antibiotic treatment are important factors that influence gut microbial colonization and development (Gibson et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016a; Lundgren et al., 2018) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Early-life gut microbiota colonization is disturbed by a variety of factors, including pregnancy status, delivery mode, diet, and antibiotic treatment, leading to alterations in microbial diversity, abundance, and specific microbes, which ultimately contribute to dysfunction and disease in the host.

Whether the fetus environment in the womb is sterile remains inconclusive; however, scholars concur that the mother's nutritional and immune inflammatory state during pregnancy can affect the offspring's growth and development and that the gut microbiota potentially plays a mediating role in this process (Chu et al., 2016; Theis et al., 2019). A study reported that the placentas of women who experience excessive weight gain during pregnancy and preterm delivery are characterized by an increased abundance of Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Cyanobacteria and a decreased abundance of Proteobacteria (Antony et al., 2015).

Mode of delivery affects the neonatal gut microbiota. The microbiota of newborns delivered vaginally closely resembles that of the mother's birth canal, whereas that of newborns delivered via cesarean section closely resembles that of the mother's skin. The guts of newborns delivered vaginally is predominantly populated by Lactobacillus, Prevotella, Atopobium, and Sneathia spp., whereas that of newborns delivered via cesarean section is predominantly populated by Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Propionibacterium spp. with delayed colonization by the Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides genera (Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010; Jakobsson et al., 2014; Rutayisire et al., 2016).

Diet influences the composition and function of the gut microbiota. Compared to formula feeding, breastfeeding increases the diversity of gut microbiota species and alters the levels of specific bacterial genera by increasing the abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. and decreasing the abundance of Clostridium spp. and Bacteroides spp. (Savage et al., 2018). Changes in dietary patterns shape the gut microbiota of children as they age; these changes occur over a short period (David et al., 2014). One study reported that a high-fat diet (HFD) led to a decrease in microbial populations, alterations in species abundance, and increased in intestinal permeability (Turnbaugh et al., 2009). A low-fat diet decreases the relative abundance of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes, whereas a low-carbohydrate diet increases the relative abundance of Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes phyla (Fragiadakis et al., 2020).

Antibiotic administration eliminates antibiotic-sensitive bacteria and reduces the abundance and diversity of the gut microbiota in children. A previous study reported that azithromycin exposure reduces microbiota alpha diversity (McDonnell et al., 2021). It takes approximately 1 month for microbial diversity to recover after antibiotic administration in children (Yassour et al., 2016). However, exposure to antibiotics may increase the total microbial load in the gut by eliminating of sensitive bacteria and increasing in the reproduction of antibiotic-resistant microbiota (Panda et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2021). Furthermore, the inappropriate use of antibiotics can stimulate bacterial resistance, which can be transferred from the mother to the newborn (Karami et al., 2006).

2.2. Gut microbiota dysbiosis increases risks of childhood obesity and asthma

Delayed maturation and inappropriate development of the microbiome can disrupt the host's normal growth trajectory, leading to overnutrition and an immune imbalance (Gensollen and Blumberg, 2017). Numerous clinical studies and epidemiological data have consistently indicated that alterations in the diversity and specific species of the gut microbiota are associated with childhood obesity and asthma (Zhang et al., 2015; Garcia-Larsen et al., 2016). The mother's dietary pattern during pregnancy can influence the infant's gut microbiot; this exposure factor may affect the offspring's risk of asthma (Alsharairi, 2020). Breastfeeding increases the diversity of the gut microbiota in infants, which protects against childhood asthma and obesity (Oddy, 2017; Forbes et al., 2018). Children born via cesarean section are more prone to developing asthma and obesity than those born vaginally owing to disrupted gut microbiota colonization patterns; this effect continues during adolescence and adulthood (Yuan et al., 2016; Gürdeniz et al., 2022). Repeated exposure to antibiotics before 6 months of age is associated with weight gain during childhood (Saari et al., 2015). As antibiotic prescriptions decrease and the gut microbiota is protected, the incidence of childhood asthma has declined in certain regions of Europe and North America (Patrick et al., 2020).

An increased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes is a marker of gut microbial dysbiosis in obese children (Bervoets et al., 2013). The fecal microbiota of ob/ob and HFD-induced obese mice showed an increased abundance of Firmicutes and decreased abundance of Bacteroidetes (Ley et al., 2005; Jo et al., 2021). Firmicutes may mediate susceptibility to overweight/obesity during pregnancy and in offspring aged 1–3 years (Tun et al., 2018). A clinical trial reported a 20% increase in Firmicutes abundance resulting in a 150-kcal increase in energy absorption (Jumpertz et al., 2011). This suggests that a microbiota dominated by Firmicutes exhibits a higher energy extraction efficiency than that dominated by Bacteroidetes. Compared with the gut microbiota of their lean littermates, the gut microbiota of obese ob/ob mice is characterized by a higher abundance of indigestible dietary polysaccharides, such as starch, sucrose, and galactose, as well as Mollicutes, suggesting that obese ob/ob mice have a greater capacity to extract energy from food (Turnbaugh et al., 2006, 2008).

Several specific gut microbiota are correlated with asthma. Lower Bifidobacterium and Akkermansia loads and higher Candida and Rhodotorula loads are reportedly associated with atopic asthma in children (Fujimura et al., 2016). Significantly lower relative abundances of Lachnospira, Veillonella, Faecalibacterium, and Rothia genera early in life place infants at risk of later developing asthma (Arrieta et al., 2015). Probiotic intervention protects against allergic diseases in infants delivered via cesarean section who are at high risk of allergies; this beneficial effect was similarly observed in mice (Hogenkamp et al., 2015; Kallio et al., 2019). Lactobacillus supplementation ameliorates clinical symptoms in children with asthma, whereas Bifidobacterium supplementation reduces neutrophil and eosinophil infiltration in severely asthmatic mice (Huang et al., 2018b; Raftis et al., 2018).

Lactobacillus species may be involved in obesity-related asthma. Supplementation with Lactobacillus reportedly reduces airway inflammation and asthma symptoms in school-aged children while restoring anti-inflammatory fatty acid (FA) metabolites in infants at high risk for asthma (Chen et al., 2010; Durack et al., 2018). In obese individuals, treatment with Lactobacillus ameliorates body weight and reduces fat levels (Kadooka et al., 2010; Crovesy et al., 2017). Moreover, it significantly reduces adipose tissue accumulation in HFD-induced obese mice (Lee et al., 2021). In a recent study of asthma in obese mice, nitro-oleic acid treatment reduced lung and total respiratory elasticity, which has been associated with elevated Lactobacillus abundance (Heinrich et al., 2023). This study suggests a relationship between Lactobacillus and obesity-related asthma; however, the specific mechanisms involved require further investigation.

3. Mediating role of gut microbiota between childhood obesity and asthma

3.1. Lipid metabolism

3.1.1. Obesity-accompanied dysregulated lipid metabolism contributes to asthma development

Lipids are crucial components and energy reserves of cells with significant regulatory functions in metabolism, inflammation, immunity, and various other pathways. Lipid metabolism disorders are considered primary pathological factors contributing to obesity. Patients with asthma exhibit significant alterations in phospholipid and sphingolipid levels, suggesting that abnormalities in lipid metabolism are involved in asthma development (Murphy et al., 2021; Rago et al., 2021). Adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a key regulator of lipid metabolic balance in vivo (Herzig and Shaw, 2018). AMPK suppresses the process of de novo fatty acid synthesis (FAS) by causing inhibitory phosphorylation of Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase 1 (ACC1) (Jeon, 2016). Simultaneously, it promotes fatty acid oxidation (FAO) by facilitating inhibitory phosphorylation of ACC2, leading to the activation of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT-1) activity (Fang et al., 2022). AMPK levels are negatively correlated with obesity and asthma (Herzig and Shaw, 2018; Garcia et al., 2019). The AMPK pathway was inhibited in an obesity-related asthma model constructed through ovalbumin sensitization and stimulation; however, AMPK activation alleviated both airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR) in a mouse model (Zhu et al., 2019).

Lipid mediators produced via arachidonic acid (AA) pathway influence asthma (Monga et al., 2020). AA is stored in membrane phospholipids and released by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) upon exposure to allergens (Wang et al., 2021). PLA2 induces the enzymatic and non-enzymatic oxidation of AA to prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and other bioactive mediators, exerting receptor-specific stimulatory and inhibitory effects that influence the pathophysiology of asthma (Samuchiwal and Boyce, 2018). Increased protein expression of sPLA2-X in the airway epithelial cells of patients with asthma is associated with AHR (Hallstrand et al., 2013). In asthma models, prostaglandins E2 reduces lung inflammation and remodeling, showing beneficial effects in asthma patients (Insuela et al., 2020).

The adipocytokines leptin and adiponectin regulate lipid metabolism by influencing appetite. Leptin inhibits orexic neurons and stimulates anorexic proleptin neurons to regulate appetite (Obradovic et al., 2021). Adiponectin, on the other hand, increases during fasting, and activates the AMPK pathway by binding to its receptor AdipoR1 (Okada-Iwabu et al., 2013). In the adipose tissue of individuals with obesity, adipocyte cytokine leptin levels increase, whereas adiponectin levels decrease (Frithioff-Bøjsøe et al., 2020). Both adipocytokines and their receptors are expressed in human lungs and are associated with asthma severity in children. Leptin levels are positively correlated with the prevalence and severity of childhood asthma, whereas adiponectin levels are negatively correlated, particularly in boys (Assad and Sood, 2012).

3.1.2. Gut microbiota regulates asthma lipid metabolism: the key role of SCFAs

The impact of the gut microbiota on host lipid metabolism has been extensively demonstrated in both human and animal models. Implementing energy restriction and dietary interventions in obese individuals can increase the microbiota gene abundance while simultaneously reducing blood lipid levels (Cotillard et al., 2013). Conventional mice had a 60% higher body fat content and insulin resistance level than germ-free (GF) mice (Bäckhed et al., 2004). GF mice exhibited HFD-induced insulin resistance and improved cholesterol metabolism, which might be related to an increase in FAO in the peripheral tissues owing to enhanced AMPK activity in vivo (Rabot et al., 2010). The transplantation of gut microbiota from ob/ob mice into GF mice resulted in a notable increase in both body weight and body fat content (Turnbaugh et al., 2006). Young mice treated with antibiotics showed an altered gut microbiota composition and elevated levels of hormones related to carbohydrate, lipid, and cholesterol metabolism (Cho et al., 2012).

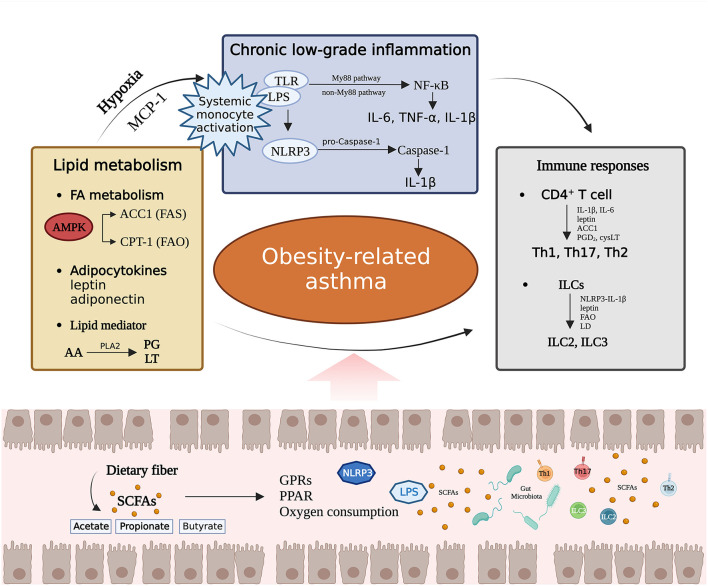

Short-chain FAs (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate and butyrate, are the final products of microbial fermentation (Ŕıos-Covián et al., 2016; Agus et al., 2021). SCFAs provide substrates for lipid synthesis and serve as regulatory factors to modulate lipid metabolism in both brown and white adipose tissues (Gao et al., 2009; Li et al., 2018; He et al., 2020). SCFAs regulate host biological processes via ligand receptor interactions with G protein-coupled receptors (GPRs), while peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) are a key family of ligand activated transcription factors that serve as crucial mediators in SCFA-induced regulation of metabolic syndrome (Kim et al., 2013; Den Besten et al., 2015). SCFAs stimulate secretion of the satiety hormones glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide YY (PYY) in a GPR41- and GPR43-dependent manner and increase leptin levels in adipose tissue, thereby reducing food intake and weight gain (Tolhurst et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2016; Larraufie et al., 2018). PPARγ is predominantly expressed in the adipose tissue, and in mice with adipose-specific PPARγ destruction, SCFA-induced weight loss and insulin sensitivity stimulation disappeared (Den Besten et al., 2015; Yip et al., 2021). In a mouse model of asthma with GPR43 deficiency, the beneficial therapeutic effects of SCFAs on inflammation were lost (Maslowski et al., 2009). Higher levels of butyrate and propionate in stool samples from 1-year-old humans are associated with reduced atopic sensitization in children and a reduced likelihood of asthma at 3–6 years of age, indicating that SCFAs affect a child's susceptibility to allergic diseases (Roduit et al., 2019). Treatment with vancomycin reduced the decreased levels of SCFAs in mice, making them more susceptible to OVA-induced asthma, and supplementing exogenous SCFAs could alleviate this effect (Cait et al., 2018). This evidence supports the idea that SCFAs produced by fermentation of the gut microbiota may be a significant factor in obesity-related asthma susceptibility (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effects of the gut microbiota on lipid metabolism, chronic low-grade inflammation, and immunity, as well as the interactions among the three pathways. PG, prostaglandin; LT, leukotriene; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; PGD2, prostaglandin D2; cysLT, cysteinyl leukotriene; LD, Lipid droplet.

3.2. Chronic low-grade inflammation

3.2.1. Obesity-associated chronic low-grade inflammation impacts asthma pathophysiology

Obese individuals exhibit characteristics of systemic chronic low-grade inflammation driven by relative hypoperfusion or increased oxygen consumption and sustained by leptin, leading to systemic monocyte activation (Lee et al., 2014; Reyes-Angel et al., 2022). Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, secreted by the adipose tissue, binds to the monocyte surface receptor C-C chemokine receptor type 2 to promote monocyte activation and recruitment into the adipose tissue to form macrophages (Yao et al., 2022). Clinical studies revealed an inverse correlation between circulating monocytes in children with obesity-related asthma and low high-density lipoprotein levels along with significantly increased levels of soluble CD163, a measure of macrophage activation (Periyalil et al., 2015; Rastogi et al., 2015).

Macrophages directly sense pathogens through the expression of Toll-like receptors (TLR) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLR) (Sharma et al., 2018). FAs enhance TLR activation signals and are associated with the onset and progression of adolescent metabolic syndrome and asthma (Hardy et al., 2013; Zuo et al., 2015; Rocha et al., 2016; Meghnem et al., 2022). TLR recognition ligands activate various adaptor proteins downstream of myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88)-dependent or non-MyD88-dependent pathways, initiating an inflammatory cascade that leads to the activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), resulting in an increased release of interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-1β (Kawai and Akira, 2010; Jialal et al., 2014). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a classical TLR ligand. Whether LPS exposure is a protective or aggravating factor against asthma remains controversial. The role of LPS in airway inflammation has been observed in children with neutrophil asthma, and it induces macrophage inflammatory responses in mice (Camargo et al., 2018; Ciesielska et al., 2022). However, other studies suggested that the protective effect of the “farm effect” on asthma is specifically associated with LPS exposure. Importantly, this protective effect has only been observed during infancy (Schuijs et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2021).

NLRP3 is an important member of the NLR family (Wang and Hauenstein, 2020). NLRP3 expression is upregulated in response to TLR, activated by phosphorylation and deubiquitination, and then activated by stimuli such as porotoxins, leading to subsequent oligomerization, and inflammasome assembly (Song and Li, 2018). The assembled NLRP3 inflammasome cleaves pro-Caspase-1 proteolysis into mature Caspase-1 to promote the release of the inflammatory factors IL-1β and IL-18, mediating immune imbalances in asthma (Huang et al., 2021). NLRP3 inflammasome activation is a key phenotypic feature of obesity-related asthma, and NLRP3 gene expression in the sputum of patients with obesity-related asthma is significantly increased and correlated with BMI (Wood et al., 2019).

3.2.2. Gut microbiota influences asthma inflammation: the significance of LPS and NLRP3

A significant quantity of LPS accumulates in the intestine and enters the circulatory system by attaching to newly synthesized chylomicrons in the intestinal cell epithelium or increasing intestinal permeability, stimulating the immune response, and activating the TLR signaling pathway (Ghoshal et al., 2009; Velasquez, 2018). A host's LPS levels are influenced by the gut microbiota. Proinflammatory bacteria such as Proteobacteria carry Gram-negative LPS, and the HFD mice exhibited an increase in Proteobacteria abundance along with elevated levels of LPS (Mujico et al., 2013). Antibiotic intervention significantly reduces in LPS levels in the gut and circulation of HFD and ob/ob mice (Cani et al., 2008). Additionally, supplementation with Bifidobacterium reduced mouse intestinal LPS levels and improved gut barrier function (Cani et al., 2007). The gut microbiota stimulates the mucosal epithelial cells to release secretory immunoglobulin (Ig) A, mucin 2, and β-defensin, which are crucial for maintaining the intestinal mucosal barrier, reducing LPS translocation, and alleviating lung inflammatory damage (Dicks et al., 2018). Mouse experiments demonstrated that the gut microbiota activates the lung TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway via the lung intestinal axis, aggravating LPS-induced acute lung injury (ALI) and that fecal microbiota transplantation can restore intestinal microbiotal homeostasis, increase intestinal flora diversity, and inhibit LPS-induced ALI (Tang et al., 2021). A cohort study reported that the immune response of asthmatic 17q21 risk allele carriers to LPS is regulated by the gut microbiota (Illi et al., 2022).

The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in mediating NLRP3 activation and inflammatory damage (Pellegrini et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2022). El Tor Vibrio cholerae triggers the NLRP3-dependent pathway, which induces IL-1β-mediated inflammatory responses that drive mouse macrophage death (BMDMs) (Mamantopoulos et al., 2019). In addition to specific species of gut microbes, he Rho GTPase activator CNF1, from Escherichia coli (E. coli) activates NLRP3 in BMDMs and leads to caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β (Dufies et al., 2021). Probiotics present in the gut inhibit inflammasome expression. For instance, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 effectively reduces the expression of NLRP3 inflammatory bodies and caspase-1 induced by E. Coli, thereby limiting the occurrence of harmful inflammatory responses (Wu et al., 2016b). In an inflammatory bowel disease mouse model, it was discovered that NLRP3 mediated lung neutrophilic infiltrative inflammation in microbial pattern recognition, leading to increased levels of TNF and IL-1β levels in murine lungs (Liu et al., 2019). Furthermore, the gut microbiota exacerbated OVA-induced allergic asthma through the NLRP3/IL-1β signaling pathway in asthma model mice (Huang et al., 2018a; Zheng et al., 2022) (Figure 2).

3.3. Immune dysregulation

3.3.1. Obesity-related immune dysregulation influences the onset of asthma

CD4+ T cells play a central role in the pathogenesis of asthma. Activated CD4+ T cells are divided into two subsets—T regulatory (Treg) and T effector (Teff) cells (Th1/Th2/Th17) with the former playing an immune regulatory role and the latter driving asthma pathogenesis and determining the asthmatic phenotype (Zhu et al., 2009). Under the influence of obesity, children with asthma exhibit a tendency for Teff cells to polarize toward Th1 and Th17 profiles. Multiple cytokines secreted by Th1 and Th17 cells mediate the development of neutrophilic asthma and are associated with asthma severity and steroid resistance (Nyambuya et al., 2020; Sze et al., 2020). Teff differentiation depends on the FAS pathway (Berod et al., 2014). Th17 cells polarization is boosted by increased ACC1 gene expression and retinoic acid receptor related orphan receptor-γ t (RORγ t) binding to the IL-17 gene locus (Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, Th1 polarization in obesity-related asthma is influenced by macrophage activation and correlated with IL-6 and leptin levels (Reyes-Angel et al., 2022). Monocytes produce large amounts of IL-1β, which mediates Th17 cell differentiation (Revu et al., 2018). Obesity and atopic immunity are not mutually exclusive (Reyes-Angel et al., 2022). In obese children and adolescents, Th2-type asthma is associated with increased eosinophil infiltration and activity (Grotta et al., 2013). Furthermore, increased IgE levels and eosinophilic activation have been observed in obese mice (Amorim et al., 2018; Cvejoska-Cholakovska et al., 2019; Ying et al., 2022). This phenomenon is positively correlated with serum leptin and TNF-α levels (Grotta et al., 2013). Additionally, lipid mediators prostaglandin D2 and cysteinyl leukotriene can also activate Th2 cells and enhance the production of Th2 cell cytokines (Xue et al., 2015).

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are innate T lymphocytes that express a profile of effector cytokines similar to those of T cells, enhance T cell function, and play a crucial role in asthma progression (Vivier et al., 2018). High ILC3 cell counts and RORC mRNA expression have been observed in the peripheral blood circulation of children with obesity-related asthma (Wu et al., 2018). In the lungs of obesity-related asthma mice, the NLRP3-IL-1β pathway is activated to induce the expansion of lung IL-17+ILC3 cells, leading to neutrophilic inflammation (Kim et al., 2014). In obese mice with AHR, ILC2 counts are increased, acting as Th2 cells but producing 10 times more IL-5 and IL-13 than activated Th2 cells (Everaere et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017). The proliferation and function of ILC2 are influenced by lipid metabolism. Lipid droplets provide an energy source for pathogenic ILC2 responses during airway inflammation (Karagiannis et al., 2020). FAO and leptin play roles in driving ILC2 proliferation and maintaining their function (Wilhelm et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2017). Under the chemotactic influence of lipids and inflammation, ILCs migrate within and between organs (Soriani et al., 2018). For example, sphingosine-1-phosphate mediates the migration of ILC2 to different tissues, thereby promoting the accumulation of ILC2 in lymphoid tissues, the bloodstream, and the lungs (Huang et al., 2018c).

3.3.2. Gut microbiota modulates asthma immune response: focusing on CD4+ T cell and ILCs

A series of studies on antibiotic-treated and GF mice support the role of the gut microbiota in influencing T cell differentiation. Antibiotic-treated mice showed elevated levels of Th2 cytokines and IgE (Bashir et al., 2004). GF mice exhibit a loss of Th17 cells in the intestinal lamina propria and are more likely to produce a Th2 response (Wu et al., 2010; Herbst et al., 2011). A recent single-cell transcriptome study revealed that gut Teff are shaped by the microbiota independent of the typical subgroup regulators, T-bet, GATA3, or RORγt (Kiner et al., 2021). Several microbes, such as Akkermansia muciniphila, Citrobacter rodentium, and Fusobacteriu varium, induce T cell differentiation (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017; Stockinger, 2021; Liu et al., 2022). The influence of the microbiota on immune regulation can be transmitted to the offspring through the mother's gut microbiota and metabolites, thus accelerating the postpartum transition of the offspring from a Th2-dominated immunophenotype to Th1- and Th17-dominated immunophenotypes (Gao et al., 2021). The microbiota colonizing in the gut crosstalk pulmonary immunity via the gut lung axis, influencing host atopy and asthma (Pascal et al., 2018). CD4+ T cell dysfunction caused by dysregulation of the gut microbiota has been observed in newborns and is associated with susceptibility to allergic asthma in childhood (Fujimura et al., 2016). Segmented filamentous bacteria trigger a strong Th17-cell response in the gut and are preferentially recruited to the lungs to trigger immune inflammation (Bradley et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Ruminiclostridium 6 and Candidatus Arthromitus mediate Th1/Th2 and Treg/Th17 immune balance in eosinophilic asthma in mice, suggesting that gut microbes regulate the balance between Teff subsets and participate in the pathogenesis of asthma (Zhou et al., 2022).

The response of ILCs to the gut microbiota is highly heterogeneous. ILCs expression are suppressed by microbial signal deficiency resulting from antibiotic treatment, with a greater impact observed on the gene expression profiles of ILC1 and ILC2 than ILC3 (Gury-BenAri et al., 2016). Clostridioides difficile infection upregulates the expressions of ILC1 and ILC3 in the colon, whereas Helicobacter typhlonius and Helicobacter apodemus infections lead to the ILC3 loss in the colon (Abt et al., 2015; Bostick et al., 2019; Kong et al., 2021). SCFAs activate ILCs via GPR signaling, promote ILC3 proliferation and IL-22 production, and inhibit ILC2 amplification (Yang et al., 2020; Sepahi et al., 2021). Furthermore, the gut microbiota promotes ILC3 production in the intestinal mucosa by assisting mononuclear phagocytes in secreting IL-1β and facilitating crosstalk between colony-stimulating factor 2 and RORγt+ cells (Mortha et al., 2014). The increase in intestinal ILC3 in the offspring of GF female mice after the implantation of E. coli HA 107 during pregnancy suggests that ILC formation by gut microbiota can be transmitted from the parents to the offspring (Gomez de Agüero et al., 2016). The gut microbiota regulates ILCs through the gut lung axis and contribute to airway inflammation and asthma. A previous study reported that Proteobacteria may promote the accumulation of natural ILC2 in the lungs by regulating the IL-33-CXCL16-CXCR6 signaling axis and interfering with the lung immune response (Pu et al., 2021). In a mouse model of asthma sensitized to house dust mites and characterized by gut dysbiosis attributed to Candida spp., there was an increase in lung ILC2 content, which resulted in exacerbated allergic airway inflammation and worsened disease control (Kanj et al., 2023). It suggests that gut microbiota imbalance may affect asthma symptoms through the regulation of ILC2 pathways (Figure 2).

4. Conclusion

Asthma is a complex disease with various phenotypes and endotypes, and related research should be focused on its well-defined classifications. The pathological basis of asthma in obese children is unique and involves multiple pathways, and the gut microbiota plays a pivotal role. Numerous clinical studies and basic experiments have confirmed the presence of gut microbiota dysbiosis in both obesity and asthma, indirectly indicating the involvement of the gut microbiota in the high-risk pathogenesis of obesity-related asthma. However, relevant clinical studies are lacking that explore the characteristics of gut microbiota dysbiosis in obese asthma patients, including the overall changes and exploration of specific strains. Therefore, the specific mechanisms by which alterations in the gut microbiota due to obesity lead to asthma have not yet been fully elucidated.

This article discusses various factors that influence the colonization and development of the gut microbiota, emphasizing the significant impact of early-life microbial dysbiosis on the susceptibility and progression of allergic and metabolic diseases in children. Furthermore, we elaborated on the role of the gut microbiota in regulating lipid metabolism, chronic inflammatory states, and immune responses, highlighting the potential key role of ecological imbalance in the pathogenesis of obesity-related asthma. This study's findings suggest that modulation of the gut microbiota could serve as an early therapeutic and preventive target for diseases such as asthma and obesity. However, clinical research on the characteristics of gut microbiota dysbiosis in obesity-related asthma, including overall changes and specific bacterial strains, remains scarce. Whether modulating the gut microbiota can be used as an early treatment and prevention target for diseases such as obesity, asthma, and obesity-related asthma requires extensive clinical and basic research. Relevant animal models must be refined to closely simulate human clinical conditions with particular attention paid to incorporating diverse age groups and their specific physiological and pathological backgrounds.

Author contributions

MH: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. XZ: Writing—original draft. YL: Writing—review & editing. HZ: Writing—review & editing. YY: Writing—review & editing. ZX: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82274576), Future Planning Project of Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. WLJH2021ZY-MZY019), and Construction of the Xu's Pediatric Academic Inheritance and Innovation Team in the Traditional Chinese Medicine of the Shanghai school (No. 2021LPTD-006).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abt M. C., Lewis B. B., Caballero S., Xiong H., Carter R. A., Sušac B., et al. (2015). Innate immune defenses mediated by two ilc subsets are critical for protection against acute clostridium difficile infection. Cell Host Microbe 18, 27–37. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adak A., Khan M. R. (2019). An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell. Molec. Life Sci. 76, 473–493. 10.1007/s00018-018-2943-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agus A., Clément K., Sokol H. (2021). Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 70, 1174–1182. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsharairi N. A. (2020). The infant gut microbiota and risk of asthma: The effect of maternal nutrition during pregnancy and lactation. Microorganisms 8, 1119. 10.3390/microorganisms8081119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim N. R., Luna-Gomes T., Gama-Almeida M., Souza-Almeida G., Canetti C., Diaz B. L., et al. (2018). Leptin elicits ltc4 synthesis by eosinophils mediated by sequential two-step autocrine activation of ccr3 and pgd2 receptors. Front. Immunol. 9, 2139. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony K. M., Ma J., Mitchell K. B., Racusin D. A., Versalovic J., Aagaard K. (2015). The preterm placental microbiome varies in association with excess maternal gestational weight gain. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 212, 653–e1. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta M.-C., Stiemsma L. T., Dimitriu P. A., Thorson L., Russell S., Yurist-Doutsch S., et al. (2015). Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 307ra152–307ra152. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher M. I., Rutter C. E., Bissell K., Chiang C.-Y., El Sony A., Ellwood E., et al. (2021). Worldwide trends in the burden of asthma symptoms in school-aged children: Global asthma network phase i cross-sectional study. Lancet 398, 1569–1580. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01450-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assad N. A., Sood A. (2012). Leptin, adiponectin and pulmonary diseases. Biochimie 94, 2180–2189. 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckhed F., Ding H., Wang T., Hooper L. V., Koh G. Y., Nagy A., et al. (2004). The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 15718–15723. 10.1073/pnas.0407076101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckhed F., Roswall J., Peng Y., Feng Q., Jia H., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., et al. (2015). Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe 17, 690–703. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M. E. H., Louie S., Shi H. N., Nagler-Anderson C. (2004). Toll-like receptor 4 signaling by intestinal microbes influences susceptibility to food allergy. J. Immunol. 172, 6978–6987. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentham J., Di Cesare M., BIlano V., Boddy L. M. (2017). Worldwide trends in children's and adolescents' body mass index, underweight and obesity, in comparison with adults, from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2,416 population-based measurement studies with 128.9 million participants. Lancet. 390, 2627–2642. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berod L., Friedrich C., Nandan A., Freitag J., Hagemann S., Harmrolfs K., et al. (2014). De novo fatty acid synthesis controls the fate between regulatory t and t helper 17 cells. Nat. Med. 20, 1327–1333. 10.1038/nm.3704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bervoets L., Van Hoorenbeeck K., Kortleven I., Van Noten C., Hens N., Vael C., et al. (2013). Differences in gut microbiota composition between obese and lean children: a cross-sectional study. Gut Pathog. 5, 1–10. 10.1186/1757-4749-5-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick J. W., Wang Y., Shen Z., Ge Y., Brown J., Chen Z.-m. E., et al. (2019). Dichotomous regulation of group 3 innate lymphoid cells by nongastric helicobacter species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 24760–24769. 10.1073/pnas.1908128116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley C. P., Teng F., Felix K. M., Sano T., Naskar D., Block K. E., et al. (2017). Segmented filamentous bacteria provoke lung autoimmunity by inducing gut-lung axis th17 cells expressing dual tcrs. Cell Host Microbe 22, 697–704. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cait A., Hughes M., Antignano F., Cait J., Dimitriu P., Maas K., et al. (2018). Microbiome-driven allergic lung inflammation is ameliorated by short-chain fatty acids. Mucosal Immunol. 11, 785–795. 10.1038/mi.2017.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo L. d. N., Righetti R. F., Aristóteles L. R. d. C. R. B., Dos Santos T. M., De Souza F. C. R., et al. (2018). Effects of anti-il-17 on inflammation, remodeling, and oxidative stress in an experimental model of asthma exacerbated by lps. Front. Immunol. 8, 1835. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D., Bibiloni R., Knauf C., Waget A., Neyrinck A. M., Delzenne N. M., et al. (2008). Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57, 1470–1481. 10.2337/db07-1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D., Neyrinck A. M., Fava F., Knauf C., Burcelin R. G., Tuohy K. M., et al. (2007). Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia 50, 2374–2383. 10.1007/s00125-007-0791-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Smith S. G., Salter B., El-Gammal A., Oliveria J. P., Obminski C., et al. (2017). Allergen-induced increases in sputum levels of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in subjects with asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196, 700–712. 10.1164/rccm.201612-2427OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-S., Lin Y.-L., Jan R.-L., Chen H.-H., Wang J.-Y. (2010). Randomized placebo-controlled trial of lactobacillus on asthmatic children with allergic rhinitis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 45, 1111–1120. 10.1002/ppul.21296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I., Yamanishi S., Cox L., Methé B. A., Zavadil J., Li K., et al. (2012). Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature 488, 621–626. 10.1038/nature11400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D. M., Meyer K. M., Prince A. L., Aagaard K. M. (2016). Impact of maternal nutrition in pregnancy and lactation on offspring gut microbial composition and function. Gut Microbes 7, 459–470. 10.1080/19490976.2016.1241357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielska A., Krawczyk M., Sas-Nowosielska H., Hromada-Judycka A., Kwiatkowska K. (2022). Cd14 recycling modulates lps-induced inflammatory responses of murine macrophages. Traffic 23, 310–330. 10.1111/tra.12842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotillard A., Kennedy S. P., Kong L. C., Prifti E., Pons N., Le Chatelier E., et al. (2013). Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature 500, 585–588. 10.1038/nature12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crovesy L., Ostrowski M., Ferreira D., Rosado E., Soares-Mota M. (2017). Effect of lactobacillus on body weight and body fat in overweight subjects: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Int. J. Obes. 41, 1607–1614. 10.1038/ijo.2017.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvejoska-Cholakovska V., Kocova M., Velikj-Stefanovska V., Vlashki E. (2019). The association between asthma and obesity in children-inflammatory and mechanical factors. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 7, 1314. 10.3889/oamjms.2019.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David L. A., Maurice C. F., Carmody R. N., Gootenberg D. B., Button J. E., Wolfe B. E., et al. (2014). Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563. 10.1038/nature12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Besten G., Bleeker A., Gerding A., van Eunen K., Havinga R., van Dijk T. H., et al. (2015). Short-chain fatty acids protect against high-fat diet-induced obesity via a pparγ-dependent switch from lipogenesis to fat oxidation. Diabetes 64, 2398–2408. 10.2337/db14-1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicks L. M., Dreyer L., Smith C., Van Staden A. D. (2018). A review: the fate of bacteriocins in the human gastro-intestinal tract: do they cross the gut-blood barrier? Front. Microbiol. 9, 2297. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Bello M. G., Costello E. K., Contreras M., Magris M., Hidalgo G., Fierer N., et al. (2010). Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 11971–11975. 10.1073/pnas.1002601107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufies O., Doye A., Courjon J., Torre C., Michel G., Loubatier C., et al. (2021). Escherichia coli rho gtpase-activating toxin cnf1 mediates nlrp3 inflammasome activation via p21-activated kinases-1/2 during bacteraemia in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 401–412. 10.1038/s41564-020-00832-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durack J., Kimes N. E., Lin D. L., Rauch M., McKean M., McCauley K., et al. (2018). Delayed gut microbiota development in high-risk for asthma infants is temporarily modifiable by lactobacillus supplementation. Nat. Commun. 9, 707. 10.1038/s41467-018-03157-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everaere L., Ait-Yahia S., Molendi-Coste O., Vorng H., Quemener S., LeVu P., et al. (2016). Innate lymphoid cells contribute to allergic airway disease exacerbation by obesity. J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 138, 1309–1318. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang C., Pan J., Qu N., Lei Y., Han J., Zhang J., et al. (2022). The ampk pathway in fatty liver disease. Front. Physiol. 13, 970292. 10.3389/fphys.2022.970292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes J. D., Azad M. B., Vehling L., Tun H. M., Konya T. B., Guttman D. S., et al. (2018). Association of exposure to formula in the hospital and subsequent infant feeding practices with gut microbiota and risk of overweight in the first year of life. JAMA Pediatr. 172, e181161–e181161. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragiadakis G. K., Wastyk H. C., Robinson J. L., Sonnenburg E. D., Sonnenburg J. L., Gardner C. D. (2020). Long-term dietary intervention reveals resilience of the gut microbiota despite changes in diet and weight. The Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 111, 1127–1136. 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frithioff-Bøjsøe C., Lund M. A., Lausten-Thomsen U., Hedley P. L., Pedersen O., Christiansen M., et al. (2020). Leptin, adiponectin, and their ratio as markers of insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk in childhood obesity. Pediatr. Diab. 21, 194–202. 10.1111/pedi.12964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura K. E., Sitarik A. R., Havstad S., Lin D. L., Levan S., Fadrosh D., et al. (2016). Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and t cell differentiation. Nat. Med. 22, 1187–1191. 10.1038/nm.4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Nanan R., Macia L., Tan J., Sominsky L., Quinn T. P., et al. (2021). The maternal gut microbiome during pregnancy and offspring allergy and asthma. J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 148, 669–678. 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Yin J., Zhang J., Ward R. E., Martin R. J., Lefevre M., et al. (2009). Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes 58, 1509–1517. 10.2337/db08-1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D., Hellberg K., Chaix A., Wallace M., Herzig S., Badur M. G., et al. (2019). Genetic liver-specific ampk activation protects against diet-induced obesity and nafld. Cell Rep. 26, 192–208. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Larsen V., Del Giacco S. R., Moreira A., Bonini M., Charles D., Reeves T., et al. (2016). Asthma and dietary intake: an overview of systematic reviews. Allergy 71, 433–442. 10.1111/all.12800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensollen T., Blumberg R. S. (2017). Correlation between early-life regulation of the immune system by microbiota and allergy development. J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 139, 1084–1091. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva-Zatorsky N., Sefik E., Kua L., Pasman L., Tan T. G., Ortiz-Lopez A., et al. (2017). Mining the human gut microbiota for immunomodulatory organisms. Cell 168, 928–943. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoshal S., Witta J., Zhong J., De Villiers W., Eckhardt E. (2009). Chylomicrons promote intestinal absorption of lipopolysaccharides. J. Lipid Res. 50, 90–97. 10.1194/jlr.M800156-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson M. K., Crofts T. S., Dantas G. (2015). Antibiotics and the developing infant gut microbiota and resistome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 27, 51–56. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez de Agüero M., Ganal-Vonarburg S. C., Fuhrer T., Rupp S., Uchimura Y., Li H., et al. (2016). The maternal microbiota drives early postnatal innate immune development. Science 351, 1296–1302. 10.1126/science.aad2571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman D. C., Bibbins-Domingo K., Curry S. J., Barry M. J., Davidson K. W., Doubeni C. A., et al. (2017). Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: Us preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 317, 2417–2426. 10.1001/jama.2017.6803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotta M. B., Squebola-Cola D. M., Toro A. A., Ribeiro M. A. G., Mazon S. B., Ribeiro J. D., et al. (2013). Obesity increases eosinophil activity in asthmatic children and adolescents. BMC Pulmon. Med. 13, 1–8. 10.1186/1471-2466-13-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürdeniz G., Ernst M., Rago D., Kim M., Courraud J., Stokholm J., et al. (2022). Neonatal metabolome of caesarean section and risk of childhood asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 59, 2102406. 10.1183/13993003.02406-2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gury-BenAri M., Thaiss C. A., Serafini N., Winter D. R., Giladi A., Lara-Astiaso D., et al. (2016). The spectrum and regulatory landscape of intestinal innate lymphoid cells are shaped by the microbiome. Cell 166, 1231–1246. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallstrand T. S., Lai Y., Altemeier W. A., Appel C. L., Johnson B., Frevert C. W., et al. (2013). Regulation and function of epithelial secreted phospholipase a2 group x in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 42–50. 10.1164/rccm.201301-0084OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy O. T., Kim A., Ciccarelli C., Hayman L. L., Wiecha J. (2013). Increased toll-like receptor (tlr) mrna expression in monocytes is a feature of metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 8, e19–e23. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00098.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Zhang P., Shen L., Niu L., Tan Y., Chen L., et al. (2020). Short-chain fatty acids and their association with signalling pathways in inflammation, glucose and lipid metabolism. Int. J. Molec. Sci. 21, 6356. 10.3390/ijms21176356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich V. A., Uvalle C., Manni M. L., Li K., Mullett S. J., Donepudi S. R., et al. (2023). Meta-omics profiling of the gut-lung axis illuminates metabolic networks and host-microbial interactions associated with elevated lung elastance in a murine model of obese allergic asthma. Front. Microb. 2, 1153691. 10.3389/frmbi.2023.1153691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst T., Sichelstiel A., Schär C., Yadava K., Bürki K., Cahenzli J., et al. (2011). Dysregulation of allergic airway inflammation in the absence of microbial colonization. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 198–205. 10.1164/rccm.201010-1574OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzig S., Shaw R. J. (2018). Ampk: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Molec. Cell Biol. 19, 121–135. 10.1038/nrm.2017.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.-H., Gau C.-C., Lee W.-F., Fang H., Lin C.-H., Chu C.-H., et al. (2022). Early-life weight gain is associated with non-atopic asthma in childhood. World Aller. Organ. J. 15, 100672. 10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenkamp A., Knippels L. M., Garssen J., van Esch B. C. (2015). Supplementation of mice with specific nondigestible oligosaccharides during pregnancy or lactation leads to diminished sensitization and allergy in the female offspring. J. Nutr. 145, 996–1002. 10.3945/jn.115.210401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang J., Zheng X., Chen Y., Zhou R., Wei H., et al. (2018a). Commensal bacteria aggravate allergic asthma via nlrp3/il-1β signaling in post-weaning mice. J. Autoimmunity 93, 104–113. 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-F., Chie W.-C., Wang I.-J. (2018b). Efficacy of lactobacillus administration in school-age children with asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 10, 1678. 10.3390/nu10111678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Mao K., Chen X., Sun M.-,a., Kawabe T., Li W., et al. (2018c). S1p-dependent interorgan trafficking of group 2 innate lymphoid cells supports host defense. Science 359, 114–119. 10.1126/science.aam5809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Xu W., Zhou R. (2021). Nlrp3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell. Molec. Immunol. 18, 2114–2127. 10.1038/s41423-021-00740-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illi S., Depner M., Pfefferle P. I., Renz H., Roduit C., Taft D. H., et al. (2022). Immune responsiveness to lps determines risk of childhood wheeze and asthma in 17q21 risk allele carriers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 205, 641–650. 10.1164/rccm.202106-1458OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insuela D. B. R., Ferrero M. R., Coutinho D. D. S., Martins M. A., Carvalho V. F. (2020). Could arachidonic acid-derived pro-resolving mediators be a new therapeutic strategy for asthma therapy? Front. Immunol. 11, 580598. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.580598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson H. E., Abrahamsson T. R., Jenmalm M. C., Harris K., Quince C., Jernberg C., et al. (2014). Decreased gut microbiota diversity, delayed bacteroidetes colonisation and reduced th1 responses in infants delivered by caesarean section. Gut 63, 559–566. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jebeile H., Kelly A. S., O'Malley G., Baur L. A. (2022). Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 10, 351–365. 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00047-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S.-M. (2016). Regulation and function of ampk in physiology and diseases. Exper. Molec. Med. 48, e245–e245. 10.1038/emm.2016.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jialal I., Kaur H., Devaraj S. (2014). Toll-like receptor status in obesity and metabolic syndrome: a translational perspective. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 39–48. 10.1210/jc.2013-3092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J.-K., Seo S.-H., Park S.-E., Kim H.-W., Kim E.-J., Kim J.-S., et al. (2021). Gut microbiome and metabolome profiles associated with high-fat diet in mice. Metabolites 11, 482. 10.3390/metabo11080482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. M., DePaolo R. W. (2017). Window-of-opportunity: neonatal gut microbiota and atopy. Hepatob. Surg. Nutr. 6, 190. 10.21037/hbsn.2017.03.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumpertz R., Le D. S., Turnbaugh P. J., Trinidad C., Bogardus C., Gordon J. I., et al. (2011). Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. The Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 94, 58–65. 10.3945/ajcn.110.010132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadooka Y., Sato M., Imaizumi K., Ogawa A., Ikuyama K., Akai Y., et al. (2010). Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (lactobacillus gasseri sbt2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 636–643. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio S., Kukkonen A. K., Savilahti E., Kuitunen M. (2019). Perinatal probiotic intervention prevented allergic disease in a caesarean-delivered subgroup at 13-year follow-up. Clin. Exper. Aller. 49, 506–515. 10.1111/cea.13321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanj A. N., Kottom T. J., Schaefbauer K. J., Choudhury M., Limper A. H., Skalski J. H. (2023). Dysbiosis of the intestinal fungal microbiota increases lung resident group 2 innate lymphoid cells and is associated with enhanced asthma severity in mice and humans. Respir. Res. 24, 1–5. 10.1186/s12931-023-02422-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis F., Masouleh S. K., Wunderling K., Surendar J., Schmitt V., Kazakov A., et al. (2020). Lipid-droplet formation drives pathogenic group 2 innate lymphoid cells in airway inflammation. Immunity 52, 620–634. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karami N., Nowrouzian F., Adlerberth I., Wold A. E. (2006). Tetracycline resistance in escherichia coli and persistence in the infantile colonic microbiota. Antimicr. Agents Chemother. 50, 156–161. 10.1128/AAC.50.1.156-161.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T., Akira S. (2010). The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384. 10.1038/ni.1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Y., Lee H. J., Chang Y.-J., Pichavant M., Shore S. A., Fitzgerald K. A., et al. (2014). Interleukin-17-producing innate lymphoid cells and the nlrp3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat. Med. 20, 54–61. 10.1038/nm.3423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. H., Kang S. G., Park J. H., Yanagisawa M., Kim C. H. (2013). Short-chain fatty acids activate gpr41 and gpr43 on intestinal epithelial cells to promote inflammatory responses in mice. Gastroenterology 145, 396–406. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiner E., Willie E., Vijaykumar B., Chowdhary K., Schmutz H., Chandler J., et al. (2021). Gut cd4+ t cell phenotypes are a continuum molded by microbes, not by th archetypes. Nat. Immunol. 22, 216–228. 10.1038/s41590-020-00836-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong C., Yan X., Liu Y., Huang L., Zhu Y., He J., et al. (2021). Ketogenic diet alleviates colitis by reduction of colonic group 3 innate lymphoid cells through altering gut microbiome. Signal Transd. Targeted Ther. 6, 154. 10.1038/s41392-021-00549-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larraufie P., Martin-Gallausiaux C., Lapaque N., Dore J., Gribble F., Reimann F., et al. (2018). Scfas strongly stimulate pyy production in human enteroendocrine cells. Scient. Rep. 8, 74. 10.1038/s41598-017-18259-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Park S., Oh N., Park J., Kwon M., Seo J., et al. (2021). Oral intake of lactobacillus plantarum l-14 extract alleviates tlr2-and ampk-mediated obesity-associated disorders in high-fat-diet-induced obese c57bl/6j mice. Cell Prolifer. 54, e13039. 10.1111/cpr.13039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Kim J.-,w., Osborne O., Sasik R., Schenk S., Chen A., et al. (2014). Increased adipocyte o2 consumption triggers hif-1α, causing inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Cell 157, 1339–1352. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leija-Martínez J. J., Giacoman-Martínez A., Del-Río-Navarro B. E., Sanchéz-Mu noz F., Hernández-Diazcouder A., Mu noz-Hernández O., et al. (2022). Promoter methylation status of rorc, il17a, and tnfa in peripheral blood leukocytes in adolescents with obesity-related asthma. Heliyon 8, e12316. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E., Bäckhed F., Turnbaugh P., Lozupone C. A., Knight R. D., Gordon J. I. (2005). Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 11070–11075. 10.1073/pnas.0504978102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Yi C.-X., Katiraei S., Kooijman S., Zhou E., Chung C. K., et al. (2018). Butyrate reduces appetite and activates brown adipose tissue via the gut-brain neural circuit. Gut 67, 1269–1279. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Mateer S. W., Hsu A., Goggins B. J., Tay H., Mathe A., et al. (2019). Platelet activating factor receptor regulates colitis-induced pulmonary inflammation through the nlrp3 inflammasome. Mucosal Immunol. 12, 862–873. 10.1038/s41385-019-0163-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yang K., Jia Y., Shi J., Tong Z., Fang D., et al. (2021). Gut microbiome alterations in high-fat-diet-fed mice are associated with antibiotic tolerance. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 874–884. 10.1038/s41564-021-00912-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yang M., Tang L., Wang F., Huang S., Liu S., et al. (2022). Tlr4 regulates rorγt+ regulatory t-cell responses and susceptibility to colon inflammation through interaction with akkermansia muciniphila. Microbiome 10, 1–20. 10.1186/s40168-022-01296-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C. M., Marsland B. J. (2017). Lung homeostasis: influence of age, microbes, and the immune system. Immunity 46, 549–561. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Fan C., Li P., Lu Y., Chang X., Qi K. (2016). Short chain fatty acids prevent high-fat-diet-induced obesity in mice by regulating g protein-coupled receptors and gut microbiota. Scient. Rep. 6, 37589. 10.1038/srep37589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren S. N., Madan J. C., Emond J. A., Morrison H. G., Christensen B. C., Karagas M. R., et al. (2018). Maternal diet during pregnancy is related with the infant stool microbiome in a delivery mode-dependent manner. Microbiome 6, 1–11. 10.1186/s40168-018-0490-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malden S., Gillespie J., Hughes A., Gibson A.-M., Farooq A., Martin A., et al. (2021). obesity in young children and its relationship with diagnosis of asthma, vitamin d deficiency, iron deficiency, specific allergies and flat-footedness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Rev. 22, e13129. 10.1111/obr.13129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamantopoulos M., Frising U. C., Asaoka T., Van Loo G., Lamkanfi M., Wullaert A. (2019). El tor biotype vibrio cholerae activates the caspase-11-independent canonical nlrp3 and pyrin inflammasomes. Front. Immunol. 10, 2463. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowski K. M., Vieira A. T., Ng A., Kranich J., Sierro F., Yu D., et al. (2009). Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor gpr43. Nature 461, 1282–1286. 10.1038/nature08530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell L., Gilkes A., Ashworth M., Rowland V., Harries T. H., Armstrong D., et al. (2021). Association between antibiotics and gut microbiome dysbiosis in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Microbes 13, 1870402. 10.1080/19490976.2020.1870402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghnem D., Leong E., Pinelli M., Marshall J. S., Di Cara F. (2022). Peroxisomes regulate cellular free fatty acids to modulate mast cell tlr2, tlr4, and ige-mediated activation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 856243. 10.3389/fcell.2022.856243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miethe S., Karsonova A., Karaulov A., Renz H. (2020). Obesity and asthma. J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 146, 685–693. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monga N., Sethi G. S., Kondepudi K. K., Naura A. S. (2020). Lipid mediators and asthma: Scope of therapeutics. Biochemical Pharmacology 179, 113925. 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortha A., Chudnovskiy A., Hashimoto D., Bogunovic M., Spencer S. P., Belkaid Y., et al. (2014). Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ilc3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science 343, 1249288. 10.1126/science.1249288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujico J. R., Baccan G. C., Gheorghe A., Díaz L. E., Marcos A. (2013). Changes in gut microbiota due to supplemented fatty acids in diet-induced obese mice. Br. J. Nutr. 110, 711–720. 10.1017/S0007114512005612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R. C., Lai Y., Nolin J. D., Aguillon Prada R. A., Chakrabarti A., Novotny M. V., et al. (2021). Exercise-induced alterations in phospholipid hydrolysis, airway surfactant, and eicosanoids and their role in airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Molec. Physiol. 320, L705–L714. 10.1152/ajplung.00546.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyambuya T. M., Dludla P. V., Mxinwa V., Nkambule B. B. (2020). Obesity-related asthma in children is characterized by t-helper 1 rather than t-helper 2 immune response: A meta-analysis. Ann. Aller. Asthma Immunol. 125, 425–432. 10.1016/j.anai.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic M., Sudar-Milovanovic E., Soskic S., Essack M., Arya S., Stewart A. J., et al. (2021). Leptin and obesity: role and clinical implication. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 585887. 10.3389/fendo.2021.585887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddy W. H. (2017). Breastfeeding, childhood asthma, and allergic disease. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 70, 26–36. 10.1159/000457920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada-Iwabu M., Yamauchi T., Iwabu M., Honma T., Hamagami K.-,i., Matsuda K., et al. (2013). A small-molecule adipor agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature 503, 493–499. 10.1038/nature12656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H., Jian Y., Wang F., Yu S., Guo J., Kan J., et al. (2022). NLRP3 and gut microbiota homeostasis: Progress in research. Cells 11, 3758. 10.3390/cells11233758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S., El Khader I., Casellas F., Lopez Vivancos J., Garcia Cors M., Santiago A., et al. (2014). Short-term effect of antibiotics on human gut microbiota. PLoS ONE 9, e95476. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal M., Perez-Gordo M., Caballero T., Escribese M. M., Lopez Longo M. N., Luengo O., et al. (2018). Microbiome and allergic diseases. Front. Immunol. 9, 1584. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D. M., Sbihi H., Dai D. L., Al Mamun A., Rasali D., Rose C., et al. (2020). Decreasing antibiotic use, the gut microbiota, and asthma incidence in children: evidence from population-based and prospective cohort studies. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 1094–1105. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30052-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini C., Antonioli L., Calderone V., Colucci R., Fornai M., Blandizzi C. (2020). Microbiota-gut-brain axis in health and disease: Is nlrp3 inflammasome at the crossroads of microbiota-gut-brain communications? Progr. Neurobiol. 191, 101806. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periyalil H. A., Wood L. G., Scott H. A., Jensen M. E., Gibson P. G. (2015). Macrophage activation, age and sex effects of immunometabolism in obese asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 45, 388–395. 10.1183/09031936.00080514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters U., Dixon A. E., Forno E. (2018). Obesity and asthma. J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 141, 1169–1179. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu Q., Lin P., Gao P., Wang Z., Guo K., Qin S., et al. (2021). Gut microbiota regulate gut-lung axis inflammatory responses by mediating ilc2 compartmental migration. J. Immunol. 207, 257–267. 10.4049/jimmunol.2001304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabot S., Membrez M., Bruneau A., Gérard P., Harach T., Moser M., et al. (2010). Germ-free c57bl/6j mice are resistant to high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance and have altered cholesterol metabolism. FASEB J. 24, 4948–4959. 10.1096/fj.10.164921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftis E. J., Delday M. I., Cowie P., McCluskey S. M., Singh M. D., Ettorre A., et al. (2018). Bifidobacterium breve MRX0004 protects against airway inflammation in a severe asthma model by suppressing both neutrophil and eosinophil lung infiltration. Sci. Rep. 8, 12024. 10.1038/s41598-018-30448-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rago D., Pedersen C.-E. T., Huang M., Kelly R. S., Gürdeniz G., Brustad N., et al. (2021). Characteristics and mechanisms of a sphingolipid-associated childhood asthma endotype. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 203, 853–863. 10.1164/rccm.202008-3206OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi D., Fraser S., Oh J., Huber A. M., Schulman Y., Bhagtani R. H., et al. (2015). Inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and pulmonary function among obese urban adolescents with asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 191, 149–160. 10.1164/rccm.201409-1587OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddel H. K., Bateman E. D., Becker A., Boulet L.-P., Cruz A. A., Drazen J. M., et al. (2015). A summary of the new gina strategy: a roadmap to asthma control. Eur. Respir. J. 46, 622–639. 10.1183/13993003.00853-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revu S., Wu J., Henkel M., Rittenhouse N., Menk A., Delgoffe G. M., et al. (2018). Il-23 and il-1β drive human th17 cell differentiation and metabolic reprogramming in absence of cd28 costimulation. Cell Rep. 22, 2642–2653. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Angel J., Kaviany P., Rastogi D., Forno E. (2022). Obesity-related asthma in children and adolescents. Lancet Child Adoles. Health. 6, 713–724. 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00185-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-Covián D., Ruas-Madiedo P., Margolles A., Gueimonde M., De Los Reyes-gavilán C. G., Salazar N. (2016). Intestinal short chain fatty acids and their link with diet and human health. Front. Microbiol. 7, 185. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R. C., Manges A. R., Finlay B. B., Prendergast A. J. (2019). The human microbiome and child growth-first 1000 days and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 27, 131–147. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha D., Caldas A., Oliveira L., Bressan J., Hermsdorff H. (2016). Saturated fatty acids trigger tlr4-mediated inflammatory response. Atherosclerosis 244, 211–215. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roduit C., Frei R., Ferstl R., Loeliger S., Westermann P., Rhyner C., et al. (2019). High levels of butyrate and propionate in early life are associated with protection against atopy. Allergy 74, 799–809. 10.1111/all.13660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist N. A., Richards M., Ferber J. R., Li D.-K., Ryu S. Y., Burkin H., et al. (2023). Prepregnancy body mass index and risk of childhood asthma. Allergy 78, 1234–1244. 10.1111/all.15598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutayisire E., Huang K., Liu Y., Tao F. (2016). The mode of delivery affects the diversity and colonization pattern of the gut microbiota during the first year of infants' life: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 16, 1–12. 10.1186/s12876-016-0498-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saari A., Virta L. J., Sankilampi U., Dunkel L., Saxen H. (2015). Antibiotic exposure in infancy and risk of being overweight in the first 24 months of life. Pediatrics 135, 617–626. 10.1542/peds.2014-3407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuchiwal S. K., Boyce J. A. (2018). Role of lipid mediators and control of lymphocyte responses in type 2 immunopathology. J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 141, 1182–1190. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J. H., Lee-Sarwar K. A., Sordillo J. E., Lange N. E., Zhou Y., O'Connor G. T., et al. (2018). Diet during pregnancy and infancy and the infant intestinal microbiome. J. Pediatr. 203, 47–54. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijs M. J., Willart M. A., Vergote K., Gras D., Deswarte K., Ege M. J., et al. (2015). Farm dust and endotoxin protect against allergy through a20 induction in lung epithelial cells. Science 349, 1106–1110. 10.1126/science.aac6623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepahi A., Liu Q., Friesen L., Kim C. H. (2021). Dietary fiber metabolites regulate innate lymphoid cell responses. Mucosal Immunol. 14, 317–330. 10.1038/s41385-020-0312-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N., Akkoyunlu M., Rabin R. (2018). Macrophages common culprit in obesity and asthma. Allergy 73, 1196–1205. 10.1111/all.13369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N., Li T. (2018). Regulation of nlrp3 inflammasome by phosphorylation. Front. Immunol. 9, 2305. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriani A., Stabile H., Gismondi A., Santoni A., Bernardini G. (2018). Chemokine regulation of innate lymphoid cell tissue distribution and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 42, 47–55. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger B. (2021). T cell subsets and environmental factors in citrobacter rodentium infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 63, 92–97. 10.1016/j.mib.2021.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze E., Bhalla A., Nair P. (2020). Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for non-t2 asthma. Allergy 75, 311–325. 10.1111/all.13985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J., Xu L., Zeng Y., Gong F. (2021). Effect of gut microbiota on lps-induced acute lung injury by regulating the tlr4/nf-kb signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 91, 107272. 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis K. R., Romero R., Winters A. D., Greenberg J. M., Gomez-Lopez N., Alhousseini A., et al. (2019). Does the human placenta delivered at term have a microbiota? results of cultivation, quantitative real-time pcr, 16s rrna gene sequencing, and metagenomics. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 220, 267. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhurst G., Heffron H., Lam Y. S., Parker H. E., Habib A. M., Diakogiannaki E., et al. (2012). Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the g-protein-coupled receptor ffar2. Diabetes 61, 364–371. 10.2337/db11-1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun H. M., Bridgman S. L., Chari R., Field C. J., Guttman D. S., Becker A. B., et al. (2018). Roles of birth mode and infant gut microbiota in intergenerational transmission of overweight and obesity from mother to offspring. JAMA Pediatr. 172, 368–377. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Bäckhed F., Fulton L., Gordon J. I. (2008). Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 3, 213–223. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Ley R. E., Mahowald M. A., Magrini V., Mardis E. R., Gordon J. I. (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444, 1027–1031. 10.1038/nature05414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Ridaura V. K., Faith J. J., Rey F. E., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2009). The effect of diet on the human gut microbiome: a metagenomic analysis in humanized gnotobiotic mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 1, 6ra14. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez M. T. (2018). Altered gut microbiota: a link between diet and the metabolic syndrome. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disor. 16, 321–328. 10.1089/met.2017.0163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivier E., Artis D., Colonna M., Diefenbach A., Di Santo J. P., Eberl G., et al. (2018). Innate lymphoid cells: 10 years on. Cell 174, 1054–1066. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Wu L., Chen J., Dong L., Chen C., Wen Z., et al. (2021). Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: Mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transd. Target. Ther. 6, 94. 10.1038/s41392-020-00443-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Hauenstein A. V. (2020). The nlrp3 inflammasome: Mechanism of action, role in disease and therapies. Molec. Aspect. Med. 76, 100889. 10.1016/j.mam.2020.100889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]