Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Diagnosis of pneumonia is challenging in critically ill, intubated patients due to limited diagnostic modalities. Endotracheal aspirate (EA) cultures are standard of care in many ICUs; however, frequent EA contamination leads to unnecessary antibiotic use. Nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL) obtains sterile, alveolar cultures, avoiding contamination. However, paired NBBL and EA sampling in the setting of a lack of gold standard for airway culture is a novel approach to improve culture accuracy and limit antibiotic use in the critically ill patients.

DESIGN:

We designed a pilot study to test respiratory culture accuracy between EA and NBBL. Adult, intubated patients with suspected pneumonia received concurrent EA and NBBL cultures by registered respiratory therapists. Respiratory culture microbiology, cell counts, and antibiotic prescribing practices were examined.

SETTING:

We performed a prospective pilot study at the Cleveland Clinic Main Campus Medical ICU in Cleveland, Ohio for 22 months from May 2021 through March 2023.

PATIENTS OR SUBJECTS:

Three hundred forty mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia were screened. Two hundred fifty-seven patients were excluded for severe hypoxia (Fio2 ≥ 80% or positive end-expiratory pressure ≥ 12 cm H2O), coagulopathy, platelets less than 50,000, hemodynamic instability as determined by the treating team, and COVID-19 infection to prevent aerosolization of the virus.

INTERVENTIONS:

All 83 eligible patients were enrolled and underwent concurrent EA and NBBL.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

More EA cultures (42.17%) were positive than concurrent NBBL cultures (26.51%, p = 0.049), indicating EA contamination. The odds of EA contamination increased by eight-fold 24 hours after intubation. EA was also more likely to be contaminated with oral flora when compared with NBBL cultures. There was a trend toward decreased antibiotic use in patients with positive EA cultures if paired with a negative NBBL culture. Alveolar immune cell populations were recovered from NBBL samples, indicating successful alveolar sampling. There were no major complications from NBBL.

CONCLUSIONS:

NBBL is more accurate than EA for respiratory cultures in critically ill, intubated patients. NBBL provides a safe and effective technique to sample the alveolar space for both clinical and research purposes.

KEY POINTS

Question: Will nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL) be a better method to obtain respiratory cultures than endotracheal aspirate (EA)?

Findings: In this pilot study, we found that the NBBL was more accurate than EA for identifying a respiratory infection in critically ill, intubated patients. These findings indicate that NBBL may be a safe and effective technique to sample the alveolar space for both clinical and research purposes.

Meaning: Besides practitioners should consider obtaining NBBL, especially in patients that are intubated for more than 24 hours, who have a higher risk of endotracheal tube contamination.

Pneumonia is a common and deadly disease in the ICU. Accurate diagnosis and timely initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy reduce mortality from pneumonia (1, 2). However, diagnosis of pneumonia in the ICU is challenging due to limitations of diagnostic modalities (i.e., radiology) and lack of precise biomarkers to distinguish between infiltrates due to pulmonary edema and infectious etiologies. International guidelines recommend distal quantitative respiratory cultures as standard of care for suspected pneumonia (3). However, in the United States, diagnostic guidelines for pneumonia in intubated patients come from the 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines on ventilator-associated pneumonia by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS), which recommend endotracheal aspirate (EA) as the first-line respiratory culture technique, based on low-quality evidence (4). However, there are numerous problems associated with EA cultures in diagnosing pneumonia, including but not limited: 1) to increased risk of contamination, 2) lack of quantitative cultures, and 3) reduced diagnostic yield (5).

EAs provide a microbiologic sample near the distal tip of the endotracheal tube, not from the alveolar space, and therefore a positive EA culture does not always indicate pneumonia (6). The literature suggests that nearly all endotracheal tubes become colonized with bacteria as early as 24 hours after intubation (7, 8). Additionally, EA cultures are semiquantitative, so there is no validated diagnostic threshold below which a positive culture is considered clinically significant. Given the high mortality associated with untreated pneumonia, many patients with contaminated EA cultures receive antibiotic therapy. Emerging evidence suggests that routine use of EA to diagnose pneumonia in intubated patients is associated with increased antibiotic prescribing, supporting this concern (9, 10). Unnecessary antibiotic use has several well-known consequences, including nephrotoxicity, Clostridioides difficile colitis, and antibiotic resistance (11).

Invasive lower respiratory sampling with either nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL) or conventional fiberoptic bronchoscopy to diagnose pneumonia in intubated patients may reduce the risk of bacterial contamination associated with EA (12). NBBL is a minimally invasive technique that has been used to sample the lower airways and alveoli sterilely. NBBL provides several advantages over EA and fiberoptic bronchoscopy. NBBL provides sterile, quantitative cultures with a yield similar to fiberoptic bronchoscopy at a lower cost (13–15). NBBL is safe and has been performed in critically ill patients for both clinical and research use (16–18). Despite these advantages, NBBL is currently not recommended for routine pneumonia diagnosis given the limited and conflicting data to support its standard use.

Given the safety and decreased theoretical risk of yielding colonizing organisms, we sought to explore the comparison of NBBL to EA to improve respiratory culture accuracy and reduce the use of unnecessary antibiotics in critically ill patients. We hypothesized that respiratory cultures from NBBL would have less contamination compared with EA, leading to decreased unnecessary antibiotic use in critically ill patients. To test our hypothesis, we designed a pilot study comparing concurrent EA and NBBL cultures in mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

Study Design

We performed a prospective pilot study at the Cleveland Clinic Main Campus Medical ICU in Cleveland, Ohio for 22 months from May 2021 through March 2023. Mechanically ventilated, COVID-19 negative, adult patients (≥ 18 yr old) with clinically suspected pneumonia (fever, leukocytosis, infiltrate on chest imaging, and/or worsening oxygenation) underwent a concurrent EA and NBBL by registered respiratory therapists (RRTs). Patient characteristics were collected. EA and NBBL culture results were compared and determined to be concordant or discordant based on positive bacterial growth and colony-forming unit (CFU) quantification. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Cleveland Clinic institutional review board (number 21-413, approval date: May 13, 2022, Study Title: The Role of Non-Bronchoscopic Bronchoalveolar Lavage Culture on Antimicrobial Practice Patterns and Preclinical Evaluation of the Role of TRPV4). Procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional or regional) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Patients

Three hundred forty mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia were screened. Two hundred fifty-seven patients were excluded for severe hypoxia (Fio2 ≥ 80% or positive end-expiratory pressure ≥ 12 cm H2O), coagulopathy, platelets less than 50,000, hemodynamic instability as determined by the treating team, and COVID-19 infection to prevent aerosolization of the virus. If patient was on anticoagulation, the medication was held 2 hours before NBBL. All 83 eligible patients were enrolled and underwent concurrent EA and NBBL (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for inclusion/exclusion for enrollment and photograph of mini-BAL catheter used for nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL). A, There were a total of 340 patients from the ICU with suspected of pneumonia, based on clinical criteria (new fever, sputum, infiltrate on chest imaging). Patients were excluded for low platelets, coagulopathy, high ventilator settings, and hemodynamic instability. Ultimately, 83 patients were enrolled and underwent concurrent endotracheal aspirate (EA) and NBBL cultures. B, Photograph of Avanos Ballard Mini-BAL catheter used for the NBBLs. PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PEEP = positive end-expiratory pressure.

EA and NBBL Procedure

EA was performed by the RRT according to a standard technique at the Cleveland Clinic. A Ballard nonbronchoscopic mini-BAL catheter (Avanos, 5405 Windward Pkwy, Alpharetta, GA 30004, USA) (NBBL) was performed via the RRT based on previously published recommendations (18). Briefly, the RRT blindly introduced a sterile NBBL catheter through the endotracheal tube, guiding it to the right or left main stem bronchus. Once the catheter was wedged per Cleveland Clinic approved protocol, the RRT instilled three aliquots of 20 mL of saline with withdrawal of each aliquot after instillation for a total of 60 mL. Semiquantitative cultures were performed on EA samples and quantitative cultures were performed on NBBL samples, per standard practice of the Cleveland Clinic microbiology laboratory.

Data

The following data were collected for analysis: demographic data including age, sex, comorbidities, variables of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III (APACHE III) score, respiratory culture microbiology, NBBL cell count with differential, duration of antibiotics and antibiotic agent, and hospital disposition and mortality. EA cultures were considered positive if there was any microbial growth other than oral flora. NBBL cultures were considered positive if there was microbial growth greater than or equal to 104 CFUs other than oral flora, as recommended by IDSA/ATS guidelines (4). Oral flora was considered present and not further speciated if there was growth of oral flora organisms, as determined by laboratory medicine in the EA or NBBL culture. All laboratory results were available to the bedside clinician in the electronic health record.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was to compare rates of culture positivity between EA and NBBL. Secondary outcomes were: 1) to compare rates of oral flora contamination between EA and NBBL, 2) perform a subgroup analysis of concordant versus discordant EA and NBBL samples, and 3) confirm NBBL alveolar sampling with analysis of immune cell populations. For our subgroup analysis, antibiotic change and duration were compared between those with concordant negative EA and NBBL cultures (no infection), positive EA and NBBL cultures (true infection), and those with EA positive and NBBL negative cultures (suspected EA contamination) to determine if there were differences in antibiotic prescribing practices. Antibiotic change was defined as any change in antibiotic therapy after respiratory culture, including cessation. Antibiotic cessation was defined as discontinuation of antibiotics within 72 hours after respiratory culture.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic variables were collected and described using sample mean with sd or number with proportion, as appropriate. Fisher exact test determined differences in culture positivity and oral flora between EA and NBBL. Comparison of binary variables, such as antibiotic change or cessation, between concordant and discordant groups was performed using Pearson’s chi-square test. Continuous variables, such as age, APACHE III score, endotracheal tube duration, and antibiotic duration, were compared between negative EA and NBBL, positive EA and NBBL, and positive EA and negative NBBL culture groups using one-way analysis of variance or nonparametric test, as appropriate. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 8.0.0, for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, www.graphpad.com). The level of significance was set at p value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Characteristics

A total of 340 patients were screened and 83 patients were successfully enrolled in the study (Fig. 1). Patients were assigned to one of three groups based on EA and NBBL culture results: 1) negative EA and NBBL (no infection), 2) positive EA and NBBL (true infection), and 3) positive EA and negative NBBL (suspected EA contamination). The average age of the population was 58.53 ± 14.43 years with 49.4% female patients. The average APACHE III score was 93.66 ± 31.77. Comorbidities of the patients included diabetes (30.1%), liver failure (16.9%), immune suppression (15.7%), and malignancy (9.6%). The in-hospital mortality was 25.3%. The average age of patients with negative EA and NBBL cultures was 54.36 ± 13.98 which was significantly younger than patients with either positive EA and NBBL (63.62 ± 11.92) or positive EA and negative NBBL (64.71 ± 16.01, p = 0.0095). Otherwise, there were no differences in demographics, APACHE III scores, and comorbidities, with the exception of liver failure, among patients with concordant versus discordant EA and NBBL culture results. Similarly, there were comparable mortality rates across all groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Total (N = 83) | Negative EA and NBBL (N = 47) | Positive EA and NBBL (N = 21) | Positive EA, Negative NBBL (N = 14) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± sd) | 58.53 ± 14.43 | 54.36 ± 13.83 | 63.62 ± 11.92 | 64.71 ± 16.01 | 0.0095 |

| Sex % female (n) | 49.4% (41) | 59.6% (28) | 42.6% (9) | 28.6% (4) | 0.0943 |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III (mean ± sd) | 93.66 ± 31.77 | 93 ± 28.6 | 99 ± 28.34 | 91.5 ± 43.7 | 0.7457 |

| Diabetes (n) | 30.1% (25) | 36.2% (17) | 23.8% (5) | 21.4% (3) | 0.4274 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n) | 27.7% (23) | 29.8% (14) | 14.3% (3) | 42.9% (6) | 0.1684 |

| Liver failure (n) | 16.9% (14) | 27.7% (13) | 4.8% (1) | 0% (0) | 0.012 |

| Immune suppression (n) | 15.7% (13) | 10.6% (5) | 28.6% (6) | 14.3% (2) | 0.1712 |

| Malignancy (n) | 9.6% (8) | 12.8% (6) | 9.5% (2) | 0% (0) | 0.3682 |

| Endotracheal tube days (mean ± sd) | 6.024 ± 7.128 | 4.340 ± 4.944 | 8.048 ± 8.599 | 9.071 ± 9.515 | 0.0509 |

| In-hospital mortality (n) | 25.3% (21) | 23.4% (11) | 28.6% (6) | 28.6% (4) | 0.8689 |

EA = endotracheal aspirate, NBBL = nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage.

Patients were broken into three groups based on EA and NBBL culture results: negative EA and NBBL (no infection), positive EA and NBBL (true infection), and positive EA, negative NBBL (suspected contamination).

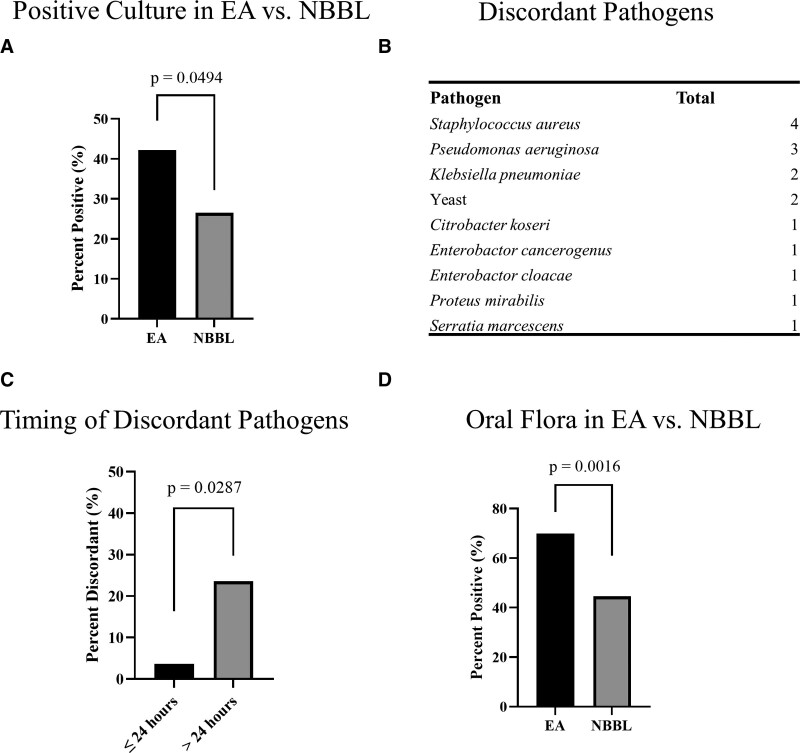

Microbiologic Discrepancies Between EA and NBBL With Evidence of Increased Contamination in EA Cultures

To first determine if there were respiratory culture differences between EA and NBBL, we obtained concurrent EA and NBBL from all enrolled patients. We found 35 positive EA cultures (42.17%) and 22 positive NBBL cultures (26.51%, p = 0.049) (Fig. 2A). Upon comparing EA and NBBL cultures, we found a total of 15 discordant cultures. Fourteen of 15 of those discordant cultures had a positive EA culture and a negative NBBL culture, which were considered our main discordant group. Of those 14 discordant EA cultures, the following organisms grew from the EA: Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, yeast (specific organism not specified), Citrobacter koseri, Enterobactor species, Proteus mirabilis, and Serratia marcescens (Fig. 2B). The one discordant culture with a positive NBBL and a negative EA grew Streptococcus intermedius in a patient with necrotizing pneumonia. In this case, the EA likely failed to identify the cause of this lower respiratory tract infection (19).

Figure 2.

Microbiologic data comparing endotracheal aspirate (EA) and nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL). EA had significantly more positive cultures when compared with concurrent NBBL cultures (A). List of discordant pathogens from positive EA and negative NBBL (B). EA contamination increased from 3.7% to 23.6%, a more than eight-fold increase, 24 hours after intubation (C). There is a trend toward increased EA culture contamination and endotracheal tube (ETT) duration (D). EA had significantly more oral flora contamination when compared with concurrent NBBL cultures (E).

There was a trend toward longer duration of endotracheal intubation in patients with positive EA and NBBL (8.048 ± 8.599 d) and positive EA and negative NBBL (9.071 ± 9.515 d), compared with negative EA and NBBL (4.340 ± 4.944 d) (Table 1). EA culture contamination with endotracheal tube colonizers increased from 3.7% within the first 24 hours of endotracheal intubation to 23.6% after the first 24 hours (p = 0.0087), a more than six-fold increase (Fig. 2C). The likelihood of EA contamination with endotracheal tube colonizers continues to increase throughout the duration of intubation (not shown).

Lastly, we sought to stratify the presence of oral flora between EA and NBBL cultures. We found that 58 EA cultures (69.9%) were contaminated with oral flora as compared with only 37 NBBL cultures (44.6%) (p = 0.0016) (Fig. 2D). These data show that EA and NBBL have significantly discordant cultures and EA culture positivity with colonizers usually occurs after 24 hours. In addition, EA cultures more frequently are colonized with oral flora compared with NBBL.

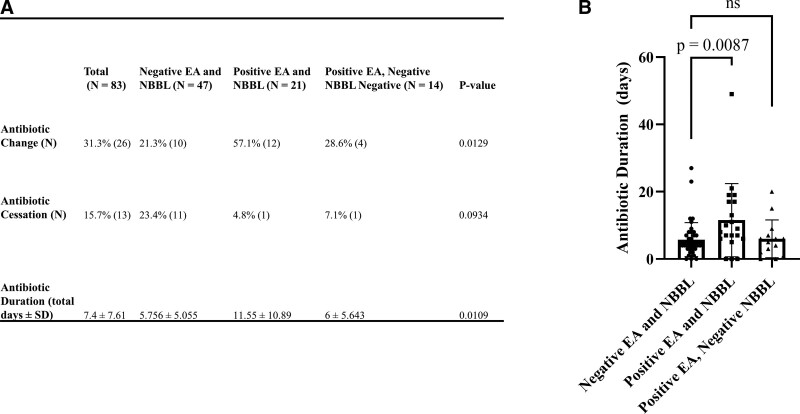

Changes in Antibiotic Practices After EA and NBBL Culture

Next, we assessed if antibiotic practices in the MICU changed based on EA and NBBL culture results. Overall, 26 patients (31.3%) had antibiotic change, 13 patients (15.6%) had antibiotic cessation, and the mean duration of antibiotics after respiratory culture was 7.4 ± 7.61 days (Fig. 3A). Among patients with positive EA and NBBL cultures, 12 patients (57.1%) had antibiotic change, 1 patient (4.8%) had antibiotic cessation, and the mean duration of antibiotics after respiratory culture was 11.55 days ± 10.89 (Fig. 3A). Among patients with negative EA and NBBL cultures, 10 (21.3%) patients had antibiotic change, 11 (23.4%) patients had antibiotic cessation, and the mean duration of antibiotics after respiratory culture was significantly shorter than those with positive EA and NBBL cultures at 5.76 days ± 5.06 (p = 0.0087) (Fig. 3A). Among patients with discordant cultures (positive EA and negative NBBL) 4 patients (28.6%) had antibiotic change, 1 patient (7.1%) had antibiotic cessation, and the mean duration of antibiotics after respiratory culture was 6 days ± 5.64. This closely resembles the antibiotic duration seen with negative EA and NBBL cultures (Fig. 3B). Collectively, these data suggest that antibiotic practices change with the availability of NBBL culture results.

Figure 3.

Antibiotic use after respiratory culture. Antibiotic use was compared between the three patient groups, including antibiotic change, cessation, and overall duration (A). Patients with positive endotracheal aspirate (EA) and negative nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL) had an average antibiotic duration similar to that seen with negative EA and NBBL (B).

Major and Minor Complications Observed With NBBL

There were only 2 patients (2.4%) with bloody secretions in our entire cohort that were all self-limiting. There were no major complications from NBBL in our cohort (Supplement Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B275).

Evidence of Alveolar Immune Cell Populations From NBBL

To confirm that NBBL provides respiratory culture samples from the alveolar space, we quantified nucleated cell populations from the NBBL sample. We found the presence of several alveolar immune cell populations, including: neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes, lymphocytes, and eosinophils (Fig. 4). These data show that the NBBL samples the alveolar space similar to that of a fiberoptic bronchoscopy as published (13–15).

Figure 4.

Evidence of alveolar immune cell populations from nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL). Of the NBBLs with cell count performed, all demonstrated alveolar immune cells, confirming that NBBL is sampling the alveolar space (A). Composition of the NBBL cells (B).

DISCUSSION

Accurate diagnosis of pneumonia in critically ill patients is challenging, in part due to frequent respiratory culture contamination, leading to unnecessary antibiotic use. We show herein that lower respiratory tract culture with NBBL: 1) is less frequently contaminated than EA, 2) may decrease unnecessary antibiotic use, 3) has minimal complications comparable to what the literature reports for fiberoptic bronchoscopy, and 4) samples the alveolar space effectively (20, 21). The literature on the utility of lower respiratory culture has been mixed with other groups confirming our findings (22). We hope our work will bridge the gap between clinical and research use of NBBL by showing relevance to bedside clinical practice and be a noninvasive, safe, obtainable sample of the alveolar space to potentially investigate mechanisms of lung injury and repair in the critically ill patients.

Our data in this pilot study highlight that EA cultures are more frequently positive than NBBL cultures. We suspect that the increased number of positive EA cultures is due to contamination by endotracheal tube colonizers rather than true infection for several reasons: 1) EA cultures are obtained from a nonsterile site, near the distal tip of the endotracheal tube, 2) although several of these organisms recovered from the discordant respiratory cultures (positive EA, negative NBBL) can be pathogens in the right context, they also have been shown to be endotracheal tube colonizers, including S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and K. pneumoniae (23), and 3) Duration of endotracheal intubation increased the likelihood of EA contamination with endotracheal tube colonizers after 24 hours of endotracheal intubation. As shown by us and others, duration of endotracheal intubation is a risk factor for both the development of pneumonia and endotracheal tube colonization (7, 8, 24).

In terms of antibiotic stewardship, we found a trend toward reduced antibiotic use in patients with a positive EA if paired with a negative NBBL. This suggests that NBBL is a possible tool to reduce antibiotic use in ICU patients with suspected pneumonia. Critics of NBBL point to the lack of consistent evidence that NBBL improves mortality, reduces antibiotic use, or improves length of stay in critically ill patients (25). This skepticism is based on negative randomized controlled trials from the 1990s to early 2000s (26–30). However, these trials were conducted before widespread awareness of the importance of antibiotic stewardship, which has changed antibiotic prescribing practices (31). The challenge remains in balancing identifying the correct organism to ensure effective antibiotics while avoiding false-positive respiratory cultures which lead to unnecessary and harmful antibiotic use. As further data support early, broad-spectrum antibiotic use (< 1 hr), providers broadly cover organisms that may not be the culprit (1, 2). Unnecessary continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics contributes to emerging antibiotic resistance, secondary infections including C. difficile infection, and mortality in our critically ill population (11).

In many ICUs, NBBL is performed by RRTs, which has advantages and disadvantages. Advantages of NBBLs being performed by RRTs include less cost and physician time, as compared with fiberoptic bronchoscopy. In addition, NBBL can be performed safely and efficiently by RRTs, with adequate RRT training and staffing. Complications related to NBBL are rarely reported in the literature or in our work (Supplement Fig. 1, http://links.lww.com/CCX/B275) (16–18). Disadvantages of NBBLs being performed by RRTs include the need for comprehensive training and periodic simulation training to prevent complications and NBBL culture contamination. RRT understaffing and patient care workload may also be potential barriers to routine NBBLs (32).

In addition to clinical applications, NBBL also has many research applications. Obtaining remnant samples from a clinical procedure performed routinely, such as NBBL, has the potential to further our knowledge of molecular pathways that drive disease. Many biomarker studies in critically ill patients have used serum biomarkers due to concerns over the safety and cost of obtaining alveolar samples (33–35). We have demonstrated that NBBL reaches the alveolar space and can provide researchers with alveolar immune cell populations from our NBBL cell counts (Fig. 4). Other groups have also published the utility of NBBL alveolar samples to study biological pathways of lung injury (16).

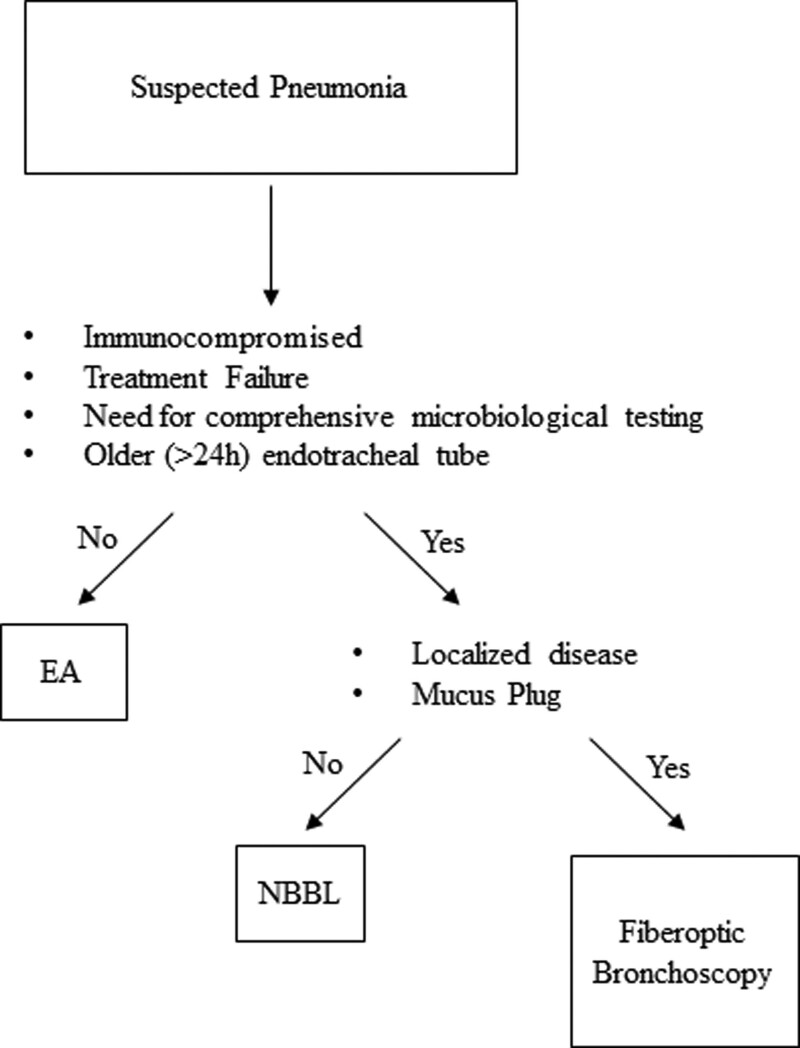

Many studies highlight cost differences between NBBL and fiberoptic bronchoscopy (36). At the Cleveland Clinic, the cost of NBBL is ~$50 and fiberoptic bronchoscopy is $100–300. However, there may be occasions where traditional bronchoscopy has advantages over NBBL as outlined in the following algorithm (Fig. 5). In the setting: 1) of an immunocompromised patient, 2) treatment failure, 3) need for comprehensive microbiologic testing, or 4) older (> 24 hr) endotracheal tube, we recommend an NBBL if there is diffuse infiltrative disease and no concern for mucous plug. For focal infiltrates or suspected mucus plugging, we recommend fiberoptic bronchoscopy.

Figure 5.

Proposed algorithm of obtaining respiratory cultures in the setting of suspected pneumonia in the critically ill patients. In ICU patients: 1) who are immunocompromised, 2) who failed antibiotic treatment, 3) who need extensive microbiologic testing, or 4) who are intubated greater than 24 hours, we suggest nonbronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage (NBBL). For those with localized disease or mucus plugging, we recommend fiberoptic bronchoscopy. EA = endotracheal aspirate.

Our study strengthens the literature by furthering our understanding of the appropriate timing and narrow use of EA and effectiveness of NBBL. However, there are many limitations. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard diagnostic test for bacterial pneumonia (37, 38). Given the safety of antibiotic discontinuation in patients with negative lower respiratory cultures and wide clinical availability of NBBL, we think that comparison of NBBL to EA is clinically valuable (3, 4, 39). Despite the prospective nature of the study, there are still many confounding variables. One important confounder is that despite a negative respiratory culture, the critically ill patient may have remained on antibiotics for nonrespiratory infections. Additionally, practice variability on use of sterile catheters for obtaining EA may have skewed some of the results. In addition, RRTs were not performing NBBLs regularly in the MICU before this pilot study, therefore the cultures performed later in the study might more accurately reflect the lower respiratory tract. Finally, our study was overall impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In conclusion, in our head-to-head comparison of EA and NBBL, we find that NBBL is a safe and effective tool for diagnosing pneumonia and tailoring antibiotics in critically ill patients. Our data support that NBBL more accurately identifies respiratory pathogens compared with EA. NBBL may be associated with decreased antibiotic use in critically ill patients. However, more data are needed to determine timing and use of NBBL compared with EA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL155064 (Dr. Scheraga), R35GM149240 (Dr. Vachharajani), and the SMARRT T32 which is funded by the National Institutes of Heart, Lung, and Blood grant, T32HL-155005. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Drs. Jeng and Orsini are co-first authors and equally contributing to the writing of this work.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu VX, Fielding-Singh V, Greene JD, et al. : The timing of early antibiotics and hospital mortality in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 196:856–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. : Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:2235–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres A, Niederman MS, Chastre J, et al. : International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)/ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) of the European Respiratory Society (ERS), European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and Asociación Latinoamericana del Tórax (ALAT). Eur Respir J 2017; 50:1700582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. : Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:e61–e111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin-Loeches I, Chastre J, Wunderink RG: Bronchoscopy for diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2023; 49:79–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholte JB, van Dessel HA, Linssen CF, et al. : Endotracheal aspirate and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis: Interchangeable diagnostic modalities in suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia? J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:3597–3604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danin PE, Girou E, Legrand P, et al. : Description and microbiology of endotracheal tube biofilm in mechanically ventilated subjects. Respir Care 2015; 60:21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gil-Perotin S, Ramirez P, Marti V, et al. : Implications of endotracheal tube biofilm in ventilator-associated pneumonia response: A state of concept. Crit Care 2012; 16:R93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prinzi A, Parker SK, Thurm C, et al. : Association of endotracheal aspirate culture variability and antibiotic use in mechanically ventilated pediatric patients. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2140378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prinzi AM, Wattier RL, Curtis DJ, et al. : Impact of organism reporting from endotracheal aspirate cultures on antimicrobial prescribing practices in mechanically ventilated pediatric patients. J Clin Microbiol 2022; 60:e0093022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, et al. : Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med 2017; 177:1308–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. : Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill adult patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:1170–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khilnani GC, Arafath TK, Hadda V, et al. : Comparison of bronchoscopic and non-bronchoscopic techniques for diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia. Indian J Crit Care Med 2011; 15:16–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal A, Malviya D, Harjai M, et al. : Comparative evaluation of the role of nonbronchoscopic and bronchoscopic techniques of distal airway sampling for the diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Anesth Essays Res 2020; 14:434–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afolabi-Brown O, Marcus M, Speciale P, et al. : Bronchoscopic and nonbronchoscopic methods of airway culturing in tracheostomized children. Respir Care 2014; 59:582–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walter JM, Helmin KA, Abdala-Valencia H, et al. : Multidimensional assessment of alveolar T cells in critically ill patients. JCI Insight 2018; 3:e123287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burmester M, Mok Q: How safe is non-bronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage in critically ill mechanically ventilated children? Intensive Care Med 2001; 27:716–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonvento BV, Rooney JA, Columb MO, et al. : Non-directed bronchial lavage is a safe method for sampling the respiratory tract in critically ill patient. J Intensive Care Soc 2019; 20:237–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noguchi S, Yatera K, Kawanami T, et al. : Pneumonia and empyema caused by Streptococcus intermedius that shows the diagnostic importance of evaluating the microbiota in the lower respiratory tract. Intern Med 2014; 53:47–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bo L, Shi L, Jin F, et al. : The hemorrhage risk of patients undergoing bronchoscopic examinations or treatments. Am J Transl Res 2021; 13:9175–9181 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soni KD, Samanta S, Aggarwal R, et al. : Pneumothorax following flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy: A rare occurrence. Saudi J Anaesth 2014; 8:S124–S125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujitani S, Cohen-Melamed MH, Tuttle RP, et al. : Comparison of semi-quantitative endotracheal aspirates to quantitative non-bronchoscopic bronchoalveolar lavage in diagnosing ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care 2009; 54:1453–1461 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedland DR, Rothschild MA, Delgado M, et al. : Bacterial colonization of endotracheal tubes in intubated neonates. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001; 127:525–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papazian L, Klompas M, Luyt CE: Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: A narrative review. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46:888–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berton DC, Kalil AC, Teixeira PJ: Quantitative versus qualitative cultures of respiratory secretions for clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD006482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solé Violán J, Fernández JA, Benítez AB, et al. : Impact of quantitative invasive diagnostic techniques in the management and outcome of mechanically ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2000; 28:2737–2741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Nieto JM, Torres A, Garcia-Cordoba F, et al. : Impact of invasive and noninvasive quantitative culture sampling on outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia: A pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157:371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz M, Torres A, Ewig S, et al. : Noninvasive versus invasive microbial investigation in ventilator-associated pneumonia: Evaluation of outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162:119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fagon JY, Chastre J, Wolff M, et al. : Invasive and noninvasive strategies for management of suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.A randomized trial of diagnostic techniques for ventilator-associated pneumonia. The Canadian Critical Care Trials Group: N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2619–2630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad NJ, Althemery AU, Haseeb A, et al. : Inclining trend of the researchers interest in antimicrobial stewardship: A systematic review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2020; 12:11–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danzy JN, Gilmore TW, Smith SG, et al. : A pre-pandemic evaluation of the state of staffing and future of the respiratory care profession: Perceptions of Louisiana respiratory therapists. Respir Care 2022; 67:1254–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han S, Mallampalli RK: The acute respiratory distress syndrome: From mechanism to translation. J Immunol 2015; 194:855–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamond M, Peniston Feliciano HL, Sanghavi D, Mahapatra S. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. StatPearls. Treasure Island FL, StatPearls Publishing, 2021 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spadaro S, Park M, Turrini C, et al. : Biomarkers for acute respiratory distress syndrome and prospects for personalised medicine. J Inflamm 2019; 16:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tasbakan MS, Gurgun A, Basoglu OK, et al. : Comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage and mini-bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Respiration 2011; 81:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qazi S, Were W: Improving diagnosis of childhood pneumonia. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:372–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grigg J: Seeking an accurate, point-of-contact diagnostic test for bacterial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193:353–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raman K, Nailor MD, Nicolau DP, et al. : Early antibiotic discontinuation in patients with clinically suspected ventilator-associated pneumonia and negative quantitative bronchoscopy cultures. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:1656–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.