Abstract

Adjectives (e.g., hungry) are an important part of language, but have been little studied in individuals with impaired language. Adjectives are used in two different ways in English: attributively, to modify a noun (the hungry dog); or predicatively, after a verb (the dog is hungry). Attributive adjectives have a more complex grammatical structure than predicative adjectives, and may therefore be particularly prone to disruption in individuals with grammatical impairments. We investigated adjective production in three subtypes of primary progressive aphasia (PPA: agrammatic, semantic, logopenic), as well as in agrammatic stroke aphasia and a group of healthy control participants. Participants produced narratives based on picture books, and we coded every adjective they produced for its syntactic structure. Compared to healthy controls, the two agrammatic groups, but not the other two patient groups, produced significantly fewer attributive adjectives per sentence. All four patient groups were similar to controls for their rate of predicative adjective production. In addition, we found a significant correlation in the agrammatic PPA participants between their rate of producing attributive adjective and impaired production of sentences with complex syntactic structure (subject cleft sentences like It was the boy that chased the girl); no such correlation was found for predicative adjectives. Irrespective of structure, we examined the lexical characteristics of the adjectives that were produced, including length, frequency, semantic diversity and neighborhood density. Overall, the lexical characteristics of the produced adjectives were largely consistent with the language profile of each group. In sum, the results suggest that attributive adjectives present a particular challenge for individuals with agrammatic language production, and add a new dimension to the description of agrammatism. Our results further suggest that attributive adjectives may be a fruitful target for improved treatment and recovery of agrammatic language.

Keywords: aphasia, stroke, primary progressive aphasia, adjectives, agrammatism, narrative production

1.0. Introduction

Adjectives (e.g., hungry) are an important part of language, but have been largely unstudied in adults with impaired language. Adjectives, together with nouns, verbs, and adverbs, comprise a category of open-class words, which are the principal elements in a sentence that convey its meaning. Production of open-class words is often impaired in acquired neurogenic communication disorders, though the evidence for these impairments has been focused almost exclusively on nouns and verbs. Here we examine adjective production in primary progressive aphasia (PPA), a syndrome that affects language production and comprehension, caused by an underlying neurodegenerative disease (M.-M. Mesulam, 2007).

Impaired production of nouns and verbs is found in all PPA variants, though with different patterns across subtypes in keeping with the underlying impairment in each. Individuals with agrammatic PPA (PPA-G) have greater impairments for verbs than nouns (Cotelli et al., 2006; Hillis et al., 2004, 2006; Marcotte et al., 2014; Silveri & Ciccarelli, 2007; Thompson et al., 2012; Thompson & Mack, 2014; Wang et al., 2022), reflecting an underlying grammatical deficit as seen in agrammatic stroke aphasia (Thompson & Mack, 2014). Because verbs are essential for the formation of clauses and sentences (Baker, 2003), verb production impairments preclude grammatical sentence production. For individuals with semantic PPA (PPA-S), studies show that noun (object) naming is severely impaired (Auclair et al., 2020; Marcotte et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2010), often accompanied by verb production difficulty (Auclair et al., 2020; Hillis et al., 2004, 2006; Thompson et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2022; Wilson et al., 2010) and associated with impaired word knowledge (Grossman, 2018; M. Mesulam et al., 2009; Patterson et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2022). Similarly, individuals with logopenic PPA (PPA-L) often show poor performance on both nouns and verbs (Mack et al., 2015; Migliaccio et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2022; Wilson et al., 2010), consistent with their word-finding impairments.

Adjectives have different properties than nouns and verbs (Baker, 2003). Verbs are defined as predicates – that is, they project structure for their arguments; minimally, a verb must license a grammatical subject (Baker, 2003). In contrast, nouns are referential and can participate in coreference relations (e.g., only a noun can be the antecedent of a pronoun). Their referential nature follows on Baker’s view from a semantic criterion of identity, which allows one to judge whether two things are the same or not, and which only nouns satisfy (Baker, 2003). On Baker’s view, adjectives are neither predicative nor referential. That is, instead of being inherently predicative like verbs, adjectives require an accompanying verb to project the structure for a subject when used predicatively (e.g., when blue is used predicatively in The sky is blue, the auxiliary verb is projects the required structure for the subject the sky). Adjectives also cannot participate in coreference relations, and do not satisfy the criterion of identity. However, adjectives still have lexical content, like other open class words, and are distinguished from verbs and nouns by the syntactic structures in which they appear (Baker, 2003).

In English, adjectives are primarily used in two different syntactic structures (Huddleston et al., 2002): they can be used attributively before a noun (The blue jacket …), or predicatively after certain verbs (“The jacket seems blue”; “The sky is gray”). Linguistic analyses have traditionally posited a more complex syntactic structure for attributive than predicative adjectives (Chomsky, 1957; Cinque, 2010). In these analyses, attributive adjectives are joined into a complex syntactic structure as a modifier to a noun via adjunction, while predicative adjectives (combined with an auxiliary verb) simply serve as the main predicate in a sentence.

Adjective production in primary progressive aphasia (PPA) has been examined in only a handful of recent studies. In one study, attributive adjective production was examined in 46 individuals (Stockbridge et al., 2021). Stockbridge and colleagues used a picture elicitation task designed to elicit color and size adjectives, in an attributive adjective construction. Participants with semantic (n=16) or logopenic (n=16) PPA produced fewer correct responses than healthy controls for both color and size adjective-noun combinations. Participants with agrammatic PPA (n=10) were not impaired relative to controls on color adjectives, and were only marginally impaired on size adjectives. In another study, Cho and colleagues (Cho et al., 2022) elicited adjectives with a picture description task (the cookie theft picture from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination - BDAE; Goodglass & Kaplan, 1983), and found a reduced number of adjectives in 21 individuals with logopenic PPA relative both to individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and to healthy individuals, but they did not differentiate performance on adjectives for different structures.

Given the paucity of prior studies on adjectives in primary progressive aphasia, our expectations may be guided by earlier studies from stroke aphasia, though here as well, adjective production has been a relatively neglected area of research. Nevertheless, results from these few prior studies consistently reveal that the production of prenominal attributive adjectives is impaired in agrammatic stroke aphasia relative to healthy controls (Ahlsén et al., 1996; de Roo et al., 2003; Meltzer-Asscher & Thompson, 2014; Mondini et al., 2002; Yoo & Sung, 2020). It has also been reported that sequences of attributive adjectives are more severely impaired than single attributive adjectives – performance on sequences like big red car is worse than for big car or red car (Ahlsén et al., 1996; Berko Gleason et al., 1975; Goodglass et al., 1972; Kemmerer, 2000). Two additional studies report deficits on predicative adjectives, but did not include any comparison with attributive adjectives (Milman et al., 2014; Shankweiler et al., 2010). Direct comparisons of the production of attributive vs. predicative adjectives generally report worse performance on attributive adjectives (de Roo et al., 2003; Meltzer-Asscher & Thompson, 2014; Yoo & Sung, 2020), though one reports similarly impaired performance for both structures (Goodglass et al., 1972). Overall, these findings are consistent with a deficit at producing syntactically complex attributive adjectives.

In the current study we examined the use of adjectives in narrative samples in primary progressive aphasia and agrammatic stroke aphasia. We assessed the rate of adjective use in two constructions: attributive modification of a noun, and predicative usage following a verb. We expected reduced rates of attributive adjective production in participants with PPA-G and stroke agrammatism, but similar rates of predicative adjective production in these two groups relative to healthy controls. Moreover, we expected that the rate of attributive adjective production would correlate with syntactic deficits for agrammatic speakers. Conversely, we posited that participants with PPA-S and PPA-L will show an overall reduced rate of adjective usage relative to controls, but with no differences for attributive and predicative structures, due to the nature of their underlying language impairments: loss of word knowledge and lexical retrieval, respectively.

We also looked at lexical characteristics of adjectives that may make them easier or harder to produce, and so may affect the choice of adjectives used in the narratives. If lexical processing is intact, we expected that the lexical characteristics (e.g., length, frequency, semantic diversity) of the adjectives produced to be similar to those of healthy controls. On the other hand, if lexical processing is impaired, different patterns may emerge for different subtypes. We expected that individuals with semantic PPA will rely heavily on highly frequent adjectives that are ambiguous or that have more generic meanings that fit easily into multiple contexts (i.e., ‘semantically diverse adjectives’), due to loss of semantic knowledge in this subtype. We may also see reduced lexical diversity for logopenic PPA, as found in a previous study, though not measured specifically for adjectives (Cho et al., 2022).

2.0. Method

2.1. Participants

Narrative samples were elicited from healthy adult participants (n=24), participants with primary progressive aphasia (n=98), and participants with agrammatic aphasia following stroke (n=30). Demographic data are summarized in Table 1. An additional 12 participants were excluded from this data set, as their narrative samples totaled fewer than 75 words (PPAG:6, PPAS:2, STRG:4), as in previous work (Meltzer-Asscher & Thompson, 2014). Of note, the samples from these 12 participants contained no adjectives at all. All participants were native English speakers and were mostly right-handed (left-handed n=5), based on the Edinburgh handedness questionnaire (Oldfield, 1971). Healthy participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing and reported no prior history of psychiatric illness or neurological disease. Participants with aphasia met the same criteria other than their aphasia. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University and all participants provided informed consent.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information, with mean (standard deviation) for each variable, by group.

| C | PPA-S | PPA-L | PPA-G | STRG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 24 | 22 | 29 | 47 | 30 |

| Sex | F:11, M:13 | F:8, M:14 | F:14, M:15 | F:19, M:28 | F:14, M:16 |

| Handedness | R:24 | R:22 | L:1, R:28 | L:1, R:46 | L:3, R:27 |

| Age (years) | 62.36 (7.17) | 63.23 (6.42) | 67.56 (7.01) | 65.71 (7.54) | 57.99 (15.05) |

| Education (years) | 15.67(2.41) | 16.68(3.6) | 16.59(1.7) | 16.36(2.95) | 16.14(2.45) |

| Time Since Onset (TSO) | N/A | 46.6 (27.28) | 43.81 (25.9) | 47.87 (26.7) | 80.65 (66.05) |

| WAB (/100) | 99.82 (0.53) | 83.15 (10.29) | 90.84 (5.73) | 84.31 (7.63) | 76.71 (13.34) |

| CDR (/3) | 0 (0) | 0.33 (0.33) | 0.23 (0.29) | 0.27 (0.27) | N/A |

| MMSE (/30) | 29.71 (0.55) | 20.71 (9.57) | 24.19 (7.25) | 23.2 (8.01) | N/A |

| BNT (/60) | 58.25 (1.62) | 9.41 (5.18) | 47.96 (12.65) | 46.3 (12.65) | 28.91 (13.81) |

| NAT (subject cleft) (/5) | 5.0 (0) | 5.0 (0) | 4.67 (1) | 4.09 (1.52) | 3.33 (1.97) |

NOTE: C = healthy control participants; PPA-S = Primary Progressive Aphasia, Semantic subtype; PPA-L = logopenic subtype; PPA-G = agrammatic subtype; STRG = agrammatic aphasia subsequent to stroke. Time Since Onset (TSO) is measured in months. WAB = Western Aphasia Battery. CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating scale; MMSE = Mini-mental State exam; BNT = Boston Naming Test; NAT = Northwestern Anagram Test.

The participants with PPA were diagnosed and classified into subtypes following consensus criteria (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011; M.-M. Mesulam et al., 2012). We included participants classified as the agrammatic (n=47), logopenic (n=29), or semantic (n=22) subtype only. Individuals with mixed profiles were not included. All of the agrammatic PPA participants had agrammatic language production; none were diagnosed as the agrammatic subtype based solely on speech apraxia.

Participants with stroke-induced aphasia all had agrammatic aphasia subsequent to a single left-hemisphere ischaemic stroke. Participants were all in the chronic stage of aphasia, and were at least 6.11 months post-stroke-onset (M = 80.65 months, SD = 66.05, range: 6.11–243.38 months). The characterization, diagnosis and overall severity of agrammatic aphasia in the stroke-aphasia group was based on administration of the Western Aphasia Battery-Revised (WAB-R; Kertesz, 2006), their production patterns in spontaneous speech, and a battery of standard language tests, which included measures of spoken and written comprehension and production of words and sentences. Participants were recruited over time for other studies in our lab on language in agrammatic aphasia, and completed the narratives as part of their language assessment for those studies.

The participant groups did not differ significantly with respect to sex (χ2(4) = 0.91, p = 0.92) or education level (years of education; all p = 1). The groups also did not differ significantly in age (Bonferroni-corrected two-tailed unpooled pairwise t-tests, all p > .18) except for the STRG group, which significantly differed from the PPA-L group (t(38) = 3.15, p = 0.018). The groups with aphasia did not differ from each other with respect to symptom duration (all p > .06) except for a significant difference between the STRG and PPA-L groups (t(38) = −2.84, p = 0.043). With regard to aphasia severity, as measured by the WAB-R Aphasia Quotient (AQ) measure, the PPA-S group did not significantly differ from either agrammatic group: PPA-G (t(32.2) = 0.47, p = 1); STRG group (t(49.8) = 1.97, p = 0.329) while all other groups (PPA-L, PPA-G, STRG) significantly differ from one another (all p < .05).

Patient groups with Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA-S, PPA-L, PPA-G) did not differ from one another (all p=1) on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; Morris, 1993), which indicated mild (if any) non-verbal cognitive impairment for the PPA groups compared to healthy controls (all control comparison p < .002). Patients with stroke-induced aphasia were not assessed on the CDR. Scores from the Mini Mental-State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) were not significantly different between PPA groups (all p > .9), but all PPA groups were significantly different from the control group (all p < .002).

2.2. Procedure

All participants were given pictures depicting the story of Cinderella (n=140), a frog in a well (n=2), or a river flooding (n=10). After reviewing the story, participants retold the story to the experimenter. Some participants narrated multiple stories in the same visit. Narratives collected in the same visit (e.g., if a participant narrated the Cinderella and the frog stories) were grouped together into a single narrative sample for that participant. If a participant returned for multiple visits, we only used the narratives from their initial visits. During the elicitation, the experimenter provided no feedback other than to encourage the participant to continue if they stopped their narration before reaching the expected end of the story (based on the set of pictures they were given). Each narrative was recorded, transcribed, and coded by trained lab members in the Aphasia and Neurolinguistics Research Lab using the Northwestern Narrative Language Analysis (NNLA) framework (Hsu & Thompson, 2018).

2.3. Data extraction and coding

NNLA-coded transcriptions were converted to spreadsheet format to code for the syntactic structure for each adjective produced within a sample. Multiple adjectives within the same utterance were coded as independent occurrences, except that repeated adjectives within an utterance were only counted once (e.g., it was windy windy windy was counted as only one instance of windy). Any adjectives that occurred within meta commentary or other mazed material from the participant were not included in the analyses. Adjectives with phonological paraphasias were included if the intended target was apparent (e.g., evril stepsisters); neologisms (e.g., lova dress) were excluded. Each adjective was coded manually for its syntactic structure: attributive, predicative, or ambiguous (bolded in parenthetical examples below), following prior work (Meltzer-Asscher & Thompson, 2014).

An adjective was coded as attributive if it occupied a left adjunct position in a noun phrase (NP), before a noun or before another adjective (The pretty dress; The pretty green dress). Instances where the participant omitted the noun directly following the adjective (The beautiful… Um…) were also coded as attributive, because the attributive adjective structure had already been constructed. We coded the following words as determiners and not adjectives: another, other, both, many, more, much, neither, this, that, own (as in his own), and cardinal numerals (e.g., two in two fish).

We coded adjectives as predicative if they appeared in one of the following structures: Copular (The dress was beautiful); Descriptive (She arrived dressed up); Small clause (She considered the dress beautiful); Control (She feels beautiful in the dress); Raising (The dress seems beautiful); Get-passive (They got married); Phrasal (She got ready). An adjective was coded as ambiguous if it occurred with no surrounding context or its structure could not otherwise be determined (…pink…).

An example of the data coding and format is shown in Table 2. Across all participants, the narrative samples yielded a total of 805 attributive adjectives, 431 predicative adjectives, and 62 ambiguous adjectives. We excluded the ambiguous adjectives from our analysis, as there was no way to determine their intended syntactic structure.

Table 2.

Example of spreadsheet coding scheme (item_num counts each adjective in the data; utt_num counts each utterance in the data).

| item_num | utt_num | utterance | adjective | attributive | predicative | ambiguous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | This is her story | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 2 | The shoes are so pretty | pretty | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | The pink dress is beautiful | pink | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 3 | The pink dress is beautiful | beautiful | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 4 | Pink | pink | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | 5 | The beautiful… Um… | beautiful | 1 | 0 | 0 |

2.4. Data analysis

All data processing and analysis were carried out in R version 4.1.0 (R Core Team, 2022). For each participant, we totaled how many attributive adjectives were in their sample, and how many predicative adjectives, then divided each by their total number of utterances. This yielded a rate of attributive adjective use per utterance and predicative adjective use per utterance. These rates were natural log-transformed (log-rate=ln((#_adjectives + 1) / #_utterances); the +1 was included in the numerator to avoid the undefined natural log of 0) to create the dependent variables. For each adjective structure, we omitted participants whose log-rates fell outside 1.5 times the interquartile range for that structure. On this basis we excluded 3 controls, 1 participant with PPA-S, and 1 participant with PPA-L from the attributive model; none were excluded from the predicative model.

We fit linear regression models to assess whether any of the four groups with aphasia (PPA-G, PPA-L, PPA-S, or STRG) differed significantly in their adjective usage from healthy age-matched controls, separately for rates of attributive adjective usage and rates of predicative adjective usage. Each model intercept reflected the log-rate of adjective usage for the control group; each group coefficient reflects the difference in adjective usage between that group and the controls. For each group we report the regression coefficient estimate B with its standard error (SE) and 95% confidence interval (CI) and the t- and p-values for the significance of the group vs control difference. The p-values were Bonferroni corrected using the eight total p-values provided by both models (each model provides four coefficient estimates).

As a follow-up (exploratory) analysis, we looked at the correlations for the PPA-G group between rates of adjective use (separately for each structure) and scores (out of 5) on the subject cleft items on the Northwestern Anagram Test (NAT; Thompson et al., 2012). For each correlation, we report Kendall’s tau-b (τb) rank correlation coefficients. We selected Kendall’s tau-b as opposed to other correlation metrics (e.g., Spearman’s rho) due to the high number of ties in our dataset (Agresti, 2010). Note that we did not compute these correlations for the PPA-S or PPA-L groups because of smaller group sizes and because the scores were too close to ceiling, leaving insufficient variability for a correlation. We were also unable to compute the correlations for the STRG group, as only a small subset of participants (n=4) had scores available from the NAT.

In a second follow-up analysis, we also investigated potential differences in the lexical characteristics of the predicative and attributive adjectives our participants produced in their narrations. We use four different measures obtained through the website for the English Lexicon (elexicon) project, hosted by Washington University in St. Louis (Balota et al., 2007). First, we included word frequency (log_HAL), computed as the log-transformed values taken from the Hyperspace Analogue to Language corpus of 131 million words (Lund & Burgess, 1996). Second, we counted word length in terms of the number of phonemes in the word as standardly pronounced (i.e., regardless of whether our participant may have produced it with a paraphasia). Last, we looked at two semantic variables included in the 2019 update to the elexicon project: Semantic Diversity, a measure of the degree to which a word is ambiguous or can appear in a wide range of linguistic contexts (Hoffman et al., 2013) and Semantic Neighborhood Density, which accounts for differences between words with many semantically similar neighbors and those with only a few in an abstract semantic space (Shaoul & Westbury, 2010).

For each of these four variables we calculated the average value over the set of adjectives that each participant produced in their narrative sample, collapsing across attributive vs. predicative structure but excluding ambiguous adjectives, and counting multiple instances of the same adjective only once. For example, if a participant produced the tokens beautiful (attributive), beautiful (predicative), pink (attributive), red (ambiguous), then the set of unique adjectives is restricted to: beautiful, pink. The average for each participant was z-score transformed based on the mean and standard deviation from all participants for that measure. We fit separate linear regression models for each measure, to compare each subgroup with aphasia against the healthy controls. The p-values for each model are Bonferroni corrected.

3.0. Results

3.1. Attributive Adjectives

For attributive adjectives, the control participants and those with PPA-S and PPA-L showed similar production rates (controls: 8.0 adjectives in 28.7 utterances, mean rate = 0.28 adjectives per utterance; PPA-S: 4.9 adjectives in 22.4 utterances, mean rate = 0.22 adjectives per utterance; PPA-L: 8.8 adjectives in 30.6 utterances, mean rate = 0.29 adjectives per utterance). Compared to these groups, both the PPA-G and STRG groups showed reduced rates of production (PPA-G: 5.3 adjectives in 29.2 utterances, rate = 0.18 adjectives per utterance; STRG: 4.1 adjectives in 37.5 utterances, rate = 0.11 adjectives per utterance). Effect sizes for the difference of rate with controls (Hedge’s g) are small for PPA-S (g=−0.43), small for PPA-L (g=−0.30), but large for PPA-G (g=−0.94) and large for the STRG group (g=−1.55).

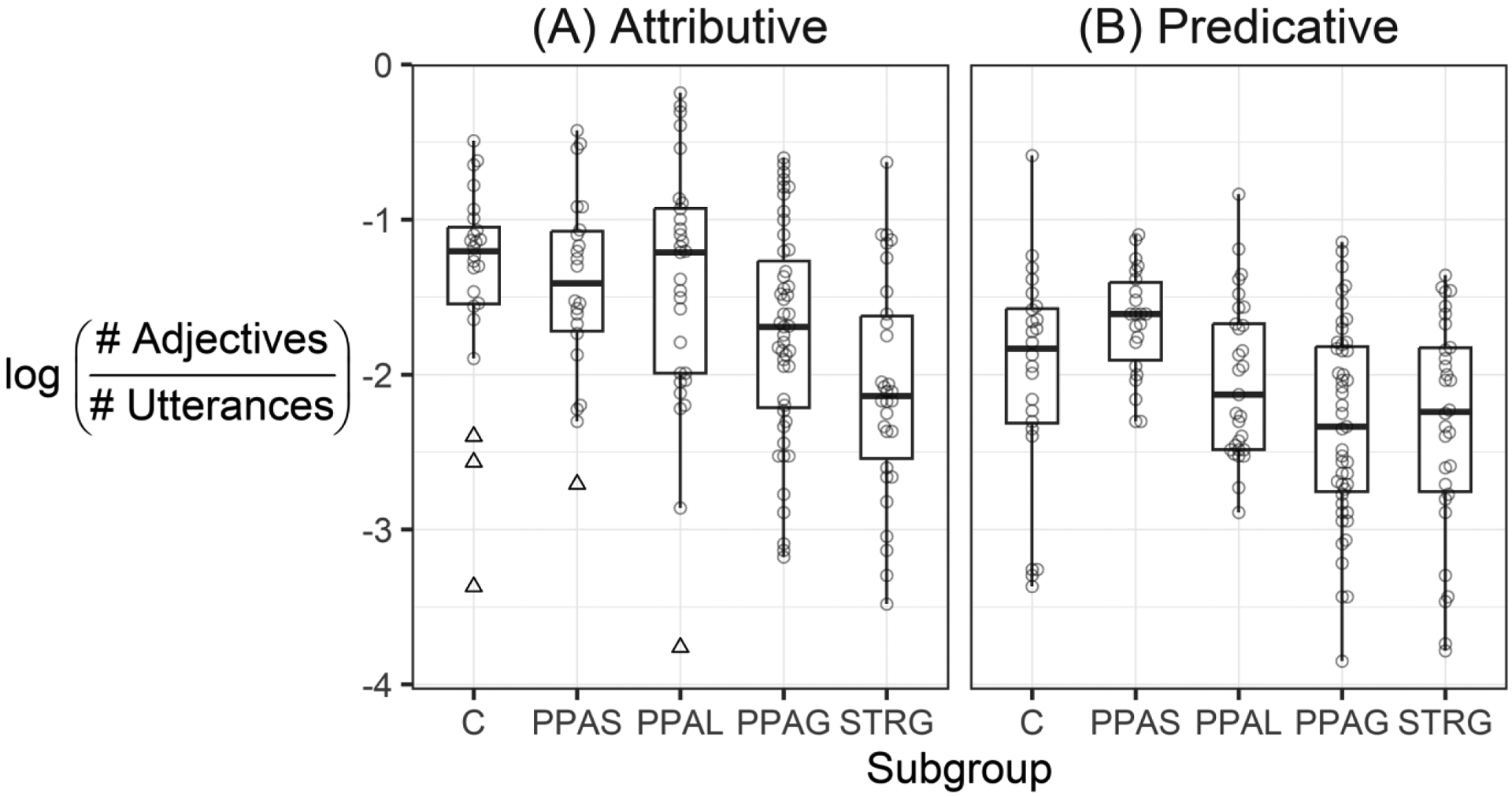

Analysis of the log-transformed rates (omitting 5 outlier participants; Figure 1a) confirmed the numerical differences in the rates of adjective usage. The rate of attributive adjective usage for the PPA-S subgroup did not differ significantly from that of controls (B=−0.20, SE = 0.20, 95% CI: [−0.59, 0.19], t = 1.02, p > .999); neither did the rate for the PPA-L subgroup (B=−0.17, SE = 0.18, 95% CI: [−0.54, 0.19], t = 0.94, p > .999). However, the rate for the PPA-G subgroup was significantly lower than that for controls (B=−0.58, SE = 0.17, 95% CI: [−0.91, −0.25], t = 3.46, p = .006), as was the rate for the STRG group (B=−0.93, SE = 0.18, 95% CI: [−1.29, −0.57], t = 5.12, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Natural log-transformed adjective usage rates for each adjective structure and participant subgroup. C = healthy controls, PPA = primary progressive aphasia (PPAS = semantic subtype; PPAL = logopenic subtype; PPAG = agrammatic subtype), STRG = agrammatic stroke aphasia. Five participants identified as outliers (open triangles) in the attributive adjective structure were omitted from analysis. No participants were identified as outliers for the predicative adjective structure.

3.2. Predicative Adjectives

For predicative adjectives, the control participants produced 3.8 adjectives in 28.7 utterances, for a rate of 0.13 adjectives per utterance, on average (Table 3b). All PPA and the STRG groups’ predicate adjective production patterns were comparable (PPA-S: 3.4 adjectives in 22.4 utterances, rate = 0.15 adjectives per utterance; PPA-L: 3.8 adjectives in 30.6 utterances, rate = 0.12 adjectives per utterance: PPA-G: 2.5 adjectives in 29.2 utterances, rate = 0.09 adjectives per utterance; STRG: 3.7 adjectives in 37.5 utterances, rate = 0.10 adjectives per utterance). Effect sizes for the difference of rate with controls (Hedge’s g) are medium for PPA-S (g=0.59), very small for PPA-L (g=−0.05), small for PPA-G (g=−0.47) and small for the STRG group (g=−0.45).

Table 3.

Rates of adjective use in subgroups with aphasia compared to healthy controls for (A) attributive adjectives and (B) predicative adjectives. The comparison with controls includes the effect size (Hedge’s g), and regression coefficient with its significance level and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for the regression coefficient. Significant group differences indicated by *.

| Group | Number of adjectives | Number of utterances | Rate | Comparison vs. controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Attributive | |||||

| Control | 8.0 (2.7) | 28.7 (10.4) | 0.28 | ||

| PPAS | 4.9 (3.8) | 22.4 (12.6) | 0.22 | g=−0.43; B=−0.20, SE=.20, t=1.02, p>.999; 95% CI: −0.59, 0.19 | |

| PPAL | 8.8 (7.7) | 30.6 (11.9) | 0.29 | g=−0.30; B=−0.17, SE=.18, t=0.94, p>.999; 95% CI: −0.54, 0.19 | |

| PPAG* | 5.3 (4.6) | 29.2 (13.4) | 0.18 | g=−0.94; B=−0.58, SE=.17, t=3.46, p=.006; 95% CI: −0.91, −0.25 | |

| STRG* | 4.1 (4.5) | 37.5 (23.5) | 0.11 | g=−1.55; B=−0.93, SE=.18, t=5.12, p<.001; 95% CI: −1.29, −0.57 | |

| B. Predicative | |||||

| Control | 3.8 (3.3) | 28.7 (10.4) | 0.13 | ||

| PPAS | 3.4 (3.0) | 22.4 (12.6) | 0.15 | g=0.59; B=0.34, SE=.18, t=1.89, p=.486; 95% CI: −0.02, 0.7 | |

| PPAL | 3.8 (3.6) | 30.6 (11.9) | 0.12 | g=0.05; B=−0.03, SE=.17, t=0.17, p>.999; 95% CI: −0.36, 0.3 | |

| PPAG | 2.5 (2.9) | 29.2 (13.4) | 0.09 | g=−0.47; B=−0.32, SE=.15, t=2.06, p=.328; 95% CI: −0.62, −0.01 | |

| STRG | 3.7 (5.3) | 37.5 (23.5) | 0.10 | g=−0.45; B=−0.32, SE=17, t=1.93, p=.442; 95% CI: −0.65, 0.01 | |

Results from the regression models were consistent with these numerically similar rates of predicative adjective use (Figure 1b). Statistical comparison against the control group did not yield significant differences for the PPA-S subgroup (B=0.34, SE = 0.18, 95% CI: [−0.02, 0.7], t = 1.89, p = .49); the PPA-L subgroup (B=−0.03, SE = 0.17, 95% CI: [−0.36, 0.3], t = 0.17, p > .999), the PPA-G subgroup (B=−0.32, SE = 0.15, 95% CI: [−0.62, −0.01], t = 2.06, p = .328), or the STRG group (B=−0.32, SE = 0.17, 95% CI: [−0.65, 0.01], t = 1.93, p = .442).

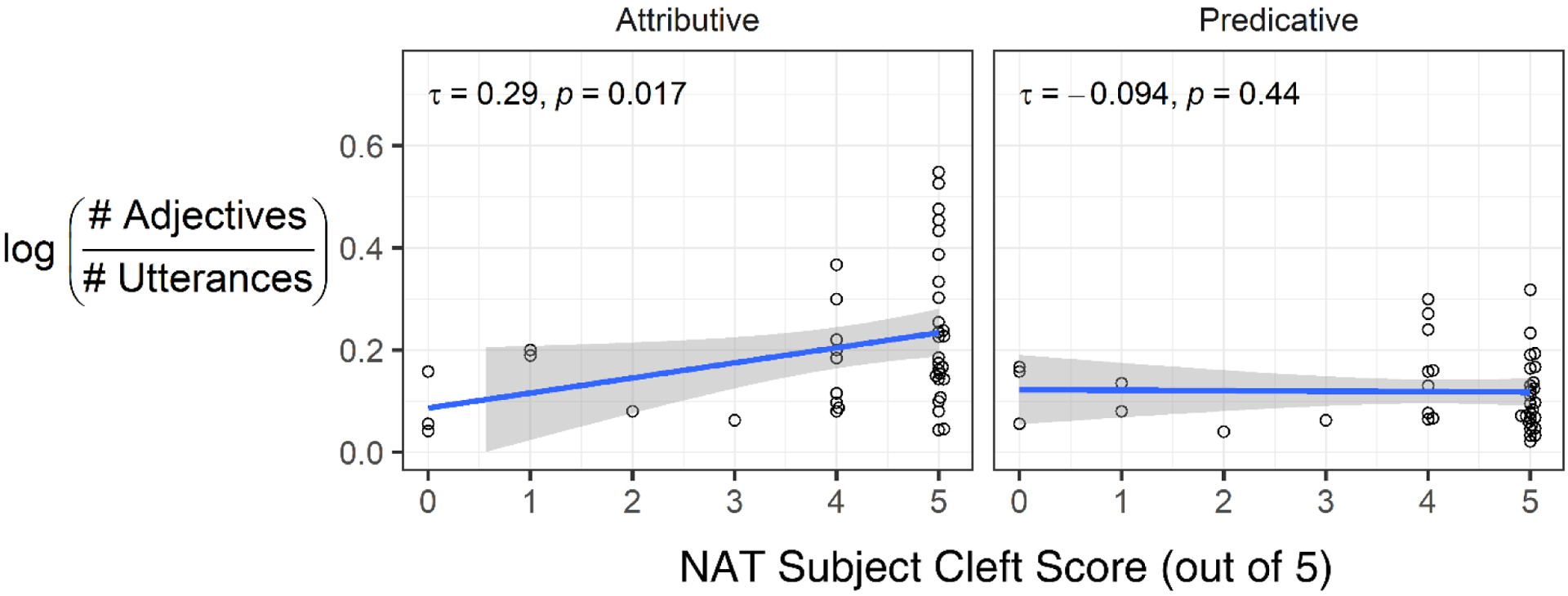

3.3. Correlations with complex structure

For the NAT Subject Cleft scores (PPA-G mean = 4.12, SD = 1.53), we found a significant positive correlation for attributive adjectives (τb=0.29, p= 0.017), indicating that the less impaired participants (i.e., those who scored higher on the subject cleft measure) used more attributive adjectives in their narrative productions (Figure 2). In contrast, there was a negative, non-significant correlation between rate of predicative adjective use and subject cleft production (τb=−0.09, p=0.444).

Figure 2.

Correlations between subject cleft scores (top row) or subject relative clause scores (bottom row) and rates of attributive (left) and predicative (right) adjective use in narratives by participants with agrammatic primary progressive aphasia. NAT = Northwestern Anagram Test. NAVS = Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences. Only the correlation between NAT subject cleft scores and the rate of attributive adjective use achieved significance.

3.4. Lexical measures

Word frequency. The healthy control participants produced adjectives with an average log_HAL frequency of 10.46 (z=−0.55) (Table 4a). The participants with aphasia generally used higher-frequency adjectives than the controls, with the exception of the PPA-L group, who used slightly more frequent adjectives than controls, though this difference did not reach significance (mean: 10.82; z=−0.03, B=.52, SE=.24, t=2.16, p=.16). The frequencies of the adjectives in the narratives were significantly higher relative to controls for the PPA-S group (mean: 11.63; z=0.53, B=1.08, SE=.26, t=4.22, p<.001), the PPA-G group (mean: 11.19; z=0.12, B=.67, SE=.22, t=3.06, p=.013), and the STRG group (mean: 11.15; z=0.09, B=.64, SE=.24, t=2.64, p=.046).

Table 4.

Values for lexical characteristics of adjectives (and standard deviation) produced in narrative samples, with comparisons of z-scores for each subgroup of aphasia vs. the healthy controls. Star (*) indicates a significant group difference against the control group (p-values are Bonferroni corrected).

| Measure | Group | Value (SD) | Z-score | Z-score comparison vs. controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.Frequency | ||||

| Control | 10.46 (0.96) | −0.55 | ||

| PPAS* | 11.63 (0.59) | 0.53 | B=1.08, SE=.26, t=4.22, p<.001 | |

| PPAL | 10.82 (1.38) | −0.03 | B=0.52, SE=.24, t=2.16, p=.161 | |

| PPAG* | 11.19 (1.04) | 0.12 | B=0.67, SE=.22, t=3.06, p=.013 | |

| STRG* | 11.15 (0.91) | 0.09 | B=0.64, SE=.24, t=2.16, p=.046 | |

| B. Length | ||||

| Control | 4.97 (0.78) | 0.51 | ||

| PPAS | 4.15 (0.91) | 0.04 | B=−0.47, SE=.29, t=1.58, p=.580 | |

| PPAL | 4.45 (0.86) | −0.02 | B=−0.53, SE=.27, t=1.93, p=.281 | |

| PPAG* | 4.17 (0.91) | −0.32 | B=−0.83, SE=.25, t=3.27, p=.007 | |

| STRG | 4.54 (1.19) | 0.06 | B=−0.45, SE=.28, t=1.59, p=.567 | |

| C. Semantic Diversity | ||||

| Control | 1.81 (0.13) | −0.55 | ||

| PPAS* | 2.04 (0.15) | 0.85 | B=1.39, SE=.28, t=4.99, p<.001 | |

| PPAL | 1.86 (0.16) | −0.22 | B=0.33, SE=.26, t=1.24, p>.999 | |

| PPAG | 1.90 (0.16) | 0.01 | B=0.56, SE=.24, t=2.33, p=.105 | |

| STRG | 1.90 (0.16) | 0.01 | B=0.56, SE=.26, t=2.10, p=.186 | |

| D. Semantic Neighborhood Density | ||||

| Control | 0.63 (0.03) | −0.39 | ||

| PPAS* | 0.67 (0.02) | 0.60 | B=0.99, SE=.23, t=4.30, p<.001 | |

| PPAL | 0.63 (0.06) | −0.11 | B=0.22, SE=.27, t=0.84, p>.999 | |

| PPAG | 0.65 (0.03) | −0.01 | B=0.46, SE=.25, t=1.89, p=.307 | |

| STRG* | 0.66 (0.03) | 0.25 | B=0.64, SE=.22, t=2.93, p=.02 | |

Word length. With respect to word length, the healthy control participants produced adjectives with an average of 4.97 phonemes (z=0.51) (Table 4b). The PPA-S group produced comparably long adjectives, that did not differ significantly from the length of the control group’s adjectives (mean: 4.15; z=0.04, B=−.47, SE=.29, t=1.58, p=.58). Likewise, the lengths of adjectives used by the PPA-L group (mean: 4.45; z=−0.02, B=−.53, SE=.27, t=1.93, p=.28) and the STRG group (mean: 4.54; z=0.06, B=−.45, SE=.28, t=1.59, p=.57) were not significantly shorter than those of the control group. However, the PPA-G group did use significantly shorter adjectives on average relative to controls (mean: 4.17; z=−0.32, B=−.83, SE=.25, t=3.27, p=.007).

Semantic diversity. For the semantic diversity measure, control participants used adjectives with an average value of 1.81 (z=−0.55) (Table 4c), providing a baseline “typical” value for this variable. The value for adjectives used by the PPA-S group was significantly higher (mean: 2.04; z=0.85, B=1.39, SE=.28, t=4.99, p<.001). However, the values for adjectives used by the other groups did not differ significantly from the control group’s adjectives, for PPA-L (mean: 1.86; z=−0.22, B=0.33, SE=.26, t=1.24, p=1), for PPA-G (mean: 1.90; z=0.01, B=0.56, SE=.24, t=2.33, p=.105), or for the STRG group (mean: 1.90; z=0.01, B=0.56, SE=.26, t=2.10, p=.186).

Semantic Neighborhood Density. Finally, the control group used adjectives with an average Semantic Neighborhood Density score of 0.63 (z=−0.39) (Table 4d), providing a baseline value for this variable. In comparison, the adjectives used by the PPA-S group were from significantly denser semantic neighborhoods (mean: 0.67; z=0.60, B=0.99, SE=.23, t=4.30, p<.001). The average semantic neighborhood of the adjectives used by the PPA-L group did not differ from that of controls (mean: 0.63; z=−0.11, B=0.22, SE=.27, t=0.84, p=1), nor did that of the PPA=G group (mean: 0.65; z=−0.01, B=0.46, SE=.25, t=1.89, p=.307). However, the STRG group also used adjectives that were from significantly denser neighborhoods than the control group (mean: 0.66; z=0.25, B=0.64, SE=.22, t=2.93, p=.02).

4.0. Discussion

We examined the rate of adjective usage in narratives in two different syntactic structures: an attributive structure, in which the adjective precedes the noun, and a predicative structure, in which the adjective works with an auxiliary verb (to be) to form a predicate. Narrative samples from healthy controls were used to set the baseline rate (per utterance) of adjective usage in each structure. We compared the rates of adjective use in each structure against the control baseline rates for three subtypes of primary progressive aphasia (PPA: semantic, logopenic, agrammatic) and from a group of participants with agrammatic stroke aphasia. We expected that our two agrammatic groups would show reduced production of attributive but not predicative adjectives, correlating with their syntactic impairment, whereas we expect that the other two groups (semantic and logopenic subtypes of PPA) would not be more impaired on one structure than the other, and may show signs of abnormal lexical characteristics in the adjectives produced.

Because a reduced number of adjectives in narrative speech could reflect a smaller overall speech sample, rather than difficulty with a particular syntactic structure, we accounted for potential differences in the number of opportunities for adjective production across groups in two ways. First, we excluded participants with small speech samples, and who therefore only had very limited opportunities to produce adjectives. Second, we normed each participant’s raw number of adjectives produced in each structure by that participant’s total number of utterances. By looking at the rate of adjective production, rather than the absolute number of adjectives produced, we protected against an artificially low count due to a more limited number of opportunities to produce adjectives. Note that we normed the adjective production rate to the number of utterances in order to put opportunities for attributive and predicative adjectives on similar footing.

Starting with the results from the agrammatic primary progressive aphasia (PPA-G) group, we found that they produced attributive adjectives at a lower rate than the healthy controls. Moreover, the rate of attributive adjective use for the PPA-G group correlated with their production of complex syntactic structures (subject cleft sentences) from a standardized assessment (the Northwestern Anagram Test). We argue that both findings are consistent with a grammatical impairment. Such an impairment could lead to an avoidance of the complex syntactic structure of attributive adjectives. Predicative adjectives were produced at a similar rate to the healthy controls, and their rate of production did not correlate with production of complex syntactic structures.

The pattern of adjective usage in narratives for the PPA-G group was similar to that of the stroke agrammatism group. Relative to healthy controls, the agrammatic stroke group also showed an avoidance of attributive adjectives, with no significant drop in their rates of predicative adjective use. This is consistent with prior results of impaired production of attributive adjectives in agrammatic stroke aphasia (Ahlsén et al., 1996; Berko Gleason et al., 1975; de Roo et al., 2003; Goodglass et al., 1972; Kemmerer, 2000; Meltzer-Asscher & Thompson, 2014; Mondini et al., 2002; Yoo & Sung, 2020). In contrast, the semantic and logopenic PPA groups did not show this pattern – both groups produced adjectives at rates that were not different to that of controls, for both attributive and predicative structures. Note that we did not have scores from the NAT for most of the stroke participants, so we were unable to examine correlations with their rates of adjective use. Correlations were also not conducted for the semantic and logopenic groups due to the smaller number of participants in each group. As well, their overall lack of impairment on these measures left insufficient variability in their scores for a correlation analysis (NAT subject cleft score for PPAS: mean = 5.00, SD = 0.00; for PPAL: mean = 4.67, SD = 1.00).

In addition to the rate of use of adjectives in attributive and predicative structures, we also examined lexical properties of the adjectives produced by each group, irrespective of the structure they appeared in. The agrammatic group with primary progressive aphasia used adjectives that were higher in frequency and shorter on average than those of the healthy controls. This group did not show differences from controls in terms of the semantic diversity of the adjectives they use, nor did they show differences in the semantic neighborhood density of their adjectives. Both results are consistent with spared lexical knowledge. The increased use of words that are easier to access (i.e., shorter words with higher frequency) is consistent with impaired phonological encoding and articulation during language production and an overall profile of non-fluent language in agrammatic PPA (Mack et al., 2015). Notably, this pattern of lexical simplification in agrammatic speakers has been reported in previous literature to be more prevalent for verbs than for nouns (Mack et al., 2015), with no studies to our knowledge showing this pattern for adjectives. The present findings indicate that lexical simplification is evident for adjectives as well. As we did not examine nouns and verbs here, it is not clear whether adjectives would pattern with one or the other in this group or would be distinct from both.

The pattern for the agrammatic stroke group was partly similar and partly different to that of the agrammatic PPA group. Like the PPA-G group, the agrammatic stroke group’s adjectives were of higher frequency than those of the controls, though unlike the PPA-G group they did not differ significantly in length. The agrammatic stroke group’s adjectives were also of similar semantic diversity as those of the controls, though they tended to be from more semantically dense neighborhoods. While the use of high frequency words from dense semantic neighborhoods is potentially consistent with impaired lexical access in stroke agrammatism, it is not clear why impaired lexical access appears to lead to these different patterns for the two agrammatic groups. This requires further investigation.

In contrast, the adjectives produced by the semantic PPA group had a different lexical profile. The adjectives that they produced were higher in frequency relative to those produced by the control group, but they did not different in length. This pattern is consistent with the loss of lexical knowledge for infrequent words. The semantic group also relied heavily on semantically diverse adjectives – that is, on adjectives that have more generic meanings that fit easily into multiple contexts. As well, the adjectives used by the semantic group were from more semantically dense neighborhoods. Both findings are consistent with loss of specific semantic knowledge, with preservation of knowledge in richly interconnected areas of the semantic network. While prior similar findings were observed to be more evident for nouns than verbs, adjectives were not examined (Mack et al., 2015); as we did not examine nouns or verbs, it cannot be established whether adjectives are similar to either or both. The adjectives produced by the logopenic group did not differ from those of the control group on any of our lexical measures. Thus, despite issues with lexical access that has been reported for this group (Gorno-Tempini et al., 2011), and prior findings of reduced lexical diversity (Cho et al., 2022) such issues do not appear to have impacted the (average) lexical characteristics of the choice of adjectives used in their narratives here.

5.0. Conclusions

In sum, the patterns of adjective use for agrammatic and semantic primary progressive aphasia appear to be consistent overall with their profiles of syntactic impairment and difficulty with phonological encoding and articulation for the one group, and loss of conceptual / lexical knowledge for the other. However, questions remain regarding differences between the two forms of agrammatism in the lexical characteristics of their adjectives, and regarding the unexpectedly unremarkable lexical characteristics of adjectives used by the logopenic group.

As well, our study is not without limitations. First, the participants were recruited over time for other studies, not specifically for this study. This limitation shows in the unequal number of participants across groups. We chose our statistical analyses carefully to accommodate the unequal group numbers, and we note as well that the groups nevertheless showed only minor demographic differences. The relatively large sample size of the agrammatic PPA group bodes well for the power of our study to have been adequate for the effect sizes we observed for that group. However, it is possible that the small effects for the logopenic or semantic subtypes of PPA were underpowered, given the smaller numbers of participants in those groups (although those groups were nevertheless larger than in many studies of language in aphasia). There was also some small variation in the stories that the participants narrated. While the majority narrated the Cinderella story, a small number were given different stories. This may have influenced the tendency to produce or not produce certain adjectives. To examine the impact of this variation, we reran all of the analyses excluding data from the 12 non-Cinderella narratives. The results showed only small numerical differences to those reported above, with no changes to any significance levels. Nevertheless, future studies may wish to either deliberately homogenize the narrative content to provide some control over this variation, or to deliberately broaden it evenly across participants, to perhaps allow for more variety in the adjectives produced.

Another limitation concerns the conclusions we can draw from a narrative elicitation task. Attributive adjectives are optional elements, and so their absence in our agrammatic speakers may reflect a tendency rather than a loss of ability per se. While we believe that such a tendency is consistent with a grammatical impairment – it is not unreasonable to suggest that a grammatical structure that is difficult may be avoided. However, a task that requires production of attributive adjectives would sidestep this issue, and could more readily establish whether a reduction in attributive adjective production reflects an impairment. In part, the correlation we observed between complex syntax and attributive (but not predicative) adjectives was intended to strengthen this argument, but here too there are limitations. Our participants with stroke-aphasia did not have the NAT subject-cleft scores that we used for the agrammatic PPA group; showing similar correlations for both agrammatic groups would have made a stronger argument. Finally, it might be argued that alternate or additional measures of complex syntax would be more appropriate than our measure from the NAT to shed light on the question of whether the tendency to avoid attributive adjectives can be accounted for in terms of an agrammatic impairment. We leave this issue to future research.

Despite these questions and limitations, the results suggest that attributive adjectives are impacted in individuals with agrammatic language production, and add a new dimension to the description of agrammatism. Our results further suggest that attributive adjectives may be a fruitful target for improved treatment and recovery of agrammatic language.

Highlights.

We examined production of attributive and predicative adjectives in primary progressive aphasia

All PPA groups were similar to healthy controls in their rate of predicative adjective production

Participants with agrammatic PPA, but not other PPA types, avoided attributive adjectives

Rates of attributive adjective use in PPA-G correlated with production of complex syntax

Participants with PPA-S overused vague, ambiguous adjectives, consistent with lost word knowledge

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank the many members of the Aphasia and Neurolinguistics Research Laboratory for their assistance with data collection and transcription.

Funding:

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health: grant numbers R01-DC008552 (M-Marsel Mesulam) and R01- DC01948 (Cynthia K. Thompson).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT authorship contributions: Matthew Walenski: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing –review & editing, Supervision. Thomas Sostarics: Data Curation, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing –review & editing. M. Marsel Mesulam: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Cynthia K. Thompson: Methodology, Resources, Writing -review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Statement of competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Agresti A (2010). Analysis of Ordinal Categorical Data (2nd edition). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlsén E, Nespoulous JL, Dordain M, Stark J, Jarema G, Kadzielawa D, Obler LK, & Fitzpatrick PM (1996). Noun phrase production by agrammatic patients: A cross-linguistic approach. Aphasiology, 10(6), 543–559. 10.1080/02687039608248436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair -Ouellet Noémie, Fossard M, Macoir J, & Laforce R (2020). The Nonverbal Processing of Actions Is an Area of Relative Strength in the Semantic Variant of Primary Progressive Aphasia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(2), 569–584. 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MC (2003). Lexical Categories: Verbs, Nouns and Adjectives. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Yap MJ, Hutchison KA, Cortese MJ, Kessler B, Loftis B, Neely JH, Nelson DL, Simpson GB, & Treiman R (2007). The English Lexicon Project. Behavior Research Methods, 39(3), 445–459. 10.3758/BF03193014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berko Gleason J, Goodglass H, Green E, Ackerman N, & Hyde MR (1975). The retrieval of syntax in Broca’s aphasia. Brain and Language, 2, 451–471. 10.1016/S0093-934X(75)80083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Cousins KAQ, Shellikeri S, Ash S, Irwin DJ, Liberman MY, Grossman M, & Nevler N (2022). Lexical and Acoustic Speech Features Relating to Alzheimer Disease Pathology. Neurology, 99(4), e313–e322. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N (1957). Syntactic Structures. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque G (2010). The Syntax of Adjectives: A Comparative Study. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cotelli M, Borroni B, Manenti R, Alberici A, Calabria M, Agosti C, Arévalo A, Ginex V, Ortelli P, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Padovani A, & Cappa SF (2006). Action and object naming in frontotemporal dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration. Neuropsychology, 20(5), 558–565. 10.1037/0894-4105.20.5.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roo E, Kolk H, & Hofstede B (2003). Structural properties of syntactically reduced speech: A comparison of normal speakers and Broca’s aphasics. Brain and Language, 86(1), 99–115. 10.1016/S0093-934X(02)00538-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Gleason JB, Bernholtz NA, & Hyde MR (1972). Some Linguistic Structures in the Speech of a Broca’s Aphasic. Cortex, 8(2), 191–212. 10.1016/S0010-9452(72)80018-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, & Kaplan E (1983). Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE), 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, Ogar JM, Rohrer JD, Black S, Boeve BF, Manes F, Dronkers NF, Vandenberghe R, Rascovsky K, Patterson K, Miller BL, Knopman DS, Hodges JR, Mesulam MM, & Grossman M (2011). Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology, 76(11), 1006–1014. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M (2018). Linguistic Aspects of Primary Progressive Aphasia. Annual Review of Linguistics, 4(1), 377–403. 10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011516-034253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis AE, Heidler-Gary J, Newhart M, Chang S, Ken L, & Bak TH (2006). Naming and comprehension in primary progressive aphasia: The influence of grammatical word class. Aphasiology, 20(2–4), 246–256. 10.1080/02687030500473262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis AE, Oh S, & Ken L (2004). Deterioration of naming nouns versus verbs in primary progressive aphasia. Annals of Neurology, 55(2), 268–275. 10.1002/ana.10812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman P, Lambon Ralph MA, & Rogers TT (2013). Semantic diversity: A measure of semantic ambiguity based on variability in the contextual usage of words. Behavior Research Methods, 45(3), 718–730. 10.3758/s13428-012-0278-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C-J, & Thompson CK (2018). Manual Versus Automated Narrative Analysis of Agrammatic Production Patterns: The Northwestern Narrative Language Analysis and Computerized Language Analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(2), 373–385. 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-17-0185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston RD, Pullum GK, & Bauer L (2002). The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerer D (2000). Selective impairment of knowledge underlying prenominal adjective order: Evidence for the autonomy of grammatical semantics. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 13(1), 57–82. 10.1016/S0911-6044(99)00020-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A (2006). Western Aphasia Battery—Revised. APA PsycTests. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft15168-000 [Google Scholar]

- Lund K, & Burgess C (1996). Producing high-dimensional semantic spaces from lexical co-occurrence. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28(2), 203–208. 10.3758/BF03204766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JE, Chandler SD, Meltzer-Asscher A, Rogalski E, Weintraub S, Mesulam M-M, & Thompson CK (2015). What do pauses in narrative production reveal about the nature of word retrieval deficits in PPA? Neuropsychologia, 77, 211–222. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte K, Graham NL, Black SE, Tang-Wai D, Chow TW, Freedman M, Rochon E, & Leonard C (2014). Verb production in the nonfluent and semantic variants of primary progressive aphasia: The influence of lexical and semantic factors. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 31(7–8), 565–583. 10.1080/02643294.2014.970154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer-Asscher A, & Thompson CK (2014). The forgotten grammatical category: Adjective use in agrammatic aphasia. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 30, 48–68. 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M, Rogalski E, Wieneke C, Cobia D, Rademaker A, Thompson C, & Weintraub S (2009). Neurology of anomia in the semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia. Brain, 132(9), 2553–2565. 10.1093/brain/awp138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M-M (2007). Primary Progressive Aphasia: A 25-year Retrospective. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 21(4), S8. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31815bf7e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M-M, Wieneke C, Thompson C, Rogalski E, & Weintraub S (2012). Quantitative classification of primary progressive aphasia at early and mild impairment stages. Brain, 135(5), 1537–1553. 10.1093/brain/aws080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio R, Boutet C, Valabregue R, Ferrieux S, Nogues M, Lehéricy S, Dormont D, Levy R, Dubois B, & Teichmann M (2016). The Brain Network of Naming: A Lesson from Primary Progressive Aphasia. PLOS ONE, 11(2), e0148707. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milman L, Clendenen D, & Vega-Mendoza M (2014). Production and integrated training of adjectives in three individuals with nonfluent aphasia. Aphasiology, 28(10), 1198–1222. 10.1080/02687038.2014.910590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mondini S, Jarema G, Luzzatti C, Burani C, & Semenza C (2002). Why Is “Red Cross” Different from “Yellow Cross”?: A Neuropsychological Study of Noun–Adjective Agreement within Italian Compounds. Brain and Language, 81(1), 621–634. 10.1006/brln.2001.2552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC (1993). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology, 43(11), 2412-a. 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC (1971). The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia, 9(1), 97–113. 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson K, Nestor PJ, & Rogers TT (2007). Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8(12), Article 12. 10.1038/nrn2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankweiler D, Palumbo LC, Fulbright RK, Mencl WE, Van Dyke J, Kollia B, Thornton R, Crain S, & Harris KS (2010). Testing the limits of language production in long-term survivors of major stroke: A psycholinguistic and anatomic study. Aphasiology, 24(11), 1455–1485. 10.1080/02687031003615227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaoul C, & Westbury C (2010). Exploring lexical co-occurrence space using HiDEx. Behavior Research Methods, 42(2), 393–413. 10.3758/BRM.42.2.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveri MC, & Ciccarelli N (2007). Naming of grammatical classes in frontotemporal dementias: Linguistic and non linguistic factors contribute to noun-verb dissociation. Behavioural Neurology, 18(4), 197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockbridge MD, Matchin W, Walker A, Breining B, Fridriksson J, Hickok G, & Hillis AE (2021). One cat, two cats, red cat, blue cats: Eliciting morphemes from individuals with primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology, 35(12), 1611–1622. 10.1080/02687038.2020.1852167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK, Lukic S, King MC, Mesulam MM, & Weintraub S (2012). Verb and noun deficits in stroke-induced and primary progressive aphasia: The Northwestern Naming Battery. Aphasiology, 26(5), 632–655. 10.1080/02687038.2012.676852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CK, & Mack JE (2014). Grammatical impairments in PPA. Aphasiology, 28(8–9), 1018–1037. 10.1080/02687038.2014.912744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Walenski M, Litcofsky K, Mack JE, Mesulam MM, & Thompson CK (2022). Verb production and comprehension in primary progressive aphasia. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 64, 101099. 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2022.101099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Henry ML, Besbris M, Ogar JM, Dronkers NF, Jarrold W, Miller BL, & Gorno-Tempini ML (2010). Connected speech production in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Brain, 133(7), 2069–2088. 10.1093/brain/awq129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, & Sung JE (2020). Effects of Syntactic Priming on the Adjective Production in Persons With Aphasia. Journal of Speech-Language & Hearing Disorders, 29(2), 23–34. 10.15724/jslhd.2020.29.2.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]