Abstract

Drought is one of the major abiotic stresses affecting the maize production worldwide. As a cross-pollination crop, maize is sensitive to water stress at flowering stage. Drought at this stage leads to asynchronous development of male and female flower organ and increased interval between anthesis and silking, which finally causes failure of pollination and grain yield loss. In the present study, the expansin gene ZmEXPA5 was cloned and its function in drought tolerance was characterized. An indel variant in promoter of ZmEXPA5 is significantly associated with natural variation in drought-induced anthesis-silking interval. The drought susceptible haplotypes showed lower expression level of ZmEXPA5 than tolerant haplotypes and lost the cis-regulatory activity of ZmDOF29. Increasing ZmEXPA5 expression in transgenic maize decreases anthesis-silking interval and improves grain yield under both drought and well-watered environments. In addition, the expression pattern of ZmEXPA5 was analyzed. These findings provide insights into the genetic basis of drought tolerance and a promising gene for drought improvement in maize breeding.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11032-023-01432-x.

Keywords: Maize (Zea mays L.), Drought, Anthesis-silking interval, Expansin, ZmEXPA5

Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is an essential cereal crop for food, feed, and biofuel worldwide (Godfray et al. 2010). However, drought has become one of the major threats for maize production due to the global climate warming and water scarcity (Gupta et al. 2020). Breeding efforts have steadily contributed to yield increase of maize over the past decades, but the tolerance to drought stress has continuously decreased (Lobell et al. 2014). Thus, there is tremendous demand for improvement of drought tolerance in maize.

The drought tolerance is a complex quantitative trait and the complicated interaction between genotype and environment makes it difficult to dissect the underlying genetic architecture or mine regulatory genes (Wu et al. 2021). Numerous effects had been made to identify the key genes regulating drought tolerance based on GWAS and omics technologies (Yang et al. 2014). And cumulative evidences suggest that it is an effective strategy to decrease the negative influence of drought in crops by the genomic manipulation of drought tolerance–related genes (Zhu et al. 2016). For instance, the overexpression of ZmVPP1, which encodes a vacuolar-type H(+) pyro-phosphatase, enhanced root development and water use efficiency in maize under drought (Wang et al. 2016). The golden 2–like transcription factor gene ZmGLK44 regulates the tryptophan synthesis pathway in maize by activating the tryptophan synthase TSB2 to maintain higher levels of tryptophan synthesis under drought. Transgenic plants of ZmGLK44 showed higher survival rate and water use efficiency under drought (Zhang et al. 2021a). Drought-Related Environment-specific Super eQTL Hotspot on chromosome 8 (DRESH8) and ZmMYBR38 could mediate the balance between drought tolerance and yield-related traits via a transposable element–mediated inverted repeats (TE-IR)–derived sRNA. The deletion of DRESH8 enhanced the survival rate than wild-type maize under drought (Sun et al. 2023). The overexpression of the NAC transcription factor gene ZmNAC111 enhanced drought tolerance in maize by promoting the closure of leaf stomata under drought stress and improving water use efficiency (Mao et al. 2015). The drought-tolerant allele of ZmSRO1d enhanced the mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of ZmSRO1d to the target protein ZmRBOHC, which promotes stomatal closure via increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in guard cells (Gao et al. 2022). The ABA-inducible ZmDRO1, the homolog of DEEPER ROOTING 1 (DRO1) in rice, generated more downward root angle and thus increased the grain yield under drought and did not reduce yield under non-drought conditions (Feng et al. 2022). Overexpression of ZmCPK35 and ZmCPK37 significantly enhanced ABA-activated S-type anion channel in guard cells and showed significant yield-enhancing advantage under drought conditions in maize (Li et al. 2022a). Overexpressing ZmRtn16 maize plants had significantly higher yields than wild-type plants and showed no negative effect on the yield under normal water conditions (Tian et al. 2023).

As a cross-pollination crop, maize is most sensitive to drought during flower development. Drought at flowering will cause asynchronous development between tassel and ear and thus prolongs the anthesis and silking interval (ASI), which results in significant loss of grain yield (Bruce et al. 2002; Tuberosa et al. 2002). Recently, a transcriptomic analysis of the tassel and ear under different water treatments revealed that mass of cell growth and expansion-related genes, such as expansin, aquaporin, and xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET), was down-regulated in ear and silk under drought. And drought-induced expression of maize α-expansin4 (ZmEXPA4) accelerates silk emergence and reduces ASI under drought (Liu et al. 2021a). These results suggest a potential role of expansin genes in crop drought tolerance improvement.

Expansin genes are widely found in plant kingdom and encode cell wall proteases that regulate cell wall extension and relaxation (Hepler et al. 2020). In recent years, a growing number of studies have identified the involvement of expansins in drought stress adaption. The overexpression of TaEXPA2 in wheat increased the antioxidant enzyme activity and number of lateral roots under drought (Yang et al. 2020). The transgenic Arabidopsis lines with higher RhEXPA4 expression displayed increased survival rates under drought (Lu et al. 2013). The overexpression of cotton expansin-like B gene GhEXLB2 showed enhanced drought tolerance at germination, seeding, and flowering stages (Zhang et al. 2021b). Overexpression of EXPA4 in tobacco conferred tolerance to drought and showed less cell damage, proline accumulation, and high expression of several stress-response genes, while the EXPA4 RNAi mutant tobacco displayed increased sensitivity to drought stress (Chen et al. 2018). The transgenic tobacco with overexpression of AtEXPA18 showed enhanced growth rate than wild-type plants under drought stress (Abbasi et al. 2021).

Previous transcriptomic analyses showed that the expression of the expansin gene ZmEXPA5 of maize was drought-induced in drought-tolerant inbreds (Zhang et al. 2017; Hao et al. 2020). Here, we showed an indel variant in the promoter region of ZmEXPA5 is associated with the maize drought tolerance at flowering stage. The deletion haplotype of the indel variant lost cis-regulation ability against transcription factor ZmDOF29 and displayed lower gene expression than insertion haplotype under drought. Transgenic studies demonstrated that overexpression of ZmEXPA5 conferred drought tolerance in maize, decreases the gap between anthesis and silking, and improves grain yield under both drought and well-watered environments. Further analysis revealed ZmEPXA5 is negatively regulated by ABA and IAA treatments.

Materials and methods

Phylogenetic analysis of expansin genes in maize genome

The genomic sequences, coding sequences, and protein sequences of all the expansin family genes in maize were obtained from the MaizeGDB database (https://maizegdb.org/). All protein sequences are compared by the CLUSTAL W model in MEGA11 with a gap opening penalty of 10, a gap extension penalty of 0.1, and other options in system default parameters. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor Joining model of MEGA11, with 1000 iterations of bootstrap analysis. The protein motif was identified by MEME Suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme) with the conservative motif parameter of 10 and other parameters of default. The gene structure annotation (B73 RefGen_v4) was downloaded from MaizeGDB. TBtools v1.068 was used for the data analysis and plot.

Field experiment of 118 maize inbred lines

A total of 118 inbred lines were selected from the 1604 maize panel (Li et al. 2022b). Of the 118 lines, 70 lines were selected based on the genetic structure of 1604 lines to maximize the genetic diversity and 48 lines that were considered represent lines of different heterotic groups or elite lines were also included. All plants were growing under drought and well-watered treatments in the field at three environments: Beijing (2021 and 2022) and Urumqi (2022). All field experiments were watered using drip irrigation system to minimize the error of water in different blocks and monitor the water value in each treatment. For the field experiments in 2021 and 2022 at Beijing, the drought treatments were watered once with 600 m3/ha after sowing and withholding water under a rain shelter. And the well-watered treatments were watered three times during the whole growing stage with 1800 m3/ha and there was no restriction for rain. For the field experiments in 2022 at Urumqi, the well-watered treatments were watered six times during whole growing stage with 900 m3/ha each time and the drought treatments were watered six times with 450 m3/ha each time. All field experiments were single row blocks and three replicates. The rows were set as 3 m length and 0.6 m apart, containing 13 plants. The flowering time was measured according to the method of Liu et al. (2021a). Days to anthesis (DTA) and days to silking (DTS) were calculated from sowing to the date when half of the individuals shed pollen grains and silking in each block, respectively. Anthesis-silking interval (ASI) is the difference between DTA and DTS. The best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) was used to estimate the phenotype by “lmer” function in the R package lme4 based on the data obtained in three environments.

Genotyping and association analysis

The DNA of the 118 inbred lines were extracted from seedling leaves using the CTAB method. First, the genomic SNPs were identified using Maize56K SNP Array. The kinship matrix and principal component analysis (PCA) were identified using the genomic SNPs by TASSEL5 software (Bradbury et al. 2007). The population structure was analyzed by ADMIXTURE (Alexander et al. 2009). Second, the genic region of ZmEXPA5 and its 2.5-kb upstream and 0.5-kb downstream regions were sequenced based on eight overlapped amplicons by PCR and Sanger sequencing. The primer sequences are listed in Table S3. The SNPs and indels of the 118 inbred lines were identified using SnapGene2.3.2. The candidate gene association analysis was conducted by the MLM Q+K model using the TASSEL5 software. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis was performed using Haploview4.1.

Gene expression analysis of ZmEXPA5 in 118 inbred lines

For the field experiment of 118 lines at Beijing in 2022, the emerging silk tissues of three randomly selected individuals in each block were sampled and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen for RNA isolation. Total RNA was extracted using the Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Gene-better). The RNA concentration was measured using the NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the TransScript-Uni One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransScript). The quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix Kit with SYBR Green (Vazyme) and Applied Biosystems QuantStudio3 (ThermoFisher Scientific). The ZmGAPDH was used as an internal reference. The qRT-PCR system conditions were set as follows: hold stage (50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min), PCR stage (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s) 45 cycles, melt curve stage (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, 95°C for 15 s). Three replicates were performed for each RNA sample. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used for data analysis (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). The primers used in the qRT-PCR analysis are in Table S3.

Transcription factor binding site prediction

The 60 bp sequence around INDEL-570, which is the significant associated variant in association analysis, was used for transcription factor binding site prediction by the Transcription Factor Prediction tool in PlantTFDB v5.0 (http://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/). The parameter of species was set as Zea mays and threshold P-value was 1×10−4. And the gene expressions of potential interacting transcription factor genes were obtained from Han et al. (2023) and Walley et al. (2016).

Yeast one hybrid assay

The G/G INDDEL-570 haplotype sequence of AGAAAGAAAAAAAAGTTGCAG and −/− haplotype sequence of AGAAA-AAAAAAAAGTTGCAG were used for yeast one hybrid (Y1H) assay. Three tandem repeats of these sequences were synthesized and recombined into pLacZi vector, respectively. The coding sequence of ZmDOF29 was amplified from B73 cDNA library and cloned into the pB42AD vector to construct the fusion protein of B42 transcription activation domain (AD)-ZmDOF29 driven by the GAL1 promoter. The different combinations of empty or recombinant vectors were co-integrated into the genome of yeast strain EGY48 and selected by growth in medium lacking tryptophan and uracil (SD/-Trp/-Ura). After 3 days’ growth at 28°C, the positive yeast colonies were then transformed on the SD/-Trp/-Ura plates containing X-gal and incubated at 28°C for 3 days to determine the interaction between promoter sequences of ZmEXPA5 around INDEL-570 and the predicted binding protein ZmDOF29.

Dual luciferase assay

Dual luciferase assay was performed to test the activity effect of ZmDOF29 on the G/G and −/− haplotypes of INDEL-570. Three tandem repeats of G/G and −/− haplotype sequences were synthesized and cloned into the pGreenII-0800 vector with the Luc gene to produce the reporter vectors, respectively. The Ren gene driven by the CaMV35S promoter was used as the internal reference. The coding sequence of ZmDOF29 was amplified from B73 cDNA library and cloned into the pGreenII 62-SK vector. The reporter vectors and CaMV35S:ZmDOF29 vector were introduced into GV3101 strain and co-infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. The tobacco leaves were sampled after 3 days and the Luc and Ren activities were measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay Kit (Promega) following the user manual instruction.

Gene expression analysis of ZmEXPA5 under different hormone treatments

According to the candidate gene association analysis results, we selected the two inbred lines H08183 (G/G) and Lv28 (−/−) that harbor drought-tolerant and susceptible haplotypes of INDEL-570 to test the expression of ZmEXPA5 under different plant hormone treatments. Plants were growing in a greenhouse with 28°C/light for 16 h and 23°C/dark for 8 h using the paper roll method. After 2 weeks of germination, the plants were treated with 100 μmol/L auxin (IAA), gibberellin (GA3), abscisic acid (ABA), and brassinosteroid (BR); 50 μmol/L zeatin; and 10μmol/L strigolactone (SL), respectively. The leaves and roots were collected before treatment (0 h) and at 0.5 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after hormone treatment. Three replicates, which contained ten individual plants in each, were used for subsequent RNA extraction and gene expression analysis. The methods of RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and qRT-PCR were the same with the description in the “Gene expression analysis of ZmEXPA5 in 118 inbred lines” section. The primers used in the qRT-PCR analysis are in Table S3.

Subcellular localization of ZmEXPA5-EGFP fusion protein

The coding sequences without terminating codons of the ZmEXPA5 gene were cloned into Acc65I/SalI sites of pCAMBIA1300 vector and generate ZmEXPA5-EGFP fusion genes driven by the CaMV35S promoter. The CaMV35S:ZmEXPA5-EGFP recombinant plasmid and CaMV35S:EGFP empty vector were transferred into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves using Agrobacterium infection. After 48 h of growth, the fluorescence of GFP was collected using LSM960 confocal laser microscopy (ZEISS) under 488 nm bandwidths.

Overexpression transgenic plants and field experiment

The coding sequence of ZmEXPA5 was cloned into the pCAMBIA3301 vector with the modified Ubi1 promoter. The plasmids were transformed into EHA105 Agrobacterium strain and then transformed into the immature embryos of the maize inbred line B104. The T0 plants were self-pollinated and homozygous T2 lines were used for phenotypic tests. The overexpression transgenic lines and the wild-type B104 were planted in the field under drought and well-watered treatment at Urumqi, Xinjiang, in 2022. The well-watered treatments were watered six times during the whole growing stage with 900 m3/ha each time, while the drought treatments were watered six times with 450 m3/ha each time. All field experiments were one row blocks and six replicates. The rows were set as 3 m length and 0.6 m apart, containing 13 plants for each row. The DTA and DTS were recorded for individuals of transgenic and wild-type lines. Grain yield, hundred kernel weight, kernel length, kernel weight, and kernel number per plant were measured for all harvested ears in each block. Silk tissues were sampled for subsequent RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis. The methods of RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and qRT-PCR were the same with the description in the “Gene expression analysis of ZmEXPA5 in 118 inbred lines” section.

Results

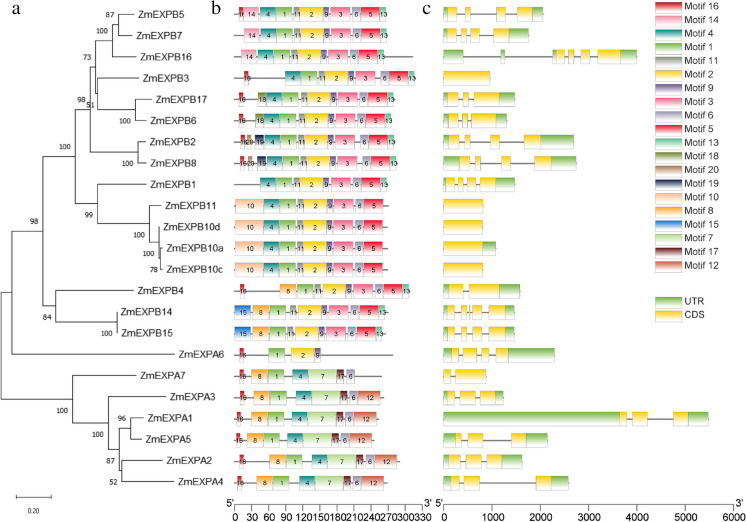

Expansin gene family in maize genome

In the maize genome, 23 expansin genes were identified including 7 α-expansin (EXPA) genes and 16 β-expansin (EXPB) genes (Fig. 1a). The EXPA genes are located on chromosomes 1, 3, 5, 6, 9, and 10, while the EXPB genes are located on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9. The protein length of expansins ranges from 193 to 322 amino acid (Fig. 1b). The EXPA and EXPB genes were highly expressed in developing tissues such as germinating kernel, primary root, root elongation zone, mature pollen, female spikelet, and silk (Table S1). Particularly, ZmEXPA5 has similar gene structure and protein structure with ZmEXPA4 (Fig. 1a). The coding sequence of ZmEXPA5 has three exons and encodes a protein with length of 294 amino acid (Fig. 1c). ZmEXPA5 was highly expressed in silk while ZmEXPA4 showed the highest expression in ear (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Expansin gene family in maize genome. a The phylogenetic tree of maize expansin genes based on the protein sequences. The number on top of the branch means confidence probability based on 1000 bootstraps. b The conserved motifs in protein sequence of expansin identified by MEME. c The gene structure of expansin genes. The green bars, yellow bars, and gray lines present UTRs, exons, and introns, respectively

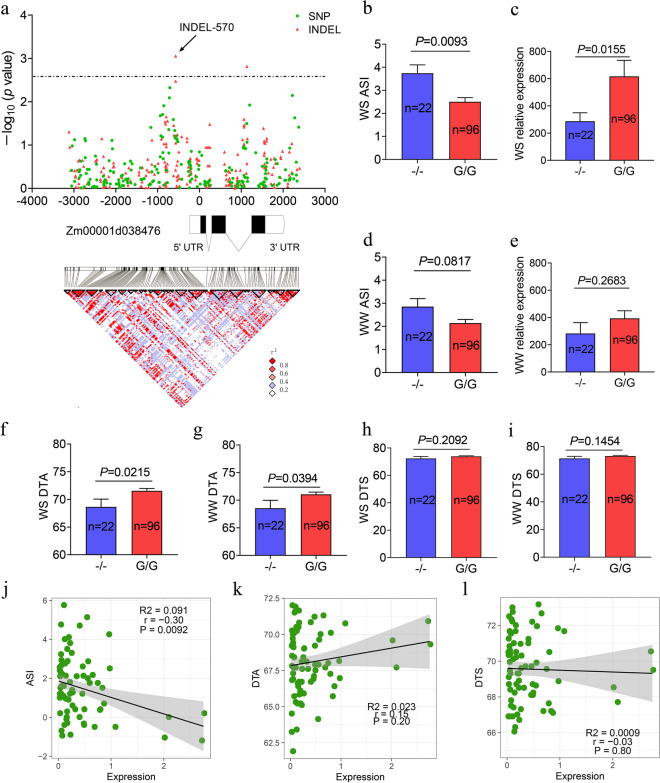

The gene expression variation of ZmEXPA5 is associated with ASI under drought

To identify the correlation between the natural variants of ZmEXPA5 and drought tolerance, we measured the flowering time of 118 maize inbred lines under different water treatments and performed candidate gene association analysis. The heritability (H2) of DTA, DTS, and ASI under different water treatments in three environments was in the range of 0.80 to 0.98 (Table S2). The DTA and DTS of natural population showed delayed and the ASI were increased under drought treatments (Fig. 2a). The ASI was negatively correlated with DTA under well-watered conditions but showed positive correlation with DTS under drought (Fig. 2b). The 6-kb region that includes the 2.5-kb promoter, 3-kb genic, and 0.5-kb downstream region of ZmEXPA5 in the 118 lines was sequenced. A total of 206 SNPs and 244 indels were identified. In addition, 42,137 genomic SNPs were generated by SNP array to identify the population structure of the 118 lines. Association analysis based on the MLM Q+K model revealed the indel at 570 bp upstream of the translation start codon (ATG) or 439 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS), which is named as INDEL-570, showed the highest association signal (P = 8.85×10−4) with the ASI under drought environments (Fig. 3a). The insertion (G/G) and deletion (−/−) haplotypes of INDEL-570 contained 96 and 22 inbred lines, respectively. The insertion haplotypes of INDEL-570 showed significantly (P < 0.05) delayed DTA and decreased ASI than deletion haplotypes (Fig. 3b, f).

Fig. 2.

The phenotypic variation of flowering time of maize natural population under different water conditions. a The density distribution of anthesis-silking interval (ASI), days to anthesis (DTA), and days to silking (DTS) under water stress (WS) and well-watered (WW) conditions. The orange and green areas are distributions under WS and WW conditions, respectively. b Correlation analysis of flowering time under WS and WW conditions. The numbers in the right-up panel are correlation coefficient r. And the *** represents P < 0.001 of correlation test

Fig. 3.

Candidate gene association and gene expression analysis of ZmEXPA5 in 118 inbred lines. a Candidate gene association analysis of the genetic variants around ZmEXPA5 in the 118 maize inbred lines and ASI under drought treatments. The zero point of the X-axis is the start codon (ATG) of ZmEXPA5. The threshold of association analysis is determined by the Bonferroni correction method. The different colors of points present SNP or indel variants. The bars below association result are the gene structure of ZmEXPA5. The black bars, lines, and white bars present exons, introns, and UTRs of ZmEXPA5. In the lower panel, pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis was performed and plotted according to the SNP and indel variants of ZmEXPA5. b–e The ASI and gene expression of ZmEXPA5 between the inbred lines harboring deletion (−/−) or insertion (G/G) haplotypes of the most significant association variant INDEL-570 under well-watered (WW) and water stress (WS) treatments. The statistic test is performed using Student’s t-test. f–i The DTA and DTS of inbred lines with deletion (−/−) or insertion (G/G) of INDEL-570 under different water treatments. j–l The correlation between gene expression of ZmEXPA5 and ASI, DTA, and DTS under water stress treatment. The correlation coefficient r, significance level P, and R2 of linear regression were showed in the plot

As the associated variant INDEL-570 is located in the promoter region of ZmEXPA5, we measured the expression of ZmEXPA5 in the 118 lines under water stress and well-watered treatment. The expression of ZmEXPA5 showed no significant difference between the insertion and deletion haplotypes of INDEL-570 under well-watered treatments (Fig. 3d, e). However, the insertion haplotypes that showed significantly decreased ASI also displayed 2.1-fold higher expression (P < 0.05) of ZmEXPA5 than deletion haplotypes under water stress treatment (Fig. 4b, c). In the lines harboring insertion haplotype, the expression of ZmEXPA5 was 1.6-fold induced by the drought treatment. But the expression ratio of ZmEXPA5 between drought and well-watered treatments showed no significant response in the lines with deletion haplotype. In addition, the expression of ZmEXPA5 was significantly negatively correlated (r = − 0.30, P < 0.01) with ASI under drought treatment (Fig. 3j–l). These results suggested that ZmEXPA5 could influence drought-induced ASI via gene expression variation.

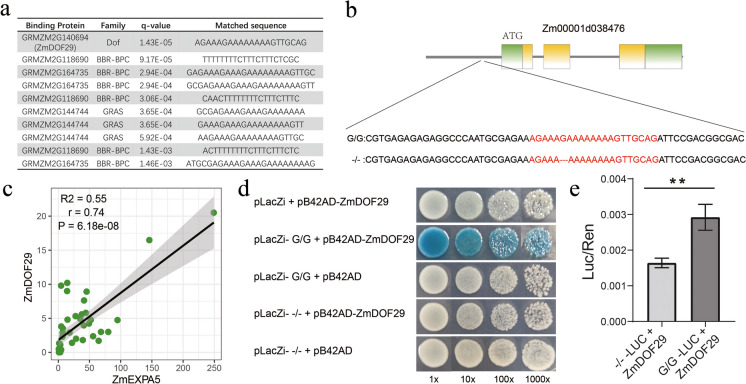

Fig. 4.

Transcription factor ZmDOF29 binds on INDEL-570 variant in the promoter region of ZmEXPA5. a The transcription factor binding sites of the sequence around INDEL-570 were predicted according to the binding site prediction tool on PlantTFDB. The top 10 significant results are shown in the table and the most significant predicted protein is ZmDOF29, whose q-value = 1.43×10−5. b The predicted binding sequence AGAAAGAAAAAAAAGTTGCAG is located on the INDEL-570. The insertion (G/G) of INDEL-570 is drought-tolerant haplotype that showed higher expression of ZmEXPA5 and decreased ASI than deletion (−/−) haplotype under drought environment in the 118 inbred lines. c Correlation analysis showed the gene expression of ZmEXPA5 and ZmDOF29 was significantly positively correlated, with correlation coefficient r = 0.74 and P = 6.188×10−8. And the R2 of linear regression model is 0.55. The gene expression values were obtained from Han et al. (2023) and Walley et al. (2016). d Yeast one hybrid (Y1H) assay of INDEL-570 insertion (G/G) and deletion (−/−) haplotype DNA sequences and ZmDOF29 protein. The yeast transformants were screened on SD/-Trp/-Ura media. The galactosidase activity of each yeast colony was assessed by X-gal staining. e Dual luciferase assay of INDEL-570 insertion (G/G) and deletion (−/−) haplotype DNA sequences and ZmDOF29 protein in leaves of N. benthamiana. Relative luciferase activity is calculated as Luc/Ren. The significant difference is examined by Student’s t-test and ** means P < 0.01

INDEL-570 affects expression of ZmEXPA5 by manipulating the transcription activity of ZmDOF29

To investigate the potential mechanism that INDEL-570 affected gene expression of ZmEXPA5, the transcription factor binding sites of the promoter sequences around INDEL-570 were predicted based on the PlantTFDB database. The result showed the most significant predicted binding transcription factor was ZmDOF29 with binding motif of AGAAAGAAAAAAAAGTTGCAG (Fig. 4a). The INDEL-570 was located on the sixth site of the binding motif (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the gene expression of ZmEXPA5 and ZmDOF29 was compared and correlation analysis showed these two genes had significantly correlated (r = 0.74, P < 0.01) gene expression patterns (Fig. 4c). These results suggest a potential interaction between ZmDOF29 and ZmEXPA5.

Thus, Y1H and dual luciferase assays were performed to validate the regulatory relationship between ZmDOF29 and ZmEXPA5. For Y1H assay, only the insertion haplotype of INDEL-570 in the promoter of ZmEXPA5 showed interaction signal with ZmDOF29. The interaction was absent between deletion haplotype and ZmDOF29 (Fig. 4d). This suggests the INDEL-570 affects the binding ability of ZmDOF29 to the promoter of ZmEXPA5. Further analysis of dual luciferase assay also showed that ZmDOF29 had higher transcription activity to insertion haplotype than deletion haplotype, as the Luc/Ren ratio of G/G-Luc + ZmDOF29 was significantly (P < 0.01) higher than that of −/−-Luc + ZmDOF29 (Fig. 4e).

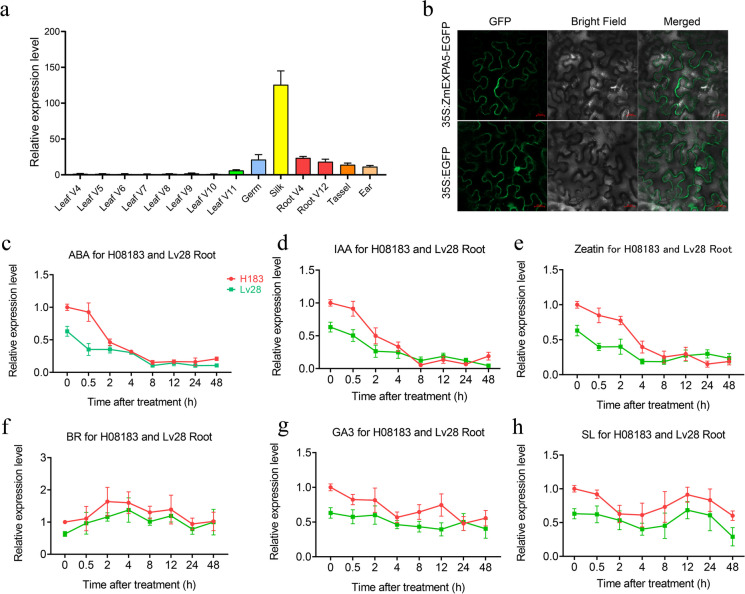

Expression patterns of ZmEXPA5

The gene expression of ZmEXPA5 in different tissues was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Consistent with the previous reports, ZmEXPA5 showed high expression in developing tissues including embryo, root, tassel, and ear and exhibited the highest expression in silk tissue (Fig. 5a). To determine the subcellular localization, we combined ZmEXPA5 with the N-terminal fusion of the EGFP which is driven by the CaM35S promoter. The 35S:ZmEXPA5-EGFP vector was transformed into leaves of tobacco and the ZmEXPA5-EGFP fusion protein was expressed in cell wall, plasma membrane, and cytoplasm (Fig. 5b). To determine the potential regulation patterns that ZmEXPA5 is involved in, we selected the two representative lines H082183 (G/G) and Lv28 (−/−) harboring different haplotypes of INDEL-570 for gene expression analysis under plant hormone treatments. The expression of ZmEXPA5 was decreased under ABA, IAA, and zeatin treatments as early as 2 h after treatments. However, there were no obvious differences between the decreased expression patterns of ZmEXPA5 under ABA, IAA, and zeatin treatments in insertion and deletion haplotypes, while the expression of ZmEXPA5 had no significant changes under GA3, BR, and SL treatments (Fig. 5c–h).

Fig. 5.

Expression patterns of ZmEXPA5. a Gene expression of ZmEXPA5 in different tissues of maize inbred line B73 under normal condition. b Subcellular localization of ZmEXPA5. The upper panel is the CaMV35S:ZmEXPA5-EGFP vector and the lower panel is CaMV35S:EGFP which was used for empty control. The scale bar is 20 μm. c–h The expression of ZmEXPA5 under ABA, IAA, BR, zeatin, G3, and SL treatments in maize inbred lines H082183 and Lv28, which harbors insertion (G/G) and deletion (−/−) haplotypes of INDEL-570, respectively

Overexpression of ZmEXPA5 reduces ASI and increases grain yield

The Ubi1:ZmEXPA5 overexpression vector was build and transformed into the maize inbred line B104. Of the 14 independent homozygous T2 lines, three lines that showed the highest ZmEXPA5 expression were selected for phenotypic characterization in the field. The expression of ZmEXPA5 in OE#2, OE#5, and OE#8 was 15.5-, 88.4-, and 19.5-fold higher than the wild-type line (Fig. 6b), respectively. The morphology including plant height and leaf number had no obvious difference between the transgenic lines and the wild type (Fig. 6a). The ASI of the transgenic lines was significantly (P < 0.01) lower than that of the wild-type line under both drought and well-watered conditions (Fig. 6c, d). The average ASI of OE#2, OE#5, and OE#8 was 5.1, 4.9, and 5.3 days, respectively, under drought treatment (Fig. 6c), while the average ASI was 7.7 days in the wild-type line under drought. In addition, DTA of the transgenic lines was significantly delayed than the wild-type line under both drought and well-watered treatments (Fig. 6g, h). By contrast, no significant difference in DTS was observed between the transgenic lines and the wild-type line under drought or well-watered conditions (Fig. 6e, f).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of flowering time between the ZmEXPA5 overexpression transgenic lines and the wild-type line. a Morphology of the three independent transgenic lines OE#2, OE#5, and OE#8 and the wild-type (WT) line B104 under normal condition. The scale bar in photo is 10 cm. b The gene expression of ZmEXPA5 in silk tissues of different transgenic lines. The OE#2, OE#5, and OE#8 that showed the highest ZmEXPA5 expression were selected for phenotypic analysis. **: P < 0.01 in Student’s t-test. c–h The ASI, DTS, and DTA of the transgenic lines and the wild-type line under water stress (WS) or well-watered (WW) conditions. The statistic test was performed by Student’s t-test

The differences of grain yield and related traits between the transgenic and wild-type lines were also identified. Results revealed that the grain yield per plot and grain yield per plant of the transgenic lines were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than of the wild-type line under both drought and well-watered conditions (Fig. 7). The grain yield per plot of OE#2, OE#5, and OE#8 was 234.3, 225.9, and 224.2 g under drought and 286.6, 302.8, and 306.6 g under well-watered conditions, respectively, while the grain yield per plot of the wild-type line B104 was 162.1 g under drought and 215.9 g under well-watered conditions (Fig. 7a, g). In addition, the grain yield per plant of OE#2, OE#5, and OE#8 was 21.8, 22.1, and 21.3 g under drought and 25.7, 25.1, and 26.4 g under well-watered conditions, respectively, while the grain yield per plant of the wild-type line was 15.9 g under drought and 19.6 g under well-watered conditions (Fig. 7b, h). The kernel number per plant of the three OE lines was significantly increased than of the wild-type lines under both drought and well-watered environments (Fig. 7f, l). We also measured the one hundred kernel weight, kernel length, and kernel width and these traits showed no significant difference between the transgenic and wild-type lines (Fig. 7c–e and i–k). These results reveal the overexpression of ZmEXPA5 reduced the ASI and improved grain yield owing to increased kernel number under both drought and well-watered conditions.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of grain yield and related traits between the ZmEXPA5 overexpression transgenic lines and the wild-type line. a–f Grain yield per plot, grain yield per plant, one hundred kernel weight, kernel width, kernel length, and kernel number per ear of transgenic and wild-type (WT) lines under water stress (WS) condition. g–l Grain yield and related traits of the transgenic lines and the WT line under well-watered condition. The statistic test was performed by Student’s t-test

Discussion

Expansins, also known as cell wall relaxation proteins, participate in regulating plant cell wall extension and relaxation and play important roles in plant development such as seed germination (Chen et al. 2020), fruit ripening (Mayorga-Gomez and Nambeesan 2020), pollen tube development (Liu et al. 2021b), and yield formation (Calderini et al. 2021). Expansin proteins can break the non-covalent bonds between cellulose and hemicellulose and release the mechanical tension of cell wall (Cosgrove 2021). McQueen-Mason et al. (1992) first identified two expansins in the cell wall of cucumber and named them CsEXP1 and CsEXP2. The expansin genes have been isolated in a variety of plants, include Arabidopsis (Abbasi et al. 2021), soybean (Zhu et al. 2014), rice (Sampedro et al. 2005), maize (Zhang et al. 2014), poplar (Sampedro et al. 2006), and grape (Dal Santo et al. 2013). In maize, expansin genes are highly expressed in developing tissues (Table S1), implying their roles in plant growth. In the present study, we cloned the maize α-expansin gene ZmEXPA5. ZmEXPA5 were highly expressed in silk, root elongation zone, and internode. And the protein product of ZmEXPA5 is located in the cell wall, plasma membrane, and cytoplasm (Fig. 6).

Cumulative evidences showed that expansin genes are able to regulate stress tolerance by different pathways. For example, the RhEXPA4 overexpression Arabidopsis plants showed higher germination rate and survival rate under salt stress and ABA treatment. Further analysis revealed that the RhEXPA4 overexpression plants had more compact cells with fewer stomata in leaf and enhanced drought tolerance (Lu et al. 2013). The TaEXPA2 overexpression wheat exhibited a more drought-tolerant phenotype under drought stress, while the RNAi knock-down plants showed drought sensitivity. The overexpression lines had more lateral roots, higher expression of ROS scavenging genes, and improved antioxidant capacity (Yang et al. 2020). GhEXLB2 overexpression cotton plants had longer primary roots and hypocotyls, lower H2O2 and malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and higher water use efficiency (WUE), soluble sugar and chlorophyll content, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD) under drought stress (Zhang et al. 2021b). The overexpression of AtEXPA18 in tobacco plants showed significant improvements in root dry weight and had larger area of abaxial epidermal cells compared to wild type under drought (Abbasi et al. 2021). The EaEXPA1 overexpression transgenic plants had significantly higher photosynthetic efficiency, relative water content, cell membrane thermostability, and chlorophyll content than wild-type plants (Narayan et al. 2021). In maize, Liu et al. (2021a) found that drought-induced expression of ZmEXPA4 significantly reduced ASI than wild-type plants under drought. In the present study, we provide a novel example that the overexpression of ZmEXPA5 reduced ASI and increased grain yield under drought (Figs. 6 and 7). And a natural variant in the promoter region of ZmEXPA5 could regulate the drought-induced ASI by manipulating its expression (Figs. 3 and 4).

One critical difficulty of drought tolerance breeding is to narrow the gap of grain yield under different water conditions without yield penalty under optimal environments, while many drought tolerance–related genes functioned as regulators of the trade-off between stress adaptation and growth. The knockout mutant plants of DRESH8 conferred enhanced drought tolerance while the grain yield was 5 to 14% lower than the wild-type lines (Sun et al. 2023). The overexpression of drought tolerance allele of ZmSRO1d protected grain yield under drought via activating ZmRBOHC and promoting stomatal closure but caused yield loss under optimal conditions. And loss-of-function mutant plants of ZmRBOHC displayed increased grain yield under well-watered conditions and less drought tolerance (Gao et al. 2022). One effective strategy to solve this limitation in molecular breeding is to create a flexible expression pattern of drought tolerance genes by modification of promotors. The constitutive overexpression lines of ZmDRO1 displayed weaker growth than wild-type lines, while the ABA-induced ZmDRO1 transgenic lines showed more downward root and higher grain yield under drought without obvious agronomic trait changes under well-watered conditions (Feng et al. 2022). The expressions of ZmEXPA4 were two-fold higher under drought than well-watered conditions in the drought-inducible transgenic lines, which showed significantly reduced ASI under drought conditions (Liu et al. 2021a). Our results showed that the constitutive overexpression of ZmEXPA5 reduced the ASI and improved grain yield by increasing kernel number under drought conditions. And possibly due to the relatively large ASI of the wild-type line B104, the overexpression transgenic lines also displayed enhanced grain yield due to shorter ASI than the wild-type lines under well-watered conditions (Figs. 2 and 3). This result suggests the promising value of ZmEXPA5 in further molecular breeding for drought tolerance in maize. However, the molecular mechanism of ZmEXPA5 in regulating drought-induced ASI cannot be fully explained based on the results in the present study. We proposed a hypothesis that the overexpression of ZmEXPA5 enhanced the development and competition of energy or nutrition in silk against tassel, or prolong the vegetative growth stage and delay flowering time based on pathways that specifically affect stem apical meristem (SAM).

Collectively, this study provides a promising candidate gene for maize drought tolerance breeding due to its positive impact of grain yield under both drought and well-watered environments.

Supplementary Information

(XLSX 18 kb)

Author contribution

XL, YL, YL, and TW conceived and designed the experiment. KT, YL, and YH performed most of the experiments and analyzed the data. YL, DZ, CL, GH, YS, and YS carried out the field experiment. KT, YH, YL, and XL wrote and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the national key research and development program of China (2021YFD1200705, 2016YFD0101803, and 2017YFD0300405).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Keyu Tao, Yan Li and Yue Hu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yuncai Lu, Email: luyuncai@hlju.edu.cn.

Xuyang Liu, Email: liuxuyang@caas.cn.

References

- Abbasi A, Malekpour M, Sobhanverdi S. The Arabidopsis expansin gene (AtEXPA18) is capable to ameliorate drought stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(8):5913–5922. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury PJ, Zhang ZW, Kroon DE, et al. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(19):2633–2635. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce WB, Edmeades GO, Barker TC. Molecular and physiological approaches to maize improvement for drought tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2002;53(366):13–25. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.366.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderini DF, Castillo FM, Arenas MA, et al. Overcoming the trade-off between grain weight and number in wheat by the ectopic expression of expansin in developing seeds leads to increased yield potential. New Phytol. 2021;230(2):629–640. doi: 10.1111/nph.17048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LJ, Zou WS, Fei CY, et al. α-Expansin EXPA4 positively regulates abiotic stress tolerance but negatively regulates pathogen resistance in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59(11):2317–2330. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SK, Luo YX, Wang GJ, et al. Genome-wide identification of expansin genes in Brachypodium distachyon and functional characterization of BdEXPA27. Plant Sci. 2020;296:110490. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Expanding wheat yields with expansin. New Phytol. 2021;230(2):403–405. doi: 10.1111/nph.17245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Santo S, Vannozzi A, Tornielli GB, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the expansin gene superfamily reveals grapevine-specific structural and functional characteristics. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e62206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng XJ, Jia L, Cai YT, et al. ABA-inducible DEEPER ROOTING 1 improves adaptation of maize to water deficiency. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022;20(11):2077–2088. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HJ, Cui JJ, Liu SX, et al. Natural variations of ZmSRO1d modulate the trade-off between drought resistance and yield by affecting ZmRBOHC-mediated stomatal ROS production in maize. Mol Plant. 2022;15(10):1558–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfray HCJ, Beddington JR, Crute IR, et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science. 2010;327(5967):812–818. doi: 10.1126/science.1185383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Rico-Medina A, Cano-Delgado AI. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science. 2020;368(6488):266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz7614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han LQ, Zhong WS, Qian J, et al. A multi-omics integrative network map of maize. Nat Genet. 2023;55(1):144–153. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao LY, Liu XY, Zhang XJ, et al. Genome-wide identification and comparative analysis of drought related genes in roots of two maize inbred lines with contrasting drought tolerance by RNA sequencing. J Integr Agri. 2020;19(2):449–464. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62660-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler NK, Bowman A, Carey RE, et al. Expansin gene loss is a common occurrence during adaptation to an aquatic environment. Plant J. 2020;101(3):666–680. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Guan H, Jing X, et al. Genomic insights into historical improvement of heterotic groups during modern hybrid maize breeding. Nat Plants. 2022;8(7):750–763. doi: 10.1038/s41477-022-01190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XD, Gao YQ, Wu WH, et al. Two calcium-dependent protein kinases enhance maize drought tolerance by activating anion channel ZmSLAC1 in guard cells. Plant Biotechnol J. 2022;20(1):143–157. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu BX, Zhang B, Yang ZR, et al. Manipulating ZmEXPA4 expression ameliorates the drought-induced prolonged anthesis and silking interval in maize. Plant Cell. 2021;33(6):2058–2071. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Xu LA, Lin H, et al. Two expansin genes, AtEXPA4 and AtEXPB5, are redundantly required for pollen tube growth and AtEXPA4 is involved in primary root elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes. 2021;12(2):249. doi: 10.3390/genes12020249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobell DB, Roberts MJ, Schlenker W, et al. Greater sensitivity to drought accompanies maize yield increase in the US Midwest. Science. 2014;344(6183):516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.1251423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PT, Kang M, Jiang XQ, et al. RhEXPA4, a rose expansin gene, modulates leaf growth and confers drought and salt tolerance to Arabidopsis. Planta. 2013;237(6):1547–1559. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1867-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao HD, Wang HW, Liu SX, et al. A transposable element in a NAC gene is associated with drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8326. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayorga-Gomez A, Nambeesan SU. Temporal expression patterns of fruit-specific α-EXPANSINS during cell expansion in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02452-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason SJ, Durachko DM, Cosgrove DJ. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plants. Plant Cell. 1992;4(11):1425–1433. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.11.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan JA, Chakravarthi M, Nerkar G, et al. Overexpression of expansin EaEXPA1, a cell wall loosening protein enhances drought tolerance in sugarcane. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;159:113035. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.113035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro J, Carey RE, Cosgrove DJ. Genome histories clarify evolution of the expansin superfamily: new insights from the poplar genome and pine ESTs. J Plant Res. 2006;119(1):11–21. doi: 10.1007/s10265-005-0253-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro J, Lee Y, Carey RE, et al. Use of genomic history to improve phylogeny and understanding of births and deaths in a gene family. Plant J. 2005;44(3):409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XP, Xiang YL, Dou NN, et al. The role of transposon inverted repeats in balancing drought tolerance and yield-related traits in maize. Nat Biotechnol. 2023;41:120–127. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T, Wang SH, Yang SP, et al. Genome assembly and genetic dissection of a prominent drought-resistant maize germplasm. Nat Genet. 2023;55:496–506. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01297-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuberosa R, Salvi S, Sanguineti MC, et al. Mapping QTLs regulating morpho-physiological traits and yield: case studies, shortcomings and perspectives in drought-stressed maize. Ann Bot. 2002;89:941–963. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley JW, Sartor RC, Shen ZX, et al. Integration of omic networks in a developmental atlas of maize. Science. 2016;353(6301):814–818. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Liu SX, et al. Genetic variation in ZmVPP1 contributes to drought tolerance in maize seedlings. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1233–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng.3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Fen H, Wu D, et al. Using high-throughput multiple optical phenotyping to decipher the genetic architecture of maize drought tolerance. Genome Biol. 2021;22(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02377-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JJ, Zhang GQ, An J, et al. Expansin gene TaEXPA2 positively regulates drought tolerance in transgenic wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plant Sci. 2020;298:110596. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WN, Guo ZL, Huang CL, et al. Combining high-throughput phenotyping and genome-wide association studies to reveal natural genetic variation in rice. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5087. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BY, Chang L, Sun WN, et al. Overexpression of an expansin-like gene, GhEXLB2 enhanced drought tolerance in cotton. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;162:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wu JF, Sade N, et al. Genomic basis underlying the metabolome-mediated drought adaptation of maize. Genome Biol. 2021;22(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02481-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Yan HW, Chen WJ, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of maize expansin genes expressed in endosperm. Mol Genet Genomics. 2014;289(6):1061–1074. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0867-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XJ, Liu XY, Zhang DF, et al. Genome-wide identification of gene expression in contrasting maize inbred lines under field drought conditions reveals the significance of transcription factors in drought tolerance. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0179477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Wu NN, Song WL, et al. Soybean (Glycine max) expansin gene superfamily origins: segmental and tandem duplication events followed by divergent selection among subfamilies. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu ZH, Zhang FT, Hu H, et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet. 2016;48(5):481–487. doi: 10.1038/ng.3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX 18 kb)