Abstract

Natural fiber is a viable and possible option when looking for a material with high specific strength and high specific modulus that is lightweight, affordable, biodegradable, recyclable, and eco-friendly to reinforce polymer composites. There are many methods in which natural fibres can be incorporated into composite materials. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the physico-chemical, structural, thermal, and mechanical properties of Acacia pennata fibres (APFs). Scanning electron microscopy was used to determine the AP fibers' diameter and surface shape. The crystallinity index (64.47%) was discovered by XRD. The irregular arrangement and rough surface are seen in SEM photos. The findings demonstrated that fiber has high levels of cellulose (55.4%), hemicellulose (13.3%), and low levels of lignin (17.75%), which were determined through chemical analysis and validated by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). By using FTIR, the functional groups of the isolated AP fibers were examined, and TG analysis was used to look into the thermal degrading behaviour of the fibers treated with potassium permanganate (KMnO4) Due to their low density (520 kg/m3) and high cellulose content (55.4%), they have excellent bonding qualities. Additionally, tensile tests were used for mechanical characterisation to assess their tensile strength (685 MPa) and elongation.

Subject terms: Civil engineering, Plant ecology

Introduction

Our living planet Earth is the source of abundant wealth and resources. It provides shelter for over seven million species of plants and animals. Today's diverse cellulose fibers, which have evolved over the past few decades and include flax, hemp, sisal, cotton, kenaf, jute, bamboo, coconut, and date palm, provide a variety of advantages over synthetic fibers (mostly glass, carbon, and plastic) due to their renewable nature1, 2. A number of natural fiber materials can be distinguished by their place of origin in nature. According to specific classifications made by researchers3–8 these materials fall into three categories: fibers produced from animals, minerals, and plants. These fibers are used in a variety of composite material manufacturing processes9–13. In comparison to standard reinforcing materials, natural fibres have greater thermal and acoustic insulating qualities, an acceptable specific strength, cheap cost, and low density14–18. The maturity and origin of the plant, as well as the methods and techniques used to extract the fiber from the stem, still affect the mechanical properties of the fibers19. For every good alternative material without sacrificing the mechanical properties of the fiber, these are some better fiber-yielding plants that are reasonably priced. Acacia pennata (AC) is one such plant, and it is most readily available in tropical areas of India. In contrast, natural fibers were safe, renewable, biodegradable, eco-friendly, and affordable with high specific strength20, 21. Ripples of applications are found in natural fibers from household little equipment’s to aviation. It is because of the efficient properties possessed by these natural composites like light weight, high aspect ratio, low density, soundproof, good thermal and mechanical properties, biodegradability etc.

According to the literature review, natural fibers will become more significant in the future since they are readily available, recyclable, and environmentally friendly22. For automotive applications, polymer composites with various fillers and / or reinforcements are often employed. In order to ensure that the overall cost of the vehicle is lower and that the automobile manufacturing process is more sustainable, numerous such composites have recently been created for use in interior and exterior sections of cars23, 24. The usefulness of a fiber for commercial purposes is decided by features such as length, strength, pliability, elasticity, abrasion resistance, flexibility, etc., aside from economic considerations. Younger fibers from plants tend to be stronger and more elastic than the older ones25, 26. The cellulose is the main content of fibers which corresponds to the crystalline nature of the fibers and the presence of hemicellulose, pectin, lignin should be wiped or reduced by processing for improvements. Also, the antibacterial property is a noted one. Animal, mineral, and plant fibers are specifically the three groups into which natural fibers fall27. The utilisation of natural fibres for the purpose of filling and reinforcing thermoplastic polymers is currently the most prevalent method of reinforcement in today's world. Tensile strength is the most crucial mechanical characteristic of natural fibers that makes them ideal for creating composite materials. Most naturally occurring fibers fall short in the hydrophilic department, which results in poor chemical resistance, subpar mechanical qualities, and porous structures that restrict the engineering uses of these materials28, 29. When choosing a specific fibre to be utilised in a composite material or in any other industrial application, the density, young's modulus, elongation, and stiffness are other crucial parameters that must be taken into account30–32. Natural fibres make excellent insulation against heat, sound, and electricity. They are also easily burnable and biodegradable33. For instance, composites have been utilised in bumpers, roofs, doors, panels, seats of cars, buses, and other vehicles in the automotive sector. Researchers are now interested in improving mechanical qualities like compression, tensile, flexural, or impact strength, as well as wear behaviour, which represent the great achievement of good materials34. Particularly, composite materials are being created and modified in an effort to enhance existing products as well as to offer new ones in a sustainable and ethical manner35.

The goal of the current study is to examine and compare the physical, chemical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological analysis of Acacia pennata fibers (APFs) with that of other probable natural fibres mentioned in the literature. In order to determine the APFs bonding properties, the surface roughness of the material was also measured using a three-dimensional non-contact surface roughness tester. To determine the contents of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, pectin, wax, moisture, and ash, a chemical analysis was carried out. In addition, thermogravimetric analysis, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) examinations were used to analyse the crystalline phases and compounds.

Materials and methods

Materials

The Acacia pennata fiber was treated using destilled water, NaOH pellets, and a potassium permanganate pellets in acetone. This was acquired from Premier Chemicals in Nagercoil, Kanniyakumari district, Tamil Nadu, India.

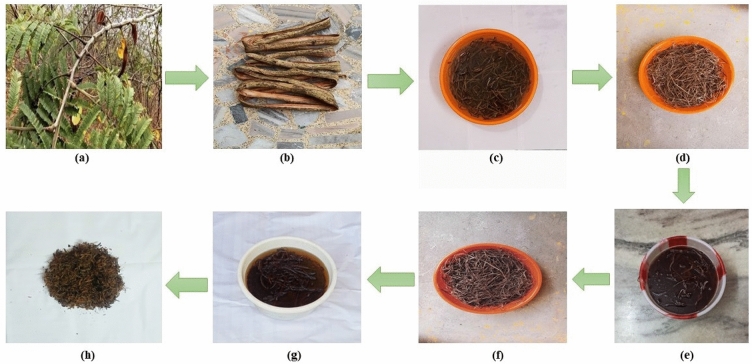

Extraction method of Acacia pennata fiber from the plant

Acacia pennata is a large scrambling or climbing shrub. It can grow up to a height of almost 100 m. Its trunk and branches are prickly and smooth. The stem of Acacia pennata fibers were gathered from Tamilnadu-Kerala border (near Panachamoodu and Vellarada area). The fiber has been separated from its bark of the plant and then allowed to dry at ambient temperature (27 °C) for few days. The dried fibers are treated with distilled water for about 20 min for microbial degradation before treating the fiber with alkali (NaOH). The dried fiber sections were pre-treated with NaOH aqueous solution and the potassium permanganate (KMnO4) solution was prepared with the help of acetone and KMnO4 pellets. The importance of this treatment for improving surface properties was also addressed in depth. This allowed us to reduce the hydrophilic capacity and increase the adhesion between the fibers and polymers36. The fibers were soaked in this (0.1 M NaOH) solution for 20 min. The fibers were removed after 20 min and dried for 10 to 15 days at room temperature (27 °C). After drying, the fiber sections are immersed in KMnO4 solution for about 15 minitues37. Then, these fibers were allowed to dry at ambient temperature. The dried AP fibers were chopped into powder form or broken into little fiber strips based on the need of analysis. KMnO4 treated AP fibers were packed in zip-lock cover and store in room temperature. Figure 1 shows the pictures of Acacia pennata plant fiber and its chemical treatments.

Figure 1.

Images of an (a) AP plant, (b) AP stem fiber, (c) water retting, (d) untreated dried AP fibers, (e) AP fibres treated with NaOH. (f) Dried NaOH treated AP fibers, (g) AP fibres treated with KMnO4, (h) Dried KMnO4 treated AP fibers.

Experimental techniques

Powder XRD technique

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) is a method for determining if a material is crystalline or amorphous38. It is a quick analytical method that can reveal the size of unit cells and is mostly used to determine a crystalline material's phase. Copper (Cu) is the most common target material for powder x ray diffraction, and the powder sample were subjected to X-ray diffraction using CuKα (i.e., CuKα is the emission of copper) radiation with a wavelength of 1.5406 nm in a Bruker x-ray diffractometer. A 2θ range X-ray diffraction examination was performed with angles ranging from 3° to 70°. In the spectrum of the APFs, the integrated intensities of the Bragg peaks were recognised, and their crystallinity indices were calculated. The crystallinity index (CI) of the natural fiber was measured using the traditional peak height technique developed by Segal et al39.

| 1 |

where, H002 is the height of the crystalline peak situated around 22° and 23°; Ham is the height of amorphous peak situated around 14° and 16°.

The crystallite size (CS) of the natural fiber were calculated through the following equation40;

| 2 |

where, β is the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) value of peaks; θ is the Bragg’s angle41.

FTIR techniques

A crucial method for locating significant groups is Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy42. “Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two” FTIR spectrometer with a scan rate of 32 per minute, a resolution of 2 cm−1, and a wave number range between 4000 cm−1 and 400 cm−1 were used to obtain the FTIR spectra of the APFs.

SEM techniques

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) with EDS is used to investigate the topography and morphology of the surfaces of materials as well as biological samples. EDS is used to facilitate elemental recognition. A concentrated electron beam is used to scan a sample's surface in a scanning electron microscope (SEM), which creates images of the sample. The spatial correlations between the various matrices' and reinforcement fibers' constituent parts have been clarified by SEM studies43. Using a scanning electron microscope, the surface morphology of APFs was studied (JEOL JSM-6390LV)44–46. Magnification of the JEOL JSM-6390LV is on the order of 3,00,000 × with high resolution 3.0-nm, where fine details of the specimens can be observed.

Thermo-gravimetric techniques

Thermo-gravimetric analysis by Perkin Elmer was used to access the thermal stability behaviour of APFs. The curve plots the temperature difference between the reference material and the sample material against time or temperature. The amount and rate of change in a material's weight as a function of temperature or time in an environment of nitrogen, helium, air, another gas, or in a vacuum are measured using thermo-gravimetric analysis (TG). The method can identify materials that experience weight gains or loss as a result of oxidation, dehydration, or other processes47.

Density using pycnometer

The thickness (density) of natural fibers is frequently measured with a pycnometer48. The fiber sample is simply dried at room temperature before use to remove moisture49. If moisture remains in the fiber material, a vacuum desiccator can be employed to eliminate it completely. The samples are then thoroughly pulverised and placed in the pycnometer to measure the density50. Toluene is used as an immersion solvent when measuring the densities of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fibres in accordance with ASTM D578-89 standard. The fibres must be soaked in toluene for at least two hours before being weighed to assess their density. Density of APF is derived from;

| 3 |

where, m1—mass of dry empty pycnometer (g); m2—mass of pycnometer + fiber (g); m3—mass of pycnometer + toluene (g); m4—mass of pycnometer + toluene + fiber (g); ρt—density of toluene (0.867 g/cm3); ρf—density of natural fiber in g/cm351–57.

CHNS (elemental) analysis techniques

Using a CHNS analyzer, model Elementar Vario EL III Instruments based on the principle of Dumas's method58, which involves the complete and quick oxidation of the sample by "flash combustion," one may determine the percentages of C, H, N, S, (carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur and oxygen elements) in organic compounds. To provide carbonate and organic carbon and to get a general idea of the composition of the organic matter (i.e., to distinguish between marine and terrigenous sources, based on total organic carbon / total nitrogen [C/N] ratios), elemental analyses of total nitrogen and carbon (and sulphur) are conducted.

Tensile strength analysis

There are various reasons to undertake tensile tests. Typically, Zwick/Roell59 specimens are used for the tensile test60. The maximum stress that the material can withstand or the stress required to generate substantial plastic deformation are two ways to assess the strength of an object of interest. A computerised tensile testing machine was used for the tensile testing analysis. The tensile mechanical characteristics of a material are described in depth via tensile testing and also these tests were performed with ASTM-D412 international standards59. These characteristics can be represented graphically as a stress/strain curve to display information such as the point at which the material failed and to provide information on characteristics such the elastic modulus, strain, and yield strength61. The tests are conducted at a temperature of 21 °C, a cross-head speed of 30 mm/min, and a relative humidity of 65 ± 2%62. To confirm the accuracy of the tensile test, 10 fibers, each 50 mm long, are tested63–71. Records are kept of the average tensile strength, elongation at break, and strain rate. The following empirical relationship governs the tensile strength of the AP fibers;

| 4 |

where; F is the force in Newtons, A is cross-sectional area in mm2 and T is the tensile strength in MPa72, 73.

Stress–strain curves are used to evaluate the mechanical characteristics of AP fibers, including their tensile strength and percentage of elongation70, 74. A microscope is used to conduct a comprehensive longitudinal direction of the chosen acacia pennata fibers in order to measure their average diameter. Additionally, from the SEM images, the thickness of the fibers is calculated using the ImageJ software59. Nearly the same diameter was obtained by both techniques. The shape of APFs cross section is round53, 75–77. The angle formed by the helical winding orientations of cellulose microfibrils is known as the microfibril angle (MFA). A plant fibers strength and stiffness are often affected by the amount of cellulose and the spiral-shaped wink. The Global deformation equation is used to determine the microfibrillar angle (α) of AP fibers.

| 5 |

where ϵ—strain, α—micro-fibril angle (degree) and (∆L/Lo)—ratio of elongation50, 52–54, 78, 79.

The term “Youngs modulus” is used to describe a material's resistance to elastic deformation under load. It displays the strength of a material, to put it another way.

| 6 |

where, F—applied force; E—young’s modulus (GPa) of the fiber; A—cross-sectional area of the fiber and ∆L/Lo—ratio of elongation74.

The elongation at break is the ratio of the modified length to the original length when a test specimen is fractured. It demonstrates how naturally occurring plant fiber may withstand changes without breaking. It is possible to calculate the elongation at break of the AP fiber in accordance with ISO/IEC 17,02580, 81 tensile test.

Chemical analysis test

Chemical analysis tests were used to identify the chemical composition of natural fibers and how it affected their mechanical qualities. To study the percentages of chemical compositions (cellulose, hemicelluloses, lignin, pectin, wax, and ash) which present in the natural fiber using chemical analysis. These are the primary components of natural fibers. All chemical analysis tests were performed in accordance with ASTM-D3822 and IS199 international standards82. Both natural and synthetic fibers are currently used in the production of engineering materials. As a result, their mechanical and thermal characteristics depend on the environment. Therefore, in-depth research must be done to analyse the characteristics of natural fibers.

Specimen collection

The Acacia pennata plant has spread and grown throughout Kerala and Tamil Nadu in India. Acacia pennata plant for the research purposes are collected from the authors farm at Panchamoodu and Vellarada.

Guidelines and regulations

All testing was performed in accordance with the relevant ISO standards. The methods and procedures used were compliant with the guidelines and regulations outlined in the ISO standard to ensure accurate and reliable results.

Results and discussion

Powder XRD analysis

Figure 2 depicts the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the untreated and KMnO4-treated AP fibers. It (untreated APF) shows the crystalline peak (22.59°) on the crystallographic plane (002) and amorphous peak (15.25°) on the lattice plane (110), which demonstrates the semi-crystalline nature77. This is because hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin are present. Two well-defined diffraction peaks are observed in KMnO4 treated APFs around 2θ = 22.73° and the amorphous peak at 2θ = 15.37° include lignin, pectin, hemicellulose, and amorphous cellulose, which contains a larger percentage of amorphous fraction83. The crystallinity index of KMnO4 treated fiber was determined as 64.47%. The high crystallinity index of AP fiber was caused by the efficient removal of contaminants and hemicellulose. It was slightly increased when compared to untreated (46.52%) AP fiber. The CI of permanganate treated AP fibers are significantly greater than Kapok (45%) fiber and substantially lower than crushed guadua (65.3) fiber, jute (71%) and hemp (88%) fiber31, 84. However, using the well-known scherrer formula, the crystallite size (CS) of the KMnO4 treated APFs was found to be 6.75 nm and it was higher than that of untreated (1.9 nm) AP fiber. The crystalline size value is lower than that of ramie fibres (16 nm) and higher than that of cotton fibers (5.5 nm), tamarindus indica fruit fibers (5.73 nm), ferula communis (1.6 nm), and carbon fibers (0.669 nm)85, 86. Table 1 represents the comparison of CI and CS values of raw and KMnO4 treated APFs with other natural fibers.

Figure 2.

PXRD patterns of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fiber.

Table 1.

Comparison table for CI and CS values of raw and KMnO4 treated APFs with other natural fibers.

| Fiber name | CI (%) | CS (nm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated AP | 46.52 | 1.9 | Present study |

| KMnO4 treated AP | 64.47 | 6.75 | Present study |

| Ceiba pentandra | 57.94 | 22.48 | 87 |

| Celosia argentea | 52.54 | 3.46 | 88 |

| Bauhinia purpurea | 65.61 | 2.57 | 89 |

| Acacia nilotica | 44.82 | 3.21 | 90 |

| Prosopis juliflora | 46 | 15 | 69 |

| Sida cordifolia | 56.92 | 18 | 91 |

| Leucaena leucocephala | 63.10 | 2.33 | 92 |

FTIR analysis

Figure 3 displays the FTIR spectra of the AP fiber that had been treated with KMnO4. From graph, the hydrogen-bonded OH stretching group of the water molecules is responsible for the prominent peak at 3435 cm−1. The CH stretching vibrations in the cellulose and hemicellulose components are visible in the peak at 2924.41 cm−1. The sharp and medium peak, which is associated with the C=H stretching, lies at a height of 1645.35 cm−193. A hydrogen bond may be seen at the peak at 1420.62 cm−1. The C = O stretching of lignin is what causes the absorption band at 1030.61 cm−1 to exist. The presence of saline content may be seen in the lower peak at 778.48 cm−1. The peak at 629.07 cm−1 demonstrates the region of –OH bending was found at out of plane, proving that the chemical analysis's findings are supported by the elimination of lignin and hemicelluloses from the KMnO4 treated APFs. The FTIR vibrational band assignments of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fibers were shown in Table 2.

Figure 3.

FTIR Spectra of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fiber.

Table 2.

FTIR Vibrational band assignments of untreated KMnO4 treated AP fibers.

| Wave number (cm−1) | Vibrational band assignments | |

|---|---|---|

| KMnO4 treated APF | Untreated APF | |

| – | 3787.33 | –OH Stretching in Hydrogen bond93 |

| 3435 | 3437.02 | –Hydrogen bonded of OH stretching in cellulose and/or hemicelluloses3, 94–97 |

| 2924.41 | 2923.10 | –CH Stretching of Cellulose97–99 |

| 1645.35 | – | –C=O Stretching of α keton100 |

| – | 1631.28 | –CC stretching of lignin93 |

| 1420. 62 | – | –Existence of CH bond94, 96, 101 |

| – | 1383.68 | –Stretching in CH bond97, 101 |

| – | 1110.42 | –COC pyranose ring skeletal vibration of cellulose102 |

| 1030.61 | – | –C=O stretching of lignin95, 103 |

| 778.48 | 776.35 | Presence of saline content58, 82 |

| 629.07 | 618.17 | Out of plane of –OH bonding58, 82 |

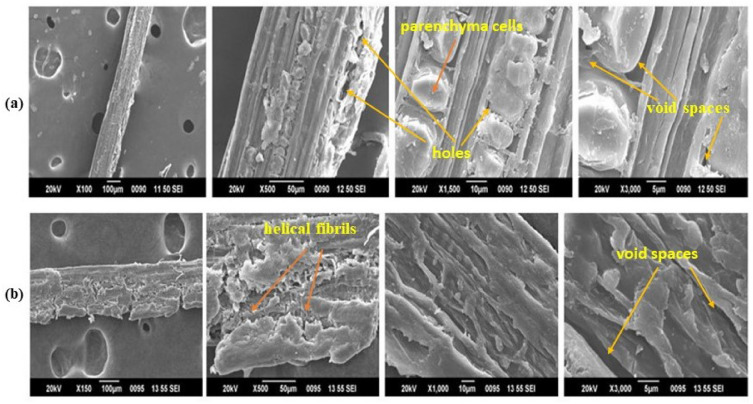

SEM analysis

A test method called scanning electron microscopy uses an electron beam to magnify and examine a material. The surface shape of the untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fiber is shown in Fig. 4a,b. It was observed that the APF treated with KMnO4 had a rough and disorganised surface shape compared with untreated APFs. It reveals that the hemicellulose content (white layer on the surface of untreated SEM image), void spaces, holes, parenchyma cells and few impurities are visible on its surface. To enhance the interfacial adhesion with polymer matrices, these hemicelluloses and lignin, wax like impurities, amorphous content should be removed, and it was done by KMnO4 treatment. Structural properties and its modifications done by this treatment reveals that the experimental fibers can act as a good reinforcement material in composite manufacturing.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Surface morphology of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fiber under 100, 500, 1500 and 3000 magnification fields.

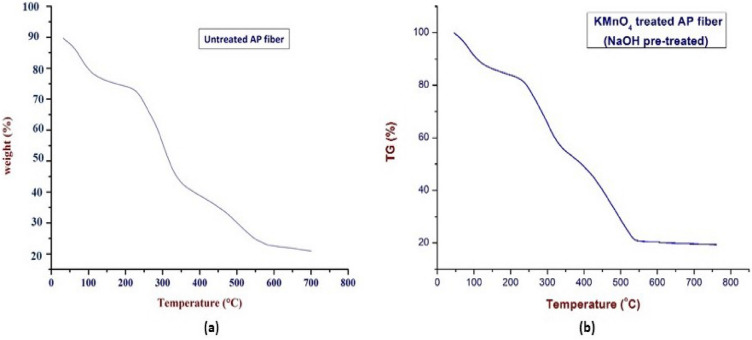

Thermo-gravimetric analysis

The weight loss of composites in relation to temperature increase was quantified using the thermo-gravimetric analysis. Greater thermal stability results from higher decomposition temperatures104. The TG and DTG curves of the KMnO4 treated APF sample was shown in Figs. 5 and 6. According to the graph, the degradation peaks are related to moisture evaporation, the breakdown of cellulose, lignin, wax, and other contaminants, as well as hemicellulose. At a temperature of about 40 °C to 120 °C, nearly 12% of weight loss has been occurred, which was mainly depending upon the moisture content in the untreated APF sample. Then the second major degradation occurs between 120 °C and 280 °C temperature range with the reduction of 18.5%. This weight loss has been observed due to the degradation of hemicellulose component. Within the temperature range between 280 °C and 400 °C, 25.46% of weight has been reduced. The destruction of the cellulose content's glycosidic linkages was the cause of the significant weight loss. Another drop was observed at the temperature within the range from 400 °C to 500 °C, nearly 20.93% of loss has occurred, which may be due to the degradation of lignin contents. Finally, degradation between 500 °C and 600 °C, due to the weight reduction of 9.5% due to the loss of wax like substances behind leaving the residue.

Figure 5.

TG curves of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fiber.

Figure 6.

DTG curves of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fibers.

In the DTG (Derivative thermo-gravimetric) curve, where the weight loss abruptly occurs at 90.7 °C with a weight loss of 0.283 mg/min, clearly shows the removal of moisture content within the fiber and the second and third degradation peaks were observed at the temperatures of 259.4 °C, 302.6 °C, 441.2 °C with the weight losses of 0.478 mg/min and 0.529 mg/min, 0.462 mg/min. Compared to hemicellulose and cellulose degradation, the thermal decomposition of lignin occurs over a wider temperature range, starts earlier, and goes up to higher temperatures 400 °C105. An abrupt drop in the DTG curve, which is related to the thermal breakdown of hemicelluloses and glycosidic linkages in cellulose, serves as an indicator of this106. Hemicellulose is a type of polysaccharide that is linked to cellulose and contains various sugar units. Compared to cellulose, it has a higher degree of chain branching but significantly lower levels of polymerization. Hemicellulose thermal degradation occurs before that of cellulose, although its impact is proportionally reduced by the amount of hemicellulose in the fiber107.

The next deterioration peak occurred at 603.9 °C with weight losses of 0.040 mg/min, which may have been caused by the breakdown of the fiber's lignin and wax components. Lignin is a complex hydrocarbon polymer that contains both aliphatic and aromatic components108. Compared to the thermal decomposition of hemicellulose and cellulose, the thermal decomposition of lignin occurs over a wider range, starts earlier, and goes to higher temperatures. The lesser amount of fiber present, however, also limits its impact107. When the temperature ranges from ambient temperature to more than 600 °C, the complex aromatic ring component of the lignin structure decomposes with a minimum weight loss rate9, 109. Tables 3 and 4 depicts the comparison between the thermal study (3) and Mass loss at Tmax (4) of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fibers.

Table 3.

Thermal study of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fibers.

| Type of fiber | Temperature during loss (°C) | Weight loss (%) | Thermal stability (°C) | Residual char at 750 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated AP fibers | 40–120 | 14.27 | 328.95 | 0.072 |

| 120–280 | 20.41 | |||

| 280–400 | 30.32 | |||

| 400–500 | 11.77 | |||

| 500–600 | 9.91 | |||

| KMnO4 treated AP fibers | 40–120 | 12 | 337.47 | 0.02 |

| 120–280 | 18.5 | |||

| 280–400 | 25.46 | |||

| 400–500 | 20.93 | |||

| 500–600 | 9.5 |

Table 4.

Mass loss at Tmax of untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fibres.

| Type of fiber | Total mass lost (%) | Tmax (°C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st stage | 2nd stage | 3rd stage | 4th stage | 5th stage | ||

| Untreated AP fibers | 14.27 | 34.68 | 65 | 76.77 | 86.88 | 226.3 |

| KMnO4 treated AP fibers | 12 | 30.5 | 55.96 | 76.89 | 86.39 | 223.5 |

Physical analysis

The density of the fiber treated with untreated and KMnO4 was estimated to be 1090 kg/m3 and 520 kg/m3 (Table 6). Cavities and holes were removed during alkalization110. So that, density of the optimally treated APF were slightly decreased. However, the density is slightly lower than that of the Acacia leucophloea 1385 kg/m3, coir fiber 1200 kg/m322. Due of the uneven profiles of bark fibers, diameter determination in the stem of AP fiber is rather difficult. The measured diameter of the ACF was 299.39 μm which was confirmed from SEM images. The Comparison of diameter and density values of untreated and KMnO4 treated APFs with other natural fibers are represented in Table 5.

Table 6.

Weight percentage of C, H, N, S in untreated and KMnO4 treated AP fiber.

| Fiber name | N% | C% | S% | H% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated AP fiber | 0.76 | 43.38 | 0.51 | 6.75 |

| KMnO4 treated AP fiber | 0.80 | 33.22 | ND | 4.61 |

ND not detected.

Table 5.

Comparison table for diameter and density values of raw and KMnO4 treated APFs with other natural fibers.

CHNS analysis

The Dumas's method58, which entails the total and rapid oxidation of the sample by "flash combustion," is the basis for the CHNS analyser, which is used to determine the percentages of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulphur in organic compounds. The Dumas method is a technique for calculating the quantity of chemical compounds (elements). This approach is most useful for figuring out how much C, H, N, and S are present in organic compounds, which typically ignite at 1800 °C. The weight percentage of each chemical in the KMnO4 treated sample is displayed in Table 6.

According to CHNS study, untreated AP fibres have a carbon content of 43.38%, however after being treated with permanganate, the carbon content decreases to 33.22%. One of the most vital aspects to alter the mechanical and tribological qualities of the final product is high carbon content in the natural fibers. Both samples can be employed as conductive fillers in dielectric loss materials because of the carbon content is above 30% in both. The average composition of carbon and hydrogen in chicken feather fibres are 47.4% and 7.2%116. It is found that the carbon content of coconut shell fibres and sugarcane bagasse fibres are 46.7% and 44.7%. These values are comparable to AP fibers.

Chemical analysis

Table 7 provides the comparison table of chemical composition of untreated, KMnO4 treated with different existing fibers. After pre-treatment, the cellulose content of the plant fibers generally increased. Due to the crystalline areas' altered lattice structures, the APF has a cellulose content of 55.4%117. These fibers have lower cellulose levels than Acacia Concinna fiber (59.43 wt%), Acacia leucophloea (68.09 wt% to 76.69 wt%), and Prosopis Juliflora fiber (61.65 wt% to 72.27 wt%)93 and larger than that of coir fiber (32–43%) and Ficus leaf fiber (38.1%)93, 118. Hemi-Cellulose of the APF was decreased (13.30%) in this treatment. This hemicellulose content was much larger than that of Acacia concinna fiber (12.78%) and Acacia planifrons (9.41%) etc. The diffusion of lignin in KMnO4 solution was blamed for the significant change in the lignin concentration (17.75%). However, it is soluble in hot alkali, rapidly oxidised, and condensable with phenol. Lignin is not hydrolyzed by acids119. After this treatment, pectin levels similarly dropped (1.9%). Wax content (0.79%) of the KMnO4-treated APF dropped as well, which is a favourable change. As opposed to plant fiber with higher wax content, fiber from plants with reduced wax content can produce excellent interfacial bonds with polymers120. The amount of moisture (13.4%) in the KMnO4-treated APF decreased as well. The ash content of the APF, on the other hand, was subtly increased from 10%, which supported the growth of the crystalline component in the fiber110.

Table 7.

Comparison table of chemical compositions of APFs with other existing fibers.

| Fiber name | Cellulose (%) | Hemi-cellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Pectin (%) | Wax (%) | Moisture (%) | Ash (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated APF | 45.68 | 41.13 | 24.49 | 12.19 | 13.91 | 0.36 | 3.13 | Present work |

| KMnO4 treated APF | 55.4 | 13.3 | 17.75 | 1.9 | 13.4 | 0.79 | 10 | Present work |

| Kenaf fiber | 45–57 | 8–13 | 21.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 6.2–12 | 2–5 | 121, 122 |

| Wheat husk | 36 | 18 | 16 | – | 123 | |||

| Sisal fiber | 78 | 10 | 8 | – | 2 | 11 | 1 | 124 |

| Agave fiber | 68.42 | 4.85 | 4.85 | – | 0.26 | 7.69 | – | 125 |

| Corn straw fiber | 44.5 | 19.7 | 25.5 | 1.4 | – | – | – | 121 |

Tensile strength

One of the most often investigated features of natural fiber reinforced composites is tensile strength. When choosing a particular natural fiber for a given application, the fiber strength can be a crucial consideration126. Tensile testing of individual technical fibers is a standard method for determining the tensile characteristics of natural fibers127. The test was conducted at an ambient temperature of 21 °C, a relative humidity of approximately 65%, and a specimen gauge length of 50 mm100. The comparison of tensile strength, young's modulus, micro-fibrillar angle, and breaking elongation of the untreated and KMnO4-treated APFs with other natural fibers are shown in Table 8. According to the computed data, the tensile strength of the untreated and KMnO4 treated APFs were found to 181.69 MPa and 685 MPa with 6.2%, 4.1% elongation and young's modulus 29.3GPa, 16.707 GPa respectively. The tensile strength of the jute fiber is (400–800 MPa) and its young’s modulus is (10–30 GPa)128. As a result, the AP fiber's tensile strength and young's modulus were almost on par with those of jute fiber. The cell walls structure and chemical makeup of bark fibers, particularly the amount of cellulose, have a significant impact on their mechanical properties129.

Table 8.

Comparison table for Tensile strength of untreated and KMnO4 treated APFs with other natural fibers.

| Fiber name | Tensile strength (MPa) | Young’s modulus (GPa) | Micro-fibrillar angle (°) | Elongation at break (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated APF | 181.69 ± 40 | 29.30 ± 3 | 19.67 ± 3 | 6.2 | Present study |

| KMnO4 treated APF | 685 ± 60 | 16.707 ± 7 | 16.134 ± 5 | 4.1 | Present study |

| Zea mays | 13.243 | 0.529 | 12.68 | 2.5 | 59 |

| Ficus racemosa | 270 | 67.45 | – | 2.57 | 130 |

| Hemp | 690 | 70 | 6.2 | 1.6 | 131 |

| Butea parviflora | 198.12 | 4.4 | 16.88 ± 9.87 | 4.5 | 132 |

| Heteropogon contortus | 476 ± 11.6 | 48 ± 2.8 | 14.53 ± 0.53 | – | 133 |

| Cissus quadrangularis | 200.39 | 4.89 | – | 3.57–8.37 | 51 |

| Banana | 700–800 | 27–32 | – | – | 133 |

Conclusion

The paper discusses the outcomes of analyses performed on the KMnO4-treated AP fiber using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA), and mechanical (tensile strength) analysis.

The mechanical analysis of AP fiber makes it a dependable and long-lasting material for building composite fiber materials and fiber reinforced concrete for use in construction. Due to the orientation of the fibers, AP fibers have superior mechanical properties (such strength and young's modulus), which improves their capacity to handle loads and stress.

The KMnO4-treated AP fiber's X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns revealed a semi-crystalline structure, with a crystallinity index of 51.63%. These findings imply that the KMnO4 treatment was successful in eliminating impurities and raising the AP fiber's crystallinity index. The crystallite size of the KMnO4-treated AP fiber was 1.05 nm. Overall, the results of this study provide valuable information on the effects of KMnO4 treatment on the structure, stability and mechanical analysis of AP fiber.

FTIR spectral analysis revealed the existence of lignin, saline content, and components of cellulose and hemicellulose. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that the KMnO4-treated AP fiber's surface was rough and disordered, with amorphous content and impurities clearly apparent. Chemical analysis outcomes showed that APF has the higher cellulose (55.4%) and lesser hemicellulose (13.3%) content.

The degradation of moisture, cellulose, lignin, wax, and other impurities, as well as hemicellulose, corresponded to the peaks in the thermo-gravimetric study. This thermo-gravimetric analysis showed that the KMnO4 treated AP fiber has a higher thermal stability (337.47 °C), with higher decomposition temperatures (223.5 °C), making it a potential candidate for use in composite materials.

This fiber's overall structure and stability have improved as a result of the KMnO4 treatment. Therefore, with further purification, AP fibre has the potential to be used as a reinforcement material in the creation of composites. All the above findings and lower density (520 kg/m3) of the APF would make them suitable for lightweight composite materials.

The experiments conducted on KMnO4 treated Acacia pennata fibers show remarkable mechanical properties, such as tensile strength of 685 MPa and a Young's modulus of 16.707 GPa. The high tensile strength of Acacia pennata fibers has a possibility of utilizing as particle replacement of cementitious material in the construction as well as interior structural components. In the current practices many natural fibers are utilized in the construction sector. Furthermore, these composites have high potential to be applied in the sandwish structure due to its light weight with higher flexural properties. The fibers microfibrillar angle of 16.134º and break elongation of 4.1% further support their suitability for these applications. However, it is crucial to evaluate these results against industry standards to fully assess the potential of the Acacia pennata fibers applications. Further research should be conducted to examine their feasibility and performance against existing materials in the construction and composite industries.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully appreciate the support given by K.R.Jaya Sheeba (Reg No: 19233042132010), Research scholar, PG & Research Department of Physics, Holy Cross College (Autonomous), Nagercoil – 629004, Affiliated to Manonmanium Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, India. The author thanks Vicerrectoria de Investigacion y Desarrollo (VRID) y Direccion de Investigacion y Creacion Artistica DICA, Proyecto presentado al Concurso VRID-Iniciación 2022, VRID N°2022000449-INI, Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile. Centro Nacional de Excelencia para la Industria de la Madera (ANID BASAL FB210015 CENAMAD), Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Vicuña Mackenna 7860, Santiago, Chile.

Author contributions

K.R.J.S.—Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Writing—original draft. R.K.P.—Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. K.P.A.—Conceptualization, Formal analysis; Validation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. S.S.—Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. S.A.—Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. E.S.F.—Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The financial support from Universidad de Santiago de Chile, Usach, through project N°092218SF_POSTDOC, Dirección de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, Dicyt. E.I.S.F. acknowledges funding coming from the Chilean National Research and Development Agency, ANID, research project Fondecyt Regular 1211767.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the author and corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Retnam Krishna Priya, Email: krishnapriya@holycrossngl.edu.in.

Siva Avudaiappan, Email: savudaiappan@udec.cl.

References

- 1.Mwaikambo LY, Ansell MP. Chemical modification of hemp, sisal, jute, and kapok fibers by alkalization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002;84:2222–2234. doi: 10.1002/app.10460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard M, et al. The effect of processing parameters on the mechanical properties of kenaf fibre plastic composite. Mater. Des. 2011;32:1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2010.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Célino A, Gonçalves O, Jacquemin F, Fréour S. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of water sorption in natural fibres using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014;101:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pal DB, et al. Enhanced biogas production potential analysis of rice straw: Biomass characterization, kinetics and anaerobic co-digestion investigations. Bioresour. Technol. 2022;358:127391. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiwari YM, Sarangi SK. Comprehensive characterization of new natural fiber extracted from the stem of Grewia flavescens plant. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:14579–14591. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2022.2068107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopinath R, Billigraham P, Sathishkumar TP, Rajasekar R. Physicochemical, thermal and mechanical properties of novel cellulosic fiber extracted from Ficus retusa. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:14706–14724. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2022.2068727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machaka M, Abou Chakra H, Elkordi A. Alkali treatment of fan palm natural fibers for use in fiber reinforced concrete. Eur. Sci. J. 2014;10:186–195. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gopinath R, Billigraham P, Sathishkumar TP. Characterization studies on novel cellulosic fiber obtained from the bark of Madhuca longifolia tree. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:14880–14897. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2022.2069192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derosa M, Monreal C, Schnitzer M, Walsh R, Sultan Y. Nanotechnology in fertilizers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:91. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramesh M, et al. Influence of Haritaki (Terminalia chebula) nano-powder on thermo-mechanical, water absorption and morphological properties of Tindora (Coccinia grandis) tendrils fiber reinforced epoxy composites. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:6452–6468. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2021.1921660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramesh M, et al. Impact of silane treatment on characterization of Ipomoea staphylina plant fiber reinforced epoxy composites. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:5888–5899. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2021.1902896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivasubramanian P, et al. Effect of alkali treatment on the properties of Acacia caesia bark fibres. Fibers. 2021;9:49. doi: 10.3390/fib9080049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HS, Park YH, Kim S, Choi Y-E. Application of a polyethylenimine-modified polyacrylonitrile-biomass waste composite fiber sorbent for the removal of a harmful cyanobacterial species from an aqueous solution. Environ. Res. 2020;190:109997. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagappan S, Subramani SP, Palaniappan SK, Mylsamy B. Impact of alkali treatment and fiber length on mechanical properties of new agro waste Lagenaria Siceraria fiber reinforced epoxy composites. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:6853–6864. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2021.1932681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaker K, et al. Cellulosic fillers extracted from Argyreia speciose waste: A potential reinforcement for composites to enhance properties. J. Nat. Fibers. 2020 doi: 10.1080/15440478.2020.1856271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaker K, et al. Extraction and characterization of novel fibers from Vernonia elaeagnifolia as a potential textile fiber. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020;152:112518. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mylsamy B, Chinnasamy V, Palaniappan SK, Subramani SP, Gopalsamy C. Effect of surface treatment on the tribological properties of Coccinia Indica cellulosic fiber reinforced polymer composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020;9:16423–16434. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.11.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aruchamy K, et al. Effect of blend ratio on the thermal comfort characteristics of cotton/bamboo blended fabrics. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:105–114. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2020.1731903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhuvaneshwaran M, Sampath PS, Sagadevan S. Influence of fiber length, fiber content and alkali treatment on mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced epoxy composites. Polimery/Polymers. 2019;64:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhuvaneshwaran M, Subramani SP, Palaniappan SK, Pal SK, Balu S. Natural cellulosic fiber from Coccinia indica stem for polymer composites: Extraction and characterization. J. Nat. Fibers. 2021;18:644–652. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2019.1642826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaker, K., Nawab, Y. & Jabbar, M. Bio-composites: Eco-friendly substitute of glass fiber composites. Handb. Nanomater. Nanocomposites Energy Environ. Appl. (2021).

- 22.Nurwidayati R, Azima NN. Utilization of coconut shell ash as a substitute material in paving block manufacturing. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022;999:012009. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/999/1/012009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holbery J, Houston D. Natural-fiber-reinforced polymer composites in automotive applications. JOM. 2006;58:80–86. doi: 10.1007/s11837-006-0234-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bledzki AK, Faruk O, Sperber VE. Cars from bio-fibres. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2006;291:449–457. doi: 10.1002/mame.200600113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Awoyera PO, et al. Experimental findings and validation on torsional behaviour of fibre-reinforced concrete beams: A review. Polymers. 2022;14:1171. doi: 10.3390/polym14061171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avudaiappan S, et al. Innovative use of single-use face mask fibers for the production of a sustainable cement mortar. J. Compos. Sci. 2023;7:214. doi: 10.3390/jcs7060214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Célino A, Fréour S, Jacquemin F, Casari P. The hygroscopic behavior of plant fibers: A review. Front. Chem. 2014;1:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2013.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonawane GH, Patil SP, Sonawane SH. Nanocomposites and its applications. In: Mohan Bhagyaraj S, Oluwafemi OS, Kalarikkal N, Thomas SB, editors. Micro and Nano Technologies. Woodhead Publishing; 2018. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meneghetti P, Qutubuddin S. Synthesis, thermal properties and applications of polymer-clay nanocomposites. Thermochim. Acta. 2006;442:74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tca.2006.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheeba KRJ, et al. Characterisation of sodium acetate treatment on Acacia pennata natural fibres. Polymers. 2023;15:1996. doi: 10.3390/polym15091996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul OA, et al. Structural retrofitting of corroded reinforced concrete beams using bamboo fiber laminate. Materials. 2021;14:6711. doi: 10.3390/ma14216711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arunachalam KP, Avudaiappan S, Flores EIS, Parra PF. Experimental study on the mechanical properties and microstructures of cenosphere concrete. Materials. 2023;16:3518. doi: 10.3390/ma16093518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Komuraiah A, Kumar NS, Prasad BD. Chemical composition of natural fibers and its influence on their mechanical properties. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2014;50:359–376. doi: 10.1007/s11029-014-9422-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad R, Hamid R, Osman SA. Physical and chemical modifications of plant fibres for reinforcement in cementitious composites. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019;2019:5185806. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peças P, Carvalho H, Salman H, Leite M. Natural fibre composites and their applications: A review. J. Compos. Sci. 2018;2:1–20. doi: 10.3390/jcs2040066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaushik V, Kumar A, Kalia S. Effect of mercerization and benzoyl peroxide treatment on morphology, thermal stability and crystallinity of sisal fibers. Int. J. Text. Sci. 2013;1:101–105. doi: 10.5923/j.textile.20120106.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abisha M, et al. Biodegradable green composites: Effects of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) treatment on thermal, mechanical, and morphological behavior of Butea parviflora (BP) fibers. Polymers. 2023;15:2197. doi: 10.3390/polym15092197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liew, M. S., Nguyen-Tri, P., Nguyen, T. A. & Kakooei, S. Smart Nanoconcretes and Cement-Based Materials (2020).

- 39.Segal L, Creely JJ, Martin AE, Conrad CM. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-ray diffractometer. Text. Res. J. 1959;29:786–794. doi: 10.1177/004051755902901003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gurukarthik Babu B, Prince Winston D, SenthamaraiKannan P, Saravanakumar SS, Sanjay MR. Study on characterization and physicochemical properties of new natural fiber from Phaseolus vulgaris. J. Nat. Fibers. 2019;16:1035–1042. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2018.1448318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amutha V, Kumar S. Physical, chemical, thermal, and surface morphological properties of the bark fiber extracted from Acacia concinna plant. J. Nat. Fibers. 2019;18:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdul Samad Khan, A. A. C. Handbook of Ionic Substituted Hydroxyapatites (2020).

- 43.Rivera-Gómez C, Galán-Marín C, Bradley F. Analysis of the influence of the fiber type in polymer matrix/fiber bond using natural organic polymer stabilizer. Polymers. 2014;6:977–994. doi: 10.3390/polym6040977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arunachalam KP, et al. Innovative use of copper mine tailing as an additive in cement mortar. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.06.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arunachalam KP, Henderson JH. Experimental study on mechanical strength of vibro-compacted interlocking concrete blocks using image processing and microstructural analysis. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s40996-023-01194-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.RajeshKumar K, et al. Structural performance of biaxial geogrid reinforced concrete slab. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2022;20:349–359. doi: 10.1007/s40999-021-00668-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abraham J, Mohammed AP, Ajith Kumar MP, George SC, Thomas S. Thermoanalytical techniques of nanomaterials. In: Mohan Bhagyaraj S, Oluwafemi OS, Kalarikkal N, Thomas SB, editors. Micro and Nano Technologies. Woodhead Publishing; 2018. pp. 213–236. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moshi AAM, et al. Characterization of a new cellulosic natural fiber extracted from the root of Ficus religiosa tree. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;142:212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravindran D, et al. Characterization of natural cellulosic fiber extracted from Grewia damine flowering plant’s stem. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;164:1246–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senthamaraikannan P, Kathiresan M. Characterization of raw and alkali treated new natural cellulosic fiber from Coccinia grandis L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;186:332–343. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siva R, et al. Characterization of mechanical, chemical properties and microstructure of untreated and treated Cissus quadrangularis fiber. Mater. Today Proc. 2021;47:4479–4483. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.05.320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subramanian SG, Rajkumar R, Ramkumar T. Characterization of natural cellulosic fiber from Cereus hildmannianus. J. Nat. Fibers. 2021;18:343–354. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2019.1623744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Indran S, Raj RE. Characterization of new natural cellulosic fiber from Cissus quadrangularis stem. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;117:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siva R, Valarmathi TN, Palanikumar K, Samrot AV. Study on a Novel natural cellulosic fiber from Kigelia africana fruit: Characterization and analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;244:116494. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herlina Sari N, Wardana ING, Irawan YS, Siswanto E. Characterization of the chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of NaOH-treated natural cellulosic fibers from corn husks. J. Nat. Fibers. 2018;15:545–558. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2017.1349707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manimaran P, Pillai GP, Vignesh V, Prithiviraj M. Characterization of natural cellulosic fibers from Nendran Banana Peduncle plants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;162:1807–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao KMM, Rao KM. Extraction and tensile properties of natural fibers: Vakka, date and bamboo. Compos. Struct. 2007;77:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheeba KRJ, et al. Physico-chemical and extraction properties on alkali-treated Acacia pennata fiber. Environ. Res. 2023;233:116415. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kavitha SA, et al. Investigation on properties of raw and alkali treated novel cellulosic root fibres of Zea mays for polymeric composites. Polymers. 2023;15:1802. doi: 10.3390/polym15071802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Velmurugan G, Vadivel D, Arravind R, Mathiazhagan A, Vengatesan SP. Tensile test analysis of natural fiber reinforced composite. Int. J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 2014;3:148–152. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horst C, et al. Springer handbook of materials measurement methods. Mater. Today. 2006;9:52. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(06)71582-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moigne N, Otazaghine B, Corn S, Angellier-Coussy H, Bergeret A. Characterization of the Fibre Modifications and Localization of the Functionalization Molecules. Springer; 2018. pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ganapathy T, Sathiskumar R, Senthamaraikannan P, Saravanakumar SS, Khan A. Characterization of raw and alkali treated new natural cellulosic fibres extracted from the aerial roots of banyan tree. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;138:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oladele IO, Michael OS, Adediran AA, Balogun OP, Ajagbe FO. Acetylation treatment for the batch processing of natural fibers: Effects on constituents, tensile properties and surface morphology of selected plant stem fibers. Fibers. 2020;8:73. doi: 10.3390/fib8120073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mishra S, Prabhakar B, Kharkar PS, Pethe AM. Banana peel waste: An emerging cellulosic material to extract nanocrystalline cellulose. ACS Omega. 2023;8:1140–1145. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c06571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mendes CA, Adnet F, Leite MCAM, Furtado C, Maria F. Chemical, physical, mechanical, thermal and morphological characterization of corn husk residue. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2015;49:727–735. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baskaran PG, Kathiresan M, Senthamaraikannan P, Saravanakumar SS. Characterization of new natural cellulosic fiber from the bark of Dichrostachys cinerea. J. Nat. Fibers. 2018;15:62–68. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2017.1304314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Babu BG, et al. Investigation on the physicochemical and mechanical properties of novel alkali-treated Phaseolus vulgaris fibers. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:770–781. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2020.1761930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saravanakumar SS, Kumaravel A, Nagarajan T, Sudhakar P, Baskaran R. Characterization of a novel natural cellulosic fiber from Prosopis juliflora bark. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;92:1928–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kathirselvam M, Kumaravel A, Arthanarieswaran VP, Saravanakumar SS. Characterization of cellulose fibers in Thespesia populnea barks: Influence of alkali treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;217:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Balaji AN, Nagarajan KJ. Characterization of alkali treated and untreated new cellulosic fiber from Saharan aloe vera cactus leaves. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;174:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mohd Roslim MH, Sapuan S, Leman Z, Ishak M. Comparative study on chemical composition, physical, tensile, and thermal properties of sugar palm fiber (Arenga pinnata) obtained from different geographical locations. BioResources. 2017;12:9366–9382. doi: 10.15376/biores.12.4.9366-9382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tamanna TA, Belal SA, Shibly MAH, Khan AN. Characterization of a new natural fiber extracted from Corypha taliera fruit. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:7622. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87128-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nayak S, Mohanty J. Influence of chemical treatment on tensile strength, water absorption, surface morphology, and thermal analysis of areca sheath fibers. J. Nat. Fibers. 2019;16:589–599. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2018.1430650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yusriah L, Sapuan SM, Zainudin ES, Mariatti M. Characterization of physical, mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of agro-waste betel nut (Areca catechu) husk fibre. J. Clean. Prod. 2014;72:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Keskin OY, Dalmis R, Balci Kilic G, Seki Y, Koktas S. Extraction and characterization of cellulosic fiber from Centaurea solstitialis for composites. Cellulose. 2020;27:9963–9974. doi: 10.1007/s10570-020-03498-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Belouadah Z, Ati A, Rokbi M. Characterization of new natural cellulosic fiber from Lygeum spartum L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;134:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sarala R. Characterization of a new natural cellulosic fiber extracted from Derris scandens stem. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;165:2303–2313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Binoj JS, Raj RE, Sreenivasan VS, Thusnavis GR. Morphological, physical, mechanical, chemical and thermal characterization of sustainable Indian Areca fruit husk fibers (Areca catechu L.) as potential alternate for hazardous synthetic fibers. J. Bionic Eng. 2016;13:156–165. doi: 10.1016/S1672-6529(14)60170-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DjafariPetroudy SR. Physical and mechanical properties of natural fibers. In: Fan M, Fu F, editors. Advanced High Strength Natural Fibre Composites in Construction. Woodhead Publishing; 2017. pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Awoyera PO, Olalusi OB, Ibia S, Prakash A, K. Water absorption, strength and microscale properties of interlocking concrete blocks made with plastic fibre and ceramic aggregates. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021;15:e00677. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sheeba KRJ, et al. Case studies in construction materials enhancing structural, thermal, and mechanical properties of Acacia pennata natural fibers through benzoyl chloride treatment for construction applications. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023;19:e02443. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arthanarieswaran VP, Kumaravel A, Saravanakumar SS. Physico-chemical properties of alkali-treated acacia leucophloea fibers. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2015;20:704–713. doi: 10.1080/1023666X.2015.1081133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sanchez-Echeverri LA, Medina-Perilla JA, Ganjian E. Nonconventional Ca(OH)2 treatment of bamboo for the reinforcement of cement composites. Materials. 2020;13:1892. doi: 10.3390/ma13081892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Elenga RG, Dirras GF, Goma Maniongui J, Djemia P, Biget MP. On the microstructure and physical properties of untreated raffia textilis fiber. Composites Part A. 2009;40:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Binoj JS, Raj RE, Indran S. Characterization of industrial discarded fruit wastes (Tamarindus indica L.) as potential alternate for man-made vitreous fiber in polymer composites. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018;116:527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2018.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kumar R, Hynes NRJ, Senthamaraikannan P, Saravanakumar S, Sanjay MR. Physicochemical and thermal properties of Ceiba pentandra bark fiber. J. Nat. Fibers. 2018;15:822–829. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2017.1369208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Manimaran P, et al. Physico-chemical properties of fiber extracted from the flower of celosia argentea plant. J. Nat. Fibers. 2021;18:464–473. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2019.1629149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gopinath R, Billigraham P, Sathishkumar TP. Investigation of physico-chemical, mechanical, and thermal properties of new cellulosic bast fiber extracted from the bark of Bauhinia purpurea. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:9624–9641. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2021.1990180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kumar R, et al. Characterization of new cellulosic fiber from the bark of Acacia nilotica L. Plant. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:199–208. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2020.1738305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Manimaran P, Prithiviraj M, Saravanakumar SS, Arthanarieswaran VP, Senthamaraikannan P. Physicochemical, tensile, and thermal characterization of new natural cellulosic fibers from the stems of Sida cordifolia. J. Nat. Fibers. 2018;15:860–869. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2017.1376301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gopinath R, Billigraham P, Sathishkumar TP. Characterization studies on new cellulosic fiber extracted from leucaena leucocephala tree. J. Nat. Fibers. 2023;20:57922. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2022.2157922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Khuntia T, Biswas S. Characterization of a novel natural filler from Sirisha Bark. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:3083–3092. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2020.1838997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fan M, Dai D, Huang B. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for natural fibres. Fourier Transform Mater. Anal. 2012 doi: 10.5772/35482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Glória GO, de Moraes YM, Margem FM, Vieira CMF, Monteiro SN. Evaluation of giant bamboo fibers components by infrared spectroscopy. Cong Annu. ABM. 2017 doi: 10.5151/1516-392x-26322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Comnea-Stancu IR, Wieland K, Ramer G, Schwaighofer A, Lendl B. On the identification of rayon/viscose as a major fraction of microplastics in the marine environment: Discrimination between natural and manmade cellulosic fibers using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017;71:939–950. doi: 10.1177/0003702816660725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi Z, Zhu G, Xu H, Chen Y. Preparation and characterization of AC/PEDOT composites. Gongneng Cailiao/J. Funct. Mater. 2018;49:06201–06205. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sosiati H, Harsojo H. Effect of combined treatment methods on the crystallinity and surface morphology of kenaf bast fibers. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2014;48:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adeniyi AG, Onifade DV, Ighalo JO, Abdulkareem SA, Amosa MK. Extraction and characterization of natural fibres from plantain (Musa paradisiaca) stalk wastes. Iran. J. Energy Environ. 2020;11:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jebadurai SG, Raj RE, Sreenivasan VS, Binoj JS. Comprehensive characterization of natural cellulosic fiber from Coccinia grandis stem. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;207:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vârban R, Crișan I, Vârban D, Ona A, Olar L, Stoie A, Ștefan R. Comparative FT-IR prospecting for cellulose in stems of some fiber plants: Flax, velvet leaf, hemp and jute. Appl. Sci. 2021;11(18):8570. doi: 10.3390/app11188570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reddy KO, et al. Extraction and characterization of novel lignocellulosic fibers from Thespesia lampas plant. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2014;19:48–61. doi: 10.1080/1023666X.2014.854520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moosavinejad SM, Madhoushi M, Vakili M, Rasouli D. Evaluation of degradation in chemical compounds of wood in historical buildings using Ft-Ir And Ft-Raman vibrational spectroscopy. Maderas Cienc. Tecnol. 2019;21:381–392. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Neto JSS, et al. Effect of chemical treatment on the thermal properties of hybrid natural fiber-reinforced composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019;136:1–13. doi: 10.1002/app.47154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Correa SM, Arbilla G, Marques MRC, Oliveira KMPG. The impact of BTEX emissions from gas stations into the atmosphere. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2012;3:163–169. doi: 10.5094/APR.2012.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liu W, Mohanty AK, Drzal LT, Askel P, Misra M. Effects of alkali treatment on the structure, morphology and thermal properties of native grass fibers as reinforcements for polymer matrix composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2004;39:1051–1054. doi: 10.1023/B:JMSC.0000012942.83614.75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Monteiro S, Calado V. Thermogravimetric behavior of natural fibers reinforced polymer composites: An overview. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2012;557:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.msea.2012.05.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bledzki AK, Gassan J. Composites reinforced with cellulose based fibres. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1999;24:221–274. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6700(98)00018-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Selvaraj M, et al. Extraction and characterization of a new natural cellulosic fiber from bark of Ficus carica plant as potential reinforcement for polymer composites. J. Nat. Fibers. 2023;20:2194699. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2023.2194699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Devaki E, Boominathan S. Physical, thermal and tensile analysis of sansiveria roxburghiana leaf fiber. J. Nat. Fibers. 2022;19:7797–7805. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2021.1958413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.John M, Anandjiwala R. Recent developments in chemical modification and characterization of natural fiber-reinforced composites. Polym. Compos. 2008;29:187–207. doi: 10.1002/pc.20461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Thamae T, Baillie C. Influence of fibre extraction method, alkali and silane treatment on the interface of Agave americana waste HDPE composites as possible roof ceilings in Lesotho. Compos. Interfaces. 2007;14:821–836. doi: 10.1163/156855407782106483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Davies P, Morvan C, Sire O, Baley C. Structure and properties of fibres from sea-grass (Zostera marina) J. Mater. Sci. 2007;42:4850–4857. doi: 10.1007/s10853-006-0546-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sathishkumar TP, Navaneethakrishnan P, Shankar S, Rajasekar R. Characterization of new cellulose sansevieria ehrenbergii fibers for polymer composites. Compos. Interfaces. 2013;20:575–593. doi: 10.1080/15685543.2013.816652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Monteiro S, Aquino R, Perissé Duarte Lopes F. Performance of curaua fibers in pullout tests. J. Mater. Sci. 2008;43:489–493. doi: 10.1007/s10853-007-1874-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Seok H-Y, et al. AtC3H17, a non-tandem CCCH zinc finger protein, functions as a nuclear transcriptional activator and has pleiotropic effects on vegetative development, flowering and seed development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:603–615. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcw013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rajkumar R, Manikandan A, Saravanakumar SS. Physicochemical properties of alkali-treated new cellulosic fiber from cotton shell. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2016;21:359–364. doi: 10.1080/1023666X.2016.1160509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Amutha V, Senthilkumar B. Physical, chemical, thermal, and surface morphological properties of the bark fiber extracted from Acacia concinna plant. J. Nat. Fibers. 2021;18:1661–1674. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2019.1697986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Westman, M. P., Fifield, L. S., Simmons, K. L., Laddha, S. & Kafentzis, T. A. Natural Fiber Composites: A Review (2010).

- 120.Reddy KO, Maheswari CU, Reddy DJP, Rajulu AV. Thermal properties of Napier grass fibers. Mater. Lett. 2009;63:2390–2392. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2009.08.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jones D, Ormondroyd GO, Curling SF, Centre B, Kingdom U. Chemical Compositions of Natural Fibres. Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yussuf A, Massoumi I, Hassan A. Comparison of polylactic acid/kenaf and polylactic acid/rise husk composites: The influence of the natural fibers on the mechanical, thermal and biodegradability properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2010;18:422–429. doi: 10.1007/s10924-010-0185-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bledzki AK, Mamun AA, Volk J. Physical, chemical and surface properties of wheat husk, rye husk and soft wood and their polypropylene composites. Composites Part A. 2010;41:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2009.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sreekumar PA, et al. Transport properties of polyester composite reinforced with treated sisal fibers. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2012;31:117–127. doi: 10.1177/0731684411431971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Milanese AC, Cioffi MOH, Voorwald HJC. Thermal and mechanical behaviour of sisal/phenolic composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012;43:2843–2850. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.04.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Faruk O, Bledzki AK, Fink HP, Sain M. Biocomposites reinforced with natural fibers: 2000–2010. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012;37:1552–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Soatthiyanon N, Crosky A, Heitzmann MT. Comparison of experimental and calculated tensile properties of flax fibres. J. Compos. Sci. 2022;6:100. doi: 10.3390/jcs6040100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mohajerani A, et al. Amazing types, properties, and applications of fibres in construction materials. Materials. 2019;12:2513. doi: 10.3390/ma12162513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Arthanarieswaran VP, Kumaravel A, Saravanakumar SS. Characterization of new natural cellulosic fiber from Acacia leucophloea bark. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2015;20:367–376. doi: 10.1080/1023666X.2015.1018737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Manimaran P, Saravanan SP, Prithiviraj M. Investigation of physico chemical properties and characterization of new natural cellulosic fibers from the bark of Ficus racemosa. J. Nat. Fibers. 2021;18:274–284. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2019.1621233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Sanjay MR, Arpitha GR, Yogesha B. Study on mechanical properties of natural—glass fibre reinforced polymer hybrid composites: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2015;2:2959–2967. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2015.07.264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Mohan A, et al. Investigating the mechanical, thermal, and crystalline properties of raw and potassium hydroxide treated butea parviflora fibers for green polymer composites. Polymers. 2023;15:3522. doi: 10.3390/polym15173522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hyness NRJ, Vignesh NJ, Senthamaraikannan P, Saravanakumar SS, Sanjay MR. Characterization of new natural cellulosic fiber from heteropogon contortus plant. J. Nat. Fibers. 2018;15:146–153. doi: 10.1080/15440478.2017.1321516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the author and corresponding author on reasonable request.