Over 78,000 new CNS tumors are diagnosed each year in the United States, nearly one-third of which are primary malignant brain tumors,1 and the US prevalence of primary brain tumors is approximately 688,000.2 While primary CNS neoplasms represent only 1.4% of new cancer diagnoses, approximately 2.7% of cancer deaths are related to CNS neoplasms,3 and it is estimated that 16,947 deaths will result from primary CNS tumors in 2017.1 Population-based studies have shown that socioeconomic disparities are present within the neuro-oncology community,4–7 highlighting the need for a unified system of quality metrics in this growing field. Toward this end, several authors have published work on quality-based practice and on the inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in brain tumor care.8–12

During the launch of American Academy of Neurology (AAN)'s Axon Registry®, the AAN requested that subspecialty societies identify gaps in subspecialty care amenable to clinical quality measure development, and work to identify ways the AAN could help meet those needs. Thereafter, the AAN and the Society for Neuro-oncology (SNO) identified a small work group to determine neuro-oncologic gaps in care, to evaluate supporting evidence for clinical practice standards, and to develop feasible clinical quality measures to address these areas. The hope is that these measures will help drive clinical practice improvement and better patient outcomes.

Opportunities for improvement

Following a thorough literature search, the work group identified 5 areas in need of quality improvement. The specific topics and rationale for each are described below.

Multidisciplinary care plan development

Multidisciplinary tumor board discussions for care plan determination have been associated with improved quality and coordination of care in various cancers, and are a well-established quality indicator in oncology care, both domestically and internationally.8,13–15 Indeed, establishment of a regularly meeting tumor board with input from neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, radiation oncology, neuroradiology, and neuropathology has been cited as a necessary component for establishing a brain tumor center.16 One study of brain tumor board discussions revealed that 91% of 1,516 clinical recommendations were implemented, and that nearly half of those were recommendations for conservative management, demonstrating the utility of multidisciplinary input in neuro-oncology cases and in optimizing patient-centered outcomes.15 Another study showed that patients treated by physicians who attend weekly tumor boards are significantly more likely to be enrolled in clinical trials for various cancers, and patient survival is better when physicians attend a specialized tumor board as compared to a general oncology tumor board.17 Thus, a treatment gap does exist.

Molecular brain tumor testing

Recent advances in molecular characterization of brain tumors have improved the understanding of disease pathophysiology and prognosis, and have provided new therapeutic opportunities. For the first time, the 2016 WHO Classification of Tumors of the CNS includes molecular measures in addition to histology, identifying integrated diagnoses as the new standard for maximal diagnostic specificity.18 Among the molecular testing recommended for gliomas, isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation analysis and 1p/19q codeletion reporting are required for integrated diagnoses. It is hoped that the use of integrated diagnoses will facilitate further progress in research and therapeutic efficacy for brain tumor patients. The work group believes a treatment gap exists as providers and hospitals work to implement the most recent WHO guidelines.

Chemotherapy education and informed consent

American Society of Clinical Oncology and Oncology Nursing Society guidelines indicate that all patients who are prescribed chemotherapy should be provided education in advance of prescription.19 The most frequently used chemotherapies in neuro-oncology are oral, including temozolomide, lomustine, and procarbazine, and errors in the home administration of oral chemotherapy are associated with a high likelihood of harm.20 Education of patients and caregivers to reduce the risk of error is vital, as well as to empower them to speak up if an error occurs.20 Further, a patient's (or proxy's) consent to treatment after receiving adequate education is an important part of delivering quality cancer care, and is not only ethical but may mitigate legal risk in some cases.21 Written documentation of consent is stressed among oncology quality best practices,21 which may be either in the form of documentation by the clinician or a document signed by the patient or proxy. A review of practice-level systems indicated opportunities for quality improvement efforts for the safe management of chemotherapy, defining the treatment gap targeted here.22

Perioperative MRI

For high-grade gliomas, extent of resection is strongly correlated with overall survival.23,24 Furthermore, many clinical trials include measures of residual disease as a criterion for inclusion. Postoperative imaging is a requisite for radiation oncologists to design safe and effective treatment plans, and finally, radiographic monitoring of therapeutic efficacy is contingent upon a baseline (postoperative, pretherapy) MRI scan. Given vascular and inflammatory changes that occur after brain tumor resection, which can reduce imaging specificity, guidelines exist to perform a postoperative MRI scan with and without contrast within 24–72 hours after resection.25,26 In fact, findings from early postoperative MRI itself have been directly shown to correlate with survival.27 Intraoperative MRI may also be used during tumor resection, though gadolinium is often not given intraoperatively and this lack of contrast material may reduce the utility of the imaging for the above referenced items. A retrospective study of a single neurosurgeon shows that intraoperative MRI-based estimation of gross total resection vs subtotal resection was accurate 79.6% of the time compared to gold standard postoperative MRI, and estimates of extent of resection improved from 72.6% to 84.4% over a 17-year period, highlighting the learning curve of intraoperative MRI resection estimations.28 To the authors' knowledge, no other head-to-head comparison exists between intraoperative and postoperative MRI. Current statistics on performance rates of intraoperative or postoperative gadolinium-enhanced MRI for glioma are not available. It is anticipated that by measuring performance, a treatment gap will be confirmed and further opportunities for improvement will be identified.

Venous thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common complication of systemic malignancies, and is the second leading cause of death among patients with cancer.29,30 Patients with brain tumors, especially glioblastoma, are at an increased risk of VTE compared to other types of cancer.31,32 While trials of long-term prophylactic anticoagulation have not demonstrated significant reductions in VTE risk among high-grade glioma patients,33 perioperative inpatients are considered to be at especially high risk of VTE due to the addition of both immobility and systemic inflammation to an already prothrombotic oncologic state. Compression stockings are generally used as a low-risk option for VTE prevention perioperatively, yet high rates of VTE are seen even with their use.9 Notably, 2 prospective clinical trials have shown safety and improved efficacy in adding low molecular weight heparins to pneumatic devices,34,35 though the majority of patients still do not receive chemoprophylaxis after brain tumor surgery.36 Based on the strong data regarding VTE prophylaxis, yet the immeasurable complexity of provider decision for any one patient, an outcome measure was proposed to determine the actual rate of inpatient perioperative VTE development. Since approval of the measure specifications, Senders et al.37 assessed VTE rates following craniotomy for a primary malignant brain tumor through extraction of National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data. The work group hopes that through implementation of the developed quality measure real-time data will be available for clinicians to assess and address VTE rates following resection and biopsy for grade III–IV gliomas.

The work group explored multiple alternate measure topics (appendix e-1, links.lww.com/WNL/A302) addressing various other practice patterns and clinical processes. Ultimately these measures were not developed for a variety of reasons, including difficulty capturing data due to current electronic medical records practices, lack of evidence, lack of a known gap in care practice, and development of similar measures by others in related fields. These concepts will be retained for future measurement set updates, as more evidence may support development at that time.

Methods

The AAN is an established measure developer and steward of quality measures for neurologists. Details of the AAN's full measure development process are available online.38 AAN and SNO worked in partnership to develop a de novo set of quality measures for neuro-oncology, and in so doing, piloted an expedited, virtual version of the measure development process. This expedited process included simultaneous completion of an evidence-based literature search by a medical librarian and identification of members of the multidisciplinary work group, all of whom adhered to the AAN conflict of interest policy. Work group members were selected by the AAN's Quality and Safety Subcommittee (QSS) measure development leadership team through a process that reviewed relevant clinical experience, prior exposure to or work in quality measure development or quality improvement, and potential conflicts. The final work group comprised 9 members representing multi-stakeholder interests for patients with neuro-oncology conditions. The call for work group members did not result in identification of any potential patients or caregivers. One QSS member served as a nonvoting methodologic facilitator.

Once the work group was constituted, members drafted candidate measures with attendant technical specifications, identified measures ripe for development via a modified Delphi process, and refined candidate measures via teleconference meetings. The work group focused their efforts on measures that arose from known treatment gaps (allowing for opportunity to improve) with evidence or guideline statements to support existing standards of care, had high face validity, and were feasible to collect. Candidate measure concepts were extensively reviewed and edited prior to a work group vote to approve, reject, or abstain on each measure during teleconference meetings.

Subsequent to this preliminary work group approval, a 21-day public comment period resulted in input from 22 individuals, a similar number to public input for previous measure development efforts. Efforts were made to publicize this opportunity both to patients and to caregivers in the interest of identifying meaningful measures. Following public comment, measure concepts were further refined prior to measurement set approvals by the work group, the AAN QSS, the SNO Guideline Committee, the AAN Practice Committee, the SNO Board of Directors, and the AAN Institute Board of Directors.

The AAN and SNO will update these measures as needed every 3 years, allowing the measurement set to provide a working framework for measurement, rather than a long-term mandate.

Results

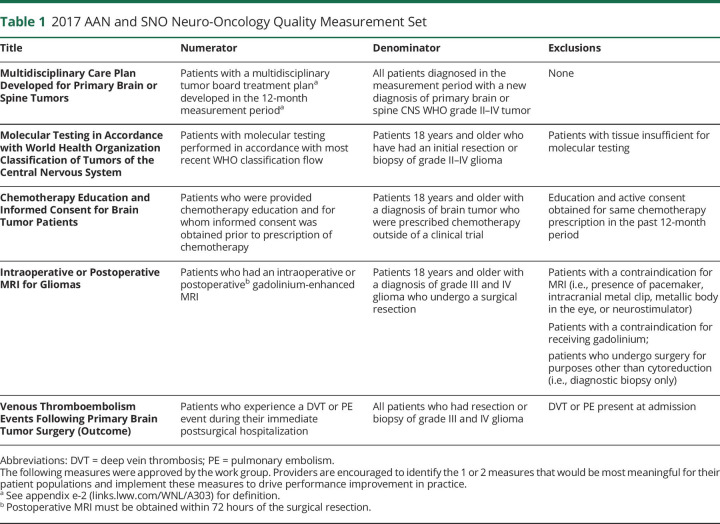

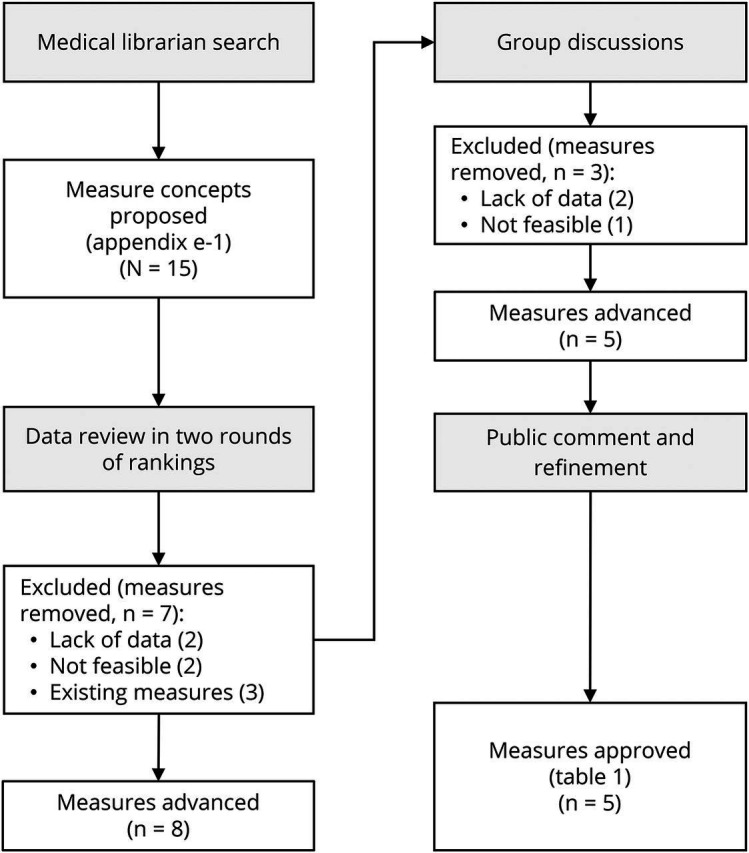

The workflow of group measure proposal, evaluation, and development is shown in the figure. The process began with a literature review by a medical librarian, identifying 1,052 relevant abstracts, 25 potential guidelines or systematic reviews, and 60 articles providing supporting evidence. After work group members reviewed the literature outlining care gaps and AAN quality measure requirements (available at aan.com/practice/quality-measures/ and in appendix e-2, links.lww.com/WNL/A303), the group proposed 15 initial concepts for evaluation (appendix e-1, links.lww.com/WNL/A302). Three items that were duplicative of other national organizations' quality measures were omitted. Then, a second literature review focused on level of evidence for the remaining proposed measures, and 4 additional measures were omitted owing to insufficient evidence. Finally, group discussion determined that electronic medical record data extraction for 3 more measures would be prohibitively challenging for clinicians and organizations, and so these were omitted. In the end, the group delineated 5 areas that were feasible for measure development, as they had support from scientific literature and evidence of gaps in care. These concepts were refined through an iterative development process, submitted for public comment, and ultimately approved by the work group and governing bodies of AAN and SNO (table 1). While 4 of these measures focus on the process of providing evidence-based neuro-oncologic care, the fifth measure is an outcome measure, determining the incidence of VTE after high-grade glioma resection or biopsy. The work group believed that, while the use of postoperative VTE prophylaxis was nearly ubiquitous, practice patterns regarding mechanical or chemical VTE prophylaxis may vary by provider or be influenced by patient factors that cannot be easily captured through electronic medical record. As such, the work group determined that measuring the outcome of postoperative VTE incidence would be the most effective gauge of quality neuro-oncologic care. It should be noted that screening for VTE in asymptomatic patients is not recommended; this outcome measure is based on VTE identification on imaging performed for clinical suspicion.

Figure. Measure development flow diagram.

Illustration of measure proposals, discussion, research, evaluation, and approval.

Table 1.

2017 AAN and SNO Neuro-Oncology Quality Measurement Set

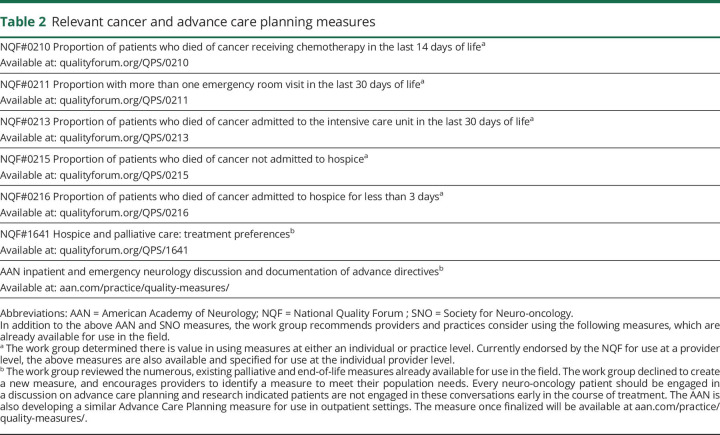

The work group also identified 5 previously developed measures complementary to this effort (table 2) that are endorsed here for consideration in the delivery of neuro-oncologic care.

Table 2.

Relevant cancer and advance care planning measures

From the time of the initial meeting to Board approvals, development of this measurement set took 10 months (July 2016–April 2017). This compares to the historical average time of 18 months for completion of the AAN measure development process. Based on measurement set approval by 2 professional societies with a marked decrease in turnaround time, similar number of measures developed, and similar amount of public commentary, the work group determined the expedited, virtual measure development process to be an appropriate surrogate for previously published processes.

Discussion

The goal of quality measures is to guide their users to evidence-based improvements in care and, eventually, health care outcomes. It is the hope of this work group that implementation of the new neuro-oncology measures will lead to objective improvements in the care of patients diagnosed with CNS tumors. There is no requirement that all measures be used by a provider or hospital. In fact, implementation of all measures at one time would likely not be feasible for providers. Instead, providers, practices, and hospitals are encouraged to identify the 1 or 2 measures that would be most meaningful for their patient populations. After collecting data, providers are encouraged to use data to drive performance improvement in practice.

Public comments and work group discussions addressed potential unintended consequences, including rising care costs and use of clinically unwarranted procedures. Commenters noted risks of manipulating data or changing practice patterns in order to avoid the perception of failure for various measures. The work group created these measures with the primary intention of improving clinical practice, understanding that providers act with best intentions to do no harm. The inclusion of an outcome measure in this set creates an opportunity for improvement even for high-volume neuro-oncology institutions that might otherwise achieve the named process measures nearly perfectly. However, perfection is not anticipated for any measure; instead, performance data should serve as an internal benchmark for provider, practice, and hospital quality improvement opportunities.

These data may highlight practice changes that providers can make to improve quality of patient care (e.g., using nurse educators to provide chemotherapy education or better documentation of informed consent procedures). Should performance rates near perfect compliance, the work group will evaluate the continued need for these measures during the next scheduled update. Future measures from this group may also include the provision of patient-reported outcomes in routine clinical practice, which may inform better decisions by patients and providers.12 Although there are no immediate plans to implement these measures in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Merit-based Incentive Payment System or private payers' performance tracking systems, it may occur in the future. Measures may be considered for use in AAN's Axon Registry, and may also be developed for use as Improvement in Medical Practice modules for American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology Maintenance of Certification requirements. Measures will be periodically evaluated every 3 years and updated as necessary to reflect continued utility in quality neuro-oncology care.

Glossary

- AAN

American Academy of Neurology

- QSS

Quality and Safety Subcommittee

- SNO

Society for Neuro-oncology

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

Author contributions

Dr. Jordan contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and study supervision including responsibility for conduct of research and final approval. Dr. Sanders contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and study supervision including responsibility for conduct of research and final approval. Dr. Armstrong contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, and drafting/revising the manuscript. Dr. Asher contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, and drafting/revising the manuscript. A. Bennett contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, and study supervision including responsibility for conduct of research and final approval. Dr. Dunbar contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, and drafting/revising the manuscript. Dr. Mohile contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, and drafting/revising the manuscript. Dr. Nghiemphu contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, and drafting/revising the manuscript. Dr. Smith contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, and drafting/revising the manuscript. Dr. Ney contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and/or interpretation of data, drafting/revising the manuscript, critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and study supervision including responsibility for conduct of research and final approval.

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

J. Jordan reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. A. Sanders serves as a member of the National Quality Forum Palliative and End-of-Life Standing Committee. T. Armstrong reports no current conflicts; prior to October 30, 2016, served as consultant for AbbVie Pharmaceuticals, Tocagen, Pfizer, and Immunocellular Therapeutics, and received funding from Genentech and Merck. T. Asher, A. Bennett, and E. Dunbar report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. N. Mohile has received consulting fees from Novocure. P. Nghiemphu, T. Smith, and D. Ney report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Xu J, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2009–2013. Neuro Oncol 2016;18(suppl 5):v1–v76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter KR, McCarthy BJ, Freels S, et al. Prevalence estimates for primary brain tumors in the United States by age, gender, behavior, and histology. Neuro Oncol 2010;12:520–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute. Available at: seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/. Accessed April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inskip PD, Tarone RE, Hatch EE, et al. Sociodemographic indicators and risk of brain tumours. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aneja S, Khullar D, Yu JB. The influence of regional health system characteristics on the surgical management and receipt of post operative radiation therapy for glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol 2013;112:393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curry WT, Barker FG. Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the treatment of brain tumors. J Neurooncol 2009;93:25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherwood PR, Dahman BA, Donovan HS, et al. Treatment disparities following the diagnosis of an astrocytoma. J Neurooncol 2011;101:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riblet NB, Schlosser EM, Homa K, et al. Improving the quality of care for patients diagnosed with glioma during the perioperative period. J Oncol Pract 2014;10:365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riblet NBV, Schlosser EM, Snide JA, et al. A clinical care pathway to improve the acute care of patients with glioma. Neuro Oncol Pract 2016;3:145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norden AD. Welcoming the era of quality improvement in neuro-oncology. J Oncol Pract 2014;10:371–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman M, Neal D, Fargen KM, Hoh BL. Establishing standard performance measures for adult brain tumor patients: a nationwide inpatient sample database study. Neuro Oncol 2013;15:1580–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4249–4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright FC, De Vito C, Langer B, et al. Expert panel on multidisciplinary cancer conference standards. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: a systematic review and development of practice standards. Eur J Cancer 2007;43:1002–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. 2016:84. Available at: facs.org/∼/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/2016%20coc%20standards%20manual_interactive%20pdf.ashx. Accessed September 6, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutterbach J, Pagenstecher A, Spreer J, et al. The brain tumor board: lessons to be learned from an interdisciplinary conference. Onkologie 2005;28:22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenblum ML, Mikkelsen T. Developing a brain tumor center. J Neurooncol 2004;69:181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:e267–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathologica 2016;131:803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neuss MN, Polovich M, McNiff K, et al. 2013 updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards including standards for the safe administration and management of oral chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract 2013;9(2 suppl):5s–13s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwappach DLB, Wernli M. Medication errors in chemotherapy: incidence, types and involvement of patients in prevention: a review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care 2010;19:285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storm C, Casillas J, Grunwald H, et al. Informed consent for chemotherapy: ASCO member resources. J Oncol Pract 2008;4:289–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zerillo JA, Pham TH, Kadlubek P, et al. Administration of oral chemotherapy: results from three rounds of quality oncology practice initiative. J Oncol Pract 2015;11:2255–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg 2001;95:190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanai N, Poley MY, McDermott MW, et al. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Neurosurg 2011;115:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2016 Central Nervous System cancers. 2016. Available at: nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. Accessed October 14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stupp R, Brada M, van den Bent MJ, et al. ; On behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group. High-grade glioma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014;25:iii93–iii101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majós C, Cos M, Castañer S, et al. Early post-operative magnetic resonance imaging in glioblastoma: correlation among radiological findings and overall survival in 60 patients. Eur Radiol 2016;26:1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau D, Hervey-Jumper SL, Han SJ, et al. Intraoperative perception and estimates on extent of resection during awake glioma surgery: overcoming the learning curve. Neurosurg 2017:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Posner JB. Neurologic Complications of Cancer. Contemporary Neurology Series. Philadelphia: Davis; 1995:482. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luzzatto G, Schafer AI. The prethrombotic state in cancer. Semin Oncol 1990;17:147–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kakkar AK, Levine M, Pinedo HM, et al. Venous thrombosis in cancer patients: insights from the FRONTLINE survey. Oncologist 2003;8:381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Streiff MB, Ye X, Kickler TS, et al. A prospective multicenter study on venous thromboembolism in patients with newly-diagnosed high-grade glioma: hazard rate and risk factors. J Neurooncol 2015;124:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry JR, Julian JA, Laperriere NJ, et al. PRODIGE: a randomized placebo-controlled trial of dalteparin low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed malignant glioma. J Thromb Haemost 2010;8:1959–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurmohamed MT, van Riel AM, Henkens CM, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and compression stockings in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in neurosurgery. Thromb Haemost 1996;75:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agnelli G, Piovella F, Buoncristiani P, et al. Enoxaparin plus compression stockings compared with compression stockings alone in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after elective neurosurgery. NEJM 1998;339:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang SM, Parney IF, Huang W, et al. Patterns of care for adults with newly diagnosed malignant glioma. JAMA 2005;293:557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senders JT, Goldhaber NH, Cote DJ, et al. Venous thromboembolism and intracranial hemorrhage after craniotomy for primary malignant brain tumors: a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis [online]. J Neurooncol 2018;136:135–145. Available at: link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11060-017-2631-5.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quality and Safety Subcommittee. American Academy of Neurology quality measurement manual 2014 update. 2015:21. Available at: aan.com/policy-and-guidelines/quality/quality-measures2/how-measures-are-developed/. Accessed January 10, 2018.