ABSTRACT

The adaptive response of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to acid stress, a major stressor in juice processing environments, has been shown to confer cross-resistance against pasteurization methods such as heat and X-ray. However, whether acid adaptation confers resistance against high-pressure processing (HPP) has not been explored. This study aimed to investigate the effect of acid adaptation on the pressure resistance of E. coli O157:H7 in a bok choy vegetable juice matrix. Acid adaptation was performed in tryptone soya broth without dextrose adjusted to pH 5.0 at 37°C for 24 h, while non-adapted cells were prepared in similar conditions, without the pH adjustment (pH 7.3). The C7927 strain was used as it exhibited the greatest increase in pressure resistance after acid adaptation among the three strains tested. Acid adaptation increased the D-value at 400 MPa from 0.8 ± 0.1 min in non-adapted cells to 1.2 ± 0.1 min in acid-adapted cells (P < 0.05). Furthermore, significantly lower reductions in total viable counts were observed after 72 h of post-HPP refrigerated storage for acid-adapted cells (3.4 ± 0.2 log CFU/mL) as compared to non-adapted cells (5.0 ± 0.1 log CFU/mL). Sublethally injured populations were measured via plating on selective media, as well as differential fluorescent staining and flow cytometry. The levels of damages to membrane, DNA, proteins, and peptidoglycan were significantly lower in acid-adapted cells, suggesting that the acid adaptive response of E. coli O157:H7 may protect it against HPP-induced inactivation and injury by modulating the pressure resistance of these cellular targets.

IMPORTANCE

Based on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulations, E. coli O157:H7 is a pertinent pathogen in high acid juices that needs to be inactivated during the pasteurization process. The results of this study suggest that the effect of acid adaptation should be considered in the selection of HPP parameters for E. coli O157:H7 inactivation to ensure that pasteurization objectives are achieved.

KEYWORDS: acid adaptation, Escherichia coli O157:H7, sublethal injury, differential fluorescent staining, flow cytometry, alkaline phosphatase

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is a major foodborne pathogen that has a low infective dose and the ability to cause the life-threatening hemolytic-uremic syndrome. As it has previously been associated with outbreaks involving juice products (1 – 3), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has declared it a pertinent pathogen of interest and designated that the operating conditions employed for juice pasteurization must achieve a 5-log reduction in the E. coli O157:H7 count (4). To achieve this processing target, juices have traditionally been thermally pasteurized. However, heat treatment compromises the juices’ organoleptic properties and nutrient content. As modern consumers’ demand for minimally processed foods with better flavor and higher nutritional value, non-thermal pasteurization technologies for juices have been rapidly gaining traction (5). Among these, high-pressure processing (HPP) is currently the most widely utilized on a commercial scale (6) and has been accepted as an alternative pasteurization method for fruit and vegetable juices in many countries such as the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (7).

Acid stress is one of the major stressors that microorganisms encounter in juice-processing environments, especially in processing lines or equipment which are constantly exposed to low pH fluids. E. coli cells have been shown to be capable of developing an adaptive response to enhance their survival in acidic environments (8). Concerningly, this adaptive response has also been demonstrated to confer cross-resistance against various food pasteurization processes, such as heat (9, 10), gamma irradiation (11), X-ray (12), UV (13), and ultrasound (14). For instance, while 0.66 ± 0.03 kGy of X-ray irradiation was sufficient to achieve a 5-log reduction of non-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells, a higher dosage (0.92 ± 0.09 kGy, P < 0.05) was required when cells were acid adapted (12). Similarly, the dose of UV irradiation required to achieve a 5-log reduction in acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells was 1.8 times that of non-adapted cells when tested in an apple juice matrix (P < 0.05) (13).

However, despite the commercial relevance of HPP as a juice pasteurization technology, there has not been any documentation on the effect of acid adaptation on the pressure resistance of E. coli O157:H7. This study, hence, aimed to investigate the effect of acid adaptation on the resistance of E. coli O157:H7 to high-pressure processing in a bok choy (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) juice matrix. At the same time, it sought to understand this effect mechanistically through the selective inhibition of metabolic targets such as the cell membrane, DNA, proteins, and peptidoglycan. Differential fluorescent staining and flow cytometry were used to characterize the cell membrane, specifically its integrity and the functionality of its bound proteins. Also elucidated was the effect on a periplasmic protein that is not bound to the membrane, i.e., the alkaline phosphatase enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, stock cultures, and acid adaptation

Three E. coli O157:H7 strains—EDL 931/ATCC 35150 (human feces), EDL 933 (raw hamburger meat), and C7927 (patient in apple cider outbreak)—were obtained from the bacterial culture collection of the Department of Food Science and Technology, National University of Singapore (Singapore). All strains were stored at −80°C in cryogenic vials with porous beads (CryoInstant, Deltalab, Barcelona, Spain). Cells were streaked on tryptone soy agar (TSA, Thermo Scientific Microbiology Pte Ltd., Singapore) plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Plates were stored at 4°C for up to 2 weeks. Single colonies were sub-cultured in tryptone soy broth (TSB, Thermo Scientific Microbiology Pte Ltd., Singapore), with at least two consecutive cycles of incubation at 37°C for 24 h prior to further use.

The acid adaptation protocol was adapted from Lim and Ha (12). Briefly, to prepare acid-adapted cells, a 0.1-mL aliquot of culture was inoculated into 10 mL of TSB without dextrose (TSB w/o D) whose pH was adjusted to 5.0 using 6 N HCl. To prepare non-adapted control cells, a 0.1-mL aliquot was inoculated into 10 mL of TSB w/o D without any pH adjustment (i.e., pH 7.3). The reason for using TSB w/o D instead of TSB was to prevent the inadvertent adaptation of control cells to any acids that may be produced from dextrose fermentation. Similar populations were achieved after incubation for both acid-adapted and non-adapted cultures (~11 log CFU/mL). Both types of cultures were subsequently incubated at 37°C for 24 h, after which cell pellets were recovered via centrifugation at 8,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min.

Sample preparation and inoculation

Bok choy (Sky Greens Pte Ltd., Singapore) was juiced using a Goodnature X-1 mini cold press juicer (New York, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The juice was adjusted to pH 4.0 using citric acid, as the FDA advises that low acid juices (pH >4.6) should be acidified to improve food safety (4). The original pH of the juice was measured to be 6.05 ± 0.08. After acidification, the juice was stored at −20°C until use. On each day of use, the juice was thawed at 4°C and sterilized through a 0.22-µm sterile polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter. It was verified that this filtration step was sufficient to remove natural microflora—no growth was observed when undiluted samples were plated on TSA during preliminary trials. The pelleted cells were resuspended in bok choy juice to a final concentration of 1010 CFU/mL, as determined through plating on TSA. The inoculated juice (5 mL) was then packed into sterile polyethylene pouches and sealed without headspace. The pouches were vacuum packed into a polyamide/polyethylene secondary bag to prevent contamination of the HPP unit in case of leakage.

High-pressure processing treatment

Samples were kept in ice water (0–2°C) throughout transportation to and from the HPP facility. HPP was conducted at 400 MPa and a set temperature of 5°C using a Hiperbaric 300 unit (Hiperbaric, Burgos, Spain). This pressure was selected as it is generally the minimum pressure used for juice production (15). The time required by the machine to reach 400 MPa ranged between 2 min 30 s and 2 min 40 s and is known as the come-up time (CUT). Depressurization was instantaneous. The holding time was defined as the time spent isostatically at 400 MPa, i.e., treatment for 0 min refers to depressurization immediately once 400 MPa has been achieved and only includes the CUT.

Comparison between E. coli O157:H7 strains

Bok choy juice samples inoculated with three single strains individually were subjected to HPP treatment for 2 min. Following treatment, 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared with 0.1% peptone water, and 0.1 mL of the diluted sample was spread-plated onto TSA. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24–48 h (i.e., plates were counted after 24 and 48 h to capture both fast- and slow-growing colonies). The final count reported is based on the colony count after 48 h. The reduction in total survivors was determined by comparing the colony counts post-HPP against that of an untreated control.

Process lethality and decimal reduction time

For deeper investigation, the C7927 strain was selected as it exhibited the greatest increase in pressure resistance after acid adaptation. Inoculated juice was treated for 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 min, and total survivors were enumerated by spread plating on TSA.

The pressure inactivation kinetics of acid-adapted and non-adapted cells during the holding time were analyzed using a first-order reaction equation:

| (1) |

where N is the final cell population (CFU/mL) after treatment at 400 MPa, t is the pressure holding time in minutes, N0 is the initial cell population (CFU/mL) without treatment, and D is the decimal reduction time, defined as the time (minutes) required to achieve a 10-fold reduction in cell concentration at this pressure (400 MPa).

The curves were evaluated for their goodness of fit using their coefficient of determination (R 2) and the root mean square error (RMSE), which were calculated in the following manner:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where SSres is the residual sum of squares, SStot is the total sum of squares, is the predicted value for the ith observation, yi is the observed value for the ith observation, and n is the number of data points.

Curve fitting and analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., California, USA). As each data point came from an individual run of the HPP machine, all the data points were independent of each other (i.e., 7 treatment durations × 3 replicates = 21 independent data points). Therefore, curve fitting was done on the pooled data set instead of on individual trials.

Fate of cells during storage

To determine the fate of sublethally injured cells during storage, juice samples treated for 1 min were stored at 4°C, and aliquots were spread plated on TSA every 24 h to detect changes in the counts of total survivors.

Sublethal injury to the cell membrane

The same set of samples used for process lethality testing was simultaneously spread plated onto selective agar prepared by supplementing TSA with an optimal concentration of NaCl. The optimal NaCl concentration was defined as the maximum concentration that did not inhibit the growth of healthy E. coli O157:H7 C7927 cells (i.e., no difference between TSA and NaCl-supplemented plates) and was determined to be 2% (wt/vol, data not shown). Plates were counted after incubation at 37°C for 24–48 h.

Damage to cell membrane integrity and membrane proteins

Inoculated juice samples were treated at 400 MPa for 0 and 2 min, and cells were pelletized via centrifugation at 8,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min. The pellets were then washed twice with 0.1% peptone water and resuspended in 0.1% peptone water to achieve ~106 CFU/mL suspensions. Damage to cell membrane integrity and membrane protein function was investigated using four fluorescent probes—SYTO9 and propidium iodide (PI) from the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), ethidium bromide (EtBr, Sigma-Aldrich, Singapore), bis-(1,3-dibutylbarbituric acid), and 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-NBDG, Life Technology Holdings Pte Ltd, Singapore). Aliquots were stained with two mixed probes (SYTO9/PI and SYTO9/EtBr) and a single probe (2-NBDG). Probes were added to achieve final concentrations of 5, 30, 30, and 10 µM for SYTO9, PI, EtBr, and 2-NBDG, respectively. The mixtures were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 min, except 2-NBDG, which was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Flow cytometry was conducted using a CytoFLEX LX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, California, USA). The excitation wavelength was 488 nm, while the detection wavelength was 525/40 nm for SYTO9, DIBAC4, and NBDG, and 610/20 nm for PI and EtBr.

Sublethal injury to the peptidoglycan layer, protein, and DNA

Inoculated juice samples were treated at 400 MPa for 1 min and spread plated onto selective agar prepared using TSA supplemented with 12.5 µg/mL penicillin G, 6 µg/mL chloramphenicol, and 1.5 µg/mL nalidixic acid. These metabolic inhibitors were used to detect peptidoglycan, protein, and DNA damage, respectively (16). Similar to NaCl, these concentrations were determined through preliminary experiments to be the maximum non-inhibitory concentration that did not inhibit the growth of non-stressed E. coli O157:H7 C7927 cells. The treatment duration of 1 min was selected as it resulted in the greatest proportion of sublethally injured cells while ensuring that plate counts on NaCl-supplemented plates remained above the detection limit (1 log CFU/mL). The proportion of sublethally injured cells was calculated as the difference between the log reduction on the selective medium and the log reduction on TSA.

Damage to non-membrane proteins

Inoculated juice samples were treated at 400 MPa for 0 and 2 min, and the cells were pelletized by centrifugation at 8,000 × g and 4°C for 5 min. The pelleted cells were washed twice with 0.1% peptone water and resuspended in 0.1% peptone water to their initial concentration (1010 CFU/mL). The alkaline phosphatase activity was determined as per Amoozadeh et al. with minor modifications (17). Briefly, 20 µL of the bacterial suspension was added to 80 µL of 0.1 M pH 8.5 Trizma buffer and 20 µL of 150 mM disodium p-nitrophenyl phosphate in a 96-well microplate. After 4 h of incubation at 37°C, 80 µL of 0.5 M NaOH was added to each well, and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured. Change in absorbance over the 4-h period ( ) was determined via comparison against a sample blank consisting 20 µL of water instead of the disodium p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate. A control blank was also performed by substituting the bacterial suspension with 20 µL of 0.1% peptone water. Reduction in enzyme activity was determined using the following equation:

| (4) |

where ∆ANo HPP, ∆AHPP, and ∆AControl blank represent the change in absorbance at 405 nm after 4 h of incubation in the untreated sample, HPP-treated sample, and control blank, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise stated, all statistical analyses were conducted with R 4.0.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). A Student’s t-test was used to compare the outcomes at each pressure holding time between the acid-adapted and control cells, while a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used to compare between treatments across different pressure holding times. Three independent trials were conducted for all analyses (i.e., n = 3), and all plating was conducted in duplicate. All data have been expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

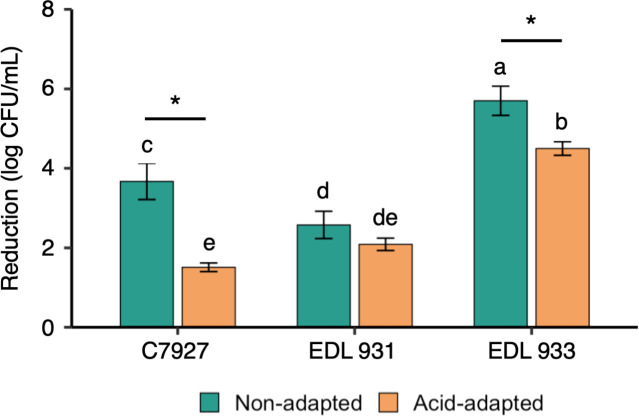

Relative susceptibility of different E. coli O157:H7 strains after acid adaptation

From Fig. 1, it can be seen that the effect of acid adaptation on pressure resistance was strain dependent. While acid adaptation more than halved the log reduction for C7972, the difference between the non-adapted control and acid-adapted cells for EDL 931 was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). As a result, while EDL 931 was the most pressure resistant among the non-adapted cells, C7927 was the most pressure-resistant strain among the acid-adapted cells. As the C7927 strain exhibited the greatest difference in pressure resistance with acid adaptation, it was chosen for further analysis.

Fig 1.

Effect of HPP at 400 MPa for 2 min on three strains of non-adapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 cells. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference between non-adapted and acid-adapted cells for each strain (P < 0.05). Different letters indicate a statistically significant difference among the log reduction values across the three strains and treatments (P < 0.05).

Process lethality and decimal reduction time of E. coli O157:H7 C7927

No significant differences in process lethality were observed between non-adapted and acid-adapted cells after the come-up time, as evidenced by the similarity in populations at a holding time of 0 min (P > 0.05). However, the reduction observed in acid-adapted cells was significantly lower than that of non-adapted cells at all subsequent pressure holding times (Fig. 2), suggestive of a higher pressure resistance. To further quantify the difference in pressure resistance, the data points were fitted with the first-order kinetic model, which has widely been used to describe HPP-induced microbial inactivation at isobaric conditions (15, 18, 19). The D-values, R 2, and RMSE of the fitted curves have been presented in Table 1. The first-order kinetic model fitted the data set well, with high R 2 (>0.9) and low RMSE (<15% of mean) values. Based on the fitted curves, the D-value at 400 MPa of acid-adapted cells was 31.4% higher than that of non-adapted cells (P < 0.05).

Fig 2.

Inactivation curves of non-adapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 at 400 MPa. Curves were fitted based on first-order kinetics. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference between non-adapted and acid-adapted cells at each specific time point (P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of D-values from non-adapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 at 400 MPa and 5°C

| D-value a | R 2 | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-adapted | 0.898 ± 0.055 b | 0.944 | 0.476 |

| Acid adapted | 1.18 ± 0.06 a | 0.962 | 0.295 |

The D-value has been presented as the best fit value ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase alphabet superscripts indicate a significant difference between non-adapted and acid-adapted cells (P < 0.05) based on a Student’s t-test.

Fate of cells during storage

To better compare the rates of decrease in total survivors between acid-adapted and non-adapted cells during storage, the reduction was expressed relative to the count immediately after processing (0 h of storage). Regardless of whether cells were acid adapted or not, total survivors decreased over storage (Fig. 3). Notably, the decrease in total survivors was slower when cells were acid adapted. While total survivors in the non-adapted population decreased by 5.0 log CFU/mL after 72 h of refrigerated storage, the reduction in total survivors experienced by acid-adapted cells was only 3.3 log CFU/mL. Meanwhile, total survivors in untreated cells, whether acid adapted or not, did not change during storage (P > 0.05).

Fig 3.

Reduction in total survivors during storage at 4°C normalized based on survivor counts immediately post processing. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference between non-adapted and acid-adapted cells after treatment at 400 MPa for 1 min at each specific time point (P < 0.05). Log counts of untreated cells did not change during storage (P > 0.05).

Sublethal injury to the cell membrane in E. coli O157:H7 C7927 cultures

Sublethal injury can be evaluated based on the difference between the plate counts on TSA, a non-selective medium that supports the growth of both healthy and sublethally injured cells (total survivors), and TSA supplemented with an optimal concentration of NaCl, a selective medium that only supports the growth of cells with unimpaired osmotolerant capacities, which is conferred by functional cytoplasmic membranes (20). Plate counts on both TSA and TSA supplemented with NaCl have been presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Reductions in cell counts of non-adapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 after treatment at 400 MPa on non-selective TSA and selective TSA + 2% NaCl a

| Pressure holding time (min) | Reduction in cell count (log CFU/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-adapted | Acid adapted | |||

| TSA | TSA + 2% NaCl | TSA | TSA + 2% NaCl | |

| 0 | 0.548 ± 0.368 C,c | 4.80 ± 0.42 A,b | 0.385 ± 0.279 C,c | 1.64 ± 0.35 B,c |

| 1 | 2.03 ± 0.47 C,b | 7.23 ± 0.44 A,a | 0.716 ± 0.180 D,c | 4.02 ± 0.64 B,b |

| 2 | 3.67 ± 0.46 B,a | >8 | 1.58 ± 0.20 C,b | 7.45 ± 0.46 A,a |

| 3 | 4.34 ± 0.46 A,a | >8 | 2.63 ± 0.24 B,a | >8 |

Different uppercase and lowercase superscripts indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) within each row and column, respectively.

Sublethal injury was detected within the come-up time itself. While a significant difference in the viable counts on TSA and TSA + 2% NaCl was observed for both types of cells, a much greater disparity was observed in the counts of the non-adapted cells (4.3 log CFU/mL) than the acid-adapted ones (1.3 log CFU/mL) after the come-up time (0-min holding time). The sublethally injured fraction continued to persist at all subsequent time points in both types of cells. Still, the acid-adapted cells demonstrated greater resistance to injury. With non-adapted cells, all survivors were sublethally injured within 2 min of pressure hold. On the other hand, 3 min of pressure hold was required to sublethally injure all survivors when acid adaptation was performed.

Damage to cell membrane integrity and membrane-bound proteins

To quantify cellular membrane damage, cells were stained with fluorescent probes, and the percentages of cells with compromised membrane function were calculated based on flow cytometry. From Fig. 4, it can be seen that significant membrane integrity loss as well as efflux pump and glucose uptake dysfunction were induced by both pressurization and the isostatic pressure hold at 400 MPa. The percentage of cells with membrane integrity, efflux pump activity, and glucose uptake activity loss significantly differed between untreated samples, samples treated for 0 min, and samples treated for 2 min for both non-adapted and acid-adapted cells (P < 0.05).

Fig 4.

Changes in membrane integrity and function of non-adapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 during treatment at 400 MPa. (a) Loss of membrane integrity measured with SYTO9/PI. (b) Loss of efflux pump activity measured with SYTO9/EtBr. (c) Loss of glucose uptake activity measured with 2-NBDG. Different letters indicate a statistically significant difference across the pressure holding times and treatments (P < 0.05).

Interestingly, while acid adaptation did not influence the membrane integrity and efflux pump activity of untreated cells, the loss of glucose uptake activity in the untreated control of non-adapted cells was 5.6 times that of acid-adapted cells (P < 0.05). This difference could largely be attributed to incubation in the juice matrix during transportation and processing. When the measurement was conducted immediately after inoculation, the contrast between non-adapted and acid-adapted cells was less striking, albeit still statistically significant (non-adapted = 6.6 ± 2.0%, acid adapted = 3.2 ± .7%, P = 0.049). With HPP treatment, acid-adapted cells consistently demonstrated higher levels of membrane integrity retention and lower levels of functional losses than non-adapted cells, across both pressure holding times (P < 0.05). As a result, it took 2 min of pressure hold to inflict damage to the acid-adapted culture equivalent to that experienced by the non-adapted culture during the come-up time alone (P > 0.05).

Sublethal injury specific to the peptidoglycan layer, protein, and DNA

Figure 5 shows the proportion of sublethally injured cells in the acid-adapted and non-adapted populations after treatment at 400 MPa for 1 min. Supplementation of penicillin G and nalidixic acid did not inhibit the growth of acid-adapted cells (P > 0.05) but resulted in significant growth inhibition in non-adapted cells (ca. 1.2 ± 0.4 and 1.0 ± 0.6 log CFU/mL, respectively). Only chloramphenicol inhibited the recovery of acid-adapted cells. Even so, the degree of recovery inhibition experienced by the acid-adapted cells was 0.9 log CFU/mL lower than that experienced by their non-adapted counterparts (P < 0.05).

Fig 5.

Sublethal injury in non-adapted and acid-adapted cells after treatment at 400 MPa for 1 min in the presence of metabolic inhibitors. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference between non-adapted and acid-adapted cells (P < 0.05). NS indicates that no significant differences were observed between plate counts on selective and non-selective media (P > 0.05).

Loss of alkaline phosphatase activity

Figure 6 summarizes the reduction in alkaline phosphatase activity experienced by non-adapted and acid-adapted cells during treatment at 400 MPa. Acid-adapted cells consistently demonstrated lower degrees of enzyme activity losses than non-adapted cells. After the come-up period (i.e., 0 min of treatment), the reduction in enzyme activity observed with non-adapted cells was 1.7 times that of acid-adapted cells (P < 0.05). Further reductions in enzyme activity were observed after the come-up period, and the final reduction in enzyme activity after the 2 min isostatic hold at 400 MPa was still significantly higher in non-adapted cells (53.4 ± 4.6%) than in acid-adapted cells (36.4 ± 5.5%).

Fig 6.

Loss of alkaline phosphatase activity in non-adapted and acid-adapted E. coli O157:H7 during treatment at 400 MPa. Different letters indicate a statistically significant difference across the pressure holding times and treatments (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The effect of acid adaptation on the pressure resistance of E. coli O157:H7 was first evaluated at a single pressure holding time using three strains, which is consistent with that suggested by the National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods for pathogen inactivation challenge studies (21). The pressure resistance of E. coli O157:H7 was observed to be enhanced by acid adaptation in a strain-dependent manner. This strain dependence has previously been observed with stressors such as acid (22, 23) and heat (10). For instance, while acid adaptation did not improve the survival of ATCC 43895 in acidified asparagus juice (pH 3.6) during storage at 7°C for 14 days (P > 0.05), it more than halved the reduction of ATCC 43889 (P < 0.05) (22). Although studies directly investigating the effect of acid adaptation on the resistance of E. coli O157:H7 to HPP have not been conducted, González-Angulo, Serment-Moreno, Clemente-García et al. studied the pressure resistance of 34 strains of E. coli O157:H7 in TSB supplemented with yeast extract (TSBYE) adjusted to pH 4.5 and 6.0, and observed that strains that exhibited the highest pressure resistance when pressurized in a pH 6.0 medium were not necessarily the most baro resistant in a pH 4.5 medium (24). While the cells were not pre-adapted to acid like in this study, the authors postulated that the presence of acid stress in the medium resulted in adaptive behaviors, with the increase in pressure resistance conferred by adaptation being strain dependent.

Dedicated process lethality studies on the most resistant strain—C7927—reiterated that acid-adapted cells were more resistant than non-adapted cells against HPP inactivation. In the only other study evaluating the effect of acid adaptation on the resistance of bacteria to HPP, Wouters et al. observed that Lactobacillus plantarum cells grown at pH 5.0 were more pressure resistant than cells grown at pH 7.0—the inactivation experienced by acid-adapted cells after treatment at 250 MPa and room temperature for 20 min was less than a third that of non-adapted cells (25). However, no statistical analysis was performed to ascertain this difference. Acid adaptation has also been shown to confer cross-resistance to other pasteurization technologies. For instance, while the D-value of E. coli O157:H7 from thermal treatment at 60°C in apple juice was 0.8 ± 0.1 min, acid adaptation increased it to 1.5 ± 0.4 min (9). Similarly, with ultrasound treatment involving frequencies switching between 28, 45, and 100 kHz at 1 ms time intervals and a maximum power output of 600 W, the D-value of acid-adapted cells was found to be 1.18 times that of non-adapted cells in apple juice (P < 0.05) (26). Results from the current study extend these findings to HPP and suggest that the processing time required to achieve the FDA requirement of a 5-log reduction of pertinent pathogens may be underestimated when non-adapted cells are used for HPP process validation.

Apart from immediate inactivation, the population of survivors was monitored over refrigerated storage at 4°C. The decrease in survivors over storage observed in this study was unsurprising and has previously been documented in the literature. For example, a study on apple juice treated at 550 MPa and 6°C for 2 min found a significant decrease in total survivors across six strains of E. coli O157:H7 after 24 h of storage at 4°C (27). Similarly, González-Angulo, Serment-Moreno, Clemente-García et al. treated 34 strains of E. coli O157:H7 in TSA supplemented with yeast extract (TSAYE) adjusted to pH 4.5 with citric acid at 500 MPa and 10°C for 1 min and observed that while the median viable cell concentration was 3.8 log CFU/mL immediately after treatment, the number of survivors further dropped below the detection limit (2 log CFU/mL) within 2 days of storage at 12°C (24). The current study further adds to the literature, demonstrating a heightened rate at which non-adapted survivors were inactivated during storage.

As inactivation during storage may be attributed to the elimination of cells which have been sublethally injured, sublethal injury was evaluated using the differential plating method, with TSA supplemented with NaCl as the selective medium. This is the most commonly used medium to detect sublethal injury, and the increase in osmotic pressure conferred by NaCl supplementation allows for the selective outgrowth of cells with intact and functional cytoplasmic membranes (20, 28). Based on this method, a sublethally injured fraction was detected after HPP, indicating that HPP was not a binary event. This has previously been demonstrated by González-Angulo et al.—of the 26 strains of E. coli O157:H7 which exhibited growth on non-selective TSAYE after treatment in TSBYE adjusted to pH 4.5 at 500 MPa and 10°C for 1 min, none managed to grow on selective TSAYE + 4% NaCl (24). Bozoglu et al. observed a similar phenomenon, where colonies were observed on non-selective TSA but not on selective violet red bile agar after plating E. coli O157:H7-spiked milk treated at 350 MPa and 45°C for 10 min (29).

Damage to the integrity and function of the cellular membrane was further investigated using differential fluorescence staining and flow cytometry. First, membrane integrity was evaluated using a combination of two nucleic acid binding probes—green fluorescing SYTO9, which penetrates both intact and damaged membranes, and red fluorescing PI, which only penetrates damaged membranes (30). The degree of membrane integrity damage can, hence, be evaluated based on the percentage of red fluorescing cells. The results, which suggested that acid adaptation enabled the cell to resist pressure-induced membrane disruption, were expected, given that a typical outcome of acid adaptation is an increase in the proportion of saturated fatty acids (13, 23) and the conversion of unsaturated fatty acids to cyclopropane fatty acids (31). These modifications facilitate tighter packing of the phospholipids in the membrane, contributing to a more compact, stiffer membrane. These changes have also been shown to confer increased resistance to pressure inactivation (32, 33).

To detect membrane-bound efflux pump activity, a mixed probe with SYTO9/EtBr was used. EtBr is a red fluorescing probe that is actively transported out of the cell via a non-specific proton transport system. Red fluorescence would, hence, be an indicative of pump dysfunction (30). Additionally, a fluorescent glucose analog, 2-NBDG, was used to detect disruptions in the glucose uptake activity. As 2-NBDG is transported into the cell through the glucose-specific phosphoenolpyruvate-phosphotransferase system, cells with disrupted glucose uptake enzymes would lack fluorescence. Both techniques yielded similar trends, with acid-adapted cells retaining higher levels of enzyme activity than non-adapted cells.

While NaCl supplementation may be the most common selective agent used to detect sublethal injury, it may not be sufficient to characterize HPP-induced injury as HPP has been demonstrated to affect multiple cellular functions—pressures above 100 MPa can induce partial protein denaturation; pressures above 200 MPa can damage the membrane, alter the internal cellular structure, and cause nucleoid condensation; and pressures above 300 MPa can induce irreversible denaturation of proteins (34 – 36). As will be further discussed, acid adaptation may also confer a protective effect on these cellular components. Therefore, other types of sublethal injury were further investigated using metabolic inhibitors targeted at specific sites of damage.

First, to detect DNA damage, a selective medium containing nalidixic acid was employed. Nalidixic acid is a bacteriostatic antibiotic that prevents DNA replication and repair by binding to DNA gyrase (16). It was seen that while lower levels of growth were observed with nalidixic acid supplementation in non-adapted cells, nalidixic acid did not affect the growth of acid-adapted cells after HPP treatment. This suggests that the acid adaptive response protected cells against HPP-induced sublethal DNA damage. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is the upregulation of dps as part of the acid adaptive response. Tucker et al. observed that as compared to cells grown at pH 7.4, E. coli MG1655 cells grown at pH 4.5 had heightened expression of dps, with a log induction ratio of 0.780 (P < 0.05) (37). Dps is a DNA-binding protein that protects DNA against damage by physically shielding it from deleterious agents and co-crystalizing to maintain its integrity (38). This hypothesis is supported by findings by Malone et al., who subjected E. coli K-12 and its isogenic dps mutant to pressure treatment at 400 MPa for 5 min and observed that dps mutants were significantly less pressure tolerant than their wild-type counterpart, with a 1.7-log CFU/mL difference in survivor ratio (39).

Next, protein damage was investigated using chloramphenicol, which disrupts protein synthesis by binding to the 50S subunit of ribosomes (16). Based on these results, lower levels of sublethal protein damage were observed in acid-adapted cells than non-adapted cells after HPP treatment. Apart from generic protein damage, the activity of alkaline phosphatase, which accounts for up to 6% of total protein in E. coli (40), was also determined using an enzyme kinetic assay. Similarly, acid-adapted cells retained higher levels of enzyme activity post-HPP. Together with the results from the glucose uptake and efflux pump activity assays, these results suggest that the protective effect against protein damage conferred by the acid adaptive response extends to both soluble and membrane proteins. HPP-induced protein damage can largely be attributed to the unfolding and assembly of proteins into insoluble aggregates, which occurs upon exposure to pressures above 200 MPa (41). Acid adaptation has been known to upregulate chaperones that stabilize the structure of proteins, explaining the cross-resistance observed to HPP. For example, the growth of E. coli MG1655 in minimal media acidified to pH 4.5 has been shown to upregulate the expression of HdeA, with a log induction ratio (i.e., ratio of experimental to control gene expression levels, with positive values indicating upregulation) of 1.187 when compared to cells grown at pH 7.4 (P < 0.05) (37). As HdeA binds to proteins, preventing aggregation and facilitating their resolubilization and renaturation (42), its upregulation may confer enhanced stability during pressurization.

As the primary component of the periplasm, the peptidoglycan layer confers mechanical rigidity to maintain the cellular structure of bacterial cells. It was hypothesized that HPP may damage the peptidoglycan layer, as the upregulation of peptidoglycan synthesis genes has been observed in Listeria monocytogenes post processing at 400 MPa (43). Damage to this layer was, hence, investigated using penicillin G, which prevents the transpeptidation on peptidoglycan strands, inhibiting the growth of cells with damaged peptidoglycan layers (16). It was observed that acid-adapted cells experienced lower levels of peptidoglycan damage than non-adapted cells, and this may be due to the upregulation of peptidoglycan synthesis, which has been observed with exposure to acid stress in E. coli (44). As most studies investigating the peptidoglycan layer focused primarily on Gram-positive bacteria, there is little information on HPP-induced peptidoglycan damage in E. coli, and more studies are required to understand its implications on the viability of Gram-negative cells.

The possible mechanisms behind this cross-protective effect conferred by acid adaptation have been summarized in Fig. 7. Among these changes, it is interesting to note that while HPP did induce sublethal injury to the other cellular targets, namely DNA, protein, and the peptidoglycan layer, it is evident that after treatment at 400 MPa for 1 min, the largest proportion of cells was sensitized to NaCl.

Fig 7.

Schematic summarizing the possible mechanisms on how the acid adaptive response may confer cross-resistance against HPP.

Conclusion

In conclusion, acid adaptation increased the resistance of E. coli O157:H7 to HPP treatment at 400 MPa. Not only did acid adaptation increase the D-value, and hence, processing time required to achieve the 5-log reduction required of pasteurization processes, acid-adapted cells that survived the treatment were not eliminated as quickly as their non-adapted counterparts. The mechanism behind this cross-resistance appears to be multifaceted, with acid adaptation conferring protective effects against HPP-induced membrane, protein, DNA, and cell wall injury. The protection of these cellular targets against high pressures may also have contributed to the increased resistance of acid-adapted cells against inactivation observed during post-processing storage. Overall, these findings prove that the acid adaptive response of E. coli O157:H7 can increase the treatment severity required for pasteurization and that acid adaptation should be considered during HPP process validation. Future studies can be conducted to extend these findings across more strains of E. coli O157:H7, as well as to the other two pertinent pathogens of interest in juice products—Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes. With a clearer understanding of the extent of pressure resistance acid adaptation could potentially confer, the actual processing parameters required for juice processing can be more realistically, and safely, estimated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Temasek Foundation Innovates under its Singapore Millennium Foundation programme (Grant No. R-160-000-B34-592).

The first author also acknowledges the NUS Graduate School, National University of Singapore (NUS) for their financial support. Last but not least, the authors would like to thank Sky Greens Pte Ltd. for their help in this project.

AFTER EPUB

[This article was published on 24 October 2023 with incomplete information for Vinayak Ghate in the “Author Contributions” section. The section was updated in the current version, posted on 29 November 2023.]

Contributor Information

Weibiao Zhou, Email: weibiao@nus.edu.sg.

Edward G. Dudley, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania, USA

REFERENCES

- 1. Besser RE, Lett SM, Weber JT, Doyle MP, Barrett TJ, Wells JG, Griffin PM. 1993. An outbreak of diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from Escherichia coli O157: H7 in fresh-pressed apple cider. JAMA 269:2217–2220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cody SH, Glynn MK, Farrar JA, Cairns KL, Griffin PM, Kobayashi J, Fyfe M, Hoffman R, King AS, Lewis JH, Swaminathan B, Bryant RG, Vugia DJ. 1999. An outbreak of Escherichia coli O157: H7 infection from Unpasteurized commercial apple juice. Ann Intern Med 130:202–209. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-3-199902020-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCarthy M. 1996. E. coli O157:H7 outbreak in USA traced to apple juice. The Lancet 348:1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65758-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . 2007. Guidance for industry: Refrigerated carrot juice and other refrigerated low-acid juices; availability. Fed Regist. Retrieved Oct 10 Oct 2022. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2007/06/05/E7-10792/guidance-for-industry-refrigerated-carrot-juice-and-other-refrigerated-low-acid-juices-availability.

- 5. Huang H-W, Wu S-J, Lu J-K, Shyu Y-T, Wang C-Y. 2017. Current status and future trends of high-pressure processing in food industry. Food Control 72:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.07.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. González-Angulo, M. , Serment-Moreno, V. , Queirós, R. P. , & Tonello-Samson, C. (2021). Food and beverage commercial applications of high pressure processing. In Knoerzer K., & Muthukumarappan K. (Eds.), Innovative Food Processing Technologies (pp. 39–73). [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Souza VR, Popović V, Bissonnette S, Ros I, Mats L, Duizer L, Warriner K, Koutchma T. 2020. Quality changes in cold pressed juices after processing by high hydrostatic pressure, ultraviolet-C light and thermal treatment at commercial regimes. Food Sci Technol 64:102398. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kang J-W, Kang D-H. 2019. The synergistic bactericidal mechanism of simultaneous treatment with a 222-nanometer krypton-chlorine excilamp and a 254-nanometer low-pressure mercury lamp. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e01952-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01952-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazzotta AS. 2001. Thermal inactivation of stationary-phase and acid-adapted Escherichia coli O157: H7, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes in fruit juices. J Food Prot 64:315–320. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-64.3.315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Usaga J, Worobo RW, Padilla-Zakour OI. 2014. Effect of acid adaptation and acid shock on thermal tolerance and survival of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and O111 in apple juice. J Food Prot 77:1656–1663. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buchanan RL, Edelson SG, Snipes K, Boyd G. 1998. Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in apple juice by irradiation. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:4533–4535. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.11.4533-4535.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lim J-S, Ha J-W. 2021. Effect of acid adaptation on the resistance of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium to X-ray irradiation in apple juice. Food Control 120:107489. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang J-W, Kang D-H. 2019. Increased resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli O157: H7 to 222-nanometer krypton-chlorine excilamp treatment by acid adaptation. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e02221–02218. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02221-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patil S, Bourke P, Kelly B, Frías JM, Cullen PJ. 2009. The effects of acid adaptation on Escherichia coli inactivation using power ultrasound. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 10:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2009.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Podolak R, Whitman D, Black DG. 2020. Factors affecting microbial inactivation during high pressure processing in juices and beverages: a review. J Food Prot 83:1561–1575. doi: 10.4315/JFP-20-096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ha J-W, Kang D-H. 2015. Enhanced inactivation of food-borne pathogens in ready-to-eat sliced ham by near-infrared heating combined with UV-C irradiation and mechanism of the synergistic bactericidal action. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:2–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01862-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amoozadeh M, Behbahani M, Mohabatkar H, Keyhanfar M. 2020. Analysis and comparison of alkaline and acid phosphatases of gram-negative bacteria by bioinformatic and colorimetric methods. J Biotechnol 308:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guerrero-beltrán JOSÉÁ, Barbosa-cánovas GV, Welti-chanes J. 2011. High hydrostatic pressure effect on Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli and Listeria innocua in pear nectar. J Food Qual 34:371–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4557.2011.00413.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ramaswamy HS, Zaman SU, Smith JP. 2008. High pressure destruction kinetics of Escherichia coli (O157: H7) and Listeria monocytogenes (Scott A) in a fish slurry. Journal of Food Engineering 87:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.11.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noriega E, Velliou EG, Van Derlinden E, Mertens L, Van Impe JFM. 2014. Role of growth morphology in the formulation of NaCl-based selective media for injury detection of Escherichia coli, Salmonella Typhimurium and Listeria innocua. Food Res Int 64:402–411. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.06.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods . 2010. Parameters for determining inoculated pack/challenge study protocols. J Food Prot 73:140–202. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-73.1.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hsin-Yi C, Chou C-C. 2001. Acid adaptation and temperature effect on the survival of E. coli O157: H7 in acidic fruit juice and lactic fermented milk product. Int J Food Microbiol 70:189–195. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00538-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yuk H-G, Marshall DL. 2004. Adaptation of Escherichia coli O157: H7 to pH alters membrane lipid composition, verotoxin secretion, and resistance to simulated gastric fluid acid. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3500–3505. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3500-3505.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. González-Angulo M, Serment-Moreno V, Clemente-García L, Tonello C, Jaime I, Rovira J. 2021. Assessing the pressure resistance of Escherichia coli O157: H7, Listeria Monocytogenes and salmonella enterica to high pressure processing (HPP) in citric acid model solutions for process validation. Food Res Int 140:110091. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.110091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wouters PC, Glaasker E, Smelt JP. 1998. Effects of high pressure on inactivation kinetics and events related to proton efflux in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:509–514. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.2.509-514.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gabriel AA. 2012. Microbial inactivation in cloudy apple juice by multi-frequency dynashock power ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem 19:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whitney BM, Williams RC, Eifert J, Marcy J. 2007. High-pressure resistance variation of Escherichia coli O157: H7 strains and salmonella serovars in tryptic soy broth, distilled water, and fruit juice. J Food Prot 70:2078–2083. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.9.2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Espina L, García-Gonzalo D, Pagán R. 2016. Detection of thermal sublethal injury in Escherichia coli via the selective medium plating technique: mechanisms and improvements. Front Microbiol 7:1376. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bozoglu F, Alpas H, Kaletunç G. 2004. Injury recovery of foodborne pathogens in high hydrostatic pressure treated milk during storage. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 40:243–247. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(04)00002-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim M-J, Yuk H-G, Schottel JL. 2017. Antibacterial mechanism of 405-nanometer light-emitting diode against salmonella at refrigeration temperature. Edited by Yuk H. G.. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e02582–02516. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02582-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brown JL, Ross T, McMeekin TA, Nichols PD. 1997. Acid habituation of Escherichia coli and the potential role of Cyclopropane fatty acids in low pH tolerance. Int J Food Microbiol 37:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00068-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charoenwong D, Andrews S, Mackey B. 2011. Role of rpoS in the development of cell envelope resilience and pressure resistance in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:5220–5229. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00648-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen YY, Gänzle MG. 2016. Influence of cyclopropane fatty acids on heat, high pressure, acid and oxidative resistance in Escherichia coli. Int J Food Microbiol 222:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dubins DN, Lee A, Macgregor RB, Chalikian TV. 2001. On the stability of double stranded nucleic acids. J Am Chem Soc 123:9254–9259. doi: 10.1021/ja004309u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Huang H-W, Lung H-M, Yang BB, Wang C-Y. 2014. Responses of microorganisms to high hydrostatic pressure processing. Food Control 40:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mañas P, Mackey BM. 2004. Morphological and physiological changes induced by high hydrostatic pressure in exponential-and stationary-phase cells of Escherichia coli: relationship with cell death. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:1545–1554. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1545-1554.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tucker DL, Tucker N, Conway T. 2002. Gene expression profiling of the pH response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 184:6551–6558. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6551-6558.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Calhoun LN, Kwon YM. 2011. Structure, function and regulation of the DNA‐binding protein Dps and its role in acid and oxidative stress resistance in Escherichia coli: a review. J Appl Microbiol 110:375–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04890.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Malone AS, Chung Y-K, Yousef AE. 2006. Genes of Escherichia coli O157:H7 that are involved in high-pressure resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:2661–2671. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2661-2671.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wanner BL. 1996. Phosphorus assimilation and control of the phosphate Regulon. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology 1:1357–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gayán E, Govers SK, Aertsen A. 2017. Impact of high hydrostatic pressure on bacterial proteostasis. Biophys Chem 231:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malki A, Le H-T, Milles S, Kern R, Caldas T, Abdallah J, Richarme G. 2008. Solubilization of protein aggregates by the acid stress chaperones HdeA and HdeB. J Biol Chem 283:13679–13687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800869200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Duru IC, Bucur FI, Andreevskaya M, Nikparvar B, Ylinen A, Grigore-Gurgu L, Rode TM, Crauwels P, Laine P, Paulin L, Løvdal T, Riedel CU, Bar N, Borda D, Nicolau AI, Auvinen P. 2021. High-pressure processing-induced transcriptome response during recovery of Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Genomics 22:117. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07407-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li Z, Jiang B, Zhang X, Yang Y, Hardwidge PR, Ren W, Zhu G. 2020. The role of bacterial cell envelope structures in acid stress resistance in E. coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:2911–2921. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10453-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]