Abstract

Background

Impaired social functioning is a major, but under-elucidated area of schizophrenia. It’s typically understood as consequential to, eg, negative symptoms, but meta-analyses on the subject have not examined psychopathology in a broader perspective and there’s severe heterogeneity in outcome measures. To enhance functional recovery from schizophrenia, a more comprehensive understanding of the nature of social functioning in schizophrenia is needed.

Study Design

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched PubMed, PsycInfo, and Ovid Embase for studies providing an association between psychopathology and social functioning. Meta-analyses of the regression and correlation coefficients were performed to explore associations between social functioning and psychopathology, as well as associations between their subdomains.

Study Results

Thirty-six studies with a total of 4742 patients were included. Overall social functioning was associated with overall psychopathology (95% CI [−0.63; −0.37]), positive symptoms (95% CI [−0.39; −0.25]), negative symptoms (95% CI [−0.61; -0.42]), disorganized symptoms (95% CI [−0.54; −0.14]), depressive symptoms (95% CI [−0.33; −0.11]), and general psychopathology (95% CI [−0.60; −0.43]). There was significant heterogeneity in the results, with I2 ranging from 52% to 92%.

Conclusions

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to comprehensively examine associations between psychopathology and social functioning. The finding that all psychopathological subdomains seem to correlate with social functioning challenges the view that impaired social functioning in schizophrenia is mainly a result of negative symptoms. In line with classical psychopathological literature on schizophrenia, it may be more appropriate to consider impaired social functioning as a manifestation of the disorder itself.

Keywords: Functional outcome, symptomatology, recovery, autism

Introduction

Social functioning is an object of intense research in several branches of psychiatry. Despite massive research efforts, little is known about the nature of impaired social functioning in schizophrenia. Over the last decades, we have witnessed a growing interest in recovery and remission from schizophrenia. There is consensus that recovery requires both clinical and social remission, where the latter usually refers to reassuming social roles, a normal family life, full employment, independent living, etc.1,2 Today, there are 2 predominant accounts, attempting to explain impaired social functioning in schizophrenia, and on both accounts, impaired social functioning is considered consequential to other factors. On one account, social difficulties are caused by neuro- or social cognitive deficits,3–5 and, on the other account, these difficulties are linked to or caused by negative symptoms.6–11 Regarding the first account, a meta-analysis from 2019 found associations between neuro- or social cognition and social functioning with small-to-medium effects sizes.12 Yet, a significant proportion of the variance in the relationship between neurocognition and social functioning remained unexplained, indicating that other factors also contribute considerably to impaired social functioning in schizophrenia. Regarding the latter account, less is known. A meta-analysis from 2009 examined associations between social functioning and only two domains of psychopathology, ie, positive and negative symptoms, and it found a significant correlation between negative symptoms and social functioning.13 Other studies have explored associations between psychopathology and social functioning, but these studies have been limited by only including few and very specific aspects of social functioning.11,14 Jointly, the available data suggest that both cognitive deficits and negative symptoms are associated with impaired social functioning. This conclusion is readily reproduced in authoritative textbooks with statements like “negative symptoms are the most important clinical symptoms in schizophrenia because the severity of negative symptoms predicts short-term and long-term disability better than the severity of psychotic or disorganization symptoms.”15, p. 3265 Yet, this conclusion is not unproblematic. One problem is that meta-analyses have so far only examined a few psychopathological domains.7,11,14 Another problem is, as stated in a recent systematic review, that there is severe heterogeneity in functional outcome measures in schizophrenia research, and that future research must disentangle this issue.16

Impaired social functioning is one of the main challenges in schizophrenia both for the individual and for society. If we are to improve social remission and enhance recovery, we must obtain more comprehensive knowledge of the nature of social functioning and its impairment in schizophrenia. However, no systematic review or meta-analysis has yet comprehensively explored the association between a wide array of psychopathology and social functioning in schizophrenia.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to comprehensively examine the association between psychopathology and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.17

PubMed, PsycInfo, and Ovid Embase were searched using the following combined search strings (in title/abstract): (1) Schizophrenia OR “schizotypal disorder” OR “schizotypal personality disorder” OR schizoaffective, (2) “psychopatholog*,” and 3) “functional outcome” OR “social functioning” OR “social dysfunction” OR “real world function*” OR “homelessness.” The search was conducted July 4, 2022, with no time limit imposed (see supplementary 1. In addition, reference lists of other reviews and meta-analyses were hand-searched.

RH checked for doublets and screened titles and abstracts to exclude studies not peer-reviewed, not reported in English, animal studies, and non-empirical studies. Studies not reporting clinical measures of psychopathology were also excluded. RH and IM independently screened each of the remaining studies, excluding studies not fulfilling the following inclusion criteria: Studies must include more than 20 participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizotypal disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, or schizoaffective disorder (jointly: “schizophrenia spectrum disorders”); studies must report an association between clinician-rated psychopathology and clinician-rated social functioning in the form of a correlation or regression coefficient. Longitudinal studies, not reporting a cross-sectional association between psychopathology and social functioning, were excluded. For longitudinal studies with correlation or regression coefficients for both baseline and follow-up, the baseline coefficient was preferred. Studies that only reported a regression coefficient and not values for nonsignificant psychopathological or social functioning factors in their regression model were also excluded. Disagreements were solved by discussion between RH, IM, MGH, and JN. Data were extracted by RH and CH.

Data Analysis

The main outcome was the association between the different domains of psychopathology and social functioning. Secondary outcomes were the association between the subdomains of social functioning and subdomains of psychopathology, as well as an overview of the methods used to measure social functioning and psychopathology. For social functioning, we divided the outcome into 2 levels: (1) Overall score of social functioning (if such a score was provided in the studies), and (2) findings were grouped into the three following subdomains of social functioning, inspired by the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP)18: “Socially useful activities” (including work, studies, and hobbies), “Personal and social relationships” (friends or family), and “Self-care” (eg, living situation, hygiene, economic autonomy, and adherence to treatment). We chose not to include the fourth domain of the PSP (ie, ‘disturbing and aggressive behaviors´), since most scales measuring social function do not include such a domain. Scales other than PSP were classified as 1 of the 3 subdomains described above, depending on their best fit. When such a classification was not possible, the scales were classified as “other,” and they were not used in the meta-analysis. For psychopathology, we also divided the outcome into 2 levels: (1) overall score of psychopathology (if such a score was provided in the studies), and (2) findings were divided into the following 5 subdomains of psychopathology: Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, general symptoms, disorganized symptoms, and depressive symptoms. The subdomains of psychopathology were chosen based on the classification in the original studies.

Risk of bias in cohort studies was assessed with The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses,19 and cross-sectional studies with the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.20

We performed a series of meta-analyses, using random-effects models, to explore associations between (1) overall social functioning and overall psychopathology, (2) overall social functioning and subdomains of psychopathology, and (3) social functioning subdomains and psychopathological subdomains. We did not do meta-analyses for subdomains examined by less than 4 studies.

The correlation and regression coefficients between social functioning and psychopathology were used as effect sizes. All coefficients were converted using Fisher’s z transformation.21 For the 2 studies that presented data from different samples or subgroups, a mean weighted by number of patients was calculated.22,23

Random-effect models were used as we assumed a high degree of heterogeneity between studies. Heterogeneity was described as I2, which is a recommended transformation of the calculated Q. The value of 25% describes low, 50% moderate, and 75% high heterogeneity.24 We used inverse-variance weighting, and Knapp–Hartung adjustment.25

Test of publication bias was completed for each of the main analyses, when the number of studies included exceeded 10, following the recommendation by Sterne et al.26 Publication bias was assessed using a consensus approach, consisting of the visual examination of funnel plots, Egger’s regression test,27 and the trim and fill method.

We performed an influence analysis for each of the main analyses by running each analysis multiple times, each time excluding one of the studies. This allowed us to assess whether the results were robust against excluding particular studies.28

Potential sources of heterogeneity across studies for each correlation were explored when at least 10 studies reported data of the same variable, using either subgroup meta-analysis or random-effects meta-regression analyses. Subgroup analyses were performed on the following variables; study type (regression, correlation), diagnostic group (narrow inclusion: Only schizophrenia or wide inclusion: Schizophrenia spectrum disorders), and illness phase. Since illness phase is rarely reported, we used in-patient/out-patient status as a proxy for illness phase. For analyses on correlations with positive and negative symptoms, we included subgroup analyses of social function measurement (PSP yes/no, Quality of Life Scale [QLS] yes/no).

Subgroup analyses were performed on all analyses with at least 4 studies in each subgroup. This is recommended for subgroups to be adequately powered to obtain clinically meaningful results.29 The pooled associations were compared between each subgroup and compared to the total effect size. We did separate meta-regression analyses for the following covariates: Age (participants mean age) and gender (male/female ratio).

All statistical analysis was performed using R 4.2.130 and the metafor package.31

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Study Selection

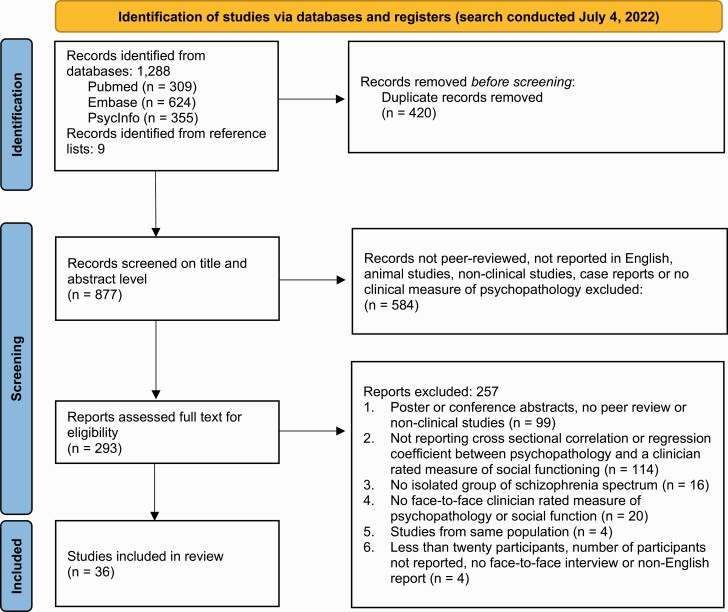

We identified 1288 records and included 36 articles with a total of 4742 participants, with a mean age of 38.4 years (mean ranges from 20.6 to 48.9) and 66.8% men and 33.2% women (see figure 1 for a PRISMA flow diagram with breakdown of the study selection and supplementary material 3 for demographics, diagnosis, and in-patient/out-patient status of patients in included studies, and supplementary 9 for studies excluded at full text screening).22,23,32–65 The included articles are shown in table 1.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Table 1.

Overview of the Included Articles

| Author | Year | Study Design | Number of Participants |

Quality Rating | Aims With Relevance for This Study | Measures of Psychopathology | Measures of Social Function | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meltzer et al.32 |

1990 | cohort | 38 | fair | Effect of clozapine treatment on the QOL of treatment-resistant patients with SCZ. | BPRS | QLS | Sig. correlations: Both total BPRS and negative symptoms with total QLS and both the interpersonal and instrumental subscale. Positive symptoms with total QLS and instrumental subscale. |

| 2 | Breier et al.33 | 1991 | cohort | 58 | fair | Interrelationship between functional and symptom measures at follow up in young, chronic patients with SCZ. | SANS, BPRS | LFS | Sig. correlations: SANS and the positive domain of BPRS with the subdomains of LFS |

| 3 | Bow- Thomas et al.34 |

1999 | cohort | 45 | fair | Relationships between QOL and symptomatology across different phases of SCZ. | BPRS, NSA | QLS | Sig. correlations: Paranoia factor of BPRS with QLS. Both total NSA and the motivational factor correlated with QLS. |

| 4 | Browne et al.35 |

2000 | cross-sectional | 53 | fair | Clinical correlates of QOL at the time of first presentation with SCZ. | PANSS | QLS | Sig. correlations: PANSS N, G and T with QLS. |

| 5 | Norman et al.36 |

2000 | cross-sectional | 128 | fair | Symptoms, level of community functioning and living circumstances as correlates of QLS scores. | SAPS, SANS | QLS | Sig. correlations: QLS with both SANS and SAPS total, and the subdomains of reality distortion, disorganization, and psychomotor poverty. |

| 6 | Hansson et al.38 |

2001 | cross-sectional | 104 | good | The relationship between personality factors and subjectively appraised and interviewer rated QOL, controlling for social and clinical factors. | BPRS | LQOLP | Predictive value: Total BPRS contributed to the prediction of interviewer rated QOL. |

| 7 | Huppert et al.39 |

2001 | cohort | 63 | fair | The relationship between multiple symptom domains and QOL in a cohort of recently stabilized outpatients. | SANS, SAPS, BPRS |

QOLI | Sig. correlations: Depression domain on BPRS and formal thought disorder on SAPS with social relations. Anhedonia/asociality domain on SANS with daily activities. Predictive value: Depression contributed to the prediction of social contacts. |

| 8 | Goldberg et al.37 |

2001 | cross-sectional | 23 | fair | Relationship between social function and negative symptoms. | PANSS | QLS | Sig. correlations: PANSS P with instrumental role. PANSS N with interpersonal relations. |

| 9 | Rocca et al.41 |

2005 | cross-sectional | 78 | good | Relationship between depressive symptoms and functional outcome. | PANSS, CDSS | QLS, SDS, SOFAS |

Sig. correlations: CDSS correlated with DISS and QLS. Predictive value: QLS and DISS contributed to CDSS score. |

| 10 | Ritsner et al.40 | 2005 | cohort | 133 | fair | To identify a core subset of QLS21 items that maintains the validity and psychometric properties of the complete version. | PANSS | QLS | Sig. correlation: PANSS T, P, N, activation, dysphoric mood, and autistic preoccupation subdomains with QLS. |

| 11 | Hofer et al.43 | 2006 | cross-sectional | 60 | good | Relationship between psychopathology, QOL and psychosocial functioning. | PANSS | No scale | Sig. correlations: PANSS T with competitive employment, partnership, and independent living. PANSS cognitive with competitive employment. PANSS N with partnership and independent living. |

| 12 | Bozikas et al.42 |

2006 | cross-sectional | 40 | fair | The effect of psychopathology and other variables on community outcome. | PANSS | QLS | Sig. correlations: PANSS N with interpersonal relationships, instrumental role function and total QLS. PANSS cognitive with interpersonal relationships and total QLS. |

| 13 | Juckel et al.44 | 2008 | cohort | 62 | fair | Validation of the PSP. | PANSS | PSP | Sig. correlations: PANSS N, P, and G with total PSP. |

| 14 | Grant et al.45 | 2009 | cross-sectional | 55 | fair | To test the hypothesis that defeatist beliefs regarding performance provides a link between cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and poor functioning in schizophrenia. |

SANS, SAPS, BDI- II |

QLS | Sig. correlation: SANS total score and both of the subscales psychotic and disorganized on SAPS with QLS. |

| 15 | Simonsen et al.22 |

2010 | cross-sectional | 114 | poor | Relationship between psychosocial function, neurocognition, and psychopathology. | PANSS, YMRS, IDS-C |

GAF-F | Sig. correlations: IDS-C, YMRS, PANSS P, and N with GAF-F. |

| 16 | Schaub et al.46 |

2011 | cross-sectional | 103 | good | Examining outcome of psychopathology and social functioning. | PANSS | PSP | Sig. correlations: PANSS P, Di, and excitement with all subdomains on PSP. PANSS N with activities and self-care. |

| 17 | Smith et al.47 |

2012 | cross-sectional | 46 | fair | Relation between empathy deficit and functional outcome. | SAPS, SANS | SLOF | Sig. correlations: SLOF with disorganized symptoms. |

| 18 | Caqueo- Urizar et al.48 |

2013 | cross-sectional | 45 | fair | Relation between symptomatology and QOL. | PANSS | SFS | Sig. correlation: Independence-competence with PANSS P, N and G; Interpersonal behavior and Independence-performance with PANSS N and G; and recreation and employment/occupation with PANSS N. |

| 19 | Hueng et al.49 |

2013 | cross-sectional | 60 | fair | Relationship between clinical symptoms, social cognition, and social functioning. | PANSS | PSP | Sig. correlations: PANSS N and G with PSP, including all subdomains. |

| 20 | Kundu et al.50 |

2013 | cross-sectional | 80 | fair | Relationship between positive symptoms and current social functioning. | SAPS | SCARF- SFI |

Sig. correlations: Hallucinations with occupational role; delusion with family role; bizarre behavior with both family role and other social role. |

| 21 | Reiningha us et al.23 |

2013 | cross-sectional | 816 | fair | Relationship between depressive symptoms and functional outcome in an early psychosis sample and an Enduring psychosis sample. | PANSS | SFS, GSDS |

Early psychosis sample

Sig. correlations: Early psychosis sample: PANSS G and N with social functioning. Enduring psychosis sample: Sig. correlations: PANSS N, G, Di, and mania with social functioning. |

| 22 | Menendez -Miranda et al.52 |

2015 | cross-sectional | 139 | fair | To identify factors predicting both functional capacity and real-world functioning in outpatients with stable SCZ. | PANSS, CGI | PSP | Sig. correlations: All domains of PANSS and CGI with PSP. Predictive value: PANSS N and CGI predicted PSP total; Self-care was predicted by PANSS N and P; Useful activities and relationships was predicted by PANSS N and CGI. |

| 23 | Ladea et al.51 |

2015 | cross-sectional | 32 | fair | To evaluate the applicability of the ASSESS battery. | PANSS | PSP | Sig. correlations: PSP with PANSS T, P, and N. |

| 24 | Santosh et al.53 |

2015 | cross-sectional | 100 | fair | Relationship between psychopathology, cognitive selfregulation, and social functioning in schizophrenia. | PANSS | SCARF- SFI |

Sig. correlations: PANSS T, P, and N with all subdomains of SCARF-SFI. |

| 25 | Tonna et al.54 |

2016 | cross-sectional | 60 | fair | Relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptoms and functioning. | PANSS, YBOCS | SOFAS | Sig. correlations: PANSS P, N, G, and Di with SOFAS. |

| 26 | Bechi et al.55 | 2017 | cross-sectional | 79 | fair | Relationship between clinical, neurocognitive, and social cognitive domains. | PANSS | QLS | Sig. correlations: PANSS T with QLS. |

| 27 | Lee et al.56 | 2017 | cross-sectional | 28 | fair | To examine if the social and role function impairment was found in patients with FE-SCZ and to explore its relations with psychopathology. | SANS, SAPS, MADRS |

GF | Sig. correlations: Total SANS and the subdomain of avolition-apathy with GF Social and Role; MADRS with GF Role. |

| 28 | Phalen et al.57 | 2017 | cross-sectional | 88 | good | To examine if ToM moderated the impact of the relationships between ratings of suspiciousness and global social functioning. | PANSS | SFS | Predictive value: Both suspiciousness/persecution item on PANSS, and PANSS T without suspiciousness/persecution item, predicted SFS score. |

| 29 | Zizolfi et al.59 | 2019 | cross-sectional | 44 | fair | To identify the potential capacity of resilience, recovery style, psychotic symptoms and neurocognition to influence psychosocial functioning and QOL of people with psychosis. | PANSS | LSP | Sig. correlations: PANSS P and G, with LSP. Predictive value: Only PANSS G contributed to prediction of LSP. |

| 30 | GonzalezBlanco et al.58 |

2019 | cohort | 73 | fair | To explore determining factors of real-world functioning, including both clinical and biological factors. | PANSS, CDSS, BNSS |

PSP | Sig. correlations: CDSS, the BNSS subdomains of anhedonia, asociality, avolition, blunted affect, and alogia as well as PANSS P and G with PSP total and all subdomains of PSP; the BNSS subdomain of distress with the PSP subdomain of distress. Predictive value: PANSS G and the BNSS subdomains of asociality, avolition, and blunted affect contributed to prediction of PSP total; PANSS G, asociality, and blunted affect contributed to prediction of personal |

| relationships; PANSS G and avolition to self-care. | |||||||||

| 31 | Porcelli et al.60 | 2020 | cross-sectional | 765 | fair | Relationship between psychopathological characteristics associated with social dysfunction in SCZ patients. | PANSS | QLS | Sig. correlations: PANSS total with interpersonal relations on QLS. |

| 32 | Charernbo on et al.61 |

2021 | cross-sectional | 64 | fair | Relationship between positive and negative symptoms, neuro- and social cognition and real-life functioning in SCZ. | SAPS, SANS | PSP | Sig. correlations: Partial correlation matrix showed that alogia and anhedonia correlated with PSP score while the total SAPS score and the SANS subdomains of blunted affect, avolition and asociality, was inversely correlated with total PSP. |

| 33 | Garcia- Portilla et al.62 |

2021 | cross-sectional | 144 | fair | Relationship between the real-world functioning of patients with SCZ on maintenance antipsychotic monotherapy. | PANSS, CDSS, BSS |

PSP | Sig. correlations: All subdomains of PANSS, BNSS, and CDSS with PSP score. Predictive value: BNSS subdomains of abulia, asociality and blunted affect, and PANSS G contributed to prediction of PSP total score. |

| 34 | Lucarini et al.63 |

2021 | cross-sectional | 35 | fair | Relationship between the conversational patterns of dialogs in SCZ patients, and symptom dimensions and social functioning. | PANSS | SOFAS | Predictive value: PANSS P and N contributed prediction of SOFAS score. |

| 35 | Mucci et al.64 |

2021 | cohort | 921 | good | Relationship between illness related variables, personal resources, context-related factors and work skills, interpersonal relationships, everyday life skills. | PANSS, BNSS | SLOF | Predictive value: BNSS subdomain avolition predicted interpersonal relationships and PANSS P predicted work skills. |

| 36 | Hu et al.65 | 2022 | cross-sectional | 269 | fair | Relationship between motivation and pleasure and expressivity deficits, social functioning and other psychopathology. | PANSS, CAINS | SOFAS | Predictive value: Motivation and pleasure factor of CAINS and PANSS P contributed to prediction of SOFAS score. |

table 1 - BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory II; BNSS, Brief Negative Symptom Scale; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; CAINS, The Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative

Symptoms; CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; IDS-C, Inventory of Depressive Symptoms; MADRS, Montgomery & Åsberg

Depression Rating Scale; NSA, Negative Symptom Assessment; PANSS, Positive And Negative Symptom Scale; SANS, Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms; SAPS, Scale for

The Assessment of Positive Symptoms; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive And Negative Symptom Scale; PANSS P,

PANSS Positive; PANSS N, PANSS Negative; PANSS G, PANSS General Psychopathology; PANSS Di, PANSS Disorganization; PANSS De, PANSS Depressive; PANSS T, PANSS Total; GAF-F, Global Assessment of Functioning; GF, Global functioning; GSDS, Groningen social disability scale; LFS, Level of Functioning Scale; LQOLP, Lancashire quality of life profile; LSP, Life skills profile; PSP, Personal and Social Performance Scale; QLS, Quality of life Scale; QOLI, Quality of Life Interview; SCARF-SFI, Social Functioning Index of Schizophrenia Research Foundation; SDS, Sheehan disability scale; SFS, Social functioning scale; SLOF, Specific Level of Functioning; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; QOL, Quality of life; SCZ, Schizophrenia; FE, First Episode; ToM, Theory of Mind.

Association Between Overall Social Functioning and Overall Psychopathology

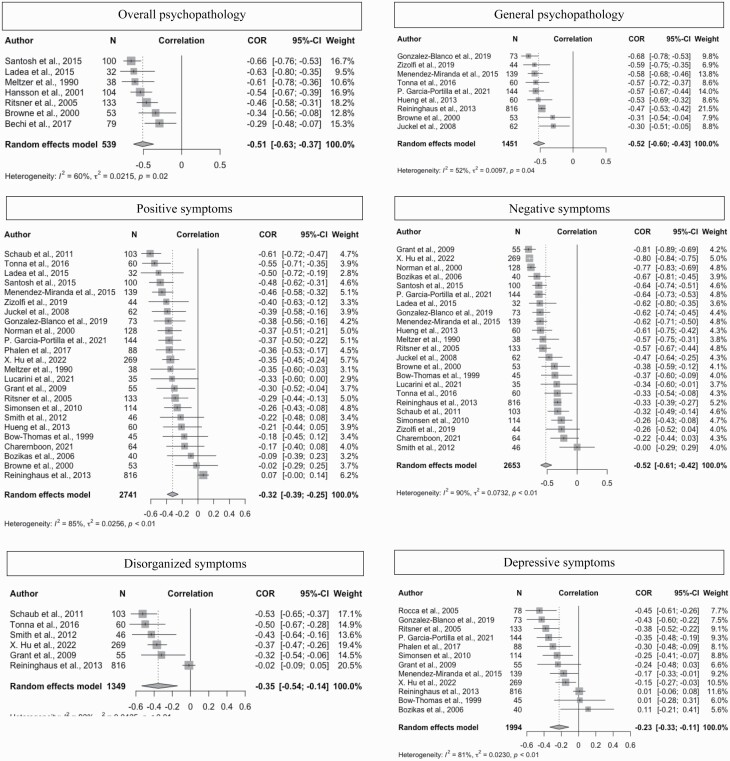

Results from the meta-analysis and forest plot for the association between overall social functioning and overall psychopathology are shown in figure 2. Only seven studies reported an overall score for psychopathology, eg, a total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).66 For the 539 participants included in these 7 studies, we found a correlation of −0.51 (95% CI [−0.63; −0.37]).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for overall social functioning and the different domains of psychopathology.

Association Between Overall Social Functioning and Subdomains of Psychopathology

Twenty-five studies with a total of 2845 patients examined the correlation between overall social functioning and subdomains of psychopathology. Figure 2 shows the results for overall social functioning and the following psychopathological subdomains: Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, general symptoms, disorganized symptoms, and depressive symptoms. All 5 psychopathological subdomains were significantly (P < .01) and negatively correlated with overall social functioning. The strongest association was with general symptoms (r = −0.52, 95% CI [−0.6; −0.43]) and negative symptoms (r = −0.52, 95% CI [−0.61; −0.42]), followed by disorganized symptoms (r = −0.35, 95% CI [−0.54; −0.14]) and positive symptoms (r = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.39; −0.25]). The weakest association was with depressive symptoms (r = −0.23, 95% CI [−0.33; −0.11]).

Association Between Subdomains of Social Functioning and Subdomains of Psychopathology

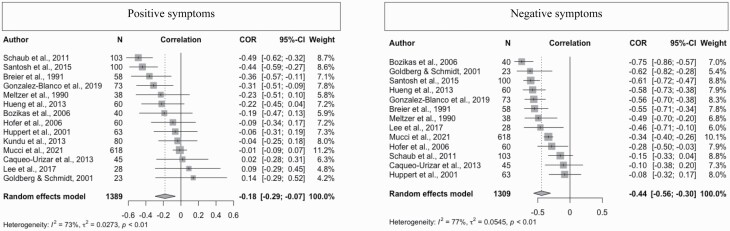

Fifteen studies with a total of 2104 patients examined the correlation between subdomains of social functioning and subdomains of psychopathology. Figure 3 shows forest plots for the social functioning subdomain “Personal and social relationships” and the psychopathological subdomains of positive and negative symptoms. Four studies were included in the analysis of “Personal and social relationships” and overall psychopathology, and five studies were included in the analysis of “Personal and social relationships” and depressive symptoms (see supplementary material 2. We found associations between “Personal and social relationships” and overall psychopathology (P = 0.02), and between “Personal and social relationships” and positive and negative symptoms (both P < 0.01), respectively. There was no association between “Personal and social relationships” and depressive symptoms. The strongest associations were found between “Personal and social relationships” and “overall psychopathology” (r = −0.46) and negative symptoms (r = −0.44), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for “Personal and social relationships” and positive and negative symptoms.

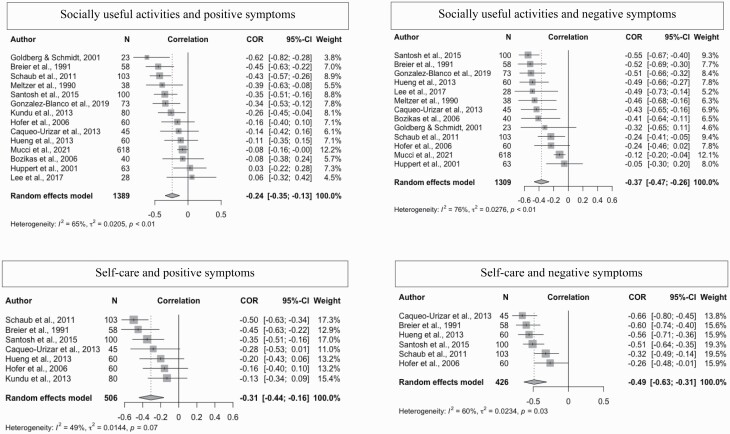

Figure 4 shows forest plots for both “Socially useful activities” and “Self-care,” both in relation to positive and negative symptoms. The strongest association were found between “Socially useful activities” and negative symptoms (r = −0.37, P < .0001). We found a correlation between “Socially useful activities” and positive symptoms (p<0.01), but not between “Socially useful activities” and depressive symptoms. Less than four studies examined the association between “Socially useful activities” and overall psychopathology, general and disorganized symptoms, respectively, and therefore we did not explore this, as explained in the methods section. Finally, for “Self-care,” only associations with positive and negative symptoms were tested (both P < 0.01) as fewer than four studies had examined the other subdomains. For more forest plots and further details, see supplementary material 2.

Fig. 4.

Forest plots for “Socially useful activities” and “Self-care” and positive and negative symptoms.

Subgroup Analysis

We performed subgroup analyses (see supplementary material 5) for overall social functioning and positive, negative, general, and depressive symptoms, respectively. It also included both “Socially useful activities” and “Personal and social relationships” combined with positive and negative symptoms, respectively. The following variables were examined as possible mediators: Study type, diagnosis, illness phase, and social function measurement scale for the subgroups. We found no moderating effect of illness phase or social function measurement scale in any of the analyses.

Only 2 variables showed moderating effects, each in just one subgroup. The variable “study type” had a moderating effect in the subgroup “correlation between overall social functioning and negative symptoms” (correlation difference = 0.19, P = .03), meaning that studies using a correlation coefficient reported a significantly higher association between overall social functioning and negative symptoms compared to studies using a regression coefficient. The variable “diagnosis” showed a moderating effect in the subgroup analysis “Personal and social relationships” and negative symptoms’ (only schizophrenia vs. schizophrenia spectrum disorders) (P = .02), meaning that this correlation was significantly higher for studies only including patients with schizophrenia than for studies with wider inclusion. Since there were <4 studies in the remaining subgroups, we did not perform analyses on these (see supplementary material 5 for details).29

Univariate Meta-Regression Analyses

We performed meta-regression analyses on correlations with more than 10 studies (see supplementary material 6). We included the covariates “age” and “gender,” and we found no significant moderating effect for any of the included correlations.

Risk of Publication Bias

Funnel plots of the correlations between overall social functioning and positive, negative, and depressive symptoms (24, 23, and 12 studies, respectively) were separately visually examined for asymmetry, indicating risk of publication bias. We did not perform funnel plots for the meta-analysis with less than 10 studies as recommended.26 The funnel plot for overall social functioning and positive symptoms showed asymmetry, which prompted further analyses, using Egger’s regression test, and the trim and fill method. This showed indication of funnel plot asymmetry (overall social functioning and positive symptoms: Bias = −4.48, t = −3.82, P-value < .01). Thus, based on the combination of funnel plot asymmetry and Egger’s regression test, publication bias may have influenced the association between social function and positive symptoms.

The funnel plot for overall social functioning and negative symptoms and depressive symptoms, respectively, showed asymmetry, and we performed Egger’s regression test and the trim and fill method. This did not indicate funnel plot asymmetry. See supplementary material 6 for details.

The influence analysis revealed no noticeable effect on the pooled correlations for the correlation between overall social functioning and psychopathological subdomains (see supplementary material 7).

Heterogeneity in Results and Methods of Included Studies

There was considerable heterogeneity both concerning the results (with I2 ranging from 52% to 92%) and the methods across the included studies. In the 36 studies, 13 different psychopathological scales were used. The most common scale was the PANSS, which was used in 25 of the studies, but in 11 different versions. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) were each used in seven studies,67,68 The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in 5,69 The Brief Negative Symptom Scale and The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia each in 3,70,71 and the rest of the scales were used in one study each.

Fifteen different scales were used to assess social functioning. The following were used in at least 3 studies: QLS,72 used in 11 studies, assesses four domains: Interpersonal relations, instrumental role, intrapsychic foundations, and common objects and activities. The Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP),18 used in 8 studies, assesses four domains: Socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care, and disturbing and aggressive behavior. The Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale,18 used in 4 studies, assesses overall level of functioning, focusing on social, occupational, and school functioning. Finally, the Social Functioning Scale,73 used in 3 studies, measures social engagement/withdrawal, interpersonal behavior, pro-social activities, recreation, independence-competence, independence performance, and employment–occupation. In the remaining 11 studies: 2 studies used the Scarf Social Functioning Index (SCARF-SFI),74), 2 used the Specific Level of Functioning Scale (SLOF),74,75 6 studies used a scale that was only used in that particular study, and 1 study did not use a standardized scale.43

The risk of bias assessment showed that 6 studies had good quality, 29 had fair quality, and 1 had poor quality (table 1).

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis that has explored associations between social functioning and psychopathology in schizophrenia. The main finding was that all examined psychopathological domains correlated significantly and moderately with impaired social functioning in schizophrenia, both on an overall level, and when divided into subdomains. Sub-group analyses and meta-regression did not change the overall picture. The associations were strongest for social functioning and general symptoms, negative symptoms, and overall psychopathology, respectively. However, the results should be interpreted cautiously in light of the heterogeneity across studies.

Our finding of associations between impaired social functioning and all classical psychopathological symptom domains of schizophrenia paints a somewhat different and more nuanced picture of the association between social functioning and psychopathology than that provided by studies both on impaired neuro- and social cognition, and on negative symptoms. One meta-analysis found that the association between neurocognition and social functioning was partially mediated by negative symptoms, but also that positive symptoms were neither associated with neurocognition nor functional outcome.13,76 In other studies, negative symptoms were to some extent found to influence the association between social cognition and social functioning.77 Other studies have pointed to impaired social functioning being correlated with or even caused by negative symptoms.6,8–11 The results from these previous studies are to some extent at odds with the main results from our meta-analysis, which found significant correlations between impaired social functioning and all domains of psychopathology. Consequently, this finding doesn’t seem to support the idea that impaired social functioning is simply a consequence of negative symptoms.6,7,9,11

Overlapping Measures

We found the strongest correlations between overall social functioning and psychopathological subdomains for negative and general symptoms. However, the correlations for these subdomains may be inflated due to a partial overlap between, on the one hand, what is being measured as general and negative symptoms, and, on the other hand, what is being measured as social functioning. For example, in the most used scale to assess psychopathology, ie, the PANSS, items G8 “Uncooperativeness” or G16 “Active social avoidance” on the general symptom scale or items N2 “Emotional withdrawal” or N4 “Passive/apathetic social withdrawal” on the negative symptom scale clearly measures aspects of impaired social functioning. Similarly, certain items on measures of social functioning also seem to overlap negative symptoms—eg, items 14 “degree of motivation” and 20 “capacity for empathy” on the QLS overlaps with what is being measured with item N2 “poor contact” on the negative symptoms scale of the PANSS. Thus, caution is warranted when interpreting the correlations between impaired social functioning and negative and general symptoms, respectively.

Few Studies on Some Aspects of Social Functioning

Looking more closely at the associations between psychopathology (both overall and subdomains) and the subdomains of social functioning, we generally found that all subdomains of social functioning were correlated to psychopathology. Yet, not all subdomains of psychopathology correlated with all subdomains of social functioning. For example, depressive symptoms did not correlate with “Personal and social relationships” or “Socially useful activities.” Importantly, however, the few cases in which we did not find correlations between subdomains of social functioning and subdomains of psychopathology were also the cases that had been explored by only a few studies. Thus, this lack of correlations between subdomains of social functioning and, e.g., depressive symptoms, may potentially be explained by lack of power in the statistical analysis.

Rethinking the Nature of Impaired Social Functioning in Schizophrenia

Our finding that psychopathology broadly and not just negative symptoms is significantly correlated to impaired social functioning in schizophrenia seems to challenge the two predominant accounts of impaired social functioning in schizophrenia, claiming that such impairment is caused either by deficits in neuro- or social cognition or by negative symptoms. By contrast, we found that all psychopathological domains correlate significantly with impaired social functioning. This finding raises an important theoretical issue: Perhaps impaired social functioning in schizophrenia is not optimally conceived as a consequence of something else (eg, deficits in neuro- or social cognition or negative symptoms) but rather as a direct manifestation of the disorder itself. More specifically, we propose that impaired social functioning in schizophrenia may be arising from the same core disturbance that generates its psychopathology. Such a reconsideration of the nature of impaired social functioning in schizophrenia could potentially explain both its close association with all psychopathological domains and its links to some domains of deficits in neuro- or social cognition, which, unlike psychopathology, are not defining features of the disorder in the diagnostic manuals. In our view, impaired social functioning may for some patients with schizophrenia be the predominant manifestation of the disorder (eg, homeless patients with schizophrenia or young people with schizophrenia who severely underperform,78–80 just like it for other patients may be delusions, hallucinations, or patterns of disorganization that are the predominant feature). If this attempt to rethink the nature of impaired social functioning in schizophrenia is correct, we should expect that the quality of impaired social functioning in schizophrenia, at least to some degree, is different from that of impaired social functioning in other mental disorders, eg, bipolar disorder, personality disorder, and autism spectrum disorder. Clarifying such potential differences in the quality of impaired social functioning across disorders could prove valuable for both differential diagnosis and treatment.

Perspective to the Foundational Texts on Schizophrenia

To some extent, this attempt to rethink the nature of impaired social functioning in schizophrenia is not new. In fact, it is consistent with foundational texts on schizophrenia and especially the classical descriptions of schizophrenic autism. For example, Bleuler regarded autism, which he defined as withdrawal from the social world accompanied by preoccupation with phantasy life, as a fundamental, trait-like feature of schizophrenia.81 Minkowski reconceived autism as a “loss of the vital contact with reality” and considered it the very pathogenetic core (“trouble générateur”) of schizophrenia.82 Unlike Bleuler, Minkowski did not regard autism as a withdrawal from the social world but rather as a failing immediate and harmonious attunement to others and the world, which often may lead to behaviors, expressions, or ideas that appear contextually inappropriate.83 Similarly, Blankenburg considered autism as the very core of schizophrenia, describing it as “loss of common sense,” referring to a pervasive and basic inability to take for granted all the certainties that others consider matters of fact in the social world, etc.84 The contemporary scales of social functioning were not designed to tap into these tacit, foundational dimensions of social functioning in schizophrenia. In fact, these scales seem only to scratch the surface of impaired social functioning. To advance knowledge of social functioning in schizophrenia, clarification and definition of the very concept of social functioning are urgently needed, constituting a necessary next step. For research on this complex topic to prosper, agreement about definition and the best assessment method is of paramount importance.

Limitations

Finally, our study faces several limitations, which must be noted. These include the absence of a clear definition of social functioning and impaired social functioning in this research field. In the absence of a clear definition of the concept of social functioning, we decided to leave the issue “open” and include studies that clearly stated that they assessed social functioning and how it was done. While clarifying the concept of social functioning is a crucial theoretical issue, it is also an issue that cannot be solved in a systematic review/meta-analysis.

Another limitation is inconsistencies in the classification of single symptoms into psychopathological subdomains (eg, the PANSS item N7—stereotyped thinking—is in different versions of PANSS 5-factor scales regarded as a positive, negative, disorganized, or an excitability symptom, respectively). Finally, the abundance of different assessment tools, often also used in different versions, to examine social functioning as well as psychopathology is a source of heterogeneity across studies, possibly reflecting the identified high level of heterogeneity in the results of the included studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark for funding this study and Dr. Povl Munk-Jørgensen for commenting on an early draft of this paper. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Rasmus Handest, Mental Health Center Amager, Copenhagen University Hospital, København V, Denmark.

Ida-Marie Molstrom, Mental Health Center Amager, Copenhagen University Hospital, København V, Denmark.

Mads Gram Henriksen, Mental Health Center Amager, Copenhagen University Hospital, København V, Denmark; Center for Subjectivity Research, Department of Communication, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Carsten Hjorthøj, Copenhagen Research Center for Mental Health—CORE, Mental Health Center Copenhagen, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark; Department of Public Health, Section of Epidemiology, University of Copenhagen, Hellerup, Denmark.

Julie Nordgaard, Mental Health Center Amager, Copenhagen University Hospital, København V, Denmark; Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

References

- 1. Molstrom I-M, Nordgaard J, Parnas A, Handest R, Berge J, Henriksen MG.. The prognosis of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression of 20-year follow-up studies. Schizophr Res. 2023;250:152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jaaskelainen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Green MF. Impact of cognitive and social cognitive impairment on functional outcomes in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(suppl 2):8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kharawala S, Hastedt C, Podhorna J, Shukla H, Kappelhoff B, Harvey PD.. The relationship between cognition and functioning in schizophrenia: a semi-systematic review. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2022;27:100217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thibaudeau E, Cellard C, Turcotte M, Achim AM.. Functional impairments and theory of mind deficits in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the associations. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(3):695–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malla A, Payne J.. First-episode psychosis: psychopathology, quality of life, and functional outcome. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(3):650–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Campellone TR, Sanchez AH, Kring AM.. Defeatist performance beliefs, negative symptoms, and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1343–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cotter J, Drake RJ, Bucci S, Firth J, Edge D, Yung AR.. What drives poor functioning in the at-risk mental state? A systematic review. Schizophrenia Res. 2014;159(2):267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsang HW, Leung AY, Chung RC, Bell M, Cheung WM.. Review on vocational predictors: a systematic review of predictors of vocational outcomes among individuals with schizophrenia: an update since 1998. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(6):495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Makinen J, Miettunen J, Isohanni M, Koponen H.. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62(5):334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eack SM, Newhill CE.. Psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(5):1225–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Halverson TF, Orleans-Pobee M, Merritt C, Sheeran P, Fett AK, Penn DL.. Pathways to functional outcomes in schizophreia spectrum disorders: meta-analysis of social cognitive and neurocognitive predictors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;105:212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ventura J, Hellemann GS, Thames AD, Koellner V, Nuechterlein KH.. Symptoms as mediators of the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2–3):189–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Watson P, Zhang JP, Rizvi A, Tamaiev J, Birnbaum ML, Kane J.. A meta-analysis of factors associated with quality of life in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;202:26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P.. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 10 ed. Hagerstown, UNITED STATES: Wolters Kluwer; 2017:3265. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huxley P, Krayer A, Poole R, Prendergast L, Aryal S, Warner R.. Schizophrenia outcomes in the 21st century: a systematic review. Brain Behav. 2021;11(6):e02172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2021;74(9):790–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R.. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(4):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wells GS, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell, P.. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Available at: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed September 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Health NIo. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed September 12, 2022.

- 21. Fisher RA. The design of experiments. Oxford, England: Oliver & Boyd; 1935. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Simonsen C, Sundet K, Vaskinn A, et al. Psychosocial function in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: relationship to neurocognition and clinical symptoms. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(5):771–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reininghaus U, Priebe S, Bentall RP.. Testing the psychopathology of psychosis: evidence for a general psychosis dimension. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(4):884–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins JP, Thompson SG.. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knapp G, Hartung J.. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22(17):2693–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C.. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Borenstein MH, Larry V; Higgins, Julian P. T; Rothstein, H.. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, et al. Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the effective health care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1187–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program] . Version: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in r with the metafor package. J Stat Soft. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meltzer HY, Burnett S, Bastani B, Ramirez LF.. Effects of six months of clozapine treatment on the quality of life of chronic schizophrenic patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41(8):892–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D.. National institute of mental health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia. Prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(3):239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bow-Thomas CC, Velligan DI, Miller AL, Olsen J.. Predicting quality of life from symptomatology in schizophrenia at exacerbation and stabilization. Psychiatry Res. 1999;86(2):131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Browne S, Clarke M, Gervin M, Waddington JL, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E.. Determinants of quality of life at first presentation with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Norman RM, Malla AK, McLean T, et al. The relationship of symptoms and level of functioning in schizophrenia to general wellbeing and the Quality of Life Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102(4):303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldberg JO, Schmidt LA.. Shyness, sociability, and social dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;48(2-3):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hansson L, Eklund M, Bengtsson-Tops A.. The relationship of personality dimensions as measured by the temperament and character inventory and quality of life in individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder living in the community. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(2):133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huppert JD, Weiss KA, Lim R, Pratt S, Smith TE.. Quality of life in schizophrenia: contributions of anxiety and depression. Schizophr Res. 2001;51(2-3):171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ritsner M, Kurs R, Ratner Y, Gibel A.. Condensed version of the quality of life scale for schizophrenia for use in outcome studies. Psychiatry Res. 2005;135(1):65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rocca P, Bellino S, Calvarese P, et al. Depressive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: different effects on clinical features. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005;46(4):304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bozikas VP, Kosmidis MH, Kafantari A, et al. Community dysfunction in schizophrenia: rate-limiting factors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(3):463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hofer A, Rettenbacher MA, Widschwendter Ch G, Kemmler G, Hummer M, Fleischhacker WW.. Correlates of subjective and functional outcomes in outpatient clinic attendees with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Eur Archi Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(4):246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Juckel G, Schaub D, Fuchs N, et al. Validation of the personal and social performance (PSP) Scale in a German sample of acutely ill patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;104(1-3):287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grant PM, Beck AT.. Defeatist beliefs as a mediator of cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(4):798–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schaub D, Brüne M, Jaspen E, Pajonk FG, Bierhoff HW, Juckel G.. The illness and everyday living: close interplay of psychopathological syndromes and psychosocial functioning in chronic schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261(2):85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Smith MJ, Horan WP, Karpouzian TM, Abram SV, Cobia DJ, Csernansky JG.. Self-reported empathy deficits are uniquely associated with poor functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1–3):196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Caqueo-Urizar A, Gutierrez-Maldonado J, Ferrer-Garcia M, Morales AU, Fernandez-Davila P.. Typology of schizophrenic symptoms and quality of life in patients and their main caregivers in northern Chile. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59(1):93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hueng TT, Wu JYW, Chang WC, Chuang SP.. Clinical symptoms, social cognition correlated with domains of social functioning in chronic schizophrenia. J Med Sci. 2013;33(6):341–347. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kundu PS, Sinha VK, Paul SE, Desarkar P.. Current social functioning in adult-onset schizophrenia and its relation with positive symptoms. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):65–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ladea M, Barbu CM, Juckel G.. Treatment effectiveness in patients with schizophrenia as measured by the ASSESS battery—First longitudinal data. Psychiatr Danub. 2015;27(4):364–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Menendez-Miranda I, Garcia-Portilla MP, Garcia-Alvarez L, et al. Predictive factors of functional capacity and real-world functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(5):622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Santosh S, Roy DD, Kundu PS.. Cognitive self-regulation, social functioning and psychopathology in schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24(2):129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tonna M, Ottoni R, Paglia F, Ossola P, De Panfilis C, Marchesi C.. Obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in schizophrenia: a Janus Bifrons effect on functioning. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;266(1):63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bechi M, Bosia M, Spangaro M, et al. Exploring functioning in schizophrenia: predictors of functional capacity and real-world behaviour. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee SJ, Kim KR, Lee SY, An SK.. Impaired social and role function in ultra-high risk for psychosis and first-episode schizophrenia: its relations with negative symptoms. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(5):539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Phalen PL, Dimaggio G, Popolo R, Lysaker PH.. Aspects of Theory of Mind that attenuate the relationship between persecutory delusions and social functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2017;56:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gonzalez-Blanco L, Garcia-Portilla MP, Dal Santo F, et al. Predicting real-world functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia: role of inflammation and psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280:112509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zizolfi D, Poloni N, Caselli I, et al. Resilience and recovery style: a retrospective study on associations among personal resources, symptoms, neurocognition, quality of life and psychosocial functioning in psychotic patients. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Porcelli S, Kasper S, Zohar J, et al. Social dysfunction in mood disorders and schizophrenia: Clinical modulators in four independent samples. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;99. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.109835. Epub 2019 Dec 11. PMID: 31836507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Charernboon T. Interplay among positive and negative symptoms, neurocognition, social cognition, and functional outcome in clinically stable patients with schizophrenia: a network analysis. F1000Res. 2021;10:1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Garcia-Portilla MP, Garcia-Alvarez L, Gonzalez-Blanco L, et al. Real-world functioning in patients with schizophrenia: beyond negative and cognitive symptoms. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:700747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lucarini V, Cangemi F, Daniel BD, et al. Conversational metrics, psychopathological dimensions and self-disturbances in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;6:997–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mucci A, Galderisi S, Gibertoni D, et al. ; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. Factors associated with real-life functioning in persons with schizophrenia in a 4-year follow-up study of the italian network for research on psychoses. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):550–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hu HX, Lau WYS, Ma EPY, et al. The important role of motivation and pleasure deficits on social functioning in patients with schizophrenia: a network analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(4):860–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA.. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:4953–4952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Andreasen NC. Scale for the assessment of positive symptoms. Iowa City, University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Overall JE, Gorham DR.. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10(3):799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, Nguyen L, et al. The brief negative symptom scale: psychometric properties. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):300–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Addington D, Addington J, Schissel B.. A depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(4):247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT.. The quality of life scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10:388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake S.. The social functioning scale. the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Padmavathi R, Thara R, Srinivasan L, Kumar S.. Scarf social functioning index. Ind J Psychiatry. 1995;37(4):161–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schneider LC, Struening EL.. SLOF: a behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Soc Work Res Abstr Fall. 1983;19(3):9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Harvey PD, Deckler E, Jarskog F, Penn DL, Pinkham AE.. Predictors of social functioning in patients with higher and lower levels of reduced emotional experience: social cognition, social competence, and symptom severity. Schizophr Res. 2019;206:271–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bhagyavathi HD, Mehta UM, Thirthalli J, et al. Cascading and combined effects of cognitive deficits and residual symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia - A path-analytical approach. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(1–2):264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lindhardt L, Nilsson LS, Munk-Jørgensen P, Mortensen OS, Simonsen E, Nordgaard J.. Unrecognized schizophrenia spectrum and other mental disorders in youth disconnected from education and work-life. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1015616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Blankenburg W. Der Versagenszustand bei latenten Schizophrenien*. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1968;93(02):67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Häfner H, Löffler W, Maurer K, Hambrecht M, an der Heiden W.. Depression, negative symptoms, social stagnation and social decline in the early course of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100(2):105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York: International Universities Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Minkowski E. Du symptome au trouble générateur. Au-delà du rationalisme morbide. Paris: Éditions l’Harmattan; 1997:93–124. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Urfer-Parnas A. Eugène Minkowski. In: Stanghellini G, Broome M, Fernandez A, Fusar Poli P, Raballo A, Rosfort R, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Phenomenological Psychopathology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Blankenburg W. Der Verlust der natürlichen Selbstverständlichkeit; ein Beitrag zur Psychopathologie symptomarmer Schizophrenien: Enke, Stuttgart; 1971. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.