In selecting my topic for the 2023 Victor T. Curtin Lecture at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute I reflected that in his 57 years there the changes in Ophthalmology were profound. He helped guide those changes and train a generation of Ophthalmologists who further expanded the horizons of Ophthalmology. The changes in retinoblastoma during my career have also been profound and I reflected that what most residents were taught during their residency about retinoblastoma has changed and is no longer applicable. Since the average Ophthalmologist may see only one retinoblastoma during his/her post residency career (and then refer for management) I decided to dedicate this lecture to Dr. Curtin and in reflecting on his long and productive career demonstrate how what most practicing Ophthalmologists learned in their residency about retinoblastoma is no longer accurate. I have chosen to highlight ten things you may have been taught that have changed.

Background:

Retinoblastoma is a rare but highly malignant cancer of the retina. Ninety-five percent of all cases appear before the age of 5 years. Rare cases do appear however throughout life (even into the 7th decade) and those rare cases often confuse clinicians and present as uveitis like cases. Untreated it is universally fatal. One third of cases are bilateral and bilateral cases are diagnosed earlier (at 1 year of age) than unilateral cases (at 2 years of age)(1). In the United States and European countries uveal melanoma is the most common primary intraocular cancer but worldwide retinoblastoma is the most common primary cancer in humans(2).

There is no central U.S. registry but perhaps 275 children are affected yearly in the U.S. The estimates for worldwide range from 5,000 to 8,000. Enucleation was first done for retinoblastoma hundreds of years ago and remains an effective way to cure the cancer. Recent studies from the U.S. demonstrated that primary enucleation for unilateral retinoblastoma is associated with a 4% chance of developing metastases and just under 2% chance of dying from metastatic retinoblastoma(3). Enucleation remains a useful and effective way to cure the cancer but for more than 90 years Ophthalmologists have developed techniques that salvage eyes without the need for enucleation. Presently we enucleate only 6% of eyes in New York at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the largest and oldest retinoblastoma center in the U.S.(4).

Here are the 10 things I have chosen to highlight that have changed since most Ophthalmologist were residents:

1. External Beam Radiation Should Be Used to Cure (Bilateral) Retinoblastoma.

Radiation has been successfully used in the treatment of retinoblastoma since 1903. Until the 1960’s (when Meyer-Schwickerath introduced the Xenon arc photocoagulator) it was the only alternative to enucleation(5). Prior to that all unilateral and all bilateral retinoblastoma eyes were enucleated. Reese in the U.S. and Stallard in England developed external beam techniques that enabled successful treatment of the tumor with retention of the eye and sometimes vision. It was revolutionary. In the 1950’s Reese popularized the concept of enucleating the worse eye and radiating the better eye in bilateral cases. That approach was done worldwide for 50 years with success. We reported success in radiating both eyes in both advanced cases (Reese-Ellsworth groups IV and V)(6) and less advanced cases (Reese-Ellsworth Groups I-III)(7). Although radiation is used in the treatment of 50% of all human cancers it is rarely curative when used alone for solid cancers. Retinoblastoma remained the “poster child” of radiation as doses that were tolerated by the eye were usually curative.

Unfortunately long term follow-up of radiated cases revealed that children with the genetic form of retinoblastoma (bilaterals and some unilaterals) had an increased chance of developing a non-ocular second(8) (or third or fourth or fifth)(9) cancer and some of that was attributable to the effect of external beam radiation. Without radiation the genetic related retinoblastoma patients develop cancer more commonly than the population but that risk is significantly increased in those receiving external beam radiation (the risk is not increased in patients receiving brachytherapy).The risk of a second cancer in a radiated patient is ½ to 1% a year, attaining 50% in 50 years and at least half of those patients die as a consequence(10). In fact, the most common cause of death in the US in retinoblastoma patients has been from second non-ocular cancers not metastases(11).

External beam irradiation is no longer used in the treatment of intraocular retinoblastoma.

2. All unilateral retinoblastoma eyes should be enucleated.

Enucleation remains an excellent treatment for intraocular retinoblastoma especially in centers and countries where intraarterial chemotherapy is not practical.. It is a quick, minimally painful outpatient procedure with an acceptable cosmetic result. Four percent of patients who have primary enucleation for unilateral retinoblastoma develop metastases and just under 2% die(3). The metastases develop before removal of the eye.

Reese believed that all unilateral eyes with retinoblastoma should be enucleated. We began to challenge that dogma in the 1980’s when we demonstrated that external beam radiation could be used for unilateral retinoblastoma(12). We saved all eyes that were Group I-III but few of the Groups V eyes (eyes with seeding). Importantly patient survival was not compromised.

At MSKCC the majority of unilateral eyes are no longer enucleated and patient survival remains as high as primary enucleation. These eyes are treated with intraarterial chemotherapy and there are two circumstances when we can avoid enucleation.

Some eyes with unilateral retinoblastoma can attain useful vision-including many that will have normal central vision (there is aways a visual field defect from the tumor itself)(11). An example of such eyes is seen in Figure 1.

Worldwide as many as 40% of families delay or refuse enucleation or any treatment and the children die(13). They refuse enucleation for cultural, religious, economic and social reasons; this is most prevalent in low and middle income countries (the majority of the world’s population) but throughout all economic levels in Africa, Asia and Latin America. These families accept intarterial chemotherapy and even systemic chemotherapy but refuse enucleation. Their choice is not intraarterial chemotherapy vs. enucleation. It is intarterial chemotherapy vs death. At MSKCC we have extensive experience with these patients and while few of these very advanced eyes retain much vision the children live and patient survival is >99%. In contrast all the children who refuse enucleation die.

Figure 1:

Before (left) and after (right) intraarterial chemotherapy

In 2023 the majority of eyes with unilateral retinoblastoma can be saved and enucleation as a primary treatment is not the only option.

3. Systemic chemotherapy cures intraocular retinoblastoma.

Systemic chemotherapy was first used for intraocular retinoblastoma in 1953 by Kupfer. When the impact of external beam irradiation on the development of second cancers was recognized, clinicians worldwide looked to systemic chemotherapy as a substitution. Retinoblastoma was known to be a cancer very sensitive to a wide variety of chemotherapeutic agents but it was Murphree in the U.S. and Hungerford in the U.K who popularized carboplatin based regimes. Virtually 100% of tumors respond quickly (change apparent in a month) to intravenous chemotherapy. If there is no seeding a tumor may shrink enough to be successfully destroyed with laser/cryo/brachytherapy. But if not additionally treated focally almost all of these shrunken tumors regrow within months. Unfortunately, the majority (>75%) of eyes with unilateral retinoblastoma have vitreous (and/or sub-retinal) seeding and systemic chemotherapy rarely (?never) is curative for eyes with vitreous seeding and sub-retinal seeding. Reading the literature on this subject can be confusing. Authors report on the success of eyes with seeding treated with chemotherapy…..but do not include the fact that the majority of eyes with seeding in their center were enucleated. This has been discussed in detail in the literature(14).

And systemic chemotherapy has its downsides. In the short term the children experience fever/neutropenia or may need transfusions, they usually require ports with the associated costs, infection and complications. They cannot be immunized, usually are placed on prophylactic antibiotics for months, skeletal growth is retarded, permanent hearing loss develops (in some series-in young children as often as 40% of the time) and develop secondary leukemia. The incidence of secondary leukemia has been debated in the literature following the initial report in 2007 (15). A recent analysis suggests the use of systemic chemotherapy for retinoblastoma increases the chance of a secondary leukemia 140 fold; almost all of these children die from the leukemia(16).

As a result of all of the above systemic chemotherapy use worldwide is on the decline. A survey of clinicians worldwide revealed that intrarterial chemotherapy is preferred over systemic chemotherapy as first line treatment. At MSKCC we have abandoned its use and have not used it for 16 years!

Systemic chemotherapy alone does not cure retinoblastoma-if followed by focal treatments eyes can be saved. The majority of eyes with retinoblastoma cannot be cured with systemic chemotherapy alone.

4. Intravitreal injections are dangerous in retinoblastoma

It is well known that doing surgery on a retinoblastoma eye with active tumor can be dangerous. That’s why retinoblastoma is one of the few cancers treated without biopsy. Extraocular extension (and death) has been reported following cataract surgery, retinal detachment surgery, glaucoma procedures and vitrectomy. In a recent study more than half the children who had inadvertent intraocular surgery when retinoblastoma was not suspected died(17). Cataract surgery in retinoblastoma eyes that have no active disease is safe.

Despite this, clinicians have cautiously tried intravitreal injections in retinoblastoma eyes for more than 50 years. Pharmacologic studies suggested that the drug levels and duration of drug remaining in the vitreous might be curative and techniques to maximize safety were developed(18). These collective observations were codified by Munier in 2010(2). For safety the eye is softened (with anterior chamber taps or digital massage), a small needle is used (we use a 33g needle), a small volume is used (0.05–0.066cc), UBM is used to avoid injecting directly into a tumor mass and cryo is applied to the needle before and when the needle is retracted to “seal” the hole when the needle is removed (Figure 2)(19). A worldwide review of 3,553 injections in 655 patients using that safety protocol revealed no case of extraocular extension(20).

Figure 2:

PGD: Pre Implantation Genetic Diagnosis

What about efficacy and toxicity? It is beyond the scope of this paper to review this in detail but intravitreal Melphalan at doses of 20–30Gμ cures more than 95% of vitreous seeding (with a loss of 5% of ERG function with each injection on average)(21). Recently is has been shown that intravitreal Topotecan at doses of 90Gμ is very effective and less toxic.

Intravitreal chemotherapy is safe and effective when used with enhanced safety protocols.

5. Metastatic retinoblastoma is incurable.

When I finished my fellowship in ophthalmic oncology there were no survivors of metastatic retinoblastoma worldwide. No combination of conventional chemotherapy, surgery and radiation was curative. Cure rates now are well over 50% and in many centers much higher. Patients with CNS disease still have a poor outcome but for the majority of patients who have marrow and organ involvement without CNS disease long term curative rates exceed 80%. This was accomplished through worldwide collaboration of pediatric oncologists and the protocol involved high dose multiagent systemic chemotherapy with bone marrow transplant and sometimes focal radiation(22). Short and longer time side effects are significant but many of these children live normal lives post treatment.

Metastatic retinoblastoma is curative.

6. Genetic testing is good but doesn’t influence what you can do.

The genetic defect responsible for retinoblastoma was cloned in 1986. It is a classic tumor suppressor gene located on the long arm of chromosome 13 and present in normal humans. It is the loss of functioning of the gene that promotes cancer and as such follows classic autosomal dominant inheritance. Genetic counselling is now standard for all families/children with retinoblastoma. But some have said that counselling is fine but families with known genetic defect have few acceptable alternatives once they learn that there is a 50% chance that their child will get bilateral disease. Not having children, donor sperm or egg or adopting children are reasonable alternatives but rarely chosen by families.

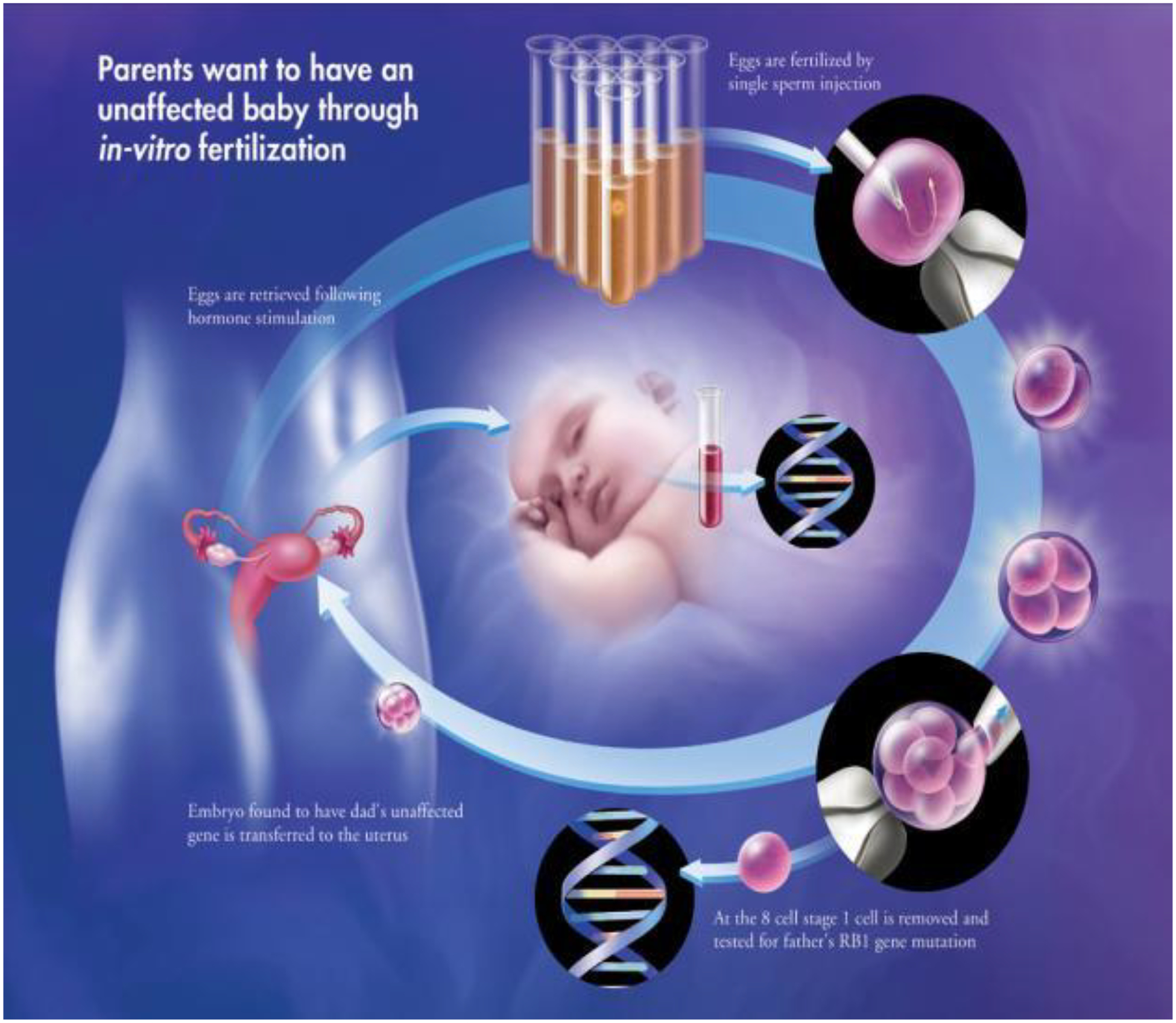

Fortunately, there is PGD. PGD (Pre implantation Genetic Diagnosis) is an accepted assisted reproductive technique that we first employed for retinoblastoma (in 2003). It starts by first identifying the mutation in the affected parent and creating nested PCR probes. Then in vitro fertilization is performed by inserting one sperm into one harvested egg (usually about 20 eggs are fertilized). Instead of implanting that into the uterus you wait three days in vitro, At three days the embryo is typically 8 cells, You then micropipette out one of the 8 cells (a 7 cell embryo develops without difficulty) and using the PCR probes can identify which of the fertilized eggs has the retinoblastoma genetic abnormality. The fertilized egg without the defect is then implanted into the uterus (23)the number of fertilized eggs inserted depends on the age of the mother and the wishes of the family). The child will have all the genes from both parents-no gene has been added, removed or altered-you have just pre selected the fertilized egg without the Rb genetic defect. Since publishing this in 2003 it is now widely available worldwide(23). (Figure 3)

Figure 3:

Second Cancers in Retinoblastoma Survivors

Genetic testing can lead to PGD enabling a family to have their own child without retinoblastoma.

7. Screening for second cancer saves lives.

Once it was recognized that retinoblastoma patients with germline disease were at risk for the development of second (and third, fourth and fifth) cancers most centers instituted screening to detect these cancers at an earlier stage with the hope that earlier detection would lead to better outcomes. The location and timing of these second cancers is well established so imaging studies focused on different areas depending how long it was after primary tumor treatment. Figure 3 These strategies did detect cancer earlier, by some estimates at least a year earlier than patients developed signs or symptoms but unfortunately there was no improvement in survival(24–26). This was true for sarcomas of the head and extremity. To date there is no effective screening for women who are risk (perhaps 2%) to develop uterine sarcomas (which are usually fatal)(27).

Three and a half percent of germline patients develop midline brain tumors-all in the first three years of life. They have been called “trilateral retinoblastoma” and most commonly develop in the pineal gland but can also be in the suprasellar area or even the cerebellum. Half of the patients who develop trilateral disease have the brain tumor detected before the diagnosis of retinoblastoma, so the incidence once diagnosed with retinoblastoma is under 2%. There are many strategies employed worldwide for the detection-all based on MR imaging. Some do scans every three months (for 5 years) while others scan every 6 or 12 months till the age of 3 or 5. Scanning does detect these tumors earlier (a year) than when patients have signs/symptoms but survival is the same….and poor. While a few patients (perhaps 25%) with trilateral retinoblastoma survive most die despite aggressive surgery and chemotherapy(28).

MRI screening for second non ocular cancers does not improve survival

8. All retinoblastoma is caused by abnormalities in the RB1 gene

The Rb1 gene encoded by chromosome 13 is a tumor suppressor gene and loss of function predisposes you to retinoblastoma. There are many molecular mechanisms for derangement including mutation, LOH (loss of heterozygosity), large deletions, translocations and inversions in addition to possible contributing factors of promoter abnormalities and the autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance has repeatedly been found. Analysis of tumors demonstrates the mechanism of derangement in each allele (the “two hit hypothesis”). Over the years however, rare patients were found where no Rb1 abnormality was identified. Finally, Gallie and colleagues identified another abnormality in patients with unilateral, unifocal retinoblastoma diagnosed at a younger age and they believed that these patients had a more aggressive course(29). Rather than mutation or any abnormality of the Rb1 gene they found amplification of N-MYC. N-MYC is a transcription factor dysregulated in many cancers, most notable neuroblastoma. It was known that N-MYC was altered in many retinoblastomas but not that it alone could drive the development of retinoblastoma.

All retinoblastoma is not caused by Rb1 abnormalities alone

9. Delaying enucleation increases the chance of metastatic disease

Since enucleation is so effective and easily done worldwide it isn’t surprising that clinicians should ask if attempting to save an eye carries with it an increased chance of metastases. Patients who were treated with just xenon arc photocoagulation, laser, cryotherapy and or brachytherapy did not have an increased chance of developing metastases but some pointed out that those eyes were less involved with tumor so they were less likely to metastasize. There were no head-to-head comparisons of bilateral enucleation with bilateral radiation (or bilateral patients where one eye was removed and the remaining eye radiated) but survival rates were the same. Since there were no randomized trials the possibility of selection bias is possible.

When clinicians abandoned radiation for eyes with seeding (Reese-Ellsworth Vb, International Classification “D” and “E” and eyes were not enucleated survival was not impacted. And two additional observations further support the safety of leaving an eye in and treating it. The first is that-worldwide- more than 99% of patients treated with intraarterial chemotherapy for “D” and “E” eyes do not develop metastases. Most centers report no deaths after more than 10 year experience with this approach. Again, no randomized trials but in our center at MSKCC 95% of all patients receive intraarterial chemotherapy-including very advanced eyes so a selection bias is unlikely. Finally, our work with plasma cell free DNA strongly suggests that all metastases are either present at the time of retinoblastoma treatment or not and saving the eye does not contribute to metastases.

Saving an eye instead of enucleating it does not increase the chance of developing metastases.

10. Patients who have isolated choroidal invasion need adjuvant systemic chemotherapy.

It was previously thought that patients who had pathologic evidence of choroidal invasion needed adjuvant multiagent systemic chemotherapy. Indeed, when these patients received chemotherapy, their outcome was excellent and few, if any died. Detailed studies showed that patients with isolated choroidal invasion (that is, without concurrent optic nerve invasion, glaucoma or extraocular extension) did equally well when they received no chemotherapy(16, 30). The use of adjuvant systemic chemotherapy for patients who have isolated choroidal invasion has been abandoned.

Patients who have pathologic proof of isolated choroidal invasion do not need adjuvant systemic chemotherapy.

References

- 1.Dimaras H, Corson TW, Cobrinik D, White A, Zhao J, Munier FL, et al. Retinoblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munier FL, Beck-Popovic M, Chantada GL, Cobrinik D, Kivelä TT, Lohmann D, et al. Conservative management of retinoblastoma: Challenging orthodoxy without compromising the state of metastatic grace. “Alive, with good vision and no comorbidity”. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019;73:100764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu JE, Francis JH, Dunkel IJ, Shields CL, Yu MD, Berry JL, et al. Metastases and death rates after primary enucleation of unilateral retinoblastoma in the USA 2007–2017. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(9):1272–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramson DH, Fabius AW, Issa R, Francis JH, Marr BP, Dunkel IJ, et al. Advanced Unilateral Retinoblastoma: The Impact of Ophthalmic Artery Chemosurgery on Enucleation Rate and Patient Survival at MSKCC. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramson DH. The focal treatment of retinoblastoma with emphasis on xenon arc photocoagulation. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl (1985). 1989;194:3–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abramson DH, Ellsworth RM, Tretter P, Adams K, Kitchin FD. Simultaneous bilateral radiation for advanced bilateral retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(10):1763–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abramson DH, Ellsworth RM, Tretter P, Javitt J, Kitchin FD. Treatment of bilateral groups I through III retinoblastoma with bilateral radiation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(10):1761–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson DH. Retinoblastoma in the 20th century: past success and future challenges the Weisenfeld lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(8):2683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abramson DH, Melson MR, Dunkel IJ, Frank CM. Third (fourth and fifth) nonocular tumors in survivors of retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(10):1868–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eng C, Li FP, Abramson DH, Ellsworth RM, Wong FL, Goldman MB, et al. Mortality from second tumors among long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(14):1121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abramson DH. Retinoblastoma: saving life with vision. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:171–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramson DH, Marks RF, Ellsworth RM, Tretter P, Kitchin FD. The management of unilateral retinoblastoma without primary enucleation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(8):1249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Traoré F, Sylla F, Togo B, Kamaté B, Diabaté K, Diakité AA, et al. Treatment of retinoblastoma in Sub-Saharan Africa: Experience of the paediatric oncology unit at Gabriel Toure Teaching Hospital and the Institute of African Tropical Ophthalmology, Bamako, Mali. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(8):e27101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramson DH, Daniels AB, Marr BP, Francis JH, Brodie SE, Dunkel IJ, et al. Intra-Arterial Chemotherapy (Ophthalmic Artery Chemosurgery) for Group D Retinoblastoma. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gombos DS, Hungerford J, Abramson DH, Kingston J, Chantada G, Dunkel IJ, et al. Secondary acute myelogenous leukemia in patients with retinoblastoma: is chemotherapy a factor? Ophthalmology. 2007;114(7):1378–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pendri PR, Chantada G. Controversies in the Management of Choroidal Invasion in Retinoblastoma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2022;62(4):27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaliki S, Taneja S, Palkonda VAR. INADVERTENT INTRAOCULAR SURGERY IN CHILDREN WITH UNSUSPECTED RETINOBLASTOMA: A Study of 14 Cases. Retina. 2019;39(9):1794–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carcaboso AM, Bramuglia GF, Chantada GL, Fandiño AC, Chiappetta DA, de Davila MT, et al. Topotecan vitreous levels after periocular or intravenous delivery in rabbits: an alternative for retinoblastoma chemotherapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(8):3761–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chévez-Barrios P, Chintagumpala M, Mieler W, Paysse E, Boniuk M, Kozinetz C, et al. Response of retinoblastoma with vitreous tumor seeding to adenovirus-mediated delivery of thymidine kinase followed by ganciclovir. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7927–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis JH, Abramson DH, Ji X, Shields CL, Teixeira LF, Schefler AC, et al. Risk of Extraocular Extension in Eyes With Retinoblastoma Receiving Intravitreous Chemotherapy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(12):1426–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francis JH, Brodie SE, Marr B, Zabor EC, Mondesire-Crump I, Abramson DH. Efficacy and Toxicity of Intravitreous Chemotherapy for Retinoblastoma: Four-Year Experience. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(4):488–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunkel IJ, Piao J, Chantada GL, Banerjee A, Abouelnaga S, Buchsbaum JC, et al. Intensive Multimodality Therapy for Extraocular Retinoblastoma: A Children’s Oncology Group Trial (ARET0321). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(33):3839–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu K, Rosenwaks Z, Beaverson K, Cholst I, Veeck L, Abramson DH. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for retinoblastoma: the first reported liveborn. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheen V, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, Seddon JM, Kleinerman RA. Cancer screening practices of adult survivors of retinoblastoma at risk of second cancers. Cancer. 2008;113(2):434–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonorezos ES, Friedman DN, Barnea D, Bosscha MI, Chantada G, Dommering CJ, et al. Recommendations for Long-Term Follow-up of Adults with Heritable Retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(11):1549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman DN, Hsu M, Moskowitz CS, Francis JH, Lis E, Fleischut MH, et al. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging as surveillance for subsequent malignancies in preadolescent, adolescent, and young adult survivors of germline retinoblastoma: An update. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(7):e28389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francis JH, Kleinerman RA, Seddon JM, Abramson DH. Increased risk of secondary uterine leiomyosarcoma in hereditary retinoblastoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(2):254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunkel IJ, Jubran RF, Gururangan S, Chantada GL, Finlay JL, Goldman S, et al. Trilateral retinoblastoma: potentially curable with intensive chemotherapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(3):384–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rushlow DE, Mol BM, Kennett JY, Yee S, Pajovic S, Thériault BL, et al. Characterisation of retinoblastomas without RB1 mutations: genomic, gene expression, and clinical studies. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosaleh A, Sampor C, Solernou V, Fandiño A, Domínguez J, de Dávila MT, et al. Outcome of children with retinoblastoma and isolated choroidal invasion. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(6):724–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]