Abstract

Resistance to antibiotics and heavy metals in Antarctic bacteria has been investigated due to anthropogenic impact on the continent. However, there is still much to learn about the genetic determinants of resistance in native bacteria. In this study, we investigated antibiotic, heavy metal, and metalloid resistance in Pseudomonas sp. AU10, isolated from King George Island (Antarctica), and analyzed its genome to look for all the associated genetic determinants (resistome). We found that AU10 displayed resistance to Cr(VI), Cu(II), Mn(II), Fe(II), and As(V), and produced an exopolysaccharide with high Cr(VI)-biosorption capacity. Additionaly, the strain showed resistance to aminopenicillins, cefotaxime, aztreonam, azithromycin, and intermediate resistance to chloramphenicol. Regarding the resistome, we did not find resistance genes in AU10’s natural plasmid or in a prophage context. Only a copper resistance cluster indicated possible horizontal acquisition. The mechanisms of resistance found were mostly efflux systems, several sequestering proteins, and a few enzymes, such as an AmpC β-lactamase or a chromate reductase, which would account for the observed phenotypic profile. In contrast, the presence of a few gene clusters, including the terZABCDE operon for tellurite resistance, did not correlate with the expected phenotype. Despite the observed resistance to multiple antibiotics and heavy metals, the lack of resistance genes within evident mobile genetic elements is suggestive of the preserved nature of AU10’s Antarctic habitat. As Pseudomonas species are good bioindicators of human impact in Antarctic environments, we consider that our results could help refine surveillance studies based on monitoring resistances and associated resistomes in these populations.

Keywords: Antarctica, Pseudomonas, Genome analysis, Heavy metal resistance, Antibiotic resistance

Introduction

The unperturbed nature of Antarctica is being threatened by human activities, including the expanding ship-borne tourism industry and the operations of research stations [1]. Consequently, an alarm has been raised over the levels of contamination with hydrocarbons, antibiotics, and heavy metals, but also with regard to the introduction of non-indigenous bacteria that could be spreading resistance genes related to these toxic compounds [2–4]. During the past two decades, different studies analyzed the resistance profiles to antibiotics and/or heavy metals of bacterial collections obtained from different Antarctic ecosystems, such as soils, freshwaters, seawaters, bird feces, and invertebrates [4–12]. All these studies reported resistances in virtually all isolates, and some of them proposed that these profiles could be indicative of anthropogenic impact [5–7]. However, the sole observation of broad resistance profiles is insufficient to ensure an anthropogenic causality, since native Antarctic bacteria have a background resistance that stems from intrinsic mechanisms vertically inherited over generations [1, 13]. The distinction between background resistance and anthropogenic-caused resistance, acquired horizontally through mobile genetic elements, has been considered a difficult issue [10, 13, 14]. Accordingly, some reports included genotypic analyses of their bacterial collections to make correlations with the observed resistance profiles. For instance, plasmids and integrons have been searched for, and screenings for specific resistance genes were carried out with PCR strategies [4, 11, 12, 15]. More recent studies used culture-independent methods, such as metagenomics, to study the antibiotic or heavy metal resistome from different Antarctic areas, providing a better understanding of the intrinsic and acquired mechanisms of resistance present in these environments [13, 14, 16–18]. Regardless of the strategy used, several of these works pointed to an increase in resistance and/or resistance-associated genes in sampling sites with anthropogenic impact [4, 6, 7, 9, 18, 19].

Pseudomonas isolates were frequently overrepresented in collections of Antarctic bacteria resistant to heavy metals and antibiotics [4, 7, 10–12]. Some members of this genus are recognized as opportunistic pathogens in both animals and humans, particularly the species Pseudomonas aeruginosa and, to a lesser extent, the environmental Pseudomonas spp. from the fluorescens complex [20, 21]. The emergence of multidrug-resistant strains among these opportunistic pathogens, which are difficult to treat, is a matter of concern. As a result, significant efforts have been directed towards characterizing the genetic determinants responsible for these resistances (see reviews [20–22]). Pseudomonas spp. are also recognized for their bioremediation potential regarding heavy metal pollution [23, 24]. Given all this, members of the Pseudomonas genus are promising candidates for studying the spread of antibiotic and heavy metal resistance as indicators of human contamination in Antarctic environments.

To address the influence of human activities on freshwater ecosystems from King George Island (Antarctica), our group monitored for 5 years the abundant populations of Pseudomonas spp. as bioindicators [25]. Pseudomonas sp. AU10 is a representative isolate collected from one of the studied freshwater bodies, the Uruguay Lake, which is considered to have medium to high human impact [25, 26]. This psychrotolerant strain became a model for our group due to its great ability to produce cold-active enzymes, some of which were biochemically characterized [27–29]. Recently, we have sequenced AU10’s genome and the only plasmid it harbors (GenBank accessions: JAIUXL000000000, OQ302170; unpublished, manuscript in preparation). In the present work, we analyzed the resistance profile of AU10 to several antibiotics, heavy metals and metalloids, and we traced the associated resistome determinants by analyzing its sequenced genome. Our goal was to refine the link between genetic determinants with the phenotypic profile of the strain. We believe this approach would aid in refining future surveillance strategies based on monitoring the resistance profile and resistome of Pseudomonas populations from Antarctic freshwater environments exposed to different human impacts.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and culture conditions

Pseudomonas sp. AU10 was originally isolated from Uruguay Lake, at King George Island, Antarctica [26]. It was stored at −80 °C in 20% glycerol and cultured in LB broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl, pH 7.4) or LB with 1.5% agar to obtain pure fresh cells for further analyses. All assays were performed at 28 °C, the optimal growth temperature of this psychrotolerant strain [28].

Heavy metal and metalloid resistance

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for different metal(loid)s was assayed based on the methodology from other reports [12, 30, 31]. Briefly, AU10 was cultured in tubes containing 2 mL of LB broth supplemented with different concentrations of chromium (VI) (0.02–20 mM), copper (II) (0.1–10 mM), iron (II) (1–10 mM), manganese (II) (1–10 mM), tellurite (IV) (0.01–10 mM) or arsenate (V) (100–400 mM). The following salts were used to prepare the stock solutions in pure water: K2Cr2O7, CuSO4·5H2O, FeSO4, MnCl2, K2TeO3, and Na2HAsO4·7H2O. For each metal(loid) concentration, triplicate liquid cultures were incubated at 28 °C and 200 rpm, starting from a 1/1000 dilution of an overnight fresh pre-culture. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration that completely prevented visible growth after 48-h incubation (absence of turbidity in the triplicates for a dilution point). The growth profile of AU10 facing different concentrations of Cr(VI) in LB broth (50 mL) was followed for 6 days by turbidimetry in an spectrophotometer (optical density at 620 nm).

Cr(VI) biosorption ability of AU10’s exopolysaccharide (EPS)

To evaluate Cr(VI) sorption ability, EPS were first purified from AU10 cultures grown in LB broth at 28 °C until late exponential phase. Briefly, cultures were centrifuged and EPS from supernatants were precipitated by the addition of cold ethanol, as described by Del Gallo and Haegi [32]. The EPS were then suspended in water and dialyzed (membrane cut-off of 10.000 kDa), and the carbohydrate content was determined by the Anthrone method [33]. Then, fractions of the EPS were exposed for 1 h to 200 mg/L Cr(VI), repurified, and analyzed for Cr(VI) sorption levels using the diphenylcarbazide reagent method, as described in Morel et al. [34]. The relative sugar composition of AU10’s EPS was analyzed by HPLC as described by Bahat-Samet et al. [35].

Antibiotic resistance profile

The antibiotic resistance profile of AU10 was analyzed using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method or MIC determination by E-test or Sensititre. All procedures were carried out following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standards from 2022, except for an incubation temperature of 28 °C instead of 35 ± 2 °C [36]. The antibiotic discs (Oxoid) used in this study were: amikacin (30 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanate (20/10 μg), ampicillin-sulbactam (10/10 μg), azithromycin (15 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftazidime-clavulanate (30/10 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), meropenem (10 μg), piperacillin-tazobactam (100/10 μg), streptomycin (300 μg), and tetracycline (30 μg). The presence of a halo of growth inhibition around the disc after an incubation of 24 h was interpreted as susceptibility; a complete absence of a halo was interpreted as a resistant phenotype. Synergy tests were performed to look for the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and metallo-β-lactamases, as described in Piersigilli et al. [37]. Briefly, discs of meropenem, EDTA, imipenem, ceftazidime, ceftazidime-clavulanate, and cefepime were placed in an orderly fashion to look for alterations in the inhibition zones caused by synergistic effects. Production of carbapenemases was also searched with the Blue-Carba method [38].

E-tests (Biomérieux) were performed for azithromycin, ceftazidime, chloramphenicol, imipenem, meropenem, and tetracycline. The Sensititre automated system (Thermo Scientific) for Gram-negative bacteria was also used, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For MIC interpretation, the cut-off points from the CLSI 2022 guidelines for other non-Enterobacterales, including Pseudomonas spp. were taken as a reference [36]. These breakpoints were previously validated for the clinical use of antibiotics in humans.

Resistome analysis

To look for the resistome of AU10 to antibiotics and metal(loid)s, we analyzed its complete genome (GenBank accession: JAIUXL000000000), including its natural plasmid (GenBank accession: OQ302170). The genomic sequences were annotated using RASTtk in the BV-BRC server (https://www.bv-brc.org/), and the antibiotic resistance genes were searched using the CARD and PATRIC databases within the server [39–42]. Genes involved in antibiotic and heavy metal resistance were also searched after subsystem analysis of the annotated genome within the BV-BRC server, and after the analysis of BRITE hierarchies and KEGG pathways in the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) [43, 44]. To identify metal(loid) resistance genes, we supplemented the analysis with a manual keyword search of the annotated genome, incorporating relevant terms such as metal names and their abbreviations. To identify prophages, transposons, and insertion sequences located in proximity to resistance genes, we used the PhiSpy program, the PHASTER program, and the TnCentral server (https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/), which incorporates the ISFinder database [45–48].

Results and discussion

The main focus of our research was to study the resistance profile of the Antarctic strain Pseudomonas sp. AU10 against antibiotics, heavy metals, and metalloids. Additionally, we aimed to understand the genetic basis of this resistance by analyzing its sequenced genome and identifying the associated resistome. Regarding heavy metals and metalloids, we evaluated AU10’s resistance by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of Cr(VI), Cu(II), Mn(II), Fe(II), As(V), and Te(IV), with the latter two being metalloids. The results obtained are presented in Table 1. As the breakpoint that makes a bacterium resistant to a certain metal(loid) is arbitrary, we followed the criteria used in other reports for environmental bacteria, such as Antarctic soil bacteria [7, 12, 31]. The MIC breakpoints of these studies were 10 mM for As(V) and 1 mM for the remaining metal(loid)s. Taking this into account, AU10 could be considered resistant to Cr(VI), Cu(II), Mn(II), Fe(II), and As(V), but susceptible to Te(IV) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pseudomonas sp. AU10 minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for different metal(loids)

| Metal(loid) | MIC1 |

|---|---|

| Cr(VI) | 2 mM (104 ppm) |

| Cu(II) | 4 mM (318 ppm) |

| Mn(II) | 6 mM (330 ppm) |

| Fe(II) | 7 mM (391 ppm) |

| As(V) | 200 mM (14984 ppm) |

| Te(IV) | 70 μM (9 ppm) |

1ppm were calculated using the atomic weight of the metal(loid) species

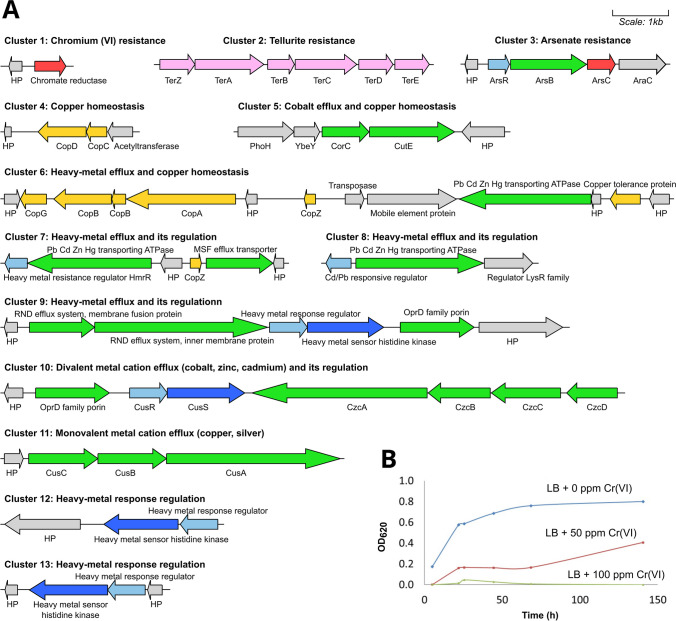

The analysis of AU10’s genome allowed us to identify 13 gene clusters involved in metal(loid) resistance and homeostasis that could correlate with the MIC results (Fig. 1a). Only few genes encoded sequestering proteins or enzymes involved in redox transformation of the toxic species, while most gene clusters were involved in efflux systems from the RND (resistance-nodulation-division), MFS (major facilitator superfamily), and ABC (ATP-binding cassette) families. Regulatory genes, including those encoding two-component systems, were often found close to these efflux system genes, suggesting an induction of the pumps only in the presence of toxic amounts of these metal(loid)s. All the clusters were located in chromosomal sequences, and most showed no mobile genetic elements or recombinases flanking them. Only cluster 6 included an insertion sequence of the IS66 family in between (Fig. 1a), indicating the possibility of a horizontal acquisition. This cluster contained most of the cop genes present in AU10’s genome and a heavy metal extruding ATPase. Genes encoding Cop proteins were also identified in the fourth and seventh clusters (Fig. 1a). Cop proteins are involved in copper import, sequestration, and detoxification in the periplasm and outer membrane layer [49, 50]. Among them, CopA has multicopper oxidase activity and binds up to 11 copper ions in the periplasm of different Pseudomonas species [50]. Astounding levels of copper accumulation were reported for Pseudomonas syringae carrying the copABCDRS operon on a plasmid, leaving the cells blue to the naked eye [51]. We also found a gene cluster carrying the operon cusCBA that codes for a tripartite RND efflux system. In other bacterial models, such as Pseudomonas syringae or Escherichia coli, the orthologous Cus efflux system was shown to specifically extrude reduced monovalent copper and silver ions [52, 53]. Altogether, these genetic elements could be responsible for the observed copper resistance of AU10. When compared to other Pseudomonas strains, AU10 exhibited (Table 1) twice the MIC reported for Cu(II) in planktonic cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and fell within the MIC range reported for Antarctic Pseudomonas [30, 54]. AU10 contains another efflux pump from the RND family encoded in the czcDCBA operon (cluster 10 from Fig. 1a). This pump is known to extrude divalent metals like cadmium, zinc, and cobalt [53], and could account for AU10’s resistance to Mn(II) and Fe(II) (Table 1). Both copA and czcA genes were previously found to be quite prevalent in a collection of 200 bacteria resistant to heavy metals from Antarctic soils, even from sites with limited human influence [12].

Fig. 1.

Heavy metal and metalloid resistome of Pseudomonas sp. AU10. A All gene clusters involved in resistance and homeostasis to metal(loid)s are shown, with genes encoding efflux system components in green, those encoding metal transforming enzymes in red, those encoding metal-sequestering proteins in yellow, metal(loid) response regulator genes in light-blue, metal sensor histidine kinase genes from two-component systems in blue, metal resistance genes of uncharacterized function in pink, and non-related genes in grey. HP stands for hypothetical protein. The names of the encoded proteins are placed next to the corresponding genes, and comprehensive information about the function of each gene cluster is also included. B Growth profile of AU10 when grown with different concentrations of chromium (VI)

Regarding toxic derivatives of metalloids, such as arsenate (AsO43−) and tellurite (TeO32−), we found the arsRBC and the terZABCDE operons in AU10’s genome (clusters 2 and 3 from Fig. 1a). The ars genes encode an arsenate reductase (arsC), an efflux pump for the extrusion of the reduced arsenite (arsB), and the cognate regulator (arsR). This mechanism of arsenate transformation and later efflux probably accounts for the arsenate resistance of AU10 (MIC of 200 mM). A homologous arsRBC operon was identified in P. aeruginosa but with a significantly lower MIC of approximately 10 mM [55]. Other Pseudomonas strains with higher MIC values for As(V) carried more gene clusters involved in arsenic resistance. For example, the Antarctic Pseudomonas sp. MPC6 showed one of the highest recorded MICs (350 mM) and presented in its genome several gene clusters, including aioBA, arsC, arsH and arsAB [30]. In contrast, Pseudomonas putida KT2440 (MIC of 250 mM) presented two different operons in its chromosome, ars1 and ars2 [56]. On the other hand, AU10 showed a low tellurite MIC (70 μM) that most closely resembles that reported for non-resistant Pseudomonas [57]. This is surprising since the terZABCDE operon was recognized among all possible genetic determinants of tellurium resistance as the one conferring the highest resistance levels (MIC of ~4 mM), being carried frequently in transferable plasmids [57–59]. It is possible that AU10’s ter operon was not induced by the presence of the metalloid. In fact, the specific functions of the ter genes in tellurium resistance are still obscure, but were reported to participate in resistance to bacteriophages, phagocytosis, oxidative stress, and colicins [59]. Thus, the ter operon from AU10 might be silent in the conditions assayed or might be involved in the response to other stressors present in the Antarctic environment. Nevertheless, the appearance of a black sediment in AU10 cultures with tellurite concentrations near the observed MIC indicated an actual tellurite reduction to elemental tellurium (Te0), as previously reported [58].

Among the heavy metals for which AU10 was found to be resistant, we focused on Cr(VI). This oxidizing and highly toxic metal appears in natural ecosystems mainly due to anthropic activities, while the other metal(loid)s tested frequently originate from rock weathering processes or volcanic emissions [12, 60]. AU10’s MIC for chromium (Table 1) was in the range reported for other Cr(VI)-resistant Pseudomonas strains from different origins [61]. To determine the effect of Cr(VI) on AU10’s growth, we performed growth curves with different concentrations of Cr(VI), showing that sublethal levels of the metal (50 ppm) still cause growth retardation (Fig. 1b). In AU10’s genome, we found a gene annotated by RAST as a chromate reductase (Fig. 1a). These enzymes are known to catalyze the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III), leading to resistance [60]. The amino acid sequence of AU10’s chromate reductase (GenBank: WP_094953785) exhibited 46% and 39% identity to the well-studied chromate reductases of Gluconacetobacter hansenii ATCC 23769 and E. coli BL21, respectively [62, 63]. Additionally, to investigate other potential mechanisms of chromium resistance, we examined AU10’s exopolysaccharides (EPS) for their ability to sorb Cr(VI). By purifying AU10’s EPS and exposing it to Cr(VI) for an hour, we found a significant adsorption capacity of 25 ± 5 μg Cr(VI)/mg of EPS, with a 46% removal ability. This sorption capacity was three times higher than that observed for the EPS of Stenotrophomonas sp. JD1, a Cr(VI)-resistant bacterium previously studied by our group [34]. Moreover, the percentage of Cr(VI) removed by AU10’s EPS nearly doubles that reported for P. aeruginosa MTCC 1688 [64]. We investigared the sugar composition of AU10’s EPS, which showed a 1:4 ratio of glucose to mannose/galactose (with similar retention time), but xylose, fructose, and arabinose were not detected. A Cr(VI)-biosorbent EPS in AU10 shows the presence of other resistance mechanisms that cannot be inferred solely from its resistome. This polysaccharide would add another layer of protection to the already renowned impermeable outer membrane of Pseudomonas [65]. Therefore, changes in the produced EPS profile, which depend on the physiological state and the response to environmental stress, could increase the resistance levels of AU10 to chromium and possibly to other toxic compounds present in its environment, including other metals and antibiotics. Overall, with its metal(loid) resistance profile and all the displayed mechanisms of resistance, AU10 could be considered a potential candidate to participate in the bioremediation of contaminated Antarctic habitats.

With regard to the antibiotic resistance profile of AU10, we analyzed 22 antibiotics using different methods, including disc diffusion and MIC determination with E-tests and an automated system (Sensititre). When studying non-clinical bacteria of environmental origin, such as AU10, a concerning issue is the absence of internationally accepted breakpoints to define susceptibility and resistance [1]. Here, we adopted a conservative criterion for the interpretation of disc diffusion results, which was previously employed for studying Antarctic bacteria [10]. In addition, we used the CLSI breakpoints for MIC interpretation (see “Materials and methods”). With these criteria, the results for AU10 are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance/susceptibility profile of Pseudomonas sp. AU10

| Method | Resistant to: | Susceptible to: |

|---|---|---|

| Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion methoda | Amoxicillin-clavulanate, ampicillin-sulbactam, azithromycin, aztreonam, cefotaxime | Amikacin (30 mm), cefepime (25 mm), ceftazidime (18 mm), chloramphenicol (17 mm), ciprofloxacin (29 mm), gentamicin (25mm), imipenem (19 mm), nalidixic acid (16 mm), meropenem (24 mm), piperacillin-tazobactam (22 mm), streptomycin (36 mm), tetracycline (28 mm) |

| MIC with E-test method | Azythromycin (64 μg/mL)c | Ceftazidime (2 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (16 μg/mL)b, imipenem (4 μg/mL), meropenem (4 μg/mL), tetracycline (1 μg/mL) |

| MIC with the Sensititre automated system | Ampicillin (> 16 μg/mL)c, amoxicillin-clavulanate (> 16 μg/mL)c, ampicillin-sulbactam (> 16 μg/mL)c, aztreonam (> 16 μg/mL), cefotaxime (> 32 μg/mL) | Amikacin (≤ 8 μg/mL), cefepime (4 μg/mL), ceftazidime (4 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (16 μg/mL)b, ciprofloxacin (0.12 μg/mL), colistin (≤ 1 μg/mL)c, gentamicin (≤ 4 μg/mL), imipenem (4 μg/mL), levofloxacin (0.25 μg/mL), meropenem (8 μg/mL)b, minocycline (≤ 4 μg/mL), piperacillin-tazobactam (≤ 8 μg/mL), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (≤ 2 μg/mL) |

MIC stands for minimum inhibitory concentration

aMeasures of disk inhibition zone diameters are presented in parentheses

bIntermediate resistance according to CLSI cut-off points

cWithout specified breakpoints in the “other non-Enterobacterales” CLSI table

AU10 was resistant to different β-lactams, including penicillin and aminopenicillins in combination with inhibitors of β-lactamases, to a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime) and monobactams (aztreonam) (Table 2). It was also resistant to a macrolide (azithromycin) and showed intermediate resistance to chloramphenicol. In contrast, it showed susceptibility to aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, colistin, synthetic antibiotics (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), and conventional antipseudomonal β-lactams, such as third and fourth generation cephalosporins (ceftazidime and cefepime), piperacillin-tazobactam, and carbapenems (imipenem and meropenem). These β-lactams are commonly prescribed for the empiric treatment of P. aeruginosa infections [22]. In the case of carbapenems, some of the MIC results showed intermediate resistance levels (Table 2), leading to a potential ambiguity in their interpretation. The dissemination of carbapenem resistance in clinical Pseudomonas is considered an imminent health concern by the World Health Organization due to the ongoing resistance crisis [22]. Hence, we conducted a more detailed analysis for AU10. In the synergy assay, where specific β-lactam disks were placed in an orderly manner, we did not observe any alterations of inhibition zones (synergy effects). Thus, AU10 did not show the ability to produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases and metallo-β-lactamases. In addition, no carbapenemases were revealed by performing the Blue-Carba method [38]. The lack of all these enzymes was verified by analyzing AU10’s genome.

As we did for metal(loid)s, we searched for the antibiotic resistome in AU10’s genome and found 12 gene clusters (Fig. 2). Most of the clusters encoded multi-drug efflux systems of the RND and ABC families: MexAB-OprM, MexEF-OprN, MexJK-OprM, MdtABC-OMF-TolC, EmrAB-OMF-TolC, TriABC-OpmH, and MacA/MacB (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the strain presented a few genes involved in enzymatic targeting of antibiotics: two encoding aminoglycoside O-phosphotransferases (aph(3′)-IIb and a putative aph(6)-I), and an ampC gene encoding a wide-spectrum class C β-lactamase. The presence of aminoglycoside targeting enzymes did not relate to a resistance phenotype toward the tested antibiotics from this class (Table 2). Hächler et al. showed that the APH(3′)-IIb of P. aeruginosa confers resistance to aminoglycosides like kanamycin, neomycin, butirosin, and seldomycin, which were not tested here [66]. In contrast, APH(6)-I was reported to target streptomycin, an antibiotic to which AU10 was susceptible (Table 2) [67]. On the other hand, the ampC gene might be the main determinant of AU10’s β-lactam resistance profile. This gene is usually found in the human pathogen P. aeruginosa, but also in environmental fluorescent Pseudomonas, always in the chromosome and neighbored by its cognate regulatory gene ampR [20, 21], as we found in AU10’s genome (Fig. 2). In P. aeruginosa, AmpC is the major cause of resistance to aminopenicillins, to first- and second-generation cephalosporins, and even to ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, and piperacillin when derepressed by mutation, but never to carbapenems [68, 69]. The MexAB efflux pump present in AU10’s genome could be involved in β-lactam resistance, reinforcing the effect of AmpC [70]. MexAB and MexEF were also implicated in the extrusion of chloramphenicol, which might explain the observed intermediate resistance to this antibiotic [71]. Likewise, AU10’s resistance to azithromycin could be attributed to the presence of MexJK and MacAB efflux systems, as both systems were shown to extrude erythromycin, another macrolide [72, 73]. In fact, erythromycin and azithromycin are among the most common antibiotic contaminants found in water samples from King George Island [8].

Fig. 2.

Antibiotic resistome from Pseudomonas sp. AU10. Different gene clusters are shown, with genes encoding efflux systems in green, those involved in enzymatic transformation of antibiotics in red, those encoding regulatory systems in light-blue, and non-related genes in grey. The names of the encoded proteins are placed next to the corresponding genes and the name of the entire system is also presented

All the antibiotic resistance gene clusters from AU10 were located in a chromosomal context, and none was flanked by mobile genetic elements, such as insertion sequences, transposons, or recombinases. In fact, the plasmid from AU10 had no genes involved in resistance to antibiotics (or heavy metals). Hence, the adaptive advantage that this plasmid confers to AU10 remains to be determined. In addition, we did not find integrons when searching for elements from the stable region, such as the intI gene.

Regarding prophages, a recent metagenomic study of Antarctic soils found that acquired resistance genes were mainly associated with this kind of mobile genetic elements [14]. Therefore, we inspected AU10’s genome and found six prophages, with sizes ranging from 8 to 44 kb. All were homologous to different Pseudomonas phages, with different levels of similarity and query cover. However, only one of them was recognized as a complete prophage, being highly similar to the temperate one called Dobby (from the φCTX type and P2 group), identified in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [74]. Notably, none of AU10’s prophages contained antibiotic or heavy metal resistance genes, nor cytotoxin genes.

Taking these results in consideration, we think that all AU10’s antibiotic resistances would come from intrinsic features vertically acquired. Both AmpC and most of the antibiotic efflux systems present in AU10 are generally considered intrinsic for the genus Pseudomonas [20, 21]. These natural resistances were proposed to be maintained over generations through intense amensalistic interactions occurring in pristine Antarctic habitats [1, 10]. In fact, the authors of a metagenomic study performed in remote and pristine Antarctic soils did not find any mobile genetic elements carrying antibiotic resistance genes [13]. This is in contrast to other surveys carried out in sites with great human impact, where acquired genes, like those encoding plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases and extended-spectrum β-lactamases, were found to be most abundant with PCR strategies [4, 19].

The absence of acquired resistance mechanisms in AU10, which is indicative of the preserved nature of its original habitat, caught our attention since the Uruguay Lake has some level of human impact. The lake has a water pump that feeds the Artigas Scientific base with fresh water and is subject to human transit in its surroundings [25]. However, it is free from untreated wastewater discharges, which are considered the main contaminating human activity concerning antibiotics and antibiotic-resistance genes [1, 75]. This lake was also found to be unpolluted with respect to heavy metals when sites with varying degrees of human impact were evaluated [76]. All this adds to its preserved nature.

For a good monitoring program of anthropogenic impact based on following metal(loid) and antibiotic resistance, it is clear that the resistome must be studied in some way to differentiate between natural and acquired resistance mechanisms. Although PCR strategies are very useful when large collections of bacteria are analyzed, they have drawbacks with respect to gene selection and primer design. On the other hand, culture-independent strategies lack the phenotypic match necessary to fully understand the evolution of resistance caused by human influence. For this reason, the wealth of sequenced genomes obtained from Antarctic cultured strains should be used to better link the resistome genetic elements to the resistance profiles determined in-bench, as we did here for AU10. This could help refine PCR-based surveillance studies [19].

Moreover, these analyses could be even more valuable if conducted for dominant components of Antarctic communities, particularly those that can readily acquire mobile genetic elements, such as Pseudomonas species. Most works cited here reported results from collections of Antarctic strains in which Pseudomonas species were overrepresented [4, 7, 10–12]. Indeed, a metagenomic study conducted on Deception Island soils revealed that Pseudomonas was the most abundant genus carrying resistance genes. Consequently, it was suggested as a key taxon for studying metal and antibiotic resistances [14]. In addition, as mentioned previously, our group also followed for 5 years the abundant populations of Pseudomonas species from different freshwater environments as a proxy for anthropogenic impact [25]. Therefore, the results presented here, together with the antibiotic and heavy metal resistome analyses performed for other Antarctic Pseudomonas, could serve as the groundwork for establishing monitoring programs and standards that would improve the use of these abundant bacteria as bioindicators of human impact in Antarctic ecosystems.

Conclusions

Overall, the Antarctic strain Pseudomonas sp. AU10 could be considered to be resistant to most of the heavy metals and metalloids tested, including Cr(VI), Cu(II), Mn(II), Fe(II), and As(V). However, it exhibited resistance only to a subset of the tested antibiotics, such as aminopenicillins, cefotaxime, aztreonam, azithromycin, and intermediate resistance to chloramphenicol. The genome analysis allowed us to correlate this co-resistant phenotype with a resistome that encoded mostly efflux systems, although some enzymes and sequestering proteins were also found. Most of the pumps had clear homology to Pseudomonas systems of known specificity towards either antibiotics or heavy metals. Still, the actual specificity of these pumps in Antarctic environmental Pseudomonas remains to be determined. Other genetic elements, such as the ter operon, did not confer the expected phenotype, highlighting the importance of not jumping to conclusions when analyzing the resistome alone. AU10’s resistome showed no indication of horizontal acquisition, except possibly for only one gene cluster involved in copper resistance. This could be considered indicative of the preserved nature of AU10’s habitat. By correlating the resistance profile with the resistome for this strain, we are contributing to refining surveillance strategies based on monitoring Pseudomonas resistance phenotypes and genotypes from Antarctic freshwater environments exposed to different human impacts.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Instituto Antártico Uruguayo (IAU) for the logistic support during the stay in the Antarctic Artigas Base. CXGL, MAM and SCS are members of the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (SNI) from the Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (ANII, Uruguay). This work was partially supported by the Programa de Desarrollo de las Ciencias Básicas (PEDECIBA, Uruguay) and the Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica (CSIC) from the Universidad de la República (UdelaR, Uruguay), project C335-348 (Iniciación a la investigación). The work of CXGL was supported by the Comisión Académica de Posgrado (CAP, UdelaR) and ANII.

Author contribution

CXGL performed the genomic analyses. CXGL and MAM performed the heavy metals experiments. GGG determined the resistance to antibiotics. CXGL and SCS were involved in the experimental design and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

All authors approved the manuscript.

Consent for publication

The authors consented for the publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hwengwere K, Paramel Nair H, Hughes KA, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Antarctica: is it still a pristine environment? Microbiome. 2022;10:71. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01250-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martínez-Rosales C, Fullana N, Musto H, Castro-Sowinski S. Antarctic DNA moving forward: genomic plasticity and biotechnological potential. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;331:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo Giudice A, Caruso G, Rizzo C, et al. Bacterial communities versus anthropogenic disturbances in the Antarctic coastal marine environment. Environ Sustain. 2019;2:297–310. doi: 10.1007/s42398-019-00064-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jara D, Bello-Toledo H, Domínguez M, et al. Antibiotic resistance in bacterial isolates from freshwater samples in Fildes Peninsula, King George Island. Antarctica. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3145. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Souza MJ, Nair S, Loka Bharathi PA, Chandramohan D. Metal and antibiotic-resistance in psychrotrophic bacteria from Antarctic marine waters. Ecotoxicology. 2006;15:379–384. doi: 10.1007/s10646-006-0068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller RV, Gammon K, Day MJ. Antibiotic resistance among bacteria isolated from seawater and penguin fecal samples collected near Palmer Station, Antarctica. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55:37–45. doi: 10.1139/W08-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomova I, Stoilova-Disheva M, Lazarkevich I, Vasileva-Tonkova E. Antimicrobial activity and resistance to heavy metals and antibiotics of heterotrophic bacteria isolated from sediment and soil samples collected from two Antarctic islands. Front Life Sci. 2015;8:348–357. doi: 10.1080/21553769.2015.1044130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernández F, Calısto-Ulloa N, Gómez-Fuentes C, et al. Occurrence of antibiotics and bacterial resistance in wastewater and sea water from the Antarctic. J Hazard Mater. 2019;363:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabbia V, Bello-Toledo H, Jiménez S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli strains isolated from Antarctic bird feces, water from inside a wastewater treatment plant, and seawater samples collected in the Antarctic Treaty area. Polar Sci. 2016;10:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.polar.2016.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tam HK, Wong CMVL, Yong ST, et al. Multiple-antibiotic-resistant bacteria from the maritime Antarctic. Polar Biol. 2015;38:1129–1141. doi: 10.1007/s00300-015-1671-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Aravena M, Urtubia R, Del Campo K, et al. Antibiotic and metal resistance of cultivable bacteria in the Antarctic sea urchin. Antarct Sci. 2016;28:261–268. doi: 10.1017/S0954102016000109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romaniuk K, Ciok A, Decewicz P, et al. Insight into heavy metal resistome of soil psychrotolerant bacteria originating from King George Island (Antarctica) Polar Biol. 2018;41:1319–1333. doi: 10.1007/s00300-018-2287-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Goethem MW, Pierneef R, Bezuidt OKI et al (2018) A reservoir of “historical” antibiotic resistance genes in remote pristine Antarctic soils. Microbiome 6. 10.1186/s40168-018-0424-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Santos A, Burgos F, Martinez-Urtaza J, Barrientos L (2022) Metagenomic characterization of resistance genes in deception island and their association with mobile genetic elements. Microorganisms 10. 10.3390/microorganisms10071432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Antelo V, Guerout AM, Mazel D, et al. Bacteria from Fildes Peninsula carry class 1 integrons and antibiotic resistance genes in conjugative plasmids. Antarct Sci. 2018;30:22–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954102017000414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antelo V, Giménez M, Azziz G et al (2021) Metagenomic strategies identify diverse integron-integrase and antibiotic resistance genes in the Antarctic environment. Microbiologyopen 10. 10.1002/mbo3.1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Marcoleta AE, Arros P, Varas MA et al (2022) The highly diverse Antarctic Peninsula soil microbiota as a source of novel resistance genes. Sci Total Environ 810. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Centurion VB, Silva JB, Duarte AWF et al (2022) Comparing resistome profiles from anthropogenically impacted and non-impacted areas of two South Shetland Islands – Maritime Antarctica. Environ Pollut 304. 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119219 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wang F, Stedtfeld RD, Kim OS, et al. Influence of soil characteristics and proximity to antarctic research stations on abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in soils. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:12621–12629. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b02863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira Silverio M, Kraychete GB, Rosado AS, Bonelli RR (2022) Pseudomonas fluorescens complex and its intrinsic, adaptive, and acquired antimicrobial resistance mechanisms in pristine and human-impacted sites. Antibiotics 11. 10.3390/antibiotics11080985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37:177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunz Coyne AJ, El Ghali A, Holger D, et al. Therapeutic strategies for emerging multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11:661–682. doi: 10.1007/s40121-022-00591-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fakhar A, Gul B, Gurmani AR, et al. Heavy metal remediation and resistance mechanism of Aeromonas, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas: a review. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2022;52:1868–1914. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2020.1863112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chellaiah ER. Cadmium (heavy metals) bioremediation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a minireview. Appl Water Sci. 2018;8:154. doi: 10.1007/s13201-018-0796-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morel MA, Braña V, Martínez-rosales C, et al. Five-year bio-monitoring of aquatic ecosystems near Artigas Antarctic Scientific Base, King George Island. Adv Polar Sci. 2015;26:102–106. doi: 10.13679/j.advps.2015.1.00102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martínez-Rosales C, Castro-Sowinski S. Antarctic bacterial isolates that produce cold-active extracellular proteases at low temperature but are active and stable at high temperature. Polar Res. 2011;30:7123. doi: 10.3402/polar.v30i0.7123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fullana N, Braña V, José Marizcurrena J, et al. Identification, recombinant production and partial biochemical characterization of an extracellular cold-active serine-metalloprotease from an Antarctic Pseudomonas isolate. AIMS Bioeng. 2017;4:386–401. doi: 10.3934/bioeng.2017.3.386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.García-Laviña CX, Castro-Sowinski S, Ramón A. Reference genes for real-time RT-PCR expression studies in an Antarctic Pseudomonas exposed to different temperature conditions. Extremophiles. 2019;23:625–633. doi: 10.1007/s00792-019-01109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cagide C, Marizcurrena JJ, Vallés D et al (2023) A bacterial cold-active dye-decolorizing peroxidase from an Antarctic Pseudomonas strain. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 10.1007/s00253-023-12405-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Orellana-Saez M, Pacheco N, Costa JI et al (2019) In-depth genomic and phenotypic characterization of the antarctic psychrotolerant strain Pseudomonas sp. MPC6 reveals unique metabolic features, plasticity, and biotechnological potential. Front Microbiol 10. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Dziewit L, Pyzik A, Matlakowska R et al (2013) Characterization of Halomonas sp. ZM3 isolated from the Zelazny Most post-flotation waste reservoir, with a special focus on its mobile DNA. BMC Microbiol 13. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Del Gallo M, Haegi A. Characterization and quantification of exocellular polysaccharides in Azospirillum brasilense and Azospirillum lipoferum. Symbiosis. 1990;9:155–161. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dische Z. Methods in carbohydrate chemistry. Academic Press; 1962. General color reactions; pp. 477–512. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morel MA, Ubalde MC, Olivera-Bravo S, et al. Cellular and biochemical response to Cr(VI) in Stenotrophomonas sp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;291:162–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bahat-Samet E, Castro-Sowinski S, Okon Y. Arabinose content of extracellular polysaccharide plays a role in cell aggregation of Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;237:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CLSI (2022) Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 32rd ed. CLSI (USA) Supplement M100. Clin Lab Stand Inst. https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/

- 37.Piersigilli AL, Enrico MC, Bongiovanni ME, et al. Aislados clínicos de Pseudomonas aeruginosa productores de β-lactamasa de espectro extendido en un centro privado de Córdoba. Rev Chil Infectol. 2009;26:331–335. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182009000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasteran F, Veliz O, Ceriana P, et al. Evaluation of the Blue-Carba test for rapid detection of carbapenemases in gram-negative Bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1996–1998. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03026-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olson RD, Assaf R, Brettin T, et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): a resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D678–D689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonopoulos DA, Assaf R, Aziz RK, et al. PATRIC as a unique resource for studying antimicrobial resistance. Brief Bioinform. 2018;20:1094–1102. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alcock Brian P, Raphenya Amogelang R, Lau Tammy TY, et al. CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D517–D525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, ..., Zagnitko O (2008) The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9(1):1–15. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S et al (2007) KAAS: An automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res 35. 10.1093/nar/gkm321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, et al. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D457–D462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akhter S, Aziz RK, Edwards RA (2012) PhiSpy: a novel algorithm for finding prophages in bacterial genomes that combines similarity-and composition-based strategies. Nucleic Acids Res 40. 10.1093/nar/gks406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Arndt D, Grant JR, Marcu A, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W16–W21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L et al (2006) ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 34. 10.1093/nar/gkj014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Ross K, Varani AM, Snesrud E et al (2021) TnCentral: a prokaryotic transposable element database and web portal for transposon analysis. MBio 12. 10.1128/mBio.02060-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Granja-Travez RS, Bugg TDH. Characterization of multicopper oxidase CopA from Pseudomonas putida KT2440 and Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5: involvement in bacterial lignin oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;660:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cha JS, Cooksey DA. Copper resistance in Pseudomonas syringae mediated by periplasmic and outer membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8915–8919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bondarczuk K, Piotrowska-Seget Z. Molecular basis of active copper resistance mechanisms in Gram-negative bacteria. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2013;29:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s10565-013-9262-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franke S, Grass G, Rensing C, Nies DH. Molecular analysis of the copper-transporting efflux system CusCFBA of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3804–3812. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.13.3804-3812.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gutiérrez-Barranquero JA, de Vicente A, Carrión VJ, et al. Recruitment and rearrangement of three different genetic determinants into a conjugative plasmid increase copper resistance in Pseudomonas syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1028–1033. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02644-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teitzel GM, Parsek MR. Heavy metal resistance of biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:2313–2320. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.2313-2320.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai J, Salmon K, DuBow MS. A chromosomal ars operon homologue of Pseudomonas aeruginosa confers increased resistance to arsenic and antimony in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1998;144:2705–2713. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernández M, Udaondo Z, Niqui JL, et al. Synergic role of the two ars operons in arsenic tolerance in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2014;6:483–489. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Summers AO, Jacoby GA. Plasmid determined resistance to tellurium compounds. J Bacteriol. 1977;129:276–281. doi: 10.1128/jb.129.1.276-281.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taylor DE. Bacterial tellurite resistance. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:111–115. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng W, Wang Y, Fu Y et al (2022) Characterization of the tellurite-resistance properties and identification of the core function genes for tellurite resistance in Pseudomonas citronellolis sjte-3. Microorganisms 10. 10.3390/microorganisms10010095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Viti C, Marchi E, Decorosi F, Giovannetti L. Molecular mechanisms of Cr(VI) resistance in bacteria and fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:633–659. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Narayani M, Shetty KV. Chromium-resistant bacteria and their environmental condition for hexavalent chromium removal: a review. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2013;43:955–1009. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2011.627022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eswaramoorthy S, Poulain S, Hienerwadel R et al (2012) Crystal structure of ChrR-A quinone reductase with the capacity to reduce chromate. PLoS One 7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Jin H, Zhang Y, Buchko GW et al (2012) Structure determination and functional analysis of a chromate reductase from Gluconacetobacter hansenii. PLoS One 7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Chug R, Mathur S, Kothari SL et al (2021) Maximizing EPS production from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its application in Cr and Ni sequestration. Biochem Biophys Rep 26. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.100972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Nikaido H, Hancock REW. The Biology of Pseudomonas. 1986. Outer membrane permeability of Pseudomonas aeruginosa; pp. 145–193. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hächler H, Santanam P, Kayser FH. Sequence and characterization of a novel chromosomal aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene, aph(3′)-IIb, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1254–1256. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME. Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat. 2010;13:151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:582–610. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berrazeg M, Jeannot K, Ntsogo Enguéné VY, et al. Mutations in β-lactamase AmpC increase resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates to antipseudomonal cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:6248–6255. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00825-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Masuda N, Sakagawa E, Ohya S, et al. Substrate specificities of MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3322–3327. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.12.3322-3327.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Köhler T, Michéa-Hamzehpour M, Henze U, et al. Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:345–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2281594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kobayashi N, Nishino K, Yamaguchi A. Novel macrolide-specific ABC-type efflux transporter in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5639–5644. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5639-5644.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chuanchuen R, Narasaki CT, Schweizer HP. The MexJK efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires OprM for antibiotic efflux but not for efflux of triclosan. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5036–5044. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.5036-5044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johnson G, Wolfe AJ, Putonti C (2019) Characterization of the φCTX-like Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage Dobby isolated from the kidney stone microbiota. Access Microbiol 1. 10.1099/acmi.0.000002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Szopińska M, Potapowicz J, Jankowska K et al (2022) Pharmaceuticals and other contaminants of emerging concern in Admiralty Bay as a result of untreated wastewater discharge: Status and possible environmental consequences. Sci Total Environ 835. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155400 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Bueno C, Kandratavicius N, Venturini N et al (2018) An evaluation of trace metal concentration in terrestrial and aquatic environments near Artigas Antarctic Scientific Base (King George Island, Maritime Antarctica). Water Air Soil Pollut 229. 10.1007/s11270-018-4045-1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.