Abstract

Ferguson, D. (1972).Brit. J. industr. Med.,29, 420-431. Some characteristics of repeated sickness absence. Several studies have shown that frequency of absence attributed to sickness is not distributed randomly but tends to follow the negative binomial distribution, and this has been taken to support the concept of `proneness' to such absence. Thus, the distribution of sickness absence resembles that of minor injury at work demonstrated over 50 years ago. Because the investigation of proneness to absence does not appear to have been reported by others in Australia, the opportunity was taken, during a wider study of health among telegraphists in a large communications undertaking, to analyse some characteristics of repeated sickness absence.

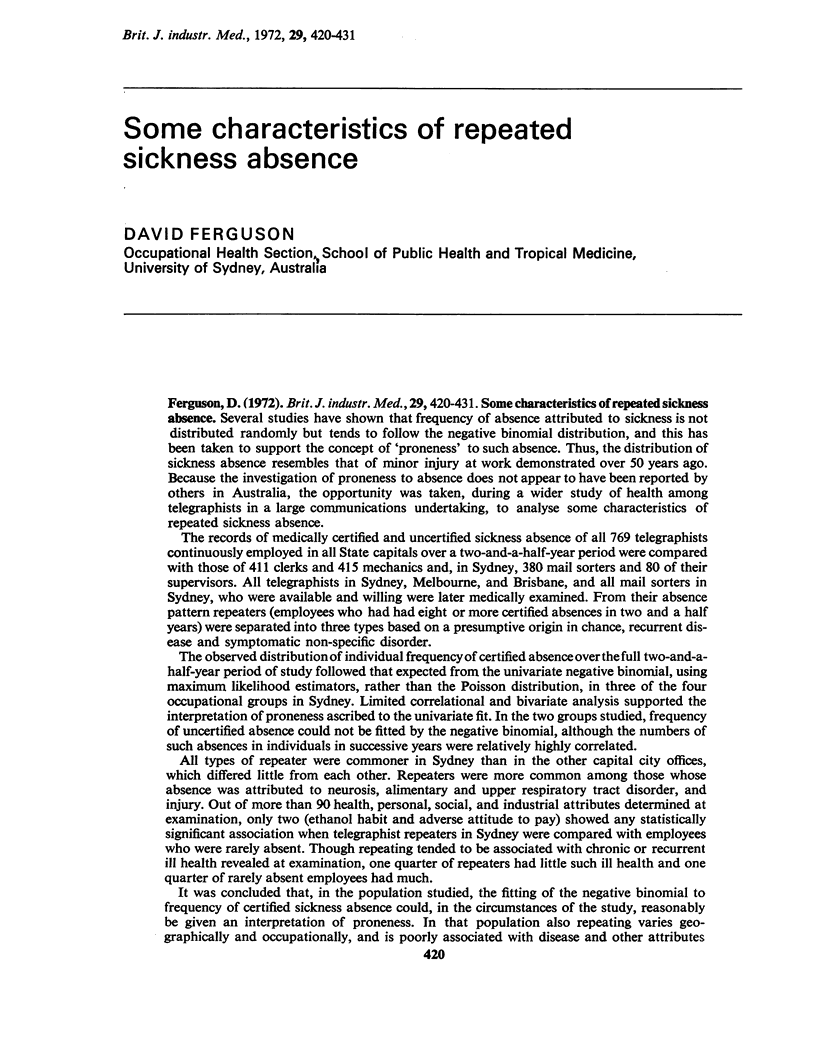

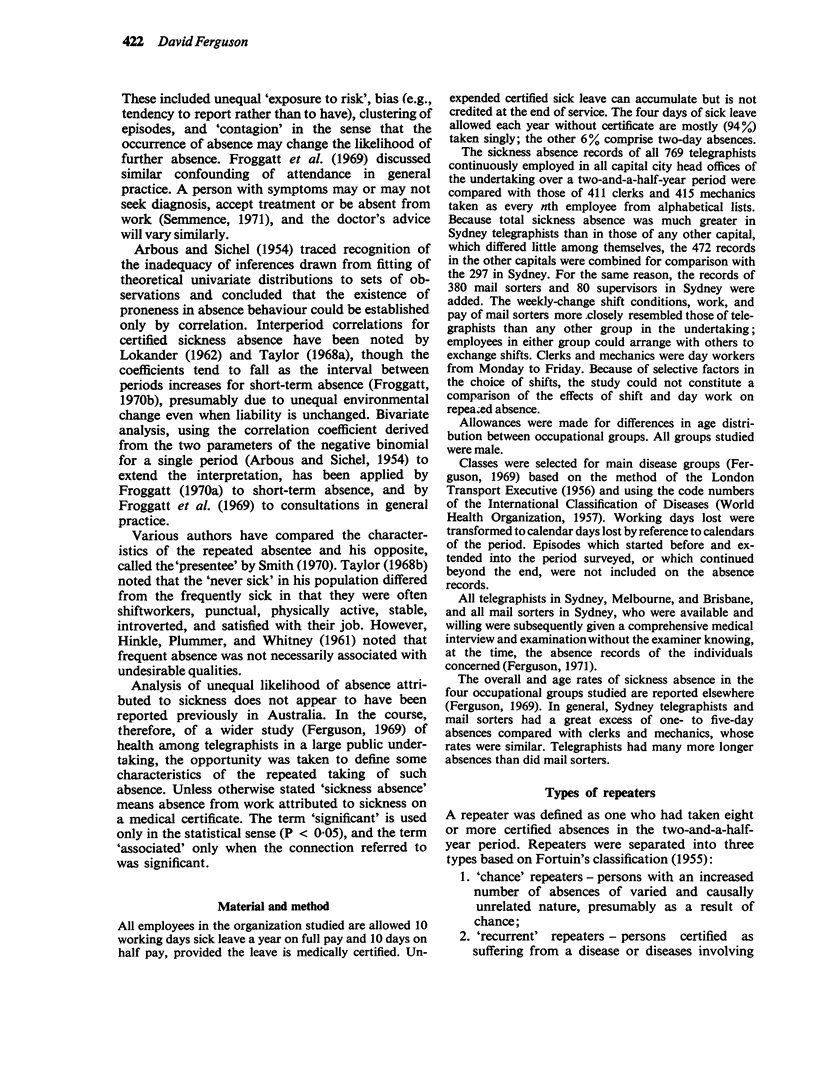

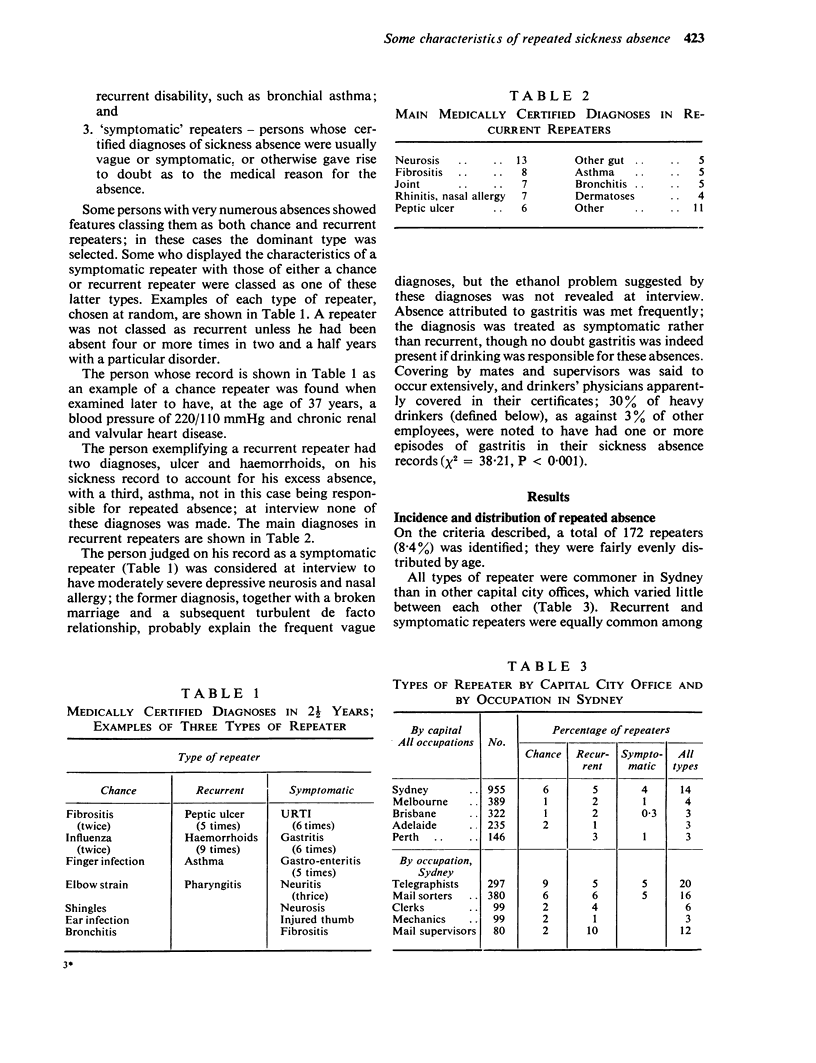

The records of medically certified and uncertified sickness absence of all 769 telegraphists continuously employed in all State capitals over a two-and-a-half-year period were compared with those of 411 clerks and 415 mechanics and, in Sydney, 380 mail sorters and 80 of their supervisors. All telegraphists in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, and all mail sorters in Sydney, who were available and willing were later medically examined. From their absence pattern repeaters (employees who had had eight or more certified absences in two and a half years) were separated into three types based on a presumptive origin in chance, recurrent disease and symptomatic non-specific disorder.

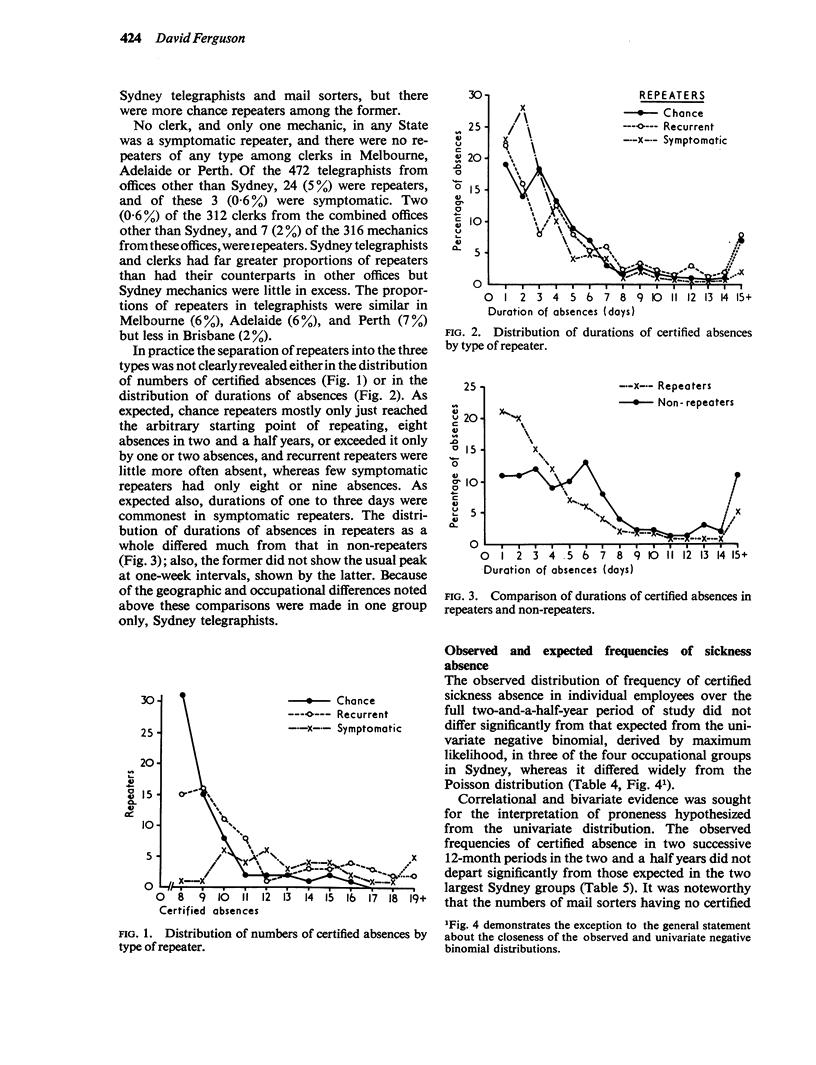

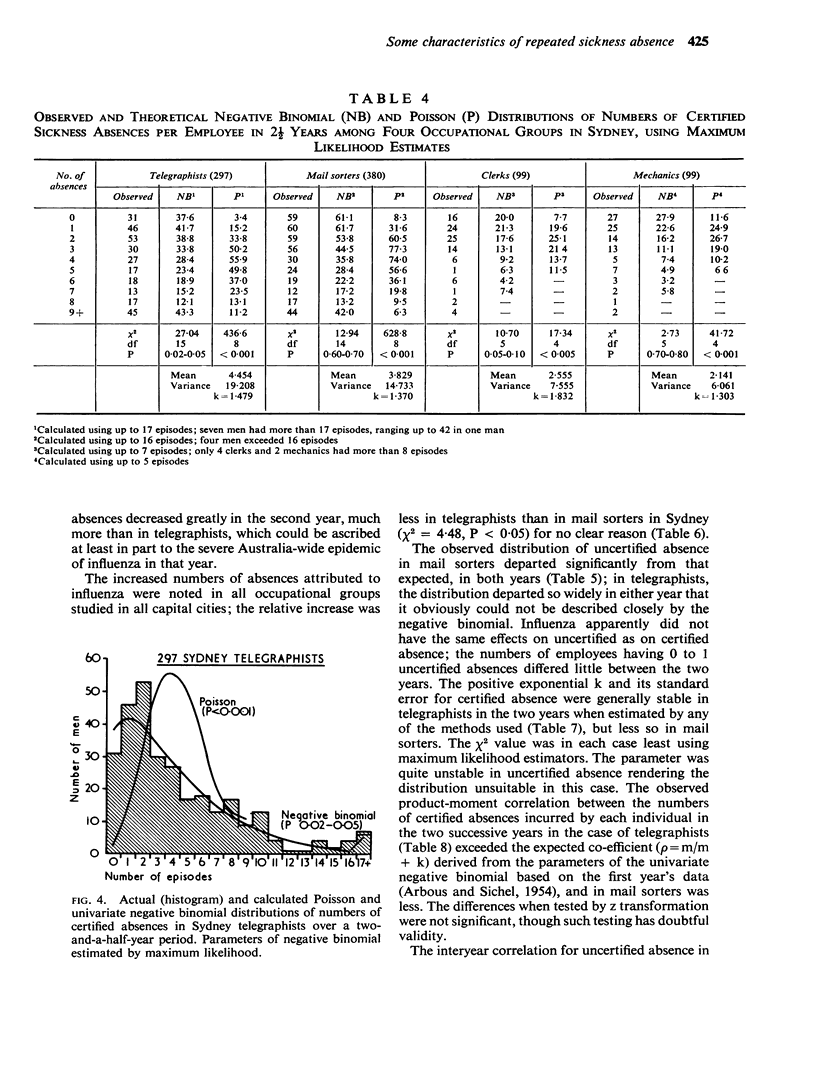

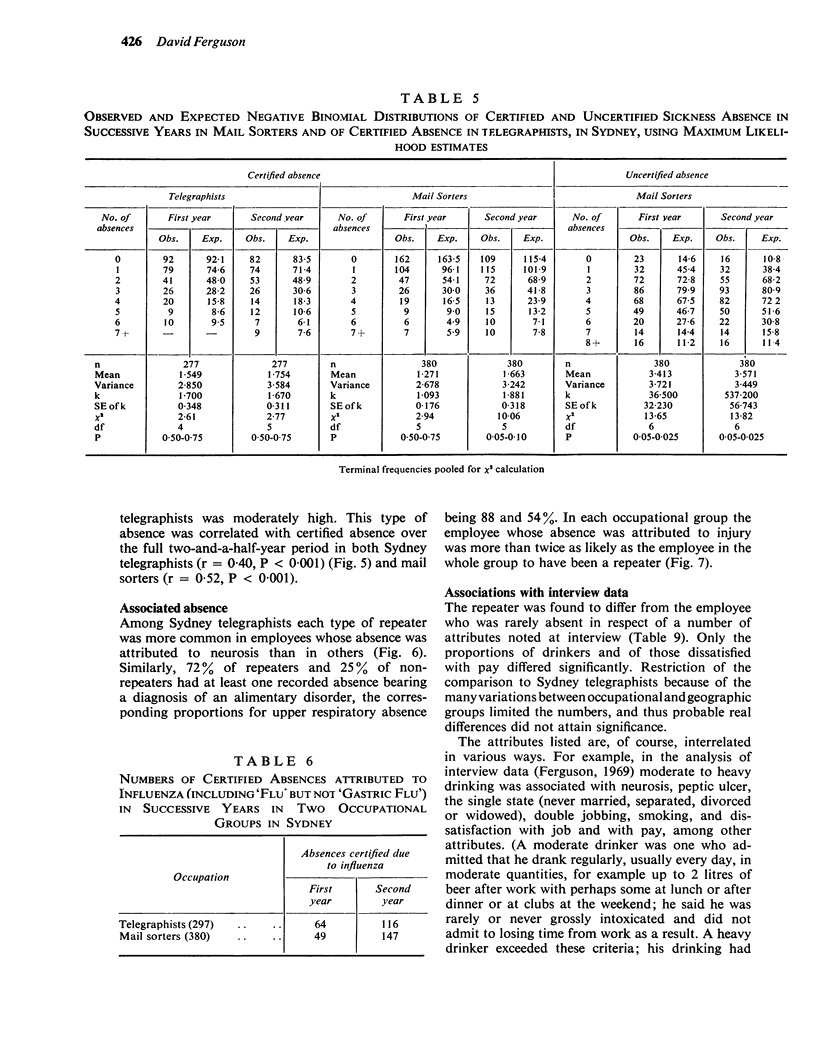

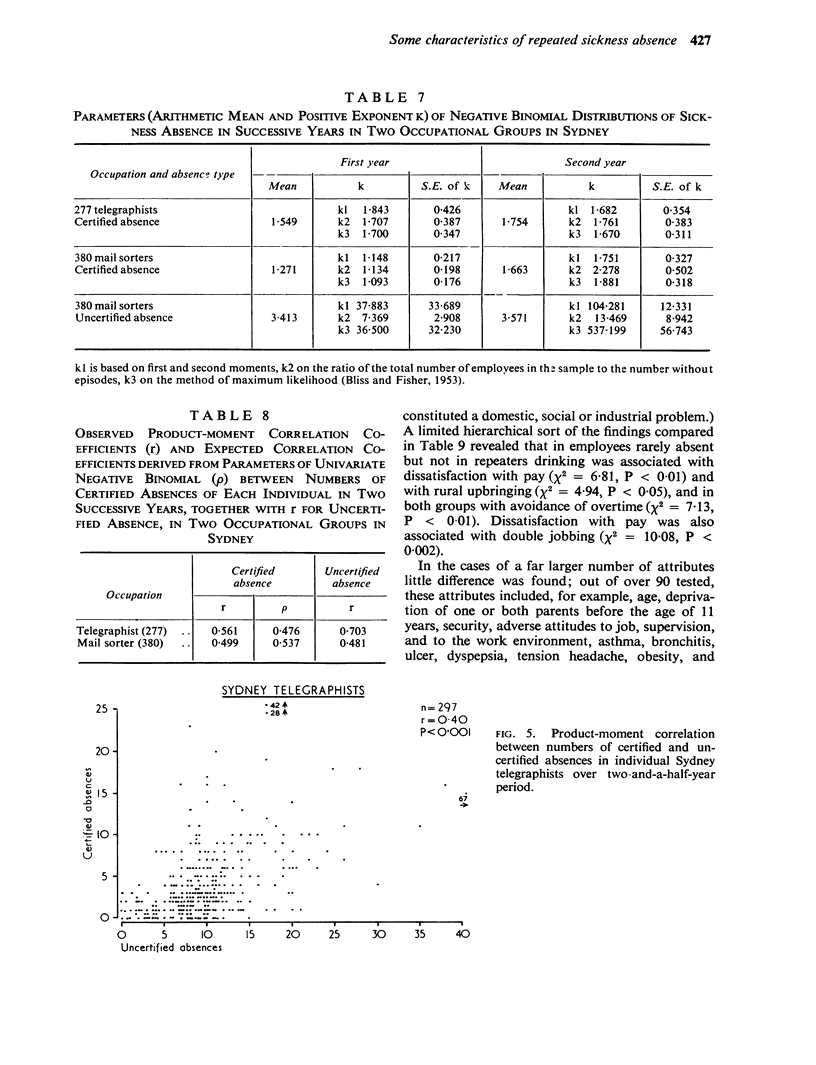

The observed distribution of individual frequency of certified absence over the full two-and-a-half-year period of study followed that expected from the univariate negative binomial, using maximum likelihood estimators, rather than the poisson distribution, in three of the four occupational groups in Sydney. Limited correlational and bivariate analysis supported the interpretation of proneness ascribed to the univariate fit. In the two groups studied, frequency of uncertified absence could not be fitted by the negative binomial, although the numbers of such absences in individuals in successive years were relatively highly correlated.

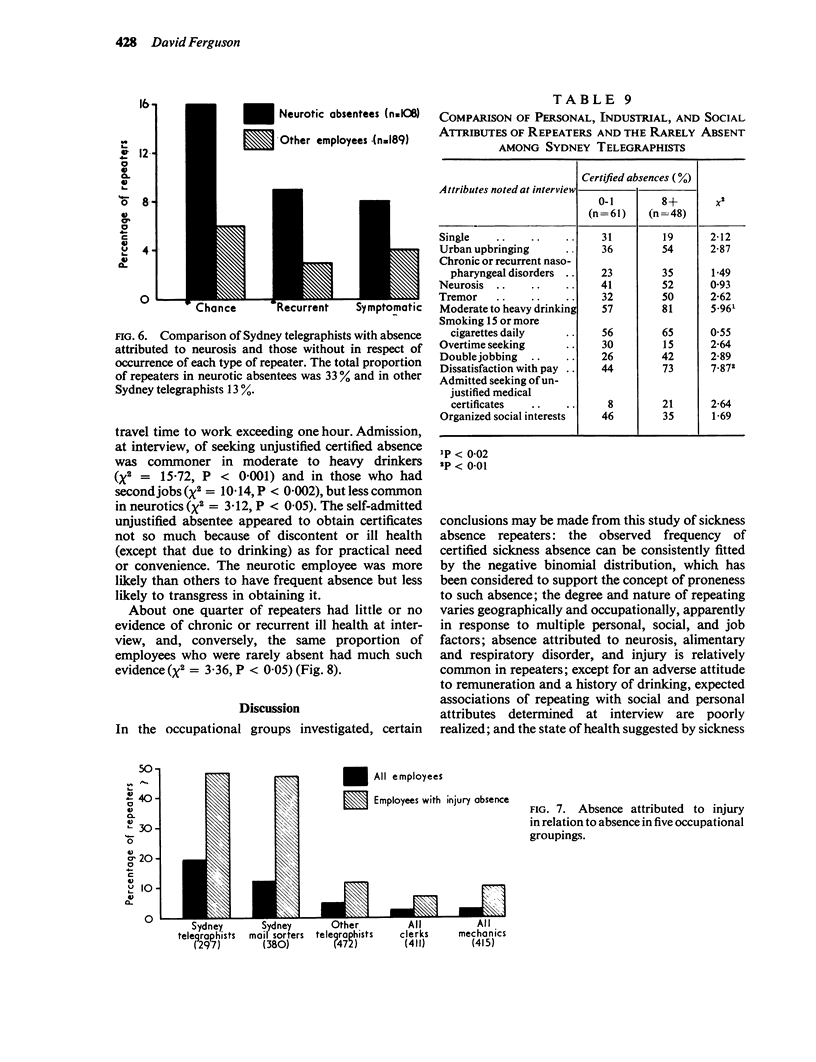

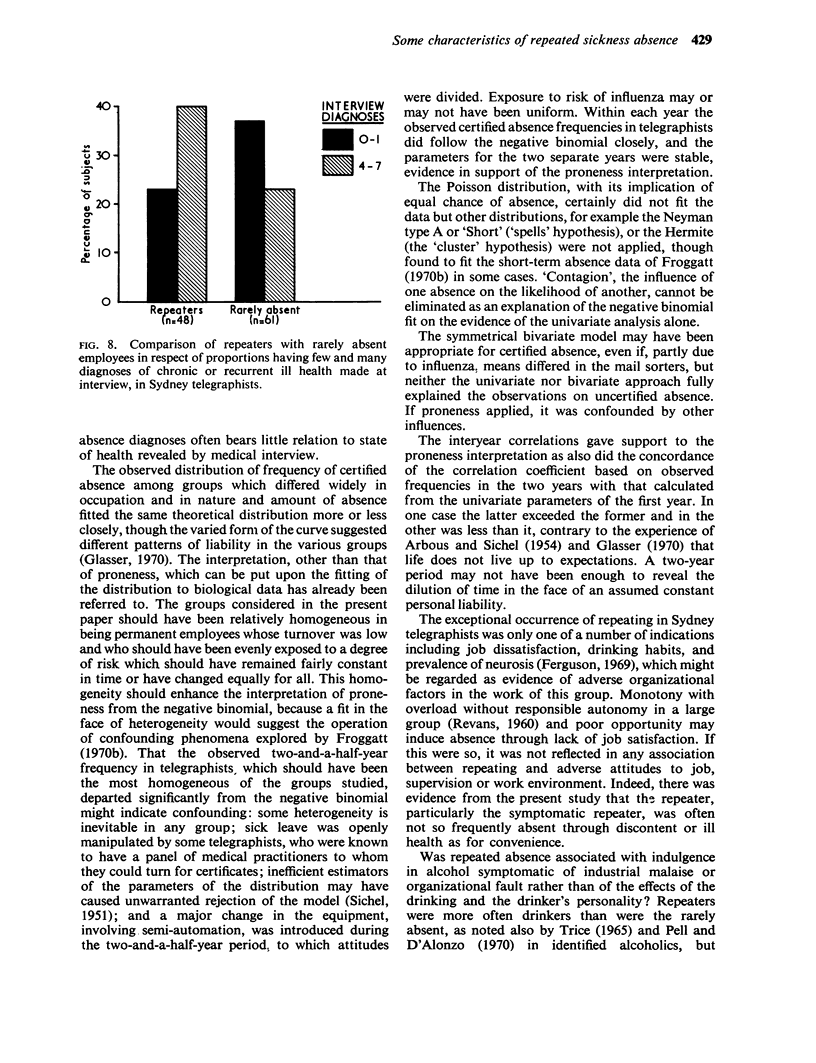

All types of repeater were commoner in Sydney than in the other capital city offices, which differed little from each other. Repeaters were more common among those whose absence was attributed to neurosis, alimentary and upper respiratory tract disorder, and injury. Out of more than 90 health, personal, social, and industrial attributes determined at examination, only two (ethanol habit and adverse attitude to pay) showed any statistically significant association when telegraphist repeaters in Sydney were compared with employees who were rarely absent. Though repeating tended to be associated with chronic or recurrent ill health revealed at examination, one quarter of repeaters had little such ill health and one quarter of rarely absent employees had much.

It was concluded that, in the population studied, the fitting of the negative binomial to frequency of certified sickness absence could, in the circumstances of the study, reasonably be given an interpretation of proneness. In that population also repeating varies geographically and occupationally, and is poorly associated with disease and other attributes uncovered at examination, with the exception of the ethanol habit. Repeaters are more often neurotic than employees who are rarely absent but also are more often stable double jobbers.

The repeater should be identified for what help may be given him, if needed, otherwise it would seem more profitable to attack those features in work design and organization which influence motivation to come to work. Social factors which predispose to repeated absence are less amenable to modification.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BLUMBERG M. S., COFFIN J. C. A syllabus on work absence. AMA Arch Ind Health. 1956 Jan;13(1):55–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROSS I. D., HINKLE L. E., Jr, PINSKY R. H., PLUMMER N. The distribution of sickness disability in a homogeneous group of healthy adult men. Am J Hyg. 1956 Sep;64(2):220–242. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIESMAN W. E. Absenteeism in industry. C. Clinical aspects of absenteeism. R Soc Health J. 1957 Oct;77(10):681–689. doi: 10.1177/146642405707701014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encel S., Kotowicz K. Heavy drinking and alcoholism. Preliminary report. Med J Aust. 1970 Mar 21;1(12):607–612. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1970.tb116944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORTUIN G. J. Sickness absenteeism. Bull World Health Organ. 1955;13(4):513–541. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FROGGATT P., SMILEY J. A. THE CONCEPT OF ACCIDENT PRONENESS: A REVIEW. Br J Ind Med. 1964 Jan;21:1–12. doi: 10.1136/oem.21.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froggatt P., Dudgeon M. Y., Merrett J. D. Consultations in general practice. Analysis of individual frequencies. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1969 Feb;23(1):1–11. doi: 10.1136/jech.23.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froggatt P. Short-term absence from industry. II. Temporal variation and inter-association with other recorded factors. Br J Ind Med. 1970 Jul;27(3):211–224. doi: 10.1136/oem.27.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser J. H. A stochastic model for industrial illness absenteeism. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1970 Oct;60(10):1936–1944. doi: 10.2105/ajph.60.10.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HINKLE L. E., Jr, PLUMMER N., WHITNEY L. H. The continuity of patterns of illness and the prediction of future health. J Occup Med. 1961 Sep;3:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell R. W., Crown S. Sickness absence levels and personality inventory scores. Br J Ind Med. 1971 Apr;28(2):126–130. doi: 10.1136/oem.28.2.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEMP R. The familiar face. Lancet. 1963 Jun 8;1(7293):1223–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)91859-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLUMMER N., HINKLE L. E., Jr Sickness absenteeism. AMA Arch Ind Health. 1955 Mar;11(3):218–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell S., D'Alonza C. A. Sickness absenteeism of alcoholics. J Occup Med. 1970 Jun;12(6):198–210. doi: 10.1097/00043764-197006000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman P. M., Trice H. M. The development of deviant drinking behavior. Occupational risk factors. Arch Environ Health. 1970 Mar;20(3):424–435. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1970.10665615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEPHERD R. D., WALKER J. Absence from work in relation to wage level and family responsibility. Br J Ind Med. 1958 Jan;15(1):52–61. doi: 10.1136/oem.15.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmence A. Rising sickness absence in Great Britain--a general practitioner's view. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1971 Mar;21(104):125–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRICE H. M. ALCOHOLIC EMPLOYEES; A COMPARISON OF PSYCHOTIC, NEUROTIC, AND "NORMAL " PERSONNEL. J Occup Med. 1965 Mar;7:94–99. doi: 10.1097/00043764-196503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. J. Individual variations in sickness absence. Br J Ind Med. 1967 Jul;24(3):169–177. doi: 10.1136/oem.24.3.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J., De la Mare G. Absence from work in relation to length and distribution of shift hours. Br J Ind Med. 1971 Jan;28(1):36–44. doi: 10.1136/oem.28.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]