Abstract

Latinx families face unique barriers to accessing traditional youth mental health services and may instead rely on a wide range of supports to meet youth emotional or behavioral concerns. Previous studies have typically focused on patterns of utilization for discrete services, classified by setting, specialization, or level of care (e.g., specialty outpatient, inpatient, informal supports), yet little is known about how youth support services might be accessed in tandem. This analysis used data from the Pathways to Latinx Mental Health study – a national sample of Latinx caregivers (N = 598) from across the United States collected at the start of the coronavirus pandemic (i.e., May–June 2020) – to describe the broad network of available supports that are used by Latinx caregivers. Using exploratory network analysis, we found that the use of youth psychological counseling, telepsychology, and online support groups was highly influential on support service utilization in the broader network. Specifically, Latinx caregivers who used one or more of these services for their child were more likely to report utilizing other related sources of support. We also identified five support clusters within the larger network that were interconnected through specific sources of support (i.e., outpatient counseling, crisis, religious, informal, and non-specialty). Findings offer a foundational look at the complex system of youth supports available to Latinx caregivers, highlighting areas for future study, opportunities to advance the implementation of evidence-based interventions, and channels through which to disseminate information about available services.

Keywords: health disparities, Latinx families, service utilization, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Latinx families experience significant barriers to accessing formal specialty mental health services (e.g., psychological counseling, psychiatric hospitalization) and instead may turn to a wide range of non-specialty (e.g., general primary care, parenting classes) and informal supports (e.g., social supports, mentoring programs) to meet youth mental health needs (Kapke & Gerdes, 2016). Unfortunately, the service utilization literature has largely focused on examining utilization patterns for discrete types of services (e.g., specialty outpatient, inpatient) and their correlates (Gudiño et al., 2008; Kapke & Gerdes, 2016; Vázquez, Alvarez, et al., 2021). Little research has considered more complex conceptualizations of service use that consider pathways and patterns linking the wide range of supports on which families rely. A clear and comprehensive understanding of such pathways may offer important insights regarding access to care for historically underserved populations that could be leveraged to reduce mental health disparities.

Recent work conducted as part of the Pathways to Latinx Mental Health (PLMH) study has shown that Latinx caregivers regularly engage in a wide array of youth supports, particularly if their child has clinically elevated emotional or behavioral problems (Vázquez, Alvarez, et al., 2021; Vázquez, Navarro Flores, et al., 2021). At the same time, Vázquez, Alvarez, et al. (2021) found that while Latinx caregivers utilized multiple youth support services, ranging from informal social supports to psychiatric hospitalization, they largely preferred formal mental health services, such as psychological counseling to address youths' emotional and/or behavioral problems. Thus, differences in service utilization patterns may reflect structural barriers to accessing formal services, perceptions regarding service needs, and/or the nature of the youth's problems and an appropriate method of intervening (Vázquez et al., 2022). While recent research has broadened our understanding of youth service utilization patterns and correlates (Vázquez, Alvarez, et al., 2021; Vázquez, Navarro Flores, et al., 2021), more work is needed to understand the complex network structure formed by the types of service use pathways accessed by Latinx families. Understanding Latinx families' points of entry into mental health services and subsequent engagement with additional supports could help providers enhance accessibility and acceptability of mental healthcare among underserved Latinx communities.

Support services exist at multiple levels of care and interact with each other, forming a broad network of support that collectively meets the emotional and behavioral health needs of youths. For example, seeking help from a school professional may lead to referrals and subsequent engagement with other supportive services that can address the needs of both the youths and their families (e.g., psychological counseling, psychiatric hospitalization, parenting classes; Alegría et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2013). Additionally, youths and families who receive psychological counseling may be more likely to be connected to school professionals to manage academic accommodations (Green et al., 2017), offered parenting classes (Patterson, 2005), provided education on crisis resources (e.g., crisis hotline, psychiatric hospitalization; Duong et al., 2020; Gould et al., 2012), and/or have access to telepsychology services in response to a global pandemic (Vázquez, Navarro Flores, et al., 2021).

Engagement with a strong social support network may direct Latinxs toward seeking formal mental health services (e.g., psychological counseling; Villatoro et al., 2014). Broader networks can include any number of individuals, organizations, or institutions, that can encourage or directly refer families to care providers. For example, primary care physicians typically provide pharmacological interventions for youth emotional and behavioral disorders, but they are also a common source of referrals to behavioral care (Geissler & Zeber, 2020). Notably, a recent survey found that caregivers most often preferred to receive information about available therapies from their adolescent's pediatrician, relative to insurers or school counselors (Becker et al., 2018). Religious organizations can also provide important support for Latinxs, with some offering activities and resources that promote positive youth development (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2016). However, faith-based organizations may also divert families from formal mental health services via etiological beliefs (e.g., psychiatric disorders may be attributed to weak faith; Ayvaci, 2016). In a final example, research suggests that online communities and support groups may not only improve functioning and reduce emotional distress, but they may also increase professional help-seeking and accurate knowledge about youth mental health and behavior (Griffiths, 2017; Helseth et al., 2021). An important next step for the field is to reconceptualize these sources of support as nodes within a broader network that collectively promotes help-seeking behaviors. Findings from this research may provide insights into the structure of support networks and identify novel avenues by which to increase Latinx families' engagement in mental health services.

Sources of support can be conceptualized as individual units, whose complex interplay forms a network contributing to and influencing families' service utilization patterns. Advancements in network analyses have made it possible to identify connections (edges) between sources of support (nodes) using graphical techniques (van Borkulo et al., 2014). Borrowing from network models used in physics, methodologists have introduced binary Ising models that incorporate Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression penalties that produce parsimonious networks (van Borkulo et al., 2014). Recent work by Epskamp et al. (2018) has further increased the utility of this modeling approach by developing measures of network stability and statistical tests for determining whether nodes/edges significantly differ from each other using bootstrapping. These statistical networks have already been applied to the structure of psychopathology (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013) and mental health risk factors (Pereira-Morales et al., 2019), providing evidence for the promise of this approach in providing insight into the structure of youth support networks.

Latinx families face significant challenges in accessing formal mental health services, which may impact pathways between services in their support network. The current study leveraged recent methodological advances in network analyses to offer a nuanced understanding of Latinx caregivers' help-seeking pathways within a single model that reflects a real-world context. We conducted exploratory network analyses to (a) understand the structure of youth support services utilized by Latinx caregivers, (b) delineate communities of support (clusters) within the larger network, and (c) identify specific support services with high impact on the overall support network. We hypothesized that common sources of support for youths would be positively interconnected, as they are common referral pathways to services that support youth well-being (i.e., psychological counseling, school professionals, and physicians; Duong et al., 2020). We expected social support to be positively associated with psychological counseling utilization (Griffiths, 2017; Villatoro et al., 2014). We also expected outpatient counseling formats to be positively related to each other (i.e., psychological counseling, telepsychology; Vázquez, Navarro Flores, et al., 2021) and to crisis services (i.e., hotlines, psychiatric hospitalization; Duong et al., 2020; Gould et al., 2012). Given the lack of research into broader service networks, we did not propose specific hypotheses regarding many of the unique services within the network structure. Exploratory analyses instead focused on the broader service network, including clusters and node prominence within the resulting network. While these network analyses are exploratory, services included within the network model are ubiquitous in the service utilization literature.

METHOD

Procedures

Data for the present study were collected as part of the PLMH study, which included 598 Latinx caregivers of youths between 6 and 18 years old from across the United States (Vázquez, Alvarez, et al., 2021). The aim of the PLMH study was to identify help-seeking patterns and related correlates among Latinx caregivers of youths from varying backgrounds. Participants were recruited through Qualtrics, an online survey panel company. Recruitment was conducted between May 21, 2020 and June 18, 2020. Participants completed a 20-minute online survey and provided information about their family demographics, utilization of youth support services, and youth emotional and/or behavioral problems. Contrasting attention checks were used to identify and remove respondents who provided poor-quality data (Abbey & Meloy, 2017). Inclusion criteria for the current study were (a) self-identifying as Latinx, (b) being a caregiver of at least one youth between the ages 6–18, (c) having the ability to complete the survey in English, and (d) living in the United States. A rate of $12.50 per participant was paid to Qualtrics for recruitment. Consistent with best practices for protecting survey panel research against bots and malicious respondents, participants were only compensated when they completed the entire survey and passed validity checks (Lowry et al., 2016). Participants were compensated in the form of points that could be redeemed for rewards from Qualtrics. Study procedures were approved by the Utah State University Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Of those who accessed the survey (n = 3149), roughly one-third (n = 1128) met the inclusion criteria. Some participants met inclusion criteria but did not consent to participate (n = 17), provided poor-quality data as identified by attention checks (n = 235), or did not complete the survey (n = 278) and were excluded from the current study. In total, 598 caregivers provided complete data and were included in the current sample.

Measures

Demographics

Caregivers reported their demographic information (i.e., age, binary gender, marital status, generational status in the United States, education, household income) and that of their qualifying youth (i.e., age, gender, insurance status). Generational status in the United States was defined as either first (i.e., respondent was born in another country), second (i.e., at least one of the respondent's parents was born elsewhere), third (i.e., a grandparent was born elsewhere), or fourth or greater (i.e., a great grandparent, or further, was born elsewhere).

Emotional or behavioral problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; ages 6–18; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) has established validity and reliability in Latinx samples in the United States (Haack et al., 2016) and provided information on clinical needs within the current sample. The CBCL consists of 113-items that assess a broad range of youth emotional and behavioral problems within the last 6 months. Responses were: not true (0), sometimes true (1), or often true (2). The CBCL produces two composite scores representing youth internalizing (e.g., depression, anxiety) and externalizing problems (e.g., aggression, oppositionality). Dichotomous variables were created to represent whether youths had clinically elevated internalizing or externalizing problems (i.e., T score above 63; coded yes [1] or no [0]). Internal consistency was excellent in the current sample (i.e., internalizing α = 0.95; externalizing α = 0.96).

Service utilization

The Caregiver Support Services Questionnaire (CSSQ) was created for the PLMH study to gather information on caregivers' utilization of a variety of youth supports (Vázquez & Domenech Rodríguez, 2021). The CSSQ includes 11-items querying past-year caregiver utilization of specific youth support services (see Table 1 for the full list). Responses were yes (1) or no (0). The CSSQ was created due to limitations associated with established service utilization measures, such as interview-based administration and the absence of questions regarding mentorship programs, parenting classes, and telepsychology services (Ascher et al., 1996; Jensen et al., 2004). Prior research has established the construct validity of the CSSQ in the PLMH data, as caregivers of youths with clinical level scores on the CBCL were generally more likely to report service use relative to subclinical youths (Vázquez, Alvarez, et al., 2021; Vázquez, Navarro Flores, et al., 2021).

TABLE 1.

Rates of support service use and network weighted adjacency matrix.

| Percent used |

[1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [11] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] Psychological counseling | 35.1% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| [2] Telepsychology | 19.6% | 1.84 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| [3] School professional | 37.1% | 1.63 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| [4] Parenting classes | 16.1% | 0.57 | 0.90 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| [5] Physician | 43.1% | 0.64 | 0.66 | 1.22 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| [6] Crisis hotline | 5.5% | 0.00 | 1.36 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| [7] Psychiatric hospitalization | 4.8% | 1.35 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.58 | – | – | – | – | – |

| [8] Mentorship program | 14.7% | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 1.37 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.81 | – | – | – | – |

| [9] Online support group | 12.9% | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.53 | – | – | – |

| [10] Minister or faith healer | 11.0% | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 1.10 | – | – |

| [11] Social supports | 40.8% | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.63 | – |

Note: The connections that are rated as 0.00 were eliminated due to the LASSO regression penalty that reduces small effect sizes to zero.

Analytic plan

Descriptive statistics were calculated to contextualize the sample based on demographic characteristics and rates of clinical mental health service need (i.e., CBCL internalizing and externalizing problems). Binary support service utilization indicators were then examined using an Ising network model (van Borkulo et al., 2014). An Ising network model includes a LASSO regression penalty that produces sparser models by reducing small effects to zero (van Borkulo et al., 2014). This regularization procedure produces more interpretable network models by limiting the number of edges (i.e., estimated relationships) connecting nodes (i.e., sources of support) to those with the largest effects. The Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm was then used to establish the optimal structure of the network with the most interconnected nodes more tightly grouped toward the center and loosely connected nodes further to the exterior of the graph (Epskamp et al., 2018). The Walktrap algorithm was then used to identify communities by measuring within and between node distances using hierarchical clustering (Epskamp et al., 2018). We then calculated three common centrality measures to understand the properties of the network structure: strength (i.e., number of edges connected to a node), closeness (i.e., the importance of a node in influencing nearby nodes), and betweenness (i.e., importance of a node in acting as a bridge to the rest of the network; Epskamp et al., 2018). Strength is interpreted as the extent to which a service is connected to other services, such that high strength can be interpreted as a node that is used with many other nodes. Closeness is the degree to which the use of a service is associated with the use of other proximal services. In other words, access to a source of support with high closeness is likely to predict access to other nearby sources of support within the network. Lastly, betweenness describes the extent to which a support service acts as a gatekeeper associated with use in the broader network. A source of support with high betweenness likely plays a larger role in determining families' access to other sources of support within the broader network. Case-dropping bootstrapping was then used to examine the stability of network centrality measures on subsets of data (1000 iterations; Epskamp et al., 2018). Estimates that were above the recommended centrality stability coefficient of 0.5 were considered stable, indices below this cut point should be interpreted with caution (Epskamp et al., 2018). Lastly, bootstrapped difference tests were used to identify edges/nodes that differed significantly (p < 0.05) from other edges/nodes (1000 iterations; Epskamp et al., 2018).

RESULTS

Participating caregivers averaged 35.5 years of age (SD = 9.1 years) and were predominately female (70.2%), biological parents (94.5%), and were largely married (70.7%). Most participants reported being first- (24.2%) or second-generation (47.3%) immigrants to the United States. Some participants were third- (16.1%) or fourth- (12.4%) generation immigrants to the United States. Caregivers who reported being first-generation in the United States (n = 145) were most frequently born in Mexico (25.5%), Dominican Republic (12.4%), Venezuela (11.7%), Peru (7.6%), Cuba (5.5%), and El Salvador (4.8%). Many first-generation caregivers reported being born in the United States territory of Puerto Rico (29.7%). Participants most frequently reported equal language preference for English and Spanish (45.3%). When asked to describe their qualifying child, caregivers reported that their youths were 11.9 years of age on average (SD = 3.4 years) were balanced on a binary gender measure (54.8% male), and typically had health insurance coverage (private 49.8%; public 46.5%). Caregivers reported that 22.4% of youths had clinically elevated externalizing problems while 30.6% had internalizing problems in the past 6 months. Caregivers had accessed a wide array of supports for their child in the last year, including psychological counseling (35.1%); telepsychology (19.6%); school professionals (37.1%); parenting classes (16.1%); physicians (43.1%); crisis hotlines (5.5%); psychiatric hospitalization (4.8%); mentorship programs (14.7%); online support groups (12.9%); ministers or faith healers (11.0%); social supports (40.8%). On average, caregivers reported accessing help for their youth from 2.4 sources of support (SD = 2.6) in the last year.

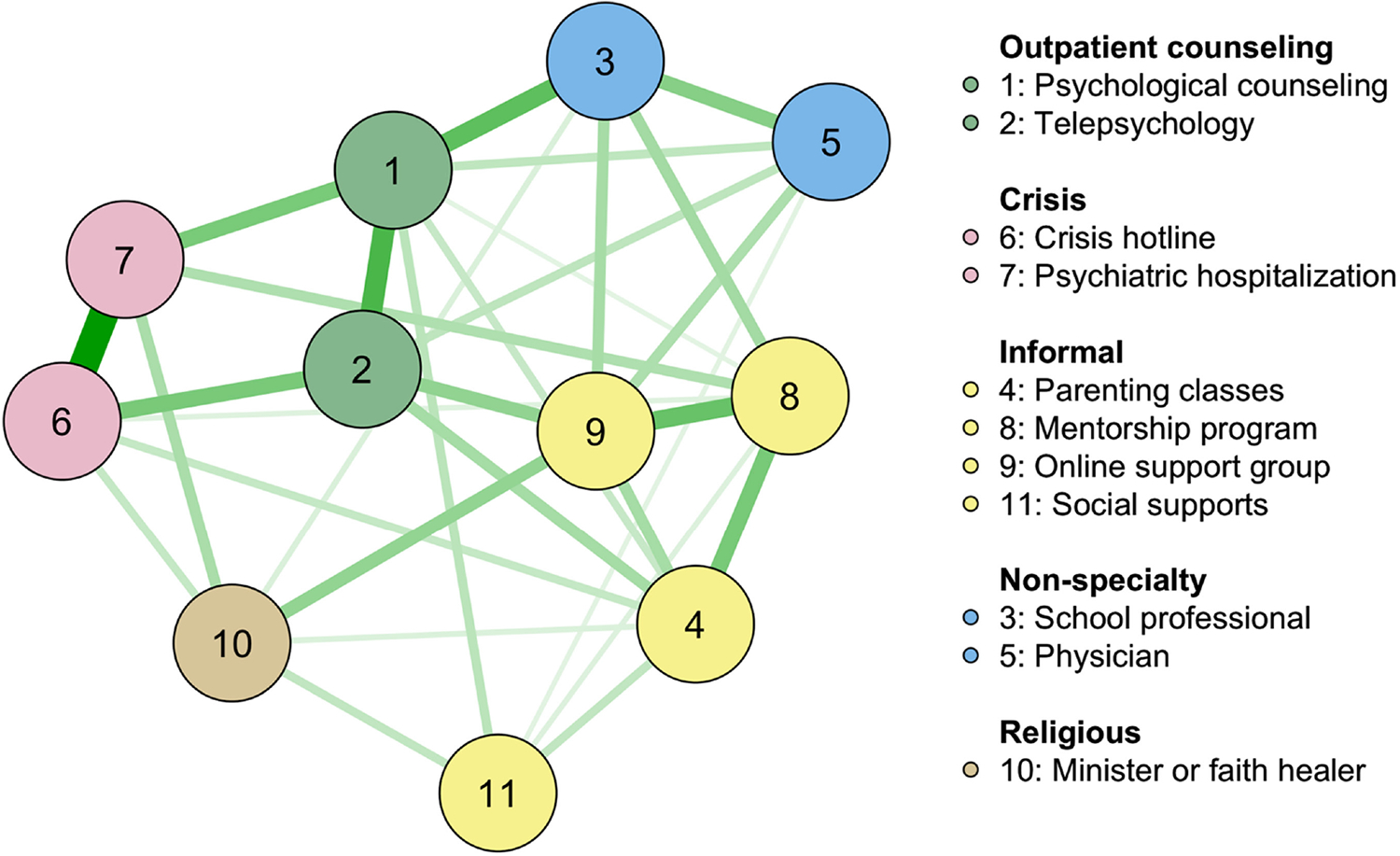

The youth support services network includes 31 non-zero edges out of 55 possible edges due to the LASSO penalty. See Table 1 for the weighted adjacency matrix and Figure 1 for the network diagram. Latinx caregivers' utilization of youth services was generally positively associated with the use of other sources of support. The strongest connections were between psychiatric hospitalization and crisis hotlines, psychological counseling and telepsychology, psychological counseling and school professionals, online support groups and mentorship programs, psychiatric hospitalization and psychological counseling, crisis hotlines and telepsychology, parenting classes and mentorship programs, and school professionals and physicians.

FIGURE 1.

Youth support services network with community detection. Note: Green edges signify positive relationships and the thickness of the edge represents the strength of connections. Variables are dichotomous indicators representing service utilization in the last year: (1) yes or (0) no.

The Walktrap algorithm detected five support communities within the network: outpatient counseling (i.e., psychological counseling, telepsychology), crisis (i.e., psychiatric hospitalization, crisis hotline), religious (i.e., minister or faith healer), informal (i.e., mentorship program, general parenting classes, online support group, social supports [friends/family]), and non-specialty (i.e., school professional, physician) supports. These support communities form complex connections with each other of varying strengths.

The network centrality measures suggest that psychological counseling, telepsychology, and online support group nodes had the highest strength, closeness, and betweenness, indicating that they were the most central nodes within the overall service network. In contrast, the nodes representing social support, physicians, and ministers or faith healers had the lowest strength, closeness, and betweenness, suggesting each type of support lacked connectivity with other supports. Nodes representing school professionals, psychiatric hospitalization, parenting classes, mentorship programs, and crisis hotlines were consistently in between these two extremes across metrics. See Figure 2 for centrality measures. Network centrality measures were above the recommended cutoff for strength and closeness metrics (i.e., coefficient of 0.5), but not betweenness. See Figure S1 for the network stability plot. These findings suggest that strength and closeness metrics were stable across subsets of the data, while betweenness was not and should be interpreted with caution.

FIGURE 2.

Centrality measures for youth support services network.

Figures S2-S4 display results of bootstrapped difference tests for strength, closeness, and betweenness, respectively. Higher strength nodes did not significantly differ from each other (ps >0.05; i.e., psychological counseling, telepsychology, online support groups). However, the differences in strength between several higher and lower strength nodes were significant. Specifically, telepsychology was greater than social supports (p < 0.05), physicians (p < 0.05), and ministers or faith healers (p < 0.05); psychological counseling was greater than social supports (p < 0.05) and ministers or faith healers (p < 0.05); online support groups was greater than social supports (p < 0.05), physicians (p < 0.05), and ministers or faith healers (p < 0.05). Nodes with greater closeness did not significantly differ from each other (ps >0.05; i.e., psychological counseling, telepsychology, online support groups). Betweenness did not significantly differ between nodes with the exception that psychological counseling (p < 0.05) and telepsychology (p < 0.05) had significantly higher betweenness relative to social supports.

The strength of the edges between psychiatric hospitalization and crisis hotlines, psychological counseling and telepsychology, psychological counseling and school professionals, online support groups and mentorship programs, crisis hotlines and telepsychology, and psychiatric hospitalization and psychological counseling did not significantly differ from each other (ps >0.05), but they were significantly stronger than many of the other connections within the network (ps <0.05). Specifically, two edges were significantly weaker than the connection between psychiatric hospitalization and crisis hotlines (ps <0.05; i.e., parenting classes and mentorship programs, school professionals and physicians). See Figure S5 for bootstrapped difference test for network edges.

DISCUSSION

The current study explored the broad network of youth support services used by Latinx caregivers, as well as the support services' relationships with other services. Findings suggest that in general, Latinx families' use of any source of support for youth mental health was positively associated with the use of other sources of support. Analyses provided a visual representation of the network formed by these sources of support in the current sample and identified the relative strength of connections between supports. We also identified five supportive “communities” within the larger network that were interconnected through specific sources of support (i.e., outpatient counseling, crisis, religious, informal, non-specialty).

Our findings suggest that psychological counseling, telepsychology, and online support groups are important sources of support that are associated with the use of other types of youth services. Psychological counseling and online support groups had the highest strength, closeness, and betweenness within the network. Collectively, these findings suggest that Latinx caregivers utilized a wide array of supports in conjunction with these services. Additionally, the utilization of these services was positively associated with the use of surrounding connected supports and those in the broader network. These findings suggest that help-seeking is a continuous, multi-episodic process among Latinx caregivers. Previous research has documented individuals “muddling through” or using multiple supports that eventually led them to engage in formal mental health services (Pescosolido et al., 1998). It is possible that these findings may reflect Latinx caregivers muddling through different sources of support toward or down from higher levels of mental health care for their youths. Telepsychology services had high strength and closeness but low betweenness, which suggests that these services were commonly used with other closely related supports but were not strongly related to use in the broader network. This network dynamic may reflect the narrowing of community supports and a shift from in-person mental health services to telepsychology during the coronavirus pandemic (Vázquez, Navarro Flores, et al., 2021).

Specific connections between individual services and support communities were also observed. Notably, the counseling and telepsychology nodes belonged to the outpatient counseling support community, which had strong ties with the crisis (i.e., psychological counseling, telepsychology) and non-specialty services (i.e., school professionals, physicians) clusters. These strong connections likely reflect bidirectional referrals and interactions between outpatient counseling, crisis services (e.g., step up or down in care, recommending crisis hotlines between sessions for at-risk clients), and school professionals (e.g., assessment for classification, referral for formal mental health services; Green et al., 2017), demonstrating how families often engage multiple support services to address youth emotional and behavioral needs. Latinx families may utilize physicians' services for their youth in conjunction with school professional and outpatient services, which builds on prior research that identified these services as common sources of support for youths (Duong et al., 2020). Importantly, the strength of these connections may have been facilitated, at least in part, by the high rate of health insurance coverage within the current sample. As such, connections to traditional healthcare services may be weaker in samples with lower rates of health insurance coverage due to the high financial burden on uninsured or underinsured families. Though online support groups were clustered with the informal support community, they demonstrated strong ties both within (i.e., mentorship programs, parenting classes) and beyond that cluster (i.e., outpatient, religious, and non-specialty support communities). This suggests that online support groups were widely used by Latinx families, regardless of the other support services they accessed. Other studies have similarly demonstrated that online support groups may act as a bridge, promoting the utilization of other sources of support, and are a commonly utilized overlapping source of support among Latinx youths (Griffiths, 2017). Our findings support this notion and suggest that online support groups could be used to engage Latinx families in a broader support service network.

Research has shown that Latinxs with strong social support are more likely to utilize formal mental health services (Villatoro et al., 2014). The current results suggest that there was a positive connection between social support and the use of psychological counseling, but the relationships had a weaker connection relative to other sources of support within the broader network. It is possible that this effect may also reflect the absence of information regarding the perceived strength of social support. Thus, while social support had positive connections with several other sources of support (i.e., psychological counseling, parenting classes, physicians, mentorship programs, ministers or faith healers), its position within the network demonstrated its relatively low centrality. This pattern may represent a distinction between bridging (i.e., homogeneous support) and bonding (i.e., heterogeneous supports) social capital (Coffé & Geys, 2007). Ties with bonding capital, such as those with close friends and family, provide significant emotional support but less informational and instrumental support; whereas bridging capital present in ties with less familiar acquaintances can provide novel information that bridges individuals to new resources – in this case, novel sources of support within the network. In this way, social support, though still functionally important, may have weaker ties to new sources of support such as formal mental health services when compared with members of other formalized systems, such as hospitals, crisis care, and schools. Surprisingly, physician support services were generally less connected to other sources of support within the broader network but consistent with the literature, this node had a positive connection with outpatient counseling service utilization (Sayal et at., 2002).

While less central within the broader network, the religious support community (i.e., ministers or faith healers) was connected to the utilization of crisis services, help from school professionals, and specific informal supports (e.g., parenting classes, social supports). These connections may reflect the importance of religious supports in directing Latinx families toward specific community-based supports. However, it should be noted that prior research using the PLMH sample has found that ministers and faith healers were among the least preferred sources of support for addressing youth emotional or behavioral problems (Vázquez, Alvarez, et al., 2021). As most services within the current study are related in some way to youth emotional or behavioral problems, it is possible that participants utilized other more preferred sources of support for their youths.

Implications

These exploratory analyses offer a first look at the broader network of informal and formal supports accessed by Latinx caregivers seeking to address their child's emotional and behavioral health needs and offer three overarching implications. First, prominent service utilization frameworks focus on individual episodes of help-seeking, in which caregivers identify a need for youth support services, decide to seek help, and select an appropriate means of intervening (Cauce et al., 2002; Srebnik et al., 1996). These frameworks also focus primarily on the use of formal mental health services and do not incorporate the possibility of engaging with multiple levels and types of services simultaneously or over time. Our findings may indicate the need to develop a new dynamic network theory of help-seeking that captures multiple episodes of care across different sources of support accessed by caregivers on behalf of youths. Further research is needed to understand how family-level (e.g., two-parent versus single-parent families; insurance status, household income, documentation status), youth-level (e.g., clinical need, age, gender), cultural (e.g., interpretations of illness and appropriate means of intervention; acculturation), and contextual (e.g., urban and rural settings; barriers to care) factors may contribute to differences in support service networks to guide the development of a new theoretical framework (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2000; G & Gudiño, 2021; Garcini et al., 2023; Howell & McFeeters, 2008; Vázquez et al., 2022).

Second, another important step in moving families either toward or away from higher levels of youth mental health care may involve coordinating and linking community-based services (Butel et al., 2021; Pescosolido et al., 1998). Our findings point to several opportunities where increased efforts to disseminate knowledge of formal mental health services might promote referrals for families in need of care. For example, religious support was connected to the use of crisis services, help from school professionals, and informal supports such as parenting classes; however, it was not related to the use of outpatient therapy or telepsychology services. This is just one example of an untapped opportunity to engage a subset of Latinx families who may not otherwise seek evidence-based interventions. Future research should determine whether examining community-level service networks could help identify opportunities to coordinate/link sources of support to better direct families toward potentially beneficial services.

Third, further investigation regarding the nature of relationships between services of higher versus lower centrality in the overall network and methods of increasing connectivity is warranted. Understanding these relationships may direct public health efforts to better identify the routes by which families arrive at necessary mental health care, and the combination of supports that appropriately meet caregivers' and youth needs. For example, results point to psychological counseling, telepsychology, and online support groups as central nodes within the support service network. These findings indicate that the use of these services was associated with engagement with other sources of support in the current sample's network; however, these data may instead indicate that caregivers seeking these sources of support were more likely to need or attempt to access other sources of support due to some other variable or variables (e.g., clinical severity and/or functional impairment experienced by their child). Conversely, analyses show that the use of social supports and physician services was generally less connected to the utilization of other forms of support. While this may indicate that these nodes are less likely to act as pathways to other nodes in the network, they may also demonstrate that these supports act as a stopping point – either because they impede access to other nodes, or are seen as sufficient and thus preclude the need to access additional services. For example, research has shown that support provided by family members may act as a barrier to seeking formal mental health services due to familial mental health stigma and/or fear of embarrassing the family (Villatoro et al., 2014). Alternatively, psychiatric problems and prescription of psychotropic medications are increasingly managed in primary care settings (e.g., Barkil-Oteo, 2013), such that Latinx caregivers and youths accessing physician support may deem those services sufficient in addressing their needs. One potential approach to increasing the connectivity of these nodes may be using community-based lay health workers and general medical practitioners as vectors for spreading information and referrals that could act as a bridge to other services as needed (Garcia et al., 2022; Perry & Pescosolido, 2010).

Limitations

The implications of the current results must be considered within the context of some limitations. Findings from the network analysis indicate the strength of relationships between entities but should not be used to infer causality or timing of connections. The current study examined a support service network used by parents of children of all ages. Future research focusing on support service network utilization patterns during various developmental periods may shed light on patterns of use by caregivers across childhood, or perhaps critical periods during which access to specific sources of support may prove particularly impactful on downstream outcomes.

Data collection occurred in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, which likely impacted families' abilities to access support services for several of the months assessed. For example, prior research using the PLMH study found that many participants who utilized telepsychology services migrated to this format from in-person psychological counseling (Vázquez, Navarro Flores, et al., 2021). The shift from in-person to remote service delivery may explain why these services were grouped into a single community, in addition to providing equivalent services. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic may also explain the indirect connection between telepsychology and psychiatric hospitalization through crisis hotlines. It is possible that crisis hotlines were recommended by telepsychology services during a period when youths may have experienced increased psychological distress related to the pandemic (Fitzpatrick et al., 2020). However, there are indications that pandemic-era adjustments will lead to more permanent changes in service delivery (Li et al., 2022). Furthermore, the exacerbation of youth mental health problems by the COVID-19 pandemic – referenced by the United States Surgeon General as a national public health crisis (Office of the Surgeon General, 2021) – coupled with uneven access to healthcare services due to changing pandemic restrictions, especially in the early months of this study, may have significantly impacted utilization of and connections between both formal and informal supports. More work is needed to confirm our exploratory findings and examine lasting shifts in the mental health landscape using data collected after the lifting of social distancing measures related to the pandemic.

While using Qualtrics panels allowed us to survey participants safely during the coronavirus pandemic, several limitations are associated with this approach. The current study only utilized data from participants who provided complete and high-quality responses. Examining patterns of missingness and imputing missing values was not possible as Qualtrics only provided data on cases with complete high-quality responses. It is possible that participants who were uncomfortable with reporting on their child's mental health problems may have been less likely to complete the survey. Research is needed to confirm our findings using complete data or a recruitment method that allows for the imputation of missing responses. The current findings may not generalize to clinical samples, as this study used a general community sample of Latinx caregivers. The needs and service utilization patterns of Latinx families are likely influenced by clinical need and therefore warrant future study. The PLMH study also required caregivers to complete the survey in English due to feasibility issues with meeting the recruitment quota, which may have resulted in specific acculturation patterns. The current sample was largely bicultural (71.5% were first or second-generation; 45.3% equally preferred English and Spanish), and although more variety in acculturation levels might have been beneficial for generalizability, a largely bicultural sample is unique and provides new insights into an understudied population facing significant disparities in healthcare access.

CONCLUSIONS

This study describes the network connecting sources of support accessed by Latinx caregivers of youths in a nonclinical sample. Findings provide a first look at the broader constellation of supports available to caregivers while highlighting (a) overall positive associations between the use of support services examined and (b) evidence of specific mental health services (i.e., psychological counseling, telepsychology, and online support groups) that were especially central within the network and were associated with accessing other supports. Understanding patterns of service utilization, and associations between services accessed, may uncover pathways serving as barriers/facilitators of service use that can be targeted to implement evidence-based mental health interventions. On a broader scale, this work may identify untapped opportunities to build connections between high-use sources of support and other formal services via universal prevention, education, and public health initiatives.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by an American Psychological Foundation Visionary Fund Grant. PI: Alejandro L. Vázquez. This work is dedicated to the memory of Luis J. Vázquez.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- Abbey JD, & Meloy MG (2017). Attention by design: Using attention checks to detect inattentive respondents and improve data quality. Journal of Operations Management, 53(1), 63–70. 10.1016/j.jom.2017.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Lin JY, Green JG, Sampson NA, Gruber MJ, & Kessler RC (2012). Role of referrals in mental health service disparities for racial and ethnic minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(7), 703–711. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher BH, Farmer EM, Burns BJ, & Angold A (1996). The child and adolescent services assessment (CASA) description and psychometrics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 4(1), 12–20. 10.1177/106342669600400102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayvaci ER (2016). Religious barriers to mental healthcare. American Journal of Psychiatry Residents' Journal, 11(7), 11–13. 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.110706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barkil-Oteo A. (2013). Collaborative care for depression in primary care: How psychiatry could “troubleshoot” current treatments and practices. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 86(2), 139–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ, Helseth SA, Frank HE, Escobar KI, & Weeks BJ (2018). Parent preferences and experiences with psychological treatment: Results from a direct-to-consumer survey using the marketing mix framework. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(2), 167–176. 10.1037/pro0000186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, & Cramer AOJ (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Horwitz SM, Schwab-Stone ME, Leventhal JM, & Leaf PJ (2000). Mental health in pediatric settings: Distribution of disorders and factors related to service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(7), 841–849. 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AW, Gourdine RM, Waites S, & Owens AP (2013). Parenting in the twenty-first century: An introduction. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23(2), 109–117. 10.1080/10911359.2013.747410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butel J, Braun KL, Davis J, Bersamin A, Fleming T, Coleman P, Leon Guerrero R, & Novotny R (2021). Community social network pattern analysis: Development of a novel methodology using a complex, multilevel health intervention. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement, 14(1), 1–18. 10.5130/ijcre.v14i1.7485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M, Paradise M, Cochran BN, Shea JM, Srebnik D, & Baydar N (2002). Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: A focus on ethnic minority youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(1), 44–55. 10.1037/0022-006x.70.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffé H, & Geys B (2007). Toward an empirical characterization of bridging and bonding social capital. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(1), 121–139. 10.2139/ssrn.997340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Lee K, Cox S, Coifman J, Mayworm A, & Lyon AR (2020). Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1-20, 420–439. 10.1007/s10488-020-01080-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Borsboom D, & Fried EI (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. 10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Harris C, & Drawve G (2020). Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S17–S21. 10.1037/tra0000924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan T, & Gudiño OG (2021). Understanding Latinx youth mental health disparities by problem type: The role of caregiver culture. Psychological Services, 18(1), 116–123. 10.1037/ser0000365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Barnett ML, Rothenberg WA, Tonarely NA, Perez C, Espinosa N, Salem H, Alonso B, San Juan J, Peskin A, Davis EM, Davidson B, Weinstein A, Rivera YM, Orbano-Flores LM, & Jent JF (2022). A natural helper intervention to address disparities in parent child-interaction therapy: A randomized pilot study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 52, 343–359. 10.1080/15374416.2022.2148255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini LM, Vázquez AL, Abraham C, Abraham C, Sarabu V, & Cruz PL (2023). Implications of undocumented status for Latinx families during the COVID-19 pandemic: A call to action. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology., 1–14. 10.1080/15374416.2022.2158837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler KH, & Zeber JE (2020). Primary care physician referral patterns for behavioral health diagnoses. Psychiatric Services, 71(4), 389–392. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Munfakh JL, Kleinman M, & Lake AM (2012). National suicide prevention lifeline: Enhancing mental health care for suicidal individuals and other people in crisis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(1), 22–35. 10.1111/j.1943-278x.2011.0068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, Comer JS, Donaldson AR, Elkins RM, Nadeau MS, Reid G, & Pincus DB (2017). School functioning and use of school-based accommodations by treatment-seeking anxious children. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25(4), 220–232. 10.1177/1063426616664328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths KM (2017). Mental health internet support groups: Just a lot of talk or a valuable intervention? World Psychiatry, 16(3), 247–248. 10.1002/wps.20444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño OG, Lau AS, & Hough RL (2008). Immigrant status, mental health need, and mental health service utilization among high-risk Hispanic and Asian Pacific islander youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(3), 139–152. 10.1007/s10566-008-9056-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haack LM, Kapke TL, & Gerdes AC (2016). Rates, associations, and predictors of psychopathology in a convenience sample of school-aged Latino youth: Identifying areas for mental health outreach. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 2315–2326. 10.1007/s10826-016-0404-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helseth SA, Scott K, Escobar KI, Jimenez F, & Becker SJ (2021). What parents of adolescents in residential substance use treatment want from continuing care: A content analysis of online forum posts. Substance Abuse, 42(4), 1049–1058. 10.1080/08897077.2021.1915916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell E, & McFeeters J (2008). Children's mental health care: Differences by race/ethnicity in urban/rural areas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19(1), 237–247. 10.1353/hpu.2008.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Eaton Hoagwood K, Roper M, Arnold LE, Odbert C, Crowe M, Molina BSG, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Hoza B, Newcorn J, Swanson J, & Wells K (2004). The Services for Children and Adolescents–Parent Interview: Development and Performance Characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(11), 1334–1344. 10.1097/01.chi.0000139557.16830.4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapke TL, & Gerdes AC (2016). Latino family participation in youth mental health services: Treatment retention, engagement, and response. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(4), 329–351. 10.1007/s10567-016-0213-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Glecia A, Kent-Wilkinson A, Leidl D, Kleib M, & Risling T (2022). Transition of mental health service delivery to telepsychiatry in response to COVID-19: A literature review. Psychiatric Quarterly, 93(1), 181–197. 10.1007/s11126-021-09926-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry PB, D’Arcy J, Hammer B, & Moody GD (2016). “Cargo Cult” science in traditional organization and information systems survey research: A case for using nontraditional methods of data collection, including Mechanical Turk and online panels. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 25(3), 232–240. 10.1016/j.jsis.2016.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General. (2021). Protecting youth mental health: The U.S. surgeon General's advisory. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34982518/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR (2005). The next generation of PMTO models. The Behavior Therapist, 28(2), 25–32. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2005-04671-001 [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Morales AJ, Adan A, & Forero DA (2019). Network analysis of multiple risk factors for mental health in young Colombian adults. Journal of Mental Health, 28(2), 153–160. 10.1080/09638237.2017.1417568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry BL, & Pescosolido BA (2010). Functional specificity in discussion networks: The influence of general and problem-specific networks on health outcomes. Social Networks, 32(4), 345–357. 10.1016/j.socnet.2010.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Gardner CB, & Lubell KM (1998). How people get into mental health services: Stories of choice, coercion and “muddling through” from “first-timers”. Social Science & Medicine, 46(2), 275–286. 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00160-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JL, & Brooks-Gunn J (2016). Evaluating youth development programs: Progress and promise. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 188–202. 10.1080/10888691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayal K, Taylor E, Beecham J, & Byrne P (2002). Pathways to care in children at risk of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181(1), 43–48. 10.1192/bjp.181.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebnik D, Cauce AM, & Baydar N (1996). Help-seeking pathways for children and adolescents. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 4(4), 210–220. 10.1177/106342669600400402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Borkulo CD, Borsboom D, Epskamp S, Blanken TF, Boschloo L, Schoevers RA, & Waldorp LJ (2014). A new method for constructing networks from binary data. Scientific Reports, 4(1), 1–10. 10.1038/srep05918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez AL, Alvarez MC, Navarro Flores CM, González Vera JM, Barrett TS, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2021). Youth mental health service preferences and utilization patterns among Latinx caregivers. Children and Youth Services Review, 131, 106258. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez AL, Culianos D, Navarro Flores CM, Alvarez MC, Barrett TS, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2022). Psychometric evaluation of a barriers to treatment questionnaire for Latina/o/x caregivers of children and adolescents. Child & Youth Care Forum, 51, 847–864. 10.1007/s10566-021-09656-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez AL, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2021). Caregiver support services questionnaire (CSSQ). Retrieved from osf.io/ya4ge. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez AL, Navarro Flores CM, Alvarez MC, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2021). Latinx caregivers' perceived need for and utilization of youth telepsychology services during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 9(4), 284–298. 10.1037/lat0000192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villatoro AP, Morales ES, & Mays VM (2014). Family culture in mental health help-seeking and utilization in a nationally representative sample of Latinos in the United States: The NLAAS. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(4), 353–363. 10.1037/h0099844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.