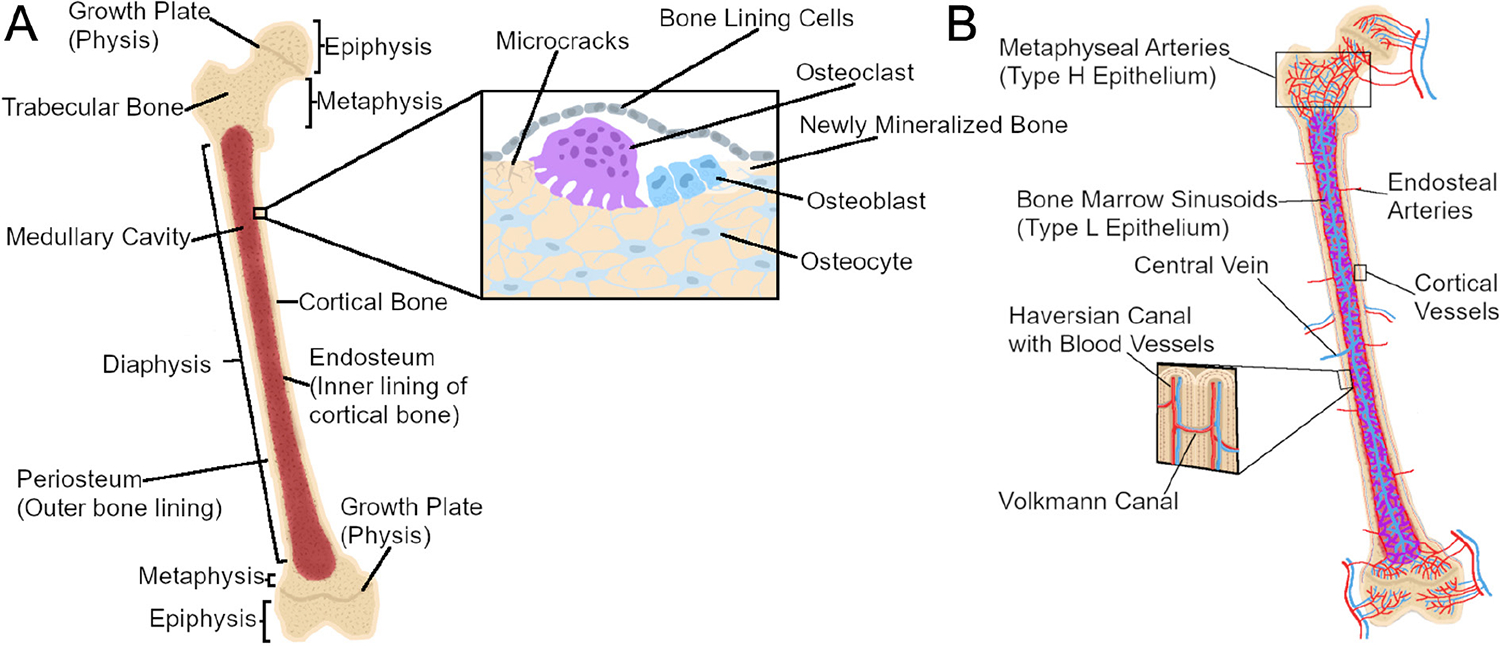

Figure 1.

Long bone anatomy and cellular composition. (A) Long bones are hollow, marrow-filled shafts with rounded, sealed ends. The diaphysis is the middle, tubular shaft of bone in of the bone which encases the medullary cavity and the bone marrow. Proximal and distal to the diaphysis are the conical epiphyses, whose rounded ends provide attachment sites for connective tissue. In growing individuals, the epiphysis and diaphysis are separated by the metaphysis, whose growth plates (physes) allow for longitudinal growth before ultimately fusing with the epiphysis in adulthood. Bone tissue is composed of spongy trabecular bone found inside bone, primarily within the epiphysis, while compact cortical bone forms the thick outer shell of the bone. The cellular composition of bone involves bone-resorbing osteoclasts, bone-forming osteoblasts, and matrix-entrapped osteocytes that coordinate the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Bone-lining cells cover bone surfaces in the absence of formation or resorption; they can be mobilized to active osteoblasts during remodeling. (B) Bones are intricately vascularized to meet high metabolic demands. Cortical bone is supplied through large arteries which enter the bone in the diaphysis. Cortical bone vasculature is then organized into Haversian and Volkmann canals which supply blood longitudinally and sagittally, respectively. In contrast, the trabecular vasculature enters near the metaphysis to provide oxygen-rich blood (red) to the growth plate before draining into the medullary cavity to provide less oxygen-rich blood (purple) to the bone marrow. Oxygen-poor blood in the medullary cavity (blue) then drains through a central vein which exits the bone through the diaphysis.