Summary

Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) with abundant resource and high safety are attracting intensive interest from both research and industry communities in meeting the ever-increasing energy demands. Despite the rapid advance of SIBs, it is difficult yet necessary to enhance the cycling and rate performance at anode due to the sluggish kinetics of “fat” Na+. This review provides an overview of two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials with a short ion diffusion pathway and a superior active sites exposure from the perspectives of synthesis, material chemistry, and structure engineering. We present the design principle of ideal carbon materials in SIBs. Moreover, we discuss the structure and chemistry regulations of different 2D materials to promote the efficient ion mass transfer and storage according to the different mechanisms of alloying, conversion, and insertion. Finally, we propose the remaining challenges and the possible solutions, in hope of guiding the future development of this booming field.

Subject areas: Applied sciences, Energy storage, Nanomaterials

Applied sciences; Energy storage; Nanomaterials

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed the rapid advance in utilizing renewable sources, e.g., solar, wind, and tidal, to deal with serious energy and environment crises.1,2,3 However, due to the randomness and intermittence of renewable energy, it is necessary to develop efficient energy storage systems such as various secondary batteries to store and deliver the generated electricity.4,5,6,7 Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) with high energy density and mature assembly processes have been widely applied in large-scale electricity supply and various portable electronic devices.8,9,10,11 However, the limited reserve and uneven distribution of lithium sources on earth gradually increase the cost of LIBs and seriously limit the application in the large-scale energy storage.12,13,14 Safety concern is another challenge for LIBs application in the large-scale energy storage.15,16,17,18 Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) that demonstrate a similar electrochemical mechanism to LIBs are widely accepted as one of the most promising substitutes.19,20,21 Compared with LIBs, SIBs exhibit the advantage of low cost enabled by the rich reserves and extensive distribution of sodium resources in the crust. In addition, SIBs can adopt Al as the current collector rather than the traditional expensive and heavy Cu employed by LIBs. SIBs have experienced a continuous advance since 1967 and developed rapidly in the latest 5 years,22,23,24 benefitting from the gradual breakthrough made in battery chemistry and electrode material design, where two-dimensional (2D) materials play a significant role (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Roadmap of the development history of SIBs, which presents the milestone regarding electrode materials, electrolyte, and battery chemistry of SIBs

SIBs are going through a rapid advance in capacity and rate performance benefitting from the similar working principles of ion intercalation and/or adsorption compared with LIBs.25,26 Similar electrode materials and electrolytes together with identical investigation methodologies were successively developed to deepen the insight into SIBs and improve the overall performance. However, the apparently larger radius of sodium ion (0.102 nm) than that of lithium ion (0.076 nm) causes the slow ion transport, sluggish reaction kinetics, and large volume change in electrodes, seriously decreasing the capacity and rate performance. For example, the most commonly used graphite that possesses a high theoretical capacity of 372 mAh g-1 as the anode for LIBs can only deliver a very small capacity in SIBs (37 mAh g-1).27 Therefore, it is urgent to develop advanced anode materials with large capacity, good rate performance, and cycling stability to promote the practical application of SIBs.

In the past decade, significant progress has been made in anode materials for SIBs, targeting at enhancing cycle stability, rate capability, and energy density. Among the 2D material family for SIBs, the black phosphorus material was thought to work according to an alloying mechanism and thus possesses a high specific capacity. Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) accommodate sodium ions based on the conversion mechanisms and deliver a relatively high specific capacity. Other 2D materials such as 2D carbon materials and MXenes mainly show the ion intercalation mechanism. Generally, the ion intercalation mechanism contributes to a good cycling stability yet a relatively low specific capacity, while the alloying and conversion mechanisms afford a high specific capacity yet relatively inferior cycling stability. Factors such as the interlayer spacing, conductivity, surface charge density, and surface functional group of 2D materials influence the battery performances of 2D materials. According to the mechanisms of SIBs, anode materials can be mainly divided into three types including intercalation/adsorption, alloying, and conversion. Except for the intrinsic material property, the structure of the material also exhibits a great influence on the electrochemical performance. Among current anode materials, 2D materials have achieved a broad application in energy-related fields due to their unique physical and chemical properties.28,29 The ion mass transfer process in SIBs mainly involves the steps of ion de-insertion from the cathode, diffusion in the electrolyte, transfer across the electrolyte/anode interface, and insertion into the anode. Ion mass transfer is thought to be a critical control step for the battery behavior because it is kinetically much slower than the electron transfer, thus influencing the rate performance and energy density, especially under the condition of large loading mass (corresponding to the thick electrode). The rate and direction of ion diffusion determine the ion mass transport state in battery devices and are related to two mutual issues, namely the rate performance of battery and the uniformity of metal anode deposition for metal batteries. Modulation of the ion mass transport behavior to achieve fast and uniform ion transport can reduce the concentration polarization, achieve the superior utilization of electrode materials, and promote the uniform metal deposition, which is conducive to fast-charging capability and stable metal anode. Compared with other materials, 2D materials exhibit multiple merits in terms of physicochemical properties. The abundant functional group, adjustable interlayer spacing, and the superior chemical stability of 2D materials could promote the sodium-ion storage. The large specific surface area and open surface enable the 2D material to expose more active sites to enhance sodium storage capacity, and the good flexibility and mechanical properties provide superior structural stability during the sodium-ion storage process. 2D materials have higher electron transport efficiency compared to 1D materials. These advantages of chemical and physical properties make 2D materials convenient for efficient mass transfer and storage of sodium ions with large size. These unique properties can not only promote the ion mass transfer via reinforcing the surface wetting behavior but also generate more accessible reactive sites.30,31 Moreover, 2D materials can shorten the diffusion path of sodium ions and achieve enhanced electrochemical performance.32,33 2D materials have been widely investigated for addressing the dendrite problems in metal batteries due to their excellent electrical conductivity and mechanical flexibility. For example, the graphene substrate can be used as a nucleation template to guide the horizontal growth of zinc metal and effectively inhibit the growth of zinc dendrites. Other than acting as a nucleation template, graphene can also be used as a physical constraint to reduce the formation of dendrites by reducing the current density and enhancing the affinity. Therefore, according to the special structure and unique advantages of 2D materials, new electrode materials can be designed to enhance the battery performance of SIBs.

Herein, the research progress of 2D materials as anode materials for SIBs is reviewed (Figure 2). We first introduce the 2D carbon materials as the anode of SIBs, which involves the difficulty of graphitic carbon in sodium storage and the requirement for high-performance carbon materials. It then presents the preparation methods of TMDs and the corresponding strategies for sodium storage by nanostructure engineering, interlayer spacing expansion, and atomic vacancy construction. After that, the mechanism of black phosphorus in sodium storage is discussed. The following section presents the vital role of MXenes and layered double hydroxides (LDHs) in SIBs through structure engineering, which involves providing more active sites, increasing the ion diffusion rate, and constructing the conductive matrix. Finally, the challenges and prospects for the application of 2D materials in anode materials of SIBs are presented.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram summarizing the application of 2D materials in SIBs, ranging from material chemistry to structure and electrochemistry

2D carbon materials

2D carbon materials have been widely employed in metal-ion batteries benefitting from their chemical stability, electrical conductivity, 2D open structure, and high specific surface area.34 Meanwhile, it also has disadvantages, for example, the graphitic structure is not conducive to the intercalation and diffusion of the "fat" sodium ion. This section carefully presents the challenges of traditional graphitic 2D carbon materials in accommodating sodium ions and discusses the promising solutions in terms of interlayer expansion and ion-solvent co-intercalation.

Challenges of using graphitic carbon as anode for SIBs

Compared with other carbon materials, graphitic carbon possesses a higher specific capacity (theoretical value: 372 mAh g-1) for lithium storage, promoting its substantial success in commercial LIBs. The intercalation compound (LiC6) can be formed by the reversible intercalation and desorption of lithium between graphite layers.35 However, this performance value is sharply discounted in of SIBs. From the perspective of dynamic, the graphitic interlayer spacing (0.34 nm) is too small to accommodate larger sodium ions, which requires expanding the interlayer spacing (Figures 3A–3C).36 Although a small amount of sodium can enter into the pure graphite layer through electrochemical reaction and form NaCx by heating the metal sodium in a vacuum environment, the amount of sodium embedded in the graphitic layer is far less than that of lithium.37 This is because that it is difficult to form the sodium-graphite intercalation compounds (Na-GICs) between sodium ions and graphite.38 Density functional theory (DFT) calculation showed that sodium exhibits a much higher energy barrier of reacting with graphite to form NaC6 compared with lithium.39 In addition, it was also found that Na intercalation compounds (NaC6 and NaC8) are difficult to form due to the high redox potential of Na/Na+.40 The instability of sodium ions in graphitic interlayer could be possibly elucidated using three factors that have an impact on the formation of alkali metal-graphite intercalation compounds (AM-GICs) (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs) as shown in Figure 3D.37 Since the AM-GICs were composed of metal and graphene, the structural deviation of AM and graphite from their pristine state had a large impact on the total electric field effect. In additional, the need for partial metal depolymerization or graphite deformation to absorb energy should be considered. Moreover, the formation of AM-GICs involves local interactions between monolayer graphene and AM. 2D graphene sheets tend to be stacked to form a layered microstructure parallel to the substrate, especially when being compressed during the electrode preparation. This may influence the battery performance through hindering the efficient ion mass transfer due to the reduced surface area of the electrodes. Several approaches have been developed to addressing this problem. One can introduce the electrostatic repulsion interaction between the adjacent 2D graphene by chemically tuning the surface charge of graphene. Another approach refers to insert molecular or spacer materials to prevent the stacking of graphene sheets.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of sodium storage in graphite-based materials

(A) Comparison of the Na+ intercalation in (A) graphite, (B) graphite oxide, and (C) expanded graphite. Reproduced with permission from,36 © Springer Nature Limited 2014.

(D) Contributing factors to the formation energy of AM-GICs. Reproduced with permission from,38 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2016.

Broadening interlayer spacing

As mentioned previously, graphitic carbon is not conducive to sodium storage, which can be addressed by expanding the layer spacing of graphitic carbon. As an easily graphitized aromatic compound precursor, pitch was used to construct mutually cross-linked 2D carbon nanosheets through polymerization reaction, and the interlayer spacing is 0.381 nm.41 The high-temperature NH3 treatment of pitch could also increase the interlayer distance of carbon materials.42 Chain-like H2N(CH2)xNH2 was locked between graphene oxide (GO) sheets through a dehydration condensation reaction to enlarge the interlayer spacing of graphene.43 By intercalating metal pillars, the graphene interlayer spacing was increased to facilitate the intercalation of Na+.44,45 In addition, many studies reveal that the introduction of defects and heteroatoms into the graphene layer can effectively induce the formation of a large number of active sites, which change the structures of graphene on the surface and edge (Figure 4A). The existence of defects was theoretically shown to be beneficial to the sodium storage,46,47,48 for example, fluorine (F)-doped carbon materials can react with Na to form NaF to form a consolidated solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) and alleviate volume expansion.49 N doping may lead to external defects and adjust the conductivity of the intrinsic electronic state.50 The electronegativity of N (Pauling scale of 3.04) is greater than that of C (Pauling scale of 2.55), thus N doping can induce polarization in the carbon network. N-doped graphene foams (N-GFs) were prepared by annealing the freeze-dried graphene oxide foams in NH3 gas.51 It could be seen that the characteristic peak (002) of graphitic carbon appears in N-GF at 26.0°, and the interlayer distance (d-spacing) was 0.342 nm, which was slightly larger than that of graphite (Figure 4B). When used as the SIBs anodes, N-GFs exhibited a specific capacity of 852.6 mAh g-1 at the current density of 500 mA g-1 in the voltage window of 0.02–3.00 V. Defects induced by N doping are thought to accelerate the diffusion of large sodium ions, enhance the storage capacity, and reduce the effect of volume expansion. A series of N-rich few-layer graphene with expanded interlayer spacing ranging from 0.45 to 0.51 nm were successfully synthesized as an anode for SIBs.52 Generally, the as-doped N atoms could be divided into three different types according to the bond environment with carbon: pyrrole N (N-5), pyridine N (N-6), and quaternary N (N-Q). Different types of N atoms have different effects on electrochemical performance, where N-5 and N-6 could effectively absorb sodium ions, enhancing the sodium storage capacity. N-q can cause negative electron-rich states, while pyridine N and pyridine N located in vacant positions break the stable π-orbital resonance and form a positive electron-rich state. The distortion of these electron states improves the electrical conductivity and chemical activity of the electrons, thus enhancing the sodium storage performance.

Figure 4.

Heteroatom doping promotes the sodium storage using in 2D carbon materials

(A) Schematic diagram of graphene with expanded interlayer spacing by the pillar effect and doping.

(B) XRD patterns of the N-G, rGF, and N-GF,51 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2018.

(C) The relative intensity profile for the line scan across the lattice fringes of the NS-GNS,53 © Elsevier B.V. 2018.

(D) The interlayer spacing of NOP-CN.

(E) Long-term cyclic performance of NOP-CN at different current densities. Reproduced with permission from,54 © Elsevier Ltd. 2020.

S atom with much larger radius than nitrogen can increase the interlayer distance of 2D carbon materials. S-doped graphene (S-SG) derived from sol-gel is prepared as anode material for SIBs.55 S-SG has a highly disordered structure, a large interlayer distance (0.41 nm), and abundant active sites (Figure 4C). These contribute to a high reversible capacity of 380 mAh g-1 after 300 cycles at 100 mA g-1, an excellent rate performance of 217 mAh g-1 at a particularly high current density of 3.2 A g-1, and superior cycling performance of 263 mAh g-1 at 2.0 A g-1 over 1,000 cycles. Recently, S-doped curly graphitic carbon nanosheets were synthesized with a controllable interlayer spacing range from 0.38 to 0.41 nm by utilizing sodium dodecyl sulfate as sulfur resource and graphitization additive.56 There are mainly three configurations of S-doped carbon, namely C-S-C, C-SOx-C (x = 2, 3, 4), and C-SH, and the presence of these configurations can make larger layer spacing. Compared with N and S, P has a larger atomic radius and lower electronegativity, which usually provides electrons to form chemical bonds in carbon. In addition, P has low electronegativity and high electron donor ability. Therefore, it is a promising candidate as a carbon dopant to improve the electrochemical performance. For example, P-doped 2D carbon nanosheets could be prepared by thermally treating carbon dots with NaH2PO4.57 The interlayer distance was enlarged by transforming carbon dots into large-area phosphorus-doped carbon nanosheets (P-CNSs). The P-CNSs electrode delivered a high capacity of 321.2 mAh g-1 over 100 cycles at 0.1 A g-1.

Compared with the doping strategy of single heteroatom, multi-heteroatom doping in carbon materials is another approach to achieving high-performance SIBs according to the synergistic effects among different heteroatoms with different electronic structures. Enormous efforts have been made in the graphite doping with two or three different heteroatoms. It has been proved that multi-heteroatom doping can produce a synergistic effect between heteroatoms with the carbon framework, thus improving the corresponding physical or chemical properties.58 For example, N and S co-doped graphene nanosheets (NS-GNSs) were prepared with high doping by a simple one-pot method.53 In the pyrolysis process, the starting material could form the planar sacrificial template needed for the growth of a 2D graphene structure, and it could be in situ transformed into abundant N and S dopants, which successfully solved the general problem of high doping of multiple heteroatoms into graphene matrix. The electrochemical redox centers induced by N and S are placed at different potentials. The NS-GNS electrode has a high reversible capacity of about 400 mAh g-1, which is even higher than the theoretical value (372 mAh g-1) of lithium storage in graphite. This provides a direction for enhancing the energy storage of graphene materials and meanwhile serves as a low-cost and scalable method with adjustable characteristics for large-scale production of well-defined graphene materials. N, O, P co-doped carbon network54 was synthesized through simple calcination (Figure 4D), which has a larger graphite layer spacing (0.407 nm). As an anode material for SIBs, it exhibited good cycling stability and rate capability, with a specific capacity of 181.1 mAh g-1 at 1 A g-1 and 119.1 mAh g-1 at 5 A g-1 after 2,000 cycles (Figure 4E). According to the first-principles computations, compared with diatomic (N, O) doping, the introduction of P atoms demonstrates multiple merits of enhancing the conductivity of the carbon structure, distorting the graphite layer, producing more active center defects, increasing the graphite layer spacing, and providing a fast transport channel for sodium ions. Other 2D carbon-based materials, including C3N4, graphdiyne59,60 and covalent organic frameworks61 were also used as anodes for SIBs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of 2D carbon-based materials as anodes for SIBs

| 2D-carbon materials | Specific capacities (mAh g-1) | Current density (A g-1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3DM-GO | 158.1 | 0.1 | Zhang et al.43 |

| N-GF | 1057 | 0.1 | Xu et al.51 |

| N-FLG | 211.3 | 0.5 | Liu et al.52 |

| S-SG | 380 | 0.1 | Quan et al.55 |

| SGCN | 321.8 | 0.1 | Zou et al.56 |

| P-CNSs | 328 | 0.1 | Hou et al.57 |

| NS-GNS | 400 | 0.03 | Ma et al.53 |

| NOP-CN | 341.3 | 0.05 | Chen et al.54 |

| Crystalline C3N4/C | 286 | 0.05 | Sun et al.62 |

| g-C3N4/graphite | 202 | 1 | Shi et al.63 |

| GDY-NS | 812 | 0.05 | Wang et al.64 |

| Boron-graphdiyne | 180 | 5 | Wang et al.65 |

| C/g-C3N4 | 254 | 0.1 | Weng et al.66 |

| Layered graphdiyne | 1237 | – | Huang et al.67 |

| HsGDY | 700 | 1 | He et al.68 |

| TFPB-TAPT COF | 246 | 0.03 | Patra et al.69 |

| Sb@NGA-CMP | 344 | 1 | Xie et al.70 |

Ion-solvent co-intercalation

Ion-solvent co-intercalation is another effective approach to Na+ intercalation into graphite with the assistance of appropriate solvent molecules. For instance, according to the weight change test and energy dispersive X-ray spectrum analysis, the co-intercalation was achieved at the ratio of dimer molecule to Na+ of 1:1.71 The triggering conditions of intercalation reaction in electrochemical cells were described using DFT calculation,72,73 which revealed that the reversible sodium intercalation in graphite is possible only under specific electrolyte conditions associated with the solvation energy of the Na+ solvent and the lowest level of unoccupied molecular orbital of the solvating complex. Goktas et al. revealed the temperature-dependent effect of several solvents such as crown ethers, where ion-solvent co-intercalation could only be achieved at high temperatures rather than room temperature.72 In addition, the co-intercalation in graphite proceeds rapidly, accompanied by the growth of a very thin SEI.

Despite the function in assisting the intercalation, ion-solvent co-intercalation usually leads to the loss of the initial capacity. It was proposed that the solvent molecules supporting the reversible formation of ternary graphite intercalation compounds (t-GICs) must have a high solvation energy with cations and a high reduction stability.73 The reduction stabilities of diglyme, ethylene carbonate, and dimethyl carbonate molecules and ions are provided in Figure 5A. The calculated electron affinity of diglyme solvent is significantly higher than that of all other solvents, which proves that it has a high reduction stability and can be co-intercalated without reduction. After [Na-(carbonate)2]+ receives an electron, the carbonate solvent will be reduced and deformed. In addition, the incorporation of inorganic substances can reduce the formation barrier of [Na-(diglyme)]+ co-intercalation chemistry. Compared to polyvinylidene fluoride, sodium alginate could provide a more stable Coulombic efficiency (CE) of graphite electrodes (Figure 5B). A schematic illustration of solvated sodium ion co-intercalation into graphite galleries is shown in Figure 5C.74 The solvent activity of t-GICs and electrolytes can be tuned up to 0.38 V by adjusting the parameters of the solvent species, the concentration of electrolytes, and the temperature. Yoon et al.38 also studied the interaction between alkali metal ions, solvents, and graphite. The results reveal that the unstable formation of Na-GICs was caused by the local repulsion between Na+ and graphene. The co-intercalation of Na+ and solvent molecules can significantly reduce this repulsion, thus inhibiting the direct interaction between Na+ and graphene. The electrochemical behaviors of various solvents, including linear/cyclic ethers and carbonates, were investigated. It was found that only linear ethers and their derivatives could be intercalated into graphite (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Ion-solvent co-intercalation in 2D carbon materials

(A) solvation sheath of Na+ in diglyme.

(B) Capacity and Coulombic efficiency of graphite with SA binder at various rates. Reproduced with permission from,73 © Elsevier B.V. 2019.

(C) Schematic illustration of the solvated Na ion co-intercalation into graphite galleries. Reproduced with permission from,74 © Springer Nature Limited 2019.

(D) The solvent species used to investigate the solvent dependency of the intercalation phenomenon (DME: ethylene glycol dimethyl ether, DEGDME: diethylene glycol dimethyl ether, TEGDME: tetramethylene glycol dimethyl ether, THF: tetrahydrofuran, DOL: dioxolane, DMC: dimethyl carbonate, DEC: diethyl carbonate, EC: ethylene carbonate, PC: propylene carbonate). Reproduced with permission from,38 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2016.

Other than the aforementioned progress made in using 2D carbon material for hosting sodium ions, there are still challenges regarding the unsatisfactory battery performance. First, low specific capacity and high intercalation potential will reduce the energy density of the whole battery system. Second, the solvent molecules in the interlayer will lead to the consumption of electrolyte solvent, inducing the increase of resistance and gradually depleting the limited electrolyte. In addition, the volume expansion (∼350%) caused by the co-intercalation behavior will lead to the pulverization of graphite particles, resulting in the degradation of cycling performance.

2D TMDs

2D TMDs have been widely explored in sodium storage because of their high capacity, electronic properties, and high specific surface area.75,76,77 For example, SnS2 possesses a high theoretical capacity of 1,135 mAh g-1 in SIBs, which is much larger than that of the hard carbon anodes in SIBs. Compared with active metals and the corresponding oxides, TMD exhibits a small volume change, good reversibility, and large initial CE. In addition, the discharge product (Na2X) produced from TMD has better conductivity than the other discharge product (Na2O). Moreover, the M-X bond in TMD is weaker than the M-O bond, favoring the conversion reaction kinetics.

Synthetic strategies

Hydrothermal and solvothermal methods

Hydrothermal and solvothermal reactions are low-cost and environment-friendly methods for synthesizing nanomaterials with narrow particle size distribution and high phase purity. These methods are also widely used to prepare TMD materials with controllable morphology and size. For instance, SnS2@CoS2-rGO composite (Figure 6A),78 monodisperse SnS2@SnO2 heterogeneous nanoflowers,79 bowl-like SnS2,80 SnS2 nanosheets, MoS2/graphite paper, and 1T-phase MoS2 have been successfully synthesized using hydrothermal or solvothermal methods.

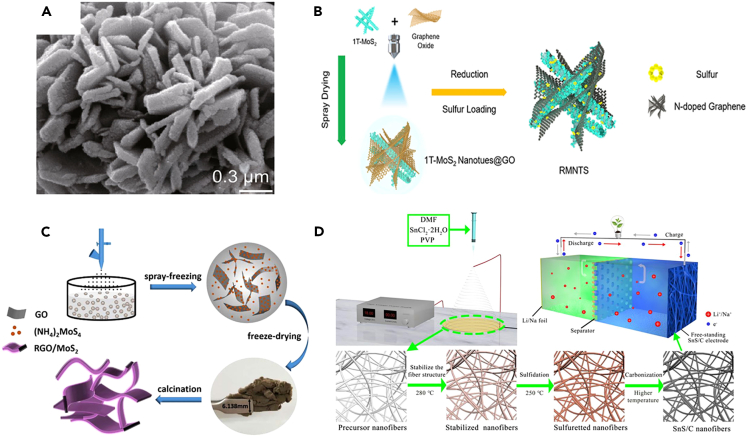

Figure 6.

Preparation methods of 2D TMD for sodium storage

(A) SEM image of SnS2@CoS2-rGO composite. Reproduced with permission from,78 ©Springer Nature Limited 2018.

(B) Schematic diagram of the synthetic procedure of the GMNTS. Reproduced with permission from,81 © Elsevier B.V. 2019.

(C) Schematic illustration of 3D interconnected architecture of RGO/MoS2. Reproduced with permission from,82 © Elsevier B.V. 2017.

(D) Schematic diagram of the synthesis of SnS/C nanofibers. Reproduced with permission from,83 © Elsevier B.V. 2018.

Spray-related method

Spray-related methods mainly consist of spray pyrolysis, spray drying, and spray freezing. For example, three-dimensional (3D) MoS2 and graphene microspheres were prepared by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis using polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles, GO, and (NH4)2MoS4 as raw materials. The size of graphene nanospheres could be easily controlled by changing the size of the PS nanospheres template used in spray solutions. The thickness of the graphene sheet and MoS2 layer was controlled by changing the concentration of graphene oxide and MoS2 precursor in the spray solution. Therefore, spray pyrolysis can reasonably control the size and thickness of the target product. N-doped graphene-coated vertically aligned 1T-MoS2 nanotube was prepared by spray-drying method (Figure 6B).81 This spray-drying method could effectively synthesize nanostructured materials and achieve efficient electrolyte penetration and ion transfer. Another case is the spray-freezing approach, which could be used to prepare the hybrids of reduced GO (rGO) and MoS2 (Figure 6C).82 Liquid nitrogen spray freezing could rapidly freeze the precursor droplets and avoid the phase separation and re-stack of MoS2 and rGO films, generating a porous 3D structure after annealing. This hierarchical porous structure made up of 2D materials could promote the efficient diffusion of Na+.84,85

Other methods

In addition, there are also some other effective synthesis methods for 2D TMD with different structures. Specifically, electrospinning technology is a frequently used method for producing flexible film-based nanofibers with unique characteristics. Free-standing flexible SnS/C nanofibers were prepared by electrospinning, which showed a good performance of maintaining 481 mAh g-1 after 100 cycles at 50 mA g-1 (Figure 6D).83 Mechanochemical synthesis is a fast, economical, and environment-friendly method without the use of solvents, surfactants, high reaction temperatures, or any purification steps. The reaction takes place through the mechanical interaction between atoms, exerts interaction through shear, compression, and friction, and allows effective and large-scale production. SnS/C nanocomposites are prepared by the mechanochemical method, which shows a low size and is well coated by carbon particles.86 The solid-state method refers to a synthesis method in which the reactant is a solid substance, demonstrating the advantages of high selectivity, high yield, and simple operation. The SnS2/C composite was synthesized via a facile solid-state reaction in a sealed glass tube under vacuum, achieving a large interlayer distance and effectively alleviating volume change for a better cycling stability.

Carbon-based 2D TMDs composites

2D TMD demonstrates large capacities in sodium storage whereas the low intrinsic conductivity and structural instability still impede the further development.87 To this end, a variety of strategies have been proposed, including combining TMD with conductive polymers or carbon materials to improve the conductivity and structural integrity. Last 10 years have witnessed the rapid development of design and synthesis of heterostructures composed of TMD and carbon materials, such as rGO and carbon nanotubes (CNTs). For example, a flexible 3D porous graphene nanoflake/SnS2 (3D GNS/SnS2) film as a high-performance SIBs electrode was established onto the assembly of GNS/SnS2 blocks, realizing a fast electron/ion mass transfer (Figure 7A).88 In addition, the chemical integration of SnS2 nanocrystals with GNS provided enough active sites for sodium storage and affords superior cycling stability as well. The flexible 3D GNS/SnS2 films thus exhibited a high area capacity of 2.45 mAh cm-2, high-rate performance, and excellent stability.

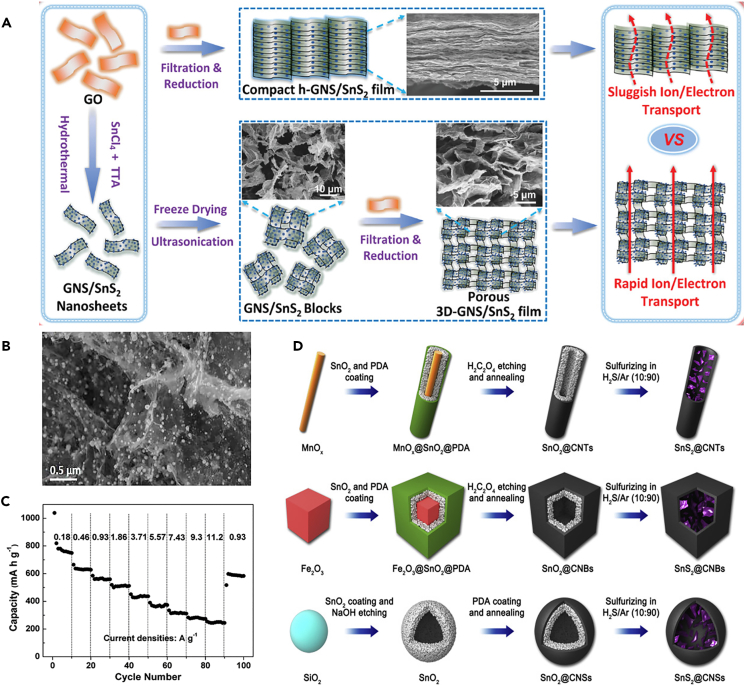

Figure 7.

The integration of 2D TMD with carbon materials for sodium storage

(A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of the porous 3D-GNS/SnS2 film and the comparative h-GNS/SnS2 films. Reproduced with permission from,88 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2020.

(B) SEM images of SnS2@3DRGO composite. Reproduced with permission from,89 © Elsevier B.V. 2018.

(C) The discharge capacities of the SnS2 NC/EDA-RGO anode at different current densities from 0.18 to 11.2 A g-1. Reproduced with permission from,90 ©The Royal Society of Chemistry 2016.

(D) Schematic illustration of the synthesis processes of SnS2@CNTs, SnS2@CNBs, and SnS2@CNSs. Reproduced with permission from,91 © Elsevier Inc. 2018.

rGO possessing good conductivity, large surface area, and outstanding flexibility can be used as supporting materials for TMD, effectively strengthening electrical conductivity, preventing polymerization, and buffering mechanical changes. The design of TMD-rGO heterostructures for reversible storage is based on the following material principles: 1) larger interlayer spacing is favorable for ion mass transfer in 2D-layered TMD and the buffer space is favorable for regulating the host volume change during the cycle; 2) constructing conductive network is beneficial to address the impedance and polarization issues; and 3) preventing the aggregation of TMD could promote the contact between electrode and electrolyte. Inspired by these principles, a wet chemical process was proposed to couple SnS2 nanoparticles with 3D rGO, generating a high specific capacity and good cycling stability (Figure 7B).89 SnS2 nanoparticles were well immobilized by graphene due to the electrostatic adhesion of [SnS3]2− on phthalic diglycol diacrylate-functionalized GO. A mild amine thermal reaction was proposed by experimental and theoretical investigations, which was convenient and effective for the large-scale preparation of SnS2-based 2D TMD (Figure 7C).90 The strong chemical interaction between SnS2 and NC/EDA-rGO interface originates from the interaction between EDA bridging nanocrystals and nanochips, which could effectively enhance the physical-chemical interaction. CNTs are considered as a promising carbon carrier due to their hollow structure, high electrical and thermal conductivity, and good mechanical strength, which can improve the conductivity and ion diffusion rate and effectively buffer the volume expansion during cycling of SnS2. SnS2@CNTs and SnS2/NS CNTs were synthesized through a simple template method and UV-initiated polymerization, respectively (Figure 7D).91

Despite the similar battery intercalation chemistry, Na+ suffers from a sluggish kinetic because of the larger radius compared with Li+, which matters fundamentally along the pathway of anode design of SIBs. Learning from the structure of 2D TMD, the application of material chemistry and molecular chemical engineering is particularly important to reduce alloying strain, increase the surface area of materials, and shorten the ion mass transfer distance. The carbon materials can be used as the substrate, skeleton, and coating layer for improving the electrical conductivity. Furthermore, it can be chemically modified to strengthen the anchoring action of TMD and provide more active sites.

Other sodium storage reinforcement strategies

TMD anodes share an identical reaction of generating the product of Na2S and exhibit huge differences as well. For example, the electrode reaction of MoS2 end up with forming Na2S and Mo, while SnS2/SnS can further proceed to generate the Na-Sn alloy. Other than the integration with carbon materials, other strategies, such as nanostructure engineering, few-layer TMD, interlayer spacing expansion, and atomic vacancy construction, are summarized and discussed in this section for guiding the application of TMD in SIBs.

Nanostructure engineering

The sodiation process is studied to be a kinetics sluggish process, especially at high current density. A common strategy for improving the mass transfer of sodium is nanostructure engineering, which involves preparing TMD into different structures such as nanorod,92 nanosheet,93,94 nanowall,95 and quantum dot.96 In situ electron diffraction and DFT calculation were used to study the sodium reaction of MoS2 nanosheets and determine the phase transition in the process of sodium reaction.97 Several thermodynamically stable/metastable structures have been found in the sodiation process of MoS2 nanosheets, which was absent in the bulky MoS2. With the gradual Na+ insertion into MO4+, the Mo-S polyhedron transformed from a triangular prism to an octahedron at about 0.375 Na (Na0.375MoS2) per insertion. When the content of Na was greater than 1.75 of each MoS2 structural unit (Na1.75MoS2), the MoS2-layered structure collapses and the insertion reaction was replaced by an irreversible conversion reaction to form Na2S and Mo nanoparticles. 1T MoS2 nanosheets were directly used as anode materials for SIBs.97 Interestingly, 1T MoS2 nanosheets show a high capacity of 450 mAh g-1 at 50 mA g-1, which was much better than that of the 2H phase. DFT calculations showed that, compared with 2H phase, 1T MoS2 had more sodium affinity and faster sodium mobility. In addition, 1T MoS2 could inhibit the dissolution of S species.

Few-layer TMD

Theoretically, when the diffusion time (t) is proportional to the diffusion length (L), the diffusion coefficient (D) is constant (t ≈ L2/D). Therefore, if L is shorter, the reversible reaction of sodium can be stored in less time. Several layers of MoS2 nanosheets were successfully synthesized using a simple and scalable ultrasonic stripping technique,98 the thickness of which was about 10 nm measured by atomic force microscopy. An innovative design strategy was used to enhance the reversible Na+ intercalation by covalently doping S atoms to a transition metal sulfides and graphene sheets (Figure 8A).99 This not only maintained a 2D open framework, but also provided a robust microstructure, where TMDs were firmly fixed on the graphene surface. In addition, the heterogeneous interface anchoring effect between the two components provides a synergistic bridging coupling of the doped S atoms, which plays a key role in promoting the electrochemical stability and kinetics. A controllable and simple strategy to fabricate a small layer of MoS2 with in situ conversion of nitrogen-doped carbon (MoS2/NC) was reported.100 In the synthesis process, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) was used to form emulsion. Chemical bonding (C-S) and in situ conversion of nitrogen-doped carbon (1.5-MoS2/NC) could be synthesized by controlling the weight ratio of MoO42− and CTAB. A simple and reliable synthesis strategy for in situ growth of MoS2 nanosheets on rGO cross-linked hollow carbon spheres (HCS) was prepared to prepare a 3D network nanohybrid (MoS2 RGO/HCS) (Figure 8B).101 Systematic electrochemical studies showed that the reversible capacity of MoS2 RGO/HCS can be maintained at 443 mAh g-1 after 500 cycles at 1 A g-1 for SIBs, due to its 3D porous structure for shortening the ion diffusion path and improving the diffusion mobility of Na+.

Figure 8.

Design strategies for MoS2 to promote the storage sodium performance

(A) The schematic of few-layered MoS2/S-doped graphene composites. Reproduced with permission from,99 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. 2017.

(B) Schematic illustration of the formation process of MoS2-rGO/HCS. Reproduced with permission from,101 © American Chemical Society 2018.

(C) The pathways of the lowest Na+ diffusion barrier across MoS2 with one vacancy, two vacancies, and their corresponding potential energy curves. The purple, yellow, and green balls represent Mo, S, and Na, respectively. Reproduced with permission from,102 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2019.

(D) Schematic diagram showing the synthesis of HMF-MoS2 with Mo vacancies. Reproduced with permission from,103 © American Chemical Society 2019.

Interlayer spacing expansion

The design of a few-layer structures with enlarged layer spacing is conducive to the efficient ion and electron mass transfer through shortening the ion diffusion distance and reinforcing the contact between active substance and electrolyte. For instance, ultra-wide interlayer spacing of MoS2 nanoflowers (nearly twice as large as the original MoS2) on carbon fiber were prepared to realize an ultra-long cycling stability and superior rate capacity of 104 mAh g-1 at 20 A g-1 after 3,000 cycles.104 Interface engineering strategy is an effective way for the growth of TMD with expanded interlayer spacing.105 Meanwhile, the intercalation for host’s interlayer expansion as a general strategy was reported to promote the solid-state diffusion of Na ions.106 In this process, poly(ethylene oxide) was intercalated into MoS2 interlayer by stripping and refilling, widening the interlayer spacing of MoS2 from 0.615 to 1.45 nm, which was 100% larger than that of commercial MoS2. The selection of raw materials and solvents plays an important role in the regulation of MoS2 morphology. A series of MoS2 nanosheets (dozens layered MoS2 nanosheets: DL-MoS2; few-layer MoS2 nanosheets: FL-MoS2; ultra-small MoS2 nanosheets: US-MoS2) were anchored onto N-doped graphene sheets by a solvothermal method.107 By selecting different raw materials and solvents, the morphology of the synthesized MoS2 nanosheets, including size, number of layers, and layer spacing, could be accurately controlled.

Atomic vacancy construction

The integration of TMD with carbon nanomaterial is an effective method to stabilize TMD, which usually suffers from side reactions and low energy density due to the large surface area and volume of carbon nanomaterial. How to break through the limitation of 2D materials to achieve rapid Na+ insertion/extraction and electrochemical reversibility remains a challenge. Atomic vacancy construction provides a good solution to address these challenges faced by TMD. For instance, a vacancy-rich MoS2 with the unique architecture of bundled defect was synthesized, which achieved a low activation energy barrier of Na+ mass transfer across the defective MoS2 plane (Figure 8C).102 Electrospinning technology was used to prepare sulfurized polyacrylonitrile (SPAN) fibers with defects embedded in molybdenum disulfide nanocrystals.108 With this unique structure, the MoS2 nanolayer and sulfur nanodots are installed inside span fiber, providing multiple and short-range channels for sodium ions to ensure rapid kinetics. Moreover, a strategy of secondary sulfidation combined with a simple selective etching method was developed to fabricate hollow micro cubic frameworks constructed from mode effect-rich ultra-thin MoS2 nanosheets (Figure 8D).103 After the introduction of Mo vacancies, not only the energy gap between the valence band and the conduction band is narrowed, but also the Fermi level is crossed, which improves the conductivity.

The stability of TMD materials is relatively poor during the long-term cycling process, especially with respect to the commonly used carbonate-based electrolytes. Most of the reported TMD anode materials need to be used in combination with carbon materials to improve the conductivity and structure/chemical stability. Despite the high specific capacity of TMD, the relatively high working potential as anode material for SIBs will lower the energy density of the battery device. Thus, finding suitable TMD materials or developing advanced regulation strategies toward reducing the working potential plays a significant role for the practical use of TMDs in SIBs.

Other 2D materials for SIBs

Black phosphorus

Phosphorus demonstrates great potential as a high-capacity conversion-type anode for SIBs according to the reaction with sodium to form Na3P. DFT calculation shows that the adsorption energy of a single Na is negative, which indicates that the interaction between Na and phosphorene is thermodynamically favorable.33 There are three types of phosphorus: white phosphorus, red phosphorus, and black phosphorus (BP), whereas white phosphorus is excluded from the range of SIBs anode due to its high reactivity. Here, we mainly focus on BP which is a typical 2D material with multiple merits of thermodynamic stability, nonflammability, and insolubility in most solvents. Moreover, it has a layered structure and high conductivity (102 s m-1),109 which is a good choice for anode materials in SIBs. BP has a folded layered structure, which can be peeled into a single layer or a multi-layer BP, known as phosphorene.110

In recent years, BP has been considered as one of the most promising anodes because of its high sodium storage capacity, layered structure, and suitable operating potential. Many theoretical studies have focused on the single-layer phosphorene as the anode material of SIBs.33,111 It was found that the diffusion of Na on the phosphorene was ultrafast and anisotropic, which endowed BP with a good electrochemical response. The Na accommodation mechanism in BP was proposed to follow the alkalization behavior (Figure 9A).111 Specifically, the alkalization of BP was the formation of Na0.25P by layer insertion, and then alkalization further leads to the breakage of the P-P bond, finally forming the amorphous NaXP, accompanied by large volume expansion. Thus, it is essential to maintain the layered structure of BP to sustain a stable performance. However, such a layered structure may suffer from electrolyte molecule intercalation, resulting in the exfoliation of the layered structure. The storage of sodium ions in BP based on two different reaction mechanisms was proposed (Figure 9B), namely intercalation (1.50–0.54 V vs. Na/Na+) and alloying (0.54–0.00 V vs. Na/Na+).112 The electrochemical intercalation of lithium and sodium was studied by in situ transmission electron microscopy. Despite the same intercalation channels along the [100] (z-zag) direction, there was an obvious anisotropic behavior, that is, Li ions activated the lateral intercalation along the [010] (armchair) direction to form an overall uniform propagation, while the diffusion of Na+ in the z-zag channel was limited, resulting in the columnar intercalation. First-principles calculations showed that the diffusion of Li+ and Na+ along the Z-type direction had favorable energy conditions, while the energy barrier of Na+ increased and could not be overcome, which explains the orientation-dependent sandwich channel. The evolution of chemical state in LixP/NaxP to Li3P/Na3P phase transition was determined by analyzing electron diffraction and energy loss spectrum.113 A chemical mechanical model was established, which incorporated the inherent anisotropic properties into the large elastic-plastic deformation. The coupling of two intrinsic anisotropy was the key factor to control the evolution of BP.114 In particular, the sodium diffusion directivity produces sharp interphase along the [010] and [001] directions, which restricted the anisotropic development of the insertion strain. When initiating the sodiation at different crystal levels, the coupling effect presents a unique stress generation and fracture mechanism.115

Figure 9.

Theoretical insight into the sodium storage mechanism of BP

(A) The sodiation mechanism of black phosphorus. Reproduced with permission from,111 © American Chemical Society 2015.

(B) Schematic diagram showing the sodiation of BP loaded on graphene to form Na3P. Reproduced with permission from,112 © Springer Nature Limited 2015.

Toward the stability issue of BP, the exfoliation of BP to few-layer phosphorene116 and the stacking strategy of 2D materials appear to be the promising directions benefitting from the high conductivity and surface area flexibility. Functional materials containing hybrid BP/graphene (BP/G) heterostructure were prepared by using the interaction of different length scales.29 The heterostructure was self-assembled based on the electrostatic attraction of different 2D materials. The characterization of the deposits formed by this technique illustrates the existence of stacking and sandwiching 2D heterostructures, and the measurement of zeta potential confirms the mechanical interaction-driven assembly. Based on BP’s special ability in the alloy-type sodium storage, these materials have been proved to be excellent free-standing anodes for sodium batteries, with a specific discharge capacity of 2,365 mAh g-1. BP/rGO-layered composite was synthesized by the application of pressure at room temperature and the anodes show a good rate capability (∼1,250 mAh g-1 at 1 A g-1 and ∼640 mAh g-1 at 40 A g-1).117 In addition, a self-assembly process of evaporating the dispersion was reported to proceed with the sandwiching phosphorene and graphene.112 BP and rGO-layered structure electrodes were demonstrated to maintain stability under a pressure of 8 GPa at room temperature (Figure 10A).117 The BP/ketjenblack-multiwalled CNTs (Figure 10B) synthesized by milling show a very high first-time CE (>90%) and high specific capacity (∼1,700 mAh g-1 at 1.3 A g-1).118 Meanwhile, a new BP and multiwalled CNT composite was also prepared via the chemical bonding by surface oxidation.119 Controlled air exposure successfully changed the natural hydrophobic BP powder into ideal hydrophilicity, which is necessary for the stable bonding between BP and functionalized CNTs during ball milling. A high-capacity sulfur-doped BP-TiO2 anode material for SIBs was synthesized by a ball-milling approach (Figure 10C).120 The preparation of materials by ball milling provided an effective method for solving problems such as easy oxidation of BP and mass production. Using BP quantum dots and Ti3C2 nanosheets (TNSs) as batteries and pseudocapacitive elements, a new dual-model energy storage mechanism for Na-ion batteries was constructed (Figure 10D).121 The P-O-Ti interfacial bond between them further induces atomic charge-polarized pseudocapacitive TNS assemblies that can enhance charge adsorption and efficient interfacial electron transfer, providing higher pseudocapacitance values and fast energy storage.

Figure 10.

The application of BP as anode materials for SIBs

(A) Schematic diagram showing the synthesis of BP/rGO. Reproduced with permission from,117 © American Chemical Society 2018.

(B) Schematic illustration of BPC composite. Reproduced with permission from,118 © American Chemical Society 2016.

(C) Schematic diagram presenting the ball-milling treatment of materials. Reproduced with permission from,120 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2019.

(D) Schematic illustration of the formation of the BPQD/TNS composite. Reproduced with permission from,121 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2018.

2D MXenes-based materials

MXenes are generally synthesized by selectively etching the A layers in MAX (Mn+1AXn) phases, where M represents a transition metal (such as Ti, V, Zr), X is C or N, A is a third or fourth dominant group element, such as Al or Si, and n is an integer (n = 1, 2, 3) (Figure 11A).122 MXenes have three main structures M2X, M3X2, and M4X3 phases (Figure 11B), which consist of hexagonal layers with P63/mmc symmetry.123 Mn +1AXn material is a layer of atoms formed by alternately connecting Mn +1Xn sheets. The M layer has a hexagonal structure similar to graphene, while the atoms in the X layer are located at the center of transition metal atoms, forming octahedrons.124 In the MAX crystal structure, the M-X bond is mainly composed of covalent bonds and ionic bonds with high integration, while the M-A bond of metal is relatively weak.125,126 MXenes have a much larger interlayer spacing than graphite, which allows the easy intercalation/deintercalation of sodium ions.127,128 In addition, the double layer of metal-atom formation is thermodynamically favorable between MXenes interlayer spaces, contributing to a 2-fold theoretical capacity. It proves that MXenes show great potentials in sodium storage.129,130

Figure 11.

MXenes as anodes for SIBs

(A) Atomistic structures of six different crystalline MAX phases.

(B) Structure of MAX phases and the corresponding MXenes,122 © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2020.

Few-layer MXenes

MXenes bring new opportunities for the development of SIBs, because of the large and adjustable interlayer spacing, and metal-like conductivity, which promote the rapid electron transfer and ion diffusion.131 However, the capacity of multilayer MXene is unsatisfactory because of the limited Na+ storage sites and the slow diffusion kinetics.132 It is thought to be solved by exfoliating the bulky MXene into a few-layer one. For example, NaHF2 was used as an etchant to exfoliate MXene to obtain few-layer large Ti3C2Tx sheets (Figure 12A).133 Compared to the Ti3C2Tx bulk prepared by HF, the Ti3C2Tx sheets had a higher conductivity (2.3 × 105 S m-1) and delivered a high capacity of 70 mAh g-1 after 900 cycles at 1 A g-1. This was because that the direct insertion of Na+ into Ti3C2Tx could increase the interlayer spacing to 1.235 nm. An organic solvent-assisted high-energy mechanical ball milling method was used to prepare large-scale delamination of few-layer MXene nanosheets.134 A schematic illustration of the delamination of few-layer Ti3C2Tx nanosheets is shown in Figure 12B. This method effectively prevented the oxidation of MXene and produced a few-layer nanosheet structure, which promotes the rapid electron transfer and Na+ diffusion. A few-layer MXene composite (Ti3C2/NiCo2Se4) was prepared by solvothermal method and solution phase flocculation strategy,135 which avoided the restacking problem of a few-layer Ti3C2 MXene. Meanwhile, the 0D bimetallic selenide NiCo2Se4 nanoparticles as a Na+ reservoir shows high redox activity, contributing to a high reversible capacity and good cycling stability of maintaining 320 mAh g-1 at 0.5 A g-1 after 100 cycles.

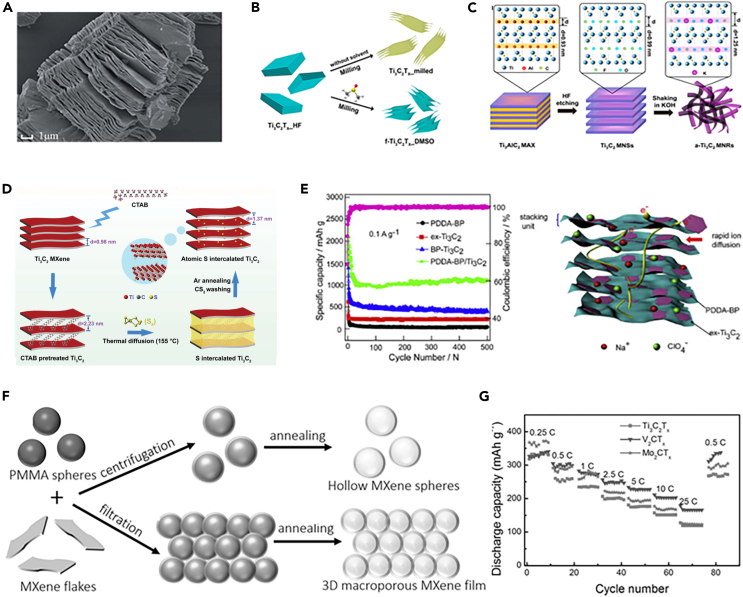

Figure 12.

The application of MXenes in sodium storage

(A) SEM images of Ti3AlC2. Reproduced with permission from,133 © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2021.

(B) Schematic illustration showing the preparation of few-layer Ti3C2Tx nanosheets. Reproduced with permission from,134 © American Chemical Society 2017.

(C) Schematic diagram of the synthesis of a-Ti3C2 MNRs. Reproduced with permission from,136 © Elsevier Ltd. 2017.

(D) Schematic illustration presenting the synthesis process of S atoms intercalated Ti3C2. Reproduced with permission from,137 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2019.

(E) Cycling stability and the charge transfer mechanism of PDDA-BP/Ti3C2 heterostructures. Reproduced with permission from,138 © Elsevier Ltd. 2019.

(F) Schematic diagram of the construction of hollow MXene spheres and 3D macroporous MXene frameworks.

(G) Rate profiles of the 3D macroporous MXene film electrodes for Na-ion storage. Reproduced with permission from,139 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim 2017.

Interlayer spacing expansion of MXene

It has been widely proved that increasing interlayer spacing is an effective strategy to promote the rapid ion diffusion and electrical transport, which can lower the barrier of Na+ mass transfer and buffer the lattice change. For instance, the alkaline Ti3C2 MXene nanobelts were produced by HF etching and KOH treatment for expanding the interlayer spacing to 12.5 Å136 (Figure 12C). Atoms are intercalated into the intermediate layer of MXene to form an ideal intermediate-layer expansion structure. Heteroatoms can form a “pillar effect” between layers of MXenes. For example, S atom was inserted into Ti3C2 MXene (CT-S@Ti3C2) through a simple process including CTAB pretreatment, thermal diffusion of sulfur, followed by annealing (Figure 12D).137 Compared with the bare Ti3C2, S could be easily inserted into the interlayer of Ti3C2 by using CTAB. In addition, the inserted S could interact with Ti atoms at the interface, promoting the formation of the Ti-S bond and thus expanding the interlayer spacing. The reason was that metal sulfides have good dynamic characteristics for sodium-ion storage. In addition, if the S atom was used as an intercalation agent between MXene layers, it would react with intercalated Na+, expanding the interlayer to host Na+. Therefore, using S insertion to enlarge the interlayer spacing of Ti3C2 and forming M-S bonds at the interlayer interface of MXene could improve the sodium-ion storage performance.140 Besides, Ti3C2Tx was directly vulcanized with thiourea to synthesize multilayer S-doped Ti3C2Tx (ST).141 ST well inherits the unique 2D multilayer nanosheet morphology of Ti3C2Tx with a large specific surface area and conductive network, which are conducive to the transport of ions and electrons. S-modified 2D Ti3C2 MXene was constructed by a simple solution immersion method.140 The sulfur-modified Ti3C2 MXene exhibits an impressive long-term cyclic performance of 135 mAh g-1 at the current density of 2 A g-1. MXenes have a large Na+ diffusion coefficient, self enhancement kinetics, and mixed energy storage modes of intercalation and pseudocapacitance.

Generally, increasing the intrinsic activity and atomic charge density via heteroatom doping can enhance the electrochemical performance of 2D materials. As an excellent 2D-layered material, MXenes with increased interlayer spacing show multiple advantages, including a stable and effective sodium diffusion path.142,143 The introduction of other groups significantly enhances the sodium storage capacity,144,145 and shows the mixed energy storage mechanisms.146

Introducing electrochemical active materials into MXene

One of the main problems faced by MXene is the restacking issue induced by the van der Waals interaction and hydrogen bond. This hinders the application of MXene by preventing Na+ from contacting active materials. One method is to combine MXene with other electrochemical active nanomaterials.147,148 The introduction of high-capacity interlayer guests can not only prevent the stacking of MXene nanosheets but also improve the sodium storage capacity. The heterostructure of MXene and BP was reported to display an ultrahigh reversible capacity of 1,112 mAh g-1 after 500 cycles at 0.1 A g-1 because of the confinement of monodispersed BP nanoparticle within Ti3C2 to buffer the volume expansion and prevent the aggregation of MXene (Figure 12E).138 Meanwhile, our group prepared NaTi2(PO4)3 cubes on Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets by a liquid phase transition method (MXene@NTP-C).147 As the anode material of SIBs, MXene@NTP-C showed an excellent rate capacity and remarkable cycle performance. Electrochemical and kinetic analyses showed that this excellent performance was attributed to the dual-mode regulation of sodium on pseudocapacitance-type MXene and battery-type NaTi2(PO4)3. The surface oxidation of MXene led to a decreased electrical conductivity and a passivated reaction interface, which affected the sodium storage performance. However, it was difficult to avoid this undesirable phenomenon in the preparation of micro/nanomaterials by hydro/solvothermal synthesis, reflux, and calcination. This limitation had become one of the key barriers to the fabrication, understanding of the chemistry of MXene-based materials. Our group exploited hydrogen bonding interactions between glucose molecules and oxygen-containing groups of MXene.148 Glucose molecules were converted into hydrothermal carbon by intermolecular polymerization under hydrothermal conditions, followed by a thermal treatment, targeting at constructing a carbon protective layer with good electrical conductivity.

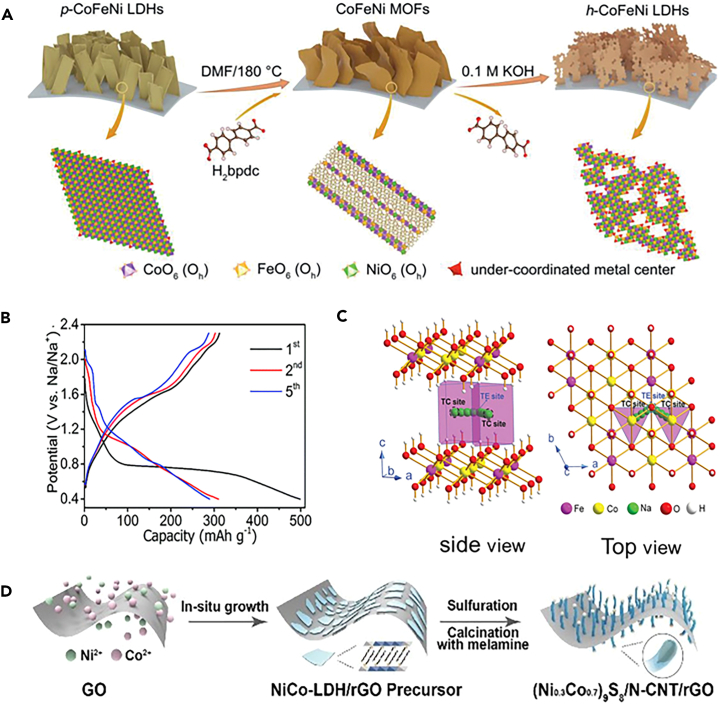

LDHs

LDHs possess larger basal spacing due to the pillaring of interlayer species such as CO32−, NO3−, and organic anions. The general formula of LDHs can be labeled as [M2+1-xM3+x(OH)2]z+(An−)z/n yH2O, where M2+ and M3+ are metal ions with valence states and An− is the interlayer anion that balances the positive charge of the brucite-like host layers.149,150 LDHs structure can be obtained by oxidizing part of divalent metal hydroxide, while the layered structure will not be changed due to the existence of topological properties (Figure 13A).151, The extra charge of the host layer is neutralized by interlayer anions, which are released from an aqueous solution.152,153 The change of metal valence state and ion insertion and removal characteristics in the host layer are consistent with the basic mechanism of the rocking-chair battery. LDHs are thus considered as a promising intercalation-type electrode material for SIBs. Nitrate-pillared CoFe-LDH nanoplatelets were synthesized by a co-precipitation method,152 which has an expanded interlayer spacing of 0.80 nm. Under the voltage window of 0.4–2.3 V, an intercalation-type mechanism takes place, rather than the conversion reaction mechanism in SIBs (Figure 13B). Accompanied by the reversible intercalation/deintercalation of Na+, the CoFe-NO3--LDH undergoes a valence state change of Co2+/Co2−x and Fe2+/Fe3+. Nitrates as pillaring anions not only expand the interlayer space of CoFe-LDH to facilitate the diffusion of Na+ but also enhance the cycling performance by improving the structural stability (Figure 13C). In addition, DFT calculation reveals that the CoFe-NO3--LDH is an excellent Na+ conductor with an extremely low diffusion barrier. In addition, LDHs can be used as a sacrificial template for other materials.153,154,155 In this way, the high specific surface area and 2D structure of LDH can be inherited, which is conducive to the reversible insertion/extraction of sodium ions.156,157,158 For example, sulfur-doped mesoporous amorphous carbon (SMAC) from a commercially available alkyl surfactant sulfonate anion-intercalated NiAl-LDH precursor was prepared by a thermal decomposition method followed by the acid leaching.159 The electrochemical evaluation showed that the SMAC electrode exhibits highly enhanced electrochemical performances of 958 mAh g-1 at 200 mA g-1. Furthermore, the chemical structure can be adjusted by the structural template, and the ionic conductivity can be further enhanced.160 NiCo LDH was vulcanized and then calcined with melamine followed by the selective acid treatment, achieving a large capacity of 800 mAh g-1 at 0.1 A g-1 and a good rate capability of 746 mAh g-1 at 1 A g-1 (Figure 13D).153 This good performance was attributed to the contribution of graphene and N-CNT. Although LDH has a larger interlayer spacing to facilitate the deintercalation of sodium ions, it should be noted that the interlayer anions may hinder the migration of sodium ions, lowering the electrochemical performance.

Figure 13.

The application of LDH as anode material for SIBs

(A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process of h-CoFeNi LDHs through MOF-mediated topotactic transformation. Reproduced with permission from,151 © Wiley-VCH GmbH 2020.

(B) The typical discharge/charge profiles of the CoFe-NO3-LDH at 1 A g-1.

(C) The schematic illustration of Na+ migration in CoFe-NO3-LDH. Reproduced with permission from,152 © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2019.

(D) Schematic diagram showing the preparation of (Ni0.3Co0.7)9S8/N-CNTs/rGO. Reproduced with permission from,153 © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2018.

Conclusions and outlook

This work systematically reviews the research progress of 2D materials including 2D carbon materials, TMD, MXene, BP, and LDH from perspectives of material synthesis, structure, chemistry, and application in SIBs. For each 2D material, the advantage and disadvantage regarding the application in SIBs are carefully discussed based on the intrinsic property. We illustrate the relationship between the structure of these 2D materials and their sodium storage performances (Figure 14). For different 2D materials, there are different strategies to improve the sodium storage performance. The performance of 2D carbon materials depends much on the substrate materials and the solvation, while that of TMD materials could be enhanced by nanoengineering and atomic vacancy. MXene-based materials could achieve good rate capability via constructing the porous structure, while LDH calls for the element and intercalation chemistries and template usage. BP requires typical structure design to achieve the layer exfoliation and avoid the layer stacking. From the dimensional perspective of 2D materials, expanding the interlayer spacing is a universal method to promote the mass transfer and storage of sodium ions.

Figure 14.

Summary of 2D materials for sodium storage from the perspectives of material chemistry, structure, and property

Despite the rapid advance of the application of 2D materials in SIBs, there are different challenges for different 2D materials. Each 2D material has specific advantages and disadvantages which decides the target application. As for 2D carbon materials, the interlayer distance can be expanded by the heterogeneous chemistry, which facilitates the mobility of Na+ for enhancing the sodium-ion storage performance. However, some atoms with larger radii are usually difficult to be doped into the carbon structure and may impede the ion mass transfer among the lattice matrix of carbon materials once being introduced. TMD is a widely used electrode material because of the unique layered structure and the large interlayer spacing. The poor conductivity, re-stacking, and large volume change during the sodiation/desodiation process remain as challenges, which are thought to be addressed by nanostructure construction, interlayer spacing expansion, and integration with conductive agents. Phosphorene shows super high specific capacity, whereas the preparation is environmentally costly and flammable. MXenes have been widely used in SIBs anode materials with low Na+ diffusion barrier, good metal conductivity, and intercalation ability. However, their inherent shortcomings of relatively low capacity still hamper the further development. Although LDH has a larger interlayer spacing to facilitate the deintercalation of sodium ions, it should be noted that the interlayer anions may hinder the migration of sodium ions, lowering the electrochemical performance. The conversion of LDH into layered bimetallic oxides via high-temperature treatment may promote the sodium performance by different mechanism compared to ion intercalation. In addition, it is meaningful to explore new 2D materials, although many 2D materials have been reported to date. New 2D materials may exhibit unusual and important properties. Another promising direction is to control the crystalline phase of 2D materials, which has been shown to play an important role in regulating the physicochemical properties to enhance the sodium storage performance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4101600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2003216, 22209007), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (buctrc202029, buctrc202129), the Beijing Nova Program (Z211100002121093), the fund from China Shenhua Coal to Liquid and Chemical Co., Ltd. (MZYHG-22-01), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (CJGJZD20210408092801005).

Author contributions

Y.S.: conceptualization, investigation, interpretation, compilation, visualization, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Y.Z.: conceptualization, investigation, interpretation, compilation, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. N.J.: writing – review and editing. Y.H.: writing – review and editing. K.Q.: writing – review and editing. Y.Z.: writing – review and editing. Z.L.: writing – review and editing. X.L.: writing – review and editing. Y.L.: writing – review and editing. Q.Y.: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, investigation, interpretation, compilation, and writing – review and editing. J.Q.: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, and writing – review and editing.

Declaration of interests

There are no conflicts to declare.

Contributor Information

Xuejun Lu, Email: xj.lu@buct.edu.cn.

Qi Yang, Email: qi.yang@mail.buct.edu.cn.

Jieshan Qiu, Email: qiujs@mail.buct.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Hu R., Ouyang Y., Liang T., Wang H., Liu J., Chen J., Yang C., Yang L., Zhu M. Stabilizing the nanostructure of SnO2 anodes by transition metals: A route to achieve high initial coulombic efficiency and stable capacities for lithium storage. Adv. Mater. 2017;29 doi: 10.1002/adma.201605006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang B., Han Y., Wang X., Bahlawane N., Pan H., Yan M., Jiang Y. Prussian blue analogs for rechargeable batteries. iScience. 2018;3:110–133. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q., Gu Q.F., Li Y., Fan H.N., Luo W.B., Liu H.K., Dou S.X. Surface stabilization of O3-type layered oxide cathode to protect the anode of sodium ion batteries for superior lifespan. iScience. 2019;19:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng J., Luo W.-B., Chou S.-L., Liu H.-K., Dou S.-X. Sodium-ion batteries: From academic research to practical commercialization. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye H., Wang C.-Y., Zuo T.-T., Wang P.-F., Yin Y.-X., Zheng Z.-J., Wang P., Cheng J., Cao F.-F., Guo Y.-G. Realizing a highly stable sodium battery with dendrite-free sodium metal composite anodes and O3-type cathodes. Nano Energy. 2018;48:369–376. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu D., Pang Q., Gao Y., Wei Y., Wang C., Chen G., Du F. Hierarchical flower-like VS2 nanosheets-a high rate-capacity and stable anode material for sodium-ion battery. Energy Storage Mater. 2018;11:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nayak P.K., Yang L., Brehm W., Adelhelm P. From lithium-ion to sodium-ion batteries: advantages, challenges, and surprises. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:102–120. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues M.-T.F., Babu G., Gullapalli H., Kalaga K., Sayed F.N., Kato K., Joyner J., Ajayan P.M. A materials perspective on Li-ion batteries at extreme temperatures. Nat. Energy. 2017;2:17108–17546. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K., Zhang Z., Cheng S., Han X., Fu J., Sui M., Yan P. Precipitate-stabilized surface enabling high-performance Na0.67Ni0.33-xMn0.67ZnxO2 for sodium-ion battery. eScience. 2022;2:529–536. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xin S., You Y., Wang S., Gao H.-C., Yin Y.-X., Guo Y.-G. Solid-state lithium metal batteries promoted by nanotechnology: progress and prospects. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2:1385–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao L., Qu Z. Advanced flexible electrode materials and structural designs for sodium ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2022;71:108–128. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong P., Bai P., Li A., Li B., Cheng M., Chen Y., Huang S., Jiang Q., Bu X.H., Xu Y. Bismuth nanoparticle@carbon composite anodes for ultralong cycle life and high-rate sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019;31 doi: 10.1002/adma.201904771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu R., Sun N., Zhou H., Chang X., Soomro R.A., Xu B. Hard carbon anodes derived from phenolic resin/sucrose cross-linking network for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Battery Energy. 2023;2:20220054. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J., Zhu Y., Feng Y., Han Y., Gu Z., Liu R., Yang D., Chen K., Zhang X., Sun W., et al. Research progress on key materials and technologies for secondary batteries. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2022;0:2208008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Q., Li X., Chen Z., Huang Z., Zhi C. Cathode engineering for high energy density aqueous Zn batteries. Acc. Mater. Res. 2021;3:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Q., Mo F., Liu Z., Ma L., Li X., Fang D., Chen S., Zhang S., Zhi C. Activating C-coordinated iron of iron hexacyanoferrate for Zn hybrid-ion batteries with 10 000-cycle lifespan and superior rate capability. Adv. Mater. 2019;31 doi: 10.1002/adma.201901521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Q., Qu X., Cui H., He X., Shao Y., Zhang Y., Guo X., Chen A., Chen Z., Zhang R., et al. Rechargeable aqueous Mn-metal battery enabled by inorganic-organic interfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202206471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H., Liu S., Yuan T., Wang B., Sheng P., Xu L., Zhao G., Bai H., Chen X., Chen Z., Cao Y. Influence of NaOH concentration on sodium storage performance of Na0.44MnO2. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2021;37 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun N., Qiu J., Xu B. Understanding of sodium storage mechanism in hard carbons: Ongoing development under debate. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022;12 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao C., Liu L., Qi X., Lu Y., Wu F., Zhao J., Yu Y., Hu Y.-S., Chen L. Solid-state sodium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Y.-S., Lu Y. 2019 nobel prize for the Li-ion batteries and new opportunities and challenges in Na-ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2019;4:2689–2690. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xin S., Yin Y.X., Guo Y.G., Wan L.J. A high-energy room-temperature sodium-sulfur battery. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:1261–1265. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao C., Wang Q., Yao Z., Wang J., Sánchez-Lengeling B., Ding F., Qi X., Lu Y., Bai X., Li B., et al. Rational design of layered oxide materials for sodium-ion batteries. Science. 2020;370:708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.aay9972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y., Zhou Q., Weng S., Ding F., Qi X., Lu J., Li Y., Zhang X., Rong X., Lu Y., et al. Interfacial engineering to achieve an energy density of over 200 wh kg-1 in sodium batteries. Nat. Energy. 2022;7:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai P., He Y., Zou X., Zhao X., Xiong P., Xu Y. Elucidation of the sodium-storage mechanism in hard carbons. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajagopalan R., Tang Y., Jia C., Ji X., Wang H. Understanding the sodium storage mechanisms of organic electrodes in sodium ion batteries: Issues and solutions. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020;13:1568–1592. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X., Hao F., Cao Y., Xie Y., Yuan S., Dong X., Xia Y. Dendrite-free and long-cycling sodium metal batteries enabled by sodium-ether cointercalated graphite anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;31 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pang J., Mendes R.G., Bachmatiuk A., Zhao L., Ta H.Q., Gemming T., Liu H., Liu Z., Rummeli M.H. Applications of 2D MXenes in energy conversion and storage systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:72–133. doi: 10.1039/c8cs00324f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M., Muralidharan N., Moyer K., Pint C.L. Solvent mediated hybrid 2D materials: Black phosphorus-graphene heterostructured building blocks assembled for sodium ion batteries. Nanoscale. 2018;10:10443–10449. doi: 10.1039/c8nr01400k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Z., Zhang Y., Cui Y., Gu J., Du Z., Shi Y., Shen K., Chen H., Li B., Yang S. Harnessing the unique features of 2D materials toward dendrite-free metal anodes. Energy Environ. Mater. 2021;5:45–67. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safaei J., Wang G. Progress and prospects of two-dimensional materials for membrane-based osmotic power generation. Nano Res. Energy. 2022;1 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W., Li J., Li R., Li X., Gao J., Hao S.M., Zhou W. Study on sodium storage properties of manganese-doped sodium vanadium phosphate cathode materials. Battery Energy. 2023;2 20220042. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y., Zheng Y., Rui K., Hng H.H., Hippalgaonkar K., Xu J., Sun W., Zhu J., Yan Q., Huang W. 2D black phosphorus for energy storage and thermoelectric applications. Small. 2017;13 doi: 10.1002/smll.201700661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Wang H. Designing carbon anodes for advanced potassium-ion batteries: Materials, modifications, and mechanisms. Advanced Powder Mater. 2022;1 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou H., Qiu X., Wei W., Zhang Y., Ji X. Carbon anode materials for advanced sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017;7 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen Y., He K., Zhu Y., Han F., Xu Y., Matsuda I., Ishii Y., Cumings J., Wang C. Expanded graphite as superior anode for sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4033. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Lu Y., Adelhelm P., Titirici M.M., Hu Y.S. Intercalation chemistry of graphite: Alkali metal ions and beyond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:4655–4687. doi: 10.1039/c9cs00162j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoon G., Kim H., Park I., Kang K. Conditions for reversible Na intercalation in graphite: Theoretical studies on the interplay among guest ions, solvent, and graphite host. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017;7:1601519. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z., Selbach S.M., Grande T. Van der waals density functional study of the energetics of alkali metal intercalation in graphite. RSC Adv. 2014;4:3973–3983. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nobuhara K., Nakayama H., Nose M., Nakanishi S., Iba H. First-principles study of alkali metal-graphite intercalation compounds. J. Power Sources. 2013;243:585–587. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y., Xiao N., Wang Z., Li H., Yu M., Tang Y., Hao M., Liu C., Zhou Y., Qiu J. Rational design of high-performance sodium-ion battery anode by molecular engineering of coal tar pitch. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;342:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y., Xiao N., Wang Z., Tang Y., Li H., Yu M., Liu C., Zhou Y., Qiu J. Ultrastable and high-capacity carbon nanofiber anodes derived from pitch/polyacrylonitrile for flexible sodium-ion batteries. Carbon. 2018;135:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y.-S., Zhang B.-M., Hu Y.-X., Li J., Lu C., Liu M.-J., Wang K., Kong L.-B., Zhao C.-Z., Niu W.-J., et al. Diamine molecules double lock-link structured graphene oxide sheets for high-performance sodium ions storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2021;34:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim Y.J., Pyo S., Kim S., Ryu W.-H. Group VI metallic pillars for assembly of expanded graphite anodes for high-capacity Na-ion batteries. Carbon. 2021;175:585–593. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pyo S., Eom W., Kim Y.J., Lee S.H., Han T.H., Ryu W.H. Super-expansion of assembled reduced graphene oxide interlayers by segregation of Al nanoparticle pillars for high-capacity Na-ion battery anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2020;12:23781–23788. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c00659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Datta D., Li J., Shenoy V.B. Defective graphene as a high-capacity anode material for Na- and Ca-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2014;6:1788–1795. doi: 10.1021/am404788e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao R., Sun N., Xu B. Recent advances in heterostructured carbon materials as anodes for sodium-ion batteries. Small Struct. 2021;2:2100132. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong L., Li Y., Feng W. Fluorine-doped hard carbon as the advanced performance anode material of sodium-ion batteries. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2022;28:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao J., Xiao N., Li K., Zhang L., Ma X., Li Y., Leng C., Qiu J. Sodium metal anodes with self-correction function based on fluorine-superdoped CNTs/cellulose nanofibrils composite paper. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022;32:2111133. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia X., Du C.F., Zhong S., Jiang Y., Yu H., Sun W., Pan H., Rui X., Yu Y. Homogeneous Na deposition enabling high-energy Na-metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021;32:2110280. [Google Scholar]