Abstract

Noscapine, a phthalide isoquinoline alkaloid isolated from the opium poppy, alongside cotarnine, a tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) scaffold produced by the oxidative degradation of noscapine, has exhibited antitumor activities against several types of cancer. Although derivatization with amino acids is regarded as a promising strategy to improve chemotherapeutics’ anticancer properties, amino acid conjugates of noscapine and cotarnine have been the least investigated. In the present study, 20 amino acid conjugated derivatives of noscapine and cotarnine at the 6-position were synthesized and evaluated for anticancer activity in both in vitro and in vivo conditions. Analysis of the antiproliferative activity against 4T1 mammary carcinoma tumor cells showed that compounds 6h (noscapine–phenylalanine), 6i (noscapine–tryptophan), and 10i (cotarnine–tryptophan) with IC50 values of 11.2, 16.3, and 54.5 μM, respectively, were found to be far more potent than noscapine (IC50 = 215.5 μM) and cotarnine (IC50 = 575.3 μM) and were consequently opted for further characterization. Annexin V and propidium iodide staining followed by flow cytometry demonstrated improved apoptotic activity of compounds 6h, 6i, and 10i compared to those of noscapine and cotarnine. In a murine model of 4T1 mammary carcinoma, noscapine–tryptophan inhibited tumor growth more effectively than noscapine and the other amino acid conjugates without adverse effects. Moreover, molecular docking studies conducted on tubulin as the intracellular target of noscapine suggested a good correlation with experimental observations. Based on these results, noscapine–tryptophan could be a promising candidate for further preclinical investigations.

1. Introduction

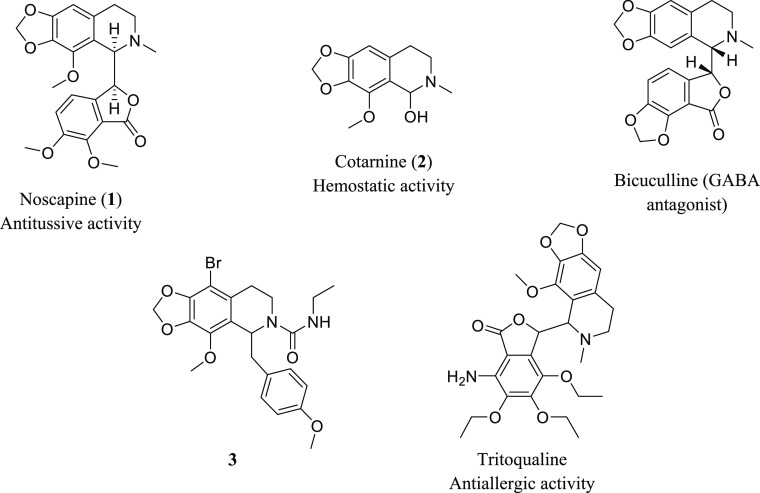

Cancer is one of the biggest threats to human health. It is a deadly disease with an increasing annual mortality rate. Current therapies, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy, are associated with high toxicity that not only confines tolerability but also imposes limitations to clinical application. Therefore, there exists an obvious need for more efficient, selective, and novel methods to treat a variety of human malignancies.1 Different compounds derived from several natural products can exhibit both chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic effects on cancer. Isoquinoline alkaloids are a large group of natural products exhibiting a broad spectrum of biological properties, especially anticancer ones.2,3 Tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) scaffolds are also found in several pharmaceutically active compounds.4,5 In recent years, noscapine (1), a THIQ, has attracted a great deal of attention as a potent anticancer agent.6 Noscapine is a phthalide isoquinoline alkaloid isolated from Papaver somniferum(7) which in mid-1950s was utilized as a cough suppressant.8 In the late 1990s, noscapine was proved to have cytotoxic activity. It arrests tumor cells during mitosis and induces apoptosis by disrupting microtubule dynamics through acting on tubulin and displays potent antitumor activity against solid lymphocytic tumor cells in mice.9 Tubulin-targeting compounds are highly crucial agents in cancer chemotherapy. These compounds can be classified into two groups. The latter one consists of drugs that inhibit tubulin polymerization such as vinca alkaloids, colchicine, and combretastatin. Yet, the former one includes compounds that promote tubulin polymerization, namely, taxanes including paclitaxel.6 Noscapine does not overpolymerize or depolymerize microtubules over a wide range of concentrations. In fact, it causes subtle changes in the dynamics of microtubules.10 Toxicity, multidrug resistance, poor aqueous solubility, along with low drug availability are the major issues connected with the current chemotherapy drugs.6,11 Noscapine could be a candidate to overcome the above disadvantages due to its negligible side effects, very little toxicity to normal cells, and the possibility of its oral administration.5

Cotarnine (2), a natural THIQ alkaloid, is isolated from Papaver pseudo-orientale.12 It is one of noscapine’s oxidative degradation products. Cotarnine hydrochloride is employed as a hemostatic agent and is the key component in the synthesis of tritoqualine, which is an antiallergic drug.13 There exist several pharmaceutically active compounds with a cotarnine core that are capable of exhibiting considerable biological activities (Figure 1). So far, countless noscapine derivatives containing a cotarnine core with notable biological activities have been synthesized. Some of these analogues have promising cytotoxic activities against diverse cancer cell lines.14 Devine and co-workers synthesized a series of THIQs by removing the isobenzofuranone part of noscapine, from which two of them prevent mitosis far better than noscapine. Compound 3 showed a 208% elevation in arresting G2/M in MCF-7 cells in a cell-cycle-arrest assay compared to noscapine.15

Figure 1.

Bioactive compounds containing a cotarnine core.

Amino acids (AAs), the most prevalent group of naturally occurring compounds, play an essential role in drug discovery. AAs are essential components in the development of modern medicinal chemistry because of their desirable properties, including availability, high solubility in aqueous media, and the possibility of structural diversity on two available functional groups (amine and carboxyl) by facile reactions like amidation, acylation, alkylation, and esterification.16,17 Previous investigations demonstrated that coupling amino acids with some natural compounds improved their solubility and biological activity.18−20

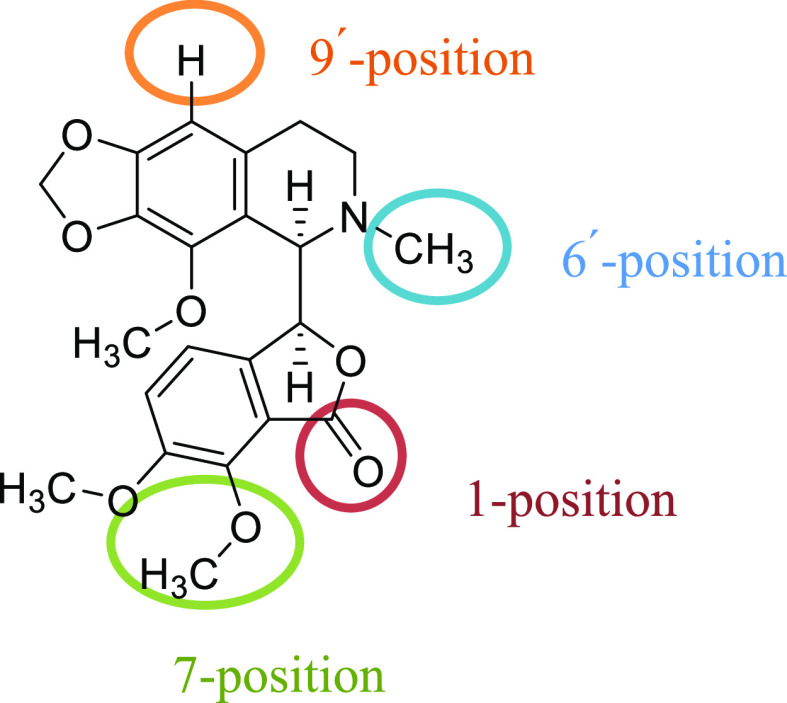

Modifications to various segments of noscapine’s structure have resulted in the synthesis of numerous analogues over the past two decades in order to improve its anticancer activity (Figure 2). These new analogues have been introduced as potential anticancer agents. This led to the identification of a series of semisynthetic noscapine derivatives with notable in vitro and in vivo activities.21

Figure 2.

Modification sites of noscapine.

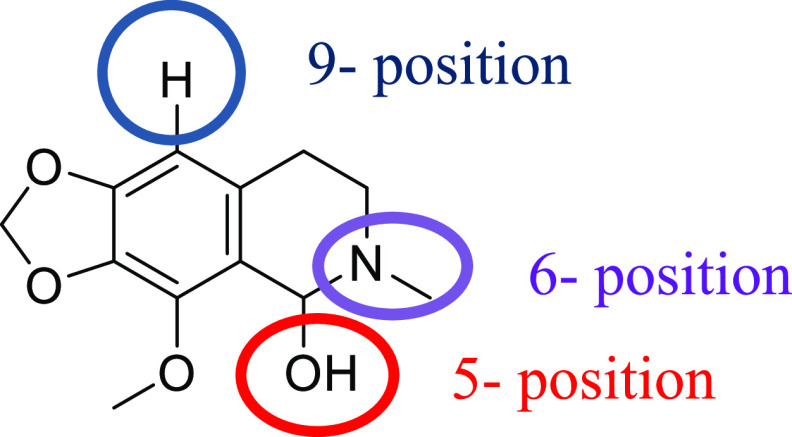

Awasthi et al. synthesized noscapine–amino acid conjugates by introducing amino acids at the 9-position of noscapine. They developed the noscapine–tryptophan conjugate as a possible antitumor compound to be assessed against the A549 lung cancer cell line.22 In several previous reports, several noscapine analogues were developed by modification on its 6-position. These derivatives were potential tubulin inhibitors and have shown better cytotoxic properties compared to noscapine.23−26 Cotarnine derivatives have usually been associated with modifications at the 5- and 9-positions (Figure 3).14 Zimmermann and co-workers introduced a THIQ scaffold by replacing the phthalide moiety of noscapine with different alkynes. The antimitotic effects of this new structure on HeLa cells were shown to be stronger than noscapine.27 So far, no new compound has been reported by modification on the 6-position of cotarnine.

Figure 3.

Cotarnine and its modification sites.

In this paper, we have synthesized a series of novel THIQ derivatives of noscapine and cotarnine by conjugation of amino acids at the C-6 position. Afterward, the anticancer properties of these new analogues were evaluated in vitro and in vivo, and the outcomes were compared.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

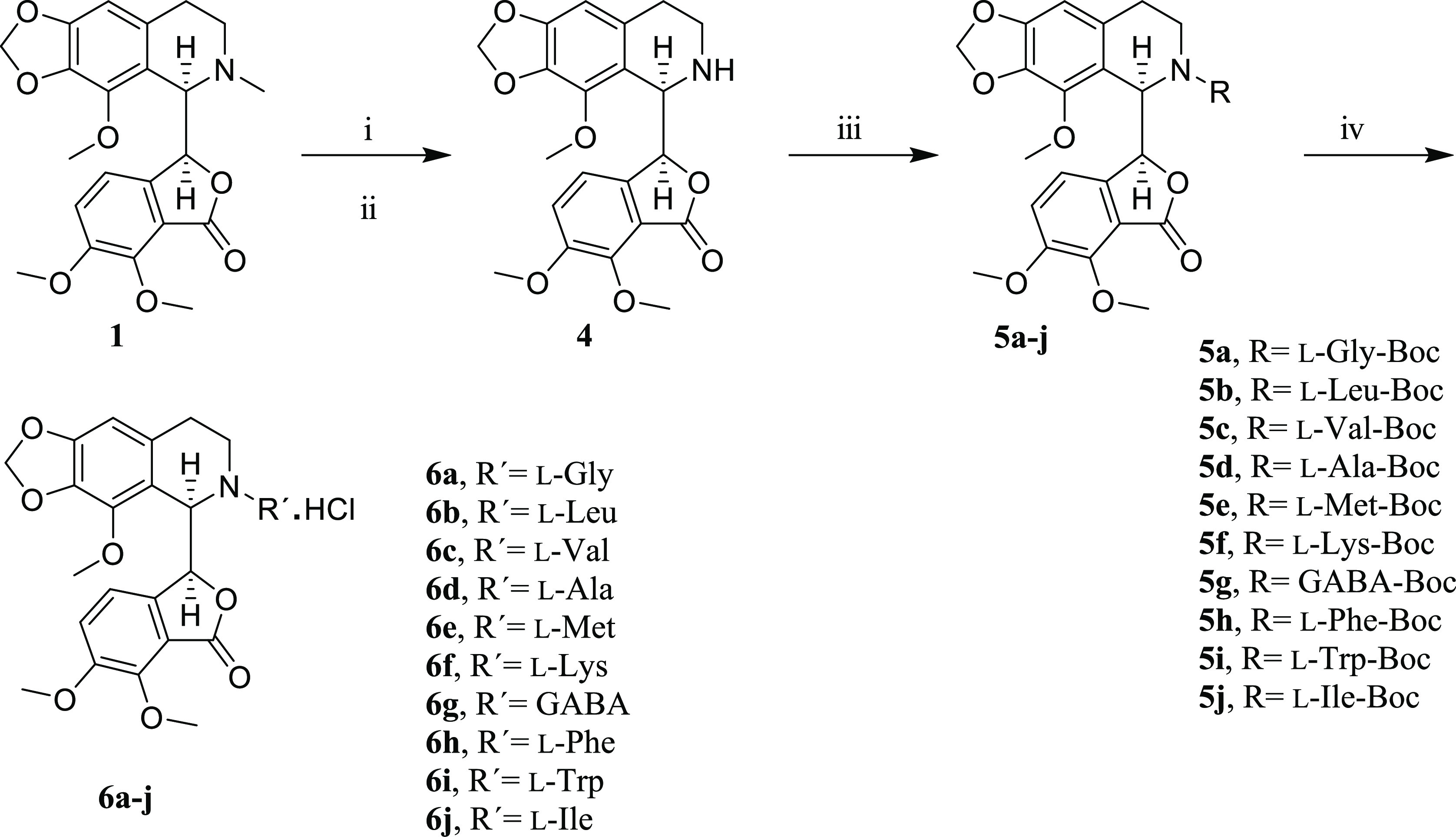

Chemical modifications to the C-6 position of the noscapine molecule have been shown to enhance its anticancer activity. Our strategy for modifying the 6-position of noscapine is depicted in Scheme 1. First, N-nor-noscapine (4) was synthesized by a demethylation reaction in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and ferrous sulfate. Conjugation of the N-Boc-protected amino acids was done by 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate (TBTU) as the coupling agent to yield 5a–j. Finally, deprotection in the presence of HCl/ isopropyl alcohol ended up with the formation of the desired products (6a–j).

Scheme 1. Route for the Synthesis of Noscapine Derivatives.

Reagents and conditions: (i) H2O2, ACN, rt, 2h; (ii) FeSO4·7H2O, MeOH, −8 °C, 8h; (iii) N-Boc-protected amino acids, TBTU, DCM, rt; (iv) HCl/isopropyl alcohol, rt.

For the synthesis of cotarnine amino acid analogues, 2 was synthesized from noscapine via an oxidative degradation process in the presence of HNO3. Dehydration in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and subsequent reduction with NaBH4 produced hydrocotarnine (7). N-Demethylation of 7 was done by a procedure similar to that of noscapine by H2O2 and FeSO4·7H2O to produce 8. Coupling of N-Boc-protected amino acids by TBTU (2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate) followed by deprotection of the tert-butyloxycarbonyl group yielded the target molecules (10a–j) (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Cotarnine–Amino Acid Derivatives.

Reagents and conditions: (i) HNO3 18%, 1.5 h, 50 °C; (ii) TFA, NaBH4, CHCl3; (iii) H2O2, ACN, rt, 2 h; (iv) FeSO4·7H2O, MeOH, −8 °C, 8 h; (v) N-Boc-protected amino acids, TBTU, DCM, rt; (vi) HCl/isopropyl alcohol, rt.

2.2. Biological Evaluation

2.2.1. Cell Proliferation Assay

Noscapine has previously been shown to inhibit tumor cell growth.6 Therefore, we tested the cytotoxicity of all of the synthesized compounds using the MTT (MTT = 3-[4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. The reference compound noscapine showed an IC50 value of 215.5 μM. Compared to noscapine, the analogues exhibited weak to strong antiproliferative activities (Table 1). The calculated IC50 values ranged from 11.2 μM for 6h to 902.1 μM for 10a. The most active compounds were 6h, 6i, and 10i with IC50 values of 11.2, 16.3, and 54.5 μM, respectively. These results indicated that noscapine–amino acid hybrids could inhibit the proliferation of 4T1 breast cancer tumor cells. Among the synthesized noscapinoids, the most active analogues were noscapine–phenylalanine (6h), noscapine–tryptophan (6i), and cotarnine–tryptophan (10i). The functional properties of compounds 6h, 6i, and 10i were selected for further evaluation.

Table 1. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of the Synthesized Noscapine and Cotarnine Analogues.

| IC50 (μM) | compound | IC50a (μM) | compound |

|---|---|---|---|

| 902.1 | 10a | 181.6 | 6a |

| 144.6 | 10b | 200.5 | 6b |

| 489.7 | 10c | 145.5 | 6c |

| 708.4 | 10d | 168.2 | 6d |

| 541.2 | 10e | 268.4 | 6e |

| 659.2 | 10f | 360 | 6f |

| 657.5 | 10g | 101.4 | 6g |

| 268.1 | 10h | 11.2 | 6h |

| 54.5 | 10i | 16.3 | 6i |

| 96.3 | 10j | 100.8 | 6j |

| 575.3 | cotarnine | 215.5 | noscapine |

IC50: half-maximal inhibitory concentration.

2.2.2. Induction of Apoptosis

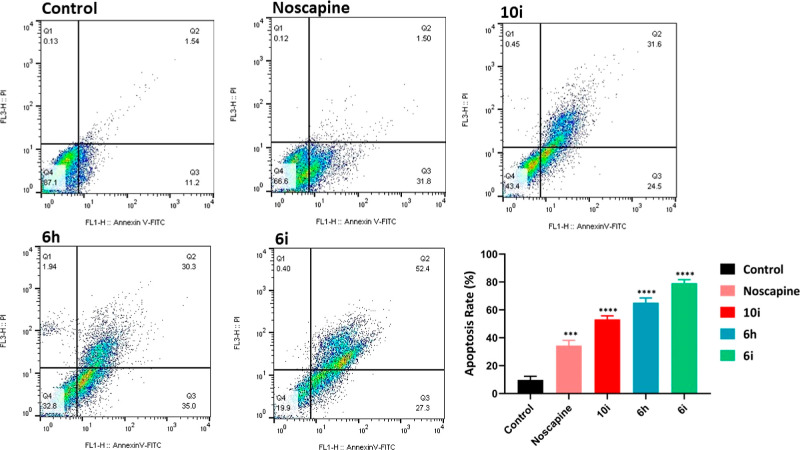

Previous investigations disclosed that noscapine and its analogues induced apoptosis in many tumor cell types.22,28−30 To determine whether the induction of apoptosis is responsible for the antiproliferative property of noscapine analogues, we assessed the induction of apoptosis in 4T1 mammary carcinoma tumor cells using annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining. As indicated in Figure 4, the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was 33.3% in noscapine-treated cells. In comparison, the percentages of apoptotic cells were 56.1, 65.2, and 87.6% in 10i, 6h, and 6i, respectively. These results, in accordance with previous investigations, demonstrate that the induction of apoptosis is a mechanism of cell death and the inhibition of cancer cell multiplication.

Figure 4.

Detection of apoptosis in 4T1 breast tumor cells for noscapine, 6h, 6i, and 10i using annexin V and PI staining followed by flow cytometry. Error bars represent ± SEM n = 3; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; unpaired Student’s t-test.

2.2.3. Antitumor Effect of Compounds against the 4T1 Mammary Carcinoma Tumor Model

The antitumor property of the selected compounds was assessed in the murine 4T1 mammary carcinoma tumor model, which is a metastatic triple-negative breast cancer model. Solid tumors were subcutaneously transplanted in BALB/C mice, and when tumors reached a size of ∼100 mm3, the compounds were injected intraperitoneally once every three days for 17 days. First, tumor-bearing mice were treated with a dosage of 40 mg/kg of compounds 6h, 6i, 10i, noscapine, and PBS (control). As indicated in Figure 5A, all compounds potently inhibited the growth of mammary carcinoma, and no significant differences were observed between treatments. Next, we compared the antitumor effects of the compounds at a lower dose (8 mg/kg). Interestingly, the antitumor efficacy of compounds at 8 mg/kg was different (Figure 5B). Following completion of the treatment period, which was 30 days after implantation, different amounts of tumor growth regression were observed in the treated groups. The mean tumor volume in animals treated with PBS (control), 10i, noscapine, 6h, and 6i was 3165.3, 2069.8, 1181.7, 1034, and 576 mm3, respectively, indicating that 6i was the most effective and 10i was the least effective compound. Although noscapine and its analogues have been investigated for their efficacy against various cancer models,30−33 there is no report on the effect of noscapinoids on the metastatic 4T1 breast cancer model.

Figure 5.

Inhibitory effect of selected analogues and noscapine on tumor growth in vivo. Female BALB/c mice were implanted with 4T1 murine MCT, and when the tumor volume reached around 100 mm3, the experimental group mice were given intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of different doses of 6h, 6i, 10i, and noscapine once every three days for 17 days. (A) Dosage of 40 mg/kg. (B) Dosage of 8 mg/kg. Meanwhile, the control group of mice received the same amount of PBS. Each group consisted of 6 mice. Error bars denote ± SEM n = 6; ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant; two-way ANOVA.

2.3. Molecular Docking

To investigate protein–ligand interactions and predict the binding affinity of new analogues with tubulin, which is a target protein for noscapine, molecular docking studies were conducted using AutoDock suite 4.2.6 software.34,35Table 2 lists the docking scores of the compounds with IC50 values superior to that of noscapine. The biological assessments were in good agreement with the results of molecular docking. The ligand–protein complexes were analyzed by examining the binding interactions and minimum binding energy values. Notably, compounds 6h, 6i, and 10i, which demonstrated the best IC50 values (11.2, 16.3, and 54.5 μM, respectively), exhibited significant affinity to tubulin with binding energies of −8.4, −8.9, and −7.9 kcal/mol, respectively, compared to −5.3 kcal/mol for noscapine.

Table 2. Binding Energy (kcal/ mol) of Synthesized Compounds and Noscapine as the Reference Compound.

| binding energy (kcal/mol) | compound | binding energy (kcal/mol) | compound |

|---|---|---|---|

| –8.9 | 6i | –6.6 | 6a |

| –6.6 | 6j | –8.1 | 6b |

| –6.1 | 10b | –6.6 | 6c |

| –7.9 | 10i | –7.4 | 6d |

| –6.0 | 10j | –6.1 | 6g |

| –5.3 | noscapine | –8.4 | 6h |

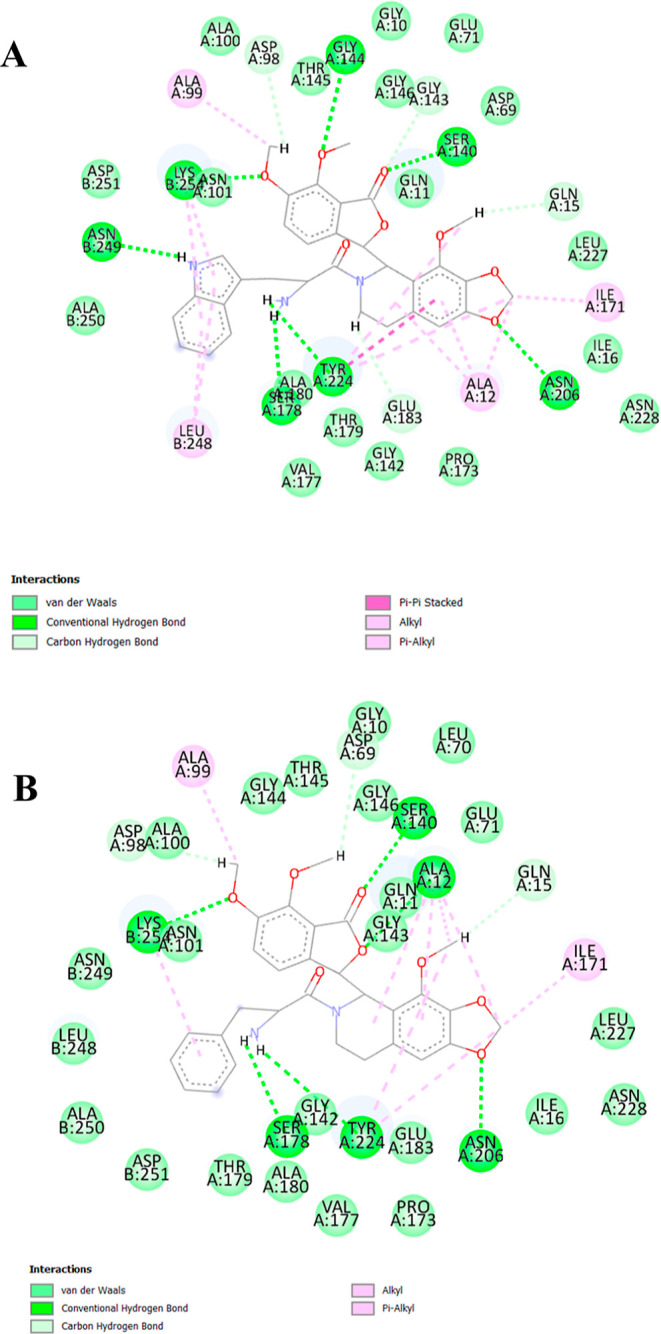

The ligand–tubulin complexes of these compounds were stabilized by hydrogen bonding, π–π, alkyl, π–alkyl, and van der Waals interactions. Compound 6i, which exhibited the highest affinity, interacts with the active site of the protein through hydrogen bonding with amino acid residues ASN B: 249, SER A: 178, TYR A: 224, ASN A: 206, LYS B: 254, SER A: 140, and GLY A: 144. Additionally, it engages in π–π stacking with TYR A: 224 and alkyl and π–alkyl interactions with ALA A: 99, LEU B: 248, ALA A: 12, LYS B: 254, TYR A: 224, and ILE A: 171 amino acid residues. On the other hand, the interaction of 6h with tubulin involves hydrogen bonding with amino acid residues LYS B: 254, SER A: 140, SER A: 178, ALA A: 12, TYR A: 224, and ASN A: 206, as well as alkyl and π–alkyl interaction with ALA A: 99, ILE A: 171, ALA A: 12, LYS B: 254, and TYR A: 224. These interactions are illustrated in Figures 6 and 7, which were visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer v21.1.0.20298.

Figure 6.

Binding mode of ligands 6i and 6h with tubulin (PDB ID: 1SA0). (A) Docked complex of 6i with1SA0 and (B) docked complex of 6h with 1SA0.

Figure 7.

2D receptor–ligand interaction of compounds (A) 6i and (B) 6h with the binding site of tubulin (PDB ID: 1SA0).

3. Conclusions

In brief, we have designed and synthesized 20 novel noscapine–amino acid and cotarnine–amino acid conjugates and evaluated their potential anticancer activities in vitro and in vivo. Among the products, the noscapine–tryptophan conjugate displayed the highest anticancer capabilities against the 4T1 model of breast cancer. Importantly, noscapine–amino acid conjugates were more potent than the cotarnine–amino acid counterparts, indicating that the phthalide moiety plays a role in the anticancer property of these amino acid conjugates. Based on the finding that the noscapine–tryptophan conjugate leads to potent cytotoxicity, apoptosis induction, and tumor growth regression, we anticipate that the noscapine–tryptophan conjugate is a potential candidate for breast cancer treatment.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Chemistry

Noscapine was obtained from Faran Shimi Pharmaceutical Co. Other reagents were commercially available and used without further purification. N-Boc-protected amino acids were prepared following a previously described method with some modifications.36 Nor-noscapine (4) was synthesized according to our previous report.37 Cotarnine (2) and hydrocotarnine (7) were also synthesized using the procedures detailed in previously published literature.38,39 The advancement of the reactions was observed through thin-layer chromatography on Merck Co. aluminum sheets coated with silica gel F254. The silica gel 60 used for column chromatography had a particle size ranging from 0.063 to 0.200 μm and a mesh size of 70–230. The products were purified using preparative thin-layer chromatography plates covered with silica gel 60 PF254 containing gypsum. A Barnstead/Electrothermal 9200 instrument was utilized to determine the melting points. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6, CDCl3, and D2O on Bruker 300 and 400 MHz instruments, and coupling constants (J) are in Hertz (Hz), while chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in ppm. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded by using a Waters Micromass LCT Premier mass spectrometer.

4.2. In Vitro Studies

4.2.1. Cell Culture

The breast cancer cell line (C604), also known as the 4T1 mammary carcinoma cell line, was acquired from the Pasteur Institute’s National Cell Bank in Iran. The cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute media (RPMI-1640) containing 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin and maintained in a wet incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

4.2.2. Cytotoxic Assay

The MTT assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of 6a–j, 10a–j, 1, and 2 on 4T1 cells after a 24 h exposure period. Initially, about 1 × 104 4T1 cells were seeded in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin in 96-well plates and left to incubate overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2 prior to treatment. Following this, various doses of 6a–j, 10a–j, 1, and, 2 (0–413 g/mL) were utilized to treat cells for 24 h and compared them with untreated cells. Thereafter, 150 μL of fresh culture medium and 50 μL of MTT solution (2 mg/mL PBS) were introduced to each well and allowed to incubate for 4h at 37 °C. After incubation, 200 μL of DMSO was added to the culture medium to dissolve the purple formazan. Subsequently, Eliza reader analyzed the observation of each plate at 570 nm wavelength (Sunraise, TCAN Co., Austria).

4.2.3. Detection of Apoptosis through the Use of Flow Cytometry

Cells from the 4T1 cell line were seeded at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells per well in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% PBS, in order to assess and quantify the extent of apoptosis in cells treated with 6h, 6i, 10i, 1, and 2. Following a 24 h incubation period, the culture medium was replaced with 2 mL of fresh medium containing the IC50 dose of each treatment. The cells were then incubated for an additional 48 h. Subsequently, trypsin was used to detach the cells, and the resulting centrifuged cell sediment was resuspended in 1× binding buffer. Next, the cells were subjected to staining using the annexin V-fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FITC)/PI apoptosis detection kit (Exbio, Czech Republic) following the manufacturer’s protocol and allowed to incubate for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, the binding of annexin V-FITC/PI, which provided diagnostic information on apoptotic and necrotic cells, was evaluated utilizing flow cytometry (MACS Quant 10; Miltenyi Biotech GmbH). The FlowJo software tool (Treestar, Inc., San Carlos, CA) was used to analyze the data obtained from the assessment.

4.3. In Vivo Study

4.3.1. Antitumor Activity of Compounds in Tumor-Bearing Mice

A total of thirty female BALB/c mice (aged 6–8 weeks) were procured from the Iran Pasteur Institute’s Laboratory Animal Center and were housed in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IACUC). The mice were maintained in adherence to animal welfare regulations and were provided with sterilized food and water with unrestricted access. Additionally, they were subjected to 12 h light–dark cycles. To generate 4T1 tumor models, mice were hypodermically injected with tumor cells (4T1; 1 × 106 cells/500 μL or 1 × 105 cells/50 μL) into the right flanks, with 3–5 mice being used for each injection. The 4T1 tumors were removed from breast cancer mice under ketamine (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) anesthesia and then split into small pieces (less than 0.3 cm3) before being implanted into the right flanks of BALB/c mice. Once the tumors had grown to 100 mm3, mice with cancerous tumors were randomly divided into 5 groups of 6 each. The effectiveness of 6h, 6i, 10i, and noscapine in fighting cancer was evaluated by administering i.p. injections of a 40 mg/kg dose (in 100 μL), with the control group receiving only sterile PBS. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula: volume = length × width2 × 0.52, and the width and length of the tumors were measured every four days using a digital Vernier caliper (Mitutoyo, Japan). In the second phase, mice were given i.p. injections of 8 mg/kg (in 100 μL) of 6h, 6i, 10i, and noscapine to determine their antitumor effectiveness.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Production of graphs, data analysis, and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, version 8). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for statistical significance was used for multiple comparisons. In vivo efficacy experiments used two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Shahid Beheshti University Research Council for partial support of this work. We would like to acknowledge the Animal Lab of Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Tehran, to provide the facility for in vivo studies for this research.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c05488.

Experimental procedures for all the synthesized compounds, molecular docking studies, and 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS spectra (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2R3, Canada

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kashyap D.; Tuli H. S.; Yerer M. B.; Sharma A.; Sak K.; Srivastava S.; Pandey A.; Garg V. K.; Sethi G.; Bishayee A. Natural product-based nanoformulations for cancer therapy: Opportunities and challenges. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 69, 5–23. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingaew R.; Mandi P.; Nantasenamat C.; Prachayasittikul S.; Ruchirawat S.; Prachayasittikul V. Design, synthesis and molecular docking studies of novel N-benzenesulfonyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-based triazoles with potential anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 81, 192–203. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. Y.; Suresh Kumar G. Natural isoquinoline alkaloids: binding aspects to functional proteins, serum albumins, hemoglobin, and lysozyme. Biophys. Rev. 2015, 7, 407–420. 10.1007/s12551-015-0183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanivas T.; Sushma B.; Nayak V. L.; Chandra Shekar K.; Srivastava A. K. Design, synthesis and biological evaluations of chirally pure 1,2,3,4-tertrahydroisoquinoline analogs as anti-cancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 92, 608–618. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I. P.; Shah P. Tetrahydroisoquinolines in therapeutics: a patent review (2010–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 17–36. 10.1080/13543776.2017.1236084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar R.; Sahni A.; Chandra I.; Tomar V.; Chandra R. Review of Noscapine and its Analogues as Potential Anti-Cancer Drugs. Mini-Reviews Org. Chem. 2018, 15, 345–363. 10.2174/1570193X15666180221153911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeBono A. J.; Mistry S. J.; Xie J.; Muthiah D.; Phillips J.; Ventura S.; Callaghan R.; Pouton C. W.; Capuano B.; Scammells P. J. The synthesis and biological evaluation of multifunctionalised derivatives of noscapine as cytotoxic agents. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 399–410. 10.1002/cmdc.201300395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennani Y. L.; Gu W.; Canales A.; Díaz F. J.; Eustace B. K.; Hoover R. R.; Jiménez-Barbero J.; Nezami A.; Wang T. Tubulin binding, protein-bound conformation in solution, and antimitotic cellular profiling of noscapine and its derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1920–1925. 10.1021/jm200848t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K.; Ke Y.; Keshava N.; Shanks J.; Kapp J. A.; Tekmal R. R.; Petros J.; Joshi H. C. Opium alkaloid noscapine is an antitumor agent that arrests metaphase and induces apoptosis in dividing cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 1601–1606. 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checchi P. M.; Nettles J. H.; Zhou J.; Snyder J. P.; Joshi H. C. Microtubule-interacting drugs for cancer treatment. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003, 24, 361–365. 10.1016/s0165-6147(03)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capilla A. S.; Soucek R.; Grau L.; Romero M.; Rubio-Martínez J.; Caignard D. H.; Pujol M. D. Substituted tetrahydroisoquinolines: synthesis, characterization, antitumor activity and other biological properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 145, 51–63. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.12.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley K. W.; Berberines O. M.; Alkaloids R.; Alkaloids A.; Aporphines D.; Dimers A.-B.; Acids A.; Alkaloids M.; Alkaloids H.; Alkaloids O. β-Phenylethylamines and the isoquinoline alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1989, 6, 405–432. 10.1039/NP9890600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury S. K.; Rout P.; Parida B. B.; Florent J. C.; Johannes L.; Phaomei G.; Bertounesque E.; Rout L. Metal-Free Activation of C (sp3)-H Bond, and a Practical and Rapid Synthesis of Privileged 1-Substituted 1, 2, 3, 4-Tetrahydroisoquinolines. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2017, 2017, 5275–5292. 10.1002/ejoc.201700471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S. K.; Behera P. K.; Panda S.; Choudhury P.; Rout L. Developments in chemistry and biological application of cotarnine & its analogs. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131663. 10.1016/j.tet.2020.131663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devine S. M.; Yong C.; Amenuvegbe D.; Aurelio L.; Muthiah D.; Pouton C.; Callaghan R.; Capuano B.; Scammells P. J. Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Noscapine-Inspired 5-Substituted Tetrahydroisoquinolines as Cytotoxic Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 8444–8456. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaskovich M. A. T. Unusual Amino Acids in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10807–10836. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.; Konno H.; Sato T.; Soloshonok V. A.; Izawa K. Tailor-made amino acids in the design of small-molecule blockbuster drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 220, 113448. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csuk R.; Schwarz S.; Siewert B.; Kluge R.; Ströhl D. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of methyl glycyrrhetinate esterified with amino acids. Z. Naturforsch., B: Chem. Sci. 2012, 67, 731–746. 10.5560/znb.2012-0107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L.; Wang M.; Gou S.; Liu X.; Zhang H.; Cao F. Combination of amino acid/dipeptide with nitric oxide donating oleanolic acid derivatives as PepT1 targeting antitumor prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1116–1120. 10.1021/jm401634d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W. B.; Zhang H.; Yan W. Q.; Liu Y. M.; Zhou F.; Cai D. S.; Zhang W. X.; Huang X. M.; Jia X. H.; Chen H. S.; Qi J. C.; Wang P. L.; Xu B.; Lei H. M. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of ligustrazine - betulin amino-acid/dipeptide derivatives as anti-tumor agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 185, 111839. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBono A.; Capuano B.; Scammells P. J. Progress Toward the Development of Noscapine and Derivatives as Anticancer Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5699–5727. 10.1021/jm501180v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A.; Kumar N.; Mishra A.; Ravi R.; Dalal A.; Shankar S.; Chandra R. Noscapine-Amino Acid Conjugates Suppress the Progression of Cancer Cells. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 1292–1304. 10.1021/acsptsci.2c00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemati F.; Bischoff-Kont I.; Salehi P.; Nejad-Ebrahimi S.; Mohebbi M.; Bararjanian M.; Hadian N.; Hassanpour Z.; Jung Y.; Schaerlaekens S.; Lucena-Agell D.; Oliva M. A.; Fürst R.; Nasiri H. R. Identification of novel anti-cancer agents by the synthesis and cellular screening of a noscapine-based library. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 115, 105135. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debono A. J.; Xie J. H.; Ventura S.; Pouton C. W.; Capuano B.; Scammells P. J. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of N-Substituted Noscapine Analogues. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 2122–2133. 10.1002/cmdc.201200365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemati F.; Salehi P.; Bararjanian M.; Hadian N.; Mohebbi M.; Lauro G.; Ruggiero D.; Terracciano S.; Bifulco G.; Bruno I. Discovery of noscapine derivatives as potential β-tubulin inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127489. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheriyamundath S.; Mahaddalkar T.; Reddy Nagireddy P. K.; Sridhar B.; Kantevari S.; Lopus M. Insights into the structure and tubulin-targeted anticancer potential of N-(3-bromobenzyl) noscapine. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 71, 48–53. 10.1016/j.pharep.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann T. J.; Roy S.; Martinez N. E.; Ziegler S.; Hedberg C.; Waldmann H. Biology-Oriented Synthesis of a Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compound Collection Targeting Microtubule Polymerization. ChemBioChem 2013, 14, 295–300. 10.1002/cbic.201200711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragyandipta P.; Naik M. R.; Bastia B.; Naik P. K. Development of 9-(N-arylmethylamino) congeners of noscapine: the microtubule targeting drugs for the management of breast cancer. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 38. 10.1007/s13205-022-03445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagireddy P. K. R.; Kumar D.; Kommalapati V. K.; Pedapati R. K.; Kojja V.; Tangutur A. D.; Kantevari S. 9-Ethynyl noscapine induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis by disrupting tubulin polymerization in cervical cancer. Drug Dev. Res. 2021, 83, 605–614. 10.1002/ddr.21888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. R.; Liu M.; Peng X. L.; Lei X. F.; Zhang J. X.; Dong W. G. Noscapine induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human colon cancer cells in vivo and in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 421, 627–633. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneja R.; Zhou J.; Vangapandu S. N.; Zhou B.; Chandra R.; Joshi H. C. Drug-resistant T-lymphoid tumors undergo apoptosis selectively in response to an antimicrotubule agent, EM011. Blood 2006, 107, 2486. 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Luo X. J.; Liao F.; Lei X. F.; Dong W. G. Noscapine induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 605–612. 10.1007/s00280-010-1356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G.; Niu Z.; Dong J.; Zhao Y.; Zhang Y.; Li X. Noscapine inhibits human hepatocellular carcinoma growth through inducing apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Neoplasma 2016, 63, 726–733. 10.4149/neo_2016_509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G. M.; Goodsell D. S.; Halliday R. S.; Huey R.; Hart W. E.; Belew R. K.; Olson A. J. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravelli R. B. G.; Gigant B.; Curmi P. A.; Jourdain I.; Lachkar S.; Sobel A.; Knossow M. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature 2004, 428, 198–202. 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Jaipuri F. A.; Waldo J. P.; Potturi H.; Marcinowicz A.; Adams J.; Van Allen C.; Zhuang H.; Vahanian N.; Link C.; Brincks E. L.; Mautino M. R. Discovery of indoximod prodrugs and characterization of clinical candidate NLG802. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 198, 112373. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babanezhad Harikandei K.; Salehi P.; Ebrahimi S. N.; Bararjanian M.; Kaiser M.; Khavasi H. R.; Al-Harrasi A. N-substituted noscapine derivatives as new antiprotozoal agents: Synthesis, antiparasitic activity and molecular docking study. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 91, 103116. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout L. Synthesis of Acyl Derivatives of Cotarnine. Org. Synth. 2018, 95, 455–471. 10.15227/orgsyn.095.0455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D.; Mao Y.; Song S.; Cheng M. A New Total Synthesis of (±)-α-Noscapine. Heterocycles 2013, 87, 2633–2640. 10.3987/COM-13-12843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.