Abstract

Coccidioidomycosis, also known as San Joaquin Valley fever, is an illness caused by the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides. Coccidioidomycosis is endemic to desert regions of the Western Hemisphere, including California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico. We report a case of disseminated coccidioidomycosis in a 42-year-old male. Months after an upper respiratory infection of unidentified origin, the patient began experiencing back pain. The persistence of the back pain prompted MRI and CT imaging, which revealed lytic lesions. His clinical and radiological presentation mimicked, and was originally approached, as if it were a malignancy. Metastasis or multiple myeloma were considered the most likely differential diagnoses. As a result, the patient underwent surgical exploration. Pathology results indicated the presence of a fungal infection, without evidence of malignancy. PCR confirmed the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. The patient began treatment with fluconazole 800 mg daily and is anticipated to receive antifungal treatment for an indefinite period.

Keywords: Disseminated vertebral coccidioidomycosis, San Joaquin Valley fever, Coccidioides, Malignancy, Medication noncompliance, Immunocompromised

Introduction

Coccidioides is a dimorphic fungus that exists as mycelia or spherules and causes coccidioidomycosis, also known as San Joaquin Valley fever [1]. Coccidioidomycosis is endemic to desert regions of the Western Hemisphere including areas of California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico [1]. Infection generally occurs via inhalation of aerosolized arthrospores [2]. In 2019, 20,003 people were diagnosed with coccidioidomycosis, likely an underestimate due to its typical asymptomatic presentation [3]. Of the reported cases, rates were highest in those older than 60 [3]. Over 95% of reported cases were from Arizona and California [3]. The majority of coccidioidomycosis infections are asymptomatic (estimated 60%), but when symptomatic can present similar to community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, with fever, cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain [1]. Symptoms generally appear between 7 and 21 days after exposure [1]. In approximately 1% of infections, hematogenous extra-pulmonary systemic dissemination occurs, involving skin, the musculoskeletal system, and the meninges [4]. Immunocompromised patients are at greatest risk for disseminated coccidioidomycosis [5]. Vertebral coccidioidomycosis dissemination has previously been shown to manifest as back pain, neck pain, radiculopathy, sensory disturbances, and motor weakness [4]. We report a case of disseminated coccidioidomycosis which mimicked, and was originally approached, as if it were a malignancy.

Case Presentation

A 42-year-old Caucasian male presented to his primary care physician in November of 2022 with complaints of fever, body aches, and chills. He denied having a sore throat or cough. He was tachycardic, and a chest X-ray showed bilateral patchy consolidations consistent with pneumonia. It is noteworthy that the patient lived in the Southwest United States, and regularly traveled throughout multiple states in the Southwest. Rapid Strep A, SARS-COV antigen, and Influenza A/B tests all returned negative results. At this time on CBC with differential, there was a normal WBC, elevated neutrophil count of 79% (reference 44%-72%), and a decreased lymphocyte count of 6.2% (reference 22%-41%). He was prescribed azithromycin, cefdinir, and Paxlovid.

In December of 2022, the patient returned to his primary care provider with complaints of left-sided back pain. He also reported subjective fevers. It was postulated the pain could be originating from the kidneys. Thus, a urine culture and KUB were ordered. KUB was unremarkable and urinalysis results indicated no growth. At this time, the patient had an elevated WBC of 13.1 K/uL (reference 4.8-10.8 K/uL), elevated absolute eosinophil count of 3.54 K/uL (reference 0.00-0.51 K/uL), elevated absolute basophil of 0.26 K/uL (reference 0.00-0.12 K/uL), a normal neutrophil count, and decreased lymphocyte count of 9.7% (reference 22%-41%).

In February 2023, the patient presented again with back pain. An MR lumbar spine was ordered and exhibited what was believed to be a neoplasm of uncertain behavior of the bone and articular cartilage. A follow-up CT lumbar spine was ordered and revealed a 10 mm lytic defect in the posterior L5 vertebral body with an associated soft tissue component extending into the right ventral epidural space (Fig. 1). The radiologist indicated that isolated metastasis or multiple myeloma should be considered. No other suspicious bony lesions were identified in the chest, abdomen, or pelvis, and no definitive primary source of malignancy was identified. The imaging report also indicated there was a pulmonary reticulonodular opacity in the left upper lobe/lingula with the configuration more suggestive of an infectious or inflammatory process rather than a malignant process; there were nonspecific mediastinal nodes which could be reactive; there was no adenopathy in the abdomen or pelvis; there was mild hepatic steatosis; and there were calcified gallstones.

Fig. 1.

CT images depict osteolytic lesions in the bone. (A) Axial CT image of the lumbar spine shows a lytic lesion in the posterior portion of the L5 vertebral body. (B) Sagittal image of the lumbar spine shows a lytic lesion in the posterior portion of the L5 vertebral body.

In March, a repeat MR lumbar spine revealed a marrow infiltrative process involving the dorsal aspect of L5 with the erosion of the posterior cortex of L5 and with the extension of the infiltrative process to the right central and paracentral epidural space with impingement upon the right S1 nerve in the lateral recess (Figs. 2 and 3). The infiltrative process encased the right L5 nerve root and neural foramen as well, which likely accounted for the patient's radicular symptoms. The differential diagnosis put forth by the radiologist included lymphoma, myeloma/plasmacytoma, and metastatic disease.

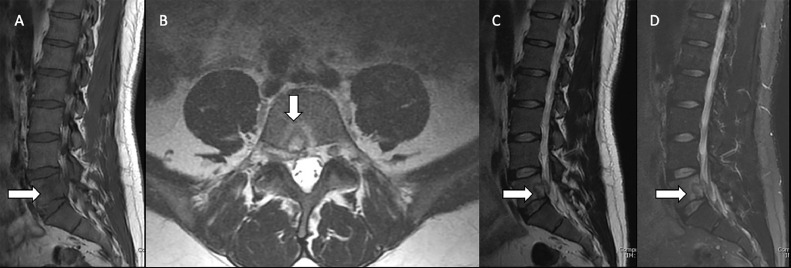

Fig. 2.

Precontrast MR images show focal abnormal lesion in the L5 vertebral body. (A) Sagittal T1 weighted sequences shows abnormal bone marrow edema in the L5 vertebral body. (B) Axial T2 weighted sequences shows a focal T2 hyperintense lesion with surrounding bone marrow edema in the L5 vertebral body. (C) Sagittal T2 weighted sequences shows a focal T2 hyperintensive lesion with surrounding bone marrow edema in the L5 vertebral body. (D) Sagittal fat saturated T2 weighted sequences shows a focal T2 hyperintensive lesion with surrounding bone marrow edema in the L5 vertebral body.

Fig. 3.

Postcontrast T1 weighted sequences show an enhancing lesion in the vertebral body and the adjacent epidural space. (A) Axial postcontrast T1 sequences shows an enhancing lesion in the L5 vertebral body and the adjacent ventral epidural space. (B) Sagittal fat suppressed T1 weighted sequences reveals an enhancing lesion in the L5 vertebral body and the adjacent ventral epidural space. (C) Sagittal postcontrast T1 weighted sequences reveals transforaminal extension of the epidural enhancing soft tissue.

In March, the patient presented to the emergency department with complaints of right-sided rib pain. CTA-CT indicated there was a new lytic lesion involving the posterior aspect of the right 11th rib that could be due to metastatic disease or multiple myeloma as described on previous MRI. It was also noted there was a possible slight interval enlargement of the left upper lobe pulmonary nodule from 6 to 7 mm.

As it was strongly suspected the patient's disease process was malignant in nature, the patient underwent a posterior partial lumbar 5 corpectomy “tumor” resection, fourth lumbar vertebrae through first sacral vertebrae fixation with stealth and hip bone marrow aspirate, and removal of the right chest wall posterior mass. The pre and postop diagnoses were “L5 vertebral body mass, right lower extremity radiculopathy, right rib mass.” Biopsy samples obtained intraoperatively were sent for examination.

Pathology indicated the intercostal muscles had skeletal muscle and granulation tissue demonstrating fungal organisms highlighted on PAS and GMS special stains. The rib mass was reported to resemble fungal infection favoring Coccidioides species, with bone and soft tissue demonstrating acute osteomyelitis and granulation tissue with fungal organisms highlighted on PAS and GMS special stains. The L5 spinous process indicated bone with marrow showing trilineage hematopoiesis and surrounding soft tissue without significant inflammation appreciated. The suspected epidural “tumor” yielded bone and soft tissue demonstrating acute osteomyelitis, areas of necrosis, and granulation tissue with fungal organisms highlighted on PAS and GMS special stains. AFB stains were negative for mycobacterial organisms. The right hip bone marrow aspirate exhibited bloody aspirate and no malignancy was identified. Flow cytometry showed no diagnostic immunophenotypic abnormalities and plasma cells demonstrated normal polyclonal cytoplasmic light chains.

Pathology indicated there was no evidence of plasma cell myeloma (multiple myeloma) or metastatic carcinoma. PAS and GMS were run on specimens where there was significant inflammation/granulation tissue suspicious for fungal organisms was high on H&E sections and fungal organisms were detected. H&E indicated the fungal organism was Coccidioides. A processed tissue block was sent for PCR testing for Coccidioides and the results were positive.

Accordingly, the patient had follow-up with infectious disease (ID) specialists. The ID team saw the patient and initiated fluconazole 800 mg daily. Follow-up MRI confirmed that treatment resolved the abnormal enhancement in the L5 vertebral body (Fig. 4). The ID team continues to closely monitor the patient, and anticipate long-term repeat lab work, imaging (CT chest and MRI of the spine), and fluconazole.

Fig. 4.

Post-treatment MR examination reveals near complete resolution of the abnormal enhancement. (A) Sagittal precontrast T1 weighted sequences reveal a well-defined T1 hypointense area without bone marrow edema in the L5 vertebral body. (B) Sagittal post-contrast T1 weighted sequences reveal minimal enhancement surrounding the T1 hypointensity in the L5 vertebral body.

Discussion

Coccidioides is a dimorphic fungus that causes coccidioidomycosis, also referred to as San Joaquin Valley Fever, and is endemic to California, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico [1]. Infection most commonly occurs by inhaling aerosolized arthrospores [2]. Following disruption of contaminated soil and dust caused by weather, people, or animals, Coccidioides spores circulate throughout the air [6]. This allows humans to breathe in the spores. Once the spores reach the lungs, they grow into spherules, which eventually can break open and release endospores that can be hematogenously disseminated to other parts of the body [6].

Although it is estimated that 60% of coccidioidomycosis infections are asymptomatic, symptomatic cases usually resemble community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, presenting with fever, cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain [1]. In roughly 1% of infections, hematogenous systemic dissemination occurs [2]. Disseminated vertebral coccidioidomycosis is most common in adults older than age 60, pregnant women, people who have diabetes, people who are Black or Filipino, and the immunocompromised (such as those with HIV/AIDS, organ transplants, and people taking corticosteroids or TNF-inhibitors). The aforementioned may also be at higher risk for developing severe infection [7]. It has been observed that spinal dissemination usually occurs in African American males [8].

Vertebral coccidioidomycosis dissemination has previously been shown to manifest as back pain, neck pain, radiculopathy, sensory disturbances, and motor weakness and may also cause discitis, paravertebral soft tissue infection, vertebral body erosion, and neural compression [2,8]. Coccidiomycosis dissemination can also result in meningitis [8]. On imaging, vertebral dissemination of coccidioidomycosis may be mistaken for malignancy, with the differential diagnosis including lymphoma, myeloma/plasmacytoma, and metastatic disease. In such situations, biopsy and careful pathology investigation is required to determine the origin of the vertebral lesion.

Management frequently consists of both surgical and medical interventions [5]. All patients with vertebral dissemination of coccidioidomycosis require medical therapy, given the risk of progressive morbidity and death [5]. For example, Martirosyan et al. reported in the available cases they evaluated, 3 of the 4 patients who did not undergo medical treatment died of sepsis, with the other being lost to follow-up [5]. Historically, the pharmacologic standard of care for this condition was amphotericin [5]. Now, standard treatment involves azole antifungals for at least 12-18 months after initial response to treatment in patients who are not immunocompromised, and a lifetime of azole use for patients who are immunocompromised [5]. A major limitation in the success of medical management in this condition is poor compliance with medications [2]. Relapse and worsening of infection are therefore common [2]. Spinal instability, neurologic compromise, severe pain, and lack of antifungal response are surgical indications for decompression, debridement, and fusion [9]. The utilization of repeat imaging, such as interval MRI, at regularly scheduled follow-ups has been supported in order to monitor lesions for stabilization, improvement, or deterioration [5].

Conclusion

Coccidioidomycosis is a fungal infection caused by the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides. Most cases are asymptomatic or present similarly to community-acquired pneumonia; however, in rare cases, hematogenous dissemination can occur, and has the potential to invade the vertebra. When spinal dissemination occurs, it elicits pain and may mimic malignancy. Careful history and evaluation must be undertaken in order to correctly identify coccidioidomycosis dissemination and to differentiate it from malignancy. Imaging is useful in the detection of dissemination and the location of lesions. Biopsy and subsequent PCR can help solidify diagnosis. Treatment of disseminated disease to the spine requires medical, and often surgical treatment. Antifungals such as fluconazole are useful to treat and prevent further spread and potential sepsis. Surgery is indicated for spinal instability and neurologic compromise [9].

Patient consent

Consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Akram SM, Koirala J. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2023. Coccidioidomycosis.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448161/ [Updated 2023 February 25] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramanathan D., Sahasrabudhe N., Kim E. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis to the spine-case series and review of literature. Brain Sci. 2019;9(7):160. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9070160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2022. Valley fever statistics.https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/statistics.html [accessed 10.12.23] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCotter O.Z., Benedict K., Engelthaler D.M., Komatsu K., Lucas K.D., Mohle-Boetani J.C., et al. Update on the epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis in the United States. Med Mycol. 2019;57(Supplement_1):S30–S40. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martirosyan N.L., Skoch J.M., Zaninovich O., Zoccali C., Galgiani J.N., Baaj A.A. A paradigm for the evaluation and management of spinal coccidioidomycosis. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:107. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.158979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2021. Where valley fever comes from.https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/causes.html [accessed 10.12.23] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 2022. Valley fever risk & prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/risk-prevention.html a. [accessed 10.12.23] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakya S.M., Sakya J.P., Hallan D.R., Warraich I. Spinal coccidioidomycosis: a complication from medication noncompliance. Cureus. 2020;12(7):e9304. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-del-Campo E., Kalb S., Rangel-Castilla L., Moon K., Moran A., Gonzalez O., et al. Spinal coccidioidomycosis: a current review of diagnosis and management. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.08.103. ISSN 1878-8750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]