Abstract

Purpose

The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on pre-existing retinal pathology is currently unknown.

Observations

We present a unique case of rapidly progressing diabetic retinopathy (DR) following severe COVID-19 infection requiring supplemental oxygen and subsequent long-COVID.

Conclusions and importance

Following infection with SARS-CoV-2, the associated acute and possible long-term hypoxia has the potential to affect the retina and accelerate the natural course of diabetic retinopathy.

Keywords: Retina, COVID-19, Long-COVID, Diabetic retinopathy, Hypoxia

1. Introduction

The human retina is exceptionally sensitive to hypoxia. Several disease processes result from insufficient oxygen reaching the retina including central retinal artery occlusion, ischemic central retinal vein thrombosis, and diabetic eye diseases.1

Most recently, COVID-19 infection has been a novel cause of hypoxemia with its short and long-term effects yet to be fully understood. Reports of central retinal vein occlusion, acute macular neuroretinopathy, and systemic thrombosis have been reported in the literature.2, 3, 4 These suggest the infection with SARS-CoV-2 may induce vascular injury and result in local retinal and systemic hypoxia. The phenomenon of long COVID, also known as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC), is defined as the persistence of symptoms for more than four weeks after initial infection. PASC also has been implicated in causing chronic hypoxemia.5

Below we describe a unique case of rapid, atypical progression of mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) in a patient following severe hospitalized COVID-19 infection.

2. Case report

A 50-year-old female with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and obesity with a body mass index (BMI) of 47.8 was infected with SARS-CoV-2 in January 2021. She presented to the emergency department following positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing with worsening cough, shortness of breath, fever up to 102.9o Fahrenheit, anosmia, dysgeusia, and some chest tightness. At this time the patient was hypoxemic to an oxygen saturation of 85% on room air and required 2L of oxygen to maintain an oxygen saturation greater than 90%. Work up revealed multifocal opacities on chest x-ray consistent with SARS-CoV-2 infection and an elevated c-reactive protein with all other inflammatory markers negative. The patient was then admitted to the hospital and remained on 2L of oxygen throughout her one-week hospital course. The patient gradually improved and was discharged one week following admission with 1L home oxygen for both rest and exertion.

In the months following discharge, the patient reported tachycardia and a persistent 1L oxygen requirement with exertion. She also noted that at night she would wake up gasping for air with an oxygen saturation of 80–85% on 1L oxygen, correcting to greater than 95% on 2L oxygen. In addition to her lingering hypoxemia, she reported consistent brain fog, anosmia, and dysgeusia suggestive of long COVID.

In April 2021, three months following discharge from hospital, she presented to the ophthalmology clinic for a routine diabetic eye exam prior to possible cataract surgery. Her visual acuity (VA) was 20/40 with no improvement with pinhole (NIPH) in her right eye and 20/40 with improvement to 20/25 on the left. Pupillary exam and intraocular pressure (IOP) were within normal limits. Fundus exam showed scattered dot-and-blot hemorrhages (DBHs) in two quadrants and intermittent microaneurysms (MA). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed no significant diabetic retinopathy and was without macular edema in both eyes (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of moderate NPDR was made in both eyes.

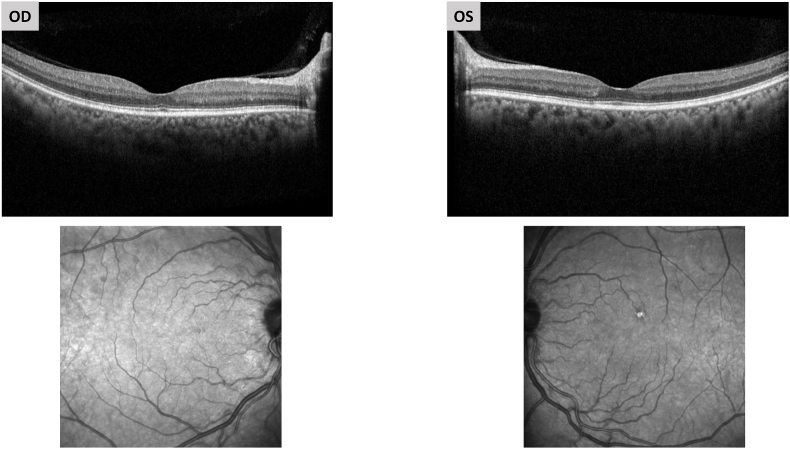

Fig. 1.

3 months after COVID-19 infection.

OCT and near infrared en face images taken shortly after COVID infection reveal no significant diabetic retinopathy and no macular hemorrhages.

The patient elected to proceed with cataract surgery, which was performed in May 2021 on her right eye and in June 2021 on her left eye. Post-operatively, VA pinholed to 20/25 on the right and 20/20 on the left. Fundus exam revealed new bilateral macular MAs without macular edema with stable peripheral hemorrhages.

In August 2021, the patient returned to clinic for a routine postoperative visit and reported new floaters in her left eye. Her VA was 20/25 on the right and 20/20 on the left. Fundus exam revealed marked appearance of new macular DBHs and MAs with diffuse peripheral DBHs and MAs in all 4 quadrants bilaterally. The patient was referred to the retina service and reported shortness of breath requiring an oral prednisone taper at that time. Upon presentation to the retina service the following month, the patient reported worsening visual acuity with a “blotch” in her right eye. She appeared dyspneic and was not compliant with use of her home oxygen at rest. VA had decreased to 20/30 in the right eye. Examination revealed hyperemic disc, multiple interspersed DBHs, and small pre-retinal hemorrhage inferior to the disc in the right eye with numerous DBHs in the left eye. OCT revealed worsening macular hemorrhages with new macular edema of the right eye (Fig. 2). Fluorescein angiogram showed retina transit time of 13 seconds with numerous microaneurysms, diffuse ischemia without neovascularization, and late staining of the disc in both eyes (Fig. 3). Hypercoagulability work-up was negative. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and carotid magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) were unremarkable and chest CT revealed possible bronchiolitis of unknown cause.

Fig. 2.

Approximately 6 months after COVID-19 infection.

OCT and near infrared en face images taken 6 months after COVID-19 infection showing dramatic increase in retinal hemorrhages in both eyes and new intraretinal cysts in the right eye.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescein Angiogram of the right eye on presentation to retina service September 2021.

Early frame (left) of the fluorescein angiogram demonstrates numerous microaneurysms. Later frames (right) reveal staining of the disc with diffuse areas of ischemia.

Three months following presentation to retina, the patient's VA was relatively stable at 20/30 with pinhole in both eyes. New neovascularization of the right disc (NVD) less than ¼ of a disc diameter was noted without associated preretinal hemorrhage. The retinal hemorrhages in both eyes were stable from presentation. OCT showed resolution of the macular edema in the right eye. Though she still endorsed some dyspnea, she had established care with a pulmonologist and was wearing O2 during exertion and at night with a BiPAP when sleeping. Given the absence of high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema, the decision was made to closely monitor.

The patient remained stable at monthly follow ups until she returned for an urgent visit 6 months following presentation to the retina service with decreased vision of the right eye. VA was 20/150 on the right NIPH and 20/25 on the left. There was now neovascularization of the iris in the right eye and florid NVD in both eyes with new vitreous hemorrhage in the right eye and preretinal hemorrhage in the left eye (Fig. 4). Deep juxtafoveal intraretinal hemorrhages were also present in both eyes. OCT showed no center involving macular edema of either eye. Given the rapid progression to high-risk PDR, the patient received bilateral injections with aflibercept. Two weeks after injection, the VA in the right eye worsened to CF with worsened vitreous hemorrhage while the NVD in the left eye had greatly improved. The patient was maintained on monthly intravitreal injections of aflibercept for two months until the vitreous hemorrhage had improved enough to initiate panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) of both eyes.

Fig. 4.

Color fundus photograph of both eyes.

Color fundus photography of both eyes shows NVD with new deep intraretinal juxtafoveal hemorrhages. The media is hazy in the right eye due to vitreous hemorrhage. There is a sliver of preretinal hemorrhage in the left eye. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Eighteen months after initial presentation (Fig. 5), VA had stabilized to 20/500 in the right eye and 20/200 in the left eye. She received 3 PRP treatments and 8 intravitreal injections in the right eye and 2 PRP treatments and 8 intravitreal injections in the left eye. The NVI in the right eye had regressed. In both eyes, the NVD had fibrosed with resolution of preretinal hemorrhage and significant improvement of intraretinal hemorrhage. OCT showed an intact foveal contour of both eyes with attenuation of the ellipsoid zone in the right eye. There was no macular edema in both eyes. Patient continued to use home O2 at night with a CPAP machine.

Fig. 5.

OCT 18 months after presentation.

OCT shows regressed neovascularization of the disc and preserved foveal contour in both eyes. There is central ellipsoid attenuation in the right eye.

3. Discussion

We present a case of rapidly progressive diabetic retinopathy in the setting of recent severe COVID-19 infection necessitating the continued use of home oxygen with subsequent long COVID. Prior to COVID-19 infection, our patient had annual diabetic eye exams with mild to moderate nonproliferative retinopathy noted. Approximately 6 months after COVID-19 infection, the patient had a dramatic progression to severe diabetic retinopathy with diffuse ischemia noted on fluorescein angiogram. Within 12 months of COVID-19 infection, she developed high risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy with preretinal hemorrhage in both eyes and anterior segment neovascularization ultimately requiring treatment.

It has been observed that between 7% and 55% of COVID-19 infections involve the retina.6 Patients with more critical infection had a higher incidence of retinal involvement.6 Common findings in these patients include retinal hemorrhage and cotton wool spots, suggesting microangiopathy as a potential mechanism.6 This hypothesis has support in the literature, as a reduction in the foveal and parafoveal superficial and deep capillary plexus vessel densities has been observed in a cohort of 31 patients who had recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection.6,7 This finding in patients who had recovered from COVID-19 suggests that permanent structural changes ultimately causing retinal hypoxia can result from acute infection, particularly in severe cases.

Our patient had multiple pre-existing comorbidities that likely worsened the severity of her COVID-19 infection and contributed to her rapid visual deterioration. During this period, her diabetes was poorly controlled with hemoglobin A1C between 9.2 and 11.3. She was also morbidly obese with obstructive sleep apnea, which may have also increased her baseline level of inflammatory cytokines. After recovering from her acute infection, she reported frequent night-time episodes with oxygen saturation consistently dropping to the low 80s. This was the first time she had experienced such episodes despite her longstanding OSA, suggesting her COVID-19 pneumonitis had a significant impact. Although the patient had been provided home oxygen, she frequently looked dyspneic at office visits suggesting lack of compliance and persistent hypoxemia. These systemic conditions in addition to local ocular changes secondary to recent cataract extraction likely created a hypoxic and inflammatory background that allowed for rapid worsening of her retinopathy.

In patients with complex medical co-morbidities, COVID-19 infection can lead to a negative feedback spiral due to chronic hypoxia resulting in exacerbation of pre-existing medical conditions that can further worsen COVID-19 associated sequelae. Ophthalmologists should carefully monitor these high-risk patients with a low threshold for intervention to prevent permanent retinal damage and vision loss. Finally, close co-management of systemic conditions with a primary care physician or specialist is critical to ensure improvement of the underlying disease process.

4. Conclusions

Severe COVID-19 infection can result in chronic hypoxemia and may contribute to rapid progression of pre-existing diabetic retinopathy. Further research is needed to elucidate the role of COVID-19 infection on retinal ischemia.

Patient consent

Consent to publish this case report was not obtained. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient.

Funding

This report was partially funded by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Authorship

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Kaur C., Foulds W.S., Ling E.A. Hypoxia-ischemia and retinal ganglion cell damage. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(4):879–889. doi: 10.2147/opth.s3361. Accessed 3/31/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ullah I., Sohail A., Shah M.U.F.A., et al. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion in patients with COVID-19 infection: a systematic review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;71 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David J.A., Fivgas G.D. Acute macular neuroretinopathy associated with COVID-19 infection. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2021.101232. Accessed 3/31/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts K.A., Colley L., Agbaedeng T.A., Ellison-Hughes G.M., Ross M.D. Vascular manifestations of COVID-19 - thromboembolism and microvascular dysfunction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.598400. Published 2020 Oct 26. Accessed 3/31/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C., Yu C., Jing H., et al. Long COVID: the nature of thrombotic sequelae determines the necessity of early anticoagulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.861703. Published 2022 Apr 5. Accessed 3/31/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feroze K.B. Retinal manifestations of COVID-19 disease - a review of available information. Kerala J Ophthalmol. May–Aug 2021;33(2):132–138. doi: 10.4103/kjo.kjo_131_21. Accessed 3/31/23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapata M.Á., Banderas García S., Sánchez-Moltalvá A., et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities in patients after COVID-19 depending on disease severity. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106(4):559–563. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]