Abstract

Objective

To investigate the targets and mechanism of Achyranthis bidentatae radix and Morindae officinalis radix (ABR-MOR) for the treatment of osteoporosis (OP) by utilizing network pharmacology, molecular docking technology (MDT) and molecular dynamics simulation (MDS).

Methods

The main drug active ingredients (DAIs) and target genes of ABR-MOR were screened by the TCMSP database. The relevant targets of OP were obtained from GeneCards, DisGeNET, and CTD databases. Venny mapping is used to determine the potential target of ABR-MOR in the treatment of OP. The potential targets were analyzed using a protein‒protein interaction network and the MCODE module, and were subjected to GO and KEGG enrichment analysis. The binding sites and conditions of potential key DAIs and core targets were verified through MDT and MDS.

Result

The 32 DAIs and 212 targets of ABR-MOR were screened; 1453 OP-related targets were obtained, and 118 targets were mapped. The results of GO and KEGG enrichment analysis showed that the targets of DAIs-OP were mainly enriched in biological processes such as response to hormones, peptides, oxygen levels and reactive oxygen species, and positive regulation of cell migration. The main signaling pathways enriched in the regulation of the immune-inflammatory response, cell proliferation, senescence, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and estrogen signaling pathway. Additionally, the targets were also enriched in bone metabolism-related cell differentiation biological processes and the osteoclast differentiation signaling pathway. MDT and MDS results showed that wogonin, beta-sitosterol, and americanin A, the core DAIs of ABR-MOR, were able to form good ligand‒protein complexes with key targets such as PTGS2, PTGS1, PRKACA, PGR, MAPK1, AKT1, and RELA.

Conclusion

This study preliminarily investigated the key targets, biological processes, and signaling pathways involved in the combined application of ABR and MOR for the treatment of OP. The results revealed that ABR-MOR may play a therapeutic role mainly by regulating immune-inflammatory responses, cellular biological processes, and osteoblast differentiation, which provides a theoretical basis for further experimental validation and a new strategy for the treatment of OP.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Herbal formula, Ba ji tian liquor, Achyranthis bidentatae radix, Morindae officinalis radix, Network pharmacology, Molecular docking technique, Molecular dynamics simulation

Highlights

-

•

ABR-MOR, the main herbs in traditional Chinese herbal formula Ba Ji Tian Liquor, can treat OP.

-

•

The mechanism of ABR-MOR treating OP is closely related toinflammatory responses, cell processes, and cell differentiation.

-

•

The mechanism of ABR-MOR in OP was analyzed by computer method for the first time.

-

•

Wogonin, beta-sitosterol, and americanin A are potential active ingredients for the anti-OP effect of ABR-MOR.

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic bone disease caused by an imbalance in bone metabolism, which is categorized as “bone withering” and “bone paralysis” in the traditional Chinese medical (TCM) classic “Huang Di Nei Jing-Suwen” [1]. Its characteristics include bone microstructure damage, increased bone brittleness, and decreased bone mass, which are more common in postmenopausal women and elderly men [2]. With the aging population and the extension of life span, China has become the country with the largest elderly population in the world. The prevalence of osteoporosis in people over 65 years old is 32 %, including 51.6 % for women and 10.7 % for men [2,3]. Osteoporosis has become one of the most prevalent diseases not only in China but also in the world, seriously affecting people's daily lives and adding great economic and social burdens [[4], [5], [6], [7]].

With the development of medical research, an increasing number of scholars are paying attention to the therapeutic effect of TCM in the field of osteoporosis. The core concept of TCM in treating OP is the legislation of tonifying the Shen (kidney) and Pi (spleen), replenishing the Jing (essence) and Sui (marrow), invigorating Qi, and promoting blood circulation. The traditional diagnosis and treatment concept of TCM syndrome differentiation has unique advantages in the prevention and treatment of OP [8]. The TCM formula “Ba Ji Tian (Morindae officinalis radix, MOR) Liquor”, recorded in “Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang” and “Sheng Ji Zong Lu”, uses MOR and Achyranthis bidentatae radix (ABR) as the main herbs for compatibility. This formula has functions that include “tonifying the kidney, promoting blood circulation, relaxing the tendons, and facilitating joints. It is mainly used for treating fractures, trauma, lumbocrural pain, foot weakness, limb weakness, contracture, and kidney deficiency and impotence” [9,10]. Studies have confirmed that extracts of ABR and MOR can promote the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and reduce or inhibit the activity of osteoclasts. Supplementing ABR or MOR extract to the osteoporosis rat model can reduce bone loss, increase bone mineral accumulation, and improve bone density [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. However, it remains unclear which of the main drug active ingredient (DAIs) of ABR-MOR are involved in treating OP and whether other important DAIs can improve OP.

Therefore, this study employed the network pharmacological analysis (NPA), molecular docking technique (MDT), and molecular dynamics simulation (MDS) to screen the active components of ABR-MOR, predicted the potential molecular regulatory mechanism for treating OP, and then provided a new scientific basis and new ideas for the molecular regulatory network of ABR-MOR in treating OP, and provided a theoretical basis for further experiments in vitro and in vivo. The scheme flow of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of network pharmacology prediction of ABR-MOR for osteoporosis treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Screening of the main DAIs of ABR-MOR and their predictive targets

All chemical components of ABR-MOR were obtained through the database of the traditional Chinese medicine system pharmacology and analysis platform (TCMSP, https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php) [15], and two ADME attribute values (oral bioavailability, (OB) ≥ 30 %, and drug-like index (DL) ≥ 0.18) were preliminarily screened to determine DAIs. The corresponding targets of these DAIs were then obtained from the TCSMP database. The target protein names were standardized by the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). The obtained target data were imported into Cytoscape 3.8.1 software to construct a DAI-target network.

2.2. Screening of OP-related targets

The GeneCards database (https://www.Genecards.Org/; Relevance Score >1, Category set to Protein Coding), the DisGeNET database (https://www.disgenet.org/; Gene-Disease Association Score >0.1), and the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, https://www.ctdbase.org/; Inference Score >50) were searched, and OP-related genes were collected using the keyword “Osteoporosis”. The OP-related targets were then normalized by the UniProt database and de-emphasized to obtain OP-related target genes.

2.3. Target screening and protein‒protein interaction (PPI) network analysis of ABR-MOR in the treatment of OP

The Venny 2.1 platform (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) was used to draw a Venny diagram to obtain the potential target of ABR-MOR in the treatment of OP. The obtained target was then uploaded to the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/) with the protein type “homo sapiens”, and a single node was removed under the default parameter setting to obtain the PPI network and data [16]. Protein interaction data were imported into Cytoscape 3.8.1 software for visualization. The potential protein function module was obtained by analyzing the interaction network through the MCODE plug-in, and the topological parameters of the protein interaction network were analyzed through the CytoNCA plug-in.

2.4. Enrichment analysis of GO functions and KEGG pathways

The functional enrichment of gene ontology (GO) and the pathway enrichment of Kyoto gene and gene encyclopedia (KEGG) were performed on the target genes using the Metascape platform (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html) [17]. The GO enrichment analysis mainly consisted of three parts, namely, biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). The results of the enrichment analysis were further visualized using the Bioinformatics platform (https://www. bioinformatics.com.cn/).

2.5. Constructing the disease-drug-DAI-target interaction network

The interactive network of “OP-drug(ABR-MOR)-DAI-target” was constructed by Cytoscape 3.8.1 software and analyzed by the CytoNCA plug-in to calculate the degree centrality value (DCV), betweenness centrality value (BCV) and closeness centrality value (CCV) of each node. The important DAIs and core targets were subsequently identified and selected by these measures.

2.6. MDT verification

Based on the previous screening results of network pharmacology, the crystal structure of the target protein was obtained from the RCSB PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/). The 3D structure of ABR-MOR potential DAIs was downloaded from the TCMSP database. Open Babel 2.4.0 software was used to convert the conformation of DAIs into PDB format and hydrogenated by AutoDockTools 1.5.7 software. The twisted bond was detected and set to allow for a certain range of conformational changes in the ligand. PyMol 2.4.1 software was used to remove water molecules and original ligands with protein structures before importing AutoDockTools software for hydrogenation and other operations. Molecular docking was also carried out using AutoDockTools software, and the results were visualized by PyMol 2.4.1 software and LigPlot + v.2.2.4. platform (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/software/LigPlus/) [18]. The evaluation of whether small-molecule DAIs can bind to macromolecular target proteins mainly relies on the binding energy. A binding energy <0 indicates that the ligand and receptor can spontaneously bind. The lower the binding energy is, the stronger the affinity and the greater the possibility of action.

2.7. MDS verification

Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted on receptor proteins using the GROMACS 2020.3 software package. The receptor proteins chosen were those that exhibited the highest binding energies to ligand molecules based on the molecular docking results. The initial structures for the simulations were obtained from the molecular docking results to determine the binding modes and energies of the proteins. The parameterization of proteins and small molecules was carried out using the AMBER99SB force field. The solvated water model, specifically the SPOC model, was employed to dissolve the protein‒ligand complex in the cubic water model. After minimizing the volume of the water model, energy minimization was performed. Following this, the system underwent 2000 ps of molecular dynamics simulations under vacuum. To achieve equilibration, the system was then subjected to molecular dynamics simulations for 30 ns at a temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1.0 atm using the conventional system (NVT) and the isothermal isobaric system (NPT) for 1,000,000 steps. Finally, the visualizations were conducted using Origin 2022 software.

3. Result

3.1. Major DAIs of ABR-MOR and their predictive targets

A total of 176 DAIs for ABR and 174 DAIs for MOR were obtained through the TCMSP database search. Based on the screening of ADME attribute values and discarding the DAIs with no gene target reported, 32 major DAIs of ABR-MOR were finally identified in combination with relevant literature reports (Table 1). The major DAIs of ABR corresponded to 437 targets, and the major DAIs of MOR corresponded to 145 targets. After deduplication and UniProt database normalization, a total of 212 valid targets were finally obtained for the major DAIs of ABR-MOR (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Drug active ingredients of ABR-MOR.

| Herb | Mol ID | Molecule Name | Molecule structure | MW | OB (%) | DL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABR | MOL001006 | poriferasta-7,22E-dien-3beta-ol |  |

412.77 | 42.98 | 0.76 |

| MOL012461 | 28-norolean-17-en-3-ol |  |

412.77 | 35.93 | 0.78 | |

| MOL001454 | berberine |  |

336.39 | 36.86 | 0.78 | |

| MOL001458 | coptisine |  |

320.34 | 30.67 | 0.86 | |

| MOL000173 | wogonin |  |

284.28 | 30.68 | 0.23 | |

| MOL002643 | delta 7-stigmastenol |  |

414.79 | 37.42 | 0.75 | |

| MOL002714 | baicalein |  |

270.25 | 33.52 | 0.21 | |

| MOL002776 | Baicalin |  |

446.39 | 40.12 | 0.75 | |

| MOL002897 | epiberberine |  |

336.39 | 43.09 | 0.78 | |

| MOL003847 | Inophyllum E |  |

402.47 | 38.81 | 0.85 | |

| MOL000422 | kaempferol |  |

286.25 | 41.88 | 0.24 | |

| MOL004355 | Spinasterol |  |

412.77 | 42.98 | 0.76 | |

| MOL000449 | Stigmasterol |  |

412.77 | 43.83 | 0.76 | |

| MOL000785 | palmatine |  |

352.44 | 64.6 | 0.65 | |

| MOL000085 | beta-daucosterol_qt |  |

414.79 | 36.91 | 0.75 | |

| MOL000098 | quercetin |  |

302.25 | 46.43 | 0.28 | |

| ABR-MOR | MOL000358 | beta-sitosterol |  |

414.79 | 36.91 | 0.75 |

| MOR | MOL002879 | Diop |  |

390.62 | 43.59 | 0.39 |

| MOL002883 | Ethyl oleate (NF) |  |

310.58 | 32.4 | 0.19 | |

| MOL000359 | sitosterol |  |

414.79 | 36.91 | 0.75 | |

| MOL006147 | Alizarin-2-methylether |  |

254.25 | 32.81 | 0.21 | |

| MOL009495 | 2-hydroxy-1,5-dimethoxy-6-(methoxymethyl)-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

328.34 | 95.85 | 0.37 | |

| MOL009496 | 1,5,7-trihydroxy-6-methoxy-2-methoxymethylanthracenequinone |  |

330.31 | 80.42 | 0.38 | |

| MOL009500 | 1,6-dihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-(methoxymethyl)-9,10-anthraquinone |  |

254.25 | 104.33 | 0.21 | |

| MOL009504 | 1-hydroxy-6-hydroxymethylanthracenequinone |  |

254.25 | 81.77 | 0.21 | |

| MOL009513 | 2-hydroxy-1,8-dimethoxy-7-methoxymethylanthracenequinone |  |

328.34 | 112.3 | 0.37 | |

| MOL009519 | (2R,3S)-(+)-3′,5-Dihydroxy-4,7-dimethoxydihydroflavonol |  |

332.33 | 77.24 | 0.33 | |

| MOL009524 | 3beta,20(R),5-alkenyl-stigmastol |  |

414.79 | 36.91 | 0.75 | |

| MOL009525 | 3beta-24 S(R)-butyl-5-alkenyl-cholestol |  |

456.88 | 35.35 | 0.82 | |

| MOL009537 | americanin A |  |

328.34 | 46.71 | 0.35 | |

| MOL009551 | isoprincepin |  |

494.53 | 49.12 | 0.77 | |

| MOL009562 | Ohioensin-A |  |

372.39 | 38.13 | 0.76 |

Table 2.

Enrichment analysis results of predicted targets in the differentiation of bone metabolism-related cells.

| Category ID | Description | LogP | Enrichment | Z-score | %InGO | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa04380 | Osteoclast differentiation | −24.24 | 38.05 | 26.29 | 16.10 | AKT1|CHUK|MAPK14|FOS|IFNG|IKBKB|IL1A|IL1B|NFATC1|NFKBIA|PPARG|MAPK1|MAPK8|RELA|STAT1|TGFB1|TNF|FOSL1|NCF1 |

| hsa04370 | VEGF signaling pathway | −17.17 | 52.13 | 24.60 | 10.17 | AKT1|CASP9|MAPK14|HSPB1|KDR|NOS3|PRKCA|PRKCB|MAPK1|PTGS2|RAF1|VEGFA |

| hsa04550 | Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | −4.67 | 10.75 | 7.32 | 5.08 | AKT1|MAPK14|GSK3B|MYC|MAPK1|RAF1 |

| GO:0001649 | osteoblast differentiation | −8.41 | 16.72 | 11.58 | 7.63 | ACHE|AKT1|RUNX2|COL1A1|MAPK14|IGF2|IGFBP3|SPP1|NR1I3 |

| GO:0045667 | regulation of osteoblast differentiation | −3.54 | 8.72 | 5.87 | 4.24 | RUNX2|IL6|PPARG|PRKACA|TNF |

| GO:0045672 | positive regulation of osteoclast differentiation | −3.75 | 27.46 | 8.77 | 2.54 | FOS|IFNG|TNF |

| GO:0030316 | osteoclast differentiation | −2.91 | 14.24 | 6.09 | 2.54 | MAPK14|FOS|TNF |

| GO:0048863 | stem cell differentiation | −6.19 | 11.20 | 8.67 | 6.78 | BCL2|RUNX2|MAPK14|ESR1|FN1|HIF1A|MAPK1|TP53 |

| GO:0048864 | stem cell development | −3.46 | 12.06 | 6.39 | 3.39 | BCL2|FN1|HIF1A|MAPK1 |

| GO:0072089 | stem cell proliferation | −2.58 | 10.98 | 5.23 | 2.54 | RUNX2|KDR|TP53 |

| GO:0002062 | chondrocyte differentiation | −6.07 | 18.75 | 10.08 | 5.08 | RUNX2|COL3A1|MAPK14|HIF1A|RB1|TGFB1 |

| GO:0045651 | positive regulation of macrophage differentiation | −6.41 | 64.08 | 15.79 | 3.39 | CASP8|PRKCA|RB1|TGFB1 |

| GO:0030225 | macrophage differentiation | −4.70 | 25.01 | 9.63 | 3.39 | CASP8|IFNG|MMP9|VEGFA |

| GO:0045601 | regulation of endothelial cell differentiation | −5.95 | 27.27 | 11.28 | 4.24 | IKBKB|IL1B|TNF|VEGFA|XDH |

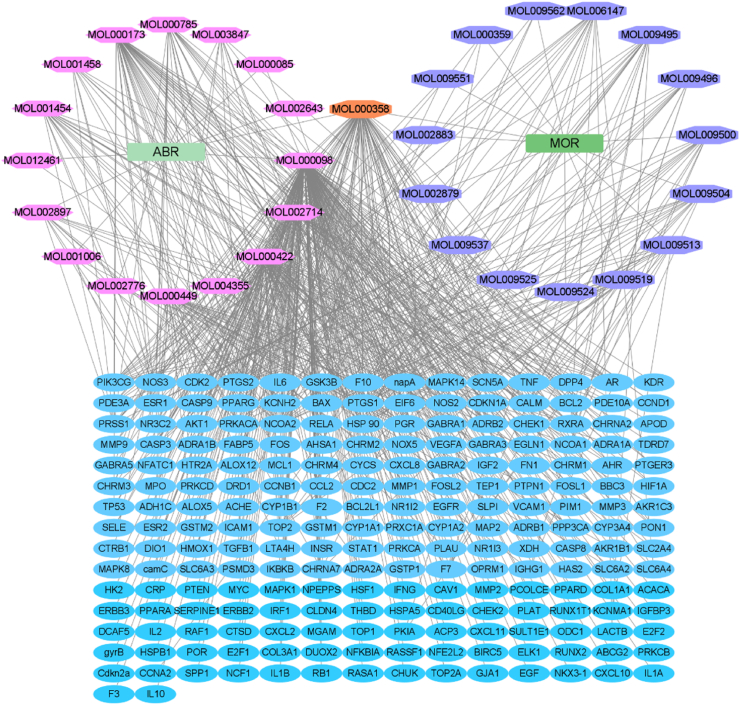

3.2. Construction of “DAI-target” network of ABR-MOR

The obtained 212 targets and DAIs were imported into Cytoscape software, and a “DAI-target” visualization network was constructed (Fig. 2). In the visualization network, there were 246 nodes and 615 edges. Among them, the pink nodes represent the DAIs of ABR, the purple nodes represent the DAIs of MOR, the orange nodes represent the common DAIs of ABR and MOR, and the light blue nodes represent the targets. Further topological analysis using the CytoNCA plug-in revealed that the three DAIs with the highest number of acting targets were quercetin, beta-sitosterol, and kaempferol, and the three targets with the highest number of mapped DAIs were PTGS2, NCOA2, and PTGS1.

Fig. 2.

Drug(ABR-MOR)-DAI-target network.

3.3. Potential target of ABR-MOR in the treatment of OP and the construction of the PPI network

According to the GeneCards database, DisGeNET database, and CTD database, a total of 1194, 137, and 387 OP-related targets were screened, respectively. A total of 1453 targets were obtained after deduplication. A Venny diagram was used to map ABR-MOR-related targets with OP-related targets and obtained 118 targets (Fig. 3). Subsequently, the obtained targets were imported into the STRING database to construct a PPI network (Fig. 4A) and visualized by Cytoscape software. Targets in the PPI were analyzed using the CytoNCA plug-in and sorted according to the topological parameters (Fig. 4B). According to DCV, BCV, and CCV, the top 20 targets are TP53, TNF, AKT1, EGFR, IL-1B, MYC, FN1, PTGS2, RELA, IL-6, MAPK1, CAV1, CASP3, VEGFA, FOS, PPARA, MMP9, NFKBIA, MAPK8, and RXRA (Fig. S1, Supporting Information). These targets are mainly enriched in the IL-17 signaling pathway and the TNF signaling pathway, which are immune inflammation-related signaling pathways. Relative to the PPI network, a module has two biological meanings: one is a protein complex, in which multiple proteins work together to form a complex and synergize their biological roles; the other is a functional module, such as proteins that are in the same pathway and interact more closely with each other [19]. The PPI network was analyzed via the MCODE plug-in of Cytoscape software to obtain modules (Fig. 4B). These modules provide insights into the mechanism of ABR-MOR in treating OP.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram of ABR-MOR targets and OP targets.

Fig. 4.

Potential target of ABR-MOR in the treatment of OP. A) PPI network from the STRING database; B) PPI network visualized by Cytoscape software, with darker and larger nodes representing higher levels of cores; C) Target modules obtained from PPI network analysis.

3.4. Enrichment analysis of predictive targets of ABR-MOR for OP treatment

The Metascape platform was utilized to conduct GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway enrichment of ABR-MOR DAIs in treating OP. The GO function enrichment analysis showed that 1623 biological processes, 61 cellular components, and 149 molecular functions were enriched, and the top 15 of them were chosen for presentation after being ranked by corrected P values. DAI-OP targets participating in BPs mainly include “response to hormone”, “cellular response to lipid”, “response to peptide”, “response to lipopolysaccharide”, “response to oxygen levels”, “response to decreased oxygen levels”, “positive regulation of cell migration”, “response to reactive oxygen species”, “response to bacterium”, and “positive regulation of cell motility”. Those affecting the CCs mainly include “membrane raft”, “membrane microdomain”, “transcription regulator complex”, “vesicle lumen”, “secretory granule lumen”, “cytoplasmic vesicle lumen”, “extracellular matrix”, “caveola”, “protein kinase complex”, “collagen-containing extracellular matrix”, and “serine/threonine protein kinase complex”. Those participating in MFs are mainly “DNA-binding transcription factor binding”, “RNA polymerase II-specific DNA-binding transcription factor binding”, “transcription factor binding”, “transcription coregulator binding”, “kinase binding”, “cytokine receptor binding”, “protein domain specific binding”, “protein kinase binding”, “nuclear receptor activity”, “ligand-activated transcription factor activity”, “protein homodimerization activity”, “signaling receptor regulator activity”, “kinase regulator activity”, “signaling receptor activator activity” and “cytokine activity” (Fig. 5). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that 204 signaling pathways were enriched. Twenty main potential pathways for the mechanism of ABR-MOR for OP treatment are the “AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications”, “IL-17 signaling pathway”, “TNF signaling pathway”, “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway”, “MAPK signaling pathway”, “Apoptosis”, “C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway”, “Relaxin signaling pathway”, “Cellular senescence”, “FoxO signaling pathway”, “HIF-1 signaling pathway”, “p53 signaling pathway”, “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway”, “EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance”, “NF-kappa B signaling pathway”, “NOD-like receptor signaling pathway”, “Thyroid hormone signaling pathway”, “VEGF signaling pathway”, “Estrogen signaling pathway”, and “Ras signaling pathway” (Fig. 6A). According to the “pathway-target” chord diagram constructed by the core pathway and the mapped targets, the three targets most involved in the core pathway were MAPK1, AKT1, and RELA (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 5.

GO function enrichment analysis of ABR-MOR's targets in the treatment of OP.

Fig. 6.

A) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of ABR-MOR's targets in the treatment of OP; B) Pathway-target chord diagrams.

Further analysis of the target function and pathway enrichment results revealed that ABR-MOR's DAIs have a regulatory effect on bone synthesis/catabolism. We noted that 19 predicted targets were enriched in the KEGG pathway of “osteoclast differentiation” (Fig. S2), 12 targets in the “VEGF signaling pathway” (Fig. S3), and 6 targets in the “signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells”. Additionally, 14 targets were related to the biological process of “osteoblast differentiation”, 4 targets to “osteoclast differentiation”, 6 targets to “chondrocyte differentiation”, 7 targets to “macrophage differentiation”, and 5 targets to " endothelial cell differentiation”. Therefore, DAIs of ABR-MOR may be closely related to the regulation of the balance of osteogenic differentiation/osteoclast differentiation, which makes them have a potential role in the treatment of OP.

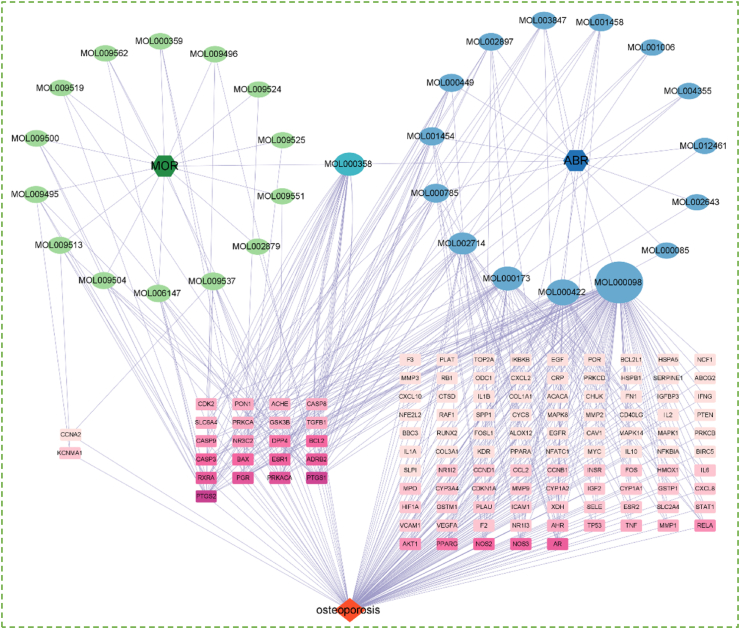

3.5. Disease-drug (ABR-MOR)-DAI-target interaction network

The disease-drug (ABR-MOR)-DAI-target interaction network is shown in Fig. 7. Ethyl oleate (NF) (MOL002883) and baicalin (MOL002776) were excluded because there were no corresponding targets in the mapping of ABR-MOR to OP. Core DAIs (Table 3) and core targets (Table 4) were obtained by analyzing topological parameters and excluding DAIs and targets with BCV = 0. The results showed that the DAIs most strongly connected to OP by ABR were quercetin, kaempferol, and wogonin, while the DAIs most strongly connected to OP by MOR were beta-sitosterol, americanin A, and Alizarin-2-methylether (Table 3). The top three predicted targets for DCV and CCV were PTGS2, PTGS1, and PRKACA. Furthermore, the top three predicted targets for BCV were PTGS2, PTGS1, and PGR (Table 4).

Fig. 7.

Disease-drug-DAI-target interaction network. Different shapes of nodes represent different objects, hexagons for drugs, ellipses for DAIs, and rectangles for disease target genes; the larger the area and the darker the color indicate that the node is more important. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Table 3.

Characteristic parameters of DAIs nodes in disease-drug-DAIs-targets network.

| MOL-ID | Degree Centrality | Betweenness Centrality | Closeness Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABR-MOL000098 | 98 | 14551.1240 | 0.2780 |

| ABR-MOL000422 | 38 | 3056.9238 | 0.2321 |

| ABR-MOL000173 | 31 | 2513.2324 | 0.2231 |

| ABR-MOR-MOL000358 | 28 | 1635.1665 | 0.2166 |

| ABR-MOL002714 | 23 | 1583.0620 | 0.2172 |

| ABR-MOL000785 | 11 | 357.3198 | 0.2105 |

| ABR-MOL001454 | 9 | 86.9812 | 0.2093 |

| ABR-MOL000449 | 8 | 776.8329 | 0.2135 |

| MOR-MOL009537 | 7 | 374.9620 | 0.2075 |

| ABR-MOL002897 | 7 | 50.9571 | 0.2075 |

| MOR-MOL006147 | 6 | 57.3978 | 0.2069 |

| ABR-MOL003847 | 6 | 144.8319 | 0.2069 |

| ABR-MOL001458 | 6 | 42.3804 | 0.2069 |

| MOR-MOL009513 | 4 | 147.4665 | 0.2058 |

| MOR-MOL009504 | 4 | 8.2870 | 0.2064 |

| MOR-MOL009495 | 4 | 147.4665 | 0.2058 |

| MOR-MOL009500 | 3 | 2.4665 | 0.2052 |

| MOR-MOL009562 | 2 | 0.2080 | 0.2047 |

| MOR-MOL009519 | 2 | 0.2080 | 0.2047 |

| MOR-MOL009496 | 2 | 0.2080 | 0.2047 |

| MOR-MOL000359 | 2 | 23.2588 | 0.1678 |

| ABR-MOL004355 | 2 | 23.2588 | 0.1678 |

Table 4.

Characteristic parameters of target nodes in disease-drug-DAIs-targets network.

| Gene | Degree Centrality value | Betweenness Centrality value | Closeness Centrality value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTGS2 | 21 | 2023.4489 | 0.2551 |

| PTGS1 | 19 | 1703.5990 | 0.2525 |

| PRKACA | 13 | 929.9431 | 0.2475 |

| PGR | 11 | 2020.4799 | 0.1997 |

| RXRA | 10 | 554.6250 | 0.2403 |

| ADRB2 | 9 | 660.2418 | 0.2380 |

| AR | 9 | 440.4197 | 0.2419 |

| ESR1 | 8 | 70.5951 | 0.1881 |

| NOS3 | 7 | 304.7564 | 0.2321 |

| CASP3 | 6 | 260.1022 | 0.2388 |

| BAX | 6 | 260.1022 | 0.2388 |

| BCL2 | 6 | 260.1022 | 0.2388 |

| NOS2 | 6 | 69.8757 | 0.2014 |

| DPP4 | 5 | 291.7130 | 0.2388 |

| PPARG | 5 | 213.7131 | 0.2335 |

| NR3C2 | 4 | 332.0284 | 0.1778 |

| AKT1 | 4 | 146.5254 | 0.2373 |

| RELA | 4 | 146.5254 | 0.2373 |

| CASP9 | 4 | 124.3405 | 0.2321 |

| ACHE | 3 | 315.3445 | 0.2278 |

| TP53 | 3 | 91.7961 | 0.2285 |

| MMP1 | 3 | 83.5120 | 0.2335 |

| TNF | 3 | 83.5120 | 0.2335 |

| AHR | 3 | 72.6011 | 0.2307 |

| PON1 | 3 | 58.5755 | 0.2251 |

| TGFB1 | 3 | 58.5755 | 0.2251 |

| PRKCA | 3 | 58.5755 | 0.2251 |

| CASP8 | 3 | 58.5755 | 0.2251 |

| GSK3B | 3 | 19.4018 | 0.1849 |

| CDK2 | 3 | 17.0759 | 0.1853 |

| SLC6A4 | 3 | 6.8894 | 0.1800 |

| PLAU | 2 | 77.2004 | 0.2258 |

| CXCL8 | 2 | 44.0750 | 0.2251 |

| CCL2 | 2 | 44.0750 | 0.2251 |

| IL6 | 2 | 44.0750 | 0.2251 |

| CDKN1A | 2 | 44.0750 | 0.2251 |

| CCND1 | 2 | 44.0750 | 0.2251 |

| IGF2 | 2 | 33.9643 | 0.2217 |

| MPO | 2 | 33.9643 | 0.2217 |

| CCNB1 | 2 | 33.9643 | 0.2217 |

| HIF1A | 2 | 33.9643 | 0.2217 |

| MMP9 | 2 | 33.9643 | 0.2217 |

| FOS | 2 | 33.9643 | 0.2217 |

| VEGFA | 2 | 33.9643 | 0.2217 |

| GSTM1 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| INSR | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| NR1I3 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| SLC2A4 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| GSTP1 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| NR1I2 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| VCAM1 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| SELE | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| ICAM1 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| CYP1A1 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| CYP1A2 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| CYP3A4 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| HMOX1 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| STAT1 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| XDH | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| F2 | 2 | 23.3445 | 0.2271 |

| ESR2 | 2 | 1.0910 | 0.1753 |

| KCNMA1 | 2 | 0.5000 | 0.1717 |

3.6. Verification results of MDT

A large number of previous studies have explored the application and molecular mechanism of quercetin and kaempferol as monomer drugs in the treatment of OP [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. TCM emphasizes the compatibility of various herbs, and different DAIs play different roles in disease treatment. Therefore, we intend to carry out molecular simulation docking of wogonin of ABR, beta-sitosterol of ABR-MOR, and americanin A of MOR on the core targets (MAPK1, AKT1, and RELA) that participate in the most pathways and the core targets (PTGS2, PTGS1, PRKACA, and PGR) that are most closely linked in the drug-target network. As shown in Fig. 8A, the binding energies of the selected DAI-targets were all less than 0, indicating potential binding between all DAIs and the target proteins, and most of them can form ≥2 hydrogen bonds (Fig. 8B). Excluding the possibility of false positives, we selected the top two DAI-protein complexes that formed ≥2 hydrogen bonds with the smallest binding energies for each DAI for visualization and analysis (Fig. 8C–H). The results showed that wogonin binds well to PTGS1 and AKT1, americanin A to AKT1 and PRKACA, and beta-sitosterol to PGR and MAPK1. These findings indicate that the three DAIs in ABR-MOR may exhibit a therapeutic role in OP by modulating these core targets.

Fig. 8.

Molecular docking technology (MDT) of selected DAIs of ABR-MOR with the core target protein. A) Heatmap of binding energy between DAIs and target protein; B) Heatmap of hydrogen bonding between DAIs and target proteins; C) MDT of beta-sitosterol-PGR; D) MDT of beta-sitosterol-MAPK1; E) MDT of americanin A-AKT1; F) MDT of americanin A-PRKACA; G) MDT of wogonin-PTGS1; H) MDT of wogonin-AKT1.

3.7. Verification results of the MDS

To validate the MDT and its visualization results, MDS was used for further probing (Fig. 9). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) curves reflected the dynamic changes in protein conformation. The results showed that the binding of wogonin to PTGS1 was stable after 5 ns and to AKT1 after 15 ns, and the binding was stronger. beta-sitosterol remained stable with MAPK1 after 10 ns, and the binding to PGR was stabilized at 5 ns. Americanin A was stabilized with AKT1 after 10 ns and with PRKACA after 5 ns. The binding of Americanin A to AKT1 was stabilized after 10 ns and to PRKACA after 5 ns. From the RMSD curves, it can be seen that the conformational fluctuations of wogonin-PTGS1, beta-sitosterol-PGR, and americanin A-PRKACA were smaller. The RMSD curves were smooth throughout the simulation, indicating that these small molecules could be stably bound to the proteins in the active pocket without dissociation (Fig. 9A). The protein solvent accessible surface area (SASA) analysis of the trajectories showed that the solvent contact area of each DAI-target complex could be stabilized (Fig. 9B). Among them, the solvent contact area of the beta-sitosterol-PGR complex gradually decreased, indicating that the two were more tightly bound. The radius of rotation (Rg) analysis showed that the radius of rotation of these protein-small molecule complexes was stable, suggesting that the protein conformation was stable and unaffected by the drug's small molecules (Fig. 9C). The number and density of hydrogen bonds in the binding complexes reflect the binding strength (Fig. 9D). The density and number of hydrogen bonds of wogonin-AKT1 were higher than those of wogonin-PTGS1, beta-sitosterol-MAPK1 was higher than that of β-sitosterol-PGR, and americanin A-AKT1 was higher than that of americanin A-PRKACA. In summary, MDS further verified the good binding between these core DAIs and their targets.

Fig. 9.

Molecular dynamics simulation (MDS) of selected DAIs of ABR-MOR with core target protein. A) The root mean square deviation (RMSD) curves, B) solvent accessible surface area (SASA), C) radius of rotation (Rg), and D) the number and density of hydrogen bonds analysis of the binding of drug small molecules to target proteins.

4. Discussion

Despite an increase in the development of anti-osteoporosis medications, OP still poses significant challenges and burdens to countries worldwide [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. Scholars have recognized the great potential of TCM in treating OP [8,24,25]. However, the specific components and molecular mechanisms of various herbal medicines remain unclear. This study aimed to investigate the molecular mechanisms of DAIs, target genes, and potential signaling pathways of the main herbs ABR and MOR, which are paired in the TCM formula Ba Ji Tian Liquor for the treatment of OP for the first time. TCM emphasizes a combination of multiple herbs in herbal formulas for treating the disease. As recorded in the Dictionary of Traditional Chinese Medicine: “ABR has the functions of nourishing liver and kidney, and strengthening bones and muscles; it can be used for soreness of waist and knees, weakness of muscles and bones due to liver-yang”. “MOR has the effects of tonifying kidney-yang, and strengthening bones and muscles. It can be used for impotence and nocturnal emission, arthralgia due to rheumatism, and weakness of bones and muscles” [26]. Therefore, both ABR and MOR have the functions of tonifying kidney-yang and strengthening bones and muscles and can be combined to strengthen bones. According to the NPA results, 55.66 % of ABR-MOR targets overlap with OP targets, indicating a strong correlation between ABR-MOR and OP. In the “disease-drug-DAI-target” interaction network, the main DAIs identified in the treatment of OP by ABR-MOR were quercetin, kaempferol, wogonin, beta-sitosterol, baicalein, palmatine, berberine, stigmasterol, americanin A and Epiberberine. Among them, ABR-DAIs showed stronger associations with OP targets, suggesting a more critical therapeutic role. KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that ABR-MOR may regulate OP processes through various pathways, including the regulation of immune-inflammatory responses, cellular processes such as cell proliferation, senescence and apoptosis, the estrogen signaling pathway, and angiogenesis-related signaling pathway. Further analysis of the enrichment results identified 19 predicted targets that were enriched in the osteoclast differentiation signaling pathway. In addition, the predicted targets were found to be enriched in bone metabolism-related cell differentiation biological processes, such as osteoblasts, osteoclasts, chondrocytes, endothelial cells, macrophages, and stem cells. Therefore, it is suggested that the ABR-MOR may treat OP by regulating various pathways such as immune-inflammatory responses, cell biological processes, and bone metabolism-related cell differentiation.

After compiling traditional herbal formulas for the treatment of OP, it was found that ABR was the herb that appeared most frequently in these formulas [8]. Studies have shown that ABR or ABR extract can significantly improve the accumulation of bone mineral salts, the activity of ALP, and the mRNA expression level of osteogenesis-related genes (RUNX2, OP-1, BGLAP, and β-catenin) in OP animal models. This promotes bone formation and inhibits bone loss, demonstrating its satisfactory anti-OP ability [14,27,28]. A systematic review further confirmed that ABR is an effective herb for treating OP [29]. ABR contains several DAIs, including quercetin, kaempferol, wogonin, and beta-sitosterol. Some of them have been verified for their therapeutic effects on OP. ABR polysaccharide is a macromolecular carbohydrate derivative extracted from ABR, consisting of mannose, xylose, fructose, and glucuronic acid. It exhibits multiple pharmacological activities such as immunomodulatory, antitumor, antiaging, anticoagulant, and hypoglycemic. Oral supplementation of ABR polysaccharide for OP rats can promote the expression of osteogenesis-related genes RUNX2 and Osterix by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [30]. Additionally, it regulates osteoclast differentiation and reduces bone resorption by modulating the RANK/RANKL/OPG pathway [27]. Moreover, ABR steroids, including beta-ecdysterone, play a significant role in anti-OP therapy. It promotes the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of BMSCs and osteoblasts while reducing apoptosis and promoting bone accumulation. This is achieved through the regulation of various signaling pathways, such as the ERα-AMPK-Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K/AKT pathways [[31], [32], [33], [34]]. However, both ABR polysaccharides and ABR sterols are generalized nomenclatures that contain multiple components. The specific individual components responsible for their anti-OP therapeutic effects, as well as the optimal drug dosages, remain understudied. In this study, network pharmacological analysis revealed that quercetin and kaempferol are most closely linked to OP targets and may serve as the core pharmacological active ingredients for the treatment of OP. Fortunately, these two compounds have been proven to possess various biological characteristics, including antioxidative, antiaging, and antiapoptotic activities. They can play an anti-OP role through multiple mechanisms such as promoting osteoblast differentiation, inhibiting osteoclast formation, and resisting iron overload. Presently, they are being explored as monomers or in combination with other compounds for potential application in OP therapy [20,21,[35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]].

Wogonin, a flavonoid extracted from Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, has been found to possess antimicrobial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory activities. It is commonly used to treat of viral diseases [44,45], inflammatory diseases [46], diabetes [47], and cancer [[48], [49], [50]]. Previous studies have demonstrated that wogonin can reverse the upregulation of PDK1 and PDK4 in THP1 macrophages induced by lipopolysaccharide, resulting in the upregulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, promoting pyruvate metabolism, reducing lactic acid content, blocking IL-6/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways to regulate macrophage polarization, and thus playing an anti-inflammatory role [51]. However, an inflammatory microenvironment is a detrimental condition in the OP microenvironment. Therefore, wogonin may be a promising drug to treat OP based on its high anti-inflammatory effect. Additionally, studies have shown that wogonin supplementation in rats with osteoporotic fractures can promote fracture healing by activating the AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway [52]. Furthermore, wogonin inhibits osteoclast differentiation by inhibiting the translocation of NFATc1 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, leading to downregulation of the expression of osteoclast differentiation-related genes such as tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), calcitonin receptor, and osteoclast-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor (OSCAR) [53]. This finding is consistent with the present results that the potential target of ABR-MOR in the treatment of OP is enriched in the KEGG signaling pathway of osteoclast differentiation. Moreover, wogonin can be loaded onto titanium implants using layer-by-layer self-assembly technology and implanted into osteoporotic bone defects. The sustained release of wogonin effectively regulates the M1/M2 polarization ratio of macrophages, promotes the expression of the anti-inflammatory factors TGF-β 1 and Arg-1, and improves the local inflammatory microenvironment, thus effectively increasing bone accumulation around implants [54]. In this study, wogonin was the third major DAI in the drug-OP target network. Therefore, wogonin may play an important role in improving the inflammatory microenvironment, anti-oxidative stress, and inhibiting osteoclast differentiation, which could be the key mechanisms in the treatment of OP using ABR-MOR.

MOR belongs to the Rubiaceae Juss family, which is a classic herbal medicine widely used in orthopedics and traumatology, and has great application potential. Studies have shown that MOR contains iridoid components, polysaccharide components (MOP), and anthraquinone components. The iridoid components have been proven to significantly promote the proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of MC3T3-E1 cells. leading to an improvement in bone mineral content, bone mineral density, bone volume fraction, and bone microstructure in Monotropein-treated OVX rats [[55], [56], [57]]. On the other hand, supplementing MOP to OVX rats can alleviate the progression of OP by inhibiting the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α/peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ pathway, upregulating miR-21 and activating the PI3K/AKT pathway [58,59]. Researchers obtained MOP crude products from MOR by different extraction methods, which may affect the ability of BMSC-derived exosomes to induce osteoclast differentiation by upregulating miR-101-3p or inhibiting PTGS2 expression [12]. Furthermore, researchers have isolated and identified polysaccharide components MOW50-1, MOP70-1, MOP70-2, and MOW90-1 from MOP crude products. These components have been found to significantly promote the proliferation, differentiation, mineralization, and osteogenic differentiation-related genes (RUNX2, osterix, osteocalcin, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein, and osteoprotegerin) in MC3T3-E1 cells, thereby possessing the potential value of anti-OP [[60], [61], [62]]. As shown by the results of network pharmacology in this study, MOR contains a variety of anthraquinones, which may participate in the treatment of OP. Some anthraquinones, such as M13, rubiadin-1-methyl ether, 2-hydroxy-1-methoxy-anthraquinone, 1,2-dihydroxy-3-methylanthraquinone, and 1,3,8-trihydroxy-2-methoxy-anthraquinone, can promote osteogenic differentiation through Wnt/β-catenin, and most anthraquinones can inhibit TRAP activity and bone resorption of osteoclasts [11,63]. Therefore, MOR is believed to have great potential and broad application prospects in the treatment of OP. However, in contrast to previous studies, the present study results show that beta-sitosterol and Americana A are the DAIs with the closest relationship between MOR and OP targets.

Beta-sitosterol, a common phytosterol, is a common DAI of ABR and MOR. It has been found that β -sitosterol has no obvious toxicity in pharmacological screening, and its pharmacokinetic characteristics have also been widely studied [64]. It has anti-inflammatory, antioxidation, and immune regulation effects [65], and has been used to explore the treatment of various conditions, including cancer [66], prostatic hyperplasia [67], lung inflammation [68], and digestive system diseases [69]. Some studies have shown that it can significantly activate OPG expression while inhibiting RANKL expression. This indicates its ability to regulate the processes of osteogenic differentiation and osteoclast differentiation [70,71]. The MDT and MDS results of the present study showed that beta-sitosterol was able to form good binding with PGR and MAPK1, suggesting that beta-sitosterol may play a regulatory role through the estrogen signaling pathway and the MAPK signaling pathway. Its unique properties make it a potential core DAI for improving the unfavorable microenvironment of OP, such as immune inflammation and oxidative stress. However, there is limited research regarding the anti-OP effect of beta-sitosterol.

Americanin A is a bioactive dibenzyl butyrolactone lignan, that can be extracted from Morinda citrifolia (Noni), Centaurea americana, and MOR. It has tyrosinase inhibition and free radical scavenging activities and is an effective antioxidant [[72], [73], [74]]. In addition, Americanin A has been found to regulate the ATM/ATR signaling pathway and the Skp2-p27 axis to resist tumors [75]. In addition, Americanin A also exhibits effective antibacterial activity against S. haemolyticus 562B and S. epidermidis 1042 at a concentration of 100 μg/ml [76]. However, no studies have explored the possible application of americanin A in OP. The present NPA results suggest that americanin A may regulate OP through 11 targets, including ESR1, PTGS2, and PRKACA. Oxidative stress is an important component of the unfavorable microenvironment of osteoporosis, and there are a large number of studies using the anti-oxidative stress capacity of herbal ingredients for the treatment of OP [38,43,71]. Therefore, an appropriate dose of americanin A may be able to exert a therapeutic effect on OP through anti-oxidative stress.

Based on the NPA methodology, the present study comprehensively analyzed and concluded that PTGS2, PTGS1, PRKACA, PGR, MAPK1, AKT1, and RELA may be the core targets of ABR-MOR for the treatment of OP. PTGS is a prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase, also known as cyclooxygenase (COX), a key rate-limiting enzyme in prostaglandin biosynthesis. It has two isoforms, constitutive PTGS1 (COX-1) and inducible PTGS2 (COX-2), which are involved in the modulation of inflammatory responses and vascular reactivity [77]. Prostaglandins (such as PGE2 and PGI2) play a vital role in bone physiology and bone loss. The regulation of prostaglandin expression and release by COX can affect bone calcium and bone metabolism [78,79]. PRKACA is a catalytic subunit encoding protein kinase A (PKA), and the PKA-cAMP axis is an important signaling pathway for regulating cell processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation and adjusting osteoblast/osteoclast differentiation [80,81]. Furthermore, the disorder of the estrogen-related signaling pathway is an important cause of postmenopausal osteoporosis. PGR is a member of the steroid receptor superfamily and is involved in estrogen pathway signal transduction. Therefore, PGR may participate in the mechanism of ABR-MOR for OP through the estrogen signaling pathway. RELA is a gene encoding the NF-κB subunit p65. The heterodimer RELA/NF-κB1 (p65/p50) complex is the most commonly expressed form of NF-κB. The NF-κB, PI3K/AKT, and MAPK signaling pathways are closely related to cell processes such as cell proliferation, aging, apoptosis, and differentiation and participate in regulating the adverse microenvironments in OP, such as oxidative stress and inflammation [[82], [83], [84]]. The present KEGG pathway enrichment results showed that ABR-MOR can regulate the OP process through the PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and NF-κB signaling pathways. Therefore, the seven targets are most likely to be the core regulatory targets of ABR-MOR in the treatment of OP.

To further verify the accuracy of the NPA results, we docked wogonin, beta-sitosterol, and Americanin A with core targets such as PTGS2, PTGS1, PRKACA, PGR, MAPK1, AKT1, and RELA. The results showed that the three DAIs demonstrated good binding ability to the core targets. Additionally, beta-sitosterol formed at least 2 hydrogen bonds with MAPK and PGR; americanin A and wogonin formed at least 2 hydrogen bonds with MAPK1, AKT1, RELA, PTGS2, PTGS1 and PRKACA, which ruled out the possibility of false positives. Moreover, the MDS outcomes further validated the MDT results. These outcomes provide theoretical evidence for the use of wogonin, beta-sitosterol, and americanin A or even formulas with ABR and MOR as the main herbs for the treatment of OP.

5. Limitations

In this study, we conducted extensive work using NTA, MDT, and MDS to analyze and provide a scientific theoretical basis for the combined application of ABR and MOR in the treatment of OP. However, there are still some limitations in this study. First, the database of herbs is mixed. In this study, only TCMSP, the most commonly used database, was selected to obtain DAIs and targets of ABR-MOR. This study may suffer from a lack of updated information on DAIs and their targets due to the constant updating of research. Second, the MDT and MDS analyses only focused on wogonin, beta-sitosterol, and americanin A. However, there are still numerous DAIs and targets associated with ABR-MOR that warrant further exploration. Third, the results of the enrichment analysis in this study suggest that ABR-MOR may exert its therapeutic effects through multiple signaling pathways and biological processes. It is important to note that the core targets predicted in this study do not represent the entirety of its mechanisms of action. Fourth, this study predicted the potential molecular mechanism of the combination of ABR and MOR in treating OP, but it is crucial to conduct further experimental studies to validate these results.

6. Conclusion

This preliminary study found that the main herbs, MOR and ABR, of the Chinese herbal formula Ba Ji Tian Liquor may exert therapeutic effects on OP through various DAIs, targets, and signaling pathways. ABR-MOR primarily exerts anti-OP effects by modulating signaling pathways related to immune-inflammatory responses, cellular biological processes, and osteoclast differentiation. ABR-MOR also could regulates the biological processes of differentiation of bone metabolism-related cells. The potential anti-osteoporosis DAIs of ABR-MOR include wogonin, beta-sitosterol, and americanin A, and the potential core regulatory targets are PTGS2, PTGS1, PRKACA, PGR, MAPK1, AKT1, and RELA. These findings provide a scientific basis for using the Chinese herbal formulas with ABR-MOR as the core herb for OP therapy, as well as new research prospects for anti-OP drug therapy.

Declaration of competing interest

This manuscript is approved by all authors for publication, and no conflict of interest exists. This work described is original research that has not been published previously and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part.

Acknowledgment

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 82372405) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No: 2042023kf0199).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101586.

Contributor Information

Jingfeng Li, Email: jingfengli@whu.edu.cn.

Shifeng Zhou, Email: 17312506968@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Beijing:People's Medical Publishing House . 1963. Huang Di Nei Jing • Su Wen. [Google Scholar]

- 2.C. S. o. O. a. B. M. Research Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary osteoporosis. Chinese J. Osteoporosis Bone Mineral Res. 2022;15(2022):573–611. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beijing:People's Medical Publishing House . 2018. The Epidemiological Investigation Report of Osteoporosis in China. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L., Yu W., Yin X., Cui L., Tang S., Jiang N., Cui L., Zhao N., Lin Q., Chen L., Lin H., Jin X., Dong Z., Ren Z., Hou Z., Zhang Y., Zhong J., Cai S., Liu Y., Meng R., Deng Y., Ding X., Ma J., Xie Z., Shen L., Wu W., Zhang M., Ying Q., Zeng Y., Dong J., Cummings S.R., Li Z., Xia W. Prevalence of osteoporosis and fracture in China: the China osteoporosis prevalence study. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foessl I., Dimai H.P., Obermayer-Pietsch B. Long-term and sequential treatment for osteoporosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023;19:520–533. doi: 10.1038/s41574-023-00866-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid I.R., Billington E.O. Drug therapy for osteoporosis in older adults. Lancet (London, England) 2022;399:1080–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilaca T., Eastell R., Schini M. Osteoporosis in men, the lancet. Diabetes & endocrinol. 2022;10:273–283. doi: 10.1016/s2213-8587(22)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Z., Lu Y., Halmurat U., Jing J., Xu D. Study of osteoporosis treatment principles used historically by ancient physicians in Chinese Medicine. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2013;19:862–868. doi: 10.1007/s11655-013-1328-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hefei:Anhui Science and Technology Publishing House, Compilation of Sheng Ji Zong Lu, 1992.

- 10.Shenyang: Liaoning Science and Technology Publishing House, Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang, 1997.

- 11.Li C., Tian L., Wang Y., Luo H., Zeng J., Su P., Chen S., Liao Z., Guo W., He X., Chen S., Xu C. M13, an anthraquinone compound isolated from Morinda officinalis promotes the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs by targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Phytomedicine : Int. J. Phytotherapy Phytopharmacol. 2023;108 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu P., Jiao F., Huang H., Liu D., Tang W., Liang J., Chen W. Morinda officinalis polysaccharide enable suppression of osteoclastic differentiation by exosomes derived from rat mesenchymal stem cells. Pharmaceut. Biol. 2022;60:1303–1316. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2022.2093385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia T., Dong X., Lin L., Jiang Y., Ma X., Xin H., Zhang Q., Qin L. Metabolomics profiling provides valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of Morinda officinalis on protecting glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. Anal. 2019;166:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang L., Hou A., Zhang X., Zhang J., Wang S., Dong J., Zhang S., Jiang H., Kuang H. TMT-based proteomics analysis to screen potential biomarkers of Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix for osteoporosis in rats. Biomed. Chromatogr. : BMC. 2022;36:e5339. doi: 10.1002/bmc.5339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ru J., Li P., Wang J., Zhou W., Li B., Huang C., Li P., Guo Z., Tao W., Yang Y., Xu X., Li Y., Wang Y., Yang L. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminf. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Doncheva N.T., Morris J.H., Bork P., Jensen L.J., Mering C.V. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–d613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C., Chanda S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laskowski R.A., Swindells M.B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vella D., Marini S., Vitali F., Di Silvestre D., Mauri G., Bellazzi R. MTGO: PPI network analysis via topological and functional module identification. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5499. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23672-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M., Li M., Wei Y., Xue C., Chen M., Fei Y., Tan L., Luo Z., Cai K., Hu Y. ROS-activatable biomimetic interface mediates in-situ bioenergetic remodeling of osteogenic cells for osteoporotic bone repair. Biomaterials. 2022;291 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gan L., Leng Y., Min J., Luo X.M., Wang F., Zhao J. Kaempferol promotes the osteogenesis in rBMSCs via mediation of SOX2/miR-124-3p/PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022;927 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.174954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang A.Y., Xiong Z., Liu K., Chang Y., Shu L., Gao G., Zhang C. Identification of kaempferol as an OSX upregulator by network pharmacology-based analysis of qianggu Capsule for osteoporosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1011561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah M.A., Faheem H.I., Hamid A., Yousaf R., Haris M., Saleem U., Shah G.M., Alhasani R.H., Althobaiti N.A., Alsharif I., Silva A.S. The entrancing role of dietary polyphenols against the most frequent aging-associated diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2023 doi: 10.1002/med.21985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao da C., Xiao P.G. Network pharmacology: a Rosetta Stone for traditional Chinese medicine. Drug Dev. Res. 2014;75:299–312. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Kai S.M., Liu Tao, Wen Haonan, Gong Yanlong, Zhang Yabin. Progress of the application of network pharmacology on the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in the Traditional Chinese Medicine. Chin. J. Osteoporos. 2020;26:1222–1225. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-7108.2020.08.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House . 2014. Dictionary of Traditional Chinese Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiaoqin Lang Y.G., Zhou Ye, Chen Meihong, Xu Chuxyun. Influence of achyranthan on bone metabolism and biomechanical characteristics of elderly rats model of osteoporosis. Chin. J. General Pract. 2019;17:547–550+589. doi: 10.16766/j.cnki.issn.1674-4152.000730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J.H., Wei Y.J., Zhou Z.Y., Hou Y.M., Wang C.L., Wang L.B., Wu H.J., Zhang Y., Dai W.W. Efficacy of the herbal pair, Radix Achyranthis Bidentatae and Eucommiae Cortex, in preventing glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in the zebrafish model. J. Integr. Med. 2022;20:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lian Y., Zhu H., Guo X., Fan Y., Xie Z., Xu J., Shao M. Antiosteoporosis effect and possible mechanisms of the ingredients of Radix Achyranthis Bidentatae in animal models of osteoporosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of in vivo studies. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023;18:531. doi: 10.1186/s13018-023-04031-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fanhui Y.H.Z. Study on Achyranthes bidentata polysaccharides improving bone metabolism in osteoporotic fracture rats by regulating wnt/Β-catenin pathway. Acta. Chin. Med. 2021;36:2188–2194. doi: 10.16368/j.issn.1674-8999.2021.10.457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.W. Y. L. J. W. L. W. C. D. Weiwei β-Ecdysone protects osteocytes from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis via Akt signal pathway in vitro. Chin. J. Osteoporos. 2019;25:375–379. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-7108.2019.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shang Lanqing L.Y., Zhou Guangzhi, Tai Dongxu, Kang Siwen. 2023. Research Progress of β-ecdysterone in the Treatment of Osteoporosis in View of the “Gu Rou Bu Xiang Qin” Theory, Chinese Archives of Traditional Chinese Medicine; pp. 1–8. 21.1546.R.20230815.1855.008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang Tao S.M., Chen Qingzhen, Ling Cuimin, Shen Zhen, Wang Gang, Huo Shaochuan, Lin Yanping, Liu Haiquan, Wang Qinsheng, Zeng Zhenming. Inokosterone effects on proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts from neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats. Chinese J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2020;24:3636–3642. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.2645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai W.W., Wang L.B., Jin G.Q., Wu H.J., Zhang J., Wang C.L., Wei Y.J., Lee J.H., Lay Y.E., Yao W. Beta-ecdysone protects mouse osteoblasts from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in vitro. Planta Med. 2017;83:888–894. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-107808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing X., Tang Q., Zou J., Huang H., Yang J., Gao X., Xu X., Ma S., Li M., Liang C., Tan L., Liao L., Tian W. Bone-targeted delivery of senolytics to eliminate senescent cells increases bone formation in senile osteoporosis. Acta Biomater. 2023;157:352–366. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao J., Zhang G., Chen B., He Q., Mai J., Chen W., Pan Z., Yang J., Li J., Ma Y., Wang T., Wang H. Quercetin protects against iron overload-induced osteoporosis through activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Life Sci. 2023;322 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.121326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y., Che L., Chen X., He Z., Song D., Yuan Y., Liu C. Repurpose dasatinib and quercetin: targeting senescent cells ameliorates postmenopausal osteoporosis and rejuvenates bone regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2023;25:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang N., Wang L., Yang J., Wang Z., Cheng L. Quercetin promotes osteogenic differentiation and antioxidant responses of mouse bone mesenchymal stem cells through activation of the AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway, Phytother Res. : PTR. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ptr.7010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui Z., Zhao X., Amevor F.K., Du X., Wang Y., Li D., Shu G., Tian Y., Zhao X. Therapeutic application of quercetin in aging-related diseases: SIRT1 as a potential mechanism. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.943321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie B., Zeng Z., Liao S., Zhou C., Wu L., Xu D. Kaempferol ameliorates the inhibitory activity of dexamethasone in the osteogenesis of mc3t3-E1 cells by JNK and p38-MAPK pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.739326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang A., Yuan W., Song Y., Zang Y., Yu Y. Osseointegration effect of micro-nano implants loaded with kaempferol in osteoporotic rats. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.842014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma A.R., Nam J.S. Kaempferol stimulates WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway to induce differentiation of osteoblasts. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2019;74 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.108228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi E.M. Kaempferol protects MC3T3-E1 cells through antioxidant effect and regulation of mitochondrial function. Food Chem. Toxicol. : Int. J. Pub. British Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2011;49:1800–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H., Cai J., Li C., Deng L., Zhu H., Huang T., Zhao J., Zhou J., Deng K., Hong Z., Xia J. Wogonin inhibits latent HIV-1 reactivation by downregulating histone crotonylation. Phytomedicine : Int. J. Phytotherapy Phytopharmacol. 2023;116 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2023.154855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lucas C.D., Dorward D.A., Sharma S., Rennie J., Felton J.M., Alessandri A.L., Duffin R., Schwarze J., Haslett C., Rossi A.G. Wogonin induces eosinophil apoptosis and attenuates allergic airway inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015;191:626–636. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1565OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J., Tian X., Liu J., Mo Y., Guo X., Qiu Y., Liu Y., Ma X., Wang Y., Xiong Y. Therapeutic material basis and underling mechanisms of Shaoyao Decoction-exerted alleviation effects of colitis based on GPX4-regulated ferroptosis in epithelial cells. Chin. Med. 2022;17:96. doi: 10.1186/s13020-022-00652-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bak E.J., Kim J., Choi Y.H., Kim J.H., Lee D.E., Woo G.H., Cha J.H., Yoo Y.J. Wogonin ameliorates hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia via PPARα activation in db/db mice. Clin. Nutr. 2014;33:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuli H.S., Rath P., Chauhan A., Parashar G., Parashar N.C., Joshi H., Rani I., Ramniwas S., Aggarwal D., Kumar M., Rana R. Wogonin, as a potent anticancer compound: from chemistry to cellular interactions, Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood. N.J.). 2023;248:820–828. doi: 10.1177/15353702231179961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baumann S., Fas S.C., Giaisi M., Müller W.W., Merling A., Gülow K., Edler L., Krammer P.H., Li-Weber M. Wogonin preferentially kills malignant lymphocytes and suppresses T-cell tumor growth by inducing PLCgamma1- and Ca2+-dependent apoptosis. Blood. 2008;111:2354–2363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Banik K., Khatoon E., Harsha C., Rana V., Parama D., Thakur K.K., Bishayee A., Kunnumakkara A.B. Wogonin and its analogs for the prevention and treatment of cancer: a systematic review. Phytother Res. : PTR. 2022;36:1854–1883. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Yuwen L.S., Hang Xiaopeng, Zeng Xing, Zhang Xian. Effects of wogonin on LPS-induced THP1 macrophage inflammation model based on IL-6/STAT3 and PI3K/Akt pathway. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2022;45:1721–1725. doi: 10.13863/j.issn1001-4454.2022.07.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.L. Q. C. K. G. Z. Q. Ligang Effect of wogonin on bone fracture healing in rats with osteoporosis by regulating AMPK/SIRT1 signaling pathway. The Journal of Practical Medicine. 2023;39:410–416. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006⁃5725.2023.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geng X., Yang L., Zhang C., Qin H., Liang Q. Wogonin inhibits osteoclast differentiation by inhibiting NFATc1 translocation into the nucleus. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015;10:1066–1070. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang D., Chen M.W., Wei Y.J., Geng W.B., Hu Y., Luo Z., Cai K.Y. Construction of wogonin nanoparticle-containing strontium-doped nanoporous structure on titanium surface to promote osteoporosis fracture repair. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2022;11 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202201405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai M., Liu M., Chen P., Liu H., Wang Y., Yang D., Zhao Z., Ding P. Iridoids with anti-inflammatory effect from the aerial parts of Morinda officinalis How. Fitoterapia. 2021;153 doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2021.104991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu M., Lai H., Peng W., Zhou X., Zhu L., Tu H., Yuan K., Yang Z. Monotropein: a comprehensive review of biosynthesis, physicochemical properties, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1109940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Z., Zhang Q., Yang H., Liu W., Zhang N., Qin L., Xin H. Monotropein isolated from the roots of Morinda officinalis increases osteoblastic bone formation and prevents bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Fitoterapia. 2016;110:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rong K., Chen P., Lang Y., Zhang Y., Wang Z., Wen F., Lu L. Morinda officinalis polysaccharide attenuates osteoporosis in rats underwent bilateral ovariectomy by suppressing the PGC-1α/PPARγ pathway. J. Orthop. Surg. 2022;30 doi: 10.1177/10225536221130824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu P.Y., Chen W., Huang H., Tang W., Liang J. Morinda officinalis polysaccharide regulates rat bone mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic-adipogenic differentiation in osteoporosis by upregulating miR-21 and activating the PI3K/AKT pathway. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2022;38:675–685. doi: 10.1002/kjm2.12544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang K., Huang D., Zhang D., Wang X., Cao H., Zhang Q., Yan C. Investigation of inulins from the roots of Morinda officinalis for potential therapeutic application as anti-osteoporosis agent. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;120:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan C., Huang D., Shen X., Qin N., Jiang K., Zhang D., Zhang Q. Identification and characterization of a polysaccharide from the roots of Morinda officinalis, as an inducer of bone formation by up-regulation of target gene expression. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;133:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang D., Zhang S., Jiang K., Li T., Yan C. Bioassay-guided isolation and evaluation of anti-osteoporotic polysaccharides from Morinda officinalis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020;261 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y.B., Zheng C.J., Qin L.P., Sun L.N., Han T., Jiao L., Zhang Q.Y., Wu J.Z. Antiosteoporotic activity of anthraquinones from Morinda officinalis on osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Molecules. 2009;14:573–583. doi: 10.3390/molecules14010573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khan Z., Nath N., Rauf A., Emran T.B., Mitra S., Islam F., Chandran D., Barua J., Khandaker M.U., Idris A.M., Wilairatana P., Thiruvengadam M. Multifunctional roles and pharmacological potential of β-sitosterol: emerging evidence toward clinical applications. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022;365 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao P.C., Lai M.H., Hsu K.P., Kuo Y.H., Chen J., Tsai M.C., Li C.X., Yin X.J., Jeyashoke N., Chao L.K. Identification of β-sitosterol as in vitro anti-inflammatory constituent in moringa oleifera. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:10748–10759. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang H., Wang Z., Zhang Z., Liu J., Hong L. Advances in Nutrition. 2023. β-Sitosterol as a promising anticancer agent for chemoprevention and chemotherapy: mechanisms of action and future prospects. Bethesda, Md. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berges R.R., Windeler J., Trampisch H.J., Senge T. Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of beta-sitosterol in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Beta-sitosterol Study Group. Lancet (London, England) 1995;345:1529–1532. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou B.X., Li J., Liang X.L., Pan X.P., Hao Y.B., Xie P.F., Jiang H.M., Yang Z.F., Zhong N.S. β-sitosterol ameliorates influenza A virus-induced proinflammatory response and acute lung injury in mice by disrupting the cross-talk between RIG-I and IFN/STAT signaling. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020;41:1178–1196. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng S., Dai Z., Liu A.B., Huang J., Narsipur N., Guo G., Kong B., Reuhl K., Lu W., Luo Z., Yang C.S. Intake of stigmasterol and β-sitosterol alters lipid metabolism and alleviates NAFLD in mice fed a high-fat western-style diet, Biochimica et biophysica acta. Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2018;1863:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruangsuriya J., Charumanee S., Jiranusornkul S., Sirisa-Ard P., Sirithunyalug B., Sirithunyalug J., Pattananandecha T., Saenjum C. Depletion of β-sitosterol and enrichment of quercetin and rutin in Cissus quadrangularis Linn fraction enhanced osteogenic but reduced osteoclastogenic marker expression. Bmc Complement. Med. Therapies. 2020;20:105. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-02892-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang T., Li S., Yi C., Wang X., Han X. Protective role of β-sitosterol in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in rats via the RANKL/OPG pathway. Alternative Ther. Health Med. 2022;28:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Su B.N., Pawlus A.D., Jung H.A., Keller W.J., McLaughlin J.L., Kinghorn A.D. Chemical constituents of the fruits of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) and their antioxidant activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:592–595. doi: 10.1021/np0495985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shoeb M., MacManus S.M., Kumarasamy Y., Jaspars M., Nahar L., Thoo-Lin P.K., Nazemiyeh H., Sarker S.D. Americanin, a bioactive dibenzylbutyrolactone lignan, from the seeds of Centaurea americana. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2370–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Masuda M., Murata K., Fukuhama A., Naruto S., Fujita T., Uwaya A., Isami F., Matsuda H. Inhibitory effects of constituents of Morinda citrifolia seeds on elastase and tyrosinase. J. Nat. Med. 2009;63:267–273. doi: 10.1007/s11418-009-0328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jung C., Hong J.Y., Bae S.Y., Kang S.S., Park H.J., Lee S.K. Antitumor activity of americanin A isolated from the seeds of phytolacca americana by regulating the ATM/ATR signaling pathway and the skp2-p27 Axis in human colon cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2015;78:2983–2993. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De La Cruz-Sánchez N.G., Gómez-Rivera A., Alvarez-Fitz P., Ventura-Zapata E., Pérez-García M.D., Avilés-Flores M., Gutiérrez-Román A.S., González-Cortazar M. Antibacterial activity of Morinda citrifolia Linneo seeds against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus spp. Microb. Pathog. 2019;128:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levin G., Duffin K.L., Obukowicz M.G., Hummert S.L., Fujiwara H., Needleman P., Raz A. Differential metabolism of dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid and arachidonic acid by cyclo-oxygenase-1 and cyclo-oxygenase-2: implications for cellular synthesis of prostaglandin E1 and prostaglandin E2. Biochem. J. 2002;365:489–496. doi: 10.1042/bj20011798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Myers L.K., Bhattacharya S.D., Herring P.A., Xing Z., Goorha S., Smith R.A., Bhattacharya S.K., Carbone L., Faccio R., Kang A.H., Ballou L.R. The isozyme-specific effects of cyclooxygenase-deficiency on bone in mice. Bone. 2006;39:1048–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krieger N.S., Frick K.K., LaPlante Strutz K., Michalenka A., Bushinsky D.A. Regulation of COX-2 mediates acid-induced bone calcium efflux in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Res. : Offic. J. American Soc. Bone Mineral Res. 2007;22:907–917. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Le Stunff C., Tilotta F., Sadoine J., Le Denmat D., Briet C., Motte E., Clauser E., Bougnères P., Chaussain C., Silve C. Knock-in of the recurrent R368X mutation of PRKAR1A that represses cAMP-dependent protein kinase A activation: a model of type 1 acrodysostosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. : Offic. J. American Soc. Bone Mineral Res. 2017;32:333–346. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rendina-Ruedy E., Rosen C.J. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) regulation of metabolic homeostasis: an old dog teaches us new tricks. Mol. Metabol. 2022;60 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xie X., Hu L., Mi B., Panayi A.C., Xue H., Hu Y., Liu G., Chen L., Yan C., Zha K., Lin Z., Zhou W., Gao F., Liu G. SHIP1 activator AQX-1125 regulates osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis through PI3K/akt and NF-κb signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.826023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ye C., Zhang W., Hang K., Chen M., Hou W., Chen J., Chen X., Chen E., Tang L., Lu J., Ding Q., Jiang G., Hong B., He R. Extracellular IL-37 promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:753. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1904-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arnst J., Jing Z., Cohen C., Ha S.W., Viggeswarapu M., Beck G.R., Jr. Bioactive silica nanoparticles target autophagy, NF-κB, and MAPK pathways to inhibit osteoclastogenesis. Biomaterials. 2023;301 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.