A stressful situation

“Your patient had a severe adverse reaction to the medication you prescribed.”

Receiving this information, you as the patient's physician are flooded with negative thoughts and feelings and a desire to escape. Through selection, training, and reinforcement, you have been conditioned to think, “I must be thoroughly competent,” “I cannot make mistakes,” and “I need to be totally responsible and in control.”1

This stress-producing belief system can be identified, challenged, and modified to increase well-being without sacrificing integrity and work quality. I describe some cognitive-behavioral techniques that can help physicians break this cycle of negative thinking.

Negative interpretation

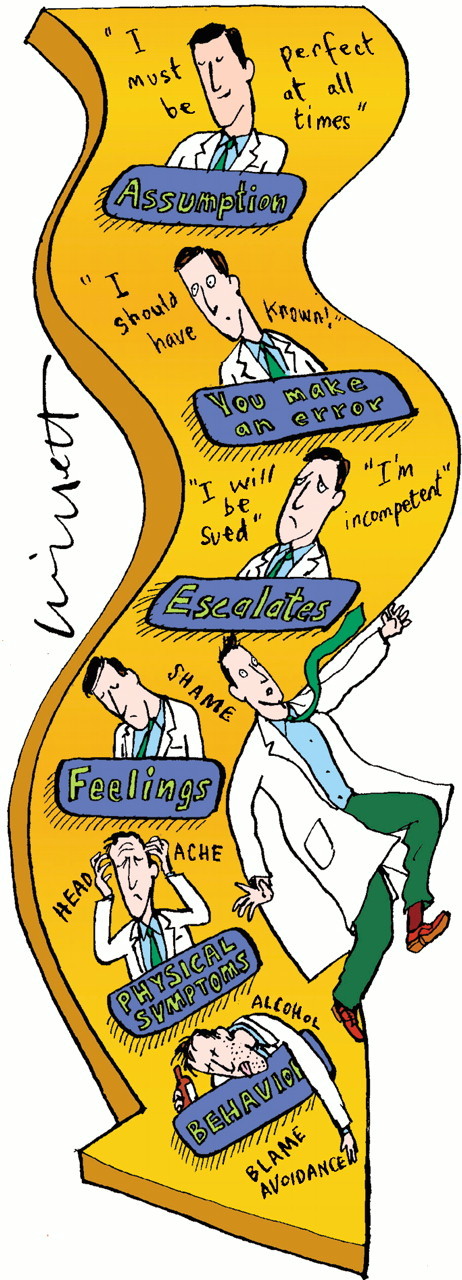

Figure 1 shows a physician's initial negative interpretation of the clinical situation in the opening line. Components of this reaction include thoughts and images, feelings, physical symptoms, and behavior. All of these components are interactive and affect each other. Whereas the thoughts and images are specific to the current situation, they can also derive from previous underlying assumptions. Negative thoughts can escalate, affecting a person's mental and physical health and cumulatively damaging professional and personal relationships, decisions, and behavior.

Figure 1.

Negative thoughts can escalate (drawing by Malcolm Willett)

Thought distortions

When a person encounters a difficult situation, it is common for the initial reaction to then continue to spiral downward. This negative feedback loop is triggered partly by common thought distortions (table).2,3 Recognizing and questioning these immediately is crucial in interrupting the negative downward interaction with the other components.

Challenging those negative thoughts

Several steps can be taken to manage a stressful situation in an effective and healthy way.

Describe the difficult situation to yourself and identify and separate your thoughts, images, feelings, physical reactions, and behavior before you have a chance to let it spiral out of control. Separating out these different components shows how they build on each other and how to intervene quickly.

Note that our thoughts and images about ourselves and others—not the specific situation itself (in this case, an adverse reaction to a drug you prescribed)—determine feelings, physical symptoms, and behavior. Both immediate situation-specific thoughts and underlying assumptions are conditioned by past experiences and shaped by future expectations. Become alert to underlying faulty belief systems or assumptions that cause distress after observing automatic thoughts in several difficult situations. These underlying assumptions often remain unrecognized.

Identify common thought distortions and use the questions to evaluate them.

Note that identifying stress-producing thoughts and changing your thinking is not just a form of “positive thinking.” It involves realistically looking at all aspects of a problem—positive, negative, and neutral—and developing a more balanced approach.4 After a stressful situation, it is helpful to put this process in writing.

Same situation, different outcome

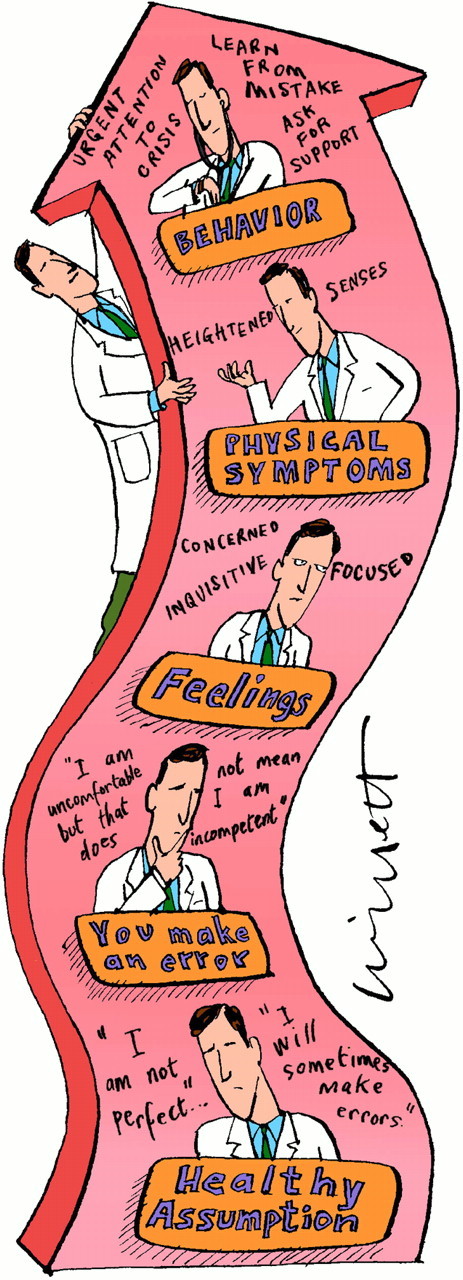

Figure 2 shows that the downward spiral can be interrupted by this process of realistically evaluating your thoughts.

Figure 2.

A realistic and healthy evaluation (drawing by Malcolm Willett)

Conclusions

In any difficult situation, identify your negative thoughts and the resulting effect they have on feelings, physical symptoms, and behavior. Relabel crises or challenges as opportunities for growth and sharing, and relabel vulnerable feelings as energizing resources to explore rather than deny. Look for thought distortions, dispute them, reframe them, and come up with alternative, balanced thinking. Remember that healthy self-respect and attention to one's needs are not selfishness.5 To cool yourself down when you're in a “hot” (ie, stressful) situation, remember “ICE”: Identify thoughts, Classify common thinking errors, and Explain realistically.

Table 1.

Common thought distortions and how to challenge them

| Distortion | Challenge |

|---|---|

| Magnification or minimization | Overemphasizing or underemphasizing one aspect of the situation: “I didn't check out with the patient if he understood the reason for the medication”; overlooking other factors that may be important |

| Polarization | Using black and white thinking: “My colleagues are going to think I am incompetent”; are there shades of gray? |

| Personalization | Taking the situation personally and ignoring the total picture: “It's my fault”; what would I say to a colleague in the same position? |

| Stress-producing language | Using words such as should, have to, must, need rather than would like, want: “I should never make a mistake” |

| Pessimistic thinking | Thinking of the situation as permanent, pervasive, and personal: “I'm never going to have the respect of my colleagues” or “I'm not suited to this profession”; rather than temporary, specific, and related to factors beside myself3 |

| Catastrophizing | Is this unfortunate incident a catastrophe: “I'm going to be sued”; if the bad outcome happened, what would/would not be the consequences, and could I handle them? |

Competing interests: None declared

Author: Felice Miller is a consulting psychologist and a member of the clinical faculty at University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Quill T, Williamson P. Healthy approaches to physician stress. Arch Intern Med 1990;150: 1857-1861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabbard G. Role of compulsiveness in the normal physician. JAMA 1985;254: 2926-2929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seligman M. Learned Optimism. New York City: Alfred Knopf; 1991.

- 4.Greenberger D, Padesky C. Mind Over Mood. New York City: Guilford Press; 1995.

- 5.Orman M. Physician's stress: is it inevitable? Mo Med 1989;86: 21-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]